Nate Silver's Blog, page 12

September 9, 2022

Why A State Like Michigan Might Actually Be A Blue State

By Nate Silver

Sep. 9, 2022, at 9:00 AM

ILLUSTRATION BY EMILY SCHERER

Is Michigan a red state or a blue state?

“It’s a purple state,” you might say! But sorry, I’m not going to let you off so easily. You have to pick the red pill or the blue pill.

As a Michigan native, I’d say Michigan is a blue state. Not that this assessment requires any particular local knowledge. It has voted Democratic for president all but once since 1992 (it voted for former President Donald Trump in 2016). Its governorship has bounced back and forth more, but its current governor, Gretchen Whitmer, is a Democrat and a clear favorite for reelection, according to the FiveThirtyEight 2022 midterm election forecast. Democrats have also controlled both of its U.S. Senate seats since the 2000 elections. The state legislature is Republican-controlled, but Democrats should be competitive this year after redistricting. So it’s a close call, but I’m going with Michigan as a “blue state.”

But according to FiveThirtyEight’s partisan lean index, Michigan is Republican-leaning. Specifically, it’s 1.2 percentage points more Republican than the country overall.1 It’s close, but Michigan’s partisan lean nods toward “red state.”

So, who’s right in this case? Me or the algorithm?

Well, I’m a wee bit biased here, but I think I’m right. Michigan is more a blue state than a red state, and the distinction reveals something important about the balance of power in politics today and the strategies of the major political parties.

FiveThirtyEight’s partisan lean index classifies Michigan as Republican-leaning because it has been less blue than the country as a whole in recent elections. Case in point: In 2020, now-President Joe Biden won Michigan by 2.8 points, less than his 4.5-point margin in the national popular vote.

Then again, the national popular vote might not be the best baseline. After all, it depends in part on states where Democrats win by huge margins, without getting any additional benefit in the Electoral College. For instance, Biden won California by more than 5 million votes. But suppose he’d won it by only 1 million votes. It would still be a comfortable margin, but in that case, Biden would have won the national popular vote by only 1.9 points, and Michigan would have been to the left of the country as a whole, without changing the Electoral College outcome at all.

This is somewhat complex, so let me state my hypothesis as clearly as possible — there are two of them, really:

Parties are trying to win control of the presidency and Congress. But since the popular vote doesn’t determine control of these, parties don’t actually care about the popular vote. Therefore, measures like FiveThirtyEight’s partisan lean index that are calibrated based on the popular vote may be flawed.Republicans currently have a structural advantage in many of America’s political institutions. However, it doesn’t necessarily follow that Republicans will win more than half the time.Let’s start with that second point. One important but easy-to-overlook facet of American elections is that each party wins about half the time. Over the past 40 years, for example, Democrats have controlled the presidency for 18 years (two years and counting for Biden, eight each for former Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton) while Republicans have had it for 22. Also in the past 40 years, Democrats have held the U.S. Senate for just short of 20 years,2 and Republicans for just slightly more than 20 years. The House? Democrats have been in charge for roughly 20 years and the GOP for 20.

It’s true that Republicans currently enjoy a structural advantage in the Electoral College and the U.S. Senate, such that they can expect to win both with less than half of the popular vote. (They also had an advantage in the U.S. House for most of the 2010s, although that has been reduced somewhat following redistricting.) But I don’t think it necessarily follows that Republicans can expect to win those offices more than half the time.

After all, Republicans haven’t done a great job of winning these offices recently. They lost the presidency in 2020. They don’t control the Senate — and they may not get it back this year. The FiveThirtyEight forecast now shows Democrats with a 70 percent chance of keeping control of the Senate.

That said, some votes are more valuable than others. In a presidential election, for instance, the marginal vote in Michigan matters a lot more than the marginal vote in California. And in the Senate, a voter in North Dakota has a lot more power than one in Texas, since Texas has the same number of senators despite having more than 37 times the inhabitants. This creates a significant bias in the Senate toward white, rural voters, who are overrepresented in low-population states, and moreover, Republicans in the Trump era have adopted a particularly potent strategy of catering to those voters.

Watch: https://abcnews.go.com/fivethirtyeigh...

Put another way, the upshot of the structural bias toward Republicans may not be that they can attain some permanent supermajority, but rather that they are able to win elections half the time despite advancing policies that are significantly to the right of the median voter, especially on issues like abortion, gun control and environmental regulation. It’s likely not a coincidence either that these issues have strong urban-rural divides, which speak to the GOP’s current advantage in the Senate.

And yet it’s not as though Republicans are in some untenable position. Their structural advantages give them a much bigger margin for error, and so they still have decent chances in the Senate despite nominating a poor slate of candidates. They’re also favored to win the House according to the FiveThirtyEight forecast. And they have plenty of hope of winning the presidency back in 2024.

It may seem strange to talk about the parties in such an abstract manner, as though they’re rational actors pursuing some game-theory-derived Nash equilibrium. Indeed, this description leaves a lot to be desired. The Republican Party and the Democratic Party are not simple entities. Although there are formal party structures such as the Republican National Committee, in practice, much of a party’s power rests with current, former and aspiring elected officials, along with donors, other public figures who are influential within the party and, of course, the voters. These groups’ objectives don’t always align, and sometimes that can result in outcomes such as nominating subpar candidates to key Senate races or having a former president interfere in a midterm in unhelpful ways.

But if neither party is particularly happy with its situation — well, that’s sometimes what an equilibrium looks like, in the same sense that both sides often walk away feeling a little unhappy after a tough negotiation.

Still, this has considerations for our partisan lean index. The implication we frequently take from it — in fact, this is an assumption built into our various forecast models — is over the long run, such as if you play out the next 40 years given current party coalitions, the popular vote for Congress and the presidency will be tied in an average year.

I don’t think that’s the correct implication, though. My assertion here, instead, is that each party will continue to win elections about half the time even though Democrats are likely to continue to win the popular vote more than half the time.

Since 2016, for instance, Democrats have won the popular vote for the presidency by 2.1 points (Hillary Clinton) and 4.5 points (Biden). They also won the popular vote for the U.S. House by 3.1 points in 2020 and 8.6 points in 2018, but lost it by 1.1 point in 2016. This is a crude method, but if you average those five figures, you wind up with Democrats winning the popular vote by 3.4 points on average.

Here’s what our partisan lean index would look like in a year where Democrats win the national popular vote by 3.4 points. Note that a state like Michigan — along with Nevada and Pennsylvania — now rates as slightly blue rather than slightly red. Wisconsin, Georgia, North Carolina, Arizona and Florida are still red-leaning, however.

The FiveThirtyEight partisan lean index, recalibratedHow each state votes in an election where Democrats win the popular vote by 3.4 percentage points

State Partisan Lean State Partisan Lean Massachusetts D+36.0 Arizona R+4.2 Hawaii D+35.0 Florida R+4.2 Vermont D+30.9 Iowa R+6.3 Maryland D+29.3 Texas R+8.6 California D+28.9 Ohio R+9.0 Rhode Island D+27.4 Alaska R+11.2 New York D+23.4 South Carolina R+15.2 Delaware D+17.1 Indiana R+16.6 Illinois D+16.8 Montana R+16.6 Washington D+15.8 Mississippi R+16.9 Connecticut D+15.5 Louisiana R+17.1 New Jersey D+15.4 Kansas R+17.3 Oregon D+14.0 Missouri R+17.8 New Mexico D+10.4 Nebraska R+21.4 Colorado D+9.8 Utah R+22.9 Virginia D+8.0 Kentucky R+23.7 Maine D+7.4 Tennessee R+26.0 Minnesota D+5.3 Alabama R+26.2 New Hampshire D+3.7 Arkansas R+28.4 Michigan D+1.8 South Dakota R+28.8 Nevada D+0.9 West Virginia R+32.1 Pennsylvania D+0.5 Idaho R+33.6 Wisconsin R+0.7 Oklahoma R+33.8 North Carolina R+1.4 North Dakota R+33.8 Georgia R+4.0 Wyoming R+46.3Partisan lean is the average margin difference between how a state or district votes and how the country votes overall. This version of partisan lean, meant to be used for congressional and gubernatorial elections, is calculated as 50 percent the state or district’s lean relative to the nation in the most recent presidential election, 25 percent its relative lean in the second-most-recent presidential election and 25 percent a custom state-legislative lean.

Sources: State election websites, Daily Kos Elections

That all seems fairly intuitive relative to how recent elections have gone — more so than the implication that Michigan is a red state. To be clear, this is not an official change to our partisan lean index; it’s just me playing out the logical implications of an idea.

It’s also not a prediction for what will happen this year, but still, these figures may be more in line with how future elections will play out — both in theory and in practice.

September 7, 2022

September 6, 2022

Do You Buy That … Dems Are Favored To Win Pennsylvania Senate And Governor’s Races?

FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver breaks down Democrats’ chances of winning midterm races in Pennsylvania on ABC’s “This Week.”

September 2, 2022

Why Trump’s Presence In The Midterms Is Risky For The GOP

By Nate Silver

Sep. 2, 2022, at 8:42 AM

ILLUSTRATION BY EMILY SCHERER

Upset Democratic special election wins in Alaska and New York over the past two weeks are the latest sign that the political environment might be unusual for a midterm election. Frankly, the results since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade have looked more like 2018 than 2020, with Democrats competitive even in red-leaning districts. That probably won’t hold.

But even if it’s just a neutral year — as the generic congressional ballot currently shows — Democrats would probably be pleased. It would likely be enough for them to hold the Senate, and even gain a seat or two. It would even give them a chance in the House.

Or maybe not. Democrats are fighting against a lot of midterm election history where the president’s party typically does poorly. They’ve also benefited from a turnout advantage in recent special elections that may not be replicated in November. The FiveThirtyEight forecast does not consider the special election results and hedges based on these historical trends; it’s why it still has Republicans as 75 percent favorites to keep the House, although Democrats’ chances of retaining the Senate continue to improve and are now 68 percent.1

Still, whenever a Democrat gets elected in Alaska — even given the quirks of the instant-runoff process in the state — it’s probably worth asking again if things could go really badly for the GOP.

Last month, I examined a series of what I called asterisk midterm elections. These were the midterms that were the exceptions to the rule: When the president’s party actually gained seats in the House, or at least fought things to a near-draw while gaining in the Senate. The elections were 1934, 1962, 1998 and 2002, and three of the four involved some type of national emergency (the Great Depression, the Cuban missile crisis and the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks). The 1998 midterm was the exception to this, but it did have a national controversy of its own — a backlash to Republican overreach on the Monica Lewinsky scandal and subsequent impeachment trial. I argued that 2022 has some features in common with these elections, but it had the most in common with 1998 given the partisan overreach that is happening now.

In particular, the involvement of former President Donald Trump makes 2022 different than almost any other midterm.

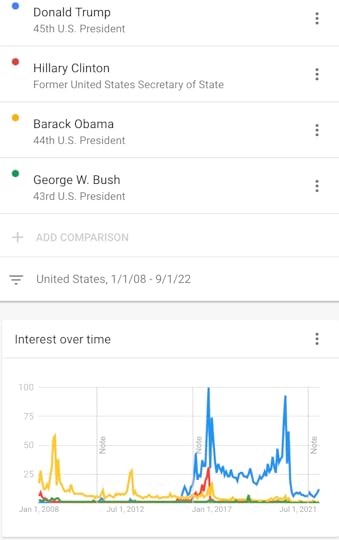

At this point, we’re used to Trump’s ubiquity in American political life. But this degree of involvement from a former president — or, for that matter, even an ex-presidential candidate — is highly unusual. Take a look, for example, at the amount of Google search traffic for Trump as compared with other former presidents.

Former Presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush kept a very low profile after completing their second terms. And the previous losing candidate before Trump, Hillary Clinton, famously retreated to the woods in Chappaqua, New York, after 2016. Their search traffic quickly dropped to near-zero once their campaigns or presidencies were over, and then stayed there.

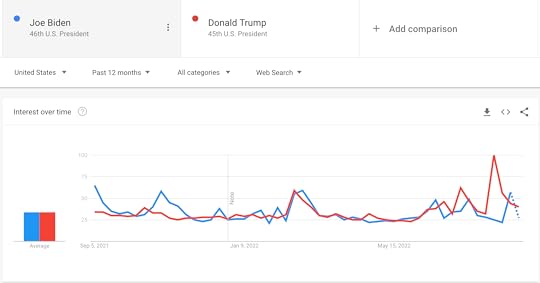

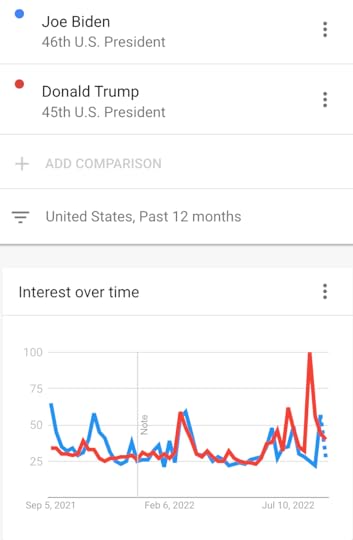

Trump’s search traffic, meanwhile, is much less than during his presidency, but it’s still fairly high. Over the past year, in fact, there’s been about as much search traffic for Trump as for the current president, Joe Biden!

And the amount of news interest in Trump has been increasing recently. Part of that is the string of endorsements he’s made in Republican primaries, but the bigger factor is the FBI’s seizure of classified documents he had in his possession at his Florida estate, Mar-a-Lago.

When that seizure occurred, a certain strain of conventional wisdom suggested that this could help Republicans in the midterms, such as by increasing the enthusiasm of GOP voters.2

If that’s true, it’s not showing up in the data. The past four special elections — two in New York, one in Alaska and one in Minnesota — all occurred after the seizure on Aug. 8, and they all showed excellent results for Democrats. And Democrats have actually gained about a point on the generic ballot since then, although it’s a small enough difference that it could be statistical noise.

It’s not exactly some genius insight to suggest that Trump could cause problems for Republicans in the midterms. At the very least, he’s directly put their prospects at risk by endorsing inexperienced candidates like Mehmet Oz in Pennsylvania and Blake Masters in Arizona, who are badly underperforming partisan benchmarks in their states.

But it’s also the case that Trump’s continued dominance over the GOP violates a potentially key assumption behind the “midterm curse,” which is that a party usually tries to pivot away from its losing candidates.

Sometimes that pivot involves providing voters a menu of new policy options, such as the GOP’s “Contract with America” in 1994. Many times it’s a pivot to the center, though it doesn’t need to be; the tea party movement in 2010 was more conservative in some ways than Bush, but it still offered voters something a little different.

The pivot doesn’t necessarily need to involve a new figurehead for the party, either. It probably helps if you don’t have one, in fact, since then you can frame the election as a referendum on the incumbent party’s performance and take advantage of thermostatic changes in public opinion rather than as a choice between imperfect alternatives, as presidential elections turn into.

In 2018, for instance, Trump gave Democrats a lot of ammunition to run on, and they nominated different kinds of candidates in different kinds of districts while preparing for a very large presidential primary field. What you didn’t see, though, was a lot of Clinton, who didn’t make her first campaign appearance until October.

Let’s play out that counterfactual, though. Imagine that, in 2018, Clinton had been very active on the campaign trail, endorsing candidates that often went against the wishes of the party establishment, repeatedly claiming that the 2016 election had been stolen — and then there had been a FBI seizure of classified secretary of state records in Chappaqua.

Would that have helped Democrats in the midterms? Probably not.

But if anything, Republicans are doubling down on Trump and Trumpism. This week, he demanded a redo of the 2020 election. The leading candidate for the 2024 nomination apart from Trump, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, defended Trump after the Mar-a-Lago search and has even come to mimic some of his mannerisms and manners of speech. Republicans have had problems with candidate quality in Senate and gubernatorial races before, but this year, inexperienced and/or very right-wing candidates — often ones endorsed by Trump — are the rule and not the exception.

All that said, I still think the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe — and maybe declining inflation — are the more important factors in Democrats’ recent surge. But Republicans are behaving in atypical ways for an opposition party in the midterms, and they may get an atypically poor outcome as a result.

September 1, 2022

Explore The Ways Republicans Or Democrats Could Win The Midterms

UPDATED Aug. 31, 2022, at 2:44 PM

Explore The Ways Republicans Or Democrats Could Win The MidtermsPick the winner of each race to see how FiveThirtyEight’s forecast would change.

2022 election forecast How our forecast works

By Ryan Best, Jay Boice, Aaron Bycoffe and Nate Silver

FiveThirtyEight’s Senate and House forecasts are based on myriad factors, with changes in one race often influencing odds in another. To see just how much individual races can change the forecast, first try picking different winners in key Senate races (or feel free to skip ahead to key races in the House!).1 But beware, the choices you make in the Senate affect the House, and vice versa.

iIncumbent candidate Scroll to see more racesDemocrats are slightly favored to win the Senate

Based on FiveThirtyEight’s current forecast

Republicans win33 in 100MAJORITY56REPSEATS5452525456DEMSEATSDemocrats win67 in 100Average: 50.656565454525250505050525254545656REPSEATSDEMSEATSMorelikelyMorelikelyRepublicans are favored to win the House

Based on FiveThirtyEight’s current forecast

Republicans win76 in 100MAJORITY270REPSEATS255240225225240255270DEMSEATSDemocrats win24 in 100Average: 228.7270270255255240240225225225225240240255255270270REPSEATSDEMSEATSMorelikelyMorelikelyWho will control Congress?

Based on FiveThirtyEight’s current forecast

Republicans win both chambers33 in 100Republicans win the Senate

Democrats win the House<1 in 100Democrats win the Senate

Republicans win the House43 in 100Democrats win both chambers23 in 100Odds displayed in the graphics may not match numeric odds due to rounding.

How this works: We start with the 40,000 simulations that our election forecast runs every time it updates. When you choose the winner of a race, we throw out any simulations where the outcome you picked didn’t happen and recalculate each party’s chances of winning each chamber using just the remaining simulations. If you choose enough unlikely outcomes, we’ll eventually wind up with so few simulations that we can’t produce accurate results. When that happens, we go back to our full set of simulations and run a series of regressions to see how your scenario might look if it turned up more often.

In simplified terms, the regressions start off by looking at the vote share for each candidate in every simulation and seeing how the rest of the map changed in response to big or small wins. Let’s say you picked Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock to win Georgia. In some of our simulations, Warnock may have won Georgia very narrowly, and in others, he may have lost it very narrowly. But in simulations where he won Georgia by a big margin, Democrats may have also won big in toss-up races and pulled some Democratic-leaning races into their column, while the reverse may be true in simulations where Warnock lost Georgia by a wide margin. We figure out how every other race tended to look in that full range of scenarios, tracking not just whether other Democratic candidates usually won other races but also how much they generally won or lost each one by.

After all of that, we take some representative examples of scenarios that include the picks you made and use what we learned from our regression analysis to adjust all 40,000 simulations, and then recalculate win probabilities for each race and chamber of Congress. Finally, we blend those adjusted simulations with any of the original simulations that still apply and produce a final forecast.

August 31, 2022

What Biden’s Rising Approval Could Mean For The Midterms

In part three of this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew analyzes why Biden’s approval rating has increased by nearly five points since late July. They also look to the future and discuss how this could possibly impact the midterm elections.

Are More Women Really Registering To Vote Post-Dobbs?

In part two of this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the team debates if a recent analysis of voter registration data showing a surge of women registering to vote after the Supreme Court’s recent abortion decision is a good or bad use of data.

Is Student Debt Relief Good Politics?

After plenty of back-and-forth within the Democratic Party, President Biden announced a plan to use executive action to forgive up to $20,000 of student loan debt last week. In part one of this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew discusses which Americans will be impacted and how the executive action will impact politics and the economy.

August 30, 2022

2022-23 NBA Player Projections

Our projection system identifies similar players throughout NBA history and uses them to develop a probabilistic forecast of what a current NBA player’s future might look like.

August 29, 2022

Politics Podcast: What’s Behind Biden’s Rising Approval

After plenty of back-and-forth within the Democratic Party, President Biden announced a plan to use executive action to forgive up to $20,000 of student loan debt per person last week. In this installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew discusses which Americans will be impacted and how the executive action will impact politics and the economy.

Then the team debates if a recent analysis of voter registration data showing a surge of women registering to vote after the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn the constitutional right to abortion is a good or bad use of data. Finally, the crew analyzes why Biden’s approval rating has increased by nearly 5 percentage points since late July.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast is recorded Mondays and Thursdays. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 729 followers