Billy Coffey's Blog, page 47

October 10, 2011

Dinging the universe

Steve Jobs image courtesy of photobucket.com

I'll admit I'm a little late on the death of Steve Jobs. Truth be told, I didn't know he'd died until two days after the fact. It was all over the news and the internet, people tell me. And you couldn't pick up a newspaper without seeing his face on the front page. I guess that's why I hadn't heard. I don't really keep up with the news. I've found it helps me enjoy the world more.

More truth: I hate computers. Maybe that's the half-Amish side of me talking. Maybe I'm secretly afraid technology will steal my soul. Or maybe it's the simple fact that I've never been able to work them well. Whichever the case, I count myself among the few who trust pen and paper more than keyboard and screen.

I heard last week that his biography, titled simply Steve Jobs, will be released sooner than expected. Evidently he granted his biographer unparalleled access to his life and sat for hours of interviews. Quite a coup, given that Mr. Jobs was a pretty private man. The book is already number one on Amazon. Sony purchased the movie rights for a million dollars.

Imagine, someone paying a million dollars for the rights to make a movie about your life. Your accomplishments. Imagine being called this century's Thomas Edison. Or being compared to Leonardo da Vinci.

Imagine.

And yes, that's the sort of person I'd like to be. Shouldn't we all? I'm around college kids five days a week, almost ten hours a day. You know what? Most of them don't want to become great. Most of them have somehow become convinced that they're already great. They don't want to affect the world, they want the world to affect them. I think that's kind of sad.

I think there should be more people who say "I want to put a ding in the universe," as Steve Jobs once said.

That's what he did. He dinged the universe. But I wonder at what cost. His biography was written with his permission, he sat down and did all those candid interviews, not for the reason you might think. Not to inspire or inform the world Steve Jobs helped to transform, but simply because of this:

"I want my kids to know who I am."

Of all the things I've read about Steve Jobs over the last week or so, that's the one that stands out. Not the iPod or the iPad or the iPhone, but the iWant.

It takes a lot of effort to put a ding into the universe. A lot of time and failure and trying again. A lot of passion. It demands that priorities be set clear. Things like work take precedent. Things like family do not. And while I'm thankful for the Steve Jobs of the world and their dedication, the sacrifice the make is one too steep for me.

Steve Jobs' death struck me. By all accounts he was a brilliant man who changed our world. There are a good many people in this world who long for those two things—to be both brilliant and remembered. I don't mind saying I count myself among them. But honestly, the odds are good I'll be neither. Maybe you, too. More probable than not, I will pass through this life just as the billions before me. My footprints upon this earth will be small and vanish. My picture will never grace the front page. The world will not notice my passing.

I will not ding the universe.

But when my time comes to trade this world for the next, I will pass with a smile. I'll be ready, because I may not have much, but my kids will know who I am.

Share and Enjoy:

October 5, 2011

Future Kevin

image courtesy of photobucket.com

He sits by himself at a small table in the back of the lunchroom. Chin in his hand, eyes, down. His fingers flick at discarded bits of the day's pepperoni pizza that were missed by the lunch lady's dishrag. The afternoon sun filters through tiny handprints on the windows, making the grass stains on his too-short jeans glow a deep emerald.

He sees me as I walk in—there's something about a door opening that makes even the meekest of look up in reflex—and turns aside. Today is Friday, and I told him I would need an answer by the end of the week. But his back is turned away and his body is folded in upon himself to make him as small as possible, and I think no. No, he still doesn't know.

Waiting for my kids in the school cafeteria gives me a sense of connectedness to a part of their lives I mostly miss. I get to see where they eat, how they interact with others, what kinds of people surround them. And I get to see other kids, too.

Kids like Kevin. The one alone at the small table in the back.

He's there every day, waiting for someone to pick him up and trying to stay hidden until they do. I said hello to him Monday afternoon. I was a bit early that day, and there was no one else to talk to. I was counting on a one-sided conversation. Kids like Kevin—and there seems to be many of them today, yes?—desire nothing but the next moment, to continue on, regardless of the unnamable weight they bear. I didn't know what Kevin's was (and I still don't), but I knew it was there. I could feel it.

So I said hello. Sat down beside him at the small table and flicked a bit of food away—it was French fries that day—and waited for him to talk. It took prodding, but he did. General stuff. Nothing of home. Kids like Kevin, with their unnamable weights and downcast eyes, don't talk much of home.

He'd been in trouble that day. Kevin showed me the white slip of paper his mama had to sign. Daydreaming, the note said. I told him I daydreamed a lot and that daydreaming was fun, but school was important.

"No it isn't," he said.

"What do you want to be when you grow up?" I asked him.

Shrug.

"Come on," I said. "You have to want to do something."

Shrug.

"When I was your age, I wanted to be an astronaut. Didn't work out, but I still look at the stars a lot."

Kevin said nothing.

"Tell you what, I'll be back on Friday. You think about it and let me know then. Deal?"

He said he'd try. The kids came and we left. I waved to Kevin as we went out the door. He didn't wave back.

And now, he's ignoring me.

"Hey Kevin," I say.

Shrug.

"Been doing any thinking about what I asked?"

His eyes said yes. I pulled a chair up to the table and sat. My mind tried to think of something little Kevin wanted to be. Maybe an astronaut, like I wanted once upon a time. Or President, though I figured there weren't many kids nowadays who wanted to grow up to be that. Maybe a scientist.

"I guess I'm going to work at Little Caesar's like my mom."

Oh.

"That's all you want to do?" I ask him. "I mean, that's great if that's all you want to do. But…that's all you want to do?"

He lowers his head to find something to flick on the table. "That's all I can do," he says.

"I don't believe that," I tell him, and Kevin shrugs.

The kids are on their way. I say goodbye to Kevin and leave him at the table. I don't know when someone will pick him up, don't know when I'll see him again. But I know I'll worry about him. A boy like that, a boy that young, should see this world as one of possibility and magic. His sights should be set higher than where they are. He should believe in himself more.

But I wonder if we've reached that point where we no longer inspire our children to become more than ourselves. If we see them as mere carbon copies, destined to make our own mistakes and suffer through our own failures.

And if we've accepted the lie that says greatness in life is reserved for all but shy boys in too-small jeans who sit alone at the lunchroom table.

Share and Enjoy:

October 4, 2011

Signs of a season change

WARNING!!! DO NOT OPEN THIS DRAWER UNLESS YOU ARE MOMMY. ANYONE WHO OPENS THIS DRAWER WHO IS NOT MOMMY WILL BE IN TROUBLE!!!

WARNING!!! DO NOT OPEN THIS DRAWER UNLESS YOU ARE MOMMY. ANYONE WHO OPENS THIS DRAWER WHO IS NOT MOMMY WILL BE IN TROUBLE!!!

Taped to the top left drawer of my daughter's dresser. Saw it last night when I checked to make sure she was sleeping. Written in yellow highlighter, in all caps, and with a total of six exclamation points.

It seemed her point was clear enough. Do not open. Unless you're Mommy. Off limits to both her father and her little brother. The latter was understandable—big sisters do not want their little brothers going through their things. But the latter was me, and my daughter was not in the habit of hiding things from her daddy.

So I was faced with a conundrum that felt more deep and profound than to merely look or not. It was more than that. It was to invade my child's privacy or make sure she didn't have anything in her drawer she wasn't supposed to. Not likely (not likely at all, really), since she's never been one to do something she shouldn't. But still, it ate at me.

I would like to say here that I did not look then. I left the note untouched, tucked the blankets around my little girl, and went to bed. I tossed. I turned. I thought and wondered.

Given what the piece of paper said, I felt sure my wife knew what was in my daughter's dresser drawer. She was asleep, though. I couldn't wake her. That doesn't mean my conscience prohibited it—by then I'd realized I would never be able to get to sleep until I knew, and by then I'd convinced myself whatever my daughter was hiding had to be important—but that I literally could not wake her. I shook her and called her name and kicked her under the covers.

My wife didn't move. Teachers are often tired.

Which meant there was only one thing left to do.

So I got out of bed. Walked from our room into my daughter's, checked to make sure she was still asleep, and ignored the sign on her dresser drawer.

The small lamp on her nightstand offered just enough light to turn black to shadow. I grabbed the first thing I felt, turned around, and held it up to the light.

A sock. Tried again. Another sock.

I rifled through what I could, looking for…well, I didn't know what I was looking for. Something other than socks, I guess. I pulled out T shirts, old birthday cards, some chapstick, and a misplaced Barbie.

The something stuffed on the bottom in the back of the drawer felt like neither sock nor T shirt. I pulled it out, turned, held it up to the light, and nearly fell down.

Sweet fancy Moses, Holy Mother of God, Matthew Mark Luke and John, it was a bra.

For my daughter. My nine-year-old daughter.

I dropped it. Thankfully, it was little more than a sliver of cotton that weighed all of three ounces. It made no sound on the carpet. I stood there with it in front of me, leering at me, taunting, saying, "Ha! Didn't expect that, did you?" to me. I looked from It to her, the little girl sleeping in the bed.

I wondered what had happened and how it had happened.

Sometime—recently or not, though I hoped it had been moments and not months—a season had changed in my daughter's life. We gauge our passing through this life by years. Seasons would be better. Because sometimes we languish in inner winters, sometimes we burst forth to a new springlife, sometimes we rest in the sunshine, and sometimes we fall.

Years do not matter. Seasons do.

It was now springtime for my daughter. I prayed that didn't mean I was to suffer winter.

I picked up the bra and settled it back into the drawer, mindful to next time pay heed to the warnings she posted. I gathered the covers tight around her. She opened sleepy eyes and smiled at my sight.

"Hey Daddy," she said.

"Hey back."

"What are you doing?"

"Checking on you."

She smiled again. "I like it when you check on me."

I kissed her head and said, "I'll always check on you."

And I will. No matter the season.

Share and Enjoy:

September 28, 2011

Why I'm saying goodbye

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Some friends of ours moved last week. Traded one set of blue mountains for a set of rocky ones. It's something they've wanted to do for a while (he has family in Colorado, not twenty miles from their new home, and she grew up in nearby Boulder). Their move had less to do with the economy than a simple desire for a change of scenery. I nodded when they told me that, but I didn't really understand. Who would want to leave rural Virginia?

I've known them for about fifteen years now. They've been to my home, I've been to theirs. We've shared meals and Christmas presents and birthday parties for our children. It's a sad thing that in a world defined by hustle and bustle and there's-always-something-going-on, few people slow down enough to make good friends. That's what I'd call them—good friends.

But they're gone now, a thousand miles westward. They will find new lives, and I will keep my old one.

Their leaving was a bit anti-climactic. That surprised me. I suppose deep down I knew what I had yet to consider, which was that they'd still be around. There's the phone, of course. E-mail. Facebook and Twitter. Skype. No matter that two mountain ranges and a great big river separated us, they'd still be no more than a few button pushes away.

That's when I realized how much the world has shrunk. Never mind that our technology has made it possible to cure disease and peer into the deepest reaches of the universe and know within moments what has happened in a tiny spot across the world. It has done something more profound than all of those things together.

It has lifted from us the heavy weight of ever having to say goodbye.

I've read stories of families separated during the Great Depression, of parents and children cleaved apart as some remained behind and others struck out for new territories and better hope. They had to say their goodbyes. Many were never heard from again. Can you imagine?

I remember looking around at my classmates during high school graduation and thinking that I'd never see or hear from most of them again. These were friends, many of whom I'd known since third grade. They'd shared my life, I'd shared theirs. Yet as I sat there I knew all of that was slipping away. I knew that to live was not about being born and dying later, it was to endure many births and suffer many deaths, and sometimes that birth and death happens in the same moment.

I was right. Twenty years later, I've not seen many of them. But more than one have friended me on Facebook, and from all over the world.

This should make me feel good, I guess. Aside from death, there are no farewells now. There is always "Talk to you soon" or "Shoot me an email" or "DM me."

But I don't feel particularly good. I think we're missing out on something if we never have to say goodbye anymore. I think it robs us of the necessity of truly understanding the impact some people have on our lives, and the impact we have on the lives of others. To have to say goodbye is to know a part of you is leaving or staying, either scattered through the world or planted where you are.

I say this because just a bit ago, I received an email (plus pictures) from my friends. Things are well with them. They're settling in and getting used to things. They're happy. And that's good.

But rather than casually shooting an email back, I think I'll sit down and take my time. I think I'll treat it as a farewell, even though it isn't. I think I'll tell them just how much I'll miss them even though it'll be as if we're still just down the road from each other.

I figure somewhere deep down, they'll need that goodbye. I know I do.

Share and Enjoy:

September 26, 2011

Showing us what we can't see

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I had no idea how far we'd walked—when you're tromping through the woods with two kids, time drags on until it becomes irrelevant—but it was far enough that we were ready to turn around and go home. After all, it wasn't as if we had a map to go by. All we had were stories.

"Maybe we should just pray," my son said. My son, who announced last week that he wanted to be a preacher when he grew up. To him, praying is the answer to everything.

"I think God would rather we walk than pray," I told him.

"Why, did you ask him?"

I didn't answer. We pushed on through the brambles and found the river—at least that part of the story had been proven right—then decided to sit and watch the water. My daughter tried to spot fish, my wife tried to spot spiders, and I tried to figure out where we should look next.

My son, the future Preacher Man, looked into the blue sky peeking through green trees and said, "Our Father, whose art ain't in heaven, Halloween be your name."

"This way," I told them. "I think it's over here."

Which wasn't true at all. I had no idea where it was or even if it was, but you know about men and directions. Besides, it wasn't like we could pull over at the next gas station.

My daughter said, "Maybe we should just go home before we get eaten," which brought more prayers from the little boy in the back.

I reminded them of the value of a story, of how the whole world was made of them and sometimes they're true and sometimes they're not, and how sometimes the ones that are not have more truth. And when you come across a story about an old home forgotten somewhere in the mountains, you have to go look. You just have to.

So we trudged on—me, my wife, my daughter, and the Preacher, who was now calling down the Spirit to keep Bigfoot away.

Truth be known, I didn't think we'd find a thing. Though the mountains here are littered with the remnants of pioneer homesteads, their locations are masked by either wilderness or the foggy memories of the old folk. But the directions I'd received turned out to be pretty darn close. It wasn't long until the woods opened up a bit into an ancient bit of clearing, and wouldn't you know it, there was something up ahead.

Of course that something was hidden by a couple hundred years of changing seasons. Trees and bushes and plants had reclaimed the area that was once taken from them. All that remained to be seen was a bit of foundation. The rest was enclosed by an impenetrable wall of overgrowth.

"Let's try to break through," my daughter said, to which she received a chorus of no ways.

"I don't want to go in there," my wife said.

"I'm too tired to try to go in there," I said.

"We should really pray first before we go in there," my son said.

Simply going back was no longer an option. We'd found it now, and to leave without at least a look around simply wouldn't do. So we looked. All of us. We poked and prodded for weak spots, we tried to peek into what had likely gone unseen for centuries. We stood on tiptoes and jumped and, once, even tried to make a human pyramid. But it was no use. The mountains would not give up their secrets that day.

"Hey," my son said, "I see something."

He was knee-bent, face almost in the dirt, peering through the undersides of thorns and thickets.

"Hey, wow."

The rest of us followed. Knees bent, faces in the dirt, peering through the thorns, we found holes just big enough to peer through. What lay on the other side was nothing more than the remnants of a stone foundation, but to us it was Machu Picchu and Stonehenge and Easter Island rolled into one.

It was then that I realized what my son had done. The little Preacher Man, too little to jump too high or tiptoe too up, had decided to use his smallness to his advantage.

He'd gone to his knees.

"You can see more if you get on your knees, Daddy," he'd often said. "If you stand up, you just see what you can. But if you bow down, God will show you what you can't."

Those words, profound as they were, had always gotten him a rub on the head or a squeeze on the shoulder. Nothing more. But then I knew just how right he was, and I wondered just how much I'd missed in my life because I'd been standing instead of kneeling.

Share and Enjoy:

September 21, 2011

Pleasure in the wanting

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Today is the end of what has become a rocky, tiresome, and utterly aggravating road. That's something I'll tell you, dear reader, and no one else. Especially my son. Because he is to blame for all of this. And, by extension, so am I.

I've always found it fascinating how certain traits in parents are passed on to their children. I'm not talking about things like hair and eye color. I'm talking about attitudes and preconceptions, things that go a long way in defining how they see the world. Good things. Bad things, too.

Take my son, for instance. Folks say he has my looks and my hairline, two things for which I've already apologized to him. Like his father, he loves baseball and walking through the woods. And he also has a tendency to fixate on something he wants to the point of near obsession.

It's this last point that has led us down the rocky, tiresome, and utterly aggravating road.

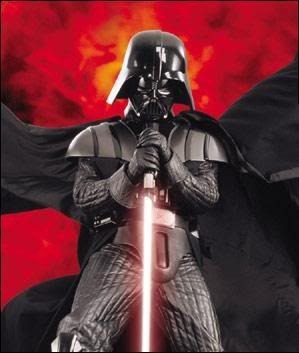

My son also loves Star Wars (again like his father, once upon a time). Five and a half weeks ago found the two of us in the toy aisle at Target, where we stood face to face with what he described as the single greatest thing ever in the history of the world—a Darth Vader costume. Complete with mask, utility belt, cape, and a genuine imitation lightsaber.

"I gotta have that, Dad," he said.

"Sure is nice." I looked at the price tag. "How much money do you have?"

He reached into his pocket and pulled out three quarters, a rubber ball, and three Legos.

"Don't think that'll do it," I told him.

My son knew that. Reality is rarely comforting, however, so he spent the next few days sulking. All of his other costumes—and his has dozens—paled in comparison. His life would not be complete until he could walk through the house as Darth Vader, doing that deep, throaty breathing and intimidating us all with the dark side of the Force. His paltry (to him) allowance meant he'd have to wait months to save enough money, and by then the costume would be gone. It was hopeless.

But then my son remembered his report card and his standing deal with his grandfather. Good grades equaled good money, much more than what I'd give him for cleaning his room and taking out the trash. The problem was that he had five weeks to wait.

And let me tell you, that was a long five weeks. A rocky, tiresome, and utterly aggravating five weeks.

He marked the days off his calendar. Asked me to float him a loan. Stared at a picture of the costume he found on the internet, then stared at me with puppy-dog eyes. He moaned and whined. He yelled and pouted. He even said he dreamed he'd finally bought it. My son obsessed over that costume for five weeks, and he just about broke me in the process.

Then came today.

Report card day.

His marks were good, which meant a quick trip to the grandparents between the end of supper and the toy aisle at Target. Two hours later, it was all mercifully over. I peeked at my son through the rearview mirror on the way home. He was cradling his prize. You should have seen the smile on his face.

It stayed there for a while.

As I write this, my son's beside me on the sofa. He's dressed to the nine's—mask, cape, belt. Lightsaber. He's slumped in the corner watching a rerun of Phineas & Ferb. During the last commercial, he said, "Did you see that new Lego set they had at Target? That would be awesome."

I figure I have another six weeks or so to hear that. Yet another rocky, tiresome, and utterly aggravating road.

I suppose I'll comfort myself with the hope that he's learning a valuable lesson through all this. One that we all should learn at some point.

Because there are a lot of things in our lives like my son's Darth Vader costume—things that are wonderful before we attain it and nothing special afterward.

Share and Enjoy:

September 19, 2011

Hidden treasures

image courtesy of photobucket.com

If you would by chance happen to knock at my front door and ask to see where I keep my most prized possessions, I would lead you to my upstairs attic, pull the string on the exposed light bulb, and point to a spot along the far wall just beneath the vent leading outside.

There you would see an old toolbox, battered and rusty from years of use. The chipped green paint and rusted hinges may lead you to believe its contents are inconsequential at least and forgotten at most.

You would be wrong.

What's inside that toolbox represent my life's more memorable moments. A gum wrapper, some pine needles, a spent ring from a cap gun, and so on. Like I said, my most prized possessions. Knowing they're up there makes me feel a little more comfortable being down here.

My mother has something similar, though her toolbox is disguised as a hope chest that sits in the corner of her bedroom closet. Inside you'll find old report cards, forgotten toys, and pictures. Lots of pictures.

My father opts to store his keepsakes in the top drawer of his dresser, which had for years been strictly off limits to my prying hands until last week, when I summoned the courage to ask permission to rifle through its contents. I found old coins and older knives, one gun, several bundled letters I did not read, one wooden cross, and more old pictures.

I asked around, and most everyone had their own places for such things hidden somewhere out of sight. People have confessed to stashing their tokens of both past and present in socks and safe deposit boxes, cookie jars and coffee cans. One friend even stored his the old fashioned way—under the mattress of his bed.

Each admitted that no one else would be much interested in their private treasures. Again, none of them could be defined as valuable. Not on the surface, anyway. But beneath? Beneath they were priceless. I could tell they were by the hushed tones and soft smile they would offer along with their confession, as if the telling conveyed some holy secret.

Which I suppose is exactly the case. Handling those relics of the things we hold most dear often takes on the appearance of religious ritual. Touching a memory can be a powerful experience. An old photograph may not represent a mere moment in time, but a token that love is something worth holding onto. And a trinket may not be a trinket, but a symbol that faith does indeed move mountains.

We should consider these things holy. We are, after all, the sum of our experiences. We need those reminders lest we blur our today and cloud our tomorrow. We need to know where we've come from if we're to know where we're going.

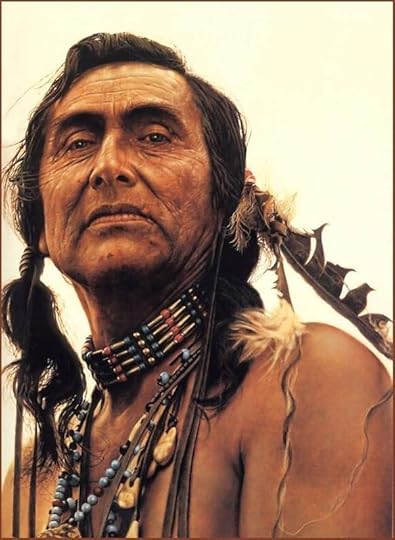

One person I asked had things a little more figured out than the rest of us. A full-blooded Sioux, his people have had much experience in placing great meaning on physical objects. When I asked him where he kept his most precious things, he pulled his T shirt down and pulled out a leather necklace. On the end was a small beaded pouch that was fringed at the bottom.

"Here," he said. "I keep them here."

I told him about my toolbox, about the hopes chest and dresser drawer and socks and coffee cans. I even told him about my friend the mattress stuffer. He nodded and smiled, then said, "We all have our sacred things. But you keep yours hidden and far away. What good will they do you there? Why not keep them visible and close instead?"

I opened my mouth to answer, but nothing came out. He was right. Everyone I had talked to kept their treasures hidden away in the darkness of a chest or drawer. Myself included.

Why? Was it because we felt them too valuable to risk the light of day? Or too fragile to be handled often?

I wasn't sure. But I began thinking about the things our treasures represent, the love and the faith. And I began thinking that often they, too, go hidden and unused. We tuck them away for fear that they are too valuable or fragile, when they are the very things we should carry close to us every day.

Share and Enjoy:

September 14, 2011

"I know you're going to say no, but…"

It was my son who approached me the other night after supper and prefaced his request to go play in the creek with, "I know you're going to say no, but…"

It was my son who approached me the other night after supper and prefaced his request to go play in the creek with, "I know you're going to say no, but…"

He was right, I did say no. It was getting dark, it was already cold, and he had chores to finish and homework to do. But that preface bothered me a little.

"I know you're going to say no, but…"

Meaning I must say no to him a lot. A whole lot.

And that bothered me to the point where I began keeping track of the ratio of yeahs and nopes I give my kids over the course of a normal day. Finished my research the other night. The results were…well, I'm not really sure yet what the results were. All I have is numbers. Their meaning is still up in the air.

According to my calculations, I tell my kids no about ten times a day. Where that fits on the scale of Excessive Parenting is debatable. Even I'm not quite sure. Considering how much I talk to my children, I suppose ten isn't an unreasonable number. But when I consider the fact that for most of the day they're at school and I'm at work, ten sounds like a lot.

In my defense, many of the things my children ask to either have or do are things few parents would allow. Few children should have an elephant as a pet or their own television show or be allowed to dress like thugs and prostitots.

They, of course, do not see the wisdom in my refusals. And I have no doubt I sometimes transform in front of their very eyes from Nice Daddy to Mean Tyrant. Once, my daughter even told me I wasn't cool.

But stripped down to its most bare essentials, saying no is what parenting is all about. I've learned in my nine years of being a father that kids will ask for anything—anything at all—without much thinking involved. Their tiny minds are based on the principle of immediacy. It's now they think about, and seldom later.

That's where I come in. As a father with thirty-nine years of experience in later, I can testify to the wisdom found in keeping one's eyes forward rather than the small amount of space at one's feet. Life has taught me this one thing: everything leads to something else. Everything has a consequence.

I tried a little show and tell about this with my kids once. We were sitting by a pond. I told them to watch as I tossed a rock into the water, then explained how the things we do are like the ripples that come after the toss. They reverberate.

They didn't get the lesson, they just wanted to throw some rocks of their own. To them, it was the splash that mattered. The ripples were inconsequential.

I can't blame them.

I was like that once.

I often still am.

To them, I can be the mean parent who won't let them have any fun. That's okay, because God willing one day they'll be mean parents themselves.

But there's more to this.

The study of my ten-times-a-day No has made me realize I'm somewhat of a hypocritical father. It's not always easy to answer my kids in the negative, but I'm comforted by knowing it's for their benefit. Children need boundaries, and they need to be kept safe. And bottom line, they really don't know what's best for them.

That's why it's a bit disheartening to realize I act like them when it comes to the things I ask for from God.

He tells me no a lot, too. Probably more than ten times a day.

I once thought that was because He didn't love me or because I wasn't good enough. That I wasn't worthy.

I know better now.

The truth is that He does love me, and that both His yes and His no come from that very love. Being good and worthy doesn't matter much. I know it's because I need boundaries and to be kept safe. And because bottom line I really don't know what's best for me.

And that's okay.

Because He does.

Share and Enjoy:

September 12, 2011

The post I almost didn't write

image courtesy of photobucket.com

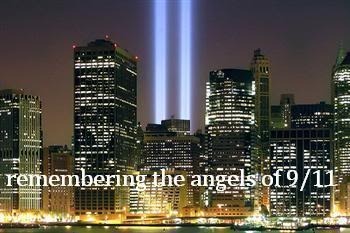

I almost didn't write a post about 9/11 this year. That would've been a first for me since beginning this blog. Sometimes it was a post, sometimes a video, but it was always something. If not on 9/11, then right around that time.

But this time I thought maybe not, even though it's been ten years now. A decade. Anyone else feel as strangely about that as I do? I've read that scientists are studying why it seems that time speeds up as we grow older. Something in the brain, if I remember correctly. Some chemical or a certain pattern of neurons. Regardless, I remember a time when my days seemed to stretch on into forever. Now they pass so quickly. If there is anything I miss about childhood, it's that sense of earthly eternity—that permanence.

That's one reason I wanted to let this 9/11 pass. It feels like only yesterday I sat on the edge of my bed and watched those towers bleed fire and ash. Watched those poor souls jump from stories high, choosing death by gravity over death by immolation. Even now I see them. Those images will haunt me for the rest of my days. But I did not see that yesterday, I saw that ten years ago, and so much has happened since.

Another reason was how politicized the commemoration of 9/11 has become, how over-the-top. I hear religious leaders are not allowed to speak at Ground Zero this year, nor firefighters, nor policemen. I don't understand how that could be. Then again, I don't understand much these days. Sometimes I feel as though we're all galloping toward some final end, and the ones leading the charge are the ones who are supposed to be protecting us.

But mostly, I wanted to let this 9/11 pass because of how strongly I still feel about it. To this day I cannot see an image of those ash-covered people fleeing for their lives or hear Alan Jackson's "Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning)" or be reminded of the phrase "Let's roll" without feeling my eyes sting and my throat tighten. Ten years seems a long time to hang on to such emotions. There comes a point when the mourning must stop and time must continue on. We all must learn to let go. After all, life is a straight line. It isn't a circle.

That's why I didn't want to write anything.

And yet here I am, doing just that.

Because no matter how well-intentioned the people who say it's time to get over it and move on may be, I know I never will. There are some things that should not be whisked away into the haze of our yesterdays to fuse with other memories until it becomes more fiction than fact. There are some stories that should continue to be told and retold not out of a sense of anger, but a sense of honor.

It is human nature to want to set aside pain and cover up old wounds. It is also human nature to hold onto those things because they are a reminder of both the coldness of this world and the faith we must possess to live upon it.

I could forget. I could move on. I could bow my head each September 11 and pause, and then I could move on as if it were any other day.

But I'm afraid if I do I will also forget the men and women who ran toward those flames rather than away.

I will forget an outpouring of love and kindness, of unity, that I had never experienced in my country.

I will forget the stories I heard like the man who believes he was guided to safety by an angel and the man who chose to stay and die in the North Tower rather than abandon his wheelchair-bound friend.

I'm afraid that I will forget not only the horror, but the wonder as well.

Because on that day ten years ago I saw what evil there lurked in the souls of men, and I also saw what grace abides there, too.

Share and Enjoy:

September 7, 2011

When God hates you

image courtesy of photobucket.com

She stared at me, jaw straight and chin high, and said the three words. I stood there looking back at her, my jaw not so straight and my chin normal, not exactly knowing what to say other than to ask her to say it again. In a slow cadence that enunciated perfectly each of the three syllables, she repeated—"God. Hates. Me."

"God hates you because your mail isn't here?" I asked.

"Yes. If He wanted, He could make sure it got here. It's not here. So God hates me."

It was the sort of logic I've gotten accustomed to here at work, a place full of higher learning and lower thinking. And I had no doubt the student in front of me really didn't mean what she said. She was angry. Frustrated. Down.

"You know the mail's backed up," I told her. "The hurricane and all."

"Didn't God make the hurricane?"

"Doesn't the atmosphere or something make the hurricane? Something about the air off the coast of Africa?"

"Doesn't God make the air off the coast of Africa?"

I could see where this was going.

"I don't think God hates you," I said. "The U.S. Postal Service, maybe. But not God."

My attempt at levity did little to resolve the situation. She grunted and walked off. I told her to check back again tomorrow. She said she would if God hadn't killed her by then.

That was yesterday. I didn't see her today—I'm assuming God hasn't killed her—which is good, considering her mail still hasn't arrived. I'm still of the opinion that she was kidding about the whole God-hating-her thing, assuming she knows a little about God. You don't need a lot of knowledge about the Higher Things to know He doesn't hate anyone, that God is love.

But still.

There have been times when I've caught myself thinking that same sort of thing. Maybe not that God hates me, but certainly that He's ignoring me. That He's more concerned with keeping the universe expanding and the world turning than little old me. I suppose that's not as bad as thinking He hates me. I guess it isn't much better, either.

Aren't we all at times like that, though? So much of life is fill-in-the-blank. Things are going badly because _________. Often what we give as our answer is more pessimism than optimism. We hurt and we take sick, we fall on hard times, not because others have done so since time immemorial, but because God hates us.

A few months ago, I got the chance to observe a professional jeweler polish silver. The process charmed me. He walked me through the entire process. The secret, he said, was heat. A good silversmith knows just how hot to get the silver before it is molded. Too hot, and it's ruined. Too cool, and it spoils. The piece he was polishing? Perfect. Just enough heat.

I think God is like that with us. We're made for better things—Higher Things—than to simply exist. We must be good for something. We must be molded in a fire neither too hot nor too cool. We are all pieces of silver in the Jeweler's hand.

It is true this world is cracked and made for suffering. But it is also true that by suffering, we are made to heal what cracks we can.

God does not hate us, He simply loves us too much to fill our lives with ease.

One final thing about that jeweler. He told me he'd been sitting there for hours shining that piece of silver. That fact seemed a bit pointless to me. I couldn't imagine it shining any brighter. I asked him how he would know when it had been polished enough.

"The silver faces the fire," he said, "but it isn't done. Then it is molded and polished, but it still isn't done. The silver is only done when it casts the Jeweler's reflection."

Yes.

Share and Enjoy: