Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 33

March 31, 2017

Justice and mercy

Over the last couple of weeks I have been struck by some significant differences between Orthodox and Western theology.

I don’t want to go off into an Orthodox triumphalist rant (though having said that, I probably will), but I think it is worth examining these differences, first, to see if they are merely semantic, or are something more. Secondly, to see if they tell us different things about ourselves and the world we live in.

What sparked it off was something Thorsten Marbach said at TGIF this morning.

He was speaking about justice, and said that at a conference on justice he had attended recently someone had said that as Christians we knew all about mercy, and needed to advance to justice.

That struck me, from a theological point of view, as a rather spectacular putting of the cart before the horse.

We surely need to advance from justice to mercy. To put it the other way round seems (to me) like saying that we need to advance from gospel to law.

I didn’t have much quibble about the particulars of what Thorsten was saying, and reporting what other people had said, about justice. It was the generalisation that seemed to have got it backwards.

An example that occurred to me was a recent political one, of the German attitude to Greek debt.

When the Nazis plundered the countries they occupied in the Second World War, there was a need for restitution, and the debt was calculated, But the Greeks forgave the debt in the interests of building a more peaceful Europe. Mercy trumped justice. Now, however, the German government is unwilling to forgive Greek debt, and demands justice — mercy be damned. Jesus told a parable about that (Matt 18:21-34). And in response to that, the Greek government is now moving back (or is it forward?) from mercy to justice.

[image error]

The Ladder of Divine Ascent of St John Climacus

Earlier in the week, because last Sunday was the fourth Sunday in Lent on which Orthodox Christians commemorate St John of the Ladder, I posted a copy of the ikon of the ladder on Facebook. The comments of some Western Christians were illuminating, in the sense that they illuminate some of the differences in outlook, though some responded with mirth, and others saw it as fear-inspiring.

St John Climacus uses the metaphor of Jacob’s ladder to show spiritual growth in the acquisition of Christian virtues, and four weeks into Lent is a good time to take stock of how we have grown or failed to grow.

An anthropologist, of all people, summed this up succinctly when he wrote:

The Orthodox moral world emerges as an arena in which good struggles against evil, the kingdom of heaven against the kingdom of earth. In life, humans are enjoined to embrace Christ, who assists their attainment of Christian virtues: modesty, humility, patience and love. At the same time, lack of discernment and incontinence impede the realization of these virtues and thereby conduce to sin; sin in turn places one closer to the Devil… Since the resurrection of Christ the results of this struggle have not been in doubt. So long as people affirm their faith in Christ, especially at moments of demonic assault, there is no need to fear the influence of the Devil. He exists only as an oxymoron, a powerless force.[1]

The angels aid people in attaining the virtues, and the demons seek to hinder them, St John’s book was written for monks in a neighbouring monastery, so all the humans shown in the illustration are monks, though it can be applied, mutatis mutandis, to any Christian.

One of the responses to this was “What an interesting image! It would be enough to terrify many“. and another “I often think of the picture that shows folk in he’ll shouting out to those saying ‘ why didn’t you tell me’. Sad that do many get saved through fear…”

I wonder if people would respond in the same way to C.S. Lewis’s book The Screwtape Letters, which seeks to do much the same thing for 20th century suburban Englishmen as St John Climacus was doing for 7th-century desert-dwelling monks. Is the difference simply a cultural gap, signifying a different time, place and environment, or does it indicate a theological difference as well?

Each step of the the ladder signifies a particular virtue to be acquired, or passion (vice) to be avoided. At the bottom is obedience, and at the top is love (not justice).

At TGIF Thorsten also showed a progression — Creation –> Fall –> Resurrection –> Restoration

We live in a fallen and broken world, and in that broken world, justice is one of the defences established by God to stop it becoming more broken. One of the major causes of the brokenness of the world is human unlovingness. It is human hatred and violence that make the world the mess it is today. Law cannot make people love each other. It cannot make people good. But law can limit the evil effects of our lack of love. Law cannot stop me hating my neighbour, but it can say that if I hit my neighbour over the head with a hammer, I’ll be locked up in jail. Justice is not love. The best one can say is that it is congealed love.

On the Sunday of St John of the Ladder, when I preached I tried to contextualise the message for a South African township, in much the same way, perhaps, as C.S. Lewis tried to do for English suburbs. So I said that many Christians say “I am blessed”. Those are the ones at the bottom of the ladder, but they have a long way to go. Those at the top do not say anything, but they are a blessing to others. They do not say of themselves “I am a blessing to others” — if they did, they would be dangling below the ladder, the demons having pulled them off. But it will be others who say of them that they are a blessing to others.

Justice is akin to righteousness (and they same Hebrew word is sometimes used for both in the Old Testament). And the problem with righteousness is that it so often leads to self-righteousness. I have met some crusaders for justice who would gladly give their bodies to be burned for the cause, but as St Paul says, “And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing” (I Cor 13:3).

The third thing that happened to me recently that made me think about this was a discussion on the Orthodox Peace Fellowship mailing list on the relation between justice and mercy.

It was sparked off by a news report that the designer of the AK-47 assault rifle had expressed remorse shortly before his death, and had the deaths of thousands on his conscience — those who had been killed by the weapon he designed. There was also a report that a church spokesman had sought to console him by saying that it wasn’t so bad, because the weapon had been used to protect the motherland from assault and that was a saving grace. In response to this, someone said,

Self defense is the most excusable of human weaknesses. Sometimes it is a sin deserving of the greatest mercy, for fear-driven will to survive is perhaps too powerful an instinct to resist. So we justify horrible things in the name of defense.

But surely defense can never be a “saving grace.” Especially when institutionalized and made a servant of the State’s own merciless self-interest.

My response to this was:

One of the problems with Western theology is that it tends to be legalistic — perhaps this is related to Latin being the language of law. Hence the emphasis on “justification”. There are the debates about justification by faith, about the “just” war, and “justifiable” homicide.

As I understand it the Orthodox position is that there is no such thing as “justified” killing. Even if one kills in self-defence, it is still a sin to be repented of, and so if Kalashnikov indeed repented as was reported, his spiritual father should not have tried to minimise the sin, but rather spoken to maximise God’s mercy.

That is what I see from most of the wise spiritual fathers. They never try to minimise the seriousness of sin, but always speak of the greatness of God’s love and mercy.

So that was what got me thinking about justice and mercy, and it was that discussion that made me think that we should be going forward from justice to mercy, and not going backwards from mercy to justice.

I realise that the “mercy” Thorsten (or rather the person he was quoting) was talking about was so-called “works of mercy”, but in that sense they are indeed works, but without mercy, because works of mercy can only proceed from a merciful heart. Such works of mercy are sometimes called “charity”, but in a context that deguts “charity” of all meaning. One group of protesting workers once carried a sign that said “Damn your charity, we want justice”.

But for Christians, works of “charity” and a struggle for justice can only proceed from a merciful heart.

Opening the Doors of Compassion: Cultivating a Merciful Heart | Incommunion:

Works of mercy can and should extend to efforts to change social structures and policies on behalf of, as well as to advocate for, those who are poor, vulnerable, or treated unjustly. Our works of mercy should express the holistic view of the Orthodox ideal that, as Archbishop Anastasios writes, “embraces everything, life in its entirety, in all its dimensions and meanings…[and seeks] to change all things for the better,” that is, the transformation of all things in a life in Christ.

Justice without mercy quickly becomes vindictive, vengeful and satanic. Satan is, after all, the prosecutor, who wants to take over the judge’s job, because the judge, in his view, is too merciful. Satan and his minions could not understand this, because if they had they would not have crucified the Lord of Glory (I Cor 2:9).

______________________

Notes and references

[1] Stewart, Charles. 1991. Demons and the devil. Princeton: Princeton University Press, p 146.

March 29, 2017

A tale of another dystopia

The Red Coffin by Sam Eastland

The Red Coffin by Sam Eastland

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I read this book only three years ago, and could not remember it at all. It was like reading a completely new book. The only scene that triggered any memory at all; was right at the very end.

So what can I say about such an unmemorable book? That I enjoyed reading it the scond time because I can’t remember what I thought the first time? I won’t try to review it, but will just comment on what i thought was one of the saddest scenes in the whole book. Inspector Pekkala is a member of Stalin’s secret police, and the only one who has the trust of Stalin. Twenty years earlier he was an equally-trusted secret policeman of the Tsar. The sad scene has little to do with the unfolding of the plot, but has a great deal to say about the contradictions of living in a totalitarian state.

It is the story of Talia, the little girl whose parents were taken away to the Gulag, though they were good communists. So she lives with her grandmother in the same building as Pekkala, Stalin’s special investigator. Talia comes to call Pekkala to have tea with her grandmother, wearing her Young Pioneers uniform, which she still wears, even through her membership was revoked when her parents were arrested. That is the saddest story in the book.

And Pekkala goes to have tea with Babayaga, and finds her cutting up newspapers, or rather cutting out small pieces, with nail scissors. She was planning to use the newspaper as toilet paper. She said she is cutting out Stalin’s name, because she heard about a man who used old newspaper for toilet paper, and when the police came to search his house they found some in the toilet, and arrested him because it had Stalin’s name on it. That she should happily tell this to Stalin’s own special investigator is one of the most self-authenticating parts in the book.

March 26, 2017

“Capitalism as religion”

The Society of Sacramental Socialists

The Society of Sacramental Socialists

“A religion may be discerned in capitalism — that is to say, capitalism serves essentially to allay the same anxieties, torments, and disturbances to which the so-called religions offered answers… In the first place, capitalism is a purely cultic religion, perhaps the most extreme that ever existed. In capitalism, things have a meaning only in their relationship to the cult; capitalism has no specific body of dogma, no theology. It is from this point of view that utilitarianism acquires its religious overtones. This concretization of cult is connected with a second feature of capitalism: the permanence of the cult. Capitalism is the celebration of a cult sans rêve et sans merci (without dream or mercy). There are no “weekdays.” There is no day that is not a feast day, in the terrible sense that all its sacred pomp is unfolded before us; each day commands the utter fealty of each worshipper…

View original post 260 more words

March 22, 2017

An Embarrassing Confession: I Liked The Shack | A Pilgrim in Narnia

One of my fellow bloggers, Brenton Dickieson, writes that he liked The Shack. I thought his post was an ideal opportunity to practise Audi alteram partem (no, it’s got nothing to do with your vorsprung durch Technik, you know, it simply means “Hear the other side”). So here’s how he began, with a link to his post, so you can see what he’s leading up to. .

Anyone who knows me personally knows that I have an allergy to evangelical pop culture art. It is not anaphylactic, but if I get too close to the fiction section in a Christian bookstore, I tend to break out in hives. If someone changes the car radio station to one of those generic, fill-in-the-blank pop worship song Christian cheese fests, I can feel my glands swelling and my breathing starts to constrict. If I were to walk into a house decorated with “Christian” art supplemented with motivational sayings–because the best art of history needed the point driven home, after all–I have to take an antihistamine and have a little lie-down.I don’t do well with what North American evangelicals insist in calling “art,” and this is especially true of the genre I know best: storytelling.

Source: An Embarrassing Confession: I Liked The Shack | A Pilgrim in Narnia

As for me, I didn’t like The Shack, and my contrary review is here. In fact the opening paragraph of his review, quoted above, is a pretty good description of how I felt when I tried to read it.

[image error]And my reaction to The Shack was stronger than it was to the other literature in that genre. I read a few books by Frank Peretti, and they weren’t a patch on Charles Williams — again, like The Shack, there was that crude materialism and anthropomorphism. But I’d still give Frank Peretti’s books two stars on Good Reads, and I only gave one star to The Shack.

So the only thing I can say now is read it for yourself. You may love it, you may hate it, or you may just find it boring.

March 17, 2017

Novelty and innovation

This morning at TGIF Duncan Reyburn spoke on novelty and innovation, and how people respond to this.

As often happens in lectures, my mind wandered to think of examples, and my own responses to what he was saying.

One of the things that Duncan was saying was that Hegelian dialectic was an example of innovation.

Thesis –> Antithesis –> Synthesis

The Antithesis is the innovation, and the Synthesis is the response to the innovation, which, even though it may reject the innovation, is nevertheless changed by it. It cannot simply go back to what it was before.

An example that occurred to me was the Ecumenical Counciils. They did not simply convene to establish doctrines. There was a Thesis — the Gospel, an Antithesis — Heresy, and a Synthesis, formulated doctrine, which though it rejected the heresy, did not simply go back to the status quo ante.

Duncan himself, as a Chesterton scholar, gave the example of Chesterton’s book Orthodoxy, where Chesterton said he was trying to invent a new heresy, but found it was Orthodoxy all along.

I recalled a discussion on Facebook a few days earlier, on the difference between Gospel and Canon, part of it reproduced below:

Tim Fawcett: The Gospel is the core message of Christ. The creeds are more about establishing theological orthodoxy. Fundamentally the creeds are about narrowing the gate to heaven and setting the church that establishes them up as gatekeeper. Creeds are about keeping people out of the Kingdom not letting them in.

Steve Hayes: The Gospel is the good news of who Jesus Christ is and what he has done. The creeds were formulated to counter specific distortions of the Gospel. Before those distortions appeared there was little need for creeds. The distortions were mostly about who Jesus Christ was,, and what he was, and this in turn altered what people thought he did.

I simply cannot understand Tim Fawcett’s point, which seems utterly remote from the Ecumenical Councils, and seems stuck in siome 19th century Western time warp. But then my response was expressed in terms of Hegelian dialectic, which is also a product of 19th century Western thought.

But still, if one is thinking of innovation and response to it in terms of Hegelian dialectic, I think the Ecumenical Councils are a good example, and perhaps explain the rather confused response to the Pan-Orthodox gathering held last year in Crete. It didn’t seem to be Hegelian enough, in that it wasn’t called to deal with a specific heresy.

Another thread of thought that was sparked off by Duncan’s paper on innovation was my own response to electronic computers, which appeared in my lifetime. Computing has evolved quite a lot since I got my first microcomputer 35 years ago, back in 1982. Which innovations did I welcome, and which did I ignore or resist?

My first encounter with computers was when I went into the office of the United Building Society in Pietermaritzburg in 1969, after having been overseas for a couple of years, and instead of the machine that entered transactions in my passbook and duplicating them on a physical ledger card, it contacted a remote computer and entered the three years of interest as well. I was fascinated by this device in which you could enter information, and recall it again at will. I wanted one. But only an institution the size of a building society could afford a computer.

This was what Duncan Reyburn had described as a link between stage magic and innovation, also comparable to dialectic.

Something –> the Turn –> the Prestige

The beginning is where the magician shows you a canary in a cage. The Turn is where the canary disappears. The Prestige is when it reappears.

And so it was with the computer in the building society — the data disappeared into a machine, and the device regurgitated it as if by magic, even if it was in a completely different branch of the building society. Previously you could only transact at the branch that held the phyical ledger card,

Then I read about the Atex Publishing System, installed in one of the Durban newspapers. One of the journalists wrote about it, and I wanted one. The thought of being able to store information and find it again sounded marvellous. But I wasn’t a newspaper publisher either, so it seemed out of reach.

[image error]

NewBrain micro-computer, 1982

Then in 1981 I saw a computer magazine at the newsagent’s, and I bought one. There were descriptions of micro-computers one could use at home. I went, with some others, to an exhibition of educational technology, Instructa ’82, in Johannesburg. There was, on display, an Atari home computer, with BASIC in ROM. I played with it. I typed on the keyboard, pressed the enter key, and that was the Turn. I typed “Print X” and lo, the Prestige! What I had typed appeared, as if by magic, on the screen. So I ordered a NewBrain micro-computer, which was delivered to us in Melmoth in October 1982. It has 32K of RAM, (an enormous amount in those days) but there were no programs written for it, so it couldn’t do what I wanted. And so I eagerly awaited the next innovation.

So from 1982 to 1987 I was what the sociologists called an “Early Adopter”. I was eagerly awaiting every innovation that would make computers more useful. And after 5 years that point was reached. We got an MS-DOS computer, and there were lots of shareware programs available. One of them was a family history app, which allowed us to store genealogical information and spit it out at will.

By then I was working in the Editorial Department at Unisa, which used the Atex Publishing System I had coveted so much 7 years earlier. It had disk drives the size of a small washing machine. And saving a file and getting back to the same place could take several minutes, or sometimes long enough to go down to the canteen for coffee. Some of the developers of Atex ported it to micro-computers as the XyWrite word processor, which was much more efficient and faster than Atex, and could do everything I wanted in a word processor.

And from that point on I became suspicious of innovation.

One innovation was the “enhanced” (ie ergonomically crippled) keyboard, with function keys along the top instead of on the left. It slowed down typing and editing, and operations that had previously required two fingers now required two hands. Innovation meant that instead of doing things the quick and easy way, one now had to do them the slow and difficult way. People said that this was progress, and that we should stop complaining and “move on”.

But I stopped being an “early adopter”. People said that MS-Word and Wordperfect were the word processors to beat, and we should switch to them, but XyWrite could do everything they could do and a lot they couldn’t do, and a lot faster too.

Now I fear that my 32-bit computer will die and have to be replaced, and I’ll only be able to get one with a 64-bit operating system, and I know that half the programs I use every day will not run on them.

So I’m ambivalent about technical innovation. Will it make my life easier, or more difficult? Will this new computer do everything that my old one does, or will it drop a lot of functionality in the name of “Progress”?

Innovation that lets me do what I want to do is good; innovation that stops me doing what I want to do is bad.

Duncan also said that novelty is tied up with loss of identity, or fear of losing one’s identity. Does that mean that I gained a new identity 30 years ago, when I became quite dependent on computers swallowing data and spitting out again, like a stage magician with a canary in a cage?

Val said she had a different train of thought about that.

About 20 years ago there was an advertisement hoarding in Bramley in Johannesburg on the M1 North. We used to pass it a couple of times a week coming home from church. It was advertising 702 radio, and had a picture of the Statue of Liberty, with the text “News from a broad”.

On one occasion we had a visiting American priest with us, who was doing a locum for the priest in our parish, and he was terribly upset by it. For us it was just a mildly amusing pun, but he experienced it as an attack on his identity.

Where does innovation come into that?

Well Duncan explained that jokes, like stage magic, were also examples of innovation.

March 10, 2017

Vaccination polemics in a post-truth world

For the last couple of years I have been vaguely aware of some sort of controversy over vaccination in the USA. I didn’t pay much attention to it because, as far as I was aware, it wasn’t controversial here, and most people (with some exceptions I’ll refer to later) accepted vaccination as a normal health precaution for certain diseases. It seemed to me that people who were raising vociferous objections to it were creating the proverbial storm in a tea cup.

But today I read something written by an Orthodox priest who said that he had recently discovered that one of his parishioners had applied for exemption from vaccination on “religious” grounds. The priest asked if there was anything, such as an authoritative statement by Orthodox bishops, to indicate what those “religious grounds” were.

In reply someone posted a link to this article — NY court lets woman refuse vaccine made with aborted baby tissue / OrthoChristian.Com:

An Orthodox Christian woman has won the right to refuse a vaccine developed using aborted babies’ tissue, based on her religious beliefs.

The vaccine is for measles/mumps/rubella and is required by New York City law for all schoolchildren. It was developed from fetal tissue procured from abortions, hence the moral dilemma for practicing Christians.

The woman, who remains anonymous, said her Christian beliefs against abortion compel her to have nothing to do with vaccines made using aborted fetal tissue.

That put a different complexion on the issue. It seemed to me that it wasn’t a simple Yes/No issue, but there were several shades of grey. Apart from anything else, it was news to me that some vaccines were made from aborted human babies.

I thought I needed to verify that claim. The article was from a source that cited another source. The intermediate source LifeSiteNews.com is a polemical site with an axe to grind, and so I wanted to find something more impartial. But it turned out that that was easier said than done. The headline spoke of a court, but the body of the article did not name a judge, but an official of the education department.

So I did a web search to see if I could find an article that could verify the story. I found an article on a site called “Science-based Medicine” which I hoped could either verify or refute the story, but it turned out to have far more intemperate polemical ranting that the other site, and was anything but scientific — “Aborted fetal tissue” and vaccines: Combining pseudoscience and religion to demonize vaccines – Science-Based Medicine:

Overall, the view that somehow vaccines whose virus strains are grown in these two cell lines are the product of pure evil seems to rely on a magical thinking that an evil (in the view of those who oppose abortion) from over 50 years ago continues to taint these cell lines over hundreds of passages seems rather like the law of contagion in sympathetic magic, more than anything else.

That’s not science, it’s ideology.

So the Google search was to no avail; all I could find was ideological rhetoric, on both sides.

So I post this here in the hope that someone reading it might be able to point me to some factual information about the assertion that some vaccines are made from aborted fetuses, preferably without the partisan polemical rants from either side.

I said at the beginning that vaccination was uncontroversial in South Africa, with some exceptions. I am one of the exceptions, as I was never vaccinated as a child. My father was a conscientious objector to vaccination, what the Americans call an “antivaxxer”,and he got whatever authorisations and exemptions were needed so that I could go to school without being vaccinated. He never discussed his reasons for this with me, but I do know that he was a convinced atheist and something of a health fanatic. He was a biochemist by profession, and used to read me bedtime stories out of his biology textbooks, where the illustrations of sea urchins and liver flukes looked far more fantastic than any mere human conception of extraterrestrial alien life. My own theory, looking back, is that my father was a bit of a Darwinist. If you got the diseases that the vaccines were supposed to protect you from, your immune system was there to overcome them, and needed to be exercised by overcoming them. If it failed to so so, then you weren’t among the fittest who survived.

[image error]I never saw the exemption certificate, and in any case it was not recognised by any gover4nment beyond the borders of South Africa, and when, in the middle of 1964, it became necessary to have a passport to travel to Lesotho, and proof of a smallpox vaccination, I got myself vaccinated, since I did not know the reasons for my father’s objections, and had none of my own. Because I had not been vaccinated before, I had to go back after 10 days to make sure it had “taken” before they gave me a certificate. In the mean time, as a result of not having been vaccinated before, I was sick as a dog, and spent several days in bed. Cowpox, I suppose.

When I was 13 our school holidays were extended by a week because of a polio epidemic, and I knew several people who had had polio and had to walk with the aid of leg braces. A few months later a vaccine for polio was developed, too late for those already crippled by the disease, but one heard of no more epidemics.I was never vaccinated against it myself, but our children were.

Almost every year we get circulars from our medical aid urging us to get vaccinated against influenza.I can understand their reasoning — the vaccination, which you can get at the chemist, is cheaper than the cost of a doctor’s consultation. But I suppose I’m enough of my father’s son to be sceptical of the efficacy of such things. Unlike things like polio and smallpox, influenza viruses seem to mutate so rapidly that a vaccine against one strain doesn’t seem to be very effective against another.

So when it comes to vaccination, I’m neither excessively pro- nor obsessively anti, in principle. It’s the kind of thing one needs to be about to make informed decisions about, but, because of the fanatical pro- and anti- views in the USA, it seems to be very difficult to get the information one needs to make informed decisions, because all the information is so wrapped up in propaganda that it is very difficult to distinguish facts from polemics.

March 8, 2017

Veil of Darkness

Veil of Darkness by Gillian White

Veil of Darkness by Gillian White

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

I’d finished all my library books and was looking at the bookshelves for some bedtime reading and my eye lit on Veil of Darkness, just as the protagonist’s eye in the story had lit on a book on a shelf, a book called Magdalene. Veil of Darkness had sat on our shelves for 16 years, and I had never read it. We bought it at a sale for R20.00, shelved it and forgot it.

Kirsty Hoskins, fleeing from an abusive husband, gets a summer job as a chambermaid in a Devon hotel. On her way down there on the train she meets two other women who are hoping to forget males who have hassled them, Avril, whose ne’er-do-well brother is about to be released from prison, and Bernadette Kavanagh, trying to get over being jilted by a posh boyfriend, whose parents thought she wasn’t good enough for him. They all end up sharing a room in the staff quarters of the hotel.

The thing that frist got me about this book so far was that it could so nearly have been an alternative story of my life. When I arrived in England in 1966 as a penniless student without a work permit in 1966, someone said that foreigners could easily get jobs in the catering industry, and I had one lined up as a kitchen boy in a Devon hotel at £7 a week all found, and the man was pressing a rail voucher on me, and just in time I got offered one driving buses for London Transport. It was so close.

So as I read I kept thinking, so this is what it would have been like.

And then Kirsty discovers The Book…

I’d also just posted something about the 2017 Reading Challenge Meme | Notes from underground, and I was thinking of including this book as “a book in a genre you usually avoid”.

From the beginning it seems to be chicklit, or women’s fiction, a genre in the GoodReads “Compare Books” function that always comes up blank for me. Three women trying to escape from obnoxious males — that surely fits, doesn’t it?

But then Kirsty discovers The Book…

The Book seems to be a classic Gothic horror novel, featuring a nun who plots revenge. And that is about as much as we are ever told about it. After Kirsty reads it she and her roommates start having thoughts of revenge and standing up to their persecutors. So perhaps it’s not chicklit, but a Gothic horror novel, and that’s not a genre I usually avoid.

Having finished it, I shift its genre again. It is “a book about books or reading”. The book featured in the story, Magdalene is a Gothic horror novel, certainly, but Veil of Darkness isn’t. Or is it a Ruth Rendell-type whydunit psychological crime novel?

After reading The Book Kirsty gets the idea of doing a rewrite job on it, and publishing it under her own name. Avril, the typist at the hotel’s reception office, agrees to type it up, and when Kirsty realises, almost too late, that she can’t publish it under her own name because then her husband might find her, Bernadette agrees to take the public and publicity role.

And that is where it becomes unconvincing, and drops from three stars to two. The idea that Kirsty, who has only ever read Mills & Boon, could do a rewrite job on an old out of print book and turn it into a literary masterpiece is way too far-fetched.

What happens next would be too much of a spoiler, but I found it had more plot holes than The da Vinci Code. It falls a long way short of Ruth Rendell‘s psychological crime novels, where every event seems to lead inexorably and inevitably to the next, sliding down into the commission of a crime. This seems more like a series of random events with only the vaguest hint of causation.

It had enough interest to keep me reading to the end just to see what happened (and not just, like The da Vinci Code and Interview with the Vampire, so that I could say I had actually read them to people who might say “But you can’t criticise a book you haven’t read”). This one wasn’t that bad, but it wasn’t all that good either.

And I’m still not sure what genre it belongs in.

March 5, 2017

My children’s novel free for a week

My children’s novel Of Wheels and Witches is available for 100% discount from March 5-11, to mark “Read an e-book Week”. It normally sells for US$2.99, but for this week it will be free if you go to the site and enter the coupon number when you check it out.

In the story a Johannesburg schoolboy goes to spend the school holidays at a farm in the Drakensberg. There he meets three other children from different backgrounds. They have fun riding horses and exploring caves, until they encounter an ominous symbol of a wheel, and through a witch they learn of a plot to harm the father of one of them and they embark on a cross country journey to warn him.

You may read more about the background to the story here A children’s novel about apartheid | Khanya. It’s intended for children aged about 9-11, but those over 18 might also like it.

The promotion begins at 10:01 am on Sunday 5th March, and ends at 09:59 am on Sunday 12 March (South African time). For one week only, thousands of Smashwords authors and publishers will provide readers deep discounts on ebooks, with coupon code levels for 25%-off, 50%-off, 75%-off and FREE. You can find more about it here

If you are a reviewer of books, on blogs, or journals, or anywhere else, please use this opportunity to grab yourself a free review copy.

So get it here, if not for yourself, then for your children, or grandchildren or godchildren. Encourage them to write reviews of it to saw what they liked about it, what they didn’t like about it, things they didn’t understand, and what they learned from it that they didn’t know before. And if anyone wants to write a review on Good Reads, you can find it here.

March 4, 2017

South African Orthodox Liturgical texts and music

The following Orthodox liturgical texts and music are available for download from my Dropbox public folder until 15 March 2017.

On 15 March Dropbox is again reducing its functionality, and the public folders will no longer be public, so if you think you might find these things useful, please get them now.

Obednitsa in North Sotho & English (Typica, Readers Service), sung by Mamelodi mission congregation. This service is used on Sundays in mission congregations where there is no priest.

Divine Liturgy in English, recorded at St Nicholas of Jaban Orthodox Church in Johannesburg

Text of Obednitsa in North Sotho and English (for use on Sundays where there is no priest)

Please note that these links will no longer work after 15 March 2017. If possible, please “like” or “share” this page on Facebook, Twitter, etc, even if you yourself maight not have any use for these texts, so that as many people as possible who are interested can know about them

For more information about the Obednitsa service, see here.

[image error]

Pascha in Mamelodi 2010 — some of the people who sang in the recording

March 3, 2017

Neoinklings: Bonhoeffer, Coetzee and more

Yesterday we had our 13th Neoinklings literary coffee klatsch and today (3 March) it’s a year since we started, and we had a new member, Sheila du Plessis who has written a number of booklets on family life, and has ideas for writing several novels.

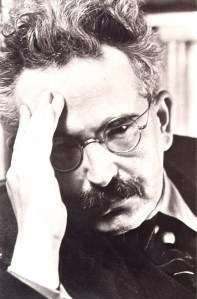

[image error]

Motiv 2 von 3

Aufnahmedatum: 1939

Aufnahmeort: London

Systematik:

Geschichte \/ Weltkrieg II \/ Krieg in der Heimat \/ Deutschland \/ Widerstand \/ Bekennende Kirche \/ Bonhoeffer","created_timestamp":"0","copyright":"bpk \/ Rotraut Forberg","focal_length":"0","iso":"0","shutter_speed":"0","title":"","orientation":"1"}" data-image-title="bonhoeffer1" data-image-description="" data-medium-file="https://khanya.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/bonhoeffer1.jpg?w=300&h=249" data-large-file="https://khanya.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/bonhoeffer1.jpg?w=422" class="size-medium wp-image-10121" src="https://khanya.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/bonhoeffer1.jpg?w=300&h=249" alt="Dietrich Bonhoeffer" width="300" height="249" srcset="https://khanya.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/bonhoeffer1.jpg?w=300&h=249 300w, https://khanya.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/bonhoeffer1.jpg?w=150&h=124 150w, https://khanya.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/bonhoeffer1.jpg 422w" sizes="(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px" />

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Tony McGregor had been reading books by and about Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German theologian murdered by the Nazis, and that led to several spin-off topics. Among other works he had been reading Eberhard Bethge’s biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, which I had read some 45 years before, when Eberhard Bethge visited South Africa.

Bethge gave a series of lectures at the University of Natal in Durban, which I was unable to attend, being banned at the time, but I did get to meet him when he came round to the place where I was staying, and talked ot a smaller private gathering. Here is my diary entry for 12 February 1973, perhaps worth recording:

Eberhard Bethge, Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s friend, came for lunch. He is here to give a series of lectures on Bonhoeffer’s life and work. I talked to him about the Confessing Church in Germany, and was amazed to discover how free the church was in many respects. The Nazi regime, one thinks, was so repressive that one is amazed to hear of pastors at work and life going on. I suppose it’s similar to the Juds’ reaction, coming here. They expect everything to be consistently bad. Bonhoeffer was banned from Berlin, but later was allowed back to visit his parents, provided that he didn’t preach. I can’t imagine the Minister of Justice giving me permission to go down to the Transkei to see my mother. Some of the similarities are remarkable. Bethge also said that there were notable differences: the press is relatively freer here, while in Germany it was much more harshly controlled. He said that in Germany they had had more hope, because they felt that Hitler couldn’t last. Here we have had the Nats for twice as long, and the end is not in sight. He said that he was, however, under the impression that there was a gradual improvement, and that things were getting better. But I told him that is not so. Every year more and more repressive legislation is added to the statute book, and none of it has been taken way. Practically every change has made it more repressive, and not less so.

He and his wife Renate were a fantastic couple, and it was great to talk to them. I told him a little of my experience of the Lutheran Churches in South West, and how their attitudes had changed dramatically after the World Court opinion in 1971. They stayed for lunch of toasted cheese sandwiches, and I gave them a copy of my banning order.

One of the things he mentioned was that he found South African audiences very different from those in Europe and North America. In those places they were most interested in Bonhoeffer as a daring radical theologian, changing theology to bring it up to date in the modern world. But South African Christians were most interested in the Confessing Church, and resistance to the Nazi ideology. He had not been aware of that before he came, and so had not prepared his lectures to deal with those issues. Audiences in Europe and America were not interested in the Confessing Church other than as a background to Bonhoeffer’s life and thought, whereas in South Africa it was the other way round — South African Christians were interested in Bonhoeffer precisely because of his role in the Confessing Church, and the light it could throw on that. First World boss-nation theologians were interested in the man because they saw him as changing theology. Oppressed and downtrodden people were interested him because they saw him changing the world.

Bethge dealt with this very point in his biography, when he wrote:

The concern of the Western ecumenicals was largely determined by practical — that is to say, political — considerations; consequently, when the struggle became a tedious contest for the confession, their interest flagged, to flare up again as soon as there was any sensational news of police action in Germany. Holding the political views he did, Bonhoeffer could easily have won over ecumenical sympathy. Instead he began his campaign against ‘heresy’ and thus found himself in notable isolation. There were very few people — and one of them was Bell — whose minds he had really been able to prepare for this crisis; in the eyes of the rest he merely seemed to have an awkward disposition to orthodoxy.

And this was one of the points that we discussed.

Until about 1968, South African Christian opposition to apartheid was largely based on practical political considerations. It was applied in an unjust way, it caused suffering, and therefore needed to be opposed. Only a very few in South Africa thought like Bonhoeffer, in terms of apartheid as a heresy. Tony said that one of them was his father, who had grown up in the Dutch Reformed Church as the son of a dominee. But when he saw an article claiming that apartheid was biblical, that was the last straw, and he left.

But in Germany it was the other way round. Before the oppressive nature of Nazi rule became apparent, people like Bonhoeffer saw that it was ideologically incompatible with the Christian faith. In South Africa, people like Trevor Huddleston attacked the theological underpinnings of apartheid in the 1950s, but they were lone voices.

The problem with this “practical” opposition to apartheid was that it left open the possibility that it would not be objectionable if it were implemented in a “just” way. The theological objection said that there could never be a just version. It was evil in its fundamental presuppositions. The theological objections were finally made explicit in A message to the people of South Africa, made public in 1968. The “Message” went further than calling the apartheid ideology a heresy; it said it was a pseudogospel making a false offer of salvation by race, not grace.

One of the difficulties we (and many other South Africans) had in understanding the Confessing Church in Germany was, as Tony said, that Bethge wrote of the Lutheran Church and the Evangelical Church as if they were different entities. It seemed that the “German Christians” (who supported Nazism) were a faction or party within the state church, rather than a separate denomination, but it was not clear from Bethge’s biography, whether the Confessing Church was likewise a party within the state church or a separate denomination.

There is perhaps material for a doctoral thesis in the notion of a Confessing Church in South Africa in the 1960s, 70s and 80s. There was quite a lot of talk about it in that period, and in 1968 there were reports of several “obedience to God” groups being formed, but they seemed to vanish. Perhaps someone has already written a thesis on it.

One of the branches of the conversation was that Tony told us more about his father who had left the Dutch Reformed Church. His McGregor ancestors had been Scottish ministers who had been brought to the Cape Colony when it came under British rule, and Dutch Reformed clergy could no longer be got from the Netherlands, so the governor, Lord Charles Somerset, brought them from Scotland instead. The towns of McGregor and Robertson in the Western Cape were told after his ancestors.

He told a story of when his father, when he was about 5 years old, was made to wear a kilt by his grandfather. Tony’s grandfather was then the dominee at Sea Point, and they went in to Cape Town on the bus, and Tony’s father was complainimng about having to wear the kilt, and was told that that was what Scotsmen wore, and he said “Ek is nie Skots nie, ek is Afrikaans”, which made everyone on the bus laugh.

Sheila said he should write such stories down, and we talked a bit about such family stories, and why they should be recorded before they are forgotten. Blogs are good for that.

I had recently been reading books by J.M. Coetzee, who has won several international literary prizes, mostly overseas. None of us found his novels particularly good or inspiring, and we wondered if his reputation outside South Africa was higher than his reputation within the country. I’ve written more about that here.

Sheila asked for some comments on the design of the cover for one of her family life booklets, and I hope our advice was good.