Billy Coffey's Blog, page 28

August 13, 2013

Signs of a season change

WARNING!!! DO NOT OPEN THIS DRAWER UNLESS YOU ARE MOMMY. ANYONE WHO OPENS THIS DRAWER WHO IS NOT MOMMY WILL BE IN TROUBLE!!!

WARNING!!! DO NOT OPEN THIS DRAWER UNLESS YOU ARE MOMMY. ANYONE WHO OPENS THIS DRAWER WHO IS NOT MOMMY WILL BE IN TROUBLE!!!

Taped to the top left drawer of my daughter’s dresser. Saw it last night when I checked to make sure she was sleeping. Written in yellow highlighter, in all caps, and with a total of six exclamation points.

It seemed her point was clear enough. Do not open. Unless you’re Mommy. Off limits to both her father and her little brother. The latter was understandable—big sisters do not want their little brothers going through their things. But the latter was me, and my daughter was not in the habit of hiding things from her daddy.

So I was faced with a conundrum that felt more deep and profound than to merely look or not. It was more than that. It was to invade my child’s privacy or make sure she didn’t have anything in her drawer she wasn’t supposed to. Not likely (not likely at all, really), since she’s never been one to do something she shouldn’t. But still, it ate at me.

I would like to say here that I did not look then. I left the note untouched, tucked the blankets around my little girl, and went to bed. I tossed. I turned. I thought and wondered.

Given what the piece of paper said, I felt sure my wife knew what was in my daughter’s dresser drawer. She was asleep, though. I couldn’t wake her. That doesn’t mean my conscience prohibited it—by then I’d realized I would never be able to get to sleep until I knew, and by then I’d convinced myself whatever my daughter was hiding had to be important—but that I literally could not wake her. I shook her and called her name and kicked her under the covers.

My wife didn’t move. Teachers are often tired.

Which meant there was only one thing left to do.

So I got out of bed. Walked from our room into my daughter’s, checked to make sure she was still asleep, and ignored the sign on her dresser drawer.

The small lamp on her nightstand offered just enough light to turn black to shadow. I grabbed the first thing I felt, turned around, and held it up to the light.

A sock. Tried again. Another sock.

I rifled through what I could, looking for…well, I didn’t know what I was looking for. Something other than socks, I guess. I pulled out T shirts, old birthday cards, some chapstick, and a misplaced Barbie.

The something stuffed on the bottom in the back of the drawer felt like neither sock nor T shirt. I pulled it out, turned, held it up to the light, and nearly fell down.

Sweet fancy Moses, Holy Mother of God, Matthew Mark Luke and John, it was a bra.

For my daughter. My eleven-year-old daughter.

I dropped it. Thankfully, it was little more than a sliver of cotton that weighed all of three ounces. It made no sound on the carpet. I stood there with it in front of me, leering at me, taunting, saying, “Ha! Didn’t expect that, did you?” to me. I looked from It to her, the little girl sleeping in the bed.

I wondered what had happened and how it had happened.

Sometime—recently or not, though I hoped it had been moments and not months—a season had changed in my daughter’s life. We gauge our passing through this life by years. Seasons would be better. Because sometimes we languish in inner winters, sometimes we burst forth to a new springlife, sometimes we rest in the sunshine, and sometimes we fall.

Years do not matter. Seasons do.

It was now springtime for my daughter. I prayed that didn’t mean I was to suffer winter.

I picked up the bra and settled it back into the drawer, mindful to next time pay heed to the warnings she posted. I gathered the covers tight around her. She opened sleepy eyes and smiled at my sight.

“Hey Daddy,” she said.

“Hey back.”

“What are you doing?”

“Checking on you.”

She smiled again. “I like it when you check on me.”

I kissed her head and said, “I’ll always check on you.”

And I will. No matter the season.

August 8, 2013

Three people

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Though my workdays are normally filled with all the commotion and stress that a thousand college students can generate, the days between June and mid-August are mine alone to enjoy. It’s only slightly ironic and more than a little unexpected to me that summer break means even more to me now than it did when I was in school, but it’s true. Never let it be said that a little separation between yourself and others is a bad thing.

Despite the fact I have plenty to keep myself busy, I also have plenty of time to myself. Time that will be spent writing. Which is what I tried to do just a bit ago, and with unfortunate results.

I had just started typing when the buzzing began. First in one ear and then the other and then back again. My right thumb punched downward on the space bar and trampolined my hand upward, waving through the air.

“Stupid fly,” I muttered.

The buzzing returned, and this time the fly actually bounced itself off my head. More waving. More missing. Then the creature circled around and landed right on top of my computer screen, staring at me.

Black, juicy one. Hairy legs and monstrous eyes. And a wingspan that seemed almost unnatural.

Where it had been and how it had gotten into my office escaped me, and I really didn’t care. All that mattered was that I went back to work. I shooed it away and went back to my typing.

SMACK!

Against my head again.

I wheeled my chair around and swiped at it, missing the fly but not the stack of books on the opposite table, all of which tumbled to the floor.

SMACK!

“Dang it, you come back HERE!,” I yelled. “I’m gonna KILL YOU!!”

I roamed around my office for the next five minutes. Found nothing, of course. No buzzing, and no kamikaze attacks. So I sat back down and started writing. Four paragraphs later,

SMACK!

And then after that SMACK!, it stuck. To my head. And I swear, I swear to you, that fly made a beeline toward my ear. I was convinced it was going to burrow in and eat my brain.

I jumped up, slapping at my head and flailing my arms in every direction. The fly somehow managed to retreat back to whatever hell it came from and left me alone. For the moment.

But I knew it would be back. Oh yes, I knew. Which is why I put on my cowboy hat (to prevent any future burrowing) and started to fake type.

Two minutes later, buzzing again. And just at that moment I transformed myself into some strange Jedi/Mr. Miyagi/redneck hybrid, sliced through the air with an open palm—

—and connected.

The fly tumbled backward through the air and crashed against the far wall.

That was five minutes ago.

I’m back at my computer now. Order has been restored. But now I’m suffering through the fits and stops of trying to write, because every sentence I’m trying to type is interrupted by more buzzing.

The fly is still alive, though just barely.

It managed to right itself a bit ago by flopping back onto its legs, but it can’t do much else. Every attempt to take to flight has been both paltry and meaningless.

And now I feel guilty.

There are certain religious adherents who would say I sinned a bit ago, that every creature is worthy of respect and life and that by denying those things to them I deny them to myself. Others would say the sin was letting both haste and anger lead me to do something I now regret.

I suppose a sort of atonement is called for now, though I’m not sure what the proper course of action is. Should I walk over and euthanize it with my boot. Or should I try to nurse it back to health with small tweezers and bits of rancid meat? I’m not sure.

I am sure of this, though. We can try to model our lives to the Good, to walk straight and never wander, to be our very best selves. And sometimes that will work. But who we truly are deep down in our broken souls will always be there, ready in an instant to bare its teeth.

That is, I suppose, why we are all three people in one—there’s the person we want to be, the person we are, and the person who must daily choose which way to lean.

August 5, 2013

Beautiful

image courtesy of google images.

An hour ago:

“What are you doing?”

My daughter is standing on her bed and facing the mirror atop her dresser. She’s not looking at herself, not performing the sort of quick once-over females tend to do before going to town. Instead, she’s studying. Closely.

“I’m looking at myself,” she says.

“Why are you standing on the bed?”

“Because if I stand on the floor I can only see half. I want to see the whole thing.”

I offer the sort of nod I often give to females. The sort that says I don’t understand you, but I’m going to act like I do.

“Okay,” I tell her, “but hurry up. We’re ready to leave.”

She continues to scrutinize and then asks, “Daddy, can I ask you something?”

“Can you ask it in the truck?”

“Can you answer it here?”

“Okay, fine.”

She tilts her head to the side and lets her blond hair spill down over her shoulder. My daughter never used to pay attention to mirrors. Now she can’t pass by one without taking a peek to make sure nothing needs tucking or straightening or smoothing.

“Am I pretty?” she asks.

“Very much so,” I say.

She tilts her head to the other side. “Do you think Hannah Montana is pretty?”

“No.”

“Taylor Swift?”

“No.”

“Carrie Underwood?”

“No.”

“Well,” she says, “I think they’re beautiful.”

“Can we go to town now?” I ask her.

She hops off the bed and takes my hand. “What makes them beautiful, Daddy?” she asks.

“Well, since I don’t think they’re beautiful, I can’t really answer that question.”

“I don’t think I’m beautiful,” she says.

“Why’s that?”

“Because there’s a lot wrong with me.”

An hour later:

We’ve made it to town. My daughter managed to sneak away and into the truck before I could talk to her more. And heading to town with family in tow is not the proper time for such a conversation. So I’m currently left to stew and walk the aisles of the local Target, trying to decide how I’m going to finish the conversation her and I had begun.

At eleven, my daughter is on the cusp of that age when appearance begins to matter more than it once did. I don’t think that’s really a bad thing, but it is confusing to her. She thinks everything is beautiful—sunrises, sunsets, and the puffy white seedlings atop dandelions come to mind—but she secretly fears she is not. I can understand. It’s hard to compete with sunrises, sunsets, and dandelions.

And when it comes to things that are beautiful in any obvious way, she still refuses to call them ugly. To her, ugly is just a word people use for things where the beautiful chooses to remain hidden.

That’s the way I want to keep it with her. Because that is nearest to the truth.

This is also the truth—there is a lot wrong with her. Behind that blond hair and those blue eyes is a little girl who has gone through much. Too much, if you ask me.

I see the way she wears long sleeves and pants in the warm weather to hide the bruises that can pop up after her insulin shots. I see the way she talks to friends with her hands in a fist so they won’t see the pock marks left on her fingers from her sugar checks.

It’s bad enough to have a disease, she’s told me. But when you believe that disease makes you ugly, it’s worse.

I don’t blame her for thinking that way. I think there are a lot of people—older, smarter people—who do the same. But what she sees as ugliness I see as a means of becoming beautiful. Her disease has given her a compassion and an understanding I could never have.

I remember recently reading about the Miss Navajo Nation beauty pageant. Held every year. The contestants do the sort of usual things you would find in any pageant anywhere. They dress up and show their talents and talk about what they would do if they held the title.

But there is no swimsuit competition. In its place is a demonstration of some traditional Navajo skill, which can be anything from weaving to butchering a sheep.

I like that.

Because beauty isn’t simply about looking pretty and speaking well. True beauty is useful. It draws attention not to how good you look, but what good you can do.

That’s what I’m going to tell my daughter when we get home.

I’ll let you know how it goes.

August 2, 2013

Handling the remote

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Sexist I’m not, though I must admit I believe there are a few things men have a firmer handle on than women. Just a few, mind you.

Chief among these is the proper handling of the television remote control. This is most likely due to an almost childlike ignorance concerning its proper function on the part of the female. The remote is not used to simply turn the channel or adjust the volume. It’s purpose is much more intricate–to obtain an overall grasp of station selections, striking an elegant balance between quality viewing and commercial evasion. Or, in more simplistic terms, to channel surf.

My wife has long abandoned any hope of holding the remote control. Not that I do not trust her with it. But watching her use it is painful to me in the way that a composer would be pained by watching a hillbilly use a Stradivarius. It is a skill, the handling of a remote. Something that cannot be taught but must be inborn.

Over the past few weeks, however, an insurrection has begun over our family’s remote control. One led not by my wife. Not even by my son.

By my daughter.

It began innocently enough. I walked into the living room one evening and found her on the sofa and the remote on the ottoman. During a commercial break on her favorite cartoon, I decided to see what else was on. When I reached for the remote, however, I found a hand already there. Hers.

The ensuing standoff was both temporary and bloodless, and my Alpha role within the family remained intact. But as these remote control battles increased in frequency, I began to lose a bit of face. The last one, yesterday, ended in a tickle fight that was only broken up with my son whopping me with a pillow.

I’ll be honest here. I really don’t understand the whole remote control thing. I don’t really know why it must be in my hands and no one else’s. I am not a callous snob. I will gladly watch what my family wants. But I must be the one to turn the channel.

True, there is a certain amount of power involved in the remote. Those buttons are alluring. I have a control over the television that is not offered in my life. Possibilities that are difficult at least and impossible at best.

Zoom, for instance. With a push of a button, my remote will enlarge a certain area of my screen and bring greater detail to the larger picture. The ramifications are enormous. I have outwitted both Shawn Spencer on Psych and the dude in the vest on The Mentalist by the careful manipulation of that button. I don’t miss anything. Which is quite unlike my own life, in which I miss too much.

And there is the Swap button. A wonderful feature that lets me instantly trade what I’m seeing for something else. Easy on my remote. Harder in my reality.

The Exit button is even more handy, enabling me to quickly escape from a screen I have no idea how I managed to get to. The Exit button works wonders for me when it comes to the television. Not in life, though. Most of the time I have to find my own way out of all the self-inflicted confusion.

I would also like to have Pause, Rewind, and Fast Forward buttons in my life, just so I could take a break or try something again or skip over the parts I don’t like.

Play, too, would be a necessary function. I would like more play in my life.

That, I think, is why I’m so passionate about the remote. And if you’re honest, I don’t think you can blame me. Because no matter who you are, we all want a little more control over our lives.

I will say, however, that there I have one function in my life that is much better than its counterpart on my remote control: the Guide button. A push of that button and I know how to navigate around on my television. Handy.

But handier is the Guide in my life, the One who can navigate me through all of those parts in my life I would like to skip over or redo or exit. The One who can help me zoom in on what needs to be seen.

And Who can help me swap earth for heaven.

July 29, 2013

A world of possibility

image courtesy of photobucket.com

The book is about magic, which ranks high on my list. But it’s really about the secret behind all those magic tricks that enchant me, and that ranks pretty low. It was a gift from a distant relative, given with the best of intentions. Still, it missed the mark by quite a wide margin.

It sits here on the table beside me, shiny and new, several of its pages still sticking together from lack of handling. If I turn the book over I can still see a section of wrapping paper, evidence that I got only as far as taking at look at the cover before thanking the giver for the thoughtful gift and setting it aside. To him (or her), it was the perfect present. I like books, and I like magic.

But I’m not reading it. No way.

I say I like magic, but that’s not quite the correct word. I love magic. Can’t do it of course, unless you count marveling a bunch of preschoolers with the old Hide Something Behind Your Back trick. But I love to see it done. Professionally or otherwise.

It doesn’t have to be anything so extravagant as to involve tigers or disappearing airplanes. In fact, the smaller the magic the more it appeals to me. I love the agility, the misdirection. I love the showmanship. Yes, it’s all just a trick. All an elaborate sham of skillful legerdemain. I know this going in. And it matters not.

All that matters to me is that I remain ignorant of the means by which that magic is done. I don’t want to know those secrets of where the rabbit is before it’s pulled out of the hat or how the buxom brunette is put together after being sawn into. Knowing would rob me of my wonder. And that’s exactly what magic is all about.

Wonder.

I’ve spent much of my life searching for answers to the questions that preyed on my mind. Big questions. Important ones. Like how can I find love and why does everyone have to hurt and why God sometimes just doesn’t seem to care and what does it all mean anyway. I talked to giants of both faith and the mind, read countless books, prayed and meditated. And do you know what I got out of that?

Not much.

I did acquire a head full of knowledge and theories, many of which contradicted either one another or reality. But that was okay at the time, because I believed I had much more than when I began. I had facts. And when it came to understanding this world and the life we live in it, facts seemed to be the most important things I could possess.

Unfortunately, those facts didn’t carry me far. They were a weighty spade to plunge into the hardpan of my life, cracking the surface of my doubts and questions to water that arid ground with the elixir of truth.

But those questions did not yield. The head of the spade held true, but the handle, that part where flesh met iron, could not hold.

I had learned that tears were drops of salty fluid secreted by the lacrimal gland to lubricate the eyeball, but that did little to explain why I shed so many of them. That death was to stop living. I learned, too, that a rainbow was formed by the refraction, reflection, and dispersion of light in rain or fog. Those were the facts. But those facts did little to explain why I shed so many tears and why people had to die. And somehow knowing the facts behind a rainbow made it less beautiful to me, as if it were more of a process and less of a miracle.

Sometimes ignorance really is bliss, and there’s nothing wrong with that. We don’t have to know everything. Our task is the search for truth, yes. But the truth is that there are some things we are simply not supposed to understand. We’re not supposed to know everything. And because of that there is beauty to our unanswered questions and a sweet mystery to our doubts.

There is magic in this world. I’m convinced of it. It flows not from the hands of a skillful conjurer, but from us. From our very being. We are surrounded by every day by enchantment so thick we almost must brush it from our faces.

I won’t return this book. It will remain unopened but in a predominant place here on my table. It will be a reminder that knowing with the head is much different than knowing with the heart.

And that given the choice, I will take possibility over fact any day.

July 25, 2013

In praise of the inbred hick

image courtesy of photobucket.com

There are better things to be called than “an inbred hick,” and I had been called worse by many, but I had to admire the originality. And I wasn’t mad. The phrase was uttered with a sense of good-natured mockery common among friends in general and mine specifically. Especially the one who was not only a liberal, but also a Red Sox fan. I never said my friends were perfect.

This friend’s name? Dan. A truly brilliant man despite the fact I would never admit it to his face. Chair of the Asian Studies department at the college. Prolific author and lecturer. World traveler. Highbrow. All of which paints a pretty stark contrast to me. My only chair is the one in the living room, I am prolific only at spitting and shooting a bow, most of my travels are on dirt roads, and I am the very definition of lowbrow.

We have our differences, to be sure. And whenever we happen to bump into each other, we spend most of our time arguing over whose differences are right.

Like yesterday, for instance.

Dan brought me a souvenir from his latest trip to Japan—a fan with “Hanshin Tigers” printed on the front, along with a pretty ferocious looking cat.

“You should go with me one time,” he said after recapping his adventures. “Japanese baseball is great, and the Tigers have a good team this year. You need to see the world. You’re stuck here in this valley missing everything.”

“You’re only stuck if you can’t move,” I said, “I just don’t want to. And I’m not missing much. The world’s a crazy place. At least around here the crazy’s familiar.”

“There’s nothing here,” he said. “It’s all out there. The world’s passing you by. Your family’s been here how long?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I think we came with the Valley.”

“Exactly. Generations. As long as people can remember.”

“And that’s bad how?”

“You’re the product of centuries of people who refused to better themselves. Your life is no different than your great-grandfather’s and his great-grandfather’s.”

“So?” I asked.

“So you’re just an inbred hick. You could make yourself into a lot better person.”

The thought of making myself into a better person had never really crossed my mind, mostly because I’d always been pretty content with who I was. Then again, I’d never considered myself an inbred hick.

But my family has occupied this valley and the mountains surrounding it for centuries. Staying put in one place for so long tends to give you a sense of belonging. Of home. And though I would trade my mountains for the ocean any day, this place would always be home. There are a lot of my kin buried here in the Blue Ridge. I could wander away from those bones, but not for very long and not for very far.

So the inbred thing? True.

As for the “hick” part of that little insult, I’d have to say that was something Dan and his fellow urbanites just couldn’t understand. They’d never lived in the sticks, never spent much time with country folk, and so allowed their stereotypes to rule them.

Then again, all stereotypes are grounded in some semblance of truth.

It’s true, for instance, that one of my best Christmas presents last year was a bag of deer jerky and a jar of peach moonshine. And yes, some country folk live in trailers. By and large, “dressing up” means trading our faded jeans for dark ones. We are not generally well-educated. We do hunt and fish and ride four-wheelers. We live vicariously through Ric Flair and consider “Freebird” the real national anthem.

True. All true.

But there is more beneath the surface to life in the country. A lot.

Because to us, a trailer full of love is better than a castle full of discord.

And we’re not nearly as impressed with the clothes a person wears as we are with the person wearing the clothes.

We might not be able to split the atom, but we know what means much in life and what doesn’t.

We hunt and fish and grow our own groceries because food straight out of the dirt and the woods, sweetened with sweat and labor, tastes a lot better than what you can get at the store.

Our churches aren’t big, but they’re full. Our words are few, but they’re meaningful. We don’t want more of this world. We want less.

We are plain and simple people. People who will go hungry before letting our neighbors starve, drop whatever we’re doing to help a friend, and roam among the wild places to get a better glimpse of God.

The best people. My people.

Inbred hicks? Absolutely. Who could possibly want to be more?

July 22, 2013

Knowing how to pray

image courtesy of photobucket.com

A friend recently confessed that not only had he never prayed, he had never found an adequate opportunity to do so. Why bother, he asked, to resort to empty words to a God who is at best noncommittal and at worst uncaring?

I gave him an appreciative nod. There had been times in my life when I suspected God to be both, but in the end the opposite had always held to be true. But his words struck me. Prayer was much a part of my life even in my darkest days. Not praying, no matter how far the distance between myself and God, was never an option.

I’d always assumed there were many in the world who never lifted their voice to heaven. I’d just never known one.

I figured I prayed about seven times a day. Not bad, really, until I started thinking about some of the things I prayed both for and about. Asking for God to watch over my loved ones is a lot different than asking Him to let the Yanks win and the Sox lose. I asked for both over the weekend.

And while asking Him to make my headache go away is maybe an okay thing, asking Him to give the person who caused my headache sudden and uncontrollable diarrhea probably wasn’t.

It all got me thinking not only about how and when I pray, but how and when others do the same. Prayer is something many of us take for granted. I doubt we pause enough to consider the gravity of actually speaking to the Creator of the universe.

Prayer is serious stuff. Fascinating, too. Nothing says more about us than how we talk to God. So I decided to take last Sunday and observe both family and friends in a sort of super secret prayer survey. I wanted to know who got it just right, who didn’t quite, and why.

Church seemed like a logical starting point. Lots of people pray in church. I listened to the Sunday School teacher, the pastor, and an usher pray with both an eloquence and spirit that I could aspire to but never quite accomplish. Eloquence has never been my strong suit. Me often don’t talk like that pretty.

Lunch with my wife’s family, however, seemed more promising. There are a lot of things country folk can do better than others, and talking to God is among them. Country prayers are not as flowery as church prayers. There are plenty of ain’ts and gonnas. It’s not praying, it’s prayin’. Big difference.

So we prayed for the hands that cooked the food and the ground that grew it. For the rain that would make the corn grow and the closeness of family. That prayer was nice. Homey. But it still wasn’t quite…right. Something was missing.

Bedtime found my family gathered around my daughter’s bed, knees to floor. And though I normally assume the traditional pose of head bowed and hands folded, I cheated that night. I kept my eyes and ears open as my children prayed. Together.

“Thanks, Jesus,” my son said, “for all the cool stuff You showed me today.”

“And,” said my daughter, “for the green grass. It’s my favorite color.”

“Thanks for the macaroni, because I love macaroni,” added my son.

“I didn’t like the broccoli,” my daughter said. “Can you please do something about that?”

“You made pretty clouds tonight.”

“I love you, God.”

“I love you too, God.”

“We both love you.”

Then, together: “Amen.”

I walked outside a while later to make sure the stars were still there and say goodnight to God. I’ve always liked praying outside. For some strange reason, I’ve always thought my words could go through a ceiling of clouds much easier than a ceiling of plaster.

I’ll be honest. Prayer has always been a little confusing to me. Like the people at church, I’ve tried to be eloquent and flowery. Like the people I shared lunch with, I’ve tried to be folksy and homey. And like my children, I’ve tried to keep things simple.

It isn’t always easy to put thoughts and feelings to words, no matter to whom we’re talking.

I guess in the end it isn’t so much what we say to God as it is the heart with which it’s said. What we can’t explain, He knows. What we can’t say quite right He knows exactly.

And sometimes, many times, a prayer needs no words at all.

Which is why that night, there beneath the stars, I simply looked to heaven and smiled.

July 18, 2013

Useless information

It’s somewhat alarming to think about how many things I forget during the course of a normal day. The exact number eludes me; I forget how many things I’ve forgotten.

It’s somewhat alarming to think about how many things I forget during the course of a normal day. The exact number eludes me; I forget how many things I’ve forgotten.

There are little things like forgetting where I’ve put my keys and wallet, and also big things like where I’ve put my children. I’ve forgotten appointments, to eat, to set my alarm, and, I noticed today, the fact that the oil needs to be changed in my truck.

The reasons for this may be many or one, depending upon whom I ask. My wife says it’s because I’m too tired, my friends say I’m too busy. Standard excuses for everyone with a short attention span. My mother, however, offered her own reason in her typically loving way:

“Your head’s too full of useless stuff,” she said. “There’s no room for things that matter.”

I thought about that and had to agree that what she said was at least partly right. I wasn’t sure if it were possible to have so much in my head that nothing else could get in, but I did have a lot of seemingly useless stuff stuck in there.

Stuff like the fact that a dragonfly can eat its own weight in thirty minutes. Or that Hollywood was founded by a man who wanted to build a community based on his conservative religious principles. Couvade is a custom in which a father simulates the symptoms of childbirth. Einstein went his entire life without ever wearing a pair of socks. I could go on.

Where I’ve managed to scrape up such tidbits of uselessness is beyond me. So is the manner by which I can remember that John Milton went blind because he read too late at night but not the name of someone I see at work every day.

The fact that I may simply be absent-minded occurred to me. It’s a distinct possibility. I come from a long line of absent-minded people. But that seems like a poor excuse in itself, and I keep thinking about what my mother said to me.

There’s little doubt that we all fill our lives with things that don’t matter, thereby sacrificing some of the things that do. Worry robs our faith, doubt our hope, and discord our love. But is that true for knowledge? Can we know too much for our own good?

Some people think so. I have friends who believe that faith is all they need, that thinking has done nothing but bring the world a whole lot of trouble. Communism, moral relativism, and Keeping up with the Kardashians wouldn’t exist if someone hadn’t thought them up and ruined all of our lives. Sometimes I think that’s true, especially with Keeping up with the Kardashians.

Faith is pretty much the most important thing a person can have. I also think having as much knowledge as possible easily breaks the top three. Because despite what everyone says, ignorance is not bliss. It’s more like a prison cell with walls of our own making.

Of all the inborn traits God sees fit to give us, few are exercised less than our curiosity. Spending some time with the nearest child will convince you that we’re all born with a probing mind. But that somehow gets lost as we get older. We all are tempted to reach a point where we just don’t care to know anything else. We already know enough about the world to realize it’s all spiraling downward. Why pile it on?

I get that, I really do. There are plenty of things I would rather not know, things that would keep my life chugging along rather nicely if they weren’t stuck on one giant playback loop in my brain.

But then there’s this to consider—our world really is a wonderful place. Flawed, yes. And a bit ugly in some places. But it’s also amazing and inspiring and so utterly almost-perfect.

The truth? I want to know everything. Even the stupid stuff. After all these years, I’m still curious. I still want to know. Because I’ve found that the more I can know about God’s world and the people who inhabit it, the more I can know about God and me. If that keeps me from checking my mail every once in a while or not realizing the truck’s almost out of gas, then so be it.

I think we would all be a little better off if we cracked a book every once in a while. There’s too much ignorance in this world. Life, like music, must contain several parts equally. There must be melody and beat. And there must be heart and head. That’s how we dance through our days. And God is a musician at heart.

Just ask the common housefly. Whose wings, by the way, hum in the key of F.

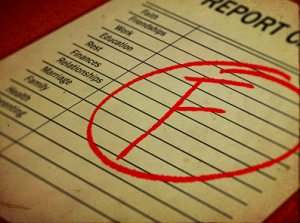

July 15, 2013

Failing everything

image courtesy of google images.

Part of my job entails keeping up with the comings and goings of about one thousand college students. All have arrived at the doorstep of adult responsibility. Walking through, they find, is not an option. How they walk through, however, is entirely up to them. Some glide. Others stumble.

Students are constantly arriving, eager to fill their hungry minds and lavish themselves in the newfound freedom that college life offers. Unfortunately, some find that those freedoms can lead to the sort of trouble that leads them back home.

The status of these students is cataloged and recorded and then shared with various departments by way of email. Very businesslike, these emails. Concise and emotionless. But they are to me snapshots of lives in transition.

One such message came across the computer yesterday. The usual fare—student’s name and identification number, and her status. But then there was this:

She will not be returning and is withdrawing.

She failed everything.

As I said, businesslike. Concise and emotionless.

I’ve always had a problem with brevity. I have a habit of explaining a small notion with a lot of words. Which I guess is why that particular email struck me.

Here was three months of a person’s life, ninety days of someone’s experiences and feelings and thoughts, summed up in three words:

She failed everything.

Though I didn’t know this person, I could sympathize. I’d been there. Many times. I knew what it was like to begin something with the best of intentions and an abundance of hope, only to see everything fall apart. I knew what it felt like to realize no matter how hard you try, you sometimes just can’t. Can’t win. Can’t succeed. Can’t make it.

I knew what it felt like to fail. Everything.

When my kids were born, I wanted to be the perfect father. Always attentive. Never frustrated. Nurturing. Understanding. And I was. At first, anyway. But things like colic and sleeplessness and messy diapers can wear on a father. They can make a father a little inattentive sometimes, sometimes not so nurturing, and very frustrated. So I failed at being the perfect father.

Same goes for being the perfect husband, by the way. I failed even more at that.

And I had the perfect dream, too. What better life is there than that of a writer? But no, that one hasn’t gone as expected. Failure again.

At various times, struggling through each of those things, I’ve done exactly what that young girl in the email did. I withdrew. Not from college. From life. I gave up. Surrendered. Why bother, I thought.

But I learned something. I learned there’s sometimes a big difference between what we try to do and what we actually accomplish. And that many times we don’t succeed because there’s an equally big difference between what we want and what God wants.

I learned, too, that failure is never the end. It can be, of course. We can withdraw and not return, as that student will do. Or we can learn that it is only when we fail that we truly draw near to God. Those are the times when we can better understand that our prayers must sometimes be returned to us for revision. Not make me this or give me that, but Thy will be done.

I’ve failed everything. Many times.

And I’ve also been remade.

I may not have made myself the perfect father, but God has made me a good dad.

I may not have become the perfect husband, but God has shown me how to be a soul mate.

I may not write for me, but I do write for people.

Failure has not been my enemy. Failure has been my salvation.

Our lives have broken places not so we can surrender to life, but so we can surrender to God. Our failures can hollow us, yes. But only so He may fill that emptiness with joy.

July 12, 2013

Rediscovering the Rules

It began a few years ago with a simple conversation between one college softball player and one groundskeeper. I’m not sure who first said what. All I know is at some point one said something about being a much better ballplayer than the other, which was taken as an insult, which resulted in more insults, which resulted in the first ever softball game between the girls fast-pitch team and the staff.

It began a few years ago with a simple conversation between one college softball player and one groundskeeper. I’m not sure who first said what. All I know is at some point one said something about being a much better ballplayer than the other, which was taken as an insult, which resulted in more insults, which resulted in the first ever softball game between the girls fast-pitch team and the staff.

The games are always interesting. There is an extraordinary amount of fanfare involved, all of which can be boiled down to one word—pride. That’s what fuels these games. It’s not just pros against Joes, it’s the experience of age versus the cockiness of youth. Both teams are out to prove something, whether it be that that a bunch of old men can still kick it up a notch when needed or that the gals can hit and throw and run just as good—better, even—than the guys.

So while there is plenty in the way of friendly trash talking, there is also an undeniable seriousness beneath. My team doesn’t want to be beaten by a bunch of girls. Their team doesn’t want to be beaten by a bunch of groundskeepers, a few office workers, and a mailman.

It was an informal affair at best—no uniforms, no signals, and no stolen bases. And no umpire. Balls and strikes were called by the catchers, one of whom our team borrowed from the other. Baserunners were called safe or out based on consensus.

What could go wrong?

As it turned out, not much. For a while.

Because despite the combination of weakened knees and livers and lungs, us old guys were holding our own. And the young gals were holding theirs, despite the fact they’d been up for days cramming for finals. We were locked in a 1-0 pitchers duel.

But then through a series of walks and hits, we rednecks managed to load the bases with two outs.

Things were suddenly serious, and very much so. The chatter and clapping began in our dugout, while in the field the ladies were pounding their gloves and getting restless. And nervous.

The count ran full, and I could see the sweat building on the pitcher’s face. The intensity was getting to her. It was a look I’d seen before. No way she’d throw a strike.

And she didn’t. The ball sailed about four inches outside.

I jogged to third as the carousel of baserunners moved up one base. The runner ahead of me stomped on home plate with authority. We had a tie game.

Yes! Wait. No.

Because then the pitcher decided her last pitch was a strike after all, which was immediately agreed upon by her teammates.

Team Redneck protested in a most vehement way, of course. But in the end, there wasn’t much we could do about it. We took the field and vowed revenge our next at bat. Which never came, because after they batted they decided the game was over.

I didn’t stick around for the cookout afterwards. I imagine it was a quiet meal.

Me, I didn’t care that much. It was a chance for me to play some ball. The score was irrelevant. And I guarantee you that thought was echoed by most of the people on my team who just enjoyed playing like kids again. It didn’t bother us that we lost. What bothered us was how we lost.

We played by the rules. They didn’t.

You could see this whole episode as something bad. Not me. In fact, I see much good in it.

It lets me know that regardless of how often we’re reminded of how bad both the world and the people in it are, we still expect folks to follow the rules. To play fair. Most do. A lot don’t, of course, and never will. But as long as there is someone somewhere willing to take offense when the rules are broken, I really think we’ll be okay.

All of this has gotten me thinking about the rules my Dad first taught me about baseball. The ones I’m teaching my son now:

Play hard.

Practice much.

Don’t be afraid to get dirty.

Have fun.

Cheer for your teammates.

Keep your head up.

Win well. Lose better.

Shake hands when you’re done.

I like those rules. They’re good for baseball.

Good for life, too.