MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 22

May 6, 2018

Skeleton Found in Pompeii Belonged to Child Seeking Shelter from Deadly Volcanic Eruption

Ancient Origins

Among the ruins of the ancient city of Pompeii, archaeological excavations have revealed the skeleton of a child who died in a volcanic eruption. Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD and destroyed the city of Pompeii, a busy port, along with neighbouring Herculaneum. For many centuries the city lay under the earth, forgotten, near the bustling city of Naples. However, since the eighteenth century it has been extensively excavated and is now a massive archaeological site. Skeletons have been preserved in the ash and debris of Pompeii, and many have been recovered by archaeologists over the years. Pompeii's director Massimo Osanna announced the discovery of the child’s skeleton on the 25th of April.

The child skeleton was found in crouching position in the bath complex of the town. Image: Parco Archeologico de Pompeii

A Child in Hiding

The child is estimated to have been seven or eight years old and was discovered in a crouching position. The skeleton was found in the public thermal bath complex, which was one of the most important public buildings in Pompeii. It is speculated that the child died here while seeking shelter from the volcanic ash, gas, and pumice. The skeleton is relatively intact, and this would suggest that the child was killed by the flow of hot ash and gas that descended upon Pompeii. Those who did not flee the volcanic ash cloud would have perished.

It is estimated that some 10% of Pompeii’s population died, approximately 2000 men, women and children. The majority of them, like the child whose skeleton has been discovered, died either as a result of the pyroclastic flows or they were suffocated by poisonous ash. A pyroclastic flow is a current of hot gas and volcanic matter that is emitted by an erupting volcano and that moves at a great speed. They are often impossible to escape by foot.

The remans of the child were found in one of the baths of the bath complex. Image: Parco Archeologico de Pompeii

Analysis of the Scene

It appears that the pyroclastic flow that swept down from Vesuvius and descended upon Pompeii after the eruption is what has preserved the remains of the child. It is theorized that the flow of hot gas and ash flooded through the windows and doors into the bath complex. The ash and gas flow buried the child, and this solidified over the body when rain fell, encasing the young victim. The skeleton had been sealed in the bath by the pyroclastic flow, according to the American publication Archaeology. This allowed the skeleton to remain undisturbed for millennia.

Maintenance Work Prompted the Find

The find was made during a sweep of the bath complex by a team of archaeologists using the latest scanning equipment, a videoscope. The archaeologists surveyed the area with the equipment as efforts were being made to prevent the ruined walls of the thermal bath from falling. The new technology enabled the archaeological team to investigate areas of the sprawling site that had not been investigated in many decades. With the aid of the videoscope they were able to detect something unusual beneath the surface and this persuaded them to dig in the baths. The thermal baths of the ruined city had, it was believed, already been excavated and the discovery of the skeleton was a surprise to the archaeologists. According to Phys.org, there is speculation that the skeleton had been previously found in the nineteenth century. This was based on the fact that the leg bones appeared to have been placed next to the body, presumably by a person. However, for some reason they had not been removed or even recorded.

Pompeii Director, Massimo Osanna and a colleague inspect the find. Image: Parco Archeologico de Pompeii

A Rare Find for Pompeii

The skeleton was unearthed in February, but the discovery was not publicized at the time, which is standard practice with such finds. It is the first complete skeleton uncovered in two decades and the first child’s skeleton to be uncovered in fifty years. The remains of the child have been removed to a laboratory in Naples for further investigation. The skeleton will undergo a series of extensive tests by an interdisciplinary team of experts. It is hoped that the tests will allow the sex of the child to be established by analysis of its DNA. There will also be tests that seek to determine the age of the child and its general health. The fact that this is the first child to be discovered in fifty years means that experts can now learn more about the lives of the children of Pompeii. The team examining the remains are using the latest technology to discover as much as possible about the skeleton and also what it can tell about life in Pompeii before its fiery destruction.

Top image: The child skeleton recently discovered at Pompeii. Source: Parco Archeologico de Pompeii

By Ed Whelan

Among the ruins of the ancient city of Pompeii, archaeological excavations have revealed the skeleton of a child who died in a volcanic eruption. Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD and destroyed the city of Pompeii, a busy port, along with neighbouring Herculaneum. For many centuries the city lay under the earth, forgotten, near the bustling city of Naples. However, since the eighteenth century it has been extensively excavated and is now a massive archaeological site. Skeletons have been preserved in the ash and debris of Pompeii, and many have been recovered by archaeologists over the years. Pompeii's director Massimo Osanna announced the discovery of the child’s skeleton on the 25th of April.

The child skeleton was found in crouching position in the bath complex of the town. Image: Parco Archeologico de Pompeii

A Child in Hiding

The child is estimated to have been seven or eight years old and was discovered in a crouching position. The skeleton was found in the public thermal bath complex, which was one of the most important public buildings in Pompeii. It is speculated that the child died here while seeking shelter from the volcanic ash, gas, and pumice. The skeleton is relatively intact, and this would suggest that the child was killed by the flow of hot ash and gas that descended upon Pompeii. Those who did not flee the volcanic ash cloud would have perished.

It is estimated that some 10% of Pompeii’s population died, approximately 2000 men, women and children. The majority of them, like the child whose skeleton has been discovered, died either as a result of the pyroclastic flows or they were suffocated by poisonous ash. A pyroclastic flow is a current of hot gas and volcanic matter that is emitted by an erupting volcano and that moves at a great speed. They are often impossible to escape by foot.

The remans of the child were found in one of the baths of the bath complex. Image: Parco Archeologico de Pompeii

Analysis of the Scene

It appears that the pyroclastic flow that swept down from Vesuvius and descended upon Pompeii after the eruption is what has preserved the remains of the child. It is theorized that the flow of hot gas and ash flooded through the windows and doors into the bath complex. The ash and gas flow buried the child, and this solidified over the body when rain fell, encasing the young victim. The skeleton had been sealed in the bath by the pyroclastic flow, according to the American publication Archaeology. This allowed the skeleton to remain undisturbed for millennia.

Maintenance Work Prompted the Find

The find was made during a sweep of the bath complex by a team of archaeologists using the latest scanning equipment, a videoscope. The archaeologists surveyed the area with the equipment as efforts were being made to prevent the ruined walls of the thermal bath from falling. The new technology enabled the archaeological team to investigate areas of the sprawling site that had not been investigated in many decades. With the aid of the videoscope they were able to detect something unusual beneath the surface and this persuaded them to dig in the baths. The thermal baths of the ruined city had, it was believed, already been excavated and the discovery of the skeleton was a surprise to the archaeologists. According to Phys.org, there is speculation that the skeleton had been previously found in the nineteenth century. This was based on the fact that the leg bones appeared to have been placed next to the body, presumably by a person. However, for some reason they had not been removed or even recorded.

Pompeii Director, Massimo Osanna and a colleague inspect the find. Image: Parco Archeologico de Pompeii

A Rare Find for Pompeii

The skeleton was unearthed in February, but the discovery was not publicized at the time, which is standard practice with such finds. It is the first complete skeleton uncovered in two decades and the first child’s skeleton to be uncovered in fifty years. The remains of the child have been removed to a laboratory in Naples for further investigation. The skeleton will undergo a series of extensive tests by an interdisciplinary team of experts. It is hoped that the tests will allow the sex of the child to be established by analysis of its DNA. There will also be tests that seek to determine the age of the child and its general health. The fact that this is the first child to be discovered in fifty years means that experts can now learn more about the lives of the children of Pompeii. The team examining the remains are using the latest technology to discover as much as possible about the skeleton and also what it can tell about life in Pompeii before its fiery destruction.

Top image: The child skeleton recently discovered at Pompeii. Source: Parco Archeologico de Pompeii

By Ed Whelan

Published on May 06, 2018 00:00

May 4, 2018

Vikings in Ireland: Recent Discoveries Shedding New Light on the Fearsome Warriors that Invaded Irish Shores

Ancient Origins

As science progresses and archaeologists are forging new positive relationships with developers around Irish heritage, more secrets from Ireland’s Viking past are coming to light, and they are not just found in burial grounds, unearthed dwellings, and old settlements; they can be found in the DNA of the modern-day Irish people. The Vikings may have only been present in Ireland for three centuries – a drop in the ocean compared to its long and dramatic history – but recent research is showing that their influence was far greater than previously realised.

The Viking Age in Ireland – Do We Need to Revise the Textbooks?

The Viking Age in Ireland is typically seen to have begun with the first recorded raid in 795 AD, taking a turning point in 841 AD when the first settlements were established in Dublin and Annagassan near Dundalk, and ending in 1014 AD with the Viking defeat at the Battle of Clontarf by the Irish High King Brian Boru (although the Vikings continued to play a role in Ireland’s history until the arrival of the Normans in 1171 AD).

Recent archaeological discoveries in Dublin have been raising questions about whether this timeline is accurate, hinting that there may be a lot more to the story. In 2003, excavations were underway as part of the expansion of the Dunnes Stores headquarters on Dublin’s South Great George’s Street, when archaeologists found the bodies of four Vikings aged between their late teens and late twenties.

Radiocarbon dating on the skeletal remains revealed that three of the young Vikings died some time between 670 to 882 AD (Median = 776 AD), a finding which The Journal reports could change the course of decades of research. Did the Vikings set foot in Ireland earlier than currently believed?

Professor Howard Clarke, historian, director of the Medieval Trust, and co-author of Dublin and the Viking World , told Ancient Origins that radiocarbon dating can be problematic as it cannot be used for spot dating. Nevertheless, he added that “The current view is that these burials may well represent early raids on the monastery of Duiblinn (Dubhlinn) before the settlement in 841.”

While historians like Dr Clarke are reluctant to suggest that raids could have been occurring prior to the official ‘start date’ of the Irish Viking Age i.e. 795 AD, the datings on three of the Vikings at least indicates it is a possibility. “They also show that the research into Irish history is never finished,” reported The Journal , “there’s always something more to discover”.

The findings may not prove an earlier start to the Viking Age or that permanent settlement was occurring prior to 841 AD, but they do suggest that the Vikings were paying Dublin some visits before they were ready to unpack their bags.

The Vikings paid Dublin some visits before they eventually settled there (War of the Vikings, John Rickne, Community Manager, Paradox Interactive/ Public Domain )

More Than Just Fearsome Raiders

These early ‘visits’ were in the form of raids and are what gave the Vikings their reputation as a marauding bunch of fearsome invaders who raped, pillaged, and plundered as they went.

Between at least 795 and 836 AD, there were countless ‘hit and run’ raids by both the Norsemen and the Danes, and they unleashed terror upon the land, striking fear in the hearts of the Irish.

They sailed up every creek, shouldering their boats marched from river to river and lake to lake into every tribeland, covering the country with their forts, plundering the rich men’s raths of their cups and vessels and ornaments of gold, sacking the schools and monasteries and churches, and entering every great king’s grave for buried treasure. Their heavy iron swords, their armour, their discipline of war, gave them an overwhelming advantage against the Irish with, as they said, bodies and necks and gentle heads defended only by fine linen. Monks and scholars gathered up their manuscripts and holy ornaments, and fled away for refuge to Europe.” Alice Stopford Green in Irish Nationality (1911).

But was there more to the Vikings than just ferocious and greedy warriors, and did they leave more than fear behind in their wake?

Were the Vikings more than just ferocious warriors? Diorama with Vikings at Archaeological Museum in Stavanger, Norway. (CC BY SA 4.0)

A discovery in Cork city last year highlighted a more civilised side to Viking life in Ireland. Beneath the former Beamish and Crawford brewery, archaeologists retrieved a perfectly-preserved Viking sword . But this was no deadly weapon.

The sword, measuring just 30cm in length, was made of wood – obviously highly unsuitable for the battleground! The finely crafted sword features carved human faces on its handle and would have been used by women for weaving – the flat sides for hammering threads into place on a loom, and the pointed end for picking up the threads for the pattern-making. It was a fine example of Viking craftsmanship. But it is one artifact out of thousands that have revealed aspects of Viking life that are rarely recognised or talked about.

The Viking weaver’s sword unearthed in Cork last year. Credit: BAM Ireland

Excavations undertaken since 1974 at the Viking settlement site located at Wood Quay in Dublin have yielded an enormous Viking time capsule. More than 100 houses and other buildings have been unearthed, along with thousands of objects, including jewellery made from amber, bronze, silver, and gold, iron locks and keys, children’s games and toys, needles, spindles, yarn, and cloth smoothers for the production of textiles, a whalebone ‘ironing board’, silver coins, weights and scales for commercial transactions, craftsmen’s tools made from antler, animal and whalebone, horn and walrus ivory, and personal items such as brushes, combs and hair pins.

Woodworkers, carpenters, coopers and basket weavers were active, producing a range of objects such as wooden bowls, plates, pails, buckets, barrels, tubs, spatulas, platters, cups, spoons, mortars, trays, baskets and boxes,” writes the National Museum of Ireland , where most of the items are now housed. “Evidence for ironworking comes in the form of blacksmith’s tools such as tongs, hammers, knives, saws, chisels, punches, files, whetstones and grindstones… Leather workers produced objects such as shoes, sheaths, scabbards and bags, examples of which have survived. Some leather worker’s tools have also survived - awls, punches, scorers, and at least one wooden last.”

“The Viking town had an agricultural hinterland that sustained it, and many agricultural tools were found in the course of the excavations included wooden shovels, iron spades, planting tools, iron plough socks, billhooks and sickles. The discovery of a wooden churn dash shows that butter making took place within the town. In addition to being excellent mariners, the Vikings were also skilled horsemen. Finds associated with horse riding include stirrups, spurs, harness bells, harness mounts and saddle pommels,” the Museum writes.

Artefacts from Dublin excavations. Credit: National Museum of Ireland

The discoveries at Wood Quay provided an unprecedented look at the Vikings, shedding light on every aspect of life in the early medieval settlements. They were highly experienced farmers, ship builders, traders, blacksmiths, jewellers, metalworkers, cooks, garment makers and craftsmen, and this legacy can still be seen in Ireland today.

The newcomers introduced coins into Ireland – the very earliest (silver pennies) were produced in Dublin under the Viking King Sihtric III around 997 AD; they influenced the language, leaving behind words like ransack, window, market, outlaw, husband, and honeymoon; they brought chicken to the Irish diet, which the Vikings had discovered in China; and they brought items acquired through trade with Persia, Byzantium and Asia. For centuries to follow, and still today, the Scandinavian influence can be seen in literature, crafts, decorative styles, and cuisine.

“They [the Irish] learned from them to build ships, organise naval forces, advance in trade, and live in towns; they used the northern words for the parts of a ship, and the streets of a town. In outward and material civilisation they accepted the latest Scandinavian methods.” (Stopford Green, 1911).

“That’s the other side of Viking life”, Sheila Dooley, Curator and Education Officer at Dublinia told The Journal , “as barbaric as they were and how treacherous and how much they terrorised our society, they also helped establish our towns.”

The Vikings did not succeed in obtaining dominion over Ireland, as they had in England, but their presence had shaped Irish society and culture forever.

There was more, however, that the Vikings left behind.

Top image: Some of the Viking raids ended in death – for the Vikings. (CC BY 2.0)

By Joanna Gillan

Published on May 04, 2018 23:00

May 3, 2018

5 Bayeux Tapestry facts: what is it, why was it made and what story does it tell?

History Extra

The French president Emmanuel Macron recently announced that the Bayeux Tapestry is to go on display in the UK. But what exactly is the tapestry, how old is it, and why is it important?

David Musgrove, publisher of BBC History Magazine, brings you five need-to-know facts about the Bayeux Tapestry…

1 What is the Bayeux Tapestry and what story does it tell?

The Bayeux Tapestry tells one of the most famous stories in British history – that of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, particularly the battle of Hastings, which took place on 14 October 1066.

The Bayeux Tapestry is not a tapestry at all, but rather an embroidery. A tapestry is something that’s woven on a loom, whereas an embroidery is thread stitched onto a cloth background. The tapestry is some 68m long and is composed of several panels that were produced separately and then eventually sewn together to form one long whole. In one case the joining of the panels is inexpertly done, as the marginal lines don’t match up precisely.

The tapestry tells the story of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. The action actually starts a couple of years before the set-piece battle of Hastings, with a discussion between England’s King Edward, the Confessor, and his leading noble (who was also his brother-in-law), Harold Godwinson. The upshot of that conversation is that Harold sets off on a ship to France. He is shipwrecked and captured by a local nobleman there, and then is transferred into the hands of the powerful Duke William of Normandy. Curiously, they then head off together on a military adventure in Brittany, which Harold seems to enthusiastically take part in.

Harold’s time in Normandy ends with him making an oath to William on holy relics. The tapestry does not explain precisely what the nature of the oath is, but other Norman-inclined sources tell us that Harold was swearing to be William’s man in England and to uphold his bid to be king on Edward’s death.

Harold then goes back to England and has another meeting with Edward the Confessor. We don’t know what they talk about, but it’s presumably discussing his stay in Normandy. Then Edward dies, and Harold is declared king by the English nobles. A comet shoots through the sky, which is deemed to be a bad omen for Harold.

Then the action swings back to Normandy. William hears of Harold’s accession and immediately starts building a fleet. The ships cross the Channel and the Norman army establishes itself on English soil. They are shown pillaging, feasting and fortifying their position. Then we get to the battle of Hastings itself, which is portrayed in considerable detail. The upshot of course is that King Harold is slain, with the defeated Englishmen being shown fleeing the field in the last scene of the tapestry.

The ending is abrupt and many people have pondered on whether the tapestry was not actually finished, or has lost its final frames at some point over the centuries. If so, the end panels might have shown William being crowned king of England, as that was the ultimate consequence of the Conquest.

2 Who was the Bayeux Tapestry made for?

This is a question that has been much discussed by historians over the years. Given the fact that the tapestry broadly celebrates and sanctions William’s Conquest of England, for a long time it was considered to have been the work of his Queen Matilda, and the ladies of her court. That view is out of favour now, and the majority of historians would agree that the most likely patron was Odo of Bayeux, the half-brother of Duke William. Odo was a key supporter of the duke and a substantial landowner in both England and Normandy after 1066, as well as being the bishop of Bayeux.

The biggest pointer towards Odo’s likely patronage of the tapestry is that he has a disproportionally large role in the events portrayed, compared to his appearance in other historical accounts of the Conquest. It seems that the designers are going out of their way to stress the importance of Odo in the narrative. On top of that, the key oath scene in which Harold swears to William is depicted in the tapestry as having taken place in Bayeux (Odo’s bishopric), which conflicts with other documents that say the event happened elsewhere in Normandy. Plus, aside from the main historical figures, there is the curious mention of several otherwise insignificant characters in the tapestry, and their names match those of men we know to have been Odo’s retainers.

Other candidates are also in the frame, though: Edward the Confessor’s widow, Queen Edith, has been suggested. She also features in the tapestry and would have had cause to want to show herself in a good light to William after the Conquest, so what better way than commissioning a tapestry that supports his claim to the throne?

Alternatively, it might have been made on the orders of William himself. Clearly he would have been keen to have a permanent record of his victory and his right to have claimed the throne.

Whoever ordered the creation of the tapestry, the follow-up question is – who actually made it? There are a lot of indications to suggest that it was most likely produced in England by English embroiderers. The Latin textual inscriptions above the story-boards use Old English letter forms, and stylistically the work has parallels in Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscripts. Plus, some of the vignettes in the tapestry appear to be based on designs that we know were found in manuscripts held in the library of a monastery in Canterbury, so there are those who argue that it was actually made not just in England, but more precisely in Canterbury.

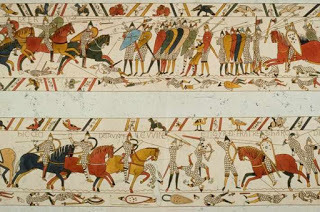

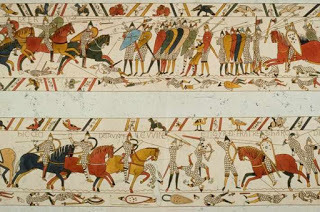

The battle scenes in the Bayeux Tapestry have taught military historians about fighting techniques in the 11th century. (Photo by Walter Rawlings/Robert Harding/Getty Images)

3 When was the Bayeux Tapestry created and why is it important?

We do not have a precise date for when the Bayeux Tapestry was created but the academic consensus is that it must have been produced very soon after the events it depicts. This means that it is a key primary source for students of the Conquest period. The tapestry contains a considerable amount of information not only about the political events surrounding the Conquest story, but also about other aspects of military, social and cultural history. Historians of clothing have gleaned much about Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman garment styles and fashions from the depictions shown in the tapestry, while academics interested in early medieval ship-building, sailing and carpentry have likewise learnt much from the sections dealing with the construction and voyage of William’s invasion fleet.

Military historians have studied the arms and armour shown in the tapestry and analysed the battle scenes to learn more about military techniques and practice at the time. Architectural experts have also been able to interrogate the tapestry for information about building types and materials in the 11th-century from the portrayals of the various structures shown in the story.

So the tapestry is a rich source of information on many aspects of Anglo-Norman life, society, culture and history. But more than that, it’s an astounding and amazing survival of a work of art that is almost 1,000 years old. Its significance derives as much from that as from what it tells us when we study it.

4 Is the Bayeux Tapestry a reliable source of information?

Is any historical primary source of information entirely reliable? No – unless you understand the context of the time in which it was produced, and the motives of those producing it. That’s why the question of who had the tapestry made is critical in helping us to interpret what it tells us. As discussed above, the most likely candidate as the patron of the tapestry is the Norman nobleman Odo of Bayeux, half-brother of William the Conqueror. However, layered on top of that is the likely fact that the actual design and embroidery work was probably done in England, by English hands.

So, although the tapestry is on the face of it a work of art designed to celebrate and legitimise William’s conquest of England, there is also an undercurrent of sympathy to the defeated Anglo-Saxon cause running beneath it. In some ways, the tapestry appears to agree with the Norman narrative of events, as described in the work of writers such as William of Jumieges and William of Poitiers. However, it is also surprisingly respectful of William’s enemy, King Harold II, who is shown as a great and brave lord, rather than just a deceitful usurper.

What’s important to note is that as a source of information on the political events to the Conquest period, the tapestry actually offers very limited definitive evidence. The Latin inscriptions that run above the pictorial narrative are terse and limited in number. This ambiguity means we do not know, for instance, what Edward the Confessor and Harold are discussing in the first scene of the story. Nothing is said other than ‘King Edward’ above the frame, so we are entirely in the dark about the meeting and must infer from other sources as to what the designers are trying to tell us. That is a problem that persists throughout the tapestry, where we are constantly invited to infer what is happening from the pictures, rather than being told what is happening with words.

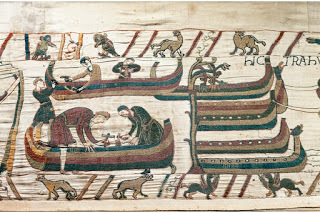

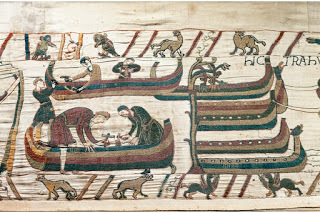

Maritime historians have learnt much about ship-building from the scenes in the Bayeux Tapestry depicting William’s fleet under construction. (Photo by DEA/M. Seamuller/Getty Images)

5. What was the Bayeux Tapestry used for?

This is a difficult question to answer, if we are focusing on the immediate post-Conquest period, because we have no evidence whatsoever to call upon. Assuming that the patron of the tapestry was, as is widely accepted today, Bishop Odo of Bayeux, then it may have been used to decorate the cathedral that he had constructed in Bayeux during his lifetime. It may even have been designed as an ornament for the consecration of that building in 1077, though some historians dispute that.

Presumably whoever did have the tapestry made would have wanted others to come view it and share in the story it tells, as well as be impressed by the magnificence of both the patron (for being the benefactor of such a great work), and of Duke William himself for orchestrating his victory. How that would have happened is not clear – if it was displayed in a cathedral, illumination would have been dim to say the least.

The tapestry could perhaps instead have been displayed in a secular building, or it could have been displayed temporarily and then stored away, maybe being brought out for particular gatherings, when there was someone on hand to tell the story in person as well.

What we do know is that from at least 1476 onwards, the tapestry was held in Bayeux Cathedral (we don’t know where it was prior to that) because it’s detailed in an inventory of that date. It was traditionally brought out for display in the cathedral at a certain point in the year, and then stored away. This helps to explain why the tapestry survived at all – it wasn’t on permanent view and thus not subject to the risks of being regularly exposed to the elements.

As we move forward into more recent times, the tapestry has continued to have a propaganda purpose. Napoleon considered it important when he was readying his plans to invade Britain at the start of the 19th century and had it brought to Paris for display. In the Second World War it was again deemed a useful tool by the Nazis, where it was studied as part of a research project to demonstrate the Germanic origins of European culture (and moved to Paris for safe-keeping).

David Musgrove is the publisher and former editor of BBC History Magazine.

The French president Emmanuel Macron recently announced that the Bayeux Tapestry is to go on display in the UK. But what exactly is the tapestry, how old is it, and why is it important?

David Musgrove, publisher of BBC History Magazine, brings you five need-to-know facts about the Bayeux Tapestry…

1 What is the Bayeux Tapestry and what story does it tell?

The Bayeux Tapestry tells one of the most famous stories in British history – that of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, particularly the battle of Hastings, which took place on 14 October 1066.

The Bayeux Tapestry is not a tapestry at all, but rather an embroidery. A tapestry is something that’s woven on a loom, whereas an embroidery is thread stitched onto a cloth background. The tapestry is some 68m long and is composed of several panels that were produced separately and then eventually sewn together to form one long whole. In one case the joining of the panels is inexpertly done, as the marginal lines don’t match up precisely.

The tapestry tells the story of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. The action actually starts a couple of years before the set-piece battle of Hastings, with a discussion between England’s King Edward, the Confessor, and his leading noble (who was also his brother-in-law), Harold Godwinson. The upshot of that conversation is that Harold sets off on a ship to France. He is shipwrecked and captured by a local nobleman there, and then is transferred into the hands of the powerful Duke William of Normandy. Curiously, they then head off together on a military adventure in Brittany, which Harold seems to enthusiastically take part in.

Harold’s time in Normandy ends with him making an oath to William on holy relics. The tapestry does not explain precisely what the nature of the oath is, but other Norman-inclined sources tell us that Harold was swearing to be William’s man in England and to uphold his bid to be king on Edward’s death.

Harold then goes back to England and has another meeting with Edward the Confessor. We don’t know what they talk about, but it’s presumably discussing his stay in Normandy. Then Edward dies, and Harold is declared king by the English nobles. A comet shoots through the sky, which is deemed to be a bad omen for Harold.

Then the action swings back to Normandy. William hears of Harold’s accession and immediately starts building a fleet. The ships cross the Channel and the Norman army establishes itself on English soil. They are shown pillaging, feasting and fortifying their position. Then we get to the battle of Hastings itself, which is portrayed in considerable detail. The upshot of course is that King Harold is slain, with the defeated Englishmen being shown fleeing the field in the last scene of the tapestry.

The ending is abrupt and many people have pondered on whether the tapestry was not actually finished, or has lost its final frames at some point over the centuries. If so, the end panels might have shown William being crowned king of England, as that was the ultimate consequence of the Conquest.

2 Who was the Bayeux Tapestry made for?

This is a question that has been much discussed by historians over the years. Given the fact that the tapestry broadly celebrates and sanctions William’s Conquest of England, for a long time it was considered to have been the work of his Queen Matilda, and the ladies of her court. That view is out of favour now, and the majority of historians would agree that the most likely patron was Odo of Bayeux, the half-brother of Duke William. Odo was a key supporter of the duke and a substantial landowner in both England and Normandy after 1066, as well as being the bishop of Bayeux.

The biggest pointer towards Odo’s likely patronage of the tapestry is that he has a disproportionally large role in the events portrayed, compared to his appearance in other historical accounts of the Conquest. It seems that the designers are going out of their way to stress the importance of Odo in the narrative. On top of that, the key oath scene in which Harold swears to William is depicted in the tapestry as having taken place in Bayeux (Odo’s bishopric), which conflicts with other documents that say the event happened elsewhere in Normandy. Plus, aside from the main historical figures, there is the curious mention of several otherwise insignificant characters in the tapestry, and their names match those of men we know to have been Odo’s retainers.

Other candidates are also in the frame, though: Edward the Confessor’s widow, Queen Edith, has been suggested. She also features in the tapestry and would have had cause to want to show herself in a good light to William after the Conquest, so what better way than commissioning a tapestry that supports his claim to the throne?

Alternatively, it might have been made on the orders of William himself. Clearly he would have been keen to have a permanent record of his victory and his right to have claimed the throne.

Whoever ordered the creation of the tapestry, the follow-up question is – who actually made it? There are a lot of indications to suggest that it was most likely produced in England by English embroiderers. The Latin textual inscriptions above the story-boards use Old English letter forms, and stylistically the work has parallels in Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscripts. Plus, some of the vignettes in the tapestry appear to be based on designs that we know were found in manuscripts held in the library of a monastery in Canterbury, so there are those who argue that it was actually made not just in England, but more precisely in Canterbury.

The battle scenes in the Bayeux Tapestry have taught military historians about fighting techniques in the 11th century. (Photo by Walter Rawlings/Robert Harding/Getty Images)

3 When was the Bayeux Tapestry created and why is it important?

We do not have a precise date for when the Bayeux Tapestry was created but the academic consensus is that it must have been produced very soon after the events it depicts. This means that it is a key primary source for students of the Conquest period. The tapestry contains a considerable amount of information not only about the political events surrounding the Conquest story, but also about other aspects of military, social and cultural history. Historians of clothing have gleaned much about Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman garment styles and fashions from the depictions shown in the tapestry, while academics interested in early medieval ship-building, sailing and carpentry have likewise learnt much from the sections dealing with the construction and voyage of William’s invasion fleet.

Military historians have studied the arms and armour shown in the tapestry and analysed the battle scenes to learn more about military techniques and practice at the time. Architectural experts have also been able to interrogate the tapestry for information about building types and materials in the 11th-century from the portrayals of the various structures shown in the story.

So the tapestry is a rich source of information on many aspects of Anglo-Norman life, society, culture and history. But more than that, it’s an astounding and amazing survival of a work of art that is almost 1,000 years old. Its significance derives as much from that as from what it tells us when we study it.

4 Is the Bayeux Tapestry a reliable source of information?

Is any historical primary source of information entirely reliable? No – unless you understand the context of the time in which it was produced, and the motives of those producing it. That’s why the question of who had the tapestry made is critical in helping us to interpret what it tells us. As discussed above, the most likely candidate as the patron of the tapestry is the Norman nobleman Odo of Bayeux, half-brother of William the Conqueror. However, layered on top of that is the likely fact that the actual design and embroidery work was probably done in England, by English hands.

So, although the tapestry is on the face of it a work of art designed to celebrate and legitimise William’s conquest of England, there is also an undercurrent of sympathy to the defeated Anglo-Saxon cause running beneath it. In some ways, the tapestry appears to agree with the Norman narrative of events, as described in the work of writers such as William of Jumieges and William of Poitiers. However, it is also surprisingly respectful of William’s enemy, King Harold II, who is shown as a great and brave lord, rather than just a deceitful usurper.

What’s important to note is that as a source of information on the political events to the Conquest period, the tapestry actually offers very limited definitive evidence. The Latin inscriptions that run above the pictorial narrative are terse and limited in number. This ambiguity means we do not know, for instance, what Edward the Confessor and Harold are discussing in the first scene of the story. Nothing is said other than ‘King Edward’ above the frame, so we are entirely in the dark about the meeting and must infer from other sources as to what the designers are trying to tell us. That is a problem that persists throughout the tapestry, where we are constantly invited to infer what is happening from the pictures, rather than being told what is happening with words.

Maritime historians have learnt much about ship-building from the scenes in the Bayeux Tapestry depicting William’s fleet under construction. (Photo by DEA/M. Seamuller/Getty Images)

5. What was the Bayeux Tapestry used for?

This is a difficult question to answer, if we are focusing on the immediate post-Conquest period, because we have no evidence whatsoever to call upon. Assuming that the patron of the tapestry was, as is widely accepted today, Bishop Odo of Bayeux, then it may have been used to decorate the cathedral that he had constructed in Bayeux during his lifetime. It may even have been designed as an ornament for the consecration of that building in 1077, though some historians dispute that.

Presumably whoever did have the tapestry made would have wanted others to come view it and share in the story it tells, as well as be impressed by the magnificence of both the patron (for being the benefactor of such a great work), and of Duke William himself for orchestrating his victory. How that would have happened is not clear – if it was displayed in a cathedral, illumination would have been dim to say the least.

The tapestry could perhaps instead have been displayed in a secular building, or it could have been displayed temporarily and then stored away, maybe being brought out for particular gatherings, when there was someone on hand to tell the story in person as well.

What we do know is that from at least 1476 onwards, the tapestry was held in Bayeux Cathedral (we don’t know where it was prior to that) because it’s detailed in an inventory of that date. It was traditionally brought out for display in the cathedral at a certain point in the year, and then stored away. This helps to explain why the tapestry survived at all – it wasn’t on permanent view and thus not subject to the risks of being regularly exposed to the elements.

As we move forward into more recent times, the tapestry has continued to have a propaganda purpose. Napoleon considered it important when he was readying his plans to invade Britain at the start of the 19th century and had it brought to Paris for display. In the Second World War it was again deemed a useful tool by the Nazis, where it was studied as part of a research project to demonstrate the Germanic origins of European culture (and moved to Paris for safe-keeping).

David Musgrove is the publisher and former editor of BBC History Magazine.

Published on May 03, 2018 23:30

May 2, 2018

More than a Dozen Mysterious Prehistoric Tunnels in Cornwall, England, Mystify Researchers

Ancient Origins

More than a dozen tunnels have been found in Cornwall, England, that are unique in the British Isles. No one knows why Iron Age people created them. The fact that the ancients supported their tops and sides with stone, suggests that they wanted them to endure, and that they have, for about 2,400 years.

Many of the fogous, as they’re called in Cornish after their word for cave, ogo, were excavated by antiquarians who didn’t keep records, so their purpose is hard to fathom, says a BBC Travel story on the mysterious structures.

The landscape of Cornwall is covered with hundreds of ancient, stone, man-made features, including enclosures, cliff castles, roundhouses, ramparts and forts. In terms of stone monuments, the Cornwall countryside has barrows, menhirs, dolmens, cairns and of course stone circles. In addition, there are 13 inscribed stones.

The Cornish landscape is dotted with ancient megalithic structures like this Lanyon Quoit Megalith ( public domain )

“Obviously, all of this monument building did not take place at the same time. Man has been leaving his mark on the surface of the planet for thousands of years and each civilisation has had its own method of honouring their dead and/or their deities,” says the site Cornwall in Focus.

The site says Cornwall has 74 Bronze Age structures, 80 from the Iron Age, 55 from the Neolithic and one from the Mesolithic. In addition, there are nine Roman sites and 24 post-Roman. The Mesolithic dates from 8000 to 4500 BC, so people have been occupying this southwestern peninsula of Britain for a long, long time.

About 150 generations of people worked the land there. But it’s believed the fogous date to the Iron Age, which lasted from about 700 BC to 43 AD. Though they’re unique, the fogou tunnels of Cornwall are similar to souterrains in Scotland, Ireland, Normandy and Brittany, says the BBC.

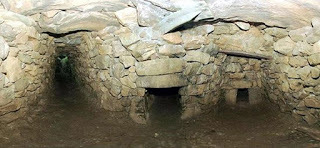

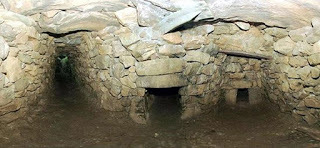

Carn Euny fogou in Cornwall ( public domain )

The fogous required considerable investment of time and resources “and no one knows why they would have done so,” says the BBC. It’s interesting to note that all 14 of the fogous have been found within the confines of prehistoric settlements.

Because the society was preliterate, there are no written records that explain the enigmatic structures.

“There are only a couple that have been excavated in modern times – and they don’t seem to be structures that really easily give up their secrets,” Susan Greaney, head properties historian of English Heritage, told the BBC.

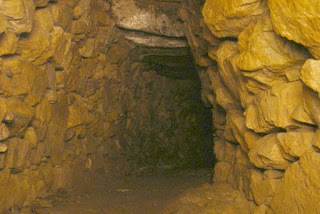

The mystery of their construction is amplified at Halliggye Fogou, the best-preserved such tunnel in Cornwall. It measures 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) high. The 8.4 -meter-long (27.6 feet) passage narrows at its end in a tunnel 4 meters (13.124 feet) long and .75 meter (2.46 feet) tall.

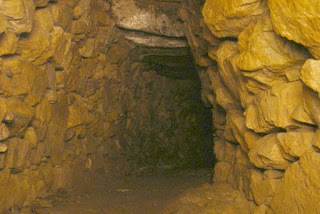

Main chamber of the Halliggye Fogou ( public domain )

Another tunnel 27 meters (88.6 feet) long branches off to the left of the main chamber and gets darker the farther in one goes. There is what the BBC calls a “final creep” at the end of this passage that has stone lip upon which one could trip.

“In other words, none of it seemed designed for easy access – a characteristic that’s as emblematic of fogous as it is perplexing,” wrote the BBC’s Amanda Ruggeri.

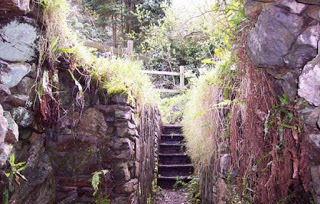

Halliggye Fogou. One of the largest and best preserved of these fogou (curious underground passages) this one originally passed under the rampart of a defended Iron Age settlement. ( geograph.org.uk)

Some have speculated they were places to hide, though the lintels of many of them are visible on the surface and Ruggeri says they would be forbidding places to stay if one sought refuge.

Still others have speculated they were burial chambers. An antiquarian who entered Halliggye in 1803 wrote that it had funerary urns. But others entered by the hole he made in the roof, and all the urns are gone. No bones or ashes have been discovered in the six tunnels that modern archaeologists have examined. No remnants of grains have been found, perhaps because the soil is acidic. No ingots from mining have been discovered.

This elimination of storage, mining or burial purposes has led some to speculate that they were perhaps ceremonial or religious structures where people worshiped gods. “These were lost religions,” said archaeologist James Gossip, who led Ruggeri on a tour of Halligye fogou.

“We don’t know what people were worshiping. There’s no reason they couldn’t have had a ceremonial, spiritual purpose as well as, say, storage.”

He added that the purpose and use of the fogous probably changed over the hundreds of years they were in use.

Top image: The Halliggye Fogou ( megalithics.com)

By Mark Miller

More than a dozen tunnels have been found in Cornwall, England, that are unique in the British Isles. No one knows why Iron Age people created them. The fact that the ancients supported their tops and sides with stone, suggests that they wanted them to endure, and that they have, for about 2,400 years.

Many of the fogous, as they’re called in Cornish after their word for cave, ogo, were excavated by antiquarians who didn’t keep records, so their purpose is hard to fathom, says a BBC Travel story on the mysterious structures.

The landscape of Cornwall is covered with hundreds of ancient, stone, man-made features, including enclosures, cliff castles, roundhouses, ramparts and forts. In terms of stone monuments, the Cornwall countryside has barrows, menhirs, dolmens, cairns and of course stone circles. In addition, there are 13 inscribed stones.

The Cornish landscape is dotted with ancient megalithic structures like this Lanyon Quoit Megalith ( public domain )

“Obviously, all of this monument building did not take place at the same time. Man has been leaving his mark on the surface of the planet for thousands of years and each civilisation has had its own method of honouring their dead and/or their deities,” says the site Cornwall in Focus.

The site says Cornwall has 74 Bronze Age structures, 80 from the Iron Age, 55 from the Neolithic and one from the Mesolithic. In addition, there are nine Roman sites and 24 post-Roman. The Mesolithic dates from 8000 to 4500 BC, so people have been occupying this southwestern peninsula of Britain for a long, long time.

About 150 generations of people worked the land there. But it’s believed the fogous date to the Iron Age, which lasted from about 700 BC to 43 AD. Though they’re unique, the fogou tunnels of Cornwall are similar to souterrains in Scotland, Ireland, Normandy and Brittany, says the BBC.

Carn Euny fogou in Cornwall ( public domain )

The fogous required considerable investment of time and resources “and no one knows why they would have done so,” says the BBC. It’s interesting to note that all 14 of the fogous have been found within the confines of prehistoric settlements.

Because the society was preliterate, there are no written records that explain the enigmatic structures.

“There are only a couple that have been excavated in modern times – and they don’t seem to be structures that really easily give up their secrets,” Susan Greaney, head properties historian of English Heritage, told the BBC.

The mystery of their construction is amplified at Halliggye Fogou, the best-preserved such tunnel in Cornwall. It measures 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) high. The 8.4 -meter-long (27.6 feet) passage narrows at its end in a tunnel 4 meters (13.124 feet) long and .75 meter (2.46 feet) tall.

Main chamber of the Halliggye Fogou ( public domain )

Another tunnel 27 meters (88.6 feet) long branches off to the left of the main chamber and gets darker the farther in one goes. There is what the BBC calls a “final creep” at the end of this passage that has stone lip upon which one could trip.

“In other words, none of it seemed designed for easy access – a characteristic that’s as emblematic of fogous as it is perplexing,” wrote the BBC’s Amanda Ruggeri.

Halliggye Fogou. One of the largest and best preserved of these fogou (curious underground passages) this one originally passed under the rampart of a defended Iron Age settlement. ( geograph.org.uk)

Some have speculated they were places to hide, though the lintels of many of them are visible on the surface and Ruggeri says they would be forbidding places to stay if one sought refuge.

Still others have speculated they were burial chambers. An antiquarian who entered Halliggye in 1803 wrote that it had funerary urns. But others entered by the hole he made in the roof, and all the urns are gone. No bones or ashes have been discovered in the six tunnels that modern archaeologists have examined. No remnants of grains have been found, perhaps because the soil is acidic. No ingots from mining have been discovered.

This elimination of storage, mining or burial purposes has led some to speculate that they were perhaps ceremonial or religious structures where people worshiped gods. “These were lost religions,” said archaeologist James Gossip, who led Ruggeri on a tour of Halligye fogou.

“We don’t know what people were worshiping. There’s no reason they couldn’t have had a ceremonial, spiritual purpose as well as, say, storage.”

He added that the purpose and use of the fogous probably changed over the hundreds of years they were in use.

Top image: The Halliggye Fogou ( megalithics.com)

By Mark Miller

Published on May 02, 2018 23:00

May 1, 2018

Gladiator Helmets: Fit for Purpose, Not Just Protection

Ancient Origins

The gladiator is most likely the first image one calls to mind when thinking about entertainment in ancient Rome. As most would already know, gladiators fought either each other or wild animals, in amphitheatres, such as the Colosseum in Rome, across the Roman world. There are various types of gladiators, each distinguished by the weapons and armor that were used. Thus, there were also a variety of gladiator helmets, which will be explored in this article.

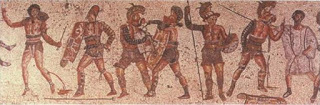

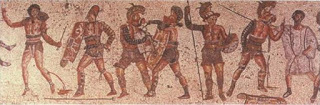

A variety of gladiator types with their armor and weapons are shown on the Zliten mosaic. ( Public Domain )

Who wore Gladiator Helmets?

One may begin with the fact that not all gladiators wore helmets. As an example, the retiarius (which may be literally translated to mean ‘net-man’ or ‘net-fighter’) is a type of gladiator that does not use a helmet. This gladiator is armed with a net, a trident, and a dagger. Compared to other gladiator types, the retiarius wore little armor, which consisted of an arm guard, a shoulder guard, and fabric padding. Thus, the retiarius relied on speed and agility in the arena. Needless to say, a heavy helmet would be a liability, and thus was not used by the retiarius. Another type of gladiator that did not use a helmet was the gladiatrix, or female gladiator. Battles involving gladiatrices were rare, and the lack of helmets was meant to emphasize their sex.

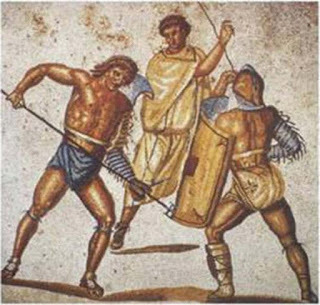

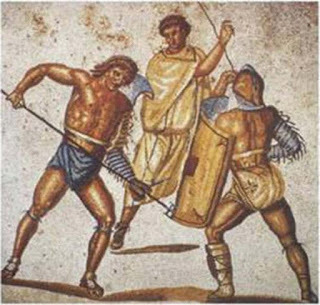

A retiarius gladiator stabs at his secutor opponent with his trident. Mosaic from the villa at Nennig, 2nd-3rd century AD ( Public Domain )

The Secutor Helmet

The retiarius and the gladiatrices may be said to be the exceptions, rather than the norm, as most other types of gladiators were equipped with helmets. It may be added that the design of the helmets depended on the class of gladiator. For instance, the secutor (meaning ‘follower’ or ‘chaser’) was regularly pitted against the retiarius, and thus had a helmet devised specifically to protect him from the weapons of his opponent. The helmet of the secutor is shaped like the head of a fish, considering that its traditional opponent was meant to represent a fisherman. To maximise protection against the thrusting attacks of the retiarius’ trident, the secutor’s helmet was fitted only with two small eye-holes. The downside to this, however, was the visibility was limited. Additionally, the helmet had a rounded top, and lacked decorations, so as to prevent it from getting caught in the net of the retiarius.

Iron secutor style helmet from Herculaneum, 1st century. ( CC BY-NC-SA-2.0 )

Thracian Style Helmets

In contrast to the plain helmet of the secutor, some gladiator helmets had elaborate ornamentations. This may be seen, for instance, in the helmet of the Thraex (also known as Thracian). An example of this helmet is exhibited in the Louvre in Paris. This particular helmet was made of bronze and was unearthed in Pompeii. In terms of embellishments, this Thraex helmet has a crest decorated with plumes, and terminating in a griffin’s head. Additionally, there is a silver-plated head of Medusa on the front of the helmet. Plume holders are also present on either side of the helmet, which allowed feathers to be attached.

The helmet of a Thracian gladiator, the Louvre. (Image: © RMN, Musée du Louvre )

Murmillo Head Protection

It may be said that the design of the helmet used by the Thraex is quite similar to that worn by the murmillo, another type of gladiator. Both types of gladiators were heavily armed, and thus had a similar sort of helmet. The helmet of the murmillo, like that of the Thraex, had a broad brim, as well as a crest, which was adorned with plumes or horsehair. This crest would typically have a stylized fish on it, as the murmillo is sometimes referred to as the ‘fishman’. In contrast to the helmet of the secutor, those used by the thraex and the murmillo have ‘grill’ visors with multiple holes, which made breathing and seeing a bit easier.

Helmet of a murmillo (a type of gladiator during the Roman Imperial age), 2nd century AD, Neues Museum, Berlin. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Last of all, some attention may be drawn to a rather curious type of gladiator called the andabata (which may be translated to mean ‘blindfolded gladiator’). This type of gladiator was referred to by Cicero in one of the letters to his friends. This type of gladiator is said to have fought on horseback - although this is questioned by some - and wore a type of helmet which had no eyeholes. In other words, such gladiators would be charging blindly at one another in the arena.

Top image: The helmet of a gladiator (reproduction). ( Public Domain )

By Wu Mingren

The gladiator is most likely the first image one calls to mind when thinking about entertainment in ancient Rome. As most would already know, gladiators fought either each other or wild animals, in amphitheatres, such as the Colosseum in Rome, across the Roman world. There are various types of gladiators, each distinguished by the weapons and armor that were used. Thus, there were also a variety of gladiator helmets, which will be explored in this article.

A variety of gladiator types with their armor and weapons are shown on the Zliten mosaic. ( Public Domain )

Who wore Gladiator Helmets?

One may begin with the fact that not all gladiators wore helmets. As an example, the retiarius (which may be literally translated to mean ‘net-man’ or ‘net-fighter’) is a type of gladiator that does not use a helmet. This gladiator is armed with a net, a trident, and a dagger. Compared to other gladiator types, the retiarius wore little armor, which consisted of an arm guard, a shoulder guard, and fabric padding. Thus, the retiarius relied on speed and agility in the arena. Needless to say, a heavy helmet would be a liability, and thus was not used by the retiarius. Another type of gladiator that did not use a helmet was the gladiatrix, or female gladiator. Battles involving gladiatrices were rare, and the lack of helmets was meant to emphasize their sex.

A retiarius gladiator stabs at his secutor opponent with his trident. Mosaic from the villa at Nennig, 2nd-3rd century AD ( Public Domain )

The Secutor Helmet

The retiarius and the gladiatrices may be said to be the exceptions, rather than the norm, as most other types of gladiators were equipped with helmets. It may be added that the design of the helmets depended on the class of gladiator. For instance, the secutor (meaning ‘follower’ or ‘chaser’) was regularly pitted against the retiarius, and thus had a helmet devised specifically to protect him from the weapons of his opponent. The helmet of the secutor is shaped like the head of a fish, considering that its traditional opponent was meant to represent a fisherman. To maximise protection against the thrusting attacks of the retiarius’ trident, the secutor’s helmet was fitted only with two small eye-holes. The downside to this, however, was the visibility was limited. Additionally, the helmet had a rounded top, and lacked decorations, so as to prevent it from getting caught in the net of the retiarius.

Iron secutor style helmet from Herculaneum, 1st century. ( CC BY-NC-SA-2.0 )

Thracian Style Helmets

In contrast to the plain helmet of the secutor, some gladiator helmets had elaborate ornamentations. This may be seen, for instance, in the helmet of the Thraex (also known as Thracian). An example of this helmet is exhibited in the Louvre in Paris. This particular helmet was made of bronze and was unearthed in Pompeii. In terms of embellishments, this Thraex helmet has a crest decorated with plumes, and terminating in a griffin’s head. Additionally, there is a silver-plated head of Medusa on the front of the helmet. Plume holders are also present on either side of the helmet, which allowed feathers to be attached.

The helmet of a Thracian gladiator, the Louvre. (Image: © RMN, Musée du Louvre )

Murmillo Head Protection

It may be said that the design of the helmet used by the Thraex is quite similar to that worn by the murmillo, another type of gladiator. Both types of gladiators were heavily armed, and thus had a similar sort of helmet. The helmet of the murmillo, like that of the Thraex, had a broad brim, as well as a crest, which was adorned with plumes or horsehair. This crest would typically have a stylized fish on it, as the murmillo is sometimes referred to as the ‘fishman’. In contrast to the helmet of the secutor, those used by the thraex and the murmillo have ‘grill’ visors with multiple holes, which made breathing and seeing a bit easier.

Helmet of a murmillo (a type of gladiator during the Roman Imperial age), 2nd century AD, Neues Museum, Berlin. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Last of all, some attention may be drawn to a rather curious type of gladiator called the andabata (which may be translated to mean ‘blindfolded gladiator’). This type of gladiator was referred to by Cicero in one of the letters to his friends. This type of gladiator is said to have fought on horseback - although this is questioned by some - and wore a type of helmet which had no eyeholes. In other words, such gladiators would be charging blindly at one another in the arena.

Top image: The helmet of a gladiator (reproduction). ( Public Domain )

By Wu Mingren

Published on May 01, 2018 23:00

April 30, 2018

We brewed an ancient Graeco-Roman beer and here’s how it tastes

Ancient Origins

Matt Gibbs /The Conversation

Beer is the most consumed alcoholic beverage in the world; it is also the most popular drink after water and tea . In the modern world, however, little consideration is typically given to how beer developed with respect to taste. Even less is given to why beer is thought of in the way that it is.

But today, Canada is in the middle of a beer renaissance. A relative explosion of craft breweries has led to a renewed interest in different methods of brewing and in different types of beer recipes.

In turn, this has driven interest into historical methods of brewing. It is a rather romantic idea: That very old brewing processes are somehow superior to those of the modern world. While almost all of the beer on the market today is quantitatively and qualitatively better than that produced in the ancient world, attempts made by both historians and breweries recently have had some good results.

For example, the collaboration between University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Patrick McGovern and Dogfish Head Brewery that resulted in their “Midas Touch”, based on the sediment found in vessels discovered in the Tomb of Midas in central Turkey, and the Sleepy Giant Brewing Company’s ancient beers created as part of Lakehead University’s Research and Innovation Week.

Beer made an old-fashioned way is shown at Barn Hammer Brewing Company in Winnipeg in March 2018. THE CANADIAN PRESS/David Lipnowski

Why re-create ancient beer and mead?

From an academic point of view, researchers have realized eating and drinking are important social, economic and even political activities. In the ancient world, food, drink and their consumption were important indicators of culture, ethnicity and class. Romans were set apart from non-Romans in several ways: Those living in cities versus those who didn’t, those who farmed in one place versus those who moved around, and so on.

One of the other ways in which this distinction was made was in the different foods people ate and in the liquids they drank. This is clear in the ancient Graeco-Roman debate surrounding those who drank wine and those who drank beer.

Although the saying “you are what you eat” is a fact in terms of physiology, the Romans also believed that “you are what you drink.” So Romans drank wine, non-Romans drank beer.

These indicators (real or not) even exist today: The English drink tea, Americans drink coffee; Canadians drink rye, the Scottish drink scotch.

So the re-creation of ancient beer and mead (an alcoholic beverage made by fermenting honey and other liquids) allows us to examine many things. Among them are these cultural and ethnic considerations, but there are other important and interesting questions that can be answered. How has the brewing process transformed? How have our palates changed?

Mead beaker. Matt Gibbs, Author provided (No reuse)

The “Roman” recipes and their recreation

The Romans left us a variety of different recipes for food and drink. Two of them form the basis of an ongoing research project between the co-owners of Barn Hammer Brewing Company — Tyler Birch and Brian Westcott — and myself that attempts to answer some of these questions.

The first is a recipe for beer that dates to the fourth century Common Era (CE). It appears in the work of Zosimus, an alchemist, who lived in Panopolis, Egypt, when it was part of the Roman empire. The second is a recipe for a mead probably from Italy and dating to the first century CE, written by a Roman senator called Columella.

Beer mash. Matt Gibbs, Author provided (No reuse)

Both recipes are quite clear concerning ingredients, with the exception of yeast. Yeast, or more appropriately a yeast culture, was often made from dough saved from a day’s baking. Alternatively, one could simply leave mixtures out in the open. But the processes and measurements in them are more difficult to recreate.

The brewing of the beer, for instance, required the use of barley bread made with a sourdough culture: Basically a lump of sourdough bread left uncovered. To keep the culture alive while being baked required a long, slow baking process at a low temperature for 18 hours.

Zosimus never specified how much water or bread was needed for a single batch; this was left open to the brewers’ interpretation. A mix of three parts water to one part bread was brewed and left to ferment for nearly three weeks.

The brewing of the mead was a much easier process. Closely following Columella’s recipe, we mixed honey and wine must . The recipe in this case provided some measurements, and from there we were able to extrapolate a workable mix of roughly three parts must to one part honey.

We then added wine yeast and sealed the containers. These were placed in Barn Hammer’s furnace room for 31 days in an attempt to imitate the conditions of a Roman loft.

What did we learn?

First of all, it’s worth noting that the principles of brewing have not changed significantly; fundamentally, the process of brewing both beer and mead is arguably the same now as it was 2,000 years ago. But as true as that may be, even now the production of Zosimus’ beer — particularly the baking of the bread — was labour-intensive.

Mead decanting. (Author provided)

This led to another question: Did the link between baking and brewing depicted so clearly in ancient Egyptian material culture and archaeology persist even centuries later?

Second, we recreated beer and mead from the Roman Empire as faithfully as we were able. The data all suggest that the beer is a beer, and the mead is a mead, right down to the pH level: The beer, for instance, stands at pH 4.3 which is what one would expect from a beer after fermentation.

Third, as the photos here make clear, the mead looked like red wine, the beer was quite pale but cloudy. Neither case was particularly surprising, but what was interesting was the difference between the first tasting of the beer and the second 10 days later.

In the former, the beer looked like a sourdough milkshake; in the latter, the beer looked like a pale craft ale, and one that would not be out of place in the modern craft beer market.

Fourth, with respect to taste, the beer was sour but quite smooth, and had a relatively low ABV - Alcohol By Volume: the measurement that tells you what percentage of beer or mead is alcohol — around three to four per cent. The sour taste resulted in diverse opinions: Some people liked it; others hated it. The mead was incredibly sweet; it smelled like a fortified wine due to presence of Fusel alcohols , and had an ABV upwards of 12 per cent.

While general tastes may have changed, there are modern palates that appreciate ancient beer and mead. Is this a physiological question? Perhaps, but what seems clear is that ancient indicators based on what people drank are likely more indicative not only of the Romans’ beliefs and opinions about non-Romans, but also their prejudices against them.

Ultimately, what the project suggests so far is that while the brewing process may not have changed that much, in some ways neither have we.

Top image: Left to right- Barn Hammer Brewing Company Head Brewer Brian Westcott, Matt Gibbs of the University of Winnipeg and Barn Hammer owner Tyler Birch teamed up to re-create an ancient beer. THE CANADIAN PRESS/David Lipnowski/ The Conversation

The article ‘ We brewed an ancient Graeco-Roman beer and here’s how it tastes ’ by Matt Gibbs was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Published on April 30, 2018 23:30

April 29, 2018

Danish Archaeologists Strongly Disagree About Viking Colors

Thor News

Was this how the royal hall in Lejre was painted? (Photo: Sagnlandet Lejre)

Recently, Danish archaeologists attended the seminar “Farverige Vikinger” (Colorful Vikings) discussing the colors on a reconstructed royal hall dating back to the Viking Age. The outcome was colorful disagreement and frustration.

In 2009, archaeologist excavated a royal hall in Lejre, Denmark, which turned out to be one of the largest Viking Age buildings ever discovered.

Now, the 60 meters long and oval-shaped longhouse made of oak is under reconstruction and no one with certainty can tell if it was painted, and if so, in which colors.

Although there are found a number of painted Viking Age wooden objects that might reveal the color fashion of the time period, you never can be absolutely certain, says chemist Mads Christian Christensen at the National Museum of Denmark to Danish research portal videnskap.dk.

Whitewashed Theory

Some archaeologists who participated in the seminar put forward a completely different theory when it came to Viking Age colors: The wooden houses, at least the royal halls, were gleaming white.

The rationale is that there are found traces of white chalk in the remains of the royal halls of Tissø and Lejre, and consequently it is likely that Viking houses were whitewashed.

The archaeologist who promoted the theory said that white houses are visible from a long distance, functional as both a status symbol and landmark.

Moreover, indoor and outdoor chalking would both serve as efficient insulation and provide a better indoor climate.

It was also argued that white chalking would provide more light in the dark months of the year.

The theory has some weaknesses, partly because a white-painted house in winter, in a dark and snowy Scandinavia, would “totally disappear”.

Strong Colors

There are numerous references from both archaeological findings and the Norse sagas documenting the Vikings’ use of strong colors:

Both shields, ships, sails and other equipment were painted in strong colors. Blue in particular, but also red and yellow (gold) were popular among the Norsemen.

Copy of glass beads found in Viking burial mounds. (Photo: alvestein.no / Viking Jewelry)

The discoveries made in the Oseberg and Gokstad burial mounds documents the use on several wooden objects, clothes and tapestries.

During the 1904 Oseberg ship excavation, extremely good preservation conditions made the archaeologists able to see the colors clearly, but sadly, they quickly faded being exposed to light and air.

The Oseberg burial chamber was decorated with colorful tapestries showing dramatic scenes and many of the beautiful wooden objects were painted.

The Vestfold County Municipality in Norway writes about the famous Gokstad ship and Viking Age colors on their homepage:

On the Gokstad ship, shields were attached to the sides. These alternated between yellow and black, first one, then the other.

The same colors were evident on the tent poles found aboard ship. Remains of painted shields also have been in a ship grave at Ballateare on the Isle of Man and Grimstrup in Denmark, and both the Oseberg and Bayeux tapestries depict colored shields.

The three upper strakes of the Ladby Ship also were painted, two of them blue with the middle one in yellow. The Grønhaug ship on Karmøy had triangular areas carved into it, painted black.

There are also found a number of variegated and strong colored glass beads from the time-period – something that should convince archaeologists that the Vikings were colorful people.

Text by: Thor Lanesskog, ThorNews

Was this how the royal hall in Lejre was painted? (Photo: Sagnlandet Lejre)

Recently, Danish archaeologists attended the seminar “Farverige Vikinger” (Colorful Vikings) discussing the colors on a reconstructed royal hall dating back to the Viking Age. The outcome was colorful disagreement and frustration.

In 2009, archaeologist excavated a royal hall in Lejre, Denmark, which turned out to be one of the largest Viking Age buildings ever discovered.

Now, the 60 meters long and oval-shaped longhouse made of oak is under reconstruction and no one with certainty can tell if it was painted, and if so, in which colors.

Although there are found a number of painted Viking Age wooden objects that might reveal the color fashion of the time period, you never can be absolutely certain, says chemist Mads Christian Christensen at the National Museum of Denmark to Danish research portal videnskap.dk.

Whitewashed Theory

Some archaeologists who participated in the seminar put forward a completely different theory when it came to Viking Age colors: The wooden houses, at least the royal halls, were gleaming white.

The rationale is that there are found traces of white chalk in the remains of the royal halls of Tissø and Lejre, and consequently it is likely that Viking houses were whitewashed.

The archaeologist who promoted the theory said that white houses are visible from a long distance, functional as both a status symbol and landmark.

Moreover, indoor and outdoor chalking would both serve as efficient insulation and provide a better indoor climate.

It was also argued that white chalking would provide more light in the dark months of the year.

The theory has some weaknesses, partly because a white-painted house in winter, in a dark and snowy Scandinavia, would “totally disappear”.

Strong Colors

There are numerous references from both archaeological findings and the Norse sagas documenting the Vikings’ use of strong colors:

Both shields, ships, sails and other equipment were painted in strong colors. Blue in particular, but also red and yellow (gold) were popular among the Norsemen.

Copy of glass beads found in Viking burial mounds. (Photo: alvestein.no / Viking Jewelry)

The discoveries made in the Oseberg and Gokstad burial mounds documents the use on several wooden objects, clothes and tapestries.

During the 1904 Oseberg ship excavation, extremely good preservation conditions made the archaeologists able to see the colors clearly, but sadly, they quickly faded being exposed to light and air.

The Oseberg burial chamber was decorated with colorful tapestries showing dramatic scenes and many of the beautiful wooden objects were painted.

The Vestfold County Municipality in Norway writes about the famous Gokstad ship and Viking Age colors on their homepage:

On the Gokstad ship, shields were attached to the sides. These alternated between yellow and black, first one, then the other.

The same colors were evident on the tent poles found aboard ship. Remains of painted shields also have been in a ship grave at Ballateare on the Isle of Man and Grimstrup in Denmark, and both the Oseberg and Bayeux tapestries depict colored shields.

The three upper strakes of the Ladby Ship also were painted, two of them blue with the middle one in yellow. The Grønhaug ship on Karmøy had triangular areas carved into it, painted black.

There are also found a number of variegated and strong colored glass beads from the time-period – something that should convince archaeologists that the Vikings were colorful people.

Text by: Thor Lanesskog, ThorNews

Published on April 29, 2018 23:30

Research: Wealthy Vikings Did Wear Blue Linen Underwear

Thor News

Colorful Vikings: It is known that Vikings did wear colorful clothing of wool, hemp and nettle – but what kind of underwear did they use? (Photo: Tufte Photography / vikingvalley.no)

It is hard to imagine Eric Bloodaxe and other feared Viking kings and chieftains wearing blue linen underwear. However, if the research carried out at the University of Bergen is correct, we should get used to the idea.

Textile fragments from Viking graves in the counties of Rogaland, Sogn og Fjordane and Hordaland in Western Norway have now been analyzed.

Research carried out by textile conservator Hana Lukešová and professor of nanophysics Bodil Holst at the University of Bergen has produced remarkable results: Vikings did use linen underwear, often dyed blue.

The Vikings also used hemp to produce textiles. But in Western Norway, they mostly used linen for clothes, Professor Bodil Holst said to the University of Bergen Independent newspaper På Høyden.

Professor Holst and textile conservator Lukešová have identified plant fibers from textiles found in forty five Viking graves mainly dating back to the 900s.

The two researchers examined tiny fragments from over a hundred different objects with a polarization microscope, something that has provided new and surprising knowledge.

The fact that plant fibers easily dissolve has made the research work extremely challenging.

Clothing worn in direct contact with the skin is very rarely preserved. Outer clothing made of wool, hemp and nettle are more resistant to being buried underground for hundreds of years.

Blue Underwear

In the Viking Age, the flax plant (used to produce linen), hemp and nettle were used for production of clothes while other types of textiles not yet had been introduced in Scandinavia.

The Vikings extracted colors from roots, plants and insects. In addition, there were imported some dyes from Constantinople and other trade hubs. (Photo: fargeneforteller.blogspot.no)