Billy Coffey's Blog, page 2

May 11, 2018

Perfectly Normal

Now well into their teenage years, both of my kids have found themselves stuck in the middle of a problem I can well understand:

Now well into their teenage years, both of my kids have found themselves stuck in the middle of a problem I can well understand:

the only thing worse than standing out among their peers is fitting in.

I’d tell them that’s normal, all part of growing up, and anyway they’re likely to feel some hint of that for the rest of their lives. None of it would do any good. You can’t tell teenagers much. I should know, seeing as how I was one of them once.

Sometimes I’ll catch either one of them looking into a mirror and watch their eyes moving back and forth, up and down, taking in their hair and face and cheeks, how wide their hips are or aren’t. (Don’t let anybody fool you—boys look into mirrors just as much as girls do, and they’re just as picky about what looks back at them.) Though neither one will ever say it, I know what they’re thinking:

Ugh. Look at that hair. That’s stupid hair. Just laying there like some kind of roadkill. And those pimples — sheesh. Gimmie a large pepperoni with extra cheese, will ya. I need more muscle in my arms. My legs are too big. I need makeup. When am I going to start growing whiskers already? I wish I was taller. I wish I was shorter. I wish I could play better/sing better/look better but I can’t, and no one will ever love me because I’m just too normal.

I get it. Like I said—been there myself. And I’m right to say that sort of thinking isn’t going to change for them anytime soon. There are still days when I linger in the mirror and curse my own normalcy. There isn’t much that sets me apart. Normal looks, normal brains, normal talents, normal experience. Just like you. Just like everybody.

In fact, you could say the great majority of people who have ever lived aren’t so special.

Sure, you have your da Vincis and your Beethovens and your Einsteins, your Alexander the Greats, but such people are really few and far between. They come along maybe once every few hundred years to remind us of what we all could be but aren’t. We read about them in books and watch documentaries about their lives and then sit around wondering what’s so wrong with us that we can’t be like them.

Writers are notorious for this sort of thing. We say it’s all about the art. That’s a lie. What it’s really all about is being admired. It’s standing out. It’s putting words on a page that are so pretty and compelling that you stand out from everyone else.

Every writer dreams of not being normal just like every person dreams of not being normal. Because normal sucks.

Adolphe Quetelet may have the answer to all of this. Born in the French Republic on the eve of the nineteenth century, Adolphe ended up building an astronomical observatory in Belgium a few years before revolution took hold in the country. His job was effectively cut when rebel soldiers took control of the observatory. That’s when Adolphe began looking around at people instead of up at the stars.

He began poring over population data collected by governments all over Europe. Studying things like height and weight and general appearance, income and marital status, sorting them all in pursuit of discovering unified rules and models for human behavior.

It worked. Some few short years later, Adolphe Quetelet had succeeded in constructing the idea of what we now consider the average human. You, in other words. And me.

But before you go blaming this poor little Frenchman for all the sorry feelings you harbor for yourself, remember this: Adolphe was a scientist. He was an important astronomer and a highly gifted mathematician (which means he wasn’t very normal at all, I guess) and so could not think in anything more than scientific terms.

In scientific terms, the average of a thing is whatever places it closest to the true value.

And what is true value? Beats me, so I looked it up. Pay attention now, because this is important:

According to the GCSE science dictionary, true value is “the value that would be obtained in an ideal measurement which would have no errors at all. In other words, this is a value that is perfectly accurate.”

Perfectly accurate — I like that phrase. Sort of goes along with Psalm 139, which states that we are “perfectly and wonderfully made.”

Personally, I think Adolphe was onto something. I just might keep him in mind the next time I look into the mirror. Maybe you should, too. Don’t see the wrinkles and the fluffy places and the disappearing hair. Look instead for the true value and then give a nod to the Good Lord above for making you so normal, because that just might mean you’re as close to perfect as possible.

March 29, 2018

The Saturday in between

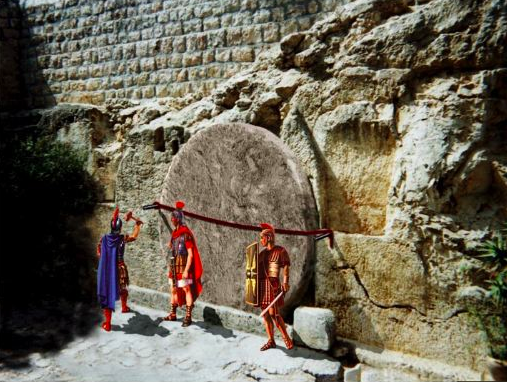

If like me you are counted among the mass of Christians in this country, you consider these seven days among the holiest of the year.

If like me you are counted among the mass of Christians in this country, you consider these seven days among the holiest of the year.I’ve always been a great fan of the Easter season. You slog through yet another seemingly endless winter of bare trees and gray skies thinking things will never get better, and then comes along a day upon which everything turns—your mood, the season, even history itself. Flowers begin to bloom. Trees bud. Daylight stretches a little farther. Life is called forth from death. That is Easter to me.

Church will play an important role in the Coffey home this week. On Friday evening we will gather at a building in town to sing songs of a Man who was more than a man, Whose words of love and forgiveness led to His sufferings upon a cross. It will be a somber service as far as church goes. That is by design. The point will be to put our focus on the sorrows felt by Christ on that long-ago day, as well as the sadness and fear in His followers. At the service’s end, our pastor will stand before the congregation and say,

“Go from this place, for Jesus is dead.”

The sanctuary lights will then dim nearly to dark, leaving us all to feel our way out in shadow.

It’s powerful stuff.

But what will make Friday night’s service even more powerful is the one which will follow on Sunday morning, when we will all gather once more. Gone will be the sadness and the fear, all the shadows. Then will be joy and the light of day. For He is no longer dead, this Jesus. He is risen, and by His wounds we are risen as well.

That is what we believe. What I believe.

You can hold to otherwise, and that’s fine. Plenty who visit this place do not consider themselves religious at all, and I won’t begrudge them one bit. We’re all trying to make sense of this world and our place in it. Christianity is simply the way I make sense of mine.

But that’s not really the point of this piece. What’s struck me this week is the entire range of emotions Easter offers, and how that fits into much of the time we spend in this world. Two days during the Easter holiday receive the bulk of our attention—Good Friday and Easter Sunday. One a time of utter hopelessness and faith dashed, the other a day of unending joy and a hope so real and undeniable that it came to change the world. The gospel accounts share much of those two separate days. Even if you’re not a believer, I encourage you to read them. Yet I’ve often thought something missing from the writings of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. A hole in the narrative I sometimes wish would have been filled.

We know what happened on that first Good Friday. Know what happened that first Easter Sunday. But the Bible is silent on what Jesus’s followers felt and did on the day in between.

That Saturday—that’s what I want to know.

Because when you think about it, that’s where the majority of our lives are lived. We are not so despondent that we have come to know all we once believed as worthless. Our lives do not feel devoid of purpose. Our very foundations have not been shaken. But nor are our days filled with such hope and assuredness that we feel shot through with a love beyond any this world could ever provide.

We don’t spend most of our days in the sorrow of Good Friday or the joy of Easter Sunday. No, most often we find ourselves living in the Saturday in between. Trying to figure out what to do next, what to let go of and what to hold onto. Trying, sometimes, just to get through the day.

It would be nice to know how Mary got through that day. Or Peter or John. But we don’t.

Maybe that’s on purpose, though.

You would think something as important as that Saturday would have been included in scripture. That it isn’t would suggest that maybe it isn’t important at all.

Maybe the point here is that life isn’t supposed to make sense all the time. That all of our questions and pains are here for the purpose of helping us to grow more and better. To become. It is to embrace the mystery of our lives fully and to always be searching. Our days are so often like the end of our Good Friday service at church—just a bunch of bodies groping about in shadow, searching for a way out. That isn’t such a bad thing. You never know what you’ll find while groping about in dim light, whose hand yours will brush against or who’s smile you will meet. What cause you will find to laugh.

The point of that first Saturday is an important one, I think—hang on. Always hang on. Do your work and smile and laugh and hang on.

Because Sunday’s coming.

January 22, 2018

Gently down the stream

My mother passed on early in the morning of January 15, 2018. Her loss will be felt far beyond our family and into our small town where she served as a nurse for thirty-three years. Her service was held this past Friday at a little mountain church not far from home. By the time my daughter sat at the piano and began the first notes of It Is Well, the pews and vestibule were filled to capacity.

My mother passed on early in the morning of January 15, 2018. Her loss will be felt far beyond our family and into our small town where she served as a nurse for thirty-three years. Her service was held this past Friday at a little mountain church not far from home. By the time my daughter sat at the piano and began the first notes of It Is Well, the pews and vestibule were filled to capacity.

She was a good woman and a better mother, the sort of person you could not be around without feeling a little better about yourself and your world. I’ve been asked to publish here the words I spoke that night. Feel free to read as much or as little as you like.

It’s strange, the things that come to mind in a time such as this. Mom wouldn’t want this to be a sad occasion, wouldn’t want us all to sit here long in the face and short in hope. She would rather us leave here smiling out from full hearts, knowing it is well. All is well.

That was my only aim in deciding what to talk about this evening. So when I sat down to decide what I wanted to share with you, I did so reverently. Seriously. I dug through scripture and studied the wisdom of church fathers and philosophers and writers, but the only thing that crept its way into my mind and refused to budge wasn’t a psalm or a proverb or a saying of some great person of faith, it was the beginning of a nursery rhyme:

Row, row, row your boat…

And I thought, Really? That’s all I can come up with?

So I prayed. I said, “God, give me some wisdom here. Give me some direction.”

And I waited. And He answered, “Gently down the stream…”

So I gave up on finding something profound and comforting to tell you, because a nursery rhyme is a ridiculous thing to talk about in a situation like this. I went downstairs and tried again later, and this time I decided to go straight to the source. “Mom,” I said, “I have to do this, now. There’s going to be a lot of people there, Mom, and I want to tell them what you need them to know.

And Mom said, “Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily, Life is but a dream.”

And with that some old dusty drawer long untouched in my mind slid open and out fell a memory, one so clear and sharp that it could have happened mere hours ago instead of forty years—Mom and me riding down the road in her old yellow Camaro, singing that nursery rhyme.

Then other drawers flew open, other memories of other times we would sing that rhyme together: when she tucked me into bed and as we sat on the porch snapping beans, while I sat at the kitchen counter watching her make supper.

Mom taught me that song when I was five, maybe six, and I remembered that I became obsessed with it. Sang it all the time, and Mom would always sing it with me. We’d do it as a round, me starting off alone and Mom starting when I reached the word “stream,” the two of us trying to keep our parts right but never quite making it, leaving us both laughing by the end. I was so young that I thought that was the point of it all—to laugh. Now, I don’t think so. Now I think even those many years ago, Mom was getting us all ready for this night.

I’ve found myself these last days wanting to grab everyone I meet by the shoulders and give them a good shake, tell them “Don’t you know that none of this will last?” We all know that, don’t we? Nothing in this world lasts. But death is something we do our best to cast aside and try to forget. We run from it, ignore it, do all we can to stave it off.

But that doesn’t change the fact that life is a stream we all are set upon, and we begin every day in one spot along that stream and end it a little further along. Those two things are absolute and unchanging. There’s no going back against that current, no floating in place. We can only move forward bit by bit and little by little, on and on and on.

We are each given a boat to move along those waters. Some are large and fancy, others tattered and plain. Mom’s was tiny in some ways, having to hold only a small woman and a small town. She would tell you her boat was somewhat defective—to the day she passed on, she would laugh and blame all of her troubles on Amish inbreeding—but her boat was strong nonetheless, with a good rudder to keep her far from the shallows and the rocky places where so many become stranded. No, Mom lived in the deep part of the stream where the waters are calm and where she could look out and see the beauty and joy in all things. She rowed her boat straight down the middle all her life.

That is an important point to make. Mom rowed. You would perhaps take such a thing as that for granted—if you’re in a boat out in the middle of the stream, of course you have to row. But not all do. Some will stow their oars and sit back and let the current take them wherever, not caring where they go.

My mother was never like that. She was as driven a person as I have ever known, and she believed in work.

I’m not sure at what point nursing became her calling, but I’ve never known anyone more suited for her job. She spent long hours at the doctor’s office in Stuarts Draft, leaving early in the morning and often not returning until past dark, coming in tired and worn not merely from her labor but from shouldering the burdens of her patients. And she did that no matter who you were. When she called your name and led you back to an examining room she did so with a loving firmness—Mom was going to make you step on that scale whether you wanted to or not.

And when she asked you what was wrong, she felt your pains and worries as her own. She was the only person I’ve ever known who would ask, “How are you doing?” not out of social convention or politeness but of genuine concern. Mom wanted to know because that was the only way she could do her part in having you feel better, whether that was taking your temperature or drawing your blood. A smile and a dose of laughter. Or a prayer she would say for you at night that you never knew.

Her job was hard on us, on Dad and my sister and me. Amy and I grew up believing that to go to the store with Mom was some form of punishment. A simple trip for milk and bread to the IGA or the Food Lion would often stretch into hours because everyone knew her and she knew everyone.

There would be someone to greet her in the parking lot and another just inside the door, and then still more as we made our way down the aisles, patients and people from church and longtime friends, and she would make it a point to talk to them all no matter how busy she might have been, asking them how they were getting along and if there was anything she could do to help, because that’s who Mom was and who she remains.

She knew people, you see. Knew the human heart and mind and soul as well as any preacher. Her job taught her that. It didn’t matter how rich you were or how poor, what color you were or what your address happened to be, at some point you were going to get sick and need to see Dr. Hatter, and you’d have to go through my mother first.

She saw people who went down life’s stream bitter and those who went with anger. Some had lost the will to row at all. Still others had come to believe the stream we’re on was meaningless, and that there was only darkness at the end.

Mom always pitied the ones who believed such a thing. She came to understand early that the best way to row down that stream was gently. Gently down the stream. That is how Mom lived. That’s how she treated everyone, friend and stranger and family most of all. That’s how she taught her children, and her grandchildren. “You got to be nice to people,” she would say, “because you never know what they’re going through, and you might be the only bit of Jesus they’ll ever meet.”

That is what people know of Mom—her gentleness. But that certainly isn’t all. So many have called and written and spoke with me these last days about how she always seemed so happy. And she was. I stand here right now and say none of that was an act. But she wasn’t merely happy. She was joyful. Always quick to laugh with a unique ability to find humor in almost anything, and to me that will always be the one quality of hers that I will remember most.

You couldn’t be in a bad mood around her. There were so many times, especially as a teenager, when I would look at her and think, “What is wrong with you? How can you be so happy? Don’t you know how messed up everything is? Here I am barely managing to hang on, and you’re acting like things are great. I’m sulking, but here you are hopping merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily on your way.”

I’ll be honest. There was a time in my life when I was foolish enough to believe my mother lived in a tiny bubble and didn’t know much about the world. I was wrong about that. My mother knew more about living than I ever will. She hurt and endured and yet she remained joyful, and I believe that joy was present not in spite of those trials, but because of them. Mom came to know what so many of us never truly understand, and that is the power and grace and mercy of suffering. It is our nature to avoid hardships yet still they come, and because of our avoiding we don’t know how to deal with them. Mom did, and she did not flinch. She never once lost her joy.

And do you know why? How?

Listen to me, because this is important. This is what she wants you to hear.

Hard times, illnesses, trials, pain, grief. These things come to us all sooner or later. They come upon us like a storm that won’t pass, stripping away one layer of our lives after another until nothing is left but the soul, but those storms can go no further.

That’s what Mom found. That’s what she knew. The world can leave us bruised and maimed, but it cannot touch our souls. Our souls are God’s alone. They are always in His tender care.

And that brings me to my last point. I look out over this room in wonder that a single woman can touch so many lives. I’m not sure how, but I know why. Not long back I ran into a friend who wanted to know how Mom was doing. He said something that I’m sure was meant well. “What Sylvia needs,” he said, “is just a little more faith.”

That was all the proof I needed that he didn’t know my mother at all. You ask me how it was that Mom rowed her boat so well for so long, how she kept to the deep places in the stream so gently, so merrily, I’ll tell you it’s because her faith never wavered. Not once. We are gathered here in this place tonight, we sing her favorite songs, we pray and worship because that was the center of her life.

God never let her down. That is what Mom wants you to know. And she wants you to know that God will never let us down either. He is the one that made this stream we are on. His Son is the water and his Spirit is the current that leads us ever forward and all of it, every single bit of it, is for one purpose.

Love.

It would be easy to dismiss that right now. What I feel, what you feel, very likely doesn’t resemble love at all. And that’s okay.

I am reminded of the story of John the Baptist. At the end of his life he was imprisoned because Herod didn’t like the things John was preaching. John held on as best he could, wasting away a little every lonely day and dark night. Waiting. Praying. And when he couldn’t take anymore, he sent a few of his disciples to Jesus with a simple question.

“Are you the one, or should I wait for another?”

What John the Baptist was asking is this: Are you really the Son of God? Because I’ve spent all this time telling everyone you are, and I could really use you help here. Because I’m in trouble, and I won’t last much longer. Come and save me.”

So his disciples found Jesus, and do you know what Jesus told John’s disciples to go back and say?

Tell John that the blind can now see, the lame can walk, the lepers are healed, the deaf hear, the dead are being raised, and the poor have the good news preached to them.

That’s it.

You can imagine what John’s disciples were thinking. “Well, Jesus, that’s all just great. Really. But we’re just not too sure it’ll make John feel any better about things.”

So they turned to go away, and as they did Jesus said one more thing, saving it for the last because it’s so important: Tell John, he said, that “blessed is the one who does not fall away because of me.”

I’ve probably read that story a hundred times in my life, but the meaning of it never really clicked until this week. John had faith enough when his life was chugging along just fine, but there’s something about a prison cell and impending death that can bring doubts to the most faithful soul.

And that’s what this time feels like to so many of us right now. A cell. Four close walls and no window to see the light. Faith is easy when life is good and things are moving along exactly the way we think they should. But when they don’t? When our days become a prison like John’s, the world shrinks around us, and we are tempted to doubt the very things that are meant to give us strength, and hope, and faith.

Like John, we say, “You sure you’re up there, God? Because I really need you right now, and it feels like you’re not paying attention, and You’re not making much sense at all.”

And God says, “Of course I’m here, and I’m doing things so wonderful that you can’t even imagine them.” Then God says the same thing to us that Jesus said to John’s disciples. “Blessed is the one who does not fall away because of me.”

What does that mean? “Don’t lose faith just because you don’t understand it all. Don’t stumble because you don’t know why things have to be like this for now.”

Because I am working toward something incredible. Because this, all of this, this stream and this current, this life, isn’t all there is. Those we love and lose are never lost at all. They’re not gone, they’re just a little ways farther down the stream. They’re home, waiting for us, ready to celebrate our arrival.

All of that from a nursery rhyme Mom taught me as a boy. All of it true. And the great thing is the last part of that song is the best part, the most comforting. David said in Psalm 17, “when I awake, I shall be satisfied with your likeness.”

Did you get that? It isn’t passing on, its waking up.

David knew too, you see. He knew what Mom knew, and that is what Mom wants us all to know as well.

Life truly is but a dream. So row your boat. Go gently and merrily. Hold dear to Christ, and when you wake you will find what Mom has found: the face of God.

January 11, 2018

Keep warm

Embedded within even the smallest conversation around here are certain customs which are expected to be upheld.

Any inquiry as to your own well-being must be met with “I’m doin’ good,” even if you are not. Especially if you are not. This rule does not apply to your kin, however. If your momma is ill, you can say and should, as likely this will result in some promise of prayer on your momma’s behalf. But if you’re the one sick, that is for someone else to say. You might be coughing up a lung and seeing visions of the dead, but anything other than “I’m doin’ good” will risk word getting out that you’ve turned rude. Lies are part of every interaction. That’s how it’s done.

Complicated, I know.

Chief among these unwritten rules of talk is the salutation one gives upon parting company. Most times, this includes no more than a variation of “goodbye.” (Please, though: if you’re in the Virginia Blue Ridge, don’t ever say “goodbye.” It’s bad enough here to be known as rude, but very much worse to be known as fancy.) “I’ll see ya” is the standard. “Holler at me” also works. “You take care, now” seems a relic of times long past, though we in the mountains are all about relics and so will use this phrase often.

Sometimes a salutation will arise en masse according to some current and dire situation. A system of low pressure stuck over the valley will bring the sage advice to “Stay dry, now.” And there is the always apt “Be careful,” which is not only suitable for any circumstance but also adds a welcome friendly concern. You’ll hear that often, whether at the Food Lion or the Ace or the Dairy Queen. “Be careful” makes you feel good whether you’re the one speaking it or being told.

The past week has given rise to an oldie but a goodie, especially for this time of year. We’ve been below zero for days. Pipes freezing and homes lost to careless fires, extra blankets on the bed and all the dogs inside. So what you’ll hear now is the same for both stranger and friend when ways are parted—“You keep warm.”

Those three words have stuck with me in a way that not even “Be careful” has managed. It’s part plea and part warning with a healthy dose of regard thrown in. Call it a wish for wintertime, January’s version of “Peace on earth, goodwill toward men.”

I’ve read and heard of people who forgo New Year’s resolutions in favor of some word or phrase to base their lives upon for the next twelve months. Hope. Faith. Love. Community. Focus. It can be anything, I guess. I kind of like that idea. My problem is that I’ve never been able to settle on a single thing that could sum up all I wish for others and myself. But I think that’s all been settled now.

You keep warm.

I like it.

That is my prayer for you this year. To keep warm in body but in soul most of all, in heart. To keep loving and hoping and seeing this old world as a beautiful thing worth saving. And I think it’s a fine thing to say to others, because it’s cold out there. All you need is to turn on the news or sit in some coffee shop to know we’re all at each other’s throats. Too much anger and too much hate, too much of those few things about us that are different rather than the many things that are the same.

There’s job stuff to worry about, and all those ills. Kids who grow up overnight. The ones you love most getting sick, getting old. That lump you feel—is that cancer? And what if this Christmas really is the last you’ll spend with your mom, your dad, your husband or wife?

Living is a hard thing. You keep warm.

Pull the ones you love close. Don’t be afraid to say “I love you.” Help a stranger. Take a walk in the woods. Keep warm.

Read a book that will change your life. Seek out beauty. Be good. Turn the other cheek. Always forgive. Sit and be quiet. Don’t be as concerned for present-you as you are for future-you.

Pray. Hope. Believe.

Keep warm.

January 1, 2018

Pub Day: Steal Away Home

The first gift I remember getting was a baseball bat,

one of those giant hollow ones made out of bright blue plastic from down at the Family Dollar. The kind of bat you can’t help but swing and hit something, anything. Dad bought it for me. A single plastic ball, bright white and roughly the size of a coconut, came taped to the handle like an afterthought. Summertime, that’s when it was. Hot sun and a warm breeze. Me with a Spiderman T-shirt and Dad wearing a pair of cut-off shorts, a wad of tobacco in his jaw. Sometime in the mid-70s. Had to have been, because I can still see Dad’s old truck parked in the driveway beside Mom’s yellow Camaro.

And I can see the two of us out on the sidewalk in front of the house, Dad’s hand on my shoulder as he points to a splotch of gray paint on the sidewalk. Him telling me to put my foot right there, hold that bat up behind my shoulder. Get ready. Watch the ball. That pitch coming in slow and easy—“I’m rainbowin’ it,” Dad says—and me shutting my eyes to swing.

I can see all of it, every detail even these many years later.

The memory stands as fresh and clear as the one of me sitting down to my computer just a few minutes ago. Isn’t that strange? We’ve all lived so many moments, each of them recorded on some bit of gray matter in some fold of our brains, yet we’ve forgotten much more of our lives than we can recall. I can’t tell you what I did last Thursday, but I can relive that moment of taking my first swings of a baseball bat forty years ago with such clarity that I may just as well be five years old again.

I’m not sure why some memories are like that, so precise when so many others are subject to fading. But I do have a theory. Those first meetings with people and things which will come to help define our lives are ones we never forget. Those memories shine no matter the distance between when we are and when they happened because we continually return to them, keeping them strong, keeping them shiny.

That’s baseball to me. Always has been.

And I get it if baseball isn’t your thing. Really, I do. The days of every person in the country huddling around the radios in their living rooms to hear a nightly game are gone. It’s all too slow for our fast-paced lives. So much standing around and spitting, so little action. Weird rules. Steroids.

Sure.

But for me baseball was always more. Not merely a game, but my first lessons in everything from poetry to physics, history to religion.

For instance:

The only specifications for a baseball field is the distance between the bases and from the pitcher’s mound to home plate. Meaning the size of a field is limited only to one’s imagination. Meaning, I guess, that a baseball field could technically stretch on into infinity.

And there is no clock to a baseball game, no threat of time expiring. It takes as long as it takes. There must be a winner and a loser. A game perfectly played would last for eternity.

But here’s my favorite: scientifically speaking, hitting a major league fastball is impossible. The time it takes for a 95 mph pitch to reach home plate is shorter than the time it takes for the human eye to register it, much less for the human eye to then coordinate the rest of the body to swing a rounded bat in the correct plane and degree to meet a rounded ball. Meaning that game you might believe is boring really isn’t at all, it is a succession of small miracles unfolding before your very eyes.

Infinity. Eternity. Miracles. Sounds like my kind of thing.

I played baseball all through high school and had designs on playing much longer before life got in the way. That’s a story for later, though. But I still love the game and will upon occasion still wake myself in the night from swinging a bat in my dreams. It seemed inevitable, then, that the day would come when I would write a baseball book. That day is today.

Steal Away Home is my ninth novel (NINE. No wonder I’m so tired) and is out today.

You can learn more about it here.

If you’re a baseball fan, rejoice. You’ll find plenty there to nourish your love of the game. But don’t despair if you don’t know a fielder’s choice from a fungo, because it isn’t about baseball at all deep down, it’s about the things we love and come to depend upon to give our lives meaning, and how all of those things will eventually lead us to ruin unless our love is placed first in the one person who will never let us down.

Go grab you a copy. I promise you’ll love it.

December 21, 2017

Christmas now and then

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

image courtesy of photo bucket.comI write this in the early morning of December 21, four days until Christmas.

The presents have been hidden but not yet wrapped. The tree is up, the lights hung on the house. The tiny plastic wise man who has for so long roamed he downstairs in search of our Nativity remains hopefully (and haplessly) searching. Last I checked, he was perched atop the clock in the living room. Moved there, I will add, by hands not my own. I’ve narrowed the suspects down to a certain daughter and son, and now I’m waiting to see when and where he will move again. That is one of the finer things about having teenagers as children. My kids are too cool for Santa and too sophisticated to go looking for elves. But that plastic wise man on the clock has left me believing they still hold to the magic that is this time, and that I have taught them well enough to know they can do their own small parts in spreading it.

Christmas has snuck up on me this year.

Such a thing has never happened. As a boy, the month between Thanksgiving and Christmas Day was the longest slog imaginable, more difficult even than the month before summer vacation. Back then, the newspaper would publish a little cartoon at the bottom of the front page that included how many days more I had to wait. Thirty seemed an insurmountable number. Twenty wasn’t much better. By the single digits, my parents were praying it would all be over soon. The pace of time was so slow as to be maddening.

But this morning I poured my coffee in shock of the calendar on the refrigerator. The twenty-first? Impossible. How could Christmas get here so fast? Where have I been?

I’ve read that the passage of time feels quicker to adults more than children because of simple math. A month feels like days because I have so many months behind me. The thirty or so days since Thanksgiving comprises only a small percentage of the time I’ve lived, whereas the little kid across the street (the one currently searching for reindeer tracks out in his yard) has fallen to the belief that Christmas will never get here. This past month is a much larger chunk of his life.

It makes a certain amount of sense when you think about it. Still, I’m not wholly buying into the theory. Most people I know will never admit it, but they secretly abhor Christmas. Having to wonder where the money will come from for all those gifts. Having to haul all of those decorations from the attic. The travel. And really, how many times can you hear “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree” before you want to shove an ice pick into your ear?

Family squabbles. Family worries. Realizing you once viewed this time of year with anticipation—“What’s going to happen next!”—and now it’s more the dread of “What’s going to happen next?”

Bah. Humbug.

Believe me, I know. That kid across the street? Give him time. Put a few Christmases behind him, he won’t be out there looking for reindeer tracks. He’ll be the father standing at the door yelling for his kid to get inside. Or he’ll be the neighbor looking from an upstairs window and secretly hoping that maybe there really is a track somewhere. At the edge of the roof, maybe. Santa making a practice run.

Time. That’s what I’m thinking about this year. Where it’s all going and gone.

What tends to trip up so many about Christmas is its insistence on slowing us down and reflecting a little. I can think of no other holiday like it. That’s a tough thing for a lot of us to do. Maybe that’s why we’re so insistent on keeping busy this time of year. We’d rather feel stressed than silent. We’re more comfortable thinking it’s all about what’s happening now rather than what happened then.

That’s it’s about us and not the Child.

We are coming fast upon an occasion so wonderful, so life altering, that the entirety of Western civilization has divided history itself into all that happened before it and all that has happened since. A birth that came not with royal aplomb, but quiet mystery. In four days we will celebrate whatever it is we love most. To some, it will be family. To others, things wrapped in shiny paper. Still more will celebrate nothing at all.

Doesn’t matter. Doesn’t change the fact that baby was born for us all that we may know once and finally that we are not alone, that there exists in each of us a worth and a purpose unimaginable, and that with him we may be battered by life, but never bettered. Love will win in the end. Light has overcome darkness. Dawn will chase away every dark night.

Let it be so.

December 14, 2017

Blessed are those who mourn

So, here’s what happened—

My wife was diagnosed with leukemia. Our daughter continued on with her mostly up but sometimes down battle with Type 1 diabetes. Our son broke his wrist. Mom’s health took a turn for the worse and then the very worse. It all got so bad there for a while that people at work started referring to me as Job. But while things by far have yet to settle down, it is Christmas—my favorite time of the year—and I do have a new book coming soon. And I really missed popping out a blog post every seven days. So here I am, doing my darnedest to get back into the swing of things.

The problem with taking so much time off from a blog is that you have too much to say when you get back. It all tends to get muddled up in the mind. That’s a little of what I’m feeling right now. So instead of one story about one thing, I thought I’d take this bit to share some of the things that have been on my mind.

You remember the story of John the Baptist being put in prison? Herod had reached the limits of his patience with this hillbilly out in the desert and so tossed John in jail to rot (and ultimately to have his head literally served on a platter). While there, John hears reports of all the things his cousin Jesus is doing and sends his disciples to ask Jesus one simple question: Are you really the Son of God? Because I’ve been spending all this time telling everyone you are, and I could really use your help here. For his part, Jesus told John’s disciples to go back and say that the blind now see, the lame walk, the lepers are healed, the deaf hear, the dead are being raised, and the poor have good news preached to them.

And then Jesus adds this, saving it for last because it’s so important.

Tell John, he says, that “blessed is the one who does not fall away because of me.”

I’ve probably read that story a hundred times in my life, yet it never really clicked with me until these last months. John had faith enough when his life was just chugging along—great faith, even—but there’s something about a prison cell and the threat of death that can bring doubts to even the most faithful soul. You sure You’re up there, God? Because I kind of need a miracle right now, and it seems to me You’re just not paying attention. And God says Of course I’m here, and I’m there, and I’m doing things so wonderful that you can’t even imagine it all. But don’t lose faith just because I’m not fitting into the little box you made for me. Don’t stumble because you don’t understand why things have to be like this for now.

A hard lesson for sure, but one my family is learning.

I was walking through town one morning a while back and happened upon an honest-to-goodness professional singer. You wouldn’t know him. He plays a few of the clubs across the mountain on the weekends, that’s all. But he gets paid for doing it, and in my book paid equals professional. I was one street up along a little hill, walking parallel to him and minding my own business. No traffic, no people. That’s when I heard him sing. Rich baritone, smooth as butter. Enough to make me stop and watch. What I noticed is that he would sing when walking by the buildings, then stop whenever he came to an open space like an intersection or an alleyway. It got me so curious that I bumped into him accidentally on purpose a few blocks later to ask what he was doing. Testing his voice, he said. You can’t tell how strong your voice is if you’re singing out in the open. But when you sing while surrounded by something like brick and stone built up so high that it dwarfs you, then you know. Things like that bounce your voice right back to you. You hear your true self rather than the noise in your head.

Maybe that’s a little of what John the Baptist was doing, and me, and maybe you. Testing our voices up against things we can’t move. Finding out who we really are.

You know you’re getting up there in age when all the stars of your childhood start passing on. That’s the first thing I thought when I heard that David Cassidy had died. The Partridge Family ended when I was two, but I grew up with the reruns. Was there anyone cooler than David Cassidy? Nope. He had the looks and the hair and the voice and got to travel around the country in a funky school bus. I remember him on magazine covers and being mobbed by girls. Rich. Famous. What a life.

And yet I read an article last week that mentioned his final words to his daughter. Know what they were?

“So much wasted time.”

Kind of hits you hard, doesn’t it? Especially when you realize everything that man had is everything the world says is necessary to live a good life, and everything most of us are either chasing after or wish we had.

I’ve heard he suffered from dementia at the end. Maybe that was the prison cell David Cassidy found himself in, like John the Baptist. Maybe that’s what allowed him to face the hard truths of his life. Or maybe he just found himself singing into a wall too big and wide for him to get around, and he finally heard his real voice for the first time.

Maybe.

But this I know for certain now, and maybe you know it, too—life can sometimes be a terribly hard thing to endure. Sometimes the things that happen make no sense. But that’s no reason to stumble. No cause to throw your hands up and say it’s all for nothing.

I know it true.

July 21, 2017

A lifetime of stories

I am lost among library stacks when I hear the voice—“Puh . . . puh . . . ”

I am lost among library stacks when I hear the voice—“Puh . . . puh . . . ”—a deep and halting baritone of a man unsure. Two rows over, maybe three. It’s hard to tell with all the books. The beauty of a library is that sense of aloneness you find even when surrounded by so many people. There is no ruckus, little noise. You get to thinking there’s no one else anywhere around, and what can happen in that book you’re after, that author, can seep right out of your mind and across your lips in pieces, like this:

“Puh . . . puh.”

Me, I’m looking for a Ray Bradbury. Even I get into the act (“Brad . . . Brad . . .”) before I find it, there on the bottom shelf. I stoop when I hear, “Puh . . . pig.”

Pig?

Now another voice alongside the man’s, softer and almost grandmotherly: “Yes, very good. Keep going.”

So here I am, crouched in the Ba-Br aisle of the fiction section inside the county library, wondering what I’m going to do. Because I really should mind my own business. Get my book and be on my way. But now the man’s voice is going again—“Kah . . . kah . . . ”—and I don’t want to go on my way, I’ve even forgotten about Ray Bradbury, I only want to know what’s going on. My mother would call it sticking my nose where it doesn’t belong. I call it natural curiosity, which is a vital part of being a writer.

“Cow,” the man says.

And the other: “Excellent! Yes, now the next.”

I stand. Walk out of the aisle past Ba-Br and Ca-Do and all the way beyond Faulkner and O’Connor, where I stop to peek. Sitting at a carrel tucked away in the corner of the room is a white-haired woman in a floral print dress and a man wearing faded khakis and a plain white shirt. In front of the man is a picture book, a bright orange cover with blue letters that spell Let’s Go to the Farm!

The woman leans over, rattling the silver chain fastened to the frames of her glasses. She smiles and waits as what is happening here slowly dawns upon me. This man is learning to read.

You may be surprised. I’m not. Scattered all around these mountains are folks who manage roadways by the shapes of the signs they drive past rather than the letters printed on them. They run their mail over to the neighbors to get the bills read. They sign their receipts with a simple X.

“Huhh. Or . . . ”

This isn’t some hick over there. Not some rube from the holler. He looks like a dad fresh out of the suburbs, a guy who likes to putter around in the garden every weekend before playing eighteen at the country club.

“Orse,” he says. Then: “Horse?”

The way he looks up, it’s like a school kid begging his teacher to nod her head. Eyes wide as though questioning the hope he feels, desperate to know if it’s justified. If it’s real.

“That’s it exactly,” she says. “Well done.”

When the woman smiles, it is as if a dam bursts inside him. The man leans back, creaking the chair, grinning so wide that I grin myself. “Horse,” he says again, looking not at her but at the shelves upon shelves of books around him, a lifetime of stories waiting to be told. Whole worlds to explore. He does not say it, but the words are plain on his face: everything seems so BIG now. So . . . wonderful.

And I stand here peeking around the corner, thinking of everything this man is about to experience. All those characters he is about to meet, all those lands he is about to visit, all those lives he is about to live.

All found within pages of books.

June 15, 2017

Castles in the sand

image courtesy of google images

image courtesy of google imagesFirst you make a hole and labor along the walls to make sure they are thick and tall,

and only after do you build up the center. The order of steps is not negotiable. Most folks—amateurs mostly, at least in my estimation—lead themselves to believe it can be done any way they darn well please, that if they want to start at the center, then at the center is where they’ll start. I look upon these people with a measure of piteous scorn: Forgive them Father, for they know not what they do. Then what I do is sit back and watch as the entire enterprise comes to its slow and inevitable end.

All of which invariably proves my point: there are rules to building a sandcastle as there are rules to living a life. Ignore both to your own peril.

For as much as I act a grown man, being in sight of the ocean tends to unleash the little boy still pent up inside me. Nothing speaks to this more than standing in the midst of miles of untouched beach with a plastic shovel in my hand and a son more than willing to do his part helping (and, as the years have gone on, taking the lead role) in shaping the environment around us into monuments to ourselves.

And I will not kid myself in thinking otherwise. A sandcastle is nothing more than a monument. They are deeply personal things. The shape and diameter of the walls is shaped by our own personalities as much as they are by the implements we use. The depth of the moat and position of the channels designed to divert water away rather than toward. The detail of the turrets and spires. The choice of shells to decorate the sides. My son and I are doing more than building a mere mound of sand, we are staking a claim. Leaving our mark. We are announcing to the wind and sand that we are here.

Of course we know what will happen eventually. You know.

A person has no need of ever seeing the ocean to understand the way of tides. Sooner or later the surf will roll closer and there is nothing—absolutely nothing—we can do to keep our sandcastle safe. No amount of engineering know-how will prevent the water from overcoming our defenses. We know that going in. We build our monuments in full view of white water and cresting waves. We hear their crashing.

We create even while knowing it will be uncreated.

Take a walk down this beach to the end of the island and you’ll discover it isn’t only the sandcastles that are taken. Giant holes dug by children (and men, plenty of men) are gone, too. Messages carved with sticks of driftwood (FREE YOUR MIND; SHE SAID YES; MICHAEL EATS BOOGERS). Shells neatly stacked like cairns pointing the way to a better paradise. Sandbars walked upon mere hours before. All swept away and washed clean without a trace against the Atlantic’s overwhelming power. Say what you want about the ocean bringing a sense of calm and renewal. What you learn most here is that you are a very tiny thing in a very big world, and the big world is often hungry.

Yet that never stops us. Our monuments are whisked away and our marks are obliterated, but still we create.

We tell the world we are here and the world shrugs us away and we tell the world again. Maybe that’s why I love the ocean as much as I do—because it so encapsulates the the sort of lives we all find ourselves living. On a lonely stretch of beach with a child’s shovel we want to know we count, we matter, and that the world would be a little less brighter without us. The waves and brittle sand always disagree.

It’s up to us, then, to decide which is right.

June 8, 2017

Digging in the dirt

Tucked into a corner of my deepest mind is the image of two tiny feet poking up over a wall of dirt.

Tucked into a corner of my deepest mind is the image of two tiny feet poking up over a wall of dirt.Bars of sunlight stretch between the sagging limbs of an ancient pine. My weight is supported by a narrow butt and two small hands sunk deep into a thick blanket of loamy earth. Beside me, the plastic blue blade of a child’s shovel is plunged into a mound of needles and leaves like Excalibur into the stone.

The image is all that remains. Where I happened to be or how old I was or why I had decided to dig a hole simply to sit down in it and gaze out over all creation are questions lost to me. All I can say is that it happened. And if the flavor of that memory is as true as my memory of it, I can also say I enjoyed sitting there a great deal.

It is strange how that image remains so fresh in my mind. So far in my life I have accumulated nearly forty-five years worth of memories, many of which are lost all together and will never be reclaimed. Important events, moments that shaped the person I’ve become, are now nothing more than great gaps of noise to my thinking. And yet the picture of my two feet dangling over the lip of that hole has stuck like a burr in my brain. The fact that it has not budged in all these years leads me to attach some sort of importance to it, as though it means something profound that I am not smart enough or wise enough to understand.

But maybe it’s something much simpler. Maybe that memory remains because I have always been one to crawl around in the dirt and mud.

My people are farmers and mountain folk who would rather be outside than in because outside there is room enough to move and breathe. Here we are raised to believe the ground upon which we tread is the very ground from which we were long ago made, a bit of mud gifted with the touch of the Holy Divine, leaving us to walk upon this earth half fallen and half raised. The caution given me by my parents and grandparents was to never set aside either half of that whole. Lose sight of the holy spark within you, and you’ll become little more than a dumb animal. Forget that you are connected deeply with the wind and rain and mountains, and you’ll live as though all of creation is yours to own rather than borrow for a short time.

That sort of thinking has stuck over the years. Even now, I like my fingers to be stained by earth. I like to dig and plant and find the lonely places. I prefer the feel of grass beneath me to any chair. I would rather lie upon a pallet of boughs than a bed of feathers.

I’ve read that scientists have discovered microbes in soil that serve as an antidepressant on par with drugs such as Prozac.

Natural medicine which enters the body through the nose and the skin. Proof positive that playing outside is good for you.

But it’s more than that. For me, anyway. Getting out in the dirt doesn’t only serve as a reminder that we’re all made of dust and stars. It isn’t merely a link to that long line of kin behind me who made their meager lives by the sweat of their brows and the aches in their backs. What I’m doing in the yard or the garden or the flower beds is acknowledging a part of my own existence that in times past I wanted so desperately to deny, and it is this:

Down in the dirt is where life happens,

right there amongst the mud and muck, and we will never find the means to keep ourselves unsoiled for long. We can try. We can aim to build our lives such that nothing terrible can get through, that we are insulated with stout walls and sturdy roofs that allow no pain to whistle through and no cold to grip us, but in the end this world will always win because it is so big and we are so little.

Best, I think, is to meet this life on its own terms. To get out there and get dirty. Feel the soil on your skin and under your nails and the sweat gathering at your brow. To work and tire and grow sore in your labors knowing all the while that the weeds will return and the grass will grow yet again and it will rain too much or too little but none of it matters in the end, or all of it matters very little.

Because what matters most is not to hide from the world but make yourself present in it, and to dig and dig and dig more.