Nate Silver's Blog, page 91

February 5, 2018

Politics Podcast: Has Trump Remade The GOP?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

This week, the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast discusses whether the Nunes memo was much ado about nothing — and even if is is, whether it could still cause political consequences. The crew also discusses whether Trump has molded the GOP in his image and what it takes to shift a party’s ideology — and the ideology of its voters.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Could A Stock Market Downturn Tank Trump’s Approval Rating?

The stock market fell on Monday. A lot. After a roller-coaster day, the Dow Jones industrial average ended down 1,175 points, making for the largest single-day point decline in its history.

In percentage terms, the decline isn’t nearly as bad — the 4.6 percent drop is well short of the record 22.6 percent sell-off that occured on Oct. 19, 1987, otherwise known as “Black Monday.” The Dow would have had to lose almost 5,700 points on Monday to equal Black Monday on a percentage basis.

But it’s likely that there will be further volatility in the days ahead. The Dow had a very good first few weeks of January, gaining almost 2,000 points and peaking at an all-time closing high of 26,616.71 on Jan. 26. The index has given up all of its 2018 gains and then some since then, however. Meanwhile, the Chicago Board Options Exchange’s VIX, a measure of implied volatility in stock prices over the next 30 days, spiked dramatically on Monday to finish its session at 37.3 points, a level rarely seen since the end of the financial crisis.

This is usually the point at which I’d pause to deliver various pedantic admonitions about the stock market. For instance, I’d tell you that the Dow isn’t a very good stock market index as compared to broader and more robustly constructed ones such as the S&P 500, which declined by slightly less on Monday. I’d also tell you that the stock market isn’t always a very good proxy for the nation’s overall economic health. In fact, the latest decline in share prices has been triggered, in part, by fears that the Federal Reserve would raise interest rates because of strong wage and job growth. Good pocketbook news for workers can sometimes be bad news for investors, and vice versa.

I’m someone who writes about politics, however — and in political terms, the decline in the Dow is potentially important. President Trump has spent lots of time bragging about the stock market over the past year, from dozens and dozens of references in his Twitter feed to a riff about it in last week’s State of the Union address. Moreover, the stock market is a highly visible economic indicator. Sure, something like real disposable income per capita might be a better overall measure of economic well-being. But the Dow gets mentioned a lot more often on the evening news.

Overall, the stock market still looks pretty good for Trump, with the Dow having gained 23 percent during his presidency so far. But could a further reversal in those gains harm his approval ratings, which have been improving lately? Trump’s approval rating is now 40.4 percent in FiveThirtyEight’s index — not good, but the highest it has been since May 15.

The short answer is, sure, there could be some risk to Trump. One should not necessarily expect there to be an obvious one-to-one correlation, however. After Black Monday in 1987, then-President Ronald Reagan’s Gallup approval rating actually improved to 51 percent from 49 percent two months earlier. The point is not that Black Monday helped Reagan — it probably didn’t — but that whatever effect it had was swamped by other news events, plus whatever random statistical noise there was in the polling average. My past research also suggests that stock market growth has historically been a fairly weak predictor of a president’s odds of being re-elected.

More recent academic research has found that there probably is some relationship between presidential approval ratings and the stock market, however. Furthermore, there’s fairly robust evidence linking overall economic performance to presidential approval.

I’m marginally skeptical of these studies, but only because it’s difficult to separate out the influence of the stock market (or any other economic indicator) from the rest of the economy. The present sell-off aside, there usually is some correlation between the stock market and other measures of economic well-being. The massive stock-market decline in 2008 was indicative of much broader problems with the economy, for example. Studies that take a bunch of highly correlated variables (e.g., the stock market, unemployment, inflation, consumer confidence, etc.) and attempt to correlate them with another variable (e.g., presidential approval) can run into all sorts of methodological problems such as overfitting.

In other words, there are lots of reasons to think there’s a reasonably strong1 relationship between economic performance and presidential popularity. It’s very difficult to say which particular indicators the public cares most about, however. (The approach we take for FiveThirtyEight’s election forecasts, which are partly based on economic data,2 is essentially to average a bunch of economic indicators together — including the S&P 500 — but weigh them equally.)

Moreover, the relative importance of different economic indicators can change from presidency to presidency, based on which ones that politicians and the media are talking about and which have had more visible effects lately. Inflation was a much more salient political topic during the 1970s and 1980s than it is now, for example.

But therein lies the risk to Trump. He has frequently highlighted the stock market — something that President Obama rarely did, by contrast, even though the Dow rose by almost 140 percent during Obama’s two terms in office. If it continues to decline, it will be tough for Trump to dismiss its significance. Nor will he be able to cast doubt on the reliability of the numbers, since the price of a stock is not a government-created statistic and is simply a market price.3

Most presidents avoid talking about the stock market because of its unpredictability and volatility. In an era of algorithmic trading, there’s some relatively minor piece of economic news, and voila! — the Dow can swing by 2,000 points in a few weeks or several hundred points in a day. By contrast, although macroeconomic conditions are not highly predictable at intervals more than about six months in advance — it’s too soon to know quite what the economy will look like at the midterms — we’re at least talking about changes that play out at intervals that span months to years and not days to weeks. U.S. GDP, currently $17.3 trillion, is extraordinarily unlikely to jump to $20.8 trillion or $13.8 trillion next month (a 20 percent increase or decline, respectively). But if the Dow were 20 percent higher or lower a month from today, it wouldn’t be any enormous surprise. Trump should probably stick to bragging about jobs and wage growth, because those numbers have also been pretty good and the gains are more likely to hold.

February 1, 2018

What Happened To The Democratic Wave?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): For your consideration today:

Whatever happened to that Democratic wave?

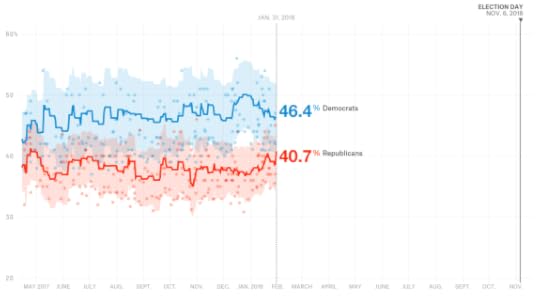

The Democratic advantage over Republicans on the generic congressional ballot is down to less than 6 percentage points:

What’s going on? Is it time for Democrats to

January 29, 2018

Politics Podcast: Which Version Of Trump’s Presidency Is Happening?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

On the eve of President Trump’s first official State of the Union address, the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast checks in on how his administration is doing, and which of the 14 versions of Trump’s presidency that Nate outlined about a year ago look like they could still happen. The team also previews Trump’s speech — do State of the Union addresses matter?

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

January 25, 2018

The Atlas Of Redistricting

FiveThirtyEightSERIESThe Gerrymandering Project

PUBLISHED JAN. 24, 2018 AT 4:59 PM

The Atlas Of Redistricting

By Aaron Bycoffe, Ella Koeze and David Wasserman

There’s a lot of complaining about gerrymandering, but what should districts look like? We went back to the drawing board and drew six different congressional maps for the entire country. Each map has a different goal: One is designed to encourage competitive elections, for example, and another to maximize the number of majority-minority districts. See how changes to district boundaries could radically alter the partisan and racial makeup of the U.S. House — without a single voter moving or switching parties. How we did this >>.[a]

GO TO: Nation Alabama Arizona Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut Florida Georgia Hawaii Idaho Illinois Indiana Iowa Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Nebraska Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania Rhode Island South Carolina Tennessee Texas Utah Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin PARTISAN GOALS OTHER GOALS

Show current district boundaries

Gerrymander districts to favor Republicans

Gerrymander districts to favor Democrats

Match partisan breakdown of seats to electorate

Promote highly competitive elections

Maximize number of majority-minority districts

Make district shapes compact (using an algorithm)

Make districts compact while following county borders

← National map

Alabama’s current congressional district boundaries

How often we’d expect a party to win each of Alabama’s 7 seats over the long term — not specifically the 2018 midterms — based on historical patterns since 2006

100% D100% RBirminghamBirminghamMobileMobileHuntsvilleHuntsvilleMontgomeryMontgomery

USUALLY DEMOCRATIC DISTRICTS

HIGHLY COMPETITIVE DISTRICTS

USUALLY REPUBLICAN DISTRICTS

Current

1

0

6

Current

1

0

6

About the current map

These are the current congressional district boundaries, shaded by how likely each is to be represented by a party over the long term. This is not a forecast of the 2018 midterm elections.

The politics of Alabama’s maps

Party probabilities

Every district by the chance it will be represented by either party

DEM. CHANCES

GOP CHANCES

100%70%60%50%60%70%100%

Proportionally partisan

Majority minority

Democratic gerrymander

Highly competitive

Compact (borders)

Current

Republican gerrymander

Compact (algorithmic)

Expected seats by party[d]

The expected number of seats controlled by Democrats and Republicans, based on their long-term likelihood of winning each district

DEMOCRATSEVEN SPLITREPUBLICANS

1.95.1

1.95.1

1.95.1

1.65.4

1.15.9

1.06.0

1.06.0

0.76.3

Ranking Alabama’s maps

How the maps compare on district competitiveness, minority makeup, compactness, respect for local borders and the efficiency gap, an attempt to gauge how politically gerrymandered a set of districts is

Efficiency gapA measure of “wasted” votes, by the size of the advantage and which party it favors

Dem. gerrymander

D+4%

Majority minority

D+4%

Proportional

D+4%

Compact (borders)

D+6%

Competitive

D+6%

GOP gerrymander

R+10%

Current

R+10%

Compact (algorithmic)

R+17%

Competitive districtsNumber of districts in which both parties have at least a roughly 1-in-6 chance of winning

Compact (algorithmic)

2

Competitive

2

Compact (borders)

2

Current

0

Proportional

0

Majority minority

0

GOP gerrymander

0

Dem. gerrymander

0

Majority-nonwhite districtsNumber of districts in which a majority of the voting-age population is nonwhite

Proportional

2

Majority minority

2

Dem. gerrymander

2

Current

1

GOP gerrymander

1

Competitive

1

Compact (algorithmic)

0

Compact (borders)

0

County splitsNumber of times a map splits counties into different districts

Compact (borders)

5

Dem. gerrymander

8

GOP gerrymander

8

Majority minority

8

Proportional

8

Current

8

Competitive

12

Compact (algorithmic)

34

Compactness rankRank by the [e][f][g], from least (best) to greatest (worst)overall geographic compactness of its districts

Compact (borders)

1

Compact (algorithmic)

2

Dem. gerrymander

3

Majority minority

3

Proportional

3

Competitive

6

GOP gerrymander

7

Current

7

Breaking down Alabama’s current map by race

The racial makeup of each district, and each district’s likelihood of being represented by a member of a racial minority, based on election results since 2006.

WHITEAFRICAN AMERICANHISPANIC/LATINOASIAN/PACIFIC ISLANDEROTHER

SHARE OF POPULATION BY RACE

CHANCE OF BEING REPRESENTED BY A …

DISTRICT

MAJORITY RACE

0% 50% 100%

MINORITY MEMBER

DEMOCRAT

REPUBLICAN

1st

White

9%

>99%

2nd

White

10%

>99%

3rd

White

6%

>99%

4th

White

>99%

5th

White

3%

>99%

6th

White

1%

>99%

7th

African-American

95%

>99%

All demographic data from the 2010 census. Six of the seven alternative congressional district maps were drawn using Dave’s Redistricting App, a free online tool for experimenting with political boundaries. Its creator, Dave Bradlee, modified the app to make this project possible. The seventh map comes from software engineer Brian Olson, who wrote an algorithm to draw districts with a minimum average distance between each constituent and his or her district’s geographic center. Read more about how we drew these maps and how we are evaluating them in our methodology.[h]

Get the data on our GitHub page[i]

Additional contributions from Nate Silver and Julia Wolfe

Sources: Ryne Rohla/Decision Desk HQ, U.S. Census Bureau, Brian Olson

More from this series

METHODOLOGY

We Drew 2,568 Congressional Districts By Hand. Here’s How.

PODCAST & VIDEO

ESSAY

Hating Gerrymandering Is Easy. Why Is Fixing It So Hard?

COMMENTS

Get more FiveThirtyEight

Newsletter

Videos

Podcasts

GitHub

RSS

Contact

Jobs

Masthead

Privacy and Terms of Service

About Nielsen Measurement

We Drew 2,568 Congressional Districts By Hand. Here’s How.

In most states, district maps — which define where the constituency of one representative ends and that of another begins — are drawn by the state’s lawmakers. Having politicians define their own districts has not gone entirely smoothly — and two cases involving political gerrymandering, or the drawing of districts (especially oddly shaped districts) to favor one party over another, are now before the U.S. Supreme Court.

But if gerrymandering is a bad way to draw districts, what happens when you try other ways? At FiveThirtyEight, we’ve been exploring this and other questions in “The Gerrymandering Project.”

As part of this project, we set out to determine what districts for the U.S. House of Representatives could look like if they were drawn with different goals in mind. We did the drawing ourselves … 258 state congressional maps, or 2,568 districts, sketched out over the course of months, with the indispensable help of one developer’s free online redistricting tool.

We looked at seven different ways of drawing congressional districts for the entire country — from pretty fair to seriously gerrymandered. See how the makeup of the U.S. House changes with each map »

No single map can fulfill all the criteria we looked at — more competitive elections or more “normal-looking” districts, for example. Depending on the desired outcome, each of the different maps could represent the “right” way to draw congressional district boundaries. If you haven’t explored the maps in our Atlas Of Redistricting yet, we hope you’ll do that now. Below are the details of how we made and analyzed all of them.

Eight ways to draw a district

Our atlas includes eight different congressional maps of the entire country. Each of those eight maps is made up of a distinct set of 43 state maps (seven states can’t be redistricted because they have only one congressional district that spans the entire state). The first set of maps is:

The current congressional boundaries

We made each of the other seven with a different goal in mind:

2. Gerrymander districts to favor Republicans

3. Gerrymander districts to favor Democrats

4. Match the partisan breakdown of seats to the electorate

5. Promote highly competitive elections

6. Maximize the number of majority-minority districts

7. Make district shapes compact (using an algorithm)

8. Make districts compact while following county borders

We drew six of these sets by hand — Nos. 2-6 and No. 8 — using a tool called Dave’s Redistricting App (more on that later). The districts for No. 7 were designed by a software engineer named Brian Olson.

All of the hand-drawn maps follow two simple rules: Each district must be contiguous, meaning that all parts of the district touch each other, by water or by land. And each district must be within 1,000 residents of the state’s “ideal” district population — the total population in 2010 divided by the number of districts — to satisfy the legal requirement that districts be equally populous.

Before we get into the specifics of each type of map, here are some more overarching guidelines we followed, for both the map-making and the analysis. When considering partisanship — some maps were drawn with specific partisan aims, and we calculated the partisanship of every district in every map — we used the Cook Political Report’s Partisan Voter Index. PVI measures how much more Democratic or Republican a district voted relative to the national result in an average of the last two presidential elections. We categorized partisanship into three “buckets”:

Usually Democratic districts (those with an estimated PVI score of D+5 or higher — in other words, at least 5 percentage points more Democratic than the nation)

Competitive districts (those with an estimated PVI score between D+5 and R+5)

Usually Republican districts (those with an estimated PVI score of R+5 or higher)

But we didn’t stop there. We also used congressional results from 2006 to 2016 to figure out how often a Democrat or Republican wins a district with a given PVI. In effect, we translated PVI into either party’s chance of winning the seat in question (more on this below).

When considering race, we used voting age population data from the 2010 census. Many courts have considered citizen voting age population as a legal standard to evaluate districts. However, the decennial census does not report citizenship status, and we considered voting age population the best, most readily available metric for our purposes. We categorized districts into five race buckets:

Non-Hispanic white majority

African-American majority

Hispanic/Latino majority

Asian/Pacific Islander majority

Coalition, or majority-nonwhite (no single majority group)

We drew all but two of our seven maps to comply with the Voting Rights Act by preserving the majority-minority status (though not necessarily the exact boundaries) of all 50 current districts where one minority group constitutes a majority of the voting age population. However, our two “compact” maps (the one that follows current county borders and the algorithmically drawn one) disregard the Voting Rights Act to demonstrate what districts might look like if they were drawn to maximize compactness on a race-blind, party-blind basis.

In some cases, a single map met more than one goal. For example, California’s Republican gerrymander map also fits our criteria for a proportionally partisan map, so they are the same. Some maps weren’t possible because of political or racial realities — i.e., a majority-minority map of New Hampshire or a Republican gerrymander of Hawaii. In those few cases, we drew a map that came as close as possible to meeting the approach’s objective.

Here’s a bit more detail on each map:

1. Current districts

These are the congressional districts currently in effect for the 2018 elections. The probabilities listed on this map do not reflect predictions for the 2018 election specifically, but instead are how often we’d expect each party to win the seat over the long term based on its Cook PVI across a variety of political conditions.

2. Republican gerrymander

This map seeks to maximize the number of usually Republican districts — those with a Cook PVI of R+5 or greater (which we’ve found corresponds to at least an 82 percent chance of a Republican victory). Where additional strongly Republican districts are not possible, this map seeks to maximize the number of competitive districts (Cook PVI between D+5 and R+5). Think of these maps as extreme Republican gerrymanders — a reference point for how far Congress could be pushed to the right.

3. Democratic gerrymander

This map seeks to maximize the number of strongly Democratic districts (Cook PVI of D+5 or greater). Where additional strongly Democratic districts are not possible, this map seeks to maximize the number of competitive districts (Cook PVI between D+5 and R+5). Think of these maps as extreme Democratic gerrymanders — a reference point for how far Congress could be pushed to the left.

4. Proportionally partisan

This map seeks to draw districts that favor each party in proportion to the overall political lean of each state. For example, if a state has 10 districts and Republicans won an average of 70 percent of its major-party votes in the last two presidential elections, we drew seven districts to favor Republicans and three to favor Democrats.

5. Highly competitive

This map seeks to maximize the number of highly competitive districts — those with a Cook PVI between D+5 and R+5. In terms of probabilities, that means both parties have at least an 18 percent chance of winning these seats.

6. Majority minority

This map seeks to maximize the number of districts where members of a single minority group make up a majority of the voting age population. Because of lower rates of citizenship among Latinos, the map strives to create 60 percent Hispanic/Latino districts where possible. Where additional majority-minority districts are not possible, the map seeks to maximize “coalition” districts where no racial group makes up a majority.

7. Compact (algorithm)

This map is based on Olson’s computer algorithm, which seeks to minimize the average distance between each constituent and his or her district’s geographic center. It is the only set of state maps (other than the current congressional boundaries) that we did not draw by hand. It is based on census blocks and is blind to race, party and higher-order jurisdictional boundaries like cities and counties. It makes no attempt to adhere to the Voting Rights Act.

8. Compact (borders)

This race-blind and party-blind map seeks to maximize compactness by using counties as building blocks when drawing districts. The map splits counties only as many times as necessary to create equally populous districts, and where possible, entire districts are kept whole within counties, metro areas and regions. When counties are split, the map seeks to minimize splits of county subdivisions, such as cities and townships. It makes no attempt to adhere to the Voting Rights Act.

How we drew all those districts

Between June 2017 and January 2018, we drew 258 congressional maps for this project using Dave’s Redistricting App, a free, web-based, do-it-yourself redistricting application created by software engineer Dave Bradlee. Bradlee, who launched the app in 2009, made this project possible by helping us update his app with election results from 2012 and 2016.

Before we started work on the atlas, Dave’s Redistricting App already had data on population and race, which we used to draw the maps that did not take partisanship into account (the majority-minority map and the compactness map that follows borders). To draw the other four maps, we needed up-to-date vote data in the app.1 So we acquired precinct-level voting results for the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections from Decision Desk HQ, along with the boundaries of the precincts in those elections.

Those results weren’t quite complete enough for our purposes. We needed to account for absentee votes, which many states report only at the county level, not by precinct. In those states, we took all the absentee votes for a given candidate in a county and assigned them to precincts based on the precinct’s total share of in-person voters for that candidate. For example, if a precinct accounted for 5 percent of the Democratic candidate’s votes in a county, that precinct would be assigned 5 percent of the candidate’s absentee votes for the county.

Then, to get the more recent election data into the app, we converted it to the geographical building blocks that the app uses: 2010 precincts (specifically, voting districts provided to the Census Bureau by states) and block groups.2

To do that, we first allocated the votes in each precinct to the precinct’s component census blocks. Each block was allocated a share of the precinct’s votes matching its share of the precinct’s voting-age population.3 Most blocks lie fully within a precinct, but in some cases, portions of a block fall in multiple precincts. In those cases, we split the block’s voting-age population based on the percentage of the block’s area that is in each precinct and allocated votes accordingly. Once we calculated the election results in each block, we combined the results using block-assignment files provided by the Census Bureau, which tell us which blocks are in which 2010 voting districts.

Then we provided the 2012 and 2016 results for each 2010 voting district to Bradlee, who added a way to see the Cook PVI of each custom-drawn district in his app.

Once the districts were drawn, we exported them from the app so that we could do our own analysis.

From political boundaries to election odds

The probabilities of electing a Democrat or Republican are based on how often seats with a given Cook PVI elected members of each party between 2006 and 2016. They reflect a seat’s expected performance over the long run, across a variety of political conditions. They are not predictions for the 2018 election, specifically.

We’ve also estimated the probability of a district electing a minority representative, based on the racial composition of each district and its Cook PVI. Districts with large numbers of nonwhite voters are much more likely to elect minorities, especially if they consist primarily of one ethnic or racial group (e.g., African-Americans) as opposed to a coalition of different racial groups. More Democratic-leaning districts are also slightly more likely to elect minorities, other factors being equal. This calculation is based on historical data between 2006 and 2016, although it includes an adjustment for the fact that minority representation has slightly increased over time.

Comparing the maps

One goal of this project was to see how the different types of maps compared on a few important factors — for example, would prioritizing compact districts mean losing majority-nonwhite districts, or would trying to stick to county borders and ignoring partisanship end up favoring one party over the other? We evaluated all the maps on a variety of metrics:

Expected seat split: We calculated the expected number of seats controlled by Democrats and Republicans, based on the parties’ likelihood of winning each district in the long term. A district that has a 60 percent chance of being represented by a Democrat and a 40 percent chance of being represented by a Republican, for example, counts as 0.6 of a Democratic representative and 0.4 of a Republican representative. To get the breakdown for a state, we totaled up the counts for each side.

Efficiency gap: This is one measure of how politically gerrymandered a legislative map is (and is currently the subject of a Supreme Court case). Using election results, the efficiency gap looks at the number of “wasted votes” for each party in each of the districts. Two types of votes are considered “wasted”: those cast for the losing candidate and those cast for the winning candidate in excess of what that candidate needed to win. The “gap,” expressed as a percentage, is the difference in each party’s wasted votes as a share of the total votes cast in the state. (See here for a more detailed, step-by-step guide to calculating the efficiency gap.) We don’t have real congressional election results for our hypothetical districts, so our efficiency-gap calculations use an average of the major-party vote in the past two presidential elections. In our atlas, we present the efficiency gap as a percentage in favor of either party (e.g., a value of R+7 percent means that there’s an efficiency gap of 7 percent that favors Republicans).

Competitive districts: We counted how many districts have a Cook PVI between D+5 and R+5.

Majority-nonwhite districts: We tallied the number of districts where nonwhite people make up a majority.

County splits: This counts how many times a district map splits counties into different districts. A common goal of redistricting is to preserve “communities of interest,” or groups of people who have common concerns (such as those who live in the same locality) and therefore have an interest in electing representatives together. We’ve used counties as a proxy for such communities. If a county contains all or part of two districts, it would be considered to have been split once (because the districts would share a common border).

Compactness rank: This is a way of evaluating the relative geographical compactness of districts in different maps. There are several methods for measuring the compactness of a geographic area, each of which has pros and cons. For our compactness rank, we focused on the perimeters of district boundaries because that allowed us to compare maps. We took the difference between the perimeter of the state and the sum of the perimeters of the districts’ boundaries and then divided by two (because each interior line is shared by two districts). In some cases, this approach can penalize relatively compact districts with jagged boundaries. But overall, it does a reasonable job of detecting which maps are more convoluted than necessary.

January 24, 2018

Is The Democratic Party Becoming More Like The GOP?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): Welcome, all!

For debate today, an idea that’s been knocking around a lot since the government shutdown: That the Democratic Party is becoming more like the Republican Party.

harry: I think it is.

Chat over?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Fin.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): Yeah, I hinted at this in my shutdown piece, as did Matt Grossman in Politico and Michael Tomasky in The New York Times. Our own Washington editor, Hilary Krieger, feels this way too.

micah: So, someone explain the basic idea of what people mean by this.

perry: Essentially, the concept is that the factor that led to the shutdown (lots of pressure from the Democratic base on Senate Democrats) and the decision itself to force shutdown were reminiscent of the GOP, the tea party and the 2013 shutdown.

natesilver: It feels like there are actually two interrelated concepts here:

Is the Democratic base becoming more “extreme” and less willing to compromise?

Are Democrats becoming more willing to use parliamentary tactics and otherwise push the boundaries of the rules to achieve those goals?

micah: Right, so let’s take those one at a time …

No. 1: Are Democrats more liberal? And, somewhat relatedly, are they less willing to compromise?

And do those answers depend on which Democrats you’re referring to? Elected officials, voters, etc.

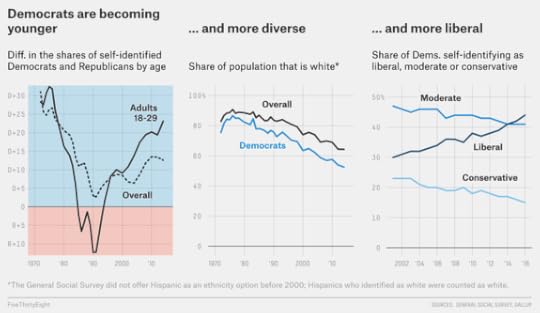

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): Well, more and more Democrats are identifying as liberal than ever before, I believe.

natesilver: There’s lots of evidence that Democrats are becoming more liberal, yes. Both voters and legislators.

micah: From Clare’s big look at the Democratic Party one year ago:

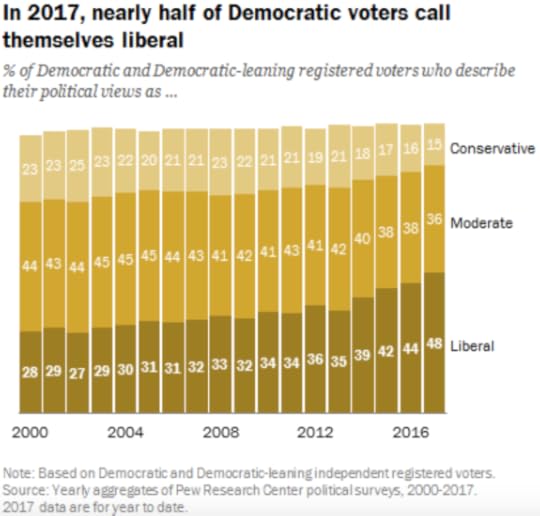

clare.malone: And here’s Pew showing the same thing:

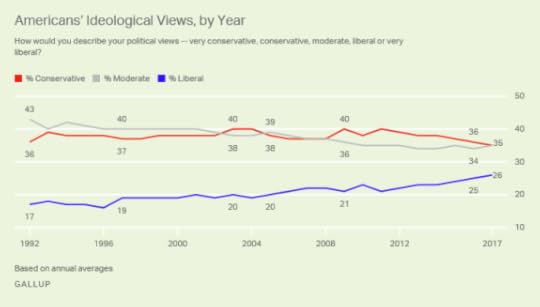

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Gallup too:

micah: Someone give me a legislator chart!

harry: The answer to legislators is a bit more complex. There’s the argument for asymmetric polarization, that Republicans have become much more conservative but Democrats haven’t really become more liberal.

I don’t know if I buy that, however.

natesilver: I might have bought that four years ago, but it’s more dubious now.

micah: But isn’t the asymmetric argument that GOP legislators have grown more conservative than Democratic legislators have grown liberal? But that Democrats have still grown more liberal?

perry: I saw this as, in part, a story of the activist groups on the Democratic side becoming more aggressive, perhaps because the party’s voters overall are more liberal and the members in Congress have to be responsive to that. Here’s what I wrote after the shutdown was resolved:

I can’t say this for sure, but it’s hard to imagine even this brief shutdown happening without liberal groups like Indivisible and the hosts of the popular left-leaning Pod Save America imploring the party to take a strong stand on [the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy]. Pod Save America was carefully tracking whether Senate Democrats publicly committed to blocking the funding bill without DACA, and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren tweeted Pod Save America’s hashtag #FightClub when she noted that she would oppose the legislation.

clare.malone: Wouldn’t 2018 be the year to accelerate the trend of liberalizing legislators?

Especially since all the kool kids maybe running for president are getting more liberal?

natesilver: Look at how some of the potential 2020 candidates are voting.

micah: I 100 percent think the idea that President Trump would radicalize the Democratic Party makes a certain amount of sense.

clare.malone: I agree with that.

And then you had Sen. Bernie Sanders’ influence, which we really can’t discount — especially in the aftermath of Hillary Clinton’s loss. People seem more likely to advocate for his kind of progressive politics as an answer to Trump’s (initial) populist take on policy.

natesilver: I was talking to someone the other day who called Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand a moderate, based on her previous track record. But look at her voting record this year, and she has the lowest Trump score of anyone in the Senate. You can be really far left in a Bernie way, or really anti-Trump in a partisan way, or both, but it’s getting harder to get away with being moderate if you’re a prominent Democrat.

harry: The idea that Gillibrand is a moderate is the biggest load of malarkey I’ve ever heard. But I’ll let Silver go on here for a little.

natesilver: The guy I was talking to, who is conservative, was positing her as the more reasonable alternative to Sanders and Sen. Elizabeth Warren. But she’s still pretty darn liberal! The point is that everything has shifted to the left.

micah: She used to be more moderate, no?

harry: I think that’s not particularly true, Micah. She was for around five seconds as a member of the House. But yeah, Gillibrand is really quite liberal.

clare.malone: OK, but what was the larger point in all this? That more and more people are acting as Gillibrand did, right? Sensing a movement in the party to the left.

micah: Yes.

natesilver: One thing we haven’t seen as much is Democrats going after their moderates in red states. Sen. Joe Manchin has come under occasional scrutiny, but it hasn’t quite metastasized into anything.

clare.malone: Perhaps — especially during the first half of Trump’s tenure, with the GOP owning the government, basically — it’s more practical and rhetorically effective to be an insurgent politician rather than a compromiser if you’re looking to make headlines.

National headlines, I mean. I think Manchin, for instance, wants to make headlines for being a good chum of the Trump White House when he can.

micah: OK, so let’s tackle the second part of that question now: There’s a bunch of evidence that the Democratic Party has become more liberal, but is there evidence that it’s become less open to compromise?

perry: Two important distinctions. First, Democrats seem to be moving left in terms of policy. (The wide embrace of Medicare for all by the 2020 candidates, for example.) But DACA specifically — the issue at the center of the shutdown fight — is not a particularly liberal policy. John Kerry supported an earlier version of it in 2004. Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham supports DACA right now.

Second, as Nate said, I don’t think the Democrats who voted against the shutdown will be primaried, like what tends to happen on GOP side.

Democrats have become more like Republicans, but not in every way.

natesilver: I’d go back to those Trump scores again. Democrats aren’t providing much support to Republicans on anything, and especially not on key pieces of legislation. No Democratic votes for any version of the GOP health care and tax bills, for instance.

Republicans haven’t really tried to solicit their help, either.

But partisanship is less asymmetric and more bidirectional now. If stats like DW-Nominate aren’t showing that yet, I suspect they will within a few years

micah: Yeah, I’m not sure the Trump scores show that Democrats are unwilling to compromise; Republicans haven’t really offered them many legitimate compromises.

harry: I’m going to agree with Mr. Silver on the next couple of years. I don’t think it’s surprising that Sen. Kamala Harris is ranked second in the Senate for most liberal in DW-Nominate score and Rep. Pramila Jayapal is the most liberal in the House.

natesilver: Look at what Democrats are doing in California, where they run the show. It’s pretty freaking liberal! Not a huge exaggeration to say it increasingly resembles a Scandinavian state.

clare.malone: Well, in California, Democrats are also more likely to try to eat their own. See Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s primary challenges. Which seems kinda GOP-y to me

micah: Here’s what Ezra Klein wrote:

What Democrats haven’t adopted is the GOP’s policy intransigence. Where Republicans in the Obama years demanded absurd ransoms — like the complete defunding of the president’s signature legislative achievement — Democrats are asking Trump to accept the kind of deal he said he wanted all along, a deal key congressional Republicans have already embraced. The problem is that Trump refuses to make a deal.

perry: On Klein’s point … I’m not totally sure. DACA and Obamacare are such different issues. Would the Democrats block any Supreme Court nominee from Trump in 2024, if they controlled the Senate? I think so, now that the precedent has been set. I’m not sure. I think the amount of Democratic intransigence will depend on the issue.

natesilver: Maybe about 46 of the 49 Democrats would block any non-moderate Trump nominee? And you’d have some huge fights over the other three.

But, yeah, Republicans set a new precedent on SCOTUS and I don’t think there’s much turning back from it.

micah: But Klein is talking policy, not tactics (which we’ll get to in a sec).

clare.malone: Don’t you think that Democrats have to offer more concrete policy goals? For the more extreme Republican policies, you’d often have people asking to slash a program or slash a budget, you know?

perry: “The problem is that Trump refuses to make a deal.” I think “policy intransigence” is perhaps more of a feature of the Republican Party in general than the Democratic Party. The GOP is the party that believes in less government. I’m not totally sure Trump wants a deal on immigration. He has to say he wants a deal, because that’s what people in Washington are required to say.

I think the Freedom Caucus might prefer no solution at all, leaving the Dreamers in a kind of limbo, over voting for what could be cast as an amnesty, no matter how much border security is in the bill.

micah: Right, and Ezra’s point was that Democrats were still willing to add funding for border security and so on.

harry: I will say I think the House is different than the Senate and seems more liberal and less willing to compromise.

The vast majority of House Democrats voted against the funding bill on Monday.

micah: OK, so let’s talk tactics here.

clare.malone: Send ’em all to Elba.

micah: You could imagine a party getting more extreme ideologically but not more extreme tactically.

But maybe that’s possible in theory but not really in practice? Because Democrats do seem to be getting more extreme tactically, right?

natesilver: I think I agree, although you might want to define “extreme” in this context.

perry: The Democrats had basically a one-day shutdown. They did it reluctantly and stopped it quickly. That suggests to me that they are not ready to take the Republican path in that way. The shutdown was a more extreme move than I think they would have used in the past, but not quite as extreme as the GOP’s shutdown in 2013.

clare.malone: Right, but they’re still baby-stepping away from normal order, right?

natesilver: I don’t think the shutdown entailed much if any political cost to Democrats. It may even have benefited them very slightly because Trump and the Republicans initially took more of the blame, and Democrats conceded before public opinion shifted too much. But the Democrats’ strategy also didn’t seem very well thought-out.

micah: Wait a sec, Perry, why is the Democratic shutdown less extreme than those GOP shutdowns?

Just because it ended more quickly?

perry: Sixteen days versus one day.

micah: But they still pulled the lever.

perry: The Republicans in 2013 had a position with with less than 40 percent public support and had a 16-day shutdown, Democrats had a position with more than 80 percent support and a had a one-day shutdown.

natesilver: There wasn’t 80 percent support for not passing a budget resolution until DACA was resolved, however. That had the potential to be a somewhat unpopular tactic.

harry: In fact, the tactic was unpopular. Per CNN, support for it was below 40 percent.

micah: I guess my point is that either way, they were willing to use government funding as leverage for a policy.

That’s crossing a line.

In other words, the tactic is the tactic — whether it has a ton of public support or none at all.

And the tactic is extreme.

natesilver: Not extreme compared to what Republicans did. Democrats are just playing by the new rules.

clare.malone: Yeah, it’s the rules that the Republicans set. That is, Democrats are slightly uncomfortable with the new paradigm but are learning to exist within it.

Republicans, since the paradigm is of their own creation, embrace its extremism with greater gusto.

micah: I can sign onto that.

natesilver: We arguably haven’t seen too many “innovations” from Democrats yet that Republicans didn’t try first, although former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid killing the filibuster for non-SCOTUS nominees was one of them. With all that said, the filibuster isn’t in the Constitution, so I’m not sure it really qualifies as “extreme” to provide for majority rule in the Senate.

perry: More broadly, on tactics, do I think Democrats will, say, try to pass a bunch of laws that limit voting in a way that is likely to disproportionately affect white working-class voters? I do not. Or refuse to hold congressional hearings if they have an unpopular bill? Probably not.

I think that Democrats are getting more liberal. I’m not sure they will broadly get more aggressive on tactics. And that is likely to create a divide between the base and the party, which has been very visible since they ended the shutdown.

natesilver: Democrats could do more to liberalize voting laws, though. That’s been a pretty big blind spot for the party.

You’re seeing more action along those lines at the state level, however.

See, for example, the ballot initiative to restore felons’ voting rights in Florida that was certified to appear on the November ballot on Tuesday.

perry: Yeah, you might see more Democratic efforts to change political outcomes through policy, as you note. But I think they will be somewhat distinct from Republican tactics (making it easier to vote is different than making it harder).

natesilver: I agree as a matter of principle, Perry — I think there should be a Constitutional amendment to guarantee voting rights for American citizens — but as a matter of practice, expanding or contracting voting rights has long been “fair game” in politics.

I guess what I’m saying is that “extreme” isn’t a very helpful category. It’s more like … how aggressive is a party willing to be in pressing its partisan advantage.

perry: You are seeing more Democrats at the city and state level ignoring or trying to obstruct the goals of the federal government and filing lawsuits against the administration, in the same way that Republicans did in the Obama years.

clare.malone: Nationwide injunctions from liberal-leaning judges against immigration policies, for example.

perry: I get Nate’s point. But, and maybe I will be wrong, I’d bet that Democrats will be less aggressive in pressing partisan advantage, because I think they will be more squeamish about having the press or others criticize them about norms.

micah: OK, final thing I want to talk about: What’s causing the Democratic Party to become more hard-line, ideologically and tactically?

clare.malone: Losing.

micah: Is it …

A shift in the Democratic voting coalition — away from a coalition and toward more of a movement like the GOP?

A shift in the Democratic voting coalition — younger voters are more and more of the base, and more liberal?

Democrats just following Republicans’ lead?

A reaction to Trump?

Losing, as Clare says?

Something else?

natesilver: I think it’s mostly No. 3. Democrats looking at the GOP example and coming to believe that it was a sucker’s bet to not treat politics as a zero-sum game.

clare.malone: I think it’s Nos. 4 and 5. Democrats have tended to get more radically left in reaction to Trump, and they’re embracing hardline tactics because they’ve lost a lot of their power and need to gin up some momentum.

harry: It’s Nos. 3 and 4.

micah: See … I think it’s No. 1.

natesilver: Perry’s comment about Democrats being “more squeamish about having the press or others criticize them” is relevant too. Obama — at least at the start of his term — tried to position himself as a “post-partisan” figure who was Inherently Reasonable and always on the Right Side of History.

I don’t mean to say that Obama had an ineffective presidency overall, but I’m not sure his thesis worked.

perry: I think Nos. 1-5 are all relevant, and No. 6 might be that Democrats have come to view Obama as someone they admire who maybe wasn’t tough enough. And they don’t want to repeat that mistake.

harry: I think they’re all good answers.

micah: Harry is such a wimp.

harry: I’m weak. I admit it.

micah: I’m surprised you all see this as so driven by elected officials, rather than them reacting to voters.

natesilver: Hmm, am I saying that? I think elected officials are mostly leading from behind.

clare.malone: Dude. I wrote, “Democrats have tended to get more radically left in reaction to Trump” — that’s voters!

micah: OK, OK.

Take it easy!

clare.malone: No, gotta stir the pot!

perry: I think its elite-driven.

perry: I doubt that Democrats care about immigration more than Republicans do solely because Democrats have more Latinos in their coalition. White Democratic voters are now more liberal on racial issues, which I think is driven by elites.

natesilver: It may be elites > rank-and-file Democratic voters > elected officials.

clare.malone: Think you’re misreading. I think it’s Women’s March-type groups that have formed (Indivisible, etc.), and the party’s realization that they ignored the progressive base that Sanders appealed to. It’s a culture on the left that’s embraced Black Lives Matter, etc.

And the elected officials are saying, “Oh, progressivism is hot right now!”

It’s grassroots, not elite-driven, in short.

Trickle-up politics.

natesilver: THE HOTTEST CLUB IN THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY IS DEMOCRATIC SOCIALISM!

perry: I view Indivisible as elites, and the women’s marches as led by elites.

natesilver: The modal grassroots Democrat voted for Clinton last year, not Bernie.

harry: And right now Bernie is getting 20 percent or so of the vote in Democratic primary polls.

clare.malone: Right, Nate, …

BUT

She lost.

micah: This is a really good debate and one we should continue. But we’re running out of time. First, I’m realizing I really should have invited Julia Azari to this chat. So, let’s get a quick political science interlude …

Julia, we’ve been debating whether Democrats have gotten more extreme ideologically and tactically (and the consensus seems to be yes). Do you have any thoughts about why that’s happened?

julia_azari (Julia Azari, political science professor at Marquette University and FiveThirtyEight contributor): Yes. I am not sure which ones are correct but let me offer two that are at least not egregiously wrong.

First: Trump. This has already been said. I think as the Democratic coalition gets more diverse and also more attuned to race and immigration issues (because of efforts by activists, which I don’t think was on the original menu), it’s become harder to engage in the kind of racial compromise that’s been common in U.S. political history — as I said in my piece on Friday. (New rule: I get to promote my pieces when I get drafted into a chat at the last minute.)

micah: That’s fair.

perry: lol.

julia_azari: Second: Obama.

The party moved left under Obama for a bunch of reasons. Some are things Obama talked about and emphasized. But I’d also suggest that things that didn’t go as well under Obama — racial injustice wasn’t solved, economic inequality wasn’t either — are important to many Democrats, and that they are still problems post-Obama has led to a push for a different kind of party.

micah: Thank you!

OK, closing thoughts?

natesilver: Since we’re running out of time, I guess I don’t have time to post my troll-ish question about whether Republican tactics have actually been effective.

perry: How are the Republicans not effective? They control everything!

micah: Let’s end on that trollish question, Nate.

natesilver: This is a devil’s advocate case, but one could raise points such as the following: Republicans could have won a lot more Senate seats in 2010/2012 if it hadn’t been for the tea party challenges. They haven’t gotten all that many major policy objectives passed. Republicans had electoral wins — quite a few — but a lot of them come from the Electoral College and from gerrymandering/districting advantages and from the way those things tend to overrepresent the white, rural vote, not the GOP’s parliamentary tactics. And now they have Trump, who may be a one-termer and who may otherwise be a huge liability.

Again, it’s not totally convincing.

But if the GOP gets decimated in 2018 and/or 2020, people are going to think about this era a lot differently.

January 20, 2018

Emergency Politics Podcast: Shutdown!

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

The government shut down early Saturday morning after the Senate failed to pass a stopgap spending bill. The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast crew discusses the political repercussions of past government shutdowns and whether this one will be any different.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

January 17, 2018

What Was Most Surprising About Trump’s First Year?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): Welcome, everyone, to our final chat before the one-year anniversary of President Trump’s inauguration!!!

Or is it just “the anniversary of President Trump’s inauguration”?

In any case … we’re going to mark the occasion by looking back on what’s been most surprising about Year One of the Trump epoch.

My first question: What did Trump do in his first year that you found the most surprising?

Nate, you answer first.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): I was surprised by the lack of surprises.

micah: That’s a cop-out.

natesilver: It’s also super annoying, like when people ask you what your greatest weakness is in a job interview and your response is, “I’m too hard on myself.”

micah: I’m a perfectionist.

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): I’m gonna call bullshit here. You did NOT foresee him firing FBI Director James Comey.

micah: (I love when things get acrimonious less than three minutes into a chat.)

clare.malone: Actually, I went back and looked at a timeline of events, and I agree with Nate to a certain extent — a lot of the things I was surprised at weren’t policy things, but modes of communication things.

natesilver: Of course there have been some surprises, but there have been fewer surprises than I would have thought.

micah: Well then … WHAT WAS THE MOST SURPRISING?!?!?!?!?!?

natesilver: I mean, Comey does come to mind. Plus a Democrat winning a U.S. Senate race in Alabama.

And maybe how explicit the saber rattling toward North Korea has been, which sometimes reads like a bad parody.

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Well, I’m not surprised Trump reneged or didn’t follow through on some campaign promises, but I guess the fact that he really has moved to the right and capitulated so easily to congressional Republicans on policy is at least a little surprising to me.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): Yeah, I was surprised that he largely, on policy, governed as a President Ted Cruz or a President Marco Rubio would have. He really was a Republican president on policy, except on a few issues. I expected more populism, a less-traditional GOP foreign policy, maybe infrastructure or a health care bill that was not as conservative.

clare.malone: My most-surprising Trump actions are: his North Korea tweets, his both-sides response to the white supremacist attack in Charlottesville, Virginia, the Anthony Scaramucci hiring and firing (what a fun week!), the Comey firing, and the immigration shutdown in his first week.

natesilver: See, I’d put Charlottesville on the list of the least surprising developments.

perry: I was also surprised by the racial stuff, which he said during the campaign but I assumed he did not really mean. I thought the race-baiting was just a way to win the primary. But the travel ban, the immigration raids, the NFL stuff, Charlottesville, and the recent shithole/shithouse episode all suggest otherwise.

clare.malone: On his Charlottesville response … I dunno. It felt different from the times during the campaign when he flirted with racist themes. It felt more explicit and weird.

harry: IDK … I think Trump’s rhetoric has remained fairly constant, while his positions on issues have seemingly changed. I guess I shouldn’t be surprised by that.

natesilver: Trump has flirted with sympathy toward racist conduct all his life.

micah: Yeah, as Perry said, I guess it comes down to whether you thought Trump’s race-baiting during the campaign was political calculation or genuine.

We have to conclude it’s genuine now, right?

natesilver: That’s probably what we should have concluded before also, though.

perry: I might say I was hoping it was not genuine.

So maybe that changed my expectations of it.

micah: I mean, I’ve always been of the feeling that it doesn’t matter whether it’s genuine or not. The actions are what matter. If someone punches you in the face and breaks your nose, but it was an accident … well, you still have a broken nose. And if they accidentally punch you in the face over and over again …

natesilver: There’s a tendency in the media to assume politicians’ behavior is strategic instead of sincere.

clare.malone: So … I don’t think people thought he wasn’t racist. People thought he would be more restrained in the Oval Office, probably.

perry: Right. That is what I expected. Wrongly.

harry: To Clare’s point, most people thought Trump was racist during the campaign.

clare.malone: Maybe that’s a surprising thing, to Perry’s point — how disorganized the White House is.

natesilver: I mean … part of the problem with this framing is that there’s like a normal range of uncertainty, and I think he’s within that normal range for the most part.

It wasn’t totally out of character for Trump to fire Comey, for instance, even though you might not have predicted it specifically. And his lack of restraint also had lots of precedent on the campaign trail — and throughout his life — even though your median expectation might be that he would have checked himself a little more.

harry: Dare I say that people thought there would be some sort of pivot, and there hasn’t been?

perry: Obviously, yes, I expected this White House to be topsy-turvy, which is why I did that “power centers of the White House” piece. But the firing of the communications director so quickly, the chief of staff who lasted less than a year … the year has been a bit beyond “topsy-turvy.”

clare.malone: Yeah, remember those “wings” we talked about so much?

natesilver: People who said we ought to take Trump “seriously but not literally” should be pretty surprised. We aren’t those people, though.

micah: I guess that would be my answer to what’s been most surprising: That the normal Republicans have seemed to lose so much power in the White House, and yet at the same time normal Republicanism has won the day policy-wise.

I wouldn’t have predicted both of those things happening together.

There’s an unbelievably big gap between Trump rhetoric and Trump policy.

natesilver: Maybe because his appeal wasn’t based on “economic anxiety” to begin with? (Although, then again, maybe it was, which is why he’s so unpopular.)

harry: Congressional Republicans are controlling what they can control. They pass the bills they want and tell Trump to go you-know-what himself on bills they don’t want.

micah: OK, next question …

What have you been most surprised hasn’t happened?

natesilver: Perhaps the lack of economic protectionism, trade wars, etc.

clare.malone: Yeah, I continue to find it fascinating that Trump got convinced to follow House Speaker Paul Ryan’s agenda, not his own, on, e.g..e., trade stuff, infrastructure.

natesilver: Another one: Trump’s response to terror attacks, like the one in New York City in October, has been relatively restrained compared to how I might have expected him to react.

micah: I guess I also think the fact that Trump hasn’t sparked a trade war is the most surprising — I agree with Nate.

harry: I find the lack of a breakdown in Trump/Ryan relations kind of surprising. Ryan, if you remember, didn’t endorse Trump right away. And yet, Trump’s biggest problems seem to be with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

micah: That’s a good answer.

clare.malone: Well, if we believe the Ryan retirement rumors, that relationship might not be too long for the books

natesilver: I wouldn’t go overboard in declaring it a great relationship. They got a tax bill through, but not much else.

harry: They would have gotten a health care bill done if McConnell had come through.

micah: This kinda gets us into my next question …

What have congressional Republicans done in Trump’s first year that you’ve found most surprising?

natesilver: See, on this point I’m gonna really stick to my guns and say I’m not surprised by the Congressional GOP’s reaction to Trump. It’s about how you’d expect them to calibrate it given high partisanship on the one hand, but lots of private concerns about Trump on the other hand — and his also being very unpopular.

perry: The amount of time the GOP spent on health care was surprising, once it became clear in March that the members didn’t really want to vote on Obamacare and had always been talking a big game on repeal without any real plan to do it. The fact that they came back to it in September was bizarre, looking back.

clare.malone: It’s boring, but I’ll echo that the health care failure was the most surprising.

micah: Harry and Nate?

harry: I’m surprised by how cozy Sen. Lindsey Graham has been with Trump, while Sen. John McCain has, well, not been.

natesilver: I was surprised that GOP members of Congress from California, New York and New Jersey didn’t do more to protest the capping of the state and local tax deduction. That’s a pretty obscure one, though.

perry: I think — and I know there a lot of people who view Congress as only enabling Trump — that Sen. Richard Burr inviting Comey to a major hearing (after Trump fired Comey) and generally defending him was actually a fairly big slap at the president of his own party. Senators have backed up the Russia investigation in a lot of important ways, especially compared to House members. The gap between Rep. Devin Nunes (very pro-Trump in terms of Russia) and Burr is interesting.

natesilver: Overall, the Republican Congress has not always turned the other cheek toward Trump. Although the most important decisions it might make are still ahead of it. (What happens if Trump tries to pardon Jared Kushner, for example?)

micah: IDK … the extent to which congressional Republicans have let Trump get away with stuff depends on the issue. I agree that Senate Republicans have done some real stuff on Russia (relative to the House, at least), but what about on Trump family business stuff/conflicts of interest?

harry: The House has been more supportive of Trump, it feels. That’s interesting if only because there’s a higher shot that they lose their majority because of Trump.

clare.malone: How do congressional Republicans act post-midterm?

micah: Clare is really asking the million-dollar question, right?

Let’s say Democrats win the House but not the Senate.

Which seems like the modal outcome.

natesilver: I mean … the thing people get wrong — because it feels like Trump has been president forever — is that it’s still really early.

harry: It feels like no time at all to me, to be honest.

perry: In this era, I’m not sure running away from the president of your own party really ever makes sense. Fox News and other parts of the Republican Party enforce discipline. The moderates in the GOP will be the ones who lose in the midterms. I think the remaining House Republicans will stand with Trump pretty closely. Senate is different.

clare.malone: So here’s my scenario: Let’s say the Democrats win the House and vote to impeach Trump. Let’s say the GOP holds the Senate, but by a very slim margin. Do they vote to impeach in the Senate? Get a President Pence?

perry: No. Not a chance.

natesilver: Yes, a chance.

clare.malone: Because they think they would lose in 2020, Perry? Lose the base?

micah: It all depends on what he’s getting impeached for, doesn’t it?

perry: Well, if Trump called Putin in July 2016 and said, “Hack Podesta’s email on Sept. 12,” then yes. But based on the information we have right now, not a real chance.

micah: Right, I think it would take something toward the more extreme end of potential findings.

natesilver: What if Trump fires the special prosecutor or pardons his son-in-law?

micah: No.

natesilver: I just don’t think there are a lot of useful precedents for Trump, so predictions that he won’t be impeached seem overconfident.

People need to default more toward an uncertain prior.

micah: I’m just judging based on how congressional Republicans have been reacting to smaller stuff and scaling up.

natesilver: Also, I think the mentality changes a lot after a big Democratic wave election, if there is one.

harry: I’ll just say what I’ve always said: The chance of impeachment is underrated and the chance of conviction is probably overrated.

natesilver: I mean … it’s more likely than not that Trump gets impeached, right?

micah: I’m not sure of that.

harry: There’s a pretty good shot, but that’s a rather bold statement.

clare.malone: Well, it’s basically like answering the question of whether or not you’re confident in a Democratic House wave in 2018.

perry: So Democrats are likely to win House. Correct. There will be a huge push from liberal activists for impeachment.

Is that 50 percent? Let me think about that.

natesilver: Let’s say a 65 percent chance of Democrats winning the House, which is about where betting markets have it. Conditional upon their winning the House, what’s the chance Trump gets impeached? Maybe 75 percent? Plus a small chance that he does something so egregious that even if Republicans hold the House, they impeach him. I think you come out at about 50 percent or a bit higher.

perry: I think Rep. Nancy Pelosi and some of the more cautious Democrats will feel that Trump is very unpopular, and beating him in 2020 is a safer bet than trying to remove him.

I don’t know if that view will win out, but that will be the D.C. strategist view. And she listens to those people.

micah: What do betting markets peg impeachment at?

natesilver: Betting markets say there’s about a 45 percent chance Trump doesn’t finish his term, which is probably too high. But impeachment (setting aside the conviction/removal part) is fairly likely.

clare.malone: What if Pelosi isn’t speaker?

perry: I think this gets to an interesting question. If the Democrats win the House, will they only elect a pro-impeachment person as speaker?

micah: Fair question, but I have to steer the convo in another direction …

clare.malone: Boooooo!

Thank you for engaging, Perry!

micah: What have congressional Democrats done that has most surprised you?

harry: Total blockage. They’ve learned their lesson from the Republicans during the Obama years. It’s no-holds-barred.

micah: But is that surprising?

clare.malone: Yeah.

You’re surprised by total blockage?

What other option did they have?

micah: None, I don’t think. We haven’t really seen Trump or Republicans put them in a position where deal-making is really even an option.

clare.malone: If it were a different GOP president, maybe, but the Democratic base is out for blood with this one.

harry: I guess I thought there would be more compromising from the moderate Democrats in the Senate. Perhaps that was conditional on Trump having governed differently policy-wise in his first year (not as typical GOP president).

micah: Right, that last part hasn’t happened.

clare.malone: I guess there is the banking regulation stuff.

natesilver: Yeah, that’s an underrated surprise, I think. How rarely the moderate Democrats have lined up with Trump on key issues.

At the same time, I think people might underrate the likelihood of a Trump attempt to p—t if Democrats win both chambers of Congress in November.

micah: OMG

Nate, I expect more from you.

natesilver: See, the very fact that it’s socially unacceptable to suggest Trump might p—t is a good reason to think he might p—t.

I’m not saying it would be a particularly competent p—t. But could he agree to pass a big infrastructure bill with mainly Democratic votes? Sure.

micah: It’s only socially unacceptable here.

natesilver: No, you’ll get ratioed on Twitter too.

harry: Pivot.

There, I said it.

natesilver: One could argue that Trump’s legislative affairs strategy has been expedient. He wants “wins,” doesn’t want to crash the stock market, and otherwise doesn’t care too much about the details of domestic policy. So why wouldn’t he deal with Pelosi/Chuck Schumer, if it’s a bill that he thought business interests would like and that he thought might make him more popular?

micah: Why hasn’t he done that yet?

perry: Democrats have been more unified than I expected, as Nate is hinting at. I figured splitting the more moderate Democrats like West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin from the more anti-Trump liberals like New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand would be easy. It might be for a more competent White House — Bush did it in 2001.

micah: Last question …

What has the media done that’s most surprised you in Trump’s first year?

harry: How openly anti-Trump the coverage has been.

micah: In a good way or a bad way?

clare.malone: Yeah, I actually think I’m basically on that wavelength. It’s interesting how adversarial the media has been, but I think that’s almost a reaction to what they think the reading/watching public wants? Like, when The New York Times reporter got pilloried for the way he interviewed Trump — that really surprised me. (I don’t have time here to get into how people expect print interviews to be the same as TV ones and it’s not the same skill.)

natesilver: I mean, I have some relatively petty gripes here, mostly related to the election. I’m continuously surprised at how a certain major publication that got a whole lot wrong in 2016 hasn’t really owned up to it. And I’ve been surprised that there hasn’t been more self-reflection from the media about how it treated Hillary Clinton and the email stories. But I actually don’t have that many complaints about how the media handled Trump’s first year in office. It has, for the most part, been trying to evolve.

clare.malone: What you’re getting at — that people haven’t reflected on 2016 coverage — is why coverage is more adversarial. I mean, it also should kinda go without saying at this point that this is a really unusual White House and the president lies a lot/makes a lot of claims that people need to push on.

natesilver: I also think coverage has gotten better over the course of the year. Like, the media seems more willing to deal with the reality of Trump’s attitudes toward black people than it was back in April or May of last year.

perry: Interesting. I actually think some parts of the traditional media (let’s say CNN’s Jake Tapper and Don Lemon, and The Washington Post at times) have been fairly direct describing Trump’s racial moves in an honest, straightforward way. People are saying “racist” when it applies.

clare.malone: But especially in the first weeks, it felt like some stories lacked context.

perry: Harry is right: The coverage has been more anti-Trump than I expected. I think much of it is appropriately anti-Trump, but the shift from kind of “both sides are at fault” coverage has been more pronounced than I expected.

Another thing: There has been some outstanding work from less well-known reporters because there is so much news happening, so there is more opportunity for new voices to emerge, which is good. Some example: the coverage of Trump’s immigration policies from Vox’s Dara Lind; Josh Dawsey at the Washington Post (who broke the shithole story); and Eric Lipton of the NYT’s coverage of the federal agencies under Trump.

micah: Closing thoughts?

perry: I found 2017 totally odd. I didn’t think Trump would be this traditionally Republican on policy. I didn’t think I would write basically a whole series of articles about how he played racial politics constantly. The president having to say, “I am not a racist,” (and reporters feeling compelled to ask him about it) was something I didn’t expect. Even for Trump, the staff upheaval was wild. I didn’t think Doug Jones would win in Alabama until it was called for Jones in Alabama. I expected the Obamacare repeal to pass, and the tax cut to pass with Democratic votes. 2016 was of course stunning on a bunch of different levels. I think 2017 was not that surprising by that standard. But it was unpredictable. McCain voting down a health care bill!

natesilver: I think 2017 (Trump as president) was less surprising than 2016 (Trump winning the general election), and 2016 was less surprising than 2015 (Trump rising to the top of the Republican Party in a field of 17 candidates).

perry: I agree with that. Well said.

micah: So things are getting less and less surprising!

clare.malone: #thenewnormal

perry: And in 2018, if the out party wins the House, it will be downright normal.

harry: 2017 felt normal to me.

micah: OK, on let’s end things on that ridiculous statement.

perry: LOL

harry: LOL

January 16, 2018

Politics Podcast: Immigration Showdown

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Democrats and Republicans are at an impasse over immigration policy, with a potential government shutdown looming. Anna Maria Barry-Jester joins the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast crew to talk about the partisan divisions at play and whether an agreement is likely.

The team also weighs Democrats’ odds of winning the Senate this fall, after Nate wrote an article arguing that their current chances could be overrated.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 730 followers