Stephen Hayes's Blog, page 45

October 3, 2015

A Historical Look at the Vespers Service | Fr. Ted’s Blog

Vespers is the evening prayer service in the daily cycle of liturgical services. It can be done every day of the year and is designed to be done at sunset each day. Archbishop Job Getcha offers us some idea as to when the various elements in our current Vespers service became part of the rubrics for Vespers.

Source: A Historical Look at the Vespers Service | Fr. Ted’s Blog

September 30, 2015

Saints, witchcraft and witch hunts

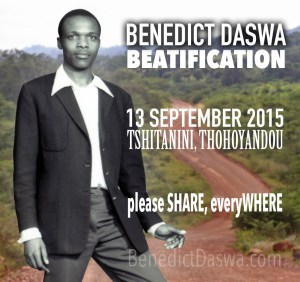

In September 2015 the Roman Catholic Church officially beatified a new martyr in Southern Africa, St Benedict Daswa.

This event received quite wide media publicity, though some was rather misleading. Some said that he was South Africa’s first saint, though for several years previously Anglicans in South Africa had been venerating Manche Masemola, a teenage girl who was beaten to death by her family in 1928 when she became a Christian. She was preparing for baptism, and it was said that she was baptised in her own blood.

This event received quite wide media publicity, though some was rather misleading. Some said that he was South Africa’s first saint, though for several years previously Anglicans in South Africa had been venerating Manche Masemola, a teenage girl who was beaten to death by her family in 1928 when she became a Christian. She was preparing for baptism, and it was said that she was baptised in her own blood.

Another misleading aspect of the reports about Benedict Daswa is that they said he was killed for opposing or not believing in witchcraft. This diverts attention from the most significant aspect of his death and subsequent beatification: he was killed for refusing to participate in a witch hunt. Those who did particpate in the witch hunt opposed witchcraft just as much as Benedict Daswa — something that media reports sometimes failed to make clear. Tshimangadzo Daswa: South Africa’s first martyr to be beatified | Daily Maverick:

In 1989 heavy lightning strikes caused some homes in his village to be burnt to the ground. The villagers believed this was not natural; they believed they had to find the person responsible for the fire. A decision was taken to consult a sorcerer in a nearby village to seek out the ‘witch’ responsible. Each villager was asked to contribute R5 towards the cost of the consultation. Daswa was not present when the decision was made and when he returned he tried to explain that lightning and thunderstorms are natural phenomena. His explanation was rejected and the people insisted that they consult a sorcerer. The villagers were angered by the fact that he refused to pay the money they had agreed upon.

There are several significant things here.

Not the least of them is that it indicates a huge change in the thinking of the Roman Cartholic Church. In the Great European witch hunt in the Early Modern period, the so-called “burning Times”, the Roman Catholic Church not only connived at witch hunts, it often took an active part in them, and in many cases initiated them. Declaring someone who refused to participate in a witch hunt a saint therefore shows just how much things have changed from 500 years ago.

Perhaps even more significant is that in the 1990s witch hunting was a big problem in South Africa, especially in the Limpopo Province, where Benedict Daswa lived and died. Twenty years ago I wrote an article on Christian reponses to witchcraft and sorcery, pointing out that the Zionists often had a better response than those Christian denominations that liked to consider themselves “mainline”. Declaring Benedict Daswa a saint, however, may be the best response of all.

It could be said that declaring someone a saint has a greater and more noble purpose than teaching a didactic moral lesson that witch hunts are wrong. But, at the very least, declaring someone a saint does draw attention to that person as having lived, at least in some sense, an exemplary Christian life, and if someone is an exemplar then one can tell their story to urge others to follow their example.

The article in the Daily Maverick goes on to point out that in many ways Benedict Daswa’s behaviour was countercultural Tshimangadzo Daswa: South Africa’s first martyr to be beatified:

the Daswa case does raise some broader questions about local cultures and Christianity. For many people in Africa there is still tension between the Christian faith and local culture. Christianity is still seen, largely, as mediated through a western mind-set. Many Christian symbols and expressions are western in origin. Christianity, in many forms, is growing in the southern hemisphere and, specifically, in Africa. The Daswa case highlights a huge challenge Christianity faces: In what ways will the church break free of its western dominance and become more accommodating of non-western cultures? How will Christianity interract with local customs and cultures so that it can be expressed in those local customs, cultures and symbols?

But if Benedict Daswa was countercultural, so were most Christian saints. Their lives were often lived in contrast to the prevalent lifestyle of the society around them. Another article on the Daswa beatification makes this point, comparing Benedict Daswa with Steve Biko Parallels between Biko and Daswa – The Mercury: “While they were very different individuals, both men rejected blindly following the herd, and took a stand for what is right.”

As I pointed out in the article referred to above, the dominant resposse of Western modernity to witchcraft and sorcery is to deny that such things exist, and therefore to believe that the best way to combat witch hunts is to give people a Western education and a modern outlook so that they will no longer believe in the efficacy of witchcraft. This was the approach of many 19th century Protestant missionaries who came to Africa from Western Europe and North Americas. They believed that “civilization” must precede Christianisation. I noted that the Zionists did not take this approach. They took African witchcraft beliefs seriously, and combated them in a non-Western but Christian way.

Declaring someone a saint is in a way similar. It makes no judgements on the efficacy of witchcraft and sorcery, but it holds up someone who refused to participate in a witch hunt as an example to be emulated.

The Roman Catholic Church has also tried the modern approach.

It has published booklets in various African languages on how to construct a lightning conductor, with explanations of how it works. It seems that Benedict Daswa himself gave such an explanation for why he would not participate in a witch hunt.

I recall buying some of those booklets and distributing them to self-supporting clergy in the Anglican Diocese of Zululand in the 1980s. There had been news reports of people being killed by lightning strikes, and I thought the self-supporting priests and deacons could show their communities how to protect themselves.

The booklets provoked a lot of theological and missiological discussion.

One of the priests, Charles Zigode, was a shopkeeper, and he said he refused to protect either his shop or his home with a lightning conductor. Some of the others asked him why, and he said that the Zionists protected their homes with prayer flags. These were bamboo poles with blessed flags on the top. He told the Zionists he did not need a prayer flag, because he trusted in God to protect him without such an artifact. He said that if he were to erect a “scientific” lightning conductor, the Zionists would not believe that it was scientific, but would see it as the Anglican equivalent of one of their prayer flags, and show that he too needed a concrete symbol of divine protection.

There was very little mention in the discussion of the pagan Zulu form of protection, which sometimes took the form of a horn or pair of horns filled with muti, attached to the roof. The Zulu folklore explanation of thunder was that it was the hooves of heavenly herds of cattle, and the best counter to lightning would be to enlist the aid of a heavenly cowboy (umalusi wezulu) to keep the cattle under control.

The point here is that there is not a simple antithesis of Western culture and African culture. There are varying shades of Western and African, modern and premodern, pagan and Christian, with perhaps the postmodern ability to switch between them several times in the course of a single conversation.

And large-scale witch hunts seem to occur most frequently when modernity and premodernity meet and mingle.

September 26, 2015

The cult of Capitalism

I passed on one of those illustrated epigrams one finds on Facebook (Warning: Graphic content) as one sometimes does, with the following comment. And then I thought that perhaps that there was more that could be said about it.

This has been the central struggle of the Christian faith, at the ideological level, for the last 30 years. This has been at the heart of the Kulturkampf, the “culture wars”. It is this idolatry that has undermined and weakened the Christian faith. It is not so much capitalism itself (which has been around for a long time), but the *cult* of Capitalism that is the problem. And it is the cult of Capitalism that has been the dominant theme of the West since the Reagan/Thatcher years, and through globalization has spread throughout the world. It is the ideology of “There is no god but the Market, and Ayn Rand is its prophet”. I am the Market your god, and me only shall you serve.

This has been the central struggle of the Christian faith, at the ideological level, for the last 30 years. This has been at the heart of the Kulturkampf, the “culture wars”. It is this idolatry that has undermined and weakened the Christian faith. It is not so much capitalism itself (which has been around for a long time), but the *cult* of Capitalism that is the problem. And it is the cult of Capitalism that has been the dominant theme of the West since the Reagan/Thatcher years, and through globalization has spread throughout the world. It is the ideology of “There is no god but the Market, and Ayn Rand is its prophet”. I am the Market your god, and me only shall you serve.

A Facebook friend commented that perhaps the decline in Christianity in the West was brought about by the church’s obsession with sexuality. But I don’t think so, though I do think that it was the obsession with sex that prevented them from seeing the elephant in the room.

Pussy Cat, Pussy Cat, where have you been?

I’ve been to London to visit the Queen

Pussy Cat, Pussy Cat, what saw you there?

I saw a little mouse under a chair.

We see what we want to see, and the Western churches, especially, became so obsessed with the little mouse of sex, in some cases tearing themselves apart over it, that they failed to see the bigger problem, and the huge betrayal that it represented.

In South Africa denominations that had been quite prominent in the struggle against apartheid seemed to sit back after 1994 and wait for the government to fix the country. In the 1970s many of them had sponsored or supported Sprocas, the Study Project for Christianity in Apartheid Society, which looked for alternatives to apartheid, but by 1994 very few could be bothered to think about it.

The ANC had its own Reconstruction and Devel;opment Programme (RDP), which envisaged quite a large part for civil society (which of course included the various Christian bodies in South Africa), but within a year the ANC had abandoned it for the neoliberal GEAR (Growth, Employment and Redistibution). If Christian bodies had anything to say about this, it was not widely reported.

The commercialisation of building societies in 1987, and of mutual insurance societies ten years later (with one of them even having the chutzpah to continue to call itself the “Old Mutual”, a misleading description if ever there was one) evoked minimal comment from the churches. It looked as though most of the churches that had opposed apartheid, and the ANC itself, had swallowed the Thatcherist line, with hook and sinker as well.

As some readers of this blog may know, I’m writing a book with John de Gruchy on the rise and fall of the charismatic renewal movement in South Africa, and one thesis I have is that the decline of the movement in the 1980s was brought about, at least in part, by the rise of the Religious Right in the USA, and the way in which its ideology polluted the stream of charismatic literature (books and tapes) which flowed from the USA to South Africa and other parts of the world. One form that this pollution took was the growth of Prosperity Theology (the gospel contextualised for yuppies), but there were others as well.

The extent to which this idolatry of The Market has penetrated into Christian groups of all backgrounds and traditions is alarming. I have been amazed at the number of Christians (mainly in the USA) who are quite happy to defend the thesis that “Universal Health Care is Theft”, and who apparently see no contradiction between that and their Christian faith.

The extent to which this idolatry of The Market has penetrated into Christian groups of all backgrounds and traditions is alarming. I have been amazed at the number of Christians (mainly in the USA) who are quite happy to defend the thesis that “Universal Health Care is Theft”, and who apparently see no contradiction between that and their Christian faith.

Capitalism is an economic system that has been in existence for a long time. It can be, and has been criticised, modified and reformed. Christians can and have lived under many different economic systems, and none of them will be perfect as long as human beings are not perfect. Marx criticised 19th century capitalism. Some of his criticisms were spot on, others were wide of the mark. Some were spot on at the time he wrote, but are wide of the mark now, because the system has changed and adapted.

But it was Ayn Rand who turned capitalism into an ideology, and her followers who turned it into a cult, and Reagan and Thatcher who turned it into the Established Church of the West, a system whose values and fundamental principles cannot be questioned, and must be imposed on others by varions means, such as Structural Adjustment Programmes. This ideology is sometimes called ‘neoliberalism”, especially by those who are critical of it, because it harks back to the laissez-faire economic liberalism of the 19th century.

The Roman Pope, on his visit to the USA, has reopened the debate in that country, and perhaps encouraged people to think again about things they have never before thought to question. In his explicit mention of Dorothy Day, whose communitarianism is not only an alternative to Capitalism, but ideologically almost in direct antithesis to it, he has opened the way for a wider debate.

For Christians, the Market, like the Sabbath, was made for man, not man for the Market.

September 22, 2015

St. Lydia the New Martyr of Russia | lessons from a monastery

The Grace-filled Lydia was finally arrested on 9 July 1928, when the secret police discovered that she was behind the circulation of typed booklets containing lives of Saints, prayers, and homilies and teachings of old and new Bishops. They had noticed that the typewriter on which the booklets were typed had a defective letter K, and were thereby able to track her down.

Source: St. Lydia the New Martyr of Russia | lessons from a monastery

September 18, 2015

The dissolution of the Anglican Communion and the end of ecumenism

It seems that the Anglican Communion is at last to be headed for dissolution. And I suppose that the question one must ask is “What price ecumenism now?”

Archbishop of Canterbury plans to loosen ties of divided Anglican communion | The Guardian:

The archbishop of Canterbury is proposing to effectively dissolve the fractious and bitterly divided worldwide Anglican communion and replace it with a much looser grouping.

Justin Welby has summoned all the 38 leaders of the national churches of the Anglican communion to a meeting in Canterbury next January, where he will propose that the communion be reorganised as a group of churches that are all linked to Canterbury but no longer necessarily to each other.

He believes that the communion – notionally the third largest Christian body in the world with 80 million members, after the Roman Catholic and the Orthodox churches – has become impossible to hold together due to arguments over power and sexuality and has, for the past 20 years, been completely dysfunctional.

The 1910 World Mission conference in Edinburgh, Scotland, is widely regarded as the start of the 20th-century ecumenical movement. The question raised there was how could divided Christians evangelise the world, when Christians were speaking with so many different voices? So the 20th century saw various attempts to bring Christians of different traditions together, and greater unity among Christians would lead to more effective mission.

To begin with the Anglicans tried to position themselves as a “bridge church”, an example of ecumenism. They positioned themselves between the Roman Catholics and Protestants, and pointed to the fact that for a long time they had been home to several different traditions — High Church, Low Church, Broad Church etc — which had somehow managed to muddle along together, so the Anglicans could provide a model of ecumenism. Some Anglicans even reached out to the Orthodox, especially those of the Church of England who welcomed refugees from the Russian revolution in the 1920s and 1930s.

To begin with the Anglicans tried to position themselves as a “bridge church”, an example of ecumenism. They positioned themselves between the Roman Catholics and Protestants, and pointed to the fact that for a long time they had been home to several different traditions — High Church, Low Church, Broad Church etc — which had somehow managed to muddle along together, so the Anglicans could provide a model of ecumenism. Some Anglicans even reached out to the Orthodox, especially those of the Church of England who welcomed refugees from the Russian revolution in the 1920s and 1930s.

Fifty years on things appeared less certain. In the 1960s some Anglican theologians began publishing works of theological revisionsim that enlivened theological debate at the time, and even got a secular-minded public interested for a while. Some called for “relevance”, but ultimately only succeeded in become even more irrelevant to the world around them, because at the root of their notion of “relevance” was the desire for the church to fit into and reinforce the world’s status quo.

From the 1970s onwards Anglicans became more and more introspective, squabbling about their own internal structures — whether they should ordain women, and what ministries they should be ordained to, and so on. As the article cited above put it,

the archbishop felt he could not leave his eventual successor in the same position of “spending vast amounts of time trying to keep people in the boat and never actually rowing it anywhere”.

At that time I was an Anglican, and thirty years ago I left, for that very reason. I could not face the prospect of spending the next thirty years of my life arguing with people in the boat about what the boat was and where and how it should be rowed, instead of actually rowing it anywhere.

It seemed that two broadly defined “parties” were emerging, but I didn’t feel at home in either of them. The idea of Anglicanism as a “big tent” and notions of being “inclusive” were a chimera and always had been.

It seemed that two broadly defined “parties” were emerging, but I didn’t feel at home in either of them. The idea of Anglicanism as a “big tent” and notions of being “inclusive” were a chimera and always had been.

It was actually nothing new. From an Orthodox point of view, the Orthodox who were most open to Anglicans were those who had found Anglicans who were most open to them. They rarely met Anglicans who weren’t interested in Orthodoxy — if they had, they might have had a different opinion.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Patriarchate of Alexandria was seriously considering recognising Anglican orders, on the basis that there was sufficient theological overlap to do so. Bishop Methodios Fouyas investigated it, but found that Anglicans spoke with so many different voices that it was impossible to determine what Anglican theology was. He detailed his findings in a book Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism and Anglicanism, and that idea was dropped. In any case, Anglicans nowadays seem to be far more concerned about sexuality than about orders, and the debates seem to be far more acrimonious than they were 30 years ago, with white gay activist Anglicans in the West hurling racist insults at homophobic black Anglicans in Africa.

The division here is not a purely Anglican phenomenon, but is found in many Western Christian bodies; I’ve dealt with it more fully in another post, so will say no more about it here.

What does concern me here, however, is what this says about 20th-century ecumenism. For all the talk of unity, it seems that fissiparousness in Christianity is increasing, and wonder about groups like the World Council of Churches, which sprang out of the 20th century ecumenical movement. Is there any future for them, and what purpose do they serve. Will they accept all the broken pieces of the soon-to-be-former Anglican Communion, and try to bring about unity among them? Or what?

September 16, 2015

Suburban adultery, Scotch on the rocks and martinis

On Green Dolphin Street by Sebastian Faulks

On Green Dolphin Street by Sebastian Faulks

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

I didn’t like this book. I really didn’t like this book. But I couldn’t stop reading it.

I read the first chapter, and thought “this is not my cup of tea”. I read another chapter, and thought I can stop reading it at any time. I don’t have to plough my way through it. But I read another chapter anyway.

I don’t like this book. I don’t like the characters, or the clothes they wear. They are the wrong generation, my parents generation. But still I read. Why? It’s 1960, the election campaign in which Kennedy was elected, the first American election I can really remember. I remember wishing that Kennedy would win, because Kennedy was a Roman Catholic and back then I was a High Church Anglican, and High Church Anglicans were second-class Catholics. Kennedy would bring morality and Christian values to American politics, world politics, or so I thought. The Cuban missile crisis put me right on that score. American hypocrisy, and the thought that Krushchev had saved the world from a nuclear holocaust.

This was posted on Facebook by Logan Wagoner with the comment “Same car, same woman. Wish the world understood this.” The car would have been a familiar sight in the setting of this book. So what’s changed? The clothes.

1960 was also the year I first heard the name of Jack Kerouac, the year I read The Dharma bums. Jack Kerouac is the same generation as these people, but what a world of difference.

But still I read it, until I eventually reached the end. I think it is well written, but it recalled to me people of my parents’ generation, with their business suits and ties and hats and women with hats and gloves and lipstick and high-heeled shoes and well-stocked drinks cabinets. When people visited you had, at the very least, to offer them a choice of brandy, whisky, beer and gin. People of that class did not offer skokiaan and Barberton.

And Faulks describes it all, in excuciating detail — the clink of ice in glasses, the martinis, the clothes, and all the rest.

No, it is not my kind of book, and these are not my kind of people.

Faulks is even self-mocking, having characters rather disparagingly referring to novels about suburban adultery, like Peyton Place, in the middle of his own novel about suburban adultery.

I didn’t like this book, but I read it.

September 13, 2015

Theology better training in management than an MBA?

The recent furore about the closure of the Religious Studies department at the University of Stirling in Scotland made me think again about the value of studying theology at university. In response to something a friend posted about this on Facebook, I remarked that it was not for nothing that theology was called “the Queen of the Sciences”, and it probably does a better job of equipping people for management than an MBA.

My justification for this was that when the University of South Africa (Unisa), in the 1990s, first felt the need to include black faces among the Afrikaner Broederbonders who dominated the university administration, the only place they could find competent people was from the theology faculty, which they “asset stripped” of some of its best academics to turn them into administrators.

I’m not thinking here so much about the study of religion as a phenomenon (which was what the University of Stirling concentrated on), but rather the study of Christian theology itself.

My evidence for this contention is purely anecdotal, so many may not regard it as worth much, and my experience relates mainly to the University of South Africa, where I worked in the Editorial Department for 13 years, and the Department of Missiology (in the Faculty of Theology) for four years.

Unisa main campus, Pretoria

The Editorial Department at the university saw most of the study material sent to students (Unisa is a distance-education university), and thus was, in a sense, the backstop of quality control. The quality of the study materuial varied tremendously.

In 1994 we had David Langhan lead a seminar for the Editorial Department on good and bad study material. He asked us to collect samples of second-year student assignments from various departments, which he then examined, and chose four of them to comment on — one very good, one very bad, and two mediocre.

Unisa Library

The one he singled out as very good was from the Missiology Department. He analysed it, pointing out the evidence that the student was thinking for himself, and evaluating the study material. The one that was very bad was from the Education Faculty, which showed evidence of rote learning, and failure to understand the material.

We (the Eduitorial Department) also arranged a seminar to which the teaching staff were also invited, run by Fred Lockwood, of the Open University in the UK. Some academics appreciated it, while others felt threatened by it — what did mere taalversorgers (language caretakers) know about Science, which was purely the concern of academics? This attitude was especially to be found among members of the Education Faculty, which generally produced the worst-quality study material.

One thing that was rather disappointing was that Fred Lockwood chose for his examples the cosmetics industry, which was not among the subjects taught at Unisa. In explaining the reasons for his choice he made some rather disparaging remarks about the humanities, and said he had chosen a subject that was of more practical use. That indicated, to me at least, that Unisa was not the only screwed up university in the world. If that represented the Open University in the UK, it was in just as much trouble as Unisa, for of what real value is the cosmetics industry? It is concerned with frivolous luxuries. If economic usefulness was to be the main criterion, then a topic like food production, or even steel production might be justifiable — but cosmetics? That surely signified twisted values.

And this is where theology and management meet. Theology teaches people to weigh up values, and to make decisions based on those values, to think about all the factors involved when making decisions. And this is the very thing that many MBAs seem unable to do. And it was this that meant that Unisa had to pull in many of its new administrators from the theology faculty. Why not from its economics faculty, which ran its own MBA programme? It seems that few or no competent people were to be found there.

And this is where theology and management meet. Theology teaches people to weigh up values, and to make decisions based on those values, to think about all the factors involved when making decisions. And this is the very thing that many MBAs seem unable to do. And it was this that meant that Unisa had to pull in many of its new administrators from the theology faculty. Why not from its economics faculty, which ran its own MBA programme? It seems that few or no competent people were to be found there.

There used to be a very good record shop in Pretoria called Look and Listen. It was big, and had a very wide selection of music, and staff who were helpful and knew what they were talking about. People went there from all over town, because they knew they could find what they were looking for.

Then it was taken over by a firm that knew nothing about records, but perhaps had MBAs who thought they knew all about management. The shop was too big, so they were paying too much rent. So they moved to a smaller shop. That meant they could not stock as much as the old shop, so they kept only the best selling lines. And less-knowledgeable staff might cost less, and could be conned into accepting the least that the labour laws would allow.

Now people no longer travel to Look and Listen from all over Pretoria, because they can find an identical record shop from another chain in their own local shopping mall, which stocks the identical best-selling stuff, and does central ordering. Now the same thing is happening to a chain of bookshops that as similarly been taken over by a firm run by MBSs who know the price of everything and the value of nothing.

And that is why people trained in theology can probably make better management decisions than MBAs.

Those who, in spite of this, continue to diss theology and the humanities, should read this piece by Jonathan Jansen, probably the best educationist in South Africa today. And see also Transformation in education — or the lack of it | Notes from underground

September 2, 2015

Cape Town to Hermanus

Continued from More cousins and friends in Cape Town

On Sunday morning we went to the Divine Liturgy at St George’s Cathedral in Woodstock.

St George’s Cathedral, Woodstock, Cape Town

Fr Nicholas invited me to serve with Deacon Michael, and we were joined by Archbishop Sergios, Metropolitan of the Cape of Good hope, who welcomed us to his diocese, and took me in tow afterwards to have coffee in the hall, and discussed the possibility of joint training meetings with our diocese similar to the training meeting we held three weeks ago.

His Eminence Metropolitan Sergios, Archbishop of the Cape of Good Hope. 30 August 2015

We then left Cape Town for Hermanus, calling at Somerset West on the way to have brunch with nephew Alan Machin — at about 3:00 pm. Al has been working in Cape Town for some time, doing engineering drawings.

Alan Machin & Val Hayes, Somerset West. 30 August 2015

At Hermanus we are staying at the Volmoed community in Hemel en Aarde (heaven and earth) valley, and this was the view from our front door when it had finally stopped raining.

Volmoed Community, Hermanus

We asre staying in Faith Cottage, and I’m spending some time talking to John de Gruchy about the book we are writing on the charismatic renewal movement in South Afirca.

Faith Cottage at Volmoed, Hermanus

You can read more about the Volmoed Community here. We went in to Hermanus town, which has some nice bookshops, where you can often find books that are not available in the big chain bookshops like Exclus1ve Books.

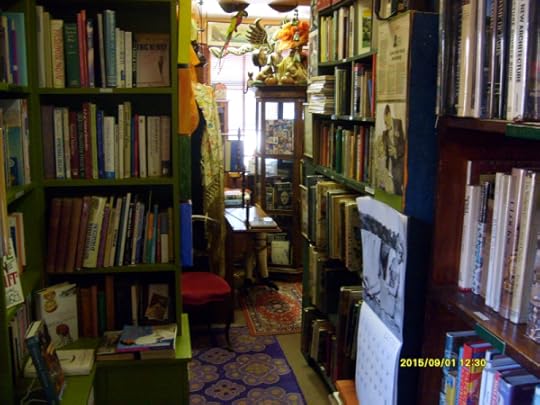

Hemingway’s Bookshop, Hermanus

It’s a nice place just to browse around, and in some ways looks like a place out of a fairy tale, with hidden nooks and crannies, probably not watched by security cameras, and if you wander too far perhaps you could find yourself in another world.

Hemingway’s book shop, Hermanus

We had coffee in the Old Harbour Cafe, and beyond it was an art gallery, glimpsed here through the door at the end of the veranda

At this time of the year, it seems, everyone comes to Hermanus to see the whales, so we had a look over the bay, and saw a couple, but too far away to be worth trying to take photos of. There’s a pleasand path around the clifftops, with notes on flora and fauna, and some interesting sculptures.

Seafront sculpture, Hermanus

There are notes on some of the flora and fauna in the area, and we could hear the clicking frogs.

The coast at Hermanus

Then it was back to Volmoed for another session with John de Gruchy to discuss our book on the charismatic renewal, wo which we have given the provisional title of The charismatic renewal and the churtch struggle.

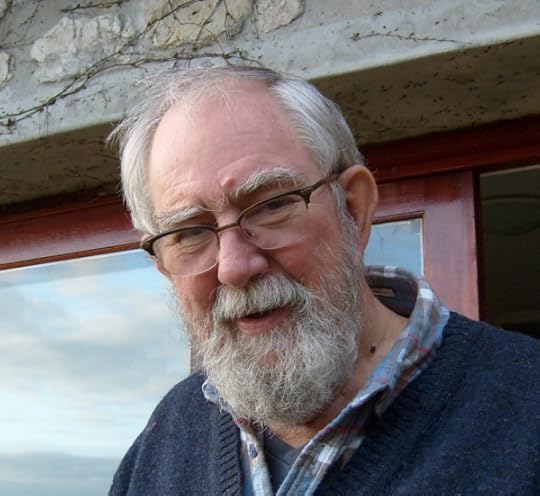

John de Gruchy

August 27, 2015

Kamieskroon to Robertson

Continued from Namaqualand Spring: Lily Fountain and flowers

Saturday 22 August 2015

We were sad to leave Kamieskroon after spending three nights there, and we left before dawn and drove down the N7 towards the Western Cape. The sun rose just after we passed Garies, where we stopped for petrol, but the national road bypasses most of the towns along the way.

Sunrise on the N7, somewhere near Garies

We bypassed Bitterfontein, with its railway line — it was still the railhead for points further north. As we approached Vanrhynsdorp there was a large rectangular mountain to the left, looking, as Val put it, like a slab of butter. I thought it looked like an alien artifact, and imagined one day the rocky comouflage crumbling away to reveal an enormous spaceship or something.

A mountain, or an alien artifact disguised as one?

We bypassed Vanrhynsdorp as well, and there was a sign pointing to the mountain labelled “Gifberg”. After Vanrhynsdorp the countryside was more familiar to me, and the previous times I had travelled this road, in 1971 and 1972, it had still been daylight.

We crossed the Olifants River at 10:20 am, 242 km from Kamieskroon, and stopped to take photos, as Val’s great great great grandfather Frank Stewardson had taken 5 days to cross the river with his herd of cattle back in 1862, though it may not have been at this particular point.

Olifants River

The road followed the course of the river southwards for some distance, though it was shorter than I remembered, and we only got one or two glimpses of the irrigation canal, which in my recollection had seen almost endless the first time I saw it, though perhaps one gets a better view of it travelling the other way. I believe wit was built during the Great Depression as a project to create employment, back in those days only for white people.

As we approached Clanwilliam there were road works, with stop/go sections, though we were lucky, and arrived at the tail of the queue, and did not actually have to stop once. There were still spring flowers along the sides of the road, giving the countryside a festive air, mainly yellow ones, with occasional patches of the orange Namaqualand daisies as well. We by-passed Clanwilliam, and the traffic on the N7 was heavier, and the road works continued for some way beyond, though we still passed through the stop/go sections without having to stop.

Roadside flowers along the N7 between Clanwilliam and Citrusdal, with the Cederberg in the background

We turned off the N7 at Citrusdal and drove straight through, and up and over the Middelberg Pass, 1071 metres high, which was similar to the pass leading from Kamieskroon to Leliefontein. If there were any cedars growing on the Cederberg range, we didn’t notice them. Beyond that we drove through a wide flat cultivated valley between two ranges of hills, not as scenic as I had imagiend it would be. We passed several signs warnong of pothols, but the potholes seemed to have been repaired. I’ve sometimes wondered why they go to the trouble and expense of erecting such signs, rather than just repairing the potholes.

The Middelberg Pass over the Cederberg

We drove down the Gydo pass, which we reached at 12:55 , 424 km from Kamieskroon, to Prince Alfred Hamlet and Ceres, stopping a a viewpoint halfway down to take photos, and recalled the impression of that I had had when we stayed at Ceres 40 years ago that it was in a bowl of mountains, entirely surrounded by a circular range of mountains. There were fields of plum trees with pink blossoms in places. We looked for somewhere to have lunch in Ceres, but most of the eating places seemed to be in shopping malls which were busy with Saturday afternoon shoppers, so we opted for take-away “hero” rolls from Steers, and drove to a sitplekkie on Michell’s Pass, and ate our lunch there. In the kloof below we could see the railway line winding down the side of the mountain, and from above it looked like a narrow-gauge one, because of the size of the surroundings, but when, after lunch, we crossed it, it turned out to be a standard (3′ 6″/1067 mm) gauge one.

Michells Pass

We then drove alongside the Langeberg through a much wider valley than the previous one, with fields and more spring flowers at the side of the road. and sometimes whole field of them. We passed teams of people repainting the lines of the road, which looked as though it had recently been resurfaced, and they were just packing up for the day. There were signs saying “No lines” but they seemed to have finished the job.

More spring flowers between Ceres and Worcester

At Worcester we got lost, as there were signs pointing to the R43 to Villiersdorp, but none pointing to the R60 to Robertson, and we drove around looking for at least one sign, and eventually went out on the Villiersdorp Road, and saw one turning off that, which eventually led us to the R60. We were rather surprised to see that the cultivation ended a short way out of town, and the road passed through uncultivated country, and there didn’t even seem to be many animals grazing. The railway line ran alongside the road, and it still seemed to be narrow gauge, even though it could not have been. Perhaps it is travelling on the Gautrain, with its broader gauge, that makes the others seem narrow.

As we got closer to Robertson we saw some passenger coaches in a siding, and wondered if that indicated that there was still a passenger service along here, though perhaps they had retired, as one had a big Steers advertising sign attached to it. We later discovered that they were retired, and at least one of the coaches was used as a church.

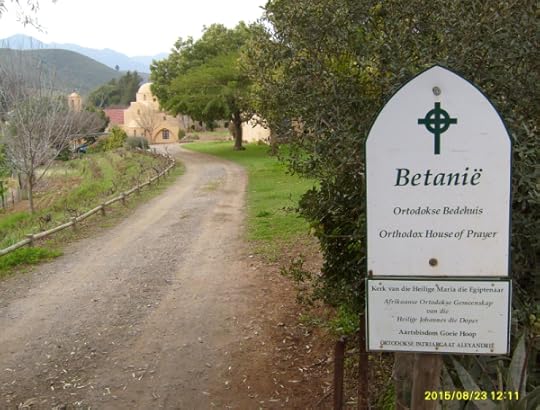

We drove straight through Robertson to Fr Zacharias van Wyk’s place, Bedehuis Bethanië, where we arrived just after 4:00, and Val and I went to see Macrina Walker at the Life-Giving Spring next door, an old dairy that she had converted into living and working quarters. She did her bookbinding there, but said she is now more into soap making, and has been living there for three years. We went over to Vespers at 5:00, sung in Afrikaans.

Bedehuis Bethanië

Fr Zacharias cooked supper, a special fish dish, and we sat on the veranda talking in the dusk, discussing the church, and the mission-mindedness, or lack of it. Fr Zacharias said they had installed green energy, and most of their electricity came from solar power. It again felt like something out of Tolkien, the last homely house, and I would noit have been surprised if elves and dwarves had joined us at the meal.

After Vespers at Bedehuis Bethanië

August 24, 2015

Going West through Bushmanland

19 August 2015

We left Augrabies at 7:20, and drove down the road towards Pofadder. In some places along the way there were fields of tiny mauve flowers. At 9:15 we reached

Pofadder, 138 km from Aughrabies, and stopped to take photos of it, as it was the provebial back of beyond. Val said that when they were young Pofadder’s CEK car registration was the only one they had not seen from the old Cape Province, and then one day in a camp at the Kruger Park there was one right in front of them. We had thought of coming here on our 1991 trip to Namibia, but it was too far out of the way. It actually seemed to be quite a pleasant little town, and more hilly than I expected.

Pofadder in the Northern Cape Province

We turned off to Pella, 170 km from Augrabies, which we reached at 9:36. It was another historic mission station, and we drove down into the valley where it was. The road was tarred, which I hadn’t expected, and the countryside was also hillier than I expected. the town itself was bright and clean, with well-kept houses. At one point we stopped to see where the church was, and were approached by a bloke who wanted to sell us a lump of rose quartz and said he was our information source, and pointed the way to the church, which we could have found without his help. The church was smaller than I expected — in reading about it I imagined some huge cathedral, and the descriptions said it was built by two priests, working on their own. Unlike the Moffat Mission, it was approachable.

The mission church at Pella, near the Orange River

An hour later, 219 km from Augrabies, we stoped to take photos of a social weavers’ nest on top of a telephone pole. We had taken some photos of them on our 1991 trip to Namibia, on the road to Onseepkans, but with digital cameras one could take more pictures, and I hopoed to catch the birds flying in and out.

A social weavers’ nest attached to a telephone pole. What will they do when cell phones take over completely?

We did not stop again until we reached Springbok, as we were worried that we might run out of petrol, and for the last 70 km the last block of the Yaris’s petrol gauge was flashing. We stopped at the first garage we came to, an Engen one, and they had no unleaded petrol. The next one, a Shell garage, was just replenishing its supplies, and and they said it would be some time before they could give us any. We finally found a Caltex garage and filled up there, 332 km after leaving Aughrabies.

Springbok, Northern Cape, with fields of orange Namaqualand daisies between the houses and the hills.

Then we went to the local Wimpy and had veggie burgers for lunch. The place was quite full, and there were two blokes sitting near us who looked like Mormon

missionaries. There were three others who looked like businessmen, and one of them looked as if he was trying to sell the others something. Springbok was a very pleasant little town, reminding me in a way of Mbabane, which we had last visited 30 years ago. Val had never been here before, and though I have been here twice, when travelling between Cape Town and Windhoek, it had been dark on both occasions, so I hadn’t had a chance to see the town.

Okiep, Namaqualand, a coppermining town. The chimney is left as a monument to Cornish miners who built Cornish=style beam pumps for the mines.

After lunch we drove up a hill and saw the view over the town, and then drove to Okiep, which I had also seen only at night. We took some photos of a chimney, a memorial of a Cornish beam pump, and St Augustine’s Anglican Church there, which was surprisingly big, and in front of it were a lot of orange

Namaqualand daisies. It was another place I recalled stopping at in the middle of the night — travelling from Cape Town to Windhoek, we stopped to borrow R10.00 from the Anglican rector, Llewellyn Jones, otherwise we would have not have been able to buy enough petrol to reach Windhoek.

St Augustine’s Anglican Churcdh, Okiep, Namaqualand

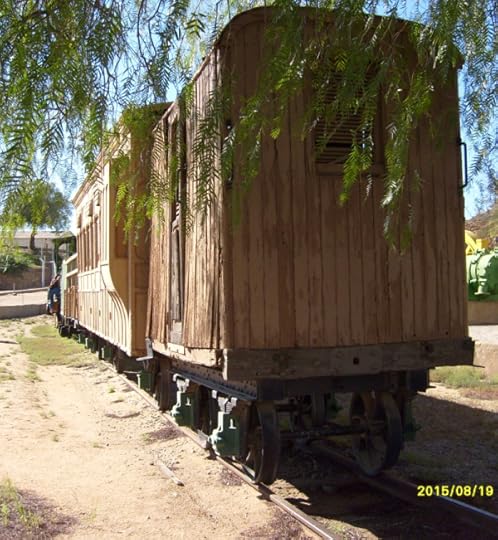

We went on to Nababeep, another copper-mining town, which had a mininbg museum. We saw an engine, a coach and a couple of wagons from the old narrow-gauge railway that had run from the copper mines to Port Nolloth on the coast. They were rather badly weathered from standing for 60 years in the open, and looked as though they would deteriorate more.

Mining museum at Nababeep, Namaqualand, with train that took copper ore to Port Nolloth on the coast. The line closed in 1952.

The gauge wasn’t as narrow as I had expected, perhaps 2′ 6″ or even a metre, certainly larger than the standard 2′ gauge one found in other parts of South Africa. Inside the museum were some photos of it in the days when the ore trucks were hauled by mules, and there were also samples of the ore-bearing rocks.

Narrow-gauge train at Nababeep

We left Nababeep at 15:30, having travelled 367 km from Augrabies, and drove straight to Kamieskroon, stopping on the way at Arkoep Spruit to take photos of some fields of flowers. It was 16:30, and the flowers were beginning to close. We reached Kamieskroon at about 5:00 pm, and found Cosy Cottage,

where we were to stay, without any difficulty, and waited until a bloke came with a key to let us in. It had a TV, and we watched the end of a cricket match between South Africa and New Zealand, which we eventually won by 20 runs, though it should have been by more, only there were a lot of dropped catches. It was a cilly evening, reminding us that winter was not quite over yet, in spite of all the spring flowers we had seen, and we lit a fire in the cottage