Billy Coffey's Blog, page 30

June 3, 2013

The poor folk

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I ask Larry if he’s still watching over the poor folk every time I see him, and every time he says yes. He says yes and then offers me one of those nods that are accompanied by pursed lips. You know, the kind of expression that means it’s tough to look but you have to anyway. Someone’s got to watch over them, Larry says, and it might as well be him. Especially since he was poor once.

He’ll tell me he still watches over them from the same place, right across the river from the big building where they like to gather. Not a pretty sight—Larry will tell me that too, and always—but one worth watching nonetheless, if only for the education the sight provides. “There but for the grace of God,” he’ll say, and then he’ll nod and purse his lips again.

He says there have been times in the past when he’s taken the bridge across the river and gone to see them. Or tried. The poor folk will sometimes entertain Larry’s presence for a while. He was after all one of them once, and the poor folk are mannerly on the outside even if they are lost inward. They’ll say hello and how-you-doing and come-on-in. Larry will hello them back and say he’s fine, just fine. But he never goes in the big building. He’s been in there too many times in his life, he’ll tell me, and he’s seen all there is to be seen. I guess that’s true enough, but sometimes I think Larry’s afraid he’ll catch the poor again, like it’s some sort of communicable disease spread by contact.

Better than driving across the bridge to say hello is to stay on the other side of the river and watch. That’s what he tells me. It’s sort of a warning, though it’s one I don’t need. To be honest, I don’t have much of a desire to be around the poor folk. I like it where I am, right here with Larry and the rich people. Maybe I’m afraid I’ll catch poor, too. Maybe deep down I think they’ll sneeze on me.

Larry says he has God to thank for being rich now, and when he says this he won’t nod and purse his lips. He’s much more apt to pat the rust spot on his old truck—a ’95 Ford from down at the local car lot, which was a steal at $5,000—or take off his greasy cap as a sign of respect for invoking the Almighty. Yesir, Larry will say, God stripped away all of his poor and made him rich. I guess that’s nothing new in a time when a lot of people think God’s sole purpose in the universe is to shower down hundred dollar bills on everyone who’s washed in the blood of the Lamb.

Sometimes I’ll ask him if the people who gather at the big building across the river are all poor. Surely there are a few rich ones mixed in. He’ll tell me yes, there are a few rich ones, but they’re rare. Once he said I’d just as soon go in the big building looking for a unicorn as I would a rich person. I laughed at that. I think it was the way he’d said it—“Yooney-corn.”

Still, curiosity kicked in. I had to find out for myself.

I drove up to the big building one town over, careful to park across the river as Larry suggested. Lines of cars filled the parking lot—from my vantage point, I saw seven Mercedes, half a dozen BMWs, and three Jaguars. I watched patrons adorned in fancy dresses and pressed suits go in for dinner, watched the golf and tennis players come out.

Larry’s poor folk.

He was once one of them (it was the Mercedes and the golf for Larry, the fancy dress for his wife, and the tennis for his kids). They were at the country club five days a week and sometimes six, depending on how busy they all were. He’ll say he swore he was rich. But then came the recession followed by the job loss, and suddenly the Mercedes was gone (replaced by the truck, a steal at five grand) and so was the country club.

That’s when God showed Larry that what he thought was riches was really poverty. That’s when Larry found that wealth is better measured in love and family and simple things.

Larry says he never knew how poor he was because all that money got in the way. Now he says he’s the richest man in the county.

I think he might be right.

***

If you haven’t signed up to receive blog posts via email, there’s still time to receive a coupon for 30% When Mockingbirds Sing which comes out June 11. (next week!)

May 30, 2013

Lesser prayers

image courtesy of photobucket.com

The prayer request portion of Sunday school class is the reason why we never seem to get much Sunday schooling done. And that’s not a knock against me or anyone else there. We have a fine class, a fine teacher, and a fine time probing the depths of the Good Book. Secretly, though, I suspect many of us spend most of that first half hour of class fidgeting and sighing so we can get to the good part. The part that, whether stated or not, means a little more.

A few Sundays ago the teacher wrapped up his lesson early, allowing those so inclined a full twenty minutes to spill their guts and tell everyone the happenings in the days of their lives.

“Prayer requests?” he asked.

Hands shot up. The teacher would call a name or nod to a person, going one by one through the room and taking notes, which would be distributed the next week on our official prayer request sheets.

Yes. We take this seriously.

Our space was then transformed from classroom to confessional as secret pains and worries were flung out into the light to be prodded and prayed over.

The lady two seats down from me was the first to raise her hand but not to be chosen. She lowered her hand and waited her turn. The one chosen began to speak on soft and muffled words of the tests she was to get in the coming week that would reveal whether she had cancer or not.

A couple near the front had just learned they were going to be parents. It was their fourth try, they said. The first three pregnancies had resulted in miscarriages.

One man was losing his job.

Another man was still looking for one.

One woman said her teenage son came home drunk two nights before and threatened her. She’d been staying with her sister since, afraid to go home.

A mother and father had a son who’d just been given his traveling orders for Afghanistan. “Pray he shoots straight and ducks,” the father said.

Another couple had a friend who’s son had just come home from Iraq. The funeral would be the next day.

A car accident had taken the life of a seventeen-year-old son of a preacher in the next town.

A woman buckled under the grief of a marriage in tatters.

And on. And on.

And through it all, the woman two seats down would raise her hand and wait her turn, lowering it when the Sunday school teacher had called upon someone else, scribbling both name and note on the paper.

After ten minutes, her hand went into the air slower and with a little more hesitation. After fifteen, her hand wasn’t raised at all.

I found her in the hallway afterward and said hello. Then I mentioned the lack of time and the abundance of prayer requests in class, and that it was a shame she never got to share hers.

“If you’d like,” I said, “you can tell me what it was. My family and I will pray.”

She looked at me and offered a small smile.

“I’m not sure,” she said. “I guess it’s not that important. I lost my necklace, you see. It’s just one of those cheap silver crosses that you can pick up at the Christian bookstore for about five dollars, but it meant the world to me. My son gave it to me for my birthday last year. Saved up his allowance for almost a whole month.” She paused and than added, “I just don’t know what I’m going to do if I don’t find it.”

I nodded.

“It seemed so important at the time,” she said. “But then came all those other things people needed praying for, cancer and war and death. So many are hurting now. My problems just didn’t seem that great after that.”

I nodded again. I understood, I really did. But she was wrong.

She was called away before I could tell her what I was thinking. What I thought she really needed to hear.

She’s right, of course. There are so many hurting now, and for so many reasons. But I for one believe that doesn’t mean one person’s problems are greater than another’s. Not to God.

To God, at that moment the only thing in the universe that mattered was that she had lost her necklace. Just like the only thing in the universe that mattered was one son going to war and another coming home, and a family dissolving, and a car accident, and a threatened mother.

Humility is an important thing to feel. We need to know the world doesn’t revolve around us.

But the love of God is an important thing to feel, too. And we also need to know that.

May 27, 2013

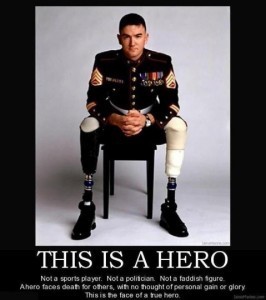

Coming home a hero

Ask him about his medals, and he’ll politely demur—smile and say that he doesn’t really like to talk about them, doesn’t even look at them himself, they’re shoved in a dresser drawer along with some Hanes T shirts and his socks. Not that he isn’t glad to have them. Mostly, it’s because none of them are really his alone. To his thinking, the purple heart was just as much the Afghani insurgent’s who made the IED, and the bronze star should have been given to the five members of his platoon who didn’t make it back.

Ask him about his medals, and he’ll politely demur—smile and say that he doesn’t really like to talk about them, doesn’t even look at them himself, they’re shoved in a dresser drawer along with some Hanes T shirts and his socks. Not that he isn’t glad to have them. Mostly, it’s because none of them are really his alone. To his thinking, the purple heart was just as much the Afghani insurgent’s who made the IED, and the bronze star should have been given to the five members of his platoon who didn’t make it back.

He didn’t bring his legs home, brought instead new ones made of metal and plastic. He’s learning to get around, likes to call himself The Terminator. Sometimes he laughs when he says that. Sometimes he doesn’t.

He says it’s tough coming back to the world. Afghanistan was no paradise (no doubt about that), but things were different there. Life gets stripped down to the barest of essentials in a warzone. You learn to take pleasure in the little things—a hot meal, a cold shower, the sunrise after a long night of firefights and RPG attacks. He’ll tell you that the reason he picked up his weapon every day, the reason he fought, wasn’t so much for freedom or America, but to protect the men and women who fought beside him. To make sure they all came home.

A lot of them didn’t. He has dreams about that sometimes. Sometimes he’ll be running towards his friends, hearing their screams and calls for help, and he says they are awful dreams but at least in those dreams he still has his legs.

He isn’t bitter. He knew what he was signing up for, where he would likely be deployed. His life now is just another challenge, one he’ll meet. I think he’s right. I pray for it. He’s still trying to get used to his new life. Right now, he’s stuck in some sort of earthly purgatory, a thin place between his world before and his world after. He’s finding his way, but the way is hard. Right now, he’s doing some odd jobs, making some home repairs and cutting people’s grass. There’s nothing like the smell of fresh-cut grass, he says. That more than anything else tells him that he’s home.

There’s a lot of talk about heroes nowadays. The term is bandied about with a kind of recklessness, given to everyone from athletes to tornado survivors to political activists. The word “hero” is a lot like the word “love” in that way. It’s used for so many things in so many situations that meaning of the word gets watered down. It loses its power.

But he’s a hero. I have no doubt about that. This man who still dreams of hell and uses a thin, curved piece of heavy plastic to push the gas pedal on his John Deere mower. Who will replace your toilet or paint your living room. This man who left half of himself in the desert for all of us.

This man who’s just trying to find his way.

God bless him.

May 23, 2013

Weep with those who weep

Image courtesy of Google Images, photo by Sue Ogrocki, AP

It’s the father I think of most, his picture I still see in my head. Sitting on that faded lawn chair in the midst of all that rubble, head buried in two shaking, dirt-stained hands. Sobbing. Waiting for his young son to answer.

He’d been there for hours, combing through what the tornado had left behind. Shouting his son’s name, calling him home. What remained of the elementary school in Moore, Oklahoma, was little more than piles of twisted wood and steel. Still, he believed his son would be found. Other children had been pulled from the wreckage, why not his?

But as the hours drew on and the shouts dwindled, what hope he had began to fade. His son was still somewhere in there. His boy. That thought—the sheer, horrible knowing—was enough to hollow out what was left of his heart. As I sat there in the comfort of my living room, surrounded not only by a whole house but a whole family as well, I watched the tearful reporter say this man would not leave until his son was found. Alive or dead.

We cannot escape these stories. We hear them on the news and read them in the paper. We see accounts of the dead and the survivors online. The news is everywhere now, as close as the phone in your pocket. Maybe that’s why I’m still thinking of that father some three days later. Or maybe it’s simply because I have a son as well.

He’s gone now, I suppose. The last I heard was that everyone had been found and all the bodies recovered. Twenty-four people died in Moore, ten of them children. I suppose his son was among them.

But I still see that father there, sobbing in that chair.

Pray for them. That’s what I’ve heard, and from everywhere. It’s what the governor of Oklahoma said—“We need prayers.” They do. We all do. And in the days and weeks to come, what will happen in Moore is what happens so often in this country in times of need and catastrophe. Friends and strangers will open their hearts and their pocketbooks. Streets will flood with volunteers. The rebuilding will begin.

Ask that broken father, he’ll probably agree with all of that. Then he’ll probably say it’s much easier to rebuild a town than to rebuild a life.

Pray for Oklahoma. I’ve said those words myself. I’ve read the thoughts of many with regards to what that tornado meant and where God was and why He allowed it. Me, I’ve written nothing. A part of me feels like no one else should have, either. We don’t know where God was. We don’t know what He was thinking. And honestly? If that were me sitting in a lawn chair, screaming for my son? If all those pontificators would have come to me and said it was all for some greater purpose? That God won’t give me more than I can handle? I would’ve strangled each and every one of them.

I saw this Facebook comment in a recent article: “If prayer works, there wouldn’t be a disaster in the first place. So please keep your religion to yourself.”

Not true, of course. Prayer is a mystery designed to change us more than our circumstances, and we accomplish nothing by denying that God is sovereign over all. But I understood the sentiment. A part of me was even tempted to share it. But keeping my religion to myself? No.

We don’t need less of God now. Now, we need Him more.

I wouldn’t have told any of this to that father. I wouldn’t have wanted to hear it myself. Not then. What I would have done was just sit. I would have called out his son’s name and I would have wept along with him, because we need to weep with those who weep. That requires no answers and no empty platitudes, only a heart willing to be broken so that on one far day it may be filled once more with hope.

May 22, 2013

A writer’s constant companion

Karen Spears Zacharias is one of my favorite people in the world.

Karen Spears Zacharias is one of my favorite people in the world.

I have a guest post over at her place today on writing and fears. Come say hi!

May 21, 2013

A God with sharp edges

I’m also posting today over at Prodigal magazine about the God of sharp edges. I wish my relationship with God was a more steady one. A more . . . peaceful . . . one. To a large extent it is now. That hasn’t always been the case. Head on over there to see why.

image courtesy of photobucket.com

There’s also an opportunity to win one of ten copies of When Mockingbirds Sing.

May 15, 2013

The story behind the story: a video chat

Though I’m much more comfortable in front of a page than in front of a camera, I thought I’d do something a little different for the blog today.

I’ve heard there is always a little truth in every work of fiction. That goes for every book I write, but my next one maybe especially. There’s a personal story behind When Mockingbirds Sing. This is it:

May 13, 2013

Fisher of men

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Next time I won’t order the fish. That’s what I thought after he left. If I would have ordered chicken or steak or shrimp I would have gotten my food earlier, which meant I would have prayed earlier, which meant he wouldn’t have seen me. But he did, and like they say, that is that.

Lunch time for me is a sort of take-it-when-you-can thing that depends on how busy I am and how far I want to drive. Most of the time that places me inside a small restaurant downtown, just a few blocks from my work. Nice place with nice food. Very friendly, very tasty, and very quick.

So. The fish.

An extra ten minutes, the waitress said. “You sure you don’t mind waiting?”

No.

The man came in five minutes later and was shown to the table across from mine. We smiled and nodded like friendly folk do, and I was fairly certain that would be the extent of our interaction. It wasn’t. Because soon afterward my fish arrived and I offered a very silent and inconspicuous prayer.

He was staring at me when I opened my eyes.

“So you’re a churchgoer?” he asked.

“Yep,” I answered. “You?”

“Never,” he said in a tone that seemed rather proud.

I nodded and went back to eating.

“Don’t believe in God myself,” he said. “Just seems like a waste. I guess that means I’m going to hell, huh?”

I’d been around long enough to know when I was being baited into a conversation I really didn’t want to get into. This, I thought, was one of those conversations.

So I just said “Not my call” and raised another bite of fish.

“Not your call,” he repeated. “That’s typical.”

I chewed and thought about the last little bit of what he said. It was more bait, of course. And it was still a conversation I didn’t want to have. But maybe it was now one I should.

“Typical?” I asked.

“Yeah, typical. You people like to use those pat little answers for questions you just don’t know or are just too afraid to face.”

“Like whether you’re going to hell?” I asked.

“Sure. That just bugs me. Christians say that God is love, but if you don’t go along with the program then you get eternally punished. That doesn’t sound like love to me, that just sounds hypocritical.”

I shrugged. “Not really. I reckon God’s spent—what, fifty years or so?—trying to get you to pay attention to Him. He’s arranged circumstances, given you a glimpse of things you don’t normally see or think about, even spoke to you. There’s no telling how many chances you’ve gotten to say ‘Hello’ to God after He’d said the same to you. But you have a choice. That’s how He made you. You can choose to listen or not, choose to believe or not, choose to accept or not. I take it that so far, it’s been not. So if you spend your whole life telling God to stay as far away from you as possible, He’s gentleman enough to do just that when it’s all over. So yes, I suppose if you keeled over right here right now, you’d go to hell. But it’s not me who’s gonna send you there, and it’s not God either. It’s you.”

He looked at me. I looked back.

“Alright then,” he said.

We both continued our meals. Ten minutes later he squared his tab with the waitress and left, pausing at the door to offer me a smile and a tip of his hat.

The waitress focused on me then, asking if I’d like more coffee or just the check. I asked for a check and an answer.

“That fella come in here a lot?”

“Sure,” she said. “He’s the preacher at the church next door.”

“He’s the what?” I asked her.

“The preacher.” Then she smiled and added, “Was he havin’ a little fun with you?”

“Don’t know if I’d call it fun.”

“He likes that,” she said. “Likes finding people who call themselves Christians and tests them. Sees if they know their faith or just accept it. These days we have to be ready to defend it, don’t we?”

“We do,” I said.

And that’s the truth. It isn’t enough to just accept our faith nowadays. We have to stand for it. And this is the truth, too—next time I go there to eat, I’m ordering the fish. Maybe he’ll stop by.

May 9, 2013

The Happy Gas Theory

image courtesy of photobucket.com

It’s May, and that means both good and bad things around here. Good in that the school year is almost over for my kids. Bad in that it still quite isn’t. That’s why my son said something about the happy gas last night.

Here’s where he got that:

He was six when he got his tonsils out. It wasn’t the visit to the hospital that worried him. He was okay with the hospital. And it wasn’t even the pain. What worried him the most was the very thing he most looked forward to.

The happy gas.

It’s tough trying to explain a medical procedure to a six-year-old, especially when the ins and outs are pretty vague to his father. I didn’t really know what tonsils and adenoids were, what function they served, or why they were giving him such trouble. But the anesthesia part I knew.

So I told him he got to wear a mask like Batman did and that the air would smell like cotton candy and he’d fall asleep. And while he was asleep the doctors would do their business and make him better.

“You won’t feel a thing,” I told him. “Promise.”

He didn’t believe me.

Experience had taught him otherwise. He’d slept before, and he’d either done things or had things happen that he not only remembered, but felt.

He fell out of the bed twice. Felt that. Bopped his face against the headboard. Felt that, too. He’s also awakened himself by burping, talking, snoring, and coughing. Sometimes all at once.

No way, he thought, no way, would he be able to sleep through someone operating on him.

So I explained that the happy gas wouldn’t just put him asleep, it would put him really asleep, and that the doctor would make sure he stayed that way until everything was finished.

Afterward, once we were home and he was safely on the sofa with his ice cream, I asked him about it.

“I didn’t feel anything,” he said. “I can’t even remember anything.”

And then he said this—“I wish I could have some of that for when I go to school. That way I could just wake up when I got home and I wouldn’t remember any of it.”

Funny, yes. And that definitely pegged him as my son. But he really had a great idea there, at least on the surface. Wouldn’t it be great if we could have some advance warning to the less than perfect things we have to face? And wouldn’t it be great if just before we could put on a Batman mask, breathe some cotton-candy air, and fall asleep through the whole thing?

Yes. It would.

I’ll admit for a while I did my best not to try and poke holes in his Happy Gas Theory. I knew there were some and most likely many. But sometimes we take comfort in those things that aren’t and can never be. That’s what I did while sitting on the sofa with him. I reveled.

But the truth of course was that we had to go through our painful things sometimes. We could slide around some and jump over others, but sooner or later a storm would come that we couldn’t outrun or take cover from, and we were left to stand there in the open under the pour.

Sometimes, that didn’t seem right to me.

It would make more sense to say that if God was there and if God was good, He would take better care of the ones who loved Him. He would make sure our paths were clear. He would prevent the pain and the pour and the doubt. He would take away the fear.

If there was such a thing as everyday happy gas, I thought, then shouldn’t it be God?

Maybe. But maybe that pain and pour and doubt served a purpose that outweighed the need for our happiness. Maybe we needed fear so we could know the value of faith.

Maybe.

I didn’t know for sure, but I thought the odds were good that He’d spared me from a great many troubles in my life without me knowing it. Not happy gas, but maybe something better. And as I looked down and saw my son wince when he tried to swallow, I knew that all the happy gas in the world couldn’t take away all the pain. Some still lingered.

That was true for all of us, I supposed. We were all a collection of bruises and cuts. We all had our tender places.

And I thought that in the end, it was our pain and not our happiness that brought us nearer to heaven.

May 6, 2013

The walk

image courtesy of photobucket.com

“I like walking with you, Daddy,” my daughter said.

Her tiny hand slipped into mine and stayed there. Our joined arms moved back and forth in a soft cadence that echoed our footfalls.

“Me, too,” I said.

“Let’s play I Spy,” she offered.

“Okay. You go first.”

Our game began with the obvious—black for the truck in the driveway we were passing, red for the mailbox on the other side. Yellow for the sun. Gray for the dog that just bounded out from the field.

But then things began to get a little more difficult. On my part, anyway. I missed the orange on the robin that was pecking its dinner from the grass. And the brown on the rabbit that sat nearly invisible on the side of the road.

Missed the yellow hair bow on the little girl who was playing with a balloon in her backyard.

Missed the white on the rocks that scrunched under our feet.

Even missed the black on the very shirt I was wearing.

No father wants to be beaten in a game of I Spy by his daughter. Especially when that father happens to take a lot of pride in noticing things that others maybe wouldn’t. But as we walked and talked and swung our arms, I had to admit the obvious.

I was losing it. Slipping in my noticing.

It had been imperceptible rather than sudden, this change in me. That’s the worst kind. Change that comes sudden is painful, but at least you don’t go around wondering what happened and where you went wrong and how it got to be this way.

My thoughts were broken by the approach of a married couple taking that strange gait that is more than walk but not quite jog, puffing and sweating against the summer sun.

My daughter waved with her free hand, and I offered a “How ya’ll doin’?” in their direction. The man managed to nod weakly and gasp a “heeep,” which I took as hello. The woman was oblivious to us, transfixed on her goal of putting one foot in front of the other.

I looked down to see her gazing up to me, wrinkling her nose. I shrugged—beats me. We walked on.

A few more losing rounds of I Spy later, and we were greeted with another pedestrian. Younger woman, very fit. Decked out in Spandex and and armed with an iPod and a watch that looked as though it could not only count calories and measure distance, but split the atom as well.

She zoomed past our wave and “How are ya?” as if we were just more gravel and blades of grass. Just two more obstacles to avoid in the pursuit of a flatter stomach and firmer butt.

My daughter and I walked in silence a for a few steps, our game suspended. Then, “Daddy?”

“Hmm?”

“How come people walk so fast?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Most people around here use walking as exercising. But it’s only exercising if you go fast.”

She looked down to the road and kicked a pebble with her flip flop, thinking.

“Exercising’s good,” she offered.

“Very,” I said.

“And walking’s good, too.”

“Yep.”

“But,” she said, “walking shouldn’t be exercising.”

“It shouldn’t? Why?”

She threw her arms up (and one of mine in the process) and said, “Look! Everything’s so pretty! These people are missing it all because they’re going too fast!”

I looked down at her and she up to me. She said, “Those people would be really bad at I Spy, Dad. They would lose every time because they can’t see anything.”

They’d lose every time. Because they’re going too fast.

We continued on then and resumed our game. The result was both inevitable and expected. She won without much of a contest.

But in a way, I won too. I learned something that evening with my daughter. Something important.

In the end, life should be a walk and not a run. We fool ourselves into thinking that the point is to get somewhere as fast as we can. It isn’t. It’s to have somewhere to go and then enjoy the trip to it.

There will always be a gap between where we are and where we want to be. In our deepest hearts we are all wanderers in search of something. That’s okay. Even wonderful. Just as long as we wander in wonder and hold the hand of someone we love.