Billy Coffey's Blog, page 19

July 4, 2014

The banner still waves

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

I’ve heard there are grumblings that “The Star Spangled Banner” should be removed as our national anthem. It’s too antiquated, those grumblings say. And the words are not only hard to understand, but hard to sing. What kind of national anthem do you have if it’s hard to sing?

And to tell you the truth, some of those grumblings are right. I’ve heard the anthem positively butchered by well-meaning folks who were simply mystified by the phrase “O’er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming.” I couldn’t sing that, either.

That isn’t to say, though, that I’m all for replacing the words of Mr. Francis Scott Key with “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” or “America the Beautiful.” I’m not. I like things the way they are just fine. Not because I love our anthem. Not because I love the words.

But because it’s endured.

We are a people who look ever forward. Hope and change are our new touchstones, and neither of those are readily found by glancing over our shoulders. No, the promised land of better times lies ahead. Just there, over the horizon.

We say that the past doesn’t matter, just the future. Not where we’ve been, but where we’re going. And while that may be correct in some aspects, it isn’t in others. In many ways the future is dependant upon the past, and you don’t know where you’re going unless you take a look behind to see where you’ve been.

That’s true in both the life of a person and the life of a country. We are not the product of our tomorrows, but our yesterdays. The freedoms we enjoy may be sustained by the continued sacrifice and vigilance of today, but they were granted by the courage of those who have gone before us. Men who held firm to the believe that freedom was worth persecution and that death should be favored over oppression.

Men who put country and people ahead of party and self. Who believed leaders were not above the public but subject to them.

Who believed that the ultimate authority was not themselves, but God.

That we continue to cling to what some see as a worn and outdated song for our national anthem is to be reminded that there was a time in our country when such men existed. Perhaps that’s why there is this slight but steady push to modernize the singing of praise for our country. It will help us cope with the knowledge that such men seem to be more difficult to find now.

Whereas our leaders of yesterday are revered, our leaders today are ridiculed. Our trust with those first great Virginians, Washington and Jefferson and Madison, have been replaced by a mistrust for those who lead us today. This, I suppose, is inevitable. The natural consequence of favoring a winning smile and a photogenic face over substance and wisdom.

Those ideas of freedom and liberty that inflamed the hearts and minds of our forefathers seem to have burned to embers now. What caused them to stand and fight now allows us to sit and rest.

So this Fourth of July weekend when we’re surrounded by the present and looking forward to the future, perhaps it would do us well to pause and look back, far back, and remember the kind of people it took to found this country. Because that is exactly the kind of people we need in order to continue it.

Let the words be sung, and let that flame of freedom and liberty ignite again. Let us all make sure that when the question is asked, “O! say does that star-spangled banner yet wave O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?” the answer will always be yes.

June 30, 2014

One bad egg

It started out bad, that was the problem, and what made it worse was my son and I knew that but thought we could make it better. But it was Saturday. We had promised all week that come Saturday, we’d make breakfast. Not the easy kind, either—no milk over cereal, no way. It would be fresh juice and omelets and slices of fruit.

It started out bad, that was the problem, and what made it worse was my son and I knew that but thought we could make it better. But it was Saturday. We had promised all week that come Saturday, we’d make breakfast. Not the easy kind, either—no milk over cereal, no way. It would be fresh juice and omelets and slices of fruit.

Before I continue, this one point needs to be made abundantly clear—I cannot cook. The milk over cereal option that my son and I both rejected is the epitome of my culinary skill. Even then I’ll mess up from time to time, either drowning my corn flakes or not putting enough milk into them, creating a desert in my bowl. It’s a delicate balance, cereal.

But omelets seemed a simple enough thing. My son had promised he’d made them before and to great effect. He’d even already procured the ingredients by the time I stumbled into the kitchen that morning for coffee. “The eggs,” he told me. “We gotta crack them first.”

I can crack eggs.

Into the bowl the first one went (one-handed, thank you very much) and that’s when we found our problem. It was that egg. All green and gooey looking, and with a smell that rivaled anything that could come out of my son’s body. We bent over the bowl, staring at it and frowning.

“That’s bad,” he told me.

“Guess we should just throw it away, then.”

“We can’t. We only got four more. We’ll need them all.”

“Can’t leave a bad egg in there,” I said. “Maybe we should just go with the cereal.”

“We promised there wouldn’t be any cereal.”

And that was true. It was either omelets or I drive down to the Hardees, and my wife and daughter would know it was Hardees. It doesn’t mean much when all you do to make breakfast is spend gas money.

“Maybe if we just put in more good eggs, it’ll make the bad one taste good.”

I stood there, thinking on that. I will admit I found a certain logic to it.

“Let’s try.”

It all went fairly smooth from there. The other eggs were as fine as they could be; it all came together nicely. Except for the green tint in it all.

“I’m not eating that,” my wife said.

“No way,” said my daughter.

I didn’t blame them. No way I would’ve eaten it, either.

I guess that’s why people say we need a Savior. Because we all start out with one bad egg in a bowl that we can’t ever throw away, and so we get it in our heads that the more good eggs we put in, the more good things we do and the more time and effort we give, sooner or later that bad egg will be turned into a good one.

But that’s not how it happens, is it? Our lives get to be like our omelets instead—the bad isn’t made less by all the good, the good all becomes stained with the bad.

I know that now. I also know this: next time, it really will be cereal and milk.

June 26, 2014

Skipping to the ending

My daughter is a reader. Reads everything. Novels, poetry, history, cereal boxes. Doesn’t matter what it is. Most people pack clothes before they go on vacation. She packs books.

My daughter is a reader. Reads everything. Novels, poetry, history, cereal boxes. Doesn’t matter what it is. Most people pack clothes before they go on vacation. She packs books.

I encourage this. In an age when no one really reads anymore, it’s good to have at least someone out there whom I know will read my books, if not now then someday.

She dog-ears pages, just like me. Underlines those passages that particularly grip her and writes notes in the margins, just like me. A book is like a shirt, she says. You gotta break it in.

One thing drives me crazy, though. When it comes to a story, my daughter must always begin with the end. She reads the last page first, reads it carefully, looking as though she’s actually chewing the words for their taste. Names and characters don’t matter here, nor the setting. It’s the tone she’s after. The feeling. She’ll read books that lift her up and books that break her heart (an equal opportunity reader, my little girl), but she has to take a peek at the end first. Good or bad, she has to know what she’s getting into.

I tell her I hate this on principal, both as a novelist and as a human being. I say she’s robbing herself of something wonderful and magical. She’s denying herself a journey of the mind and heart and the chance to grow as a human being.

What’s the fun, knowing the end?

She shakes her head at me, says I don’t understand. She’s right. I don’t.

I was in her bedroom last night tucking her in. (“Tucking her in” = “Would you put that book down and GET SOME SLEEP?!?”) I heard her before I saw her. The bed is in the corner of the room, nestled into two corners, better lighting for her to read. A sniffle. Not the dry sort of allergy sniffle, the boy-howdy-the-pollen-is-awful-this-year sniffle snort. No, this one was wet. Snotty.

Sad book.

She was crying. She’s a cryer, my girl. Any commercial with a sappy score to it will do her in. To this day, I hate Sarah McLachlan just because those SPCA commercials she does sends my daughter over the edge. Sitting up in bed, hunched over a paperback. Eyes wide and glassy, a crumpled tissue in her hand.

“Calvin and Hobbes?” I tried. (Humor, my spiritual gift!)

“Stop it.”

“Bad one, huh?”

She nodded. “She just died. She DIED. It’s not fair.”

I didn’t know who “she” was. I supposed my daughter wanted me to ask. I didn’t. Don’t judge me.

“Maybe you should try to read some lighter fare,” I said. “You know, least at bedtime.”

“No, I like this one. This one’s good. And I know it’ll be okay.”

“How do you know that?”

“Because I peeked at the end.”

Ah.

I let her read a while longer that night. No sense in having to call it a day at a sad part.

But there are a lot of those, aren’t there? Sad parts, I mean. Vast sections of our lives that look and smell and seem purely tragic. Hard times that feel like we’re under God’s boot heel. Times of grief and anguish, when everything around you is shouting to just give up, it doesn’t matter anymore.

Don’t. That’s what I’m here to tell you. Don’t give up, because it does matter and I know it does, because I’ve peeked at the end.

I’ve peeked and seen a new heaven and a new earth, where death is no more and eternity has taken its place.

I’ve peeked and seen a final wiping away of our tears by a hand too large for this universe that brushes our cheek like a feather.

I’ve peeked and seen the end of every struggle.

You, me, we know how it all ends. And maybe that more than anything else is what gets us through the sad parts.

June 23, 2014

Homeless here on earth

I’m always reminded of heaven when I’m on vacation, though maybe not in the way you’d think. Were you afforded a window seat upon fifty-one weeks of my life, what you’d be privy to wouldn’t be much in the way of excitement. I get up early and greet my family, kiss them goodbye as we part ways into the world. I go to work, do my job. Come home to family again. We do chores and eat supper. We take walks and sit on the porch. We talk. We laugh.

I’m always reminded of heaven when I’m on vacation, though maybe not in the way you’d think. Were you afforded a window seat upon fifty-one weeks of my life, what you’d be privy to wouldn’t be much in the way of excitement. I get up early and greet my family, kiss them goodbye as we part ways into the world. I go to work, do my job. Come home to family again. We do chores and eat supper. We take walks and sit on the porch. We talk. We laugh.

That’s it, for the most part. It’s an unspoken but mutually agreed upon goal that all is done with a common goal in mind: live quietly. It’s a good goal to have, and one in which we usually succeed.

With that in mind, I suppose you could ask what in the world we need a vacation from. Fair enough. It is a quiet life for us here among the mountains and hollers, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t without complication. The days still wear on you in that slow and awful way that makes you consider whether the long string of your everydays is really just some long, unfurling tragedy.

After a while, even life in the country gets old.

Fortunately, that’s usually about the time I pack up my family and run away.

For the last few years, our spot to escape is a slender little island off the coast of North Carolina. A magical place, truly. The sort of spot where you can sit on your balcony and see dunes and ocean and deer in the same blink. Where the beaches are empty except for the whales and turtles and fish, and where each day the surf washes so many shells upon the sand that you could never possibly count them all.

I’ll tell you this, friend—that’s the kind of place that gets into your bones.

The drive there (about six hours according to the maps, about six-and-a-half when factoring in a few walnut-sized bladders) is usually an event in itself. We say goodbye to our little town, goodbye to the old men who seemingly live on the bench in front of the 7-11, goodbye to the mountains and to Virginia itself. It’s a sloughing off of what hard skins we’ve grown over the year, all accompanied by endless Jimmy Buffett songs and plans made not with the calendar, but low tide charts. We arrive not at a destination, but at a feeling. And for five blissful days, there is no doubt in my mind that I have exchanged the place where I was born for the place where I belong.

Yet five days, no matter how blissful, do not make a week. That’s when I start thinking of heaven.

That’s when I take my morning coffee out to the deck and see that wide and endless stretch of water not as the wonder that it is, but the wonder that it isn’t. It is flat, the ocean. Pocked by whitecaps and boats and the bobbing dolphins, but flat nonetheless. Not like my mountains. And though it is blue, it is of a greenish hue rather than the cobalt of the Blue Ridge. The beach is empty. There are tall dunes, but no tall forest. Town is busy rather than lazy.

For those two days between vacation and the resumption of my life, I realize this one truly amazing fact: I am homeless on this earth.

I can be comfortable here, happy with my mountains and my sand. I can find inspiration from them both. I can find a purpose. But I cannot belong here, not truly, and nor can you.

You and I, we were made for a place elsewhere.

June 19, 2014

A writer’s learning curve

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Though the homes in my neighborhood are equipped with modern necessities such as central air and electricity, it’s easy at times to think we sit on the border of unspoiled territory. Because for the most part, we do.

Across the road from my house sits about 30,000 acres of national forest, which is home to all manner of creepy crawlies. The boundary between civilized and not is clearly marked by a nearly straight line of neatly-kept backyards and a foreboding tree line of towering oaks.

Of course, neither man nor beast keeps to his own side. We all mingle with each other from time to time. Miles of trails leading into the mountains provide all a guy like me needs for feed his inner redneck. And as if to even things out a bit, everything from bear to deer to snakes to coyotes have been seen wandering our streets.

Most of us pay little mind to such intrusions, believing that the animals have just as much right to snoop around our homes as we have theirs. But there is one person in particular who is uneasy about the whole thing.

I speak of the kid down the road. Sixteenish and free for the summer. I remember the summer I turned sixteen, three glorious months of getting into more trouble than I’d ever gotten into in my life. Ask his father, and he’ll say he almost wishes his son would get into that same sort of trouble. Not a lot, mind you. But at least a little. After all, he’s sixteen. Trouble’s supposed to find you at that age.

But it hasn’t found him, mostly because he refuses to go outside. His days are spent staring out his bedroom window and writing about what he sees. He wants to write a book, he told his father. He’s serious about it. And while his father is supportive, he also knows it’s an excuse. His son doesn’t like his new home. Doesn’t like the small town or the big woods. He wants to go home to the city.

The family moved here from the city last year as the result of a job transfer. All this wildness suits mom and dad just fine, but not the boy. He woke up one morning in April to find a bear in the backyard. Found a snake on the deck a few weeks later. Though he refuses to admit it, they think it was all just a little too Wild Kingdom for him. So when school let out and he was free to do what he wanted, he retreated to the safety of the indoors.

He says he’s spending his time wisely. He’s writing. Working. There isn’t any time for much of anything else.

I heard about all of this the other night while out for an evening walk. His father was putting up a new mailbox, I stopped to say hello, and things just sort of went from there.

“He really is a good storyteller,” he told me. “Just wish he wouldn’t stay inside all the time. That can’t be healthy, can it?”

No.

Not for a kid. And especially not for a writer.

There are a lot of would-be authors out there who think it’s fine to stare out of their window and write about the world. They take their journey within themselves because they’re unwilling or afraid to go out.

I can’t blame them for that. I was once the kid down the road, too.

Not afraid of bears and snakes, but afraid to go out the door. To face life in all its glory and pain. Give me a nice desk and some paper instead. Let life leave me alone so I could write about it.

Sounds a little strange, doesn’t it? But that’s what I thought. And that’s what a lot of authors think.

There is a learning curve to writing, of course. First come the simple words and simpler thoughts, which through countless hours of practice becomes better words and greater thoughts. No one denies this.

But there is another learning curve to writing that often goes overlooked, and that is the experience of living. Of plunging headlong into life and daring to swim in both the clear and the murky waters, and then using pen and paper as a towel to dry yourself off.

You have to hurt. And suffer. You have to love and hate and believe and doubt. You have to fail and succeed.

And the only way to do that is to go out and live before you come in to write.

June 16, 2014

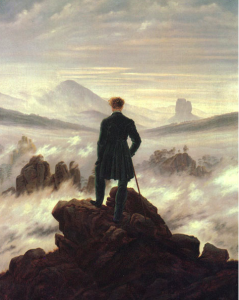

Over the next horizon

“The Wanderer” image courtesy of google images

I’ve read that when it comes to compensation, benefits, work environment, and time off, college professors have the best job in the United States. And since I spend so much of my workday around them, I can’t argue with that assertion. The ones at the college where I work seem happy, are productive members of their community, and have enough extra time on their hands to string together words no one understands to publish books no one reads.

Still, I was curious. Did these people know they had the fortune and blessing to have the nation’s best job? That all of their hard work had paid off to get them the lifestyle of a lifetime? I wasn’t sure. And to me, it felt like something they should know if they didn’t. So I took a few days and asked around.

Two math, one music, three English, a history, and four philosophy professors later, and I was convinced of two things. One was that they knew exactly how blessed they were to have their particular occupation. The other was that it didn’t matter.

Because while all eleven enjoyed their work and got plenty out of it, in their heart of hearts they would still rather be doing something else.

One math professor expressed a lifelong desire for crab fishing, and the other just wanted to run off to Bora Bora. The history professor admitted that she’d always wanted to open a florist shop. Two of the philosophy professors wanted to be farmers, and the other two missionaries. All three English professors wanted to be famous authors rather than ignored ones. And the music professor? “I’ve always wanted to be a bounty hunter,” all one hundred and twenty pounds of him said. (And it’s okay to laugh at that. Because I did).

Those little confessions didn’t surprise me.

Despite what we say about being happy with where and who we are, deep down we’re never where we should be. No matter how hard we chase after our bliss, it always remains just a few steps ahead. Close enough to see, almost close enough to touch, but not quite. There to both inspire us to keep going and taunt us because we haven’t gone far enough.

Psychologists say this difficulty in finding what makes us happy is inborn. As much a part of us as the desire to love and be loved. I want to disagree with that and say that faith can bring us both happiness and a sense of place in this world, but the truth? I have faith, have a sense of happiness and place, but there are still many times when I look at my happy life and think there’s more out there. More happiness. More better.

Whether this makes me any less of a Christian is something I haven’t figured out yet.

There’s a lot to be said for being content with what you have, a sentiment echoed by people from the Apostle Paul (“I’ve learned to be content in whatever circumstances I am”) to Thoreau (“A man is rich in proportion to the number of things he can afford to let alone”) to a country song I heard on my way into work this morning (“…I look around at what everyone has, and I forget about all I’ve got…”).

Wise words, all. And true. Yet here I sit, still wanting more anyway. More dreams, more happiness, more peace.

I suppose we’re all stricken with wanderlust. Deep down we’re all explorers who cannot rest until we reach the next horizon, if only to see what’s there and what’s beyond. The ocean we’re all adrift upon is vast, it’s waters deep, and it’s wonders breathtaking. And though we sail onward, ever searching, our spirits whisper this truth:

We are meant to sail upon the waters of another ocean, where the seas are calm and the winds are fair. And that our happiness now is but a shadow of the happiness that awaits.

June 12, 2014

Getting the pain out

The local convenience store offers more in the way of convenience than most others. Yes, you’ll find the staples of modern life—snacks, tobacco, alcohol, and lottery tickets—but you’ll also find just about anything else. Including a story or two.

The local convenience store offers more in the way of convenience than most others. Yes, you’ll find the staples of modern life—snacks, tobacco, alcohol, and lottery tickets—but you’ll also find just about anything else. Including a story or two.

A case in point:

I stopped by one afternoon last week to stock up on the necessities (bread, milk, and beef jerky). Standing near the coffee pots was Bryan, an old high school friend who worked construction for one of the builders in town. Bryan had come to the store for some supplies as well, though of a different sort. He had managed to talk the lady at the register into giving him a Styrofoam plate and a sheet of aluminum foil.

“Hey, Billy,” he said. “Can you hold this for me?”

I took the plate and foil from him and said, “Okay. Whatcha doin’?”

“Fixin’ my ear. Hold still.” He pulled out a knife and punched a hole through the center of the plate.

I wrinkled my brow and decided to let that go. And then decided not to.

“What’s wrong with your ear?”

“Got something in it,” he said. “Been about a week now. Can’t hear a thing, either. I tried the drops, then a hot rock, then smackin’ my head. Nothin’. It’s killin’ me, it hurts so bad. So now I’m trying this.”

He held up what looked to be a long, hollow piece of honeycomb.

“What are you going to do with that?” I asked him.

“Well,” he said, “I’m supposed to stick this in my ear and light it, and the heat’s supposed to act like a vacuum and suck out whatever’s in my ear.”

I stared at him.

“Seriously,” he said.

“You’re gonna stick that thing in your ear and light it on fire?”

“Yep.”

“What’s the plate and the foil for?” I asked him.

“I’m gonna hold that against my head so I don’t get hurt. I’m not an idiot.”

“Of course not,” I said.

I spent the next ten minutes trying to convince Bryan that his best option was to perform this particular kind of redneck medicine right there in the store so I could watch. He refused. Evidently modesty trumped desperation. Still, it was amazing to me what people would do to get the pain they held inside out.

I was still trying to convince him and still not quite doing it when Stanley Sours walked by on his way to the beer cooler. He snatched a case of Budweiser and passed us on his way to the register.

“Hey, fellas,” he said.

“Stanley,” I said.

“What’s up Stanley?” said Bryan.

Stanley looked at the plate in my hand and the honeycomb in Bryan’s.

“What in the world are y’all doin’?” he asked.

“Bryan’s got something clogged in his ear, so he’s gonna light his head on fire,” I told him.

Bryan nodded.

“Can I watch?” Stanley asked.

Bryan shook his head.

I explained the process to Stanley as well as I could remember it. He was as just as impressed and just as doubtful as I.

“You’re gonna light your head on fire to suck the pain out?” he asked Bryan. “You ain’t all there, are you?”

We all laughed. Stanley slapped both of us on the back and made it way to the register, where he paid for his beer and left.

“He ain’t all there either, you know,” Bryan told me.

I didn’t answer. I didn’t have to. Because he was right, Stanley wasn’t all there. Half of him was in the Ford truck that was pulling out of the parking lot. The other half was about two miles away in a small cemetery plot that held his four-year-old son, a victim of cancer.

That’s when the drinking started. Slow at first and not often, as it always seems to be. Then more. And more. And then Stanley found himself stopping by the store every evening on the way home from work for his case of Bud.

I stood there and watched Stanley leave, then looked down at Bryan’s contraption.

Yes, I thought.

People would do almost anything to get the pain out of them.

June 9, 2014

Praying in all circumstances

I still don’t know what happened or how, or even what everyone did in the few seconds it took for the screaming to start. All I know is that one minute I was playing with the dog, and the next minute the dog was howling.

I still don’t know what happened or how, or even what everyone did in the few seconds it took for the screaming to start. All I know is that one minute I was playing with the dog, and the next minute the dog was howling.

Lucy is her name. Half beagle, half dachshund, wholly sweet. Three months old. Rescue dog. Everybody loves Lucy, and I mean everybody. If you’d see her, you’d love her too.

Playful little thing, always fetching and running and wagging, and that’s what the two of us were doing the other day when it happened. And again, I still don’t know what “it” was. Or “happened,” for that matter. There was a tennis ball and then I turned my back. Then the howling.

Piercing, blood-curdling howling. A howling like you’ve never heard in your life.

Everyone came running from all corners of the house. They freaked. I freaked. My daughter was screaming, my wife, my son, and they didn’t know why. Lucy was screaming, too, and the look on her face was one that told me she didn’t know why she was screaming either but it HURT, something on her HURT, and then all of a sudden Lucy could no longer walk.

Friday evening, this was. Six o’clock or so. Vet closed for the weekend. There was an emergency vet clinic in a town about thirty minutes away.

What to do? That was the question. A million things run through your mind in times like this (not the least of which, to me anyway, was that having a puppy in the house isn’t really all that different from having a baby in the house, and that’s something I’d never considered), but it was hard for me to think—hard for anyone—because everyone was still freaking out.

My daughter was crying now. Lucy was still crying. My wife the teacher was trying to keep everyone calm but everyone wouldn’t be calm, my daughter and me especially, and my son, my boy, just stood there and started praying.

PRAYING.

Now, I’m all for praying. Every morning, I pray. Every meal, I pray. I pray coming home from work and I pray before going to sleep at night. God and I, we talk. A lot.

And yet I am religiously-minded enough to understand there are times when praying should be set aside. There’s a time to talk and a time to DO, and this is a time to DO. No talking. And so my wife is finding the phone number to the clinic and my daughter is trying to calm Lucy and Lucy is still screaming because she can’t walk and I’m slowly having a breakdown, but my son now has both of his hands on Lucy’s back and he’s calling down the Spirit.

Crazy, right? I mean, I can’t be the only one who thinks this is crazy.

The phone number is found. The call is made. I think my daughter is about to swallow her own tongue. Lucy’s right hind leg is drawn all the way up to her stomach, turning her into a furry stool. Whatever black hair is left in my beard is slowly turning white, and I think my son is starting to speak in tongues.

To the best of my recollection, that’s what happened.

Long story short, we made it to the vet. It was nearly ten o’clock that night when we brought Lucy out of the exam room. We paid and spoke briefly with a heart-stricken man whose Pit Bull had been brought in with “woman problems.”

Lucy’s fine. Not even the vet could really figure out what had happened, but by the next morning our little pup was running around chasing tennis balls again.

My son’s convinced it was all the praying. That’s what made Lucy better. And thought none of us can really know for sure, I have it in my head now that he’s right. It was the praying.

“Ain’t supposed to just talk to God when things are quiet,” he told me. “You gotta talk to God when things are loud, too.”

June 5, 2014

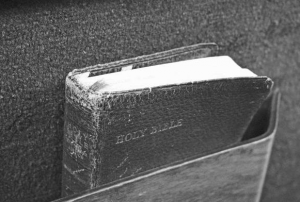

The Father’s Love

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

My grandfather gave me my first Bible. I was four. He called me into the small office he had just off the kitchen and sat me down like I’d done something wrong (which I had, in fact—many, many somethings, and I didn’t know which one I’d been caught doing or how), then removed a small, wrapped rectangle from his desk drawer. “Yours,” he told me. “I want you to have it.”It was one of those small New Testaments with the Psalms and Proverbs in the back, the kind you still see passed out by the Gideons, of which my grandfather was one. I remember carrying that bible around with me everywhere. I’d sit and leaf through the pages, run my fingers over the words. I even underlined a few verses here and there, like I’d seen my grandmother do in her worn King James. I couldn’t read a word of it, of course. But I liked to pretend I could, and I couldn’t wait until I could for real.

I still have that old Bible. The back cover is gone and the pages are thinning and yellowed, but you can still see my name in pencil on the first page and “Love, Granddaddy” written beneath. I don’t use it anymore. It stays atop one of my bookcases, there more as a relic to admire than something to take down and handle. The one I use daily and haul back and forth to church is not unlike the one my grandmother owned, old and worn. I like it, though. Someone once told me a Bible in tatters is indicative of a life that is not.

Still like to write in my Bible, too. And underline. Leaf through the pages of mine and you’ll find marks and notes many years old, all of which form a kind of spiritual timeline for my life. I’ll read a note scrawled in the margin or find a circled verse, and I can tell you exactly what was happening in my life at the time. I can tell you what I was going through or wrestling with. I can tell you if I was stumbling or flying.

I have one verse that’s been highlighted and underlined and noted more than any other. So much, in fact, that I now have to squint and raise the page close to be able to read it.

Romans 8: 38-39:

“For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor any other created thing, will be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

In the thirty years I’ve owned that Bible, I’ve circled and commented on nearly every one of those forty-nine words. Because I needed them, you see. There was a time when I needed to know that nothing could separate me from God’s love. There was another time when I needed to know it didn’t matter how high I was or how low, another when I needed to know I didn’t need to mourn my past, fear my present. Not even death was an end—there was a time when I needed to know that as well.

It’s the one verse I’ve gone to again and again. It has sustained me. It sustains me still.

I came across that verse this morning and paused to read it again. And I noticed something that had escaped me all this while, something I believe only time and experience has allowed me to see. One word in those two verses had been left unmarked, almost as if I’d never needed it or really understood why it was there.

That word was “life.”

Life can’t keep me from God’s love, either.

I’d never really considered that, never really understood what it meant. Until this morning, at any rate. Like I said—time and experience.

I’d presume you and I aren’t all that different. We’ve both been around enough. Done enough. Lived enough. We know to a certain degree what’s waiting when we get up every morning—the slog to work, the slog back home, the bills waiting in the mail and the people screaming on the TV that the world’s going to hell and we’d all better hang on. There are kids to worry about and retirement, and there’s that bum knee or the lump we feel or the arthritis settling in that lets us know we’re fast approaching the downward slope of life. There’s busted pipes and the clunking sound in the car and the dog to take to the vet. There’s dreams we once had and maybe still do, and there’s a sense of guilt and anger that maybe—maybe—what we are now is all we’ll ever be.

There’s life.

And you know what? All that stuff I just wrote can be as tiring and stressful and soul-crushing as any tragedy. I know people who have lost their faith through war or divorce or the death of a loved one. I know far more who have lost their faith by simply living day after day and year after year, trudging through the muck and the mire of life.

I underlined that word in my Bible this morning. Drew a box around it. To me, it’s the most important part of that verse now. Because God is determined not to keep death and the past and the future between Him and me. He won’t let life do it, either.

June 3, 2014

Spiritual Whitespace

I don’t really remember the first time I came upon Bonnie Gray. It was early on, just after the two of us began blogging. The two of us couldn’t be more unlike as far as where and how we were raised and how we came up in the world. We did, however, share a single common goal—to be published authors.

I don’t really remember the first time I came upon Bonnie Gray. It was early on, just after the two of us began blogging. The two of us couldn’t be more unlike as far as where and how we were raised and how we came up in the world. We did, however, share a single common goal—to be published authors.

Bonnie’s dream came true not long ago when she signed her first book contract. The elation and sense of accomplishment that comes out of something like can’t really be described. It has to be lived. And yet all that joy and fulfillment of purpose is usually a fleeting thing, because on the heels of that can come a dark night of the soul to which no writer is fully prepared.

That’s what happened to Bonnie. Her dark night came the moment she sat down to begin writing her book, and what followed was a descent into profound anxiety and a journey to discover painful childhood memories locked deep inside her.

The result is her new book, Finding Spiritual Whitespace, which is out this week. Bonnie’s journey to healing from her past culminated in the insight that what we all need isn’t more, it’s less. It’s whitespace—the unmarked part of a page, the untouched portion of a painting. The emptiness left for Christ to fill.

I read Bonnie’s book in one sitting, a testament to the style of her writing and the deeply honest stories she tells. I finished understanding not for the first time that we often don’t have the answers as to why we struggle through so much of life, but sometimes we come to understand that our journey through darkness exists so we can help others through theirs.

You can purchase Finding Spiritual Whitespace through Amazon here. It’ll stir you. Promise.