Billy Coffey's Blog, page 36

October 29, 2012

My ghost story

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I don’t mind saying I’m a Halloween guy. Always have been. I know, I know—nowadays Halloween doesn’t seem like the sort of thing Christians should be associating themselves with. You have your zombies and your witches and it all seems so . . . un-Jesus-y. While that seems true enough to me on one hand, on the other I’d argue that the spirit of Halloween serves an important purpose. It’s a reminder that not all is well with this world. That drifting along the outer edges of our bland, normal lives is a darkness that but for the grace of God would consume us.

I believe this. I certainly do. There is a value in being afraid of those things that go bump in the night. Because there are things. And sometimes, they do go bump.

Part of the allure of the South is that there are ghost stories everywhere. Every small town, every mountain, every holler, has its dark places. My town is no different. And so in the spirit of Halloween, I’ll give you my own ghost story, such as it is.

The Wenger home still sits in a wide expanse of overgrown grass that is surrounded by acres of corn, no more than a hundred yards from the railroad tracks. My mother grew up on the farm next door and still remembers when the home was occupied. A brother and two sisters, each of them completely insane. The story goes that they all got into a fight one dark night. Things happened, as they always do. All three were found dead. Knifed. I don’t know if that’s true. People still say there is blood on the walls of the Wenger home. I don’t know if that’s true, either. I never had a mind to go and find out myself.

The home has been empty ever since. Well, empty of people. The ghosts, though? Well, that’s another story.

The Wenger home is still a popular spot come Halloween, especially with teenagers who show no compunction about parking along the road and trudging through fields and over railroad tracks. There are stories a-plenty. Never believed them myself. Until I took a girl by there one night.

We never made it to the house (I wasn’t, and still am not, that stupid). In fact, the Wenger home was that last thing on my mind. But as we drove by, my eyes drifted across those fields to where the house lay, and I saw a light in an upstairs window.

A red one. And it wasn’t shining as much as it was . . . glowing.

I stopped along the road, my date in the seat next to me and my car idling in drive, and I will admit I was scared even if I was determined to show her I was not. We watched that light for as long as it took for me to tell her about the Wenger family and their untimely deaths (and yes, the closer she got to me, the more I embellished). It was unsettling, seeing that light. But it was still okay, as the field and the tracks were still between us.

But then something happened. One minute we’re staring at that light, and the next we see a black figure ease its way from the right side of the window to the left. It stopped and turned. Facing us. Looking at us.

My date screamed. I screamed. My right hand jerked and I hit the gas, and what was once scary was now downright terrifying. Because my foot was to the floor and the engine was running, but we weren’t going anywhere. And that . . . thing . . . in the window was still staring out at us.

And I knew—without a single doubt in my mind—that we were both going to die.

Of course, we didn’t die. What smarts I had left were enough for me to see that when I jerked my hand I’d accidently threw the gearshift into neutral. I remedied that and we tore off, leaving whatever was in the window behind.

It was almost a year before I drove past the Wenger house again. And I made sure it was during the day. And I made sure that whatever I did, I would not look.

That’s my ghost story. Now sure, what we saw that night was likely nothing more than a hobo who’d jumped the train and decided to bed down in an old abandoned house for the night. That seems right. Seems logical.

But between you and me, I still like to think it wasn’t.

October 25, 2012

Looking back

A friend of mine is drowning in ancestral paperwork. Books and papers are strewn across the floor of his study. Piles of legal pads are stacked at his desk. And a giant world map hangs on one wall with brightly colored stickpins inserted not only into various countries, but specific parts of those countries.

He’s been at this for years, he says. And there’s no end in sight. It’s tough work, hard work, but ultimately very rewarding. He’s slowly gathering the pieces to the puzzle of his past, trying to answer the very riddle that we all at some time ponder:

Where do I come from?

He told me that as a child he found an old family Bible in his grandmother’s house. Inside were the names of her parents and grandparents, and theirs, and theirs, stretching back almost two hundred years. The writing was faded and the pages were yellowed, but he was captivated. Like rolling down the window of a speeding car to take one look back before the next curve.

Sadly, there were just the names. No locations or dates. And as his grandmother was elderly, she could unfortunately offer little help in the way of more information.

That Bible now sits on his bookshelf. A keepsake and a reminder, one that says this is where it started.

He’s Googled and Yahooed. He’s written letters to both our government and foreign ones. He’s corresponded with researchers and genealogists. And he’s uncovered much.

So far as he can tell, he can trace his family back to medieval Italy. Rome, to be exact. His ancestors were quite wealthy. Landowners and artists and poets. And even statesmen. Powerful people. Important people.

He likes this. He’s proud of his ancestors and their position in life. He may be a simple plumber, but he comes from good stock.

Me, I’m a little fuzzy on the history of the Coffey name. My particular branch came to this country in the mid-1600s, mingled with some Cherokee blood, and settled in the Shenandoah Valley. Before that they were mostly Irish and Dutch. Fishermen, from what I can tell, and farmers.

I could dig deeper of course, and someday maybe will. But the truth is that I’m not concerned about the more affluent members of my family tree. I don’t care about landowners and statesmen.

I want to know what cannot be known. I want to know about those fishermen and farmers. The Nobodies.

The ones who carried on my family’s name despite the poverty and the gruel and the taxes paid to oppressive kings. The ones who had to endure sickness rather than be treated for it. The common ones who lived a common existence and dared sail a perilous expanse of water to start over and live better.

I think of them often. And I often wonder if they thought of me.

Did they pause with their hand on the plow or the net to ponder if their name would still be uttered in this world a hundred generations later? Or did their gaze only go so far as the next row of crops or the next wave over the bow?

Was I as fuzzy and mysterious to them as they are to me?

I spend a lot of time convincing myself that only now matters. Only here. This. But as I continue on through my life, I’m finding that a little difficult to accept. Now isn’t the be all and end all. It is the only moment we truly possess, but not the only moment that truly matters. Because I am the result of many moments and many decisions that mattered to people with whom I share a common bond. And those who come after me, my children and their children and theirs, will be the results of my own moments and decisions.

It is, without a doubt, a heavy burden we bear. We, you and I, stand upon the cusp of history. Thousands of years of ancestors have led to us, and perhaps thousands of years more depend upon us.

Not to be powerful and important.

But merely to endure.

October 22, 2012

The second biggest lie

Being a parent of young children is all about deciding which parts of the world you let in now and which you keep out as long as possible.

For instance.

News? Out. There is no good news. News is meant to depress people. But Sunday morning comics is in. Comics are meant to make you laugh.

Lady Gaga? No. Phineas and Ferb? Yes.

Pro wrestling? Not hardly. But baseball can always provide both quality entertainment and much education.

You get the idea.

This applies to all things spiritual as well. God and Jesus and angels are definitely in, but the darker side of theology goes unmentioned. My kids don’t know what hell is. Or demons. They don’t understand that there are some people in this world who hate their faith and them for having it. The world is a nasty place. I figure part of my job for now is to do all I can to keep that nastiness away. They’ll find out about it all sooner or later.

And maybe sooner.

Our nighttime routine was interrupted yesterday evening by this inquiry from my daughter: “Daddy, who’s Satan?”

The question caught me by surprise. If hell and demons were temporarily off limits, then certainly Satan was, too. Ten-year-olds have fantastic imaginations. Having the thought of a horned and pitchfork-tailed demon rolling around in her mind would make for some long nights.

But what could I tell her? That Satan is the embodiment of evil? That he is darkness so thick that you had to brush it away with a hand? That he is a fallen angel who prowls the earth in search of souls to murder?

No way.

“Daddy?” she said again.

“Um…” I said. “Well, Satan is (someone? something?) bad.”

“The baddest?”

“Yes, the baddest.”

She thought about that and said, “What makes him the baddest?”

“The Bible says he’s a liar,” I told her.

“Daddy, everybody lies,” she retorted. “Even me.”

I decided not to pursue that last little bit of information and instead file it away for later. I really wanted to know what she had lied about.

“But he’s the worst liar ever,” I said.

More thinking. “What’s the worst lie he tells?”

“That God doesn’t love you.”

“I know God loves me, Daddy,” she said.

“That’s good. But maybe one day you’ll start thinking that isn’t true. If that happens, then you just remember that’s just a big, fat lie.”

She nodded and then asked, “What’s the second?”

“The second what?”

“What’s the second biggest lie he tells?”

I opened my mouth to answer, and then closed it. What’s the second biggest lie? I had no idea. I’d never really thought about it. To me, there had always been the first and then the rest. Ranking them beyond that seemed a little unnecessary.

But as I sat there and stared into her eyes, I thought about my life and all the lies I had been told. And then I thought about the lies we’ve all been told.

The best falsehoods are the ones that aren’t told to us as much as they are felt by us. One we accept as truth because that’s what the evidence states.

Those we fall for every time.

It’s easy to lose sight of who we are. Our mistakes and regrets are piled upon one another as a monument to our failure. Stacked high up, blocking the sun. And the Son. It’s hard to see the light when you’re standing in your own shadow.

We carry so much, don’t we? So much knowledge of not only what we’ve done, but what we’re capable of doing. That bad in us is so much easier to see than the good. We dwell upon the depths to which we can plumb but never give thought to the heights to which we can ascend.

There is a holy spark within us all. The thumbprint of the Almighty is stamped upon our hearts. There is a righteous power within us all to rise above where and who we are to become better and more. Too often we limp through our days when we should walk upright, all because we deny the great truth of our existence—we are more than we appear.

“Daddy,” my daughter said again, “what’s the second biggest lie?”

I tucked her beneath the blankets and kissed her forehead.

“That we are all ordinary,” I said.

October 18, 2012

Lightbulb moments

image courtesy of photobucket.com

One of the tenets of country folklore is the belief that people die in threes. It’s a tenet so ingrained around here that there is an influx of patients to the doctor’s office whenever a longstanding member of the community passes on. No one knows who will be next, and they don’t want to take any chances.

I’m not sure how much truth there is in that conviction. People might die in twos or fours just as often as threes. But I do know this—light bulbs die in threes. At least in my house.

It began last week with the light in my son’s bedroom, which much have died a quiet and peaceful death sometime in the night. He rose out of bed the next morning, flipped the switch, and…nothing. A few days later it was the light above the kitchen sink, which yelped a pop! when my wife tried to turn it on.

Then last night I came upstairs to my computer and fumbled for the light switch behind the door. Just as I flicked the switch upward, blue and white sparks sprayed from the ceiling fan in a burst of violence that actually managed to shatter the light bulb itself. It was quite impressive.

What brought about this light bulb mass suicide is beyond me. Our home is not old and the wiring was expertly done. I can only surmise that everything has its life cycle. At some point the odds are in favor of more than one sputtering out at the same time.

The blown light bulb is an exercise in both physics and inevitability. The cause is fairly straightforward: a light bulb’s filament does not evaporate evenly, leaving it to develop spots over time that are thinner than others. Since the electrical current heats the filament evenly, the thin spots heat more quickly. The result is a pop! and then darkness.

What struck me as I stood there staring at the bulb was my reaction, which so happened to be the one my son and my wife had, too. Not anger or frustration. Not even disappointment.

Confusion.

Because a light is supposed to turn on when you flip the switch it’s connected to. I had a vast amount of experience to back that assertion. It was one of the few of my life’s givens, so much so that I’d perform the act without giving it a second thought. Flipping a light switch is faith at its purest, the embodiment of if-I-do-this-then-this-will-happen.

It’s easy to take such things for granted, though. I’ve spent my day keeping track of every light I turned on, from the bathroom light when I first got up to the light in my office nearly sixteen hours later. My total thus far? Thirty. I’ve turned thirty lights on today, and none of them has broken.

I’m already taking the light switch for granted again.

So maybe I needed the gentle reminder that all those everyday things I put my faith in are neither permanent nor flawless. Things that go well beyond light bulbs and into the very center of my life. The job I have today may go pop! tomorrow. The savings account to cushion a fall may be pulled from beneath me just before I land. And the very ones I love most may be the very ones who let me down the hardest.

That’s the nature of life, the consequence of living in a world that isn’t quite what it should have been. We’re all searching for something to hold onto, something that will give us a sense of security and knowing, and yet everything we have is like that light bulb—at some time and in some way, they will all fail in an impressive fashion and leave us standing in the darkness. Which is all the more reason to place more trust in God than man.

October 15, 2012

Embracing normal

image courtesy of photobucket.com

“Daddy, are we rich?”

My daughter at the dinner table. Which, since school has started again, is quickly becoming more of a place to discuss Important Things than eat.

Fifth grade paints a broad stroke of a child’s future life. I’m not just talking about things like math and history and spelling. I’m talking about where children fit into the scope of society. My daughter is in a classroom of about sixteen. That means there are fifteen other children who might be her age, but have little else in common with her.

Some have no father at home, and some have no mother. Some are of a different color. Some are from other parts of the state. A few are from other states completely.

Some have accents. Some wear glasses. There are the tall and the short, the big and the small, the smart and the not so much.

There is a mixing of ideas and life experiences, even if those ideas are still relatively undeveloped and those experiences relatively few.

The result of all this mixing and matching is that each of her classmates are spending quite a bit of time trying to figure out not only where they fit in, but why and why not.

One of her friends had a new toy to show the other day. A nice toy. One that my daughter herself had expressed an overwhelming desire to obtain every time the commercial appeared on the television. Christmas maybe, she’d told me.

I told her it was too expensive and it was the sort of thing that fell under Santa’s jurisdiction rather than her father’s. So when she saw what her friend had just gotten at Target, the first notion in her mind was envy. The second was whether that meant her parents had less money than her friend’s.

The boy she saw during recess was quite the opposite. He had no toys. None that he had chosen to sneak into school, anyway. His clothes were worn and a little dirty, and his shoes looked as if they were too small. Like my daughter, his parents didn’t seem rich either. But unlike her, he seemed to have even less.

So: “Daddy, are we rich?”

The thought occurred to me to put a spin on her question. I could use the We’re Rich In The Things That Matter speech. I could say that we had things like love and togetherness, things that make us rich but can’t really be spent at Target.

Or I could use the We’re A Lot Better Off Than Most speech, too. I could say there were a lot of people in a lot of places who didn’t have a house to stay in or good food to eat or even a television to watch. People who would consider us very rich indeed.

But neither of those options seemed right at the time. There are moments when a lesson is in order and moments when the truth begs to suffice. I decided that honesty would be the best policy.

“No,” I told her, “we’re not rich.”

“We’re not?” she asked.

“No.”

“Then are we poor?”

“No.”

She paused with a spoonful of mashed potatoes in her hand. “Then what are we?”

I shrugged. “We’re normal.”

“Oh,” she said. “Okay.”

Thus ended our conversation.

Being normal was okay for her. No big deal. She wasn’t rich, which may have been a disappointment. But she wasn’t poor either, which may have made her feel better. She was in the middle. Neither/nor. And that was fine.

I hoped she would always have this opinion of things. I mean that. There were people in the world who wanted so badly to be more than they were that they forgot they were actually pretty good to begin with. And I also knew people who were so convinced that they could do nothing that their lives became little more than self-fulfilled prophecies. I hoped that she would grow up to be different, that she never got so ambitious as to forget her blessings and never so complacent as to forget that she could always both be and do more.

So let her reach for the stars, I say. I think we all should. But it’s always helpful to keep our feet firmly on the ground, too. It’s a precarious position, our normalness. It takes some skill to keep from tipping over one way or the other.

October 11, 2012

The journey and the destination

image courtesy of photobucket.com

My family and I took a long trip over the weekend, long being a drive of nearly an hour and a half. Those who have kids understand that five minutes in the car with them can at times be too much. There is crying and complaining, spills and messes, and a seemingly endless chorus of “Are we there yet?” and “How much farther?”

That was our ride.

And this even with all the newfangled trinkets designed to make an hour and a half ride more comfortable. Things like DS games and DVD players. These things do well and good so long as they remain charged and the headaches do not start, which, in our case, lasted a grand total of forty minutes.

With aspirin handed out and the radio turned down, all that was left were those old fashioned games that helped me through some long rides of my own once upon a time. There was the ever-popular I Spy game, won by my son. My daughter won the out of state license plate game. They each tied at seven playing the game where you get the truckers to blow their horns.

But even after all that, there was still a half hour’s worth of driving to go. With the DS games dead, the DVD players on life support, and the radio station that seemed incapable of playing nothing but Van Halen’s “Panama,” there was nothing for us to do but wait.

“Won’t be long,” I promised. “We’ll get there soon enough.”

I knew that wasn’t exactly right. And I’ll say that while I said it, I was thinking of the drive back. Of going back there and getting out of that cramped car. Unbuckling my belt and stretching my legs and looking at the sun and hearing it welcome me home.

I’ve heard that life is all about the journey. The destination is not just irrelevant, it spoils all the fun. Sounds like a romantic notion. And just as most romantic notions, that one’s just plain ridiculous. What’s the use in going if you have nowhere to go? Why start when there is no end?

As I drove, road leading toward a horizon that only yielded more road, I decided there was also something else that could be described as a journey rather than a destination.

Hell.

My sour attitude didn’t last long. And of course I don’t want to imply that spending ninety minutes in the car with my family was hellish. It was not. It only seemed that way for a bit.

But after that bit I began to realize how apropos our drive was to life itself. Because to a certain extent we are all on a road. There are dips and curves, mountains and valleys. There are times when extreme concentration is necessary and times when everything seems flat and boring. Regardless, the point is to keep going. There is no heading back, not for any of us. The road is forward. It always shall be.

We have company along the way. Family and loved ones that sometimes get on our nerves but most times we know we could never live without. They are with us and we them, even though each has his or her own vantage point, his or her own place.

There are others too, sharing a bit of the road with us while we travel. Some pull alongside for a long while and become familiar. Others are there and then gone, never to be seen again. It’s a big road, life, and we all go at our own pace. Some are in a hurry and others take their time. But regardless, we all will reach The End someday.

The End. Oh yes. Because while the road may be wide and long, there is no room for existential thoughts of a journey without a destination. We may be given the freedom to ride as we wish, to be cautious or not, to ride with the windows down or rolled up tight, but that freedom ends there. We were not given the choice to be upon this road, and we are not given the choice to stay upon it.

And if that causes us grief, I say it shouldn’t. I say I look forward to that day when my ride is done. When I can unbuckle my seatbelt and step outside. I will stretch my legs and stare at the Son, and He will say welcome home.

October 8, 2012

Gums and the never ending field trip

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Took a day off from work a while back to do something I haven’t done in about twenty years—go on a field trip. My daughter’s class was to spend the day at a local university, and she was psyched for some Daddy Time. I was pretty psyched my own self. That goes to show you how long it’s been since I’ve been around about sixty third-graders.

Any thought that our time together would be both quiet and alone was quickly put to rest with the appearance of one of my daughter’s friends, who sat with us on the bus. The little girl’s name still escapes me, though I’m sure she mentioned it. Many, many times. Mentioned quite a few other things as well. Many, many times.

Country folk like me (the men in particular) tend to shy away from calling people by their given names, opting instead for nicknames of their own creation. There is an art to this. A good nickname is comical but not mean, and usually connotes a certain physical attribute or facet of personality. I tell you that so I can tell you the nickname I’d given my daughter’s friend by the time we hit the interstate.

Gums.

Because she never shut up.

Never, ever.

The trip began with me in the middle of a bus seat designed for two small children at the most. Ours contained two small children and one big redneck. Gums began her questions early and often:

“Are you the writer?”

“You don’t look like a writer.”

“Why do your jeans have holes in them?”

“Why don’t you have any hair?”

“Can I have a copy of your book?”

“Why don’t you shave?”

“Is that your notebook?”

“Can I see?”

That was the moment I paused and asked my daughter if she would mind switching seats. There would be more room for us if I was at the window, I told her. It was a lie, of course. But the truth was that I wanted to use her as a sort of human shield, and I couldn’t tell her that.

For her part, Gums didn’t mind. She could talk across my daughter to me just as easily. I had a headache the size of Texas by the time we got off the bus.

We made our way into a ballroom, the setting for most of the day’s activities. Seven people to a table. My daughter sidled up to me in her chair. So did Gums.

Third grade fieldtrips seem to revolve around crafts. I’m not a craft sort of guy. My little girl is (thankfully), though I still had to pitch in with the glue, the tape, and the stapler. Likewise Gums, who managed to staple both herself and me to the mask she was making before we finally got everything straightened out.

That’s how most of the day went, my arms tired from my daughter clinging to them and my ears tired from the chorus of “Daddy, look!” and “Hey Mr. Coffey, c’mere!” It didn’t take me long to realize I’d never make it as a teacher.

The ride home was interesting. Me mashed against the window, my lap filled with a ceremonial mask made out of construction paper and fake feathers and a drum make out of two popcorn containers. Mass hysteria from the seats behind me, teachers fighting the good fight to keep everything calm.

My daughter laid her head on my shoulder. I saw her smile, and I knew the day had been worth it. A smile from her is always worth it.

Gums peeked at me and made a come-here motion with her finger. I leaned in close, ready for whatever questions she had this time. She had none. Instead, she leaned her mouth toward my ear and whispered, “I wish I had a daddy like you.”

Oh my.

I didn’t mind Gums talking the rest of the ride home. And to be honest, I kind of felt bad for nicknaming her Gums (though she seemed to enjoy it quite a bit).

But I learned a lot on that field trip. Not just how to make ceremonial masks and drums, either. I learned a little something about kids, too.

About how they need something else besides food, water, shelter, and love.

They need attention, too. They need adults looking at them in the eyes and listening to the things they say. And say, and say…

October 4, 2012

Hit the redneck

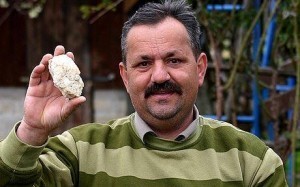

photo of Radivoje Lajic from telegraph.co.uk

You could say Radivoje Lajic and I have a few things in common, at least on the surface.

We’re both country boys for one, though what I call country happens to be the mountains of Virginia and what Radivoje calls country happens to be Gornji Lajici, a small village in northern Bosnia. We’re both content to live our own lives and mind our own business. And then there’s the fact that deep down, we both just want to be left alone. We want our lives free of drama and spectacle. We want to quietly go on our way and just keep doing what we’re doing.

Problem is, that doesn’t seem to happen very often with Radivoje. And sometimes it doesn’t happen very often with me, either. Things get in the way. Specific things.

In Radivoje’s case, it’s the aliens who won’t leave him alone.

Since 2007, Radivoje’s small house has been hit six times by meteorites. He has the space rocks to prove it, too. Experts at Belgrade University have confirmed them all as genuine. He even sold one of them to a university in the Netherlands so he could put a new steel girder reinforced roof on his house. He was tired of patching all the holes.

For their part, scientists are still trying to figure out how and why poor Radivoje has been forced to endure this. The odds of anyone getting hit by a single meteorite are about 0.000000136%. The odds of getting hit by six of them? Incalculable.

There is some speculation that either his house or his town sits on some supercharged magnetic field, but nothing has been proven. And even if it was, that wouldn’t explain the fact that all of this seems to happen only during a heavy rain. Never in the sunshine.

A mystery, the scientists say. But not to Radivoje. He knows what’s going on. To him, it’s pretty obvious:

“I have no doubt I am being targeted by aliens. They are playing games with me. I don’t know why they are doing this. When it rains I can’t sleep for worrying about another strike.”

Funny, yes. Funny to me, anyway. I don’t know why this is happening, but to think aliens are floating up in space playing a game of Hit the Serbian seems a bit of a stretch.

But then I thought it over and decided that maybe if Radivoje has his facts wrong, then so do I. Because if you substitute “aliens” for “God” in his quote above, you might just have me.

There are times in my life when I feel like God is targeting me. Lots of times. Many more than six. I suppose in that regard, Radivoje’s gotten off pretty easy.

I’ve been known to believe that God plays games with me. He’ll dangle some blessing right in front of my eyes and then snatch it away the second I reach out for it. He’ll answer little prayers like getting me a good parking spot at the mall but not big ones like not letting my kids get sick. And there are always those infernal lessons He’s intent on teaching me, things like patience and humility and trust, things I’m sure will build me up later but always seem to make me feel torn apart now.

To make matters worse, those lessons always seem to come at the worst possible time. Not when my life is sunny, but when it’s raining on my insides. And the rain always seems to pour harder then, because I’m left worrying what He’s going to do next.

“I have no doubt I am being targeted by aliens. They are playing games with me. I don’t know why they are doing this. When it rains I can’t sleep for worrying about another strike.”

I get that. I get it because there are times when I have no doubt I am being targeted by God. He is playing games with me. I didn’t know why He is doing that. When it rains I can’t sleep for worrying about another strike.

I can’t say there isn’t a little bit of Radivoje Lajic’s thinking in me. I have my moments when I think God’s in heaven playing Hit the Redneck. And chances are good that you’ve felt the same more than once about your own life. As for me, I’m going to work on that.

October 1, 2012

Moving on

image courtesy of photobucket.com

An acquaintance of our family recently passed on.

That’s the term we use here in the Virginia mountains, the term I’ve used in front of my children—“Passed On.” I’m fond of that term. It offers an image of moving rather than holding still. This person we knew, he may not be here any longer, but he is elsewhere. Laughing and living still. And waiting, for us.

Neither of my kids seem to be much impressed with “Passed On.” It still means the same thing, they say. Still means DEAD. To them, you might as well call a thing just what it is, and it doesn’t matter if you’re Passed On or Dead or if you’re Making A Trip To The Boneyard, it all means you’re gone and you won’t be back.

So my kids say. And though normally I’d take them both to task for believing such, I’m letting it pass this time. They have other things on their minds at the moment. Big things. Heavy things. You see, this is the first time my children have had to face the fact that sometimes prayer does not work. That sometimes, God says no.

They prayed nightly for our friend’s healing. It was right at the top of the list, the first petition after a good round of thank-Yous. Both of my kids possess in abundance that childlike faith the Bible says moves mountains. But not this time. This time, they are left with the hard truth that sometimes God delivers from death, and other times He delivers through it.

It’s a hard lesson for us all, no matter the age. A harder one, perhaps, is coming in the next months: that lesson of moving on, of having this person they’ve known and prayed over for years slip from their minds. They’ll ponder our friend, they’ll still pray for the family he left behind, but sooner or later dust will turn to dust and the cares of this world will move on. Sooner or later, we all move on.

That moving on is another kind of pain, a different one, yet my children will find it stings just as much.

The parenting books aren’t much help when it comes to situations such as these. Nor grandparents, nor pastors, nor close friends. They’ve all told me much the same—that life has a way of carving itself into you and hollowing you out. It hurts (oh yes, it most certainly hurts), but once that carving is done you find that the very God who once said no now says yes, and those deep grooves are filled with a grace and a love that makes you whole again.

I will tell my children this. I imagine it will not do them much good just yet.

But it will later. Oh yes, it will indeed.

September 26, 2012

Stemming the tide

image courtesy of photobucket.com

You could call Jimmy Henderson a lot of things—and many people have—but everyone agrees that above all, he is prepared. And in his mind we all should be, given the evil that lurks about.

Jimmy keeps an eye on all that malevolence. Drive by his house, and you’ll see no less than four newspaper boxes. His magazine interests range from the far left of the political arena to the far right, including such publications as Field and Stream and Backwoods Living. “Just in case,” he says. “Because you know they’re coming eventually. They’re coming for us all.”

In Jimmy’s case, They is the government (or some secret shadow puppet government, I can’t really remember which). He weathered the Carter administration well enough and barely got through eight years of Clinton, but Jimmy thinks he’s met his match with the current resident of the White House. He’s seen the documentaries and read the books, and he’s genuinely scared. So much so that Jimmy’s starting to worry that his Tea Party membership and flying one of those “Don’t Tread on Me” flags in front of his house just won’t be enough to stem the tide.

And he’s not alone. Lots of people are scared now. Bad times breed bad thoughts, and sometimes we see monsters where only shadows lie. For every person like Jimmy who’s convinced President Obama is about to bring down the country, there is another who thought the same about President Bush. There is an inherent distaste for government in most people. It isn’t easy for us to trust those in power, and I think there’s good cause for that. I also think the reason why our country has been so important for so long is because that inherent distrust was shared by the very men who created it.

But to be in power doesn’t necessarily mean to be in charge, and I think that’s where Jimmy’s confused. And I think his fear was born from a sense of powerlessness that can creep up on everyone when we begin to feel as though the world is crashing down. What frightens Jimmy more than black helicopters and government conspiracies is the simple fact that he thinks his voice doesn’t matter anymore. It’s being drowned in the deluge of spin and the shouting in the public square between parties.

It isn’t very often that I delve into the political in the things I write. It’s a subject that’s too touchy, and rarely is there anything of worth that can come of it. But I’ll make an exception in Jimmy’s case, if only because it’s something applicable to anyone, whether liberal or conservative or independent.

It is this:

In this country we have neither king nor queen, merely representatives of our own wills who must abide by the very laws we adhere to. Their jobs are just as dependent upon us as our jobs are upon their policies and committees.

If there is a tide that must be stemmed, it cannot be done through fear and anger or accusations and snipe. It is instead done in the privacy of the voting booth and in the sacredness of our homes. It is done in the raising of our children and the desire to end each day as better people than we were at the start of it.

Because what is true for Jimmy is true for me and for you—in the end, the future of our country doesn’t depend upon what goes on in the White House, but what goes on in our houses.