Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 42

February 1, 2016

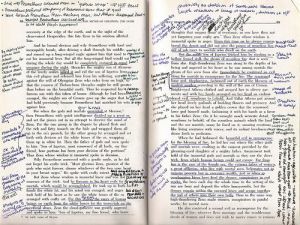

Why you shouldn’t (usually) write in books

Someone posted a link to this article on Facebook, and I strongly disagree Five reasons you should write in your books | Joel J. Miller:

Some will be scandalized. I’m an inveterate scribbler. That’s especially true when it comes to nonfiction, but even novels suffer a few slashes and asterisks. If writing in books ever becomes illegal, you’ll find me in the prison library, lurking in a corner, sharpening a smuggled pencil.

The author is mainly talking about writing in his own books, and since he owns them, that’s OK, but I find it excessively annoying when people write in library books. Finding a book where someone else has underlined things usually distracts from what the author is saying, and very often you don’t know whether the underliner was marking passages they agreed with or disagreed with.

And even if it is my own book, I don’t generally underline things or highlight them, because if it is a good book, on a second reading something quite different might stand out for me, which I might have missed on a first reading. If I have underlined things, then I’m more likely to miss anything new.

And even if it is my own book, I don’t generally underline things or highlight them, because if it is a good book, on a second reading something quite different might stand out for me, which I might have missed on a first reading. If I have underlined things, then I’m more likely to miss anything new.

The author of the article also mentions indexing noteworthy passages in books, and I have less objection to that. Most books have several blank leaves at the end where this can be done. That can be a useful tool and does not distract other readers, and can be useful to them if they are looking for the same things.

Another exception I might be willing to make is where the book has factually incorrect information, for example a date or the name of a person or a place. But this should be rare, and should be reserved strictly for matters of fact rather than matters of opinion. Who was responsible for starting a war is a matter of opinion, but the date of a significant battle in that war is usually a matter of fact.

I have found that most of the things that Joel Miller finds useful about writing in books can be accomplished more easily and more efficiently by computer software.

There are several note-taking programs available, and one that I use for notes and quotes from books is askSam.

Using such a program it is easy to enter notes and quotes from books, with comments as well, and then to search for themes across several books. So, for example, if I want to find something that I read about myth and concepts, I can enter those two words as search terms, and it throws up this:

The nature of myth.

Source: Berdyaev 1948:70.

Myth is a reality immeasurably greater than concept. It is

high time that we stopped identifying myth with invention,

with the illusions of primitive mentality, and with anything,

in fact, which is essentially opposed to reality… The

creation of myths among peoples denotes a real spiritual life,

more real indeed than that of abstract concepts and rational

thought. Myth is always concrete and expresses life better

than abstract thought can do; its nature is bound up with that

of symbol. Myth is the concrete recital of events and original

phenomena of the spiritual life symbolized in the natural

world, which has engraved itself on the language memory and

creative energy of the people… it brings two worlds together

symbolically.

Even if I’d underlined the passage in the book it would not have helped, because it was a library book, and even if I had the time to travel to the library, I might find that someone else had taken the book out.

So for annotating and indexing stuff that you find in books, there are now much better ways. Let your computer do the work. You can read about askSam and similar notetaking programs here or here.

January 28, 2016

Books etcetra

John de Gruchy writes in his blog:

For those who have enquired about my books and publication, or are interested in them, may I draw your attention to the following:Being Human: Confessions of a Christian Humanist (2006). In this I set out my understanding of what it means to be a Christian today over against fundamentalism and secularism.Led into Mystery: Faith Seeking answers in life and death (2013). I wrote this in response to the tragic death of my son Steve.A Theological Odyssey: My life in writing (2014) This was published in celebration of my 75th birthday. It gives full details of all my publications (books, essays, articles), and something about how and why they were written.Sawdust and Soul: Conversations about Woodworking and Spirituality (2015) With William J. Everett. Together with my friend American fellow theologian and woodworker, Bill Everett, I explored what woodworking has taught us about life.I have Come a Long Way (2015). This is an autobiography.

Source: Books etcetra

And John de Gruchy and I are working on another book we hope to publish later this year, one the history of the charismatic renewal and related movements in South Africah church history. Click here for more details.

January 24, 2016

Readers services and ikon stands in Atteridgeville

A couple of weeks ago we restarted Orthodox services in Atteridgeville, about 15 km west of Pretoria.

The parish was started by Fr Nazarios and Fr Elias, two missionary monks, and services were held in a children’s home, or the congregation was transported to the monastery in Gerardville. In 2009 we had a teaching week, which was quite well attended, and the parish seemed to be growing, but after the death of Fr Nazarius and the closure of the children’s home, there was nowhere for the church to meet, so it stopped meeting, yet there were two people who were able to lead Readers Services: Demetrius Mahwayi and Artemius Mangena.

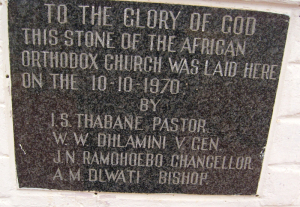

With the blessing of our bishop, Metropolitan Damaskinsos, we arranged with the African Orthodox Church in Atteridgeville to use their church for services, and began a fortnight ago, on 7 January 2016.

African Orthodox Church in Atteridgeville

My wife Val bought some wood, and made two ikon stands (analogia) and hangings, and mounted prints of ikons of our Lord Jesus Christ and the Theotokos (painted by our daughter Julia Bridget Hayes) on boards, and this Sunday we set them up in the church. Fr Frumentius Taubata joined us this Sunday, and so he was able to bless the ikons and ikon stands.

Atteridgeville congregation after the blessing of the ikons and ikon stands

We were joined by some of the members of the African Orthodox Church congregation, including their deacon, the Revd Enock Thobela. Even though we did have a priest with us this time, we still used the Reader Service, because it will take some planning and preparation before we are able to serve the Divine Liturgy there.

Fr Frumentius Taubata preaching at Atteridgebille

The African Orthodox Church began in South Africa in 1924, and its l;eader, Daniel William Alexander of Kimberley, went to America to be consecrated bishop in the African Orthodox Church there, the seme year that the first Orthodox bishop of the Patriarchate of Alexandria was established in Johannesburg.

Foundation nstone of the Atteridgeville church.

Daniel William Alexander went to Uganda in 1932 and Kenya in 1934, and established Afrikan Orthodox Churches there, which were received into the Patriarchate of Alexandria in 1946. You can read more of that history here. The South African branch of the AOC, however, remained independent, and after 1960 split into several separate groups, with a long and complex history.

For the last 20 years I think my main ministry in the church has been teaching leaders of mission congregations to lead reader services in the absence of a priest. This might seem odd to many Orthodox Christiasns, who, if there isn’t a priest, either go to a service in another parish, or stay away from church altogether. I think the importance and rationale of the Reader Services is best explained in the following description by a bishop in America. If you manage to read to the end of it, you will also find a link to where you can download a Reader Service book in pdf format, which you can read and use as the bishop suggests (with the blessing of your own parish priest and/or bishop, of course).

Comments on Reader Services by Archbishop Averky

(An excerpt from The Typicon of the Orthodox Church’s Divine Services: The Orthodox Christian and the Church Situation Toda.)

Archbishop Averky of Holy Trinity Monastery at Jordanville, New York, makes some remarks in a report concerning the “Internal Mission” of the Church which was approved by the whole Council of Bishops of the Russian Church Outside of Russia in 1962:

“It is extremely important for the success of the Internal Mission to attract, as far as possible, all the faithful into one or another kind of active participation in the Divine services, so that they might not feel themselves merely idle spectators or auditors who come to Church as to a theater just in order to hear the beautiful singing of the choir which performs, as often happens now, totally unchurchly, bravura, theatrical compositions. It is absolutely necessary to re-establish the ancient custom, which is indeed demanded by the Typicon itself, of the singing of the whole people at Divine services… It is a shame to the Orthodox faithful not to know its own wondrous, incomparable Orthodox Divine services, and therefore it is the duty of the pastor to make his flock acquainted with the Divine services, which may be accomplished most easily of all by way of attracting the faithful into practical participation.”

Further, in the same article Archbishop Averky dispels the popular misconception that Orthodox Christians are not allowed to perform any church services without a priest, and that therefore the believing people become quite helpless and are unable to pray when they find themselves without a priest. He writes, on the same page of this article:

“According to our Typicon, all the Divine services of the daily cycle — apart, needless to say, from the Divine Liturgy and other Church sacraments — may be performed also by persons not ordained to priestly rank. This has been widely done in the practice of prayer by all monasteries, sketes, and desert-dwellers in whose midst there are no monks clothed in the rank of priest. And up until the most recent time this was to be seen also, for example, in Carpatho-Russia, which was outstanding for the high level of piety of its people, where in case of the illness or absence of the priest, the faithful themselves, without a priest, read and sang the Nocturnes, and Matins, and the Hours, and Vespers, and Compline, and in place of the Divine Liturgy, the Typica.

“In no way can one find anything whatever reprehensible in this, for the texts themselves of our Divine services have foreseen such a possibility, for example, in such a rubric which is often encountered in them: ‘If a priest is present, he says: Blessed is our God… If not, then say with feeling: By the prayers of our Holy Fathers, Lord Jesus Christ our God, have mercy on us. Amen.’ And further there follows the whole order of the Divine services in its entirety, except of course, for the ectenes and the priestly responses. The longer extenes are replaced by the reading of ‘Lord, have mercy’ twelve times, and Little Ectene by the reading of ‘Lord, have mercy’ three times.

“Public prayer, as none other, firmly unites the faithful. And so, in all those parishes where there is no permanent priest, it is absolutely necessary not merely to permit, but indeed to recommend to the faithful that they come together on Sundays and feast days in church or even in homes, where there is no church, in order to perform together such public prayer according to the established order of Divine services.”

This normal church practice, which like so much else that belongs to the best Orthodox Church tradition, has become so rare today as to seem rather a novelty, is nonetheless being practiced now in several parishes of the Russian Church Outside of Russia, as well as in some private homes. This practice can and should be greatly increased among the faithful, whether it is a question of a parish that has lost its priest or is to small to support one, of a small group of believers far from the nearest church which has not yet formed a parish, or a single family which is unable to attend church on every Sunday and feast day.

Indeed, this practice in many places has become the only answer to the problem of keeping alive the tradition of the Church’s Divine services….

The way of conducting such services should preferably be learned from those who already practice it in accordance with both the written and oral tradition of the Church. But even in the absence of such guidance, an Orthodox layman, when he is unable to attend church services, can derive much benefit from simply reading through some of the simpler services, much as he already reads Morning and Evening Prayers. Thus, he can read any of the Hours (First, Third, and Sixth Hours in the morning, Ninth Hour in the afternoon), which have no changeable parts except for the Troparion and Kontakion; he can simply read through the stichera of the great feasts on the appropriate day; or he can read the Psalms appointed for a given day….

From Orthodox Word, Jan.-Feb., 1974, Reprinted in A Manual of The Orthodox Church’s Divine Services, compiled by Archpriest D. Sokolof, Holy Trinity Monastery, Jordanville, NY, 1975.

Click here to download a .pdf file of the text of the Readers Service, in English and North Sotho.

And if you would like to hear what it sounds like, click here to download an MP3 file of of the Typika/Obednitsa sung in North Sotho and English. No, it’s not s super polished choir, just our Mission congregation at Mamelodi meeting in a school classroom.

January 17, 2016

Do Muslims, Jews and Christians worship the same God?

There has been quite a lot of comment on social media recently about the decision of Wheaton College, in the USA, to sack a professor because she said that Christians and Muslims worship the same God.

I refrained from commenting on this for a while because most of the reports I had seen were in secular media that do not understand theological issues, so it was not clear what it was actually about. It did concern me, though, because Wheaton College is the repository of much of the archives of C.S. Lewis, who was one of the twentieth-century Christian writers who said some of the most interesting and thought-provoking things about Christianity and contemporary culture.

Now, however three articles have appeared, which throw some light on the issue, or at least show why it is an issue.

Confronting the Tashlans of Our Time: Wheaton College, Miroslav Volf and the Name of Allah | Finding Tangle

Wheaton and the Controversy Over Whether Muslims and Christians Worship the Same God | Robert Priest, Mark Naylor, and Dale Wolyniak – Academia.edu

What Arab Christians Think of Wheaton-Hawkins ‘Same God’ Debate | Christianity Today

These articles all emanate from Evangelical Christian sources (which happens to be the same theological tradition that Wheaton College belongs to). and in different ways they present the theological question: Do Christians and Muslims worship the same God?

Muslims and Christians claim to worship the God of Abraham, as do Jews, so these three religions are sometimes called Abrahamic. So the question really boils down to whether the God of Abraham is the same God. Christians believe that the God of Abraham is also the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, and that Jesus Christ is himself the God of Abraham.

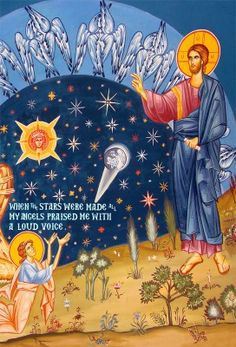

Ikon painted by Bridget Hayes — Ikonographics

On one Internet discussion forum for Orthodox Christians a Muslim posted the question “Who is Allah?” to which I responded that Allah is Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Of course the Muslim disagreed, and no doubt Jews would disagree too.

I’m not a great theological fundi, but it seems to me that if people make an issue out of saying that Christians and Muslims do not worship the same God, and insist that it is important to insist that they do not, they then turn God into a purely human construct, and thus deny that God exists at all.

If God exists at all, he is bigger than human constructs, and while one can say that Christians and Muslims have differing conceptions of God, different theologies, to insist that God is entirely determined by those human constructs is to deny God altogether.

As an Orthodox bishop has pointed out:

In Orthodox patristic theology it is clear that the mystery of the Holy Trinity is one thing, which we will never understand, and the doctrine of the mystery of the Holy Trinity, which the Fathers expressed after having experienced Revelation, is another thing.

St John of Damascus (who lived in Damascus while it was under Islamic rule, and was therefore familiar with Islam) described Islamic theology as a heresy that mutilated God. But he never suggests that Muslims worshipped a different God. Their theology was different, certainly. But to say that there are different Gods is to confuse human theology with the divine essence, which is idolatry. It confuses the map with the territory. If you have two maps, an accurate and an inaccurate one, you do not have a different territory, you just have an inaccurate map.

The article on Confronting the Tashlans of our time raises more and somewhat different problems.

The author goes beyond the question of Muslims and Christians, and makes a distinction between God and Allah. This is pure linquistic chauvinism, which I have dealt with in another article, so I won’t say any more about it here.

But the article also identifies C.S. Lewis’s literary creation Tash with Allah, which is a problem in several ways. While the author acknowledges that Tash is a creature (“Tash, in the story, did turn out to be real. He was not just some idea to be manipulated but a distinct and evil creature who did not care for his followers and was destined to be vanquished by the might of Aslan’s roar”), I believe that both Christians and Muslims regard Allah (God) as the uncreated creator, and therefore not a creature.

In doing this the author seems to make the very error he is trying to avoid — creating a Tashlan, a mingling of the uncreated with the created, which is therefore exactly the kind of parody of the incarnation that C.S. Lewis was trying to portray in his book The Last Battle.

It seems to me that Tash is much closer to Satan in Christian thought — a creature, not the creator. Tash has no power to create, he can only twist and distort the good creation of Aslan. His followers are not like Muslims, but more akin to Satanists. The Calormene culture in the novels may bear some superficial resemblances to medieval Saracens, but the cult of Tash is completely different from Islam.

C.S. Lewis populated his fiction with numerous divine and semi-divine beings, fauns and dryads, Bacchus and Silenus, a river god, planetary rulers and more. But he is always careful to maintain the distinction between creator and created.

Muslims, Christians, and I believe Jews as well maintain this distinction. Muslims go on to say that God neither begets nor is begotten, which Christians do not accept. But that does mean that there are two (or three) uncreated creators, one who begets and is begotten while the other does not. There is one God who is the uncreated creator, worshipped by Christians, Muslims and Jews, even if their conceptions of him differ.

But, as I said, I’m not a theological fundi. If someone can show me that this is heretical, I’m open to being convinced.

يارب يسوع المسيح ابن اللّه الحيّ إرحمني أنا الخاطئ

Easter, Wester, which is bester?

After the Anglican Primates meeting last week, which, from what I’ve heard narrowly managed to avert the disintegration of the Anglican Communion, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, announced that he was working towards having a fixed date for Easter. Archbishop Justin Welby hopes for fixed Easter date – BBC News:

The Archbishop of Canterbury is working with other Christian churches to agree on a fixed date for Easter.

Justin Welby made the announcement after a meeting of primates from the Anglican Communion in Canterbury.

In the UK, an act of Parliament passed in 1928 allowed for Easter Sunday to be fixed on the first Sunday after the second Saturday in April.

However, this has never been activated and Easter has remained variable, determined by the moon’s cycle.

Coming just after a meeting at which different views on sexual morality and the theology of marriage threatened to tear the Anglican Communion apart, I can’t help wondering whether this Easter business is perhaps a diversionary tactic to shift the media spotlight to the Orthodox, for whom the calendar is as much a contentious issue as sexual morality is for Anglicans.

One interesting response came from a Pagan friend, who said on Facebook, “If they are talking about divorcing Easter from its connection to the Full Moon, I’m going to be very cross indeed.”

My somewhat jocular response to that was that if Eastern and Wester were always on the same date, the Orthodox would not be able to invite their Western friends to Holy Week and Easter services, because they would be busy with their own, and also the Orthodox would be deprived of the opportunity of buying chocolate Easter eggs in the shops at a discount rate. Not so much this year, when Easter and Wester are five weeks apart (1 May & 27 March) and the chocolate eggs will be well out of the shops by the time Easter arrives.

But it was the connection with the full moon that I find interesting. I don’t have any very profound thoughts on this, and no doubt all kinds of people could pick holes in this, but I thought it is interesting to compare Christian and Pagan notions of the full moon and other astronomical phenomena.

In one of the biblical accounts of creation, Genesis chapter 1, the creation of the sun and moon are describes as follows:

In one of the biblical accounts of creation, Genesis chapter 1, the creation of the sun and moon are describes as follows:

And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also.

And God set them in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth,

And to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness: and God saw that it was good.

And the evening and the morning were the fourth day (Genesis 1-16-19).

There are several interesting things here. One is that the light-bearing bodies are created after light, and even after day and night. They are to mark the distinction between day and night, but do not make the distinction.

Another thing is that the light-bearing bodies are not named. They are not called the sun and moon, but simply the big light and the little light.

This is not an accident, but it is making a deliberate theological point. The people of Israel were aware that many of the surrounding nations worshipped the sun and the moon, or the deities believed to control them, but the covenant God had made with them told them that they were not to do such things. So the creation of the sun and moon is described in such a way as to show that the heavenly bodies are not to be worshipped. They are creatures, created by God, and their purpose is not to be worshipped, but to provide illumination and regulate the calendar.

So the Christian take on it is somewhat different from the pagan take on it, and even the neopagan take on it.

But where we can agree is that they are there to regulate the calendar, and if God saw that it was good, then it is good that they should go on regulating the calendar.

There are other biblical accounts of creation that show it in a somewhat different light, and perhaps they resonate better with what pagans feel about such things. For example this one, when the Lord questions Job, who has been questioning him about everything that has happened:

Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? declare, if thou hast understanding.

Who hath laid the measures thereof, if thou knowest? or who hath stretched the line upon it?

Whereupon are the foundations thereof fastened? or who laid the corner stone thereof;

When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy? (Job 38:4-7)

And it is this view that was taken up by C.S. Lewis in his book The magician’s nephew, when he describes the creation of Narnia accompanied by singing stars, and his friend and fellow-author J.R/R. Tolkien did something similar in the Ainulindalë. Lewis went even further along that line when, in his novel That hideous strength, he gives the planets and their divine rulers their old Roman pagan names and characteristic behaviour, though he also refers to them by their names in his made-up language, Old Solar.

Lewis comes closest to explaining this in yet another novel, The voyage of the Dawn Treader, where two children from our world travel to Narnia and meet a retired star. One of them, Eustace Scrubb, who has had an entirely modern education, says “In our world stars are great balls of burning gas,” to which the retired star replies, “Even in your world, that is only what they are made of, and not what they are.”

And it seems to me that the proposal to fix the date of Easter comes out of the kind of worldview that Eustace Scrubb was educated in. It smacks of Enlightenment thinking, the same kind of thinking that produced the metric system. Of course generations of school children can be thankful that the metric system has made school mathematics easier. But when it was adopted in South Africa 45 years ago, one of the first effects was a rise in building costs. That was because metric bricks were smaller, and so they took 14% longer for a bricklayer to lay them. The metric system is easier to calculate, but a lot of its measurements are not on a human scale.

And is the world really dying for a fixed date of Easter? Wouldn’t it be better to put our time and effort and energy into sorting out things like the civil wars in Syria and Ukraine and Burundi and other countries, beside which the messy dates of Easter and even Anglican squabbles about sexual morality pale into insignificance?

January 15, 2016

English | free richard-spiros!

Richard-Spyros Hagabimana, a Colonel from Burundi, who is also a Greek citizen and a faithful Orthodox Christian, has been cruelly tortured and illegally held in various prisons in Burundi since June 2015, and is to be tried on December the 14th 2015, under the false accusation of participating in the attempted coup of May 2015. In fact he is jailed and tortured for refusing to use violence to repress -and even to kill- protesting demonstrators, mostly women and children.

Source: English | free richard-spiros!

Apparently he has now been found innocent and freed. but I hope the full story can be told.

January 11, 2016

Go set a Watchman

The work is definitely worth reading, and I gave the book to my sister as a Christmas gift. She is a great admirer of To Kill a Mockingbird and I think this book will resonate with her.

Source: Go set a Watchman

I hadn’t planned to read this, but after reading this review I might.

January 10, 2016

Children’s literature: fantasy or moral realism?

I’ve seen a couple of interesting articles on children’s literature recently, comparing British and American styles of writing.

If Harry Potter and Huckleberry Finn were each to represent British versus American children’s literature, a curious dynamic would emerge: In a literary duel for the hearts and minds of children, one is a wizard-in-training at a boarding school in the Scottish Highlands, while the other is a barefoot boy drifting down the Mississippi, beset by con artists, slave hunters, and thieves. One defeats evil with a wand, the other takes to a raft to right a social wrong. Both orphans took over the world of English-language children’s literature, but their stories unfold in noticeably different ways.

An interesting thesis, and I was wondering about it when an American scholar of the Inklings (some of whom wrote some of the best-known British children’s fantasy stories) posted a tweet on Twitter, asking “which fairy story traumatised you most as a child?”

And I couldn’t think of any fairy stories that had traumatised me at all. I could think of a children’s story that traumatised me as a child, and it was one of the American moral realism school. My cousins had a copy of this book: Uncle Arthur’s Bedtime Stories Volume One by Arthur S. Maxwell

Uncle Arthur’s Bedtime Stories Volume One by Arthur S. Maxwell

My rating: 1 of 5 stars

It was moralistic and scary. The story that traumatised me most, so that I still remember it, was one about a boy who liked to throw stones, and he threw one at a girl called Doris, and hit her on the voice box so she could no longer speak. It gave me nightmares for weeks.

I later developed a taste for horror stories, and I’m in the middle of reading a collection of horror stories at bed time, but none of them has ever horrified me as much as Uncle Arthur’s bedtime stories. I later discovered that the book had been published by Seventh-Day Adventists, and Seventh-Day Adventism is a “made in the USA” variety of Protestantism that is more moralistic than most.

Uncle Arthur’s bedtime stories is perhaps an extreme example of the moralism that pervades much American children’s literature, but I think Colleen Gillard in her article in The Atlantic misses the mark in many ways. She makes no mention of Madeleine l’Engle, for example.

And one of the pull quotes in Gillard’s article gets it exactly wrong:

Popular storytelling in the New World instead tended to celebrate in words and song the larger-than-life exploits of ordinary men and women.

But the best fantasy and fairy stories are not about extraordinary people, they are about extraordinary things happening to ordinary people. Jack the Giantkiller is an ordinary boy who climbs an extraordinary beanstalk. The children in the Narnia stories are ordinary schoolchildren who encounter an extraordinary world. In The Lord of the Rings Tolkien emphasises the ordinariness of hobbits, some of whom have quite extraordinary adventures. Harry Potter is a wizard, which makes him extraordinary among muggles, but in most of the stories he is a wizard among other wizards, where being a wizard is not extraordinary. And at the centre of the Harry Potter stories are moral choices where Christian values predominate, contrary to what Gillard asserts.

Gillard goes on to say that British children’s stories are better than American ones because of the pagan roots of British fantasy. I think that is adequately refuted in this article Catholic or Pagan Imagination: A Response to Colleen Gillard — Letters from the Edge of Elfland, and the author’s reaction to Gillard’s article is similar to mine:

Things were going along fine at first. The first line of the article, a kind of one sentence summation of the article in toto, says, “Their history informs fantastical myths and legends, while American tales tends to focus on moral realism.” Gillard goes on to provide evidence for this by first contrasting Huckleberry Fin to the Harry Potter stories. As Gillard writes, “One defeats evil with a wand, the other takes to a raft to right a social wrong.” American children stories especially from the nineteenth century onward tend to focus on life in the frontier and usually have a strong moral ethic to them that involves working hard, or being cunning enough to get others to work hard for you, sticking to your guns against an immoral society or an amoral nature. Gillard, citing Harvard professor Maria Tatar, connects the American side to the Protestant work ethic. Again, I find myself agreeing. Yet it is when Tatar suggests that it’s simply that, “the British have always been in touch with their pagan folklore…. After all, the country’s very origin story is about a young king tutored by a wizard.” Now Gillard, and Tatar, is going a bit awry if you ask me. First of all, King Arthur, while an essential story within British culture, is not exactly the country’s origin story. That’s not quite the role it’s meant to fill. But putting that aside, Merlin being a wizard and Arthur’s tutor (which sounds much more like Gillard is getting her Arthurian legend through T. H. White rather than, say, Chretien de Troyes or the Gawain Poet or many, many others) doesn’t make those stories pagan.

I think there as more than can be said about this. The Arthurian stories are set in Romanised Britain just after the Roman invaders had left and when the Anglo-Saxon invaders are beginning to arrive. But they were popularised in Britain at the time that the Norman invaders had established their power over the Anglo-Saxon invaders of the post-Arthurian period. The people at the centre of the Arthurian stories are neither Norman nor Anglo-Saxon, so it is certainly not their origins that are being portrayed. And I find it interesting that the legend of the Holy Grail is being developed just about the time that the Roman Catholic doctrine of transsubstantiation was being defined. The Arthurian stories are not really pagan, and nor are they children’s stories.

Gillard also does not mention the British author whose children’s stories are most pagan in background, namely Alan Garner. If any children’s book comes close to supporting Gillard’s thesis about paganism in children’s literature The Weirdstone of Brisingamen would.

But the appeal of Garner’s works is similar to that of the more demonstrably Christian-based ones like those of C.S. Lewis, Tolkien et al. I think David Mosley comes closer to the mark when he contrasts the Catholic background of British culture with the influence of the Protestant work ethic on the dominant American culture.

But I think there is even more to it than that. The USA was founded in modernity, the values of which were shapped by movements such as the Renaissance, the Reformation and the Enlightenment. These shaped the kind opf Christianity that took root in America, and the kind of values portrayed in much American children’s literature.

British authors like Tolkien and Lewis portray, or at least value, a premodern worldview. In the Harry Potter books there is something similar. The Muggles are thoroughly modern, mired in modernity. But there is something premodern about the wizarding world, even though there is much that is also modern about the students at Hogwarts.

Modernity has little time for the premodern world and worldview. Christian missionaries who came to Africa from Western Europe and America in the 19th century battled to understand the premodern African culture they encountered and many of them concluded that Africans must be “civilized” (ie “modernised”) before they could be Christianised. Compare also the Orthodox missionaries in 19th-century Alaska witrh their Protestant counterparts. The Orthodox missionaries attributed some of the visions of the Alaskan shamans to the Holy Spirit, the Protestant missionaries attributed them to primitive superstition or the devil.

What I think Gillard fails to understand is that premodern Christians and premodern pagans inhabited the same universe. They experienced the same problems in the same way and within the same cultural framework, and very often the same assumptions about the world. They may have differed about the solutions, but they faced the same problems.

Gillard seems to regard Christians in the premodern world as modern Americans in medieval dress — which is precisely what the Seventh-Day Adventist authors of books like Uncle Arthur’s bedtime stories do. Seventh-Day Adventist illustrated books on the Bible show Americans from 1947 wearing dressing gowns wandering around the ancient Near East. That is perhaps the biggest fantasy of all.

If anyone would like to follow the theme further, see my article on Christianity, Paganism and Literature.

January 9, 2016

Isn’t genocide sexy enough?

Someone posted a link on Facebook to an article that I think deserves closer examination, because I think it reveals a lot about clashing cultures and clashing civilizations: The Anglican schism over sexuality marks the end of a global church | Andrew Brown | Opinion | The Guardian:

As 38 leaders from Anglican churches around the world prepare to meet in Canterbury next week to decide whether they can bear to go on talking to one another, or whether to formalise their schism over sexuality, it’s worth asking whether they have any larger message for the world. Apparently they do. It’s that genocide is more biblical than sodomy. The hardline African churches preparing to walk out of next week’s meeting are disproportionately involved in wars and in immense civilian suffering. In northern Nigeria and northern Kenya, the fighting is with Islamist militias; in South Sudan and Congo the truly dreadful civil war is fought between largely Christian ethnic groupings. In Rwanda, the war is over, but the genocide was committed by Christians against other Christians, and Uganda, while itself at peace, is involved in both Rwanda and Congo.

The article raises many issues and many questions, and there are many ways of looking at it and interpreting it.

The first thing that struck me, in the bit quoted above, is that it is disingenuous. It is trying to compare chalk and cheese. “When six African religious leaders walk out of Canterbury next week, they will not be leaving the Anglican communion, but walking out of its funeral”.

That might be so, but if it were making a fair comparison, the article would have to show that those six African leaders believed that genocide was just and right, and that only evil and unjust people would believe it was not. The article does not say that, but it implies it by innuendo. And behind that one can perhaps discern a racist and Western imperialist sub-text — Who are these ignorant upstart African leaders to lecture us enlightened Westerners on morality?

And if the West wants to lecture African church leaders about genocide, what about the invasions and destruction of Iraq and Afghanistan? If you want to compare apples with apples, then compare violence with violence, not violence with sex. And as Samuel Huntington so pithily put it,

The West won the world not by the superiority of its ideas or values or religion (to which few members of other civilizations were converted) but rather by its superiority in applying organized violence. Westerners often forget this fact; non-Westerners never do.

So Andrew Brown’s pointing a finger at African church leaders about violence and genocide is more than a little disingenuous.

But Huntington seems to have got it wrong in one respect: though Christianity is a non-Western religion, many parts of Africa were converted to Christianity through Western missionaries, and the Anglican Communion itself is one of the results of that. And this points to another factor.

Estimates of the importance of religion in different countries differ according to different estimates. There’s a Wikipedia estimate here, and, here’s one from a more recent article:

Whichever set you choose, the countries whose religious leaders are most likely to walk out of the Anglican gathering are those where 80% or more of the population think religion is important, and those whom those African leaders most strongly disagree with are mostly from countries where fewer than 60% think religion is important.

And this, it seems to me, would make it likely that the African church leaders would be less inclined to take what Western church leaders say seriously, because they might see them as lacking faith, and speaking from the secular point of view of many of their compatriots. As long as such differing perceptions persist, the two sides are less likely to be able or willing to communicate.

Westerners generally take theological questions less seriously, because they are so secularised that they no longer think they matter. I recall that a black Lutheran theologian in South Africa once wrote that theological questions such as the two natures of Christ were purely Western concerns, and were not of much interest to Africans. I pointed out that most Western theologians don’t understand it, and don’t think it matters much. It started as an African issue, and remains one. He didn’t quite believe me, until he visited Egypt a couple of years later, and on his return remarked to me, “You know, those Egyptians really think the question of the two natures of Christ is important. Everyone wants to know where you stand on it.”

Anglicans have sometimes expressed themselves willing to drop the Filioque from the Symbol of faith, not because they no longer find it acceptable, but because they don’t think it important enough to make a fuss about, and see it as an irenic gesture towards the Orthodox. But when it comes to issues they do feel strongly about, like the ordination of women, or the moral rightness of same-sex fornication, they are less willing to be accommodating towards the Orthodox.

One Orthodox friend wrote of this “Lets hope for a split. The European and American “churches in communion with Canterbury” are committing slow suicide by standing for nothing that secular public opinion opposes strongly. The African and Asian parts are what may still be salvageable.”

My prayer would be somewhat different.

My prayer would be that the Orthodox Church, especially but not only in the West, should not make a similar capitulation to secular culture, and be seduced into providing a watered down “civil religion” like the one Sergei Chapnin talks about in this interview on Orthodoxy without Christ. The Anglican obsession with and splits over sex is paralleled by Orthodox disputes and splits over old and new calendars, and they have salvaged very little.

Sex is of course more sexy than calendars, and more sexy than genocide and violence in the world. But the obsession with sex is a convenient distraction from more serious problems. There was a little spark when Archbishop Justin Welby started making noises about restraining loan sharks, and that got the media on his case, just as they have been after Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders. And so it was back to sex. It’s safer. Just repeat after me, safe sex, safe sex, safe sex.

January 5, 2016

The end of the South African dream?

In recent years there has been a marked increase in in the number of racist utterances by South Africans on social media on the Internet generally. And if people are not making racist utterances themselves, they often seem to be accusing others of doing so.

What happened to the Rainbow Nation?

A few days ago I commented on conflict in Ukraine,

In such a delicately balanced situation, it would be sensible for politicians to try to reduce fear and insecurity in all parts of the country by encouraging religious and cultural tolerance (most politicians in South Africa tried to do that in the same period, in the 1990s — they spoke of “many cultures, one nation”).

But in eastern Europe and the Balkans, the opposite was taking place. When we were moving away from apartheid, they were eagerly embracing it. Hence the break-up of Yugoslavia. And Ukrainian politicians generally played a zero-sum game. They did not seek a win-win solution so that all Ukrainians could live in harmony. They stood for a win-lose scenario, where one side would gain ascendancy over the other. And in this they were aided and abetted by the outside forces representing the clashing civilizations, just as Huntington predicted. Russia (representing the Orthodox civilization) supported the eastern Ukrainians, and the Western civilization supported the politicians representing the interests of Western Ukrainians. The outside players, for their own purposes, were also interested in a win-lose situation.

When I say such things, Ukrainian nationalists accuse me of “Putinism”, and Russian nationalists accuse me of parroting Western propaganda.

But if South Africa was steering a different course to that of Eastern Europe and the Balkans in the 1990s, it seems that we are now swinging round to go the same way.

And in a way, it was only to be expected.

History is full of examples of social reforms and revolutions that betrayed the ideals of their founders. If you are lucky, the first generation of leaders are faithful to their ideals, but the moment the turning point is reached, the moment the thing hoped for seems to be within grasp, the thing gets weighed down by bandwagon jumpers whose main aim is to feather their own nests. I certainly didn’t expect any better, and I don’t know of many people who did. The only one I know who did was a Dominican priest, Fr Albert Nolan, who wrote in the mid-1990s that this, at last, was the revolution to end all revolutions, that evil had been utterly destroyed, and we would all live happily ever after.

History is full of examples of social reforms and revolutions that betrayed the ideals of their founders. If you are lucky, the first generation of leaders are faithful to their ideals, but the moment the turning point is reached, the moment the thing hoped for seems to be within grasp, the thing gets weighed down by bandwagon jumpers whose main aim is to feather their own nests. I certainly didn’t expect any better, and I don’t know of many people who did. The only one I know who did was a Dominican priest, Fr Albert Nolan, who wrote in the mid-1990s that this, at last, was the revolution to end all revolutions, that evil had been utterly destroyed, and we would all live happily ever after.

In many ways there was a noticeable decrease in racism in South Africa between 1994 and 2004. No, it did not vanish entirely, but it was lessened. You could see little black children and little white children playing together in the street. Twenty years before, if they had been doing that even in a private garden the neighbours would have called the police, especially if it was a “white” neighbourhood. I recall that in 1985 we went to a church service in a black township (Ekangala, near Bronkhorstspruit). The service was held in a house and the congregation overflowed into the yard, and afterwards our children were playing in the street with some others, and a police van came by and questioned them (they were aged about 7-8 at the time). I don’t know whether a neighbour called the police, but at the time that sort of thing “wasn’t done”. After 1994 it was done, and no one called the cops.

In many ways there was a noticeable decrease in racism in South Africa between 1994 and 2004. No, it did not vanish entirely, but it was lessened. You could see little black children and little white children playing together in the street. Twenty years before, if they had been doing that even in a private garden the neighbours would have called the police, especially if it was a “white” neighbourhood. I recall that in 1985 we went to a church service in a black township (Ekangala, near Bronkhorstspruit). The service was held in a house and the congregation overflowed into the yard, and afterwards our children were playing in the street with some others, and a police van came by and questioned them (they were aged about 7-8 at the time). I don’t know whether a neighbour called the police, but at the time that sort of thing “wasn’t done”. After 1994 it was done, and no one called the cops.

I thought of what happened in South Africa in 1994 rather as Fr Alexander Schmemann described Christian marriage. It was almost like a sacrament, in the way that marriage is. He wrote:

Each family is indeed a kingdom, a little church, and therefore a sacrament of and a way to the Kingdom. Somewhere, even if it is only in a single room, every man at some point in his life has his own small kingdom. It may be hell, and a place of betrayal , or it may not. Behind each window there is a little world going on. How evident this becomes when one is riding on a train at night and passing innumerable lighted windows : behind each one of them the fullness of life is a “given possibility,” a promise, a vision. This is what the marriage crowns express : that here is the beginning of a small kingdom which can be something like the true Kingdom. The chance will be lost, perhaps even in one night ; but at this moment it is still an open possibility. Yet even when it has been lost, and lost again a thousand times, still if two people stay together, they are in a real sense king and queen to each other (Alexander Schmemann, For the life of the world).

And in 1994 we in South Africa were given such a chance, to make a society that was something like the true Kingdom, a society in which there would be freedom, justice and peace on earth, as it is in heaven. And I still believe that Mandela, Tambo and Sisulu, among others, really did have a vision for such a society. And even though the possibility has been largely lost, it has not been completely lost.

But a fellow-member of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship responded to my comment about multicultural societies thus:

So, when we talk of “homogenization” vs. advocating constructed identities, using religion or any other markers, as both being bad choices, we are then forced to make a third way; but the third way of multicultural tolerance (which might be somewhere mid way between sameness and nationalism’s fracturedness) is also fraught, as we are learning in the US and especially in Europe. “Many cultures, one nation” always proves a bad way to build a nation or reform already fractured society, almost by definition. It may endure for a space as better than what it replaced, but multicultural societies have a way of either homogenizing or developing divisional fault lines.

And yes, that gets to the heart of the matter, and perhaps that is the conversation we ought to be hasppening.

Yet there is still a problem. In Europe, perhaps, with its history of past nationalisms, which led to the development of nation-states, usually by splitting multinational empires, homogenizing may be a possibility, but in South Africa I don’t think it is an option. The alternatives are either multiculturalism or apartheid. And we know apartheid didn’t work.

And so, in 1994 we sang with the Palmist:

1. When the Lord turned again the captivity of Sion : then were we like unto them that dream.

2. Then was our mouth filled with laughter : and our tongue with joy.

3. Then said they among the heathen : The Lord hath done great things for them.

4. Yea, the Lord hath done great things for us already : whereof we rejoice.

5. Turn our captivity, O Lord : as the rivers in the south.

6. They that sow in tears : shall reap in joy.

7. He that now goeth on his way weeping, and beareth forth good seed : shall doubtless come again with joy, and bring his sheaves with him (Psalm 125/126, Coverdale translation).

Yes, we were like them that dream. Yes, for a brief time we saw the dream come true, and then was our mouth filled with laughter and our tongue with joy.

For a brief time the vision of freedom came true, and those who experienced the freedom and the vision, in however limited a way, the first democratically elected parliament of South Africa, sought to capture some of that vision and enshrine it in the Constitution. And while we have the constitution, and the constitutional court to uphold it, then no matter how bad things may get, they cannot get as bad as they were under apartheid.

Of course some day a new tyrant may come along and suspend the constitution and sack the members of the constitutional court, and then we will be back to square one, or back to 1961, when Verwoerd was dreaming of apartheid, and B.J. Vorster was turning South Africa into a police state to make sure that if anyone had different dreams, they told no one about them.

So the Rainbow Nation was and is a dream, and it’s up to us to make it come true. It was not a magic trick. No one waved a magic wand and put right everything that was wrong. It was up to us to make the vision a reality. And we need to recognise that the apartheid period has left a residual deposit of evil which we have not done enough to remove.

Back in 1965, seventeen years after the National Party had come to power, and it seemed to have been in power forever, an English friend said to me, “When South Africa has sorted out the problem of the black and the white, it will come face to face with the real problem — the haves and the have nots.”

Back in 1965, seventeen years after the National Party had come to power, and it seemed to have been in power forever, an English friend said to me, “When South Africa has sorted out the problem of the black and the white, it will come face to face with the real problem — the haves and the have nots.”

I’ve quoted that before, and I’ll probably quote it again before I die.

After 1994 I thought that we were on the way to solving the problem of the black and the white, and could begin to face the bigger problem of the haves and the have-nots. But that seemed to recede and was put on the back burner, and now the problem of the black and the white is coming back, and I fear that the problem of the haves and the have-nots will be taken off the stove altogether.