MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 21

May 15, 2018

Why did Ancient Rome fall?

History Extra

A whole variety of reasons can be suggested to explain the fall of the Roman Empire in the west: disease, invasion, civil war, social unrest, inflation, economic collapse. In fact all were contributory factors, although key to the collapse of Roman authority was the prolonged period of imperial in-fighting during the 3rd and 4th century.

Conflict between multiple emperors severely weakened the military, eroded the economy and put a huge strain upon local populations. When Germanic migrants arrived, many western landowners threw their support behind the new ‘barbarian’ elite rather than continuing to back the emperor.

Reduced income from the provinces meant that Rome could no longer pay or feed its military and civil administration, making the imperial system of government redundant. The western half of the Roman empire mutated into a variety of discrete kingdoms while the east, which largely avoided both the in-fighting and barbarian migrations, survived until the 15th century.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication.

Published on May 15, 2018 23:00

May 14, 2018

Who ruled in Ancient Rome?

History Extra

Rome made much of the fact that it was a republic, ruled by the people and not by kings.

Rome had overthrown its monarchy in 509 BC, and legislative power was thereafter vested in the people’s assemblies: political power in the senate, and military power with two annually elected magistrates known as consuls.

The acronym ‘SPQR’, for Senatus Populusque Romanus (‘the Senate and People of Rome’) was proudly emblazoned across inscriptions and military standards throughout the Mediterranean – a reminder that Rome’s people (theoretically) had the last word.

By the late 1st century BC, the combination of power-hungry politicians and large overseas territories resulted in the breakdown of traditional systems of government. Even after the rise of the emperors – kings in all but name, who ‘guided’ the Roman political system in the 1st century AD – ‘SPQR’ continued to be used in order to sustain the fiction that Rome was a state governed by purely republican principles.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication.

Published on May 14, 2018 23:00

May 13, 2018

Who founded Ancient Rome?

History Extra

Like all ancient societies, the Romans possessed a heroic foundation story. What made the Romans different, however, is that they created two distinct creation myths for themselves.

In the first it was claimed that they were descended from the royal Trojan refugee Aeneas (himself the son of the goddess Venus). In the second it was stated that the city of Rome was founded by, and ultimately named after, Romulus, son of a union between an earthly princess and the god Mars.

Both myths helped establish the Romans as a divinely chosen people whose ancestry could be traced back to Troy and the Hellenistic world. Roman tradition had Romulus’ foundling city established on the Palatine Hill in what became, for Rome, ‘Year One’ (or 753 BC in the Christian calendar of the West). Archaeological excavation on the hill has found settlement here dating back to at least 1000 BC.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication.

Like all ancient societies, the Romans possessed a heroic foundation story. What made the Romans different, however, is that they created two distinct creation myths for themselves.

In the first it was claimed that they were descended from the royal Trojan refugee Aeneas (himself the son of the goddess Venus). In the second it was stated that the city of Rome was founded by, and ultimately named after, Romulus, son of a union between an earthly princess and the god Mars.

Both myths helped establish the Romans as a divinely chosen people whose ancestry could be traced back to Troy and the Hellenistic world. Roman tradition had Romulus’ foundling city established on the Palatine Hill in what became, for Rome, ‘Year One’ (or 753 BC in the Christian calendar of the West). Archaeological excavation on the hill has found settlement here dating back to at least 1000 BC.

Dr Miles Russell is a senior lecturer in prehistoric and Roman archaeology, with more than 25 years experience of archaeological fieldwork and publication.

Published on May 13, 2018 23:00

May 12, 2018

Q&A: Samuel Morse invented the Morse code, but how did he do it, how long did it take, and how long before it was accepted?

History Extra

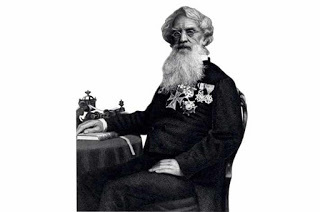

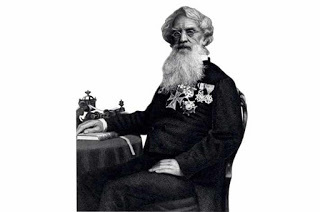

A well-known painter and keen amateur inventor, Samuel Morse came up with the idea for an electric telegraph when he heard about electromagnetism on a voyage from France to New York in 1832

By 1837 Morse had developed a working one-wire model. It produced a zig-zag line on a strip of ticker tape, the dips of which could be decoded into letters and numbers with a special dictionary composed by Morse himself.

But it was Alfred Vail, a friend from New York University, who deserves much of the credit for what came next. At his family’s iron works in Speedwell, New Jersey, Vail made changes that resulted in a stylus that lifted up from the tape, leaving dots and dashes instead of a continuous line. According to Franklin T Pope, later a partner of Thomas Edison, Vail also simplified Morse’s awkward lookup system, using shorter codes for commonly used letters. The resulting system was much better; it did not require printing and instead could be ‘sound read’.

Regardless of who deserves the credit, in 1838, at an exhibition in New York, Morse transmitted 10 words per minute using what would forever be known as Morse code. In 1843, he received money from Congress to build a line from Baltimore to Washington DC, and, on 24 May 1844, sent the first inter-city message: “What hath God wrought!” By 1854 there were 23,000 miles of telegraph wire in operation across the US.

Morse code was later adapted to wireless radio. By the 1930s it was the preferred form of communication for aviators and seamen, and it was vital during the Second World War.

Answered by Dan Cossins, freelance writer. This Q&A first appeared in the December 2012 issue of BBC History Magazine.

A well-known painter and keen amateur inventor, Samuel Morse came up with the idea for an electric telegraph when he heard about electromagnetism on a voyage from France to New York in 1832

By 1837 Morse had developed a working one-wire model. It produced a zig-zag line on a strip of ticker tape, the dips of which could be decoded into letters and numbers with a special dictionary composed by Morse himself.

But it was Alfred Vail, a friend from New York University, who deserves much of the credit for what came next. At his family’s iron works in Speedwell, New Jersey, Vail made changes that resulted in a stylus that lifted up from the tape, leaving dots and dashes instead of a continuous line. According to Franklin T Pope, later a partner of Thomas Edison, Vail also simplified Morse’s awkward lookup system, using shorter codes for commonly used letters. The resulting system was much better; it did not require printing and instead could be ‘sound read’.

Regardless of who deserves the credit, in 1838, at an exhibition in New York, Morse transmitted 10 words per minute using what would forever be known as Morse code. In 1843, he received money from Congress to build a line from Baltimore to Washington DC, and, on 24 May 1844, sent the first inter-city message: “What hath God wrought!” By 1854 there were 23,000 miles of telegraph wire in operation across the US.

Morse code was later adapted to wireless radio. By the 1930s it was the preferred form of communication for aviators and seamen, and it was vital during the Second World War.

Answered by Dan Cossins, freelance writer. This Q&A first appeared in the December 2012 issue of BBC History Magazine.

Published on May 12, 2018 23:30

May 11, 2018

Rome’s Flaminian Obelisk: an epic journey from divine Egyptian symbol to Tourist Attraction

Ancient Origins

Nicky Nielson /The Conversation

It’s a great place to sit in the shade and enjoy a gelato. The base of the Flaminian Obelisk in the Piazza del Popolo on the northern end of Rome’s ancient quarter offers views of the twin churches of Santa Maria dei Miracoli and Santa Maria di Montesanto. But while enjoying the outlook, take a few minutes to marvel at how this 23-metre chunk of granite ended up where it has.

The Flaminian Obelisk was carved at the height of Egypt’s New Kingdom, during the reign of Seti I (1290 to 1279 BC), the father of Ramesses the Great. “Carved” is a rather clinical expression for an astounding feat of engineering. Quarrying and moving a 263-ton chunk of granite – with the additional issue of not having access to any metal harder than bronze – is no mean feat.

The Piazza del Popolo and the Flaminio Obelisk in Rome. Image: Wolfgang Moroder /CC BY-SA 3.0

The process used by the Egyptians was surprisingly straightforward. Initially, they levelled off the ground above a vein of granite. Then the rough shape of the obelisk was marked using hard stone pounders. Channels were carved in the rock around the shape of the obelisk before it was separated from the bedrock entirely by carving under its bulk.

Afterwards, the obelisk was shipped on barges nearly 900km north to the Temple of Heliopolis near modern Cairo and dedicated to the sun god Re-Horakhty – and of course to the memory of both Seti and Ramesses.

Egypt in vogue

Though much of our current obsessive cultural interest in ancient Egypt can be traced to key events such as the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, other cultures at other times in history have had an equal interest in the land of the Pharaohs – and a similar penchant for creatively misrepresenting it.

Canopo in Villa Adriana, Tivoli. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

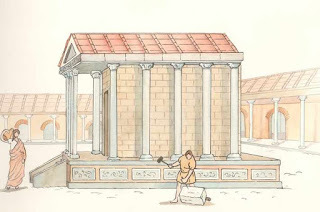

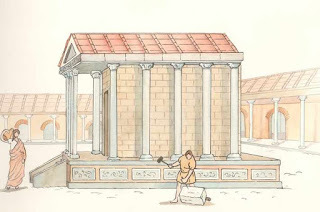

At the height of the Roman Empire, “Egyptianising” architectural elements became very popular. Sites such as the Villa Adriana in Tivoli, built in the second century AD as a retreat for Emperor Hadrian, is positively lousy with Egyptianised statues and architectural elements – including an Egyptian-style shrine dedicated to the emperor’s lover, Antinous .

While these imitations of Egyptian styles and fashions (creatively altered for a Roman audience) were extremely popular, several Roman rulers went a step further. Rather than simply imitating Egyptian architecture, they brought some home with them from Egypt.

After the defeat of Cleopatra and Mark Anthony in 30 BC, the first Roman emperor, Augustus Caesar, set his sights on the Flaminian Obelisk which had remained for more than 1,200 years at Heliopolis. To commemorate his comprehensive victory, Augustus opted to bring the obelisk back to Rome on a specially designed vessel, which was later destroyed in a fire in Puteoli.

Upon its arrival in Rome, Augustus added a Latin inscription underneath the far older hieroglyphs of the obelisk, extolling his own triumphs as the new ruler of Egypt. To show off his achievement, he ordered the obelisk raised at Circus Maximus.

As Christianity rose to prominence and became the official state religion of the Roman Empire, the arena fell into decay and flooding eventually toppled the obelisk. It was gradually buried in alluvial soil, lying undiscovered for nearly 1,000 years until it was unearthed at the height of the Italian Renaissance in 1587.

Photochrom print by Photoglob Zürich , between 1890 and 1900. ( CC BY 2.0 )

Renaissance renewal

A product of the Italian Renaissance, Pope Sixtus V (1521-1590) embarked on a wide-ranging program of urban renewal in Rome shortly after his election to the Papal Throne. Ironically, while he is credited with reerecting no less than four ancient obelisks in Rome , he had very little appreciation for the city’s own antiquity, ordering several ancient monuments demolished and the stone reused as building material.

When the Flaminian Obelisk was rediscovered in 1587, Sixtus charged the noted architect Domenico Fontana (1543-1607) with the task of raising the monolith in Piazza del Popolo (at that time a place of public executions), a task which he accomplished in 1589. Fontana was experienced in the art of raising obelisks – three years earlier, he had been responsible for placing the Vatican obelisk (which is heavier than the Flaminian obelisk by nearly 100 tons) in St Peter’s Square. In an attempt to detract from the quite obvious pagan nature of the monuments, both were crowned with large crosses.

View of the Piazza del Popolo, Rome by Gaspar van Wittel (c. 1678) showing the Flaminian Obelisk and the surrounding square. Author provided

With this, the journey of the Flaminian Obelisk from an ancient Egyptian tribute to the sun god to a Renaissance curio was completed. But the monument’s impact on history continued – in 1921, a year before seizing power after the March on Rome, Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) led a march past the obelisk during the Third Fascist Congress . Later on, the Flaminian Obelisk and the many other Egyptian and Roman obelisks found throughout the city prompted the dictator to create his own: a massive 300-ton marble behemoth which still stands in Foro Italico (then Foro Mussolini) bearing the Latin inscription MVSSOLINI DVX (Mussolini, the Leader).

The Flaminian Obelisk is a multicultural monument in many ways. It remains today in its square, a physical testament to the grandiose ideas of three rulers – each in their own way both secular and divine: Pharaoh Seti I, Emperor Augustus Caesar and Pope Sixtus V.

Top image: Roma: Piazza del Popolo by Hendrik Franz van Lint. ( Public Domain )

The article ‘Rome’s Flaminian Obelisk: an epic journey from divine Egyptian symbol to Tourist Attraction’ by Nicky Nielson was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Nicky Nielson /The Conversation

It’s a great place to sit in the shade and enjoy a gelato. The base of the Flaminian Obelisk in the Piazza del Popolo on the northern end of Rome’s ancient quarter offers views of the twin churches of Santa Maria dei Miracoli and Santa Maria di Montesanto. But while enjoying the outlook, take a few minutes to marvel at how this 23-metre chunk of granite ended up where it has.

The Flaminian Obelisk was carved at the height of Egypt’s New Kingdom, during the reign of Seti I (1290 to 1279 BC), the father of Ramesses the Great. “Carved” is a rather clinical expression for an astounding feat of engineering. Quarrying and moving a 263-ton chunk of granite – with the additional issue of not having access to any metal harder than bronze – is no mean feat.

The Piazza del Popolo and the Flaminio Obelisk in Rome. Image: Wolfgang Moroder /CC BY-SA 3.0

The process used by the Egyptians was surprisingly straightforward. Initially, they levelled off the ground above a vein of granite. Then the rough shape of the obelisk was marked using hard stone pounders. Channels were carved in the rock around the shape of the obelisk before it was separated from the bedrock entirely by carving under its bulk.

Afterwards, the obelisk was shipped on barges nearly 900km north to the Temple of Heliopolis near modern Cairo and dedicated to the sun god Re-Horakhty – and of course to the memory of both Seti and Ramesses.

Egypt in vogue

Though much of our current obsessive cultural interest in ancient Egypt can be traced to key events such as the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, other cultures at other times in history have had an equal interest in the land of the Pharaohs – and a similar penchant for creatively misrepresenting it.

Canopo in Villa Adriana, Tivoli. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

At the height of the Roman Empire, “Egyptianising” architectural elements became very popular. Sites such as the Villa Adriana in Tivoli, built in the second century AD as a retreat for Emperor Hadrian, is positively lousy with Egyptianised statues and architectural elements – including an Egyptian-style shrine dedicated to the emperor’s lover, Antinous .

While these imitations of Egyptian styles and fashions (creatively altered for a Roman audience) were extremely popular, several Roman rulers went a step further. Rather than simply imitating Egyptian architecture, they brought some home with them from Egypt.

After the defeat of Cleopatra and Mark Anthony in 30 BC, the first Roman emperor, Augustus Caesar, set his sights on the Flaminian Obelisk which had remained for more than 1,200 years at Heliopolis. To commemorate his comprehensive victory, Augustus opted to bring the obelisk back to Rome on a specially designed vessel, which was later destroyed in a fire in Puteoli.

Upon its arrival in Rome, Augustus added a Latin inscription underneath the far older hieroglyphs of the obelisk, extolling his own triumphs as the new ruler of Egypt. To show off his achievement, he ordered the obelisk raised at Circus Maximus.

As Christianity rose to prominence and became the official state religion of the Roman Empire, the arena fell into decay and flooding eventually toppled the obelisk. It was gradually buried in alluvial soil, lying undiscovered for nearly 1,000 years until it was unearthed at the height of the Italian Renaissance in 1587.

Photochrom print by Photoglob Zürich , between 1890 and 1900. ( CC BY 2.0 )

Renaissance renewal

A product of the Italian Renaissance, Pope Sixtus V (1521-1590) embarked on a wide-ranging program of urban renewal in Rome shortly after his election to the Papal Throne. Ironically, while he is credited with reerecting no less than four ancient obelisks in Rome , he had very little appreciation for the city’s own antiquity, ordering several ancient monuments demolished and the stone reused as building material.

When the Flaminian Obelisk was rediscovered in 1587, Sixtus charged the noted architect Domenico Fontana (1543-1607) with the task of raising the monolith in Piazza del Popolo (at that time a place of public executions), a task which he accomplished in 1589. Fontana was experienced in the art of raising obelisks – three years earlier, he had been responsible for placing the Vatican obelisk (which is heavier than the Flaminian obelisk by nearly 100 tons) in St Peter’s Square. In an attempt to detract from the quite obvious pagan nature of the monuments, both were crowned with large crosses.

View of the Piazza del Popolo, Rome by Gaspar van Wittel (c. 1678) showing the Flaminian Obelisk and the surrounding square. Author provided

With this, the journey of the Flaminian Obelisk from an ancient Egyptian tribute to the sun god to a Renaissance curio was completed. But the monument’s impact on history continued – in 1921, a year before seizing power after the March on Rome, Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) led a march past the obelisk during the Third Fascist Congress . Later on, the Flaminian Obelisk and the many other Egyptian and Roman obelisks found throughout the city prompted the dictator to create his own: a massive 300-ton marble behemoth which still stands in Foro Italico (then Foro Mussolini) bearing the Latin inscription MVSSOLINI DVX (Mussolini, the Leader).

The Flaminian Obelisk is a multicultural monument in many ways. It remains today in its square, a physical testament to the grandiose ideas of three rulers – each in their own way both secular and divine: Pharaoh Seti I, Emperor Augustus Caesar and Pope Sixtus V.

Top image: Roma: Piazza del Popolo by Hendrik Franz van Lint. ( Public Domain )

The article ‘Rome’s Flaminian Obelisk: an epic journey from divine Egyptian symbol to Tourist Attraction’ by Nicky Nielson was originally published on The Conversation and has been republished under a Creative Commons license.

Published on May 11, 2018 23:30

May 10, 2018

Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities Announces there are NO Hidden Chambers in Tut’s Tomb

Ancient Origins

The Egyptian antiquities ministry have announced the results of a new survey on the tomb of Tutankhamun. They have apparently discredited a theory, that suggest there was a second chamber in the Pharaoh’s tomb. It had been speculated that this second undiscovered chamber was the tomb of the famous Queen Nefertiti. Mostafa Waziri, Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities announced the official result of the investigation and stated categorically that there is no second chamber. According to the Egyptian authorities, an Italian scientific team from the University of Turin found that there is " conclusive evidence of the non-existence of hidden chambers adjacent to or inside Tutankhamun's tomb ". Has this ended the speculation that there remains to be discovered another tomb alongside that of Tutankhamun’s?

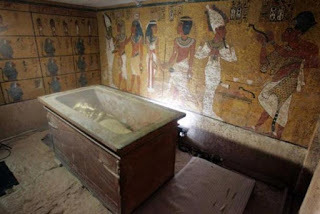

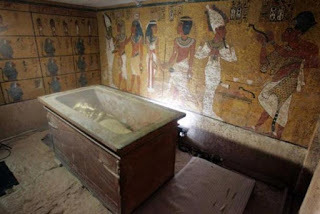

The stone sarcophagus containing the mummy of King Tut is seen in his underground tomb. Credit: Nasser Nuri.

The Tomb of Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun was Pharaoh of Egypt during the New Kingdom period, a golden age in Egyptian history. His father was the controversial Pharaoh Akhenaten, but the identity of his mother is still unknown. Tutankhamun became Pharaoh several years after the death of his father and a succession of short lived rulers, whose religious innovations had badly divided the kingdom. Under the boy-king, his father’s Monotheism was abandoned, and the traditional Egyptian religion was restored. He later married his half-sister and died while still a very young man and this has led to various theories about his death, including that he was secretly assassinated.

The gold laden tomb of Tutankhamun was discovered by Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings in 1922. It is arguably the most spectacular archaeological find in history and it produced an unprecedented trove of treasures that have astonished the world ever since they were brought into the light. The tomb and the life of Tutankhamun has remained a source of fascination for both the expert and the public ever since.

Researchers scanning the walls of King Tutankhamun’s burial chamber using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) equipment. (Ministry of Antiquities)

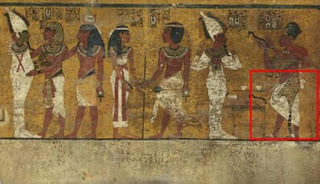

Second-Chamber Theory

British Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves had been the chief proponent of a theory that there was a second chamber in the tomb of Tutankhamun . He argued that it was likely to be the burial chamber of the famous Nefertiti , the wife of Tutankhamun's father, King Akhenaten and reputed to be one of the most beautiful women in history. Reeves argued that because Tutankhamun died unexpectedly that he was hurriedly buried in the outer chamber of Nefertiti’s tomb. This he argued means that the royal burial chamber of the queen was hidden behind the tomb of Tutankhamun and that many fabulous treasures were laying there waiting to be discovered. Reeves even believed that he had detected hidden doors behind the funerary painting on the walls of the Pharaoh’s tomb.

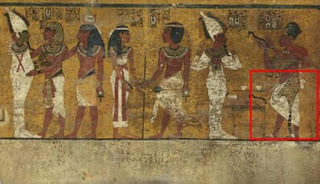

Previous scans of the north wall of King Tutankhamun's burial chamber indicated features beneath the intricately decorated plaster (highlighted) a researcher believes may be a hidden door, possibly to the burial chamber of Nefertiti. Credit: Factum Arte.

Inconclusive Survey Results

The theory prompted a group of researchers to test if Reeve’s assertions had any basis in fact. A team of Japanese experts used radar to scan the tomb of Tutankhamun and they claimed ‘with 95 percent certainty the existence of a doorway and a hall with artefacts’. This seemed to provide support to the theory of Reeves that there was a secret chamber and was presumably undiscovered. Initially the findings were supported by a former Egyptian minister of the antiquities, but this drew criticism from many experts.

In 2016 an American survey, used ground penetrating radar (GPR) on the tomb but was unable to confirm or to reject the second—chamber theory. A new Minister of antiquities convened a conference that ‘ decided to conduct a third GPR analysis to put an end to the debate’ . This third survey was led by Francesco Porcelli, of the Polytechnic University in Turin with the assistance of two private geophysics companies.

‘No Indication’

After an exhaustive survey, the Italian team have found no evidence that there was any second chamber or corridors in the tomb complex of Tutankhamun. The technology that was used by the team simply did not find any data that would indicate the existence of a chamber. According to the statement released by the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities on its Facebook page:

the radargrams do not show any indication of plane reflectors, which could be interpreted as chamber walls or void areas behind the paintings

They state this with a high degree of confidence and they are effectively rejecting earlier investigations and the theory of Reeves.

The views of Reeves and others who supported his theory are as yet unknown. However, the statement, issued by the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities would suggest that the argument for a second burial chamber has been decisively rejected. It will undoubtedly disappoint many who had hoped that the burial chamber of the legendary Queen Nefertiti could be once more revealed to the world.

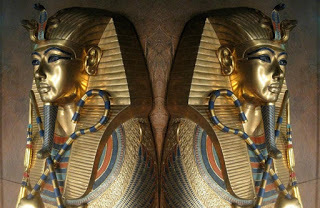

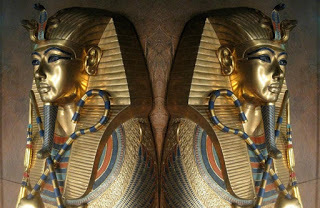

Top image: Sarcophagus of Tutankhamun double image. ( Public Domain )

By Ed Whelan

The Egyptian antiquities ministry have announced the results of a new survey on the tomb of Tutankhamun. They have apparently discredited a theory, that suggest there was a second chamber in the Pharaoh’s tomb. It had been speculated that this second undiscovered chamber was the tomb of the famous Queen Nefertiti. Mostafa Waziri, Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities announced the official result of the investigation and stated categorically that there is no second chamber. According to the Egyptian authorities, an Italian scientific team from the University of Turin found that there is " conclusive evidence of the non-existence of hidden chambers adjacent to or inside Tutankhamun's tomb ". Has this ended the speculation that there remains to be discovered another tomb alongside that of Tutankhamun’s?

The stone sarcophagus containing the mummy of King Tut is seen in his underground tomb. Credit: Nasser Nuri.

The Tomb of Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun was Pharaoh of Egypt during the New Kingdom period, a golden age in Egyptian history. His father was the controversial Pharaoh Akhenaten, but the identity of his mother is still unknown. Tutankhamun became Pharaoh several years after the death of his father and a succession of short lived rulers, whose religious innovations had badly divided the kingdom. Under the boy-king, his father’s Monotheism was abandoned, and the traditional Egyptian religion was restored. He later married his half-sister and died while still a very young man and this has led to various theories about his death, including that he was secretly assassinated.

The gold laden tomb of Tutankhamun was discovered by Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings in 1922. It is arguably the most spectacular archaeological find in history and it produced an unprecedented trove of treasures that have astonished the world ever since they were brought into the light. The tomb and the life of Tutankhamun has remained a source of fascination for both the expert and the public ever since.

Researchers scanning the walls of King Tutankhamun’s burial chamber using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) equipment. (Ministry of Antiquities)

Second-Chamber Theory

British Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves had been the chief proponent of a theory that there was a second chamber in the tomb of Tutankhamun . He argued that it was likely to be the burial chamber of the famous Nefertiti , the wife of Tutankhamun's father, King Akhenaten and reputed to be one of the most beautiful women in history. Reeves argued that because Tutankhamun died unexpectedly that he was hurriedly buried in the outer chamber of Nefertiti’s tomb. This he argued means that the royal burial chamber of the queen was hidden behind the tomb of Tutankhamun and that many fabulous treasures were laying there waiting to be discovered. Reeves even believed that he had detected hidden doors behind the funerary painting on the walls of the Pharaoh’s tomb.

Previous scans of the north wall of King Tutankhamun's burial chamber indicated features beneath the intricately decorated plaster (highlighted) a researcher believes may be a hidden door, possibly to the burial chamber of Nefertiti. Credit: Factum Arte.

Inconclusive Survey Results

The theory prompted a group of researchers to test if Reeve’s assertions had any basis in fact. A team of Japanese experts used radar to scan the tomb of Tutankhamun and they claimed ‘with 95 percent certainty the existence of a doorway and a hall with artefacts’. This seemed to provide support to the theory of Reeves that there was a secret chamber and was presumably undiscovered. Initially the findings were supported by a former Egyptian minister of the antiquities, but this drew criticism from many experts.

In 2016 an American survey, used ground penetrating radar (GPR) on the tomb but was unable to confirm or to reject the second—chamber theory. A new Minister of antiquities convened a conference that ‘ decided to conduct a third GPR analysis to put an end to the debate’ . This third survey was led by Francesco Porcelli, of the Polytechnic University in Turin with the assistance of two private geophysics companies.

‘No Indication’

After an exhaustive survey, the Italian team have found no evidence that there was any second chamber or corridors in the tomb complex of Tutankhamun. The technology that was used by the team simply did not find any data that would indicate the existence of a chamber. According to the statement released by the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities on its Facebook page:

the radargrams do not show any indication of plane reflectors, which could be interpreted as chamber walls or void areas behind the paintings

They state this with a high degree of confidence and they are effectively rejecting earlier investigations and the theory of Reeves.

The views of Reeves and others who supported his theory are as yet unknown. However, the statement, issued by the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities would suggest that the argument for a second burial chamber has been decisively rejected. It will undoubtedly disappoint many who had hoped that the burial chamber of the legendary Queen Nefertiti could be once more revealed to the world.

Top image: Sarcophagus of Tutankhamun double image. ( Public Domain )

By Ed Whelan

Published on May 10, 2018 23:30

May 9, 2018

Setting the Story (Mostly) Straight: Archaeological Experiment Shows How Mycenaean Stone Masons Cut Stone

Ancient Origins

Experimental archaeology can be a very useful asset when we are trying to gain a better insight on how things were done in the past. One way it helps us is to gain some understanding of the techniques our ancestors used to get through the tasks of daily life. It can also aid an archaeologist in testing out methods and deciding how accurate our recreation of past ways really is. For example, no one today can say exactly what a Bronze Age pendulum saw would have looked like or the specific method in which ancient Mycenaean stone masons used it. But a creative archaeologist in the USA has come across a form and technique which seems to mirror past ways.

As ScienceNews points out, no Bronze Age frameworks or blades have been found in the archaeological record to date. However, there has been a popular belief for the last 30 years or so that a swinging sharp metal blade was a preferred method for cutting rock by Greece’s Mycenaean civilization . Curved incisions are all that we have today to hint at the procedure.

A limestone block displays a curved, Mycenaean-style cut made by a curved blade, A, and a shallow, wobbly incision made by a triangular blade, B. ( N. Blackwell/Antiquity 2018 )

With no ancient blueprints or artifacts to give them clues, Nicholas Blackwell, an archaeologist at Indiana University Bloomington, and his father George decided to create an experimental pendulum saw. Nicholas provided his knowledge of the Bronze Age and George gave his construction knowhow. ScienceNews describes the contraption:

“a device with two side posts, each studded with five holes drilled along its upper half, supported by a base and diagonal struts. A removable steel bar ran through opposite holes on the posts and could be set at different heights. In between the posts, the bar passed through an oval notch in the upper half of a long piece of wood — the pendulum. The notch is slightly longer than a dollar bill, giving the steel bar some leeway so the pendulum could move up and down freely while sawing.”

The pendulum’s blade was a tricky feature. Thus, they created four versions of bronze blades – a long, curved one, a triangular blade with a rounded end, and short and long versions of straight edged saws. Water and sand were added during the experiment to increase lubrication and cutting power.

Blades on the top left and bottom right produced Mycenaean-style curved incisions in rock. A triangular blade, top right, created a wobbly groove. A short, straight blade, bottom left, repeatedly became stuck as it swung into a rock’s surface. ( N. Blackwell/Antiquity 2018 )

Blackwell and his brother-in-law, Brandon Synan, were in charge of testing the pendulum saw on some limestone. With some strong arms and trial and error, they eventually gained a result - a functioning pendulum saw which cuts through stone following the distinctive curved mark found on Mycenaean Bronze Age pillars, gateways and thresholds at palaces and some large tombs.

Detail of the entablature of the Lion Gate relief, showing the location of tubular drill holes and saw marks. The arrows indicate the erroneous saw cut and the unknown filling material within it. ( Blackwell/AJA 2014 )

While Blackwell and others seem convinced that the pendulum saw was the method of choice for Mycenaean stone masons, not everyone agrees. One of the main challengers to the pendulum saw is archaeologist Jürgen Seeher of the German Archaeological Institute’s branch in Istanbul - the only other known archaeologist to have built and tested a reconstruction of a pendulum saw.

Seeher published a paper in 2007 stating that “a long, curved saw attached to a wooden bar and pulled back and forth by two people, like a loggers’ saw” [via ScienceNews] would have been superior to the pendulum saw. He argued the two-man saw would have provided ancient stone masons with an easier way to obtain precision than the pendulum saw.

Two young men using a cross-cut saw on the St. Lucia Farm School, 1936. ( Public Domain )

But Blackwell explained away this problem to ScienceNews, stating that the ancient Mycenaean stone masons likely had training and obtained their skills with the pendulum saw as people learning a trade still take apprenticeships to increase their knowledge and abilities today. Furthermore, he suggests people would have worked in teams to make the difficult task a little easier.

The results of Blackwell’s recent experiment are published in the journal Antiquity.

Top Image: The Lion Gate at Mycenae. Source: Andreas Trepte/ CC BY SA 2.5

By Alicia McDermott

Experimental archaeology can be a very useful asset when we are trying to gain a better insight on how things were done in the past. One way it helps us is to gain some understanding of the techniques our ancestors used to get through the tasks of daily life. It can also aid an archaeologist in testing out methods and deciding how accurate our recreation of past ways really is. For example, no one today can say exactly what a Bronze Age pendulum saw would have looked like or the specific method in which ancient Mycenaean stone masons used it. But a creative archaeologist in the USA has come across a form and technique which seems to mirror past ways.

As ScienceNews points out, no Bronze Age frameworks or blades have been found in the archaeological record to date. However, there has been a popular belief for the last 30 years or so that a swinging sharp metal blade was a preferred method for cutting rock by Greece’s Mycenaean civilization . Curved incisions are all that we have today to hint at the procedure.

A limestone block displays a curved, Mycenaean-style cut made by a curved blade, A, and a shallow, wobbly incision made by a triangular blade, B. ( N. Blackwell/Antiquity 2018 )

With no ancient blueprints or artifacts to give them clues, Nicholas Blackwell, an archaeologist at Indiana University Bloomington, and his father George decided to create an experimental pendulum saw. Nicholas provided his knowledge of the Bronze Age and George gave his construction knowhow. ScienceNews describes the contraption:

“a device with two side posts, each studded with five holes drilled along its upper half, supported by a base and diagonal struts. A removable steel bar ran through opposite holes on the posts and could be set at different heights. In between the posts, the bar passed through an oval notch in the upper half of a long piece of wood — the pendulum. The notch is slightly longer than a dollar bill, giving the steel bar some leeway so the pendulum could move up and down freely while sawing.”

The pendulum’s blade was a tricky feature. Thus, they created four versions of bronze blades – a long, curved one, a triangular blade with a rounded end, and short and long versions of straight edged saws. Water and sand were added during the experiment to increase lubrication and cutting power.

Blades on the top left and bottom right produced Mycenaean-style curved incisions in rock. A triangular blade, top right, created a wobbly groove. A short, straight blade, bottom left, repeatedly became stuck as it swung into a rock’s surface. ( N. Blackwell/Antiquity 2018 )

Blackwell and his brother-in-law, Brandon Synan, were in charge of testing the pendulum saw on some limestone. With some strong arms and trial and error, they eventually gained a result - a functioning pendulum saw which cuts through stone following the distinctive curved mark found on Mycenaean Bronze Age pillars, gateways and thresholds at palaces and some large tombs.

Detail of the entablature of the Lion Gate relief, showing the location of tubular drill holes and saw marks. The arrows indicate the erroneous saw cut and the unknown filling material within it. ( Blackwell/AJA 2014 )

While Blackwell and others seem convinced that the pendulum saw was the method of choice for Mycenaean stone masons, not everyone agrees. One of the main challengers to the pendulum saw is archaeologist Jürgen Seeher of the German Archaeological Institute’s branch in Istanbul - the only other known archaeologist to have built and tested a reconstruction of a pendulum saw.

Seeher published a paper in 2007 stating that “a long, curved saw attached to a wooden bar and pulled back and forth by two people, like a loggers’ saw” [via ScienceNews] would have been superior to the pendulum saw. He argued the two-man saw would have provided ancient stone masons with an easier way to obtain precision than the pendulum saw.

Two young men using a cross-cut saw on the St. Lucia Farm School, 1936. ( Public Domain )

But Blackwell explained away this problem to ScienceNews, stating that the ancient Mycenaean stone masons likely had training and obtained their skills with the pendulum saw as people learning a trade still take apprenticeships to increase their knowledge and abilities today. Furthermore, he suggests people would have worked in teams to make the difficult task a little easier.

The results of Blackwell’s recent experiment are published in the journal Antiquity.

Top Image: The Lion Gate at Mycenae. Source: Andreas Trepte/ CC BY SA 2.5

By Alicia McDermott

Published on May 09, 2018 23:00

May 8, 2018

Gravlaks Cured Salmon with Mustard Sauce

Thor News

Gravlaks served with red onion, lemon, rye bread, crackle bread, potato tortillas, mustard sauce and a small glass of aquavit. (Photo: Adam Liaw, Destination Flavor Scandinavia / SBS Food)

Curing salmon is an easy way to make a really tasty meal, and the preservation method has probably been used all the way back to the Viking Age. Cured salmon is known as gravlaks in Norwegian and regarded a delicacy.

Ingredients

(Starter, snack, serves 8)

1 kg (2.2 lbs) of salmon fillet (about a whole side), with skin, without bones

75 grams (2.6 oz) of sugar

75 grams (2.6 oz) of salt

1 teaspoon of ground pepper

1/2 cup finely chopped dill

Aquavit / brandy

Mustard Sauce

1/4 cup Dijon mustard

2 tablespoons of sugar

2 tablespoons white wine vinegar

1/4 cup finely chopped dill

80 milliliters (1/3 cup) grape seed oil

You do not have to see the salmon produced here in the Namdalen valley, Central Norway, to understand that the quality is superb. (Photo: SinkabergHansen AS)

Method

Cured salmon

Divide the fish fillet crosswise into two so that there are two approximately equal parts. Place both sides with the skin side down on a large piece of plastic film.

Mix together sugar, salt and pepper and pour the mixture over the fish in a thick layer and sprinkle with dill. Pour over some drops of aquavit (see below) or brandy.

Place one part over the other so that the two skin sides face outwards. The narrow ends shall point in the same direction. Wrap the fish tightly in at least three layers of plastic film. Gently press when wrapping to get out as much air as possible. Place the fish on a dish and put it in the refrigerator for 48 hours.

Turn the fish every twelve hours.

Mustard Sauce

Whisk the ingredients together, except the grape seed oil, until they are well mixed. Continue to whisk when you little by little add some oil until the sauce has got the right consistency.

Gravlaks with Mustard Sauce

Take the fish out of the plastic and put it on a cutting board. Wipe the fish gently with damp kitchen paper to remove the remains of sugar and salt. Wipe again with dry kitchen paper. Cut thin slices of the salmon with a large, sharp knife.

Cured salmon is served with mustard sauce, lemon boats, red onion rings, rye bread and potato tortillas – or be creative and try out other types of bread, however, mustard and red onion are a must.

Aquavit Facts

Aquavit is Scandinavian spirit that has roots back to the fourteenth century. It gets distilled with herbs and spices like moth, fennel and dill. If you do not have aquavit, a good brandy can also be used.

Gravlaks served with red onion, lemon, rye bread, crackle bread, potato tortillas, mustard sauce and a small glass of aquavit. (Photo: Adam Liaw, Destination Flavor Scandinavia / SBS Food)

Curing salmon is an easy way to make a really tasty meal, and the preservation method has probably been used all the way back to the Viking Age. Cured salmon is known as gravlaks in Norwegian and regarded a delicacy.

Ingredients

(Starter, snack, serves 8)

1 kg (2.2 lbs) of salmon fillet (about a whole side), with skin, without bones

75 grams (2.6 oz) of sugar

75 grams (2.6 oz) of salt

1 teaspoon of ground pepper

1/2 cup finely chopped dill

Aquavit / brandy

Mustard Sauce

1/4 cup Dijon mustard

2 tablespoons of sugar

2 tablespoons white wine vinegar

1/4 cup finely chopped dill

80 milliliters (1/3 cup) grape seed oil

You do not have to see the salmon produced here in the Namdalen valley, Central Norway, to understand that the quality is superb. (Photo: SinkabergHansen AS)

Method

Cured salmon

Divide the fish fillet crosswise into two so that there are two approximately equal parts. Place both sides with the skin side down on a large piece of plastic film.

Mix together sugar, salt and pepper and pour the mixture over the fish in a thick layer and sprinkle with dill. Pour over some drops of aquavit (see below) or brandy.

Place one part over the other so that the two skin sides face outwards. The narrow ends shall point in the same direction. Wrap the fish tightly in at least three layers of plastic film. Gently press when wrapping to get out as much air as possible. Place the fish on a dish and put it in the refrigerator for 48 hours.

Turn the fish every twelve hours.

Mustard Sauce

Whisk the ingredients together, except the grape seed oil, until they are well mixed. Continue to whisk when you little by little add some oil until the sauce has got the right consistency.

Gravlaks with Mustard Sauce

Take the fish out of the plastic and put it on a cutting board. Wipe the fish gently with damp kitchen paper to remove the remains of sugar and salt. Wipe again with dry kitchen paper. Cut thin slices of the salmon with a large, sharp knife.

Cured salmon is served with mustard sauce, lemon boats, red onion rings, rye bread and potato tortillas – or be creative and try out other types of bread, however, mustard and red onion are a must.

Aquavit Facts

Aquavit is Scandinavian spirit that has roots back to the fourteenth century. It gets distilled with herbs and spices like moth, fennel and dill. If you do not have aquavit, a good brandy can also be used.

Published on May 08, 2018 23:00

May 7, 2018

St George’s Day: 10 things you (probably) didn’t know about him

History Extra

Here, writing for History Extra, Jonathan Good, associate professor of history at Reinhardt University in Georgia, brings you 10 lesser-known facts about England’s patron saint…

1 St George is not English

If he ever existed (and there’s no proof he did), George would likely have been a soldier somewhere in the eastern Roman Empire, probably in what is now Turkey. According to legend, he was martyred for his faith under Emperor Diocletian in the early fourth century, and his major shrine is located in Lod, Israel.

2 His earliest legends were so outlandish that the Pope condemned them

Early Christians were known to exaggerate the tortures endured by their martyrs, but St George is in a league all of his own. According to one source, St George was torn on the rack, hit on the head with hammers until his brains oozed out, forced to drink poison, torn on a wheel, boiled in lead, and much else besides – all over a period of seven years.

A fifth-century decree attributed to Pope Gelasius declared that, lest it give rise to mockery, the details were not be read out in church.

3 He was one of several military saints honoured in the Byzantine Empire Others included Theodore, Demetrius, and Mercurius.

All of these saints had been soldiers when alive, and continued their patronage of the Byzantine army in death – especially St George, who became the most popular.

Crusaders to the Holy Land in 1099 adopted this tradition of military saints, and brought the veneration of St George back to Western Europe.

4 St George is also connected to agriculture

His name means ‘earth-worker’ – that is, farmer – and his feast day of 23 April is in the spring, when crops are starting to grow. Many people throughout European history have prayed to St George for a good harvest.

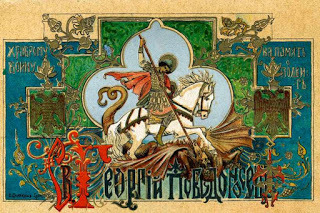

5 The dragon was not always a part of St George’s story

The earliest legend that features St George rescuing a princess from a dragon dates to the 11th century. It may have started simply as a way to explain icons of military saints slaying dragons, symbolising the triumph of good over evil.

For the permanent association of St George and the dragon we have to thank the Golden Legend, a popular collection of saints’ lives written in the 13th century.

6 He is the patron saint of many places

These include countries like Ethiopia, Georgia and Portugal, and cities such as Freiburg, Moscow and Beirut. George was seen as an especially powerful intercessor, and the dragon story has a universal appeal.

7 St George was known as ‘Our Lady’s Knight’ in medieval England

As a patron of crusading, St George easily became the quintessential knight. And every knight needs to serve a lady – who better than the Blessed Virgin Mary herself?

8 Edward I is ultimately the reason why St George ‘became’ English

As a crusader, Edward I (r 1272–1307) acquired an affinity for St George, and back in England outfitted his troops with the St George’s cross when fighting the Welsh. He raised St George’s flag over Caerlaverock Castle in Scotland in 1300, among other things.

Later, Edward III, hoping to revive the glories of his grandfather’s reign, founded the Order of the Garter under the patronage of St George.

9 St George appeared to the English army at the battle of Agincourt in 1415

King Henry V (r 1413–22) was especially devoted to St George, as is reflected in Shakespeare’s play. The idea later arose that St George had actually appeared to the English during the battle of Agincourt in 1415, which was a stunning victory for them against the French.

10 The Reformation was not kind to St George

Even King Edward VI himself mocked the legend as improbable. But the poet Edmund Spenser, among others, kept George’s legend alive as a romantic and nationalistic story. And it is one that shows no signs of losing its appeal.

Jonathan Good’s The Cult of St George in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer) was recently updated, and is now available in paperback.

Here, writing for History Extra, Jonathan Good, associate professor of history at Reinhardt University in Georgia, brings you 10 lesser-known facts about England’s patron saint…

1 St George is not English

If he ever existed (and there’s no proof he did), George would likely have been a soldier somewhere in the eastern Roman Empire, probably in what is now Turkey. According to legend, he was martyred for his faith under Emperor Diocletian in the early fourth century, and his major shrine is located in Lod, Israel.

2 His earliest legends were so outlandish that the Pope condemned them

Early Christians were known to exaggerate the tortures endured by their martyrs, but St George is in a league all of his own. According to one source, St George was torn on the rack, hit on the head with hammers until his brains oozed out, forced to drink poison, torn on a wheel, boiled in lead, and much else besides – all over a period of seven years.

A fifth-century decree attributed to Pope Gelasius declared that, lest it give rise to mockery, the details were not be read out in church.

3 He was one of several military saints honoured in the Byzantine Empire Others included Theodore, Demetrius, and Mercurius.

All of these saints had been soldiers when alive, and continued their patronage of the Byzantine army in death – especially St George, who became the most popular.

Crusaders to the Holy Land in 1099 adopted this tradition of military saints, and brought the veneration of St George back to Western Europe.

4 St George is also connected to agriculture

His name means ‘earth-worker’ – that is, farmer – and his feast day of 23 April is in the spring, when crops are starting to grow. Many people throughout European history have prayed to St George for a good harvest.

5 The dragon was not always a part of St George’s story

The earliest legend that features St George rescuing a princess from a dragon dates to the 11th century. It may have started simply as a way to explain icons of military saints slaying dragons, symbolising the triumph of good over evil.

For the permanent association of St George and the dragon we have to thank the Golden Legend, a popular collection of saints’ lives written in the 13th century.

6 He is the patron saint of many places

These include countries like Ethiopia, Georgia and Portugal, and cities such as Freiburg, Moscow and Beirut. George was seen as an especially powerful intercessor, and the dragon story has a universal appeal.

7 St George was known as ‘Our Lady’s Knight’ in medieval England

As a patron of crusading, St George easily became the quintessential knight. And every knight needs to serve a lady – who better than the Blessed Virgin Mary herself?

8 Edward I is ultimately the reason why St George ‘became’ English

As a crusader, Edward I (r 1272–1307) acquired an affinity for St George, and back in England outfitted his troops with the St George’s cross when fighting the Welsh. He raised St George’s flag over Caerlaverock Castle in Scotland in 1300, among other things.

Later, Edward III, hoping to revive the glories of his grandfather’s reign, founded the Order of the Garter under the patronage of St George.

9 St George appeared to the English army at the battle of Agincourt in 1415

King Henry V (r 1413–22) was especially devoted to St George, as is reflected in Shakespeare’s play. The idea later arose that St George had actually appeared to the English during the battle of Agincourt in 1415, which was a stunning victory for them against the French.

10 The Reformation was not kind to St George

Even King Edward VI himself mocked the legend as improbable. But the poet Edmund Spenser, among others, kept George’s legend alive as a romantic and nationalistic story. And it is one that shows no signs of losing its appeal.

Jonathan Good’s The Cult of St George in Medieval England (Boydell & Brewer) was recently updated, and is now available in paperback.

Published on May 07, 2018 23:30

The Ancient Invention of the Water Clock

Ancient Origins

Today, the ability to keep track of time seems to be taken for granted. One just simply needs to glance at a watch, clock, or mobile phone to know the exact time, even down to the nearest second. Prior to the invention of such battery-operated gadgets, time-keeping was done quite differently.

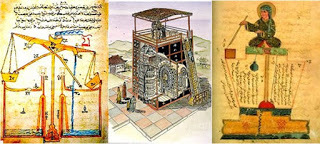

In the ancient world, for instance, sundials were commonly used. This method of measuring time, however, had its flaws. Sundials would, of course, only function when there was sunlight, and they could not maintain a constant division of time. To compensate for these shortcomings, the water clock was invented. Although no one is certain when or where the first water clock was made, the oldest known example is dated to 1500 BC, and is from the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep I. In the ancient world, there were two forms of water clocks: outflow and inflow. In an outflow water clock, the inside of a container was marked with lines of measurement. The container was filled with water, which was allowed to leak out at a steady pace. Observers were able to tell time by measuring the change in water level. An inflow water clock followed the same principle as an outflow one, i.e. the steady dripping of water. Unlike the latter, the former’s measurements were in a second container instead. Based on the amount of water that dripped from the first container, one was able to tell how much time had passed.

Around 325 BC, water clocks began to be used by the Greeks, who called this device the clepsydra (‘water thief’). One of the uses of the water clock in Greece, especially in Athens, was for the timing of speeches in law courts. Some Athenian sources indicate that the water clock was used during the speeches of various well-known Greeks, including Aristotle, Aristophanes the playwright, and Demosthenes the statesman. Apart from timing their speeches, the water clock also prevented their speeches from running too long. Depending on the type of speech or trial that was going on, different amounts of water would be filled into the vessels.

The water clock, however, was not without its flaws. First of all, a constant pressure of water was needed to keep the flow of water at a constant rate. To solve this problem, the water clock was supplied with water from a large reservoir in which the water was kept at a constant level. An example of this can be seen in the ‘Tower of the Winds’ which was built by the Greek astronomer Andronikos in Athens during the 1 st century BC. Still standing, it is an octagonal marble structure 42 feet (12.8 m) high and 26 feet (7.9 m) in diameter. Each of the building’s eight sides faces a point of the compass and is decorated with a frieze of figures in relief representing the winds that blow from that direction; below, on the sides facing the sun, are the lines of a sundial. The Horologium was surmounted by a weather vane in the form of a bronze Triton and contained a water clock (clepsydra) to record the time when the sun was not shining.

The Tower of the Winds, Greece. Photo source: BigStockPhoto

Another problem with the water clock was that as the length of day and night varied with the seasons, it was necessary for the clocks to be calibrated each month. Several solutions were employed to counter this problem. For instance, a disc with 365 holes of varying sizes was used to regulate the flow of water. The largest hole corresponded to the winter solstice, as the day would be shortest, while the smallest hole corresponded to the longest day of the year, the summer solstice. These two holes were at opposite ends of the disk, with the other holes arranged between them in increasing or decreasing sizes. The holes corresponded to the days of the year, and would be rotated by one hole at the end of each day.

Although the fundamental principle of the water is a relatively simple one, there were some challenges related to the physics of water pressure and the changing seasons that the ancients had to deal with, resulting in the water clocks becoming more and more complex over time. When compared to the ease at which we keep track of time today, it seems that we have come quite a long way.

Featured image: Three different depictions of ancient water clocks .

By Ḏḥwty

Published on May 07, 2018 00:00