MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 25

April 5, 2018

The Wight Thing by Elisabeth Marrion - book review

Eight friends meet up after the untimely death of Isabelle´s husband. Having never lost sight of each other since their university days and now retired, they seize the moment and formulate a plan to search for a place where they could all live together. As they embark on this new journey, secrets begin to emerge.

Christine harbours a longing which she has never acted upon, while Steve dreads his next doctor´s appointment. Isabelle is hiding the biggest truth of all, which, if it comes to life, could have devastating consequences.

Is friendship enough to keep them together?

My review

The author has created a delightful story set in England, which focuses on the lives of a group of long-time friends. Although life had taken each of them on different paths, their friendship never falters.

We pick up the story at a time where the children have fled the nest and retirement looms in the distance. It is at this point that the idea of buying a house to accommodate everyone on the Isle of Wight takes center stage.

With careful planning, the lively group visits a variety of available homes on the holiday island. Over the course of a getaway week, we learn about the various issues that threatened the idyllic golden years of these fast friends.

Will the group forge ahead and bring the dream to fruition, or will life, as has happened in the past, cause them to go their separate ways?

No spoilers here. You will fall in love with these characters and will be rooting for them until the very last page. Well done, Ms. Marrion.

Purchase Options:

Amazon US

Amazon UK

About the Author

Elisabeth was born in August 1948 in Hildesheim, Germany. her father was a Corporal in the RAF stationed after WWII in the British occupied zone in Germany, where he met her mother, Hilde.

Elisabeth and her mother shared their love for Art, both were performing at their local theatre from a young age. As a teenager, she enjoyed reading novels and plays by Oscar Wilde, Thornton Wilder, Ernest Hemingway and short stories by Guy de Maupassant. More recently she felt inspired by 'Rabbit-proof fence', a true story written by Doris Pilkington.

In 1969 she moved to England and married David from Liverpool. Together they worked throughout the Far East and Sub Continent, spending a large amount of their time in Bangladesh. There they helped their manufacturer to build a school in the rural part of the Country.

For inspiration, Elisabeth puts on her running shoes for a run through the New Forest.

Published on April 05, 2018 23:30

April 4, 2018

Glastonbury: Archaeology is Revealing New Truths About the Origins of British Christianity

Ancient Origins

Roberta Gilchrist/The Conversation

New archaeological research on Glastonbury Abbey pushes back the date for the earliest settlement of the site by 200 years – and reopens debate on Glastonbury’s origin myths.

Many Christians believe that Glastonbury is the site of the earliest church in Britain, allegedly founded in the first or second century by Joseph of Arimathea. According to the Gospels, Joseph was the man who donated his own tomb for the body of Christ following the crucifixion.

By the 14th century, it was popularly believed that Glastonbury Abbey had been founded by the biblical figure of Joseph. The legend emerged that Joseph had travelled to Britain with the Grail, the vessel used to collect Christ’s blood. For 800 years, Glastonbury has been associated with the romance of King Arthur, the Holy Grail and Joseph of Arimathea. Later stories connected Glastonbury directly to the life of Christ.

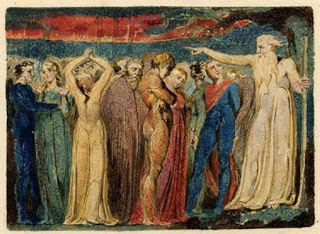

Joseph of Arimathea Preaching to the Inhabitants of Britain. William Blake (via British Museum)

In the 19th century, a popular West Country folk tale claimed that Christ had visited Britain with his great uncle, Joseph of Arimathea, in pursuit of the tin trade. The myth that Jesus visited Glastonbury remains significant for many English Christians today and is immortalised in the country’s unofficial anthem, Sir Hubert Parry’s hymn, Jerusalem, based on William Blake’s 1804 poem.

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On England’s pleasant pastures seen!

Historical accounts describe an “ancient” church on the site in the tenth century. It was still standing in the 12th century, described by the historian William of Malmesbury as “the oldest of all those that I know of in England”. But this revered and ancient church was destroyed by a devastating fire in 1184, along with much of Glastonbury Abbey.

Reconstruction of the old church. Centre for the Study of Christianity, Culture University of York, Author provided

The old church was the first structure to be rebuilt – a new chapel was erected on the site of the old church that had been destroyed by fire. The Lady Chapel that was consecrated in 1186 commemorates the old church and still stands today at Glastonbury Abbey. Any archaeological evidence for an early church would have been destroyed by the later construction of the crypt beneath the Lady Chapel.

Archaeological Evidence

So how can archaeology shed light on the question of Glastonbury’s origins? Research led by the University of Reading has reassessed the full archive of excavations that took place at Glastonbury Abbey throughout the 20th century.

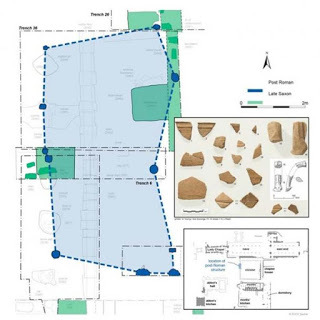

The excavation records confirm that the site of Glastonbury Abbey was occupied before the foundation of the Anglo-Saxon monastery around AD 700. Near the site of the medieval Lady Chapel, there were traces of a timber hall within the bounds of the early monastic cemetery. A roughly trodden floor contained fragments of late Roman amphorae imported from the eastern Mediterranean, dating back to about 450–550AD.

Plan of the post Roman timber structure and associated late Roman amphorae. Liz Gardner, Author provided

A radiocarbon date pinpoints the demolition of the timber building to the eighth or ninth century. This suggests that the building was in use for a long period – extending from the pre-Saxon phase of the site at around 500AD and into the period of the Saxon monastery – potentially up to 300 years.

This new archaeological evidence does not prove the presence of an early church – or support a connection with Joseph of Arimathea. But it does confirm that the Anglo-Saxon monastery was preceded by a high-status settlement dating back to the fifth or sixth century – one with elite trading connections to the eastern Mediterranean. It may also suggest that the Saxon monastery carefully “curated” the timber building – in other words, preserved it for future generations, perhaps because it held special religious or ancestral significance for the monks.

Spiritual Meanings

Today, Glastonbury appeals to a wide range of spiritual seekers, many of whom are drawn by the abbey’s associations with Celtic Christianity. Joseph of Arimathea is important in making the connection to Glastonbury’s Celtic origins – the belief that Joseph founded a church of British Christianity that predated the Roman mission to England (from 597AD).

These archaeological findings are relevant to Glastonbury’s spiritual seekers because they push the origins of the site back to a period before the Anglo-Saxon abbey – into the time of the legendary King Arthur. In a personal letter to the director of Glastonbury Abbey, Geoffrey Ashe – the Arthurian expert and doyen of Glastonbury’s alternative community – commented on the significance of these archaeological findings.

To me, the most gratifying thing is the proof – at last – that the original community was British and existed before the Saxons’ arrival, as I always maintained. The foundation has now been moved back 200 years to the period where it belongs. Brilliant!

The archaeological research provides extensive new insight into Glastonbury Abbey in Anglo-Saxon and medieval times – including digital reconstructions of the Anglo-Saxon churches and the interior of the medieval Lady Chapel. For the first time, Glastonbury’s legendary traditions can be assessed alongside its archaeological evidence.

The Anglo-Saxon Church in its modern setting 1100AD. The Centre for the Study of Christianity & Culture, University of York, Author provided

Archaeology will not prove or disprove Glastonbury’s legendary associations with King Arthur or Joseph of Arimathea. But archaeology helps to explain what these myths meant to medieval people, how the story of Glastonbury has changed over time, and why it remains important to spiritual beliefs today.

Top image: The Lady Chapel, Glastonbury Abbey. Source: Public Domain

This article was originally published under the title ‘Glastonbury: Archaeology is Revealing New Truths About the Origins of British Christianity’ by Roberta Gilchrist on The Conversation, and has been republished under a Creative Commons License.

Published on April 04, 2018 23:30

Is it Better to Die in Battle or to Flee? A Medieval View

Medievalists

How far should a warrior in battle? It has been a question that every soldier has probably thought about, and many have had to face. Even in the Middle Ages this was a question that was debated.

One view comes from Honoré Bonet, a French scholar living around the end of the 14th century. He composed a work in the 1380s called The Tree of Battles, which looked at warfare and how it should be fought. He examined dozens of questions about chivalry, including what were the duties of a good knight, whether a vassal is obliged to aid his lord, and even if priests and clerics should fight in war. In this section, he asks:

Whether a Man should prefer the death to flight from Battle?

Now we must consider a rather difficult question: that is, whether a man ought to choose death, rather than flee from the battle.

I show, first, that he should choose flight in preference to awaiting death, and the reason is this. It is better, according to the philosopher, to choose what gives most delight. It is plain that to live is more agreeable and pleasant than to die, so that it is better to flee than to wait for death. As to the second reason: death is the most terrible and strongest of all things, and hence the most feared; but, since this is not, in the nature of things, a pleasure, it follows that it is not desired; for choice is, influenced by pleasure, and by freedom of choice.

Yet Aristotle, prince of philosophers, holds the contrary, for the following reason: “I say that for nothing in the world should a man do what is dishonourable and reprehensible. But it is plain that to flee is wicked, and brings great reproach and shame.” On this matter I wish to bring forward certain reasons which support the philosopher’s opinion. First, our decrees say that it is better to suffer and sustain all ills rather than consent to evil. But to flee and quit the right is an evil thing. Plainly then, he must by no means flee. A stronger proof is this: of two things a man must choose the better, and: if he does he will have life everlasting. So it is better to remain than to take flight to save the life of this mortal body, which is but meat for worms.

In this discussion I wish to add my own opinion, and it seems to me that if a knight is engaged in battle with Christians against Saracens, and thinks that by his flight he Christians may lose the battle; he must await death rather than take to flight, because he knows he will die for the Faith and be saved. If, on the other hand, he knows that by remaining he will not be helpful to the extent of preventing the loss of the battle, and he finds that he can save himself, and escape the hands of his enemies, I say he should go. If, however, he sees and recognises clearly that flight will not mean escape, indeed he would do better to stay; for it is better that he should await the issue defending himself and others, and die with his comrades, if God permits it, than that in such case he should flee. If a knight is fighting against Christians in his lord’s service, I tell you, as I said before, that he should be willing to die to keep the oath of his faith to his lord. I say the same of the knight in receipt of wages from the king or other lord, for since he has pledged to him his faith and oath he must die in defence of him and his honour; and thus does he maintain in himself the virtue of courage, so that he fears nothing that may befall in fighting for justice.

The entire work has been translated by G.W. Coopland in The Tree of Battles of Honoré Bonet, published by Liverpool University Press in 1949.

Published on April 04, 2018 00:00

April 3, 2018

Huge UK Archaeology Excavations Project Unearths Prehistoric, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Medieval Sites!

Ancient Origins

One of the largest archaeology projects in the UK has revealed Anglo-Saxon settlements, a Roman military camp, remnants of a Medieval village, and a wealth of archaeological treasures. That’s quite a lot for what first appeared as flat Cambridgeshire countryside!

The Guardian reports that 200-plus archaeologists have been working away on “scores of sites on a 21-mile stretch of flat Cambridgeshire countryside, the route of the upgraded A14 and the Huntingdon bypass” over the winter and they will continue to do so through this summer.

Neolithic henge monument under excavation on the A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon scheme. ( Open Government Licence v3.0 )

According to Cambridge News , the team is exploring an area measuring about 1.35 square miles (350 hectares). Altogether, they are undertaking 40 excavations. The features they have found vary from the remnants of Roman pottery kilns to Anglo-Saxon settlements and a Medieval village. Prehistoric burial grounds and henge monuments , as well as a couple of post-medieval brick kilns fill out what was once a very active region.

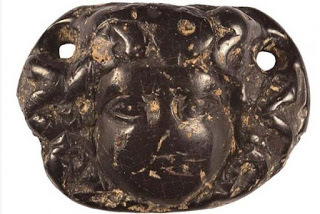

As for artifacts, Cambridge News makes note of seven tons of pottery, 6.5 tons of animal bones, prehistoric flint tools, and more than 7000 small finds such as personal objects. Those personal pieces include a late 2nd to 4th century AD Roman pendant of Medusa which may have been a protective amulet and a rare carved Anglo-Saxon bone flute dated to between the 5th to 9th century AD.

An ornate Roman jet pendant depicting the head of Medusa was found by archaeologists. ( Highways England, courtesy of MOLA Headland ) One surprise find is a well-preserved Middle Iron Age timber ladder from 500 BC. It was placed in a deep pit where archaeologists believe the owner would collect water or stir liquid with a wooden paddle which was discovered nearby.

Steve Sherlock, head archaeologist for Highways England, reflected on the significance of the discoveries so far,

“There is not one key site but a whole expanse – the excavation has given us the whole of the English landscape over the past 6,000 years. The Anglo-Saxon village sites alone are all absolute bobby dazzlers. The larger monuments such as the henges and barrows show up in crop marks and geophysics, but you can only really see things like the post marks of timber buildings by getting down into the ground and digging. The workshops and animal enclosures give you an impression of the hard grind of everyday life, but when you get something like the bone flute you suddenly see into a world that also had art and music, dancing and entertainment.”

Anglo Saxon bone flute. ( Cambridge News )

The Guardian reports the layout of the sites shows that several were placed alongside a Roman road which is now under the A1. However, there are also sites that cluster around the ancient barrows and henges.

Emma Jeffery, senior archaeologist from Mola Headland Infrastructure, has been working on the Medieval village site and had this to say ,

“The medieval village was occupied between the 12th and early 14th centuries, and the most likely explanation for its abandonment was that they lost the use of their woods when they were enclosed as a royal forest. At a stroke they lost their grazing, foraging and bark for uses such as tanning leather, so the economic justification for the village was gone.”

An archaeologist excavates a skeleton in Cambridgeshire. ( Highways England/MOLA Headland Infrastructure )

Cambridgeshire County Council’s senior archaeologist, Kasia Gdaniec, discussed how difficult, yet productive the work has been at the sites:

“The fast-paced archaeological excavations have been extremely challenging, especially during this relentlessly wet winter, but a very large, hardy team of British and international archaeologists successfully completed sites in advance of the road crews taking over to build the road structures. No previous excavation had taken place in these areas, where only a few cropmarked sites indicated the presence of former settlements, but we now know that extensive, thriving long-lived villages were built during the Bronze Age, Iron Age, Roman and Saxon periods.”

Excavating a Roman trade distribution centre on the A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon scheme. ( Open Government Licence v3.0 )

Cambridge News says people can witness the archaeological work in action on the A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon improvement scheme on Saturday, April 7, 2018 between 10am and 5pm. The event is free and includes meeting some of the archaeologists, seeing artifacts found during excavations, and touring one of the dig sites.

Top Image: A Roman chicken brooch unearthed during the excavations. Source: MOLA Headland

By Alicia McDermott

Published on April 03, 2018 00:00

April 2, 2018

The Langeid Viking Battle Axe and a Warrior Who Singlehandedly Held Off the Entire English Army

Ancient Origins

BY THORNEWS

Contrary to what many believe, battle axes from the last part of the Viking age, i.e. the 11th century, had evolved to become light, streamlined, and well-balanced. At the same time, they were powerful lethal weapons, something the recently reconstructed broad axe from Langeid in Southern Norway confirms.

The Viking warrior was well-equipped and trained to use a variety of weapons, but it was undoubtedly the battle axes that created most “shock and awe” among the enemy. Now, the unique weapon found at Langeid in 2011 is recreated, and it confirms that a thousand-year-old rumor is true: Facing a well-trained Norseman with a broad axe was like looking death straight in the eyes.

Viking warrior. (Mark Hooper/CC BY NC SA 2.0)

The Remarkable Grave 8

During archaeological excavations in 2011, several dozen flat graves dating back to the last part of the Viking Age were discovered at Langeid in the Setesdal valley, Southern Norway. The archaeologists found a wooden coffin, but it turned out to be almost empty. However, on the outside they discovered an ornate sword and a battle axe.

The blade was relatively intact, including the toe and heel of the cutting edge. Remarkably, a 15-centimeter (5.91-inch) long wooden stump of the haft was preserved. A band of brass, a metal alloy made of copper and zinc, encircling the stump had preserved the handle due to the antimicrobial properties. X-ray fluorescence analysis confirmed that the band was made of brass, something that made the axe “shine like gold” in the sunlight.

Second Quarter of the 11th Century

The Langeid axe head has a cutting edge of about 25 centimeters (9.84 inches), an original weight of about 800 grams (28.22 ounces) and is clearly two-handed. The haft measured about 110 centimeters (43.31 inches), based upon a few archaeological findings and contemporary illustrations.

According to the archaeologists, the original haft measured about 110 centimeters. (Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo)

The Museum of Cultural History at the University in Oslo only holds six axes of this type – broad axes with brass haft banding.

The Norwegian archaeologist Jan Petersen categorized broad axes as type M in his typology of weapons, appearing from the second half of the 10th century until the Middle Ages.

The Langeid axe has been dated back to the second quarter of the 11th century, which coincides in time with the Battle of Stamford Bridge and perhaps history’s most famous axe warrior.

‘The Battle of Stamford Bridge’ (1870) by Peter Nicolas Arbo. (Public Domain)

The Ultimate Viking Warrior

On 25 September 1066, the battle symbolizing the end of the Viking Age took place at the village of Stamford Bridge, East Riding of Yorkshire, in England. The battle was fought between an English army led by King Harold Godwinson and an invading Norwegian force led by King Harald Sigurdsson “Hardrada” (Old Norse: harðráði, “hard ruler”) and Earl Tostig Godwinson, the English king’s brother.

Historians believe the Norwegian army was divided in two, with some troops on the west side of the River Derwent, and the majority of the army on the east side. The English army caught the Norwegians by surprise and the Norsemen on the west side were either killed or forced to flee across the bridge.

An Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells that a giant Norse axe warrior blocked the narrow crossing and single-handedly held up the entire English army.

Viking warrior with an axe. (Lamin Illustration & Design)

The story is that the Viking cut down as many as 40 English soldiers and was only defeated when an enemy soldier floated under the bridge in a half-barrel and pushed his spear through the planks, mortally wounding the Norseman.

It is not unlikely that the warrior was armed with an axe almost identical with the one found at Langeid in Southern Norway.

The blacksmiths: Vegard Vike and Anders Helseth Nilsson. (Bjarte Aarseth, Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo)

Recently, the impressive Viking axe was reconstructed. You will find detailed information about the project with many photos and videos here.

Top Image: The Langeid Viking Battle Axe: The original and the copy. Source: Vegard Vike, Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo

The article, originally titled ‘The Langeid Viking Battle Axe’ by Thor Lanesskog, was originally published on ThorNews and has been republished with permission.

Published on April 02, 2018 00:00

March 31, 2018

The Ancient Pagan Origins of Easter

Ancient Origins

Easter Sunday is a festival and holiday celebrated by millions of people around the world who honour the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in the New Testament as having occurred three days after his crucifixion at Calvary. It is also the day that children excitedly wait for the Easter bunny to arrive and deliver their treats of chocolate eggs. Easter is a ‘movable feast’ which is chosen to correspond with the first Sunday following the full moon after the March equinox, and occurs on different dates around the world since western churches use the Gregorian calendar, while eastern churches use the Julian calendar. So where did this ‘movable feast’ begin, and what are the origins of the traditions and customs celebrated on this important day around the world?

Christian’s today celebrate Easter Sunday as the resurrection of Jesus. Image source.

Most historians, including Biblical scholars, agree that Easter was originally a pagan festival. According to the New Unger’s Bible Dictionary says: “The word Easter is of Saxon origin, Eastra, the goddess of spring, in whose honour sacrifices were offered about Passover time each year. By the eighth century Anglo–Saxons had adopted the name to designate the celebration of Christ’s resurrection.” However, even among those who maintain that Easter has pagan roots, there is some disagreement over which pagan tradition the festival emerged from. Here we will explore some of those perspectives.

Resurrection as a symbol of rebirth

One theory that has been put forward is that the Easter story of crucifixion and resurrection is symbolic of rebirth and renewal and retells the cycle of the seasons, the death and return of the sun.

According to some scholars, such as Dr. Tony Nugent, teacher of Theology and Religious Studies at Seattle University, and Presbyterian minister, the Easter story comes from the Sumerian legend of Damuzi (Tammuz) and his wife Inanna (Ishtar), an epic myth called “The Descent of Inanna” found inscribed on cuneiform clay tablets dating back to 2100 BC. When Tammuz dies, Ishtar is grief–stricken and follows him to the underworld. In the underworld, she enters through seven gates, and her worldly attire is removed. "Naked and bowed low" she is judged, killed, and then hung on display. In her absence, the earth loses its fertility, crops cease to grow and animals stop reproducing. Unless something is done, all life on earth will end.

After Inanna has been missing for three days her assistant goes to other gods for help. Finally one of them Enki, creates two creatures who carry the plant of life and water of life down to the Underworld, sprinkling them on Inanna and Damuzi, resurrecting them, and giving them the power to return to the earth as the light of the sun for six months. After the six months are up, Tammuz returns to the underworld of the dead, remaining there for another six months, and Ishtar pursues him, prompting the water god to rescue them both. Thus were the cycles of winter death and spring life.

The Descent of Inanna. Image source.

Dr Nugent is quick to point out that drawing parallels between the story of Jesus and the epic of Inanna “doesn't necessarily mean that there wasn't a real person, Jesus, who was crucified, but rather that, if there was, the story about it is structured and embellished in accordance with a pattern that was very ancient and widespread.”

The Sumerian goddess Inanna is known outside of Mesopotamia by her Babylonian name, "Ishtar". In ancient Canaan Ishtar is known as Astarte, and her counterparts in the Greek and Roman pantheons are known as Aphrodite and Venus. In the 4th Century, when Christians identified the exact site in Jerusalem where the empty tomb of Jesus had been located, they selected the spot where a temple of Aphrodite (Astarte/Ishtar/Inanna) stood. The temple was torn down and the So Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built, the holiest church in the Christian world.

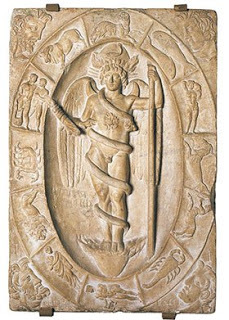

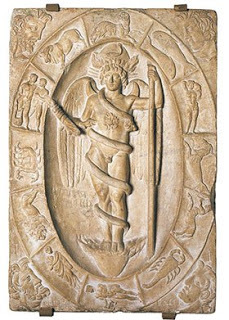

Dr Nugent points out that the story of Inanna and Damuzi is just one of a number of accounts of dying and rising gods that represent the cycle of the seasons and the stars. For example, the resurrection of Egyptian Horus; the story of Mithras, who was worshipped at Springtime; and the tale of Dionysus, resurrected by his grandmother. Among these stories are prevailing themes of fertility, conception, renewal, descent into darkness, and the triumph of light over darkness or good over evil.

Easter as a celebration of the Goddess of Spring

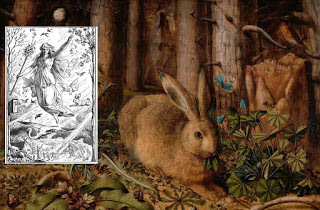

A related perspective is that, rather than being a representation of the story of Ishtar, Easter was originally a celebration of Eostre, goddess of Spring, otherwise known as Ostara, Austra, and Eastre. One of the most revered aspects of Ostara for both ancient and modern observers is a spirit of renewal.

Celebrated at Spring Equinox on March 21, Ostara marks the day when light is equal to darkness, and will continue to grow. As the bringer of light after a long dark winter, the goddess was often depicted with the hare, an animal that represents the arrival of spring as well as the fertility of the season.

According to Jacob Grimm’s Deutsche Mythologie, the idea of resurrection was ingrained within the celebration of Ostara: “Ostara, Eástre seems therefore to have been the divinity of the radiant dawn, of upspringing light, a spectacle that brings joy and blessing, whose meaning could be easily adapted by the resurrection-day of the christian’s God.”

Most analyses of the origin of the word ‘Easter’ maintain that it was named after a goddess mentioned by the 7th to 8th-century English monk Bede, who wrote that Ēosturmōnaþ (Old English 'Month of Ēostre', translated in Bede's time as "Paschal month") was an English month, corresponding to April, which he says "was once called after a goddess of theirs named Ēostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month".

The origins of Easter customs

The most widely-practiced customs on Easter Sunday relate to the symbol of the rabbit (‘Easter bunny’) and the egg. As outlined previously, the rabbit was a symbol associated with Eostre, representing the beginning of Springtime. Likewise, the egg has come to represent Spring, fertility and renewal. In Germanic mythology, it is said that Ostara healed a wounded bird she found in the woods by changing it into a hare. Still partially a bird, the hare showed its gratitude to the goddess by laying eggs as gifts.

The Encyclopedia Britannica clearly explains the pagan traditions associated with the egg: “The egg as a symbol of fertility and of renewed life goes back to the ancient Egyptians and Persians, who had also the custom of colouring and eating eggs during their spring festival.” In ancient Egypt, an egg symbolised the sun, while for the Babylonians, the egg represents the hatching of the Venus Ishtar, who fell from heaven to the Euphrates.

Relief with Phanes, c. 2nd century A.D. Orphic god Phanes emerging from the cosmic egg, surrounded by the zodiac. Image source.

In many Christian traditions, the custom of giving eggs at Easter celebrates new life. Christians remember that Jesus, after dying on the cross, rose from the dead, showing that life could win over death. For Christians the egg is a symbol of Jesus' resurrection, as when they are cracked open, they stand for the empty tomb.

Regardless of the very ancient origins of the symbol of the egg, most people agree that nothing symbolises renewal more perfectly than the egg – round, endless, and full of the promise of life.

While many of the pagan customs associated with the celebration of Spring were at one stage practised alongside Christian Easter traditions, they eventually came to be absorbed within Christianity, as symbols of the resurrection of Jesus. The First Council of Nicaea (325) established the date of Easter as the first Sunday after the full moon (the Paschal Full Moon) following the March equinox.

Whether it is observed as a religious holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus Christ, or a time for families in the northern hemisphere to enjoy the coming of Spring and celebrate with egg decorating and Easter bunnies, the celebration of Easter still retains the same spirit of rebirth and renewal, as it has for thousands of years.

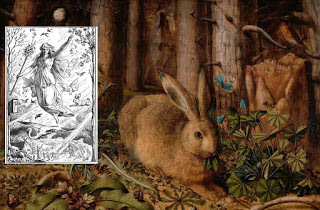

Featured image: Main: ‘A Hare in the Forest by Hans Hoffmann (public domain). Inset: Ostara (1884) by Johannes Gehrts (public domain)

By April Holloway

Easter Sunday is a festival and holiday celebrated by millions of people around the world who honour the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in the New Testament as having occurred three days after his crucifixion at Calvary. It is also the day that children excitedly wait for the Easter bunny to arrive and deliver their treats of chocolate eggs. Easter is a ‘movable feast’ which is chosen to correspond with the first Sunday following the full moon after the March equinox, and occurs on different dates around the world since western churches use the Gregorian calendar, while eastern churches use the Julian calendar. So where did this ‘movable feast’ begin, and what are the origins of the traditions and customs celebrated on this important day around the world?

Christian’s today celebrate Easter Sunday as the resurrection of Jesus. Image source.

Most historians, including Biblical scholars, agree that Easter was originally a pagan festival. According to the New Unger’s Bible Dictionary says: “The word Easter is of Saxon origin, Eastra, the goddess of spring, in whose honour sacrifices were offered about Passover time each year. By the eighth century Anglo–Saxons had adopted the name to designate the celebration of Christ’s resurrection.” However, even among those who maintain that Easter has pagan roots, there is some disagreement over which pagan tradition the festival emerged from. Here we will explore some of those perspectives.

Resurrection as a symbol of rebirth

One theory that has been put forward is that the Easter story of crucifixion and resurrection is symbolic of rebirth and renewal and retells the cycle of the seasons, the death and return of the sun.

According to some scholars, such as Dr. Tony Nugent, teacher of Theology and Religious Studies at Seattle University, and Presbyterian minister, the Easter story comes from the Sumerian legend of Damuzi (Tammuz) and his wife Inanna (Ishtar), an epic myth called “The Descent of Inanna” found inscribed on cuneiform clay tablets dating back to 2100 BC. When Tammuz dies, Ishtar is grief–stricken and follows him to the underworld. In the underworld, she enters through seven gates, and her worldly attire is removed. "Naked and bowed low" she is judged, killed, and then hung on display. In her absence, the earth loses its fertility, crops cease to grow and animals stop reproducing. Unless something is done, all life on earth will end.

After Inanna has been missing for three days her assistant goes to other gods for help. Finally one of them Enki, creates two creatures who carry the plant of life and water of life down to the Underworld, sprinkling them on Inanna and Damuzi, resurrecting them, and giving them the power to return to the earth as the light of the sun for six months. After the six months are up, Tammuz returns to the underworld of the dead, remaining there for another six months, and Ishtar pursues him, prompting the water god to rescue them both. Thus were the cycles of winter death and spring life.

The Descent of Inanna. Image source.

Dr Nugent is quick to point out that drawing parallels between the story of Jesus and the epic of Inanna “doesn't necessarily mean that there wasn't a real person, Jesus, who was crucified, but rather that, if there was, the story about it is structured and embellished in accordance with a pattern that was very ancient and widespread.”

The Sumerian goddess Inanna is known outside of Mesopotamia by her Babylonian name, "Ishtar". In ancient Canaan Ishtar is known as Astarte, and her counterparts in the Greek and Roman pantheons are known as Aphrodite and Venus. In the 4th Century, when Christians identified the exact site in Jerusalem where the empty tomb of Jesus had been located, they selected the spot where a temple of Aphrodite (Astarte/Ishtar/Inanna) stood. The temple was torn down and the So Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built, the holiest church in the Christian world.

Dr Nugent points out that the story of Inanna and Damuzi is just one of a number of accounts of dying and rising gods that represent the cycle of the seasons and the stars. For example, the resurrection of Egyptian Horus; the story of Mithras, who was worshipped at Springtime; and the tale of Dionysus, resurrected by his grandmother. Among these stories are prevailing themes of fertility, conception, renewal, descent into darkness, and the triumph of light over darkness or good over evil.

Easter as a celebration of the Goddess of Spring

A related perspective is that, rather than being a representation of the story of Ishtar, Easter was originally a celebration of Eostre, goddess of Spring, otherwise known as Ostara, Austra, and Eastre. One of the most revered aspects of Ostara for both ancient and modern observers is a spirit of renewal.

Celebrated at Spring Equinox on March 21, Ostara marks the day when light is equal to darkness, and will continue to grow. As the bringer of light after a long dark winter, the goddess was often depicted with the hare, an animal that represents the arrival of spring as well as the fertility of the season.

According to Jacob Grimm’s Deutsche Mythologie, the idea of resurrection was ingrained within the celebration of Ostara: “Ostara, Eástre seems therefore to have been the divinity of the radiant dawn, of upspringing light, a spectacle that brings joy and blessing, whose meaning could be easily adapted by the resurrection-day of the christian’s God.”

Most analyses of the origin of the word ‘Easter’ maintain that it was named after a goddess mentioned by the 7th to 8th-century English monk Bede, who wrote that Ēosturmōnaþ (Old English 'Month of Ēostre', translated in Bede's time as "Paschal month") was an English month, corresponding to April, which he says "was once called after a goddess of theirs named Ēostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month".

The origins of Easter customs

The most widely-practiced customs on Easter Sunday relate to the symbol of the rabbit (‘Easter bunny’) and the egg. As outlined previously, the rabbit was a symbol associated with Eostre, representing the beginning of Springtime. Likewise, the egg has come to represent Spring, fertility and renewal. In Germanic mythology, it is said that Ostara healed a wounded bird she found in the woods by changing it into a hare. Still partially a bird, the hare showed its gratitude to the goddess by laying eggs as gifts.

The Encyclopedia Britannica clearly explains the pagan traditions associated with the egg: “The egg as a symbol of fertility and of renewed life goes back to the ancient Egyptians and Persians, who had also the custom of colouring and eating eggs during their spring festival.” In ancient Egypt, an egg symbolised the sun, while for the Babylonians, the egg represents the hatching of the Venus Ishtar, who fell from heaven to the Euphrates.

Relief with Phanes, c. 2nd century A.D. Orphic god Phanes emerging from the cosmic egg, surrounded by the zodiac. Image source.

In many Christian traditions, the custom of giving eggs at Easter celebrates new life. Christians remember that Jesus, after dying on the cross, rose from the dead, showing that life could win over death. For Christians the egg is a symbol of Jesus' resurrection, as when they are cracked open, they stand for the empty tomb.

Regardless of the very ancient origins of the symbol of the egg, most people agree that nothing symbolises renewal more perfectly than the egg – round, endless, and full of the promise of life.

While many of the pagan customs associated with the celebration of Spring were at one stage practised alongside Christian Easter traditions, they eventually came to be absorbed within Christianity, as symbols of the resurrection of Jesus. The First Council of Nicaea (325) established the date of Easter as the first Sunday after the full moon (the Paschal Full Moon) following the March equinox.

Whether it is observed as a religious holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus Christ, or a time for families in the northern hemisphere to enjoy the coming of Spring and celebrate with egg decorating and Easter bunnies, the celebration of Easter still retains the same spirit of rebirth and renewal, as it has for thousands of years.

Featured image: Main: ‘A Hare in the Forest by Hans Hoffmann (public domain). Inset: Ostara (1884) by Johannes Gehrts (public domain)

By April Holloway

Published on March 31, 2018 23:00

Medieval Forensics: Investigating the Death of a Byzantine Emperor

Medievalists

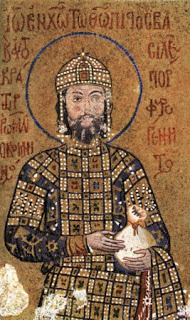

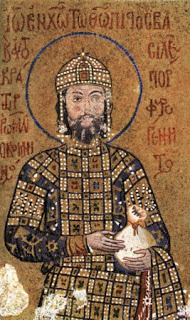

Mosaic of John II Komnenos in the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

Mosaic of John II Komnenos in the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

John II Komnenos (1087-1143) was an accomplished and successful medieval ruler whose death has long been the subject of scholarly discussion. While out hunting, John was allegedly poisoned by an arrow – but was this really the cause of the emperor’s death? Mosaic of John II Komnenos in the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

A new article by the research team of Konstantinos Markatos (Biomedical Research Foundation of the Academy of Athens), Anastasia Papaioannou (Kapandriti Medical Center, Oropos, Athens), Marianna Karamanou (History of Medicine Department, Medical School, University of Crete), and Georgios Androutsos (Biomedical Research Foundation of the Academy of Athens) uses primary sources and modern medicine to take a fresh look at this medieval cold case.

The article, ‘The death of the Byzantine Emperor John II Komnenos (1087–1143)’, begins by taking a brief look at the life and reign of John II. The eldest son of the emperor Alexios I Komnenos, at the time of his ascension John had to overcome an attempted coup by his younger brother Isaac. Despite this uncertain beginning, over his twenty-five year reign John went on to become a strong military and political ruler of the Byzantine Empire.

In 1142, John launched a military expedition to Syria in an effort to reconquer the city of Antioch, currently held by Raymond of Poitiers. While out hunting boar in the spring of 1143, as the army was getting ready to leave its winter quarters, John received a superficial injury from a poisoned arrow he carried. Just over a week later, the emperor was dead.

According to the authors, ‘The events surrounding the death of John Komnenos are mainly derived from the accounts of the historians of the twelfth century Byzantine Empire John Cinnamos and Niketas Choniates‘, and, ‘Both historians attribute the death of the emperor to the effects of the poison that the arrow carried‘.

Critically, however, in their efforts to investigate these accounts, the authors are quick to acknowledge the risks of retrospective diagnosis: ‘First of all, one should point out that every search concerning the cause or type of disease in ancient periods is always hypothetical and controversial, and therefore should be addressed with utmost care.’

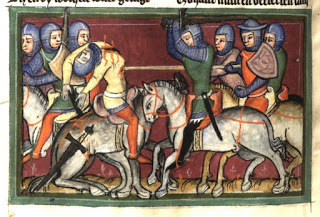

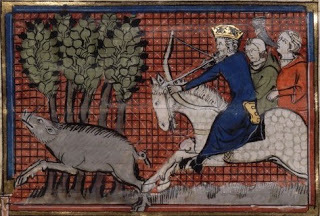

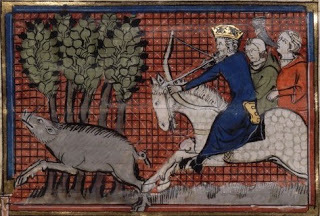

John II hunting boar in a 14th century French manuscipt (BnF, Francais 22495)

A close analysis of poisons, especially serpent venom, used in such situations and their common effects leads to the conclusion that the immediate symptoms did not present themselves in John II’s case. ‘On the contrary, the long period of time before the presentation of symptoms should be attributed to their being caused by an infection.’ The long delay between the emperor’s supposed poisoning and his death, the authors hypothesise, point toward septicaemia. Foul play is further ruled out, due to the fact that John II’s heir, his son Immanuel, was already the preferred choice of the Byzantine nobility.

Still, as with all cases of medieval medical mystery, the fact remains that ‘it must be stressed out that this conclusion is strictly based on historical testimonies of the era; hard scientific evidence in the contemporary sense to support such a conclusion is missing and it is highly unlikely to be obtained in the future.’

‘The death of the Byzantine Emperor John II Komnenos (1087–1143)’ appears in the journal Acta Chirurgica Belgica, published online 01 February 2018.

BY NATALIE ANDERSON

Mosaic of John II Komnenos in the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

Mosaic of John II Komnenos in the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul. John II Komnenos (1087-1143) was an accomplished and successful medieval ruler whose death has long been the subject of scholarly discussion. While out hunting, John was allegedly poisoned by an arrow – but was this really the cause of the emperor’s death? Mosaic of John II Komnenos in the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul.

A new article by the research team of Konstantinos Markatos (Biomedical Research Foundation of the Academy of Athens), Anastasia Papaioannou (Kapandriti Medical Center, Oropos, Athens), Marianna Karamanou (History of Medicine Department, Medical School, University of Crete), and Georgios Androutsos (Biomedical Research Foundation of the Academy of Athens) uses primary sources and modern medicine to take a fresh look at this medieval cold case.

The article, ‘The death of the Byzantine Emperor John II Komnenos (1087–1143)’, begins by taking a brief look at the life and reign of John II. The eldest son of the emperor Alexios I Komnenos, at the time of his ascension John had to overcome an attempted coup by his younger brother Isaac. Despite this uncertain beginning, over his twenty-five year reign John went on to become a strong military and political ruler of the Byzantine Empire.

In 1142, John launched a military expedition to Syria in an effort to reconquer the city of Antioch, currently held by Raymond of Poitiers. While out hunting boar in the spring of 1143, as the army was getting ready to leave its winter quarters, John received a superficial injury from a poisoned arrow he carried. Just over a week later, the emperor was dead.

According to the authors, ‘The events surrounding the death of John Komnenos are mainly derived from the accounts of the historians of the twelfth century Byzantine Empire John Cinnamos and Niketas Choniates‘, and, ‘Both historians attribute the death of the emperor to the effects of the poison that the arrow carried‘.

Critically, however, in their efforts to investigate these accounts, the authors are quick to acknowledge the risks of retrospective diagnosis: ‘First of all, one should point out that every search concerning the cause or type of disease in ancient periods is always hypothetical and controversial, and therefore should be addressed with utmost care.’

John II hunting boar in a 14th century French manuscipt (BnF, Francais 22495)

A close analysis of poisons, especially serpent venom, used in such situations and their common effects leads to the conclusion that the immediate symptoms did not present themselves in John II’s case. ‘On the contrary, the long period of time before the presentation of symptoms should be attributed to their being caused by an infection.’ The long delay between the emperor’s supposed poisoning and his death, the authors hypothesise, point toward septicaemia. Foul play is further ruled out, due to the fact that John II’s heir, his son Immanuel, was already the preferred choice of the Byzantine nobility.

Still, as with all cases of medieval medical mystery, the fact remains that ‘it must be stressed out that this conclusion is strictly based on historical testimonies of the era; hard scientific evidence in the contemporary sense to support such a conclusion is missing and it is highly unlikely to be obtained in the future.’

‘The death of the Byzantine Emperor John II Komnenos (1087–1143)’ appears in the journal Acta Chirurgica Belgica, published online 01 February 2018.

BY NATALIE ANDERSON

Published on March 31, 2018 00:00

March 29, 2018

1,000-Year-Old Norman Cathedral Ruins Unearthed Beneath Church in England

Ancient Origins

The foundations of a Norman cathedral have been found under just 3ft (90cm) of soil during excavations at St Albans Abbey, the oldest place of continuous Christian worship in England. They are dated to 1077AD, making it one of the earliest Norman cathedrals in the country.

The BBC reports that the exciting discovery was made during excavation work being carried out by the Canterbury Archaeological Trust to prepare the site for the construction of a new visitor center.

"We've only gone about a metre down but everything's happened there - there's 1,000 years of history in a metre of earth," site director Ross Lane told the BBC.

During excavations, archaeologists found the remains of two massive apse-ended chapels, which are intrinsic to the Norman cathedral design. The apse is a large semi-circular recess, usually at one or both ends of a church, with an arched or domed roof.

St Albans Abbey – A Site of Martyrdom

St Albans Abbey, which is now officially a cathedral, is the oldest site of continuous Christian worship in Britain. It sits on the site where Alban was buried and made into a martyr after he was tortured and beheaded sometime during the 3rd or 4th century by Romans for sheltering a Christian priest at a time when Christians were facing heavy persecution.

St Albans Cathedral viewed from the west in Hertfordshire, England (CC by SA 3.0)

It is believed that the cathedral was built on the site of his execution, and a well at the bottom of the hill, Holywell Hill, is said to be the place where Alban’s head landed after rolling downhill.

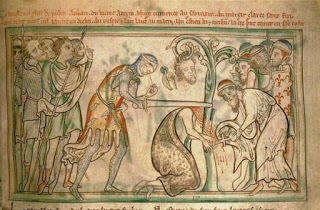

The martyrdom of St Alban, from a 13th-century manuscript, now in the Trinity College Library, Dublin. Note the executioner's eyes falling out of his head. (public domain)

Symbols of Power: The Norman Cathedrals of England

The newly discovered cathedral beneath St Albans Abbey is one of only fifteen cathedrals built across Britain, and is one of the oldest, its construction completed just 11 years after the Normans invaded England in 1066 AD. After William the Conqueror began stamping his authority across his newly conquered kingdom, the ecclesiastical soon followed suit, eager to establish the superiority of Norman French culture and sophistication.

“Norman England was soon experiencing a building boom never before seen across the land,” writes Almost History. “Construction commenced on at least fifteen great cathedrals and all but two survive to this day.”

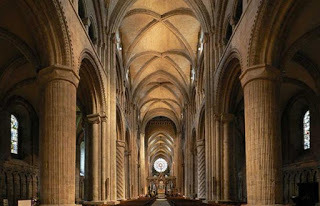

The cathedrals were built in the Romanesque style developed by the Normans in the 11th century, characterized by massive proportions, rounded arches over windows and doorways, a raised nave and a western façade completed by two towers.

The nave of Durham Cathedral (CC by SA 3.0)

Ancient Burials

The archaeological dig also yielded 20 burials, some of which were substantial tombs, dating to the 11th and 12th centuries. The graves would have belonged to some of the original inhabitants and benefactors of the Abbey. Research is now being conducted to try to identify who they were.

Top image: Remains of the original apse built in 1077 was unearthed during excavation work at St Albans Cathedral. Credit: St Albans Cathedral

By April Holloway

Published on March 29, 2018 23:30

Not Just at The End of Rainbows: 15th Century Pot of Gold Found in a Drain Pipe in the Netherlands

Ancient Origins

It wasn’t just an ordinary day at work for employees of a water company in the Netherlands, who earlier this month stumbled upon an earthenware cooking pot containing around 500 gold and silver coins dating to the 15 th century while laying pipes at a building site.

Dutch News reports that the treasure was discovered during building work for a new town being developed between Vianen and Hagestein in the province of Utrecht, and may shed new light on what occurred in the medieval town of Hagestein after it was destroyed in 1405.

Dr Boer explained that during the time the coins were in circulation, the Netherlands was ruled by a French noble family, the ‘Dukes of Burgundy’, who had deep ties to France's royal family. However, there remain many gaps in the knowledge of this time period, particularly in the aftermath of the violent destruction of Hagestein, near where the coins were discovered.

“‘We now have a pot full of stories,” archaeologist Peter De Boer told NOS. "Every gentleman gave out his 'business card' by way of a coin, and therefore there is a lot to discover. Stories over power relations, religion and a lot of symbolism."

Hoe fen Haag, a new town being developed in Utrecht ( CC by SA 4.0 / Jan Diijkstra )

Pot of Gold

An analysis of the coins revealed that twelve of them were solid gold, while the rest are silver. The true value has not yet been determined, but the owners of the water company Oasen, the project developer, and the land owner where the treasure was found, are likely to do quite well.

“Some textiles were also found in the pot, indicating that the coins were packed in fabric bags or cloths,” reports NL Times . “Most of the coins seem to date from the 1470's and 1480's. Some of the coins show King Henri VI of England, Bishop of Utrecht David of Burgundy, and Pope Paul II.”

The joint owners of the coins have temporarily let go of the coins so they can be studied, and they will then decide what they wish to do with them.

It’s not the first time a pot of treasure has been discovered by some lucky finder. In 1993, two amateur treasure hunters found a collection of over 4,000 Roman coins in a pot in Lincolnshire, England, and in 2015, two clay pots were found by forestry workers in Poland , containing a hoard of more than 6,000 coins. There may not be golden treasures at the end of every rainbow, but pots of gold are still to be found!

Top image: 15th century gold and silver coins found in the Netherlands. Credit: Oasen

By April Holloway

It wasn’t just an ordinary day at work for employees of a water company in the Netherlands, who earlier this month stumbled upon an earthenware cooking pot containing around 500 gold and silver coins dating to the 15 th century while laying pipes at a building site.

Dutch News reports that the treasure was discovered during building work for a new town being developed between Vianen and Hagestein in the province of Utrecht, and may shed new light on what occurred in the medieval town of Hagestein after it was destroyed in 1405.

Dr Boer explained that during the time the coins were in circulation, the Netherlands was ruled by a French noble family, the ‘Dukes of Burgundy’, who had deep ties to France's royal family. However, there remain many gaps in the knowledge of this time period, particularly in the aftermath of the violent destruction of Hagestein, near where the coins were discovered.

“‘We now have a pot full of stories,” archaeologist Peter De Boer told NOS. "Every gentleman gave out his 'business card' by way of a coin, and therefore there is a lot to discover. Stories over power relations, religion and a lot of symbolism."

Hoe fen Haag, a new town being developed in Utrecht ( CC by SA 4.0 / Jan Diijkstra )

Pot of Gold

An analysis of the coins revealed that twelve of them were solid gold, while the rest are silver. The true value has not yet been determined, but the owners of the water company Oasen, the project developer, and the land owner where the treasure was found, are likely to do quite well.

“Some textiles were also found in the pot, indicating that the coins were packed in fabric bags or cloths,” reports NL Times . “Most of the coins seem to date from the 1470's and 1480's. Some of the coins show King Henri VI of England, Bishop of Utrecht David of Burgundy, and Pope Paul II.”

The joint owners of the coins have temporarily let go of the coins so they can be studied, and they will then decide what they wish to do with them.

It’s not the first time a pot of treasure has been discovered by some lucky finder. In 1993, two amateur treasure hunters found a collection of over 4,000 Roman coins in a pot in Lincolnshire, England, and in 2015, two clay pots were found by forestry workers in Poland , containing a hoard of more than 6,000 coins. There may not be golden treasures at the end of every rainbow, but pots of gold are still to be found!

Top image: 15th century gold and silver coins found in the Netherlands. Credit: Oasen

By April Holloway

Published on March 29, 2018 00:00

March 27, 2018

Underwater Archaeologists Discover Submerged Ruins off the Coast of Naples

Ancient Origins

Back in September 2017, underwater archaeologists met a decade-long goal in discovering the submerged ruins of the port of Neapolis. Now, they have identified the location of the port which preceded it, Palepolis, a site the Greeks wrested from the Etruscans some 3000 years ago. Today, Palepolis is known as Naples.

ANSA reports researchers have identified the submerged ruins of Palepolis near the Castel dell'Ovo in Naples. To date, underwater archaeologists have discovered four tunnels, a defense trench probably used by soldiers, and a street still marked by the carts which passed over it so long ago. The Local says exploration will continue under the waves until May 2018.

One of the submerged tunnels. (Elisa Manacorda/Reptv)

Mario Negri of the International University of Languages and Media (IULM) in Milan, the organization which funded the research, says “It's a discovery that opens up a new scenario for reconstructing the ancient structure of Palepolis.”

However, Negri seems somewhat hesitant in declaring too much too soon, because he has also said that the ruins, “could – I stress, could – be the archeological traces of Naples' first port, which means we are right at the founding moment of this extraordinary city.”

Others are looking to future possibilities, such as Luciano Garella, who directs Naples’ institution in charge of archaeological heritage, who sees an exciting option on the horizon, “We'll have to explore a different type of tourism – underwater tourism,” he said.

But what made Palepolis special? What’s its history?

Comune.napoli.it states that the earliest settlements in the area date back some 3000 years, “when “Anatolian and Achaean merchants and travellers arrived in the gulf on their way to the mineral lands of the high Tyrrhene.” They founded Parthenope, a small harbor which gradually expanded through business, but was consistently in the midst of battles between the Etruscans and Greeks.

Etruscan warrior, found near Viterbo, Italy, dated c. 500 BC. (CC BY SA 3.0)

The Greeks eventually conquered the port and renamed it Palepolis in about 474 BC. Soon after, Palepolis was outshined by a new city, Neapolis, which was built by the Greeks to the south.

As Archaeology points out, patrician villas became the main focus of Palepolis by the time the Romans took control. The town had been transformed into something of a suburb for Neapolis; a location where residents had some peace and quiet without setting themselves too far from the bustling city.

The submerged ruins of Neapolis were only discovered in September 2017.The underwater component of the city stretches over 20 hectares (almost 50 acres). As some of Neapolis’ ruins remain aboveground, underwater archaeologists had been searching the region for the last seven years in hope of finding the submerged counterpart. Neapolis was partially submerged by a tsunami on July 21 in 365 AD, a natural disaster that also damaged Alexandria in Egypt and Greece’s island of Crete.

Underwater archaeologists have discovered monuments, streets, and about 100 tanks that were used in the production of a fermented fish condiment known as garum at Neapolis. Mounir Fantar, the head of a Tunisian-Italian archaeological mission said: “This discovery has allowed us to establish with certainty that Neapolis was a major center for the manufacture of garum and salt fish, probably the largest center in the Roman world. Probably the notables of Neapolis owed their fortune to garum.”

Today, visitors interested in the earliest days of Palepolis, and pre-Palepolis times, can find remnants of a necropolis dating back to when the settlement was known as Parthenope and a few indications left of a Roman villa built by a nobleman named Lucullo. For the most part, Comune.napoli.it says Palepolis has been overtaken by later building projects, such as “Castel dell'Ovo on the isle of Megaride, and by luxury housing, hotels and shops.”

Castel dell'Ovo, Naples. (Public Domain)

Top Image: Ruins of the ancient submerged port of Palepolis off the coast of Naples. Source: Elisa Manacorda/Reptv

By Alicia McDermott

Published on March 27, 2018 23:30