Billy Coffey's Blog, page 10

May 25, 2015

For when you’re weary

I’m not sure how long I’ve carried this picture, tucked inside the little notebook I keep in my back pocket. I no longer remember where I first stumbled upon it, or how, or the number of copies I’ve worn out by unfolding it and folding it again whenever I need the reminder. It’s served me well over the years. Kept me going. When you have a dream that sometimes feels close enough to embrace as fact and other times feels so far that it seems the two of you will always be destined as strangers, keeping on becomes the hardest thing and the most important. Victor Hugo once said that each man should frame life so that at some future hour fact and his dreaming meet. I would imagine that sentiment applies to women equally. The picture at the top of this post is a reminder of my own future hour. It makes me see that I’m not alone in what dreams I have. There are others out there—you, perhaps—whose aim in life reaches high. There always have been.

The picture was taken in 1961, at a place called the Aldershot Club. Where the club was (or remains), I cannot tell you. I suppose it’s enough to say it wasn’t a very popular place with the day’s younger folk, or perhaps it was the club’s entertainment that night wasn’t enough to draw a larger crowd. According to the note I scrawled on the back, a total of eighteen people spent that night dancing. I would imagine few of those cared to admit they were in attendance after the fact. It does seem to me, though, that they’re all enjoying themselves. I’ve often though that despite it all, that’s the most important thing.

Look close enough, you can make out three-and-a-half of the four faces on the stage—singer, guitarist and bass player, and part of the drummer. I doubt the photographer intended to make such a strong point in leaving the band to the shadows, but the result is poetic in a way and not at all ironic. Those four were surely in the shadows, lost among a sea of other bands with aspirations just as lofty. They are too far away for me to gauge their expressions. I like to imagine them fully involved in their music, feeling each note as it courses through with a precision that indicates not only inherent talent, but unending practice.

That’s how we all start out, don’t we? Doesn’t matter if your goal is to be a musician or a writer or a professional _______, this picture represents the beginning. Obscurity and under-appreciation. Playing to a crowd that barely reaches double digits or writing novels or short stories or blog posts read by about the same number of people. We toil under the assumption—the hope—that it won’t always be this way, that the hour Victor Hugo expressed when fact meets dream will surely come. We do this even as the inner critic, that realist to counter an almost holy optimism, shouts that you and I are only two of many, that our dreams are no less than the dreams of billions more, and how is it that we are so special to warrant fulfillment? Ours is a hard world, after all. Often enough, the goal becomes not to rise above but merely not to sink. Forget about overcoming, sometimes all we can hope for is to simply get by.

Worse, if we are strong enough to dream we must also be courageous enough to admit that dream rarely, if ever, truly arrives. A part of us already knows that no matter how tall the mountain we climb, at its peak will lie another, taller one in the distance. That is the cost demanded of those led beyond the doors of a boring life, an existence frittered away with passionless work, the only light a coming weekend or those seven summer days of vacation. There is an allure to the life of the masses that the life of a dreamer cannot match: that sense of being settled—that, good or bad, this is how you will spend your remaining days. It is a rut, no doubt, but at least one that is straight and relatively smooth and travels over no mountains.

I wonder, looking at this picture, if the four men on the stage are thinking about a life in one of those ruts. The men and women on the dance floor look happy enough. They are all perhaps married, all gainfully employed in jobs that offer steady pay to balance out mortgages and bills. A better life, perhaps, than that of an artist, living gig to gig and wondering if it will always be that way. Or maybe it is that those four men understand what many of us do—a life of settling hurts no less than a life of dreaming. Its pain is merely spread out, constant enough to dull us to it but there. We would hurt if we gave up just as we would if we keep going, because the world is made for bruising. That’s why I think in the end it doesn’t matter who chooses the ruts and who challenges the mountains. We are all extraordinary just by making it to the end of our lives. We all deserve a measure of rest after.

Maybe that’s what Paul is thinking. And John. And George and Ringo. Maybe they’re thinking that some people settle and some never do, and you put them both together and what comes out is music. Regardless, they kept on. And a year and a half later, the world would know the Beatles.

Maybe—just maybe—that’s you up on that stage. Standing away from and above the smattering of some crowd, vowing to play as if it were millions. If so, I say let’s keep on. Let’s play and sing and not grow weary. For there’s a mountain to climb, friend, and another on ahead.

May 21, 2015

The puddle

image courtesy of photobucket.com

It was a hard rain, and fast—the sort of pour that early May is known for here. It came from clouds the color of dark smoke that rolled over town like a wave, here and then gone over the mountains. What was left in its wake was the grateful song of a robin from the oak in the backyard, and the sugary smell of wet grass and tilled earth.

And the puddle.

It was not a deep puddle, nor was it wide. Maybe three lengths of my boot and deep enough to reach the second knuckle of my index finger. It lay just beyond the mailbox at the end of the lane, a pothole the rain had converted into a passing mirror of liquid glass.

The mailman had delivered the day’s assortment of junk mail and bills just before the first cracks of thunder. Now that the sun had returned and the robin was singing and that sweetness was in the air, I decided to go check the box. A small boy riding a dirt-road-brown bicycle rounded the corner as I made my way down the lane. He tried a wheelie, barely managing to get the front tire off the ground, then uttered a Yes! as if what he’d just done was almost supernatural.

I gave the puddle a wide berth—I was in blue jeans and flip flops, and didn’t want to risk getting either wet. There are few things in life more irritating than wet cuffs on your blue jeans.

I’d just pulled the mail out of the box (a reminder of the upcoming Book Fair, a ten dollars off coupon for Bed, Bath & Beyond, and the cable bill) when the boy squeezed the brake levels on the handlebars. The bike skidded nearly ten feet on the wet pavement, the last four or five fishtailing, which produced another Yes!, this one whispered.

I looked up. The boy was staring at my feet, where the puddle lay. A soft breeze rippled the surface, and for a moment, however brief, my mind turned to something I’d once heard from an old relative—all mirrors have two sides, she’d said. One side you look at. The other side looks into you.

“That’s a pretty cool puddle,” the boy said to me.

I looked at it and then to him. “Sure is.”

He nodded, and I got the feeling it was the sort of nod that was more the punctuation on the end of a decision rather than an agreement with what I’d just said.

I thought he was going to ride through it. That’s what I would have done at his age. Plus, it would have the added benefit of turning his dirt-road-brown bike back into the red I suspected was underneath. But he didn’t. He threw down the kickstand and dismounted as if from a mighty steed in the Old West.

He walked to me and toed the edges of the puddle.

“You gonna use that?” he asked.

“Nope.”

“Mind if I borry it?”

“You can borrow it all you want.”

He nodded and took three kid-sized steps back. Then he ran forward, leaped, and landed square in the middle of the puddle. Water billowed up over his legs, reaching his waist. He lands with a smile that to me is brighter than the rainbow over us.

“Thanks, mister,” he said. “You can have a go if you want.”

He rode off, a plume of road water trailing behind him. I held the mail in my hand and tried to remember the last time I jumped into a puddle in the road after a May rainstorm. Years, probably. Probably long ago, back when I had my own dirt-road-brown bike.

Puddles aren’t adult things. Adults avoid them. They splash and make a mess and get the cuffs of your jeans wet. It isn’t responsible or mature.

Maybe. But then there’s that mirror inside each of us. The one we look into that shows us who we are, and the one that looks into us and shows us who we should be.

I won’t tell you if I jumped or not. Some things need to stay secret. But I will say this—I can’t wait for it to rain again.

May 18, 2015

Fisher of men

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Next time I won’t order the fish. That’s what I thought after he left. If I would have ordered chicken or steak or shrimp I would have gotten my food earlier, which meant I would have prayed earlier, which meant he wouldn’t have seen me. But he did, and like they say, that is that.

Lunch time for me is a sort of take-it-when-you-can thing that depends on how busy I am and how far I want to drive. Most of the time that places me inside a small restaurant downtown, just a few blocks from my work. Nice place with nice food. Very friendly, very tasty, and very quick.

So. The fish.

An extra ten minutes, the waitress said. “You sure you don’t mind waiting?”

No.

The man came in five minutes later and was shown to the table across from mine. We smiled and nodded like friendly folk do, and I was fairly certain that would be the extent of our interaction. It wasn’t. Because soon afterward my fish arrived and I offered a very silent and inconspicuous prayer.

He was staring at me when I opened my eyes.

“So you’re a churchgoer?” he asked.

“Yep,” I answered. “You?”

“Never,” he said in a tone that seemed rather proud.

I nodded and went back to eating.

“Don’t believe in God myself,” he said. “Just seems like a waste. I guess that means I’m going to hell, huh?”

I’d been around long enough to know when I was being baited into a conversation I really didn’t want to get into. This, I thought, was one of those conversations.

So I just said “Not my call” and raised another bite of fish.

“Not your call,” he repeated. “That’s typical.”

I chewed and thought about the last little bit of what he said. It was more bait, of course. And it was still a conversation I didn’t want to have. But maybe it was now one I should.

“Typical?” I asked.

“Yeah, typical. You people like to use those pat little answers for questions you just don’t know or are just too afraid to face.”

“Like whether you’re going to hell?” I asked.

“Sure. That just bugs me. Christians say that God is love, but if you don’t go along with the program then you get eternally punished. That doesn’t sound like love to me, that just sounds hypocritical.”

I shrugged. “Not really. I reckon God’s spent—what, fifty years or so?—trying to get you to pay attention to Him. He’s arranged circumstances, given you a glimpse of things you don’t normally see or think about, even spoke to you. There’s no telling how many chances you’ve gotten to say ‘Hello’ to God after He’d said the same to you. But you have a choice. That’s how He made you. You can choose to listen or not, choose to believe or not, choose to accept or not. I take it that so far, it’s been not. So if you spend your whole life telling God to stay as far away from you as possible, He’s gentleman enough to do just that when it’s all over. So yes, I suppose if you keeled over right here right now, you’d go to hell. But it’s not me who’s gonna send you there, and it’s not God either. It’s you.”

He looked at me. I looked back.

“Alright then,” he said.

We both continued our meals. Ten minutes later he squared his tab with the waitress and left, pausing at the door to offer me a smile and a tip of his hat.

The waitress focused on me then, asking if I’d like more coffee or just the check. I asked for a check and an answer.

“That fella come in here a lot?”

“Sure,” she said. “He’s the preacher at the church next door.”

“He’s the what?” I asked her.

“The preacher.” Then she smiled and added, “Was he havin’ a little fun with you?”

“Don’t know if I’d call it fun.”

“He likes that,” she said. “Likes finding people who call themselves Christians and tests them. Sees if they know their faith or just accept it. These days we have to be ready to defend it, don’t we?”

“We do,” I said.

And that’s the truth. It isn’t enough to just accept our faith nowadays. We have to stand for it. And this is the truth, too—next time I go there to eat, I’m ordering the fish. Maybe he’ll stop by.

May 14, 2015

The boys of summer

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

In the late springs it was always school and chores after, and when the grass was cut and the garden weeded, there would be time for an inning or two. Then May would give to June. I cannot fully convey just how special that time of year was to me growing up—those few weeks when the air would first warm and then the mountains blossom, and that long string of big, black X’s on the calendar I’d begun in September finally ended. Summer vacation. That’s when the season would really start. That’s when the lot would open.

There were five of us neighborhood kids, and we’d always get together once school was out. There was me and Greg and Chuck and Noel and Jonathan. Sometimes there was a sixth named Duane, but it wasn’t often he was allowed to play. Duane’s daddy was a preacher—not the holy roller kind but something close—and his momma always frowned on us neighborhood kids running around, shooting each other with pretend guns and playing cops and robbers. It was always better when Duane got to play. He was the only one willing to be the cop. It all turned out for the best, though. Duane, he never had much of an arm anyway.

That’s how we measured ourselves back then—by our arms. Not how big they were or how strong, but how far and how fast we could throw a ball. Because let me tell you—back in our old neighborhood, baseball was king and the lot was our castle.

It wasn’t much, that piece of land Maybe half an acre wide and that much long, with a row of big pines marking the left foul line and Mr. Pannill’s house marking the right. The road was our fence.

Come the first day of summer, we were at the lot every morning at 9:00 sharp. We’d play until the sun got too hot. Sometimes Greg’s mom would feed us, and it’d be peanut butter and banana sandwiches in the shade of those pines. Other times, we’d bike it down to the 7-11 and poll what money we had for the biggest Slurpee we could afford. One time Noel said he couldn’t share a straw with all of us, there were too many germs. Don’t you know we let him have it for being such a wuss. Then it’d be back to the lot for more of the same until the sun went down and our mommas started hollering.

The thing about childhood is that you don’t know how special it is until it’s over. All those memories you make will stay in your pocket for the rest of your life, and you’ll take them out from time to time just to handle them and remember. But I think we all understood that back then. I know I did. Even that young and even in the midst of those moment, I knew how special they’d become one day. How long-lasting.

I grew up in that lot. We all played on the Little League teams in town, but whatever we did on the big field didn’t matter. Our reputations—good or bad—were made between the pines and Mr. Pannil’s backyard, and we all knew it. I hit my first home run there, clear to the other side of the road. Broke my first bone in the outfield. I learned about divorce from listening to Noel talk about his parents, and I learned about sex from listening to Jonathan talk about his.

Things like that, they stay with you. They get tucked into your pocket and are never lost.

I learned this at the lot, too—nothing is ever permanent in this world. Even the good things go away eventually. We spent almost nine good summers on that lot and I remember each and every one of them, and I remember how it all began to slowly disappear. Noel moved away. So did Duane, though we never really missed him. The rest of us . . . well, I guess we all just grew up. We got cars and got older. Too old for the lot.

I’ve lost track of most of them now. That happens often in life too, and I think it’s one of the saddest things. There’s now a house where our lot used to be. It’s a nice ranch with a big front porch and flowers planted all the way down the sidewalk, but to me it’ll always be an ugly thing. To me, it will always be the thing that covered over my castle. But I drove down there tonight and just sat. It’s getting on in May and June is right around the corner—just the sort of evening when we’d get together for a few innings. I sat there with the window down and the breeze rustling through those old pines, and I swear I could hear the laughter of five young boys trying to figure out what it meant to be alive. I swear I would hear the ping of the bat. I swear I could hear someone say the next game’s tomorrow.

May 12, 2015

Gettin’ dark

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

I said, “You know Davey, this is why Southerners are stereotyped.”“Don’t know nothin’ about that,” he answered, “just know I gotta clean this. Gettin’ dark, you know.”

I looked at the sunshine splayed over his front yard and still didn’t know what Davey meant by that. So I said, “Just heard a song on the radio that pretty much summed up what you’re trying to do here.”

“Well, if that song was about some guy sittin’ on his porch cleanin’ his shotgun, then I’d say it’s spot on.”

I nodded and said nothing because there wasn’t anything else to say. So I just sat in the rocking chair beside him and watched his grass grow.

In the country a person learns to decipher the hidden meanings found in the common wave. There are many. Depending upon the angle of the arm and the length of the waggle, a gesture by people from their porch can mean anything from “Stop on in and sit a spell” to “If you don’t keep moving, I’m going to shoot you.”

That’s why when I passed Davey Robinson’s house and observed the angle and the waggle of his wave, I stopped. The invite was there, even if the words weren’t.

I climbed onto Davey’s porch and saw the oil and the rags next to his shotgun. Not an uncommon sight in these parts. We take the second amendment with the utmost seriousness. When I asked what he was doing, Davey simply said, “It’s gettin’ dark.”

Davey’s wife poked her head out of the screen door just then. “Hey, Billy,” she said.

“Afternoon Rachel,” I answered.

She looked at her husband. “Davey, this is the last time I’m going to tell you. Put that stuff away.”

“Almost done,” Davey told her.

“Well, hurry up. Caitlyn’s almost ready.”

“What’s Caitlyn up to?” I asked them.

Davey said nothing. Rachel, however, did: “It’s prom night.”

I looked at Davey and smiled. “You’re actually cleaning your gun for Caitlyn’s prom?”

“It’s dirty,” he answered. “I’d be cleanin’ it no matter what Caitlyn’s doin’.”

Uh-huh.

“Honey, please,” Rachel said. “Put that stuff away. If Caitlyn sees you, she’ll go bonkers.”

“Gettin’ dark,” Davey said again.

Rachel rolled her eyes and went back inside, leaving the two of us alone on the porch.

“Caitlyn’s going to prom, huh?” I asked. “Seems like just a few months ago she was still running around here in pigtails.”

“Don’t I know it,” Davey said, running a cloth through the barrel. “I enjoyed every minute of it, too. Guess growin’ up was bound to happen sooner or later, though. This prom thing has been goin’ through her mind for months. Wasn’t much I could do about it.”

“Who’s her date?”

“Guy named Kevin. She’s had him over a few times. Seems like a good enough kid.”

“If he’s a good enough kid,” I said, “then why are you out here sittin’ on the porch with your shotgun? I’m sure they’ll be fine.”

Davey paused with his rag and said, “Fine, huh? Tell me, what sorts of stuff were you thinking about all the time when you were sixteen?”

I thought about that, then said, “Maybe you’d better load that thing.”

“That’s what I thought.”

Caitlyn came onto the porch just then. Her blue dress shimmered in the sunlight, and Rachel had done her hair up into a bun. I understood then why Davey was so nervous. Caitlyn had always been a pretty girl, but right then she looked almost stunning.

“Hi, Billy,” she said.

“Hey, Caitlyn,” I managed.

“How do I look?”

I had to be delicate here. I couldn’t well gush and say too much, not with her father sitting beside me with a shotgun in his lap. But if I said too little, Davey might shoot me anyway.

“You’re easy on the eyes, Miss Caitlyn,” I said. Davey nodded out of the corner of my eyes, and I let out a happy sigh.

“Daddy,” she said, “what in the world are you doin’?”

“Gettin’ dark,” he said.

“I don’t know what that means,” Caitlyn told him, “but please put that thing down before Kevin gets here. For me, Daddy.”

Kevin pulled up in his parents’ car a few minutes later. He was nervous when he saw Davey and me on the porch. He was more nervous when he saw Caitlyn. By the time the two of them had posed for a dozen pictures for Rachel and left, Kevin had nearly sweat through his tux.

Davey and I watched as they pulled away.

“You know,” he said, “I used to come out here on this porch every evening and call that youngin’ in. ‘Gettin’ dark!’ I’d tell her. Now here she is, going out in that dark. And I can’t call her in. Not anymore. She’s gettin’ older. Becoming a woman.”

“Guess so,” I said.

“But I know this,” he said. “She’ll always be my little girl. And I’ll always be waitin’ here on the porch until she comes home.”

May 11, 2015

The happy gas theory

image courtesy of photobucket.com

It’s May, and that means both good and bad things around here. Good in that the school year is almost over for my kids. Bad in that it still quite isn’t. That’s why my son said something about the happy gas last night.

Here’s where he got that:

He was six when he got his tonsils out. It wasn’t the visit to the hospital that worried him. He was okay with the hospital. And it wasn’t even the pain. What worried him the most was the very thing he most looked forward to.

The happy gas.

It’s tough trying to explain a medical procedure to a six-year-old, especially when the ins and outs are pretty vague to his father. I didn’t really know what tonsils and adenoids were, what function they served, or why they were giving him such trouble. But the anesthesia part I knew.

So I told him he got to wear a mask like Batman did and that the air would smell like cotton candy and he’d fall asleep. And while he was asleep the doctors would do their business and make him better.

“You won’t feel a thing,” I told him. “Promise.”

He didn’t believe me.

Experience had taught him otherwise. He’d slept before, and he’d either done things or had things happen that he not only remembered, but felt.

He fell out of the bed twice. Felt that. Bopped his face against the headboard. Felt that, too. He’s also awakened himself by burping, talking, snoring, and coughing. Sometimes all at once.

No way, he thought, no way, would he be able to sleep through someone operating on him.

So I explained that the happy gas wouldn’t just put him asleep, it would put him really asleep, and that the doctor would make sure he stayed that way until everything was finished.

Afterward, once we were home and he was safely on the sofa with his ice cream, I asked him about it.

“I didn’t feel anything,” he said. “I can’t even remember anything.”

And then he said this—“I wish I could have some of that for when I go to school. That way I could just wake up when I got home and I wouldn’t remember any of it.”

Funny, yes. And that definitely pegged him as my son. But he really had a great idea there, at least on the surface. Wouldn’t it be great if we could have some advance warning to the less than perfect things we have to face? And wouldn’t it be great if just before we could put on a Batman mask, breathe some cotton-candy air, and fall asleep through the whole thing?

Yes. It would.

I’ll admit for a while I did my best not to try and poke holes in his Happy Gas Theory. I knew there were some and most likely many. But sometimes we take comfort in those things that aren’t and can never be. That’s what I did while sitting on the sofa with him. I reveled.

But the truth of course was that we had to go through our painful things sometimes. We could slide around some and jump over others, but sooner or later a storm would come that we couldn’t outrun or take cover from, and we were left to stand there in the open under the pour.

Sometimes, that didn’t seem right to me.

It would make more sense to say that if God was there and if God was good, He would take better care of the ones who loved Him. He would make sure our paths were clear. He would prevent the pain and the pour and the doubt. He would take away the fear.

If there was such a thing as everyday happy gas, I thought, then shouldn’t it be God?

Maybe. But maybe that pain and pour and doubt served a purpose that outweighed the need for our happiness. Maybe we needed fear so we could know the value of faith.

Maybe.

I didn’t know for sure, but I thought the odds were good that He’d spared me from a great many troubles in my life without me knowing it. Not happy gas, but maybe something better. And as I looked down and saw my son wince when he tried to swallow, I knew that all the happy gas in the world couldn’t take away all the pain. Some still lingered.

That was true for all of us, I supposed. We were all a collection of bruises and cuts. We all had our tender places.

And I thought that in the end, it was our pain and not our happiness that brought us nearer to heaven.

May 7, 2015

Your mama lied to you

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I was nineteen when I realized my mother had lied to me. It was a difficult thing to accept.

She’d lied to me before, but those were small lies—stuff like Santa and the Easter bunny. Things that seemed pretty darn big at the time but not later on, after the sting of their truth had been replaced by the knowing that I would still be getting presents and candy every year. Those are the sorts of falsehoods most parents tell their children, and I think that’s okay. You don’t get sent to hell for lies like that.

You don’t get sent to hell for lies like the one my mother told me, either. Still, that one stung more than when I found out her and Dad were really Santa and the Easter bunny. Maybe it was my age. People tend to hold on to things tighter as they grow older.

As far as I can remember, the lie started when I got a telescope for my eighth birthday. I’d sit outside for hours every night pointing it at every star and planet I could see. I saw seas on the Moon and rings around Saturn, the spooky redness of Mars and the calming whites of Venus. I was enraptured. To know that there were other worlds aside from my own? That what I saw was only a grain of sand upon the shores of All There Is? Amazing.

I looked at the night sky and saw wonder and mystery and possibility, and I knew my calling in life.

So I told Mom I was going to be an astronaut one day. And she looked at me and smiled and said, “You can be anything you want to be.”

That’s when the lie started.

I believed her. When you’re eight years old, you believe your parents hold the keys to the gates of wisdom. They know everything you’ve done, everything you’re doing, and in many cases everything you’re going to do. So if she said, “You can be anything you want to be,” that meant I was going to be an astronaut. No doubt about it.

I’ve told you where her lie began. Now I’ll tell you where it ended.

It was a year after I’d graduated from high school, and I’d drifted into a job at a local gas station. I was filling up Betsy Blackwell’s car (nice lady, Betsy, though every time I’d wash her windshield she’d turn the wipers on and nearly take off my hand), and up to the pump in front of me pulls a nice SUV. Government tags, with a NASA sticker on the back window.

That’s when I knew.

I was never going to be an astronaut. I’d never have the privilege of riding around in a nice Chevrolet Tahoe with a NASA sticker on the back window, much less seeing the stars up close. I wasn’t smart enough or talented enough. I didn’t catch the breaks. No sir, the only sky Billy Coffey would ever be under was the sky out on Pump 1 at the gas station. And he couldn’t even really enjoy that one because he was too busy trying to make sure Betsy Blackwell didn’t take off his hand with her dang windshield wipers.

I kept all of that to myself until two weeks ago. My family had joined my parents for pizza. One thing led to another and then another, and I mentioned that day at the gas station.

Mom smiled and said, “I figured if I said you could do anything, you’d end up being something.”

Ah. I understood then.

Odds are your mama lied to you, too. She said you could grow up to become a scientist or a baseball player or a musician or President. And in the spirit of transparency, I’ll admit plenty of fathers say the same thing. I know I do.

My daughter wants to be a writer/teacher/archaeologist/scientist/doctor. I tell her she’s aiming a bit too low.

My son’s aspirations are a bit more basic but no less high—he wants to work at Legoland. Yes! I tell him. Why not?

Because they might not be able to do anything, but they can certainly be something.

May 4, 2015

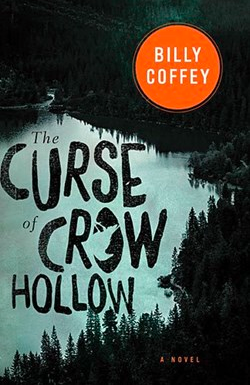

Being cursed

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

I remember the morning he rang the doorbell sometime after one, waking me and the dog and everyone else. Your bell rings that time of night, you know it’s either trouble or bad news.

The kid was no more than seventeen, short and thin and scraggly-looking. I cracked the door and he said, “You seen my dog, Sir?”

I told him I hadn’t and neither did anyone else, whole neighborhood asleep and most of the woods, and a kid who goes around knocking at doors this time of night is looking to get killed, dog or no. Especially a kid stoned out of his mind. He said yessir and sorry sir and went on his way.

I knew where he lived, down the next block in the big red house most of the people around here know to be cursed and maybe is. The family who last moved out of there did so out of necessity. The father gone to jail and the mother gone to rehab, their kids scattered. Even here drugs are plentiful, their pull just as strong as in any fancy city. I knew the father well, watched him turn from aspiring businessman to addict and watched his money disappear right along with his hair and weight and teeth. He told me after he moved in that the builder, a preacher in town, stamped the heads of all his nails with scripture verses. Said it felt good to live in such a house. Might bring luck, he said. It didn’t.

The boy was shooting hoops in the road when I walked by with the dog that next day. He never said a word to me and I never said a word back. My dog growled, but that was all. The boy didn’t know who I was and never had a clue he’d stood on my porch the night before, rousing us all and nearly getting himself shot. His eyes were wide as moons and bloodshot. For every two steps he took, one was a stumble. A man down the street paused in his mowing to say hello. He shook his head at the boy and said, “House got a curse.” I told him about the heads of those nails, how they’d all been stamped with Jn 3:16 and Phil 4:12. The man just chuckled and went back to cutting his grass.

The big news here is the high schooler who got himself killed in a wreck a couple weeks back. Ran his car off the road. There may have been a telephone pole or an old oak involved. No one knows for sure. It was early when it happened, after midnight.

The red house filled up with cars and people, neighbors paying their respects. It’s a tragedy when life stops so short and cuts down someone so young. What went unsaid was how inevitable it all felt. Kid like that, always stoned or high or drunk, the sort who goes out knocking on doors at night. Something horrible was bound to happen. I think maybe so.

I’ve noticed the neighborhood kids giving the red house a wide berth now. They’ll scooch their bikes and skateboards to the other side of the road until that pass that house, won’t use the basketball goal. Word of the curse is getting around. If I allow my backwoods nature to get the better of me, I will admit the whole place does carry a heavy feeling. Like that house is full now but it’ll get hungry again soon enough.

I know that’s not true. Not to say there aren’t such things as curses, because there are. That young man, he was cursed. I watched hundreds of cursed people in Baltimore lately, looting and setting buildings on fire. Saw pictures of cursed cops, too. It’s not limited to place or race or economic standing. That curse is everywhere. It’s even you. Even in me. The more I watch the news and look down my quiet little street, the more I see it. Feel and know it. All it selfishness or apathy or sin, we’re all infected. We see the symptoms, but the curse is something I’ve missed only until recently.

Hopelessness.

That’s it.

That’s how people and neighborhoods and societies act when they have lost their hope. When they look into the mirror or peer into their tomorrows and see nothing looking back. And you know what? Such a thing can’t be fixed with money or policy. Can’t be fixed in Washington.

It has to be fixed in us.

April 30, 2015

On witches and free books

I was only a boy when I learned of the witches, and the picture I’d formed in my mind—something akin to the marrying of the Wicked Witch of the West and the one from those Bugs Bunny cartoons—wasn’t the picture I ended up seeing along that mountain ridge. I saw no brooms or bubbling cauldrons gathered about that shack, only a few drying possum skins and a column of gray smoke from the chimney, an overturned metal pail by the well. Could have been any old body’s shack, really. Except this one wasn’t. Witch lived there.

I was only a boy when I learned of the witches, and the picture I’d formed in my mind—something akin to the marrying of the Wicked Witch of the West and the one from those Bugs Bunny cartoons—wasn’t the picture I ended up seeing along that mountain ridge. I saw no brooms or bubbling cauldrons gathered about that shack, only a few drying possum skins and a column of gray smoke from the chimney, an overturned metal pail by the well. Could have been any old body’s shack, really. Except this one wasn’t. Witch lived there.

“Ain’t no witch,” I said. But I said it low and kept my head that way too, one eye and all my body behind a stout oak some fifty yards away. “That’s just some woman lives there.”

“Ain’t,” Jeffrey said. “Ever’body knows she’s a witch. My mama came up here onced for medicine. Daddy didn’t want her to but she did.”

“Witches don’t give medicine.”

“This one here does. Mama says she makes them in a room in there. Says she prays over all these plants and stuff.”

“Witches don’t pray.”

Jeffrey said, “This one here does.”

That was the first (and only, as it happened) time I visited Jeffrey’s house and the deep woods beyond it, the two of us fast friends that year of first grade, two country boys marooned at a Christian school in the city. Ours was a kinship born of place rather than blood. While the other boys would spend recess putting together Legos and learning the names of the disciples, Jeffrey and I would be out in the mud patch under the basketball goal, digging up worms with our hands. He’d invited me over that Saturday afternoon, saying he had a lot better worms in his yard and more mud too, plus maybe we could shoot his daddy’s .22. Turned out Jeffrey’s daddy was gone that day and the sun had scorched that soft mud to brown concrete. That’s when he asked me—Hey, you wanna see where a witch lives?

“Where’s she at?” I asked, leaning out a little from the tree.

“I don’t know. Daddy says sometimes she turned to a bird or a deer so you can’t tell. He says she’s watchin even when you don’t think she is.”

“Let’s go up there,” I said.

“No way. You wanna get cursed?”

“Ain’t no curse.”

Jeffrey said, “This one here, she’ll curse.”

I’d like to tell you I went on anyway, left that tree and marched right up to the door on that shack and knocked with neither fear nor trepidation. But I didn’t and neither did Jeffrey, because right after that a crow called from the trees and we ran. Ran all the way back and never stopped until we were locked inside Jeffrey’s little bedroom, and then we never spoke about no witch. I never went back. Not to Jeffrey’s, not to that stretch of ridge. To this day, that part of the mountain is one of the few places I’ve tread but once.

That memory is still fresh in my mind all these years later. I can’t remember the name of my fifth grade teacher or exactly whose house I egged when I was seventeen or where I left the keys to the truck this morning, but I can tell you how the sun beat on our backs that day and how the creek water felt like ice when we ran through it hollering and stumbling and that something—animal or witch—followed us through the trees the whole way back from that cabin. I know it.

There are stories here in the mountains, secret ones told by granddaddies on their porches at night when the crickets sing and the moon is high in a dark sky and a Mason jar is in their hands. Tales to make your skin goose up. The ones with demons and angels are good. Ghosts are better. The stories of the witches some say still hide in these hollers, they’re the best.

I guess that’s the biggest reason I decided to add to those best stories with a tale of my own. Not about two small boys that happen to strike the ire of a witch, but an entire town that does the same and what happens when that witch seeks her revenge. About the darkness in us all, and the light.

The Curse of Crow Hollow won’t be out until later this summer, but you have a chance at getting your own copy a bit earlier. I’ll even scrawl my name in it. All you have to do is follow this link and enter your name. Easy peasy.

In the meantime, you keep away from those witches.

April 27, 2015

A question of prayer

image courtesy of photobucket.com

Working at a college has its advantages. Having access to such a big group of smart people comes in handy for me in my daily life, especially when it comes to some of the larger problems I run across. In the years I’ve been there, I have spoken with English professors about writing, political science professors about the goings-on in the world, and religion and philosophy professors about, well, religion and philosophy.

I would call none of our conversations a sharing of ideas. Their words and the diplomas that hang on their office walls are proof enough they are much more intelligent than little ol’ me. I’m good with that. There are advantages to being the dumb person in the room.

So the other day when my mind asked a question my heart had trouble answering, I went knocking on some office doors.

The first chair I sat in was in front of four bookcases that stretched floor to ceiling and were stuffed with titles I could barely pronounce. The professor—smart fella, with a Ph.D. in philosophy courtesy of an Ivy League school—looked at me with kind eyes and asked what was on my mind.

“What’s the point of praying for anything?” I asked him. “I mean, if God knows everything and has a perfect plan, then won’t His plan work out regardless of what I tell Him?”

The professor took off his glasses, rubbed the lenses with a handkerchief. Then he put the glasses back on and looked at the bookshelves behind me, looking for an answer.

“Let’s see,” he told me. He rose from the chair by the desk and brought down one book—this one old, with a worn leather cover and yellowed pages—and then another, this one so new the spine cracked as he opened it.

He talked for ten minutes about free will and time being an unfinished sentence. Or something. My nods at first were of the understanding kind. The ones toward the end were because I was fighting sleep.

I still don’t know what he said.

The door down the hall belonged to a religion professor (Ph.D. again, Ivy League again). I sat in a different chair in front of different books and asked the same question with the same results. More free will, plus something about alternate histories and God “delighting in Himself.”

It wasn’t the first time I’d walked into a professor’s office with one question and walked out with a dozen.

To make matters worse, my mind was still asking that question and my heart was still having trouble answering it.

What’s the point of praying for anything? Because it seems a little presumptuous to ask for anything from a God who already knows what I need (and what I don’t).

I was at a standstill over all of this until I talked to Ralph at the Dairy Queen last night. Ralph doesn’t have a Ph.D., and the only Ivy he knows is the kind that grows on the side of his house. And though far from an expert on matters of the spirit, he does preach part-time at one of the local churches when the regular preacher is sick or on vacation. And since he waved at me and was eating his cheeseburger all alone, I figured what the heck. I’d ask him:

“What’s the point of praying for anything?”

Ralph paused mid-chew. Cocked his head a little to the side. Said, “What kinda stupid question is that?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Just popped into my head the other day. But seriously, why ask Him for anything. And really, why pray at all? If God already knows what’s in my heart, why do I have to speak it?”

Ralph finished his bite, swallowed, then said, “B’cause it ain’t about you, son.”

“It’s not?”

He drawled out a slow “No” that sounded more like Nooo. “Boy, prayin’ ain’t about askin’. Ain’t even about praisin’, really. Nope, prayin’s about you gettin’ in line with God. It’s not about Him gettin’ in your head and heart, it’s about you gettin’ in His.”

Ah.

I left Ralph to his cheeseburger, answers in hand. And honestly, that answer made sense. Because life—better life, anyway—is always about Him more than about us.

And I left with other wisdom, too. The next time I have a question, I think I’ll spend less time in a professor’s office and more time down at the Dairy Queen.