Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 36

November 8, 2016

The USA gets its very own Jacob Zuma

There’s probably going to be a lot of anguish about the election of Donald Trump as president of the USA, and a lot of finger-pointing and blaming from those who think it is a disaster. But his election was a foregone conclusion. It was already decided on 26 July 2016 when the Democratic National Convention chose Hillary Clinton over Bernie Sanders as their candidate for president.

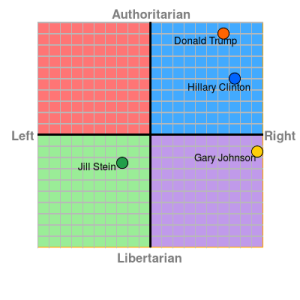

As usual, The Political Compass nailed it:

Despite most polls indicating that Bernie Sanders would fare significantly better than Clinton against Trump, the party clearly wanted Hillary. This surely suggests that when push comes to shove, the Democratic establishment would prefer Hillary to lose the presidency than Sanders to win it.

In my view by November it had come down to a choice between a loose cannon and a carefully-aimed one: Hillary Clinton had set her sights on the Syrian president, and saw his removal as a priority. Donald Trump seems happy to nuke anyone on the spur of the moment. In either case it would seem likely to lead to World War III, and America has just experienced its Polokwane moment.

In my view by November it had come down to a choice between a loose cannon and a carefully-aimed one: Hillary Clinton had set her sights on the Syrian president, and saw his removal as a priority. Donald Trump seems happy to nuke anyone on the spur of the moment. In either case it would seem likely to lead to World War III, and America has just experienced its Polokwane moment.

Now I’m seeing all sorts of tweets blaming it on bigotry, or saying that it is a victory for bigotry. But I’ve been seeing tweets and Facebook posts from Clinton and Trump supporters for the last nine months or more, and there has been plenty of bigotry from both sides, not to mention vitriol, ad hominem attacks and all-round petty spitefulness.

But the biggest bigotry of all was from the Democratic National Convention — Would Bernie Sanders Have Defeated Donald Trump In The 2016 Presidential Election Instead Of Hillary Clinton?:

Sanders would have bested the business billionaire in a landslide, while Clinton was projected to lose to Trump by at least two percent, according to polls conducted in May. Sanders also won in a major upset against his opponent in Michigan and Wisconsin – two states Clinton may have lost to Trump Tuesday, according to incoming polls on Election night.

There’s the core bigotry that won Trump the election, right there.

November 7, 2016

That hideous strength and Rhodes must fall

That Hideous Strength by C.S. Lewis

That Hideous Strength by C.S. Lewis

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

I’ve just finished reading That Hideous Strength again. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve read it, at least six or seven times, and each time I find something new.

It has been described as C.S. Lewis’s attempt at a Charles Williams novel, and that is a fairly accurate description. The first time I read it, as a teenager, a lot of the literary allusions went right over my head. Mr Fisher-King, for example. I first became aware of the significance that when reading a novel by Robert Holdstock, either Mythago Wood or The Fetch, and the significance escaped me there too at first. Now I’ve been reading a bit more Arthurian literature, and suddenly a lot of the references make more sense, just as reading The Mabinogion helped to make sense of The Owl Service.

But the book that made a lot of things fall into place this time round was The Cult of Rhodes, which I read about three months ago, and reviewed here The cult of Rhodes.

Right at the end of That hideous strength Professor Dimble is talking about Logres and Britain. In Lewis’s mythology, and one could perhaps say in the Inklings’ mythology, Logres is Britain’s better half, or better self. Each nation has, as it were, a guardian angel and a tempting demon, and in the case of England the former is Logres and the latter is Britain.

Dimble describes this as a haunting:

How something we may call Britain is always haunted by something we may call Logres. Haven’t you noticed that we are two countries? After every Arthur, a Mordred; behind every Milton, a Cromwell; a nation of poets, a nation of shopkeepers; the home of Sidney — and of Cecil Rhodes.

I had to look up Sidney, and I’m pretty sure it refers to Sir Philip Sidney (1554-1586).

But what struck me most was the casual, almost passing reference to Cecil Rhodes.

Rhodes came in for a lot of publicity last year, over 100 years after his death, when a group of students at the University of Cape Town demanded that a statue of Rhodes be removed from the campus. And there were similar demands about a statue of Rhodes in Oxford, where Lewis taught.

As I said, I’ve read That hideous strength six or seven times, but it was only this time around that it stuck me that Cecil Rhodes might have been a model for one of the villains of the piece, Lord Feverstone, alias Dick Devine. And if I hadn’t recently read The cult of Rhodes I might not have noticed it.

Dick Devine appears as a villain in the first book of Lewis’s Cosmic Trilogy, Out of the Silent Planet, and reading that with a picture of Rhodes in the back of one’s mind makes a lot more sense. Lewis isn’t writing allegory here; it’s no good looking for one-to-one correspondences between the life and career of Cecil Rhodes and the life and career of Dick Devine, but there is a lot of similarity in their values and their goals. Devine is the archetypal financial wheeler-dealer, the imperialist trying to get hold of other people’s mineral resources, the ugly face of international capitalism.

November 2, 2016

Election rhetoric

One of the problems with US election rhetoric is that it never seems to stop. For two years out of four they are having presidential elections, and much of the other two are taken up with congressional elections. At least here in South Africa we only have a few months of it. The date of the election is announced, parties register their participation, and the issues are debated, and then we vote.

In the days before the Internet, American elections were somewhat remote. We’d read about them in the newspapers, usually on the inside pages until a day or two before the election, and then they would be on the front pages a couple of days before and a couple of days after, and that would be it. Thereafter we’d only read about the US president when the US had bombed some place or other, or was threatening to do so.

But the Internet opened up a whole new world of spite and vituperation, as one discovered how much Americans who hadn’t voted for their president hated him. It started with George H.W. Bush (before him the Internet was only a twinkle in Al Gore’s eye), and went on to Bill Clinton (or Klinton, as most of his detractors called him). Now it’s reached the point where every second post I read on Facebook is slagging off the unpreferred candidate(s) and their supporters. I’ve commented on that here, And it seems that even some South Africans are getting in on the act, engaging in fiercely partisan campaigning, as if they lived in the USA.

And its ironic that usually there is very little difference between the candidates of the two major parties in the US elections, yet the closer their political positions, the more vicious becomes the rhetoric of their supporters. There so little difference that those small differences must be hyped and exaggerated to make them seem more significant than they are. Americans talk about “liberals” and “conservatives” and “left” and “right” but in the last four elections the candidates of the biggest parties have all been in the right-wing authoritarian quadrant of the political compass.

And its ironic that usually there is very little difference between the candidates of the two major parties in the US elections, yet the closer their political positions, the more vicious becomes the rhetoric of their supporters. There so little difference that those small differences must be hyped and exaggerated to make them seem more significant than they are. Americans talk about “liberals” and “conservatives” and “left” and “right” but in the last four elections the candidates of the biggest parties have all been in the right-wing authoritarian quadrant of the political compass.

I’ve also begun to see people threatening to “unfriend” others on Facebook for expressing opinions they disagree with, which they often describe as “bigotry”. And here was I thinking that bigotry was refusing to listen to opinions you disagree with, or that offend you. Well, I did unfriend one person on Facebook, but for a slightly different reason. It wasn’t that his opinions offended me, but that my opinions offended him, and I valued his friendship too much, so unfriended him on Facebook so that we could stay friends in real life, and he would not be exposed to the opinions that offended him.

Quite a lot of my friends on Facebook are family. You can choose your friends, but you can’t choose your family and I think it’s good to be exposed to opinions you disagree with. Even if we disagree, we are still family. Sometimes I don’t think anything will be gained by discussing the differences of opinion, so if someone says something I disagree with it, I pass over it and ignore it. If I think there is a possibility for rational discussion, I might comment, expressing a different point of view. But I don’t see the point in unfriending people over a mere difference of opinion. When I was much younger I did that a couple of times, and have often regretted it since. It was because I was being priggish and uncharitable.

The thing that bothers me most about it, though, is that so much of the debate seems to be about personalities rather than policies. More than 95% of the arguments about the current US elections seem to be about the character of the candidates rather than their policies, and much of that seems to be based on innuendo and fake news sources.

The thing that bothers me most about it, though, is that so much of the debate seems to be about personalities rather than policies. More than 95% of the arguments about the current US elections seem to be about the character of the candidates rather than their policies, and much of that seems to be based on innuendo and fake news sources.

And that’s why I like the graphic on the left.

Yes, they are sinners, but so are we all.

Yes, there are certain qualities that are desirable in someone who is going to lead a country, and so we speak of the difference between a statesman and a politician, and most political systems reward those who are best at political wheeling and dealing, and not those who give visionary leadership. But the petty vituperative spitefulness one sees every day on social media really is uncalled for.

October 25, 2016

The Owl Service: reading and culture

The Owl Service by Alan Garner

The Owl Service by Alan Garner

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I’ve read this 2 or 3 times before but never liked it as much as Alan Garner‘s first three books, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, The Moon of Gomrath and Elidor. I’ve read those several times, and enjoyed them each time. But The Owl Service has always seemed unsatisfactory, and made little sense.

This time, however, I read “Math son of Mathonwy” from The Mabinogion first, and that helped to make a little more sense of the plot. The story of Math, and his nephew Gwydyon, and grandnephew Lleu is frequently referred to in The Owl Service, but in a fragmentary and disjointed way. So reading the story of Math helps to put it in context. But I still didn’t like it as much as Garner’s earlier books.

But this raises the interesting question of dependency in literature, and how much knowledge can be assumed in readers. In quite a lot of English fiction before the mid-20th century, some knowledge of the Bible on the part of the readers could be assumed, and biblical allusions could be understood by most readers with little difficulty.

C.S. Lewis’s Narnia stories have an underlying biblical theme, but are not dependent on that. It is quite possible to enjoy the stories without familiarity with the Bible, though familiarity with the Bible will reveal deeper levels of meaning. The same applies to Lewis’s science fiction stories. Knowledge of the Bible can enhance one’s understanding of the stories, but it is not a necessary precondition of understanding. This also applies, mutatis mutandis to Garner’s earlier books too. There are references to Celtic or British mythology (even recent modern mythology, like the notion of the “old straight track”), which one doesw not need to be familiar with to enjoy the books, because it is all sufficiently explained in the stories themselves.

But the reader of The Owl Service misses a great deal if not familiar with The Mabinogion, or at least the story of Math.

Quite a lot of earlier English literature, however does depends on familiarity with other literature, such as the Bible, or the mythology of ancient Greece and Rome, and other works. There was a time when this foundational literature was regarded as a normal part of education, but it seems to be becoming less so. I’m sure my knowledge of classical mythology lacks a great deal, but I’m sometimes surprised at the apparent lack of such knowledge in quiz show contestants.

I suspect that I may have missed quite a lot in reading Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, because of my unfamiliarity with Milton.

So reading The Owl Service is quite salutary, because it shows how it can be difficult to translate books from one culture to another, quite apart from the difficulties in translation from one language to another. The differences between the British and American editions of the Harry Potter books are a case in point, and I’ve been reading a thesis about the difficulty of translating them into SePedi, in a culture in which people who are suspected of witchcraft are still sometimes lynched.

October 22, 2016

Acceptable

In the past couple of weeks I’ve been struck by the use of the word “acceptable” in connection with moral issues, and it bothers me, because I always want to ask “acceptable to whom?” It begs, or evades, the question of who has the power to force acceptance.

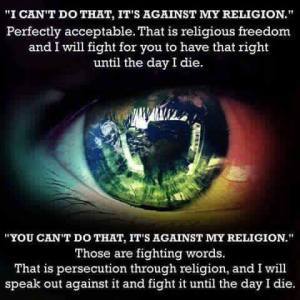

When someone posted this graphic on Facebook, I questioned it.

When someone posted this graphic on Facebook, I questioned it.

To whom is it “perfectly acceptable”?

Not to the South African Defence Force back in the 1960s when a white Christian military conscript walks out of the room on the first day of basic training after the Sergeant tells them “Now we are going to teach you how to shoot kaffirs.” To the detention barracks with him.

And then someone else posts, “I’d love your input and feedback! Is violence ever acceptable in working for justice? If yes, then what forms and when? If no, then what are the alternatives?”

And again, I want to ask “acceptable to whom?”

And then “Whose concept of justice?”

The simple answer, of course, is that violence is acceptable to militarists and unacceptable to pacifists.

“Acceptable” always raises the question of power relations and who has the power to decide what they will accept and what they will not accept.

Bombing civilians in Yugoslavia is acceptable collateral damage to the US government when the US government does it. Bombing civilians in Syria is an unacceptable war crime to the US government when Russia does it.

Is bombing civilians acceptable?

It all depends on who is doing the bombing and who is doing the accepting.

Was it Dame Edna Everidge or Tannie Evita Bezuidenhout who said, “That man in the raincoat showed me something quite unacceptable.”

October 15, 2016

Student power

This week we heard that Bob Dylan had been awarded the Nobel Prize for literature, and on university campuses throughout the country, and sometimes in the streets outside, his words were coming true:

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is

Rapidly agin’

Please get out of the new one

If you can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin’.

What does a 50-year-old song have to say to us today? Many of the parents of today’s protesting students weren’t even born then. yet when I see the protesting students on TV news I think the times haven’t changed at all. As Bob Dylan said in another of his songs, Motopsycho Nightmare, “Oh no, no, I’ve been through this movie before”

What does a 50-year-old song have to say to us today? Many of the parents of today’s protesting students weren’t even born then. yet when I see the protesting students on TV news I think the times haven’t changed at all. As Bob Dylan said in another of his songs, Motopsycho Nightmare, “Oh no, no, I’ve been through this movie before”

I belong to the Student Power generation.

From about 1968 to 1976 there were student protests around the world. In many places students allied with the working class, and there were quite a few changes in the way that higher education was run. But there were also important changes that were not made, an this article describes one of them, which sparked off the current student protests

Under-funding, not protests, is driving South African universities down global rankings.

I witnessed the very beginning of the Paris Spring of 1968. I was in Paris in April 1968 for Holy Week and Easter at the Saint-Serge Institut de Theologie Orthodoxe, as part of a course in Orthodox theology for non-Orthodox theological students. There were the beginnings of student demonstrations in the streets, and there was talk of student power in the air. My friend Hugh Pawsey and I, both from St Chad’s College, Durham, were broke. We had no food, no money and just tickets back to England on the ferry, so we returned to England.

When we got back to St Chad’s College, the staff had introduced a new repressive regime, and we staged a minor revolt over that, partly at the instigation of Dr Walter Hollenweger, whom we had visited in Geneva, and made several suggestions. In the wider University of Durham a group of Marxist students were holding a sit in in the university administration officers, and the police were taken by surprise. Durham, they said, was the last university where they expected trouble, since it was known to be the most middle-class university in Britain.

The Dean of the Theology Faculty, Prof H.E.W. Turner, called a meeting of the entire faculty, staff and students — an unprecedented step. By then the student protests in Paris were in full swing, and students were setting up barricades of burning vehicles and the like. Prof Turner thought we ought to discuss the way the faculty was run. He was being what administration fundis call “proactive” — much better for the Dean to call such a meeting ahead of a student demand for one. One of the students said so, “You’re just worried that we’re going to pick up paving stones from Saddler Street and toss them into your office window”. No, Prof Turner said, it wasn’t that at all, he just wanted to ensure better staff-student relations. Whatever the case may have been, I suspect that had there not been such student protests in Paris, the meeting would never have been called.

That was in May 1968, and I don’t know if anything ever came of it, because in July I returned to South Africa, and spent my last couple of months as a full-time student at St Paul’s College in Grahamstown. There were some student protests in South Africa over the next few years, and I knew some of the people involved, but was no longer a full-time student. On one occasion there was a police riot in St George’s Anglican Cathedral in Cape Town, where police chased protesting students into the cathedral and beat them up there. It culminated in the 1976 protests, mainly of school children, where the police killed several.

But all this lies long in the past.

I am not now a student, nor even the parent of a student, so why am I writing about this?

It doesn’t directly affect me whether fees fall or not. It is not my studies or my children’s studies that will be affected if we can’t afford them. So perhaps it’s time to take Bob Dylan’s advice and just shut up and get out of the new road and don’t criticise what you can’t understand. Except that I have been through this movie before. What is different and what is the same? The paving stones in Saddler Street, Durham have become the concrete litter bins of Wits University campus that students break up for missiles, but what else has changed, and what is the same.

There have been calls for the decolonisation of education, and that was something that should have been done 20 years ago, but wasn’t. There was talk of the need for “transformation”, but plans for transformation, if they had ever been formulated, were soon shelved, perhaps because they proved too difficult to implement, and there turned out to be too many vested interests. A long time ago Zimbabwean education had been decolonised (before Mugabe’s time, and before Smith’s, even). Any attempt to make serious use of better trained Zimbabwean teachers in the South African system, to help transform it, tended to be stymied by South African teachers who had been poorly trained in the colonised Broederbond system, and they threatened to strike if Zimbabwean teachers were employed. Thus colonised education persisted far longer than it should have. Any suggestion that teachers who had been trained in the Broederbond system should be retrained was likewise met by threats to strike.

The purveyors of the Broederbond snake oil called Fundamental Pedagogics retained their places in the education faculties of universities, and went on wreaking their damage, Some of them tried, like the Vicar of Bray, to be politically correct in the new system. One Unisa lecturer, in his zeal for political correctness, revised his study guide by going through it using the search and replace function of a word processor to replace every instance of “fundamental pedagogics” with “philosophy of education”. If it was incomprehensible before, that turned it into word salad, but that didn’t matter, because, as one lecturer said, the students did not have to understand it, they just had to learn it.

So in many ways, looking back, The times that were a-changin’ 50 years ago don’t seem to have changed at all. The youth are saying to their elders, move aside, you don’t understand”. The barricades of burning tyres or burning vehicles and the rubble of broken liitter bins or paving stones seems much the same. Those whose grandparents said “don’t block up the hall are saying the same things themselves. Some of the student protesters compare themselves with the 1976 generation, and the implication is that the 1976 generation has failed them.

So what is different, if anything?

Police confront priest at entrance to church.

The image of a priest confronting an armoured police vehicle may look like a rerun of student protests of the 1970s, and the police who shot protesting miners at Marikana may look very little transformed from those who shot pass-law protesters at Sharpeville 50 years before, but there is an important difference.

The police who acted in those ways 50 years ago represented a burgeoning police state that was deliberately brought into being by Balthazar Johannes Vorster, then Minister of Justice. They could behave with impunity because he gave them impunity. But the laws that gave them impunity have been repealed. Something has changed since then.

And so I find myself in two minds about this. On the one hand, I remember the student protests of my youth, and what we were fighting for, and I think of the critics of student protest back then, and so many critics of student protesters now, who are well described here — Critiquing the critics of youth protest in post millennial South Africa:

The responses from many middle class observers to current student protests reveal a worrying but not unexpected trend symptomatic of contemporary political debate in South Africa. Young people, vocally objecting to the debt they must take on in order to get a tertiary education in post-apartheid South Africa with its high youth unemployment figure and less than inspiring economic growth prospects in the medium term, are subjected to ridicule and hectoring from people who mis-remember the privileges afforded them by the mediocracy which was tax-funded Christian Nationalist Education.

Derisive and sarcastic remarks about the cost of protestors’ clothing, ridiculing them for being involved in protests when they should be studying, and jeering at their supposed ingratitude for finding fault with systematised inequality and not appreciating opportunities given them, are only some of the responses from folks who believe themselves to be entirely reasonable in their criticisms. These responses echo those to the 1976 insurgency from conservative elements in black communities, as well as the dominant responses from apartheid apparatchiks and beneficiaries. With little irony, and seemingly less awareness of assuming the postures of the defenders of inequity and inequality in our recent history, they are quick to denounce contemporary youth political insurgency.

If I criticise student protesters now, will I not be becoming like “them”? Back then there was a slogan, “Don’t trust anyone over 30,” and on my 30th birthday I was very conscious of having reached to age of untrustworthiness, and now it has stretched out to even longer — more than 30 years have passed since I was 30.

And yet, and yet…. for all the corruption and cronyism, we do have a democratic society. It may work better in theory than in practice, but the theory is always there to be appealed to. Before 1994 there could be no such appeal to democracy. There was a small group of oligarchs who told us to stick to our “own affairs” and carried a big stick to make sure we knew what our own affairs were, which they told us. And in some ways the more extreme and violent of the student protesters seem to be reverting to that. They are the new oligarchy, demanding that everyone do what they say. The chickens of Christian National Education are coming home to roost.

The Brazilian educationist, Paolo Freire, said that the oppressed internalises the mind of the oppressor, and comes to believe that in order to be truly human one must become an oppressor. So the Afrikaner victims of British imperialism, who resented the Anglicisation policy of Alfred Lord Milner, stood up for the rights of people to speak and be taught in Afrikaans, but by 1976 their heirts Andries Treurnicht and Ferdi Hatzenberg were seeking to impose Afrikaans on others, just as Milner did to them. And so among the student protesters there seems to be a similar small group, seeking to go back behind our democracy, and resurrect the idea of a Broederbond-like oligarchy, whose will must be obeyed by all.

Part of our democracy is the idea that we can talk and listen to each other, than we can face problems and try to solve them. Part of the problem of pre-1994 South Africa was that that was impossible, because all discussion had to take place within the ideological framework of apartheid, which could not be questioned. Of course some would say that the idea of democracy is itself a bourgeois liberal ideological concept that needs to be overthrown by the will of a small group. But do we really want to go back there?

I think that most would agree that all education, and not just tertiary education, has been chronically under-funded and untransformed, and the #feesmustfall campaign has drawn attention to this, and it needs to be dealt with. But whether it can be dealt with only according to the dictates of a small group who seem bent on destroying educational resources and infrastructure, and do not appear to represent the majority of students, or even of those involved in the #feesmustfall movement is a different matter. It seems to be a regression to Broederbond-style oligarchy.

And then there is the question of transformation in the police. A couple of weeks ago this rather ominous article appeared — EWN – Eyewitness News — SA police need training to deal with protests – lawyer:

As police are accused of using a heavy hand during the #FeesMustFall protests, attorney Andries Nkome says the South Africa Police Services have not learnt anything from the Marikana massacre, adding that officers should be retrained to understand how to quell protests.

Let us be quite clear about this: the police do not need to be trained in how to “quell” protests. It is not the job of the police to quell protests. People have a constitutional right to protest, and it is not the business of the police to interfere with that right. Protesting is not breaking the law. If protesters (or anyone else) start damaging property and assaulting people, then they are breaking the law, and it is the job of the police to arrest and charge them (not to “disperse” them using stun grenades and rubber bullets). And yes, the police may need special training for that — not to “quell” protests, but to see that protests remain peaceful.

We have seen reports that some student protesters thew stones at private security guards, and the private security guards threw stones back. In either case it is assault and breaking the law, and the police should arrest and charge those who do such things, whether students, security guards, or anyone else.

There seems to be a conspiracy of silence about this. There are news reports of students being arrested at violent protests. There are reports of people being arrested for arson of schools in Limpopo province, but there are no reports of what happened when these people are brought to trial. The trials might reveal who they are and what their motives are, but no one seems to want to report on that.

But all in all, the times haven’t changed that much at all.

October 10, 2016

Dostoevsky, a book review

Dostoevsky by Nikolai A. Berdyaev

Dostoevsky by Nikolai A. Berdyaev

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I bought this book nearly 50 years ago, and started reading it several times, but never got further than the first couple of chapters, perhaps because I thought I should be more familiar with Dostoevsky’s own works before reading this one, but perhaps it should be read concurrently.

I’ve made a few other attempts since then, but not until now have I managed to read it all the way through. It’s a mixture of literary criticism, theology and philosophy, and Berdyaev makes a point of comparing Dostoevsky with Tolstoy, usually to the detriment of the latter.

The first part makes the point that Dostoevsky writes from a Christian point of view, with a strong stress on human freedom. There is no hint of predestination here, and Dostoevsky’s theodicy is that evil is found in the world because man has freedom to choose it, and the way to combat evil is through redemptive suffering. Calvinists probably won’t find much to agree with here.

The prime expression of this is in the legend of The Grand Inquisitor as told in The Brothers Karamazov The Grand Inquisitor (who in Berdyaev’s description sounds very like Mustapha Mond in Brave New World) maintains that men are unhappy when free, and it is much better to organise their lives for them. Freedom, of a sort, might be for a small elite.

So far it seems to make a lot of sense, and makes sense of Dostoevsky’s novels — the ones I have read, anyway. There is even a kind of defence of the current slogan #alllivesmatter, which some Americans regard as very politically incorrect.

All things are not allowable because, as immanent experience proves, human nature is created in the image of God and every man has an absolute value in himself and as such. The spiritual nature of man forbids the arbitrary killing of the least and most harmful of men: it means the loss of one’s essential humanity and the dissolution of personality; it is a crime that no “idea” or “higher end” can justify. Our neighbour is more precious than an abstract notion, any human life and person is worth more here and now than some future bettering of society. That is the Christian conception, and it is Dostoievsky’s. Even if be believes himself Napoleon, or a god, the man who infringes the limits of that human nature which is made in the divine likeness falls crashing down: he discovers that he is not a superman but a weak, abject, unreliable creature — as did Raskolnikov.

But there are things that I have more doubts about. Berdyaev regards socialism as necessarily atheistic and anti-Christian, which seems to conflict with what he has written elsewhere, and it is only right at the end that he brings in the qualification that he is referring to socialism as a religion, and not as a social or economic system. It might have helped if the had made that clear from the beginning.

Nowadays we hear quite a bit about American Exceptionalism, and at times in the book Berdyaev seems to be preaching a kind of Russian exceptionalism. He goes off into long strings of abstractions, wittering on about the “Russian mind” and the “Russian soul”. One gathers that the Russian mind is apocalyptic, but it’s never quite clear in what way, though at times the language seems to be over-hyped: “the spiritual warp of Dostoievsky’s disciples was different. Their eyes were turned to an unknown but threatening future, apocalyptic waves broke over them, they were dashed from one extremity to its opposite; above all they were to experience that inner division that the men of the ‘forties did not undergo…”

That sort of prose puts me in mind of videos of tsunamis in Japan and Indonesia.

And then there are such generalisations as this:

The Russian gladly rids himself of all cultural trappings in the hope that in the “state of nature” true being may be revealed to him; of course it is not, because culture is in fact the way that leads to the reality of being: divine life itself is the highest culture of the spirit.

Several different interpretations of this have occurred to me, and I’ve already forgotten some of them. So if anyone is still reading this, I’ll leave you to come up with your own.

October 4, 2016

East is East and West is West

I quite often see articles on the web about the differences between Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox, usually compiled by Roman Catholics.

One of the biggest differences, however, which is rarely mentioned in such lists, is the difference in the lists of differences — in other words, there are different perceptions of what the differences are.

The Roman Catholic lists rarely mention beards, for one thing, which this humorous, but fairly historically accurate account of the split of 1054, does not omit: The Beard-Battle that Almost Split Christendom | The Local Church:

[Cardinal Humbert] excommunicated half of all Christendom—for having beards.

Sort of. See, what happened was this: On July 16, 1054, Humbert interrupted the patriarch in the middle of conducting the divine liturgy to serve him a papal bull of excommunication. The bull in question cited numerous offenses committed by the Eastern Church, including allowing priests to marry (which they didn’t do), re-baptizing Latin Christians (which they also didn’t do), and omitting a clause from the Nicene Creed (which, you’ll recall, had actually been added unilaterally by the Western Church). Oh, and the kicker:

And because they grow the hair on their head and beards, they will not receive in communion those who tonsure their hair and shave their beards following the decreed practice of the Roman Church.

That’s right. Worst of all, those Byzantine Christians grew beards—and, according to the bull, they denied Communion to men who shaved, too. (The Roman Church had banned beards in 1031, only a couple decades before Humbert excommunicated the East for not following suit.)

Go on, read the whole article. It’s funny, but it also gives you a fairly good idea of what actually happened. Take the mentions of “Byzantine” with a pinch of salt — that’s a later anachronism.

But this post is not about 1054 and all that, but rather on the differences in the lists of differences.

Here are three lists of differences:

A Roman Catholic list, from Crux magazine

An Orthodox list, from an Orthodox priest in the USA

A list compiled by The Economist, a secular publication

Check the lists for similarities and differences, but I think you will see that the lists of differences differ as much as, if not more than, the differences themselves.

At this point the diehard ecumenist might object:

Why be so negative? Why focus on differences? Why not concentrate on the things that unite us instead.

The problem with that is that even if we did that, we might end up arguing about the things that unite us, because we tend to approach them from different points of view, as the article in The Economist makes clear. Also, the Roman Catholic Church is bigger than the Orthodox Church, so if there is any reunion scheme that ignores the differences, the Roman Catholics will simply assume that their way is the norm, and that takes us right back to 1054, because that is exactly what happened then, and there’s not much point in just going round in circles and getting back to where we started.

So look at the headings of the two lists:

The Roman Catholic List:

Primacy of the Bishop of Rome

The Filioque

Indissolubility of marriage

Purgatoriy, the Immaculate Conception and other disagreements

The Orthodox list:

Faith and Reason

The development of doctrine

God

Christ

The Church

The Holy Canons

The Mysteries

The nature of man

The Mother of God

Icons

Purgatory

Other differences

See what I mean?

The first three items on the two lists are completely different, and it is only in the 11th item on the Orthodox list that there is any overlap — on Purgatory.

The second item on the Orthodox list, The Development of Doctrine, is explained succinctly in the article in The Economist:

The West developed the idea of purgatory and of “penal substitution” (the idea that Christ’s self-sacrifice was a necessary payoff to a punitive Father-God). Neither teaching appeals to Orthodox Christians. The East, with a penchant for mixing the intellectual and the mystical, explored the idea that God was both inaccessible to human reason but accessible to the human heart.

And that gives a clue to another significant difference.

Most of the Roman Catholic lists deal with things that happened before 1054; most of the Orthodox lists concentrate on things that happened after 1054.

It is also worth noting that the list from The Crux is very diplomatic in its wording. It refers to the primacy of the Bishop- of Rome. Many other Roman Catholic lists refer to “Papal Primacy”.

At this point I shall get anecdotal, and indulge in a bit of narrative theology.

St John Lateran, the Cathedral of the Bishop of Rome

As many readers of this blog probably know, I used to be an Anglican, and back in the 1970s when some Anglicans were disturbed by some theological trends in the Anglican Church and were thinking of leaving, an Anglican priest in Umtata (Mthatha), the Revd Walter Goodall, wrote an article in a publication (I forget which) suggesting that such disaffected Anglicans could find a home in the Roman Catholic Church under the Pope of Rome, “who is, after all, the Patriarch of the West”.

I replied to him, pointing out that we lived in Africa, not in the West, and that Africa was under the jurisdiction of the Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and all Africa.

His Beatitude Theodoros, Pope and Patriarch of Alexandria and all Africa, gives an award to Kirill, Patriarch of Moscow, who was visiting Egypt.

He responded rather sarcastically, asking “haven’t you heard of Universal Ordinary Jurisdiction?” I had to admit that I hadn’t heard of it, but also that I didn’t like the sound of it. I lived in Africa, and if I was going to leave a church that defined itself by communion with a bishop in Canterbury in England, I’d prefer to move to a jurisdiction that had been the focus of African Christianity since the first century than to an Italian one.

The question of “Papal Primacy” therefore raised for me the question of “which Pope?”, but more widely the question of ecclesiology, and especially the kind of ecclesiology implied in the phrase “universal ordinary jurisdiction”.

I’m not anti-Roman Catholic. I’m not one of those hyper-Orthodox who regard the Roman Catholics as “heretics” — I believe you have to be Orthodox before you can be a heretic; you have to be a communicant before you can be excommunicated. I think the current Roman Pope Francis has said some cool things, and that we can certainly talk to each other and maybe do some things together. But I think reunion is a long way off, and we need to take the differences seriously and not just sweep them under the carpet. And even if we do, we need to be aware that we are sweeping them under different corners of the carpet, or perhaps under different carpets altogether.

At one time our parish in Brixton, Johannesburg had a priest seconded from the Orthodox Church in America. A priest from a neighbouring parish once said to me, “You are bigamists! You have two bishops!” And the local bishop explained to him that we were not bigamists, that the American priests were here with the blessing of the Pope in Alexandria and the local bishop. But if we were suddenly to reunite with the Roman Catholic Church, perhaps we really would be bigamists, having two popes, one in Alexandria and one in Rome. And which one would have the primacy then? Perhaps we should say that we’ll cross that bridge when we come to it, but it looks to me that there might be two bridges, and perhaps even two rivers.

We need to look at the differences before we get to that bridge.

October 1, 2016

A South African civil religion?

My colleague and blogging friend Dion Forster has written about a South African civil religion, which he thinks has failed us He writes Why the ‘loss of faith’ in heroes like Mandela may not be such a bad thing:

The birth of the South African post-apartheid civil religion took place on the day of first South African democratic elections. This event was lauded across the world, as a “miracle” of peaceful transition in the midst of a hostile and precarious social and political situation.

Many doomsday prophets had predicted the eruption of a civil war in the lead to up the elections. Instead, post-election media reports reflected a widespread sense of euphoria and joy. It was framed in the dense and symbolic theological and religious language of peace and reconciliation. This is not surprising in a country where over 85% of the population profess to be Christian. Such language is familiar. It has meaning and currency.

He maintains that this narrative and civil religion is now being questioned by the current generation of students, and advocates the substitution of “an ethics of responsibility” for the civil religion.

Another colleague, Cobus van Wyngaard, in responding to this points out that the questioning of the current generation of students is not all that new — my contemplations | a South African conversation on just being church today:

South Africa did indeed have something of a dominent public narrative over much of the past 22 years. I think it did indeed function like a religion, and much of it was actually informed quite consciously by religious convictions. There is a theology behind the rainbow nation! But there has always been a counter narrative. The critique that Dion mentions did not emerge with the student movement, even if the student movement forced the attention of the likes of us (white middle class dominees) onto this critique (but we could have heard it had we listened). That alternative narrative need to be explored. It runs through Black Consciousness, the Pan Africanist Congress, the economic left in the older SACP and unions. For those of us in theology, it runs through Black Theology, Kairos, the CI, certain parts of the ICT.

And he goes on to ask Dion Forster to spell out what he mean by “an ethics of responsibility”.

I’ll add my bit to the conversation by questioning the narrative of a civil religion. I doubt that it took the form or was as all-pervasive as Dion suggests. I think talk of the loss of faith in heroes like Mandela is a bit over the top, because I doubt that that faith was there to begin with.

Yes, there was widespread “euphoria and joy” in the wake of the first democratic elections, but it was not joy that a civil war had been averted, it was joy because the civil war had ended. The civil war had erupted in 1976, against schoolkids in Soweto. And when the flypast of a museum of aviation history took place at Nelson Mandela’s presidential inauguration there was a huge outburst of cheering and applause, because those weapons and symbols of oppression had been neutralised and were on our side now.

Thundering jets — the sound of freedom

If the media painted a picture of euphoria and joy because a civil war had been averted, they got it wrong. They created the spectre of civil war in their scenario because of their philosophy of “if it bleeds it leads” and before the votes had been counted most of them had rushed off to Rwanda, where the hoped-for bleeding was taking place.

There was euphoria and joy because there was real liberation. And yes, it had religious echoes. It put me in mind of the Psalm:

When the Lord turned again the captivity of Zion: then were we like unto them that dream.

The was our mouth filled with laughter: and our tongue with joy.

Anyone who doesn’t think there was a real liberation then is simply in denial about how oppressive the apartheid regime actually was.

There were a very few, like Fr Albert Nolan, OP, who hailed this moment of liberation as the end of history. Other revolutions of the past had subsided into oppression, but this one, he believed, would not. So for him, it was an “and they all lived happily ever after” fairy-tale ending. That may have been the beginning of a civil religion, but I doubt whether it had many followers.

Yes, Nelson Mandela became a symbolic figure. For the next few years, whenever he appeared at a sporting fixture, the South African team won, starting on the day of his inauguration.

But he often pointed out that he himself was a disciplined member of a disciplined political organisation. He did not make decisions, the decisions were made by the ANC, and though his voice was influential within the ANC, it was not by any means the only one, or even the dominant one.

And now, more than twenty years later, during election campaigns, the ANC does sometimes appeal to a kind of civil religion, the “we have a good story to tell” narrative. The problem is that most of the things in the “good story” happened 15 years ago or more, and most of the people who did them are dead. Many communities gained access to clean water for the first time under the ANC government, thanks to people like Kader Asmal. And yes, I agree with Dion Forster that we should not put our faith in heroes like Kader Asmal, any more than we should in Nelson Mandela. And if an “ethic of responsibility” means that we should do what he did, I’m all for it.

But why did they do the things they did, and why do we no longer find people who do the things they did?

Why are many people who have been active in the ANC now sad and disillusioned, and look back nostalgically to the era of Mandela, Tambo, Sisulu, Hani and others? Was it because they had “put their faith in them” as some kind civil religion?

I doubt it. They were all fallible human beings. They made good decisions and bad decisions. They were part of an organisations that made good decisions and bad decisions. And if you want an ethic of responsibility, then we have to acknowledge that some of the bad decisions led us to where we are now.

Part of the problem is power.

When the ANC was out of power, when it was the opposition, it could dream of the kind of society it wanted and put in place of the existing one. It could come up with plans for transformation. And there were people who gave thought to this, for example to how they wanted education transformed (since we are dealing with demands of students). What system would they like to put in place of Bantu Education, Christian National Education, inequality in education, Broederbond-controlled universities, and all the rest? How would these changes be brought about, and how would they be funded? There were some people, like John Samuel, who gave a lot of thought to this. But after the ANC came to power, people like John Samuel were sidelined, things muddled along they way they always had been with the difference that a whole lot of teacher training colleges were closed — yet that was exactly where transformation in education needed to begin. The result was a lot of ad hoc decisions to deal with crises as they arose, and a lot of old vested interests that needed to be balanced with some new vested interests in the hope that things could move along somehow, with education chronically underfunded and no real plan. Twenty lost years.

Before coming to power, the ANC could dream of changes and improvements they could make if they came to power, but once in power they could only dream of power itself, and keeping power, and instead of planning policies for education. Instead of planning strategies for education, most of the energy is now put into planning strategies to deal with rivals in power struggles.

As Lord Acton said, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men.”

So much for putting one’s faith in heroes.

And the longer men are in power, the more corrupt they tend to be.

So perhaps what middle-class theologians, or, better still, theologians 9f all classes, need to think more about is the theology of power, and especially possession of power. What is the difference between possessing power and being possessed by it? And how can human beings handle power without becoming enthralled by it? And how do we exorcise people and organisations once they have been possessed by power?

September 24, 2016

Appropriate and inappropriate cultural appropriation

I only learned about the term “cultural appropriation” about seven years ago, and blogged about it here: Inculturation, indigenisation, syncretism and cultural appropriation. But though the term itself was new to me then, the thing it described was not. Fifty years ago I wrote about how disconcerted I was (well, more like disgusted) to encounter English Anglicans who spoke of “Orthodox Spirituality” in hushed and reverent tones, yet looked down condescendingly on other aspects of Orthodoxy as the amusing antics of quaint foreigners.

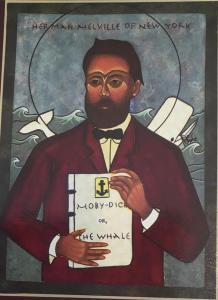

Literary figures rendered in Byzantine icon style — cultural appropriation? Appropriate or inappropriate?

One of the ways in which postmodernity differs from modernity is that it is more tolerant of tradition, and indeed different traditions. Modernity tends to be intolerant of tradition, or at least all traditions other than its own. Moderns often express amazement that “anyone could believe that in 2016”, a kind of temporal chauvinism that assumes that anything anyone believed before the Enlightenment must be false. Postmodernity is much more tolerant, and adopts an indulgent attitude towards cultures of other times and places. The problem is that it also tends to encourage an eclectic and rather superficial borrowing from other cultures, in a way that trivialises them. Here is a recent example: See Literary Figures Rendered in Byzantine Icon Style, which is not very dissimilar from the “spirituality” one of 50 years ago.

On the other hand, I li8ve in a multicultural society. For many years our rulers tried to deny this. They concocted the policy of apartheid (aka separate development) to keep different cultures separate. There was little danger of cultural appropriation, except among those who wanted to buck the system, and those tended to be suppressed. American jazz, for example fused with urban African culture in the shebeens of Sophiatown, but the government brought in bulldozers to put an end to that.

The government insisted on “own”. “Own” affairs, “own” culture, “own” people, “own” land. So they tried very hard to stop cultures influencing each other, and their policies tended to assume that cultures were static. In “separate development” the emphasis was on the “separate” rather than on the “development”.

There are still some people who would like to go back to the old days. They regard multiculturalism as a Bad Thing, and say that things were so much better when we had apartheid.

Things seem to have played out somewhat differently in North America, where, according to my blogging friend Jonathan Allen, it seems that the concept of cultural appropriation has itself become trivialised. He recently wrote on Facebook:

Culture is, and always will be, wrapped up in unequal and unstable dynamics of power. The hijab that the offended author, Yassmin Abdel-Magied, wears is a case in point: to simplify greatly, it originated through the appropriation by victorious and newly dominant Arab Islamic polities of elite Byzantine practices of veiling women, refracted through the emergent legal and religious norms of Islam, itself formed through appropriative acts, from the recycling of Jewish popular traditions, to the destruction of Coptic Orthodox churches in order to acquire spolia for early mosques. But of course the history and meaning of a cultural artifact like the hijab doesn’t stop there, and cannot be reduced to a story of cultural appropriation, or patriarchal dominance, or religious piety, or postcolonial assertions of feminism. It is all of those, and, perhaps, none of them, depending on the context, the people involved, and the meanings that emerge out of that matrix. Neither Abdel Magied nor anyone else is to blame for all of the matrices of appropriation, power, privilege, and so on we are all entangled in- which is why I don’t think charges of ‘hypocrisy’ are very helpful here or in most cases. Everything we do is, in some way, political, and is connected to multiple dynamics of power, privilege, and production, in ways that cannot be reduced to easy moral answers, or to moral answers at all even (though we shouldn’t then simply ignore potential moral questions). Many of the attempts to police identity, even if borne out of praiseworthy sentiments initially, tend to ignore or erase this dynamism, and instead become practices of merely securing political and cultural power over others- even if that is not the intention of the actors involved.

He links to this article, Will the Left Survive the Millennials?, according to which it seems that some are demanding that fiction writers write only about people of their own culture, and that if they write about people of other cultures they are guilty of cultural appropriation. That view is ascribed to the “left”, though it sounds like Dr Verwoerd’s most happy dreams. I think that only goes to show that terms like “left” and “right” in politics have long been meaningless.

And all that leads me to think that it is time to revive the somewhat outmoded concept of a synchroblog, and for a group of people to blog on the same day about appropriate and inappropriate forms of cultural appropriation, and where the difference lies. I think George Tinker’s article, cited in my earlier blog post, might be a good starting point. It’s a good question for missiologists. Any takers?