MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 118

February 19, 2016

History Trivia - Battle of Lugdunum

February 19

197 Roman Emperor Septimius Severus defeated usurper Clodius Albinus in the Battle of Lugdunum, the bloodiest battle between Roman armies.

197 Roman Emperor Septimius Severus defeated usurper Clodius Albinus in the Battle of Lugdunum, the bloodiest battle between Roman armies.

Published on February 19, 2016 02:00

February 18, 2016

Badger Uncovers Cremation and Grave Goods of Bronze Age Archer Near Stonehenge

Ancient Origins

A curious badger has inadvertently helped archaeologists to unearth remains of an archer or person who made archery equipment sometime between 2,200-2,000 BC in a burial mound at Netheravon, Wiltshire. Some of the artifacts found in the grave include a bronze saw, an archer's wrist guard, and a copper chisel. These goods were located along with cremated human remains.

A curious badger has inadvertently helped archaeologists to unearth remains of an archer or person who made archery equipment sometime between 2,200-2,000 BC in a burial mound at Netheravon, Wiltshire. Some of the artifacts found in the grave include a bronze saw, an archer's wrist guard, and a copper chisel. These goods were located along with cremated human remains.

Netheravon, Wiltshire is five miles (8.05 km) north of the famous archaeological site Stonehenge. Atlas Obscura reports that the artifacts were noticed by Tom Theed after a badger dug up the cremation urn and left sherds of pottery lying on the ground near the burial mound.

Selection of ceramic sherds. (

WSHC

)Mr. Richard Osgood, from the Ministry of Defence (MOD)'s Defence Infrastructure Organisation, told the BBC that it was “an exciting find. It was utterly unexpected. These are wonderful artefacts from the early Bronze Age, about 2,200-2,000 BC.”

Selection of ceramic sherds. (

WSHC

)Mr. Richard Osgood, from the Ministry of Defence (MOD)'s Defence Infrastructure Organisation, told the BBC that it was “an exciting find. It was utterly unexpected. These are wonderful artefacts from the early Bronze Age, about 2,200-2,000 BC.”

Solved: the mystery of Britain’s Bronze Age mummiesAmesbury dig may unravel Stonehenge mysteriesThe Missing Link to Stonehenge: Stone Age Eco-Home Discovered near Famous MonumentBronze Age Britons Mummified the Dead: Smoked over Fires, Preserved in BogsWhile it was a welcome find, Mr. Osgood also noted that burrowing animals are sometimes archaeological risks. Luckily this badger did not create too much damage; however, and it was safely transported to a new home for its role in discovering the burial mound. As he told the Huffington Post, "We would never have known these objects were in there, so there's a small part of me that is quite pleased the badger did this... but it probably would have been better that these things had stayed within the monument where they'd resided for 4,000 years."

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

Copper chisel with bone handle. ( WSHC )The badger did show that his archaeological skills are lacking however, and the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre (WSHC) said in a blog post:

Sherd showing badger claw marks. (

WSHC

)Despite the badger destruction, the WSHC likened the style and importance of the artifacts to those found with the nearby Amesbury Archer.

Sherd showing badger claw marks. (

WSHC

)Despite the badger destruction, the WSHC likened the style and importance of the artifacts to those found with the nearby Amesbury Archer.

Mr. Osgood also noted the quality of the artifacts and the importance they would have had in life 4,000 years ago. He told the Daily Mail:

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

Wrist guard and shaft straighteners. ( WSHC )Featured Image: A European badger. ( CC BY 2.0 ) Wrist guard and shaft straighteners found at the Netheravon burial. ( WSHC )

By Alicia McDermott

A curious badger has inadvertently helped archaeologists to unearth remains of an archer or person who made archery equipment sometime between 2,200-2,000 BC in a burial mound at Netheravon, Wiltshire. Some of the artifacts found in the grave include a bronze saw, an archer's wrist guard, and a copper chisel. These goods were located along with cremated human remains.

A curious badger has inadvertently helped archaeologists to unearth remains of an archer or person who made archery equipment sometime between 2,200-2,000 BC in a burial mound at Netheravon, Wiltshire. Some of the artifacts found in the grave include a bronze saw, an archer's wrist guard, and a copper chisel. These goods were located along with cremated human remains.Netheravon, Wiltshire is five miles (8.05 km) north of the famous archaeological site Stonehenge. Atlas Obscura reports that the artifacts were noticed by Tom Theed after a badger dug up the cremation urn and left sherds of pottery lying on the ground near the burial mound.

Selection of ceramic sherds. (

WSHC

)Mr. Richard Osgood, from the Ministry of Defence (MOD)'s Defence Infrastructure Organisation, told the BBC that it was “an exciting find. It was utterly unexpected. These are wonderful artefacts from the early Bronze Age, about 2,200-2,000 BC.”

Selection of ceramic sherds. (

WSHC

)Mr. Richard Osgood, from the Ministry of Defence (MOD)'s Defence Infrastructure Organisation, told the BBC that it was “an exciting find. It was utterly unexpected. These are wonderful artefacts from the early Bronze Age, about 2,200-2,000 BC.”Solved: the mystery of Britain’s Bronze Age mummiesAmesbury dig may unravel Stonehenge mysteriesThe Missing Link to Stonehenge: Stone Age Eco-Home Discovered near Famous MonumentBronze Age Britons Mummified the Dead: Smoked over Fires, Preserved in BogsWhile it was a welcome find, Mr. Osgood also noted that burrowing animals are sometimes archaeological risks. Luckily this badger did not create too much damage; however, and it was safely transported to a new home for its role in discovering the burial mound. As he told the Huffington Post, "We would never have known these objects were in there, so there's a small part of me that is quite pleased the badger did this... but it probably would have been better that these things had stayed within the monument where they'd resided for 4,000 years."

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]Copper chisel with bone handle. ( WSHC )The badger did show that his archaeological skills are lacking however, and the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre (WSHC) said in a blog post:

“Luckily the badger has not caused too much damage to the objects and evidence of badger activity is only visible in the surface of some fragments of the ceramic sherds. It is probable that the ceramic vessel had remained intact in the ground and unfortunately the badger dug its tunnel through the middle of it, causing the vessel to break into over 200 sherds.”

Sherd showing badger claw marks. (

WSHC

)Despite the badger destruction, the WSHC likened the style and importance of the artifacts to those found with the nearby Amesbury Archer.

Sherd showing badger claw marks. (

WSHC

)Despite the badger destruction, the WSHC likened the style and importance of the artifacts to those found with the nearby Amesbury Archer.Mr. Osgood also noted the quality of the artifacts and the importance they would have had in life 4,000 years ago. He told the Daily Mail:

“The artefacts tell us that those who put the individuals cremated remains into the urn believed them to have been of some significance. These are fine items and there are a lot of them. The flint knife is exquisite. Although highly speculative, it is just so tempting to view these as possibly the grave goods as someone connected with manufacturing archery equipment. At this point in the Early Bronze Age, some 4000 plus years ago, the trappings of archery were important within the burial assemblage although this more frequently includes arrowheads. To get all these items together is very unusual indeed. Another antalizing element is that, in life, the person whose cremated remains we found would have probably known what many of the secrets of nearby Stonehenge were.”Western Daily Press reports that the unexpected discovery has led to a full archaeological dig which uncovered shaft straighteners for straightening arrows and pieces of pottery. The excavation included the aid of injured military personnel and veterans. These and the artifacts dug up by the badger will go on display at Wiltshire Museum in Devizes later this year.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]Wrist guard and shaft straighteners. ( WSHC )Featured Image: A European badger. ( CC BY 2.0 ) Wrist guard and shaft straighteners found at the Netheravon burial. ( WSHC )

By Alicia McDermott

Published on February 18, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Sixth Crusade - ten year truce signed

February 18

1229 The Sixth Crusade: Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor signed a ten-year truce with al-Kamil, regaining Jerusalem, Nazareth, and Bethlehem with neither military engagements nor support from the papacy.

1229 The Sixth Crusade: Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor signed a ten-year truce with al-Kamil, regaining Jerusalem, Nazareth, and Bethlehem with neither military engagements nor support from the papacy.

Published on February 18, 2016 02:00

February 17, 2016

Silver Mines Within an Ancient Town Shed New Light on the Rich History of Greece

Ancient Origins

Thorikos, an ancient town in Attica, was the site of a network of 5 kilometers (3 miles) of silver mines right underneath the town’s acropolis. Researchers believe slaves did the hard work of chipping into the bedrock and extracting the precious lead-silver ore, which in later years contributed to ancient Athens’ wealth.

Thorikos, an ancient town in Attica, was the site of a network of 5 kilometers (3 miles) of silver mines right underneath the town’s acropolis. Researchers believe slaves did the hard work of chipping into the bedrock and extracting the precious lead-silver ore, which in later years contributed to ancient Athens’ wealth.

Evidence of pottery and stone hammers made of volcanic-sedimentary rock show the site was first mined about 3200 BC.

Before the find of the silver mines in Thorikos, researchers had thought the town profited from mines in the Laurion region but did not have its own mines.

The excavations and analysis of the mines, part of more comprehensive archaeological research at Thorikos, is led by Denis Morin. Professor Roald Docter of Ghent University heads the larger project under the auspices of the University of Utrect, the Belgian School at Athens, and the Ephorate of Eastern Attica.

Morin told Heritage Daily:

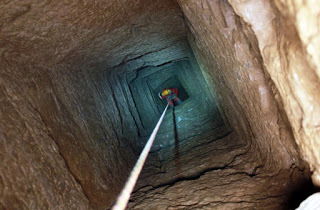

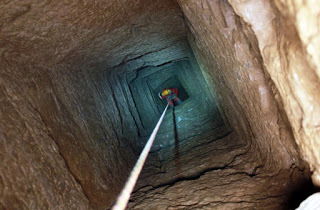

French mining archaeologists have to crawl through cramped tunnels to excavate the site. Some ceilings are no higher than 30 centimeters (12 inches). (

Ghent University

)Modern archaeologists do the difficult and precarious work of exploring the mine shafts using alpine caving techniques. They’ve found that some of the galleries have not been visited for 5,000 years. Others are now walled off and banked up by later mining activities.

French mining archaeologists have to crawl through cramped tunnels to excavate the site. Some ceilings are no higher than 30 centimeters (12 inches). (

Ghent University

)Modern archaeologists do the difficult and precarious work of exploring the mine shafts using alpine caving techniques. They’ve found that some of the galleries have not been visited for 5,000 years. Others are now walled off and banked up by later mining activities.

They are the largest underground mining network yet found in this region of the Aegean. The area was the site of many silver mines going back before Grecian Antiquity.

“Already exploited since the 4th/3rd millennium BC, by the 5th and 4th centuries BC these silver mines constituted the most important mining district of Greece, laying at the basis of Athens’ domination of the Aegean world,” says the article in HeritageDaily.

Bronze Age Mining in Europe Dates Back Earlier than Previously ThoughtThe fight to save the ancient gold mine of SakdrissiAfter the Peloponnesian War of 434-401 BC, the region was largely empty of people, according to the site of The Thorikos Fieldwork Project. In the 300s BC, the Laurion region shifted from commercial and residential activity to the production of silver. “At that time Athens held a firm grip on the metallurgical exploitation of the Laurion as the corpus of 294 mining leases on the Athenian Agora shows (dated 367/66-307/6 BC),” the project site states.

Thorikos is one of the oldest cities of Attica, one of 12 settlements that the ancient Greek hero Theseus unified, according to legend. The site was inhabited continuously from about 4500 BC to the 1st century BC, says the website Greek Travel Pages.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

Remnants of the silver-processing facilities in Thorikos remain. In this facility, workers separated lead from silver. (Alun Salt/CC BY SA 2.0)Over the years, archaeologists have excavated parts of the prehistoric settlement plus the historic era’s homes, cemeteries, a theater, and industrial section. The mines eventually became exhausted, and Roman general Sulla destroyed Thorikos in 86 BC, after which it was abandoned again. Then people re-inhabited it during the Roman era until the 6th century AD, when Slavs overran Attcia, and it was abandoned yet again.

Featured image: Slaves delved and worked the mines right underneath the acropolis of Thorikos. The mines were just discovered by archaeologists and are rewriting the history of the silver-mining Laurion region. Source: Ghent University

By Mark Miller

Thorikos, an ancient town in Attica, was the site of a network of 5 kilometers (3 miles) of silver mines right underneath the town’s acropolis. Researchers believe slaves did the hard work of chipping into the bedrock and extracting the precious lead-silver ore, which in later years contributed to ancient Athens’ wealth.

Thorikos, an ancient town in Attica, was the site of a network of 5 kilometers (3 miles) of silver mines right underneath the town’s acropolis. Researchers believe slaves did the hard work of chipping into the bedrock and extracting the precious lead-silver ore, which in later years contributed to ancient Athens’ wealth.Evidence of pottery and stone hammers made of volcanic-sedimentary rock show the site was first mined about 3200 BC.

Before the find of the silver mines in Thorikos, researchers had thought the town profited from mines in the Laurion region but did not have its own mines.

The excavations and analysis of the mines, part of more comprehensive archaeological research at Thorikos, is led by Denis Morin. Professor Roald Docter of Ghent University heads the larger project under the auspices of the University of Utrect, the Belgian School at Athens, and the Ephorate of Eastern Attica.

Morin told Heritage Daily:

‘Today, it is difficult to imagine the extreme conditions in which the miners had to work in this maze of galleries. A smothering heat reigns in this mineral environment. The progress of the underground survey requires a constant vigilance in this stuffy space where the rate of oxygen must be permanently watched. Tool marks on the walls, graffiti, oil lamps, and crushing areas give evidence of the omnipresent activity of these underground workers. The hardness of the bedrock and the mineralizations show the extreme working conditions of these workers, for the greater part slaves, sentenced to the darkness and the extraction of the lead-silver ore […] Mapping these cramped, complex and braided underground networks, the ramifications of which are sometimes located at several levels, represent a real challenge in scientific terms.’The Legendary Cretan Labyrinth Cave: Inspiration for the Story of King Minos and the Labyrinth of the Minotaur?Did ancient gold mining methods create REAL Golden Fleece and inspire legend of Jason and the Argonauts?The mines are at the foot of the Thorikos Acropolis, which overlooks the harbor of Lavrio, and consist of a network of chambers, shafts and galleries. Many of the subterranean network’s ceilings are no higher than 30 centimeters (12 inches).

French mining archaeologists have to crawl through cramped tunnels to excavate the site. Some ceilings are no higher than 30 centimeters (12 inches). (

Ghent University

)Modern archaeologists do the difficult and precarious work of exploring the mine shafts using alpine caving techniques. They’ve found that some of the galleries have not been visited for 5,000 years. Others are now walled off and banked up by later mining activities.

French mining archaeologists have to crawl through cramped tunnels to excavate the site. Some ceilings are no higher than 30 centimeters (12 inches). (

Ghent University

)Modern archaeologists do the difficult and precarious work of exploring the mine shafts using alpine caving techniques. They’ve found that some of the galleries have not been visited for 5,000 years. Others are now walled off and banked up by later mining activities.They are the largest underground mining network yet found in this region of the Aegean. The area was the site of many silver mines going back before Grecian Antiquity.

“Already exploited since the 4th/3rd millennium BC, by the 5th and 4th centuries BC these silver mines constituted the most important mining district of Greece, laying at the basis of Athens’ domination of the Aegean world,” says the article in HeritageDaily.

Bronze Age Mining in Europe Dates Back Earlier than Previously ThoughtThe fight to save the ancient gold mine of SakdrissiAfter the Peloponnesian War of 434-401 BC, the region was largely empty of people, according to the site of The Thorikos Fieldwork Project. In the 300s BC, the Laurion region shifted from commercial and residential activity to the production of silver. “At that time Athens held a firm grip on the metallurgical exploitation of the Laurion as the corpus of 294 mining leases on the Athenian Agora shows (dated 367/66-307/6 BC),” the project site states.

Thorikos is one of the oldest cities of Attica, one of 12 settlements that the ancient Greek hero Theseus unified, according to legend. The site was inhabited continuously from about 4500 BC to the 1st century BC, says the website Greek Travel Pages.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]Remnants of the silver-processing facilities in Thorikos remain. In this facility, workers separated lead from silver. (Alun Salt/CC BY SA 2.0)Over the years, archaeologists have excavated parts of the prehistoric settlement plus the historic era’s homes, cemeteries, a theater, and industrial section. The mines eventually became exhausted, and Roman general Sulla destroyed Thorikos in 86 BC, after which it was abandoned again. Then people re-inhabited it during the Roman era until the 6th century AD, when Slavs overran Attcia, and it was abandoned yet again.

Featured image: Slaves delved and worked the mines right underneath the acropolis of Thorikos. The mines were just discovered by archaeologists and are rewriting the history of the silver-mining Laurion region. Source: Ghent University

By Mark Miller

Published on February 17, 2016 03:30

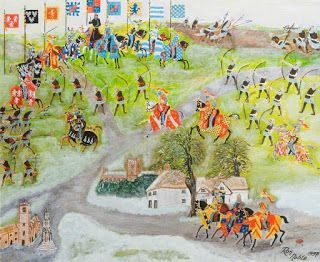

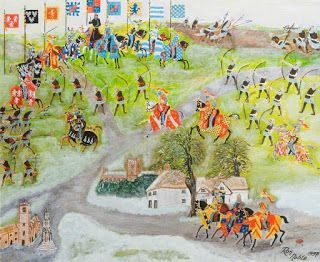

History Trivia - Second Battle of Saint Albans

February 17

1461 Second Battle of Saint Albans where the Lancastrians were victorious, and were able to free King Henry VI who had been imprisoned by the Earl of Warwick.

1461 Second Battle of Saint Albans where the Lancastrians were victorious, and were able to free King Henry VI who had been imprisoned by the Earl of Warwick.

Published on February 17, 2016 01:00

February 16, 2016

The 7 most romantic moments in history

History Extra

Wallis and Edward, 1939. (Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Wallis and Edward, 1939. (Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Marie Curie dedicates her life to the work she began with her husband Perhaps science’s greatest power couple, Pierre Curie and Marie Sklodowskamet in 1894 at the Physics department of the Sorbonne University. Both idealists determined to dedicate their lives to science, they quickly discovered an intellectual like-mindedness. Pierre and Marie were married only a year later and together they embarked on groundbreaking work investigating radioactivity. In 1898 they announced their discovery of two new elements, radium and polonium, and went on to win a joint Nobel Prize for Physics in 1903. The Curie’s married life was dominated by their scientific study and laboratory work, which was often physically as well as mentally exhausting. Their constant exposure to radiation also saw them suffer significant health problems, from fatigue to skin scarring. Outside work, Marie and Pierre enjoyed long, adventurous cycling trips and had two daughters, Irene and Eve. The relationship was brought to a shocking and tragic end in 1906 when Pierre was killed unexpectedly, falling under a heavy horse-drawn cart after slipping in the street. After a period of intense mourning, Marie dedicated her life to pursuing the work they had begun together. She took over Pierre’s position at the Sorbonne, becoming the first woman ever to teach there, and went on to win a second Nobel Prize, for chemistry, in 1911. Through the First World War Marie continued to develop the work she had begun with her husband, as head of the International Red Cross radiology service. She worked tirelessly training medical orderlies and even driving ambulances with X-ray equipment to the front lines. After Marie’s death from aplastic anaemia [deficiency of blood cells caused by failure of bone marrow development] in 1934, brought on by the years of exposure to radioactive substances, she was buried alongside Pierre. Their remains were later moved to Paris’s Pantheon, in recognition of the groundbreaking discoveries they made together. Pierre and Marie Curie in their laboratory, 1898. (Photo12/UIG via Getty Images) Queen Victoria mourns Prince AlbertOne of history’s most popular royal partnerships, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert reigned together for 21 years. Married in 1840, the couple had nine children together and shared the daily duties of royal life. However, the family’s domestic and political stability was shattered on 14 December 1861 when Albert died unexpectedly. A generally healthy man of 42, the prince’s sudden death from typhoid caught both the queen and the nation off-guard. Historian Helen Rappaport suggests that Albert’s death was “nothing less than a national calamity”. Over the years Albert had assumed many of the functions of a reigning monarch, sharing Victoria’s mountain of royal duties and masterminding popular projects such the 1851 Great Exhibition and South Kensington museums complex. Victoria quickly descended into what Rappaport calls a “crippling state of unrelenting grief”. She had not only been reliant on Albert’s help dealing with royal and business affairs, but was intensely dependent on him emotionally. According to Rappaport, “Albert had been all in all to Victoria: husband, friend, confidant, wise counsel, unofficial secretary and government minister. There was not a single aspect of her life on which she had not deferred to his advice and greater wisdom”. She suggests that “Albert had been her one great, abiding obsession in life. Without him Victoria felt rudderless”. This intense grieving quickly created serious problems. Victoria began to take up rigorous and ritualistic observances of bereavement, which lasted far longer than the two-year mourning period conventional at the time. Her reluctance to appear in public and decision to wear black for the rest of her life earned her the nickname the ‘Widow of Windsor’. Helen Rappaport suggests that through these actions, Victoria was “turning her grieving into performance art, retreating into a state of pathological grief which nobody could penetrate and few understood”. Over time, the queen’s sombre retreat from public life significantly impacted on her popularity, with growing complaints that she did nothing to justify her income. Victoria never fully recovered from Albert’s death. She commissioned several monuments in his honour, including the Royal Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens, which was completed in 1876. She remained in mourning for 40 years, until her own death aged 81.

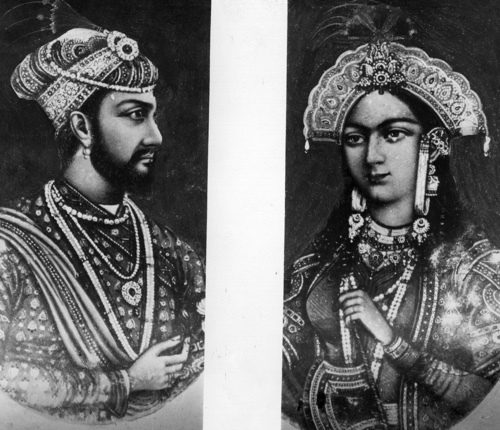

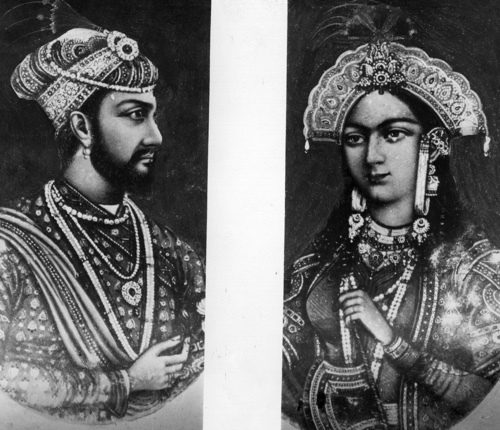

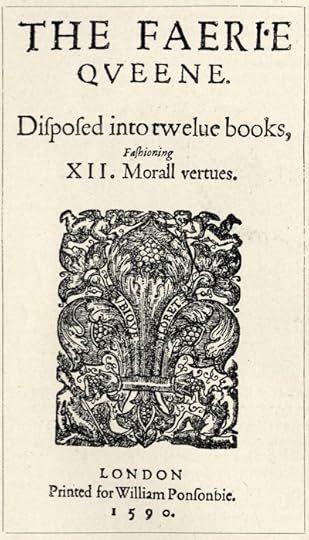

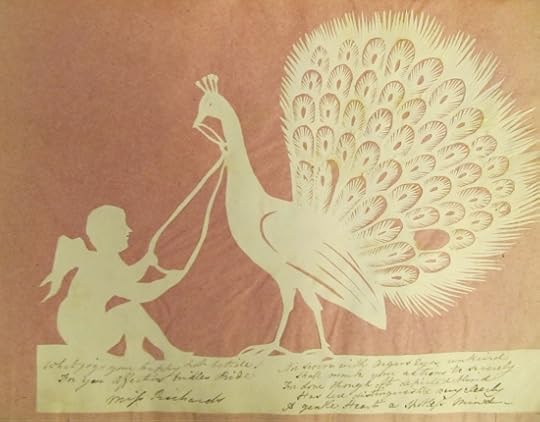

Pierre and Marie Curie in their laboratory, 1898. (Photo12/UIG via Getty Images) Queen Victoria mourns Prince AlbertOne of history’s most popular royal partnerships, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert reigned together for 21 years. Married in 1840, the couple had nine children together and shared the daily duties of royal life. However, the family’s domestic and political stability was shattered on 14 December 1861 when Albert died unexpectedly. A generally healthy man of 42, the prince’s sudden death from typhoid caught both the queen and the nation off-guard. Historian Helen Rappaport suggests that Albert’s death was “nothing less than a national calamity”. Over the years Albert had assumed many of the functions of a reigning monarch, sharing Victoria’s mountain of royal duties and masterminding popular projects such the 1851 Great Exhibition and South Kensington museums complex. Victoria quickly descended into what Rappaport calls a “crippling state of unrelenting grief”. She had not only been reliant on Albert’s help dealing with royal and business affairs, but was intensely dependent on him emotionally. According to Rappaport, “Albert had been all in all to Victoria: husband, friend, confidant, wise counsel, unofficial secretary and government minister. There was not a single aspect of her life on which she had not deferred to his advice and greater wisdom”. She suggests that “Albert had been her one great, abiding obsession in life. Without him Victoria felt rudderless”. This intense grieving quickly created serious problems. Victoria began to take up rigorous and ritualistic observances of bereavement, which lasted far longer than the two-year mourning period conventional at the time. Her reluctance to appear in public and decision to wear black for the rest of her life earned her the nickname the ‘Widow of Windsor’. Helen Rappaport suggests that through these actions, Victoria was “turning her grieving into performance art, retreating into a state of pathological grief which nobody could penetrate and few understood”. Over time, the queen’s sombre retreat from public life significantly impacted on her popularity, with growing complaints that she did nothing to justify her income. Victoria never fully recovered from Albert’s death. She commissioned several monuments in his honour, including the Royal Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens, which was completed in 1876. She remained in mourning for 40 years, until her own death aged 81.  Queen Victoria in mourning shortly after the death of her husband Albert, 1862. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Shakespeare writes sonnets to the Dark LadySome of the most acclaimed romantic poetry of all time, Shakespeare’s sonnets 127–154 celebrate the beauty of a Dark Lady. These sonnets have gone down in history as some of the Bard’s most romantic and erotic, with oft-quoted lines such as “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun/Coral is far more red, than her lips red… And yet by heaven I think my love as rare/As any she belied with false compare”. However, the identity of the Dark Lady addressed in the poems remains unknown, and has proved to be one of literature’s greatest mysteries. What does Shakespeare reveal to readers about his mysterious mistress? He portrays her as an erotic temptress: sonnet 144 addresses her as “my female evil” and “my bad angel”. Other sonnets tell us of her black hair and “raven black” eyes, and celebrate her dark complexion: “Thy black is fairest in my judgement’s place”, “beauty herself is black”. Shakespeare’s relationship with the Dark Lady has intrigued scholars for centuries, and there are a multitude of theories about her identity. Dr Aubrey Burl has recently argued that the Dark Lady is Aline Florio, the wife of an Italian translator. Meanwhile, Dr Duncan Salkeld has identified her as Lucy Morgan, a Clerkenwell prostitute also known as ‘Black Luce’. Other possible candidates for the Dark Lady have included a courtesan, a landlady, a wigmaker’s wife and even a lady-in-waiting of Queen Elizabeth I, Mary Fitton. However, it’s unlikely that we will ever know for certain the identity of the alluring lady who inspired such remarkable poetry, or the extent of Shakespeare’s relationship with her. Shah Jahan builds the Taj MahalConstructed between 1632 and 1653, the Taj Mahal in India is recognised across the world. However, as well as being an architectural marvel, it is also one of history’s greatest romantic gestures, from India’s Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan. In 1612 Shah Jahan married the Persian princess Arjumand Banu Begum. Mughal court poets claimed Arjumand’s beauty was so great that the moon hid its face in shame before her, and she reportedly enthralled the future emperor at first sight. Despite the fact that Shah Jahan had two other wives, Arjumand is generally acknowledged as being the love of his life. He even gave her the name “Mumtaz Mahal”, meaning ‘jewel of the palace’. A loyal and devoted wife, Begum accompanied her husband on various military campaigns, and the couple rarely spent time apart. In 1631, after 19 years of marriage, Mumtaz Mahal died giving birth to her 14th child. According to legend, distraught at his powerlessness to help her, Shah Jahan made a deathbed promise to build his wife the greatest tomb the world had ever seen. After a period of intense grieving, as promised he began work on an extraordinarily elaborate mausoleum to honour Mumtaz Mahal – the Taj Mahal. The Shah threw himself into the project, summoning the best dome-builders, masons, painters, calligraphers and other artisans from as far as Turkey and Iraq to work on it. No expense or painstaking detail was spared. Overall it took 22,000 labourers more than 21 years to complete the epic monument. Mumtaz Mahal’s cenotaph stands at the perfect centre of the symmetrical Taj, and upon his death Shah Jahan was placed alongside her. The Shah’s memorial to his beloved wife is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, attracting millions of visitors every year.

Queen Victoria in mourning shortly after the death of her husband Albert, 1862. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Shakespeare writes sonnets to the Dark LadySome of the most acclaimed romantic poetry of all time, Shakespeare’s sonnets 127–154 celebrate the beauty of a Dark Lady. These sonnets have gone down in history as some of the Bard’s most romantic and erotic, with oft-quoted lines such as “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun/Coral is far more red, than her lips red… And yet by heaven I think my love as rare/As any she belied with false compare”. However, the identity of the Dark Lady addressed in the poems remains unknown, and has proved to be one of literature’s greatest mysteries. What does Shakespeare reveal to readers about his mysterious mistress? He portrays her as an erotic temptress: sonnet 144 addresses her as “my female evil” and “my bad angel”. Other sonnets tell us of her black hair and “raven black” eyes, and celebrate her dark complexion: “Thy black is fairest in my judgement’s place”, “beauty herself is black”. Shakespeare’s relationship with the Dark Lady has intrigued scholars for centuries, and there are a multitude of theories about her identity. Dr Aubrey Burl has recently argued that the Dark Lady is Aline Florio, the wife of an Italian translator. Meanwhile, Dr Duncan Salkeld has identified her as Lucy Morgan, a Clerkenwell prostitute also known as ‘Black Luce’. Other possible candidates for the Dark Lady have included a courtesan, a landlady, a wigmaker’s wife and even a lady-in-waiting of Queen Elizabeth I, Mary Fitton. However, it’s unlikely that we will ever know for certain the identity of the alluring lady who inspired such remarkable poetry, or the extent of Shakespeare’s relationship with her. Shah Jahan builds the Taj MahalConstructed between 1632 and 1653, the Taj Mahal in India is recognised across the world. However, as well as being an architectural marvel, it is also one of history’s greatest romantic gestures, from India’s Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan. In 1612 Shah Jahan married the Persian princess Arjumand Banu Begum. Mughal court poets claimed Arjumand’s beauty was so great that the moon hid its face in shame before her, and she reportedly enthralled the future emperor at first sight. Despite the fact that Shah Jahan had two other wives, Arjumand is generally acknowledged as being the love of his life. He even gave her the name “Mumtaz Mahal”, meaning ‘jewel of the palace’. A loyal and devoted wife, Begum accompanied her husband on various military campaigns, and the couple rarely spent time apart. In 1631, after 19 years of marriage, Mumtaz Mahal died giving birth to her 14th child. According to legend, distraught at his powerlessness to help her, Shah Jahan made a deathbed promise to build his wife the greatest tomb the world had ever seen. After a period of intense grieving, as promised he began work on an extraordinarily elaborate mausoleum to honour Mumtaz Mahal – the Taj Mahal. The Shah threw himself into the project, summoning the best dome-builders, masons, painters, calligraphers and other artisans from as far as Turkey and Iraq to work on it. No expense or painstaking detail was spared. Overall it took 22,000 labourers more than 21 years to complete the epic monument. Mumtaz Mahal’s cenotaph stands at the perfect centre of the symmetrical Taj, and upon his death Shah Jahan was placed alongside her. The Shah’s memorial to his beloved wife is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, attracting millions of visitors every year.  Emperor Shah Jahan and his wife Mumtaz Mahal in a split picture from around 1640. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Edward VIII abdicates the throne in the name of loveSparking a crisis that rocked the British monarchy, Edward VIII’s decision in 1936 to give up the throne for a woman he loved undoubtedly deserves a place among history’s most romantic moments. Edward met Wallis Simpson, a chic, charismatic American socialite, in 1931 at a party hosted by his then-mistress, Thelma Furness. Despite Wallis being a married woman, by 1934 she and Edward had become lovers, to the immense disapproval of Edward’s family. The prince was no angel – he had a playboy reputation and had had several affairs. However, while his family tolerated a casual affair with Wallis, any suggestion of marriage was categorically ruled out. As a married woman seeking a second divorce, Wallis was an impossible consort for a future king and head of the Church of England. The couple came under intense pressure from all sides to end the affair. The king’s ministers, the Church of England and the royal family pleaded with Edward to terminate the relationship. Meanwhile, Wallis received death threats and was forced to retreat to France to escape her vilification in the British press as a “Yankee harlot”. Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen Mother, famously refused to acknowledge Wallis, referring to her only as “a certain person” or “that woman”. Despite all this, on 10 December 1936 Edward abdicated after only 325 days as king. His unexpected and unprecedented decision left his shy, stammering younger brother George VI to reluctantly assume the throne. Edward made his motives perfectly clear, declaring to the public “I have found it impossible to carry the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge my duties as king as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love.” Following Edward’s abdication and Wallis’s divorce, the couple married in a private ceremony in France. They embarked on a jet-setting lifestyle, living abroad together until Edward’s death in Paris in 1972. Heloise and Abelard exchange love lettersImmortalised through a series of intimate love letters, the doomed affair of Abelard and Heloise is one of the medieval period’s most compelling love stories. The tale began in 12th-century Paris, where Peter Abelard, a notable philosopher, was employed as a tutor. His pupil was Heloise d’Argenteuil, a brilliant student and the niece of a Parisian canon named Fulbert. Teacher and pupil became lovers and the unmarried Heloise found herself pregnant. Heloise’s age at the time is unclear, but some academics such as Constant Mews suggest she may have been as old as 27, with a significant scholarly reputation. Upon discovering the pregnancy Abelard proposed marriage, but Heloise was reluctant, in the knowledge that having a wife and family would jeopardise Abelard’s scholarship. According to her letters, she “never sought anything in you except yourself… looked for no marriage bond." Despite this reluctance, a wedding went ahead in secret, to avoid any damage to Abelard’s career. Heloise reportedly gave birth to a son, Astrolabe, but is not known what happened to him in later life. Things quickly fell disastrously apart. Angered by the affair’s damage to his reputation, Heloise’s uncle Fulbert spread news of the secret wedding and Abelard consequently placed Heloise in the convent of Argenteuil. Fulbert was so enraged by this that he had Abelard castrated in vengeance for his actions. Following the shame and trauma of his castration, Abelard became a monk at Paris’s Abbey of St Denis. Following his insistence that she do the same, Heloise too took holy orders and the couple retreated to a lifetime of celibacy in separate monasteries. However, they continued to correspond with each other through a series of letters, which document their earlier affair. The intimate and erotic content of these taboo-busting letters have for years intrigued academics. Heloise’s letters suggest that despite everything she did not regret the affair, reflecting “I should be groaning over the sins I have committed, but I can only sigh for what I have lost”.

Emperor Shah Jahan and his wife Mumtaz Mahal in a split picture from around 1640. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Edward VIII abdicates the throne in the name of loveSparking a crisis that rocked the British monarchy, Edward VIII’s decision in 1936 to give up the throne for a woman he loved undoubtedly deserves a place among history’s most romantic moments. Edward met Wallis Simpson, a chic, charismatic American socialite, in 1931 at a party hosted by his then-mistress, Thelma Furness. Despite Wallis being a married woman, by 1934 she and Edward had become lovers, to the immense disapproval of Edward’s family. The prince was no angel – he had a playboy reputation and had had several affairs. However, while his family tolerated a casual affair with Wallis, any suggestion of marriage was categorically ruled out. As a married woman seeking a second divorce, Wallis was an impossible consort for a future king and head of the Church of England. The couple came under intense pressure from all sides to end the affair. The king’s ministers, the Church of England and the royal family pleaded with Edward to terminate the relationship. Meanwhile, Wallis received death threats and was forced to retreat to France to escape her vilification in the British press as a “Yankee harlot”. Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen Mother, famously refused to acknowledge Wallis, referring to her only as “a certain person” or “that woman”. Despite all this, on 10 December 1936 Edward abdicated after only 325 days as king. His unexpected and unprecedented decision left his shy, stammering younger brother George VI to reluctantly assume the throne. Edward made his motives perfectly clear, declaring to the public “I have found it impossible to carry the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge my duties as king as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love.” Following Edward’s abdication and Wallis’s divorce, the couple married in a private ceremony in France. They embarked on a jet-setting lifestyle, living abroad together until Edward’s death in Paris in 1972. Heloise and Abelard exchange love lettersImmortalised through a series of intimate love letters, the doomed affair of Abelard and Heloise is one of the medieval period’s most compelling love stories. The tale began in 12th-century Paris, where Peter Abelard, a notable philosopher, was employed as a tutor. His pupil was Heloise d’Argenteuil, a brilliant student and the niece of a Parisian canon named Fulbert. Teacher and pupil became lovers and the unmarried Heloise found herself pregnant. Heloise’s age at the time is unclear, but some academics such as Constant Mews suggest she may have been as old as 27, with a significant scholarly reputation. Upon discovering the pregnancy Abelard proposed marriage, but Heloise was reluctant, in the knowledge that having a wife and family would jeopardise Abelard’s scholarship. According to her letters, she “never sought anything in you except yourself… looked for no marriage bond." Despite this reluctance, a wedding went ahead in secret, to avoid any damage to Abelard’s career. Heloise reportedly gave birth to a son, Astrolabe, but is not known what happened to him in later life. Things quickly fell disastrously apart. Angered by the affair’s damage to his reputation, Heloise’s uncle Fulbert spread news of the secret wedding and Abelard consequently placed Heloise in the convent of Argenteuil. Fulbert was so enraged by this that he had Abelard castrated in vengeance for his actions. Following the shame and trauma of his castration, Abelard became a monk at Paris’s Abbey of St Denis. Following his insistence that she do the same, Heloise too took holy orders and the couple retreated to a lifetime of celibacy in separate monasteries. However, they continued to correspond with each other through a series of letters, which document their earlier affair. The intimate and erotic content of these taboo-busting letters have for years intrigued academics. Heloise’s letters suggest that despite everything she did not regret the affair, reflecting “I should be groaning over the sins I have committed, but I can only sigh for what I have lost”.  A depiction of lovers Heloise and Abelard from a 13th century bible. (Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images) Henry VIII gets excommunicated in order to re-marryHenry VIII’s tempestuous relationship with Anne Boleyn is infamous for both its dramatic political consequences and its horrifying, bloody end. However, when Anne first joined the royal court in 1522, few could have anticipated the turbulence that would follow. Henry was not only married at the time, but also having an affair with Anne’s sister, Mary. What’s more, Historian Suzannah Lipscomb suggests that Anne was not an obvious choice for Henry’s future wife or even mistress, as he “wouldn’t have been bowled over by her good looks. The surprising thing about Anne is that she wasn’t considered to be a great beauty.” Instead, it was Anne’s wit, charm and continental sophistication that apparently infatuated the king, who became ardent in his pursuit of her. In a 1527 letter to Anne, Henry declared himself “struck by the dart of love” and asked her to “give herself body and heart to him”. The consequences of Henry’s infatuation were huge. As the Pope refused to annul his existing marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry broke with the Catholic Church and was subsequently excommunicated. He went on to form the Church of England, irrevocably changing the entire religious landscape of the nation. Following Henry’s break with Rome, he and Anne were married in January 1533. Anne was already pregnant at the time, with the future Queen Elizabeth I. Anne was crowned queen of England in an extravagant coronation ceremony later that year. The royal couple’s happiness was short-lived. Anne’s inability to produce a male heir, along with Henry’s growing infatuation with Jane Seymour, meant that the king was soon looking for a way out of the marriage for which he had sacrificed so much. Trumped-up adultery charges against Anne, her brother and three other men provided Henry with a way to be rid of his wife. After one of the men, Mark Smeaton, confessed under torture, the marriage was annulled and Anne’s fate sealed. The relationship reached its bitter and bloody end on 19 May 1536, with Anne’s execution on her husband’s orders.

A depiction of lovers Heloise and Abelard from a 13th century bible. (Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images) Henry VIII gets excommunicated in order to re-marryHenry VIII’s tempestuous relationship with Anne Boleyn is infamous for both its dramatic political consequences and its horrifying, bloody end. However, when Anne first joined the royal court in 1522, few could have anticipated the turbulence that would follow. Henry was not only married at the time, but also having an affair with Anne’s sister, Mary. What’s more, Historian Suzannah Lipscomb suggests that Anne was not an obvious choice for Henry’s future wife or even mistress, as he “wouldn’t have been bowled over by her good looks. The surprising thing about Anne is that she wasn’t considered to be a great beauty.” Instead, it was Anne’s wit, charm and continental sophistication that apparently infatuated the king, who became ardent in his pursuit of her. In a 1527 letter to Anne, Henry declared himself “struck by the dart of love” and asked her to “give herself body and heart to him”. The consequences of Henry’s infatuation were huge. As the Pope refused to annul his existing marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry broke with the Catholic Church and was subsequently excommunicated. He went on to form the Church of England, irrevocably changing the entire religious landscape of the nation. Following Henry’s break with Rome, he and Anne were married in January 1533. Anne was already pregnant at the time, with the future Queen Elizabeth I. Anne was crowned queen of England in an extravagant coronation ceremony later that year. The royal couple’s happiness was short-lived. Anne’s inability to produce a male heir, along with Henry’s growing infatuation with Jane Seymour, meant that the king was soon looking for a way out of the marriage for which he had sacrificed so much. Trumped-up adultery charges against Anne, her brother and three other men provided Henry with a way to be rid of his wife. After one of the men, Mark Smeaton, confessed under torture, the marriage was annulled and Anne’s fate sealed. The relationship reached its bitter and bloody end on 19 May 1536, with Anne’s execution on her husband’s orders.

Wallis and Edward, 1939. (Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Wallis and Edward, 1939. (Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images) Marie Curie dedicates her life to the work she began with her husband Perhaps science’s greatest power couple, Pierre Curie and Marie Sklodowskamet in 1894 at the Physics department of the Sorbonne University. Both idealists determined to dedicate their lives to science, they quickly discovered an intellectual like-mindedness. Pierre and Marie were married only a year later and together they embarked on groundbreaking work investigating radioactivity. In 1898 they announced their discovery of two new elements, radium and polonium, and went on to win a joint Nobel Prize for Physics in 1903. The Curie’s married life was dominated by their scientific study and laboratory work, which was often physically as well as mentally exhausting. Their constant exposure to radiation also saw them suffer significant health problems, from fatigue to skin scarring. Outside work, Marie and Pierre enjoyed long, adventurous cycling trips and had two daughters, Irene and Eve. The relationship was brought to a shocking and tragic end in 1906 when Pierre was killed unexpectedly, falling under a heavy horse-drawn cart after slipping in the street. After a period of intense mourning, Marie dedicated her life to pursuing the work they had begun together. She took over Pierre’s position at the Sorbonne, becoming the first woman ever to teach there, and went on to win a second Nobel Prize, for chemistry, in 1911. Through the First World War Marie continued to develop the work she had begun with her husband, as head of the International Red Cross radiology service. She worked tirelessly training medical orderlies and even driving ambulances with X-ray equipment to the front lines. After Marie’s death from aplastic anaemia [deficiency of blood cells caused by failure of bone marrow development] in 1934, brought on by the years of exposure to radioactive substances, she was buried alongside Pierre. Their remains were later moved to Paris’s Pantheon, in recognition of the groundbreaking discoveries they made together.

Pierre and Marie Curie in their laboratory, 1898. (Photo12/UIG via Getty Images) Queen Victoria mourns Prince AlbertOne of history’s most popular royal partnerships, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert reigned together for 21 years. Married in 1840, the couple had nine children together and shared the daily duties of royal life. However, the family’s domestic and political stability was shattered on 14 December 1861 when Albert died unexpectedly. A generally healthy man of 42, the prince’s sudden death from typhoid caught both the queen and the nation off-guard. Historian Helen Rappaport suggests that Albert’s death was “nothing less than a national calamity”. Over the years Albert had assumed many of the functions of a reigning monarch, sharing Victoria’s mountain of royal duties and masterminding popular projects such the 1851 Great Exhibition and South Kensington museums complex. Victoria quickly descended into what Rappaport calls a “crippling state of unrelenting grief”. She had not only been reliant on Albert’s help dealing with royal and business affairs, but was intensely dependent on him emotionally. According to Rappaport, “Albert had been all in all to Victoria: husband, friend, confidant, wise counsel, unofficial secretary and government minister. There was not a single aspect of her life on which she had not deferred to his advice and greater wisdom”. She suggests that “Albert had been her one great, abiding obsession in life. Without him Victoria felt rudderless”. This intense grieving quickly created serious problems. Victoria began to take up rigorous and ritualistic observances of bereavement, which lasted far longer than the two-year mourning period conventional at the time. Her reluctance to appear in public and decision to wear black for the rest of her life earned her the nickname the ‘Widow of Windsor’. Helen Rappaport suggests that through these actions, Victoria was “turning her grieving into performance art, retreating into a state of pathological grief which nobody could penetrate and few understood”. Over time, the queen’s sombre retreat from public life significantly impacted on her popularity, with growing complaints that she did nothing to justify her income. Victoria never fully recovered from Albert’s death. She commissioned several monuments in his honour, including the Royal Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens, which was completed in 1876. She remained in mourning for 40 years, until her own death aged 81.

Pierre and Marie Curie in their laboratory, 1898. (Photo12/UIG via Getty Images) Queen Victoria mourns Prince AlbertOne of history’s most popular royal partnerships, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert reigned together for 21 years. Married in 1840, the couple had nine children together and shared the daily duties of royal life. However, the family’s domestic and political stability was shattered on 14 December 1861 when Albert died unexpectedly. A generally healthy man of 42, the prince’s sudden death from typhoid caught both the queen and the nation off-guard. Historian Helen Rappaport suggests that Albert’s death was “nothing less than a national calamity”. Over the years Albert had assumed many of the functions of a reigning monarch, sharing Victoria’s mountain of royal duties and masterminding popular projects such the 1851 Great Exhibition and South Kensington museums complex. Victoria quickly descended into what Rappaport calls a “crippling state of unrelenting grief”. She had not only been reliant on Albert’s help dealing with royal and business affairs, but was intensely dependent on him emotionally. According to Rappaport, “Albert had been all in all to Victoria: husband, friend, confidant, wise counsel, unofficial secretary and government minister. There was not a single aspect of her life on which she had not deferred to his advice and greater wisdom”. She suggests that “Albert had been her one great, abiding obsession in life. Without him Victoria felt rudderless”. This intense grieving quickly created serious problems. Victoria began to take up rigorous and ritualistic observances of bereavement, which lasted far longer than the two-year mourning period conventional at the time. Her reluctance to appear in public and decision to wear black for the rest of her life earned her the nickname the ‘Widow of Windsor’. Helen Rappaport suggests that through these actions, Victoria was “turning her grieving into performance art, retreating into a state of pathological grief which nobody could penetrate and few understood”. Over time, the queen’s sombre retreat from public life significantly impacted on her popularity, with growing complaints that she did nothing to justify her income. Victoria never fully recovered from Albert’s death. She commissioned several monuments in his honour, including the Royal Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens, which was completed in 1876. She remained in mourning for 40 years, until her own death aged 81.  Queen Victoria in mourning shortly after the death of her husband Albert, 1862. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Shakespeare writes sonnets to the Dark LadySome of the most acclaimed romantic poetry of all time, Shakespeare’s sonnets 127–154 celebrate the beauty of a Dark Lady. These sonnets have gone down in history as some of the Bard’s most romantic and erotic, with oft-quoted lines such as “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun/Coral is far more red, than her lips red… And yet by heaven I think my love as rare/As any she belied with false compare”. However, the identity of the Dark Lady addressed in the poems remains unknown, and has proved to be one of literature’s greatest mysteries. What does Shakespeare reveal to readers about his mysterious mistress? He portrays her as an erotic temptress: sonnet 144 addresses her as “my female evil” and “my bad angel”. Other sonnets tell us of her black hair and “raven black” eyes, and celebrate her dark complexion: “Thy black is fairest in my judgement’s place”, “beauty herself is black”. Shakespeare’s relationship with the Dark Lady has intrigued scholars for centuries, and there are a multitude of theories about her identity. Dr Aubrey Burl has recently argued that the Dark Lady is Aline Florio, the wife of an Italian translator. Meanwhile, Dr Duncan Salkeld has identified her as Lucy Morgan, a Clerkenwell prostitute also known as ‘Black Luce’. Other possible candidates for the Dark Lady have included a courtesan, a landlady, a wigmaker’s wife and even a lady-in-waiting of Queen Elizabeth I, Mary Fitton. However, it’s unlikely that we will ever know for certain the identity of the alluring lady who inspired such remarkable poetry, or the extent of Shakespeare’s relationship with her. Shah Jahan builds the Taj MahalConstructed between 1632 and 1653, the Taj Mahal in India is recognised across the world. However, as well as being an architectural marvel, it is also one of history’s greatest romantic gestures, from India’s Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan. In 1612 Shah Jahan married the Persian princess Arjumand Banu Begum. Mughal court poets claimed Arjumand’s beauty was so great that the moon hid its face in shame before her, and she reportedly enthralled the future emperor at first sight. Despite the fact that Shah Jahan had two other wives, Arjumand is generally acknowledged as being the love of his life. He even gave her the name “Mumtaz Mahal”, meaning ‘jewel of the palace’. A loyal and devoted wife, Begum accompanied her husband on various military campaigns, and the couple rarely spent time apart. In 1631, after 19 years of marriage, Mumtaz Mahal died giving birth to her 14th child. According to legend, distraught at his powerlessness to help her, Shah Jahan made a deathbed promise to build his wife the greatest tomb the world had ever seen. After a period of intense grieving, as promised he began work on an extraordinarily elaborate mausoleum to honour Mumtaz Mahal – the Taj Mahal. The Shah threw himself into the project, summoning the best dome-builders, masons, painters, calligraphers and other artisans from as far as Turkey and Iraq to work on it. No expense or painstaking detail was spared. Overall it took 22,000 labourers more than 21 years to complete the epic monument. Mumtaz Mahal’s cenotaph stands at the perfect centre of the symmetrical Taj, and upon his death Shah Jahan was placed alongside her. The Shah’s memorial to his beloved wife is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, attracting millions of visitors every year.

Queen Victoria in mourning shortly after the death of her husband Albert, 1862. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Shakespeare writes sonnets to the Dark LadySome of the most acclaimed romantic poetry of all time, Shakespeare’s sonnets 127–154 celebrate the beauty of a Dark Lady. These sonnets have gone down in history as some of the Bard’s most romantic and erotic, with oft-quoted lines such as “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun/Coral is far more red, than her lips red… And yet by heaven I think my love as rare/As any she belied with false compare”. However, the identity of the Dark Lady addressed in the poems remains unknown, and has proved to be one of literature’s greatest mysteries. What does Shakespeare reveal to readers about his mysterious mistress? He portrays her as an erotic temptress: sonnet 144 addresses her as “my female evil” and “my bad angel”. Other sonnets tell us of her black hair and “raven black” eyes, and celebrate her dark complexion: “Thy black is fairest in my judgement’s place”, “beauty herself is black”. Shakespeare’s relationship with the Dark Lady has intrigued scholars for centuries, and there are a multitude of theories about her identity. Dr Aubrey Burl has recently argued that the Dark Lady is Aline Florio, the wife of an Italian translator. Meanwhile, Dr Duncan Salkeld has identified her as Lucy Morgan, a Clerkenwell prostitute also known as ‘Black Luce’. Other possible candidates for the Dark Lady have included a courtesan, a landlady, a wigmaker’s wife and even a lady-in-waiting of Queen Elizabeth I, Mary Fitton. However, it’s unlikely that we will ever know for certain the identity of the alluring lady who inspired such remarkable poetry, or the extent of Shakespeare’s relationship with her. Shah Jahan builds the Taj MahalConstructed between 1632 and 1653, the Taj Mahal in India is recognised across the world. However, as well as being an architectural marvel, it is also one of history’s greatest romantic gestures, from India’s Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan. In 1612 Shah Jahan married the Persian princess Arjumand Banu Begum. Mughal court poets claimed Arjumand’s beauty was so great that the moon hid its face in shame before her, and she reportedly enthralled the future emperor at first sight. Despite the fact that Shah Jahan had two other wives, Arjumand is generally acknowledged as being the love of his life. He even gave her the name “Mumtaz Mahal”, meaning ‘jewel of the palace’. A loyal and devoted wife, Begum accompanied her husband on various military campaigns, and the couple rarely spent time apart. In 1631, after 19 years of marriage, Mumtaz Mahal died giving birth to her 14th child. According to legend, distraught at his powerlessness to help her, Shah Jahan made a deathbed promise to build his wife the greatest tomb the world had ever seen. After a period of intense grieving, as promised he began work on an extraordinarily elaborate mausoleum to honour Mumtaz Mahal – the Taj Mahal. The Shah threw himself into the project, summoning the best dome-builders, masons, painters, calligraphers and other artisans from as far as Turkey and Iraq to work on it. No expense or painstaking detail was spared. Overall it took 22,000 labourers more than 21 years to complete the epic monument. Mumtaz Mahal’s cenotaph stands at the perfect centre of the symmetrical Taj, and upon his death Shah Jahan was placed alongside her. The Shah’s memorial to his beloved wife is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, attracting millions of visitors every year.  Emperor Shah Jahan and his wife Mumtaz Mahal in a split picture from around 1640. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Edward VIII abdicates the throne in the name of loveSparking a crisis that rocked the British monarchy, Edward VIII’s decision in 1936 to give up the throne for a woman he loved undoubtedly deserves a place among history’s most romantic moments. Edward met Wallis Simpson, a chic, charismatic American socialite, in 1931 at a party hosted by his then-mistress, Thelma Furness. Despite Wallis being a married woman, by 1934 she and Edward had become lovers, to the immense disapproval of Edward’s family. The prince was no angel – he had a playboy reputation and had had several affairs. However, while his family tolerated a casual affair with Wallis, any suggestion of marriage was categorically ruled out. As a married woman seeking a second divorce, Wallis was an impossible consort for a future king and head of the Church of England. The couple came under intense pressure from all sides to end the affair. The king’s ministers, the Church of England and the royal family pleaded with Edward to terminate the relationship. Meanwhile, Wallis received death threats and was forced to retreat to France to escape her vilification in the British press as a “Yankee harlot”. Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen Mother, famously refused to acknowledge Wallis, referring to her only as “a certain person” or “that woman”. Despite all this, on 10 December 1936 Edward abdicated after only 325 days as king. His unexpected and unprecedented decision left his shy, stammering younger brother George VI to reluctantly assume the throne. Edward made his motives perfectly clear, declaring to the public “I have found it impossible to carry the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge my duties as king as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love.” Following Edward’s abdication and Wallis’s divorce, the couple married in a private ceremony in France. They embarked on a jet-setting lifestyle, living abroad together until Edward’s death in Paris in 1972. Heloise and Abelard exchange love lettersImmortalised through a series of intimate love letters, the doomed affair of Abelard and Heloise is one of the medieval period’s most compelling love stories. The tale began in 12th-century Paris, where Peter Abelard, a notable philosopher, was employed as a tutor. His pupil was Heloise d’Argenteuil, a brilliant student and the niece of a Parisian canon named Fulbert. Teacher and pupil became lovers and the unmarried Heloise found herself pregnant. Heloise’s age at the time is unclear, but some academics such as Constant Mews suggest she may have been as old as 27, with a significant scholarly reputation. Upon discovering the pregnancy Abelard proposed marriage, but Heloise was reluctant, in the knowledge that having a wife and family would jeopardise Abelard’s scholarship. According to her letters, she “never sought anything in you except yourself… looked for no marriage bond." Despite this reluctance, a wedding went ahead in secret, to avoid any damage to Abelard’s career. Heloise reportedly gave birth to a son, Astrolabe, but is not known what happened to him in later life. Things quickly fell disastrously apart. Angered by the affair’s damage to his reputation, Heloise’s uncle Fulbert spread news of the secret wedding and Abelard consequently placed Heloise in the convent of Argenteuil. Fulbert was so enraged by this that he had Abelard castrated in vengeance for his actions. Following the shame and trauma of his castration, Abelard became a monk at Paris’s Abbey of St Denis. Following his insistence that she do the same, Heloise too took holy orders and the couple retreated to a lifetime of celibacy in separate monasteries. However, they continued to correspond with each other through a series of letters, which document their earlier affair. The intimate and erotic content of these taboo-busting letters have for years intrigued academics. Heloise’s letters suggest that despite everything she did not regret the affair, reflecting “I should be groaning over the sins I have committed, but I can only sigh for what I have lost”.

Emperor Shah Jahan and his wife Mumtaz Mahal in a split picture from around 1640. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Edward VIII abdicates the throne in the name of loveSparking a crisis that rocked the British monarchy, Edward VIII’s decision in 1936 to give up the throne for a woman he loved undoubtedly deserves a place among history’s most romantic moments. Edward met Wallis Simpson, a chic, charismatic American socialite, in 1931 at a party hosted by his then-mistress, Thelma Furness. Despite Wallis being a married woman, by 1934 she and Edward had become lovers, to the immense disapproval of Edward’s family. The prince was no angel – he had a playboy reputation and had had several affairs. However, while his family tolerated a casual affair with Wallis, any suggestion of marriage was categorically ruled out. As a married woman seeking a second divorce, Wallis was an impossible consort for a future king and head of the Church of England. The couple came under intense pressure from all sides to end the affair. The king’s ministers, the Church of England and the royal family pleaded with Edward to terminate the relationship. Meanwhile, Wallis received death threats and was forced to retreat to France to escape her vilification in the British press as a “Yankee harlot”. Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen Mother, famously refused to acknowledge Wallis, referring to her only as “a certain person” or “that woman”. Despite all this, on 10 December 1936 Edward abdicated after only 325 days as king. His unexpected and unprecedented decision left his shy, stammering younger brother George VI to reluctantly assume the throne. Edward made his motives perfectly clear, declaring to the public “I have found it impossible to carry the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge my duties as king as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love.” Following Edward’s abdication and Wallis’s divorce, the couple married in a private ceremony in France. They embarked on a jet-setting lifestyle, living abroad together until Edward’s death in Paris in 1972. Heloise and Abelard exchange love lettersImmortalised through a series of intimate love letters, the doomed affair of Abelard and Heloise is one of the medieval period’s most compelling love stories. The tale began in 12th-century Paris, where Peter Abelard, a notable philosopher, was employed as a tutor. His pupil was Heloise d’Argenteuil, a brilliant student and the niece of a Parisian canon named Fulbert. Teacher and pupil became lovers and the unmarried Heloise found herself pregnant. Heloise’s age at the time is unclear, but some academics such as Constant Mews suggest she may have been as old as 27, with a significant scholarly reputation. Upon discovering the pregnancy Abelard proposed marriage, but Heloise was reluctant, in the knowledge that having a wife and family would jeopardise Abelard’s scholarship. According to her letters, she “never sought anything in you except yourself… looked for no marriage bond." Despite this reluctance, a wedding went ahead in secret, to avoid any damage to Abelard’s career. Heloise reportedly gave birth to a son, Astrolabe, but is not known what happened to him in later life. Things quickly fell disastrously apart. Angered by the affair’s damage to his reputation, Heloise’s uncle Fulbert spread news of the secret wedding and Abelard consequently placed Heloise in the convent of Argenteuil. Fulbert was so enraged by this that he had Abelard castrated in vengeance for his actions. Following the shame and trauma of his castration, Abelard became a monk at Paris’s Abbey of St Denis. Following his insistence that she do the same, Heloise too took holy orders and the couple retreated to a lifetime of celibacy in separate monasteries. However, they continued to correspond with each other through a series of letters, which document their earlier affair. The intimate and erotic content of these taboo-busting letters have for years intrigued academics. Heloise’s letters suggest that despite everything she did not regret the affair, reflecting “I should be groaning over the sins I have committed, but I can only sigh for what I have lost”.  A depiction of lovers Heloise and Abelard from a 13th century bible. (Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images) Henry VIII gets excommunicated in order to re-marryHenry VIII’s tempestuous relationship with Anne Boleyn is infamous for both its dramatic political consequences and its horrifying, bloody end. However, when Anne first joined the royal court in 1522, few could have anticipated the turbulence that would follow. Henry was not only married at the time, but also having an affair with Anne’s sister, Mary. What’s more, Historian Suzannah Lipscomb suggests that Anne was not an obvious choice for Henry’s future wife or even mistress, as he “wouldn’t have been bowled over by her good looks. The surprising thing about Anne is that she wasn’t considered to be a great beauty.” Instead, it was Anne’s wit, charm and continental sophistication that apparently infatuated the king, who became ardent in his pursuit of her. In a 1527 letter to Anne, Henry declared himself “struck by the dart of love” and asked her to “give herself body and heart to him”. The consequences of Henry’s infatuation were huge. As the Pope refused to annul his existing marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry broke with the Catholic Church and was subsequently excommunicated. He went on to form the Church of England, irrevocably changing the entire religious landscape of the nation. Following Henry’s break with Rome, he and Anne were married in January 1533. Anne was already pregnant at the time, with the future Queen Elizabeth I. Anne was crowned queen of England in an extravagant coronation ceremony later that year. The royal couple’s happiness was short-lived. Anne’s inability to produce a male heir, along with Henry’s growing infatuation with Jane Seymour, meant that the king was soon looking for a way out of the marriage for which he had sacrificed so much. Trumped-up adultery charges against Anne, her brother and three other men provided Henry with a way to be rid of his wife. After one of the men, Mark Smeaton, confessed under torture, the marriage was annulled and Anne’s fate sealed. The relationship reached its bitter and bloody end on 19 May 1536, with Anne’s execution on her husband’s orders.

A depiction of lovers Heloise and Abelard from a 13th century bible. (Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images) Henry VIII gets excommunicated in order to re-marryHenry VIII’s tempestuous relationship with Anne Boleyn is infamous for both its dramatic political consequences and its horrifying, bloody end. However, when Anne first joined the royal court in 1522, few could have anticipated the turbulence that would follow. Henry was not only married at the time, but also having an affair with Anne’s sister, Mary. What’s more, Historian Suzannah Lipscomb suggests that Anne was not an obvious choice for Henry’s future wife or even mistress, as he “wouldn’t have been bowled over by her good looks. The surprising thing about Anne is that she wasn’t considered to be a great beauty.” Instead, it was Anne’s wit, charm and continental sophistication that apparently infatuated the king, who became ardent in his pursuit of her. In a 1527 letter to Anne, Henry declared himself “struck by the dart of love” and asked her to “give herself body and heart to him”. The consequences of Henry’s infatuation were huge. As the Pope refused to annul his existing marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry broke with the Catholic Church and was subsequently excommunicated. He went on to form the Church of England, irrevocably changing the entire religious landscape of the nation. Following Henry’s break with Rome, he and Anne were married in January 1533. Anne was already pregnant at the time, with the future Queen Elizabeth I. Anne was crowned queen of England in an extravagant coronation ceremony later that year. The royal couple’s happiness was short-lived. Anne’s inability to produce a male heir, along with Henry’s growing infatuation with Jane Seymour, meant that the king was soon looking for a way out of the marriage for which he had sacrificed so much. Trumped-up adultery charges against Anne, her brother and three other men provided Henry with a way to be rid of his wife. After one of the men, Mark Smeaton, confessed under torture, the marriage was annulled and Anne’s fate sealed. The relationship reached its bitter and bloody end on 19 May 1536, with Anne’s execution on her husband’s orders.

Published on February 16, 2016 03:30

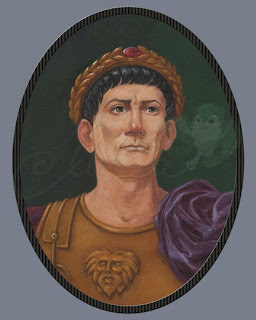

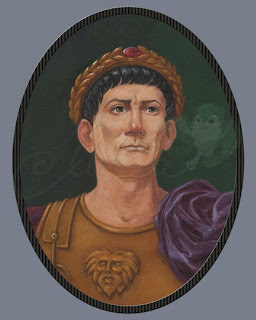

History Trivia - Trajan sends laureatae to Roman Senate

February 16

116 Emperor Trajan sent laureatae (word of military glory) to the Roman Senate at Rome on account of his victories and being conqueror of Parthia.

116 Emperor Trajan sent laureatae (word of military glory) to the Roman Senate at Rome on account of his victories and being conqueror of Parthia.

Published on February 16, 2016 01:30

February 15, 2016

Not such a prude after all: the secrets of Henry VIII’s love life

History Extra

Henry VIII courting Anne Boleyn. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Henry VIII courting Anne Boleyn. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)