Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 27

February 3, 2018

The crème de la crème of South African religion and spirituality blogs

I entered this blog in the 2017 SA Blog Awards, and the winners have now been announced.

Thanks to everyone who voted for Khanya blog.

I entered this blog in two categories: Religion and Spirituality and Arts and Crafts (that seemed to be the closest one could get to books & literature in the awards categories).

Here are the winners, so you can find the best in SA blogging.

Religion and Spirituality best blogs 2017

Winner: Ruth Abercrombie

Runner-up: My Spreadsheet Brain

Runner-up: Adele Green

So there you have it — the crème de la crème of South African religion and spirituality blogs in 2017.

January 24, 2018

1968 in retrospect

1968 in Retrospect: History, Theory, Alterity by Gurminder K. Bhambra

1968 in Retrospect: History, Theory, Alterity by Gurminder K. Bhambra

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I saw this book going cheap on a book sale and I bought it because 1968 was quite a significant year in my life, and the title 1968 in retrospect interested me. The sub-title, however puzzled me. I had to look up “alterity” in a dictionary, and I’m still not sure what it means.

It’s a collection of essays by sociologists on the significance of 1968. What made the year significant for them was clearly the whole Student Power thing that erupted in that year, though they didn’t actually say so explicitly. One had to infer that from the contents of the essays, many of which were self-consciously not about the events of Paris in May 1968, as they said focusing on that meant that people missed a lot of other significant things, but in the end it became clear that it was the events in Paris that gave significance to the other things.

In the introduction the editors acknowledge that they weren’t born in 1968, though they asked for advice from a couple of people who claimed to have been there, and therefore their memories must be suspect. And to me that makes their whole enterprise suspect. As a historian I know that people who “were there” when significant events took place can never see the whole picture, and in the history of those events there will be gaps that only become apparent much later.

I know this from personal experience. I “was there” in the 1960s. I saw what I saw, and heard what I heard, but I didn’t see or here everything, not even all the bits of it that concerned me directly. Only 40 years later, when I read the reports that the security police sent to the Minister of Justice did I discover that I had been to places I had no recollection of being at. Such sources only become available to later historians, and enable historians to piece together a fuller picture of the past. So yes, “being there” is not enough. But does that make those who weren’t there less suspect than those who were? I’m not so sure about that.

The authors of these essays are not historians but sociologists, and there is little evidence that they have done much historical research on the subject. So that was a disappointment, to me, at least. What the book perhaps does show is the significance of 1968 for the history of sociology as a discipline. I will say some more about the significance of sociology in 1968 from the “I was there” perspective, but not in the Good Reads review. I’ll save it for an expanded blog post with more personal reminiscences, which will be extraneous to the book review.

I won’t deal with everything in the book, but the main thing that struck me was that many of the authors wrote about the “long decade”. 1968, they said, encapsulated the Sixties, and the Sixties really lasted from 1956 to 1976. Now if one is looking for the characteristics of that long decade, there are all sorts of cultural currents that they do not mention at all — the Beat Generation of the late 1950s and early 1960s, and their successors, the hippies and the Summer of Love in 1967, though that was before 1968. But it was students who experienced the “Summer of Love” who were also involved in the events of 1968, so what influence did one have on the other. None of the authors say. There were theological currents, such as the “God is dead” thing, and the Jesus freaks. The “Prague spring” of 1968 is mentioned in passing but not really analysed.

The editors said they were trying to get away from a Western perspective, and were more interested in non-Western perspectives, and feminism and gay liberation. So there is a chapter on politics and student resistance in Africa since 1968, whose author, Leo Zelig, writes:

This chapter looks explicitly at the nature of the student revolts in Africa in the late 1960s and 1970s. The chapter seeks to pull our attention away from Europe and North America, the privileged sites for discussing 1968, to focus on other voices that began to craft a new politics in that year.

But he goes on to deal with African students of the period as the privileged within their societies anyway.

And if the aim was to shift the focus away from the privileged, why was there no mention of student revolts that started in Soweto in 1976 and spread throughout South Africa? If the Sixties were a long decade, then that surely was a significant culmination of the student power movement of 1968, but it is hardly mentioned in the book. For that I recommend The Rocky Rioter Teargas Show, which gets the spirit of ’76 better than this book gets the spirit of ’68.

To justify the “history” part of the title the very least I would have expected would be a chronology of the events of 1968 that the authors and editors saw as most significant, and possibly some of the events in the preceding and following years that constituted the “long decade”. As one chapter in the book reminded us, 1968 was the year that Enid Blyton died. But the conclusion that I came to after reading this book was that sociologists can’t write history, and a real history of 1968 has yet to be written.

Sociology in the Sixties: a personal encounter

I thought I would add a personal retrospect (not on Good Reads, since it’s no longer a review of the book), and I challenge any of my blogging friends who were alive in 1968 to do the same. It may provide some raw material for real historians to work on. But since the approach of this book is sociological, I should first describe my encounter with sociology in the 1960s.

In 1960 I registered for Sociology I at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits). As an introduction to the discipline it had grave shortcomings (I see now, in retrospect). The prescribed textbook was Human Society by Kingsley Davis (which is so out-of-date that I couldn’t find it on Good Reads for a reference), and the impression was given that Davis’s approach was sociology. There was no mention of other schools, not the slightest hint that there even were other schools. We had lectures from Prof G.K. Engelbrecht on various forms of social deviancy, like juvenile delinquency, and I had to write an essay on the causes of adult crime.

Halfway through the year I went to a student conference at Modderpoort in the Free State. It was the first conference of the Anglican Students Federation, which was formed at the conference, and there were a number of interesting speakers on a variety of topics that were far more stimulating than most of the lectures we had at university. Among the speakers was Brother Roger of the Community of the Resurrection whose paper Pilgrims of the Absolute made me aware that my Christian values ran counter to those promulgated by Kingsley Davis and the Wits Sociology Department. For Davis Society was the Absolute. And so I became critical. I developed my own critical theory about sociology, that it was idolatry and incompatible with the Christian faith. Christians were therefore to be counter-cultural and eccentric — having a different centre from that of Kingsley Davis and the sociologists.

Jump to 1965, when at another church conference, in Johannesburg this time, on the topic of “The Church and Youth”. Prof G.K. Engelbrecht of the Wits Sociology Department was invited to speak. He said that that task of the church was to help youth to adjust to society. He spoke of the problems of maladjusted individuals, and how the church could help them. I was older then, and at a different university, so I felt more free to question Prof Engelbrecht than when he had been lecturing 400 first-year students in 1960. So at question time I asked him, What if society is wrong? What if you have a bad society? Was the role of the church still to help youth to adjust to it? What about the Old Testament prophets — weren’t they maladjusted individuals? No, said Professor Engelbrecht, youth must adjust. But I persisted, What about a society like Nazi Germany, must youth adjust even to that? “Youth must adjust!,” he said, even more emphatically.

That confirmed all my prejudices — that sociology as a discipline was simply a con to sucker people into accepting the status quo, and that remained my view until 1968.

1968: A personal retrospect

At the beginning of 1968 I was at Nijmegen in the Netherlands, staying with some Augustinian friars. The beginning of the year was marked by fireworks and the hooters of the barges going up and down the Rhine. A visiting English student friend, Alastair Wyse, and I walked through the snow to the German border and took a bus to Kleve, to have a beer. A friendly German citizen bought us many more, and would have carried on doing so until we were unable to find our way back to Nijmegen.

I was a student at St Chad’s College, part of the University of Durham in England, studying for a postgraduate Diploma in Theology. I was spending the Christmas vacation with the Augustinians in Breda and Nijmegen to get a feel for the theological ferment going on in the Dutch Roman Catholic Church. They were modernising, and the Augustianians had abandoned their religious habits for business suits. Alastair Wyse told me that just before leaving England he had seen a DJ on TV wearing a monastic habit, so pop culture was overtaking the Dutch Augustinians and leaving them behind. I had a couple of T-shirts with me, with the slogans “Jesus Saves” and “God is Love”. They were sold by the satirical magazine Private Eye and John Lennon had appeared on the front page of the Daily Mirror wearing one. I took a photo of the OSA brothers wearing them, with their business suits. Perhaps it epitomised the new monasticism, or the conflict in the Western Christian search for “relevance”. Relevance to whom? Pop culture or the suits? You can see more on this, with more pictures, here.

The Augustinians had produced some rather good liturgical innovations, I thought, and the reasoning behind it was that the liturgical life of a community was the expression of the life of the community as a whole. They had no desire to impose this on anyone else. I asked them if there would ever be a non-Italian Pope of Rome, and they said that as he is the Bishop of Rome, an Italian city, he ought to be Italian; he just mustn’t stick his nose over the Alps and try to tell us what to do.

I returned to St Chad’s College in mid-January to find just the opposite. Most of the students were studying theology, and many were preparing to be ordained in the Anglican Church, so the chapel was fairly central to what went on. The previous term the college had used a new experimental liturgical text of the Church of England, called Series II. At the end of the term the staff had asked students to submit written comments on it. Not everyone had submitted comments, but those who had had been entirely negative. When we returned at least some of us expected that there would be a college meeting, where this would be discussed. But there was no meeting. The chapel services had reverted to a kind of ornate and fussy 1930s Anglo-Catholicism, imposed by the college teaching staff.

When we queried this we were told it was our own fault; we had not made written submissions. Four of us, in particular, found this unsatisfactory. I had been among the Dutch Augustinians, and seen what they did. Two others, Graham Mitchell and Hugh Pawsey, had been at a conference organised by the Student Christian Movement (SCM) at which one of the speakers had been a Swiss Reformed Chilean Pentecostal called Walter Hollenweger, and came back talking a lot about the Holy Spirit. The fourth was Alan Cox, who in the previous summer vacation had met a Zen rabbi in the USA called Murray Goldman, who he said had converted him to Christianity (and later converted to Christianity himself, I was told).

Alan Cox went to see the principal, John Fenton, and had a long chat with him about the weird liturgical regression. The principal convinced him that it didn’t matter what we did liturgically. It didn’t matter whether we had the Series II of last term, or the Italianate baroque of this term. We decided to take the principal at his word. It was the custom, on the eves of major feasts, for students to attend Evensong wearing cassock and surplice and, if graduates, academic hoods. We turned up in current hippie gear — orange trousers, flowery shirts and the like, because, you see, it didn’t matter. But it turned out that it did matter, not least to the principal, who was furious.

It was also a custom for some students to preach and lead services in local churches, and Alan Cox and I went out to the Durham mining village of Bishop Middleton with Herbert Langford, the vice-principal, known as “The Brang”. He was a German Jew who had fled Hitler’s Germany and arrived in England as a penniless refugee in 1939, and had then become a Christian. I rather liked and admired him.

On the way back he asked “Vy veren’t you vearing vedding garments the other night?” We explained that we thought that the “wedding garments” were becoming a new form of circumcision. He harrumphed, and disagreed.

The next major feast was the Conversion of St Paul on 25 January. So on the 24th, exactly 50 years ago as I write this, the order came down from on high: “Vedding garments, by order”.

I had just received a bunch of press cuttings from my mother back in South Africa, and one of them described how an Anglican priest in Cape Town, Gray Featherstone, had nailed 95 theses to the door of Cape Town Cathedral about the church’s lukewarm opposition to apartheid. Inspired by his example, we compiled a document about the college as a Christian community. We could not come up with 95, only 33 propositions, so we headed it 33 Revolutions per Minute (those over 40 may understand). When the time came for Evensong, we left our cassocks, surplices and hoods neatly folded up in our places in chapel while we were in the college office, running off copies of our 33 theses on the stencil duplicator (again, those over 40 may understand).

We put one on everyone’s table in the dining hall. At dinner, we all went to sit at high table to see how the college staff reacted, and, we hoped, to discuss it with them. Alan sat next to Brang. Graham and I sat on either side of one of the tutors, Eric Franklin, facing the Principal, and Hugh Pawsey sat next to the other tutor, Hugh Bates, who, seeing the theses lying on his place, tore it up while the Principal was saying grace.

Afterwards Hugh (Pawsey) asked him why he had reacted like that, and he said if anyone wants to give him something they can put it in his pigeon hole. The Principal made polite conversation, as did Eric Franklin, and Brang didn’t seem to say anything to Alan at all. After dinner we put another copy of the theses in Hugh Bates’s pigeon hole, and then at coffee got discussing it with the Brang and Eric Franklin, but didn’t manage to get much further, Brang didn’t understand at all, and Eric Franklin seemed to think that the best approach was moral paralysis.

The main argument in our theses was not in favour or or against any particular liturgical practices, but rather that the college must meet to talk about it, staff and students together, rather than the staff soliciting individual written submissions from students, and then making arbitrary decisions based on those.

That was part of our contribution to the student power movement, three months before the events in Paris. We had not consulted Daniel Cohn-Bendit — we had not even heard of him then. Perhaps student power in its varied manifestations was something in the air, and that was at least part of our experience of the spirit of ’68.

The following day we had a meeting with the principal, who largely agreed with us (so he said), but said that there were two communities in the college, the graduates and undergraduates, and that there were some very frightened people among the undergraduates, and he thought liturgical stability was needed to keep them from flipping entirely. We said that there were far more diverse communities than the college, and we thought that the way of holding them together in their diversity would be to meet and discuss things.

At the end of January there was a meeting of the university African Society, chaired by Gavin Williams, a South African teaching in what passed for the Sociology Department in Durham (Department of Social Theory and Institutions). The speaker was a Mr Hodgkins from Oxford, who spoke about Frans Fanon. Some of what he said is so true of South Africa 50 years later that it is almost uncanny.

According to Fanon many postcolonial societies are controlled by the national bourgeoisie — the university and merchant class and civil service. They are unlike the European bourgeoisie in that they are not interested in owning the means of production, but in keeping a finger in the racket. They have an aptitude for trade and small business, and are imitative of the West. They have no ideas and cut themselves off from the people. They promote “Africanisation” to secure jobs for themselves. They are suspicious of foreigners, they choose the easiest means of staying in power, that of the single party, which represents and is the instrument of the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. There is a divorce between the country and the towns, and the cult of the mystique of the party leader. In this decay the army becomes the arbitrator in any disputes. If there was to be any real revolution, it must come from the peasants, and not the urban bourgeoisie.

We adjourned to a pub afterwards to continue the discussion. I had met Gavin Williams at the wedding of a friend, Stephen Gawe, the previous year, and though him met the head of the department, John Rex, also a South African. Over the next few months I learned more about sociology from chatting to Gavin Williams and John Rex in pubs than I did in an entire year of Sociology lectures at Wits. I learned that Kingsley Davis represented only one school of sociology, the stucturalist-functionalist schiool of Talcott Parsons, and that there were several other schools, with a variety of views.

In the Easter vacation Hugh Pawsey and I attended a seminar on “Orthodox theology and worship for non-Orthodox theological students”. It was held at the World Council of Churches study centre at Bossey in Switzerland. As an impecunious student I took the cheapest flight I could get, from Gatwick to Basel. But the plane broke down in Basel, we we had to crowd into another plane belonging to the same company, which was going to Zurich. It was a twin-engined Aero Commander with canvas bucket seats, heavily loaded. As we approached Switzerland we ran into a thunderstorm, going through heavy clouds with pouring rain and lightning flashes all around and the plane bucking like an under-exercised horse. I knew there were Alps up ahead and hoped the pilots could see them because I certainly couldn’t.

On arriving in Zurich I took a train to Fribourg and stayed with another South African student, Barbara Newmarch, who was studying there. She introduced me to the class system of Switzerland, or at least that part of it. The working-class kids in the street spoke German, the upper-class kids spoke French. The following day I got the train to Celigny, and the Orthodox seminar began.

The seminar was arranged by Professor Nikos Nissiotis of Athens University, He gave lectures, as did Fr Cyril Argentis, Fr Boris Bobrinskoy, Fr Alexis van der Mensbrugge and Fr Jean Tchekan. The lectures were interesting, but the “Aha” moment came when discussing it with some Lutherans seminarians from East Germany (DDR). About 30 of them had come, and formed a large block. As we were standing outside the chapel, which had ikons of Christ and the Theotokos, one of them was saying “But what about the Word? There is nothing about the Word!” And I pointed to the ikon of Christ and said, “There’s the Word.” The Lutheran response had told me as much about Orthodoxy as the lectures themselves.

We had a couple of free days. On one of them Hugh Pawsey and I took a boat across the lake to Yvoire on the French side, a village that retained much of its medieval character. On another day we took the train to Geneva, and went to the headquarters of the World Council of Churches, where we met Walter Hollenweger, who had spoken at the SCM conference Hugh had been to in January. We told him about what had been happening at St Chad’s, and he suggested speaking to a journalist, as they were the ones who were best at understanding and producing liturgy these days. We decided not to; the basic problem was a lack of a sense of community in the college, and we thought bringing in an outsider would be counterproductive.

After 10 days of lectures we boarded a bus to Paris, where the seminar concluded with Holy Week and Pascha at St Sergius. There we had to stay in hotels and eat in restaurants, but Hugh Pawsey and I fasted with the students of the seminary who lived in primitive conditions in the crypt of the church, because we had no money for restaurants. We spent our last francs on the cheapest loves of bread we could find, which we ate sitting in a park.

The thing that made the deepest impression on me was the Easter kiss. The church was full, and it took 45 minutes for everyone in the church to kiss everyone else. A few years later Western churches introduced the “kiss of peace”, but in 1968 I had never seen anything like it, nor heard anything like the Catechetical Address of St John Chrysostom that followed, which seemed to summarise the entire gospel in one page.

[image error]

Holy Week at St Sergius in Paris, April 1968. The priest is Fr Alexander Kniazeff.

As we left Paris on Easter Monday 22 April 1968 the student power demonstrations were just beginning. Perhaps we should have stayed and witnessed more of the historic events, but we had no money at all, just our return boat and train tickets, so we left, and called at Hugh Pawsey’s parents place in Kent to cadge some money to continue our journey, and get something to eat.

Back in Durham about thirty students were having a sit-in in the university administration building. Newspapers were quoting police spokesmen as saying that they were taken by surprise, as they had not expected any “trouble” in Durham, which was the most middle-class university in the UK.

The Dean of the Theology faculty, Prof H.E.W. Tuirner, called a meeting of all the staff and students of the faculty, and asked for ideas on how to improve communication. One student shouted, “You’re just scared that we’re going to pull up the paving stones in Sadler Street and toss them through your window.” No, no, said the Dean, it’s nothing like that, we just want better communication. But undoubtedly the desire was sparked by what was happening in Paris.

Meanwhile, back in South Africa, the National Party government passed the Improper Interference Act, which made it illegal for people of different races to take joint political action. As a result the Liberal Party, of which I had been a member, was forced to disband.

The term passed, the exams came, and then I went to London to see the Anglican Bishop of Natal, who had sent me to St Chad’s. He was in London for the Lambeth Conference of Anglican bishops. St Chad’s College had a September term for graduates, and he asked me if I wanted to stick around for it. If I preferred, he could arrange for me to spend a term at a South African theological college rather than hang around waiting for September. That sounded good to me, so I said yes, I’d rather go home. He asked if I would like to stop off anywhere on the way, to see something different while I was abroad. I said yes, I’d like to see Tanzania. He said that would be stupid, and suggested Greece instead, but I didn’t fancy the colonels who were in charge there, so I went more or less straight home.

But while in London I met up with Alastair Wyse, who had been with me in Nijmegen at the beginning of the year. He had been at St Chad’s the previous year, but then had gone to the College of the Resurrection in Mirfield. We spent a pleasant day in Hyde Park, making paper flowers and giving them to passers-by as a token of peace and love. A couple of months later he was arrested for planting a bomb in Westminster Abbey, and was sentenced to three months in prison. He wrote to me while he was in prison, but I lost touch with him after he came out.

I returned to South Africa, back among friends and family. The most notable change was that the safari suit, which was just beginning to make its appearance when I left in 1966, was now the height of white male South African fashion, and would not be complete without a packet of Gunston cigarettes in the top jacket pocket and a comb in one’s sock.

A fortnight after I arrived home a couple of men from the Security Police visited me at my mother’s Johannesburg flat and confiscated my passport. Then I was summoned to John Vorster Square, their new headquarters, to see a Lieutenant Jordaan. I had left South Africa for the UK in January 1966 after failing to keep an appointment with Detective Sergeant van den Heever, who wanted to give me a banning order. On my return, these things picked up again where they had left off.

On the 11th floor he said. I arrived at the entrance lobby of John Virster Square, and looked at the lift, but it only went to the 9th floor. Someone asked me what I wanted, and then directed me down a small passage. There was a tiny lift at the end of it, but only one button, for the 10th floor. Up it went. It stopped at the 10th floor, where a man asked what I wanted. I said I’d come to see Lieutenant Jordaan. He phoned to check, then sent me back to the lift, and he sent me up to the 11th floor. The lift was controlled only from the outside. The only other way out, it seemed, was defenestration. The lieutenant asked me the usual questions they asked of people for whom a banning order was required — where do you live, how many entrances, what kind of building, who else lives there. Then he said I could go. The banning order only came three years later, so that is not part of 1968.

I found that the Christian churches in South Africa were in a bit of a ferment too. They had produced a theological critique of apartheid, called A Message to the People of South Africa. Christian groups had previously made practical criticisms of apartheid, saying that it was unjust, that it implementation caused unnecessary suffering and things like that. This was different, in that it attacked the ideological foundations of apartheid, saying that it was not merely a heresy, but a pseudogospel. The “Message” was published in various languages, and I went with a Roman Catholic Franciscan priest, Cosmas Desmond, distributing the Zulu version in rural Natal. We took it to several former members of the Liberal Party.

[image error]

Enock Mnguni, former chairman of the Stepmore branch of the Liberal Party, with copies of the Message to the People of South Africa for distribution

I went to spend a term at St Paul’s College in Grahamstown. As I had already completed my diploma studies in Durham, I had no exams to prepare for and could read and study what I liked. I found a book on Orthodoxy in the college library, The World As Sacrament by Fr Alexander Schmemann, later published in an expanded version as For the life of the world. It rounded off what I had learned at the seminar at Bossey, and made more sense to me than most of the other theology I had read.

I was also faced with the prospect of bring ordained as an Anglican deacon at the end of the year, and realised that I didn’t know much about that. At the ordination service the bishop would ask, Do you think you are truly called to this office and ministration and I would be expected to say “I think so”, but probably most of the people who said that had not thought about it at all until that moment. It had certainly not been mentioned during my two years at St Chad’s College, and I’d not heard it mentioned at St Paul’s either. I scoured the college library for books about the office and ministrations of Anglican deacons, but there was very little. There seemed to be a rather large lacuna in Anglican theological education.

I left St Paul’s and Grahamstown on 30th November 1968, in the little branch line train that chugged over the hills to Alicedale, where we waited for the main-line train from Port Elizabeth that would take us to Johannesburg. I was very conscious that this was the end of my being a full-time student, and that I would never be a full-time student again.

[image error]

Grahamstown station, the line to Alicedale. November 1968

So in December I was ordained as an Anglican deacon in Pietermaritzburg on one of the hottest days of the year, and was sent to work at the Missions to Seamen in Durban, and that was where I ended 1968.

[image error]

Ordination in the Anglican Diocese of Natal, 22 December 1968, with Bishop Vernon Inman, at St Saviour’s Cathdral, Pietermaritzburg (now demolished)

Retrospect

So that was my 1968, an outline of it, anyway. There is probably much more that could be said, but that would requre a book and not a blog post, which is already too long. I had a small and rather peripheral encounter with the student power movement, for which 1968 is most famous. I had a not quite so peripheral encounter with Orthodox Christianity, which in the long term proved more significant for me personally. I’ve not mentioned the high-profile assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy in the USA, the Vietnam War, which was never far from our thoughts, and several other things.

So if you were around then, what was your 1968 like?

January 9, 2018

J.M. Coetzee on white writing

White Writing: On The Culture Of Letters In South Africa by J.M. Coetzee

White Writing: On The Culture Of Letters In South Africa by J.M. Coetzee

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

A collection of essays on South African writing by white people. The essays are arranged roughly in chronological order by what they describe, though they were written at different times, and there is no thread of argument that links them together.

We discussed some aspects of the book at our literary coffee klatsch last week White writing, dark materials | Notes from underground, so I won’t repeat that here.

The first essay. on idleness in South Africa, deals with the first European (ie Dutch) writers who described the local people when writing for people back in the Netherlands. Their overwhelming impression was of idleness, which offended their Calvinist work ethic.

There are three essays on the literary genre Coetzee calls the “farm novel” or plaasroman. He deals with the farm novels of C.M. van den Heever in some detail. These were mostly written in the period between the World Wars, and dealt with the urbanising of Afrikaners, Most of them have a kind of nostalgia for a vanished or vanishing rural way of life, where the city and urban life is seen as evil. They promoted an ideology of landownership. In this respect they dealt mainly with the farm owners of the family farm, and paid less attention to the bywoners (sojourners, sharecrioppers). or the labourers. One thing that struck me about this (though Coetzee does not say so explicitly) is the similarity of this ideology to African ancestor veneration. It is wriong to sell the family farm because the ancestors are buried there and so on. The villains are the money lenders who get the farmers into debt, and then try to take over the farms. Some are Jews, some are deracinated Afrikaners, but all have the taint of the city and its values.

Another essay deals with the rendering of foreign speech into English or Afrrikaans. Pauline Smith, who wrote farm novels in English, did this by rendering the dialogue of Afrikaans-speaking people with Afrikaans syntax, moving the verb closer to the end of the sentence. This was more common in 17th-century English, so it gives the impression of being slightly old-fashioned. Coetzee thinks that Smith got this speech pattern from the Authorised Version of the English Bible. For example, “Every bit of news that came to her of Klaartje and Aalst Vlokman Jacoba treasured.”

Alan Paton does something similar in Cry, the beloved country when rendering the Zulu dialogue of a country priest into English. The priest has come to the city to search for his lost son, and here too the theme is of rural people going astray in the city. So Paton devises the dialogue to represent the innocence,/naivety of the country priest in the city.

The chapter I found most interesting was on Sarah Gertrude Millin. Though I had read a book she had written, a memoir Measure of my days, I did not think of her as an author, but rather as the wife of a judge. I read it when I was still at school, where I had been forced to drop History as a subject in favour of Latin, so for several years Millin’s book was the main source of my knowledge of 20th-century South African history.

From Coetzee I discovered that Millin had written several novels, mainly between the wars, where one of the main themes was the evils of miscegenation and “tainted blood”. Coetzee traces this concern to 19th-Century scientific theories, especially Darwinism, and the concept of superior and inferior races. In the 1920s and 1930s when Millin wrote her novels, such views were politically correct, especially in South Africa, though her novels were more popular overseas. But after the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials and the discrediting of Nazi race theories, such views became politically incorrect, except in ultra-rightwing circles.

January 7, 2018

CS Lewis’ Response to Critics of The Lord of the Rings: The Dethronement of Power | Earth and Oak

When Tolkien began there was probably no nuclear fission and the contemporary incarnation of Mordor was a good deal nearer our shores. But the text itself teaches us that Sauron is eternal; the war of the Ring is only one of a thousand wars against him. Every time we shall be wise to fear his ultimate victory, after which there will be “no more songs.”

Source: CS Lewis’ Response to Critics of The Lord of the Rings: The Dethronement of Power | Earth and Oak

December 31, 2017

Stephen Gawe: 80th birthday party

I was pleased to be invited to the 80th birthday party of an old friend Stephen Pandula Gawe.

[image error]

Victor Mkhize & Stephen Gawe at 1963 ASF conference. Behind is Revd Midian Msane.

We first met at student conferences in the 1960s. He was a student at the University College of Fort Hare in the Eastern Cape, and I was a student at the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg, more than 500 miles away. We met at the annual conference of the Anglican Students Federation (ASF) held at Modderpoort in the Free State in July 1963. He made a sufficiently strong impression on me for me to propose him for the office of president of the ASF, but eventually he was elected as vice-president.

At a concert held during the conference he acted an impression of a witchdoctor (igqira) holding a consultation with a client, and diagnosing what ailed them.

[image error]

Stephen Pandula Gawe, Julu 1963

He was fairly active in national student affairs generally, as after the ASF conference he went on to the national council meeting of the Student Christian Association (SCA) which was being held in Johannesburg, where I lived at that time. They were involved in a heavy constitutional wrangle. The SCA had four sections — Afrikaans, English, Black and Coloured. The Afrikaans section, which was numerically strongest and the best funded, wanted the SCA to split into four separate and independent organisations, in line with the current government policy of apartheid. Since the SCA was then the only ecumenical Christian student organisation in the country, Stephen and others were concerned that splitting it up like that would further divide Christian students along racial lines, since they were also being forced to attend separate universities.

We went to visit him during the SCA Council meeting, and when he had a free evening brought him home to have dinner at my place with a couple of other ASF members, and took him back to the Priory of the Community of the Resurrection in Sophiatown, where he was staying during the council meeting. That cemented our friendship, meeting outside of conferences and formal gatherings, and just chatti9ng about all sorts of things.

The following Sunday a group of us who had been at the ASF conference went in a group to the Anglican Church in Meadowlands, Soweto, where the Revd John Davies, the Anglican chaplain at Wits University was celebrating the Mass. It was the home parish of one of the students, Cyprian Moloi, who was translating a speech the rector of the parish gave about money, in Sesotho, but when the rector said, “Morena ye-ye-ye-ye” Cyprian collapsed into giggles, as did half the congregation, who were waiting for the translation. We took Stephen Gawe to the station afterwards, to get the train back to King William’s Town — a sad parting, for we would not see each other for another year. We had to use separate entrances to enter the station, but all met up again on the platform. The authorities could segregate the entrances, and there were separate black and white carriages on the trains, but they had not yet got around to providing separate trains running on “own lines”. If Verwoerd had not been assassinated a few years later they might well have done so.

[image error]

Stephen Pandula Gawe, Modderpoort, July 1964.

We met again at the next ASF conference in July 1964, also at Modderpoort, which must have been the coldest place in South Africa and it was the coldest winter in years. Driving there from Pietermaritzburg we had watched the car temperature gauge dropping as we climbed Van Reenen’s Pass, and for the rest of the way the car heater was completely ineffective. There was snow lying around on the sides of the road that had not melted since it had fallen a fortnight earlier.

When everyone else had gone to bed Stephen Gawe and I stayed up talking and playing chess (at which he easily beat me every time). We discussed possible candidates for the election of office-bearers, which produced an interesting black-white split in the election of the vice president. Most of the black members voted for a white guy, Clive Whitford, and most of the whites voted for a black guy, Jerry Mosimane. At 4 am, having talked ourselves to a standstill, we said Mattins together and lay down to sleep beside the remains of the fire in the common room.

Stephen Gawe had to leave early to attend the SCA Council meeting again, and we took him to Modderpoort station to catch a train at about 1:30 am. It was a steam train, and while it was standing in the station, and we were all wrapped in blankets, the escaping steam condensed on the smoke deflectors and turned straight to frost. As the train pulled out and we waved goodbye, I little suspected that I would not see Stephen Gawe in South Africa for another 35 years.

Six weeks after the ASF conference we had the news that Stephen Gawe and three other Fort Hare students had been arrested and were under 90-day detention. Eventually he was brought to trial, found guilty of being a member of the banned ANC, and sentenced to a year’s imprisonment. In January 1966 I went to the UK to study for a Postgraduate Diploma in Theology at the University of Durham. When Stephen Gawe was released from prison he wrote to me to say that he to was coming to the UK to study, but he was leaving on an exit permit, which meant that he could not return to South Africa while the apartheid regime lasted.

[image error]

Stephen Pandula Gawe, London, December 1966

In December 1966 he arrived in London and we got together again, as I was spending the Christmas vacation there. He was staying at the Franciscan Priory at Plaistow, while I was staying with the Sweet family in East Wickham, Kent, for the Christmas vac. Mervin Sweet had been the university chaplain when I was a student in Pietermaritzburg, and had moved to the UK a couple of years earlier.

We saw quite a bit of each other then, and we compared notes on the culture shock we had experienced on arriving in England.

We met again in June 1967, in Oxford, where he was studying, and we got together with a few other South African students there. I was staying with the Revd Tom Comber, who had been the first chaplain of the ASF when it started in 1960, and though he had not known Stephen Gawe then, they became friends and continued to keep in touch while Stephen was at Oxford, and afterwards as well.

In July 1967 Stephen phoned me, and said he was getting married to Tozie Mzamo, and wanted me to be best man at his wedding, which made me feel undeservedly honoured.

[image error]

Wedding of Stephen Gawe and Tozie Mzamo, Oxford 1967

We continued to see each other occasionally, including once at a seminar for South African students in the UK, and discussing what those who returned to South Africa could do. It had a pretty wide range of South African students there, and I was rather surprised to find no mention of it in my SB file when I got a copy of it some 40 years later.

[image error]

Steve Hayes and Stephen Pandula Gawe, Hatfield, Pretoria, July 2001

I returned to South Africa in July 1972, and we kept in touch by correspondence for a while after that, and then lost touch. The next contact I had with him was a phone call out of the blue in July 2001. He was in Pretoria, and had found me in the phone book. We met for dinner, and he gave me the sad news that Tozie had died. He was now in the diplomatic service, and was about to go to Denmark as South African ambassador there. I tried a few times to contact him by e-mail, but failed, and so we lost touch again.

But his daughter Nomtha, whom I had never met, got in touch, and we were able to meet her and her husband Ant Gray when they visited South Africa. She said that she too has having great difficulty in seeing her father, who was being kept incommunicado by his second wife, who seemed, to all accounts, to be the classic fairy-tale wicked stepmother. I had hoped, in a kind of reciprocal arrangement for being best man at his wedding, to invite him to our 40th wedding anniversary celebration, but no word came from behind the blank walls and windows of the fortress in which he was held. So great was our joy when we were invited to his 80th birthday party, though right up to the last minute there was some doubt about whether he would be allowed to attend.

So we went to Joburg for the party, which was suitably blessed by a traditional Highveld afternoon thunderstorm, with hail drumming on the metal roof of the garage. Pula! one might say, if anyone spoke Tswana. We met Stephen’s other daughter Vuyo, his grandchildren Jonas and Ruby, and several other relatives.

[image error]

Stephen Gawe with daughters Nomtha (standing) and Vuyo. Observatory, Johannesburg, 30 Dec 2017

And getting together after all this time puts me in mind of the theme tune of the TV cop series New Tricks:

It’s all right, it’s OK

Doesn’t really matter if you’re old and grey

[image error]

Stephen Gawe and Stephen Hayes, 55 years later. 30 Dec 2017

Some members of the extended family we had met before

[image error]

The Gawe family

Also there was Stephen’s younger brother Ncencu (spelling?)

[image error]

Vuyo and Ncencu Gawe

And an old school friend, Pinkie Nxumalo.

[image error]

Syephen Gawe & Pinkie Nxumalo, with grandson Jonas in the background

Pinkie Nxumalo was regretting that people did not write down their stories, and said it was important that people should tell stories, which is one reason this post is so long, because I took her words seriously. I urged Stephen to write down some of his stories, but he feared there were too many gaps in his memory, and so they might not be accurate.

Pinkie herself had an interesting life. She trained as a doctor, went to the UK for further study, and spent some years there, and we gave her and her daughter Sibongile a lift home to Midrand. I hope she does get to write down her story.

But I’ve tried to tell a little of the story of Stephen Pandula Gawe as I knew him, and hope I get to see him again before his 81st birthday.

God grant you many blessed years!

I

December 26, 2017

Christmas baptism

On Christmas day we baptised Charles Nkosi as Christos, which means that Christmas will be his name day from now on.

When we started holding services in Atteridgeville two years ago, Demetrius Mahwayi brought his friend Charles along. Charles became a regular, and last year we took him to the Christmas Liturgy at St Nicholas Church in Brixton, and after the service he said he wanted to be baptised. So after a year of preparation Fr Elias Palmos at St Nicholas suggested that it would be appropriate for him to be baptised there the following Christmas, which was yesterday,

[image error]

Exorcisms at the church door (all photos by Jethro Hayes)

After four exorcisms, he faced west and rejected the devil, turned to the east and accepted Christ: I believe in him as King and God.

He and his sponsor (Demetrius) said the Symbol of Faith.

[image error]

Rejecting the devil and accepting Christ

And the Priest says:

Bow yourself also before Him

And the catechumen bows himself, saying,

I bow myself to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, the Trinity one in essence and undivided.

[image error]

I bow myself to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit

And the priest says

Blessed is God, Who desireth that all men should be saved, and should come to a knowledge of the truth…

The the priest blesses the water for baptism

[image error]

The blessing of the water

Thou didst sanctify the streams of Jordan sending down from heaven Thy Holy Spirit, and didst crush the heads of the dragons that lurked therein. Do Thou therefore, O King, Lover of Mankind, come now through the descent of Thy Holy Spirit, and sanctify this water.

[image error]

The priest blesses the Oil of Gladness, with which the catechumen is anointed before being baptised, , and some is poured into the baptismal water.

The catechumen is anointed for the lealing of soul and body, on the ears for the hearing of faith, on the feet that he may walk in the path of God’s commandments,

He then enters the water, and is immersed three times by Fr Elias, assisted by Fr Frumentius.

[image error]

The servant of God Christos is baptised in the name of the Father. Amen. And of the Son, Amen. And of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

And after being baptised, the newly illumined servant of God Christos is given a white robe and a cross.

[image error]

Give unto me a shining robe, O Thou who clothest thyself with light as with a garment

And having been baptised he is anointed with the Oil of Holy Chrism, which some call confirmation, for the priest prays to God

… Who now art well-pleased for thy newly-illumined servant to be born again through water and the Spirit, and who grantest unto him remission of sins, both voluntary and involuntary,: Do Thou Thyself O Master, O Compassionate King of all, grant him also the seal of Thy Holy, all-powerful and worshipped Spirit, that the communion of the Holy Brody and precious Blood of Thy Christ. Keep him in Thy Sanctification, confirm him in the Orthodox faith, , deliver him from the evil one and all his devices…

And then the priest cuts his hair in the form of a cross.

The priest, the newly-baptised and his sponsor go around the font, while the people sing “As many as have been baptised into Christ have put on Christ, Alleluia.

[image error]

As many as have been baptised into Christ have put on Christ, Alleluia.

And finally the newly-illumined servant of God receives the Holy Communion of the Body and Blood of Christ.

[image error]

Receive the Body of Christ, taste the Fountain of Immortality

Afterwards I took Christos, his sponsor Demetrius and friend Artemius back to Atteridgeville, with Christos’s aunt, who had come to witness his baptism. She promised to join us again. So one brings another.

[image error]

Demetrius Mahwayi and his spiritual child Christos.

December 24, 2017

Where have all the shanties gone?

For the last couple of months, as we have made our fortnightly trip to Atteridgeville for the Hours and Readers Service, we have watched the growth of a shanty town on the hillsides just before the entrance to Atteridgeville West.

[image error]

New informal settlement between Saulsville and Atteridgeville West, Tshwane. 29 Oct 2017

On another hillside, on the west side of the Atteridgeville West entrance road, there was another, official settlement. We’ve been watching that for two years, as the municipality installed infrastructure — rows of toilets on the hillside, then roads, then electricity poles. It grew slowly, very slowly.

[image error]

New informal settlement near Atteridgeville, Tshwane.

Fortnight by fortnight we watched as it grew. There were fences between the shacks, which made it look organised. Unlike the official settlement, however, there was no infrastructure — no roads, no sewerage, no power lines.

[image error]

For at least a kilometre along the main road, the shacks spread

Along with the informal settlements, however, there were informal rubbish dumps along the sides of the roads. They too have grown enormously in the last few months. They are on both sides of the R104 leading west.

[image error]

Informal settlements and informal rubbish dumps. Atteridgeville West.

When we went there this morning, I was curious to see how many more shacks there would be, but there were none.

All the ones that had been there less than two months ago had gone, vanished as if they had never been. The hillsides were bare, as they had been a year ago.

The rubbish dumps, however, remained.

Who removed the shacks?

Space aliens? Red ants? The municipality?

Were they ever there? If I’d not taken these photos I might have wondered if I’d imagined them.

Where did the buildings go? Where did the people go? Where are they now?

I just wish that whoever removed them did as good a job at removing the rubbish.

December 17, 2017

The Story of the Treasure Seekers

The Story of the Treasure Seekers: Being the Adventures of the Bastable Children in Search of a Fortune by E. Nesbit

The Story of the Treasure Seekers: Being the Adventures of the Bastable Children in Search of a Fortune by E. Nesbit

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I had been curious about this book ever since first reading The Magician’s Nephew about 55 years ago, when C.S. Lewis wrote, “In those days Mr Sherlock Holmes was still living in Baker Street and the Bastables were looking for treasure in the Lewisham Road.”

I knew about Sherlock Holmes and Baker Street, but the Bastables I had never heard of, though Lewis clearly assumed that his readers, or most of them had. So it seemed that an important part of my literary education was missing. It also said something about the “implied reader” of Lewis’s Narnia stories (see here for more about the implied reader: Children’s Literature | Khanya.

In the story the Bastable family has come down in the world, so the six Bastable children come up with various schemes to restore the family fortunes. Most of their schemes lead them into a certain amount of difficulty, but in most cases the difficulty is resolved, usually in their favour, though not to the extent that it would restore the family fortunes.

In the edition I read there was an introduction with a brief biography of Edith Nesbit and an account of her work. It notes that she and her husband Hubert Bland were Fabian socialists, Though many of the Fabian socialists were middle-class I was rather surprised that Nesbit wrote such a middle-class book.

Certainly her implied readers were middle class, and though the family is reduced to having only one servant, they do have a servant, whom the children rather despise for her lack of competence and skill in cooking and cleaning. At no point does Nesbit indicate that she does not share the view of the narrator (one of the children, who is 12 years old at the time of the story), though she does somewhat satirise his relations with his siblings and others. The middle-class characters are human, the maid rather less so.

Also, the restoration of the family fortunes is seen, by both children and adults, almost entirely in capitalist terms. The primary need is capital, to make the father’s business prosper.

Perhaps this was dictated by the publishing world of the time. Perhaps the implied readers were middle class because at the time it was only the middle class who would buy books for their children, and therefore that would be the only kind of book that publishers of the time would accept. But even so, Dickens managed to get several books published that show more sympathy for the working-class poor than Nesbit seems to. Dickens does try to conscientise his readers, Nesbit does not, unless I’m missing something.

A book I did read as a child, and fairly recently re-read as an adult, is The Treasure Hunters by Enid Blyton (my review here). Having at last read Nesbit’s book, I think I can see where Blyton nicked elements of the plot for her book, written 40 years later. It has all the deficiencies of Blyton’s style, but many elements of the story are similar — a search for treasure to restore the family fortunes. But there is one contrasting element — in Blyton’s version it is a capitalist businessman who is the villain of the piece. I’ve never thought of Enid Blyton as a socialist, and her books, like Nesbit’s, have middle-class children as the “implied reader”, but in this story, at least, she is far more critical of capitalism than Nesbit is, and perhaps some of my own mistrust of capitalism stems from reading it as a child.

December 15, 2017

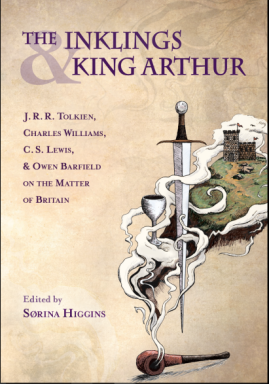

A Call for Guest Posts: The Inklings and King Arthur with Guest Editor David Llewellyn Dodds

It is an intriguing fact of literary history that the Inklings were individually fascinated by the Arthurian legends. Christopher Tolkien’s publication of his father’s The Fall of Arthur caused a literary sensation in 2013, highlighting how deeply the Matter of Britain is in conversation with Tolkien’s legendarium. Arthurian themes run through C.S. Lewis’ fiction—including the eruption of the whole Arthurian landscape into his dystopic That Hideous Strength—and he approaches Arthurian material as a scholar. Charles Williams, who published two Arthurian books of poems and one Grail novel, left much of his work on his desk after his sudden passing in 1945. Owen Barfield’s fiction dances with Arthurian themes, and many of us encountered Arthur first through Roger Lancelyn Green’s adaptation of Morte D’Arthur.

It is an intriguing fact of literary history that the Inklings were individually fascinated by the Arthurian legends. Christopher Tolkien’s publication of his father’s The Fall of Arthur caused a literary sensation in 2013, highlighting how deeply the Matter of Britain is in conversation with Tolkien’s legendarium. Arthurian themes run through C.S. Lewis’ fiction—including the eruption of the whole Arthurian landscape into his dystopic That Hideous Strength—and he approaches Arthurian material as a scholar. Charles Williams, who published two Arthurian books of poems and one Grail novel, left much of his work on his desk after his sudden passing in 1945. Owen Barfield’s fiction dances with Arthurian themes, and many of us encountered Arthur first through Roger Lancelyn Green’s adaptation of Morte D’Arthur.

King Arthur seems to be one of the centrifugal forces of the Inklings as a loose literary collective. It is this observation that drew a…

View original post 255 more words

December 12, 2017

Roman Catholic radicals and Orthodoxy

Jim Forest has just written a biography of a Jesuit priest, Daniel Berrigan, who died last year.

Why would an Orthodox Christian write a biography of a radical Roman Catholic priest, and why would an Orthodox Christian want to read such a thing? Jim Forest himself gives an answer to that specific question here: FATHER DANIEL BERRIGAN, SJ: WHY SHOULD AN ORTHODOX CHRISTIAN BE INTERESTED IN HIM? by Jim Forest | ORTHODOXY IN DIALOGUE:

“And just what is it,” my friend asked, “that was so Christ-revealing about Berrigan’s life?”

When he died last year, age 94, obituaries focused on the anti-war aspects of Berrigan’s life: he was eighteen months in prison for burning draft records in a protest against conscription of the young into the Vietnam War; then there was a later event in which he was one of eight people who hammered on the nose cone of a nuclear-armed missile. No one has kept count of his numerous brief stays in jail for other acts of war protest. He was handcuffed more than a hundred times.

But it raises other wider questions too.

For the last few years the “mainstream” media have focused on the phenomenon of the “religious right”, but fifty years ago the focus was more on the “religious left”, exemplified by people like Daniel Berrigan, protesting against the Vietnam War.

I first learned of Daniel Berrigan in 1969, through a radical Christian magazine called The Catonsville Roadrunner. The magazine was inspired by the actions of Daniel Berrigan and his brother Philip, who with several others had broken into an office containing records of military conscription and publicly burnt them. It became a legendary act of Christian civil disobedience

[image error]

Ikon magazine cover, designed by Hugh Pawsey, my fellow student at St Chad’s College

Jim Forest himself was involved in a similar act of civil disobedience in Milwaukee, for which he was jailed.Those were interesting times, the late 1960s and early 1970s, the age of hippies and moon landings and radical Christian protests. Inspired by The Catonsville Roadrunner I and a group of friends launched our own radical Christian magazine in South Africa, called Ikon.

So I want to turn Jim Forest’s question around. Not “Why should Orthodox Christians be interested in the life of a Jesuit priest like Daniel Berrigan?” but why did so many people involved in the radical Christian scene of the late 1960s become interested in Orthodoxy?

One factor may have been that at that time Orthodoxy was peculiarly powerless.

In 1968 I visited St Sergius Orthodox Church in Paris, and there was a seminary in the crypt of the church where the students lived in humble and primitive conditions — sleeping cubicles separated by threadbare curtains, and an open drain running down the middle of the floor. That, to me, represented the poverty of him who came to be poor among the poor, rather than the power and prestige needed to maintain a religion.

Most of the traditionally Orthodox countries were under communist or Muslim rule, and in those places Orthodox Christians were treated as second-class citizens, and deprived of civil rights. Many Orthodox Christians in the West were refugees and asylum seekers. or children of refugees and asylum seekers.

Another reason for the attraction of Orthodoxy for radical Christian activists was that Orthodoxy had a firm theological base. In the West, theological liberalism led to political conservatism and vice versa. Theological liberalism was embarked on a project to adapt the Christian faith to the modern world, and that meant adapting Christianity to support the status quo. Radical Christians wanted to change the status quo on earth, so that God’s kingdom would come and God’s will be done on earth, as it is in heaven.

G.K Chesterton said that the modern young man would never change the world, for he would always change his mind. Christians who are always changing their theology will never change the world.

This can be seen in the media expectations of Roman Pope Francis. They are looking to him to bring about change in the Roman Catholic Church. Will he change the theology and bring it up to date? But most of the time they are disappointed, because he criticises the state of the world from the point of view of existing theology — the wars, civil repression and exploitation that continue pretty much as they did in the 1960s.

There is much talk about “progressive” theology and “progressive” politics, but what do we mean by “progress”? As G.K. Chesterton put it, more than a century ago now:

Progress should mean that we are always changing the world to suit the vision. Progress does mean (just now) that we are always changing the vision. It should mean that we are slow but sure in bringing justice and mercy among men: it does mean that we are very swift in doubting the desirability of justice and mercy: a wild page from any Prussian sophist makes men doubt it. Progress should mean that we are always walking towards the New Jerusalem. It does mean that the New Jerusalem is always walking away from us. We are not altering the real to suit the ideal. We are altering the ideal: it is easier.

Silly examples are always simpler; let us suppose a man wanted a particular kind of world; say, a blue world. He would have no cause to complain of the slightness or swiftness of his task; he might toil for a long time at the transformation; he could work away (in every sense) until all was blue. He could have heroic adventures; the putting of the last touches to a blue tiger. He could have fairy dreams; the dawn of a blue moon. But if he worked hard, that high-minded reformer would certainly (from his own point of view) leave the world better and bluer than he found it. If he altered a blade of grass to his favourite colour every day, he would get on slowly. But if he altered his favourite colour every day, he would not get on at all.

And that is why I think that some radical Christian activists have been attracted to Orthodoxy. And that complement’s Jim Forest’s point about why Orthodox Christians should be interested in people like Daniel Berrigan — because people several people who have shared the interests of Daniel Berrigan have also become interested in Orthodoxy. So by all means by and read Jim Forest’s book about Daniel Berrigan.