Billy Coffey's Blog, page 39

July 16, 2012

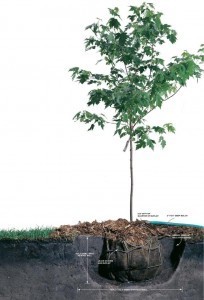

An open letter to the buried

photo by photobucket.com

I’m fortunate enough to get my fair share of emails throughout the day, and from all sorts of people—family, friends, those who are not yet friends but will be, and so on. I like my emails. It’s nice that people think enough of me to drop me a little note to say hello or thanks or please.

Lately, the ones most on my mind are the ones who say please.

As in, Please pray for me. Please help. Please listen.

Though I don’t often do this, I blame the times. It’s the world’s fault, a place that each day seems to spin a little farther from straight and bends a bit more crooked. Life has gotten much more difficult for a lot more people in the last few years. I have sixteen pieces evidence to that fact in my inbox.

There is sickness and death. Jobs lost and homes gone. Hearts broken. Hopes dashed. Love failed. There is fear and anger and sadness. Dark souls and darker futures. And hanging over them, pushing down, is one question that may go unsaid but is never unfelt:

Why is God doing this?

“This” can be best explained by a friend who wrote to say that his job of twenty years would be no longer in less than a month. His house will surely go soon thereafter. His wife cannot work due to health issues, which has already emptied their savings. Their furnace is on the fritz, and the last snow damaged the roof of their home.

“I’m not sure we can pull out of this one,” he wrote. “I feel like I’m being buried.”

I wrote him back as well as the sixteen others. Yes, I said, I will listen. And pray. And help all I can. But then I wondered about all the other people out there who were feeling buried themselves. What would I say to them if they decided to write, too?

I thought about that, which didn’t take very long. I’ve had a lot of experience in feeling buried. So if such a letter would drop into my inbox, this is what I would say in return.

Dear Buried,

It never ceases to amaze me how quickly life can turn. How we can be going along steady and straight and then suddenly find ourselves in places both unfamiliar and dark. We can neither go forward nor back for fear we’ll get lost even more, and so we’re left to sit there motionless and hope the clouds eventually break.

We’re taught the principle of What Goes Around Comes Around from an early age. Many of the troubles in life are the result of neither God nor the devil, but of our own poor choices. And while that’s true, there’s no denying there are plenty of troubles that are beyond our own doing. I’ve always thought those were the worst troubles to have. Those are the ones that will make you fear life and dread tomorrow. That make you wonder not only what’s coming next, but that there isn’t much you can do about it.

The more religiously inclined would say now would be a good time to trust in your faith and your God, and I would agree in principle. But while those words might be easy to say, they can be pretty hard to put into practice. Especially if, like me, you’ve caught yourself thinking He either has too much to do or too much to keep an eye on. Because it sure seems as though He lets a lot of things slip through the cracks sometimes.

He doesn’t, of course. I know that. You know that, too. But knowing it and understanding it? Well, that’s just not the same.

If there’s a good thing about enduring one’s fair share of suffering, it’s the wisdom that comes on the other side of it. And since I’ve endured my fair share, this is what I offer:

You’re right to feel like you’re in a deep hole and there’s no getting out. That it’s dark and damp and cold. That you can’t get out. It’s right to feel as though scoop after scoop of more of the same is being tossed on top of you.

But God is not burying you.

God is planting you.

He is sinking you into this world, not as punishment, but so you may grow and blossom and bear fruit. So you may offer shade and rest.

And so He can prepare you to not only be good, but also be good for something.

Best,

Billy

July 12, 2012

The power of a single word

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Last night, my son and I alone in the truck, running an errand:

“Dad?”

“Yes?”

“You know about cards?”

“What cards?”

“You know, like birthday cards?”

“Sure,” I said.

I looked in the rearview mirror. He was seated directly behind me, his face turned out of the window and toward the mountains, where the setting sun cast his tanned face in a red glow. Sometimes I do that with my kids—just look at them. I’ll look at them now and I’ll try to remember them as they were and try to imagine them as they will be.

“What about them?” I asked. “The cards.”

He didn’t hear me. Or maybe he wasn’t going to say. Sometimes my kids (any kids) are like that. Their conversations begin and end in their own minds, and we are allowed only tiny windows into their thoughts.

“Do you like Target?” he asked.

“Sure.”

“Don’t ever buy cards at Target, Dad.”

“Why’s that?”

“They’re inappropriate.”

Another look into the mirror. His face was still toward the mountains, still that summer red. But there was a look to him that said he was turning something large and heavy over in his head, thinking on things.

“Why are they inappropriate?”

“They’re bad,” he said. “On a lot of them, do you know what they have?”

“What’s that?”

“Butts.”

“They have butts on the cards?”

“Yeah. Big ones.”

Silence. More driving. I thought that little talk is over. I kind of hoped it was. I didn’t know where it was all going. I was pretty sure that was a ride I didn’t want to go on.

Then, “Do you know what else they have besides big butts?”

“No.”

“Bad words.”

“That a fact?”

“Surely.”

He likes that word, my son. Surely. Uses it all the time. And upon such occasions I like to say, “Don’t call me Surely.” I did then, too. There was no effect. Still toward the mountains, still the red glow. Still turning things over. I tried turning the radio up, found a song he liked. Whistled. Anything to stop that encroaching train wreck of conversation.

“Really bad words,” he said.

“Bad words aren’t good.”

“No.”

I had him then. Conversation settled.

Then, “A-s-s.”

“What?”

“That’s what the cards have on them. A-s-s.”

“Don’t think I like that,” I said.

“Me, neither,” he said.

I looked in the mirror one more time. He still faced outside, out in the world, and in his tiny profile I saw the babe he was and the boy he is and the man he would be. Saw it all in that one moment, all of his possibilities and all of his faults, how high he would climb and how low he could fall.

He looked out, and in a voice meant only for himself and one I barely heard, he whispered,

“Ass.”

And there was a smile then, faint but there, as the taste of that one vowel and two consonants fell over his lips. It was a taste both sweet and sour, one that lowered him and raised him, too.

I could have scolded him. Should have, maybe. But I didn’t. We rode on together, talking about anything but asses. Sometimes one lesson must be postponed in favor of another. And last night, right or wrong, I decided that more important than teaching my son what to say was letting him discover alone the awesome power of a single word.

July 9, 2012

Faring the storm well

image courtesy of photobucket.com

It’s been a busy week or so here in the Southeast, what with the aftermath of this storm. A derecho, they called it. A land hurricane. To me, it was just a mess.

It came upon us sudden on a calm and hot Friday night, big black clouds that crept over the stars and a wind that went from still to a gale, shearing trees and shutters and power lines. I’d never seen such a thing. I hope to never again.

We were blessed enough to come out on the other end unscathed. No trees down, no shingles missing. Friends and family fared worse. Communities were without power for days. Not an ideal situation, especially given heat indexes that topped out at 115.

The Monday morning commute to work was slow and tedious. The roads were clear of trees but not debris, forcing me from one lane to another and back just to find my way.

But the stop lights were the worst, especially in the city—giant snarls of traffic devoid of police and authority, where I knew anarchy would rule. People are busy on even a normal day, busy and stressed and in a hurry to get from where they left to where they’re going. Add to that a deep July broil, no electricity, and the stress of home and land in peril, and I knew the end result would likely be a big bubbling pot of anger.

And sure enough, the first city light I came upon promised just that. The police were elsewhere, the white lines that marked the lanes lined with large orange cones flecked with dust. And the light itself did not even blink yellow, which told me even emergency power was gone. The roads there converged into a lowercase T, with four lanes of traffic on four sides.

I threw up my hands and resigned myself to fate. I’d be stuck there until Rapture, most likely. If I was lucky.

So I crept and sauntered and stopped, the windows down, Jimmy Buffett on the radio singing that he hoped I understood but he just had to go back to the islands.

But then I began to notice a peculiar something. Traffic wasn’t really backed up at all. Progress was slow, yes, but also smooth. A continuous forward motion, easy and steady onward. One made possible not by a uniformed person waving and whistling and directing, but by fifty people engaged in a poetic form of cooperation.

Vehicles moving north to south puttered through the intersection until someone—managed only by some inward sense of spatial fairness—stopped, convincing the vehicle beside him and the ones ahead of him to stop as well, which allowed the traffic moving east to west a hole through which to move. The entire process was reversed minutes later, when someone else’s fairness compass similarly tipped north.

In the end, I got to work no later than usual. I even got to go through it all again an hour later, when the powers that be decided a college without power was no place to work.

They say there was no predicting that storm, not until the last minute. It simply sprang up. Most storms are like that, I think. You don’t see them coming until the wind’s on you. Until things start breaking.

I’ve heard places north and east haven’t fared so well. Not only were there power outages, but also looting and robbing and, well, all the things we normally associate with such temporary societal breakdowns.

It was nice to see the opposite here in my little corner of the world. Nice to see people working together rather than looking out for themselves. To see them letting someone else go first, even it was just at a broken stoplight. It gives me a little hope that, while things can and will be bad, we don’t have to be.

July 5, 2012

The big four-oh

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I’ve never been much on birthdays. Only two stand out—my sixteenth, because it promised the freedom of driving, and my eighteenth, because it promised the freedom of most everything else. The rest? Meh.

But tomorrow I turn forty. Forty feels different. Like it should mean a little more than the little my birthdays usually mean.

I find this a bit unsettling. Thanks to the marvel that is modern medical technology, age shouldn’t (and really even doesn’t) matter much anymore. I’ve heard the forty is the new thirty. I hope that proves true. But there is still that nagging thought in my mind that to be forty was to be elderly only a few centuries ago, and it was downright ancient a few centuries before that.

I feel fine. Let’s get that out of the way. I’m healthy. I’m in good shape. All my parts work. And aside from an occasional popping sound in my left knee whenever I stand and a little tug in my shoulder when the weather is cool and damp, I feel no different at forty than at twenty. Sure, I’m losing hair in all the right places and gaining it in all the wrong ones. But I’ve been doing that since I was eighteen.

There’s a ballgame on as I write this. Yankees vs. Rays. Perfect way to spend an afternoon, until I realize that I’m much closer to the age of the managers than I am the players.

If I really get to the heart of the matter—“To the brass tacks,” as the old farts around here say—I’d say that my apprehension of entering a new decade has less to do with age and more to do with field placement. Think of life as a football field. I read recently that the life expectancy of a healthy American is about eighty. If that’s true, I am currently standing at the fifty yard line.

Tomorrow, I’ll be halfway to the end zone.

I know, I know. Such things aren’t really all that exact. I could live to be a hundred. I might not see fifty. But that’s not really what I mean. What I mean is that chances are good that I’ve lived half of my life.

It’s moments like this that make a person take stock of things. Call it a mental and spiritual inventory, a tallying of goods and services. As in—what good have I done? What bad? And are those scales balanced, or are they leaning in one way or the other?

Have I lived a good life?

Have I been a good and faithful servant?

Honestly? I’d say those scales are balanced. Maybe leaning a bit the wrong way, but just a bit. I’m still young enough to try to be a good person, but I’m old enough to know there are no good people, there’s just grace and hard trying.

I wish I could have done more in the first half of my life. I wish I could have done less. Such is what it means to be alive.

Me, I’m hoping the next forty years are spent wiser than the first. I think the way to do that is to ask God every day what I did wrong, what I did right, and what I can do better tomorrow.

Maybe I should have been asking that all along.

July 2, 2012

Life choices

image courtesy of photobucket.com

My son wants to change his name.

It isn’t that he’s unhappy with the one he has now. It’s fine, he says. It isn’t kooky or hard to say, and it’s only one syllable. I asked him why the one syllable thing is so important. He told me that one syllable words are easy to spell. He said there was a girl in his class last year named Shenequia, and she had a horrible time trying to spell her name.

“Her name had THREE syllables, Daddy,” he told me. “It took her forever to write it.”

So it’s nice to know that deep down he’s okay with what he’s called. That’s not the reason. The reason is something deeper, more personal.

He didn’t have a say in it.

And he should, he says. Because it’s HIS name after all, not mine or my wife’s, even though we were the ones who named him. And it’ll be his forever. Shouldn’t he have had a say in something so important?

Truth is, he had a point. So I asked him what he would name himself if he could. His answer?

Batman.

Batman Coffey.

My answer was no.

This is really all just a small part of a larger problem for him. Call it a pre-teenage bout of philosophical angst. He’s starting to become aggravated by things that plague us all from time to time.

It’s not just his name that’s had him troubled lately. He’s a little upset that no one asked his permission to send him into this world, too. Not that he’s upset with his life, or unthankful, or that he’d much rather NOT be born, or that he isn’t grateful for both the life and family he has. It’s just that, like his name, he didn’t have a say.

Nor, he says, will he have a say in when he dies. He understands on a rudimentary level that there are things he can do to prolong his life—things like not smoking and not drinking and eating right and exercising—but on a basic level he also understands that you can do all of these things and still be hit by a car tomorrow.

It really is depressing, he says. And he says that if you don’t have a choice in what you’re called or when you die or that you were even born, what use is there, really? Why even bother.

Heavy stuff for a boy (I’ve been told he gets all of this honest, and I suppose that’s true). But I think it’s good to have these bouts of inner turmoil from time to time.

And really, it isn’t all bad.

Because yes, we’re born and named and depart from this life and there really isn’t much we can do about any of that, but what I want him to know—and what I must often remind myself—is that all the rest in the middle, that big chunk of in-between, is all up to us.

In the end, we decide.

We. Not others.

We’re not asked to be born, but we are the ones who make our lives.

We are not asked to be named, but we are the ones who decide how we leave our mark.

And the hour we will shed this world for the next is largely unknown, but we it is up to us how that death will be met, and what world that next will be.

June 28, 2012

The more things change

It had been stuck for years between two drawers in a desk that sits in my mother in law’s living room—a thin stack of photocopied papers, folded into fourths. Trash, most likely. That’s what we all thought. All the trash gets caught between desk drawers.

It had been stuck for years between two drawers in a desk that sits in my mother in law’s living room—a thin stack of photocopied papers, folded into fourths. Trash, most likely. That’s what we all thought. All the trash gets caught between desk drawers.

Then we unfolded them and discovered that what we thought was trash was treasure instead. That thin sheet of paper, so worn and dated that to open them was to risk their destruction, was a collection of pages copied from my wife’s great-grandmother’s journal.

From 1937, to be exact. That’s seventy-five years. A time when war loomed and a financial crisis gripped this country like a vise, when people were scared and worried and oftentimes, very often, it felt like God was about to throw in the towel and call the whole world off.

Much like now, really.

My parents still talk about those days, even if those days were still a little before their time. We’ll sit around the kitchen table on the weekends with pizza, talk about our weeks and what’s been in the papers, and after a while conversation will usually swing to what my father calls “the old days.” To hear him say it, most everything was better in the old days. The air was cleaner, people were nicer, and there weren’t so many damn liberal Yankees in town. And then my mother will chime in and say that not all the liberal Yankees in town are really so damnable, just some, but that in all the other ways Dad is right. Things really were better.

Me, I’ve always had my doubts about that. And when we found the pages from that journal, I figured this was my chance to see who was right and who was wrong.

I sat down with them just a little while ago. Brought them out to the porch where the light was good and the outside was calm. Went through the entries one by one, reading that feminine script that was both precise and delicate. From a fountain pen, I guessed.

The section covered May through September of that year. A hot summer, from the reading. Some days were blank. Most were not. What I found was the usual fare, which was exactly what I wanted. There were worries about crops and drought. Births and deaths. Family gatherings, pig roasts, parades. Carnivals. There was fear—plenty of it—about war in Europe, but there was also plenty of peace and joy since everyone seemed to think that war, if it came, would be none of our concern.

People were married.

Children grew and left home.

Life came and was enjoyed and went on, a great wheel that spins often without our knowing until it’s time to get off.

And you know what I found in the end? We were both right, my parents and me. Because those days were better and they were also not. It was a time in my part of the world when horse and buggies were just as prevalent as cars and most people still didn’t have a telephone and a journey of twenty miles was more excursion than trip. The world still spun then, the world always has, but it was slower going. And in that, my parents were right. Because if there’s anything I think we all need right now, it’s to slow down.

But there was still hurt. There was still fear. There was hardship and sorrow and hunger and want. Things were different then, yes, but there’s a great contrast between different and better. And in that way the world then was no different than the world now, just as the people then were no different than us. Ancient Viking or modern American, caveman or cosmopolitan, we’re all the same and always have been. The times may change, but we do not.

If that sounds a bit depressing, I assure you it isn’t. I found a great comfort in that journal. Everything about that summer of 1937, all that joy and especially all that bad, was endured. People moved on. They survived their hardships, lived through their wars. And even in the midst of those, they found reason to laugh and love and hope.

Would that we find the courage to do the same now.

June 25, 2012

One unselfish act

image courtesy of photobucket.com

It is a known fact that one of the main reasons why I’m friends with Tommy Fuller is because of what’s in his backyard. I realize this paints me in somewhat of a bad light on the surface. In my defense, though, Tommy is not only aware of this, he’s fine with it. He figures it’s a trade off. One of the main reasons he’s friends with me is because he borrows my golf clubs.

It’s a good deal as far as I’m concerned. Tommy’s a great guy. Even better than that is the fact that he has an open door policy when it comes to his backyard. I can visit any time I like, even if he isn’t there. The kids are welcomed, too. Sometimes we even make an afternoon of it. They can jump on his trampoline, and I can climb his oak tree.

Tommy has one of the biggest back yards in town with THE nicest tree smack in the middle of it. Tall and full, and the limbs are spaced just far enough apart to let through the perfect amount of sunlight. Home to squirrels and robins and friendly bugs. It’s the sort of tree that belongs more in a Disneyland attraction than a redneck’s backyard.

The farm has been in the Fuller family for generations, and it’s one of the oldest in the area. Tommy’s grandfather and father were both raised there, as was he. When his mother passed away ten years ago, he moved in and got control of the property. And when the time comes, Tommy will pass the torch onto one of his sons. In the Fuller family, the circle never ends.

There aren’t many properties around here that carry charm like that anymore. Most of the farmers in town have sold their acres of fields and forest to developers, giving in to the promise of a life of comfort rather than sweat. Tommy won’t bow to that false promise. There will be no subdivisions on his land. Not because his principles are too strong or his faith too unwavering, but because of that tree.

Because it is quite literally a family one.

Look on the back side and you can see the faint outlines of his father’s pledge to his mother back when they were mere boyfriend and girlfriend. BF Loves KT, it says. Tommy says his mother and father would sit beneath that tree often during their courtship, resting in the shade of their love.

And on the other side are the marks Tommy carved to his own bride to be, pledged in wood on the night they became engaged.

In the upper reaches of the oak is a tree house that Tommy built for his boys. Though worn, it’s still in good shape. He sees his future grandchildren playing pirate there.

But the best part? The best part isn’t the tree, It’s the stone plaque beside it.

03 MAY 1901, it says.

According to Tommy, his great grandfather planted that tree himself on a calm spring afternoon. Dug the hole, gently placed the seedling inside, then covered and watered it. And after that he stuck his shovel in the ground and just smiled. Tommy remembers his grandfather saying that it was a strange smile, part sadness and part joy. The sort of smile a dying man wears. Tommy doesn’t know what was wrong with his great grandfather, just that he didn’t have much longer. And he didn’t. If you drove over to the church nearby you would see that the date of his death and the date the tree was planted are less than a month apart.

It’s amazing that something so small and fragile could grow into something so large and strong. But love is like that. Hope, too. That’s what I think about when I sit in that tree.

And I also think about this—on a calm spring afternoon more than a century ago, a dying man’s last act was to plant something he would never be able to see grow. He would never get to rest in its shade or climb its branches. He would never get to enjoy it, but he planted it anyway. Not for himself, but for those who would come afterward.

I like that idea.

According to some, there is no such thing as an unselfish act. But this comes close. And I think that for all the lofty goals the human spirit can strive to accomplish, this is the most noble—that we spend our days in pursuit of something that will outlive us. That we plant seeds destined to bless not only ourselves, but generations.

June 21, 2012

Where tears go to die

I’m sitting on the balcony of our eighth-floor hotel room on a quiet Monday evening. The Atlantic stretches out below me like God’s welcome mat. A soft breeze kisses my face and leaves behind a salty film I desperately hope will never completely wash off.

I’ve abandoned my laptop for old fashioned paper and pen. On the small table in front of me is a rare indulgence of Hemmingway’s beverage of choice, and in my left hand is an even rarer indulgence of a long-forgotten vice: a very nice cigar. Bob Marley is singing “No Woman, No Cry” to me through the earphones on my head, and I lean back in my faded jeans and rest my bare feet against the wall.

This is what the ocean does to me.

It makes me smile, makes me relax. Makes me temporarily suspend my fears and regrets. It replaces the storms of my life with sunshine and the filthy mud with clean sand. And all those nagging cares that wash over me are silenced by the peaceful sound of waves meeting shore.

Here, I am a better me.

But this is not why I come here every year. Not why for one week out of fifty-two I say goodbye to my mountains to seek a distant shore.

If you really want to know why I make this pilgrimage, all you need to do is look at the old man in the bench eight stories below me. Sitting right there on the boardwalk, staring out to sea.

I flirted with the idea of taking a picture of him, if only so you could see what I’m seeing right now. But I can’t. It seems like an invasion of his privacy, a sacrilege to his holy moment. So instead I snap a picture of what he’s been looking at for the last six hours.

Yes, that’s right. Six hours.

We first passed him on our way out to the beach, loaded down with shovels and pails and chairs and towels. Seventies and tired, with a worn cane propped against his right leg. He stared out to the horizon with a soft smile on his lips. It looked to me that he was both there and somewhere far away.

When we passed him on our way back in for lunch, I nodded. He smiled. I nodded on our way back out afterward and got a wave.

Then, as we were calling it a day, I passed and said, “Pretty weather, huh?”

“Sure is,” he answered.

Sometimes having kids gives you opportunities you would otherwise miss. When my son began crying over a missing toy that he was sure would be swallowed by the sea overnight, I went back down to the beach to retrieve it for him. Another wave, another smile. On my way back, I decided to stop.

“Not much beats this view,” I said.

“Come here every day,” he replied. “It’s the only place where the scenery never changes but always gets better anyway.”

I liked that enough to stick around and hear more.

“You and your family from around here?” he asked.

“No, we’re on the other side of Richmond,” I said.

He nodded. “Nice country up there.”

“Beautiful country,” I told him. “But not like this.”

“My wife and I moved here from Iowa,” he said. “Came here, oh, twenty years ago. We retired and realized we’d never seen the ocean. Our kids were grown and gone, so we figured it was the right time.”

His wife wasn’t with him, and I wasn’t about to ask where she was. I knew. I knew by the way he had sat on only one side of the bench rather than the middle. Knew by the fact that he rested his cane against his right leg even though he was right handed. It was the product of repetition. Someone else had shared that seat with him for twenty years.

“Know why I come here?” he asked.

I shook my head.

“Because the ocean swallows our tears. That’s what she always told me. ‘Harry,’ she’d say, ‘I think all that is all the tears we shed. God just bottles them up and pours them out so we can have a place to visit where we can leave our struggles.’”

“I like that,” I said.

“Me, too.”

I left him to his pouring, and then I went up to my room and onto the balcony to do the same. Because that’s what the ocean is to Harry and I. A place to pour out our tears and leave our struggles. A place to find the better us.

June 18, 2012

Breathe deeply

I won’t say the reason I’m heading to a small island off the coast of North Carolina is because of a bottle of my wife’s body wash. That would be an untruth. But it would also be an untruth to say that bottle of lavender-flavored goop doesn’t have anything to do with my vacation. It does.

I won’t say the reason I’m heading to a small island off the coast of North Carolina is because of a bottle of my wife’s body wash. That would be an untruth. But it would also be an untruth to say that bottle of lavender-flavored goop doesn’t have anything to do with my vacation. It does.

Me, I’m not a body wash kind of guy. Just give me a bar of plain soap. No bottles, no fancy bouquet of smells. My wife? She likes that sort of thing. Apple and peach and pear and whatnot. She smells like an orchard, my wife.

The thing about having such a mélange of soap is that things tend to get a little messy. There are bottles everywhere. Dozens of them, in various stages of use. Last night, my bull of a son got out of the shower and stepped on them, scattering them like miniature bowling pins.

I was nice enough to clean them up seeing as how everyone else was getting packed. Spending a week from home is akin to adopting a nomadic lifestyle. There are clothes to gather, and medicine and food and computers and iPads—a lot of stress just to get ready for a little relaxation. And though I’m always up for a trip to the ocean, this year things are a little hectic. Edit this book. Write that book. And can you do this interview? I’m busy. I’m busy and there’s really no time for me to relax, because Things Must Be Done. And sometimes you have so many Things That Must Be Done, the only thing you can really do is pick up a mess of bottled soap that your son has spilled over.

So I picked them up one by one, arranging them in no particular order or way, just trying to keep them and myself upright. Then I turned one of the bottles—Lemon Mist, or something like that—around and read the label for no apparent reason at all.

And there it was.

It’s amazing, really, the sorts of wisdom one can find in the most unlikely of places. Over the years I have found guidance from acorns and cornfields, guitar strings and rainy afternoons, but until that moment I had never had the occasion to be smacked in the head by Truth via a bottle of body wash. But we never really know from whence inspiration will come, do we? I think that’s all part of the fun.

You see, written in tiny black letters on the back of the bottle, right below a surprisingly long line of ingredients, were these words:

For best results, breathe deeply.

Yes.

I’m not going to the coast because of a bottle of soap, but I am going because of what that bottle of soap says. Because it’s right, you know. Life is a beautiful thing that can get tough at times. It’ll purr just before it bears its teeth. And in those times when things get so busy and so complicated, we all have a tendency to forget that it’s the little things that keep us going. The simple things like breathing deep.

June 14, 2012

Redneck love

I’ve been following them now for five stoplights, all of which have turned from yellow to red just as we approached. Sitting here, staring at the rodeo decals on the back of his battered ’74 Ford.

Hanging from the gun rack in the back window are the two prerequisites every teenaged country boy must display in his truck—an axe handle and a lasso. Neither of which seem to have been touched since he first put them there.

But I suppose he hasn’t had the time to either get into a fight or rope a steer. Not with the young lady beside him. Right beside him. The absence of bucket seats and a console has allowed her to sit practically on top of him. “That’s the problem with those old trucks,” the older men around town say. “No power steering. Takes a fella and his girl both to drive the things.”

The lack of power steering, of course, has nothing to do with it. Love does. Despite all the red lights, I should have been halfway home by now. I just happened to get stuck behind two people who consider a red light as the perfect excuse to kiss.

And boy, do these two know how to kiss.

It’s been the same scenario every time—red light/brake/kiss/breathe/kiss. And then, a few moments after the light turns green, she pulls away and mouths I love you. He stares, not quite believing someone this special, this perfect, could ever say such words to someone like him.

I could pass them. Could blow my horn to get his attention onto the road rather than her. But I do neither. Not because I’m some sort of highway peeping Tom. Because I am witnessing one of the truly great things in this cold, dark, depressing world.

Young redneck love.

It is a marvelous thing, this phenomenon. Not rare, at least around here. But special nonetheless. Here are two people barely out of high school, waging war together against both fate and circumstance. Common sense and reality says that neither are college material. Both have likely moved into the job force, occupying one of the many barely noticed positions in town. Cashier or factory worker, maybe. And whether together or apart, both will face the very future that so many here have been given: lots of worry, lots of struggle, and not a whole lot of rest.

Yet here they sit anyway. Despite all the odds. Because they no doubt feel the odds don’t matter. In fact, nothing matters. Nothing in the world. They are together. Apart they may be down and out, struggling to find their own places in the world. Powerless and lost. But together? Together there isn’t anything they can’t overcome.

Love does this to people.

It convinces them neither that the world is too big or too little, but that the world just doesn’t matter. They have their own world, one full of rainbows and blooming flowers. Dinner at McDonald’s might as well be dinner at Sardi’s. Watching the semi-pro baseball team play on the field behind the fire department might as well be watching the Cubs at Wrigley. To them, there is no best place in the world. The best place in the world is wherever they happen to be at the moment.

The final light turns green. One more kiss/breathe/kiss/I love you later, and he turns his signal on for the next right. I drive past and cast them one more look. She’s sitting even closer now, her head on his shoulder. Riding off into the sunset, just where they belong.

Tonight when my head hits the pillow and I thank God for both today and the promise of some tomorrow, I’ll pause and think of this young couple. I’ll say a prayer that the angels watch over them.

And I’ll say another that they hang on.