Billy Coffey's Blog, page 9

June 29, 2015

A nation at war

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

Now comes the growing notion that we are at war, a phrase I’ve heard from more than a few these last days. A war fought not with guns and planes but words and ideas, the territory our hearts rather than battlefields. And though both sides cannot agree on much, there is an accord that this war contains both a “good” and a “bad” and that one is either on one side or the other—in this fight, there can be no spectators.Nor can there be hesitation. If you disagree with a man’s right to marry a man or a woman’s right to marry a woman, if you do not believe that a Confederate battle flag is something akin to a Klansman’s hood, then your side is already chosen. Silent introspection is tantamount to cowardice, and for these things the punishment is to be thrown in league with the -ics and -ists. We are branded with the very thing that is now looked upon with contempt—a label.

I haven’t figured out why it’s gotten this way, or if “this way” is really just the way it’s always been. I’m still thinking things through. That’s what we should all be doing now. Not picking fights, not turning to the nearest social media platform to scream and blather. Think.

For instance:

I do not think anyone has a right to be happy. Live even a tiny amount inside this world and you will discover just how impossible and fleeting such a belief to be. This life was not built for happiness, but for the pursuit of it—for each of us to strike out into our days and search for meaning and beauty and purpose. The pursuit of happiness, yes, that is our right. And does that mean same-sex marriage should be legal? I don’t know. Perhaps. Is same-sex marriage and a homosexual lifestyle a sin? Maybe. But if homosexuality is a sin, that makes them like you and me in every way. Like everyone. It doesn’t matter to which sex you find an attraction, we’re all broken. We’re all the same.

The issue with the Confederate flag is an easier one for me. You see them here, flying from rusting poles in the front yards of the mountain folk or billowing from the beds of muddy 4x4s driven by teenage boys. To be honest, the sight of it has always made me uncomfortable. I know its history, and how in the years following the Civil War it was adopted by those who wished to keep down those who should have always been raised up. But I know this as well—I am a proud Southerner. The region of the country does indeed hold many of our nation’s sins, but it holds much more of its graces. I know good men died on both sides of that great national wound, men of courage, godly men. I will tell you that racism exists here, but no more and no less than in any northern city.

I suppose in all of this, what I would like to know is where the line is now that we cannot cross. It seems to me that’s an important thing to consider, for me and for everyone. Because there has always been a line, hasn’t there? A mark upon the boundary of our society’s forward progress that we gauge as that place where, if trampled upon, we risk losing some special part of ourselves. I’d like someone to tell me where that line now rests. I get nervous when it isn’t there, when no idea of constraint is apparent. Jut this morning I read an article from a respected news source calling for the acceptance of polygamy, a notion that has in the last years begun to take hold. Another article extolled the plight of pedophiliacs who now feel left out of this cultural shift, their reasoning being that they can no less alter the object of their sexual attractions than can homosexuals. I wonder how many who support gay marriage would support the legalization of these as well, and if not, what reasons they would offer. Is polygamy the line now, or will that too be crossed? Is it incest? But how many do you suppose would be in favor of that, assuming both parties to be consenting adults? Is not love the most vaunted of emotions now? Does not love trump all?

And of course things have not stopped with the removal of the Confederate flag from state grounds. Chain stores and online retailers have taken up that very mantle, refusing to offer them for sale to private citizens. My own Commonwealth has halted the issue of license plates bearing the seal of Sons and Daughters of the Confederacy. Now there is talk of expanding things further, changing the names of schools and public buildings that bear the names of Lee and Jackson and Stuart and Davis. I’ve even read that some are considering a petition to dismantle the Jefferson monument. Chuckle though you might, what of that other flag bearing stars and bars that has presided over so much bloodshed? What of our country’s own banner to which we stand at parades and ballgames and pledge our allegiance?

Tell me, please: where is the line? Or are we so intent to race forward that we no longer care if there is a line at all? Are the limits of society now -ics and -isms themselves?

I’d like to know. We’re supposed to be at war, you see. And I’m more than a little worried. Because no matter the cause or the combatants and no matter whether the spoils are blood or ideas, the first casualty of any war is always truth.

June 25, 2015

Getting things wrong

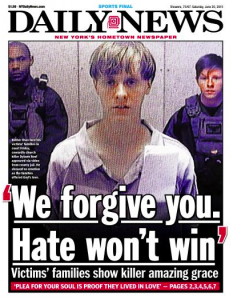

new york daily news photo

It should come as no surprise that the events in Charleston last week are still a big topic here in Carolina. As our vacation has largely removed me from the world beyond sun and sand (as by design), I’m not sure if that’s the case elsewhere. I hope it is. Whenever something like this happens—which we can all agree has become far too often of late—the first thing I often hear is something along the lines of, “This country needs to have a honest discussion about race.” While I agree wholeheartedly, I’ve often wondered what an honest discussion would mean. And I guess I’m not the only one, because that conversation has yet to begin.What’s getting the most attention around here isn’t the act itself, the murders, nor the racism that sparked that act, nor even the now national push to have the Confederate flag removed from all state government buildings and grounds. No, people here seem focused upon the ones who deserve the focus: the victims. Namely, how those victims treated the young man who became the instrument of their deaths. How this young man told the police after his capture that he almost didn’t go through with his plan because of the kindness shown to him by those in the church.

That would be amazing if it were not so sad.

He had an idea in his head, you see. A belief that blacks were less, that blacks were a danger, that blacks were responsible for so much of the evil in the world that they must be erased in order that the rest of us could be saved. That belief had been ingrained over the years by a variety of sources, strengthened and ingrained to the point where it became, to him, fact. And yet reality proved something different. Once he sat down with them, listened to them, heard them pray and speak, once this young man knew their hearts, some part of him understood that what he had come to belief was false. These were not monsters, these were people. People like him.

And yet even that knowledge wasn’t enough to keep him from drawing a weapon and killing nine of them. Belief proved stronger than reality in this case, just as it does in most cases. That’s what people here are grappling with most, and what I’m grappling with as well.

These first few days at the beach have given me an opportunity to do what life in general often denies—the chance to simply sit and think. What I’ve been thinking about lately is this simple question: Have I changed my opinion on anything in the last five years?

I’m not talking about little things, like the brand of coffee I drink or what my favorite television show is or where I shop for groceries. I mean the big things, like how I think about life or God or my place in either, and how I see other people.

Have I changed my beliefs in any way toward any of those things? Have I altered my thinking, or even tried? Have I even bothered to take a fresh look? Or has every idea and notion I’ve sought out only cemented what I already knew and believed to be true? Those are important questions, because they lead to another, larger question that none of us really want to ask:

“Have I ever been wrong about anything?”

Have I?

Have you?

Have we ever been wrong about who God is? Wrong about politics or social stances or what happens when we shed these mortal coils? Because you know what? I’m inclined to think we have.

None of us are as impartial and logical as we lead ourselves to believe. Often, what we hold as true isn’t arrived at by careful thought and deep pondering, but partisanship and whatever system of ideals we were taught by parents or preachers or professors. That creates a deep unwillingness to refine what positions we hold, and that unwillingness can lead to laziness at least and horrible tragedies at worst.

Whether we hold to the Divine or not, we all worship gods. Chief among them are often our beliefs themselves, graven images built not of wood or stone but of theories and concepts. We follow these with blind obedience, seeing a desire to look at and study them as tantamount to doubt or, worse, an attempt to prove them the paper idols they are. Yet truth—real truth—would never fear questioning, and would indeed always welcome it. That’s why we owe it to ourselves to test our opinions. We are built to seek the truth, wherever it may lead.

June 22, 2015

Shutting out the world, if only for awhile

I write this in the early afternoon of this past Friday, looking out the window toward mountains shrouded in summer haze. It’s quiet here, always a blessing, even as the world burns slow in other parts of the country. Sad as it is, I suppose I can use “burns” both literally and figuratively.

I write this in the early afternoon of this past Friday, looking out the window toward mountains shrouded in summer haze. It’s quiet here, always a blessing, even as the world burns slow in other parts of the country. Sad as it is, I suppose I can use “burns” both literally and figuratively.

Tomorrow morning, my family and I will pack up and trade these mountains for the Carolina coast. My job allows one vacation a year, and I mean to use every bit. It’s always a scramble to get away, part stress and part strain and an overwhelming need to escape, even if some part of you understands that you’ll eventually have to come back again. I can say I always look forward to vacation week. I can say I’m looking forward to this one a little more.

Because I’m tired, you see.

Of everything.

This week has brought news of another shooting, this one at a church in Charleston, claiming nine lives. Aside from the hurt and anger and outrage, I don’t have anything to say. Still trying to process it, I suppose. Still trying to take it all in and turn it over in my heart and my thoughts, still trying to figure out if I should do such a thing or even if such a thing is possible. I don’t know that it is. Some part of my says no, that if I could understand the whys of what would lead such a young man to perpetrate such an evil act, I should then worry much more about myself than about the state of the world. But another part of me begs a yes to that question, at least partway—it may not be possible to understand or healthy to ponder why, but an attempt at both is necessary. Too often, we are confronted by the reality of evil only to turn ourselves away. It scares us (as it should), makes us uncomfortable (as it should), but that’s not the worst that evil inspires. To gaze upon it is to see into a mirror badly bent. It is to behold what we are all capable of, should things come to it, and to know how far we have yet to go. It’s heartrending and soul crushing, and yet the alternative—blaming parents, blaming guns, blaming culture, or ignoring it all together—is much worse.

There was a time not long ago when these reminders would come sporadically, spread out over months or even years. But now they seem to come in a much quicker fashion, don’t they? Maybe it’s the news, now on twenty-four hours a day. Maybe it’s a byproduct of living in an age of constant social media, a heartrending and soul crushing thing in itself. I don’t know. All I do know is what I’ve said—I’m tired.

On my way to work this morning, I stopped at the town BP for gas. A tractor pulled up to the pump beside me, the farmer straddling it already dirty and sweating from the fields. Our talk wound itself around to Charleston. He shook his head, eyes wide and mournful. Said he hadn’t heard a thing about it.

I wondered how that was possible, then stared at that old John Deere. Here was a man with neither time nor inclination for the wider world. Long days outside at the farm, tending to cows and the rising corn, short nights curled in bed, the weather report better told by the winds and the clouds than by some man in a suit coming through a television screen. Of course he hadn’t heard. How would he?

I felt bad, thinking I’d ruined his morning with the news. The way he pulled off told me he took things hard. Church is supposed to be a place of love. Where you’re safe. He probably went home thinking that’s the last time he’s coming to town. Ain’t nothing good away from the farm. Whole world’s going to hell, already halfway there.

They say ignorance is bliss, and they mean that bad. I would agree. Shutting yourself off from the world, refusing to find out what’s going on and to care about it, is a lot of what’s behind the problems we face. But I still think about that old farmer on his tractor, tending to his work as the world flies past unseen and unknown. I think about long walks on an empty beach and tides that carry your troubles away. And I think maybe that’s what we all need right now, if only for a little while.

June 18, 2015

Holy vandals: Changing things for the better

These have been sprouting up around the neighborhood lately. I’ve counted at least half a dozen on my walks, scattered about in some unlikely places: at the end of sidewalks and the tops of porch steps, on the ledge of a sandbox and in the hollow of a Japanese maple. The one you see in the picture is currently resting at the base of my neighbor’s mailbox.

These have been sprouting up around the neighborhood lately. I’ve counted at least half a dozen on my walks, scattered about in some unlikely places: at the end of sidewalks and the tops of porch steps, on the ledge of a sandbox and in the hollow of a Japanese maple. The one you see in the picture is currently resting at the base of my neighbor’s mailbox.

The rocks look to be colored with some sort of paint — not sprayed on, but brushed. Bright colors, too. No earth tones with these. They’re lime and pink, magenta and electric blue. Definitely not meant to stay hidden. These rocks scream out to be found. To be seen, and immediately.

The ribbons and quotes are as different as the coloring. Some I recognize but many I do not, poets and writers and philosophers from ages past, their words serving as a kind of immortality. I like this. In a time when the Gone is frowned upon in favor of the Just Ahead, it’s nice to be reminded that the world may always be changing but people never do. What was true in the Bronze Age or the Renaissance or in Victorian England remains true now, and will be true still upon some dim tomorrow. The times may evolve, but not the human heart. As a race, we are as good and as evil as we have always been and will always be.

I didn’t get that from one of the cards tied to the rocks. That’s just me talking.

I was lucky enough to catch someone finding their own message, this the day before yesterday while walking the dog. An elderly woman in her front yard, pail and trowel in hand, aiming herself for the rose garden in the middle of her front yard. She stopped with a suddenness that made me think she’d stumbled upon a copperhead searching for some sun. She picked up a near circular stone, bright yellow with a red bow. I saw her lips move as she read the note. Saw the edges of her mouth curl upward.

On my way back, I took a detour through her grass. The rock was still there, placed by her in a position of prominence in the middle of the garden. In black script so carefully written that it appeared printed from a computer was this quote by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.: “The Amen of nature is always a flower.”

I’m going to say that I think I have a pretty good idea of the ones behind all of this. These holy vandals, these ninjas of comfort and inspiration. I will guard their secret. Some day they may be unmasked, but never by me. In the meantime I will feign ignorance, and when my neighbors come calling, scratching their heads and smiling in something very much like wonder, I will say I have no earthly idea where the rocks came from or who put them there. I’ll even show them my own, the orange one I found against the side of the shed this morning. The one with the Robin Williams quote that says, “No matter what people tell you, words and ideas can change the world.”

I guess that’s what it’s all about, isn’t it? Changing things for the better. I don’t know of a single person who doesn’t pine for that, and to play their own part in it. It’s why I write books and why my wife teaches school, why my mother worked as a nurse for thirty years and my father drove a truck almost forty. I would even say that’s what drives you as well — to make things better. For the world, your family, yourself. I suppose in that respect, we’re not so different than God is to us. We love things too much to keep them as they are.

But here’s the thing that always seems to trip me up: those momentous events that are told and retold in books and movies and classrooms often began not with a rushing wave, but a ripple. Something tiny. Something almost inconsequential.

Something like a bunch of painted rocks.

Big things don’t always make a change. Most times it’s more little things done over and over again, laid out one after another, marking a path that leads us on. We don’t have to do great things to bring sunshine to the world. All it takes are little things done with great hearts.

June 15, 2015

Darkness and light

A big part of my duties around the house involves taking care of those things everyone else finds objectionable. Getting rid of any creepy-crawly beyond the size of a fly? My territory. Also most accidental discharges by the dog. I’m the Poop and Pee guy.

A big part of my duties around the house involves taking care of those things everyone else finds objectionable. Getting rid of any creepy-crawly beyond the size of a fly? My territory. Also most accidental discharges by the dog. I’m the Poop and Pee guy.

I am also, as it turns out, The One Who Gets The Clothes Off The Line When They’ve Been Forgotten And It’s Close To Midnight guy, which is what I’m doing now. It’s a new one for me, and one that never would have happened if my wife hadn’t gotten up a little bit ago and glanced through the window into the backyard.

Can’t leave the clothes on the line, she said. The dew would get them by morning; she’d have to wash them again.

Both of the kids were in bed, though I’ll add that it wouldn’t have made much of a difference if they’d been awake. My daughter is thirteen and my son is eleven (going on twenty), but neither one of them do the dark. Nor, for that matter, does my wife. She said she would be happy to take the clothes off the line. All I had to do was stand guard at the backdoor.

So: me.

She’s standing at the backdoor now. Keeping watch, I suppose. You’re asking what exactly my wife is keeping watch for? Well, I suppose it’s any number of things. Our neighborhood is large (too large, if you’d like my opinion), but our house abuts thirty thousand acres of woods and mountains that served as the inspiration for a place called Happy Hollow in my books. Talk to many around here, they’ll warn you away from those woods at night. There are stories. But aside from tales of ghosts and unknown beasts, there really are things around here that creep in the night and are best left alone. Our neighbors woke one morning not long ago to find a bear on their front porch. I’ve killed too many copperheads in our creek. So, yeah. Maybe that’s why my wife’s standing on the other side of the screen while I take down these clothes.

I told her there’s no need to watch. She knows that. She also knows the dark doesn’t bother me, that in fact I’ve come to find a feeling in it that, while not comfort, is something akin to it. I don’t mind the dark. That’s when I can see the stars.

They’re out here tonight, right over my head. Bits of light tossed into the sky like millions of tiny dice, planets and suns and a band of the Milky Way all keeping time to some celestial music that beats not in the ears but the heart.

Growing up, I learned to pray in the dark. I’d go outside every night and look up at the sky, and if there were stars I’d start talking. If there weren’t, I’d just listen. I learned a lot that way. It’s highly recommended.

Almost done. Half the clothes are off now. I pull the pins away and put the pins in the cloth sack hung on the line, fold each article of clothing and place it in the basket. I’m assuming my wife is telling me to hurry up. I don’t, even though there’s something in the bush nearby. Maybe a possum. Or a rabbit. Too small to be a bear. Could be one of those adolescent Bigfoots I heard about a few weeks ago. Seems a guy was fishing out in the woods and came across an entire family. Swears it, and never mind that he was drunk off his rocker at the time. Probably isn’t one of those in my bush, but I still catch myself wondering what I’d do if it was. Talk about a story.

Speaking of which, I had someone last week ask me why my stories had gotten darker as the years have trundled on. I didn’t know how to respond to that. I suppose they have (The Curse of Crow Hollow will be out in less than two months, and it’s both my best so far and a far, far cry from my first novel), but I can’t really speak as to why that’s the case. I suppose if I had to, I’d say it’s just me getting back to my roots. My kin have long told stories about those caught along the thin line that stretches between worlds, and the darkness that lurks both there and inside the human heart. Besides, it’s light that I really want to write about. Where better to see that light than in a bit of darkness?

And really, we’re all living in a kind of darkness, don’t you think? This great world we inhabit, all the fancy toys we carry with us and all the knowledge we possess, doesn’t change the fact that there are dangers everywhere, hungry things lurking about, and whether it’s cancer or terrorism or crime or simply the slow winding down of life, those things are always close. That’s what makes living such a hard thing, and what makes all of us so courageous.

There, done. The last pair of jeans, the final T shirt. My wife can go to bed now knowing there won’t be any clothes to wash again in the morning. I take the basket and make my way to the porch, casting one last look at all those stars. Pausing to say Thanks, for everything. At the door, I catch a glimpse of two glowing eyes from the bush. And you know what? I say thanks for that, too.

June 11, 2015

One unselfish act

image courtesy of photobucket.com

It is a known fact that one of the main reasons why I’m friends with Tommy Fuller is because of what’s in his backyard. I realize this paints me in somewhat of a bad light on the surface. In my defense, though, Tommy is not only aware of this, he’s fine with it. He figures it’s a trade off. One of the main reasons he’s friends with me is because he borrows my golf clubs.

It’s a good deal as far as I’m concerned. Tommy’s a great guy. Even better than that is the fact that he has an open door policy when it comes to his backyard. I can visit any time I like, even if he isn’t there. The kids are welcomed, too. Sometimes we even make an afternoon of it. They can jump on his trampoline, and I can climb his oak tree.

Tommy has one of the biggest back yards in town with THE nicest tree smack in the middle of it. Tall and full, and the limbs are spaced just far enough apart to let through the perfect amount of sunlight. Home to squirrels and robins and friendly bugs. It’s the sort of tree that belongs more in a Disneyland attraction than a redneck’s backyard.

The farm has been in the Fuller family for generations, and it’s one of the oldest in the area. Tommy’s grandfather and father were both raised there, as was he. When his mother passed away ten years ago, he moved in and got control of the property. And when the time comes, Tommy will pass the torch onto one of his sons. In the Fuller family, the circle never ends.

There aren’t many properties around here that carry charm like that anymore. Most of the farmers in town have sold their acres of fields and forest to developers, giving in to the promise of a life of comfort rather than sweat. Tommy won’t bow to that false promise. There will be no subdivisions on his land. Not because his principles are too strong or his faith too unwavering, but because of that tree.

Because it is quite literally a family one.

Look on the back side and you can see the faint outlines of his father’s pledge to his mother back when they were mere boyfriend and girlfriend. BF Loves KT, it says. Tommy says his mother and father would sit beneath that tree often during their courtship, resting in the shade of their love.

And on the other side are the marks Tommy carved to his own bride to be, pledged in wood on the night they became engaged.

In the upper reaches of the oak is a tree house that Tommy built for his boys. Though worn, it’s still in good shape. He sees his future grandchildren playing pirate there.

But the best part? The best part isn’t the tree, It’s the stone plaque beside it.

03 MAY 1901, it says.

According to Tommy, his great grandfather planted that tree himself on a calm spring afternoon. Dug the hole, gently placed the seedling inside, then covered and watered it. And after that he stuck his shovel in the ground and just smiled. Tommy remembers his grandfather saying that it was a strange smile, part sadness and part joy. The sort of smile a dying man wears. Tommy doesn’t know what was wrong with his great grandfather, just that he didn’t have much longer. And he didn’t. If you drove over to the church nearby you would see that the date of his death and the date the tree was planted are less than a month apart.

It’s amazing that something so small and fragile could grow into something so large and strong. But love is like that. Hope, too. That’s what I think about when I sit in that tree.

And I also think about this—on a calm spring afternoon more than a century ago, a dying man’s last act was to plant something he would never be able to see grow. He would never get to rest in its shade or climb its branches. He would never get to enjoy it, but he planted it anyway. Not for himself, but for those who would come afterward.

I like that idea.

According to some, there is no such thing as an unselfish act. But this comes close. And I think that for all the lofty goals the human spirit can strive to accomplish, this is the most noble—that we spend our days in pursuit of something that will outlive us. That we plant seeds destined to bless not only ourselves, but generations.

June 8, 2015

Errant negotiations

image courtesy of photobucket.com

My children are arguing.

Not exactly breaking news, of course. Kids fight. It’s one of those givens in life that are about as surprising as the sun rising in the morning or a hot day in July. Blame it on summer vacation. I think they’re just tired of each other.

I’m not sure what caused the conflict; I just got home from work and caught the tail end of it. Something to do with Legos, from what I gather. Or an errant water balloon. One of those. Or maybe it was something else all together. You never can tell with kids. Kids can argue about anything.

I get caught up to speed by my wife, who doesn’t really know what the conflict is about herself. She was in the kitchen fixing dinner at the time. There was just a thump and a scream, followed by yells and accusations. That was enough for her. She sent both of the kids to their rooms to calm down.

I walk down the hallway to their bedrooms to say hello and gauge the amount of weeping and gnashing of teeth and find the Go To Your Room rule broken. My son is in my daughter’s room. She’s sitting Indian-style on the bed. He stands in front of her. Both are talking. Each have their arms crossed.

These are some serious negotiations, which is why I don’t barge in, make a Daddy Arrest, and charge them with not abiding by their mother’s wishes. It isn’t often that I have the opportunity to listen in on my children’s discussions. More often then not, they clamp up as soon as I enter the room and offer little more than, “Yes, Daddy?” I get plenty of opportunities to learn about what they think and believe in my conversations with them, but most times that seems like only half the story. What you think and say when your father or mother is around is often quite different than when it’s just you and a sibling in the room.

So I put my daughter’s bedroom wall between us and listen.

“I didn’t hit you on purpose,” my son says.

“Yes you did,” says my daughter. “You liked it. I saw it in your eyes.”

“You can’t see in my eyes. And you should have gotten out of my way.”

“I didn’t want to. It’s MY house too, you know.”

I’m not going to play anymore until you say you’re sorry.”

“Well I’M not going to play anymore until YOU say YOU’RE sorry.”

“All I was trying to do was get a Lego.”

“Well all I was trying to do is get a Lego, too.”

And on. And on and on.

Rather than interrupt, I decide to let them be. My kids will work this out, they always do. And then things will be fine until the next skirmish. I suspect my home isn’t much different than any other in that peaceful times are merely those few quiet days between wars of both opinion and blame.

In the meantime, I retire to the television and the evening news. Which, by the way, is much the same news as yesterday and the day before. Still the arguing, still the blaming. The system is broken, they say. I’m inclined to agree. Especially since the people who made the system are broken as well.

A commercial appears, one of those thirty-second spots about scooters old folk can ride around in to make themselves feel useful again (free cup holder included!).

The news is back, this time given by a pretty blond rather than a non-pretty man, as if bad news could seem a little better if she is the one telling it. She wonders aloud how we fix the problems in Washington, then poses the question to an educated man in a pair of thick glasses.

That’s when I turn the television off. I don’t need to listen to a pretty blond or an educated man to know how to fix things. I already know fixing them is pretty much impossible.

Because in the end, we’ll always prefer arguing rather than talking.

And we’ll always choose stubbornness over compromise.

We’ll always strive to reinforce our own opinions rather than admit those opinions might be wrong.

Call me pessimistic, that’s just how I see it.

Because our politicians really are representative of us all, if not in political philosophy than in brokenness.

Which means the adults we send to Washington aren’t really all that different than the kids we send to their rooms.

June 3, 2015

A history of violence

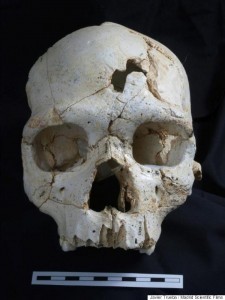

There is a cave system in the Atapuerca Mountains of Spain that contains a bit known as Sima de los Huesos — “Pit of the Bones.” I’m sure it looks as wonderful as it sounds. Researchers and paleontologists have been combing through the pit, doing what researchers and paleontologists do. So far, they’ve discovered twenty-eight sets of remains dating back nearly half a million years. One particular set of remains stands out: the skull of a young adult, found in fifty-two pieces. Scientists pieced the skull back together and discovered something unexpected—two cracks, just above the left eye. The evidence was plain enough and old enough to define the skull as “the earliest case of deliberate, lethal interpersonal aggression in the hominin fossil record.”

There is a cave system in the Atapuerca Mountains of Spain that contains a bit known as Sima de los Huesos — “Pit of the Bones.” I’m sure it looks as wonderful as it sounds. Researchers and paleontologists have been combing through the pit, doing what researchers and paleontologists do. So far, they’ve discovered twenty-eight sets of remains dating back nearly half a million years. One particular set of remains stands out: the skull of a young adult, found in fifty-two pieces. Scientists pieced the skull back together and discovered something unexpected—two cracks, just above the left eye. The evidence was plain enough and old enough to define the skull as “the earliest case of deliberate, lethal interpersonal aggression in the hominin fossil record.”

In other words, scientists have dug up the oldest murder victim in history.

The person’s injuries (the researchers were unable to determine if the skull belonged to a male or female) seem the result of two brutal blows, each from a slightly different angle but each more than capable of puncturing the brain, the murder weapon most likely being a spear or an axe. We’ll never know which; the skull—or what is left of it—has been at the bottom of a forty-foot shaft for 4,300 centuries. Dropped there by either family or the murderer(s), creating at once both the earliest known funeral and the earliest known crime scene.

Think about that for a minute. Being murdered like that and then dumped in a hole, forgotten for hundreds of thousands of years. No name, no story, at least none we can know. And lest you fool yourself into thinking this sort of thing really doesn’t matter at all, I’ll remind you this person had a father, a mother, likely siblings. He or she may have been in love, may have been married, may have even had children of his or her own. The brain encased in this broken skull was just like ours, capable of higher thought and language. It could ponder and wonder. It knew love and fear.

I bet he had dreams that weren’t so different from our own, a nice place to live, some sort of comfort, peace. I’d wager she had thoughts of growing old, plans for the future. Unfortunately, that wasn’t meant to be. Somehow, someway, whether his fault or hers or whether another’s, death came with horrific violence.

Sad, if you ask me. No matter who it is or how long it’s been.

But here’s the thing that stuck most with me: we’ve been doing this sort of thing to each other for a very long while. We’ve been bashing skulls and chopping off limbs and taking lives since the beginning. We like to think of ourselves as evolved, sophisticated, mature. We’re not, at least not deep down. Deep down we’re still savages, savages whose better natures are constantly pushed aside for what we want, when we want, and exactly how we want it. If we could somehow interview the person responsible for the two holes in this skull, my guess is he or she would sound very much like anyone on the news: “It’s not my fault.” “They deserved it.” “I couldn’t help myself.”

We’ve come a long way in the last 430,000 years. Made great strides, done amazing things. In that time we’ve mastered wind and fire and water, but not ourselves. We’ve plumbed ocean depths and the tallest mountains, but we have yet to discover just how low or high we can all reach. Sometimes, I wonder if we ever will.

June 2, 2015

The poor folk

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I ask Larry if he’s still watching over the poor folk every time I see him, and every time he says yes. He says yes and then offers me one of those nods that are accompanied by pursed lips. You know, the kind of expression that means it’s tough to look but you have to anyway. Someone’s got to watch over them, Larry says, and it might as well be him. Especially since he was poor once.

He’ll tell me he still watches over them from the same place, right across the river from the big building where they like to gather. Not a pretty sight—Larry will tell me that too, and always—but one worth watching nonetheless, if only for the education the sight provides. “There but for the grace of God,” he’ll say, and then he’ll nod and purse his lips again.

He says there have been times in the past when he’s taken the bridge across the river and gone to see them. Or tried. The poor folk will sometimes entertain Larry’s presence for a while. He was after all one of them once, and the poor folk are mannerly on the outside even if they are lost inward. They’ll say hello and how-you-doing and come-on-in. Larry will hello them back and say he’s fine, just fine. But he never goes in the big building. He’s been in there too many times in his life, he’ll tell me, and he’s seen all there is to be seen. I guess that’s true enough, but sometimes I think Larry’s afraid he’ll catch the poor again, like it’s some sort of communicable disease spread by contact.

Better than driving across the bridge to say hello is to stay on the other side of the river and watch. That’s what he tells me. It’s sort of a warning, though it’s one I don’t need. To be honest, I don’t have much of a desire to be around the poor folk. I like it where I am, right here with Larry and the rich people. Maybe I’m afraid I’ll catch poor, too. Maybe deep down I think they’ll sneeze on me.

Larry says he has God to thank for being rich now, and when he says this he won’t nod and purse his lips. He’s much more apt to pat the rust spot on his old truck—a ’95 Ford from down at the local car lot, which was a steal at $5,000—or take off his greasy cap as a sign of respect for invoking the Almighty. Yesir, Larry will say, God stripped away all of his poor and made him rich. I guess that’s nothing new in a time when a lot of people think God’s sole purpose in the universe is to shower down hundred dollar bills on everyone who’s washed in the blood of the Lamb.

Sometimes I’ll ask him if the people who gather at the big building across the river are all poor. Surely there are a few rich ones mixed in. He’ll tell me yes, there are a few rich ones, but they’re rare. Once he said I’d just as soon go in the big building looking for a unicorn as I would a rich person. I laughed at that. I think it was the way he’d said it—“Yooney-corn.”

Still, curiosity kicked in. I had to find out for myself.

I drove up to the big building one town over, careful to park across the river as Larry suggested. Lines of cars filled the parking lot—from my vantage point, I saw seven Mercedes, half a dozen BMWs, and three Jaguars. I watched patrons adorned in fancy dresses and pressed suits go in for dinner, watched the golf and tennis players come out.

Larry’s poor folk.

He was once one of them (it was the Mercedes and the golf for Larry, the fancy dress for his wife, and the tennis for his kids). They were at the country club five days a week and sometimes six, depending on how busy they all were. He’ll say he swore he was rich. But then came the recession followed by the job loss, and suddenly the Mercedes was gone (replaced by the truck, a steal at five grand) and so was the country club.

That’s when God showed Larry that what he thought was riches was really poverty. That’s when Larry found that wealth is better measured in love and family and simple things.

Larry says he never knew how poor he was because all that money got in the way. Now he says he’s the richest man in the county.

I think he might be right.

May 28, 2015

2015: Anywhere but here

These days it’s not only the bright colors and long sunshine that tells me summer is close; the cars and trucks tell me, too. Specifically, the back windows on the rusting hoopties the neighborhood teens drive. That’s where the messages go, whether in soap or, more often, traced through a layer of dirt and pollen with a finger.

These days it’s not only the bright colors and long sunshine that tells me summer is close; the cars and trucks tell me, too. Specifically, the back windows on the rusting hoopties the neighborhood teens drive. That’s where the messages go, whether in soap or, more often, traced through a layer of dirt and pollen with a finger.

SDHS 2015, they say.

GRADUATE!!

And this one, seen often from my porch in the last evenings, which sums up the general thinking of anyone between the ages of sixteen and eighteen—

ANYWHERE BUT HERE

I get that, I really do, at least in some way. I was eighteen once. Yet while my friends for the most part succumbed early on to the virulent strain of wanderlust that infects the young, I remained largely unaffected. The talents I’d grown up believing would carry me away from the valley and into the wide world were gone by the time I became a senior, and I had made peace with that long before I walked off the stage a high school graduate. By then, I no longer wanted to leave the mountains, had no desire to go off in search of anything. I’d already found what I needed right here. Here was—is—home, this speck sunk deep into the Blue Ridge that I share with deer and bear and coyote, rivers as clear and smooth as glass, fields golden and peaceful in the sun, and where the bones of my kin are buried, their souls sung to heaven.

Why would I ever want to leave such a place, if only for a while?

But as I said, I get it: the wanderlust. Though much larger now than the summer I graduated, ours is still a small town. Little happens here. In face, outside of a skirmish in the early spring of 1865 and an Indian war in some dim part of time (the evidence of both still here if you know where to look), nothing much has ever happened here. We are generally lower-middle class, blue collar, and Christian—farmers and factory workers and teachers who slog through five days so we can catch our breath for two. Sounds fine if you’re forty-something and want a peaceful place to roost your family. Not so much when you’re eighteen and suddenly, wonderfully, free. When you’re that age, wherever you are isn’t good enough. What you crave is adventure. What you dream is ANYWHERE BUT HERE.

Sometimes I think that describes us all to some extent. We’re all searching for a way to get ourselves over the hump, that one special thing that would bring a sparkle to the dullness that seeps into every life. I guess in that respect we could all be said to wander, even if we never venture beyond our doors.

I’m not the only member of the class of 1990 who’s stayed and carved out a life in this quiet corner of the world. Plenty more stayed, too. Those who went on to college and career have been flung not only across the country but also across the globe. I talk to some of them upon occasion, catching up. And each time, no matter what great things they’ve done or what magical places they’ve seen, I’m always asked the same question:

“How’s home?”

Because in the end it doesn’t matter where they all have gone or what they’re doing, this little town of field and mountain and holler remains that. Home. This place they once could not wait to flee and forget is now the place they know they can run back to if the world ever bared its teeth, and what dark memories remain of their former lives here have gone soft at the edges.

If I could say one thing to all those pending graduates, I think it would be that. I would tell them to go, light out into the territory, seek what treasures wait just over the horizon. But as you leave, know that the traveling is lighter if you carry home in your heart.

And know that should your eyes ever turn this way again, we’ll be waiting.