Billy Coffey's Blog, page 27

September 16, 2013

Real Men Don’t Text

Somewhere along the way, my daughter has turned into a pre-teen. I’m not sure exactly when it first started, but I’d peg it at some point in the last two weeks. When school started. Middle school, to be exact.

Somewhere along the way, my daughter has turned into a pre-teen. I’m not sure exactly when it first started, but I’d peg it at some point in the last two weeks. When school started. Middle school, to be exact.

In the back of my mind, I always knew it would happen this way—my quiet, funny, lively, ever-optimistic baby girl would leave for school one morning and come back home that afternoon sullen and attitudinal. Right now, all that’s missing is the Goth clothes and the black fingernail polish.

Last year, ask her how her days was and you’d be entertained for an hour. This year, ask her that same question and the response (if there is one) will be a shrug and a stern “Nothin’.”

Asking her what’s wrong yields the same answer.

Trying to figure out what’s going on inside the big brain encased in that little head is impossible. I’m not well equipped with such a task. I cannot understand my daughter. Which is only right considering I’ve spent the last twenty years or so trying and failing to understand her mother. It’s exhausting.

I’ve had help with all of this, of course. The aforementioned mother I’m still struggling to understand actually understands my daughter’s current state quite well. She remembers how it is, growing up. The memories of that murky place between little girl and young woman are still relatively fresh. “She’s just growing up,” is what my wife says. As if that is enough to make everything better. It doesn’t, not to me. To me, it just makes everything worse.

Because really, I don’t want my daughter to grow up. I like her just the way she is. Growing up means things I don’t even want to think about at the moment—things like the Family Planning class she’s getting ready to take (which I will not get into here other than to say DANG). It means things like smart phones. Things like boys.

The boy thing rests especially heavy on my heart. I was a boy once. I know what they think about and just how often they think about it. But I’m on the ball with that one, too. I recently got my copy of Ruthie and Michael Dean’s book Real Men Don’t Text. If you have a son or daughter (or niece and nephew, or etc.) between the ages of 11 and 30, that’s the book you want. My own copy’s going straight to my daughter in another couple of years.

In the meantime, I’m just trying to do what I can. Mostly, I’ve found that just means being there. Right there, right with her. Because it really is tough to grow up. At a certain age all of the shine you thought was on the world begins to fade and you find that what lies beneath isn’t always the bright and beautiful stuff you thought. You’re not supposed to save your kids from finding that out, you’re supposed to help them through it when you do.

September 13, 2013

The fear of letting go

The wails were coming from near the concession stand on the other end of the parking lot where I had noticed a church group was selling hot dogs and offering to wash cars. We all turned in the general direction and wondered what had caused the commotion.

The wails were coming from near the concession stand on the other end of the parking lot where I had noticed a church group was selling hot dogs and offering to wash cars. We all turned in the general direction and wondered what had caused the commotion.

None of us saw anything until my son pointed into the sky and said, “Look!”

We did, but there seemed to be nothing but blue sky and sunshine. But then I squinted and saw it. High above us, dancing with a hawk.

A balloon.

My daughter took the opportunity to offer her usual take of part philosophy and part practicality: “You gotta hang on to stuff,” she said. “If you don’t, it’ll just float away.”

Point taken.

My family finished shopping, winding into one store and out another, until we had each crossed our necessities off our respective lists. The end brought us to the concession stand. Hot dogs and a car wash were offered, but only the hot dogs were accepted. “I wash my own cars,” I told the nice lady. She didn’t understand. Guy thing.

“You two want a balloon?” I asked the kids. Which was a stupid question, really. What kid doesn’t want a balloon? I’m forty-one years old, and I wanted one.

They inched their way over to the huge tank of helium and gawked at what the church people offered. There were red balloons and blue balloons. White, black, pink, purple, yellow, orange. Big ones and little ones and all sizes between. I assumed they were trying to figure out which color and size to get. I was wrong. They were trying to decide if they really wanted one or not.

They chose not.

“Seriously?” I asked them. “You really don’t want a balloon.”

“No,” my daughter said.

My son’s mouth was full of hot dog, so he just shook his head.

“They have pink,” I said to my daughter, “And blue,” to my son.

No thanks.

“What’s the matter with you two?” I asked.

Their answer came not by their words, but from their looks. Up.

“You won’t lose your balloons,” I said. “We’re getting ready to leave. All you have to do is hang onto them long enough to get to the truck.”

No. From both.

“We have hot dogs,” my son said after he swallowed. “I don’t want to have to hold a balloon and a hot dog. I won’t be able to hold on tight. I’d let one of them go.”

“Me too,” my daughter said.

“I can help. I’ll hold the balloons for you.”

“But what if you let go?”

I told them I wouldn’t, but that didn’t seem to pacify them. They knew from experience that Daddy, while good in most things, sometimes dropped stuff. Normally this would not be a bad thing, since what’s dropped can just be picked up. But as we had all learned from the wailing earlier, balloons don’t fall when they’re dropped.

“So neither of you want a balloon?”

No.

“Because you’re afraid it’ll fly away?”

Yes.

“You gotta hang onto stuff,” my daughter said again. “If you don’t, it’ll just fly away.”

That was true, I thought, and not just with balloons. Lots of things would fly away if you let go of them. Good things. Things like dreams and friendships and love. You have to hang on to those. Keep your grip on them loose, and they’ll go away and leave you wailing.

But even worse than that is to never take hold of those things in the first place. To let the fear of What If overtake the pleasure of What Could Be.

I knew that from experience. There were plenty times in my life when I never tried because I was afraid I would fail. I didn’t want to see my balloon fly away. I would have rather been safe than hurt.

I knew better now. And I hoped my kids would someday know better, too.

Because the only thing worse than watching your balloon fly away is never having a balloon in the first place.

September 10, 2013

The Shine

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I am sitting on the hood of my truck atop Afton mountain on a warm August night, taking the opportunity to do something I once did often but now not nearly enough.Stargazing.

I was six when my parents bought me my first telescope, a twenty-dollar special from K Mart. It was made of cheap plastic and the lens wasn’t very powerful, but to me it was magic. I spent countless nights in the backyard squinting through that telescope, peering into lunar seas and gazing at Saturn’s rings. I was spellbound.

As I grew older, the stars began to serve another purpose. They were my refuge, a physical manifestation of an inner longing to break free from both earth and life and fly away. The night sky was my perspective. Looking around always made everything seem so enormous and consequential. Looking up always reminded me of how truly small everything was.

Now? I suppose now those two sentiments mingle, swirled together in my heart as a patina that washes me in both awe and longing. I gaze up to gaze within and know my truest self – that both darkness and light can blend to form a scene of beauty and wonder. That despite whatever misgivings I may have, I can shine.

I lean back against the windshield, place my hat on a raised knee, and stare. Above me is what a friend refers to as “a Charlie Brown sky.” Pinpricks of light are cast in a sort of perfect randomness, as if God has sneezed a miracle.

I am not alone here. There are about twenty other people scattered along this overlook, fellow viewers of nature’s television. An awed silence envelopes most. All but one little girl sitting with her father in the bed of the truck next to me.

“Daddy?” she says. “Do we shine?”

A thoughtful question deserving of a thoughtful response.

“I think so,” he answers.

“It’s good to shine,” she says.

“Most times. I guess it depends on where the shine comes from.”

My head turns from the stars to them.

“What do you mean?” she asks.

“Well, you see that star over there?” He points to a bright speck above us. “That star gives its own shine. It doesn’t depend on anything else but itself to give it light. It’s on its own.”

“That’s a bright one,” she whispers.

“Yep. But one day, all that light will be gone. That star will run out of shine. But you see that over there?” he asks, pointing this time to a big, round ball.

“That’s the moon,” says the daughter. “I know all about the moon.”

“That so? Tell me.”

“Well, Mrs. Walker says the moon is dark and cold and dead. And it isn’t made of cheese, like Tommy Franklin said.”

“You have a smart teacher,” her father answers.

“I don’t want to be cold and dark and dead like the moon. I’d rather be a star.”

“But the moon shines, too. And it’s a better shine.”

“How?”

“Because the shine isn’t the moon’s, it’s the sun’s. Light come from the sun, bounces off the moon, and lights the dark.”

“So moonlight is really sunlight?” she asks with a tone of both wonder and doubt. Mrs. Walker hasn’t gone over this yet.

“Yes. And because the moon is just reflecting the sun’s shine, it won’t get tired and start to fade.”

“So as long as the sun shines, the moon will, too?”

“You got it.”

The two sit in silence again, and my eyes move from them back to the sky.

A lot of us choose to stand in our own light. We want to be known for the things we do more than the people we are. “Look at me,” we say. “I’m special. Better.”

But we’re not. The more we try to shine our own light, the darker we’ll likely become. And sooner or later, we’ll fade. We don’t need to be stars in this life and be a light unto ourselves. It’s better to be a moon. Better to know that we can reflect the shine of someone greater and be a light to the world.

September 6, 2013

Packing Light

I always wanted to run away as a kid. Wait. That came out wrong. What I mean is that back then, all I ever wanted to do was leave home. No, that isn’t it either.

I always wanted to run away as a kid. Wait. That came out wrong. What I mean is that back then, all I ever wanted to do was leave home. No, that isn’t it either.

Let’s start over.

Growing up, there was a cornfield across from my house. On the other side of that was the railroad track that cuts through town. The train still comes through twice a day. More, if the freight is good. I remember standing on my front porch as those trains rolled through, staring at the open doors on all those empty container cars, wondering where that train was going. How long it would take to get there. How easy it would be to hop on.

I wanted to see the world. Chuck it all. Run away. I wanted to leave home and see the country.

Never happened, of course. But it did for Allison Vesterfelt. She left her home in Portland at age 26 with a friend, some bags, and a single plan—to visit all 50 states. The chronicle of her adventure (and that’s what it turned out to be) is found in her book, Packing Light.

Ally’s book caught me. She tells her story with a refreshing honesty, including just how frightening it can be to do something extraordinary. Imagine leaving everything behind—your job, your home, your family—and lighting out into the territory. Thrilling? Yes. Scary? Absolutely.

And yet Ally did it anyway, and on the other side found blessings that will comfort her for the rest of her life. That, really, is what this book is about—the lessons she learned along the way.

Things like embracing the unexpected. Changing your expectations. Losing your way. Choosing your path. Hers is a reminder that the great and mighty More a lot of us want in life really won’t bring us happiness. Most times, the peace we crave comes in having less.

“Knowing how valuable you are,” she writes, “and acknowledging your tiny role in a larger story is a difficult balance to strike. It’s easy to see one or the other, but it’s difficult to hang on to both at the same time. It stretches us, like a kid reaching for the next rung of a monkey bar, until eventually we find our arms stretched out wide.”

To me, that’s the best part of what Ally accomplished. Like all adventures, she went looking for the world and found herself.

Packing Light is a great read, and I highly recommend it. To learn more, visit the Packing Light page on Amazon.

September 2, 2013

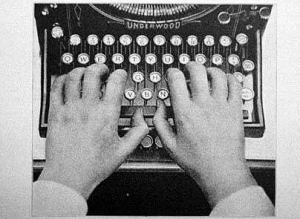

One thousand words

A thousand words sounds like a lot more than it really is. It’s just about two double-spaced pages or one single-spaced, depending upon the amount of dialogue or length of paragraphs.

A thousand words sounds like a lot more than it really is. It’s just about two double-spaced pages or one single-spaced, depending upon the amount of dialogue or length of paragraphs.

It’s also my daily writing quota. A thousand words a day, seven days a week. Doesn’t matter if that thousand words is a blog post or a chapter in a book or a magazine article. Doesn’t matter if it’s trash. Because it’s still writing, and that’s what matters.

It seems pretty absurd to state that a writer is a person who writes, but it’s a concept I can just as easily let go of as grasp. It doesn’t take much for me to read about writing and think I’m writing, or go to Staples and hang out with the notebooks and pens and call myself a writer. But it doesn’t work that way.

Because a writer writes.

So it’s a thousand words for me. Every day. Period. Because I need that discipline. That reminder. But like I said—that sounds like a lot more than it really is.

The thing is this:

There are days when those words gush forth from that mysterious place inside me like water from a fire hose. When I have long hours to sit and ponder and sink into my desk. When the sun falls through open windows and warms my room and heaven itself pours buckets of inspiration over my head.

Those days are rare. Exceedingly so.

More often than not those thousand words are stretched out from around six in the morning until one the next morning. Rather than gushing from me, they have to be cajoled and, in come cases, dragged into the light. Most come in those precious few minutes between one thing at work and another or between dinner and second grade homework. They come when I sink myself into my desk not out of comfort, but exhaustion. When the moon shines against draped and curtained windows and cools my room. When inspiration comes in slow drips like sap from a tree.

That’s the norm, whether you’re working on your fifth novel or your fifth blog post. Which is why your decision shouldn’t be I want to be a successful writer or I want to be published, it should be this and this alone:

I am going to write.

The decision to write isn’t like a New Years resolution. It’s a daily choice. A matter of the will rather than circumstance. Because trust me, once that choice is made the universe itself will align against you in an all-out attempt to keep you from doing just that. There will be appointments and chores and Things To Do. There will be children tugging at your sleeve and spouses tugging at your ear. There will be jobs and responsibilities, dusty tables and shelves, and a dishwasher that just has to be emptied.

You’ll be tempted to think, If I do those things and help those people, then I can sit and write.

Don’t fall for that. It doesn’t work. It doesn’t work because there will always be things to do and people to help.

If writing teaches you nothing else, it will teach you this: sometimes you have to be selfish. Your family won’t understand and neither will your friends, and that’s okay. It comes with the territory. At its core writing is a lonely task steeped in irony—in order to share yourself with the world, you must at times remove yourself from it.

August 29, 2013

Once is all you need

image courtesy of photobucket.com

A favorite saying of my mother: “You only go ’round this life once.”

Drilled into my head since I was a boy. It was a warning, though one I never truly heeded because it was only partially understood. “You only go ’round this life once” was sort of like my father’s “You can’t see the forest for the trees.” Catchy, but vague.

I turned 41 this summer, which is just enough past forty to get me worrying. Not that I fret too much about the grinding of the wheels of time. Forty doesn’t mean as much as it used to. In fact, I’ve read that forty is the new thirty. That’s supposed to make me feel better, I suppose. And it does. But still…

It’s fair to say that forty can be considered a good halfway point in most people’s lives. That’s about the point where a lot of us look back over our shoulders and realize there’s a whole lot behind us, then look ahead and swear we can see a speck of something on the horizon. And though death’s great sting isn’t as great as I once thought it to be, I still feel like there’s a lot left for me to do.

And lately I’ve come to realize the gravity of the fact I only go ’round this life once. Time, now, is the issue. Much more now than it’s ever been.

But it’s not just the time I have left to do things I’ve always wanted to do, it’s the time I have left to fix the things I’ve broken. I’ve broken a lot of things in my life. Done things I shouldn’t, said things I shouldn’t. I look back on a lot of my past not in reverie, but in regret. So much so that I now find myself at this magical midpoint thinking a do-over of my first forty years would be nice.

I think about all the time I’ve wasted. Not just wasted by watching television or daydreaming on the front porch, but wasted by worry and fear. Often I realize I have lived vast parcels of my life in reverse and upside down—the things that really should have bothered me never did, and the things that really bothered me were things that didn’t shouldn’t have bothered me at all.

I still act like this. A lot.

But now I’m beginning to realize I shouldn’t, that life is too short and too precious to be mindful of tiny irritations and bothersome fears. The first half of one’s life is viewed through the lens of ourselves—our needs, our wants, our desires. The second half is viewed through the lens of eternity. That’s when we begin to see that as big as this world can seem, it’s really the smallest thing we will ever experience.

I wish I could have figured all of this out earlier. Time and experience have a way of teaching us what we’ve always ignored, though. I spend a lot of my day with people who say if there was a God, He would do something about all of the pain in the world. I tell them I stumble over that sometimes too, but that I also understand if it weren’t for the pains in my own life, I wouldn’t know anything.

That part, at least, I’ve gotten right.

But there is much I haven’t.

It seems a bit pessimistic to be looking ahead at my coming years with the express purpose not to screw them up as badly as I managed the previous ones. That’s what I’m going to do, though. And I’m going to try and love more and worry less. I’m going to try to have faith instead of fear. And I’m going to make the attempt to smile as much in the pain as in the happiness.

Because my mother was right, you only go ’round this life once.

But if you do it right, once is all you’ll need.

August 26, 2013

Choosing love over anger

Antoinette Tuff went to her job at Ronald E. McNair Discovery Learning Academy last week thinking it was going to be just another day. That lasted until Michael Hill walked into the school carrying an AK-47 and 500 rounds of ammunition. Armed and telling her to call police and reporters so everyone could bear witness to the coming slaughter, he said he didn’t have any reason to live. Said no one loved him. One man with a weapon, nothing to lose, and a wish to die, standing in a school containing hundreds of children.

Antoinette Tuff went to her job at Ronald E. McNair Discovery Learning Academy last week thinking it was going to be just another day. That lasted until Michael Hill walked into the school carrying an AK-47 and 500 rounds of ammunition. Armed and telling her to call police and reporters so everyone could bear witness to the coming slaughter, he said he didn’t have any reason to live. Said no one loved him. One man with a weapon, nothing to lose, and a wish to die, standing in a school containing hundreds of children.

Yet another example of just how awful we’ve become. That’s what I thought at first. Close behind that was a firm desire to see Michael Hill strung up and every parents of every child in that school given a baseball bat and one free shot. It would have been Newtown all over again. Or Virginia Tech. Or Columbine. Or any number of that long string of school shootings that stretch back too far and contain too much senseless death.

But it didn’t happen that way. Antoinette Tuff was there.

She was the one who stopped Michael Hill, who distracted him long enough for the students to be evacuated. And who, as Hill exchanged gunfire with police, began to pray. For herself, of course. But also for the man who was going to kill her.

“I give it all to God,” she said after. “I’m not the hero. I was terrified.”

She convinced Hill to stand down and save his own life not by threatening him, but talking to him. Antoinette told the story of her own life to calm Hill down, sharing how her separation from her husband had left her feeling lonely and broken.

She told him not to surrender to despair.

Then she told him she loved him.

That’s right. Antoinette Tuff told this monster, this would-be mass murderer, that she loved him. And she said God loved him, too.

Michael Hill surrendered to police not long after. No one died that day.

I thought about Antoinette Hill all week. Thought about what almost happened and what had happened too many times before. I thought about what she said to Michael Hill when news broke of the Australian student shot by three young men who were simply bored and decided to kill someone. (Or because it was a gang initiation; reports vary, but does it really matter?)

I don’t know about you, but anger is my first reaction when I hear stories like that. Maybe it’s the redneck in me, or the father. Maybe it’s the decency coming through in the wrong way. I don’t know. All I know is it’s anger. Every time. It’s rage not only against the people who perpetrate such horrible acts, it’s a rage against the society that creates them and the God who lets this sort of thing happen. We’ve lost our way as a country. There’s a rot deep in our collective heart, and it’s spreading.

But I needed Antoinette Tuff to remind me that anger isn’t the way to fight that rot. Faith is. Love is. What will fix this country isn’t a fist, it’s an open hand.

“Our weapons are not carnal, they are spiritual.” So said Paul to the Corinthians.

Which means our fight isn’t against people. It’s against the heart.

August 22, 2013

Baring all

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Today marks the fourth day of my daughter’s junior high career. So far, it’s been a bumpy ride. She’s done everything she’s been taught, keeping that chest out and chin up and upper lip stiff. But I can see the cracks that have formed on that tough exterior. Even the strongest dam will break with enough pressure.

It’s been a long while since I was in the sixth grade. At a certain point, all those years beyond the last ten or so melt into one fuzzy memory of misshapen moments. Tough to tell the truths from the imaginings sometimes. My sixth grade year was like that until this week. Having my daughter endure it has allowed me to remember much, especially how scary it all was.

The news kids and new teachers. The new school. The extra homework. The hormones racing. Waking up in the middle of the night, trying to wipe your mind of the nightmare you just had about not being able to get your locker open or not finding a seat at the lunch table. Go ahead and chuckle. You know what I’m talking about. Chances are you’ve had those very dreams at some point and maybe even still do from time to time. To me, that proves just how important this time is in my daughter’s life, and just how much of it will cling to her in the coming years.

The biggest test of all came yesterday. She had been warned ahead of time—over the summer, in fact—but that didn’t make things easier. Seeing a thing coming from far off might lessen the surprise, but not necessarily the dread.

Not math or science or language arts. It was dressing out for P.E.

The thought horrified her. Standing in front of a chipped wooden bench in that smelly locker room, feeling your toes on the cold concrete. All that silence banging off cinderblocked walls. Taking your shirt off first because that’s bad but not nearly as bad as taking off your pants, only to discover after that your pants are all you have left. Trudging through the next forty minutes of laps and volleyball, knowing you’re going to have to do it all over again when that’s done.

Baring yourself right there, in front of everybody.

I remember that well, and how terrible it felt.

It’s not only a girl thing, either. The boys suffer, too. One teacher even told me the boys react worse. The girls cry. The boys throw up.

I never yarked my lunch, but things did reach the point when I started wearing my gym shorts under my jeans. It was uncomfortable and god-awful hot, but at least there was little chance of anyone seeing something they shouldn’t. Something only my doctor and mother should see, and only in extreme circumstances.

We don’t like baring ourselves. We’d rather be covered and clothed. We need that barrier between us and the world, even if it is just a thin layer of denim and cotton. If we don’t have that, there’s nowhere we can hide.

I tell her she’ll get used to it. I think that’s true, even if I never did. Of all the lessons my daughter will learn this year, I think the one she’s found in gym class is the most important. Not because I particularly want her just fine with prancing around wearing little more than what the good Lord gave her, but because there will come a time when she will have to bare other, even more private things.

Her heart, for one. Her fears. Her weaknesses and worries. Her faults and failings. We go to great lengths to cover those things, too, and with more than jeans and underwear. And sometimes, we hide behind those things better.

My daughter made it through yesterday well enough. It wasn’t bad, she said. No one looked at her because they were too busy staring at themselves. I think that’s true for a lot of things.

She still doesn’t see this as a learning experience, mostly because she’s stuck in the middle of it right now. That’s another lesson my daughter will learn soon. Unlike junior high, the tests we get in life often come first. The answers come later.

August 19, 2013

Saying goodbye to summer

I write this late on a Sunday evening, sitting at my upstairs desk as the frogs and crickets sing along the creek outside. The house is quiet, dark. Everyone else is in bed. It’s just me up here, watching the clock tick the last few hours of summer away.

I write this late on a Sunday evening, sitting at my upstairs desk as the frogs and crickets sing along the creek outside. The house is quiet, dark. Everyone else is in bed. It’s just me up here, watching the clock tick the last few hours of summer away.

Sure, there will be more warm days ahead. More late evenings when the sun still sets well after the supper dishes have been washed. Still plenty of time for a walk in the woods or a little fishing at the lake. But really, the end of summer has little to do with the weather and much to do with the calendar. Just ask my wife and kids. Because school starts tomorrow, and that marks the end of all that is right and good in the world.

It was the same for me when I was a kid. Still is, in many ways. My children are young, my wife is a teacher, and I work at a college. Our lives are inextricably linked to the school year. Enduring it to find summer on the other side feels like a rebirth. Facing the prospect of a new year? That feels more like a death.

Right now, we’re all dying a little.

A tad dramatic, I know. But it’s true in the sense that we are all about to give up a time of relative calm and quiet for nine months of stress and busyness. Despite our best attempts to inject a bit of excitement into the promise of a new school year, my wife and I have so far failed to inspire our children. Mostly because we aren’t very inspired ourselves.

That’s how it often goes, though, and for most of us. Life can be better measured in seasons than years. There are times when the sun shines and when it goes hidden, times when everything is green and beautiful and when the world lies gray and ugly.

We learn early on that nothing lasts. This life just isn’t built for permanence. Things fade and go away, both good and bad, and those things always come around again. We never suffer so much that we forget how to laugh, nor do we ever experience such joy that we no longer remember the salty taste of tears. That’s what I tell myself, and so I believe. My children aren’t quite there yet, and that’s fine because they will be one day. They’ll discover that often it’s the things you really don’t do that become the greatest things of all. There’s a blessing in pushing on and trying, in facing the inevitable. Even if what’s inevitable is something as small as the end of a summer vacation.

We’ll be okay. My wife. My kids. Myself. You, too. We’re all gonna make it through this little bit. We’ll all find ourselves laughing as we come out on the other side. It isn’t so bad, embracing the new and the unknown. There is great promise in it.

August 15, 2013

Angels unaware

image courtesy of nydailynews.com

I really wanted Patrick Dowling to be an angel.

Chances are good you’ve heard the story. Two Sundays ago, a young woman named Katie Lentz was driving to Jefferson City, Missouri, to attend church with friends. Near the town of Center, a car collided with hers, leaving Katie trapped in a ball of crumpled metal. Rescue teams arrived, but the equipment necessary to free Katie failed. Though she remained alert enough to talk of her church and her college studies, Katie’s vital signs began to fail. If she did not get to a hospital soon, she would die.

The emergency crews decided to push her vehicle upright—a dangerous and life-threatening course of action, but the only choice left. That’s when Katie asked if someone would pray with her, and that’s when a man dressed as a priest stepped forward and said, “I will.”

No one knew how the priest had gotten there. The road was blocked off for two miles in either direction. None of the rescue personnel, many of whom lived in nearby communities, recognized him. And yet the priest approached Katie’s car and began praying with her, telling them all only to relax, that help was coming. Twenty emergency workers helped to sit the car upright. Katie’s vital signs rebounded. Another rescue team arrived, carrying fresh equipment. Katie was freed and rushed to the hospital.

When the emergency personnel turned to thank the priest, they found he had vanished. No trace of his presence remained. Adding to the mystery was that of the nearly seventy photographs taken at the scene, not one of them showed the priest. Thus was born the legend of the Missouri angel.

I love stories like that. Crave them, in fact. They are a reminder that we are never truly alone. We are watched over. Protected, even in the midst of such pain and danger. By the time I read of Katie’s ordeal, her story had been picked up by news media worldwide. Everyone wanted to find the mystery priest. I only shook my head and smiled. They’d never find him, because that hadn’t been a priest at all.

Then Patrick Dowling stepped forward. Father Patrick Dowling, I should say.

He had been returning home from delivering Mass in Ewing, Missouri, when he’d arrived at the scene. He parked 150 yards away and made his way forward, believing there was something he could perhaps do. The Sheriff granted him permission to approach the scene of the accident. That’s when he heard Katie ask if there was someone who could pray with her. After, when she was extracted and taken to an awaiting helicopter, Father Dowling hadn’t disappeared at all. He’d just walked back to his car.

There hadn’t been an angel along that stretch of highway near Center, Missouri, at all. There had just been a man.

I’ll be honest—a part of me didn’t want Father Dowling to come forward. I’d rather he’d remained anonymous. Let people think it was an angel. Let them believe. These are dark times, after all. We need that reminder of a watchful God and loving Father, Someone eager to send help.

I’ve since changed my mind, though. As much as a part of me still wishes it had been a genuine member of the heavenly host with Katie Lentz that day, I’m fine with it being a simple priest. Glad, even. Because these are dark times, after all, and we all need a reminder that we’re not alone. We all crave that kind touch of grace and mercy from God’s hand. We all need to know He’s eager to send help.

We all want to know there are angels near.

And I believe God sends them. Every single day, and to everyone. Sometimes those angels come as mystery and light. Other times, they come as people like you and me.