MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 19

June 4, 2018

Legendary Lia Fáil - The Coronation of High Kings in Ancient Ireland

Ancient Origins

Lia Fáil is a stone found at the Inauguration Mound on the Hill of Tara in County Meath, Ireland. Also known as the Coronation Stone of Tara, the Lia Fáil served as a coronation stone for the High Kings of Ireland. According to legend, all of the kings of Ireland up to Muirchertach mac Ercae, 500 AD, were crowned on the stone. Lia Fáil has been translated to mean “stone of destiny.”

The Stone of Destiny, Lia Fáil, found on the Hill of Tara in Ireland. Wikimedia, CC

According to a collection of writings and poems known as the Lebor Gabála Érenn, the semi-divine race of the Tuatha Dé Danann were responsible for bringing the Lia Fáil to Ireland. They traveled to the Northern Isles to learn many skills and magic in the cities of Falias, Gorias, Murias and Findias. They traveled from the Northern Isles to Ireland, bringing a treasure from each of the cities, including the Lia Fáil, the Claíomh Solais or Sword of Victory, the Sleá Bua or Spear of Lugh, and the Coire Dagdae or The Dagda's Cauldron. The Lia Fáil is said to have come from the city of Falias. Many believe that this legend explains how the stone arrived in Ireland.

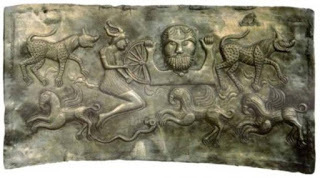

A plate of The Dagda, representing the legendary members of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Public Domain

One traditional tale about the Lia Fáil is that long ago the stone would utter a shout, or would “roar with joy” whenever a king of the true Scottish or Irish race stood or sat on the stone, or placed his feet upon it. Stones that make sounds or speak are a common component in old Irish folk tales. Through the stone’s power the king would be rejuvenated and would enjoy a long reign. According to the legend, Cúchulainn was angered when the stone did not cry out for his protégé, Lugaid Riab nDerg. In retaliation, Cúchulainn struck the stone with his sword, splitting it. From that day forward, the stone never cried out for anyone again, except for Conn of the Hundred Battles. Although Cúchulainn had split the stone in anger, seemingly destroying the powers that allowed it to cry out, the stone roared under Conn, according to the the Lebor Gabála Érenn. However, in another writing, Baile in Scáil, Conn only walks over the stone by accident, as it had been buried after being destroyed by Cúchulainn. Regardless of whether Conn tread upon the stone intentionally, or by accident, it is said it roared for him, and legend held true as Conn enjoyed a long reign as king.

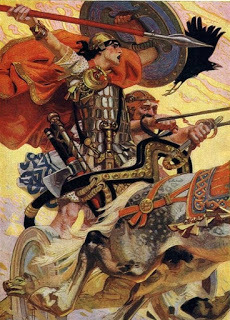

Cúchulainn, is the central character of the Ulster (Ulaid) cycle in the in medieval Irish mythology and literature. According to tale, he split the Stone of Destiny in anger. Public Domain

The Lia Fáil remains erect on the Hill of Tara to this day, a site which has been in use by people since Neolithic era. It is a menhir, or upright standing stone, and many such prehistoric stones were thought to be magical by later cultures. The ancient history of the stone provides a strong symbolic link between the Celtic people of Scotland and Ireland.

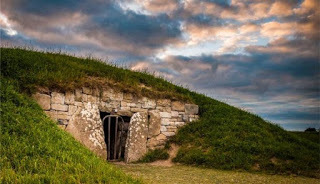

The Hill of Tara is an archaeological complex featuring many ancient monuments, such as the ‘Mound of Hostages’, seen above. In tradition Hill of Tara is known as the seat of the High Kings of Ireland. Wikimedia, CC

The Irish legends surrounding the stone have been retold and reimagined over time, but the stone remains a symbol of the kings who were crowned upon it, and represents the mythical powers which caused the stone to roar with joy when a king stood upon it. Unfortunately, the stone has been vandalized on two occasions. In 2012, it was struck repeatedly with a hammer, leaving eleven areas of damage. In 2014, red and green paint were poured over the stone, covering 50% of the surface. In spite of this damage, the symbolism of the Lia Fáil within Irish culture remains.

Featured image: Lia Fáil at Tara, also known as the Coronation Stone. County Meath, Ireland. S. Jürgensen/ Flickr

By M R Reese

Published on June 04, 2018 23:30

June 3, 2018

How many executions was Henry VIII responsible for?

History Extra

It is impossible to tell for sure, and historians have no definitive number. It is estimated that anywhere from 57,000 to 72,000 people were executed during Henry’s 37 years’ reign, but this is likely to be an exaggeration.

Henry’s break with Papal authority, and his second marriage – which was not sanctioned by the Pope – caused a rift between Henry and certain individuals at court, many of whom he knew well, and in some cases was close to.

Those who either refused to adhere to his Act of Succession or those considered to be heretics were executed, but Henry also executed numerous potential rivals to the throne; two wives and their alleged lovers; leaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace, and his trusted advisor, Thomas Cromwell.

Lauren Mackay is the author of Inside the Tudor Court: Henry VIII and his Six Wives through the Life and Writings of the Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys (Amberley Publishing).

Published on June 03, 2018 23:00

June 2, 2018

What was England’s reaction to the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in 1751?

History Extra

There’s a long-standing belief that when Britain caught up with 16th-century science by adopting the Gregorian calendar in the 18th century, our ancestors rioted over the loss of 11 days of their lives. Well, not quite.

When Pope Gregory XIII had decreed the change in 1582 most western European states, Catholic and Protestant, quickly fell into line with what was simply an accurate astronomical adjustment. Protestant England resisted this papist necromancy for 170 years.

When, at last, legislation was introduced to change the calendar, it wasn’t contentious. The new calendar changed the beginning of the year in England to 1 January (rather than 25 March, as previously; Scotland had already changed). In England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales that year, as well as the colonies, the day following 2 September 1752 would be 14 September 1752.

There’s almost no evidence of riots over the loss of the 11 days, although there was clearly widespread annoyance when the change became a pretext for early demands for payment and for delaying the settlement of bills, wages or debts.

Much of the legend seems to be based on William Hogarth’s 1755 picture An Election Entertainment which shows a placard with the words “Give us our eleven days”. Several reliable authorities claim that many country folk insisted on celebrating Christmas Day on what was now 5 January, and continued to do so for a long time afterwards.

Answered by: Eugene Byrne, author and journalist

Published on June 02, 2018 23:30

June 1, 2018

In Ancient Rome, what was the law of the twelve tables?

History Extra

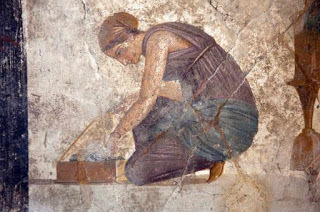

Created around 450 BC, the tables were a code that set out the rights and obligations of the people in areas such as marriage, divorce, burial, inheritance, property and ownership, injury, compensation, debt and slavery.

Key provisions included the establishment of burial grounds outside the limits of the city walls, the control of property if the stakeholder was decreed insane, the continual guardianship of women (passing from father to husband), the treatment of children and of slaves (as property), and the settling of compensation claims for injuries sustained at work.

Although the power of the ruling classes was not really constrained by the plebs, the twelve tables were never repealed – they formed the cornerstone of Roman law until well into the 5th century AD.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication.

Created around 450 BC, the tables were a code that set out the rights and obligations of the people in areas such as marriage, divorce, burial, inheritance, property and ownership, injury, compensation, debt and slavery.

Key provisions included the establishment of burial grounds outside the limits of the city walls, the control of property if the stakeholder was decreed insane, the continual guardianship of women (passing from father to husband), the treatment of children and of slaves (as property), and the settling of compensation claims for injuries sustained at work.

Although the power of the ruling classes was not really constrained by the plebs, the twelve tables were never repealed – they formed the cornerstone of Roman law until well into the 5th century AD.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication.

Published on June 01, 2018 23:00

May 31, 2018

The Legendary Origins of Merlin the Magician

Ancient Origins

Most people today have heard of Merlin the Magician, as his name has been popularized over the centuries and his story has been dramatized in numerous novels, films, and television programs. The powerful wizard is depicted with many magical powers, including the power of shapeshifting and is well-known in mythology as a tutor and mentor to the legendary King Arthur, ultimately guiding him towards becoming the king of Camelot. While these general tales are well-known, Merlin’s initial appearances were only somewhat linked to Arthur. It took many decades of adaptations before Merlin became the wizard of Arthurian legend he is known as today.

Merlin the wizard. Credit: Andy / flickr

It is common belief that Merlin was created as a figure for Arthurian legend. While Merlin the Wizard was a very prominent character in the stories of Camelot, that is not where he originated. Writer Geoffrey of Monmouth is credited with creating Merlin in his 1136 AD work, Historia Regum Britanniae – The History of Kings of Britain. While a large portion of Historia Regum Britanniae is a historical account of the former kings of Britain, Merlin was included as a fictional character (although it is likely that Geoffrey intended for readers to believe he was a figure extracted from long-lost ancient texts). Merlin was paradoxical, as he was both the son of the devil and the servant of God.

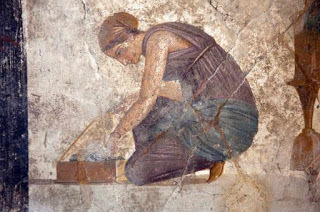

Merlin was created as a combination of several historical and legendary figures. Geoffrey combined stories of North Brythonic prophet and madman, Myrddin Wyllt, and Romano-British war leader, Ambrosius Aurelianus, to create Merlin Ambrosius. Ambrosius was a figure in Nennius' Historia Brittonum. In Historia Brittonum, British king Vortigern wished to erect a tower, but each time he tried it would collapse before completion. He was told that to prevent this, he would have to first sprinkle the ground beneath the tower with the blood of a child who was born without a father. Ambrosius was thought to have been born without a father, so he was brought before Vortigern. Ambrosius explains to Vortigern that the tower could not be supported upon the foundation because two battling dragons lived beneath, representing the Saxons and the Britons. Ambrosius convinced Vortigern that the tower will only stand with Ambrosius as a leader, and Vortigern gave Ambrosius the tower, which is also the kingdom. Geoffrey retells this story with Merlin as the child born without a father, although he retains the character of Ambrosius.

Illumination of a 15th century manuscript of Historia Regum Britanniae showing king of the Britons Vortigern and Ambros waching the fight between two dragons. ( Wikimedia Commons )

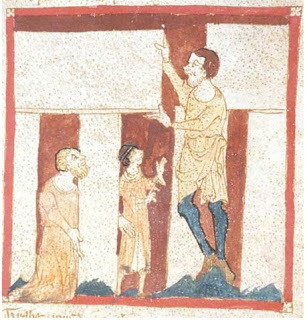

In Geoffrey’s version of the story, he includes a long section containing Merlin’s prophecies, along with two other stories, which led to the inclusion of Merlin into Arthurian legend. These include the tale of Merlin creating Stonehenge as the burial location for Ambrosius, and the story of Uther Pendragon sneaking into Tintagel where he father Arthur with Igraine, his enemy’s wife. This was the extent of Geoffrey’s tales of Merlin. Geoffrey does not include any stories of Merlin acting as a tutor to Arthur, which is how Merlin is most well-known today. Geoffery’s character of Merlin quickly became popular, particularly in Wales, and from there the tales were adapted, eventually leading to Merlin’s role as Arthur’s tutor.

A giant helps Merlin build Stonehenge. From a manuscript of the Roman de Brut by Wace

( Wikimedia Commons )

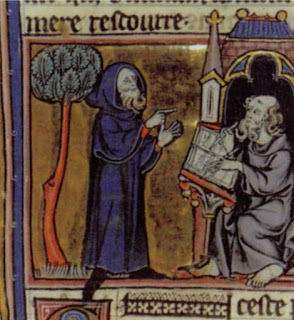

Many years after Geoffrey’s Historia Regum Britanniae, Robert de Boron composed a poem called Merlin. Boron’s Merlin has the same origins as Geoffrey’s creation, but Boron places special emphasis on Merlin’s shapeshifting powers, connection to the Holy Grail, and his jokester personality. Boron also introduces Blaise, Merlin’s master. Boron’s poem was eventually re-written in prose as Estoire de Merlin, which also places much focus upon Merlin’s shapeshifting. Over the years, Merlin was interspersed through the tales of Arthurian legend. Some writings placed much focus upon Merlin as Arthur’s mentor, while others did not mention Merlin at all. In some tales Merlin was viewed as an evil figure who did no good in his life, while in others he was viewed favorably as Arthur’s teacher and mentor.

Merlin reciting his poem in a 13th-century illustration for ‘Merlin’ by Robert de Boron ( Wikimedia Commons )

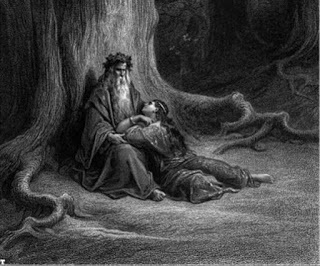

Eventually, from the various tales emerged Merlin’s downfall, at the hands of Niviane (Vivien), the king of Northumberland’s daughter. Arthur convinces Niviane to stay in his castle, under Merlin’s encouragement. Merlin falls in love with Niviane. However, Niviane fears Merlin will use his magical powers to take advantage of her. She swears that she will never fall in love with him, unless he teaches her all of the magic he knows. Merlin agrees. Merlin and Niviane depart to return to Northumberland, when they are called back to assist King Arthur. As they are returning, they stop to stay in a stone chamber, where two lovers once died and were buried together. When Merlin falls asleep, Niviane places him under a spell, and traps him within the stone tomb, where he dies. Merlin had never realized that his desire for Niviane, and his willingness to teach her his magical ways, would eventually lead to his untimely death.

Merlin and Vivien dated 1867 by Gustave Dore ( Wikimedia Commons )

From Merlin’s inception through the writings of Geoffrey, the wizard appeared in many subsequent tales, stories, and poems. Today, Merlin is most well-known for being the wizard who tutored and taught the young Arthur, before he grew to become the King of Camelot. It was under Merlin’s counsel that Arthur became the king that he was. While this legend continues on today, it is interesting to see the many variations of Merlin, from an evil wizard, to a shapeshifter, to one who met his downfall from teaching his powers to the woman he loved. This powerful and versatile character caught the attention of many people centuries ago, and continues to play a prominent role in today’s storytelling.

By M R Reese

Published on May 31, 2018 23:30

Norse-Era Jewelry: Revealing an Intricate Cultural History of the Vikings

Ancient Origins

When you think of ancient Vikings, the first thing that pops into your mind is probably not jewelry, right? The picture that forms in the mind of most people is one of savages with long sharp spears, swords, and heavy shields attacking coastal communities. However, you will be pleased to know that Norse people of old also made beautiful and intricate ornaments; bracelets, rings, necklaces, etc., out of a variety of materials including bronze, iron, gold, silver, amber, and resin. Early on in the Viking era, which is about 800 AD, these ornaments were simple, but as time went by, the pieces became more detailed and sophisticated.

Group shot of the Silverdale Hoard finds. Image by Ian Richardson. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Viking Use of Jewelry

By occupation, Vikings were farmers and, occasionally, they were warriors. Both the men and women of the Viking community wore a wide array of jewelry, shiny objects that added some glamour to their seemingly dark world. Note, Norse ornaments had a secondary purpose, they were also used as currency in trade, which is probably the reason why the Vikings preferred using precious metals to craft their jewelry. If an ornament was too large for the subject matter of transaction, the piece would be broken into smaller portions that would suit that particular undertaking. If you think about it, the Vikings used their jewelry like we use modern-day wallets.

However, not all Viking ornaments were metallic; the Norsemen also created beautiful ornaments using beads and precious rocks/stones. Nevertheless, it was rare for the Vikings to inset stones in their jewelry even though this art form had been applied before the Viking age.

Below are some interesting facts about Viking jewelry that’ll give you clearer picture of what the Nordic ornamental culture was like.

A hinged silver strap ( Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland ).

Necklaces/Neck-Rings

The Vikings crafted their necklaces from a variety of items including precious metals such as silver and gold, natural fiber, and iron wires of various lengths and sizes. The necklaces would normally be accompanied by pendants made from glass beads, precious stones, resin, amber (from the Baltic sea), and small metallic charms. However, the most common material for necklace pendants was glass, which would be mass produced for this purpose. The pendants on the necklaces were often souvenirs, gifts, or Nordic religious symbols that held meaning to the wearer.

The archeological evidence of Vikings wearing necklaces is more prevalent in comparison to the evidence on neck-rings. Neck-rings that have been discovered across Europe were made of silver, bronze, or gold. Note that most neck-rings that have been discovered were in hoards and not in grave site. Therefore, there is no conclusive evidence regarding which gender wore them. However, most historians believe that neck-rings were worn by both genders as a display of wealth and as a form of currency in commercial transactions. They were designed and crafted in standard units of weight in order to make the assessment of value more accurate. As mentioned above, a piece would be cut from the neck-ring depending on the amount necessary to conclude a commercial transaction.

The Silverdale Hoard, Lancaster Museum. Neck-rings, arm-rings and necklace. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Pendants/Amulets

When it comes to Viking jewelry, the word pendant represents a broad category of items; from Mjolnir pendants, Valknut pendants, Yggdrasil pendants, and more. As much as the ancient Norsemen used a number of distinct pendants , Thor’s hammer appears to be the most frequently worn of them all. Other examples include miniature weapons such as axes and arrow heads, perforated coins, the tree of life, crosses, and the Valknut symbols . However, these amulets have been found in very few graves, suggesting that they were not commonly worn.

You may also be wondering why a pagan community would be wearing miniature crosses. Even at the height of the Viking era, Christian missionaries were adamant in converting non-believers and consequently some Norsemen adopted this new religion, forming a hybrid system of belief. Note, however, cross pendants were the rarest archeological pendant findings, which suggests that only a few Vikings accepted Christianity.

Left to right: Thor's hammer from Bredsättra: A 4.6 cm gold-plated silver Mjolnir pendant from Bredsättra parish, Runsten hundred, Borgholm municipality, Öland, Kalmar county, Sweden ( Public Domain ). Hammer pendant from Rømersdal, Bornholm ( CC BY-SA 3.0 ). A copy of the Thor's hammer pendant from Skåne ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Beads

Viking bead ornaments were typically made of amber or glass and were some of the most common additions on necklaces. In today’s world these items are relatively cheap and widely used, but archeological evidence from Viking grave sites suggests that these ornaments were rare and not worn by many. Moreover, even the Viking ornaments with beads only had one, two, or three of them, either worn alone or with an additional pendant such as Thor’s hammer, Mjolnir. Finding more than three beads on a necklace was extremely rare, which suggests that they were precious and rare, and perhaps symbolized one’s wealth and status in society.

Additionally, seeing as archeological findings usually found only 1 to 3 beads on necklaces, it is quite possible that the number of beads a person wore represented more than just wealth and societal status. It is possible that they signified a certain level of achievement or age. A majority of beads found in archeological sites were made of glass; other materials such as jet and amber have also been discovered but are rarer to come by.

Brooches

Brooches were very popular in Viking culture and were an everyday essential used for holding clothes in place. Brooches came in a number of styles with the main ones being the Penannular Brooches and Oval Brooches .

Example of a Celtic Penannular brooch, Museum of Scotland. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The Penannular brooch was exclusively worn by Viking men and was adopted by Vikings from Scottish and Irish settlers; the trend later caught on in Russia and Scandinavia. Brooches would be fastened on the wearer’s right shoulder with the pin facing upward, which left the sword-arm free. The Oval brooch, on the other hand, was typically worn by Viking women. Oval brooches were used to fasten dresses, aprons, and cloaks and were more detailed and ornate in comparison to penannular brooches. A single brooch would be worn on the shoulder to fasten the wearer’s dress, along with a chain of colored beads for added visual appeal. Oval brooches are believed to have gone out of fashion at around 1000 AD and were replaced by more fanciful designs of brooches.

Viking oval brooch. Museum of History, Oslo, Norway. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Rings

Rings, like in most other cultures, were worn around the finger and were extremely popular among the Vikings. There have been numerous findings of finger rings in Viking grave sites; the rings typically had an uneven width, with most of them being open ended, possibly in order to allow them to fit on different sized fingers with minimal effort. Note, however, finger rings only became popular to the Vikings in the late ages of the Viking-era.

Earrings

This was the least common form of Viking jewelry . In fact, earrings did not exist in Viking material culture until they were found in hoards amongst other types of jewelry. Nordic earrings were quite intricate and, in contrast to modern-day earrings, they would be worn over the entire ear as opposed to hanging from the earlobe. Historians have suggested that Viking earrings were of Slavic in origin and not an original concept forged by the Norsemen.

Arm Rings/Arm Bands

Arm rings/arm bands or bracelets were extremely popular in Viking culture and, like neck-rings, arm bands served a dual purpose; ornamental and commercial. Some arm rings were very intricate and detailed, having been crafted from precious metals such as gold and silver. Arm rings represented societal standing and were a display of wealth.

Nested bracelet from the Silverdale Hoard. Image by Ian Richardson. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Arm bands came in different shapes and designs. Some were spiral in design, wrapping themselves around the arm several times, giving them a firm grip around the arm, and making it easier for the wearer to tear a piece of the end off during a commercial transaction. Other arm rings were only long enough to wrap around three-quarters of the arm; these were the bands most commonly used as currency because they were plain and flat, which made them easier to break apart whenever needed.

In Summary

Vikings enjoyed fashion and the allure of precious metals and they strived to incorporate this into their day-to-day lives by crafting beautiful ornate ornaments as described above. However, unlike most cultures, jewelry pieces in Viking culture typically had a dual purpose, being used both for aesthetic appeal and as a form of currency, much like carrying money in your wallet or purse.

Evidently, Vikings were not the barbarians most people assume they were, they were an organized, sophisticated people with a rich culture that has more in common with most other cultures of their era.

Top image: Jewelry found in a hoard in Galloway, Scotland in 2014. Clockwise from top left: A silver disk brooch decorated with intertwining snakes or serpents ( Historic Scotland ), a gold, bird-shaped object which may have been a decorative pin or a manuscript pointer ( Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland ), one of the many arm rings with a runic inscription ( Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland ), a large glass bead ( Santiago Arribas Pena )

By Jessica Zhang

When you think of ancient Vikings, the first thing that pops into your mind is probably not jewelry, right? The picture that forms in the mind of most people is one of savages with long sharp spears, swords, and heavy shields attacking coastal communities. However, you will be pleased to know that Norse people of old also made beautiful and intricate ornaments; bracelets, rings, necklaces, etc., out of a variety of materials including bronze, iron, gold, silver, amber, and resin. Early on in the Viking era, which is about 800 AD, these ornaments were simple, but as time went by, the pieces became more detailed and sophisticated.

Group shot of the Silverdale Hoard finds. Image by Ian Richardson. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Viking Use of Jewelry

By occupation, Vikings were farmers and, occasionally, they were warriors. Both the men and women of the Viking community wore a wide array of jewelry, shiny objects that added some glamour to their seemingly dark world. Note, Norse ornaments had a secondary purpose, they were also used as currency in trade, which is probably the reason why the Vikings preferred using precious metals to craft their jewelry. If an ornament was too large for the subject matter of transaction, the piece would be broken into smaller portions that would suit that particular undertaking. If you think about it, the Vikings used their jewelry like we use modern-day wallets.

However, not all Viking ornaments were metallic; the Norsemen also created beautiful ornaments using beads and precious rocks/stones. Nevertheless, it was rare for the Vikings to inset stones in their jewelry even though this art form had been applied before the Viking age.

Below are some interesting facts about Viking jewelry that’ll give you clearer picture of what the Nordic ornamental culture was like.

A hinged silver strap ( Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland ).

Necklaces/Neck-Rings

The Vikings crafted their necklaces from a variety of items including precious metals such as silver and gold, natural fiber, and iron wires of various lengths and sizes. The necklaces would normally be accompanied by pendants made from glass beads, precious stones, resin, amber (from the Baltic sea), and small metallic charms. However, the most common material for necklace pendants was glass, which would be mass produced for this purpose. The pendants on the necklaces were often souvenirs, gifts, or Nordic religious symbols that held meaning to the wearer.

The archeological evidence of Vikings wearing necklaces is more prevalent in comparison to the evidence on neck-rings. Neck-rings that have been discovered across Europe were made of silver, bronze, or gold. Note that most neck-rings that have been discovered were in hoards and not in grave site. Therefore, there is no conclusive evidence regarding which gender wore them. However, most historians believe that neck-rings were worn by both genders as a display of wealth and as a form of currency in commercial transactions. They were designed and crafted in standard units of weight in order to make the assessment of value more accurate. As mentioned above, a piece would be cut from the neck-ring depending on the amount necessary to conclude a commercial transaction.

The Silverdale Hoard, Lancaster Museum. Neck-rings, arm-rings and necklace. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Pendants/Amulets

When it comes to Viking jewelry, the word pendant represents a broad category of items; from Mjolnir pendants, Valknut pendants, Yggdrasil pendants, and more. As much as the ancient Norsemen used a number of distinct pendants , Thor’s hammer appears to be the most frequently worn of them all. Other examples include miniature weapons such as axes and arrow heads, perforated coins, the tree of life, crosses, and the Valknut symbols . However, these amulets have been found in very few graves, suggesting that they were not commonly worn.

You may also be wondering why a pagan community would be wearing miniature crosses. Even at the height of the Viking era, Christian missionaries were adamant in converting non-believers and consequently some Norsemen adopted this new religion, forming a hybrid system of belief. Note, however, cross pendants were the rarest archeological pendant findings, which suggests that only a few Vikings accepted Christianity.

Left to right: Thor's hammer from Bredsättra: A 4.6 cm gold-plated silver Mjolnir pendant from Bredsättra parish, Runsten hundred, Borgholm municipality, Öland, Kalmar county, Sweden ( Public Domain ). Hammer pendant from Rømersdal, Bornholm ( CC BY-SA 3.0 ). A copy of the Thor's hammer pendant from Skåne ( CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Beads

Viking bead ornaments were typically made of amber or glass and were some of the most common additions on necklaces. In today’s world these items are relatively cheap and widely used, but archeological evidence from Viking grave sites suggests that these ornaments were rare and not worn by many. Moreover, even the Viking ornaments with beads only had one, two, or three of them, either worn alone or with an additional pendant such as Thor’s hammer, Mjolnir. Finding more than three beads on a necklace was extremely rare, which suggests that they were precious and rare, and perhaps symbolized one’s wealth and status in society.

Additionally, seeing as archeological findings usually found only 1 to 3 beads on necklaces, it is quite possible that the number of beads a person wore represented more than just wealth and societal status. It is possible that they signified a certain level of achievement or age. A majority of beads found in archeological sites were made of glass; other materials such as jet and amber have also been discovered but are rarer to come by.

Brooches

Brooches were very popular in Viking culture and were an everyday essential used for holding clothes in place. Brooches came in a number of styles with the main ones being the Penannular Brooches and Oval Brooches .

Example of a Celtic Penannular brooch, Museum of Scotland. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The Penannular brooch was exclusively worn by Viking men and was adopted by Vikings from Scottish and Irish settlers; the trend later caught on in Russia and Scandinavia. Brooches would be fastened on the wearer’s right shoulder with the pin facing upward, which left the sword-arm free. The Oval brooch, on the other hand, was typically worn by Viking women. Oval brooches were used to fasten dresses, aprons, and cloaks and were more detailed and ornate in comparison to penannular brooches. A single brooch would be worn on the shoulder to fasten the wearer’s dress, along with a chain of colored beads for added visual appeal. Oval brooches are believed to have gone out of fashion at around 1000 AD and were replaced by more fanciful designs of brooches.

Viking oval brooch. Museum of History, Oslo, Norway. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Rings

Rings, like in most other cultures, were worn around the finger and were extremely popular among the Vikings. There have been numerous findings of finger rings in Viking grave sites; the rings typically had an uneven width, with most of them being open ended, possibly in order to allow them to fit on different sized fingers with minimal effort. Note, however, finger rings only became popular to the Vikings in the late ages of the Viking-era.

Earrings

This was the least common form of Viking jewelry . In fact, earrings did not exist in Viking material culture until they were found in hoards amongst other types of jewelry. Nordic earrings were quite intricate and, in contrast to modern-day earrings, they would be worn over the entire ear as opposed to hanging from the earlobe. Historians have suggested that Viking earrings were of Slavic in origin and not an original concept forged by the Norsemen.

Arm Rings/Arm Bands

Arm rings/arm bands or bracelets were extremely popular in Viking culture and, like neck-rings, arm bands served a dual purpose; ornamental and commercial. Some arm rings were very intricate and detailed, having been crafted from precious metals such as gold and silver. Arm rings represented societal standing and were a display of wealth.

Nested bracelet from the Silverdale Hoard. Image by Ian Richardson. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Arm bands came in different shapes and designs. Some were spiral in design, wrapping themselves around the arm several times, giving them a firm grip around the arm, and making it easier for the wearer to tear a piece of the end off during a commercial transaction. Other arm rings were only long enough to wrap around three-quarters of the arm; these were the bands most commonly used as currency because they were plain and flat, which made them easier to break apart whenever needed.

In Summary

Vikings enjoyed fashion and the allure of precious metals and they strived to incorporate this into their day-to-day lives by crafting beautiful ornate ornaments as described above. However, unlike most cultures, jewelry pieces in Viking culture typically had a dual purpose, being used both for aesthetic appeal and as a form of currency, much like carrying money in your wallet or purse.

Evidently, Vikings were not the barbarians most people assume they were, they were an organized, sophisticated people with a rich culture that has more in common with most other cultures of their era.

Top image: Jewelry found in a hoard in Galloway, Scotland in 2014. Clockwise from top left: A silver disk brooch decorated with intertwining snakes or serpents ( Historic Scotland ), a gold, bird-shaped object which may have been a decorative pin or a manuscript pointer ( Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland ), one of the many arm rings with a runic inscription ( Robert Clark, National Geographic / Historic Environment Scotland ), a large glass bead ( Santiago Arribas Pena )

By Jessica Zhang

Published on May 31, 2018 00:00

May 30, 2018

2,000-Year-Old Remains of Horse Killed by Pompeii Volcano Found in Tomb Raider Tunnel

Ancient Origins

Donkeys, pigs, and dogs have all been found amongst the ruins of Pompeii, but the remains of a carbonized horse are the first example archaeologists have come across of that animal. While the discovery is great, the way it was found is unsettling. T

he Local.it reports the horse was found in a stable, complete with a trough, beside a large Roman villa. Unfortunately, archaeologists were not the first to make the discovery – tomb raiders are responsible for unearthing the horse. Nonetheless, Massimo Osanna, the director of the Pompeii site, calls the horse an "extraordinary" find.

Authorities found the looters had dug a 60 meter (196.85 ft.) long network of tunnels under the villa, to search for frescoes and other precious artifacts. Laser scanners show the tunnels measure just 60 cm (23.62 inches) wide, according to Independent.ie. Steps have been taken to find the looters and archaeologists have begun excavating the area properly to try to avoid further destruction.

Traces of an iron and bronze harness were located beside the horse’s head, which archaeologists believe suggests the animal was probably a parade horse that was specially bred to fulfill that action and very expensive. The Telegraph mentions there is also the possibility that the animal was a prized racing horse.

The remains of the horse were uncovered by looters. (Antonio Ferrara and Riccardo Siano )

The recently discovered horse measures 150 centimeters (59.06 inches) tall at the withers, somewhat short if compared to a modern horse, but experts say it would have been a rather large adult horse in ancient Pompeii. It was carbonized following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD and no skeleton or flesh remains on its body. However, the form has been preserved through a technique which experts have been using to preserve casts of Pompeii’s human victims . The procedure involves injecting the empty body cavity with liquid plaster.

The Local.it says this is the first time archaeologists have found the complete outline of a horse at Pompeii. Experts were able to distinguish it as a horse, as opposed to a donkey, because of the left ear imprint which marks the ground under the animal’s head.

The imprint of the horse's left ear. ( Parco Archeologico di Pompei )

A tomb dating to a later period was also found at the villa. It contained a man who died when he was 40-55 years old and Osanna says , "It shows that even after the eruption, people continued to live and to farm in Pompeii, on top of the layer of ash which destroyed the city." Amphora shards, fragments of kitchen utensils, and part of a wooden bed were also found during excavations.

This is the second major discovery to be reported from Pompeii in the last few weeks. On April 25, Osanna announced that archaeologists had found the skeleton of a child who died during Vesuvius’ eruption . The seven or eight-year-old sought shelter from the volcanic ash, gas, and pumice by crouching inside a public thermal bath.

The child’s skeleton was found in a crouching position in the bath complex of the town. ( Parco Archeologico de Pompeii )

Top Image: The remains of an ancient Roman horse have been found in Pompeii. Source: Parco Archeologico di Pompei

By Alicia McDermott

Published on May 30, 2018 00:00

May 28, 2018

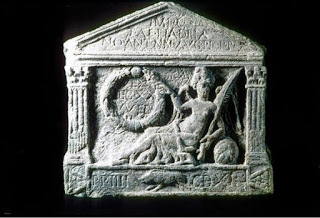

An Eagle with a Blood-soaked Beak: Antonine Wall Carvings Warned Scottish Tribes to Obey, Or Else!

Ancient Origins

The Romans were not afraid of getting graphic if it would incite fear and compliance in their enemies. X-rays and laser analysis of Roman carvings reveal that disturbing images of captive and defeated locals were used as a warning against Scottish tribes standing up against the invading army.

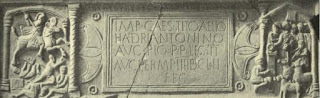

Today the Antonine Wall carvings may not seem especially gruesome at first glance, but a Glasgow University archaeologist has been analyzing the Roman reliefs for months and says the scenes depicted on them would have been far more vivid, and threatening, when they were created around 142 AD. As the study archaeologist, Dr. Louisa Campbell, told The Herald :

The public today sees the slabs in bland greys, but to the people of the time they would have been brightly coloured in yellows and different shades of red. On one hand they were for the soldiers to show their dedication to the Emperor, as they say the work was carried out in his name. But for the local people they would have served as reminders of the power of Rome. They were part of the act of subjugation and the projection of power. And they were a warning not to go up against Rome.

Dr. Louisa Campbell with the Summerston distance stone at The Hunterian Museum. ( University of Glasgow )

Campbell’s work shows that originally blood red, bright yellow, and brilliant white paints were used to catch the eye of a local. Then the warning message was made: even if the person could not read the inscriptions, once they saw the representations of local defeated brethren covered in blood they may have thought twice before rebelling against the Romans…or at least that’s what the Legion members would have hoped. “The scenes depicted by the iconography demonstrate the power and might of Rome in a highly graphic manner,” Campbell told Live Science.

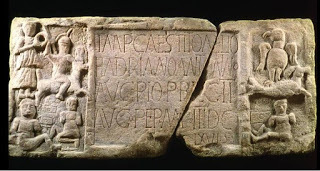

Around 20 stone slabs bearing inscriptions of distance covered, honors to authority, and images have survived until today. And several of the carvings were rather grisly; Dr. Campbell described some of the scenes :

On the figures of the natives there splashes of blood on their cheeks, chest and thighs. On another slab there's a decapitated head which is dripping bright red blood. These people are fresh from a battle with Rome, and these wounds are the remains of that battle. That's a very stark message for anyone who would have seen them when they were freshly coloured.

The Bridgeness Stone, a Roman distance Stone from the Antonine wall. (Public Domain ) Note the decapitated man at the bottom of the left scene – his neck was once “dripping” with blood red paint.

Dr. Campbell explained the significance of symbol of the eagle with the blood-soaked beak, “I would suggest the red on the beak of the eagle (the symbol of Rome and her legions) symbolizes Rome feasting off the flesh of her enemies.”

How frightened the local people were of the Romans based on these images is a matter of debate, but Dr. Campbell believes “These sculptures are propaganda tools used by Rome to demonstrate their power over these and other indigenous groups, it helps the Empire control their frontiers and it has different meanings to different audiences.”

The Herald reports the researcher’s next goal is to see digital reconstructions of the stone slabs as they would have appeared when they were painted.

Victory depicted on a distance Slab by the Twentieth Legion, found in Clydebank. ( The Antonine Wall )

The Antonine Wall was a 3-meter (10 ft.) turf wall topped with a wooden palisade built by Roman soldiers in the mid-2nd century AD. The wall ran almost 40 miles (64 km) from east to west and its ruins show it stretched from the Firth of Forth (north of Edinburgh) to the Firth of Clyde (a few miles west of Glasgow). It was intended to extend Roman control over the lands north of Hadrian's Wall.

The wall’s construction was ordered by Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius and it began in 142 AD. The work was completed in about 12 years. Despite their effort, the Roman Legions which had built the wall retreated back to Hadrian’s wall just eight years after finishing construction.

Relic of Antonine Wall in Bearsden cemetery. (Chris Upson/ CC BY SA 2.0 )

Top Image: The Summerstone slab, found near Bearsden. Source: The Antonine Wall

By Alicia McDermott

Published on May 28, 2018 23:00

May 27, 2018

Memorial Day: 7 Historical Facts About the Holiday

Live Science

While many look forward to Memorial Day as a chance to barbecue, spend time with family and hop in the car for a long weekend getaway, the holiday's origin is anchored in much more somber circumstances. From its roots as a Civil War commemoration to the Confederate version of the holiday still celebrated in the South, here are seven interesting facts about Memorial Day's history

1. Decoration Day

Though Memorial Day is a staple of the holiday calendar now, it wasn't always called that. During the Civil War, people decorated the graves of fallen soldiers on what became known at the time as "Decoration Day." Still, nobody knows for sure when and where the first Decoration Day actually occurred, with several cities angling for the title. A ceremony at the cemetery at Gettysburg honored the dead in 1863, while women in Boalsburg, Pennsylvania, placed flowers on the graves of fallen soldiers on Independence Day in 1864. Confederate women in South Carolina were honoring their dead with grave flowers as early as 1861. Other places that claim to have hosted the first Decoration Day are Savanna, Georgia, and Warrenton, Virginia

2. National observance

A century after the first Decoration Day celebration, President Lyndon B. Johnson settled the debate — in the official record at least — when he signed a proclamation decreeing that the holiday got its start 100 years earlier in Waterloo, New York. In Johnson's rendering, a Waterloo resident named Henry Welles decided to memorialize local fallen soldiers by decorating their graves at three different cemeteries in the area. A local war hero described the commemoration to Gen. John Alexander Logan, who made it a national day of remembrance first observed on May 30, 1868.

3. First speech

The first Memorial Day speech was given by James A. Garfield, then an Ohio congressman, at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia in 1868. (The day was still known as Decoration Day.) Garfield, a former Union general, would go on to become the 20th president of the United States, though he would die from an assassin's bullet just 200 days into his first term. [8 Most Famous Assassinations in History]

4. Separate holidays

The Union lost about 360,000 soldiers during the war, compared to the 260,000 who died in the South. For decades, the South shunned the Union's Memorial Day celebrations, instead observing its own separate holiday to honor Confederate war dead till after World War I, when Memorial Day was expanded to remember the dead from all United States conflicts. Several southern states still celebrate Confederate Memorial Day, although the holiday occurs on April 26, May 10, May 30 or June 2, depending on the state. The holiday is not without controversy, however, with some arguing that it glorifies a part of American history dedicated to preserving slavery.

5. Unofficial holiday

The holiday's Decoration Day moniker lingered until 1882, but the day wasn't an official holiday until 1967. The holiday was held on May 30 until 1971, when Congress fixed the date as the last Monday in May. The holiday was officially renamed Memorial Day in 1967, when President Johnson signed legislation to that effect.

6. Many casualties

More than 150 years later, the Civil War remains the United States' deadliest conflict. More than 620,000 people died during the war. Most of the casualties occurred as a result of disease, rather than as a direct result of injuries. The second deadliest conflict was World War II, in which more than 400,000 American soldiers lost their lives.

7. Weekend plans

Memorial Day weekend getaways have become an American tradition in their own right. According to the American Automobile Association, more than 36 million people will hit the roads this holiday weekend and drive more than 50 miles (80 kilometers) to another destination. Grilling may not have been part of the original Memorial Day celebrations, but it's now a fixture of the holiday. Memorial Day is now the second-most popular holiday (after the Fourth of July) for a sun-baked barbecue: 53 percent of people grill on the holiday, according to the Hearth,

Published on May 27, 2018 23:30

May 26, 2018

No Atomic Blast. Fire Melted the Stones of Iron Age Forts Say Investigators

Ancient Origins

In Scotland, archaeologists believe that they have solved the mystery of an Iron Age fort in which stones had melted in a process termed vitrification. The team of experts studied the vitrified fort, known as Dun Deardail, in the Highlands, near Ben Nevis and have concluded that they can explain how its stones became molten and melted.

Vitrified Forts

Dun Deardail has been dated to have been built around 500 BC, based on carbon testing. It was occupied by the Celts and later by the fierce Picts who used it as a fortress. The outline of the original fort can still be seen today as grassy embankments and it sits a-top a hill, that once had strategic significance in the area. It is perhaps one of the best known of the vitrified forts in Scotland, along with Ord Hill, and has fascinated people for centuries. Many people visit the spectacular site set in stunning landscape every year.

Dun Deardail. At the top of this hill is the vitrified Iron Age fort. ( CC BY SA 2.0 )

There are many similar vitrified forts in France and Ireland. It is estimated by the National Geographic that there are about 70 vitrified forts in Scotland and 200 in total in Europe. Scientists believe that to vitrify stone slabs that a heat of 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit or 1,100 degrees Celsius , is required. The question as to how Iron Age people managed to ignite such conflagrations with their crude technologies and limited capabilities has only added to the mystery.

The experts from the Forest Enterprise Scotland, working with Stirling University and local volunteers, believe that they have solved the enigma, reports the Scotsman. They believe that a large-scale wooden structure over the stone walls was set alight and the blaze reached such a temperature that it burned the stones. Have the team solved the mystery of the vitrified forts?

Dun Carloway Broch, Lewis, Scotland. Another fort that has areas of vitrification. ( Public Domain )

Solving the Mystery

In order to solve the riddle of the vitrification of forts in Scotland and elsewhere in Europe, a series of investigations have been carried out since at least the 1930s. These tried to duplicate the conditions that would have led to stone vitrifying. None of their results were especially convincing and the reasons for the melting of stone forts continued to be a mystery. The failure to provide a satisfactory theory encouraged all kinds of wild speculation. For example, the popular author, Arthur C Clark argued that the stones were melted and fused by some Iron Age superweapon if not an early atomic bomb.

Now the team led by an archaeologist from the University of Stirling have offered what they believe is the most plausible explanation for the phenomenon of the vitrification of stone citadels. The study has shown that a timber superstructure, which included ramparts and towers, was set alight and the resulting blaze heated the stones. The fire was so intense that is was able to melt stones because of the anaerobic environment that developed as the flames burned down into the stones. The absence of oxygen in the anaerobic conditions, made the fire much more intense and allowed it to reach the temperatures that would have burned the slabs until they melted and fused

Fused stones. This was once part of a wall to the original hill fort at Dunnideer which gave the hill its name. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

The team is not only excited by the potential discovery of the cause of the vitrification process but also by the insights that it offers into the nature of Iron Age forts and society. The theory can help us to visualize what these forts looked like. They were impressive bastons with stone walls and according to Matt Ritchie, archaeologist with Forestry Enterprise Scotland they had ‘ roofed rampart walls many metres high’ . He also believes that the extensive wooden structures were used to store the precious food supply of the community.

It seems that the archaeologists and the team of volunteers have explained one of the most perplexing mysteries from the Iron Age. They have offered a rational and plausible explanation for the vitrification of forts without the need for far-fetched theories. However, according to Ritchie ‘ of course the mystery of why the forts were burned remains unresolved’ . It has been speculated that they were burned during war, as part of a religious ceremony or to mark the death of a monarch.

Top image: Dunnideer Castle, built on the site of a hillfort with a remaining vitrified rampart. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

By Ed Whelan

In Scotland, archaeologists believe that they have solved the mystery of an Iron Age fort in which stones had melted in a process termed vitrification. The team of experts studied the vitrified fort, known as Dun Deardail, in the Highlands, near Ben Nevis and have concluded that they can explain how its stones became molten and melted.

Vitrified Forts

Dun Deardail has been dated to have been built around 500 BC, based on carbon testing. It was occupied by the Celts and later by the fierce Picts who used it as a fortress. The outline of the original fort can still be seen today as grassy embankments and it sits a-top a hill, that once had strategic significance in the area. It is perhaps one of the best known of the vitrified forts in Scotland, along with Ord Hill, and has fascinated people for centuries. Many people visit the spectacular site set in stunning landscape every year.

Dun Deardail. At the top of this hill is the vitrified Iron Age fort. ( CC BY SA 2.0 )

There are many similar vitrified forts in France and Ireland. It is estimated by the National Geographic that there are about 70 vitrified forts in Scotland and 200 in total in Europe. Scientists believe that to vitrify stone slabs that a heat of 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit or 1,100 degrees Celsius , is required. The question as to how Iron Age people managed to ignite such conflagrations with their crude technologies and limited capabilities has only added to the mystery.

The experts from the Forest Enterprise Scotland, working with Stirling University and local volunteers, believe that they have solved the enigma, reports the Scotsman. They believe that a large-scale wooden structure over the stone walls was set alight and the blaze reached such a temperature that it burned the stones. Have the team solved the mystery of the vitrified forts?

Dun Carloway Broch, Lewis, Scotland. Another fort that has areas of vitrification. ( Public Domain )

Solving the Mystery

In order to solve the riddle of the vitrification of forts in Scotland and elsewhere in Europe, a series of investigations have been carried out since at least the 1930s. These tried to duplicate the conditions that would have led to stone vitrifying. None of their results were especially convincing and the reasons for the melting of stone forts continued to be a mystery. The failure to provide a satisfactory theory encouraged all kinds of wild speculation. For example, the popular author, Arthur C Clark argued that the stones were melted and fused by some Iron Age superweapon if not an early atomic bomb.

Now the team led by an archaeologist from the University of Stirling have offered what they believe is the most plausible explanation for the phenomenon of the vitrification of stone citadels. The study has shown that a timber superstructure, which included ramparts and towers, was set alight and the resulting blaze heated the stones. The fire was so intense that is was able to melt stones because of the anaerobic environment that developed as the flames burned down into the stones. The absence of oxygen in the anaerobic conditions, made the fire much more intense and allowed it to reach the temperatures that would have burned the slabs until they melted and fused

Fused stones. This was once part of a wall to the original hill fort at Dunnideer which gave the hill its name. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

The team is not only excited by the potential discovery of the cause of the vitrification process but also by the insights that it offers into the nature of Iron Age forts and society. The theory can help us to visualize what these forts looked like. They were impressive bastons with stone walls and according to Matt Ritchie, archaeologist with Forestry Enterprise Scotland they had ‘ roofed rampart walls many metres high’ . He also believes that the extensive wooden structures were used to store the precious food supply of the community.

It seems that the archaeologists and the team of volunteers have explained one of the most perplexing mysteries from the Iron Age. They have offered a rational and plausible explanation for the vitrification of forts without the need for far-fetched theories. However, according to Ritchie ‘ of course the mystery of why the forts were burned remains unresolved’ . It has been speculated that they were burned during war, as part of a religious ceremony or to mark the death of a monarch.

Top image: Dunnideer Castle, built on the site of a hillfort with a remaining vitrified rampart. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

By Ed Whelan

Published on May 26, 2018 23:30