Billy Coffey's Blog, page 7

September 29, 2015

Back in the Summer of 69

image courtesy of google images

That dry season I told you about a couple weeks back is nothing more than a memory now. It’s been raining here for so long that people can’t even remember when it began. Days upon days, one long and soggy line. The creeks are full and the grass is back; everywhere you walk makes a squishy sound. No downpours, at least not yet. Just that steady sort of falling water that starts out making you feel comfortable and ends up sinking into your bones. The ground is saturated now. I hear more rain is coming, the kind that keeps interrupting the radio with screeches and buzzes and warnings of rising rivers and washed out back roads.

Whenever these parts are hit with this much rain, invariably someone will mention 1969. Usually it’s an old timer, like the ones who hang around down at the hardware store or on the benches outside the 7-11. You’ll say hello to them and keep going for your new hammer or a bottle of Mountain Dew, and they’ll draw you in. Old timers like that have all the hours in the world to talk. And since so many of them have spent their lives coaxing food from the black dirt on their farms, weather is their specialty. Weather and memory.

“You think it’s wet,” they’ll say, “you don’t know nothing. You shoulda been here in ’69.”

I wasn’t, of course. I missed what happened here back then by three years. But I know many who were not so fortunate.

In August of that year, a tropical wave formed off the coast of Africa and swept westward along the 15th parallel into the lesser Antilles, where it became a hurricane south of Cuba. The National Weather Service named it Camille. It made landfall on August 18, crushing Waveland, Mississippi. From there Camille tracked north, through Tennessee and Kentucky. Then it veered hard right through West Virginia and into the Appalachias, where it ran smack into Virginia’s Blue Ridge.

That was August 19, 1969.

Nelson County, just over the mountain from us, suffered worst. The rains came so hard and so utterly fast that it defied human reason and nearly touched the Divine. Some even called it judgment for a people who had strayed from the Lord. Houses were swept away, cars tossed like playthings. Whole towns and families lost, disappeared. The very contours of the mountains were shifted and changed by walls of mud. In the end, twenty-seven inches of rain fell in less than five hours. The National Weather Service stated it was “the maximum rainfall which meteorologists compute to be theoretically possible.”

One hundred and twenty-three people perished. Many more were never found. To this day, their bones lie somewhere among the fields and vales. It was estimated that 1 percent of the county’s population were killed that day. Most perished not by drowning but by blunt force trauma, the water throwing them into the nearest immovable object.

The destruction and loss of life was so complete that Camille was stricken from any further use as the name for a hurricane. People here won’t even utter the word. It’s always The Flood. Nothing more than that needs saying.

Then again, maybe I’ll say a little. Because what gets added on the end of that nightmare across the mountain was the grace and kindness shown after. The government appeared en masse in the days and weeks following the storm to clean up and rebuild, but it was the untold thousands of volunteers who did most—the farmers and mountain folk and more church groups than anyone could count, people who knew those mountaintops and hollers well. My daddy and granddaddy were among them. They moved slow through all those shattered homes and marked the ones that had become tombs. They carried pistols in their hands because of the million snakes that had been washed from their dens.

For years Grandma kept a picture she’d taken of the sky on the day the Camille left on her mantle. It was black and white instead of color, but you could still see how black the sky looked, how evil. But you could also see as plain as day how in the middle of that picture the clouds had parted in the perfect shape of an angel to let the sunshine through.

It wasn’t the first time tragedy and hardship had visited this part of our world. It won’t be the last. But if there is any comfort to be had in such times, it is the same comfort that was found in the late summer of ’69—God is still there, still watching, and there will always be good people who will rush to your aid and help you repair what life has born asunder.

September 23, 2015

Power to the people

I’ve seen him off and on for the past three weeks, a Monday morning here and a Thursday afternoon there. From what I can tell, there is no set schedule. Maybe it only happens when the mood strikes—when the anger grows too hot or the despair sinks too deep. I’m not sure. But I’ll give him this: he’s dedicated, despite it all.

I’ve seen him off and on for the past three weeks, a Monday morning here and a Thursday afternoon there. From what I can tell, there is no set schedule. Maybe it only happens when the mood strikes—when the anger grows too hot or the despair sinks too deep. I’m not sure. But I’ll give him this: he’s dedicated, despite it all.

He was standing on the corner the first time I saw him. Technically speaking, it was still the gas company’s property, though the spot he’d chosen was on the outermost edge where two main roads converge. To be more visible, I thought. To make sure he was seen.

Older gentleman, dressed in pressed khakis and a brown button-up. Thin, white hair swept to the side in the front, trying but not managing to cover a bald spot. The breeze whipped it, giving the appearance of snow falling up. The sign he held was as large as himself. Scrawled on both sides was a long list of grievances against the gas company itself.

Racism, discrimination, and greed were the only three I could make out that first day. Since then, I’ve managed to catch sight of price gouging and lying as well. The rest are jumbled together and slanted along the big piece of cardboard, as though the charges came so quick and numerous that he feared space and memory would run out.

I passed him by that first day and have done the same all the days after. When the light is red and the radio station is fixed, I’ll look over. Check on him. He’ll see me and raise his sign a little higher, and then the light will turn green and I’ll move along. That seems to be what everyone else does, as well. They just pass him by. We’re all busy, you see. We’re all just trying to get through our days. One old man with a sign that may or may not offer a window into his fragile state isn’t enough to give us pause, at least not enough pause to stop and ask what exactly he’s trying to accomplish. Even the folks at the gas company don’t seem to care. They haven’t even given the man enough thought to ask him to leave.

He was back yesterday, but not at the edge of the road. A few weeks of protesting without raising either sympathy or scorn has convinced him to change his tactics. He was now standing on the sidewalk, directly at the front door.

From what I could tell, it hadn’t made a difference.

To be honest, it’s funny in a way. Also sad. I don’t know what has driven him there and I don’t know if I would agree with his reasons, but a part of me is proud of him. Right or wrong, he’s stood up. He’s making his voice known. Of all the freedoms we enjoy, I can’t think of many more important—more necessary—than that.

Maybe that’s why I feel so much pity for him as pride. Because no matter what it is, it takes courage to stand up and speak. I know this. And all that courage can melt in a moment when you utter those first words and find only silence and apathy in return.

He was there again today, fighting the power. Standing up to The Man. Still with that determined look on his face. The light turned yellow and then red. I fixed the radio station and looked. He met my eyes and raised his sign a little, wiggling it. I gave him a thumbs up. He returned the same. Just two guys giving one another the same encouragement:

Carry on.

September 15, 2015

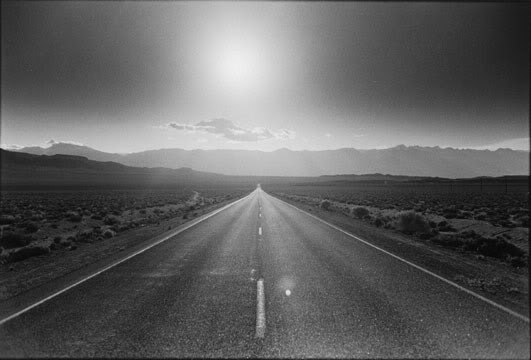

The Dry Season

image courtesy of photo bucket.com

I write these words some dozen feet from the soft earth of the Virginia mountains, my feet dangling from the thick willow branch that also supports my butt and my back, because rain has been scant here of late. Everything that was bright and green at the turn of August has now gone a rusty brown. Leaves are falling brittle and dead. The deer and the bear are coming out of the woods to forage what they can. Those you meet in town shake their heads and shrug (“What you gonna do?”) and cock their heads up to a cloudless sky the color of the sea.

The dry season is here. And that’s why I’m here, in my willow tree.

It happens every year around this time, usually between the start of school and the beginning of harvest. There will be a few showers here and there, thunderstorms that blow over the mountain and dump inches of rain in minutes, the water unable to pierce the hard ground and so floods the streets and lowlands. Water, but the sort that nourishes little and helps nothing. The kind of water that only makes the weeds grow.

Though it’s a little more difficult to rummage around in the woods this time of year, I still do. You have to mind the snakes and grouchy critters, and you have to understand that going along quiet will be impossible with all the dry wood and hard leaves. But it’s still the woods, still the quiet wilderness and the open sky and the mountains all around you, and that’s where I went a little while ago and where I’ve always gone with things get a little rough.

Dry seasons don’t just happen in the world. They happen in us, too.

Have you ever noticed that? There are seasons right outside your door and there are seasons right inside you, and both can blow cold gales or steady rain or bright sun, and both can make you happy for life and make you dread it.

Whenever it’s dry both inside and out of my own days, I’ll take a walk along a path through the woods across the street and listen for the sound of the bold stream that winds and dips its way from the deep mountain to the South River, and I’ll come here. In all my years, I’ve never known this stream to dry. No matter how parched the summers get or how long the snow doesn’t fall, the water here always runs. I’ll weave my way between all these dying and thirsty trees and follow the near bank, ease myself over the moss and slippery rocks, to the spot where the stream bends toward town. To where my willow sits.

It is an ancient one, tall and thick of trunk, with a canopy that rises and falls with a gentle grace of perfect symmetry. My tree is a marvel; I’ve never seen another quite like it. I’ll stand in its shadow and feel the cool of the air beneath its branches, rub my fingers over the long, slender leaves. Let it all fill my sight. And then I’ll leave my hat in the soft earth and slither up the trunk, my hands groping more by memory than sight, for the upward path to the first sturdy branch. There, I’ll sit and look and listen.

It isn’t a magic tree, this willow. As a boy I thought such things possible, even plentiful, but no longer. Not usually, anyway. Besides, this tree isn’t set apart from the hundreds and thousands of others surrounding it. It’s just as subjected to the seasons as any other. My tree isn’t always so green and blossoming. It doesn’t always look wonderful. It’s still in the world and so has no choice but to suffer along with the rest of its forest kin, to feel the stifling heat and the frigid cold, to be tasked with the very goal that is tasked to every other living thing everywhere—to endure, and for as long as it can.

Yet I’ve come here often in my own dry seasons (and I imagine I will continue doing so in all of my dry seasons to come) because there truly is something different about this particular tree, and advantage it possesses that the other trees here do not. And I scamper up these branches and sit and watch and listen so I will greater appreciate that difference and better apply it to my own life. Because even though this tree is planted in the same earth at the same base of the same mountain as so many untold others, this tree has also been planted along a stream that never dries. Its roots have access to a constant source of water. Even in the heat. Even in the dry season.

I sometimes fall into the trap of believing the happiness to be had in this world comes like the rain. It falls from the sky into my waiting arms and I try to gather up all I can, knowing that it will never rain for long. But here, in my willow, I know different. I know better. Real happiness is the kind that doesn’t depend on anything external, whether its rain from the sky or a cool breeze to chase the heat. It is instead found inside. Down deep, where your roots are.

It’s a lesson I’m going to try and hang onto whenever I decide to climb back down and resume my living. One I’d very much like to take home from the woods. It’s a valuable lesson, and maybe the most valuable one of all, to know that your happiness or your sorrow won’t come from whatever happens to you, but from where you’re planted.

September 9, 2015

Your six word memoir

Summer’s over. One look around our home will tell you this. There are school supplies stacked in each of my children’s rooms, and my teacher wife has been regaling me of the myriad educational ideas she’s found on Pinterest. As per usual, I’ve taken in all of this information with the appropriate amounts of nods and wows. It’s tough being a teacher. Tough being a teacher’s husband, too.

Summer’s over. One look around our home will tell you this. There are school supplies stacked in each of my children’s rooms, and my teacher wife has been regaling me of the myriad educational ideas she’s found on Pinterest. As per usual, I’ve taken in all of this information with the appropriate amounts of nods and wows. It’s tough being a teacher. Tough being a teacher’s husband, too.

One of these ideas, however, has struck me. So much so that it slowly became one of those things that simply refused to go away until I exorcised it through writing. Which is what I’m doing now.

It’s ironic, really, because this thing that’s gotten my wife fired up (as well as my brain moving) is a writing exercise—one that’s simple on top but difficult on the bottom. It’s a child’s game called The Six Word Memoir.

I’ve heard of such things before. Through the years there have been more than one writer who’s taken up the task to tell a complete story in the shortest amount of words. Six seems to be the magic number, and to me no one did it better than Hemmingway (his six word story—“For sale: baby’s shoes, never worn.”). It’s a tough thing, trying to whittle down a hundred thousand words or so into six and still call it a story.

But as I sat down the other night and reached for my notebook and pen, I discovered shrinking down forty years of life into six words was even tougher. After twenty minutes or so of desperately trying and utterly failing, I began to think that such an exercise was not only impossible, it was pointless, too. It seemed cheap in a way, taking all of my memories and hopes and balling them up into a few simple syllables. I’ve never held a very high opinion of myself, but that opinion had never been so low as to hold that six words were sufficient to define me.

Now that I’ve had some time to ponder, though, I’ve come to believe different. I sat on my porch for a full hour and went though three pages of paper (front and back, mind you) trying to get this right. Far from making me feel cheap, this whole experience has taught me much. There’s value in whittling down your life into six words. A lot.

It forces you to realize that all those things you think are necessary really aren’t at all. And also that the things you do that seem small are actually sort of big. You only have time for important things. There isn’t space enough for anything else. And really, how often in our comings and goings do we actually stop and ask ourselves what we’re coming and going for, or whether we’re chasing after the right things, or whether the meaning we give our lives is the same as God’s?

Deep stuff for six words, huh?

I sat there for a while longer. The last thing I wrote was “Stand. Fall. Stand. Fall. Stand. Repeat.” It has a ring to it, and it’s very true, but I don’t think those words say it all. I plan to try again. I plan to try a lot. It’s always good to know where you stand in this world.

How about you? Write your six word memoir below. Or if you’d rather, write it down and keep it to yourself. Spend some time with it and let me know. Whatever you do, don’t skip it simply because it’s a child’s game. Those are the ones who often hold the most truth.

September 2, 2015

The Shine

image courtesy of photobucket.com

I am sitting on the hood of my truck atop Afton mountain on a warm August night, taking the opportunity to do something I once did often but now not nearly enough.Stargazing.

I was six when my parents bought me my first telescope, a twenty-dollar special from K Mart. It was made of cheap plastic and the lens wasn’t very powerful, but to me it was magic. I spent countless nights in the backyard squinting through that telescope, peering into lunar seas and gazing at Saturn’s rings. I was spellbound.

As I grew older, the stars began to serve another purpose. They were my refuge, a physical manifestation of an inner longing to break free from both earth and life and fly away. The night sky was my perspective. Looking around always made everything seem so enormous and consequential. Looking up always reminded me of how truly small everything was.

Now? I suppose now those two sentiments mingle, swirled together in my heart as a patina that washes me in both awe and longing. I gaze up to gaze within and know my truest self – that both darkness and light can blend to form a scene of beauty and wonder. That despite whatever misgivings I may have, I can shine.

I lean back against the windshield, place my hat on a raised knee, and stare. Above me is what a friend refers to as “a Charlie Brown sky.” Pinpricks of light are cast in a sort of perfect randomness, as if God has sneezed a miracle.

I am not alone here. There are about twenty other people scattered along this overlook, fellow viewers of nature’s television. An awed silence envelopes most. All but one little girl sitting with her father in the bed of the truck next to me.

“Daddy?” she says. “Do we shine?”

A thoughtful question deserving of a thoughtful response.

“I think so,” he answers.

“It’s good to shine,” she says.

“Most times. I guess it depends on where the shine comes from.”

My head turns from the stars to them.

“What do you mean?” she asks.

“Well, you see that star over there?” He points to a bright speck above us. “That star gives its own shine. It doesn’t depend on anything else but itself to give it light. It’s on its own.”

“That’s a bright one,” she whispers.

“Yep. But one day, all that light will be gone. That star will run out of shine. But you see that over there?” he asks, pointing this time to a big, round ball.

“That’s the moon,” says the daughter. “I know all about the moon.”

“That so? Tell me.”

“Well, Mrs. Walker says the moon is dark and cold and dead. And it isn’t made of cheese, like Tommy Franklin said.”

“You have a smart teacher,” her father answers.

“I don’t want to be cold and dark and dead like the moon. I’d rather be a star.”

“But the moon shines, too. And it’s a better shine.”

“How?”

“Because the shine isn’t the moon’s, it’s the sun’s. Light come from the sun, bounces off the moon, and lights the dark.”

“So moonlight is really sunlight?” she asks with a tone of both wonder and doubt. Mrs. Walker hasn’t gone over this yet.

“Yes. And because the moon is just reflecting the sun’s shine, it won’t get tired and start to fade.”

“So as long as the sun shines, the moon will, too?”

“You got it.”

The two sit in silence again, and my eyes move from them back to the sky.

A lot of us choose to stand in our own light. We want to be known for the things we do more than the people we are. “Look at me,” we say. “I’m special. Better.”

But we’re not. The more we try to shine our own light, the darker we’ll likely become. And sooner or later, we’ll fade. We don’t need to be stars in this life and be a light unto ourselves. It’s better to be a moon. Better to know that we can reflect the shine of someone greater and be a light to the world.

August 27, 2015

Rich or Poor

“Daddy, are we rich?”

“Daddy, are we rich?”

My daughter at the dinner table. Which, since school has started again, is quickly becoming more of a place to discuss Important Things rather than eat.

If elementary school paints a broad stroke of a child’s future life, middle school narrows things a bit. I’m not just talking about things like math and history and spelling. I’m talking about where children fit into the scope of society. My daughter is in a classroom of about sixteen. That means there are fifteen other children who might be her age, but sometimes have little more in common.

There are children who are of a different color. Some have no father at home, or no mother. Some are from other parts of the state. A few are from other states completely.

Some have accents. Some wear glasses. There are the tall and the short, the big and the small, the smart and the not so much.

There is a mixing of ideas and life experiences, even if those ideas are still relatively undeveloped and those experiences are few. And the result is that all of the children, are trying to figure out where they fit in and why or why not.

The girl who sits next to my daughter whipped out a brand new toy from her book bag the other day. A nice toy. One that my daughter herself had expressed a desire to have every time the commercial appeared on the television. I told her it was too expensive, that it was the sort of thing that fell under Santa’s jurisdiction rather than her parents. Did that mean her parents had less money than than this other girl’s?

The boy who sits behind my daughter was quite the opposite. He has no toys. None that he has chosen to sneak into school, anyway. His clothes are worn and sometimes dirty, and his shoes look like they are too small. Like my daughter, his parents didn’t seem rich either. But unlike my daughter, he seemed to have even less.

So: “Daddy, are we rich?”

The thought occurred to me to put a spin on her question. I could use the whole We’re Rich In The Things That Matter speech. I could say that we had things like love and togetherness, things that make us rich but can’t really be seen most times.

Of course I could use the We’re A Lot Better Off Than Most speech, too. I could say that there are a lot of people in a lot of other places that didn’t have a house to stay in or good food to eat or even a television to watch. People who would consider us to be very rich indeed.

Neither of those options seemed right at the time. So I decided that honesty would be the best policy.

“No, we’re not rich.”

“We’re not?” she asked.

“No.”

“Then are we poor?”

“No.”

The paused with a spoon full of mashed potatoes in her hand. “Then what are we?”

I shrugged. “We’re normal.”

“Oh,” she said. “Okay.”

Thus ended our conversation.

Being normal was okay for her. No big deal. She wasn’t rich, which may have been a disappointment. But she wasn’t poor either, which may have been a bigger one. She was in the middle. Neither/nor. And that was fine.

I hope she always has this opinion of things. I hope that she never gets so ambitious as to forget her blessings and never so complacent as to forget that she can always be and do more.

It’s a delicate place, this normalness. It takes skill to be average. We Coffeys have become masters at it. It’s a source of pride.

August 25, 2015

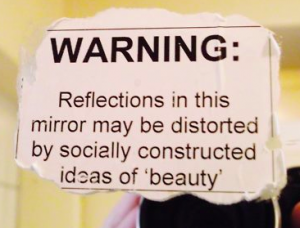

Beautiful

image courtesy of google images.

An hour ago:

“What are you doing?”

My daughter is standing on her bed and facing the mirror atop her dresser. She’s not looking at herself, not performing the sort of quick once-over females tend to do before going to town. Instead, she’s studying. Closely.

“I’m looking at myself,” she says.

“Why are you standing on the bed?”

“Because if I stand on the floor I can only see half. I want to see the whole thing.”

I offer the sort of nod I often give to females. The sort that says I don’t understand you, but I’m going to act like I do.

“Okay,” I tell her, “but hurry up. We’re ready to leave.”

She continues to scrutinize and then asks, “Daddy, can I ask you something?”

“Can you ask it in the truck?”

“Can you answer it here?”

“Okay, fine.”

She tilts her head to the side and lets her blond hair spill down over her shoulder. My daughter never used to pay attention to mirrors. Now she can’t pass by one without taking a peek to make sure nothing needs tucking or straightening or smoothing.

“Am I pretty?” she asks.

“Very much so,” I say.

She tilts her head to the other side. “Do you think Taylor Swift is pretty?”

“No.”

“Carrie Underwood?”

“No.”

“Well,” she says, “I think they’re beautiful.”

“Can we go to town now?” I ask her.

She hops off the bed and takes my hand. “What makes them beautiful, Daddy?” she asks.

“Well, since I don’t think they’re beautiful, I can’t really answer that question.”

“I don’t think I’m beautiful,” she says.

“Why’s that?”

“Because there’s a lot wrong with me.”

An hour later:

We’ve made it to town. My daughter managed to sneak away and into the truck before I could talk to her more. And heading to town with family in tow is not the proper time for such a conversation. So I’m currently left to stew and walk the aisles of the local Target, trying to decide how I’m going to finish the conversation her and I had begun.

At thirteen, my daughter is on the cusp of that age when appearance begins to matter more than it once did. I don’t think that’s really a bad thing, but it is confusing to her. She thinks everything is beautiful—sunrises, sunsets, and the puffy white seedlings atop dandelions come to mind—but she secretly fears she is not. I can understand. It’s hard to compete with sunrises, sunsets, and dandelions.

And when it comes to things that are beautiful in any obvious way, she still refuses to call them ugly. To her, ugly is just a word people use for things where the beautiful chooses to remain hidden.

That’s the way I want to keep it with her. Because that is nearest to the truth.

This is also the truth—there is a lot wrong with her. Behind that blond hair and those blue eyes is a little girl who has gone through much. Too much, if you ask me.

I see the way she wears long sleeves and pants in the warm weather to hide the bruises that can pop up after her insulin shots. I see the way she talks to friends with her hands in a fist so they won’t see the pock marks left on her fingers from her sugar checks.

It’s bad enough to have a disease, she’s told me. But when you believe that disease makes you ugly, it’s worse.

I don’t blame her for thinking that way. I think there are a lot of people—older, smarter people—who do the same. But what she sees as ugliness I see as a means of becoming beautiful. Her disease has given her a compassion and an understanding I could never have.

I remember recently reading about the Miss Navajo Nation beauty pageant. Held every year. The contestants do the sort of usual things you would find in any pageant anywhere. They dress up and show their talents and talk about what they would do if they held the title.

But there is no swimsuit competition. In its place is a demonstration of some traditional Navajo skill, which can be anything from weaving to butchering a sheep.

I like that.

Because beauty isn’t simply about looking pretty and speaking well. True beauty is useful. It draws attention not to how good you look, but what good you can do.

That’s what I’m going to tell my daughter when we get home.

I’ll let you know how it goes.

August 17, 2015

Empty years

image courtesy of photobucket.com

You reach a point when there’s enough behind you that it warrants a looking back. I’ve caught myself doing a little of that this past year. I’m forty-three now. That’s the sort of age that lends itself to a certain amount of introspection. I figure if all goes well, I’m somewhere close to the fifty-yard line of my life. It’s important to know from where I’ve come and to where I’m going.

The problem with looking over my shoulder is what’s staring back at me. If I’m honest, I’ll say I should be a little farther along than I am. I couldn’t imagine forty when I was eighteen. It was an age I painted in broad strokes and mixed colors. And yet even with that in mind, I’ve fallen short.

It’s all that empty space, you see. Giant chunks of years I spent doing large amounts of nothing. My past seems a waste for the most part, a long string of failures best defined by equal amounts confusion and ignorance.

I worked down at the town gas station for ten years after I graduated.

Spent five more at the factory.

I’m on year eight of an occupation that offers little in things like pay and advancement, but those shortcomings are more than made up for in stress and labor.

That’s twenty-three years all together. No wonder I walk around feeling like I’m playing catch-up.

I’m not alone in all this. I know plenty of other people who feel much the same way. We work hard and save what we can and still feel like a gerbil on one of those wheels that spin and spin and never go anywhere. Makes you wonder what it’s all about.

I was talking all of this over with a preacher friend of mine the other day. Smart guy, as most of them are. He’s older, which meant he knew exactly where I was coming from. And when I was done talking, this is what he said:

Jesus didn’t do much of anything for about twenty years. It doesn’t really feel right, saying that. I don’t mean to imply the Lord was lazy in any way. Bu the preacher supposed that if Christ had done anything worth mentioning between the time he left his momma and daddy to head home from Jerusalem without him and the time he called his disciples, someone would’ve said something. But the Good Book is silent on such things. No one knows what exactly Jesus was doing all those years.

That’s why you’ll find all those legends and lost gospels saying how he went to Egypt or India, or how he liked to make living sparrows out of mud. And while I can understand the allure of such things, the preacher thought it better that the Lord simply lived a quiet life back then. He rose up every morning and went to work. Helped his daddy build a door or a chair, maybe, or did his part with the household chores. He went home at the end of the day and broke bread and talked and laughed, and then he went to bed knowing the next day only promised more of the same.

But the preacher also told me all those empty years weren’t for nothing. Sure, the three or four years after were more exciting. Those were the ones filled with miracles and intrigue and a rising from the grave. But none of those things could have happened were it not for those quiet years before. That was the preparation. The getting ready.

I like that.

That’s why I’m going to try and reconsider my own missing years. I’m going to try and look upon them in a new way. Because really, is there anything quiet when it comes to God? Any moment without purpose? Anything in even the smallest life that could be considered as lost or missing?

I think not.

August 13, 2015

No less precious

image courtesy of photobucket.com

It was a little over sixteen years ago when Ken Copeland’s wife woke up feeling a little queasy. It was a Sunday, he remembers. The big deal that day was the football game later that afternoon. Redskins and Cowboys.

Ken never saw that game, because his wife decided to take a pregnancy test later that morning. In the two years they’d been trying to conceive a child, she’d gone through dozens of those tests. All had produced nothing but a disappointing minus sign. On that day, however, a vertical line appeared and bisected that familiar horizontal one. It was a plus.

Ken and his wife celebrated that day with tears, fears, and a steak dinner at the Sizzlin’ in town. They told everyone (even the waitress, who discounted their steaks as congratulations). Everyone wanted to know if Ken wanted a boy or a girl. His answer was the usual one. Ken didn’t care, just so long as the baby was healthy.

Matthew Brent Copeland was born nine months later at the local hospital.

Fast forward sixteen years to the playground at the local elementary school. Father and son are at the swings, Ken pushing Matthew. It’s the younger Copeland’s favorite activity, one that somehow calms the storms that rage in his mind. Ken thinks it’s the back and forth motion that does it, that feeling of flight and peace. He takes Matthew there every evening.

There are smiles on both their faces, though that hasn’t always been the case. The Copelands went through a tough time when Matthew was diagnosed with autism at age four.

In quiet conversation, Ken will tell you that almost killed him. He’ll admit the anger he felt toward God and the despair over his son, whose life would now never be as full and as meaningful as it should have been.

And he’ll tell you that deep down in his dark places, if he and his wife would have known what would happen to Matthew, he would have preferred abortion over birth. There would be less pain that way. For everyone.

Yet now, twelve years later, he smiles.

I watch them from the privacy of a bench on the other side of the playground. See him push his grown son and yell “Woo!” as he does. I see the perfect and innocent smile on Matthew’s face as he’s launched out and up. Hear his own “Woo!” in reply.

When they’re done, Ken takes his son’s hand in his own and together they walk across the soccer field toward home. Their steps are light, they take their time. It’s as if their world has stopped for this moment between father and son to marvel at the bond between them, proof that the hardships life sometimes thrusts upon us don’t have to break our hearts. They can swell our hearts as well and leave more room for loving.

Ken has made his peace. Peace with God, with his life, with his son’s condition. It hasn’t always been easy, but nothing that is ever worth something is easy. There are still times when he looks at Matthew and wonders what his son’s life would be like if he were normal and healthy. He’s sixteen now, that age where a boy’s world should expand in a violent and glorious eruption of girls and cars and sports. But Matthew’s world will never expand. It will always remain as small as it was when he was four, and just as simple.

Ken says that’s okay. That it has to be. He’s learned that in a world that seems full of choices, there are really only two—we can hang on, or we can let go. Ken has let go. Of his anger and his disappointment, of his despair. And he’s found that what has replaced those things are peace and fulfillment and joy, things he’d always chased after but until Matthew came along never really found.

If Ken would change anything, it would be what he said to all those people who’d asked him if he wanted a boy or a girl. His one regret is what his answer always was, that it didn’t matter as long as the baby was healthy. Because an unhealthy baby is no less precious, no less valuable, and no less life-changing.

August 10, 2015

When Mockingbirds Sing free promotion

I know that The Curse of Crow Hollow is still hot off the presses, but I wanted to share an opportunity to download When Mockingbirds Sing for free for a limited time. If you haven’t had a chance to read it, this would be a great opportunity to do so from

or

If you’ve already read When Mockingbirds Sing, would you consider helping us spread the word about the free download?