Billy Coffey's Blog, page 33

February 21, 2013

Wait and move

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I want it known before I begin this post that but for a small handful of people, I do not grumble. Ever. It is a Coffey tradition steeped in Southern Redneckness—you do not whine. The reasoning behind this is both simple and teeming with most of the truth you need to get by in this world—life is tough on all of us. We all have our own stories and our own problems, and we’re all trying to get by the best we can. Therefore, complaining helps no one.

That said, my shoulder hurts.

A few weeks ago I was ambushed by a slab of ice that was cleverly disguised as snow, bruising my knee and spraining my shoulder in the process. The sprain further aggravated an ancient yet lingering rotator cuff problem from my baseball days, which basically rendered the entire right side of my body useless. I was pathetic for a week. Ask anyone.

Both my doctor and the nice folks in the local hospital’s radiology department concluded it was nothing truly serious. A good thing. In fact, I’ve been promised that I’ll soon be back to my normal self. Assuming that I do two things:

Wait and move.

The waiting is simply that. Waiting. Time heals all wounds, and apparently this holds true for busted shoulders as well. Which means full-contact sports are not an option, which is bad, but they’re not an option for now, which is good.

And as far as the moving goes, I have exercises to do. Stupid ones. Things like moving my fingers up the wall and swinging my arm in front of my like I’m pretending to be an elephant. Things designed to make me look as ridiculous as possible and thus be a fount of endless entertainment for my children.

But I’m following orders, if only because I know that by doing so I’ll get better. My wound will be gone.

Since I’m the type of guy who tends to philosophize about everything (and since I couldn’t really do anything else except watch reruns of The Dukes of Hazard), I spent a lot of time those seven days pondering my condition. I’ve come to realize there is a spiritual component to all of this. You can take a tumble on the inside just as easily as you can take one on the outside. Both hurt much the same, and both sorts of falls can be cured in the same way.

For instance.

It hurts more when you fall at forty than when you fell at seventeen. At least that was true for me. Either my body has gotten softer in the last twenty years, or the ground harder. Neither case is appealing. Such are the ravages of time. The body adds weight over the years, and not all of it is cushion.

The soul tends to add weight, too. A tumble there hurts more at forty than at seventeen too, and for the same reasons—either the heart has gotten softer or the world harder. The more you live the more you feel, and the more you feel the more likely you’ll get hurt. It’s unfortunate, yes. But the alternative to feeling too much is to feel too little. Ironically, that ends up hurting even more.

Most people think stumbles happen when you’re not paying attention. While that’s true sometimes, it isn’t always. I was paying attention (promise). But the problem was disguised. A thin layer of fallen snow had covered the ice, rendering it invisible until it was too late.

Which is why I do my best not to stand in judgment of whomever is unlucky enough to find themselves on the cover of the latest tabloids in the supermarket checkout lines. No matter how well we pay attention to our hearts or our heads, sooner or later life sneaks up on us all. Legend has it that when Jesus stooped down to write in the sand between the adulteress and those who wished to stone her, what He scribbled were the secret sins of everyone who held a rock in their hand.

I really like that.

We all need to wait and move. We all need to have patience, both with others and ourselves, and we all need to exercise our wounds to make them better.

We can think or act however we want, but the truth is that we’re all clumsy. The truth is that grace is given to us because we do not possess it ourselves.

February 18, 2013

The Art of Rejection

“This manuscript of yours that has just come back from another editor is a precious package. Don’t consider it rejected. Consider that you’ve addressed it ‘to the editor who can appreciate my work’ and it has simply come back stamped ‘Not at this address’. Just keep looking for the right address.” – Barbara Kingsolver

“This manuscript of yours that has just come back from another editor is a precious package. Don’t consider it rejected. Consider that you’ve addressed it ‘to the editor who can appreciate my work’ and it has simply come back stamped ‘Not at this address’. Just keep looking for the right address.” – Barbara Kingsolver

Writers compare rejection notices like veterans compare war wounds. And that’s appropriate, I think. The two are very similar, evidences of battles not necessarily won or lost or even stalemated, but simply fought. Both begin as a bitter pain that seems unendurable but, with hope and God and perseverance, may become points of pride later.

See this? we say. Got that one three years ago. Hurt like hell, too. Doesn’t really bother me much anymore though, except when it rains.

For the past dozen years or so I’ve kept my rejections in a file folder that’s shoved into the bottom of an old wooden chest in a corner of my office. The chest is both latched and locked, and there are approximately thirty pounds of books stacked on top.

I suppose there is some psychological explanation as to why I keep that folder as far away and inaccessible as possible. I’ve thought about it. The truth is that I still can’t bear to read some of them and still can’t throw away any of them, and both for the same reason—I fear I will lose a little bit of myself in the process.

However.

Last night I took those thirty pounds of books off my chest, unlocked and unlatched it, and dug out my folder. For the simple reason that there are times in a person’s life when he must pause in his forward movement just to see how far down the path he’s come.

I counted fifty-seven. Fifty-seven letters and emails that chronicled a writer who began as a veritable literary idiot then progressed to a rank amateur and then hardened veteran in need of a miracle. There they were, all of them. A picture of my dreams.

Every writer knows rejections come in three different classes. There are the standard form-letter ones, the more personal ones, and, if you’re especially fortunate, ones upon which an actual living human has scrawled a few actual words with an actual pen.

I had a lot of the first, some of the second, and a few of the third.

Some were blunt. I found one in the stack that was simply a return of my query with “No Thanx” scrawled at the top.

There was lot of “We’re sorry, but this book does not fit our publishing interests.” A testament to my lack of proper research.

One of the handwritten comments said, “You are an excellent writer, but unfortunately our calendar for the year is full.” That one got me through another couple months of No Thank yous.

But then I got this one from a newspaper editor: “I cannot in good faith accept this query. To be honest, you’re just not a good writer.”

That one? That one killed me. I quit writing for about three months after reading that.

Some said I was too country. Others that I wasn’t country enough. Some said my words were too simple and my thoughts too erratic, and others said my thoughts were too simple and my words too erratic.

I wasn’t experienced enough.

My platform was lacking.

And on. And on. And on.

F.X. Toole, whose short story “Million Dollar Baby” became the movie of the same name, gave up writing for boxing when he was a relatively young man. A broken jaw, he said, hurt less than a rejection.

I understand what he meant by that.

And I also understand that the above quote by Barbara Kingsolver sounds wonderful in theory but very, very hard in application. Because it doesn’t matter how hard we try to convince ourselves otherwise, we’ll always fight the temptation to see a rejection as not simply a pass on our book, but a pass on our life.

Go to your local bookstore and you’ll see entire shelves dedicated to the art of getting published. And while many of those books are worthy of attention, the secret is much simpler. Much better.

Write your book. Make it as good as it can be.

And after that, send your queries.

And then, after all that, do one more thing. The most important thing. The one thing you must do no matter how many rejections you get and no matter how discouraged you become.

Always try one more time.

February 14, 2013

ILUVME

I was sitting at an intersection yesterday, passing the time between stop and go by studying the car in front of me. Vehicle: a rusty, broken, and tired Toyota. Driver: young lady, no more than seventeen and blissfully unaware of her surroundings. A sound system that was worth much more than the car itself vibrated everything from the windows to the doors to the license plates.

I was sitting at an intersection yesterday, passing the time between stop and go by studying the car in front of me. Vehicle: a rusty, broken, and tired Toyota. Driver: young lady, no more than seventeen and blissfully unaware of her surroundings. A sound system that was worth much more than the car itself vibrated everything from the windows to the doors to the license plates.

Vanity plates, of course. If you’re seventeen and cool, vanity plates are a requirement.

They also say a lot about a person. Vanity plates are tiny windows into a personality, a creative assemblage of letters and numbers that offer a glimpse into what matters most to the owner.

And it was pretty obvious what mattered most to that young lady. Her license plate used the term “vanity” in a more literal way.

ILUVME, it said.

I shook my head and grinned in an I-can’t-believe-this sort of way. ILUVME? Really?

A little arrogant, I thought. Then again, maybe there was much to love in being her. Maybe she really did love herself, and justifiably so. Maybe who she was, what she knew, and the direction her life was going was so perfect, so wondrous, that loving herself was natural and right and good.

Ha.

If true, then she should give herself a little time. Five years or so. Maybe ten. Let her grow up a little and get out into this big, beautiful world. Let her dreams crumble, her heart break, and her faith bend. Then we’ll see how much she loves herself.

I wrinkled my brow, struck by the coldness of those thoughts. Was I really that pessimistic of a person? Was I really hoping for her life to unfold such that she would one day regret putting such a thing on her license plates?

Why was I so upset because she loved herself? Was it because she possessed something I did not?

Did I love me?

An interesting question, that. Are we supposed to love ourselves? I flipped through the pages of my mental Bible for any scripture that confirmed or denied that question, but nothing stood out (though, admittedly, the pages of the Bible I hold in my head are not nearly as complete as the pages of the one I hold in my hand).

But I did know this: whether I was supposed to or not, I certainly did not love me. I knew my weaknesses and faults. The hidden things I thought and said and did. I knew what I paid attention to and what I did not. The struggles I faced, the times I feared and worried and doubted too much. What and who I hated. I knew, more than anyone else, the kind of person I was.

And that was not the sort of person anyone could love. Should love.

Besides, the point of life isn’t to be content with the person you are, right? No, it’s to try to do and be a little better every day. To keep becoming. That’s tough to do when you’re happy with who you are. When ULUVU.

Still, something bothered me. Wouldn’t hating yourself for who you are, for what you feel and think and do, be just as bad?

My thoughts were interrupted by the stoplight turning green. ILUVME turned left, and as I watched her I realized she was pulling into the parking lot of a church. Black letters that spelled out GOD IS OUR FRIEND glittered in the sun on the marquee at the entrance.

Yes. God is our friend. My friend. So powerful that He could do anything, He chose to die for me. So omnipresent that He could be anywhere, He chose to live in my heart. My heart. Not because He had to. Because He wanted to.

Because God loved me.

Loved me despite knowing my fears and worries and doubts. Despite knowing my failures and faults. Despite knowing me better than I knew myself.

If an all-powerful, all-knowing God could love me, why couldn’t I? Why shouldn’t I?

The foundation of the Christian faith states that we are flawed beings. Sinful souls in need of a Savior. I knew that to be true. Perhaps just as true, though, was that our worth didn’t depend upon what we did or did not, but upon the spark of the Divine that gave us life. There is a beauty within us beyond our flaws and failures. A beauty worthy of our compassion, of our acceptance.

And of our love.

February 11, 2013

The cost of failed dreams

I don’t think of him often, only on days like today. You know those days. The kind you spend looking more inside than around, wondering where all the time is going and why everything seems to be leaving you behind. Those are not fun days. In the words of the teenager who lives on the corner, they’re “the sucks.”

I had a day like that today. It was all the sucks. And like I often do, I thought of him.

I’ve been conducting an informal survey over the years that involves everyone from friends to acquaintances to strangers on the street. It’s not scientific in any way and is more for the benefit of my own curiosity than anything else. I ask them one question, nothing more—Are you doing what you most want to do with your life?

By and large, the answer I usually get is no. Doesn’t matter who I ask, either. Man or woman, rich or poor, famous or not. My wife the teacher has always wanted to be a counselor. My trash man says he’d rather be a bounty hunter (and really, I can’t blame him). A professor at work? He wants to be a farmer. And on and on.

Most times that question from me leads to questions from them, and in my explaining I’ll bring him up.

Because, really, he was no different than any of us. He had dreams. Ambitions. And—to his mind, anyway—a gift. The world is wide and full of magic when we’re young. It lends itself to dreaming. We believe we can become anything we wish; odds, however great, don’t play into the equation. So we want to be actresses and painters and poets. We want to be astronauts and writers and business owners. Because when we’re young, anything is possible. It’s only when we grow up that believing gets hard.

He wanted to be an artist. I’m no art critic and never will be, but I’ve seen his paintings. Honestly? They’re not bad. Better than I could manage, anyway.

His parents died when he was young. He took his inheritance and moved to the city to live and study, hoping to get into college. The money didn’t last long, though. Often he’d be forced to sleep in homeless shelters and under bridges. His first try for admission into the art academy didn’t end well. He failed the test. He tried again a year later. He failed that one, too.

His drawing ability, according to the admissions director, was “unsatisfactory.” He lacked the technical skills and wasn’t very creative, often copying most of his ideas from other artists. Nor was he a particularly hard worker. “Lazy” was also a word bandied about.

Like a lot of us, he wanted the success without the work. Also like a lot of us, he believed the road to that success would have no potholes, no U-turns. No dark nights of the soul.

He still dabbled in art as the years went on. But by then he had entered politics, and the slow descent of his life had begun. He was adored for a time. Worshipped, even. In his mind, he was the most powerful man in the world. Because of his politics, an estimated 11 million people died. I’d call that powerful.

But really, Hitler always just wanted to be an artist. That he gave up his dream and became a monster is a tiny footnote in a larger, darker story, but it is an important one. He didn’t count on dreams being so hard, though. That was his undoing. He didn’t understand that the journey from where we are to where we want to be isn’t a matter of getting there, it’s a matter of growing there. You have to endure the ones who say you never will. You have to suffer that stripping away. You have to face your doubts. Not so we may be proven worthy of our dreams, but so our dreams may be proven worthy of us.

He didn’t understand any of that. Or maybe he understood it and decided his own dream wasn’t worth the effort. Painting—creating—isn’t ever an easy thing. That blank canvas stares back at you, and its gaze is hard. That is why reaching your goals is so hard. That’s why it takes so much. Because it’s easier to begin a world war than to face a blank canvas.

February 7, 2013

Pick your cause

The college where I work is a great place filled with great people. The campus is beautiful, the professors excellent, and the staff both accommodating and friendly.

The college where I work is a great place filled with great people. The campus is beautiful, the professors excellent, and the staff both accommodating and friendly.

But it is still a college. And as it is such, my work environment harbors the sort of modern, liberal predilections that a more traditional person like me can’t seem to understand sometimes. Some days, many days, I am both generally exasperated and specifically confused by what I see.

A few weeks ago the college held what is annually billed as Pick Your Cause Week. Each day brought exhibits, lectures, and a wealth of information concerning a particular organization or subject. This year children of alcoholics, muscular dystrophy, women’s cancers, domestic violence, and the poor were chosen.

Though there are some things here at work that I find questionable and a few I find just plain strange, I like this. I like it a lot. We should all have a Pick Your Cause Week.

I find it sadly ironic that in this age of computers and satellite television, when the smallest event that happens in the smallest corner of the smallest country on the other side of the world can be instantly beamed right into our living rooms, we’ve really never been so separated from one another.

The media blitzes us with a constant barrage of suffering and need. We see footage of disaster and crime and hear stories of loss and despair. And though we try every day to nourish whatever hope we have and coax it to grow, there is the daily reminder that our world seems to be teetering on the edge of a very dark abyss and there is nothing that can pull it back onto solid ground.

It all can be just a little too much to bear. For me, anyway.

So I do what a good Christian should. I pray. But I’ve found that I often use prayer as an excuse, a poor example of doing something. As much as I pray for this world and all the people in it, I find that I do little else about it. And while those prayers are vital, they shouldn’t be the final solution. Asking God to help the world and asking Him to equip me to help the world are two different things. I don’t often get that.

I have a tendency to shrink the world. Shrink it so its dimensions extend no further than the small part I happen to occupy. Shrink it to only that which affects me. My world is my family and my town and my work. Whatever else that happens outside of my world that is sad and regrettable and unfortunate affects me emotionally. But it is also none of my business. I try to ignore it. I don’t hope it will go away because I don’t think it ever will, I just try to stay out of its way and hope it doesn’t find me or the ones I care about.

All of that is of course the silliest thing any Christian should ever believe, and yet I do. And so do a lot of us. We all at some point fall for the great lie that there is nothing we can do about the state of things, and in doing so we risk developing a mindset that is perhaps as unchristian as we can get:

We don’t care what happens so long as it doesn’t happen to us.

That is why a Cause is so important. We are all called to spend our time and energy toward something that will continue on long after we leave this world. It is our purpose, our mission. No matter who we are or what we do or where our talents lie, we are all here for the same reason: to make things better.

To heal the wounded. Clothe the naked. Feed the poor. To offer help to the helpless and hope to the hopeless.

And the light of God to the darkness.

February 4, 2013

My wandering eyes

Photo by photobucket.com

Writers are always hungry for compelling topics to explore. The problem is that the best ones are mortifying.

—Ralph Keys, The Courage to Write

Despite their claims to the contrary, I really do listen when people are speaking to me. I know what they are saying and why they are saying it. I understand the points they’re trying to make or the things they’re trying to share. I’m a great listener, though that’s usually proven after the fact. During, though, is something else entirely.

Everyone from friends to family have said it’s because of my eyes. Evidently at the beginning of a conversation they’re directed outwardly toward the person to whom I’m speaking. But then there always seems to come an inevitable point at which they seem to either almost turn inward or outward even further, off into some other place as if I’ve lost interest. I assure them that’s not the case at all, and it isn’t. I am genuinely interested in what people have to say to me. Though I must say that interest has a bit of selfishness to it.

Those who know me well and talk to me often have come to accept all of this as an aspect of my passion rather than a flaw of my character. They see my eyes, know what’s going on behind them, and understand that it’s something I cannot help. It’s at that point when they all utter the same four-word question that, if answered in the affirmative, allows them some understanding and me the alleviation of guilt:

“You’re writing, aren’t you?”

The answer is always yes, I am writing. It’s a question and an answer that does not depend upon location, either. If someone in my family were to peek in the door right now and ask that question, my answer to them would be both obvious and understandable. I’m sitting at my desk with my coffee, my computer, and a stack of books. Of course I’m writing.

But where family and friends sometimes stumble is with this one simple yet profound truth—a writer is always writing. It is not merely a job and never a hobby. It is not something that can be picked up and then placed down at will. Writing is a jealous spouse or a rare flower—it demands your constant attention.

And you will give it willingly, if only because you are just as jealous of it. Writing and the writer are locked in an eternal embrace that is part devotion and part fear the one will wander too far from the other. That is why a writer is always writing. Why life itself appears not as a blank page, but one that is a hodgepodge of words that need to be ordered so the story can shine through.

It’s also the reason for my wandering eyes. There is a friendly separation between writer and world. Life unfolds itself upon the stage and the author is its audience, there not merely to applaud but to take note. Writers are the true historians. We lay a foundation of the present upon which the future can be built. That’s why every conversation, every circumstance, everything, is approached under the assumption that it’s something that can be written about.

Because, really, anything can be written about. Not because nothing is sacred, but because everything is.

That’s why a writer is always working. Always trying to piece together the next story or scene, always trying to find the wisdom in the moment.

Which leads to a curious question.

If all of what I’ve said is true—and I believe it is—can anything truly bad happen to a writer? Is there any situation, any event, that with time and healing cannot be put to the page?

I’ve yet to answer that question for myself. Have you?

January 31, 2013

Patrick’s price

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Sit Patrick down beside his senior picture in the yearbook, you’d swear he graduated only a couple weeks ago. If I told you the truth, you’d scrunch your brow in one of those looks that says Huh-uh, no way. Then I’d tell you I wasn’t lying, because I’m not—Patrick graduated fifteen years ago.

Still looks like a kid, though. Still has that longish hair boys seem to want to keep now, still engaged in a war of attrition with patches of acne on his cheeks. It’s almost like Patrick slipped into some kind of crack in time way back and has just now found his way out.

But that’s not the case. He’s been around. I’ve seen him.

He still lives at home, though not with his parents. They’ve passed on. It was rough on Patrick just as it would be rough on any of us. His parents left him the house in their will, he’s the owner now, but he still sleeps in his old room and refuses to claim the master bedroom. Patrick’s momma used to tease him whenever he sat on their bed, saying that was the very spot where he was conceived. That thought has never left Patrick’s mind. He says there’s not enough Tide in the world to clean those sheets enough for him to lie there at night.

I guess you could say he has a good life. Steady job, place to live, food on the table. Patrick says he’s free. I suppose he is in some ways. He comes and goes as he wishes and is beholden to none but the Lord, whom he dutifully greets most mornings and every Sunday. He has friends, and though he’ll blush and shrug when you ask him, I have on good notice that women have called on him. That seems to be the one flaw in Patrick’s life, more or less. He’s say that’s true.

He’s seen thirty years come and go. Some people pay little mind to such things and Patrick would count himself among them, but I’m not sure. Whether we pay attention or not to the ticking of that great clock in us all doesn’t really matter I guess, because it ticks on anyway. This moment is both the oldest we’ve ever been and the youngest we’ll ever be from here on out. I think Patrick understands that, even if he’ll never say it.

He likes to talk about how he’s the only one of his friends who’s never been married and divorced. A smile will always come along behind those words, as though he’s happy to say them. Patrick will say he’s not made for matrimony, just like Paul the missionary. Paul was too busy living to settle down. Patrick reckons he’s the same. Besides, he says, why go through all the trouble of loving if it’s just going to fall apart in the end? Why give that best piece of yourself to someone who’s just going to up and move on without you one day? Doesn’t matter if that person ends up on the other side of town (as his friend’s wives have done) or on the other side of the ground (like his parents).

No, doesn’t make much sense going that far. Safer to keep your heart in your own chest, where it belongs. Patrick says that’s why he still looks so young, because he’s still whole and hasn’t given half of himself away. He says it’s easier to go your own way like that. To be free.

Maybe. And on the surface, I suppose he has some good points. But then again, life is never promised to be a safe thing, is it? We may come into this world unscratched, but we leave it with all manner of scars. Risk is worth the pain, I think. That’s how you grow. Trying and failing is better than not trying at all, whether it’s love or a dream. It can hurt (oh, how it can hurt), but I’d still rather look old and haggard than young and untouched by life’s thistles.

January 28, 2013

Real Simple

image courtesy of photobucket.com

It wasn’t the proximity of the magazine (right there on the table beside me) that caught my eye, it was the title. And since there is little else one can do in a doctor’s waiting room than leaf through germ-riddled periodicals, I did just that.

Real Simple, it read.

Though I’ve since learned it’s quite the popular publication, I had no idea it existed. Did not even know such a subject had been deemed to interesting as to devote an entire magazine to it. My wife has corrected my ignorance on the matter. She said simple is in now. Simple is cool.

Now that I’ve thought about it, I can understand why. It’s a mess out there in the big, wide world. All that shouting and pointing of fingers, all that angst and unease. There was a time not too long ago when most people felt we were all charging headlong into the future, and the future was going to be a wonderful place. No more war, no more hunger, no more want and hurt. Science and technology was going to save us from ourselves.

I think it’s safe to say that’s not really the case anymore. I think a lot of us are beginning to see that we certainly are charging headlong, but the future isn’t as bright as it once was. That our science and technology might help us a great deal, but it also sucks our time and, in the process, maybe a little bit of our souls. Everything seems so complicated, and that same hidden part of us that whispers a random cough might be a building cold is whispering that complicated isn’t good, complicated makes things harder. And the cure for complicated? Simple.

I think of a relative of mine living up in the mountains. A simple man with a simple home. Woodstove for heat, well for water. He doesn’t have much, but he has what he needs and is all the better for it. Sometimes I think riches are best measured not in how much of something we have, but how much of something we can let go of.

Snow is falling just outside my window right now. The smart man on the radio doesn’t really know how much will end up on the roads and grass, only that it will be “measureable.” And even now I can see men and women coming home after a long day with gallons of milk and loaves of bread in their hands. I’ve written before about how and why people turn to the basics when the world bares its teeth. I think the same applies here.

There is much to be said for simplifying things, of cutting back and trimming down. Let’s face it, ours is an imminently blessed nation to call home, and as a result we have an overabundance of stuff we could really do without. And by that, I mean things we possess and things that possess us, things on our outsides and others inside. Because most of us don’t just own a lot, we carry a lot as well.

I’m still on the fence with a resolution for this year. Maybe simplifying my life fits the bill. Maybe instead of getting more, I’ll give more. Maybe instead of hanging on, I’ll let go. Maybe we should all get back to the basics. Maybe getting away from them is the cause of much of the world’s hurts.

January 24, 2013

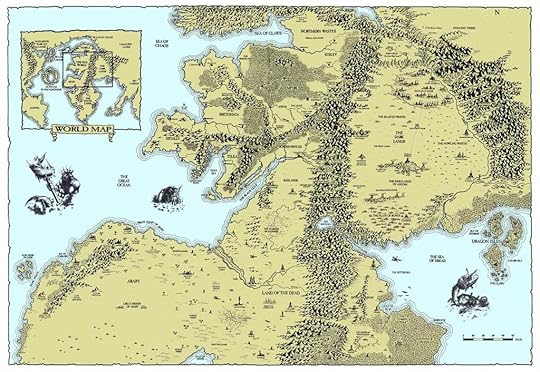

There still be dragons

image courtesy of photobucket.com

My maternal grandparents were Amish/Mennonite. To this day I don’t exactly know how to write those two words, if they should be separated by a slash or a dash or some other form of punctuation. I suppose it doesn’t matter so long as you understand this one important point—when I stayed there, I had to entertain myself.

No television. No radio. No electronic games. Nothing.

It wasn’t all bad. Strip away all those technological whiz-bangs we surround ourselves with, and what’s left is real life. Sunshine and sweet breezes and garden dirt. That’s what became my childhood. And books. Lots and lots of books.

My grandfather’s den was where I’d mostly hole up when the weather was cold or wet. An old recliner, a massive roll top desk, and shelves of books. One in particular was always the first I’d reach for—a giant volume of ancient maps. Europe, Asia, the Americas, darkest Africa. I loved poring over those old things. To this day, I believe that’s where my love of all things mysterious began.

I have my own collection of books now, complete with my own volume of old maps. Replicas of those drawn by explorers and seafarers from a time when the world was wider and deeper. I still take that book down from time to time, just to think and imagine. That’s what the best books do.

My daughter was wondering about the Pacific the other day. Something about school. I came up here to my office and brought out my book of old maps, she reached for the Google Earth app on my iPad. Sometimes the space between generations seems more a chasm than a span.

We sat together on the sofa, she swiping and pinching the screen, me turning the pages and tilting the spine. She saw detailed photos of remote and uninhabited islands surrounded by clear waters. I saw vast stretches of faded emptiness pockmarked with mermaids and swelling waves.

She leaned on my shoulder and pointed to a spot in the bottom corner of the page. Coiled there was a serpent, mouth open to devour. “What’s that, Daddy?”

“That’s where nobody’d gone yet. They used to mark those places with pictures like that. Sometimes, they’d just write ‘Here There Be Dragons.’”

“Why?”

“Because it was a mystery. Something had to be there, I guess. Why not a dragon?”

My daughter went back to her screen. She couldn’t find any dragons on Google Earth. I figured she wouldn’t. We don’t think there are any mysteries in the world anymore. Everything’s been mapped and plotted by satellites whizzing above our heads. We think we have all the answers, know exactly where we are. There was a time when the center of the world was Jerusalem or Rome or London. No more. Thanks to GPS and Google Maps, the center of the world is wherever we happen to be. I suppose that’s pretty empowering in a way. And sad.

It’s worth mentioning that there are still plenty of dragons in the world. Only 2 percent of the ocean floor has been explored. Thousands of new plants and animals are discovered every year. Just recently, a group of scientists stumbled into a hidden valley in New Guinea that had never been seen before. The animals didn’t even run and hide from them. They had no reason to. They’d never seen a human before.

If there is anything I want my kids to know, it’s that there’s still plenty out there for us to find. I want them to love the mystery of life just as much as their father does. I want them to bask in the unknown. I want them to ponder it and find their places in its midst.

January 22, 2013

Man versus parent

image courtesy of photobucket.com

This is me sitting on the front porch. Cup of coffee in one hand, a book in the other. Ignoring both, because my son is currently riding his bike up and down our quiet street.

He’s been out there for about the last twenty minutes. My son is eight now. When you’re eight and you’re a boy, bike riding becomes something of an art. The training wheels are long gone, as is that awkward stage of trying and mostly failing to find that tiny point of balance. Speed is what matters now, and awesomeness. The first is self-explanatory. The second involves such things as zooming past while pedaling backwards and making that clickclickclick sound with the chain. Or zooming past with your legs splayed out to the sides. Or with only one hand on the bars.

He just rode past again, trying an awkward combination of two of the three—“Hey Daddy, look!”

I am. I say good job. And I hope he’s far enough away that he can’t see the look of utter terror on my face.

Twenty minutes he’s been out here. I’ve been out here for ten. And for the last five of those ten minutes, I have realized he’s not wearing his helmet. It’s sitting on my truck, placed there like an oversized hood ornament.

“HEY DADDY LOOK!” Screaming past again, one hand high over his head.

My first instinct, wild and deep and urgent, was to yell for him to get his tiny butt back here and get your helmet on because don’t you see it’s dangerous out there? You could fall and crack your head right open and there would be blood, BLOOD, and don’t you think it can’t happen because all it takes is a pebble in the road that catches your tire or a puff of cold wind that gets in your eyes.

That’s what I wanted to tell him. And still do.

But then he flew past the house for the first time with his head high, the wind tousling his hair, laughing as he stood on the pedals and pumped. And I realized that was me so many years ago. That was me on some long-lost Saturday morning, happy and free.

I’ve sat here since in this old rocking chair with my coffee and my book, trying to decide what to do.

The parent in me says safety always comes first. The parent sees that wayward pebble in the middle of the road and how fast my son is going. The parent understand things like taking your grip away from the handlebars is not only risky, it’s downright stupid. That person can already see my son wobbling just before he falls, and can already hear the first convulsive yelps of a skinned knee.

But the man in me begs my tongue to stay put and say nothing. Because my son is flying. He is in space fighting aliens or in a cockpit shooting down the enemy. He’s a superhero chasing the bad guys. And besides, a helmet may be able to prevent a great many things, but it sometimes takes more than it gives. You can’t feel the wind in your hair with a helmet on. You can’t hear the birds sing or the climbs clack in the trees. You can’t be free.

Maybe.

I don’t know if the parent or the man will win this argument. Secretly, I’m hoping my son will get tired soon and come in for a while. It would preserve both my head and my heart.

One thing really is true, though. It is dangerous out there. That makes things like helmets absolutely necessary.

Things like laughter in the face of it, too.