Billy Coffey's Blog, page 48

September 5, 2011

A weight too heavy to carry

image courtesy of photobucket.com

"Daddy, can you carry this? It's too heavy."

My daughter. She trails behind her a sack of what may be Barbie dolls, or maybe laundry. I can't tell from where I sit. I can, however, tell she's right. It's too heavy.

"Sure thing."

I get up and make my way over, but not before turning the channel on the television. Just in time, too. My daughter craned her neck toward it at just the next moment. She got an eyeful of Sportscenter rather than an eyeful of the latest bloodshed.

I bent down and grabbed her sack—Barbies after all.

"Where'm I taking this?" I ask her.

"To my room."

I nod and shoulder the load. "Lead on, MacDuff."

She takes one more look at the television, says "Sorry about the Yankees, Daddy," and then blazes a path down the hallway toward her room.

"That was Shakespeare, you know," I tell her. "The MacDuff thing."

Unimpressed with my literary knowledge, she merely nods and says, "That's nice." I know something else is on her mind. Something else is always on her mind. I deliver Barbie and the rest of her clan to the safety of her bed, ask her if there's anything else I can do for her, and park myself back in front of the television.

I push the button on the remote control that says Previous. Sportscenter disappears in a blaze of pixels that reforms into the rest of the evening news.

It's a habit I've repeatedly tried to break, this news watching. I've reached the point where I can bear no more and have decided to test the theory that ignorance truly is bliss. Little of what I see on the television is ever felt in my quiet corner of the world. Things here go much as they always have, slowly and with little change. But a part of me feels it is my responsibility to know what's happening. There is a sense that I must bear witness to these times, if only to pray that God will deliver us from them.

I see a pair of eyes peek at me from around the corner, small eyes full of questions. They grow into my daughter's face. I push the button again. Back to sports.

"What you need, sweets?" I ask.

"Nothing."

"Sure?"

She is not, and so walks into the living room and sits beside me. Says, "What were you watching, Daddy?"

"Just some sports."

"No," she says. "Before."

I have the feeling she knows exactly what I was watching, which means I can either lie or tell her the truth. It's not good to lie to your children. Necessary at times, but still not good.

"I was just watching a little of the news."

"How come you always turn the news off when I'm around?"

"I don't know," I tell her. "You'd probably think it was boring stuff." It's a lie. Like I said, such things are necessary at times.

"I don't think it's boring. I like to know stuff."

She leans her head on my shoulder and we laugh at the commercial on the screen. Mine is a tired chuckle, the sort that's given more out of expectation than genuine feeling. I suppose my thoughts were more on the newscast than the humor. Hers, though? Complete and joyous, a laugh unencumbered.

The laugh of a child.

"You know that sack I carried to your room?" I ask her. "How it was too heavy for you to carry?"

She nods against my shoulder.

"That's sort of why I don't like you watching the news. Your sack was too heavy for your muscles, right?"

Nod.

"Your spirit has muscles, too. Some things on the news, they're too heavy for you to carry right now. That comes later, when you're older and stronger. Then you can carry all of that. But for now, I think you should just carry the lighter things. I'll carry the heavy things for you."

I kiss her on the head, a sign she understands means that's all I can stay. My daughter lingers long enough for the commercials to end, then she skips back to her room and her Barbies.

I don't know if she understands what I've just told her. Maybe that is too heavy for her as well. A part of me hopes it is.

My finger rests on Previous, and I realize it's done so by habit. News, always news. Another set of eyes from the hallway, these the smaller ones of my son. He asks if we can watch cartoons. I tell him yes.

There will be no more news tonight, and I decide that's a good thing.

Because there are still many things even too heavy for a father to carry.

***

This post is part of the One Word at a Time Blog Carnival: Innocence, hosted by my friend Peter Pollock. To read more on this topic, please visit him at PeterPollock.com.

Share and Enjoy:

August 31, 2011

Snapshots

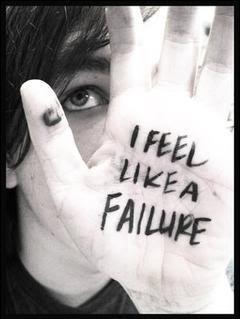

image courtesy of photobucket.com

(Originally posted January 22, 2009)Part of my job entails keeping up with the comings and goings of about one thousand college students. All have arrived at the doorstep of adult responsibility, and all must walk through as best they can. Some glide. Others stumble.

Students are constantly arriving, eager to fill their hungry minds and lavish themselves in newly found freedom. Others have found that those freedoms can lead to all sorts of trouble and so are on their way back home.

The status of these students must be cataloged and recorded and then shared with various departments by way of email. Very businesslike, these emails. Concise and emotionless. But they are to me snapshots of lives in transition.

One such message came across the computer yesterday. The usual fare—student's name and identification number, and her status. But then there was this:

She will not be returning and is withdrawing.

She failed everything.

As I said, businesslike. Concise and emotionless.

I've always had a problem with brevity. I have a habit of explaining a small notion with a lot of words. Which I guess is why that email struck me so hard. Here was three months of a person's life, ninety days of experiences and feelings, summed up in three words:

She failed everything.

Though I don't know this person, I can sympathize. I've been there. Many times. I know what it's like to begin something with the best of intentions and an abundance of hope, only to see everything fall apart. I know what it feels like to realize that no matter how hard you try, you just can't. Can't win. Can't succeed. Can't make it.

I know what it feels like to fail. Everything.

When my kids were born, I wanted to be the perfect father. Always attentive. Never frustrated. Nurturing. Understanding. And I was. At first, anyway. But things like colic and spitting up and poopy diapers can wear on a father. They can make a father a little inattentive, not so nurturing, and very frustrated. So I failed at being the perfect father.

Same goes for being the perfect husband, by the way. I failed even more at that.

And I had the perfect dream, too. What better life is there than that of a writer? But no, that one hasn't gone as expected. Failure again.

At various times, struggling through each of those things, I've done exactly what young girl in the email did. I withdrew. Not from college. From life. I gave up. Surrendered. Why bother, I thought.

But I learned something. I learned there's sometimes a big difference between what we try to do and what we actually accomplish. That many times we don't succeed because there's an equally big difference between what we want and what God wants.

That failure is never the end. It can be, of course. We can withdraw and not return. Or we can learn that it is only when we fail that we truly draw near to God. We can better understand the that our prayers must sometimes be returned to us for revision. Not make me this or give me that, but Thy will be done.

I've failed everything. Many times.

Also remade.

I may not have made myself the perfect father, but God has made me a good dad.

I may not have become the perfect husband, but God has shown me how to be a soul mate.

I may not write for money, but I do write for people.

Failure has not been my enemy. Failure has been my salvation.

Our lives have broken places not so we can surrender to life, but so we can surrender to God. And failure will hollow us and leave us empty only so we may be able to hold more joy.

Share and Enjoy:

August 29, 2011

A precipitous balancing act

image courtesy of photobucket.com

This past weekend, I got the hammock out.

Strung it between two trees in the backyard under a warm August sun. Just me and the sky.

There's a lot to be said for a good hammock. Back when I was a young and single man, the bedroom of my tiny apartment was graced with one. I had no bed, I had a hammock. And I rocked myself to sleep every night dreaming I was on some warm and secluded beach far away. When my girlfriend agreed to become my wife, she said the hammock had to go. It was just as well. Eventually, you have to put the old things aside in favor of the new.

But sometimes those old things come back, if only for an afternoon. It had been a long, difficult week. I needed a break. My sunny disposition had turned sullen, and I had a serious case of the Grouchies. I needed to rock myself and dream of warm beaches to chase the pessimism away.

The knots were good, the hammock threads still strong. I moved to one tree and set my leg in the middle.

Leaned over.

Lifted my other leg off the ground.

Fell.

And by that, I mean tumbled. Hard. I did a complete three-sixty in the air and landed on my neck. I couldn't breathe for thirty seconds.

Tried it again—setlegleanoverliftleg. Fell. It was an even worse fall that time, so bad that I actually did see warm beaches and thought I'd died.

The third attempt almost never happened. By then I was reciting the old adage of fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice, shame on me. To the best of my recollection, there was no fool me three times because no one in history had been so stupid to try it again.

But I did. I really wanted to chase that pessimism away, and I really wanted to do it in my old hammock.

I moved to one tree and set my leg in the middle.

Leaned over.

Lifted my other leg off the ground. Slow, nice and slow, and…there. I'd made it.

Wasn't easy, though. I'd forgotten that the thing about sitting in a hammock was just how difficult it was. Whatever stability you may find won't last long. A breeze will kick up or you'll sneeze or you'll scratch a sudden itch, and for the next moments you'll be fighting both gravity and inevitability.

The trick isn't just learning how to get into a hammock, the trick is learning how to stay there. How to keep your balance. And the way you do that is simple—realizing you can tumble at any moment. You can tumble and you can have no understanding of why.

The best way to handle that knowledge, to maintain that balance, is to accept it and tuck it into a corner of your mind. Because the only way you can keep yourself from falling is by understanding that falling is a perpetual possibility.

Sounds pessimistic, I know. But it's true. I laid there in that hammock for three hours counting the clouds and never fell once, all because I kept in my head I was always one twitch away from doing so.

I dreamed of faraway beaches, places where stress was a foreign word and time didn't matter, where the sun was always warm. And yet I was allowed to dream of all that optimism because of the cynicism that held me in place.

Which got me thinking. Maybe the sadness we feel can teach us just as much as the happiness we want. Maybe God at times uses our doubt more than our faith. Maybe the best will happen and maybe the worst, and maybe the best we can hope for in this life is a strange and mysterious mix of the two.

I suppose we'll all find out in the by and by. But for now, I'm sticking with this—the best way to rock away a warm afternoon is to know it can all tumble down.

Share and Enjoy:

August 24, 2011

This teeter totter life

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I spent much of last Friday at the hospital with my wife, who had been feeling particularly ucky of late. The doctors had (and as I write this have) no idea what's wrong. Tests were in order. So off we went, her to be poked and prodded for two hours, and me to pass the time in the waiting room.

As I am not a fan of feeling ucky or being poked and prodded, hospitals rank just above funeral homes on my list of Places I Wish Not To Go. It isn't the germs that bother me, not the echoes of coughs or the abundance of wheel chairs and gurneys. It's the despair, I think. That thick dark cloud of inevitability that seems to hang over everyone and everything. Going to the hospital makes me confront the fragility of life. That's something I'd rather not consider.

I brought enough work to keep my mind off things. I knew the waiting area had a television, but the possibility of watching Sportscenter all morning quickly evaporated when I was told the only channel offered was HGTV (according to the nice old lady with the clipboard, anything else may be construed as "controversial.") I had a notebook—1,000 words a day every day is what I was taught, even when you're sitting in a hospital—and my i-Pod—the new Trace Adkins album? Gold.

I was ready, oh yes I was. The only pondering of life and death that day would come from my characters rather than myself. Yes sir, I was going to mind my own business.

The only thing I didn't take into account was that there would be other people in need of the sort of modern medical technology that only the local hospital's radiology department could provide. Though the waiting room was relatively empty when we arrived, by the time my wife's name was called, it was nearly full. And five minutes later, I had company.

The woman who sat down beside me with the crutches looked eighty but swore she wasn't a day over fifty-seven. We exchanged hellos and I resumed my scribbling. She asked what I was doing. I said work (never say you're a writer, I was taught that as well). She nodded and leafed through a ten-month-old magazine for exactly thirty seconds, at which time she sat it back down on the wooden table between us and asked what was wrong with me.

"I don't think you'd have the time," I joked.

She chuckled and touched my arm—eighty-year-old women who swear they're not a day over fifty-seven love to touch arms—and said, "I mean what brings you here?"

"My wife's getting a once-over," I told her. "You?"

She tapped the crutches and then felt her leg. "Busted myself. Fell down the stairs. I blame the cat."

"Cats are evil," I said.

She gave me a knowing smile.

"Cats are not evil," said the woman across from us. A sling was wrapped around her neck which made her left arm form an L. She looked as though she were leaning on an invisible fence post. "I have three, and they're darlings."

"Bet your cat did that to your arm," I said.

"Nope. I fell out of a wheelbarrow."

"Pardon?" the woman beside me said.

"Yep, wheelbarrow." She looked down at her arm and up to us. The look on her face was a mix of embarrassment and pride. "My son said I was too chicken to let him push me down the hill in it. Guess I showed him, huh?"

"Guess so," I said.

The man to her left had been listening this whole time under the guise of being immersed in his sports magazine. I doubt any of us thought he was actually reading it. Hard to do with a neck brace.

"I did that once," he said. "Made it down our hill just fine. Shut that cocky son of mine's mouth up, sure enough. I don't take chances anymore, though."

"What happened to you?" the old lady beside me asked.

"This?" He pointed to the brace, just in case she were asking of anything else. "I got up off the couch. Seriously. All I did. Felt something pull, just…pop goes the weasel."

I never got any writing done. It was better to sit and talk, I think. Better to be reminded of the fragility of life, that strange thing that seems so hard but is instead so soft. I was reminded of just how clumsy we all are and how we can get hurt even when we take no chances.

Because our existence is but a thin strip of breath upon which we teeter and totter and, eventually, will tumble off.

Share and Enjoy:

August 22, 2011

Farther along

image courtesy of photobucket.com

She and her husband were in the back row. That was the accustomed place for my family and in-laws, as we are numerous enough to require an entire pew unto ourselves. We scrunched in, the seven of us seated at her and her husband's left, careful not to bump her wheelchair.

"I love you," she said, first to my wife and then my daughter. Her words were muffled and childlike, as if spoken in surprise and through a mouth filled with marbles.

"I love you," she said to the couple who approached her. They placed their hands on her shoulders and spoke in calm and deliberate words. They asked how she was feeling, how she was. "I love you," she said again, and the smile on her face said more than her faded vocabulary could.

The preacher—"I love you"—said he loved her right back. He tucked his worn leather Bible under his left arm and took her hand in both of his. I watched as the muscles in his forearm flexed, giving her fingers a light squeeze, praising God.

"I love you."

The congregation settled into the Sunday morning ritual of greeting/prayer/announcement. The pianist then began the opening of the first hymn—"To God be the Glory"—and all but she stood to praise the Lord in song.

To God be the glory, great things He hath done…

The slow movement to my left was hers. She placed one frail hand upon her husband's and bid him to help her stand. He placed his arms around her and hefted her up, steadying her against the gravity that pushed down on her and the mind that worked to make sense of it all. I wondered if this too was the glory of God, a great thing He hath done.

I watched her as she sang, her voice too soft to stand with the others but her lips moving free, mouthing not O perfect redemption, the purchase of blood, but I love you I love you I love you I love.

I watched her, and what I saw was the woman she once was rather than the woman she was now. The Sunday school teacher, the choir member, the woman who organized Bible School in the summer and the Christmas program in the winter, the woman who at the young age of barely fifty had suffered a stroke that erased much of who she'd been and replaced it with a child imprisoned in a cell of flesh and blood. A child who needed help to move and wash and eat and whose vocabulary was condensed to three words.

I love you.

Act II of the Sunday morning ritual contained further announcements and a brief presentation by the church's youngsters. Do not ask me what was said, I don't know. I suppose I should have been listening, but I was watching her. Watching as she eased back into her wheelchair and looked out with bright but confused eyes. Watching as she said I love you to her husband.

We rose for the offertory hymn, this "Worthy of Worship," a congregational favorite. She remained seated this time—she's so tired now, not like before—but mouthed her own translation nonetheless, mouthing

I love you I love, you I love you

where we sang

Worthy of rev'rence, worthy of fear

And I wondered upon looking at her—God help me, but I did—that her sight made me fear God but also tempted me not to reverence Him. What God was worthy of reverence who could allow such a thing to one of His own? To pardon the darkness of this world and allow it to strip this woman down? To leave her a husk of what she once was and call it good?

For much the same reasons I missed the children's presentation, I missed the sermon. The congregation rose. I joined them when I saw that she and I were the only people not standing. Three men stood behind the podium, songbooks in their hands, as the piano began the closing hymn, Farther Along.

I did not sing. Could not. I was watching her instead, still not knowing the Why—it's always the Why that trips me up—but knowing that the fears and worries that once upon a time defined her living did no more. Like her body, her life had been reduced to the most fundamental level, one where Hello and Goodbye and Thank you and Praise the Lord all mean I love you, and perhaps that is what it should mean for all of us.

I joined in on the last refrain:

Farther along we'll know all about it,

Farther along we'll understand why.

Cheer up my brother, live in the sunshine,

We'll understand it all by and by.

Share and Enjoy: