MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 24

April 16, 2018

Greek mythology and human origins

Ancient Origins

Greek mythology begins with the Creation Myth , which is contained within many different sources of ancient Greek texts. The most complete one is Theogony from the Greek poet Hesiod, who lived around the 8 th century BCE. Hesiod combines all Greek myths and traditions to create this mythical cosmogony.

According to Theogony, in the beginning only chaos and void existed throughout the entire universe (The Greek word chaos does not have the same meaning in which it is used today, but simply meant empty space or a dark void.).

Chaos was followed by Gaia (which means earth) and Eros (which is love). It is not specified if Gaia and Eros were born from Chaos or whether they were pre-existing; however, Hesiod mentions that Gaia (Earth) came into existence in order to become the home of the gods. This is similar to other myths, like Sumerian myths, which describe how the earth was initially created for the gods to dwell.

Chaos also gave birth to Erebus, who was the darkness of the underworld, and Nyx (night).

Gaia gave birth to Uranus (heavens) and Okeanos (ocean).

The story continues showing how the gods mated with each other to complete the whole of creation. Nyx and Erebus mated, and Hemere (day) and Aether (air) were born. Nyx also gave birth to other gods like Moros, Thanatos (death), Nemesis, Hypnos (sleep), Eris and Keres.

Uranus and Gaia became the first gods to rule. Uranus then mated with Gaia and produced Cyclopes and the twelve Titans (a race of giants). One of the Titans was Cronus (Saturn).

And from here the pantheon of the famous gods of Greek mythology begins.

Uranus was jealous of his children and condemned them to stay in the womb of Gaia; however, Gaia, with the help of Cronus, punishes Uranus by castrating him. His genitals and his blood fell into Earth and created another set of gods—Aphrodite, Erinyes, giants and nymphs.

Uranus and Gaia spoke a prophecy to Cronus, telling him that one of his sons would overpower him. As a result, Cronus decided to swallow their children. Gaia was able to save baby Zeus (Jupiter), who was raised on the Greek island Crete until he, with the help of Metis (another Titan), made Cronus to regurgitate the swallowed children. Led by Zues, the six brothers and sisters (Demeter, Hera, Hestia, Hades and Poseidon) rebelled against their father against whom they were victorious, throwing Cronus forever into the Tartarus (the dark world under Earth).

After that, the rebel gods of ancient Greece divided the universe between them. Zeus was the supreme god, ruling over all others, and all of them lived on the peak of Mount Olympus in Greece.

Greek mythology is full of fights between the gods, similar to other myths and religions—and so far we still have not seen the creation of man.

In the above mentioned battle, three Titans did not support Cronus: Prometheus, Epimetheus and Okeanos. Prometheus later joined Zeus. All the Titans were sent into Tartarus (the underworld), with the exception of Prometheus and Epimetheus.

Prometheus was the one to create man out of earth (mud), and the goddess Athena breathed life into the man. Here we see another common pattern repeating in the creation, where the spirit is given to the body so that it will become alive.

Epimetheus was the one to whom Prometheus assigned the duty to give all living creatures of the planet different qualities/skills; however, Epimetheus had already given all the good skills and qualities to other creatures, and nothing was left for man. Consequently, Prometheus made man to stand upright—as only the gods had done—and gave him fire.

This made Zeus angry because he was not very fond of man, though man was Prometheus’s favourite creation. Zeus thus decreed that man must present a portion of each animal they sacrificed to the gods, but Prometheus tricked Zeus and, as a result, Zeus took fire away from man. Prometheus then stole fire back and returned it to man. For that Zeus punished both man and Prometheus.

The punishment that Zeus inflicted to man was to create Pandora (with the help of god Hephaestus), the first woman. He gave Pandora as a gift a box that she was not allowed to open. The box was full of misfortunes, diseases and plagues, while at the bottom of the box there was also hope.

Prometheus was condemned to be tormented on the Caucasus Mountain where he was chained on a rock in unbreakable chains. Every night an eagle would appear and eat his liver. During the day the liver was reborn, and every night the eagle would return and eat it again.

Later on a Centaur, Chiron, and a semi-god, Hercules, would release Prometheus from his torment.

It is clear that Greek mythology contains parallels to other mythologies and religions, such as water being the beginning of all life, the on-going fighting between gods and, most importantly, the denial of the gods to allow humans to have knowledge.

By John Black

Greek mythology begins with the Creation Myth , which is contained within many different sources of ancient Greek texts. The most complete one is Theogony from the Greek poet Hesiod, who lived around the 8 th century BCE. Hesiod combines all Greek myths and traditions to create this mythical cosmogony.

According to Theogony, in the beginning only chaos and void existed throughout the entire universe (The Greek word chaos does not have the same meaning in which it is used today, but simply meant empty space or a dark void.).

Chaos was followed by Gaia (which means earth) and Eros (which is love). It is not specified if Gaia and Eros were born from Chaos or whether they were pre-existing; however, Hesiod mentions that Gaia (Earth) came into existence in order to become the home of the gods. This is similar to other myths, like Sumerian myths, which describe how the earth was initially created for the gods to dwell.

Chaos also gave birth to Erebus, who was the darkness of the underworld, and Nyx (night).

Gaia gave birth to Uranus (heavens) and Okeanos (ocean).

The story continues showing how the gods mated with each other to complete the whole of creation. Nyx and Erebus mated, and Hemere (day) and Aether (air) were born. Nyx also gave birth to other gods like Moros, Thanatos (death), Nemesis, Hypnos (sleep), Eris and Keres.

Uranus and Gaia became the first gods to rule. Uranus then mated with Gaia and produced Cyclopes and the twelve Titans (a race of giants). One of the Titans was Cronus (Saturn).

And from here the pantheon of the famous gods of Greek mythology begins.

Uranus was jealous of his children and condemned them to stay in the womb of Gaia; however, Gaia, with the help of Cronus, punishes Uranus by castrating him. His genitals and his blood fell into Earth and created another set of gods—Aphrodite, Erinyes, giants and nymphs.

Uranus and Gaia spoke a prophecy to Cronus, telling him that one of his sons would overpower him. As a result, Cronus decided to swallow their children. Gaia was able to save baby Zeus (Jupiter), who was raised on the Greek island Crete until he, with the help of Metis (another Titan), made Cronus to regurgitate the swallowed children. Led by Zues, the six brothers and sisters (Demeter, Hera, Hestia, Hades and Poseidon) rebelled against their father against whom they were victorious, throwing Cronus forever into the Tartarus (the dark world under Earth).

After that, the rebel gods of ancient Greece divided the universe between them. Zeus was the supreme god, ruling over all others, and all of them lived on the peak of Mount Olympus in Greece.

Greek mythology is full of fights between the gods, similar to other myths and religions—and so far we still have not seen the creation of man.

In the above mentioned battle, three Titans did not support Cronus: Prometheus, Epimetheus and Okeanos. Prometheus later joined Zeus. All the Titans were sent into Tartarus (the underworld), with the exception of Prometheus and Epimetheus.

Prometheus was the one to create man out of earth (mud), and the goddess Athena breathed life into the man. Here we see another common pattern repeating in the creation, where the spirit is given to the body so that it will become alive.

Epimetheus was the one to whom Prometheus assigned the duty to give all living creatures of the planet different qualities/skills; however, Epimetheus had already given all the good skills and qualities to other creatures, and nothing was left for man. Consequently, Prometheus made man to stand upright—as only the gods had done—and gave him fire.

This made Zeus angry because he was not very fond of man, though man was Prometheus’s favourite creation. Zeus thus decreed that man must present a portion of each animal they sacrificed to the gods, but Prometheus tricked Zeus and, as a result, Zeus took fire away from man. Prometheus then stole fire back and returned it to man. For that Zeus punished both man and Prometheus.

The punishment that Zeus inflicted to man was to create Pandora (with the help of god Hephaestus), the first woman. He gave Pandora as a gift a box that she was not allowed to open. The box was full of misfortunes, diseases and plagues, while at the bottom of the box there was also hope.

Prometheus was condemned to be tormented on the Caucasus Mountain where he was chained on a rock in unbreakable chains. Every night an eagle would appear and eat his liver. During the day the liver was reborn, and every night the eagle would return and eat it again.

Later on a Centaur, Chiron, and a semi-god, Hercules, would release Prometheus from his torment.

It is clear that Greek mythology contains parallels to other mythologies and religions, such as water being the beginning of all life, the on-going fighting between gods and, most importantly, the denial of the gods to allow humans to have knowledge.

By John Black

Published on April 16, 2018 00:00

April 14, 2018

Catapult: The Long-Reaching History of a Prominent Medieval Siege Engine

Ancient Origins

One of the most iconic images of the European Middle Ages is the castle. This defensive structure was often heavily fortified and provided its inhabitants with much-needed safety. It was usually quite difficult for an enemy to capture a castle, and for that, an attacking army needed siege engines. One of the most important and efficient siege engines was the catapult.

The Roman Onager

The catapult was a weapon used since ancient times. In its most basic form, the catapult may be described as a “one-armed stone thrower”. In the Roman world, a catapult-like siege engine known as the ‘onager’ (meaning ‘wild ass’) was used when the Romans were besieging an enemy. One suggestion for this name’s origins is that the Romans likened the stones that were hurled by the catapult to the rocks kicked up behind galloping hooves. An alternate suggestion is that the device jumped when it fired its projectiles. Another type of catapult, which had a sling, was known as the ‘scorpion’, as a shot from this device is reported to resemble the movement of a scorpion’s tail.

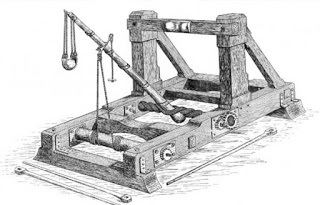

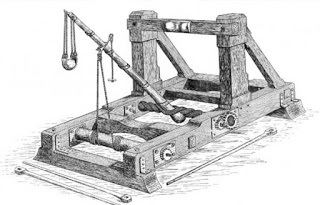

A Roman onager with sling (‘Scorpion’). ( Public Domain )

Chinese Traction Catapults

The use of catapults, however, was not limited to the Roman army. There are records which show that the catapult was also employed by the armies of ancient China as well. For example, during the early Spring and Autumn period (8th – 7th centuries BC), there was a machine called a ‘hui’ that was used by the King of Zhou against the Duke of Zheng during a battle in 707 BC. As the word ‘hui’ no longer exists, we cannot be completely sure of its meaning. Nevertheless, scholars from the Han Dynasty interpreted this device as a catapult.

A clearer mention of the catapult in Chinese sources may be found in the Mohist texts of the Warring States period (5th – 3rd centuries BC). In these texts, the catapults were operated using the lever principle, and are known as traction catapults. These devices could be used by either the besieger or the besieged. As a weapon employed by the besieged, the traction catapult could be used to attack enemy siege towers, and to hurl objects at enemy troops either to kill them or to disrupt their formation.

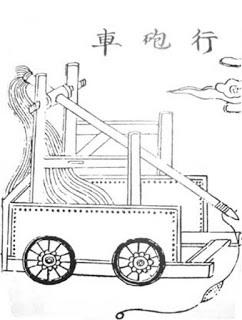

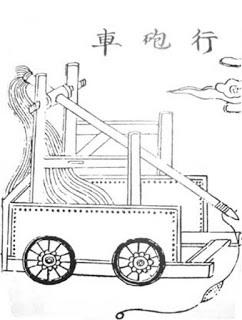

Ancient Chinese mobile catapult cart. ( CC BY 1.0 )

The Torsion Catapults

In the West, by contrast, catapults operated according to a different principle. Instead of using the lever technique, European catapults operated according to torsion mechanics. This technology was first introduced by the Greeks, and later adopted by the Romans.

By the European Middle Ages, a variation of the Roman ‘onager’ was developed. This was called the mangonel, which means ‘an engine of war’ (mangonel may also refer to other siege engines). The primary difference between an ‘onager’ and a mangonel is that the latter launched its projectiles from a fixed bowl rather than from a sling. This meant that instead of a large, single projectile, the mangonel could be used also to launch a few smaller projectiles.

A Medieval mangonel. ( Public Domain )

Traction Meets Torsion

Whilst torsion-operated catapults were being used by European armies, Chinese traction catapult technology had also spread westwards during and around the 6th century AD. It has been speculated that the knowledge of this technology was partially responsible for the victories achieved by the Islamic armies over the next few centuries.

Nevertheless, the first recorded Western encounter with the traction catapult was not during a battle with a Muslim army, but with a nomadic tribe known as the Avars. According to John, an Archbishop of Thessaloniki, during the siege of the city in 597 AD, the Avars were using 50 large traction catapults that hurled stones at the defenders.

It has been speculated that the Avars had interacted with the Northern Wei in China, and learned the traction catapult technology from them. European encounters with the traction catapults of the Muslims (commonly known as ‘al-manjaniq’) would only come later during the Islamic conquest of Iberia. However, it has been argued that it was only during the Crusades that such technology became adopted in Europe.

The Evolution of the Trebuchet

The catapult eventually evolved into the hinged counter-weight trebuchet, a siege engine that had much greater accuracy and range, as well as a higher trajectory than the catapult. Whilst the trebuchet dominated the European battlefield for several centuries, it soon became obsolete in China due to the introduction of gunpowder weapons.

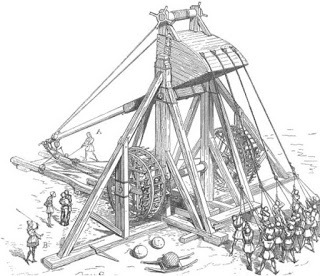

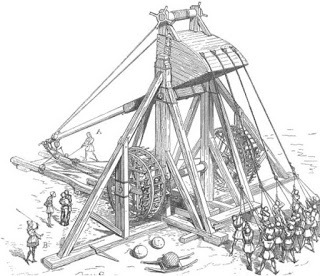

Replica of a trebuchet, Castle Laupen, Switzerland. ( CC BY 3.0 )

The arrival of gunpowder in Europe also signaled the end of the widespread use of these siege engines. However, the last major use of catapults in battle is said to have happened during the First World War, when French troops used these devices to hurl grenades into German trenches.

French soldiers using a grenade catapult in World War I. ( Public Domain )

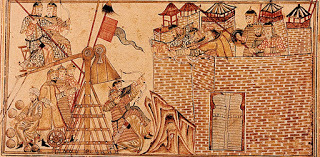

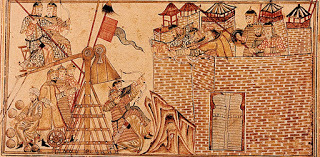

Featured image: 13th Century illustration of Mongols laying siege to a Middle-Eastern city using a trebuchet. ( Public Domain )

By: Ḏḥwty

One of the most iconic images of the European Middle Ages is the castle. This defensive structure was often heavily fortified and provided its inhabitants with much-needed safety. It was usually quite difficult for an enemy to capture a castle, and for that, an attacking army needed siege engines. One of the most important and efficient siege engines was the catapult.

The Roman Onager

The catapult was a weapon used since ancient times. In its most basic form, the catapult may be described as a “one-armed stone thrower”. In the Roman world, a catapult-like siege engine known as the ‘onager’ (meaning ‘wild ass’) was used when the Romans were besieging an enemy. One suggestion for this name’s origins is that the Romans likened the stones that were hurled by the catapult to the rocks kicked up behind galloping hooves. An alternate suggestion is that the device jumped when it fired its projectiles. Another type of catapult, which had a sling, was known as the ‘scorpion’, as a shot from this device is reported to resemble the movement of a scorpion’s tail.

A Roman onager with sling (‘Scorpion’). ( Public Domain )

Chinese Traction Catapults

The use of catapults, however, was not limited to the Roman army. There are records which show that the catapult was also employed by the armies of ancient China as well. For example, during the early Spring and Autumn period (8th – 7th centuries BC), there was a machine called a ‘hui’ that was used by the King of Zhou against the Duke of Zheng during a battle in 707 BC. As the word ‘hui’ no longer exists, we cannot be completely sure of its meaning. Nevertheless, scholars from the Han Dynasty interpreted this device as a catapult.

A clearer mention of the catapult in Chinese sources may be found in the Mohist texts of the Warring States period (5th – 3rd centuries BC). In these texts, the catapults were operated using the lever principle, and are known as traction catapults. These devices could be used by either the besieger or the besieged. As a weapon employed by the besieged, the traction catapult could be used to attack enemy siege towers, and to hurl objects at enemy troops either to kill them or to disrupt their formation.

Ancient Chinese mobile catapult cart. ( CC BY 1.0 )

The Torsion Catapults

In the West, by contrast, catapults operated according to a different principle. Instead of using the lever technique, European catapults operated according to torsion mechanics. This technology was first introduced by the Greeks, and later adopted by the Romans.

By the European Middle Ages, a variation of the Roman ‘onager’ was developed. This was called the mangonel, which means ‘an engine of war’ (mangonel may also refer to other siege engines). The primary difference between an ‘onager’ and a mangonel is that the latter launched its projectiles from a fixed bowl rather than from a sling. This meant that instead of a large, single projectile, the mangonel could be used also to launch a few smaller projectiles.

A Medieval mangonel. ( Public Domain )

Traction Meets Torsion

Whilst torsion-operated catapults were being used by European armies, Chinese traction catapult technology had also spread westwards during and around the 6th century AD. It has been speculated that the knowledge of this technology was partially responsible for the victories achieved by the Islamic armies over the next few centuries.

Nevertheless, the first recorded Western encounter with the traction catapult was not during a battle with a Muslim army, but with a nomadic tribe known as the Avars. According to John, an Archbishop of Thessaloniki, during the siege of the city in 597 AD, the Avars were using 50 large traction catapults that hurled stones at the defenders.

It has been speculated that the Avars had interacted with the Northern Wei in China, and learned the traction catapult technology from them. European encounters with the traction catapults of the Muslims (commonly known as ‘al-manjaniq’) would only come later during the Islamic conquest of Iberia. However, it has been argued that it was only during the Crusades that such technology became adopted in Europe.

The Evolution of the Trebuchet

The catapult eventually evolved into the hinged counter-weight trebuchet, a siege engine that had much greater accuracy and range, as well as a higher trajectory than the catapult. Whilst the trebuchet dominated the European battlefield for several centuries, it soon became obsolete in China due to the introduction of gunpowder weapons.

Replica of a trebuchet, Castle Laupen, Switzerland. ( CC BY 3.0 )

The arrival of gunpowder in Europe also signaled the end of the widespread use of these siege engines. However, the last major use of catapults in battle is said to have happened during the First World War, when French troops used these devices to hurl grenades into German trenches.

French soldiers using a grenade catapult in World War I. ( Public Domain )

Featured image: 13th Century illustration of Mongols laying siege to a Middle-Eastern city using a trebuchet. ( Public Domain )

By: Ḏḥwty

Published on April 14, 2018 23:30

Boys Joust Wanna Have Fun

Medievalists

By Natalie Anderson

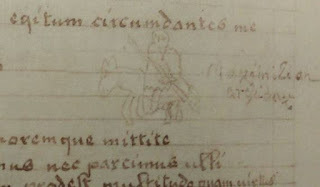

Sketch from the childhood Lehbruch of Maximilian I

Hands down, my favourite image that I came across over the course of my PhD research was the above – at first glance, a rather inconspicuous, unglamourous one. In the margins of his childhood Lehrbuch, or textbook, the future Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519) has doodled a picture of himself as a knight on horseback. Astride his rather wonky steed, Maximilian is holding his lance at the ready, prepared to take part in that quintessential medieval sport: the tournament. Although, with a well-developed sense of social status, Maximilian has appropriately signed the picture ‘Maximilian archidux’ (in his youth he held the title of archduke of Austria), the young noble still displays the same timeless, universal urge of bored schoolchildren everywhere: to escape their current, mundane surroundings by imagining themselves somewhere more exciting.

For Maximilian, even as a grown man, this ideal escape was always the tournament. And it was the same for many noblemen of the fifteenth century. After all, knightly training was an essential part of a young man’s education, and the ability to excel in the tournament and, in particular, in the individual joust, was an integral part of one’s social standing, image, and networking abilities. Thus this training began at a young age, and a love of the tournament was instilled in boys during their childhood (as is so clearly evidenced by the above image).

Kunsthistorisched Museum, Vienna, Inv. No. P81, P92.

Interestingly, toys played a central role in this. A boy might be given miniature figures of jousting men on horseback to play with, such as these from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

The same toys can be seen in one of Maximilian’s biographies (in the loosest sense of the Maximilian (right) playing with jousting figurines in Weisskunig. word) Weisskunig – a highly allegorical retelling of the emperor’s life. As a young man, Maximilian may be seen playing with similar proto-action figures, learning the rules of the joust. Much as they do today, medieval toys taught their owners about their expected societal roles.

Indeed, play was often a central teaching tool. Another great example of this are the ‘training lances’ that boys used when first being introduced to that most masculine activity of jousting. Rather than being tipped with steel lanceheads, these wooden shafts had two whirling flags on the end, making for a harmless imitation of the actual sport. Soon enough, however, these whimsical objects were exchanged for the real thing.

Maximilian (right) playing with jousting figurines in Weisskunig.

Yet some knights still apparently remembered them with fondness. In one sixteenth century Turnierbuch, or tournament book – a popular form of commemorative tournament literature – one man’s equipment features an image of the youthful training tool. The same object may even be seen in three-dimensional form on his crest! One imagines it twirling eye-catchingly in the breeze as he charged toward his opponent.

When the young Maximilian absentmindedly sketched the above image into his textbook, he was imagining his future as the quintessential medieval knight: clad in shining armour, mounted on horseback, lance at the ready. By the fifteenth century, this was a future all boys were encouraged to imagine, through the use of toys and childhood training. Knightly practices were instilled in them from a young age, and practice for the tournament was a central part of this.

A child’s jousting toy, from ‘Hans Burgkmair des Jüngeren: Turnierbuch von 1529’.

Published on April 14, 2018 00:00

April 12, 2018

Mythical Viking Sunstone Used for Navigation was Real and Remarkably Accurate, New Study Shows

Ancient Origins

The Vikings have been reputed to be remarkable seafarers who could fearlessly navigate their way through unknown oceans to invade unsuspecting communities along the North Sea and Atlantic Sea coasts of Europe. A well-known ancient Norse myth describes a magical gem that could reveal the position of the sun when hidden behind clouds or even after sunset. A new study shows the sunstone was real and very accurate.

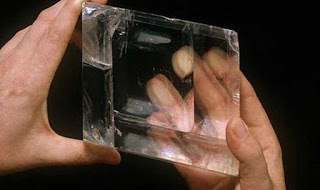

Several accounts in the ancient Nordic sagas speak of a sólarsteinn or “sunstone”, which they used to determine the sun’s position after sunset. For years, it was thought to be little more than a legend. But in 2010, a unique crystal was found in the wreck of an Elizabethan ship sunk off the coast of the Channel Islands. After three years of intensive study, scientists announced that the crystal made of a calcite substance could indeed act as a navigational aid.

According to those researchers, the principle behind the sunstone relies on its unusual property of creating a double refraction of sunlight, even when it is obscured by cloud or fog. By turning the crystal in front of the human eye until the darkness of the two shadows were equal, the sun's position can be pinpointed with remarkable accuracy.

The Vikings were known to be master seafarers. Leiv Eiriksson Discovers America by Christian Krohg, 1893 ( public domain )

New Study Reveals Accuracy

Phys.org reports on a new study conducted by researchers from ELTE Eötvös Loránd University in Hungary, who ran computer simulations of 1000 voyages between Norway and Greenland with varying cloudiness, in order to determine how accurate the sunstone was in navigation.

“After inputting data describing such trips, the researchers ran the simulations multiple times over the course of two specific virtual days, the spring equinox and the summer solstice. They ran the trials for different types of crystals and with differing intervals between sunstone tests,” reported Phys.org.

The results of their study revealed that using a cordierite crystal for a minimum of every three hours was around 92.2 to 100 percent accurate.

“This explains why the Vikings could rule the Atlantic Ocean for 300 years and could reach North America without a magnetic compass,” the study authors wrote in the paper published by the Royal Society Open Science .

Sunstone was Used in Parallel to a Sun Compass

Researchers believe that they combined the power of the sunstone with that of a sun compass or ‘sundial’ to navigate their ships after dark.

Wooden fragment discovered in Uunartoq, Greenland, in 1948, which is believed to be a sun-compass used to determine direction. Image credit: Soren Thirslund.

Part of a Viking sun compass was unearthed in 1948 in a fjord in Uunartoq, Greeland, which was settled by Norse farmers in the 10 th century. Originally believed to be a household decoration, researchers later discovered that the lines engraved along the edge were for navigational purposes.

“The team found that at noon every day, when the sun is highest in the sky, a dial in the center of the compass would have cast a shadow between two lines on the plate,” reported Live Science in 2013. “The ancient seafarers could have measured the length of that noon shadow using scaling lines on the dial, and then determined the latitude.”

A scene from the Vikings (2013) History Channel Series demonstrates how the sundial was used.

Top image: A calcite crystal found on an Elizabethan ship believed to have helped the Vikings navigate the seas. Credit: The Natural History Museum.

By April Holloway

Published on April 12, 2018 23:30

April 11, 2018

Robert the Bruce: champion of Scotland or murderous usurper?

History Extra

On 10 February 1306, the most important political murder in Scottish history took place. John Comyn, “the Red”, was slaughtered by Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick, and his followers in an outburst of violence in the church of the Franciscans, the Greyfriars, at Dumfries.

Comyn and Bruce were leading members of the Scottish nobility. They had been rivals and had recently fought on opposing sides in the wars between Edward I of England and the Scots. In early 1306 with Edward finally recognised as ruler of Scotland, the two lords met together in the Greyfriars church. At first the men seemed friendly and Bruce talked alone with Comyn before the high altar.

Suddenly the mood changed. Bruce accused his rival of treachery. Making to walk away, Robert Bruce then turned back with sword drawn and struck Comyn. Bruce’s followers then rushed in, raining blows on John Comyn who fell to the floor. Comyn’s uncle, who joined the melee, was cut down. Bruce left the church. Mounted on Comyn’s horse he led his followers the short distance to Dumfries Castle where King Edward’s justices were holding court.

Breaking in, Bruce arrested the king’s men but then he heard news that Comyn was still alive. He dispatched two of his men to the friary. They found John Comyn tended by the friars in the vestry, wounded but not dying.

After allowing him to hear confession, Bruce’s men dragged Comyn back into the church and killed him on the altar steps, spattering the altar itself with blood. While Comyn’s corpse was abandoned to the friars, Bruce rode from Dumfries to begin the uprising against Edward I which would climax with his crowning as king of Scots six weeks later.

Those seeking to understand these events saw Comyn’s death as a deliberate step on Bruce’s path to the throne. The English investigation of the murder in 1306 concluded that Comyn was killed because “he would not assent to the treason that Bruce planned against the king of England, it is believed”. In English chronicles of the period, Bruce lured Comyn to Dumfries to kill him. In Scottish accounts, by contrast, Bruce and Comyn agreed to work together for Scotland’s freedom. Comyn, however, betrayed Bruce’s plans to Edward I and was killed in revenge for his treachery.

All these versions agree in identifying Bruce in February 1306 as a man preparing to launch a bid for the kingship and killing Comyn to clear the way. The portrayal of Bruce as either cold-blooded killer or clear-sighted champion of his people suited the conflicting perceptions of later years. It placed the murder at the heart of a planned coup which would also involve Bruce’s seizure of the throne and his war against the English king, a war which ultimately secured recognition of Scotland’s independence.

However, these interpretations also relied on a heavy dose of hindsight. If viewed from the perspective of February 1306 do the conclusions of these accounts seem quite so clear? Was Bruce at that time focused on the seizure of the throne? Was the killing of Comyn on holy ground, an act bound to appal and alienate many Scots, a deed of calculated revolution? Did the immediate aftermath of Comyn’s death, the six weeks before Bruce was crowned king, witness the unfolding of a planned coup? The answers lie in the evidence which emerged before Bruce assumed the reputation and role of hero king or bloody usurper.

The difficult years

In early 1306 Robert Bruce was not an obvious champion of Scottish liberties. He was in his early 30s and his career had been shaped by the decade-long wars between Edward I (ruled England 1272–1307) and the Scots.

The king of England had taken advantage of a succession crisis in Scotland after the death of Alexander III (who ruled Scotland 1249–86). Bruce’s position in this conflict was defined by family interests. Part of this was the Bruce claim to the Scottish throne. This had been rejected in favour of the rival rights of John Balliol in 1292 but with Balliol in exile from 1296 the Bruces did not abandon hope of a crown.

While Bruce was conscious of his family’s royal aspirations, it was his responsibilities as a nobleman which exerted most influence on his activities. As earls of Carrick and lords of Annandale in south-west Scotland and a number of English estates, the Bruces had to preserve lands in two warring kingdoms and protect their friends and tenants in the difficult years since 1296. In these years Bruce had played a shifting role. He had briefly led resistance to Edward I in 1297 and had been a guardian of Scotland between 1298 and 1300 but after both episodes had submitted to the English king.

From 1302 to 1304 he had been active in Edward’s government of Scotland. Bruce’s shifts of side were motivated less by a machiavellian hopes of winning the throne than by the duty to preserve his family’s lands and tenants from the worst effects of war.

His actions were normal amongst the Scottish nobility and were entirely understandable to contemporaries. They do not, though, reveal Bruce as a man committed to the abstract defence of Scotland. Instead they suggest a young lord whose concerns were with more limited and pragmatic issues of lordship and loyalty.

In the months before February 1306 Robert Bruce continued to face these concerns in new circumstances. In 1304 Edward I finally compelled his leading Scottish enemies to submit to his rule. He was now the master of Scotland and during the next year Scotland’s nobles sought his favour and petitioned him for lands and offices. Bruce was one of this group.

In April 1304 his father had died and Bruce approached the king to receive his family’s lordship of Annandale. The succession of enquiries into the Bruces’ ancient rights in their estates probably encouraged Bruce to find allies. To this end, in June 1304 he entered a bond or private alliance with William Lamberton, the bishop of St Andrews.

Deep political rivals

While this was later used by the English to suggest a conspiracy between Bruce and one of the leaders of the Scottish church, its terms do not support this. Instead it was a formal statement of friendship between lords who had recently been on opposite sides in the war but now saw the need to co-operate.

Needing to secure his inheritance and under government scrutiny, Bruce would have found such an alliance valuable, especially as Lamberton became head of Edward’s Scottish council. Issues of land, lordship and influence within this Edwardian Scotland seem to have preoccupied Robert Bruce in 1304–5.

The same issues explain Bruce’s presence in Dumfries on 10 February and his meeting with John Comyn. The king’s justices were holding court in Dumfries and as local landowners it would be natural for Bruce and Comyn to be present. For them to meet in private to discuss the court’s business would also be normal.

However any meeting between these two men came with considerable baggage. There is a garbled tale in several accounts of an indenture between Bruce and Comyn which may indicate a promise of mutual support like that between Bruce and Bishop Lamberton. In the case of Bruce and John however, any written expressions of friendship overlay deep animosity.

The two men were open political rivals. Comyn’s family were long-standing opponents of the Bruces and between 1302 and 1304, while Bruce served King Edward, Comyn had led the king’s enemies. They were also personal enemies. In 1299 Bruce and Comyn were the guardians of Scotland, leading the war against the English. When a dispute broke out between followers of the two men, Comyn turned on Bruce and seized him by the throat.

Accusations of treason were flung at Bruce before the two men were separated. The mistrust and violence between Bruce and Comyn in 1299 may have flared again in February 1306, perhaps sparked by a similarly minor disagreement.

Seeking a deal

The closely contemporary account of Walter of Guisborough hints at this scenario. Bruce and Comyn met to discuss “certain matters touching both of them”. During the conversation Bruce charged Comyn with influencing King Edward against him.

This suggests less the betrayal of a conspiracy than competition for royal favour between rivals which had cost Bruce lands and offices and may have broken a written promise of friendship. Old antagonisms spurred Bruce into an attack on Comyn and others present joined in the fight. The result was not assassination but a bloody scuffle.

The aftermath of the killing suggests that even then Bruce only slowly developed the intention of seizing the throne. It would be six weeks before he was crowned and in this period the consequences of Comyn’s death and the nature of Bruce’s intentions only gradually unfolded.

Vital evidence of this comes from an English report, crucially written in early March before Bruce took the throne. It shows Bruce remaining in the south-west, taking castles and trying to recruit followers in the manner of previous aristocratic rebellions. The report also reveals that Bruce was negotiating with Edward I and his officials and in these talks indicated that he had taken castles “to defend himself with the longest stick that he had”.

This was not the unequivocal defiance of a king in waiting but suggests a man trying to safeguard his position but still seeking a deal, perhaps a pardon for Comyn’s death. However the report shows that such aims were changing.

The writer identifies the key figure in this as Wishart, the bishop of Glasgow. Robert Wishart was a veteran defender of Scottish liberties and in early March, as Bruce’s “chief adviser”, he absolved Bruce from his sins and “freed him to secure his heritage”. This could only mean that Bruce was now determined to bid for the throne. Wishart provided the spiritual support. By releasing Bruce from his oath to Edward and from the sacrilege of slaying Comyn on holy ground the bishop made Bruce a credible leader of the Scots.

It had taken weeks for this move and it was only in March that Bruce started to widen his appeal and win support. On 25 March Bruce was crowned King of Scots at Scone.

The ceremony was makeshift and, if it demonstrated that the new king had gathered support from clergy, nobles and people, a majority stayed away, refusing to recognise the usurper or unwilling to risk sharing in his likely defeat.

Edward I’s terrible retribution

Bruce had taken a huge gamble. He was on a path of no return and by October he and his friends had paid a heavy price. Defeated three times in battle by English and Scottish enemies, Bruce fled the Scottish mainland. Many of his supporters and family suffered worse fates as Edward I wreaked a terrible punishment on those he regarded as perjured rebels.

With stakes so high it would always have been a huge risk to plan a rebellion against Edward. It would not be surprising if Bruce, a wealthy and influential noble with a career of cautious self-interest to his name, baulked at such a gamble. Instead, through lingering personal antagonism which sparked an act of unpremeditated violence, Bruce put his future in jeopardy. By killing Comyn, Bruce had made enemies of John’s family and following. As well as this blood feud Bruce now faced the judgement of Edward I, not a lenient or forgiving ruler.

In these unpromising circumstances and influenced by Bishop Wishart, Bruce took the decision which changed his life and Scotland’s future. He laid claim to the title and authority of king, appealing to his family’s allies and to those Scots who wished to renew the war against the English king. Despite the defeats of 1306 it would be in this role that Bruce would return to Scotland the following year. From 1307 as King of Scots Robert Bruce would begin to win his realm.

Michael Brown is reader in medieval Scottish history at the University of St Andrews. His books include The Wars of Scotland 1214-1371, (Edinburgh University Press, 2004) and Bannockburn: The Scottish War and the British Isles, 1307-1323 (Edinburgh University Press, 2008).

Published on April 11, 2018 23:30

Tyr: The Norse God of Law and War Breaks a Promise

Ancient Origins

The Norse god Tyr is not very well-known, at least when compared to such names as Odin and Thor. But he is also part of the Aesir tribe in the Norse pantheon and Tyr could be called the bravest of the Norse gods. This aspect of his personality is evident in the best-known myth about him, the Binding of Fenrir.

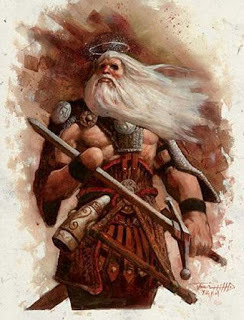

Tyr - God of Justice, War, and Law

Tyr was once a major god widely worshipped by various Germanic peoples and there were several variations to his name. In Old English, for instance, he was known as Tiw, whilst Tyz was his name in Gothic. In the pantheon of these Germanic peoples, Tyr was regarded to be a god of war. Given the war-like culture of these peoples, Tyr would have been one of their most important deities.

The role of Tyr diminished, however, with the arrival of the Viking Age, as he was superseded by Odin and Thor. These two gods were also associated with war, though they were also associated with wisdom, strategy, and cunning. As a result, Tyr was overtaken by Odin and Thor in importance.

The Norse god Týr, here identified with Mars. ( Public Domain )

Tyr became the god of law and justice, the role which he is remembered for today. Whilst war and law seem to be two contradicting aspects of life, to the Norse and other Germanic peoples, these two aspects are actually intertwined. Law, like war, may be used to settle disputes, and victory may be gained over an opponent using either method. Additionally, a legal assembly could be regarded metaphorically as a battlefield.

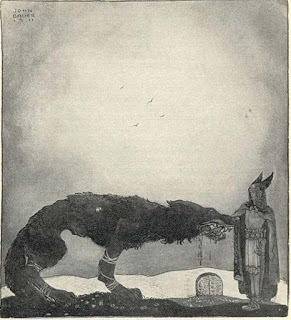

The Binding of Fenrir

Tyr is easily recognized as he is depicted as a god with only one hand. The explanation for this is found in the myth known as the Binding of Fenrir, arguably the most famous tale regarding Tyr. In this myth, the gods wanted to bind the great wolf Fenrir. This monstrous wolf was one of the three offspring of Loki, and the gods had been keeping him in Asgard since he was a puppy in order to keep an eye on him. As Fenrir continued to grow, the gods began to worry that they would not be able to keep him in their home and, fearing that he would wreak havoc if he left Asgard, they planned to have the creature bound up.

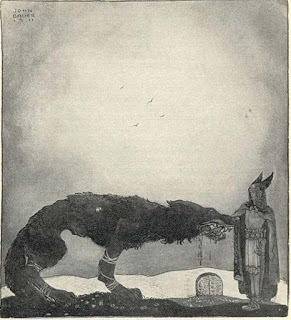

Tyr. ( CC BY SA )

The gods, therefore, began to bind Fenrir with various ropes and chains. In order to obtain Fenrir’s consent to being tied up, the gods told the wolf that these bindings were meant to test his strength. Each time Fenrir broke free, the gods cheered and clapped, though in their hearts, they were growing increasingly worried. Eventually, the gods decided to seek the help of the dwarves, the best blacksmiths available, to produce a rope or chain that not even the great wolf would be able to break free from. As a result, Gleipir was formed. This was a light and silky rope made from several rather odd ingredients – the sound of a cat’s footsteps, the beard of a woman, the roots of a stone, the breath of a fish, and the spittle of a bird.

Tyr and Fenrir. ( Hellanim)

Consequences

When Fenrir saw the rope, he became suspicious, and would only allow the gods to tie him up on the condition that one of them placed his hand in his jaw as a sign of good faith. Despite knowing the consequences of his actions, Tyr volunteered to place his hand in the wolf’s mouth. Tyr had befriended Fenrir when he was still a pup and was known to be an honorable god, and so the wolf trusted him. When Fenrir found that he had been tricked, and that he could not break loose from Gleipnir, he was furious, and bit Tyr’s hand off. Tyr lost not only a hand, but also a friend.

Tyr and Fenrir. ( Public Domain )

Fenrir would be bound until Ragnarok, when he would break free from Gleipnir and devour Odin. As for Tyr, he would face Garm, the guard dog of Hel, and both would succeed in killing each other.

Top Image: Tyr, Gleipnir and Fenrir. Source: Wolnir

By Wu Mingren

The Norse god Tyr is not very well-known, at least when compared to such names as Odin and Thor. But he is also part of the Aesir tribe in the Norse pantheon and Tyr could be called the bravest of the Norse gods. This aspect of his personality is evident in the best-known myth about him, the Binding of Fenrir.

Tyr - God of Justice, War, and Law

Tyr was once a major god widely worshipped by various Germanic peoples and there were several variations to his name. In Old English, for instance, he was known as Tiw, whilst Tyz was his name in Gothic. In the pantheon of these Germanic peoples, Tyr was regarded to be a god of war. Given the war-like culture of these peoples, Tyr would have been one of their most important deities.

The role of Tyr diminished, however, with the arrival of the Viking Age, as he was superseded by Odin and Thor. These two gods were also associated with war, though they were also associated with wisdom, strategy, and cunning. As a result, Tyr was overtaken by Odin and Thor in importance.

The Norse god Týr, here identified with Mars. ( Public Domain )

Tyr became the god of law and justice, the role which he is remembered for today. Whilst war and law seem to be two contradicting aspects of life, to the Norse and other Germanic peoples, these two aspects are actually intertwined. Law, like war, may be used to settle disputes, and victory may be gained over an opponent using either method. Additionally, a legal assembly could be regarded metaphorically as a battlefield.

The Binding of Fenrir

Tyr is easily recognized as he is depicted as a god with only one hand. The explanation for this is found in the myth known as the Binding of Fenrir, arguably the most famous tale regarding Tyr. In this myth, the gods wanted to bind the great wolf Fenrir. This monstrous wolf was one of the three offspring of Loki, and the gods had been keeping him in Asgard since he was a puppy in order to keep an eye on him. As Fenrir continued to grow, the gods began to worry that they would not be able to keep him in their home and, fearing that he would wreak havoc if he left Asgard, they planned to have the creature bound up.

Tyr. ( CC BY SA )

The gods, therefore, began to bind Fenrir with various ropes and chains. In order to obtain Fenrir’s consent to being tied up, the gods told the wolf that these bindings were meant to test his strength. Each time Fenrir broke free, the gods cheered and clapped, though in their hearts, they were growing increasingly worried. Eventually, the gods decided to seek the help of the dwarves, the best blacksmiths available, to produce a rope or chain that not even the great wolf would be able to break free from. As a result, Gleipir was formed. This was a light and silky rope made from several rather odd ingredients – the sound of a cat’s footsteps, the beard of a woman, the roots of a stone, the breath of a fish, and the spittle of a bird.

Tyr and Fenrir. ( Hellanim)

Consequences

When Fenrir saw the rope, he became suspicious, and would only allow the gods to tie him up on the condition that one of them placed his hand in his jaw as a sign of good faith. Despite knowing the consequences of his actions, Tyr volunteered to place his hand in the wolf’s mouth. Tyr had befriended Fenrir when he was still a pup and was known to be an honorable god, and so the wolf trusted him. When Fenrir found that he had been tricked, and that he could not break loose from Gleipnir, he was furious, and bit Tyr’s hand off. Tyr lost not only a hand, but also a friend.

Tyr and Fenrir. ( Public Domain )

Fenrir would be bound until Ragnarok, when he would break free from Gleipnir and devour Odin. As for Tyr, he would face Garm, the guard dog of Hel, and both would succeed in killing each other.

Top Image: Tyr, Gleipnir and Fenrir. Source: Wolnir

By Wu Mingren

Published on April 11, 2018 00:00

April 9, 2018

How was music invented? A medieval answer

Medievalists

Detail of a miniature of a man playing a portable organ, with a harp lying beside him. British Library MS Harley 334 f.25v

The Middle Ages saw a renewed interest in music, with new styles being formed, and the creation of musical notation that we still use today. In monasteries and universities music was being studied and many works survive from the period that examine the mechanics of singing and how to perfect various sounds.

These works often also dealt with the history of music, and one question they tried to answer is how music came to be, and who should be credited with inventing it. Looking for answers, the medieval writers turned to Biblical sources as well as Greek and Roman mythology and legends. They usually put forward several answers, including crediting a character from the Book of Genesis named Jubal, who was said to have played the flute, or Amphion, a son of Zeus, who was given the lyre.

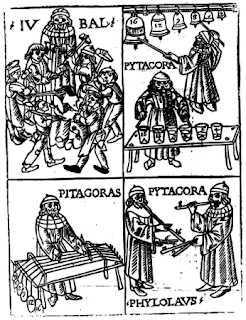

One popular story from the Middle Ages credits the Greek philosopher Pythagoras as the inventor of music. The Introductorium musicae, written in first half of the 15th century by Johannes Keck, explains:

He, they say, by chance passing a forge, heard the blow of four hammers making the diapente (fifth), diatessaron (fourth), and octave in the proportions of their sounds. But suspicious whether by change this proposition of sounds depended on the strength of the arms of the smiths working thus, he himself instructed the smiths that they strike again with hammers exchanged. Then, notwithstanding the changing of the hammers, the former proportion of sounds remained for each of them. Whence he learned in clever fashion from the trial, that in the weight of the hammers consisted of the sounds.

A much different explanation is given in the 13th century manual Summa musice, where the author tries to use the etymology of words to track the origins of music:

Some say that ‘musica’ is equivalent to ‘moysica’ from ‘moys’, which means water, because when rain water (or any other kind) falls upon different kinds of substance – now upon roofs, now upon stones, now upon land, now upon water, now upon empty vessels, now upon the leaves of trees – it produces different sounds, and the Ancients are said to have devised music by bringing these sounds together.

Meanwhile, Florentius de Faxolis, an Italian musician and priest, offered this ancient legend to help explain how stringed instruments were invented:

It is reported by some that on a certain occasion the Nile flooded far more than usual, so that the lands about its banks were covered; after its retreat countless fish perished, left without water all over the fields. And it happened at that time that Mercury made his way through this sand and found a shell in which a fish had already rotted; Mercury is said to have taken the shell and found nothing but four tendons of the fish that had been in it; he is reported to have touched them one by one and thus become the first to discover this tetrachord.

Medieval woodcut showing Pythagoras with bells and other instruments in Pythagorean tuning.

It might be fair to say medieval authors understood that all these competing legends and stories meant that they would never really know the origins of music. Perhaps many of them shared the view expressed in the Summa musice:

With regard to all of this, let us fittingly say, with Aristotle, that the beginnings of all arts, and implements at the time of their invention, were crude and meagre, each successive innovator adding something new. In this manner the trickle of an ultimate source, enlarged by a confluence of waters, can be turned into a river carrying ships, and it could have been, as Moses says, that Jubal was the first, from whose name we derive both ‘iubllus’ and ‘iubalare’, and that the others mentioned, coming afterwards, added something new and so on up to the present time.

Published on April 09, 2018 23:00

Hundreds of Place Names of Old Norse Origin in the British Isles

Many English villages and towns were founded by Vikings. (Photo: John Baker/ videnskab.dk)

In the 9th and 10th centuries Norwegian, Danish and Swedish Vikings crossed the ocean and sailed to the British Isles, and their legacy is still very much alive: Hundreds of place- and personal names of Old Norse origin tell that the Norsemen not only came to plunder, but that many also chose to settle on the isles to the west.

A recently published article in Antiquity, international quarterly journal of archaeological research, suggests that the number of Scandinavians have been larger than previous DNA studies demonstrate: As many as between 20,000 and 35,000 Vikings may have relocated to England.

The Vikings did have a strong influence on the English language, including place- and personal names, which is the linguistic evidence for the high number of settlers, according to the language researchers.

When the Scandinavians arrived in England, they met a local population who spoke Old English.

Old Norse and Old English were closely related with many identical or similar words. Today, many place names in the British Isles are Old Norse names or a combination of the two languages.

Three examples of English village names of Old Norse origin:

Lofthouse – lopt-hús (Old Norse) A house with a loft or upper chamber.

Hulme – holmr (Old Norse) An island, an inland promontory, raised ground in marsh, a river-meadow.

Towton (“Tofi’s farm/settlement”), pers.n. (Old Norse) Personal name, tūn (Old English) An enclosure; a farmstead; a village; an estate.

The large number and variety of names, either wholly or partly Scandinavian, is important evidence supporting the theory that Old Norse was spoken in many parts of England.

In the year 1086 AD, only two decades after the last Viking invasion in 1066, the English “Domesday Book” (a manuscript record of the “Great Survey” of large parts of England and parts of Wales), was completed.

The many Norse place names demonstrate the big influence Scandinavian Vikings had in the British Isles.

In the British Museum’s homepage, you can find out whether the name of a village, town or city on the British Isles origins from the Vikings.

British Museum writes: “This map shows all English, Welsh, Irish and a selection of Scottish placenames with Old Norse origins.

In England, these are more prevalent north of the line marked in black, which represents the border described in a treaty between King Alfred and the Viking leader, Guthrum, made between AD 876 and 890.”

Howth village and outer suburb of Dublin, Ireland: The name Howth is probably from the Old Norse “Hǫfuð” (“head” in English). (Photo: Bjørn Christian Tørrissen / Wikimedia Commons)

“This description – up the Thames, and then up the Lea, and along the Lea unto its source, then in a straight line to Bedford, then up on the Ouse to Watling Street – is traditionally thought to demarcate the southern boundary of the ‘Danelaw’ – the region where ‘Danish’ law was recognised.

In reality it may have been more of a ‘legal fiction’ than a real border, but it does seem to roughly mark the southern limits of significant Scandinavian settlement in Britain.”

Text by: ThorNews

Other sources: Danish science portal videnskab.dk

Published on April 09, 2018 00:00

April 7, 2018

Kleppmelk – A Viking Recipe

Thor News

Traditional dinner: Kleppmelk served with sugar and cinnamon. (Photo: renmat.no)

Kleppmelk (klepp milk) is a soup commonly used in the Trøndelag region and in Northern Norway. It consists of thick pancake batter formed into bowls simmered in milk.

It is reasonable to believe that the dish is very old since the word klepp stems from Old Norse kleppr meaning pile, a naked rock or a large stone.

However, Klepp has many definitions, including a hand tool shaped like a fishhook on a shaft (fishing gaff), a municipality in Rogaland County, and Kleppr is a Norse boy´s name.

Kleppmelk is also known as bollemelk (bun milk) and kleppsuppe (klepp soup).

Ingredients (Serves 4)

2 eggs

10 cups (2.5 l) milk

1.6 – 2.5 cups (4-6 dl) flour, wheat and barley

4 teaspoons sugar

1 teaspoon salt

Method

Dough

Mix eggs and sugar with 2.1 cups (5 deciliters) milk. Blend in the flour until it becomes a firm dough. You can use only wheat flour, but it is recommended to replace 1/4 of the flour with barley.

Soup

Mix salt and the rest of the milk. Bring to boiling point. (Pay close attention when you heat the milk – it may bubble over)

Using a tablespoon, make small bowls out of the dough, and place them in the hot milk. Let them simmer for about 10 minutes.

Serve with sugar and cinnamon and a glass of cold (!) milk.

Text by: Anette Broteng Christiansen, ThorNews

Traditional dinner: Kleppmelk served with sugar and cinnamon. (Photo: renmat.no)

Kleppmelk (klepp milk) is a soup commonly used in the Trøndelag region and in Northern Norway. It consists of thick pancake batter formed into bowls simmered in milk.

It is reasonable to believe that the dish is very old since the word klepp stems from Old Norse kleppr meaning pile, a naked rock or a large stone.

However, Klepp has many definitions, including a hand tool shaped like a fishhook on a shaft (fishing gaff), a municipality in Rogaland County, and Kleppr is a Norse boy´s name.

Kleppmelk is also known as bollemelk (bun milk) and kleppsuppe (klepp soup).

Ingredients (Serves 4)

2 eggs

10 cups (2.5 l) milk

1.6 – 2.5 cups (4-6 dl) flour, wheat and barley

4 teaspoons sugar

1 teaspoon salt

Method

Dough

Mix eggs and sugar with 2.1 cups (5 deciliters) milk. Blend in the flour until it becomes a firm dough. You can use only wheat flour, but it is recommended to replace 1/4 of the flour with barley.

Soup

Mix salt and the rest of the milk. Bring to boiling point. (Pay close attention when you heat the milk – it may bubble over)

Using a tablespoon, make small bowls out of the dough, and place them in the hot milk. Let them simmer for about 10 minutes.

Serve with sugar and cinnamon and a glass of cold (!) milk.

Text by: Anette Broteng Christiansen, ThorNews

Published on April 07, 2018 23:30

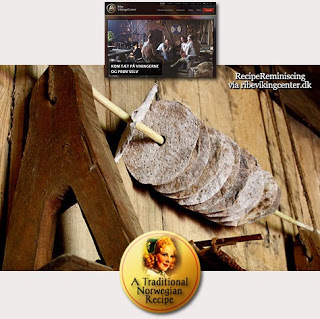

Viking Crisp Bread / Viking Knekkebrød

Thor News

Tasty crackers, crisp bread, flatbread, wheat loaf and rye loaf baked over the fire or in the oven were served with homemade butter, cheese, honey and ham. It smells fantastic and tastes even better.

Here is a Vikings recipe for crisp bread which are easily altered if you prefer baking your bread in a modern oven. Still, why not try bread making over a fire in the garden or on the grill on the terrace.

0.5 jug lukewarm water

6 cups rye flour

6 cups wheat flour

1 tablespoon salt

1 tablespoon ground cumin

3 cups rye flour for rolling out the dough

1 jug = approximately 2 pt. / 1 litre

1 cup = approximately 0,3 pt. / 1,5 dl

Mix all the ingredients and knead well. Divide the dough in 20 pieces and form into balls. Roll out each ball in plenty of rye flour until thin and round. Cut out a hole in the middle of each crisp bread and prick them with a fork. Or if you prefer, cut the dough into strips instead of rounds.

The fireplace must be warmed up well ahead. Before placing the crisp breads on the bottom of the fireplace, sweep it to remove ashes. Turn the crisp breads when slightly browned.

Put a stick through the hole and store the crisp breads hanging from the roof as seen on the picture or store the crisp bread in a closed bread box of birch bark or wood.

Published on April 07, 2018 00:00