Billy Coffey's Blog, page 11

April 23, 2015

The future tree

image courtesy of photobucket.com

There is an acorn on my son’s bedside table. Found by the two of us on a Sunday afternoon walk through the backyard.

That acorn is special to him. He now has inside knowledge that he formerly did not. He is privy to the acorn’s secret.

Which is this: There is a tree inside it.

Before, my son didn’t really know the true purpose of an acorn. He once saw a cat narrowly escape a falling acorn and surmised it was the tree’s method of self defense if something got too close for comfort–tree bullets. But then on another occasion he witnessed an acorn falling for no apparent reason at all. He didn’t know what to think then.

So. Seeing as how he had found another one and seeing as how I happened to be there with him at the time:

“Daddy, what do acorns do?”

Well. Acorns are seeds, I told him. And that in the Fall they drop from the trees to the ground. If all goes well and nothing bothers it much, the acorn will grow a root. When the warm weather comes back, a tree starts to grow.

“A tree?” he wondered.

“Yes. Inside the acorn is a tree.”

It was one of those times in my son’s life when validation comes for some of his more fantastical opinions. Are their dragons and fairies and pots of gold at the ends of rainbows? Yes. There had to be. If it’s true that a giant tree lives in a tiny acorn, then those things have to be true as well.

Wonderful!

But: “What do you mean if all goes well and nothing bothers it?”

Without going into the whole biological process (which I really didn’t know), I told him in broad strokes that the acorn needs things in order to turn into a tree. Water, for one. And good soil. Sunshine, too. If it has all of those things, it will grow.

We looked around and found four more acorns scattered across the yard. Those, he said, should stay were they were. But he first one went into his pocket.

I understood. Sometimes we need small examples of larger truths.

Like that acorn, we all have something big inside us. And like that acorn, what lies there must be tended to and cared for in order to grow.

It won’t be easy. That acorn is small. We are, too. And both of us are stuck in a world where there are plenty of things determined to keep us that way.

April 20, 2015

The game of life

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Work at a college around a bunch of teens and twenty-somethings long enough, and you will begin to ask yourself some questions. “How can anyone wear flip-flops in December?” is one. “They actually call that music?” is another. And then there is the biggie:

“Was I really that stupid when I was their age?”

The answer, of course, is yes. Absolutely.

For instance. When I was twenty, I believed:

That life was simple.

That the future was set in stone.

That love was all I needed.

That there is good and there is bad and there is nothing else.

That faith would make everything better.

That the young had more to offer than the old.

That the new held more promise than the tried and true.

Twenty-two years have passed since then. Twenty-two very long, very frantic, and at times very painful years. Whichever of the above beliefs were not proven ill-conceived through marriage and children have certainly been proven so through experience. I know better now. Much, much better.

For instance.

I know that life is not simple. It is hard and scary and tiresome, but it is not simple. If you think it is, then you’re not really living it.

I know that the future may well be set in God’s eyes, but it certainly isn’t in mine. What happens tomorrow is most often a direct result of what I do today, which is most often a direct result of what I did yesterday. The choices I make this day, this second, reach further and deeper than I can possibly realize. Every moment is a defining moment. Every moment is a moment of truth.

I know that love is not all I need. I know that without such things as grace and forgiveness and effort love will crumble upon itself. Love is not the all-powerful cure that poets and dreamers have crafted it to be. It must be nurtured and fed and tended to. Love is not a firm rock that can withstand anything. It is a delicate rose that can wither without attention.

I know that there is good and bad. But I also know that there is more, and I need to look no further than my own heart for proof. For there resides the good man I could be, the flawed man that I am, and the man who must choose daily which he will become.

I know that faith alone is feeble, that only when it is polished with action does it truly shine. Too many times I have prayed for things to get better but did nothing to make them so. God may move mountains, but that’s because mountains can’t move themselves.

I know that the vigor and strength of youth may power society, but it’s experience that drives it. Life has rules, and unfortunately they are not given all at once, but bit by bit as we go. That’s why parents and grandparents are so important. They’ve been there. And because they have, they know a lot more than we do. Time changes. The times do not.

And lastly, I know the new may be exciting, may be revolutionary, may even be promising, but I also know they may not be that way for long. The very things that have sustained us in the past are the things that guarantee us a bright future, things like the importance of family and God, things like the virtues of kindness and loyalty and forgiveness. Such things are woven into us. They are the foundation of who we are and who we will become.

That’s what I know now. Will those beliefs change? Maybe. Check back in twenty years and I’ll let you know.

April 16, 2015

Avoiding life’s sting

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I see him by the steps as I pull up. Standing there, staring at the door. He’s still there when I park, still there as I climb out of my truck with shopping list in hand. Still there when I sidle up beside him.

“Hey Charlie,” I say.

He turns and looks at me. “Hey.”

“Whatcha doin’?”

“Oh,” he says, “just waitin’.”

“Uh-huh,” I answer.

I decide not to say anything else. I know what might happen if I do, and I know what might happen after that. Because Charlie is one of those people who can start a conversation in the real world and finish it somewhere in the Twilight Zone.

But then I figure what the heck, I have some time to kill.

“You know,” I say, “they’re not gonna bring your groceries out to you. You gotta go in and get them yourself.”

Charlie nods. “Yep,” he says. “I’ll be going in directly. Just gotta wait for it to leave.”

“Gotta wait for what to leave?”

Charlie points to the flying speck of something in front of the door and says, “That.”

I squint my eyes and stare ahead, trying to figure out what I’m looking at. After careful consideration, I decide it’s a bumblebee.

“You’re not going in because there’s a bee in your way?” I ask.

“Yep.” Then he says, “Nope,” just in case he got his words mixed up.

The door swooshes open then as an older woman rolls her grocery cart out, oblivious to the certain death that hovered over her. Charlie winces as she walks past, exhaling only after she was clear of the danger zone.

“You allergic to bees, Charlie?”

“Nope.”

I nod, trying to find the right words to ask him what I need to ask him next. “You, um…you ain’t, you know…afraid of them, are you?”

“Nope.”

I nod again. “Okay, well want me to go get your beer?”

I don’t know for sure that Charlie is here for his beer. He might be low on something else, maybe hamburger or peanut butter or ice cream, because Charlie loves his ice cream. But he loves his beer even more, and I have a feeling that his shaky right hand isn’t completely due to the bee.

“Nah,” he says. “I’ll go. I got the time to wait. Just don’t wanna get stung.”

It’s then that I realized Charlie really is afraid. I’m not convinced that is a bad thing, though. No one likes getting stung by a bee. It hurts. Everyone knows that.

More than that, I realize people do this sort of thing all the time. Myself included. We all eventually realize not just where we were, but also where we want to be. And we realize there is usually some sort of Bad blocking the way. It could be a rejection slip or an unreturned phone call. Could be nerves or insecurity. Could even be the prospect of success after years of failure.

Regardless of what it is, that’s what’s floating between you and it. Between where you are and where you want to go.

The size of what’s blocking your way doesn’t matter either, because the fact of the matter is this—there is risk involved in proceeding further. You could fall. You could fail. You could be disappointed.

You could get stung.

And that hurts. Everyone knows that.

The alternative, of course, is to stay where you are. With practice and dedication you may convince yourself that you’ve gotten this far, which is further than some and maybe even most. That might be good enough. And you might even begin to believe that holding onto the prospect of what you could have done will be good enough.

I could have been a writer. Or a teacher. Or a nurse. I could have gone to school. I could have had that job or that career. But there was this Bad between me and it and, well, things just didn’t work out.

But you know what? That never works.

I know from experience that Could Have is just the same as Never Did.

“I’m gonna go in, Charlie,” I say. Then I look at him. “You know that bee’s gonna fly right out of my way, right? Because I’m bigger than the bee.”

“Yep.”

“Okay, then.”

I leave him there at the door and pick up the few things on my list. Charlie’s still standing there when I head back to my truck.

“Don’t want to get stung,” he says again.

“I know,” I answer.

April 13, 2015

Playing by the rules

![scan0005[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1429040496i/14520584.jpg) Once upon a time, I was a baseball player. And that’s putting it mildly.

Once upon a time, I was a baseball player. And that’s putting it mildly.

It would be closer to the point to say I was a baseball fanatic. While most teenaged boys would have posters of scantily-clad women or music groups tacked to their bedroom walls, I had ballplayers. And while most would spend their free time perusing the latest issue of Rolling Stone, I would spend mine with Baseball Digest.

You get the idea.

Fortunately (and I can say that now–“fortunately”), God had other things in mind for my future. Baseball was my first true love, and our breakup was a tough one.

Five years ago:

Though the two of us have gone our separate ways, we still have opportunities now and then for a little flirtation. One of those opportunities came last week, care of my job.

College kids are cocky by design. They know much about the world and little about themselves, and the combination results in broad declarations and high claims. So when the girls fastpitch softball team challenged the faculty and staff to a game, the results were obvious. And not.

It began a few years ago with a simple conversation between one college softball player and one groundskeeper. I’m not sure who first said what. All I know is at some point one said something about being a much better ballplayer than the other, which was taken as an insult, which resulted in more insults, which resulted in the first ever softball game between the girls fast-pitch team and the staff.

The games are always interesting. There is an extraordinary amount of fanfare involved, all of which can be boiled down to one word—pride. That’s what fuels these games. It’s not just pros against Joes, it’s the experience of age versus the cockiness of youth. Both teams are out to prove something, whether it be that that a bunch of old men can still kick it up a notch when needed or that the gals can hit and throw and run just as good—better, even—than the guys.

So while there is plenty in the way of friendly trash talking, there is also an undeniable seriousness beneath. My team doesn’t want to be beaten by a bunch of girls. Their team doesn’t want to be beaten by a bunch of groundskeepers, a few office workers, and a mailman.

It was an informal affair at best—no uniforms, no signals, and no stolen bases. And no umpire. Balls and strikes were called by the catchers, one of whom our team borrowed from the other. Baserunners were called safe or out based on consensus.

What could go wrong?

As it turned out, not much. For a while.

Because despite the combination of weakened knees and livers and lungs, us old guys were holding our own. And the young gals were holding theirs, despite the fact they’d been up for days cramming for finals. We were locked in a 1-0 pitchers duel.

But then through a series of walks and hits, we rednecks managed to load the bases with two outs.

Things were suddenly serious, and very much so. The chatter and clapping began in our dugout, while in the field the ladies were pounding their gloves and getting restless. And nervous.

The count ran full, and I could see the sweat building on the pitcher’s face. The intensity was getting to her. It was a look I’d seen before. No way she’d throw a strike.

And she didn’t. The ball sailed about four inches outside.

I jogged to third as the carousel of baserunners moved up one base. The runner ahead of me stomped on home plate with authority. We had a tie game.

Yes! Wait. No.

Because then the pitcher decided her last pitch was a strike after all, which was immediately agreed upon by her teammates.

Team Redneck protested in a most vehement way, of course. But in the end, there wasn’t much we could do about it. We took the field and vowed revenge our next at bat. Which never came, because after they batted they decided the game was over.

I didn’t stick around for the cookout afterwards. I imagine it was a quiet meal.

Me, I didn’t care that much. It was a chance for me to play some ball. The score was irrelevant. And I guarantee you that thought was echoed by most of the people on my team who just enjoyed playing like kids again. It didn’t bother us that we lost. What bothered us was how we lost.

We played by the rules. They didn’t.

You could see this whole episode as something bad. Not me. In fact, I see much good in it.

It lets me know that regardless of how often we’re reminded of how bad both the world and the people in it are, we still expect folks to follow the rules. To play fair. Most do. A lot don’t, of course, and never will. But as long as there is someone somewhere willing to take offense when the rules are broken, I really think we’ll be okay.

All of this has gotten me thinking about the rules my Dad first taught me about baseball. The ones I’m teaching my son now:

Play hard.

Practice much.

Don’t be afraid to get dirty.

Have fun.

Cheer for your teammates.

Keep your head up.

Win well. Lose better.

Shake hands when you’re done.

I like those rules. They’re good for baseball.

Good for life, too.

April 9, 2015

Lost and found

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I have a friend who’s gotten lost so often and so bad that he thinks it’s his lot in life. Not just lost trying to get from point A to point B, either. Lost as in trying to do the right thing and be the right person but somehow ending up doing and being the opposite. He says God hates him for this. He’s damaged goods now.Me, I think we sometimes underestimate just how easy it is to lose our way in life. And, like my friend, we lead ourselves to believe that only bad people get lost. So if we’re lost, we’re bad.

And if we’re bad, then God doesn’t want us. Can’t use us, either. So the best we can do if we ever wander off the path is to try and find out way back and then just stumble along, heads down, in defeat.

But I don’t think so.

The great thing about the Bible isn’t just that it’s the word of God, but that it gives an honest portrayal of the people in it. And a quick look at the giants of both the Old and New Testaments tells us that people got lost back then, too. Adam and Eve got lost. So did Moses. David was called a man after God’s own heart, and he still got lost. Paul was lost before finding the Damascus road. Peter and John? Lost, too.

It happens. To all of us. No one is exempt.

Unusable? To God there is no such thing as unusable. We can all be used by Him, regardless of what we’ve done or what we haven’t. David committed unspeakable acts. God still loved him. Paul murdered thousands of Christians, but God still used him as the voice to speak to us all.

And damaged goods? Hey, we’re all damaged goods. There isn’t anyone alive who lives to his or her truest potential, who says and thinks and does exactly what is right and nothing else. Even Paul, that murderer reformed who was touched by the hand of God, fought daily with himself over what he should do and what he does anyway.

Yes, we’ll all get lost. We’ll take many wrong turns and end up in many places we’re not supposed to be. And we will hurt and suffer because of it.

But know this: the love and power of God is such that He will use every one of our wrong turns to bring us to the right place.

April 6, 2015

Between despair and hope

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

It’s come and gone now, but Easter is still on my mind. That’s how it is when you get older. When I was a kid, Easter wasn’t even an entire day, really. It lasted only a couple of hours on those Sunday mornings, beginning with waking up to dive into all that candy stuffed into the basket left for me on the kitchen table and ending just a few hours later, when I walked out of church. When you’re just coming up in the world, Easter seems a little overblown.

After you’ve come up, though? Well, then things get different. You get to that age after you find out the Easter Bunny’s just a poor man’s Santa but before you start sneaking chocolate into your own kids’ baskets, and Easter maybe dims a little more. Maybe it’s the time of year that does it. It’s springtime when Easter rolls around, and everything is new and fresh and drowned in color, and what’s on your mind is more the rising temperature than a rising Lord. You take it for granted that the Miracle happened. The stone got rolled away and the angel said Look inside and inside was empty. You hear things like that too much, sometimes it doesn’t seem so special anymore.

But then something new happens, usually once you get some age and you find that you’re starting to attend more funerals than weddings. Life takes on a different look right about then. The shine starts to wear off. You start thinking less about where you’re at and more about what’s laying on ahead. You maybe discover what Easter means for the first time in your life.

I wouldn’t say that’s where I am personally, but I’d say it’s near enough. To me, Easter is the holiest time of the year. It’s a period to be quiet and listen—days to both despair and hope. That last point is what’s been on my mind.

For a lot of the religiously minded, Easter is really just three days rather than one. It begins on Good Friday, when we pause in our otherwise busy and stressful lives to consider this person who was both God and man, dying such a horrible death, setting himself apart from God so we would never have to ourselves. It ends the following Sunday with that empty tomb full of promise—proof enough for any believer that death has lost its sting.

It’s that Saturday that I want to talk about, though—that Saturday between the first Good Friday and that first Easter. The day between all that despair and all that new hope. Nothing much gets said about that day, and so it’s all left to some imagination and hard thinking. I think about the Marys and the disciples, all shut up inside somewhere, hiding and grieving. I think about them all trying to hold onto a faith that maybe can’t help but be slipping away, searching for any reason at all to believe, and I think about how that seems an awful lot like what most of us feel everyday.

That first Saturday? That’s our lives. Those hours are our years, ones spent trying to hope and understand. Trying to find the reasons behind the horrible things that happen to us all. It’s a tough thing, this business of living, especially when you put a God whose ways are so far apart from our own at the center of it. We stand in the present now just as the disciples stood in it then, and the choice we have is the same as theirs. We can look back to despair, or we can look ahead and hope. It’s a daring hope, no doubt, one that seems near to impossible. And yet that is where we all must turn, and that is what we all must cling to—that stone rolled away. That empty tomb. Because we can do without a great many things in life and still call ourselves living, but we cannot go without hope.

March 31, 2015

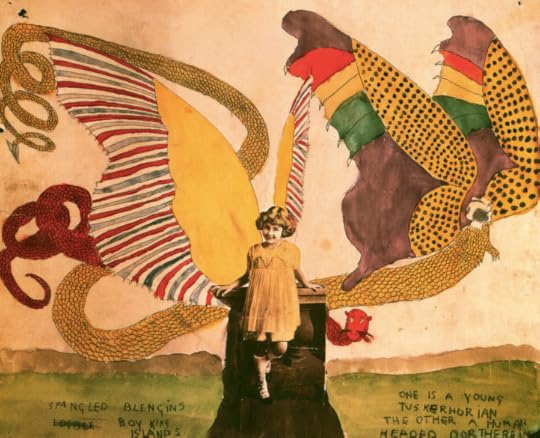

The value of our art

image courtesy of google images. Spangled Blengins, Boy King Islands. One is a young Tuskorhorian, the other a human headed Dortherean by Henry Darger

Let me tell you about Henry Darger, the man who wrote one of the most detailed and bizarre books in history.

Never heard of him? Me neither. At least, not until I happened to stumble upon his story a few weeks ago. Seems strange that someone who did something so grand could be so unknown, doesn’t it? But it’s true. In fact, you could even say that’s why Henry was so extraordinary.

image courtesy of google images

He was a janitor. Nothing so special about that, but nothing so wrong with it, either. There is no correlation between who a person is and what that person does for a living. Einstein was a patent clerk. Faulkner a mailman. Henry Darger mopped floors.

An unassuming man. A quiet man. He never married, never really had friends. Just a regular guy living a regular life, one of the faceless masses that occupy so much of the world who are here for a short while and then gone forever.

Henry left in 1973.

There are no accounts of his funeral. I don’t know if anyone attended at all, though I like to think they did. I like to think there was a crowd huddled around his casket that day to bid him farewell.

It is an unfortunate fact of life that so many people are discovered to have been truly extraordinary only after their passing. Such was the case with Henry. A few days after his passing, his landlord went through his apartment to ready it for rent. What he found was astonishing.

What he found hidden among Henry’s possessions was a manuscript. Its title may give you a clue as to the story’s scope and magnitude:

THE STORY OF THE VIVIAN GIRLS, IN WHAT IS KNOWN AS THE REALMS OF THE UNREAL, OF THE GLANDECO-ANGELINIAN WAR STORM, CAUSED BY THE CHILD SLAVE REBELLION

Did you get that? If not, I can’t blame you. I had to read the title three times to even understand a little of it, and that doesn’t count the time I actually wrote it out.

The breadth and scope of Henry’s book went well beyond epic. The manuscript itself contained 15,000 pages. Over nine million words. Over 300 watercolor pictures coinciding with the story. Some of the illustrations were so large they measured ten feet wide.

A lifetime’s worth of work. Years upon years of solitary effort, hundreds of thousands of hours spent writing and painting, creating an entire saga of another world.

And all for no apparent reason. Not only did Henry Darger never seek any sort of publication for his work, he never told a soul about it. His book was his dream and his secret alone.

I’ve thought about Henry Darger a lot since I first read about him. Which, as change or fate would have it, just to happened to be the very week my newest novel released. A tough thing, that. You’d think it wouldn’t be, perhaps, but it is. No matter who an author is or how successful he or she may be or how many books or under his or her belt, the most important thing to us all is that our words matter. Matter to others, matter to the world. We want what we say and think and feel to count for something.

But Henry Darger reminds me that none of those things mean anything. In the end, we cannot account for how the world will judge our work, and so, in the end, the world’s opinion really doesn’t matter. Simple as that.

What matters—what counts—is that our words stir not the world, but ourselves. That they conjure in our own hearts and minds a kind of magic that neither the years nor the work can dull. The kind of magic that sustains us in our lonely times and gives our own private worlds meaning. The kind of magic that tinges even the life of a simple janitor with greatness.

March 26, 2015

Creating magic

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I’ll say I’m a writer because I can’t speak. At least not well and not in front of large groups of people I do not know. I’ve done so anyway, and many times. And truthfully, I do just fine as long as I don’t count the “aint’s” and dropped g’s that come out of my mouth.

The invitation to speak that I received recently wasn’t one I could pass up. It wasn’t a fancy conference, wasn’t in a fancy city. It didn’t pay well (actually, it didn’t pay at all). It was instead for career day at the local elementary school.

It isn’t often that I get to play author, much less play one for an entire day. Despite the props I brought along—five books, a typed manuscript, and one bulging notebook—I knew it would be a rough road to travel. After all, I was going up against firemen and police officers and radio personalities. A writer would have a tough time competing with that with a bunch of grownups, much less a hundred fourth graders.

But as it turned out I didn’t have much to worry about at all. Sure, they were fourth graders—that peculiar brand of kid to which both reading and writing are anathema. So I started with the fact that when I was their age, I hated reading and writing, too.

It was all downhill from there.

I’m smart enough to know that kids aren’t much interested in publishers or first drafts or the horror that is the adverb, smart enough to know that adults aren’t much interested in them either. But I’ve found over the years that everyone, regardless of age or interest, perks up whenever I mention a writer’s primary gift to the world.

Not wisdom. Not inspiration. Not tight plots or moving themes or even memorable characters. No, writers do what they do because of one reason and one reason only—

They get to create magic.

They didn’t believe me, of course. Not right away. One kid asked me to make his pencil disappear if I knew magic. Another wanted me to guess the number she was thinking. I told them I couldn’t and that it didn’t matter, because the magic writers do was better. It was the greatest magic of all.

It was the magic of writing words down on a page that make pictures in other people’s minds.

It was the magic of being able to create entire worlds from scratch and put anything I wanted to in them.

It was the magic of being able to touch another person’s heart, a person who might live far away, someone you’ve never spoken to and likely will never meet.

And best of all, I told them, is that everyone possesses a bit of that magic. Anyone could be a writer. Didn’t matter if you were rich or poor, didn’t matter what color you were, didn’t even matter if you went to college or not. That magic was still in us.

It takes time, of course. All magic does. But I told them that if they did three simple things, that magic would grow and eventually spill out.

You have to read, I said. Every day.

And you have to write. Every day.

And most important of all, you have to believe you’re special. Because there is only one you in this world, and the way you see life is different than the way anyone else who’s ever lived has seen it. That’s why your story is so important. So needed. After all, that’s what the magic is for.

Turns out that an informal poll conducted by the teachers placed me second of the day’s top speakers. The winner was the radio guy. I wasn’t surprised. I can’t compete with someone who’s met Taylor Swift and Trace Adkins. I wouldn’t even try.

But a teacher told me that the next day when it came time for her class to do their journal writing, there was much less grumbling than usual. They were ready. Eager. When she asked why, her kids told her they wanted to make some magic.

Me, too.

March 23, 2015

When you make a mess

image courtesy of photobucket.com

How it ended up like this I cannot say. I know I didn’t intend for it to happen. But happen it did. Not all at once—these things never unfold all at once—but slowly, like how spring turns to summer or twilight melts into full dark.

And it’s dark now, oh yes it is. Metaphorically, anyway. It’s just after one in the afternoon on a beautiful Saturday, and in this, at least, I’ve found a blessing. It’s early still. Which means if I get started now, I can get this mess cleaned up by tonight.

It started simply, as most messes do. And also like most messes, I went into it with the absolute best of intentions. And yet what was to be a quick trip upstairs to straighten my office has resulted in an apocalypse of papers and books the likes of which seem almost Biblical. My wife nearly called 911 when she walked in a few minutes ago. My kids dared me to ever tell them to throw away a notebook again. FEMA may have to be summoned.

I don’t know how this happened.

I promise you.

But that’s what we always say when we make a mess, isn’t it? Me, anyway. They’re often the first words out of my mouth—“I don’t know how this happened.” Followed closely by the points I’ve already mentioned:

I don’t know how things got this way.

I never wanted this.

I had the best of intentions.

Of course none of those matter, at least not now. All that counts is the mess. The whys and hows are irrelevant.

The only question is how I’m going to clean it up.

It won’t be easy. Messes never are. It requires digging through the garbage you’ve made for yourself. Cleaning up a mess hurts so much because along the way you always discover those things that should have mattered but were somehow forgotten instead (like the I love you Daddy! card I just found mashed into a novel I never finished reading). It hurts because so much damage has been done that you think things will never really be fixed—the mess will always be there, and things will never be the same again.

And in that moment of absolute remorse, a part of you believes that’s the way it should be. You messed up. You—the one who is old enough and wise enough to know better, the one who’s witnessed friends and family and strangers on the television news make their own messes and said “That’ll never be me.”

You.

Me.

So here I sit, in my mess.

For me, in this moment, it consists of little more than notebooks and papers and half-finished manuscripts and, amazingly enough, a half-eaten box of Fiddle Faddle. For you, things may be much worse.

Trust me when I say that makes no difference. When it comes to a mess, there are no degrees. A mess is a mess. And you and I will get through our messes together. We will fix things.

For me, it’s book by book. For you, perhaps relationship by relationship.

Paper by paper.

I’m sorry by I’m sorry.

Cleaning.

Healing.

Minute by minute.

Day by day.

We will straighten and clean. We will dust off the important things we’ve misplaced and toss out those things we thought we needed but didn’t. We’ll put away and take out.

We will make things sparkle again.

March 20, 2015

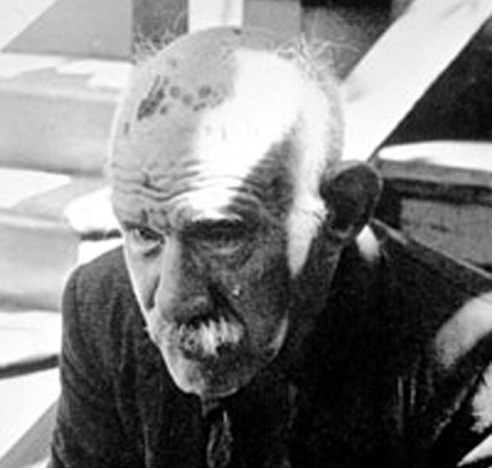

The John she used to know

image courtesy of google images

Dorothea will tell you she and John would have been married 47 years come June. That’s how she always puts it—“would have been” instead of “will be”—past tense instead of future, even though John is still alive and they are still married. They still live in the same brick house two blocks from the Food Lion; are still seen driving the same gray sedan, though these days it is Dorothea driving John. He still gets around, she’ll tell you that as well. She’ll say her husband still reads the Richmond paper each morning and still takes his coffee strong and black and that both are absolute. What is not absolute, and in fact what Dorothea now questions every day of her life, is where her husband has gone, and who has taken his place.

They have four children, each of whom are grown and two of whom have moved away. Ten grandchildren, four great-grandchildren. The entire family gathers twice a year at the old home—every Christmas and Fourth of July. Those are festive times. Dorothea says there must be some special magic when the whole family is together, something about the sound of conversation and giggling children, that makes her husband feel like her husband again.

Those other 363 days can often be long. Sometimes they can be frightening, such as the afternoon last November when John went to check the mail and never returned. Dorothea found him three blocks and fifteen minutes later, sitting in the middle of the road, his bathrobe open and tossed by the breeze.

It began sudden, a year ago now, the same way so much bad in the world begins—with something small and ordinary. John had a history of migraines, and while the headaches that had plagued him for weeks were neither strong nor lasting enough to be called those, they were enough of a nuisance that Dorothea scheduled a doctor’s appointment. Tests were done. The doctor called them both back into his office three days later with the news. There was a tumor on John’s brain. It was inoperable.

The doctor said three months, six at the most. John’s outlasted both of those predictions. He always was a tough man, Dorothea will tell you. That’s how she’ll put it—“was” rather than “is.” Because she doesn’t know if the man she would have been married to for 47 years come June, the man who has given her four children, a brick house, a gray sedan, and a good life, is really John at all. She thinks that person left. Most of us in town would agree.

He was always a nice man, a kind man, easy with praise and concern about how you and your family are and if you’re still going to church every Sunday. In all their years together (much more than 46—John and Dorothea dated five years before they married), she had never heard him cuss. Three days after that fateful doctor’s visit, John came inside the house and said the damn key wouldn’t fit in the damn ignition of the damn car.

The cussing has grown worse since—horrible words that Dorothea never thought her husband capable of uttering. He’s grown impatient with the world, cursing the neighbors and the government and “the whole damn thing.” Once, he grew violent and pushed Dorothea against the kitchen sink, screaming at her, wanting to know what she’d done with his wife.

Though she remains strong and faithful, Dorothea has said she often wonders why she must sit idly by, watching as what remains of this man’s life slowly slips away. She wonders too how it is that a mass of deformed cells pressing against her husband’s brain can turn him into someone else. In all outward ways, he is still John. It is still his face and his body, the same hairline and mole just below his right ear. And yet he is no longer John. He has become someone else. He has become a stranger.

And Dorothea is left to wonder this: What makes us “us?” What is that quality that defines us and renders us unique? Where does that quality lie? And perhaps most important of all, where does that quality go when it appears to be taken away?

I don’t know the answer to that question. It breaks my heart that John and Dorothea must endure such a thing, and that there are so many others who must endure it as well. It hurts. It’s not fair.

But Dorothea isn’t angry. That’s what has struck me most about her these last months. She’s not mad at John, nor his tumor, nor even the God who doesn’t seem interested in healing them—in bringing her husband back. It’s remarkable to me, though not to her. To Dorothea, the question now isn’t Why. It isn’t How. It’s only What.

“God wants me to take care of him,” she says of the man who used to be John. “That’s all I need to know.”

And so she will, until some near or far-off day when Dorothea will say goodbye to him for now. Only for now. And the faith she has that God will equip her to care for her husband now is the very faith that allows her to know that when they meet again, it will be John she sees. The old John. And he will thank her.