Billy Coffey's Blog, page 22

March 17, 2014

As plain as the nose on my face

Here’s one of those seemingly random and inconsequential facts about the human body: your nose is always in your field of vision. Cross your eyes. See? It’s right there, right where it’s always been, centered as a ridge just below and between. And yet uncross your eyes again, and it’s gone.

Here’s one of those seemingly random and inconsequential facts about the human body: your nose is always in your field of vision. Cross your eyes. See? It’s right there, right where it’s always been, centered as a ridge just below and between. And yet uncross your eyes again, and it’s gone.

I read that seemingly random and inconsequential fact about the human body about a half an hour ago. Now, I can’t stop seeing my nose. Nothing has changed about me or my field of vision. The only thing that’s different is that I know my nose is there now. I’m aware of it, just as I’m now aware that the only reason we never really notice our noses is because our brains basically edit them out.

That last point—that our brains edit out our noses—is maybe what’s bugging me most of all. I can’t let it go.

Blind spots are things we all no doubt learned at some point in our schooling, but also something that gets misplaced as the years wear on. They are considered meaningless when it comes to real living, like the Pythagorean theorem or the capital of Turkey—trivial things that lose their value in an adult life that revolves around keeping one’s head above water. But I think this particular bit of trivia is very important indeed, if only because it teaches us so much about ourselves. It means that the world we perceive isn’t the world as it is, isn’t even really the Truth at all. It’s just our brain’s best interpretation of Truth.

So now I’m wondering what else I’m missing when I look out into the world. The human mind is a wonderful instrument. It is capable of pondering the mysteries of the universe and solving our most pressing problems. It has built pyramids and skyscrapers. It has mastered fire and agriculture. And yet even that wondrous lump between our ears can’t process everything that is going on around us. It must filter the things we do not need in order to focus upon the things we do. It’s the important stuff that the mind allows us to see. Or at least, what our minds consider as important.

Which has gotten me wondering—what other blind spots do I have? I’m not talking about the ones that affect my brain. I mean the more important ones. Ones that affect my heart. What am I missing not in my world, but in my life? What things are there that I don’t always think are important but really are? How do I spend my time, and how can that time be better spent?

Am I chasing after something that I believe will add to my life but will instead only lessen it?

Are the priorities I’ve set for my life the same priorities God has set for me?

Heavy questions, all. But it’s the hard questions about who we are that require hard answering. After all, it doesn’t bode well for us to move through our lives half blinded. Not just to the world, but to ourselves.

March 13, 2014

“Devil” makes the rounds: Release week

It’s been a great week (and did you hear the “Whew!” as I wrote that?). The Devil Walks in Mattingly is now officially released, and with it came a flurry of reviews, interviews, and about everything else you could imagine, all made better by good folks like you.

I’ll be doing a giveaway here next week. In the meantime, here’s a sneak peek at some of the things people have been saying:

Interviews:

Publishers Weekly Billy Coffey: Writing a Different Ending

Windows and Paper Walls The Devil Walks in Mattingly-Q&A with Billy Coffey

AndiLit(dot)com Write Naked: A Writers Writer Interview with Billy Coffey

Ordinarily Extraordinary The Devil Walks in Mattingly by Billy Coffey

Flickers of a Faithful FireFly Coffee with Billy Coffey and a Giveaway

Reviews from the Heart Sittin on the porch talking with Billy Coffey!

Reviews:

Publishers Weekly Fiction Book Review: The Devil Walks in Mattingly

The Christian Post Novel Considers the Destructive Nature of Secrets and Regret

Faith, Fiction, Friends “The Devil Walks in Mattingly” by Billy Coffey

Patheos via Karen Spears Zacharias The Devil Walks in Mattingly

Guest spots and other things worth mentioning:

Faith Village The Devil Walks in Mattingly/Billy Coffey: excerpt

Southern Living: The Daily South Five Things You Need to Know in the South Right Now

The Good Men Project A Father’s Long Shadow:Author Billy Coffey speaks about the effect his father had on his life, and where it’s brought him now

Katdish(dot)net In Like a Lion: Favorite book releases in March

***

If you’d like to help spread the word about The Devil Walks in Mattingly, you’re invited to join the Launch Team on Facebook. We’d love to have you!

March 10, 2014

The Devil Walks in Mattingly

It’s human nature to want, then get, then want some more. All those shiny things that come into our lives can dull over time. The new gets old. That’s been proven true many times over in my life except for a few precious things. Today is one of those things.

It’s human nature to want, then get, then want some more. All those shiny things that come into our lives can dull over time. The new gets old. That’s been proven true many times over in my life except for a few precious things. Today is one of those things.

My newest novel is released today—that makes number four, which just so happens to be four more books than I ever thought I’d get the opportunity to write.

The Devil Walks in Mattingly should be available everywhere. It’s a great story, and my favorite so far.

Below I’ve posted links to where you can pick up a copy, just in case you’re in need of something new to read. And as always, I thank each and every one of you who take the time to visit my little cyber cabin in the mountains. None of what I do would be possible without you. Cross my heart and hope to die.

Available from these fine online retailers and your local brick & mortar book store:

March 6, 2014

Harriet’s masterpiece

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

Sitting beside me as I write this is a robin’s nest. Dislodged by a recent gust of wind, it tumbled from the oak tree in my backyard and was caught in a pillowy blanket of fresh snow, where it was picked up by me.

The finding of the nest did not catch me by surprise. I knew the nest was there and that it would soon not be. I am generally well educated on the goings on of the winged and furred creatures who inhabit my tiny bit of Earth. We coexist well, them and I. Their job as tenants is to remind me of the world I sometimes neglect to consider. My job as caretaker is to feed and water them as best I can. And, as a side benefit, to name them whatever I think is most fitting.

The robin who resided in my oak tree was named Harriet. How I arrived at that particular moniker escapes me and I suppose doesn’t matter. What does matter, however, is that Harriet was my favorite. The rabbits and squirrels and blue jays and cardinals were all fine in their own way, of course. But Harriet was my bud.

She was my security system in the event the neighbor’s cat decided to snoop around for a quick meal. She was the perfect mother to the four robinettes she hatched. And she sang. Every morning and every evening, regardless of weather. Even after the worst of storms, when the rains poured and the thunder cracked and the winds whipped, she sang.

I envied Harriet and her penchant for singing regardless. And when the weather turned cold and she sought her refuge in warmer climates, I missed her too.

And now all I have left is this nest to ponder.

An amazing piece of workmanship, this nest. Bits of string, feathers, dead flowers, twigs, and dried grass woven into a perfect circle, with a smooth layer of dried mud on the inside.

The resulting combination is protective, comfortable, and a wonder to behold. Harriet likely took between two and six days to construct her home and made about a hundred and eighty trips to gather the necessary materials. She may live up to a dozen years and build two dozen nests. I like to think this one was among her finest.

Scientists have taken much interest in this facet of bird behavior. They’ve even come up with a fancy name for it: Caliology, the study of birds’ nests. Artists and poets have found bird nests to be a fertile subject matter. During the 2008 Olympic games, when the Chinese erected the largest steel structure in the world to serve as center stage, it was built in the shape of a bird nest.

Why all this interest? Maybe because of its inherent perfection. You cannot make a better bird nest. The form and function cannot be improved upon. Even more astounding is that Harriet built this nest without any education. Where to build it and with what and how were all pre-programmed into her brain. No experience was necessary. And though my brain protests the possibility, I know that this flawless creation of half craftsmanship and half art is not unique. It is instead replicated exactly in every other robin’s nest in every other tree.

Instinct, the scientists say.

We humans are lacking in the instinct area, at least as far as building things goes. In fact, some sociologists claim that we have no instincts at all. I’m not so sure that’s true. I am sure, however, that things do not come so natural to me. I must learn through an abundance of trials and many errors. My education comes through doing and failing and doing again, whether it be as simple as fixing the sink or as complicated as living my life. Little seems to be pre-programmed into my brain. When it comes to many things, I am blind and deaf and plenty dumb.

I said I envied Harriet for her singing. The truth, though, is that I am tempted to envy much more. How nice it would be to find perfection at the first try. To know beforehand that success is a given.

That I am destined to struggle and stumble and fail sometimes prods me into thinking I am less.

Maybe.

What do you think? Would you rather be a Harriet and get it right every time? Or is there much to be said for trying and failing and trying again?

March 3, 2014

When the gray seeps in

image courtesy of google images

I blame the writer in me for the messes I sometimes get myself into, all of which I tell myself were begun with the best of intentions. Label something as “research,” for instance, and a writer can give himself permission to do almost anything. “Education” is another good example. We should always be learning something, growing, both in mind and in heart: becoming both better and more.

That thought was running through my head several times over the course of the past couple of weeks, when I decided to sit down to watch three of the most celebrated television shows to have come along in a while. The writing is spectacular, I heard. The ideas immense. Deep characters. Deeper mysteries. All things that appeal to me in my own work. The best way to improve your own craft is to immerse yourself in the craft of others. That’s what I was thinking when I sat down to watch marathons of Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones, and True Detective.

If you’ve yet to see any of these shows or only a couple, I’ll say they are at their core the same thing: Broken people doing some very bad things. Their worlds could not be more dissimilar—the monotony of suburbia, a feudal Dark Age, the stark backwater of the south. And yet the view of each of those worlds is much the same in that each show portrays the world as ultimately meaningless and empty, therefore power is the only means to safety. The critics I’d read and the friends who had recommended those shows were indeed right. The writing really was spectacular, the ideas really were immense. The characters were layered. A few of the mysteries were nearly imponderable.

But still: yuck. After all of that, I needed a shower.

Here’s the thing, though: given bits and pieces of those shows, I don’t think it really would have been a problem. I’m no prude when it comes to entertainment; I’ll admit I sometimes enjoy my share of a gray worldview, though I’d much rather see it from my sofa than in my own life. But immersing yourself in it? Watching over and over until it seeps into the deepest places inside you? Well, that’s a different thing all together.

Yet that’s our culture now, isn’t it? There really doesn’t seem to be any hope out there, whether it’s in music or television or literature. There was maybe a time when the arts existed to prod society onward, to inspire and lift up. More often than not, they now serve as a mirror, showing what we’ve become in a series of melodies or flashing frames. Television, movies, music, and stories have grown increasingly dark because we’ve grown increasingly dark, not the other way around.

The other day, I came across an article written by a neuroscientist that affirmed much of what our mothers once told us: garbage in, garbage out. The article cautioned great care in the sorts of stories we allow ourselves to be exposed to, whether it’s the nightly news fare of war and recession and political meanness, or whatever slasher film is playing down at the local movie theater. Because those stories all carry meanings, and those meanings will, consciously or not, impact the way in which you view life and the world around you for good or bad. If you don’t know how to draw something positive out of what happens in life, the neural pathways you need too appreciate anything positive will never fire.

That’s evolution, the neuroscientist said. Maybe. I’d call it human nature.

It’s easy to succumb to the notion that everything is random, meaningless. It’s easy to fall into the trap of believing that the world is too big and too far gone to ever be able to make a difference in it. The key is not to rise above, but merely survive (which, by the way, is my theory of why the zombie culture is so prevalent now). What’s hard is to believe. What’s hard is to carry on. It is to find purpose in where you are and in what you’re doing, no matter how insignificant it seems. It is to find dignity in this thing we call life, and to bring beauty to it.

February 27, 2014

The waiting (is the hardest part)

image courtesy of google images

For two months he has saved every penny and dollar, every bit of allowance and report card money, counting it all weekly and sometimes daily, all for the Lego train set that is due to arrive upon our doorstep sometime today. My son is proud. I’m proud of him. It takes a lot of work and discipline to save that much when you’re nine years old, to say No and No again to the pack of baseball cards or the long aisles of toys down at the Target. To say instead, This is what I want, and even if I can’t have it today, I’ll have it eventually.

It got easier as it went. Saving so much money, I mean. When you’re first starting out, all you see is how little you have and how much you need. You think you’re never going to get there. The road is too long, the temptations too great. That’s when most give in. That’s when I give in. And my son nearly did, but then twenty dollars turned into fifty, and that became seventy-five, and then a hundred and fifty, and now all that’s left is to stare out the window to a dull February day and wait for the sound of the UPS truck.

It’s been a great lesson, really. Saving up, sacrificing immediate gratification for something better down the line, learning the value of hard work and determination. Kids need a lot of that nowadays, I think. Adults too, for that matter. But now comes another great lesson, and in many ways a much more difficult one to digest and endure.

Now comes the wait.

So he sits in the recliner with the dog (who knows something important is happening but isn’t sure what, and so just waits with her ears back and her nose to the air) and rocks because he’s too anxious to hold still. Every sound of an approaching engine is greeted with a sudden jerk of his head, body flexed, chest puffed, waiting to charge the door like a sprinter out of the blocks.

So far, there have been four trucks, three cars, and a woman on a horse. No UPS truck.

It’s not coming, he says.

Yes it is, I say.

Well then, where’s it at? he asks.

Out for delivery.

How do you know?

Because that’s what the tracking says.

But what if he wrecks before he delivers it? And what if my train goes flying out of the truck because it’s rolled over five times and some other kid picks it up and takes it home and doesn’t help the driver at all, and the driver just sits there and bleeds to death? What then?

I don’t have an answer to that, other than to think my son may make a good novelist one day.

Just hang on, I tell him. Just wait.

And then he says the two words that sum up so much of what it means to live in this world, to want and dream and strive and hope—

Waiting sucks, he says.

It does, I tell him, and then I tell him that “sucks” really isn’t the kind of word he’s supposed to be saying, especially with his mother right in the next room. But since he referenced it with regard to waiting, I let it slide. Because he’s right, you know. Waiting really does suck.

We spend so much of life doing that. We wait to grow up, wait to graduate, wait to fall in love and graduate from college, wait for a good job and to have kids and to retire. Sometimes, we even wait to die. I’ve read the normal person will spend fully ten years of their lives waiting in some sort of line, whether it’s the post office or the grocery store or the bank.

With all that time spent waiting, you’d think we would get pretty good at it. But we aren’t. Waiting hurts. Waiting reminds us too often of the thing we want and how miserable we are without it, whether it’s something to have or someone to love. It convinces us we’re somehow less without it. We ache and we pine and we pout. And it doesn’t have to be something big, either. Sometimes, it can be something as insignificant in the big picture as a Lego train. But that’s the thing. I don’t think most of us really want a lot in life, we just want a little more than what we have.

So I’ll just sit here for a while with my son and stare out the window with him. We’ll talk while we wait. We’ll laugh and giggle. We’ll discuss the deeper things of Lego creation and growing up. Because that’s the thing, too—waiting might indeed suck, but it sucks a lot less when you have someone else there, waiting with you.

February 24, 2014

The John she used to know

image courtesy of google images

Dorothea will tell you she and John would have been married 47 years come June. That’s how she always puts it—“would have been” instead of “will be”—past tense instead of future, even though John is still alive and they are still married. They still live in the same brick house two blocks from the Food Lion; are still seen driving the same gray sedan, though these days it is Dorothea driving John. He still gets around, she’ll tell you that as well. She’ll say her husband still reads the Richmond paper each morning and still takes his coffee strong and black and that both are absolute. What is not absolute, and in fact what Dorothea now questions every day of her life, is where her husband has gone, and who has taken his place.

They have four children, each of whom are grown and two of whom have moved away. Ten grandchildren, four great-grandchildren. The entire family gathers twice a year at the old home—every Christmas and Fourth of July. Those are festive times. Dorothea says there must be some special magic when the whole family is together, something about the sound of conversation and giggling children, that makes her husband feel like her husband again.

Those other 363 days can often be long. Sometimes they can be frightening, such as the afternoon last November when John went to check the mail and never returned. Dorothea found him three blocks and fifteen minutes later, sitting in the middle of the road, his bathrobe open and tossed by the breeze.

It began sudden, a year ago now, the same way so much bad in the world begins—with something small and ordinary. John had a history of migraines, and while the headaches that had plagued him for weeks were neither strong nor lasting enough to be called those, they were enough of a nuisance that Dorothea scheduled a doctor’s appointment. Tests were done. The doctor called them both back into his office three days later with the news. There was a tumor on John’s brain. It was inoperable.

The doctor said three months, six at the most. John’s outlasted both of those predictions. He always was a tough man, Dorothea will tell you. That’s how she’ll put it—“was” rather than “is.” Because she doesn’t know if the man she would have been married to for 47 years come June, the man who has given her four children, a brick house, a gray sedan, and a good life, is really John at all. She thinks that person left. Most of us in town would agree.

He was always a nice man, a kind man, easy with praise and concern about how you and your family are and if you’re still going to church every Sunday. In all their years together (much more than 46—John and Dorothea dated five years before they married), she had never heard him cuss. Three days after that fateful doctor’s visit, John came inside the house and said the damn key wouldn’t fit in the damn ignition of the damn car.

The cussing has grown worse since—horrible words that Dorothea never thought her husband capable of uttering. He’s grown impatient with the world, cursing the neighbors and the government and “the whole damn thing.” Once, he grew violent and pushed Dorothea against the kitchen sink, screaming at her, wanting to know what she’d done with his wife.

Though she remains strong and faithful, Dorothea has said she often wonders why she must sit idly by, watching as what remains of this man’s life slowly slips away. She wonders too how it is that a mass of deformed cells pressing against her husband’s brain can turn him into someone else. In all outward ways, he is still John. It is still his face and his body, the same hairline and mole just below his right ear. And yet he is no longer John. He has become someone else. He has become a stranger.

And Dorothea is left to wonder this: What makes us “us?” What is that quality that defines us and renders us unique? Where does that quality lie? And perhaps most important of all, where does that quality go when it appears to be taken away?

I don’t know the answer to that question. It breaks my heart that John and Dorothea must endure such a thing, and that there are so many others who must endure it as well. It hurts. It’s not fair.

But Dorothea isn’t angry. That’s what has struck me most about her these last months. She’s not mad at John, nor his tumor, nor even the God who doesn’t seem interested in healing them—in bringing her husband back. It’s remarkable to me, though not to her. To Dorothea, the question now isn’t Why. It isn’t How. It’s only What.

“God wants me to take care of him,” she says of the man who used to be John. “That’s all I need to know.”

And so she will, until some near or far-off day when Dorothea will say goodbye to him for now. Only for now. And the faith she has that God will equip her to care for her husband now is the very faith that allows her to know that when they meet again, it will be John she sees. The old John. And he will thank her.

February 20, 2014

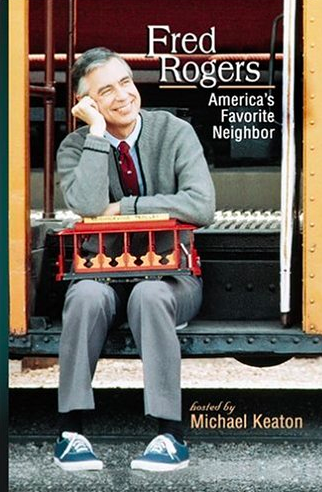

My neighbor and hero

image courtesy of google images.

Time has a way of wiping the memory, compacting chunks of years into months or even days in the mind, glossing over even those recollections we once held as precious. There is much I’ve misplaced about my childhood, but one thing stands out even now: those long days when I sat prostrate in front of the television, my knobby knees tucked under myself, back straight and eyes forward, waiting for Mr. Rogers to come on.

It was much the same with you, I would imagine. Generations of people grew up visiting Mr. Rogers and his neighborhood each day. We grew up with him. Learned with him. No matter who we are or what we’ve become, our childhoods have him in common.

Growing up, he was my hero. I wanted a sweater like his and a sandbox like his, and I pined for a magical train that would run through my house to distant lands. It was time that separated us, no longer made us neighbors. When a boy (or a girl, for that matter) reaches a certain age, Mr. Rogers is no longer cool. Mr. Rogers becomes a nerd. A dork. He’s no longer a friend, he’s the weird old man down the street.

How stupid we all are.

In 1997, after 33 years of teaching us all how to look and listen and act, Fred Rogers was given a lifetime achievement award at the Daytime Emmys. It was quite an odd sight, seeing him and his wife among some of the most famous and powerful people in Hollywood. And yet he took the stage to receive the award accompanied by a standing ovation that ended when he stood in front of the microphone. What happened next can only be described as magical. I ask you to take three minutes out of your day to watch:

Video from KarmaTube

How wonderful is that? How beautiful that this humble man (who was an ordained minister to boot) stood upon that glimmering stage in all that pomp and circumstance, holding a statue coveted by so many, and made it all not about him. And more than that, he reminded everyone else that it wasn’t all about them, either. It was instead about the ones who had been there to support them, to love them, to help them. In an age defined by the individual, Fred Rogers taught us in ten seconds that we are all connected to one another.

But there’s more. What struck me most watching that speech was that such a powerful truth had been given with such meekness and humility. How hard do you think it would be to convince a crowd of Hollywood actors and actresses to pause for a moment and think about someone other than themselves? To forget their fancy dress and their high status? And yet Mr. Rogers did just that, and merely by looking at his watch.

“I’ll watch the time.”

That’s all it took. There is a small rumble in the crowd, a few chuckles, and then utter silence. Because Mr. Rogers wasn’t kidding. He was serious, he wanted them to do this. And when Mr. Rogers asks that you do something, you do it. Not because you’re scared or intimidated, but because a part of you knows that he loves you.

Because he’s your neighbor.

As a result, Fred Rogers got exactly what he wanted that night. Not applause, not a statue. He convinced all of those people that they are indeed special, not because of what they’ve become, but because of who they loved and who loved them.

And that is why Mr. Rogers was my hero growing up. And now that I’m grown, why he’s my hero still.

February 17, 2014

The DNA of our humanity

The article from the Associated Press is headlined, “Human genes reflect impact of historical events,” and goes into some detail of how researchers used nearly 1500 DNA samples to map genetic links going back 4,000 years. What they found was surprising to some. To others, not so much.

The article from the Associated Press is headlined, “Human genes reflect impact of historical events,” and goes into some detail of how researchers used nearly 1500 DNA samples to map genetic links going back 4,000 years. What they found was surprising to some. To others, not so much.

Science has never really been my strong suit. Whether it was earth science in elementary school, biology in junior high, or a brief but thoroughly disastrous flirtation with chemistry as a senior in high school, a solid “C” was all I could ever hope for. But as the years have gone on, I’ve found myself drawn to the subject. Physics helps me better understand the universe, biology the world. And while much of it still flies straight over my head, that small article from the AP truly struck me. It made sense. And more than that, it helped confirm what I’ve considered a strong possibility for quite some time.

These researchers managed to link certain strands of DNA to historical events. They used samples from the Tu people of China to show they mixed with the ancestors of modern Greeks sometime around 1200. They confirmed that the Kalash people of Pakistan are descendants of Alexander the Great’s army. They showed how African DNA spread throughout the Mediterranean, the Arab Peninsula, Iran, and Pakistan from A.D. 800-1000 due to the Arab slave trade.

Interesting stuff to be sure, but on the surface maybe not that interesting. Truth me told, I clicked off that article and moved on to something a little more my style (it happened to be a recap of this past week’s episode of Justified) before hitting the BACK button and reading it again, slower this time. Because buried beneath all those dates and facts was a reminder I sorely needed, something magical and amazing, though for the life of me I couldn’t quite put my finger on it.

And then it hit me that too often we consider ourselves merely in terms of the physical and temporal. I am a mass of flesh and blood and bone with a soul hidden somewhere inside. My thoughts rarely extend past this present moment and rarely beyond the things that have a direct impact on me—what I need to finish now, what I need to do next. Sometimes the future will pop up, and I’ll think about tomorrow and the next day and the day after that. Oftentimes the past will rear its head as well, and I’ll ponder how far I’ve come and how much I’m still stuck in it.

That’s all, really, and I’d venture a guess that your life is much the same. We all live in the same world, and yet in that one world are billions of smaller ones. There’s my world and my wife’s world and my children’s worlds. There’s your world, and a separate world for everyone you know. And every one of those smaller worlds are marked by a kind of inherent selfishness in that we really don’t care what happens unless what happens interferes with us—unless it enters our own orbit.

But there’s much more to us than our own past and present and future. There’s more than our own individual worlds. Imbedded within the very fiber of our being is a record of all that has gone on before us, millennia’s worth of wars and droughts and migrations, ages of histories long lost and forgotten. I am not a single person, and nor are you. We are instead the product of countless generations who came before, who settled and lived and struggled through hardships we cannot fathom and yet found a way to continue on. Our ancestors may be nameless and inconsequential to history. They were very likely poor, unknown. And yet they live on as microscopic strands of our DNA because they managed to do one incredible thing: endure.

There is something wholly magical and noble in that. We are unique and special, and yet no more so than all who came before us. The struggles we face were once theirs, as well as our fears and our dreams. That makes me wonder just how separated we all truly are.

February 13, 2014

Welcoming the storm

The snow storm has arrived.

There’s a storm coming. No one around here needs to turn on the news to know this, though if they would, they’d be greeted with an unending stream of weather updates and projected snowfall totals. “Gonna be a bad one, folks,” the weatherman said a bit ago. But I knew that when I walked outside. It was the way the sun hung low in a heavy, gray sky, and how the crows and cardinals and mockingbirds sounded more panicked than joyful. It was the five deer coming out of the woods and the raccoon in the backyard, how they foraged for enough food to last them these next few days.

We are no strangers to winter storms here. Still, it is cause for some interesting scenes. There are runs on bread and milk, of course, and salt and shovels, and there must be kerosene for the lamps and wood for the fire and refills for whatever medications, an endless stream of comings and goings, stores filled with chatter—“Foot and a half, I hear,” “Already coming down in Lexington”—children flushing ice cubes and wearing their pajamas inside out as offerings to the snow gods.

It is February now. The Virginia mountains have suffered right along with the rest of the country these past months. We’ve shivered and shook and dug out, cursed the very snow gods that our children entreat to give them another day away from school. Winter is a wearying time. It gets in your bones and settles there, robbing the memory of the way green grass feels on bare feet and the sweet summer smell of honeysuckled breezes. It’s spring we want, always that. It’s fresh life rising up from what we thought was barren ground. It’s early sun and late moon. It’s the reminder that nothing is ever settled and everything is always changing.

But there’s this as well—buried beneath the scowls of having to freeze and shovel, everywhere I go is awash with an almost palpable sense of excitement. Because, you see, a storm is coming. It’s bearing down even now, gonna be a bad one, folks, I hear a foot and a half, and it may or may not already be coming down in Lexington.

We understand that sixteen inches of snow will be an inconvenience. We know the next day or two will interrupt the otherwise bedrock routine we follow every Monday through Friday. And yet a part of us always welcomes interruptions such as these, precisely because that’s what they do. They interrupt. They bring our busy world to a halt. They slow us down and let us live.

Come Thursday morning, I expect to see a world bathed in white off my front porch. I expect to put aside work and worry and play instead. I’ll build a snowman and a fort. I’ll throw snowballs and play snow football and eat snowcream. I’ll put two feet so cold they’ve gone blue by the fire and sip hot chocolate. I’ll laugh and sigh and ponder and be thankful. For a single day, I’ll be my better self.

That’s the thing about storms. We seldom welcome them, sometimes even fear them. Too often, we pray for God to keep them away. Yet they will come anyway, and to us all. For that, I am thankful. Because those storms we face wake us up from the drowse that too often falls over our souls, dimming them to a dull glow, slowly wiping away the bright shine they are meant to have.