MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 18

July 31, 2018

The Briton and the Dane: Timeline - character interview

Interview with Dr. Gwyneth Franger

Commentator (C): Thank you for agreeing to this interview, Dr. Franger.

Gwyneth (G): Please call me Gwyneth, and I appreciate this opportunity for my fans to know the “real me”.

C: Let’s start with where do you live?

G: London, but the year is 2066. It is an exciting city, rich in history, but also progressive, blending the old with the new. One challenge, however, is the recruitment of talented men and women to study the past, not only in the classroom but on archeological sites. There is nothing more exciting than discovering ancient artifacts buried in rubble after spending hours, days or even years, removing centuries of dirt and debris.

C: You appear passionate about history. Did you always feel that way?

G: Since I was old enough to hold a shovel. I would spend hours in the park, “excavating” possible sites. It didn’t bother me that I never discovered a relic, I was learning my craft. One day I struck an object; you can imagine my excitement when I unearthed pieces of Roman pottery. Of course, I didn’t learn until much later that my parents were behind my first find.

C: What is your favorite archeological site?

G: Excavating the ruins of the Wareham citadel. Thankfully, the fortress had been reinforced with stone, since the wooden structures suffered the effects of not only time but of natural disasters, such as fire. The Keep, which is the tower, still stands as it once did during the reign of Alfred the Great. The view is breathtaking, and I never tire of summer evenings watching the waves crashing gently upon the rocks below.

C: Has your belief in God helped or hindered your investigations?

G: I definitely believe in Divine Intervention. There is no other way to explain how I was transported, unscathed, back in time to the eleventh century. My life definitely changed from the experience, and without this Divine Intervention, I would not have returned to my timeline, and we wouldn’t be having this conversation.

C: What was it like living in the eleventh century?

G: It was quite a challenge, and I was very concerned about doing something that would change the course of history. I had seen the old Star Trek shows and was very aware of the dangers of interfering. I found having to take a submissive female role disconcerting, but I threw myself into the role of my character. What helped was having studied drama one summer at Stratford-upon-Avon with the Royal Shakespeare Company.

C: Who provided for you during that time?

G: Lord Erik of Wareham, my husband. Again, this is where Divine Intervention comes into play. The night I arrived in Wareham, Erik was waiting for me in the chapel; yes, we were married that evening. He had been expecting me, which I found unnerving. However, he didn’t know at that point that I was from the future. I need to interject that I have had an obsession with him since I stumbled upon a rare painting at a Renaissance Fair. The portrait is still on the wall in my office.

C: Fascinating. When did you take Erik into your confidence? And were other people privy to your true identity?

G: It was disturbing, initially. However, Erik’s belief and trust in God was strong; everything he could not understand was attributed to Divine Intervention. Remember, religion played an important role in everyday life. While Erik accepted I was from the future, he never pressed me for information about how events turned out. There were a select few who were taken into our confidence, but as far as everyone else was concerned, I was Lord Erik’s wife who was not from these parts.

C: Would you change anything if you were able to revisit the eleventh century?

G: The thought is tempting; how different would the world be if William the Conqueror had been defeated at the Battle of Hastings? Oh, my gosh, we could discuss what ifs for hours on end and still be unhappy with the results. I am grateful for having the opportunity to live during a time that people can only read about in history books, and I count my blessings every day that I have been so blessed.

C: Thank you, Gwyneth, for your candor. We look forward to reading about your adventures in The Briton and the Dane: Timeline.

Purchase: Amazon US Amazon UK Barnes and Noble iTunes Smashwords

Learn more about Mary Ann Bernal and Whispering Legends Press

Published on July 31, 2018 23:00

July 1, 2018

SMASHWORDS SUMMER/WINTER SALE RUNS JULY 1 THOUGH JULY 31 2018

Author Mary Ann Bernal is participating in the Smashwords Summer/Winter Sale (July 1 - July 31). All her novels and short story collections are available at either a reduced price or are free. Why not stop by her profile page and have a look? Click here to find all of Mary Ann Bernal's works.

Published on July 01, 2018 11:57

June 28, 2018

Myths, Legends, Books & Coffee Pots: Author Inspiration ~ Mary Ann Bernal

Myths, Legends, Books & Coffee Pots: Author Inspiration ~ Mary Ann Bernal #amwriting #H...:

Author Inspiration

I have always been fascinated by how people perceive events or actions differently. Where I see a wounded soldier running a marathon with a prosthetic leg as a hero, someone else might see only a disabled person participating in a race meant for physically fit individuals.

Throughout history, perception has played a key role when assessing motivation but was the assessment correct, and if so, did the character in question agree with the end result or did the character believe something else? As the saying goes, one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.

One of my favorite strong women of the middle ages is Eleanor of Aquitaine. Hollywood’s portrayal as seen in The Lion in Winter, which is an entertaining period piece and not historically accurate, showcases an intelligent woman adept at palace intrigue, who wishes to see her son, Richard, on the throne after Henry’s demise. It would seem the end-game for Eleanor’s scheming is to obtain her freedom, knowing Richard would have her released from confinement. But we must not forget Henry’s request for an annulment so he might marry his mistress. Eleanor comes across as manipulative and cunning and well-versed in deception. But is that how Eleanor sees herself?

Another Hollywood favorite is Camelot where the fair Guinevere betrays Arthur for Lancelot. Initially, whilst singing The Simple Joys of Maidenhood, she doesn’t think twice about causing a war, which comes to fruition at the end of the movie. Was there any thought given as to what warfare actually means? Was life worthless in her mind? But Guinevere recognizes she must remove temptation from Arthur’s court by having Lancelot sent away, reflected in the song If Ever I Would Leave You. Guinevere appears to be conflicted, but does she perceive herself as a victim because of an arranged marriage?

And then there is Troy. Helen is miserable in an alleged loveless marriage and runs off with Paris but Menelaus convinces his brother, Agamemnon, to help him get her back. Does history perceive Helen differently than she perceived herself? Possibly, more likely, probably. After all, Helen was the reason Troy fell. Did she regret her decision that led to the deaths of Hector, Achilles, and Paris? Was she reunited with Menelaus? Or did she relish the carnage?

Perception, as love, is in the eye of the beholder.

These epic blockbusters were paramount in my decision to write a novel wherein perception plays a major role when condemning or acclaiming the lead character.

It was an easy decision to choose an existing persona from The Briton and the Dane trilogy. Concordia was a child when the trilogy ends. Fast forward a few years and we have a nineteen-year-old young lady of privilege competing in a world where women and children were considered chattel.

Concordia is willful, used to getting her own way, and might be considered spoiled. Educated alongside her brother at the king’s court school, Concordia’s intelligence surpasses many of the men she comes in contact with. She absorbs knowledge like a sponge, is quick-witted, charming and very feminine, playing the game as befits societal expectations.

Outwardly, Concordia may have been adept at deception and intrigue, but at what cost? Was she a hardened conspirator whose sole purpose was to survive in a violent world or was she longing for a love that seemed to elude her grasp? Just as Scarlett O’Hara pined for Ashley Wilkes while married to Rhett Butler, Concordia appears to have made the same mistake.

Some of my readers saw beneath the facade, while others thought Concordia was a pampered, selfish brat. You be the judge.

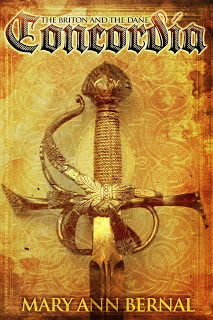

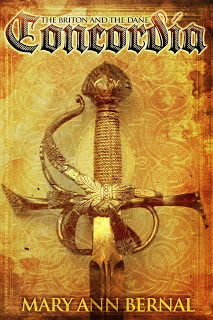

The Briton and the Dane: Concordia

Travel back in time to late Ninth Century Anglo-Saxon Britain where Alfred the Great rules with a benevolent hand while the Danish King rules peacefully within the boundaries of the Danelaw. Trade flourishes, and scholars from throughout the civilized world flock to Britannia’s shores to study at the King’s Court School at Winchester.

Enter Concordia, a beautiful noblewoman whose family is favored by the king. Vain, willful, and admired, but ambitious and cunning, Concordia is not willing to accept her fate. She is betrothed to the valiant warrior, Brantson, but sees herself as far too young to lay in the bedchamber of an older suitor. She wants to see the wonders of the world, embracing everything in it; preferably, but dangerously, at the side of Thayer, the exotic Saracen who charms King Alfred’s court and ignites her yearning passions.

Concordia manipulates her besotted husband into taking her to Rome, but her ship is captured by bloodthirsty pirates, and the seafarers protecting her are ruthlessly slain to a man. As she awaits her fate in the Moorish captain’s bed, by sheer chance, she discovers that salvation is at hand in the gilded court of a Saracen nobleman.

While awaiting rescue, Concordia finds herself at the center of intrigue, plots, blackmail, betrayal and the vain desires of two egotistical brothers, each willing to die for her favor. Using only feminine cunning, Concordia must defend her honor while plotting her escape as she awaits deliverance, somewhere inside steamy, unconquered Muslim Hispania.

Purchase Links

Amazon USAmazon UKSmashwordsBarnes and NobleiTunes

Author Inspiration

I have always been fascinated by how people perceive events or actions differently. Where I see a wounded soldier running a marathon with a prosthetic leg as a hero, someone else might see only a disabled person participating in a race meant for physically fit individuals.

Throughout history, perception has played a key role when assessing motivation but was the assessment correct, and if so, did the character in question agree with the end result or did the character believe something else? As the saying goes, one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.

One of my favorite strong women of the middle ages is Eleanor of Aquitaine. Hollywood’s portrayal as seen in The Lion in Winter, which is an entertaining period piece and not historically accurate, showcases an intelligent woman adept at palace intrigue, who wishes to see her son, Richard, on the throne after Henry’s demise. It would seem the end-game for Eleanor’s scheming is to obtain her freedom, knowing Richard would have her released from confinement. But we must not forget Henry’s request for an annulment so he might marry his mistress. Eleanor comes across as manipulative and cunning and well-versed in deception. But is that how Eleanor sees herself?

Another Hollywood favorite is Camelot where the fair Guinevere betrays Arthur for Lancelot. Initially, whilst singing The Simple Joys of Maidenhood, she doesn’t think twice about causing a war, which comes to fruition at the end of the movie. Was there any thought given as to what warfare actually means? Was life worthless in her mind? But Guinevere recognizes she must remove temptation from Arthur’s court by having Lancelot sent away, reflected in the song If Ever I Would Leave You. Guinevere appears to be conflicted, but does she perceive herself as a victim because of an arranged marriage?

And then there is Troy. Helen is miserable in an alleged loveless marriage and runs off with Paris but Menelaus convinces his brother, Agamemnon, to help him get her back. Does history perceive Helen differently than she perceived herself? Possibly, more likely, probably. After all, Helen was the reason Troy fell. Did she regret her decision that led to the deaths of Hector, Achilles, and Paris? Was she reunited with Menelaus? Or did she relish the carnage?

Perception, as love, is in the eye of the beholder.

These epic blockbusters were paramount in my decision to write a novel wherein perception plays a major role when condemning or acclaiming the lead character.

It was an easy decision to choose an existing persona from The Briton and the Dane trilogy. Concordia was a child when the trilogy ends. Fast forward a few years and we have a nineteen-year-old young lady of privilege competing in a world where women and children were considered chattel.

Concordia is willful, used to getting her own way, and might be considered spoiled. Educated alongside her brother at the king’s court school, Concordia’s intelligence surpasses many of the men she comes in contact with. She absorbs knowledge like a sponge, is quick-witted, charming and very feminine, playing the game as befits societal expectations.

Outwardly, Concordia may have been adept at deception and intrigue, but at what cost? Was she a hardened conspirator whose sole purpose was to survive in a violent world or was she longing for a love that seemed to elude her grasp? Just as Scarlett O’Hara pined for Ashley Wilkes while married to Rhett Butler, Concordia appears to have made the same mistake.

Some of my readers saw beneath the facade, while others thought Concordia was a pampered, selfish brat. You be the judge.

The Briton and the Dane: Concordia

Travel back in time to late Ninth Century Anglo-Saxon Britain where Alfred the Great rules with a benevolent hand while the Danish King rules peacefully within the boundaries of the Danelaw. Trade flourishes, and scholars from throughout the civilized world flock to Britannia’s shores to study at the King’s Court School at Winchester.

Enter Concordia, a beautiful noblewoman whose family is favored by the king. Vain, willful, and admired, but ambitious and cunning, Concordia is not willing to accept her fate. She is betrothed to the valiant warrior, Brantson, but sees herself as far too young to lay in the bedchamber of an older suitor. She wants to see the wonders of the world, embracing everything in it; preferably, but dangerously, at the side of Thayer, the exotic Saracen who charms King Alfred’s court and ignites her yearning passions.

Concordia manipulates her besotted husband into taking her to Rome, but her ship is captured by bloodthirsty pirates, and the seafarers protecting her are ruthlessly slain to a man. As she awaits her fate in the Moorish captain’s bed, by sheer chance, she discovers that salvation is at hand in the gilded court of a Saracen nobleman.

While awaiting rescue, Concordia finds herself at the center of intrigue, plots, blackmail, betrayal and the vain desires of two egotistical brothers, each willing to die for her favor. Using only feminine cunning, Concordia must defend her honor while plotting her escape as she awaits deliverance, somewhere inside steamy, unconquered Muslim Hispania.

Purchase Links

Amazon USAmazon UKSmashwordsBarnes and NobleiTunes

Published on June 28, 2018 06:25

June 11, 2018

Discovering reader preferences, habits and attitudes – Announcing the 2018 Reader Survey

by M.K. Tod, Heather Burch, and Patricia Sands

Readers and writers – a symbiotic relationship. Ideas spark writers to create stories and build worlds and characters for readers’ consumption. Readers add imagination and thought to interpret those stories, deriving meaning and enjoyment in the process. A story is incomplete without both reader and writer.

What then do readers want? What constitutes a compelling story? How do men and women differ in their preferences? Where do readers find recommendations? How do readers share their book experiences?

ANNOUNCING A 2018 READER SURVEY designed to solicit input on these topics and others.

Please click here to take the survey and share the link https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/68HL6F2 with friends and family via email or your favorite social media. Robust participation across age groups, genders, and countries will make this year’s survey – the 4th – even more significant.

Those who take the survey will be able to sign up to receive a summary report when it becomes available.

M.K. (Mary) Tod writes historical fiction. Her latest novel, Time and Regret was published by Lake Union. Fellow authors Patricia Sands and Heather Burch helped design and plan the survey. Mary can be contacted on Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads or on her blog A Writer of History .

Published on June 11, 2018 23:30

The Dead Tell Us of a Diverse Londinium

Ancient Origins

Rebecca Redfern /The Conversation

Our knowledge about the people who lived in Roman Britain has undergone a sea change over the past decade. New research has rubbished our perception of it as a region inhabited solely by white Europeans. Roman Britain was actually a highly multicultural society which included newcomers and locals with black African ancestry and dual heritage, as well as people from the Middle East.

For the most part, these findings have been welcomed by the public, and incorporated by museums into displays and educational content. But, post-Brexit referendum and in an atmosphere of growing nationalism, they have also been rejected and ridiculed .

The research behind this dramatic change in our understanding comes from my field of bioarchaeology, a sub-field of archaeology which focuses on the study of human remains using a variety of techniques drawn from osteology and forensics. Bioarchaeology’s aim is to understand the lives of past people in context, combining data about their skeleton with information about the society in which they lived.

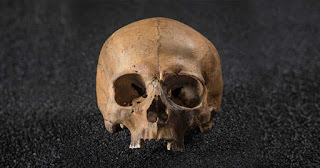

Who exactly are the Roman dead? © Museum of London

We can investigate further than ever before by looking at people’s diet and childhood origin using light stable isotopes : naturally occurring chemicals in drinking water and food sources, which are used by the body to make bones and teeth. We also use new techniques in analyzing ancient DNA to understand aspects of their physical appearance, diseases and population affiliation. The new perspective on Roman Britain that this research has uncovered is explored in the Museum of London’s latest exhibition , which I helped curate.

People vs objects

History is always subject to bias – what kind of bias and the scale of it just depends on the sources of evidence. There’s a dominance of male authored primary sources in the Roman period, for example, which distorts our perspective. One important source of information about the movement of people in the Roman period are inscriptions, particularly from tombstones. These show that people had come to Britain from the Mediterranean, France and Germany. But this heavily skews our understanding towards men, people with a military connection, and elites.

But skeletons provide a unique perspective on the society and environment in which a person lived. These factors shaped their health, and bones and teeth retain this evidence, revealing information such as where they spent their early childhood. These are datasets which are therefore independent of many sources of bias. Bioarchaeological studies of Roman-period skeletons have really challenged knowledge based upon traditional sources of archaeological evidence.

Take evidence from material culture, such as jewelry. In the past, when items with a continental origin were found in a burial, all too often a direct connection was made between the origin of these items and the person laid to rest. Take the unique burial of a 14-year-old girl in Southwark (London), whose grave goods included glassware and a carved ivory clasp knife in the shape of a leopard, rare items with connections to the wider empire.

Examples of Roman grave goods. © Museum of London

The original site report of the excavation suggested that the girl had come from Carthage, because of the leopard imagery and use of ivory. But intriguingly, later forensic ancestry, stable isotope and aDNA analyses revealed that she grew up in the southern Mediterranean and then spent at least the last four years of her life in London. She had white European ancestry, blue eyes and the genetic group to which her maternal DNA belonged was HV6, which is found today in southern and eastern Europe.

This case – and there are many others like it – demonstrates the importance of applying new scientific techniques to help solve these important archaeological questions. It also challenges a traditional overreliance on material culture to explore migration.

Discerning information from most burials is not very straightforward, reflecting the adage that “the dead don’t bury themselves” – families and social groups also make choices about the deceased’s funeral. Similar cases have been found elsewhere in Roman Britain, particularly at settlements with military garrisons.

Model of the first bridge over the Thames (85-90AD) at the Museum of London. Image: Steven G Johnson /CC BY SA 3.0

Roman London

In London, these questions become more difficult to answer. Informally established by traders and merchants around 48AD, five years after the Claudian invasion, Londinium soon became the heart of the Imperial administration for the territory.

Unlike many others in Britain, the majority of excavated burials in London either have locally or British-made objects or else none are present (wood and fabric rarely survive to discovery). And the few tombstones we have only survived because they were used to build the Medieval city wall.

In this situation, where many hundreds of people remain anonymous in death, bioarchaeology is the only way to understand the nuances of this unique population. Many of these anonymous people included women and children who had travelled as free people or as slaves, from Italy and Germany, as well as the southern Mediterranean. Only bioarchaeological methods allow us to unpack the true diversity of London’s population at this time. These methods have enabled us to show that people with black African ancestry travelled to and were born in London throughout the Roman period.

The skull of a woman buried in Southwark with curator Meriel Jeater. © Museum of London

We have discovered, for example, that one middle-aged woman from the southern Mediterranean has black African ancestry. She was buried in Southwark with pottery from Kent and a fourth century local coin – her burial expresses British connections, reflecting how people’s communities and lives can be remade by migration. The people burying her may have decided to reflect her life in the city by choosing local objects, but we can’t dismiss the possibility that she may have come to London as a slave.

The evidence for Roman Britain having a diverse population only continues to grow. Bioarchaeology offers a unique and independent perspective, one based upon the people themselves. It allows us to understand more about their life stories than ever before, but requires us to be increasingly nuanced in our understanding, recognizing and respecting these people’s complexities.

Roman Dead Exhibition is showing at the Museum of London Docklands from May 25 to October 28 2018.

Top image: Skull from Roman Dead exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands © Museum of London

This article was originally published under the title ‘ The Roman dead: new techniques are revealing just how diverse Roman Britain was ’ by Rebecca Redfern on The Conversation , and has been republished under a Creative Commons License.

Published on June 11, 2018 00:00

June 9, 2018

Bones found in Magnificent Amphipolis Tomb belong to Five People, Ministry Announced

Ancient Origins

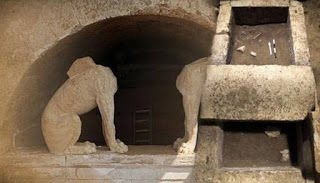

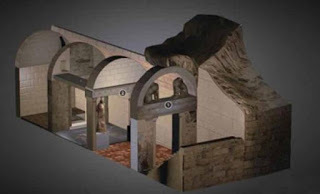

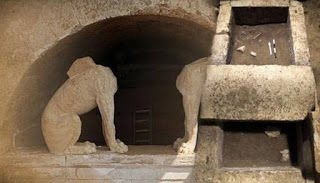

In 2015, the Greek Ministry of Culture announced the long-awaited results of the analysis on the bones found inside the 4th century BC tomb uncovered in Amphipolis in northern Greece. The news was quite unexpected – the bones belonged to not one, but five individuals, pointing to the likelihood that it is a family tomb. However, their has been a setback in their analysis since then. What’s next for the Amphipolis tomb and the remains that were found within?

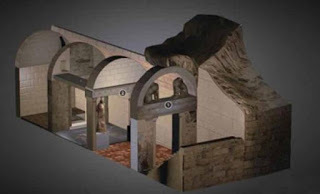

The tomb is located within Kasta Hill in what was once the ancient city of Amphipolis, conquered by Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great, in 357 BC. Experts have known about the existence of the burial mound in Amphipolis, located about 100 km (62.14 miles) northeast of Thessaloniki, since the 1960s, but work only began in earnest there in 2012, when archaeologists discovered that Kasta Hill had been surrounded by a nearly 500-meter (1640.42 ft.) wall made from marble. It was only in 2015 that they discovered the incredible chambers decorated with marble sphinxes and caryatids, an intricate mosaic floor, and a limestone sarcophagus containing hundreds of bone fragments.

Amphipolis Tomb by Greektoys.org (update) on Sketchfab.

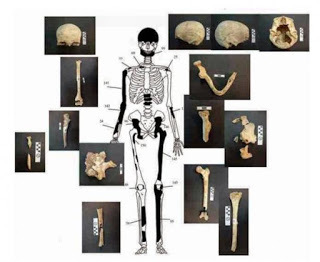

According to the Ministry’s Press Release , archaeologists recovered a total of 550 bone fragments, both crushed and intact, including a skull in good condition. After a meticulous process of piecing the fragments together, scientists identified 157 complete bones.

Following the macroscopic study of bone material, which was undertaken by a multidisciplinary team from the Universities of Aristotle and Democritus, researchers were able to determine that the minimum number of individuals is five – a woman aged around 60 years, two men aged 35-45 years, a newborn infant, and the cremated remains of another individual of unknown age and gender. In addition, they found a number of animal bones, most likely belonging to a horse.

Person 1: Female, approximately 60 years Scientists were able to identify person 1 as female based on the pelvic bones, the bones of the skull, the mandible, and the morphological features of the bones. Age was determined based on the loss of posterior teeth, degenerative lesions, particularly in the spine, and the presence of metabolic diseases such as osteoporosis and frontal hyperostosis. Her height is estimated at 157 cm (5.15 ft.)

Most of the bones found can be attributed to the female, and they were located approximately 1 meter (3.28 ft.) above the floor of the cist.

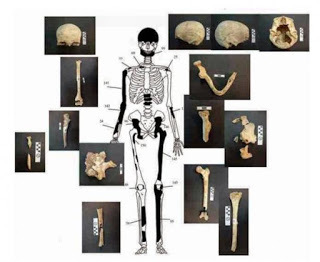

Bones belonging to the 60-year-old female in the Amphipolis tomb. Credit: Ministry of Culture

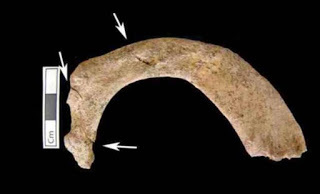

Persons 2 and 3: Two men, 35 to 45 years Two of the individuals identified are known to have been men, one around 35 years of age, and the other closer to 45 years of age. The younger of the two men, whose height is estimated at 168 cm (5.51 ft.), bears traces of cut marks on the left upper thoracic spine, two sides and cervical vertebra. His injuries are consistent with violent injury caused by a sharp instrument, such as a knife, which apparently caused his death (no healing indications could be distinguished.)

The slightly older man, whose bones were found higher than the first man, measures around 162 cm (5.31 ft.) in height and has evidence of a fully healed fracture in his right radius, close to the right wrist. Both men show degenerative osteoarthritis and spondylitis.

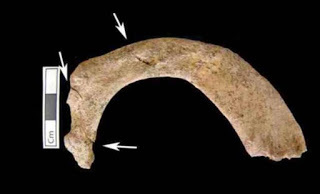

Cut marks were found in multiple places in the bones of person 2 in the Amphipolis tomb. Credit: Ministry of Culture

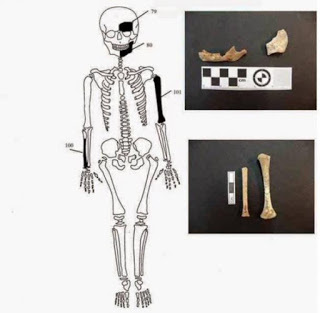

Person 4: Newborn infant The fourth individual identified was a newborn infant, whose sex could not be determined. The determination of age was made based on the length and width of the left humerus and left mandible.

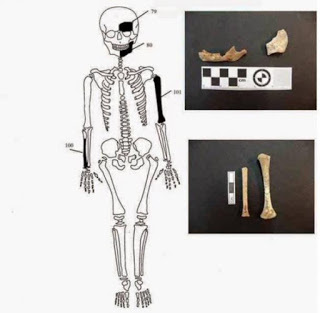

Bones found in the Amphipolis tomb belonging to newborn infant. Credit: Ministry of Culture

Person 5: Cremated individual of unknown age and sex The fifth person is represented by only a few burnt fragments. While age and sex cannot be determined, the bones are believed to belong to an adult individual.

Person 5 bones (Amphipolis tomb) that have undergone the influence of high temperature, after burning. Credit: Ministry of Culture

The scientific team planned to continue to carry out in-depth studies of the bones, including DNA analysis, to obtain more detailed information about the individuals including their diet, their affinity and place of origin, whether they grew up in Amphipolis or had moved from elsewhere, when they were buried/cremated, and whether the individuals are related to each other. The hope was that the results would enable the researchers to piece together the social and historical context and finally determine the identity of the individuals buried inside this incredibly important funerary monument.

However, an update on the research project shows that three and a half years after the fascinating discovery in 2015, the work has come to a standstill. A lack of funding for the project has raised some eyebrows on the current government’s views on the archaeological site. Currently the human remains are being stored in the Amphipolis Museum. They’ve been there ever since the initial macroscopic analysis was completed.

Despite the obstacle in discovering more about the people who were buried inside, there is movement at the Amphipolis tomb. In fact, heavy restoration work has been underway to have the site ready to open to the public in 2020 .

Top Image: Marble sphinx and limestone sarcophagus found at Amphipolis. Source: Greek Ministry of Culture

By April Holloway

In 2015, the Greek Ministry of Culture announced the long-awaited results of the analysis on the bones found inside the 4th century BC tomb uncovered in Amphipolis in northern Greece. The news was quite unexpected – the bones belonged to not one, but five individuals, pointing to the likelihood that it is a family tomb. However, their has been a setback in their analysis since then. What’s next for the Amphipolis tomb and the remains that were found within?

The tomb is located within Kasta Hill in what was once the ancient city of Amphipolis, conquered by Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great, in 357 BC. Experts have known about the existence of the burial mound in Amphipolis, located about 100 km (62.14 miles) northeast of Thessaloniki, since the 1960s, but work only began in earnest there in 2012, when archaeologists discovered that Kasta Hill had been surrounded by a nearly 500-meter (1640.42 ft.) wall made from marble. It was only in 2015 that they discovered the incredible chambers decorated with marble sphinxes and caryatids, an intricate mosaic floor, and a limestone sarcophagus containing hundreds of bone fragments.

Amphipolis Tomb by Greektoys.org (update) on Sketchfab.

According to the Ministry’s Press Release , archaeologists recovered a total of 550 bone fragments, both crushed and intact, including a skull in good condition. After a meticulous process of piecing the fragments together, scientists identified 157 complete bones.

Following the macroscopic study of bone material, which was undertaken by a multidisciplinary team from the Universities of Aristotle and Democritus, researchers were able to determine that the minimum number of individuals is five – a woman aged around 60 years, two men aged 35-45 years, a newborn infant, and the cremated remains of another individual of unknown age and gender. In addition, they found a number of animal bones, most likely belonging to a horse.

Person 1: Female, approximately 60 years Scientists were able to identify person 1 as female based on the pelvic bones, the bones of the skull, the mandible, and the morphological features of the bones. Age was determined based on the loss of posterior teeth, degenerative lesions, particularly in the spine, and the presence of metabolic diseases such as osteoporosis and frontal hyperostosis. Her height is estimated at 157 cm (5.15 ft.)

Most of the bones found can be attributed to the female, and they were located approximately 1 meter (3.28 ft.) above the floor of the cist.

Bones belonging to the 60-year-old female in the Amphipolis tomb. Credit: Ministry of Culture

Persons 2 and 3: Two men, 35 to 45 years Two of the individuals identified are known to have been men, one around 35 years of age, and the other closer to 45 years of age. The younger of the two men, whose height is estimated at 168 cm (5.51 ft.), bears traces of cut marks on the left upper thoracic spine, two sides and cervical vertebra. His injuries are consistent with violent injury caused by a sharp instrument, such as a knife, which apparently caused his death (no healing indications could be distinguished.)

The slightly older man, whose bones were found higher than the first man, measures around 162 cm (5.31 ft.) in height and has evidence of a fully healed fracture in his right radius, close to the right wrist. Both men show degenerative osteoarthritis and spondylitis.

Cut marks were found in multiple places in the bones of person 2 in the Amphipolis tomb. Credit: Ministry of Culture

Person 4: Newborn infant The fourth individual identified was a newborn infant, whose sex could not be determined. The determination of age was made based on the length and width of the left humerus and left mandible.

Bones found in the Amphipolis tomb belonging to newborn infant. Credit: Ministry of Culture

Person 5: Cremated individual of unknown age and sex The fifth person is represented by only a few burnt fragments. While age and sex cannot be determined, the bones are believed to belong to an adult individual.

Person 5 bones (Amphipolis tomb) that have undergone the influence of high temperature, after burning. Credit: Ministry of Culture

The scientific team planned to continue to carry out in-depth studies of the bones, including DNA analysis, to obtain more detailed information about the individuals including their diet, their affinity and place of origin, whether they grew up in Amphipolis or had moved from elsewhere, when they were buried/cremated, and whether the individuals are related to each other. The hope was that the results would enable the researchers to piece together the social and historical context and finally determine the identity of the individuals buried inside this incredibly important funerary monument.

However, an update on the research project shows that three and a half years after the fascinating discovery in 2015, the work has come to a standstill. A lack of funding for the project has raised some eyebrows on the current government’s views on the archaeological site. Currently the human remains are being stored in the Amphipolis Museum. They’ve been there ever since the initial macroscopic analysis was completed.

Despite the obstacle in discovering more about the people who were buried inside, there is movement at the Amphipolis tomb. In fact, heavy restoration work has been underway to have the site ready to open to the public in 2020 .

Top Image: Marble sphinx and limestone sarcophagus found at Amphipolis. Source: Greek Ministry of Culture

By April Holloway

Published on June 09, 2018 23:30

June 8, 2018

The Gladiators of Rome: Blood Sport in the Ancient Empire

Ancient Origins

The ancient Romans were well known for many things – their engineering marvels, their road networks, and the establishment of Roman law throughout the empire. They were, however, also renowned for their war-like nature. After all, this allowed the Romans to build an empire in the first place. This appetite for violence not only manifested itself in Rome’s imperialist policy, but also in its most well-known sport – the gladiatorial combats.

Two Venatores (those who made a career out of fighting in arena animal hunts) fighting a tiger. Floor mosaic in Great Palace of Constantinople (Istanbul), 5th century. (Public Domain)

It has been suggested that the concept of gladiatorial games has its roots in the Etruscans, the predecessors of the Romans. In Etruscan society, gladiatorial games were supposed to be part of the funerary rituals honoring the dead. Thus, gladiatorial combats originally possessed a sacred significance. Over the centuries, however, these funerary games came to be a form of entertainment, and the earliest Roman gladiatorial combat is said to have taken place in 264 BC

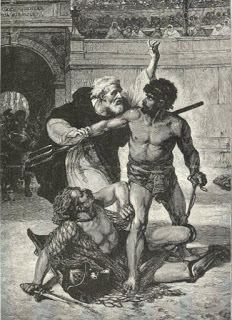

'The Garden Arbor', 1878, depicting a brutal gladiator battle ( Public Domain )

The gladiators were often prisoners of war, slaves, or criminals with a death sentence . The use of Rome’s defeated enemies in these games is reflected in some of the gladiator types, including the Thraex (or Thracian), the Hoplomachus and the Samnite. Thus, gladiatorial combats may be seen as a way for the Romans to re-enact the wars that they had with their conquered subjects. Yet, not all gladiators were forced into the trade.

Despite the hard and precarious life, gladiators were the superstars of their day. The benefits to be found in fighting in the arena – fame, glory and fortune, were strong enough to entice some people to become gladiators voluntarily. (However, the evidence of such citizen gladiators is extremely slim .) It is also recorded that some Roman emperors even participated in gladiatorial games themselves, the most famous of whom was probably the emperor Commodus. The participation of emperors in these games, however, was scorned by some, as gladiators belonged to the lowest of social classes.

Studies analyzing the teeth of supposed gladiators which have been found in Driffield Terrace, York, UK have also suggested that gladiators generally came from harsh backgrounds. The research shows most of the men were extremely malnourished as children and likely came from disadvantaged homes. Their remains show the poor men were well fed and adapted to battle later in life – possibly so they would be stronger and more impressive looking combatants in the gladiatorial games.

Despite the low social status of gladiators, they had the potential to gain the patronage of the upper classes, even that of the emperor himself. According to Suetonius, the emperor Nero awarded a gladiator, Spiculus, with houses and estates worthy of generals returning triumphantly from a war. Regardless of the authenticity of his claim, Suetonius intended to highlight the extravagant nature of the emperor by demonstrating that Nero was willing to shower a presumably lower classed individual with such expensive gifts.

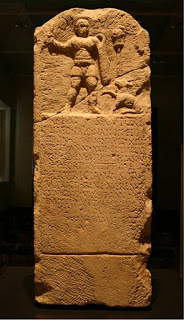

Carving showing a Roman Emperor presiding over gladiatorial games. ( Sailko/CC BY SA 3.0 )

Whilst the story of Spiculus may be an extreme case, assuming that it was true, gladiators were indeed valuable assets to their “owners”. The more victories a gladiator won the more valuable he was. The popularity of victorious gladiators is evident in the surviving graffiti on walls in Rome and other cities where such games were held. Some of the graffiti reveal the number of victories a gladiator had: Petronius Octavius 35, Severus 55, Nascia 60, whilst others suggest that gladiators were quite popular with the women: ‘Crescens, the net fighter, holds the hearts of all the girls’, and ‘Caladus, the Thraecian, makes all the girls sigh’.

Stele for the gladiator Urbicus, from Florence, killed after 13 fights aged 22, in the mid-3rd century. In the inscription the man is mourned by his wife of 7 years, Lauricia, and by his two daughters, Olympia and Fortunensis. The inscriptions warns obscurely "the one who kills the winner", adding that Urbicus' fans (amatores) would keep his memory alive. ( No Copyright Restrictions )

By the 4th century AD, the popularity of gladiatorial games was in a decline, as the Roman Empire adopted Christianity as its official religion. It was, however, only in 404 AD that gladiatorial games were altogether banned by the emperor Honorius due to the martyrdom of St. Telemachus. According to the historian Theodoret, Telemachus was a monk who came to Rome from Asia Minor. During one of the gladiatorial games in the city, Telemachus leapt into the arena to stop two gladiators from fighting. The spectators, who were obviously unhappy with Telemachus’ action, proceeded to stone the monk to death. However, one form of gladiatorial games, the venationes (wild animal hunts), continued for another century.

Telemachus stops two gladiators from fighting. ( Candle in a Cave )

Top Image: Dramatic painting portraying gladiators in the arena. Jean-Léon Gérôme's 1872. Source: Public Domain

By Ḏḥwty

Published on June 08, 2018 23:00

June 7, 2018

When did medical practitioners start to be called ‘doctor’?

History Extra

Anyone with a doctorate can be called ‘doctor’. The doctor’s degree was a product of the medieval universities; this higher degree simply conferred the right to teach.

It could be in law, theology, philosophy or medicine (and other disciplines now). The medical hierarchy of practitioners was physician, surgeon and apothecary, and each had defined functions. Physicians, who had gone to university, were the real ‘doctors’, and surgeons and apothecaries, who trained by apprenticeships, were ‘mister’.

But the verb ‘to doctor’ is also very old, and has meanings outside medicine too: to change something, whether in a human body or an inanimate object. This ‘doctoring’ verb made it easy to call medical practitioners ‘doctors’. The rise of the surgeon-apothecary from the mid-18th century consolidated this shift in address. This new group, the ancestor of the modern GP, took care of the whole family: diagnosing, delivering babies, compounding and dispensing drugs, and other surgical tasks.

Edward Jenner, pioneer of vaccination against smallpox and a medical practitioner, would have been called ‘Dr’ Jenner, whereas his teacher, the famous John Hunter (1728–93), would, as a pure surgeon, have been addressed as ‘Mr’ Hunter. Neither Jenner nor Hunter had doctorates, unlike university-trained physicians at the time.

Answered by: William Byrnum, professor emeritus, University College London

Published on June 07, 2018 23:00

June 6, 2018

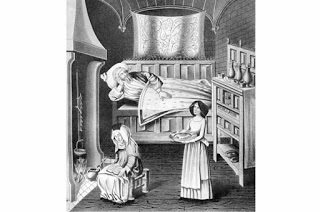

What was the sweating sickness in Tudor England?

History Extra

A rather mysterious illness, the sweating sickness hit in a series of epidemics, but was not always fatal.

Symptoms included cold shivers, headaches, pain in the arms, legs, shoulders and neck, and fatigue or exhaustion. Far from being a disease that raged through the lower classes, many well known individuals of the Tudor court contracted the illness, including Anne Boleyn and her brother and father, George and Thomas, along with Cardinal Wolsey.

The sweating sickness killed numerous nobles and courtiers, including two of the Duke of Suffolk’s sons, Henry and Charles, and Mary Boleyn’s first husband, William Carey.

Lauren Mackay is the author of Inside the Tudor Court: Henry VIII and his Six Wives through the Life and Writings of the Spanish Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys (Amberley Publishing).

Published on June 06, 2018 23:00

June 5, 2018

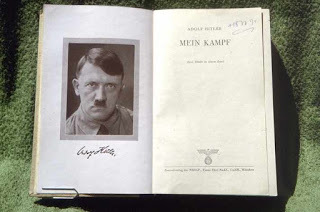

Mein Kampf: what happened to Hitler’s money after his death?

History Extra

It is true that Mein Kampf made Hitler a very rich man. Originally written as a political tract, but also as a way of defraying the costs of Hitler’s treason trial in 1924, the book was translated into 16 languages and had sold around eight million copies by the time of its author’s death in 1945. In the interim, it was estimated to have earned around $1 million per year in royalties, which funded Hitler’s purchase and expansion of his Alpine retreat, the Berghof near Berchtesgaden.

Yet, for all his apparent wealth, Hitler was a rather ascetic character, who had little ‘feel’ for money, and – once chancellor and führer – had little need of it. Indeed, he even chose to forgo his Reich chancellor’s salary and, as his valet recalled, never carried any money on his person.

Thus, the royalties from Mein Kampf were administered by Hitler’s business manager, Max Amann, a director of his publisher, the Franz Eher Verlag in Munich – one of the richest and most influential publishing houses in Nazi Germany.

Prior to his death in April 1945, Hitler wrote a will in which he left most of his possessions and estate to the Nazi Party. However, with the abolition of the latter after the war, along with the Franz Eher Verlag, Hitler’s remaining assets and estate were transferred to Bavaria, the state of which he was a registered resident.

Bavaria has prevented publication of the book in German-speaking territories, and has sought, with limited success, to restrict it elsewhere. Under German law, however, that copyright expired on the 70th anniversary of the author’s death – 30 April 2015.

Heavy demand for the first edition of Hitler’s Mein Kampf to be printed in Germany since his death took its publisher by surprise in January 2016, with orders received for almost four times the print run, the Guardian reported. The BBC has reported in January 2017 that the Institute of Contemporary History (IfZ) in Munich will launch a sixth print run.

Answered by Roger Moorhouse, author of The Devils’ Alliance (Basic Books, 2014) and Berlin at War (Bodley Head, 2010)

Published on June 05, 2018 23:30