Billy Coffey's Blog, page 40

June 11, 2012

Life’s soundtrack

You do things when you’re a dad to a girl, things you wouldn’t normally do. Things that under any other circumstances would make me question my very manhood.

You do things when you’re a dad to a girl, things you wouldn’t normally do. Things that under any other circumstances would make me question my very manhood.

Full disclosure: In the ten years since God saw fit to grace this world with my daughter, I have played Barbies and attended tea parties. I have let her douse me with rouge. I have painted her fingernails. I have oohed and ahhed over dresses and skirts and pretty flowers.

I have done all these things.

But I have never, until this day, attended a piano recital.

But here I sit in the sanctuary of my church, left side, middle pew, waiting as patiently as I can for my little girl to take the bench and tickle the ivories.

Thirty people or so have joined me, many of them fathers in their own right. Plenty of grandfathers, too, and of course a full compliment of mothers, grandmothers, aunts, uncles, and what I believe to be a few stragglers who simply followed the crowd inside. All of us gathered together, all of us with strained ears and expressions that alternate between wow and ouch.

And I have to say, so far so good. The first three budding virtuosos have battled admirably. Now it’s my daughter’s turn. She stands, makes her way to the stage with a smile that is part fear and part joy and all happiness, and sits.

She performs three songs—“Merrily We Roll Aong,” “Train’s A-Comin,” and “The Old Clock.” Nothing too complicated, too over-the-top, but slow and easy and good. The right notes are intermingled with only a few clunkers, but she plows on undeterred.

She is rewarded at the end with a round of applause that leaves her red-faced and beaming. She takes her seat with the others and listens attentively.

Me, I’m glad I came. Being here is surely less of a threat than letting her paint my fingernails (which only happened once, mind you, and only because she was sick and needed the distraction and because I love her, so don’t you dare judge me) or playing Barbies. She was nervous about the whole thing, had practiced her songs every night for three weeks to the point where I almost prayed for deafness, but she refused to let fear get the better of her.

I am proud of her. For that, yes, but also for this. For what she’s doing, and for what all of these children are doing.

Because these kids are taking their first steps upon a holy path—to create music.

Seems like a little thing, doesn’t it? After all, we all do it. We sing in the shower and sing in the car and sing at church. We snap our fingers and whistle. We drum our fingers. And who among us hasn’t had occasion to reach for the nearest air guitar?

We’re surrounded by it. It’s on television and the radio, the computer and the phone. Our lives are infused with it.

But it even goes deeper than that. The Aborigines of Australia believe God sang the universe into creation. That might seem crazy on the surface, but there are more than a few physicists who now believe the universe itself is made up of sonic pulses.

In other words, creation has a soundtrack.

Which is why I think my daughter’s onto something. And why I just might go home and ask her to show me a few notes on the piano in our living room. Run the scales, maybe. Maybe teach me “Train’s A-Comin.”

Because the universe might be full of music, but I still think this world needs more of it. As much as we can give it. There are too many tears.

June 7, 2012

Table for two

image courtesy of photobucket.com

The local Outback Steakhouse is Nirvana to the steak-and-potato sort, of which I am a card carrying member.

It is also a favorite for teenagers on their first date, like the couple who was seated in the booth beside ours last week. Bad for them, maybe, but good for us. It’s not often that regular folks like my wife and I get both a dinner and a movie at the same time.

Sixteenish boy and very nervous, trying in vain to impress his classy date and not doing very well at it:

“Sit me first,” she said.

“Okay,” he answered.

“Do I look nice?”

“Yes.”

“Tell me I look nice.”

“You look nice.”

“Mean it.”

“You look nice.”

“That’ll do,” she says. (He breaths a sigh of relief. This is much harder than he thought it would be.) “Now, I order first, then you. Don’t order for me, though. Some ladies like that. I don’t. Did you bring enough money to pay for my food?”

Silence. Then his confession: “I thought you’d pay for your own.”

“No,” came the exasperated answer. “NO. You pay. Always.”

“Okay.”

“Sit up straight. Don’t fidget. Look me in the eyes. Smile.”

“Okay.”

“You’re going to pray, right?” his date asked.

“Um. I dunno. Should I?”

“You’d better,”

And on it went.

I felt sorry for that young man, I really did. He thought dating would be natural. Take a girl out, have some fun, maybe dinner or a movie, and then drive her home. No fuss, no muss. How hard could it be?

From the small beads of sweat on his forehead, plenty hard. His date was demanding. She offered little in the way of praise and much in the way of criticism. He was confused, frightened, and unsure of himself. All because of her. Why had he agreed to take her out in the first place? he wondered. And even asked. But she merely smiled and winked and said it was the only way he’d ever be allowed to take anyone else out ever.

He knew she was right, and so did I. She had all the power, you see. She’d had it for about sixteen years now.

Because his date, this unimpressed, hard, stringent lady, was his mother.

I manage to get the backstory when her son excused himself to the bathroom. Presumably to flush himself down the toilet, which also happened to be right where his evening is headed.

He’s a good boy, according to his mother. Always has been. And she wanted to keep him that way, too. But he’d gotten to that age when children began to feel a little too sure of themselves. Their world brightened and grews bigger, and they were under the impression that they were growing brighter and bigger right along with it. It was easy to get muddled and begin thinking they were in charge. That it was all about them.

So, mother and father decided that before they would allow their son to start dating, he would do a trial run with mom. It’s important that he knows how to treat a lady, she said. And it’s important to know how to spot one, too.

“Understand?” she asked.

Yes.

We pass onto our children what we consider to be the necessities of crafting a good life—the attributes of honesty and hard work, the values of education and faith. But too often what’s left out is the most basic necessity of them all: how to behave when mom and dad aren’t around.

Too many of us mourn the fact that today’s younger generation is so over-the-top rude. Too few of us take the time to consider the fact that much of the fault is our own. It was nice to see a parent put forth just as much effort to ensure her child got into the right life than she would to ensure her child got into the right college.

Education can get you far in life. Good manners can get you farther.

Still, I couldn’t help but express my empathy for the young man.

“This has to be the longest night of his life,” I said.

“Oh, don’t feel sorry for him,” she smiled. “Feel sorry for his sister. She’s fifteen, and her first date is next year. With her father.”

June 4, 2012

Not from concentrate

My family keeps a steady supply of orange juice on hand. Not the kind in a carton or a jug, though. The kind from concentrate. No other form is allowed. My rules.

My family keeps a steady supply of orange juice on hand. Not the kind in a carton or a jug, though. The kind from concentrate. No other form is allowed. My rules.

I know there isn’t much difference between the sort of juice you get from concentrate and the sort of juice you get any other way. Not when it comes to taste, at least. I’ve sampled. No, concentrate is used in our home for another reason. It’s a reminder of sorts, something tangible that helps keep me focused on one of life’s greater truths.

My mother always had orange juice concentrate in the freezer. Easier on the budget, she said. And though my childhood interests tended to involve things far away from the kitchen, I was always around when she made orange juice. The process amazed me.

One frozen tube, small enough to fit into my tiny hand, suddenly transformed into an entire pitcher of juicy goodness? Simply by adding some water? To most, it was a powerful example of human ingenuity endeavoring to make the world a simpler and more orderly place. To me, it was a minor miracle.

Though water seemed to be the magic ingredient, I always thought it an unnecessary step that took a bit away from the finished product. Why bother? Water didn’t taste good. It didn’t taste at all. On the other hand, the stuff in the tube had to be loaded with taste. Sweet, with just a hint of sour. Delicious.

So why not forget the water all together? Why not just serve it right out of the tube?

According to mom, that wasn’t such a good idea. Concentrate on its own was awful, she said. It was too sweet and too powerful. That’s why water was the magic ingredient. It diluted the concentrate and made the juice drinkable.

I never bought that.

One day, alone in the house, I decided to see if she knew what she was talking about. I climbed up on a chair, took the concentrate out, and peeled off the cover. After a few minutes of letting the orange goop thaw in a bowl, I sniffed and smiled. Heaven awaited.

Thinking back, I probably should have taken a sip. Just in case. But I didn’t. I took the biggest gulp I could. Swallowed half of it, too. The other half was launched right back out through a retch that spewed the juice through my mouth and nose and left me teary eyed. I coughed and hacked and, for a moment, almost blacked out.

Mom was wrong. The concentrate wasn’t awful. It was worse.

How could something be so sweet and have too much taste to drink? And how could diluting something so bad make it so good? It didn’t make sense then.

It does now.

Because I’ve spent years wanting a concentrated life. Years on my knees, asking God to help me be and do more. My days were filled with too many mere moments. I wanted defining ones. Moments that lifted me up and rescued me from the hum-drum of life.

And there have been some, to be sure. Like the moment I met my wife. Or when I first held my children. Or the moment I knew beyond all doubt that there was a God Who loved me. But those moments have been surrounded by years of seeming nothingness, when the days seemed to drift by rather than stand out.

I hated those times. A waste of living, I thought. But I’ve learned to think differently. I’ve learned that we may be proven in our defining moments, but we are made in our quiet ones.

Drinking life right out of the tube would sooner wear us down than lift us up. Rather than enjoy its taste, we’d spew it out. It would be too sweet and too powerful to swallow.

Which I think is why God in His infinite wisdom gives our greatest blessings to us over time rather than all at once. Why our days seem to have much more of the same old than the different new. Time, I think, is the magic ingredient. It waters things down. Which is why the wait we mourn for the dreams we have may in fact be His greatest gift.

It makes the living more delicious.

May 31, 2012

One more time

image courtesy of photobucket.com

“This manuscript of yours that has just come back from another editor is a precious package. Don’t consider it rejected. Consider that you’ve addressed it ‘to the editor who can appreciate my work’ and it has simply come back stamped ‘Not at this address’. Just keep looking for the right address.” – Barbara Kingsolver

Writers compare rejection notices like veterans compare war wounds. And that’s appropriate, I think. The two are very similar, evidences of battles not necessarily won or lost or even stalemated, but simply fought. Both begin as a bitter pain that seems unendurable but, with hope and God and perseverance, may become points of pride later.

See this? we say. Got that one three years ago. Hurt like hell, too. Doesn’t really bother me much anymore though, except when it rains.

For the past dozen years or so I’ve kept my rejections in a file folder that’s shoved into the bottom of an old wooden chest in a corner of my office. The chest is both latched and locked, and there are approximately thirty pounds of books stacked on top.

I suppose there is some psychological explanation as to why I keep that folder as far away and inaccessible as possible. I’ve thought about it. The truth is that I still can’t bear to read some of them and still can’t throw away any of them, and both for the same reason—I fear I will lose a little bit of myself in the process.

However.

Last night I took those thirty pounds of books off my chest, unlocked and unlatched it, and dug out my folder. For the simple reason that there are times in a person’s life when he must pause in his forward movement just to see how far down the path he’s come.

I counted fifty-seven. Fifty-seven letters and emails that chronicled a writer who began as a veritable literary idiot then progressed to a rank amateur and then hardened veteran in need of a miracle. There they were, all of them. A picture of my dreams.

Every writer knows rejections come in three different classes. There are the standard form-letter ones, the more personal ones, and, if you’re especially fortunate, ones upon which an actual living human has scrawled a few actual words with an actual pen.

I had a lot of the first, some of the second, and a few of the third.

Some were blunt. I found one in the stack that was simply a return of my query with “No Thanx” scrawled at the top.

There was lot of “We’re sorry, but this book does not fit our publishing interests.” A testament to my lack of proper research.

One of the handwritten comments said, “You are an excellent writer, but unfortunately our calendar for the year is full.” That one got me through another couple months of No Thank yous.

But then I got this one from a newspaper editor: “I cannot in good faith accept this query. To be honest, you’re just not a good writer.”

That one? That one killed me. I quit writing for about three months after reading that.

Some said I was too country. Others that I wasn’t country enough. Some said my words were too simple and my thoughts too erratic, and others said my thoughts were too simple and my words too erratic.

I wasn’t experienced enough.

My platform was lacking.

And on. And on. And on.

F.X. Toole, whose short story Million Dollar Baby became the movie of the same name, gave up writing for boxing when he was a relatively young man. A broken jaw, he said, hurt less than a rejection.

I understand what he meant by that.

And I also understand that the above quote by Barbara Kingsolver sounds wonderful in theory but very, very hard in application. Because it doesn’t matter how hard we try to convince ourselves otherwise, we’ll always fight the temptation to see a rejection as not simply a pass on our book, but a pass on our life.

Go to your local bookstore and you’ll see entire shelves dedicated to the art of getting published. And while many of those books are worthy of attention, the secret is much simpler. Much better.

Write your book. Make it as good as it can be.

And after that, send your queries.

And then, after all that, do one more thing. The most important thing. The one thing you must do no matter how many rejections you get and no matter how discouraged you become.

Always try one more time.

Share and Enjoy:

May 28, 2012

Coming home a hero

Ask him about his medals, and he’ll politely demur—smile and say that he doesn’t really like to talk about them, doesn’t even look at them himself, they’re shoved in a dresser drawer along with some Hanes T shirts and his socks. Not that he isn’t glad to have them. Mostly, it’s because none of them are really his alone. To his thinking, the purple heart was just as much the Afghani insurgent’s who made the IED, and the bronze star should have been given to the five members of his platoon who didn’t make it back.

Ask him about his medals, and he’ll politely demur—smile and say that he doesn’t really like to talk about them, doesn’t even look at them himself, they’re shoved in a dresser drawer along with some Hanes T shirts and his socks. Not that he isn’t glad to have them. Mostly, it’s because none of them are really his alone. To his thinking, the purple heart was just as much the Afghani insurgent’s who made the IED, and the bronze star should have been given to the five members of his platoon who didn’t make it back.

He didn’t bring his legs home, brought instead new ones made of metal and plastic. He’s learning to get around, likes to call himself The Terminator. Sometimes he laughs when he says that. Sometimes he doesn’t.

He says it’s tough coming back to the world. Afghanistan was no paradise (no doubt about that), but things were different there. Life gets stripped down to the barest of essentials in a warzone. You learn to take pleasure in the little things—a hot meal, a cold shower, the sunrise after a long night of firefights and RPG attacks. He’ll tell you that the reason he picked up his weapon every day, the reason he fought, wasn’t so much for freedom or America, but to protect the men and women who fought beside him. To make sure they all came home.

A lot of them didn’t. He has dreams about that sometimes. Sometimes he’ll be running towards his friends, hearing their screams and calls for help, and he says they are awful dreams but at least in those dreams he still has his legs.

He isn’t bitter. He knew what he was signing up for, where he would likely be deployed. His life now is just another challenge, one he’ll meet. I think he’s right. I pray for it. He’s still trying to get used to his new life. Right now, he’s stuck in some sort of earthly purgatory, a thin place between his world before and his world after. He’s finding his way, but the way is hard. Right now, he’s doing some odd jobs, making some home repairs and cutting people’s grass. There’s nothing like the smell of fresh-cut grass, he says. That more than anything else tells him that he’s home.

There’s a lot of talk about heroes nowadays. The term is bandied about with a kind of recklessness, given to everyone from athletes to tornado survivors to political activists. The word “hero” is a lot like the word “love” in that way. It’s used for so many things in so many situations that meaning of the word gets watered down. It loses its power.

But he’s a hero. I have no doubt about that. This man who still dreams of hell and uses a thin, curved piece of heavy plastic to push the gas pedal on his John Deere mower. Who will replace your toilet or paint your living room. This man who left half of himself in the desert for all of us.

This man who’s just trying to find his way.

God bless him.

Share and Enjoy:

May 24, 2012

A writer’s learning curve

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Though the homes in my neighborhood are equipped with modern necessities such as central air and electricity, it’s easy at times to think we sit on the border of unspoiled territory. Because for the most part, we do.

Across the road from my house sits about 30,000 acres of national forest, which is home to all manner of creepy crawlies. The boundary between civilized and not is clearly marked by a nearly straight line of neatly-kept backyards and a foreboding tree line of towering oaks.

Of course, neither man nor beast keeps to his own side. We all mingle with each other from time to time. Miles of trails leading into the mountains provide all a guy like me needs for feed his inner redneck. And as if to even things out a bit, everything from bear to deer to snakes to coyotes have been seen wandering our streets.

Most of us pay little mind to such intrusions, believing that the animals have just as much right to snoop around our homes as we have theirs. But there is one person in particular who is uneasy about the whole thing.

I speak of the kid down the road. Sixteenish and free for the summer. I remember the summer I turned sixteen, three glorious months of getting into more trouble than I’d ever gotten into in my life. Ask his father, and he’ll say he almost wishes his son would get into that same sort of trouble. Not a lot, mind you. But at least a little. After all, he’s sixteen. Trouble’s supposed to find you at that age.

But it hasn’t found him, mostly because he refuses to go outside. His days are spent staring out his bedroom window and writing about what he sees. He wants to write a book, he told his father. He’s serious about it. And while his father is supportive, he also knows it’s an excuse. His son doesn’t like his new home. Doesn’t like the small town or the big woods. He wants to go home to the city.

The family moved here from the city last year as the result of a job transfer. All this wildness suits mom and dad just fine, but not the boy. He woke up one morning in April to find a bear in the backyard. Found a snake on the deck a few weeks later. Though he refuses to admit it, they think it was all just a little too Wild Kingdom for him. So when school let out and he was free to do what he wanted, he retreated to the safety of the indoors.

He says he’s spending his time wisely. He’s writing. Working. There isn’t any time for much of anything else.

I heard about all of this the other night while out for an evening walk. His father was putting up a new mailbox, I stopped to say hello, and things just sort of went from there.

“He really is a good storyteller,” he told me. “Just wish he wouldn’t stay inside all the time. That can’t be healthy, can it?”

No.

Not for a kid. And especially not for a writer.

There are a lot of would-be authors out there who think it’s fine to stare out of their window and write about the world. They take their journey within themselves because they’re unwilling or afraid to go out.

I can’t blame them for that. I was once the kid down the road, too.

Not afraid of bears and snakes, but afraid to go out the door. To face life in all its glory and pain. Give me a nice desk and some paper instead. Let life leave me alone so I could write about it.

Sounds a little strange, doesn’t it? But that’s what I thought. And that’s what a lot of authors think.

There is a learning curve to writing, of course. First come the simple words and simpler thoughts, which through countless hours of practice becomes better words and greater thoughts. No one denies this.

But there is another learning curve to writing that often goes overlooked, and that is the experience of living. Of plunging headlong into life and daring to swim in both the clear and the murky waters, and then using pen and paper as a towel to dry yourself off.

You have to hurt. And suffer. You have to love and hate and believe and doubt. You have to fail and succeed.

And the only way to do that is to go out and live before you come in to write.

Share and Enjoy:

May 21, 2012

The real one percent

She’s gone now—back home, maybe, though with college graduates one cannot be too sure—so since I cannot obtain the necessary permissions, I’ll call her Kim. And I’ll say that Kim is a nice girl (because she really is), though one whose world is covered with that tinge of rose common to most her age. I’ve always found it strange that it’s the young who speak in absolutes and the old who tend to preface their declarations with words like “Maybe.”

She’s gone now—back home, maybe, though with college graduates one cannot be too sure—so since I cannot obtain the necessary permissions, I’ll call her Kim. And I’ll say that Kim is a nice girl (because she really is), though one whose world is covered with that tinge of rose common to most her age. I’ve always found it strange that it’s the young who speak in absolutes and the old who tend to preface their declarations with words like “Maybe.”

Kim, she was always an absolute gal.

Into the whole college experience, too. By which I mean that studying often came after other, more important things. Like protests. Kim was a huge protestor. She told me once that she’d gotten that from her mother, who once burned her bras and marched with the blacks and staged sit-ins to bring the boys back from Vietnam.

Kim had a busy four years. There was the war to protest (both of them, Iraq and Afghanistan, plus she threw in Libya just in case). Darfur. Gay and lesbian rights. Kim went to town on the Trayvon Martin case. That whole thing really made her mad.

But for the past year or so, it’s been this whole Occupy thing. Kim doesn’t like rich people much, doesn’t care for the “privileged” or the “elite,” and I know this for a fact because she told me that, too. She said the banks were ruining this country, and we were all serfs and pawns and slaves to The Man, and she said all of these things while waving her arms wildly at me, and then I quit paying attention to her words because I saw that her armpits had more hair than my own. When a guy like me sees something like that on a girl, focusing on anything else becomes a major problem.

Always one to put actions to her words, Kim went on a humanitarian trip this spring. Three weeks, all of which was spent in Haiti, rebuilding schools and churches and helping to feed and clothe. I was really proud of her for doing that.

I saw Kim last week, three days after she’d gotten back. Our conversation was short (she had a final to take, I had mail to deliver) but informative. She said she had a wonderful time, but it had also been a hard one. Heartbreaking, really. She’d never seen so many people in so much want, never seen such squalor or such pain. And yet she said that the Haitian people are a happy people, quick to smile and slow to anger, and their hospitality was abundant.

She had so many stories to tell, but time enough to only tell me one:

They had spent all day rebuilding the home of a single mother and her five children. The father had lost his life in the earthquake, the mother could not find work, and so the family was forced to scavenge for food and water to sustain them. She had, though, managed to secure a chicken to fix them all supper. She gathered Kim and the people she was with around a barely-there wooden table fed them, then collected the scraps and chicken bones that were left behind.

These, she gave to her children.

Kim said she’d felt sick after, knowing that she’d been fed while her children hadn’t, sick enough that she thought she’d throw up. Her nausea only went away when she realized doing so would be even worse. It would mean that the family’s sacrifice would have gone to waste.

I don’t know what Kim thinks now. Maybe nothing—she’s a college graduate about to enter the real world, so I figure her plate’s pretty full. But I hope she understands now what I think a whole lot of people don’t. There’s a lot of talk about the 99 and the 1 percent in this country, about a yawning gap between the haves and have nots, the middle class getting stymied and the lower class being held down.

But ask Kim now, and I think she’d tell you the truth about all of that. She’s seen want. She’s been around hunger. She understands better what it means to be oppressed. And I bet she’d say that if you call this great land your own, then you have it better than almost anyone else in this world.

You are an American.

You are the 1 percent.

Share and Enjoy:

May 17, 2012

Someday from the other side of the gate

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Back when I decided I wanted to become a writer, I added a “someday” to the end. As in, “I’m going to be a writer someday.” That was what I believed I was supposed to do, what was expected of me. Because no one first starting out writing was a writer. You had to do things first.

You had to have a manuscript, for instance. Or at least be working on one. And you had to have a blog and a “social networking presence”. You had to have followers and friends and readers. An agent. And, of course, a publishing contract.

To me, procuring that last one would be my golden ticket into the chocolate factory. To have a book out, to be published, would eliminate the need for that “someday” I kept adding. I wouldn’t need it anymore. I would be a writer. A real one.

Until that time (and if that time ever came, because I understood the odds), I considered myself merely a wannabe. And those thoughts didn’t change after I had a manuscript and a blog and a “social networking presence” because I saw the writing world as a segregated one. The ones who had books on Amazon and did interviews occupied the castles, and the rest of us were left to beg at the gate for any morsel of acceptance tossed our way. I would pass notes through that gate in the form of queries and proposals to any who ventured close enough, hoping against hope that one of them would pity me and bid me to pass. Theirs was the life I wanted, not my own.

It was tough looking through that gate and watching those published writers gorge on their dreams while I starved on my own.

Every so often someone on my side would be granted entrance. Those were always good times, hopeful times, because everyone left would believe their turn may be next. I would watch as those people crossed over and imagine they were me. Often they would each come close to the gate and talk to the rest of us on the other side. We’d hear amazing stories that would both fill us and leave us hungrier.

I had hope that if I hung around long enough—if I kept knocking—my turn would come. I was right about that. Talent can only get you so far in the publishing business. You have to persist. You have to always try once more.

For proof of that, the gate did open. I found on the other side an agent. And she helped me find a publisher. Amazon and interviews have followed. I thought I would be loosed then. Set free. I suppose in my mind I’d always considered being published akin to shedding my mortal coil in favor of a heavenly body.

That wasn’t true.

There are a lot of writers who change when they go from the land of wanting to be published to the land of author. They think they’ve become someone they’re not because they’re in a place few have been blessed to venture.

I’ve always promised myself that if I were fortunate enough to cross over, I’d stay close to the gate just to see you. Just so you would come close and I could talk to you and say this:

Writing is the most democratic form of expression I know. It doesn’t matter who you are or where you stand in this life, you have a story to tell. One that is just as important, just as needed, as anyone else’s. Being a real writer isn’t a matter of being published, it’s a matter of how you see yourself. It’s a matter of study and work and determination, not a contract.

I found that out.

There is no “someday”. You are a real writer the moment you put pen to page and soak it with your tears and sweat and dare to share yourself with the world. It is that supreme act of courage that gives your life meaning, not a piece of paper to sign and initial at the bottom.

That’s what I will tell you.

And I will tell you this as well—the world on this side of the gate isn’t that different from the world on the other. We strive in each to inspire and transport our reader.

That is our hope and our call.

Share and Enjoy:

May 14, 2012

Everything made fair

image courtesy of bing.com images

At eight, my son is at that age when the world begins to unfold in a way that is both bigger and bitter. It’s exciting—some days he feels like an explorer set loose in a strange and fantastical land. But it’s heartrending, too, because he’s beginning to realize that though strange and fantastical, the world is also mean.

His word—mean. I don’t think I’ve ever heard life described as such, but I think it’s apt. This world does look and feel mean sometimes. It isn’t easy. Many times, it’s not fun. And very often it doesn’t seem much fair at all.

This last point—the unfairness of it all—has been a common topic in our home of late. The Coffey household has had its share of aggravations, most of which are too insignificant to share but matter enough when they’re felt. It’s the little things that make our days bright or sullen, depending upon which way they turn. It all accumulated the other day with my boy, who was forced to miss a friend’s birthday party when he developed a sudden and ferocious cold. Sitting there on the sofa, coughing and snotting and feverish, he looked at me and said,

“Everything should be made fair, cause nothin is.”

Wise words made wiser because they’re true. It was kind of sad to be there when he said that, and not just because he felt so bad when he did. No, what got me was that he was only eight, and he’d just stumbled upon that one great truth. I was hoping that knowledge would continue to elude him, if only for a while longer. We grow up to discover a myriad of unpleasantness in this world, but few are as unwelcomed, as…unfair.

It isn’t fair that some live in want and others in excess. It isn’t fair that some are hungry and others are gluttons. It isn’t fair that a man can’t find a job, or a woman can’t bear a child, or that there are the lonely and the downtrodden, or that war is everywhere and peace is nowhere, or that babies die and the elderly waste away, or that dreams so often go unfulfilled. And it isn’t fair that all of those things happen so, so often, and there doesn’t seem to be any way around it.

If my son had his way, everything would be fair. People would get what they deserved. The world would be a better place.

You could chalk that up to childlike reverie if it weren’t for the fact that a lot of grownups think much the same thing. Fairness is a word we hear a lot of nowadays. It’s repeated by politicians and activists, protestors and pundits. They want to make new rules, they say. Change the order of things. Make it all new again.

They want to make everything fair, cause nothin is.

Me, I’m not sure where I stand on all of this. The notion seems good enough, I guess. I’m just not too sure of the consequences. The whole thing seems a bit too pie-in-the-sky, akin to working towards the goal of every day being Christmas.

Life is inherently hard. That’s what I wanted to tell my son as he sniffled beside me. It’s hard and tough and won’t get easier. And sometimes the more you wish the more disappointment comes, just as sometimes the harder you’ll try the more you’ll fail.

But I held my tongue and let him pour it all out, because sometimes you have to do that, too. You have to get angry and disgusted. You have to lash out. Often, that’s the only way change ever comes.

And who knows, maybe someday everything will be fair. Maybe his is the generation that will change the order of things and make everything new again.

Maybe. Who knows.

But I doubt it. Call me cynical. Because this world isn’t for the weak or the weary, but it’s still the only world we have.

Share and Enjoy:

May 10, 2012

Why not forget?

image courtesy of photobucket.com

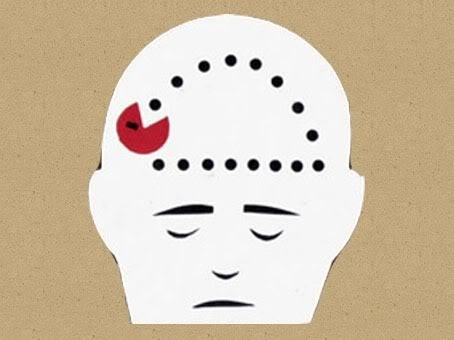

It’s called propranolol. A mouthful, to be sure. The reason why so many medicines have require long, unpronounceable names has always eluded me. I once asked my doctor why such a thing was necessary. He said nothing and looked at me like I was stupid. I don’t think he knew why, either.

Propranolol is a beta blocker, used for everything from cardiac arrhythmias to high blood pressure to controlling migraines in children. A wonder drug with fantastic benefits.

A recent study by Dutch scientists has revealed another fantastic benefit, one that has led to a lot of thinking on my part.

Propranolol, it seems, also dulls memory. Dulls it to the point where these same scientists are boldly predicting a time in the very near future when we could rid our minds of bad memories all together.

Sounds wonderful, doesn’t it? To get rid of all those nasty reminders of the bad moments in our lives. It certainly sounds wonderful to me. Much of my daily life is still lived in the past, whether knowingly or not. It’s fingers still grip me. Loosely perhaps, but enough that I still feel them. Feel them in my decisions and reactions and worries.

And I’m sure I’m not alone. I dare say that I’m not the only one who carries around a little excess baggage. So why not lighten that load a little? Why not forget?

I can certainly see the value in such a therapy being used to treat those suffering from some form of post-traumatic stress: victims of abuse or soldiers returning from war come to mind. These people are particularly prone to the agonies of bearing what may well be an unbearable weight. Such memories can lead not only to depression and psychosis, but even death.

But what about the rest of us? The ones who are plagued not by horrendous moments, but horrendous decisions? Are our bad memories made less so because they are not as powerful? Because they foster more guilt and regret than terror and numbness?

I’m not so sure.

We are largely the product of our experience, the end result of the countless choices and innumerable decisions. Many of those choices and decisions were good. Many were bad. But both worked together in an intricate and holy dance that has culminated in bringing us to both here and now.

But what if that dance were interrupted? Would we truly be made whole if those bad memories were taken from us, or would we somehow become less than we should?

Would the lessons we’ve learned from our mistakes be dulled along with the memories? And so would we then be doomed to repeat them?

Is there value in the things that haunt us?

That’s the question. One worth pondering, too.

We don’t mind accepting that the good in our lives was ordained by God. I’ve never doubted that my wife, my children, and my job are gifts from heaven. They provide my life with a healthy dose of meaning. They have purpose.

But if the good God has given us is endowed with meaning and purpose, then shouldn’t also the bad? And can we, with our limited vision and understanding, really label something as “good” or “bad” in the first place? How can we know for sure until the end result of our lives is played out and our story is done?

The blessings of my wife and children and job were born of horrible memories of the person I once was. It is because of those bad memories that I realize, finally, how blessed I am now. I love these things not because of the goodness I enjoy now, but because of the bad I suffered through then. Because the bad taught me what mattered. Would I give those memories back? No. Because I think the grace that has been given to me would be lessened in the forgetting. Because forgetting the pain of who I was then would dull the joy in Whose I am now.

We are all scarred by life. No one leaves this world as perfect as we entered it. But it is those very scars that shame us that make us all the more beautiful in God’s eyes. Rather than hide them, He beckons us to give them to Him.

Better than forgetting our memories is surrendering them. Better than pushing them down is lifting them up.

Share and Enjoy: