MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 20

May 25, 2018

Tintagel Castle and The Legendary Conception of King Arthur

Ancient Origins

Tintagel Castle is a castle located on Tintagel Island, a peninsula connected to the North Cornwall coast in England by a narrow strip of land. This castle is said to have been an important stronghold from around the end of Roman rule in Britain, i.e. the 4th century AD, or the 5th century AD until the end of the 7th century AD. Tintagel Castle is perhaps best known for the claim that it was the place where the legendary King Arthur was conceived.

The site where Tintagel Castle stands today is likely to have been occupied during the Roman era, as artifacts dating to this period have been found on the peninsula. Having said that, as structures dating to the Roman period have yet to be discovered, it is not entirely clear if Tintagel Island had been occupied during the Roman period.

The ruins of the upper mainland courtyards of Tintagel Castle, Cornwall. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

It may be said with more certainty that the site was occupied between the end of the Roman period and the 7th century AD. Earlier in 2016, geophysical surveys revealed the existence of walls and layers of buildings at the site. Excavation in the later part of the year yielded walls, said to belong to a palace, a meter in thickness. Additionally, numerous artifacts were also unearthed, including luxury objects imported from distant lands. Such objects include fragments of fine glass, a rim of Phocaean red-slip wear, and late Roman amphorae, which are reported to have been used for the transportation of wine and olive oil from the Mediterranean to Tintagel.

It has also been reported that this palace belonged to the rulers of an ancient south-west British kingdom known as Dumnonia. This kingdom is said to have had its center in modern day Devon, and included parts of present day Cornwall and Somerset. It has been suggested that the story of King Arthur’s conception at Tintagel has something to do with the Kingdom of Dumnonia, or at least with its memory.

During the 12th century, the writer Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote the Historia Regum Britanniae (translated into English as ‘The History of the Kings of Britain’), a pseudohistorical account of British history. One of the figures in this account was King Arthur, whom, according to Geoffrey, was conceived at Tintagel. It has been suggested that Geoffrey was inspired by the memory of Tintagel as a royal site in earlier centuries to link it with the place of the legendary king’s conception.

According to legend, Arthur’s father, Uther Pendragon, fell in love with / lusted after Igraine, the wife of Gorlois of Cornwall, whose fortress was at Tintagel. Uther managed to persuade Merlin to use his magic to fulfil his desire. Merlin transformed Uther into the image of Gorlois, and he was able to enter Tintagel Castle to seduce the queen. It was by this way that Arthur is said to have been conceived.

An illustration by N. C. Wyeth for The Boy's King Arthur (1922) ( Public Domain )

During the 1230s, Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall, second son of King John of England, and brother of King Henry III of England, decided to build a castle on Tintagel Island.

It has been pointed out that the castle was built based purely on the Arthurian legend connected to that site, and that it was of no military value whatsoever. The castle was inherited by the earl’s descendants, though they are said to have made little use of it. By the middle of the 14th century, about a century after the castle was built, the Great Hall is said to have been roofless, and another century later, the castle had fallen into ruins.

Ruins of the Norman castle at Tintagel. ( CC BY 2.5 )

It is the ruins of Richard’s castle that can still be seen today. The castle remains as the property of the Duchy of Cornwall, and may be visited by the public. In 2016, it was reported that an artwork depicting Merlin was carved into the rock face close to the spot where Arthur was said, according to legend, to have been conceived. In addition, a footbridge (the design of which was selected from a competition) to connect the mainland and the castle is planned to be built. Whilst some have viewed these positively, as they are aimed at bringing in more tourists, others have called it a ‘Disneyfication’ of the site.

Top image: Tintagel Castle, Cornwall. Photo source: ( CC BY 2.0 )

By Wu Mingren

Published on May 25, 2018 23:00

May 24, 2018

When did the leopards on the royal arms of England become the lions depicted today?

History Extra

The medieval bestiary comprised real and mythical creatures, and the medieval intellect wasn’t interested in our modern post-Enlightenment taxonomy

Hence the yarn about the heraldic painter who visits the royal menagerie in the Tower of London and protests that the caged lions are not lions. “I know what lions look like,” he says. “I’ve been painting them all my life.”

Generally speaking (and there are many exceptions in different traditions), a lion rampant (standing erect with forepaws raised) was a lion, while a lion walking with head turned full-face (passant guardant), as in the English royal arms, was a leopard. ‘Leopard’ was a technical heraldic distinction, and there were no spotted felines on any coat-of-arms in the Middle Ages.

Like all heraldic animals, the leopard carried some symbolic meaning; it was thought to be the result of an adulterous union between a lion and a mythical beast called a ‘pard’ (hence leo-pard). Believed to be incapable of reproducing, leopards were sometimes (but not always) used for someone born of adultery, or unable to have children – a senior clergyman for example.

The English royal arms included the three lions from the time of Richard I (reigned 1189–99) onwards (with a few early gaps). The English usually referred to them as leopards until the late 1300s when they started calling them lions. French heralds continued to call them leopards, and, during the Hundred Years’ War, the French sometimes referred to the English as ‘the leopards’.

Answered by Eugene Byrne, author and journalist.

Published on May 24, 2018 23:30

May 23, 2018

How many fingers did Anne Boleyn have?

History Extra

There is no concrete evidence that Anne Boleyn had six fingers. George Wyatt, grandson of court poet and ambassador Sir Thomas Wyatt, made reference to an extra nail on one of Anne’s fingers, which may be plausible, although no other reference exists.

Nicholas Sander, a Catholic Recusant who was living in exile during Elizabeth I’s rule, went even further, describing Anne’s numerous deformities, including a sixth finger, effectively labelling her a witch. But Sander was writing with a political and religious agenda: he resented the schism with Rome, and his account was intended to taint not only Anne’s name, but Elizabeth’s as well.

Lauren Mackay is the author of Inside the Tudor Court: Henry VIII and his Six Wives through the Life and Writings of the Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys (Amberley Publishing).

Published on May 23, 2018 23:00

What did they wear in Ancient Rome?

History Extra

The Romans had a variety of clothes for everyday use, including simple tunics, mantles and cloaks (for men) and shawls and gowns (for women). Fine brooches were regularly worn in order to pin layers down and keep them in place.

Trousers were considered a very ‘barbarian’ form of dress, and no self-respecting Roman male would be seen in anything that completely covered his legs. Loincloths, bandages and leather bands were used to support the nether-regions in the absence of briefs, pants or bras.

The most famous article of Roman clothing was the toga – a large semicircular blanket of woollen cloth wrapped around the body in such a way that it required the wearer to continually support it with their left arm. The toga was heavy, hot and impracticable, but as an emblem of civilian power it was an essential item of dress for all ceremonial, political or official occasions.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication.

Published on May 23, 2018 00:00

May 21, 2018

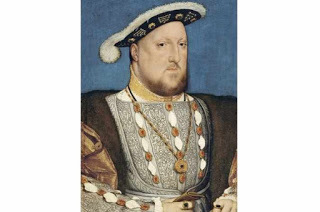

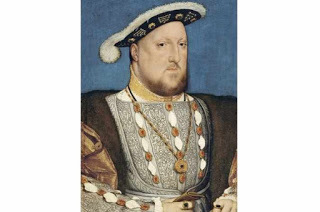

Was Henry VIII a good king?

History Extra

The success of Henry’s reign is mixed. Economically, England flourished, partially at the expense of countless monasteries and religious houses. But Henry was also a patron of the arts and humanist learning, and was a driving force behind an enthusiastic building campaign.

He also fortified England, building an impressive navy that would impact the reigns of Mary I and Elizabeth I. But it is perhaps his break with papal authority and his six marriages for which he is best known.

The break with Rome arguably gave England a sense of national identity, and Henry’s numerous wives and matrimonial dramas have captured our imaginations.

Lauren Mackay is the author of Inside the Tudor Court: Henry VIII and his Six Wives through the Life and Writings of the Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys (Amberley Publishing).

The success of Henry’s reign is mixed. Economically, England flourished, partially at the expense of countless monasteries and religious houses. But Henry was also a patron of the arts and humanist learning, and was a driving force behind an enthusiastic building campaign.

He also fortified England, building an impressive navy that would impact the reigns of Mary I and Elizabeth I. But it is perhaps his break with papal authority and his six marriages for which he is best known.

The break with Rome arguably gave England a sense of national identity, and Henry’s numerous wives and matrimonial dramas have captured our imaginations.

Lauren Mackay is the author of Inside the Tudor Court: Henry VIII and his Six Wives through the Life and Writings of the Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys (Amberley Publishing).

Published on May 21, 2018 23:30

May 20, 2018

What is the oldest law in England?

History Extra

Habeas corpus is, indeed, one of the most distinctive features of English law and may well be the oldest in force. The law means literally “you shall have the body”, but in practice allows any court of law to demand that any person is brought before it. Historically it has been used to stop a person being held in prison unlawfully or without a fair trial.

Habeas corpus is often said to originate in Magna Carta, signed by King John in 1215. The habeas corpus provisions in Magna Carta were codifying an already existing procedure that dates back to the 1130s and probably to pre-Norman England.

Although habeas corpus is still on the statute book, the version now in force dates from the amended Magna Carta issued by Edward I in 1297. The oldest formally written law still in force in England is therefore the Distress Act of 1267. This made it illegal to seek ‘distress’, or compensation for damage, by any means other than a lawsuit in a court of law – effectively outlawing private feuds.

Answered by Rupert Matthews, historian and author.

Published on May 20, 2018 23:00

May 19, 2018

How did Ancient Egyptians mummify a body?

History Extra

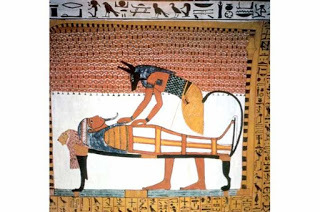

Egypt’s undertakers employed different mummification methods at different times. Here are details of the classic method, as used on Tutankhamun.

The deceased was taken to the undertaker’s workshop soon after death. The body was stripped, laid on a sloping table, and washed in natron solution (a naturally occurring salt used both as soap and a preservative).

The brain was emptied out of the skull via a hole made through the ethmoid bone (the bone separating the nasal cavity from the skull cavity). Next, an incision was made in the left flank, and the stomach, intestine, lungs and liver pulled out. These organs were preserved so that they might be buried with the mummy.

With the finger and toenails tied in place, the corpse was packed inside and out with natron and left for 40 days, until entirely dry. The desiccated body was then washed, oiled and packed with linen to restore its shape.

Wrapping was a long and complicated process, as the undertakers employed a mixture of bandages, linen pads and sheets to give the mummy a life-like appearance, and a mixture of charms and amulets, distributed within the bandages, to ensure its protection. Finally, the wrapped mummy was placed in its coffin.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Life Sciences at the University of Manchester, where she writes and teaches a number of Egyptology courses.

Published on May 19, 2018 23:00

May 18, 2018

Where, in Ancient Egypt, did people live?

History Extra

The thick mud deposited by the River Nile made an excellent building material. Mud-brick buildings are well suited to hot, dry climates, being cool in summer and warm in winter, so it is not surprising that the Egyptians built their homes and palaces from mud. They saved stone for the temples and the tombs they built in the desert.

Mud bricks were cheap and easily available, so they allowed Egypt’s architects to experiment with large-scale structures that could be raised with surprising speed. Several kings founded cities which grew from nothing to fully functional in just seven or eight years. These cities included spacious elite villas with gardens, and more humble terraced housing for workers.

Throughout the Dynastic age the population was concentrated in the area around Thebes (modern Luxor: southern Egypt) and in the area around Memphis (today just to the south of modern Cairo). Today the settlements have almost all vanished – either dissolved into mud or crumbled to dust.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Life Sciences at the University of Manchester, where she writes and teaches a number of Egyptology courses. You can follow her on Twitter @JoyceTyldesley.

Published on May 18, 2018 23:30

May 17, 2018

When did our kings and queens start using surnames?

Monarchs in Britain have adopted second names such as ‘Fair’, ‘Ironside’ or ‘Harefoot’ since at least the ninth century...

Although early British monarchs may have adopted second names, these were not hereditary and were more in the way of nicknames.

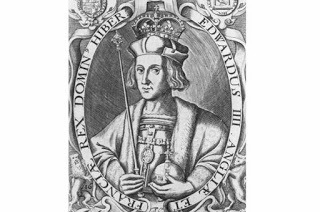

The Irish and Welsh rulers kept this system and did not adopt surnames. The first English monarch to use a hereditary surname was Edward IV. He used the surname Plantagenet to emphasise that he was descended from the elder branch of the royal family – unlike Henry VI who came from a younger branch.

The name Plantagenet refers back to Henry II who came to the throne in 1154. Although it had not been used in formal documents before Edward IV, it must have been in informal use during that period as it was clearly of practical benefit to Edward.

The first Scottish king to have a surname is generally said to have been John de Balliol, who gained the throne in 1292 after the death of Margaret, heiress to Alexander III. However, John’s surname was more of a title indicating his hereditary lordship, an objection that could also be made to Robert the Bruce (ruled 1306–1329). The first Scots king undeniably to have a surname was Robert Stewart (or Stuart) who gained the throne in 1371 and ruled for 19 years. His surname derived from the family’s traditional role as Stewards of Scotland.

This Q&A was answered by historian and author Rupert Matthews.

Published on May 17, 2018 23:30

May 16, 2018

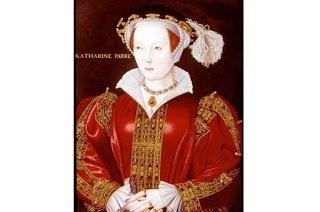

What happened to Katherine Parr’s daughter, Mary Seymour, after her mother’s death?

History Extra

Following Katherine’s death a matter of days after Mary’s birth, the newborn’s father, Thomas Seymour, placed Mary in the household of his brother, the Duke of Somerset.

But the brothers’ relationship deteriorated and as Thomas faced death for treason, he appointed the Duchess of Suffolk, Katherine’s close friend, as Mary’s guardian.

The Duchess of Suffolk’s main estate was at Grimsthorpe in Lincolnshire and Mary moved there with her little retinue. Her guardian resented the cost of looking after Mary and petitioned William Cecil, then in Somerset’s household, for additional funds to support her. These were granted in autumn 1549, and in January 1550 an act of parliament restored Mary’s title to her father’s remaining property.

There was, however, very little left. The Privy Council’s grant to Mary was not renewed in September 1550 and she never claimed any part of her father’s estate, leading to the conclusion that she died around the time of her second birthday.

There is a story that Mary survived, cared for by the Aglionbys (a northern family who had once been clients of the Parrs), and married a courtier in the service of Anne of Denmark, queen of James I. In the absence of documentary proof, it seems far likelier that this tragic orphan died very young.

Answered by Linda Porter, author of Katherine the Queen (MacMillan, 2010).

Published on May 16, 2018 23:00