Nate Silver's Blog, page 90

February 26, 2018

Politics Podcast: A Turning Point In The Guns Debate?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

A series of polls shows record support for stricter gun laws in the U.S., so the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team discussed whether the public reaction to the mass shooting at a high school in Parkland, Florida, reflects a turning point in the guns debate. The crew also entertains hypothetical political scenarios in a round of political “Would you rather.”

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

February 21, 2018

Does America Want A Third Party? (Or Is It Just David Brooks?)

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): Greetings, people. Today we’re going to have a super nice and respectful chat about a recent column from David Brooks of The New York Times.

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): …

Nate drank his Gatorade.

micah: The column: “The End of the Two-Party System.” Can someone give us a fair summary of Brooks’ argument?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): The summary is that we need the Reasonable Center Party, which happens to have exactly the same policy positions that Brooks has and would be enormously successful if only anyone bothered to create it.

micah: I said “fair.”

clare.malone: Brooks brings up the rise of basically what he’s categorizing as tribal politics, and compares it to European trends from the late 1990s and early 2000s.

He says that, at some point, conservatives and liberals will split themselves between true philosophical conservatives and liberals, and then the people who are the tribal conservatives and tribal liberals.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): A more generous summary might be that Brooks feels the Republican Party is too Trumpish and the Democratic Party is too stuck on race- and gender based-politics, and we need another party for people who don’t like those two ideologies.

micah: OK, I don’t want this chat to just be bashing Brooks’s argument; I want to talk about third parties. So let’s get the argument-demolishing out of the way …

There’s a ton wrong in this article, right?

natesilver: I mean, the main problem is that he doesn’t understand how parties work.

Which is a pretty big problem if you’re writing a column about parties.

I like Brooks, by the way (I really do) — this just wasn’t one of his best efforts.

perry: So, first, he points to the good old days of the 1990s. But as Julia Azari has written, we’ve always had very intense political conflict, it’s just more partisan now. Moreover, the 1990s were not great — as we knew back then but are learning more now — if you were, say, a woman trying to advance in many fields or an African-American who dealt with the criminal justice system.

Second, the pre-Trump Republican Party he describes skips over the racialized politics of, for example, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan.

micah: Yeah, this description of the GOP seems waaaaay off:

In the years after Ronald Reagan, the Republican Party was defined by its abundance mind-set. The key Republican narratives were capitalist narratives about dynamic entrepreneurs and America’s heroic missions. The Wall Street Journal editorial page was the most important organ of conservative opinion. The party’s views on other issues, like immigration, were downstream from confidence in the abundant marketplace and the power of the American idea.

What about all the racialized law-and-order stuff?

clare.malone: My real problem with the article is that he doesn’t really prove his case.

He says at the very end of it, in a single paragraph:

Eventually, conservatives will realize: If we want to preserve conservatism, we can’t be in the same party as the clan warriors. Liberals will realize: If we want to preserve liberalism, we can’t be in the same party as the clan warriors.

But wait … will they realize this? What about hyper-partisanship? And check this out from Pew:

natesilver: The article also skips over the importance of “values voters” and the evangelical movement to the George W. Bush coalition. (And to the Reagan coalition too.)

micah: But, Nate, explain how you think the article misunderstands how parties work.

natesilver: Du. Ver. Ger’s. Law.

Bam!

OK, that’s a pretty obscure reference. But its point is that party systems are heavily influenced by electoral structures.

You usually get two major parties, or maybe three, in first-past-the-post systems like the U.S. uses. Those European systems he’s talking about — where you have lots of viable parties — mostly have proportional representation.

It should really be “Duverger’s reasonably reliable empirical regularity” and not “Duverger’s law,” but it’s a pretty useful heuristic.

clare.malone: What a sentence.

My question is, when does Brooks think all of this is going to happen?

That is, is this something he thinks will come down the pike in 2020 (aka, David Brooks is a stan for Kasich 2020)?

Or is this something 25 years in the future?

natesilver: It will happen once more people read his columns and join the Reasonable Center.

micah: OK, so he sorta bungles parties and bungles recent U.S. political history, but let’s talk about the force he thinks will spur a viable third party …

Isn’t his argument like: People are getting really partisan and so therefore people will break out of partisanship?

That seems … wrong?

Or am I misunderstanding the argument?

natesilver: It’s not necessarily wrong to think that partisanship could abate. It does tend to ebb and flow. And it’s at a high end of the historical range now.

clare.malone: It’s really hard to build a party structure — state-level offices/organizers/money — which is one of the reasons that people tend to stay within the two major parties.

Like, if you wanted to launch a legitimate third-party bid, it would not be something that could happen overnight. The Libertarian Party has been trying for decades, and they’ve only recently been racking up margins that made a dent.

natesilver: And/but/also, the two-party system is pretty adaptable. Does the Republican Party under Trump look a lot different than the Republican Party under Reagan? Sure. But that’s why parties work!

clare.malone: Right. Parties shift priorities. The modern Republican Party emerged under Herbert Hoover. So maybe it won’t break apart now, it’ll just shift to a new iteration.

perry: I was thinking out loud about this before the chat, but the last new, big major party in America was in the 1850s, right? Lincoln’s Republican Party. It replaced the Whigs in many ways.

Trump’s rise is a major crisis to Republicans like Brooks and lots of other scholars who view Trump as kind of the worst possible type of president. So the idea is a Gov. John Kasich-like figure rises to create a new kind of party that is an alternative to Trumpism. I didn’t think that was impossible in October 2016. But it seems much more implausible now, since Republican voters broadly like Trump and it’s not clear that stopping Trump is some clarion call for people outside of the Democratic Party and the Acela corridor.

micah: Yeah, so that’s key: Is there demand/desire among Americans for a third party?

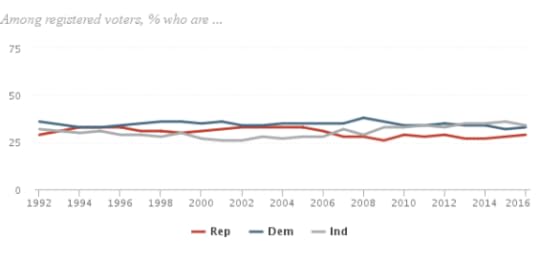

natesilver: Again, a lot of this is just that David Brooks had a party (the GWB-era GOP) that he once mostly agreed with and now he doesn’t have one. Which is annoying for David Brooks but doesn’t really provide much evidence either way in terms of broader public sentiment. There’s been a gradual uptick in the number of people who identify as independent, but it’s really quite gradual and quite mild:

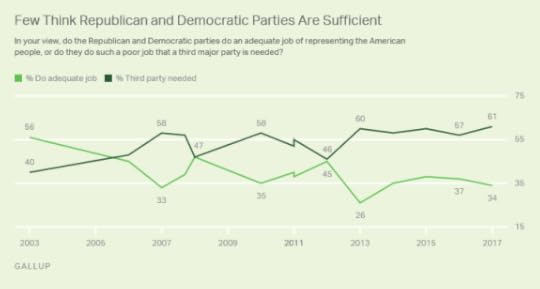

micah: But that’s party identification … people do say they want a third party!

perry: I think there’s demand for changes in politics: a more populist economic strain and a more nativist strain. But it feels like the former is happening in both parties (Trump, Bernie Sanders) and the latter in the GOP with Trump.

In other words, we are seeing huge changes in politics, but they are within in the parties. (And in the opposite direction of where Brooks is, since he is not populist or nativist.)

natesilver: Yeah, exactly. Basically, Brooks is a Democrat now and doesn’t want to admit it.

micah: Explain that Gallup chart though.

clare.malone: I do think it’s fascinating that Americans say they want a third party.

And yet … where is it?

Maybe if the U.S. had less money involved in politics, you’d see more parties.

natesilver: I wrote something once about how Trump himself was essentially a third-party candidate. His platform during the campaign was quite different than John McCain’s or Mitt Romney’s — although he has arguably governed as a much more traditional Republican.

But part of the issue that Americans don’t want a third party — they want their third party.

perry: So, here’s a smarter take on third parties from Lee Drutman at Vox:

Yes, third parties in American politics are kamikaze missions. Because of our single-winner plurality system of elections, third parties almost never gain representation.

And yes, a serious third-party conservative challenge to Republicans would help Democrats in the short term, by siphoning off votes from Republicans.

But each month that the Republican Party has a leader who can’t conceal his overt racism, who calls the media the enemy of the people, is a month in which voters who identify as Republican have to update their worldview to fit with their partisan identity. Only losing, and losing bigly, will break this Republican partisan trajectory.

One more excerpt from Drutman:

Perhaps you like the idea of starting a Conscientious Conservative Party, but don’t like the idea of losing and tipping the balance of power decisively to Democrats. In that case, maybe you could get on board with changing electoral laws to make it easier for third parties.

Perhaps you could get behind the Fair Representation Act, introduced last year in the House, which would move us toward a proportional voting system by creating multi-member districts with ranked-choice voting. That means that even if the Conscientious Conservative Party could only get about 15 percent nationally, it would get some seats in the House — possibly enough to be a pivotal voting bloc for control of the chamber.

Or if that feels too bold, how about just straight-up ranked-choice voting, which would give people the chance to vote for the Conscientious Conservative Party and then list either the Democrat or the Republican as their second choice, ensuring that they could express their true preference without wasting their vote, and putting some pressure on both Democrats and Republicans to court Conscientious Conservatives to earn their second-choice votes.

The point is, third-party votes don’t have to be wasted votes. They’re only wasted votes because our electoral system makes them so.

natesilver: Yeah, look, I don’t want to go overboard in totally dismissing the idea of a third party. Also, independent presidential candidates can sometimes succeed irrespective of a more sustainable third party.

But as Perry says, a lot of the changes happen within parties. And independents fall into maybe three different categories — including lots of people on the “far left” and the “far right,” not just Reasonable Centrists.

micah: No one has yet explained to me what gives with that Gallup chart, though. If 61 percent of people think a third party is needed, what’s getting in the way?

Brooks is speaking for the masses!

natesilver: Because among that 61 percent, there’s 21 percent who want the Reasonable Center Party, 20 percent who want the Green Party, and 20 percent who want the America First Party

clare.malone: I mean, there’s no high-profile candidate from a third party. Jill Stein and Gary Johnson are too fringe. And their parties don’t have enough money. So no one except people who read sites like FiveThirtyEight ever vote for them.

micah: Don’t stereotype our readers!

clare.malone: Sorry, readers.

micah: Let’s do a poll.

If you're a @FiveThirtyEight reader, please answer this question:

Have you ever voted for a third party?

— Micah Cohen (@micahcohen) February 15, 2018

Anyway, how could we get more parties? Structural change, as Drutman wrote?

perry: I think so — it’s the structure of our electoral system that gets in the way.

natesilver: Yeah, see, Brooks should really be writing about the need for ranked-choice voting.

You’d probably wind up with slightly more fluid, centrist parties, although maybe not with more parties.

perry: Well, the parties would have to vote for structural change, and I don’t see that happening.

I think I could see an Emmanuel Macron-style situation happening in the U.S.

clare.malone: Macron is basically a Michael Bloomberg type but with less experience. Way less.

natesilver: Yeah. I’d put the odds of “independent candidate wins one of the next four presidential elections” quite a bit higher than “there’s a new major party within 16 years.”

perry: If, say, Sanders and Trump are the nominees in 2020, could the Reasonable Centrist Party do better? Macron is a centrist in policy but has a personality cult around him. Or had one.

clare.malone: I mean, if Sanders wanted, he could lean into the Democratic Socialist Party thing and try to build that out. It probably wouldn’t yield him the presidency in his lifetime, but it would perhaps bear fruit decades down the line. A delayed-gratification legacy.

micah: Sanders doesn’t seem the type for delaying gratification.

perry: Take Arnold Schwarzenegger in California in that very odd California 2003 environment. I felt like he could have won as an independent.

natesilver: But in the case where Sanders has won the Democratic nomination, he’d look like a more “traditional” Democrat by the time the general election rolled around. And the Democratic Party is moving in his direction anyway.

clare.malone: Right. Sanders realized that you need the big party in order to succeed. Even if you hate their guts.

natesilver: Could someone more radical than Sanders win the Democratic nomination? Maybe. Or a Sanders who also had lots of personal liabilities?

micah: OK, so if we all think that it’s much more likely that one of the two major parties will shift in a big way than that a third party will emerge, what could that shift(s) look like?

perry: Those shifts already happened to some extent. And the people who lost out on the them are the Jim Webb types in the Democratic Party and the Bill Kristol/Brooks types in the GOP.

micah: One hundred percent agree on GOP, but are we really ready to declare the Democratic Party fully shifted too?

In other words, is asymmetric polarization more symmetrical now?

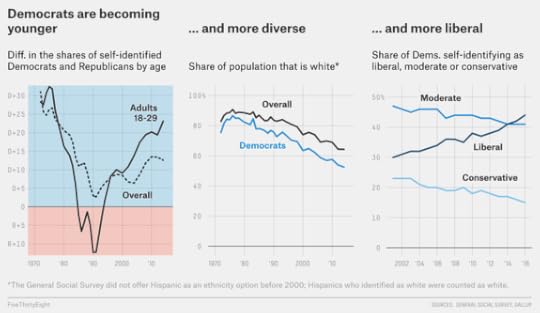

clare.malone: Oh, Democrats got stuff a-brewing — though because they lost, it’s a less dramatic fight. But the party, in addition to some demographic changes, is much more liberal than it used to be:

natesilver: Neither party has fully shifted, but the Democratic Party is earlier in its process of shifting, I think.

perry: I’m just having a really hard time seeing the Kristol/Brooks wing retaking the GOP. I think, like Nate said, those people are basically Democrats now. And they should try to push the Democrats to be less-identity-ish.

natesilver: In terms of the Democratic Party shifting, the key question isn’t, “What does David Brooks want?” but, “What do young black and Hispanic voters want?”

micah: So, yeah, you two just identified the tension there, right?

clare.malone: Big ol’ tent, huh?

Big enough for Brooks and Kristol.

micah: It would have to be a huge tent!

Brooks describes the Republican Party of the 1980s without one mention of race — getting Brooks-esque voters in the same tent with liberal Democrats is gonna be tricky.

clare.malone: I mean, those guys are basically European conservatives, to go back to the Brooks point about European politics. And their being in the party for a while could, in 10 years, push the more left-leaning people to start their own thing.

Eventually the tent will get too crowded and some people will have to go to the overflow section.

natesilver: Right now, opposition to Trump unites white urban neo-liberals with white democratic socialists with black and Hispanic voters. You’d have a lot of tensions within that coalition down the road, though.

perry: Brooks and the other conservative anti-Trump voices have resonance, in part, because some Democrats at the elite level are wary of the identity stuff too but can’t say so publicly. (Let’s say Sanders and Biden, if you look at their immediate post-election comments.) But I think a party that is only about 25 percent white men doesn’t really care what Brooks thinks. The Democratic Party is going to get more Sanders-like, I think, in the short term. And this is going to frustrate people like Brooks, who should become Democrats. But could Biden win the 2020 nomination on a kind of unity platform? Maybe.

It feels like Brooks’s best hope is that the Democratic Party, in some kind of “Save America from Trump” move, embraces a style of politics that Jeff Flake, John McCain, etc., agree with but does not piss off young voters, minorities, women, socialists, Sanders types.

In other words, the parties really sort along immigration lines — the people with Trumpish views on race/immigration in one party, the others in a second party.

natesilver: Obama, in some ways, united all these different groups together in 2008 because George W. Bush was so unpopular. So if Trump is really, really unpopular by 2020, a Biden type could do great.

In the long run, I don’t think you can avoid these tensions, though.

perry: That’s a great point. The 2008 Obama campaign was a kind of unity ticket. He couldn’t recreate that in 2012.

micah: OK, and to wrap up: Is there any chance that the Republican Party becomes the party Brooks wants it to be?

clare.malone: That’s a negatory. At least in any sort of near-term future. I don’t think you can just forget about the forces in the party that manifested Trump.

perry: If Trump and Putin had a July 2016 phone call during which Trump told him to hack Podesta’s email, that call becomes public and Trump is impeached and removed from office … then maybe.

micah: See, I disagree with that, Perry.

perry: You think Putin made the hacking suggestion first?

micah: LOL.

The Trumpism in Republicanism predates Trump and — to a first approximation — would postdate him too, wouldn’t it?

natesilver: I’m on Perry’s side. If Trump is perceived to be a failure, there could be a reasonably sharp counterreaction to Trump. (Although, I’m thinking “failure” more in the sense of “he loses re-election,” not “he gets impeached,” which raises a different set of issues.)

micah: So, if Trump loses re-election, Republican primary voters suddenly move to the middle on immigration?

natesilver: STRAW MAN MICAH IS BACK

micah: Whose team are you on, Clare?

clare.malone: I’m not sure about my team. I guess I could see, in the case of a Trump flameout, Trumpians getting completely steamrollered by national establishment figures.

But then you’ve got a part of your base that is wildly unhappy with you. I guess they either leave or just become pains in your asses for the rest of time.

I’m not sure I’m on a team. I’m agnostic.

natesilver: Voters (maybe not voters in the GOP, but voters overall) are already moving left on immigration. The reaction to Trump has been fairly thermostatic, as the political scientists like to say.

micah: What does thermostatic mean?

natesilver: Public opinion tends to move in the opposite direction of the president’s policy preferences.

perry: But while I don’t think the Republican Party will change in the short term, I don’t rule out a strong third-party candidate doing well in 2020. There is some broad dissatisfaction with American politics that someone could capitalize on. Someone more like Oprah than Kasich, but I think it won’t be either one of them. I don’t know who that person is.

micah: OK, I’ll say this: Partisanship is sooooooo strong now that maybe it allows for more ideological/policy movement and flexibility. We’ve seen Democrats and Republicans flip on the FBI. We’ve seen Republicans flip on free trade, Russia and Putin.

So, in that sense, maybe it’s easier to imagine the GOP becoming more to Brooks’ liking pretty quickly.

If, in three years, a set of circumstances comes together so that the “right” set of partisan positions for Republicans is Brooks-ian, I don’t really have much doubt that partisan voters would support those positions — in the same way Republicans became anti-free-trade almost overnight.

clare.malone: I’ll buy that somewhat.

The FBI thing is really interesting. A good point.

perry: That’s a good ending point, I basically agree with Micah’s take there.

natesilver: Yeah, I hate to say it, but I basically agree with Micah too. The very intense partisanship we see in the country today is a sign that the parties are quite healthy, whether or not it’s good for democracy.

micah: OMG!

Let me just marinate in this moment for a little while.

February 20, 2018

Politics Podcast: The Gun Debate

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

In the wake of a mass shooting at a high school in Parkland, Florida, the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast devotes an entire episode to the debate about guns in America — what the public wants, how the politics of guns have changed and what Washington will do. Jill Lepore, a Harvard professor and staff writer for The New Yorker, joins to discuss how the National Rifle Association has affected views on gun rights since the 1970s.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

February 16, 2018

How Much Did Russian Interference Affect The 2016 Election?

One of my least favorite questions is: “Did Russian interference cost Hillary Clinton the 2016 election?” The question is newly relevant because of special counsel Robert Mueller’s indictment of 13 Russians on Friday on charges that they used a variety of shady techniques to discourage people from voting for Clinton and encourage them to vote for Donald Trump. That doesn’t necessarily make it any easier to answer, however. But here are my high-level thoughts in light of the indictment. (For more detail on these, listen to our emergency politics podcast.)

1. Russian interference is hard to measure because it wasn’t a discrete event.

You know what probably did cost Clinton the election? The letter that former FBI Director James Comey sent to Congress on Oct. 28, 2016, and the subsequent media firestorm over it. The impact is relatively easy to measure because it was the biggest news event in the final two weeks of the campaign, and we can compare polls conducted just before the Comey letter to the ones conducted just after it.1

Russian interference isn’t like that. By contrast, the indictment (and previous reporting on the subject) suggests that the interference campaign had been underway for years (since at least 2014) and gradually evolved from a more general-purpose trolling operation into something that sought to undermine Clinton while promoting Trump (and to a lesser degree, Bernie Sanders). To the extent it mattered, it would have blended into the background and had a cumulative effect over the entirety of the campaign.

2. The magnitude of the interference revealed so far is not trivial but is still fairly modest as compared with the operations of the Clinton and Trump campaigns.

The indictment alleges that an organization called the Internet Research Agency had a monthly budget of approximately $1.25 million toward interference efforts by September 2016 and that it employed “hundreds of individuals for its online operation.” This is a fairly significant magnitude — much larger than the paltry sums that Russian operatives had previously been revealed to spend on Facebook advertising.

Nonetheless, it’s small as compared with the campaigns. The Clinton campaign and Clinton-backing super PACs spent a combined $1.2 billion over the course of the campaign. The Trump campaign and pro-Trump super PACs spent $617 million overall.

In terms of headcounts rather than budgets, the gap isn’t quite so dramatic. The “hundreds” of people working for the Internet Research Agency compare with 4,200 paid Clinton staffers2 and 880 paid Trump staffers.3 Russian per-capita GDP is estimated at around $10,000 U.S. dollars — about one-sixth of what it is in the U.S. — so a $1.25 million monthly budget potentially goes a lot farther there than it does here. The Russian efforts were on the small side as compared with the massive magnitudes of the campaigns, but not so small that you’d consider them a rounding error.

3. Thematically, the Russian interference tactics were consistent with the reasons Clinton lost.

How did Trump win? Or more to the point, how did Trump win given that he only had a 38 percent favorability rating among people who voted on Election Day? The answer is partly the Electoral College, of course. But it’s also that Clinton was really, really unpopular herself — almost as unpopular as Trump — with a favorability rating of just 43 percent among Election Day voters. Also, the substantial number of voters who disliked both Clinton and Trump went to Trump by a 17-point margin. Voters really weren’t willing to give Clinton the benefit of the doubt.

That’s largely because Clinton was viewed as dishonest and untrustworthy, exactly the sort of message that the Russian campaign (which used hashtags such as #Hillary4Prison) was trying to cultivate. Trump, of course, was trying to cultivate this message too. Media coverage often struck the same themes. And voters sometimes heard variations on this theme from Sanders and his supporters in the more contentious moments of the Democratic primaries. Was some of this Clinton’s fault? Yep, of course. Would Clinton still have been “Crooked Hillary” even without the Russians? Almost certainly. But the Russians were at least adding fuel to the right fire — the one that wound up consuming Clinton’s campaign.

The indictment also alleges that the Russian conspirators sought to suppress African-American turnout. A decline in black turnout was an important — perhaps even decisive — factor in Clinton’s defeat, although it may have been inevitable given that Barack Obama, the first African-American president, had been on the ballot in 2012.

Overall, then, my view on the effects of Russian interference is fairly agnostic. I tend to focus more on factors — such as Clinton’s email scandal or the Comey letter (and the media’s handling of those stories) — that had easier-to-prove effects. The hacked emails from the Clinton campaign and the DNC (which may or may not have had anything to do with the Russians) potentially also were more influential than the Russian efforts detailed in Friday’s indictments. Clinton’s Electoral College strategy didn’t have as much of an effect as some people assume — but it was pretty stupid all the same and is certainly worth mentioning.

But if it’s hard to prove anything about Russian interference, it’s equally hard to disprove anything: The interference campaign could easily have had chronic, insidious effects that could be mistaken for background noise but which in the aggregate were enough to swing the election by 0.8 percentage points toward Trump — not a high hurdle to clear because 0.8 points isn’t much at all.

Perhaps there are more clever methodologies that one could undertake. For instance, if we knew which states the efforts were concentrated in, we might be able to make a few additional inferences. Maybe some of that information will come to light as the result of Mueller’s probe and further investigative reporting. For the time being, however, we’re still somewhat in the dark.

Emergency Politics Podcast: Lots More Indictments In Mueller’s Russia Investigation

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

In an emergency edition of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the team responds to news that a grand jury has indicted 13 Russian individuals and three companies as part of special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election. The indictments detail an extensive effort to sow chaos in U.S. politics, including during the 2016 presidential election.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

February 15, 2018

Can The NBA All-Star Game Be Fixed?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Welcome to The Lab, FiveThirtyEight’s basketball podcast. On this week’s show (Feb. 15, 2018), FiveThirtyEight editor-in-chief Nate Silver is back to help break down the latest in the NBA with Neil and Kyle. First, the Utah Jazz are on an 11-game winning streak. The crew takes a look at what’s going right for the Jazz — and how it might come to a halt. Next, the All-Star Game is nearly here, and The Lab’s members are taking it to the lab: keeping what they like, cutting what they don’t and throwing out some crazy ideas (8-year-olds choosing teams! one-on-ones!) that might make watching it more enjoyable. Plus, a small-sample-size segment on the new Cleveland Cavaliers.

Here are links to what was discussed this week:

Keep an eye on our 2017-18 NBA predictions, updated after every game.

ESPN’s Zach Lowe wrote about what’s real and what’s not for the Utah Jazz.

To get in on the All-Star Game fun, you can draft your own team.

ESPN’s Dave McMenamin goes inside the new Cavaliers team.

February 12, 2018

Politics Podcast: What’s So Wrong With Nancy Pelosi?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Nancy Pelosi has been a key figure in Republican attack ads for years, and this year is no different. The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team debates why she is the focus of so much negative attention from the right (and often the left, too). The crew also breaks down the findings in a new study claiming that the “use of election forecasts in campaign coverage can confuse voters and may lower turnout.”

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

February 7, 2018

Who Should Be More Freaked Out About The Economy — Trump Or The Democrats?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): With the Dow nosedive on Monday, here’s our topic for today:

Should President Trump be freaking out about the stock market, and/or should Democrats be freaking out about the economy?

Let’s take those in order!

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): Trump should be a little worried about how he’s framed the stock market vis a vis his presidency.

On the Democratic side of things … I have no idea, to be honest! In some ways, I could see it helping them politically.

micah: Let’s focus on the Trump part first.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): But I think both sides should be freaking out, in the sense that the economy is likely to be more important to the midterms than a lot of stuff people freak out about.

julia_azari (Julia Azari, political science professor at Marquette University and FiveThirtyEight contributor): It’s lucky for Trump that it’s happening now and not in like October 2020.

clare.malone: But wait, don’t financial reporters keep telling me that the fundamentals of the economy are still relatively strong?

micah: Yeah, I don’t think both sides should be freaking out. That can’t be right.

natesilver: Wait, what do you mean? The economy could have a large impact on 2018 (and a larger one on 2020) and there’s a pretty clear upside and downside case for both parties.

So it may not be a bad thing if we had more news cycles devoted to the economy and fewer to the fuckin’ Nunes memo. For instance.

micah: Can we back up a moment? Can someone give a super brief primer on how the economy affects voters?

In general, good economic news helps Trump/Republicans and hurts Democrats because Trump/Republicans are the incumbent party (they control the White House and Congress), right?

natesilver: OMG

“Slack Chats for Dummies”

Of course good economic news helps the incumbent party.

clare.malone: OK, but can we differentiate for the dummies whether we think this stock market thing will be bad for Trump in the long run? Because, as previously stated, people keep telling me not to worry too much about a crash of the market as long as other economic factors are stable.

And I am one of those dummies, to be clear.

julia_azari: So, election models based on fundamentals like the economy tend to focus on employment, real income or GDP.

There is also a school of thought that suggests that people’s perceptions of how the economy is doing — not their own personal income/economic situations — matter for how likely they are to punish the incumbent party at the ballot box.

A flood of bad economic news, even if combined with a sweet $1.50 raise each week, could change those perceptions.

natesilver: I have Very Strong Feelings about fundamentals models in this context.

Specifically that I think trying to specify exactly which economic variables move public perceptions is a fool’s errand. And that most of the attempts to do so reflect overfitting and p-hacking.

julia_azari: But, like, conceptually, can’t we sorta posit that the stock market is different from, say, unemployment?

natesilver: Historically the unemployment rate has one of the weakest relationships with presidential popularity.

In part, that’s because people look at trends rather than levels. So if the unemployment rate goes from 4 percent to 5 percent, that might actually be worse for the president’s party than if it goes from 8 percent to 7 percent.

Anyway, in my view, the “correct” view of the relationship between the economy and elections is as follows:

The economy matters more than a lot of things, but is not deterministic;

A better economy helps the incumbent party, other things held equal;

There’s no one economic magic bullet — you have to look at a broad series of economic indicators across various segments of the economy;

Both perception and reality matter and it’s not always clear which is more important;

Trends matter more than levels;

People have a relatively short time horizon for evaluating economic performance.

julia_azari: I’m disappointed to admit that I mostly agree with all of that. Can I talk about Trump?

micah: Yeah, so let’s grant all that. Isn’t the correct view, based on all that, to dismiss the Dow plummet as something Trump shouldn’t worry about?

We know the stock market does not equal the economy. Especially the Dow!

natesilver: No, not at all. It could affect perceptions a lot. It’s a trend rather than a level. And it’s very salient and news-y.

micah: It’s a one-day drop, Nate!

natesilver: Wait, you’re strawmanning me again, Micah.

You just switched me from “The stock market could matter” to “Yesterday’s one-day drop does matter.”

micah: “It’s a trend,” said Nate Silver.

natesilver: A prolonged period of volatility — with mostly downward-shifting numbers — could matter a lot.

If this week is a one-off, much less so.

micah: Ah, OK.

julia_azari: The Dow is not only news-y but measurable in dramatic-sounding numbers. (I still have very vivid memories of the Dow reaching some benchmark in the 1990s. I was in high school and knew even less than I know now about stocks, but I remember it being a huge news story.)

Also, I think a downturn splits the Trump coalition — or at least has the potential to.

Trump has a very delicate political coalition of the people who liked him in the primary, and those who didn’t but voted for him in the general anyway. It’s not clear that his primary supporters were necessarily poorer than people who preferred other candidates (per some work Nate did at the time). So what made reluctant Trump voters vote for him in the general election in 2016? Some of Clare’s work shows that the economy is a priority for this group. If we’re looking at stories about why Trump was able to consolidate (more or less) the Republican coalition, you have a combo of the cultural folks and the outcome-oriented/economy-focused folks. The latter group came to Trump reluctantly, but perhaps liked that he was a businessman, and saw him (or any Republican) as good for the economy. I see this as a vulnerability in his coalition. The cultural Trumpists, on the other hand, are pretty happy.

natesilver: I agree with that. I think Trump’s sales pitch on being a competent manager of the economy is pretty important to a fairly wide group of voters. And it’s also fairly important that the economy has, in fact, done fairly well.

clare.malone: That is interesting. Those reluctant Trump voters, as we started calling them, might see a trend form over a couple of months — if this is the start of something — and that could help them form opinions that could, say, affect the midterms.

natesilver: One thing to note is that consumer confidence is quite high. Not only high in an absolute sense, but also high relative to merely good-ish numbers in other sectors.

People feel fairly bullish, and it seems like Trump is a part of that.

julia_azari: So I heard one of Trump’s campaign advisers speak in January, and he basically started out with the stock market as a key justification for the administration’s first year

micah: Yeah, I think our reluctant Trump voters would be the most vulnerable part of his coalition if the economy went south in any real way.

clare.malone: By the way, I feel it’s pertinent to point out that if you go to, say, the Fox News website, not much stock market coverage.

micah: Agreed, Clare.

I don’t think the economy washes away partisanship in any wholesale way. At the margins, maybe.

natesilver: But if you watch Fox News, there’s a stock market ticker, right? (There’s one on the website too.)

clare.malone: Sure, and there’s still some coverage of it:

Stuart Varney: “The sky is not falling…There is no economic catastrophe on the horizon.” pic.twitter.com/8we7ZIsDCm

— Fox News (@FoxNews) February 6, 2018

But I do think a lot of their stuff is still about the Nunes memo.

micah: The reluctant Trump voter logic I think is like this (remember, these are people who voted for Trump but simultaneously said they had an unfavorable view of him): “I’m very uncomfortable with Trump’s behavior, but he’ll be good for business/the economy and I didn’t want to vote for Hillary Clinton.”

That logic has mostly worked for Year 1.

The behavior is still super problematic, but the trade-off worked for them.

julia_azari: (Also Neil Gorsuch.)

micah: Right.

If the economy part falls out of it … he’s in trouble.

natesilver: I have another theory too. Do you want to hear it?

clare.malone: No.

micah: lol

clare.malone: Kidding. Nate, spout.

natesilver: I’ll warn you in advance that it’s completely unprovable.

clare.malone: LOVE THOSE

natesilver: Or not unprovable, but unproven.

julia_azari: Perfect!

natesilver: My hunch is that one reason why Trump’s approval has risen lately is that people are responding to a “sky is falling” mentality from the media and Democrats.

Reluctant Trumpers are responding to it, that is.

Democrats can huff and puff, but as long as nothing breaks, nothing blows up and no one gets fired, it might seem like a lot of hot air.

micah: Oh, I don’t buy that at all.

clare.malone: Well, it’s interesting

micah: I don’t think voters, including reluctant Trump voters, have opinions about media approaches that are strong enough to affect their political outlook.

clare.malone: I had a friend, who is a Democrat, recently bring up the Department of Labor’s decision to remove data that adversely affected the administration’s position from a proposal to change tip-pooling rules. And he said the Democrats should be messaging hard about all these economic rule changes and how they could adversely affect the working (wo)man, as it were.

Not just about the Trump stuff.

natesilver: But Trump often makes the argument that, e.g., the media never brings up good news. Or that the Russia stuff is a bunch of baloney.

And the question is — what tangible evidence do voters who are not partisan Democrats have to prove him wrong?

julia_azari: Maybe there is a sort of closing of ranks among people who we might consider reluctant Trumpers. They liked Marco Rubio (or whoever) better in the primary, but they feel like the culture has shifted in this really uncomfortable way into a lot of anti-Trump virtue signaling in media and among corporate entities.

And this leads them to rally around Trump/Republicans in a way they might not otherwise do. This is compatible with what Nate just said, right?

micah: It is, yeah.

But I’m skeptical.

I do think Clare’s Democratic friend is right, though.

clare.malone: He said something along the lines of, “If it doesn’t catch fire right away, the Democrats don’t pursue it.”

I do think people tire of the virtue signaling. Democrats too, I’d think, in some ways — i.e., Democrats who aren’t the hardcore, Indivisible volunteers types.

julia_azari: Yeah. So there’s some interesting work in political science that backs this up a bit. I was just at a conference with Lilliana Mason of the University of Maryland, and her research illustrates how much people are motivated by protecting their group status and identity.

micah: Yeah. And there’s truth to the idea that Democrats are shit at building an argument.

natesilver: That’s overrated.

micah: I didn’t even rate it! I just think it’s true — the extent to which it matters is another question.

natesilver: I mean, there are times when it’s right. Like, Democrats’ messaging was kind of shit during the shutdown, even though they started out with more people blaming Republicans by default.

Somebody wrote — I forget who, but I was very jealous of the post — that it’s actually an advantage not to have a clear message at the midterm because it’s one less thing you can be attacked on.

clare.malone: Yeah, but … it’s not like breaking news that Democrats try to fashion themselves as the party of the working (wo)man, historically.

I find that a little facile.

julia_azari: “Democrats suck at messaging” is one of the journalistic tropes that needs to be interrogated.

natesilver: A healthy economy is very important to Trump’s message, though.

micah: OK, let me ask this: Assuming the economy keeps chugging along (and I think that’s probably the safest assumption at this point?), to what extent does that tamp down Democratic gains?

Or, does the economy matter to voters less than normal because Trump is so atypical in other ways?

natesilver: It gives Trump and Republicans an argument.

A credible argument. Something to hang their hat on.

julia_azari: Well, his approval rating is lower than the economy would predict.

And there’s been a ton of Republican retirements despite the good economy.

clare.malone: If we think midterms are about getting an anti-Trump turnout from the Democratic base — because they’re eager to win back Congress so they can impeach him — I think it matters less.

natesilver: That cuts both ways. On the one hand, voters obviously have a lot of information to weigh and there are fewer swing voters than there used to be. On the other hand, a healthy economy is pretty important for a sense of normalcy, and Republicans don’t have a lot of other good arguments to make.

micah: How many voters would agree with this article from The Atlantic, which argued that “the best hope of defending the country from Trump’s Republican enablers, and of saving the Republican Party from itself, is to … vote mindlessly and mechanically against Republicans at every opportunity, until the party either rights itself or implodes (very preferably the former)”?

julia_azari: The two who wrote it.

clare.malone: lol

micah: Like, what if it’s November 2018 and GDP growth is 6 percent and special counsel Robert Mueller has come back with an obstruction of justice finding and some type of not-clear-cut collusion case?

(Six percent is obviously ridiculous, but you see what I’m getting at.)

natesilver: Then Trump and Republicans have a pretty good argument to make.

julia_azari: To think of it a different way, Republicans suffered big midterm losses in 1982 (after a serious economic downturn) and in 2006 (with an unpopular war). Is anything that’s going on now that bad? We don’t know, but opposition to Trump has been pretty clear and well-organized. And, unlike Trump, neither Ronald Reagan in 1980 nor George W. Bush in 2004 lost the popular vote.

micah: I guess what I’m trying to figure out is … does a good economy preclude a Democratic wave or just make it more unlikely?

julia_azari: Less likely, but still possible.

natesilver: If you want to get fairly technical, I think the risks might be slightly asymmetric. A better economy somewhat helps Trump, but a bad economy could really hurt him. That’s sort of been true for most presidents, by the way — it isn’t anything unique to Trump. Sometimes other factors can overcome a good economy and make a president unpopular. But it’s very hard for a president to be popular amidst a bad economy, unless he’s inherited it and isn’t seen as responsible.

But the thing is … it’s not that easy for Democrats to flip the House and the Senate, given the Senate map and the way districts are drawn. So having a little bit of a wind at his back, in the form of the economy, might be enough for Trump.

julia_azari: If Democrats are fired up and Republicans aren’t, that might have wave implications. To put it another way, were the two successive waves during Obama’s presidency about the economy? Or about strong responses to Obama, with his voters being less motivated to come out and defend Democratic candidates?

micah: Both?

OK, we gotta wrap. Final thoughts?

clare.malone: I still need to read more about the state of our economic fundamentals, but I think that we all need to be keeping an eye on the business section over the next few months.

julia_azari: It’s February. At this time two years ago, we were still trying to figure out which establishment Republican would pull ahead in the primaries. A lot can change.

natesilver: My final thought is that my lunch order is late and my stomach needs a stimulus.

Should Trump Or The Democrats Be More Worried About The Economy?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): With the Dow nosedive on Monday, here’s our topic for today:

Should President Trump be freaking out about the stock market, and/or should Democrats be freaking out about the economy?

Let’s take those in order!

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): Trump should be a little worried about how he’s framed the stock market vis a vis his presidency.

On the Democratic side of things … I have no idea, to be honest! In some ways, I could see it helping them politically.

micah: Let’s focus on the Trump part first.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): But I think both sides should be freaking out, in the sense that the economy is likely to be more important to the midterms than a lot of stuff people freak out about.

julia_azari (Julia Azari, political science professor at Marquette University and FiveThirtyEight contributor): It’s lucky for Trump that it’s happening now and not in like October 2020.

clare.malone: But wait, don’t financial reporters keep telling me that the fundamentals of the economy are still relatively strong?

micah: Yeah, I don’t think both sides should be freaking out. That can’t be right.

natesilver: Wait, what do you mean? The economy could have a large impact on 2018 (and a larger one on 2020) and there’s a pretty clear upside and downside case for both parties.

So it may not be a bad thing if we had more news cycles devoted to the economy and fewer to the fuckin’ Nunes memo. For instance.

micah: Can we back up a moment? Can someone give a super brief primer on how the economy affects voters?

In general, good economic news helps Trump/Republicans and hurts Democrats because Trump/Republicans are the incumbent party (they control the White House and Congress), right?

natesilver: OMG

“Slack Chats for Dummies”

Of course good economic news helps the incumbent party.

clare.malone: OK, but can we differentiate for the dummies whether we think this stock market thing will be bad for Trump in the long run? Because, as previously stated, people keep telling me not to worry too much about a crash of the market as long as other economic factors are stable.

And I am one of those dummies, to be clear.

julia_azari: So, election models based on fundamentals like the economy tend to focus on employment, real income or GDP.

There is also a school of thought that suggests that people’s perceptions of how the economy is doing — not their own personal income/economic situations — matter for how likely they are to punish the incumbent party at the ballot box.

A flood of bad economic news, even if combined with a sweet $1.50 raise each week, could change those perceptions.

natesilver: I have Very Strong Feelings about fundamentals models in this context.

Specifically that I think trying to specify exactly which economic variables move public perceptions is a fool’s errand. And that most of the attempts to do so reflect overfitting and p-hacking.

julia_azari: But, like, conceptually, can’t we sorta posit that the stock market is different from, say, unemployment?

natesilver: Historically the unemployment rate has one of the weakest relationships with presidential popularity.

In part, that’s because people look at trends rather than levels. So if the unemployment rate goes from 4 percent to 5 percent, that might actually be worse for the president’s party than if it goes from 8 percent to 7 percent.

Anyway, in my view, the “correct” view of the relationship between the economy and elections is as follows:

The economy matters more than a lot of things, but is not deterministic;

A better economy helps the incumbent party, other things held equal;

There’s no one economic magic bullet — you have to look at a broad series of economic indicators across various segments of the economy;

Both perception and reality matter and it’s not always clear which is more important;

Trends matter more than levels;

People have a relatively short time horizon for evaluating economic performance.

julia_azari: I’m disappointed to admit that I mostly agree with all of that. Can I talk about Trump?

micah: Yeah, so let’s grant all that. Isn’t the correct view, based on all that, to dismiss the Dow plummet as something Trump shouldn’t worry about?

We know the stock market does not equal the economy. Especially the Dow!

natesilver: No, not at all. It could affect perceptions a lot. It’s a trend rather than a level. And it’s very salient and news-y.

micah: It’s a one-day drop, Nate!

natesilver: Wait, you’re strawmanning me again, Micah.

You just switched me from “The stock market could matter” to “Yesterday’s one-day drop does matter.”

micah: “It’s a trend,” said Nate Silver.

natesilver: A prolonged period of volatility — with mostly downward-shifting numbers — could matter a lot.

If this week is a one-off, much less so.

micah: Ah, OK.

julia_azari: The Dow is not only news-y but measurable in dramatic-sounding numbers. (I still have very vivid memories of the Dow reaching some benchmark in the 1990s. I was in high school and knew even less than I know now about stocks, but I remember it being a huge news story.)

Also, I think a downturn splits the Trump coalition — or at least has the potential to.

Trump has a very delicate political coalition of the people who liked him in the primary, and those who didn’t but voted for him in the general anyway. It’s not clear that his primary supporters were necessarily poorer than people who preferred other candidates (per some work Nate did at the time). So what made reluctant Trump voters vote for him in the general election in 2016? Some of Clare’s work shows that the economy is a priority for this group. If we’re looking at stories about why Trump was able to consolidate (more or less) the Republican coalition, you have a combo of the cultural folks and the outcome-oriented/economy-focused folks. The latter group came to Trump reluctantly, but perhaps liked that he was a businessman, and saw him (or any Republican) as good for the economy. I see this as a vulnerability in his coalition. The cultural Trumpists, on the other hand, are pretty happy.

natesilver: I agree with that. I think Trump’s sales pitch on being a competent manager of the economy is pretty important to a fairly wide group of voters. And it’s also fairly important that the economy has, in fact, done fairly well.

clare.malone: That is interesting. Those reluctant Trump voters, as we started calling them, might see a trend form over a couple of months — if this is the start of something — and that could help them form opinions that could, say, affect the midterms.

natesilver: One thing to note is that consumer confidence is quite high. Not only high in an absolute sense, but also high relative to merely good-ish numbers in other sectors.

People feel fairly bullish, and it seems like Trump is a part of that.

julia_azari: So I heard one of Trump’s campaign advisers speak in January, and he basically started out with the stock market as a key justification for the administration’s first year

micah: Yeah, I think our reluctant Trump voters would be the most vulnerable part of his coalition if the economy went south in any real way.

clare.malone: By the way, I feel it’s pertinent to point out that if you go to, say, the Fox News website, not much stock market coverage.

micah: See, I think that’s an important point, Clare.

The economy washes away partisanship in any wholesale way. At the margins, I guess.

natesilver: But if you watch Fox News, there’s a stock market ticker, right? (There’s one on the website too.)

clare.malone: Sure, and there’s still some coverage of it:

Stuart Varney: “The sky is not falling…There is no economic catastrophe on the horizon.” pic.twitter.com/8we7ZIsDCm

— Fox News (@FoxNews) February 6, 2018

But I do think a lot of their stuff is still about the Nunes memo.

micah: The reluctant Trump voter logic I think is like this (remember, these are people who voted for Trump but simultaneously said they had an unfavorable view of him): “I’m very uncomfortable with Trump’s behavior, but he’ll be good for business/the economy and I didn’t want to vote for Hillary Clinton.”

That logic has mostly worked for Year 1.

The behavior is still super problematic, but the trade-off worked for them.

julia_azari: (Also Neil Gorsuch.)

micah: Right.

If the economy part falls out of it … he’s in trouble.

natesilver: I have another theory too. Do you want to hear it?

clare.malone: No.

micah: lol

clare.malone: Kidding. Nate, spout.

natesilver: I’ll warn you in advance that it’s completely unprovable.

clare.malone: LOVE THOSE

natesilver: Or not unprovable, but unproven.

julia_azari: Perfect!

natesilver: My hunch is that one reason why Trump’s approval has risen lately is that people are responding to a “sky is falling” mentality from the media and Democrats.

Reluctant Trumpers are responding to it, that is.

Democrats can huff and puff, but as long as nothing breaks, nothing blows up and no one gets fired, it might seem like a lot of hot air.

micah: Oh, I don’t buy that at all.

clare.malone: Well, it’s interesting

micah: I don’t think voters, including reluctant Trump voters, have opinions about media approaches that are strong enough to affect their political outlook.

clare.malone: I had a friend, who is a Democrat, recently bring up the Department of Labor’s decision to remove data that adversely affected the administration’s position from a proposal to change tip-pooling rules. And he said the Democrats should be messaging hard about all these economic rule changes and how they could adversely affect the working (wo)man, as it were.

Not just about the Trump stuff.

natesilver: But Trump often makes the argument that, e.g., the media never brings up good news. Or that the Russia stuff is a bunch of baloney.

And the question is — what tangible evidence do voters who are not partisan Democrats have to prove him wrong?

julia_azari: Maybe there is a sort of closing of ranks among people who we might consider reluctant Trumpers. They liked Marco Rubio (or whoever) better in the primary, but they feel like the culture has shifted in this really uncomfortable way into a lot of anti-Trump virtue signaling in media and among corporate entities.

And this leads them to rally around Trump/Republicans in a way they might not otherwise do. This is compatible with what Nate just said, right?

micah: It is, yeah.

But I’m skeptical.

I do think Clare’s Democratic friend is right, though.

clare.malone: He said something along the lines of, “If it doesn’t catch fire right away, the Democrats don’t pursue it.”

I do think people tire of the virtue signaling. Democrats too, I’d think, in some ways — i.e., Democrats who aren’t the hardcore, Indivisible volunteers types.

julia_azari: Yeah. So there’s some interesting work in political science that backs this up a bit. I was just at a conference with Lilliana Mason of the University of Maryland, and her research illustrates how much people are motivated by protecting their group status and identity.

micah: Yeah. And there’s truth to the idea that Democrats are shit at building an argument.

natesilver: That’s overrated.

micah: I didn’t even rate it! I just think it’s true — the extent to which it matters is another question.

natesilver: I mean, there are times when it’s right. Like, Democrats’ messaging was kind of shit during the shutdown, even though they started out with more people blaming Republicans by default.

Somebody wrote — I forget who, but I was very jealous of the post — that it’s actually an advantage not to have a clear message at the midterm because it’s one less thing you can be attacked on.

clare.malone: Yeah, but … it’s not like breaking news that Democrats try to fashion themselves as the party of the working (wo)man, historically.

I find that a little facile.

julia_azari: “Democrats suck at messaging” is one of the journalistic tropes that needs to be interrogated.

natesilver: A healthy economy is very important to Trump’s message, though.

micah: OK, let me ask this: Assuming the economy keeps chugging along (and I think that’s probably the safest assumption at this point?), to what extent does that tamp down Democratic gains?

Or, does the economy matter to voters less than normal because Trump is so atypical in other ways?

natesilver: It gives Trump and Republicans an argument.

A credible argument. Something to hang their hat on.

julia_azari: Well, his approval rating is lower than the economy would predict.

And there’s been a ton of Republican retirements despite the good economy.

clare.malone: Well, if we think midterms are about getting an anti-Trump turnout from the Democratic base — because they’re eager to win back Congress so they can impeach him — I think it matters less.

natesilver: I think that cuts both ways. On the one hand, voters obviously have a lot of information to weigh and there are fewer swing voters than there used to be. On the other hand, a healthy economy is pretty important for a sense of normalcy, and Republicans don’t have a lot of other good arguments to make.

micah: How many voters would agree with this article from The Atlantic, which argued that “the best hope of defending the country from Trump’s Republican enablers, and of saving the Republican Party from itself, is to … vote mindlessly and mechanically against Republicans at every opportunity, until the party either rights itself or implodes (very preferably the former)”?

julia_azari: The two who wrote it.

clare.malone: lol

micah: Like, what if it’s November 2018 and GDP growth is 6 percent and special counsel Robert Mueller has come back with an obstruction of justice finding and some type of not-clear-cut collusion case?

(Six percent is obviously ridiculous, but you see what I’m getting at.)

natesilver: Then Trump and Republicans have a pretty good argument to make.

julia_azari: To think of it a different way, Republicans suffered big midterm losses in 1982 (after a serious economic downturn) and in 2006 (with an unpopular war). Is anything that’s going on now that bad? We don’t know, but opposition to Trump has been pretty clear and well-organized. And neither Ronald Reagan in 1980 nor George W. Bush in 2004 lost the popular vote.

micah: I guess what I’m trying to figure out is … does a good economy preclude a Democratic wave or just make it more unlikely?

julia_azari: Less likely, but still possible.

natesilver: If you want to get fairly technical, I think the risks might be slightly asymmetric. A better economy somewhat helps Trump, but a bad economy could really hurt him. That’s sort of been true for most presidents, by the way — it isn’t anything unique to Trump. Sometimes other factors can overcome a good economy and make a president unpopular. But it’s very hard for a president to be popular amidst a bad economy, unless he’s inherited it and isn’t seen as responsible.

But the thing is … it’s not that easy for Democrats to flip the House and the Senate, given the Senate map and the way districts are drawn. So having a little bit of a wind at his back, in the form of the economy, might be enough for Trump.

julia_azari: If Democrats are fired up and Republicans aren’t, that might have wave implications. To put it another way, were the two successive waves during Obama’s presidency about the economy? Or about strong responses to Obama, with his voters being less motivated to come out and defend Democratic candidates?

micah: Both?

OK, we gotta wrap. Final thoughts?

clare.malone: I still need to read more about the state of our economic fundamentals, but I think that we all need to be keeping an eye on the business section over the next few months.

julia_azari: It’s February. At this time two years ago, we were still trying to figure out which establishment Republican would pull ahead in the primaries. A lot can change.

natesilver: My final thought is that my lunch order is late and my stomach needs a stimulus.

February 6, 2018

Screw It — Let’s Debate Some Hypothetical LeBron Trades

The NBA trade deadline is Thursday afternoon, so we assembled FiveThirtyEight’s resident basketball writers — plus editor-in-chief/trade machine troll Nate Silver — to bandy about some, um, creative trade ideas for LeBron James and the Cleveland Cavaliers. Sure, James says he won’t waive his no-trade clause. (He says a lot of things.) But if LeBron somehow does assent to a deal, should the Cavs think about trading him? The transcript below has been lightly edited.

neil (Neil Paine, senior sportswriter): We are all gathered here because FiveThirtyEight editor-in-chief Nate Silver had a very hot NBA trade deadline take that he needed to get out into the world. Nate, what is your idea?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): I think the Cavaliers should trade LeBron James.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 730 followers