Billy Coffey's Blog, page 23

February 10, 2014

ANSWERS

To a certain extent, ritual plays a part in every life. We all adhere to our own ceremonies to mark the important occasions that come along. It can be something as extravagant as a neighbor of mine plans every Thanksgiving, when his home becomes a meeting place for family scattered to all corners of the country. Or it can be as small as the shot of whiskey a friend of mine takes at 4:12 in the afternoon each July 27, in remembrance of his father’s passing.

To a certain extent, ritual plays a part in every life. We all adhere to our own ceremonies to mark the important occasions that come along. It can be something as extravagant as a neighbor of mine plans every Thanksgiving, when his home becomes a meeting place for family scattered to all corners of the country. Or it can be as small as the shot of whiskey a friend of mine takes at 4:12 in the afternoon each July 27, in remembrance of his father’s passing.

My own ritual—smaller than either of those I mentioned, yet to me no less significant—revolves around cleaning out my desk before the start of every novel. It is no mammoth undertaking, usually requiring no more than an hour’s time and involving no more than shelving books and filing papers. But I like to start fresh with each story I write, and nothing says fresh more than an empty slab of oak upon which to write.

As I cleaned and filed and shelved this morning, I came upon a tattered manila envelope at the bottom of a stack of papers. ANSWERS had been written diagonally across the front in red permanent ink, in a hand I can scarcely recognize now. The inside bulged with notes and scraps; newspaper clippings; magazine articles; letters written to me and copies of letters I’d written to others. Some were dated as recent as last year. The oldest had 4 Oct. 89 scrawled along the top.

I spread them out before me, reading each one until I remembered, trying to place the where and why of myself—what it had been that led me to include those stories there, in my envelope. I am not to the point that I can say I have lived many years upon this earth, have accumulated many things along the way, and yet I have always counted that envelope among my most important possessions. Because, what you see, what rests in there are all the questions I wish to ask God when I am able to see Him face to face. They are the things I wish to know.

I will stop short of calling that envelope EVIDENCE FOR PROSECUTION, though I admit it was very nearly labeled that instead of ANSWERS. And whom was I determined to prosecute, way back in the very dawn of my adulthood? God, of course. And for the single reason that I did not approve of the way He did things.

Laugh at that all you will. Take a look inside my envelope, though. You may change your mind.

You’ll see an obituary for a high school classmate of mine, who was killed in a freak accident not two years after our graduation—a bright, funny, loving boy, full of life until he wasn’t.

You’ll find a story of a missionary tortured and killed.

A small girl who wandered from home and became lost in the woods, never to be found.

A single mother of three, dying of inoperable cancer.

Accounts of oppression, disease, and injustice. Diary entries of heartbreak and doubt. Themes of death and evil. Tales that over the years forced me to wonder what you or anyone else have wondered at one time or another—

How can a good and loving God allow such things?

At a certain point, I understood there would be no answers to that question on this side of life. People have been questioning the origins of evil and it’s place with God for thousands of years, and we are not too far down the road to answering it. So I’ve kept all my questions here, in this envelope.

How exactly I would get that file to heaven with me was something I never quite figured out. In the past few years, I’ve devoted less and less time to pondering that problem. Not because evil no longer bothers me—it does, perhaps more now than ever—but because of the very likely possibility that I won’t care much about my questions in heaven. I’ll be too full of joy. I’ll be too busy spending time with all those who passed on before me, and preparing for those yet to arrive.

I still don’t understand a great many things in life. I suppose I always won’t. I don’t know why there must be cancer, and why that cancer must take so many innocent people. I don’t know why there is evil, or why there seems to be so much more of it than good.

I don’t know why God does the things He does, or allows what He allows.

But I can do one thing. I can approach those questions now as though they were parts of a story, one I would write just as God writes His own upon all of creation. And I would say—not as a pastor or theologian or philosopher, but as a storyteller—that it is far more beautiful a thing to be redeemed than be innocent. It is far more amazing for fight for peace in a fallen world than to maintain peace in a perfect one.

And it is far more noble to spend your life in search of something than have nothing to search for at all.

February 6, 2014

Can’t wait to die

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

Dear Ms. Elementary School Counselor,

Chances are fair that I really don’t need to do this, not with the great number of other tasks that need to be crossed off what I’m sure is a long list. Still, a part of me expects your call at any moment.

I imagine your voice would be kind but grave, telling me in the most professional way possible that my son is afflicted with suicidal thoughts. You will probably suggest several courses of action, all of which should be immediate and most of which will involve varying arrays of medications and counseling. If that call should indeed come, I intend to put you at ease and email you this short note as an explanation, hoping you are of a mind to understand. Because, yes, my son did announce to the half-dozen or so of his classmates at the lunch table that he couldn’t wait to die, but that’s not what he meant. At least, not really.

Like most things, context is what’s important. That’s what I’ll give you. And if by some chance you haven’t received the full account of what my son and his friends were discussing, he said they were all ruminating on death. I’m not so intelligent, nor am I a licensed school counselor, but I would imagine such a topic wouldn’t raise too many red flags. It’s been my experience that children do not shrink from the thought of dying, that they see it as something what will always come sooner rather than later. It’s only when we grow up that death becomes a menace, something that should be ignored lest it be considered.

I say all that so I can say this—my son was merely stating a fact. He has told me often that he cannot wait to die, and I must confess the idea is not wholly his own. I was the one responsible for planting that thought in his head. I can’t wait to die, either. Nor my wife, nor my daughter. Nor, in fact, most of our friends and acquaintances. Before you panic and think you’ve just stumbled upon some hillbilly suicide pact, let me assure you that’s not the case. We—my son and his family—simply believe there isn’t death at all. There’s only life followed by more life.

I realize this may come as no surprise to you, and that you in fact may share this conviction. In a town in which there are nearly four times as many churches as stop lights, the odds are good that’s the case. And yet I am realistic enough to know the changing times—even here, many of the pews in many of those churches are emptying, life has grown too busy for the Sabbath, etc. If that’s true in your case, I’ll do my best to explain in greater detail.

You see, we believe there is more. More to life, more to the universe, more to everything. That all we know is but a sliver of what is actually true and real, and that hidden behind all we can perceive is a single thread that traces its beginning to a God beyond all understanding. That holy, loving God imbued us with more than a mind to ponder and a heart to feel. He gave us a soul as well, and he placed inside us all a spark of eternity that not even death can destroy.

I know—that might not make much sense. It sounds a bit irrational. Even childish. That’s fine. Much of what we believe seems as such to those who don’t. We’re used to being misunderstood and even mocked, but this is who we are, and this is what we will forever be.

I’ll only say this: yes, we are looking forward to that greater life beyond. We see that world as much brighter and more real than this tired and frail one we live in now. But that’s not to say we are eager to leave. We have much to do here, much more to grow. We have a purpose and meaning. So I ask that you not worry about my son. He’s in good hands. Worry instead for those who believe this life is the end, and only darkness waits hereafter.

With kind regards,

February 3, 2014

Helpless, but not powerless

There are degrees of heartache in life, each plotted on some imagined graph with “stubbed toe” on one end and “paper cut” farther up, up on through “loss” and “failure” and whatever else, but at the very top will be found a jagged black border surrounding bright red letters that read “sick child.”

There are degrees of heartache in life, each plotted on some imagined graph with “stubbed toe” on one end and “paper cut” farther up, up on through “loss” and “failure” and whatever else, but at the very top will be found a jagged black border surrounding bright red letters that read “sick child.”

I know this because I’m at the doctor’s office with two of them. What exactly is wrong with my children is beyond me, which is why we’ve taken the lengths to drive to the other side of town on such a hard winter’s day. The flu, perhaps—one of those strains not covered by this year’s shot. That, or two bad colds. I suggest the likely culprit is remorse for the cold and snow that has cancelled school these past few days. My son nudges me in the shoulder for that little remark. He tries to laugh. It comes out more a phlegmy snort and I think No, not a flu. Bronchitis, maybe. The doctor will know for sure.

My wife is on my opposite shoulder. Beside her is my daughter. She sniffles, and that small act brings a bit of rosy color to an otherwise pale face. Her coat is zipped to her chin, her blue scarf cinched tight, her legs tucked under her, yet she still shivers against the fever. It’s been two day now. My son’s discomfort is largely auditory—sharp sneezes and deep coughs, each punctuated by sudden and sometimes frantic sprints to the bathroom. My daughter’s condition is more silent and worrying. A diabetic since the age of four, maintaining her sugar is a constant walk upon a tightrope easily swayed and poorly moored. Any virus can ravage her. While you and I have a glucose level that holds steady anywhere from 80-110, hers just clocked in at 396.

And so we sit. And so we wait, huddled together in a tiny corner of this doctor’s office.

Our view is of a bleak outside and the bleaker faces that come in from it. It is a sad parade of the weak and the dying, and I think to myself that however stricken these poor souls are, it is at least themselves who are sick and not their children.

Hung in the middle of the far wall is a framed reprint of Sir Luke Fildes’ The Doctor, first painted in 1887. I’ve sat in this cracked vinyl chair and stared at that painting many times over the years through many discomforts, studying the central figure of the Victorian doctor gazing intently at his patient—a little girl lying sick on a makeshift bed of mismatched dining room chairs, two large pillows, and a ragged blanket.

It’s not the doctor I focus upon this time, but the two figures in the background—father and mother watching from a distance, he with a look of anxious worry and she with her head on the table in despair. Both regulated to the shadows, helpless to do anything.

That’s how I feel right now.

Even a bad parent would not want his or her child to suffer, to writhe and wince with cough and fever. Even a bad parent would wish to suffer in that child’s place. And yet life teaches us all that very often the power we believe we possess is a lie, nothing else. Ours is an immense world, and we are such small things. The virus coursing through the two children beside me is mean and debilitating, and so is the defenselessness felt by their parents. We’ve done all we can. It wasn’t good enough.

Yet in the small minutes I’ve sat here, I’ve learned this one important thing—we are often helpless in this life, but we are never powerless. What we cannot mend we can ease, and where we cannot cure we can comfort. I can’t make my son better, but I can offer him a shoulder upon which to lay his head and a joke to make him smile. I can’t chase my daughter’s fever, but I can put my arm around her and kiss the top of her head. I can listen as she tells me of the book she’s reading.

I cannot spare my children from the troubles of this life, but I can love them through those troubles.

Maybe in the end, that’s what matters.

January 30, 2014

Writing stuff that matters

She walked up to me at the end of church last Sunday, one wrinkled hand stretched out in search of my own. Her woolen coat was already cinched and her hat pulled down tight, leaving only a wisp of white curls jutting out the sides. She smiled, and I noticed her teeth were too straight and too white to be her own.

She walked up to me at the end of church last Sunday, one wrinkled hand stretched out in search of my own. Her woolen coat was already cinched and her hat pulled down tight, leaving only a wisp of white curls jutting out the sides. She smiled, and I noticed her teeth were too straight and too white to be her own.

“I’ve just read your latest novel,” she said, and then she patted my hand.

I grinned. “Really? Well, thank you, ma’am.”

“Don’t thank me.” Still smiling. “I didn’t like it at all.”

She kept her hand in mine and squeezed, wanting to reassure me that all was still right in the world.

“I see.” It was all I could think to say. “I’ll have to try better next time.”

“I read your first book. Snow Day. That was wonderful.”

“Thank you.”

“Such a nice story. Almost like a Hallmark movie. Have you ever thought of doing a Hallmark movie?”

“I don’t think that’s up to me,” I said.

“But this last one…” She made a face. It was all sadness and misery. But it hid her teeth, and for that I was grateful. “I just don’t know what’s happened. This last book? Awful. Too much heartache. And the characters? The bad ones were good and the good ones bad, and I never knew who was right and who was wrong. And the deaths. Awful, awful stuff. How could you write something like that?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Just kind of came to me, I guess.”

“You were always such a good boy. I’ll pray for you.”

“Can always use that, ma’am.”

“Good. Now you go write something like Snow Day. What a lovely book. There was no blood.”

She walked on, tackling the last button on her coat as she did, then tucking her Bible under her arm as she shook the preacher’s hand and then walked into the cold outside. I stood there alone and grabbed my own Bible, trying to find my family and my thoughts.

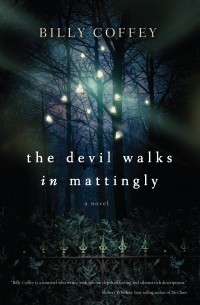

She was right, you know. There was no blood in my first novel. There was some in my second. A bit more in my third. I suppose I could have told her my next book will be out in March and is called The Devil Walks in Mattingly, but I think that would have only decreased her respect and increased her prayers. I wondered if that kind old lady would read that book. I hoped so and kind of didn’t.

When my first novel came out in 2010, I felt as though I had reached a distinct midpoint in my life. The same world that so often had played out in front of me full of disappointment and despair brightened in the sharp light of hope. I had crawled through the valley. Climbed the mountain.

I felt born again, again.

That feeling hasn’t lessened. Every novel I write is to me a miracle, evidence that God isn’t quite done with me yet. It still sometimes feels like I’m crawling through a valley and climbing a mountain. The only difference is that at the top of that mountain there is always another, higher one, and another, deeper valley. But that’s life for all of us. Those joys we feel, the days of contentment and peace? Those things are merely the peaks upon which we stand and rest before continuing on our long journey to a land we cannot see but can only feel.

After standing on so many of those peaks, I suppose a part of me changed. My writing certainly did. I am a product of my environment, of a small town and blue mountains and dark hollers and folktales of ghosts and angels, brimstone and grace. Between you and me? I sort of ran from that at first. I wanted books that were easy and inspiring. No pain. No hurt. No loss.

Not anymore, though. And ironically enough, it was church that convinced me otherwise. It was my faith. It was that kind old woman’s faith. It was faith in a book we believe is the very Word of God, a book of stories about a serpent bringing ruin; a baby left to float down the Nile in a basket; a lowly shepherd boy facing a giant. A book about a righteous man suffering much for no reason and a prophet being swallowed alive by a whale. Of cities destroyed and countries enslaved. A savior hung to die on a cross. Heartache and blood.

Not easy stuff to read. But real stuff. Stuff that matters a great deal.

Next time, I’ll tell her that.

January 27, 2014

The state of our Union

The State of the Union speech is tomorrow, at which several thousand media-types and politicians will take their accustomed places and either praise or condemn, and the other 200 million of us will offer a collective, exasperated sigh that things really have gotten this bad.

The State of the Union speech is tomorrow, at which several thousand media-types and politicians will take their accustomed places and either praise or condemn, and the other 200 million of us will offer a collective, exasperated sigh that things really have gotten this bad.

But I’ll still watch it, just as I’ve watched every State of the Union since I was ten. I’ll take my spot on the sofa and soak in every word and round of applause, every bit of analysis and rebuttal. Watching has become a tradition of mine, though politics has nothing at all to do with it. Martin Leonard Skutnik III does.

Lenny to his friends. If you’re forty and over, chances are pretty good you remember him. His face and story are likely stuck inside a dusty drawer in the back of your mind, one labeled BIG THINGS. Lenny was a big thing. Thirty-two years ago, he was maybe the biggest. And rightly so.

He was on his way to work on January 13, 1982. Just a regular guy trying to weave his regular car through regular traffic to get to his regular job. That changed when the jet fell out of the sky. Air Florida Flight 90 had taken off earlier from Washington National Airport, bound for Tampa. As Lenny neared work, the Boeing 737 struck the 14th Street Bridge and plunged into the Potomac.

Lenny was only one of hundreds of people who watched as emergency personnel worked to save the victims, one of whom was a passenger named Priscilla Tirado. Frightened and cold and exhausted, Priscilla was too weak to grab hold of a line lowered by a rescue helicopter. She flailed and began to fade. Lenny and the great throng of others watched in horror. But as the rest of them looked on helplessly, Lenny Skutnik decided to do something.

He took off his coat and boots and jumped into the icy water, swimming the thirty feet or so to where Priscilla Tirado struggled in nothing but pants and short sleeves. Lenny got her to shore. Saved her life.

Two weeks later, Ronald Reagan delivered his State of the Union. I watched it only because my parents made me. Partway into his speech, Reagan mentioned an ordinary man named Lenny, sitting in the gallery next to the First Lady.

Lenny Skutnik stood. The chamber roared.

Everyone. Citizens and media alike. Democrats and Republicans. Liberals and conservatives. All of them united for one small moment, for one small man.

That’s why I watch the State of the Union each year. Because it kindles the memory of that ordinary man who did an extraordinary thing.

And you know what? I need that reminder. We all do. The dark side of man is on display for us to see at every moment. It stares at us with each news segment from Syria or Iraq. It dares us with every profile of a political prisoner or story of the hungry and cold and oppressed. It’s as close as a click on a link or a turn of the channel. Every day, everywhere, there is proof that we are less than we should be.

It’s easy to see the bad in us, and how we’ve made such a mess of the world. That’s why people like Lenny Skutnik are so important. Not simply because of the great things they do, but because of the great thing they prove: That there is evil in us, but there is goodness in us as well.

Immeasurable, unfathomable glory. Bravery and love and heroism.

Greatness.

January 23, 2014

Ambitious goals

photo by photobucket

Spencer said, “I ain’t never doin’ it. Cross my heart and hope to die.”

The words were slurred because his tongue was still hanging out of his mouth, giving the impression that this five-year-old had been drinking a little more than his customary Kool-Aid.

“Do you have to keep sticking your tongue out like that?” I asked him.

“Yeth,” he slurred again. “If it’s in my mouff, I can’t control it.”

“Ah,” I answered and nodded in approval. It was a good idea, I thought. A more practical way to tame the tongue. “Good luck with that. If it works, you’ll be famous.”

“Why?” he asked, eyes bulging.

I shrugged. “It’s never been done before. Not as far as I know. Folks say it’s impossible.”

Spencer hadn’t considered the prospect of fame. Riches, yes. But renown might be even better.

“I ain’t never doin’ it,” he repeated. Meaning that was that and I should probably be moving along.

So I did. Away from the Sunday school rooms and through the foyer to grab this week’s church bulletin, then finally into the sanctuary to settle my family. It just so happened that Spencer and his family settled in two rows behind. Just after the first hymn and just before the first prayer, I stole a look over my shoulder.

Spencer’s tongue was still out, despite the repeated attempts by his mother to rectify what she no doubt considered ill manners. I raised an eyebrow at him and got a thumbs up in reply.

His father takes the blame for the entire situation. He was the one who took care of Spencer’s loose bicuspid with a bit of fishing line and a doorknob. “Quick and painless,” he’d told his son. Spencer didn’t think that was quite so. Turned out that both of them were right.

The trick was quick, yes. And also painful.

Fathers often resort to desperate measures to put a stop to a crying child, and Spencer’s tried everything in the book up to and including an impending visit from the Tooth Fairy. That perked Spencer’s ears a bit and brought the wailing down to a somewhat manageable sob, but that only lasted until Spencer found out all the Tooth Fairy was good for was a dollar. To him the pain and suffering alone was worth at least ten, not to mention the mental distress.

Knowing his son was quite the budding capitalist, Spencer’s dad decided to up the ante with an old wives tale.

“Better stop cryin’,” he told his son, “or else your tongue might slip into that hole in your mouth.”

Spencer stopped. “Why?” he mumbled.

“You mean you don’t know what happens if you keep your tongue clear?”

“…no.”

“If you never let your tongue touch that spot, the tooth that comes in will be gold.”

It was without doubt a stroke of genius, a psychological ploy designed to divert Spencer’s attention away from the pain he was feeling. More than that, he gave his son a goal. And we all know that a little pain is nothing if there’s a goal to be reached.

However.

There is that unscientific yet utterly concrete law of unintended consequences. Each cause has more than one effect, which will lead to any number of side-effects. In this particular case, the effect was what Spencer’s dad intended—his son stopped crying. The side-effect, though, was that Spencer walked around the house for a full day and a half with his tongue hanging out.

His parents didn’t mind (though his mother would have preferred her son not stick his tongue out while in the house of the Lord). In fact they encouraged it, going to far as to tell Spencer that it was considered permissible to house his tongue inside his mouth during sleep. Evidently consciousness is a prerequisite in the cultivation of a gold tooth.

In the end his parents have experience on their side. They understand the desire to accomplish a goal, no matter how intimidating the odds. They also understand that very often the thing we’re trying so hard not to do is the very thing we end up doing. Life is all about the constant battle between the two.

The pastor delivered a fine sermon that Sunday, but I have a feeling no one will remember it. What they will remember is the sound of a little boy shouting “Aww heck!” in the middle of the service. The Bible does indeed our desires are tough to tame. We’re always getting in our own way. Which is why the real sermon that day came from a child in a pew rather than a preacher at the podium.

January 20, 2014

How bad do you want it?

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

It’s amazing how many conversations I have with people that end up with them saying, “Well, I’m working on a book, too.”

I met one such person at the local bookstore last week. Nice fella. Rooting around the reference section and about to pick up a copy of On Writing, by Stephen King. We got to talking. Sure enough, he’s a writer. Has two manuscripts sitting in the top drawer of his desk back home. Funky stories, full of zombies and whatnot. They’re good, he promised. I didn’t doubt they were. He has dreams of agents and publishers and auctions and signings, all of which will happen as soon as he sends those manuscripts off. That’s the problem. He can’t seem to get either of them out of the drawer.

I nodded. He explained that deep down, he’s afraid an agent or editor just won’t understand the depths of his writing. I nodded again. Happens all the time, he said, and then he held up the book in his hand and asked if I knew how many times King had been rejected before he made it big, or Grisham, or Rowling. I said I didn’t but guessed it was a lot. He nodded gravely and whispered, “Oh yeah. A LOT. I can’t handle that, dude.”

He bought the book. Saw him in line a little while later, thumbing through the first few pages and nodding as he soaked up Mr. King’s words.

I couldn’t really think bad of him. I was that man once. I think we all are in a way. Doesn’t matter who we are or how old we happen to be, we all have dreams. We might not act upon them, but they’re there. We have all at some point sat in the middle of our lives, looked around, and said, “There’s gotta be more than this.” That’s my theory—none of us really want a lot, we just want a little more than what we have.

But the thing is this: often, that little more we want requires a lot. A lot of risk, a lot of work, a lot of sacrifice. In the end, that’s what separates the ones who manage to reach their goals from the ones who don’t. Sure, talent plays a part. But talent can only get you so far. My friend in the bookstore may be the next Tolstoy, but none of us will ever know. Writing is easy. It’s sending it out into the world that’s hard. It’s wanting it bad enough. And when I come across people like that, I think of Wayne.

I met Wayne years ago at the boxing gym. Huge guy, hands as fast as lightning. While the rest of us were there to get in shape and occasionally get the snot beaten out of us, Wayne had higher aspirations. He wanted to turn pro. And he wanted it bad.

Trained every day. Fought as often as he could. He racked up wins and knockouts, took on ranked opponents, climbed the ladder. His dedication was inspiring. Having him there made me work harder and sweat more. There was no doubt in my mind he’d make it.

Wayne worked construction during the day, said it kept him in shape. He was two months away from the biggest fight of his amateur career when an accident mangled the ring finger of his right hand. The doctor said he’d need surgery, followed by a few weeks of rest. And absolutely, positively no training.

The fight would have to be cancelled. No telling how long it would be to reschedule. Wayne’s dream of turning pro hung in the balance. So he did what he had to do.

He cut his finger off.

Nope, not kidding. Did it himself in his garage one evening. Trained left-handed for the next week, had his fight. He won.

That’s what it takes to succeed. It’s the only way. Doesn’t matter if it’s writing or boxing or college or a new career. You have to want it, and then you have to go get it with a mindset that says you’ll get up every time you’re knocked down. You won’t surrender. Ever forward, never back.

Even if it means losing pieces of yourself along the way.

January 15, 2014

Difficult losses

image courtesy of gamescrafters.berkeley.edu

We Coffeys are a competitive bunch. Life most character traits, that particular one has both its plusses and minuses. But by and large, our competitiveness has served us well. We are not content to be merely good at something. We have to be the best. And of course, in order to be the best, you first have to beat the best.

Which I suppose is why my son kept challenging me to games of Connect Four. You know the game, right? Big yellow rectangle on a pair of blue plastic stilts. One person has black checkers, the other red, and the winner is the first to get four of his or her colors in a row. It was under the tree at Christmas. Mostly because I played it all the time when I was a kid.

My son took to the game just as I did in my once-upon-a-time. We played a game under the tree on Christmas night, then again the night after, and then every night since. Until tonight, anyway. But I’ll get to that.

The thing about playing games with your kids is that you wonder when and if you should let them win. I’ve let my kids beat me at wrestling and boxing and Scrabble and chess. Not often, mind you, but often enough. It’s important they learn graciousness. Both when they win and when they lose. But I never let my son beat me at Connect Four. Some things needs to be a challenge. And to be honest, I like my kids to think I’m a genius at something for now. I know it won’t always be like that.

So we played. He tried, I toyed. He lost, I won.

Until last night.

My son beat me. Snuck in a backdoor diagonal of four red checkers. I never saw it. And what’s worse—what’s maybe worst of all—is that by that point I really was trying to beat him. He had homework to do, and so did I. I’d used my last move to set up my third black piece in a row, hidden from his sight on the opposite side of the board. It was a brilliant move. His was more so.

He dropped in his fourth checker and bulged his eyes.

I bulged mine.

“I win!” he shouted. Then he jumped up and crawled around to my side of the board just to make sure. “I win!”

There had to be some mistake. He’d miscounted. There were three checkers, not four. Or four, but not in a row. Something. Anything.

But. No.

“You win,” I whispered.

He danced. He screamed. He told his mother and sister. He even took a picture of it.

I was happy for him. And not. Like I said, I’m competitive. I don’t like to lose, especially when I’m trying to win and ESPECIALLY when I’m trying to impress my son with my staggering strategic intellect. That’s bad, I guess. But honest. At least I was a gracious loser. I allowed him his celebration. All three hours of it.

He was still awake when I went to bed, though barely. The excitement had worn off by then, leaving behind a sheen of quiet reflection on his face. I tucked his blankets and kissed him on the forehead, then headed for the hallway.

“Dad?” he asked.

“Yeah, bud?”

“I’m sorry I beat you.”

I smiled and told him not to be, that he’d won fair and square and should be proud because I was proud. The next morning, he said he hadn’t slept well. Neither did I.

I waited tonight for him to suggest another game. He didn’t. The box still sits untouched in the basket behind the recliner. I supposed it will be untouched for a while.

I suppose every child must inevitably arrive at that moment when he realizes his father is not the perfect man he’s always believed. That he in fact makes mistakes and misses things. That he loses. That he is a fallible, fallen person. It is a difficult moment, but a necessary one.

Both for the parent and the child.

January 14, 2014

The heartbeat of this world

image courtesy of photobucket.com

My uncle has passed. The cancer took him.He left the world at five o’clock this morning. Saturday morning, it is. January 11. As I write this I glance up to a cold rain falling through the fog that rolls down from the mountains. It seems right that death should be greeted by such weather. We know where he is, and we know that place is fine and beautiful and has no cancer in it, but that does not mean there is no grief. There is grief for my family. And there is heartache for my aunt and two cousins.

He was a simple man who lived a simple life. A farmer who spent much of his time tending to land that has been his kin’s for generations. A devout man, a hard worker, a provider for his family. When you are from my part of the country, such qualities lead people to call you Good. He was a Good man.

The cancer had been in his family, felling several. I suppose the thought that he could meet a similar end was in my uncle’s mind. He abhorred doctors. He chose to ignore the pain that began months ago rather than have it investigated. He knew, I think. I think in some way he always knew. By the time there was no choice but to seek help, it was too late. The cancer was everywhere by then.

To the end, he rose each morning to feed the animals with a strength none of us can fully fathom. The land was his life, all he knew. Several days ago, as the cancer spread into his brain, he wandered outside without a shirt in below-zero temperatures. My aunt and cousins let him, too wearied by their long fight against the death that stalked him. He stared out over the hills and fields and came inside when he finally grew too cold. So far as I know, it was the last time he gazed upon his tiny part of the world.

The pain was too great for him last night. No amount of medicine could ease it. Death saved him from more life. That’s how I’m trying to see it.

Upon his death, my cousins washed his body and dressed him in a suit. The simple cherry box he will lie in was handmade by a local Amish man. He will go into the ground today in a family plot that overlooks his home, watched over by a preacher, my aunt, and her children and grandchildren. It is the way my uncle wanted it, and how the country and mountain folk have buried their loved ones for hundreds of years. You may think that strange, backward almost and excruciatingly difficult. That’s fine.

We do not choose how we are born into this world and we do not choose how we leave it. It’s the wide spaces in between that are ours to live and do—to craft something of worth, something that will last, something that will honor the God who blesses us all.

My uncle did that in his own quiet way, and that is why I write of him now. Because on this and every day, there are many more like him in the hills and hollows of our country. They grow the food you eat and the cows that give you milk and beef. They live by the whims of weather and the grace of God. They are the heartbeat of this world, and they should be remembered.

January 8, 2014

Blissfully disconnected

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

There is nothing but night and fire on this early morning. All else is gone. Word has it that a substation twenty miles away has blown. Crews are still trying to figure things out. At last count, nearly twenty thousand people are without power. A minor inconvenience, really, were it not that this is one of the coldest days of the year.

But there is a fire in the fireplace to warm the house and a dog on my lap to keep me company. As luck would have it, I managed to brew a pot of coffee just before everything went kaput. Here I sit under a blanket, watching the orange flames dance off a wall that in thirty minutes will catch the first rays of sun over the mountains. All is quiet and sleeping. And I have just realized that in this moment, I am as peaceful as I have been in a very long while.

Funny how that happens, isn’t it? Sitting here on this dark January morning with all of modernity’s trappings stripped away. Back to the nuts and bolts of living. It’s worth nothing that human civilization thrived for thousands of years with little more creature comforts than I am enjoying right now. I feel a strange kinship that reaches far back from where and when I sit. I wonder how many men how many times before have greeted their day with nothing but a fire and their dogs.

No email to check, no news to watch. Right now, I am blissfully disconnected from the world and utterly attached to everything that is real.

That this has happened so close to the New Year has gotten me thinking about resolutions. There was a time when such a thing was a priority in my life. I greeted every January 1 with not one vowed To Do but several, a long list of things to change and improvements to make. That mostly ended right around the time the kids arrived. It isn’t their fault. I just got tired of the constant disappointment of beginning the new year a new person, only to find the old me was really there all along.

I was always adding something, you see. Always thinking the way to move forward in my life was to either get or become more of something. There’s a certain logic to it, however childish that logic may be—more equals better. I think a lot of us fall for that one.

Sometimes it takes mornings like this to see things as they really are. There are times in life when everything is as silent and dim as it is in my living room right now. We blame others for that. We blame God. Sometimes we even blame ourselves. But maybe it isn’t a matter of blame at all. Perhaps it’s more an opportunity to understand that having more often means needing less.