Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 30

August 4, 2017

Literary coffee klatch: witchcraft, demons, and war

Yesterday we gathered at Cafe 41 in Arcadia for our monthly literary coffee klatsch. Tony McGregor had a book, The mystery of the solar wind, by Lyz Russo, which is currently free on Smashwords. Tony said it was about pirates in the 22nd century, which reminded me that I had just finished re-reading Swallows and Amazons, which is about children camped on an island in a lake playing at pirates.

[image error]In my review of Swallows and Amazons I noted that as a child I preferred books about children being captured by real pirates, rather than playing at being pirates, and compared their island camp with that in Lord of the Flies, though that was really written for adults. But I had also been reminded of another book about children and pirates, which I had also read 50 years ago, A high wind in Jamaica by Richard Hughes. That book had helped me come to terms with the culture shock I experienced on first going to England.

David Levey then joined us, and we continued the discussion on witchcraft in literature and life from the previous meeting.

David was asking about the difference between witches and wizards, and other terms for similar phenomena. Books like the Harry Potter books and others in the genre have helped to reinforce the impression that wizards are male and witches are female, which can be misleading. I don’t really have much to add to what I wrote here 20 years ago Christian Responses to Witchcraft and Sorcery:

But what are witchcraft and sorcery? Anthropologists like to distinguish between them, and use them as technical terms. They regard “witchcraft” as the supposed power of a person to harm others by occult or supernatural means, without necessarily being aware of it. The witch does not choose to be a witch, and the supposed harm does not necessarily arise from malice or intent. Sorcery may be learned, whereas witchcraft is intrinsic. A sorcerer may use incantations, ritual, and various substances in order to do harm, while a witch does not (Hunter & Whitten 1976:405-406; Kiernan 1987:8). While this is a convenient and useful distinction for anthropologists to make, normal English usage is not as clear-cut, and the terms have often been used interchangeably (Parrinder 1958:18). In newspaper reports of recent witch hunts in South Africa, for example, the terms “witch”, “sorcerer” and “wizard” are often used to translate the Zulu umthakathi or the Sotho moloi. And English speaks of “witch hunts”, rather than of “sorcerer hunts”, though very often those who are hunted would be technically described by anthropologists as sorcerers rather than witches.

If one makes the anthropologists’ distinction, then witchcraft is similar to belief in the evil eye, which is found in many countries around the world, and is common among people in the Balkans. Val recalled that when we visited Albania in 2000 there were lots of recently built houses still under construction, and as soon as they reached roof height teddy bears and other soft toys were nailed to them to ward off the evil eye. There were many different kinds, not only teddy bears, but Disney characters and and an occasional Pink Panther. To non-Albanians they seemed rather spooky and scary, and many visitors remarked on them. They were called dordolets. Greeks also believed that one should never say complimentary things about someone’s new baby, as that could put the evil eye on the child, and one would have to spit three times to ward it off if one inadvertently said something nice about the child.

In most traditional African cultures evil is attributed to human malice. Under the influence of Christianity the concept of an evil spiritual realm, of demons and the devil, has intruded. Witches may be male or female. The anthropologists’ distinction between witchcraft and sorcery is based on some African cultures that make such a distinction, but many others don’t.

This is illustrated by a discussion between a Christian missionary and an African diviner (Kirwen 1993:53):

The issue of the symbolization of evil as witch or devil divided us. For Riana, in a very real sense, everyone potentially is a witch. The witch is ‘you who are immoral’. This refined moral sensitivity of the Africans should be a revelation to Western theologians who have tended to see traditional religious morality as impersonal and taboo-oriented. The fact that the witch is potentially any person shows how African morality is grounded in relationship within the human community, and how it stresses, immeasurably, the moral responsibility of each and every individual. There is no ‘The devil made me do it’ excuse in the African world. The devil of the Christian religion is part and parcel of the two-world cosmic vision of Christianity. The devil functions as the evil link between the two worlds, reinforcing the belief that the ultimate solution to evil takes place outside this limited human existence.

There is often confusion among white people between a witch and a witchdoctor. The witchdoctor is not the same thing as a witch, but rather someone who specialises in detecting and curing the problems caused by witchcraft. The Zulu isangoma is a diviner, or soothsayer, a diagnostician. One who specialises in smelling out witches is an isanuku. Of course it is possible for a sangoma to “go over to the dark side”, as it were, just as a security guard can be in cahoots with burglars.

David also asked about the concept of the “good witch”, but I believe that arises from confusion with a herbalist. The Zulu word for that is inyanga, which is someone who has a specialist knowledge of healing herbs, and also, of poisons. So the inyanga too can “go over to the dark side”. The inyanga is a pharmacist, and in Galatians 5:20, among the sins listed is witchcraft, a translation of the Greek pharmakeia.

[image error]The English word wizard is of quite different derivation, and essentially means a wise person. David commented that in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings there were both good and evil wizards — good ones like Gandalf and evil ones like Saruman. But in theological terms the “wizards” in Middle Earth were not humans, but Istari, who were angelic beings, though in the Quenya language “Istari” means wise ones. And in the Arthurian legends Merlin the wizard is of mysterious origin, not entirely human, and some say at least partly demonic.

We didn’t exhaust the point of the nature of wizards in literature, especially in pre-modern literature (ie not Harry Potter, Dell Comics, or The Wizard of Oz) but moved on to demons.

In the Christian worldview demons held much the same place as witches in traditional African worldviews. For me it called to mind the contrast between Christian experience in South Africa and England 50 years ago. When I went to England in 1966 to study theology the first essay I was asked to write was on “Jesus and the demons”. I read my essay to the principal of the college, and at the end of it he said “But you haven’t told me whether you think the demons exist”, and I thought that was as irrelevant as someone, having just been run over by a bus, debating whether the bus existed. Someone I discussed this with later, back in South Africa, said, “Yes, it doesn’t matter what the demons are. What matters is that Christ has the mastery of them. This is the brief version of that anecdote; if you’d like the details, see Of babies and bathwater: English theological and ecclesiastical reformers | Notes from underground.

A demon or daemon (δαίμων) in ancient Greece was a lesser deity, and in Christian usage the term came to be applied mainly to fallen angels. of whom the devil or satan was the chief. What they are and how they operate can be conceived in many different ways. In the New Testament some people were oppressed by demons, and quite a large part of our Lord Jesus Christ’s ministry was taken up with casting out the demons and setting people free from their influence (the topic of my essay, mentioned above).

But there are also corporate demons, demons of groups of people, and nations. In South Africa one could see racism and apartheid as demonic powers that oppressed people and needed to be driven out. Some have come up with the concept of egregores, a kind of spiritual power or group mind that arises from a group of people doing something together, so that the whole becomes greater than the sum of the parts. Janneke Weidema said that Quaker meetings could be seen in this way. A group of people gather, and the gathering becomes more than the individual people who compose it.

I’ve also written more on the topic of egregores and angels here Of egregores and angels | Notes from underground and here Angels and demons and egregores (book review) | Khanya.

[image error]Janneke Weidema told us the story of the Flying Dutchman. There was a ship’s captain who wanted to sail on Good Friday, and when the mate remonstrated with him for that he tossed the mate overboard, and vowed to sail even if he had to sail forever, and he was indeed doomed to sail forever and never make port. The captain of the ship seemed to create his own demon that drove him to evil.

She also told us about the importance of St Martin in the Netherlands. St Martin is said to have given his cloak to a beggar, so Dutch children go around asking for gifts on his feast day. That reminded me of St Martin’s role as the patron saint of conscientious objectors, and Janneke promised to tell us more about Quakers as our next meeting.

August 2, 2017

Best books you’ve read this year

What’s the best book you’ve read in the last year? With our literary coffee klatsch coming up tomorrow, I thought this was a good question asked here Book Geeks Anonymous – I cannot live without books. – Thomas Jefferson:

This list started with a question asked on Twitter:

I chimed in with my response, but today, I thought I’d elaborate on the answers I gave. And because I found it too hard to pick only one book, I decided to name one from each of the three main genres.

And, like the book geek, I didn’t like to think of just one book, so I thought I’d list a few of them.

That hideous strength Lewis, C.S.

The moon of Gomrath Garner, Alan.

The Chapel of the Thorn Williams, Charles.

Captain Corelli’s mandolin De Bernières, Louis.

The kite runner Hosseini, Khaled.

The silver chair Lewis, C.S.

Elidor Garner, Alan.

Inside Prince Caspian Brown, Devin.

I didn’t know you cared Tinniswood, Peter.

Adam Bede Eliot, George.

Kim Kipling, Rudyard.

The Night Ferry Robotham, Michael.

Young romantics: the Shelleys, Byron, and other tangled

lives. Hay, Daisy.

The life and times of Michael K Coetzee, J.M.

Teach Yourself Writing for Children and getting published Jones, Allan Frewin; Pollinger, Lesley.

Borderliners Hoeg, Peter.

Disgrace Coetzee, J.M.

The owl service Garner, Alan.

The Grand Sophy Heyer, Georgette.

The subtle knife Pullman, Philip.

Those are probably not objective evaluations, just how much I liked them, and in compiling the list, I was surprised to see that 8 of those 21 were books I was rereading, some for more than the second or third time.

The Book Geek divided them into genres:

Fiction: Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

Nonfiction: Miłosz by Andrzej Franaszek and The Fellowship by Philip and Carol Zaleski

Poetry: Dancing in Odessa by Ilya Kaminsky

So what were the best books you have read in the last 12 months?

July 26, 2017

Love the sinner, hate the sin

I was once chatting with a couple of friends, two of us were Christians, and the third was a catechumen, exploring the Christian faith for the first time, and she had lots of questions. She had been told that Christians should give thanks to God for everything and in all circumstances, and that puzzled her.

“How can you give thanks to God for Mr Vorster?” she asked.

Without thinking, I replied, “You can thank God for giving you Mr Vorster to love.”

And immediately I wondered, where did that come from? Why did I say that? Did I really say that?

I thought perhaps it may have been the Holy Spirit, what St Paul calls “a word of wisdom” (λόγος σοφίας) in I Corinthians 12:8. It was directed to me as much as to my friend.

Back then, in 1965, Balthazar Johannes Vorster was the South African Minister of Justice, and he was responsible for the repressive legislation that was turning South Africa into a police state. He was responsible for a great deal of evil — how could one love him? And yet, in putting those words in my mouth, God was telling me that I must.

And the answer could be summed up in the aphorism, Love the sinner, hate the sin.

Our Lord Jesus Christ said, “Judge not, and ye be not judged; condemn not, and ye shall not be condemned” (Luke 6:37). Clearly, he was speaking there of judging and condemning people, not actions, for he also said “Judge not according to the appearance, but judge righteous judgement” (John 7:24).

If we were to judge with righteous judgment, then Mr Vorster’s actions were undoubtedly evil, but it was not our task to judge Mr Vorster. “‘Vengeance is mine’ says the Lord, ‘I will repay'” (Rom 12:19), and St Paul urged “Bless those who persecute you, bless and curse not” (Rom 12:14).

If we are to judge with righteous judgment, then the important question to ask is not who is wrong, but what is wrong. We are to love our enemies, even Mr Vorster.

And when I became Orthodox this was stressed even more strongly: before receiving holy communion, one must forgive everyone. We pray to our Lord Jesus Christ “who came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am first”. If we think that other people deserve condemnation for their sins, then we’ve missed the point: we need to begin with ourselves.

But then a friend referred to the following article. I normally try to avoid stuff on the Patheos web site, but this one, whose conclusion counters everything I’ve learned over the last 50 years and more, caught my attention.

Let’s Be Honest… “Hate the Sin, Love the Sinner” is Really Just Hate

Ask anyone on the receiving end of being loved while their sin is hated. They will tell you it’s the same as being hated – for the exact reasons Gandhi wrote: because it’s virtually impossible to love someone but hate their sin.

We get caught up in judging them, and we feel self-righteous compared to them, we won’t just let the issue be, leave the issue between them and God, but continue to bring it up and try to change it… and so the poison of hatred spreads in the world – just as Gandhi said.

I read it, and it struck me that what it said was evil, very evil indeed. There is so much magnificent truth wrapped up in such appalling falsehoods that it smacks of perversity even to attack its perverseness.[1] And the conclusion is altogether evil.

If one takes that article at face value, then it means that:

One cannot love a corrupt politician without loving corruption too

One cannot love a police torturer without loving torture too

One cannot love a rapist without loving rape too

And going back to the 1960s and 1970s there were lots of people who argued in that way. When people spoke of the injustices done in the name of the government policy of apartheid, some said that yes, justice is important, but we must have reconciliation too. By this they often meant that those who supported apartheid and those who opposed it needed to be reconciled and therefore good and evil needed to be reconciled.

[image error]In 1965, when we had the discussion I referred to above, we were members of an Anglican church in Pietermaritzburg (where we were then students), and one of the priests (who eventually baptised my catechumen friend) used to read from a book, The will and the way by Harry Blamires, which he used to point out the errors of such behaviour. He pointed out that for many Christians the Christian God had been replaced by the god of twentieth-century sentimental theology:

Are we faced with evil whose roots reach down to the depths where angels and demons are locked in mortal combat? Don’t worry, a word of prayer to the god of sentimental theology and we shall be granted the dubious capacity to meet all comers, friend and foe, with the same inscrutably acquiescent grin.

No, saying that “‘Love the sinner, hate the sin’ is really just hate” is thoroughly dishonest, and thoroughly evil.

It seems to belong in the same category of other weird American ideas that lack all logic and indicate a broken moral compass as those who say that saying “All lives matter” is evil and racist. But I’ve discussed that in another article here: How antiracism became racist: all lives matter.

No, if we are Christians we must love the sinner but hate the sin.

We must

Love the oppressor but hate oppression

Love the corrupt politician and businessman, but hate corruption

Love the warmonger but hate war

Love the exploiter but hate exploitation

If we hate the people, we will become like them. And if we love the deeds, we will also become like them.

Notes & References

[1] Blamires, Harry. 1957. The Will and the Way. London: SPCK.

About 30 years ago I lent my copy to someone who never returned it, so all quotations are from memory.

July 24, 2017

Shadows of Shadows of Ecstasy: An Irresponsible Suggestion about Charles Williams’ First Novel | A Pilgrim in Narnia

Brenton Dickieson’s first reading of Shadows of ecstasy has produced an interesting reaction:

I have not yet read most of Grevel Lindop’s definitive biography of Williams, or Sørina Higgins’ work on Shadows of Ecstasy at the Oddest Inkling. So it is absolutely irresponsible of me to give the conjecture that I’m about to offer. Still, I wanted to offer it while it is fresh in my mind and I am absolutely naïve of what critics have said about this book.

My summary of the book after a second reading nearly 20 years ago, now) was:

In a novel set in the 1920s, African armies overthrow colonial rulers throughout the continent, and then launch aerial bombing attacks on Europe. Nigel Considine, a wealthy London financier, appears to be connected in some way with the African forces and their demands, which appear to be that African values take the place of the Western ones of Enlightenment rationalism and empiricism.

Brenton Dickieson doesn’t mention much of that in his review, which I think shows tht Charles Williams’s books strike different people in very different ways.

[image error]In some ways it is my least favourite of Charles Williams’s books, and perhaps I should read it again. From my memories, some of which were reawakened by Brenton Dickieson’s review, it seems in some ways prophetic — the capture and enslavement of a Zulu king by a British financier in the book parallels the capture and enslavement of a Zulu president by a Trinity triumvirate of Indian financiers in real life 90 years later.

What struck me in both my readings was that the book starts off being interesting, and shows promise of being an interesting story, but then gets lost in long passages of Nigel Considine’s ideological claptrap which serve the same function (and are almost as boring) as John Galt’s speech in Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged. But it certainly serves to illustrate what C.S. Lewis said (before Hannah Arendt coined the phrase) about the banality of evil — on the surface, great designs and an antagonism to Heaven which involved the fate of worlds: but deep within, when every veil had been pierced, was there, after all, nothing but a black puerility.

I thought that the most authentic character in Shadows of ecstasy was the African priest, but he disappeared about a third of the way through, and we heard no more of him.

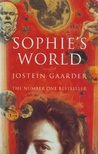

Sophie’s World

Sophie’s World by Jostein Gaarder

Sophie’s World by Jostein Gaarder

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I first read this book 20 years ago, and just finished re-reading it. As I’m sure most people know, it is a compact history of Western philosophy in the guise of a novel. I’d forgotten much of the plot of the fictional part, and it seemed to end differently and more disappointingly than it did the first time I read it.

It reminded me of a few things that I learnt in Philosophy I at university back in 1964, and also reminded me that I was a big fan of Kierkegaard in my teens, and rereading this reminded me why. It also got me thinking — was that a marker of a significant departure? Did young people of my generation choose two different paths — some became fans of Ayn Rand, and others became fans of Kierkegaard?

But the book does not mention Ayn Rand, and nor does it mention the modern/postmodern debate. Not a word about Derrida, Lyotard et al.

July 6, 2017

Witchcraft in literature and life (coffee klatsch)

At our literary coffee klatsch this morning we discussed witchcraft in literature and life, but we didn’t nearly exhaust the subject, so we decided to to continue the discussion next time.

The reason for discussing it was that Duncan Reyburn had published a contribution in a book on witchcraft and demonology, but the book cost far more than most of us could afford, so we asked him to tell us a bit about it and his approach to the subject. I was also struck by the difference between his bibliography and mine in an article on witchcraft 20 years earlier. I dealt with all this in an earlier article, so I won’t repeat it here.

[image error]

NeoInklings Literary Coffee Klatsch: Duncan Reyburn, David Levey, Janneke Weidema, Tony McGregor.

Cafe 41, Arcadia, Tshwane

Duncan’s contribution to the books was about how King James was a being really nasty when he wrote his book Daemonologie in 1597. He interprets it in the light the work of René Girard (1923-2015) and especially Girard’s concept of mimetic desire.

If people imitate each other’s desires, they may wind up desiring the very same things; and if they desire the same things, they may easily become rivals, as they reach for the same objects. Girard usually distinguishes ‘imitation’ from ‘mimesis’. The former is usually understood as the positive aspect of reproducing someone else’s behavior, whereas the latter usually implies the negative aspect of rivalry. It should also be mentioned that because the former usually is understood to refer to mimicry, Girard proposes the latter term to refer to the deeper, instinctive response that humans have to each other.

Duncan said that just as King James believed that witches wanted him dead, so he wanted them dead, and vice versa. King James recommended the persecution of witches because he believed that witches were conspiring against him. King James also did not have any clear conception of demons. He believed that witches were inspired by Satan, and there was no hierarchy (or “lowerarchy”, as C.S. Lewis calls it) of evil. There was just Satan and the witches, with no demons in between.

Janneke said that this recalled the Calvinism of her youth, which flattened the hierarchy of the church, so that there were just elders and people. She said this was correlated with literacy — as more people learned to read, they became less reliant on a clerical class.

I recalled reading a book by John Buchan (an imperialist and member of Milner’s Kindergarten) called Witch Wood. I read it a long time ago, and have not seen a copy since, but as I recall it, the good Calvinists went to church by day and practised witchcraft by night, but saw no conflict, because they were among the elect, predestined to be saved, so nothing they did could affect that. I suspect that Buchan’s understanding of the matter was about as accurate as his picture of African Independent Churches in another novel, Prester John, which was, however, probably accurate in the picture it gives of the views of such churches by British civil servants in the conquered Transvaal Colony.

[image error]

Janneke Weidema, Tony McGregor, Val Hayes, Steve Hayes, Duncan Reyburn — literary coffee klatsch, 6 July 2017

King James wrote his Daemonologie in 1597, at the height of the Great European Witchhunt. People whose minds are saturated with modernity like to refer to those witchhunts as “medieval”, but they were not, they were modern, and arose in the Early Modern period. It is interesting that in the current period, when much of Africa is in transition from premodernity to modernity, there has also been an increase in witchhunting.

Charles Williams, one of the original Inklings, wrote Witchcraft, a history of Christian responses to witchcraft, and noted how the attitude to witchcraft completely changed in the early modern period. Previously it was considered heretical for Christians to believe that witches could harm people, because it showed a lack of faith in Christ, who had conquered evil. In Early Modern Europe, however, it became heretical not to believe that witches could harm people. Earlier, people who made false accusations of witchcraft could be punished, but in Early Modern Europe failure to accuse could be interpreted as a sign of being a witch. Witchcraft came to be seen as a huge satanic conspiracy against church and state. As Charles Williams puts it:

The Salic law of Charlemagne decreed that anyone who was convicted of witch-cannibalism should be heavily fined, but also that anyone who was found guilty of bringing such an accusation falsely should be fined an amount equal to one third of the other… The secular governments of centuries earlier had been wiser; they had penalized the talk as much as the act. The new effort did not do so; it encouraged the talk against the act.

Christianity came into a world in which witchcraft was already known and feared as evil. For many pagans, the only proper penalty for witchcraft was death. Again, as Charles Williams put it:

Before Christendom began, magic, with its lower accompaniment of witchcraft, preoccupied the whole Roman Empire; we have forgotten the darkness out of which we came. It was as popular as it was perilous. It was certainly regarded by the authorities as a public danger, but, on the whole, action against it was taken only by private persons in lawsuits or by the government in suspicion of treason.

In much of premodern Africa, witches were regarded as incorrigible, and the only way of nullifying their power was to kill them. Nearly all evil, sickness, accidents and other misfortunes, were regarded as being caused by human malice — witchcraft. There were spiritual or religious specialists who could smell out who was responsible for a particular misfortune, and the English translated most of the words for these specialists as “witchdoctors” — doctors who could remedy the evils caused by witchcraft.

Christian missionaries from late modern Europe and North America could not cope with premodern notions of witchcraft, and so saw their mission as modernising Africans (they called it “civilising”) to show them that such notions were false and out of date. It was African independent church groups like the Zionists who recontextualised the Christian gospel back into premodern terms to show how it could deal with African problems rather than modern European ones.

We briefly discussed the way in which, in English usage, “witch” has come to be seen as mostly female, while the male equivalent are called “wizards”, as in the Harry Potter stories. Perhaps we can talk about that more next month. Some did a bit of Googling on cell phones, but I think the following is more helpful:

What really is a witch? One answer lies in the roots and development of words. ‘Witch’ derives from the Old English wicca (pronounced ‘witcha’ and meaning male witch) and wicce (‘female witch’, pronounced ‘witcheh’) and from the word wiccian, meaning ‘to cast a spell’. Contrary to common belief among modern witches, it is not Celtic in derivation, and it has nothing to do with the Old English witan, ‘to know’, or any other word relating to wisdom. The explanation that witchcraft means ‘craft of the wise’ is false…

‘Wizard’, unlike ‘witch’, really does derive from Middle English wis, ‘wise’. The word first appears about 1440, meaning a ‘wise man or woman’; in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it designated a high magician, and only after 1825 was it used as the equivalent of ‘witch’ (Russell 1980:12).

For others who were there, if you think I missed something important, or got something wrong, please clarify in the comments section.

Till next time…

July 4, 2017

A Review of “The Chapel of the Thorn” by Charles Williams | A Pilgrim in Narnia

A review of The Chapel of the Thorn by Brenton Dickieson

An Unpublished Poem by Charles Williams. Charles Williams wrote The Chapel of the Thorn in 1912, though it was never published. Once thought lost, this Williams’ play has finally been brought to print by Inklings scholar Sørina Higgins.

I had the opportunity of seeing this mportant and neglected Charles Williams dramatic poem move from archival space to finished book.The original text is housed at the Wade Centre in Wheaton, IL.

By a chance encounter I was working beside Higgins as she began to open up this century-old text with the hope of publishing it Head tilted forward as if in prayer, left hand hovering over a magnifying glass, Higgins worked with Williams’ neat handwriting. It was a manuscript complicated with age, his own edits, and the comments of his beta reader, Fred Page. Thus began the two-year process of transcribing, formatting, checking, editing, introducing, and producing The Chapel of the Thorn.

Anyone who has attempted Williams’ later poetry knows that there are challenges ahead. Even his supernatural pot-boilers—relatively popular in the day—can be a little obscure at times. It is true that in both the novels and the poetry, Williams’ characters are clear and the narrative arc is discernable. He can paint scenes with vividness and heighten expectation even for the tentative reader. Still, the gap between reader and writer often remains.Charles Williams writing

The Chapel of the Thorn has none of that distance. For any reader who enjoys Shakespeare or Arthurian literature, Thorn is completely accessible. Written in formal iambic pentameter with even-handed archaisms, I was immediately drawn into the story of The Thorn. The setting is a coastal village in late Roman Britain. The village sits on the historical crossroads between paganism and Christianity. The land is officially Christian, but there is a power struggle still at play between king and Church.

The villagers attend the local Christian church, and the women are typically devout. The men, however, only pretend to Christian piety while they maintain their devotion to paganism, their love of the old druidic stories, and their practice of keeping sex slaves—mistresses who satisfy the male and are an economic trade unit in the village.As the title suggests, the tension focusses around the little village chapel. It is the home of a sacred object, a thorn from the make-shift crown that attended the crucified Christ’s brow (or perhaps it is the entire crown itself).

The village priest, Joachim, is the protector of the relic and seeks enjoyment of Christ in its contemplation. The villagers see it as a thing of power, but their main interest in the chapel is that it is the resting place of their ancient hero, who will one day rise again. Attendance to religious service, then, is a façade for some and mystical encounter for others. The tender balance of past and present, paganism and Christianity—held together by a silent truce of hypocrisy and doublespeak—is threatened when a nearby Abbot, a monk of tremendous secular and personal influence, comes to the village to remove the relic to a more accessible place of pilgrimage. While Abbot Innocent pretends to public interest alone, it is a power play at a far deeper level. This unusual triangle fuels both the poetry and the plot.

There are other storylines woven into this short play, and yet I never found that the stage was too crowded. The most slippery aspect of the play is the very thing that gives it enough interest to read a second time: what is the motivation of the characters? The Chapel of the Thorn begs at questions of authenticity and hypocrisy with well-drawn characters that pull us into their own storylines.

Sørina Higgins has done a great service in bringing this text from the hallowed halls of the archives to our nearest bookstore. But she has done more than this. Added to her own critical introduction are essays by Grevol Lindop and David Llewellyn Dodds—really the two other scholars to have produced work on The Chapel of the Thorn. These three engaging thinkers tell us the history of the text, but also assess the poetry itself and link Thorn to Williams’ other works. We see in Thorn, for example, the beginning of Williams’ interests in the hallows and Arthurian legend—interests that will be central themes in Williams’ popular novels and narrative poetry.The result of Higgins’ work as editor and producer is a book that re-begins a delayed conversation, continuing a journey that was aborted long ago. In this way she extends the work of an archive, giving us all the chance that I have had: to sit with the manuscript before us, head tilted forward as if in prayer, our pencil hand hovering over a notepad as we try to discern the many layers of this almost lost Charles Williams treasure.

There’s more to the original post than just the review of The Chapel of the Thorn, so I urge you to follow the link and read the rest of it as well.

July 2, 2017

Inside Prince Caspian

Inside Prince Caspian: A Guide to Exploring the Return to Narnia by Devin Brown

Inside Prince Caspian: A Guide to Exploring the Return to Narnia by Devin Brown

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I’ve read Prince Caspian at least 5 times, and when I found this book in the Alkantrant library I wasn’t expecting much. Prince Caspian is a fairly straightforward children’s story based on a theme common to many fairy tales — an evil usurping king who suppresses the true heir to the throne, is eventually deposed and the rightful ruler is restored. How much can you say about that that isn’t said in the story itself?

[image error]But Devin Brown has quite a lot to say about it, and a lot of what he says is quite illuminating. It makes me want to read his earlier book, about The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, if I can find a copy anywhere. At the time I first read it, in September 1965, I was struck by the parallels between the White Witch’s rule in Narnia, and the Vorster regime in South Africa (though Verwoerd was Prime Minister, Vorster was Minister of Justice, and was turning South Africa into a police state). The raid of Maugrim the wolf, head of the Witch’s secret police, on the home of Tumnus the faun had many parallels with the Security Police raids of those days, and the statues in the witch’s castle represented for us the banning and detention without trial of opponents of the National Party regime.

Those themes, while not absent from Prince Caspian, do not appear quite so strongly. What had always struck me most strongly about Prince Caspian was Lewis’s attitude towards pagan myths and deities. In Prince Caspian they are not the enemy, but are part of the army of liberation.

What Devin Brown brings out most strongly, however, is Lewis’s anti-racism, and the parallels between the policies of the usurper Miraz and the apartheid ideology. Miraz’s policy is based on Telmarine supremacy, with all others being banished to the woods (read “homelands”).

In another blog post, Mere Ideology: the Politicisation of C.S. Lewis, I noted attempts by American libertarians to coopt C.S. Lewis to support their political and economic ideology, based on that of Ayn Rand. But Devin Brown (2008:215) shows that Rand’s ideal of selfishness is the Philosophy of Hell:

While Caspian expresses regret for allowing Peter to fight on their behalf, exclaiming “Oh why did we let it happen at all?” Glozelle and Sopespian have purposely manipulated Miraz into accepting the challenge. The two lords, Miraz, and by extension the rest of the Telmarine army exemplify what Screwtape calls “the philosophy of Hell”. Screwtape explains that, according to this philosophy, “my good is my good and your good is yours. What one gains another loses. ‘To be’ is to be in competition.'”

That is capitalism (Rand’s “unknown ideal”) in a nutshell. Socialism, on the other hand, is based on the fundamental notion that cooperation is a better basis for economic life than competition.

Brown also draws parallels between the anti-colonialism of Prince Caspian and that of the Oyarsa of Malacandra’s comments to Weston in Out of the Silent Planet. The Telmarines are colonialists. They entered Narnia from outside, conquered it, and ruled it for their own benefit. The natives (Old Narnians) were marginalised and had no rights under Telmarine rule. After the War of Deliverance Aslan gives the Telmarines a choice: they can renounce their privilege and live with the same rights as other Narnians (echoes of the Freedom Charter: “South Africa belongs to all who live in it”) or they can leave and go back where they came from.

Saying this may make it sound as though Prince Caspian is allegory, but it is not. As Carpenter (1978:30) wrote:

Lewis wrote to Tolkien on 7 December 1929, after reading Tolkien’s poem on Beren and Luthien, “The two things that come out clearly are the sense of reality in the background and the mythical value: the essence of a myth being that it should have no taint of allegory to the maker and yet should suggest incipient allegories to the reader.”

So Prince Caspian suggests incipient allegories to me that would not have occurred to C.S. Lewis or Devin Brown, and it was written before the Freedom Charter had been drawn up. It may have suggested other incipient allegories to Devin Brown, living in the USA. One that occurs to me is the parallel between Narnian schools under Miraz’s rule and Sheldon Jackson’s educational policies in Alaska.

But what Brown brings out most clearly is that the oppressive rule of the Telmarine supremacists brings uniformity but not unity, and that true community and freedom is found in the diversity and equality of the Old Narnians, whom Caspian joins, thereby becoming a race traitor in the eyes of the Telmarine supremacists. The themes that Brown brings out most strongly are Lewis’s emphasis on diversity and environmentalism before they became popular causes twenty years after he wrote.

Brown also notes many other literary allusions, to Shakespeare, Tolkien, and other authors.

There are a few minor flaws. At one point Brown notes a typo in his edition of Prince Caspian, where Trumpkin refers to something that happened three days earlier as happening “this morning”. Two pages further on he has typos of his own, where he refers to Lewis’s That Hideous Strength, and has Lewis writing about “microbes” when what Lewis actually wrote about was macrobes.

I would be interested in knowing whether Brown has written more about the later Narnia books. I re-read The voyage of the Dawn Treader after seeing the film, and blogged about it here. I’d be interested in seeing what he had to say about that.

One reason for reading this book is that I’m thinking of writing a sequel to my own children’s book Of Wheels and Witches, and I thought it would help me to get in the mood. It has done that, perhaps much more effectively than lots of the “how to” books and blog posts about writing for children, because it analyses what makes a successful children’s novel.

Shameless self-promotion: Of Wheels and Witches is available free during July 2017.

June 28, 2017

The Enid Blyton story

The Enid Blyton Story by Bob Mullan

The Enid Blyton Story by Bob Mullan

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Why read a book about a children’s author whose only adult novel was rejected by publishers?

Others who have written children’s books have also written for adults, or their children’s books also appeal to adults. But Enid Blyton’s books only really appeal to children. Adults might read them as part of a research project to analyse their appeal, or to criticise their shortcomings. It is very rare for adults to read them purely for enjoyment.

I read some of Enid Blyton’s books as a child, and enjoyed them. I suppose, as this book points out, that they gave me a taste for reading. But as an adult one quickly becomes aware of their limitations.

book[The Enid Blyton Story[ is in part a biography of Enid Blyton, but it is rather annoying in that rerspect, as [author:Bob Mullan] tries to psychoanalyse her as he goes along, speculating about motives, conscious and unconscious, for her behaviour at various points.

It also gives an account of her works, with copious illustrations of the covers and internal illustrations of her books. There is little comment on these, but that might have been more interesting than the attempts to analyse Enid Blyton’s guilt feelings about members of her family. The styles of clothing worn by the children in the illustrations changes over the years, but there are no comments on this.

There are plenty of criticisms of her works as well, which are included in the book, but, as Bob Mullan points out, Enid Blyton did not write for critics, she wrote for children.

I was also quite surprised by the wide range of books she wrote. I never read any of her school stories, and was hardly aware of them. I’d seen some of the titles, and no doubt had seen Enid Blyton‘s name on the cover of some of them in bookshops, but it had never really sunk in that she was the author. I never read the Noddy books either, and the “Famous Five” didn’t appeal to me.

The first Enid Blyton book I read was The Secret of Kilimooin, which I borrowed from an older friend, and the first one I owned was The Mountain of Adventure. I went on to read several other books in those series, but none of them seemed as good as the first two. Perhaps, as the critics say, it is because Enid Blyton is limited in her range of plots. She does write to a formula, and in reviewing The Shack the most apposite description I could think of for its beginning was that it was Enid Blytonish.

So what makes a book “Enid Blytonish”? Perhaps it’s the kind of irrelevant detail of preparations for going on holiday, and the descriptions of food, which neither move the plot forward nor set the scene. Perhaps nowadays it would be called food porn. So if the plots are a bit thin and the dialogue is stilted, what is it about Enid Blyton’s books that appeals to children?

And I think Mullan concludes that the main appeal is story telling. Children aren’t great literary critics. It doesn’t matter so much how well or how badly the story is told, as long as it is told. It is adults who get hung up on style and vocabulary. I doubt whether any child, ever, spoke like Enid Blyton’s characters, but children tend to overlook that, unless, perhaps, very dated or outlandish slang is used.

And I think one can even learn something from Enid Blyton’s books. In The Mountain of Adventure she undoubtedly caricatures Welsh people, but from it I learned that there were Welsh people, and that there was a force of gravity that kept us on the earth. In The Secret of Kilimooin I learned that there were people of very different cultures in the world, and some of the difficulties of communication between them. So even Enid Blyton can widen children’s horizons.

June 15, 2017

The death of liberalism in the West

The news item was perhaps overlooked when the headlines were dominated by the Grenfell Tower fire and the shooting of a politician in the USA. But The Guardian told the story Tim Farron quits as Lib Dem leader | Politics | The Guardian:

Farron says ‘remaining faithful to Christ’ was incompatible with being party leader after repeated questions over his faith

He made a statement, which is worth reading in full, which shows just how anti-Christian the British media have become.

Farron resigns as Lib Dem leader:

From the very first day of my leadership, I have faced questions about my Christian faith. I’ve tried to answer with grace and patience. Sometimes my answers could have been wiser.

At the start of this election, I found myself under scrutiny again – asked about matters to do with my faith. I felt guilty that this focus was distracting attention from our campaign, obscuring our message.

Journalists have every right to ask what they see fit. The consequences of the focus on my faith is that I have found myself torn between living as a faithful Christian and serving as a political leader.

There have been similar things in the USA, where Christian groups have been cold-shouldered from anti-war marches because they are anti-abortion, and from anti-abortion marches because they are anti-war.

Tim Farron goes on to say:

I’m a liberal to my finger tips, and that liberalism means that I am passionate about defending the rights and liberties of people who believe different things to me.

There are Christians in politics who take the view that they should impose the tenets of faith on society, but I have not taken that approach because I disagree with it – it’s not liberal and it is counterproductive when it comes to advancing the gospel.

Even so, I seem to be the subject of suspicion because of what I believe and who my faith is in.

In which case we are kidding ourselves if we think we yet live in a tolerant, liberal society.

So it seems that there is no place for liberals in the Liberal-Democratic Party in the UK.

[image error]

Tim Farron

The Wikipedia article on Tim Farron notes “Among political observers, Farron is widely seen as being of left-leaning political position. In a September 2016 interview, he identified the Liberal Democrats under his leadership as being centre-left.”

It seems that what the journalists questioned him on was not his political policies, but his religious beliefs. The Guardian article cited above noted that such things might be asked of someone of any religion, but I wonder if London’s Muslim mayor faced similar questions.

The anti-Christian attitude of the British media seems also to be reflected in recent statements by US politician Bernie Sanders. I think that is rather sad, because I thought that Bernie Sanders would have made a better US president than either Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton. Is It Hateful To Believe In Hell? Bernie Sanders’ Questions Prompt Backlash : The Two-Way : NPR:

A low-profile confirmation hearing on Capitol Hill this week raised eyebrows when the questioning turned to theology — specifically, damnation.

Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont pressed Russell Vought, nominated by President Trump to be deputy director of the Office of Management and Budget, about his beliefs.

This is somewhat different from the Tim Farron case, because Russell Vought is no liberal, but if this report is to be believed, Bernie Sanders is no liberal either.

[image error]

Bernie Sanders

It is difficult to know how accurate media reports are, but according to reports I’ve read, Vought supported his institution, Wheaton College, in its decision to sack another teacher for supporting Muslim civil rights. If Sanders had questioned Vought on that action, I’d have no quibble with it, but he didn’t, he chose to attack Vought’s theology and to misinterpret it, and it is doing that that he is similar to those in the UK who attacked Tim Farron for his theology.[1]

All this shows up the biggest flaw in Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations thesis. Huntington maintained that civilisations were based on religion, and that the religion of the West was Roman Catholic Christianity, but these events show that it is not: the established religion of the West is Secularism. I’ve said more about this in other articles, where I explain why I believe that Secularism is a religion, and why I think it has become established in the West: Christianophobia and Secularism in Europe, and Militant atheists, Christianists, and the idolatry of the West.

As a missiologist (student of Christian mission as a phenomenon) I’m well aware of the history of Western Christian missions to other parts of the world in the 19th century, which very often involved cultural imperialism, cultural clashes, and destruction of cultures. One result of missiology (mission studies) is that many Christians have become aware of the errors of the past, and are much more sensitive about such things. Not so the 21st Century missionaries of Western Secularism, who go barging into other people’s cultures with the same crass insensitivity, and alienate people as a result.

In the history of England (and later Britain) conformity to the Established Church was enforced by laws which only really began to be relaxed in the 19th century. And now they are being reintroduced to enforce conformity to the new Established Church of Secularism.

Here’s a comment on Tim Farron’s stepping down from a Muslim liberal leader:

People of faith might think that their values can’t coincide with liberal values. But the truth is that liberalism is the most likely to uphold their right to practise any faith. As someone who defines themselves as both Muslim and liberal, I believe that our freedoms extend to anything as long as they don’t violate the freedoms of others.

As far as I’m concerned, for example, you can wear whatever you want: face veil, miniskirt, burkini, bikini. It really is your own choice. In fact, this shows in the Lib Dem manifesto, which was the only one of the main three to mention upholding the freedom to wear cultural and religious dress.

I’m a liberal, and once I was a Liberal, a card-carrying member of the Liberal Party of South Africa, which was forced by the South African government to disband in 1968 because it was non-racial. It was also non-denominational. It espoused a political programme and policies which people of different religious, cultural and linguistic backgrounds could support and work for together, regardless of their reasons for supporting those policies.

My reasons for supporting those policies were theological. I was a liberal because I was a Christian, not in addition to being a Christian or in spite of being a Christian, for reasons I have explained here and here. And that is why the story of Tim Farron saddens me. That he felt he had to step down indicates that the Lib-Dems in the UK are both anti-Christian and anti-Liberal.