MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 117

February 24, 2016

History Trivia - Pepin the Short dies

February 24

786 Pepin the Short of Gaul died. His dominions were divided between his sons Charles (Charlemagne) and Carloman.

786 Pepin the Short of Gaul died. His dominions were divided between his sons Charles (Charlemagne) and Carloman.

Published on February 24, 2016 01:00

February 23, 2016

In a nutshell: the Punic Wars

History Extra

17th-century painting of the Battle of Zama, a decisive victory for the Romans over Hannibal of Carthage. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

17th-century painting of the Battle of Zama, a decisive victory for the Romans over Hannibal of Carthage. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

What were they and who fought them?

The Punic Wars were a series of conflicts fought by the powerful cities of Carthage and Rome between 264 BC and 146 BC. The period is usually split into three distinct wars – the First was from 264-241 BC, the Second between 218-201 BC and the Third started in 149 BC and ended, bringing the Punic Wars to a conclusion, in 146 BC.

Why ‘Punic’?

The word ‘Punic’ actually comes from the word ‘Phoenician’ (phoinix in Greek or punicus in Latin), and refers to the citizens of Carthage, who were descended from the Phoenicians.

How and why did they begin?

Rome in 264 BC was a relatively small city – a far cry from its later superiority – and it was the city of Carthage (located in what we now know as Tunisia) that reigned supreme in the ancient world.

Tensions arose between the cities over who should have control of the strategic island of Sicily. Although relations were generally friendly, Rome’s intervention in a dispute on the island saw the cities explode into conflict. In 264 BC, war was officially declared for control of Sicily.

Rome built and equipped over 100 ships to take on the Carthaginian navy and finally, in 241 BC, was able to win a decisive victory against the Carthaginians at sea. In the peace treaty, Rome gained Sicily, its first overseas province.

Hannibal leads his Cathaginian army during the Second Punic War (Photo by Photo12/UIG/Getty Images)

Hannibal leads his Cathaginian army during the Second Punic War (Photo by Photo12/UIG/Getty Images)

Who were Hannibal and Scipio and what were their contributions to the conflict?

In 219 BC, Hannibal (son of Hamilcar Barca, a Carthaginian general during the First Punic War) broke the tentative peace between the two cities and laid siege to Saguntum (in eastern Spain), then an ally of Rome. Furious at Hannibal’s audacity, the Romans demanded that he be handed over for punishment. This order was ignored by the Carthaginian senate, and so the Second Punic War began.

Roman General Publius Cornelius Scipio, later known as Scipio Africanus, emerged in opposition to Hannibal during this conflict. Famously, the Carthaginian proceeded to march his forces over the Alps, along with his elephants, and conquered much of northern Italy.

Hannibal faced the Romans, including Scipio, at the Battle of Cannae in 216 BC – he won a great victory that saw some 70,000 Romans killed compared to just 6,000 Carthaginians.

Not a man to be beaten, Scipio – a admirer of Hannibal – turned the situation around at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC. Hannibal’s elephant charge was deflected back into the Carthaginian ranks, followed by a combined cavalry and infantry advance, which crushed Hannibal’s forces.

Carthage was ordered to surrender its navy, pay Rome a war debt of 200 talents of gold every year for 50 years, and was prevented from waging war with anyone without Roman approval.

The army, and war elephants, of Hannibal cross the Rhone River. (Photo by Stock Montage/Getty Images)

The army, and war elephants, of Hannibal cross the Rhone River. (Photo by Stock Montage/Getty Images)

If Carthage had been crushed, why did war break out for a third time in 149 BC?

Carthage paid its war debt to Rome over 50 years, until 149 BC. Then, deeming the treaty to be complete, the city went to war against Numidia, in what is now Algeria.

Not only did they lose the war, but Carthage incurred the wrath of Rome, who again deemed its old foe a threat. This time, Carthage was to be put down permanently.

That same year, a Roman embassy was sent to Carthage to demand that the city be dismantled and moved inland away from the coast. When the Carthaginians refused, the Third War broke out. Roman forces besieged Carthage for three years, until it finally fell in 146 BC. The city was sacked and burned to the ground where it lay in ruin for more than a century, with its inhabitants sold into slavery.

What were the long-term implications of the wars?

By the time the Punic Wars ended, Rome had blossomed from a small trading city into a formidable naval force. With no serious threat coming from Carthage, the Romans had the power to expand into an empire that would rule the known world.

17th-century painting of the Battle of Zama, a decisive victory for the Romans over Hannibal of Carthage. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

17th-century painting of the Battle of Zama, a decisive victory for the Romans over Hannibal of Carthage. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images) What were they and who fought them?

The Punic Wars were a series of conflicts fought by the powerful cities of Carthage and Rome between 264 BC and 146 BC. The period is usually split into three distinct wars – the First was from 264-241 BC, the Second between 218-201 BC and the Third started in 149 BC and ended, bringing the Punic Wars to a conclusion, in 146 BC.

Why ‘Punic’?

The word ‘Punic’ actually comes from the word ‘Phoenician’ (phoinix in Greek or punicus in Latin), and refers to the citizens of Carthage, who were descended from the Phoenicians.

How and why did they begin?

Rome in 264 BC was a relatively small city – a far cry from its later superiority – and it was the city of Carthage (located in what we now know as Tunisia) that reigned supreme in the ancient world.

Tensions arose between the cities over who should have control of the strategic island of Sicily. Although relations were generally friendly, Rome’s intervention in a dispute on the island saw the cities explode into conflict. In 264 BC, war was officially declared for control of Sicily.

Rome built and equipped over 100 ships to take on the Carthaginian navy and finally, in 241 BC, was able to win a decisive victory against the Carthaginians at sea. In the peace treaty, Rome gained Sicily, its first overseas province.

Hannibal leads his Cathaginian army during the Second Punic War (Photo by Photo12/UIG/Getty Images)

Hannibal leads his Cathaginian army during the Second Punic War (Photo by Photo12/UIG/Getty Images)Who were Hannibal and Scipio and what were their contributions to the conflict?

In 219 BC, Hannibal (son of Hamilcar Barca, a Carthaginian general during the First Punic War) broke the tentative peace between the two cities and laid siege to Saguntum (in eastern Spain), then an ally of Rome. Furious at Hannibal’s audacity, the Romans demanded that he be handed over for punishment. This order was ignored by the Carthaginian senate, and so the Second Punic War began.

Roman General Publius Cornelius Scipio, later known as Scipio Africanus, emerged in opposition to Hannibal during this conflict. Famously, the Carthaginian proceeded to march his forces over the Alps, along with his elephants, and conquered much of northern Italy.

Hannibal faced the Romans, including Scipio, at the Battle of Cannae in 216 BC – he won a great victory that saw some 70,000 Romans killed compared to just 6,000 Carthaginians.

Not a man to be beaten, Scipio – a admirer of Hannibal – turned the situation around at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC. Hannibal’s elephant charge was deflected back into the Carthaginian ranks, followed by a combined cavalry and infantry advance, which crushed Hannibal’s forces.

Carthage was ordered to surrender its navy, pay Rome a war debt of 200 talents of gold every year for 50 years, and was prevented from waging war with anyone without Roman approval.

The army, and war elephants, of Hannibal cross the Rhone River. (Photo by Stock Montage/Getty Images)

The army, and war elephants, of Hannibal cross the Rhone River. (Photo by Stock Montage/Getty Images)If Carthage had been crushed, why did war break out for a third time in 149 BC?

Carthage paid its war debt to Rome over 50 years, until 149 BC. Then, deeming the treaty to be complete, the city went to war against Numidia, in what is now Algeria.

Not only did they lose the war, but Carthage incurred the wrath of Rome, who again deemed its old foe a threat. This time, Carthage was to be put down permanently.

That same year, a Roman embassy was sent to Carthage to demand that the city be dismantled and moved inland away from the coast. When the Carthaginians refused, the Third War broke out. Roman forces besieged Carthage for three years, until it finally fell in 146 BC. The city was sacked and burned to the ground where it lay in ruin for more than a century, with its inhabitants sold into slavery.

What were the long-term implications of the wars?

By the time the Punic Wars ended, Rome had blossomed from a small trading city into a formidable naval force. With no serious threat coming from Carthage, the Romans had the power to expand into an empire that would rule the known world.

Published on February 23, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Diocletian persecutes Christians

Published on February 23, 2016 02:00

February 22, 2016

Britons were eating frogs' legs 8,000 years before the French

History Extra

They’ve long been considered a French delicacy, but a new archeological dig in Wiltshire suggests frogs' legs may have been first enjoyed in Britain.

They’ve long been considered a French delicacy, but a new archeological dig in Wiltshire suggests frogs' legs may have been first enjoyed in Britain.

Among evidence of life in the eighth millennia BC, found at the Blick Mead site at Amesbury, researchers from the University of Buckingham discovered the burnt leg bone of a toad.

The team also found small bones of trout or salmon, and burnt Aurochs bones (the predecessor of cows).

The finds date to between 6250BC and 7600BC, making the discovery the earliest evidence of a cooked toad or frog’s leg found in the world, and around eight millennia before the French.

David Jacques, senior research fellow in archaeology at the University of Buckingham, said: “It would appear that thousands of years ago people were eating a Heston Blumenthal-style menu on this site, one and a quarter miles from Stonehenge, consisting of toads’ legs, aurochs, wild boar and red deer with hazelnuts for main, another course of salmon and trout, and finishing off with blackberries.

“This is significant for our understanding of the way people were living around 5,000 years before the building of Stonehenge and it begs the question – where are the frogs now?”

The latest information is based on a report by fossil mammal specialist Simon Parfitt, of the Natural History Museum, who looked at the find.

The site already boasts one of the biggest collections of flints and cooked animal bones in northwestern Europe. It has resulted in 12,000 finds, all from the Mesolithic era, which fell between the Palaeolithic and the Neolithic.

The team hopes to confirm Amesbury as the UK's oldest continuous settlement. The dig, which will run until 25 October, is being filmed and made into a documentary by the BBC, to be screened at a later date.

Andy Rhind-Tutt, chairman of Amesbury Museum and Heritage Trust and co-ordinator of the community involvement on the dig, said the site at Blick Mead could help to explain why Stonehenge is where it is.

“No one would have built Stonehenge without there being something unique and really special about the area,” he said.

“There must have been something significant here beforehand and Blick Mead, with its constant temperature spring sitting alongside the river Avon, may well be it.

“I believe that as we uncover more about the site over the coming days and weeks, we will discover it to be the greatest, oldest and most significant Mesolithic home base ever found in Britain.”

They’ve long been considered a French delicacy, but a new archeological dig in Wiltshire suggests frogs' legs may have been first enjoyed in Britain.

They’ve long been considered a French delicacy, but a new archeological dig in Wiltshire suggests frogs' legs may have been first enjoyed in Britain.Among evidence of life in the eighth millennia BC, found at the Blick Mead site at Amesbury, researchers from the University of Buckingham discovered the burnt leg bone of a toad.

The team also found small bones of trout or salmon, and burnt Aurochs bones (the predecessor of cows).

The finds date to between 6250BC and 7600BC, making the discovery the earliest evidence of a cooked toad or frog’s leg found in the world, and around eight millennia before the French.

David Jacques, senior research fellow in archaeology at the University of Buckingham, said: “It would appear that thousands of years ago people were eating a Heston Blumenthal-style menu on this site, one and a quarter miles from Stonehenge, consisting of toads’ legs, aurochs, wild boar and red deer with hazelnuts for main, another course of salmon and trout, and finishing off with blackberries.

“This is significant for our understanding of the way people were living around 5,000 years before the building of Stonehenge and it begs the question – where are the frogs now?”

The latest information is based on a report by fossil mammal specialist Simon Parfitt, of the Natural History Museum, who looked at the find.

The site already boasts one of the biggest collections of flints and cooked animal bones in northwestern Europe. It has resulted in 12,000 finds, all from the Mesolithic era, which fell between the Palaeolithic and the Neolithic.

The team hopes to confirm Amesbury as the UK's oldest continuous settlement. The dig, which will run until 25 October, is being filmed and made into a documentary by the BBC, to be screened at a later date.

Andy Rhind-Tutt, chairman of Amesbury Museum and Heritage Trust and co-ordinator of the community involvement on the dig, said the site at Blick Mead could help to explain why Stonehenge is where it is.

“No one would have built Stonehenge without there being something unique and really special about the area,” he said.

“There must have been something significant here beforehand and Blick Mead, with its constant temperature spring sitting alongside the river Avon, may well be it.

“I believe that as we uncover more about the site over the coming days and weeks, we will discover it to be the greatest, oldest and most significant Mesolithic home base ever found in Britain.”

Published on February 22, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Battle of Cassel

February 22

1071 Battle of Cassel: Robert I the Frisian defeated Arnulf III who was killed in the battle. Robert became count of Flanders and ruled until 1093.

1071 Battle of Cassel: Robert I the Frisian defeated Arnulf III who was killed in the battle. Robert became count of Flanders and ruled until 1093.

Published on February 22, 2016 01:00

February 21, 2016

Medieval tourism: pilgrimages and tourist destinations

History Extra

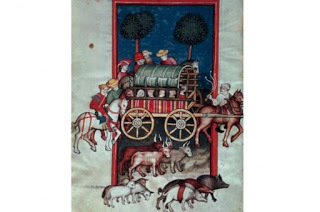

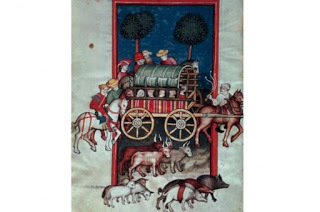

Jacob’s Journey, manuscript illumination, c1411. Hospitals and monastic houses would spring up alongside popular travel routes. (Credit: AKG Images)

One enduring perception of medieval Europe is of a static, confined world in which most people rarely travelled beyond their immediate locality, and when they did, movement was undertaken primarily for pragmatic reasons. Research in recent decades has significantly revised this picture – high numbers of people regularly travelled both short and long distances, and, more interestingly, some of this movement was driven by motivations which we might today associate with the modern-day tourist. If we readjust our modern understanding of tourism, and place it into a medieval context, we can soon see that many medieval people travelled for renewal, for leisure, and for thrill-seeking, and that an abundance of medieval ‘tourist’ services catered for these activities.

Southern Italy and Sicily, in the 11th and 12th centuries, offers a particularly vivid illustration of this phenomenon. Due to its position in the central Mediterranean, the region has always been pivotal to wider currents of movement and travel. And from the later 11th century it began to attract even more European visitors for three main reasons. Firstly, southern Italy and Sicily was conquered by bands of Normans who unified a region which had previously been politically fragmented and host to a patchwork of Greek Christians, Latin Christians, Jews and Muslims. Indeed, by 1130 the Normans had created a powerful new monarchy in the middle of the Mediterranean which had for centuries been dominated by Muslim sea-power. The Normans, therefore, enabled Christian shipping and travellers to move more securely and freely.

Secondly, various factors converged to boost the popularity of international pilgrimage, and after the beginning of the crusading movement in 1095 Europe experienced its golden era of devotional travel, much of which moved through southern Italy and Sicily en-route to Jerusalem.

Thirdly, in the 12th century, Europe underwent a cultural renaissance; learned individuals travelled further afield to seek knowledge, to uncover classical traditions, and to encounter alternative experiences. Southern Italy and Sicily, steeped in classical history and with a Greek and Islamic past,attracted visitors avid to imbibe both ancient and eastern learning. The result of these three combined strands saw an influx of visitors to the region, who were not migrants, conquerors, or traders, but travellers in their own right, what we might identify as tourists.

Scenes from the Life of Saint Stephen: Pilgrims at the Saint’s Tomb by Bernardo Daddi (c1290–1350). (Credit: Scala)

Pilgrimage offers perhaps the most apparent medieval equivalent of the tourist trade. Some pilgrims travelled not solely for pious motivations – a pilgrimage might cloak political and economic agendas, or be imposed as a judicial punishment. But whatever the incentive, adopting the pilgrim’s staff conferred a theoretical and universal status in which the individual acquired a new identity forged in the act of the journey to a particular shrine.

Between the pilgrimage’s start and end points, while the pilgrim was traversing alien territories, he was encouraged to imitate Christ, to experience challenge and hardship and to consider his own salvation. Indeed, at many shrines along their way, pilgrims practised an act known as incubation, in which they stayed and slept near the holy tomb, sometimes for days, in order to receive cures or divine revelations. In this sense, the pilgrim in his fundamentals was comparable to many modern-day travellers: an experiential traveller, absorbed in the act of journeying, partaking in a detox – not merely of the body as at a luxury spa, but also of the soul – like a modern meditative retreat achieved while on the move.

As international pilgrimage expanded dramatically in the central Middle Ages, southern Italy took on a key role in the pilgrim’s journey; it acted as a bridge to salvation by connecting two of the greatest shrine centres of the Christian world: Rome and Jerusalem.

This ‘bridge’ was a geographic reality. Southern Italy possessed one of medieval Europe’s more sophisticated travel infrastructures. Being so close to the heart of the former Roman empire, it still boasted several functioning Roman roads – the motorways of the Middle Ages – which linked into the Via Francigena, the main route that brought travellers from western Europe across the Alps to Rome. Roads such as the Via Appia and Via Traiana enabled travellers to move across the south Italian Apennines to the coastal ports of Apulia, while the Via Popillia wound through Calabria and directed visitors to the bustling Sicilian port of Messina. Thanks also to the Norman conquest, the region equally offered relatively safe maritime travel.

South Italian ports hosted fleets of well-informed local ships as well as those of the emergent commercial powers of Genoa, Pisa and Venice that traded in them.

Strong foundationsThe pilgrim could therefore rely on secure, efficient and direct travel connections. At the same time new hospitals, inns, bridges and monastic houses emerged along southern Italy’s main pilgrim routes, or near shrines which foreign visitors would attend.

The junctions at Capua, and Benevento, and the major Apulian and Sicilian ports (which often hosted pilgrim hospitals belonging to Holy Land military monastic orders – the Templars and Hospitallers), were full of such buildings offering shelter and sustenance to the traveller.

Unfortunately, as no reliable statistical data exists on how many travellers, pilgrims and crusaders (the three often indistinguishable) traversed these roads, and sailed to the Holy Land from these south Italian ports, we must rely on indirect evidence that suggests the region was one of the most frequented in the medieval world. This evidence can be found in the creation of all that travel infrastructure, and in contemporary accounts of the region’s ports teeming with travellers.

One commentator of the First Crusade noted that “many went to Brindisi, Otranto received others, while the waters of Bari welcomed more”. The Spanish Muslim traveller Ibn Jubayr, passing through Messina in 1184, described it as a frenetic port adapted to foreign travel; it was a “market of the merchant infidels [ie Christians], the focus of ships from the world over, and thronging always with companies of travellers by reason of the lowness of prices… Its markets are teeming, and it has ample commodities to ensure a luxurious life. Your days and nights in this town you will pass in full security.”

A 14th-century tin alloy pilgrim’s badge depicting the Madonna with child. (Credit: AKG Images)

Later, in the mid-13th century, the English chronicler Matthew Paris produced a superb illustrated strip-map showing a travel itinerary from London to the Holy Land in which he pinpointed Apulia and the port of Otranto as the best route, orientating the reader to Otranto pictorially through a series of symbols and the image of a boat.

The foreign visitors to the region were of diverse social status. Most of the surviving evidence focuses on elite travellers – kings, counts, bishops – primarily because their status and wealth drew comment. But travel, and pilgrimage in particular, was also undertaken by the very poorest. Monastic rules outlined their monks’ duty to offer free hospitality to travellers, and we have many instances of poor pilgrims visiting Christendom’s most far-flung shrines. One poverty-stricken man, for example, from southern Italy had been able to visit the Holy Sepulchre and the shrine of St Cataldus at Taranto primarily through the proceeds of begging. It was also good advertising for shrine centres to be seen to cater for all backgrounds. Indeed, attracting foreign visitors was, as it is today, desirable and lucrative – they spent money on local services and profitable tolls. Like today’s travel agents, the guardians of many of southern Italy’s shrine centres targeted, and competed for, travellers.

The iconography within some shrine complexes catered for the pilgrim’s transcendental mindset with images echoing the theme of salvation and depicting Christ as a pilgrim. Texts were also produced to show, for example at the shrine of St Nicholas the Pilgrim at Trani, that the saint entombed within had a particular penchant for saving pilgrims. The city of Benevento produced a treatise in c1100 which attempted to divert pilgrims to its own shrines and away from the popular one of St Nicholas’ at Bari by slandering the latter city’s hospitality towards foreign visitors; it claimed Bari was a “merciless land, without water, wine and bread”.

But many south Italian shrines did not need to produce such ‘travel brochures’, as they were already renowned across Europe. The likes of St Nicholas’ at Bari, St Matthew’s at Salerno, St Benedict’s at Montecassino and St Michael’s at Monte Gargano, received a vast influx of visitors, and provided vital spiritual release points as the pilgrim travelled to wherever his final destination may be.

Unsurprisingly, the Norman rulers of southern Italy were eager to portray themselves as protectors of pilgrims, and issued legislation to back this up. However, the need for protection also revealed the dangers of travel. The threat of robbery, shipwreck and disease was omnipresent. In the 1120s, the north Italian St William of Montevergine aborted his pilgrimage to Jerusalem after he had been mugged in Apulia; no wonder pilgrims often travelled in groups.

Many pilgrims suffered from debilitating conditions, and struggled to cope with the demands of medieval travel. Many died passing through southern Italy. One chronicler of the First Crusade saw the drowning of 400 pilgrims in Brindisi harbour. At least dying as a pilgrim brought the hope of salvation – the medieval equivalent of travel insurance.

Southern Italy also served not merely as a logistical bridge to salvation, but as a metaphorical one too. These potentially fatal outcomes were indeed part of the experience and attraction of travel that many pilgrims embraced. Redemption required suffering and this could certainly be found in the demanding setting of southern Italy and Sicily. In modern terms the region provided a superb outdoor adventure experience for the thrill seeker, a sinister landscape steeped in supernatural, classical and folkloric traditions which were channelled back to western Europe as travel increased in the central Middle Ages.

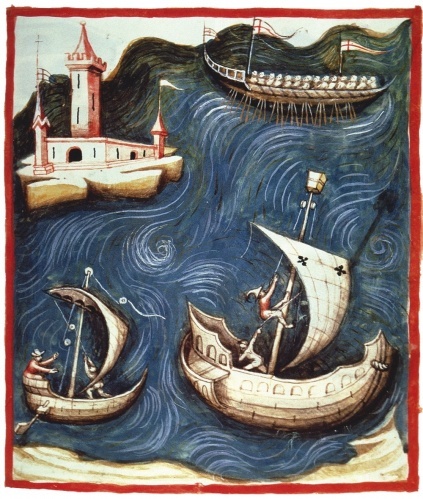

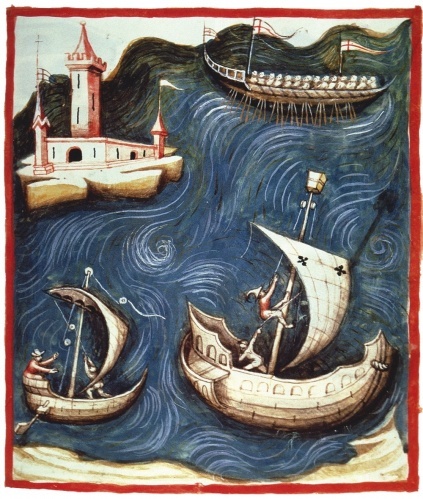

Fearsome tidesSouthern Italy’s landscape was characterised by features that elicited wonder and fear. Its surrounding seas could be treacherous, especially the busy Straits of Messina, full of whirlpools and tidal rips. The Muslim traveller Ibn Jubayr described the waters as boiling like a cauldron, and suffered a near-fatal shipwreck in the Straits in the 1180s.

Unsurprisingly, it was here that classical legend located the two sea monsters named Charybdis and Scylla, a vortex and a giant multi-headed sea-dog respectively. Commentators like the Englishman Gervase of Tilbury attempted to de-bunk these legends in the 12th century (he believed the whirlpools were created by the release of winds trapped below the seabed) but in doing so showed that many believed them to be real and/or were avidly interested in such tales. Indeed, the famous Hereford Mappa Mundi, dating to the late 13th century, offers a particularly vivid portrayal of the two sea monsters lurking in Sicilian waters.

Boats on the Sea, 14th century. The treacherous waters around southern Italy gave rise to many myths and legends. (Credit: Bridgeman Art Library)

Southern Italy, as today, was also a hotspot for seismic activity. Several eruptions were attested in the Middle Ages at Vesuvius and Etna, while earthquakes were a regular feature: one which struck Sicily in 1169 was said to have killed 15,000 people at Catania. While some medieval commentators tried to analyse these events in a natural, scientific framework, many still viewed them as portentous signs, often indicating God’s disapproval.

The region’s volcanoes were endowed with even greater potency through a set of myths connecting them to the entrance to hell. Increased medieval interest in Virgil, the ancient poet and author of the Aeneid, led to renewed Vesuvius and the gateway to the Underworld; for it was there that Virgil’s hero Aeneas appears to have located it. Gervase of Tilbury noted the “spine-chilling cries of lamenting souls” heard in the vicinity of Vesuvius and who were apparently being purged in the Underworld.

Medieval commentators also spoke metaphorically of the “infernal torments” and “cauldrons” of Sicily. In the 12th century the diplomat Peter of Blois said that the island’s mountains “are the gates of death and hell, where men are swallowed by the earth and the living sink into hell”.

Land of legendsA strange and beguiling world materialised in 12th-century southern Italy, one that seemed to exist halfway between heaven and hell, and must have challenged the medieval visitor’s psychological landscape to its very core.

The reviving 12th-century interest in the classical past also contributed to the aura of curiosity, danger and attraction which southern Italy exerted on visitors. Alongside those ongoing tales of Scylla and Charybdis, we find the revival of legends on Virgil and his supernatural protection of Naples (where he was allegedly buried).

Gervase of Tilbury recorded some of these in detail: Virgil’s protection of the city from snakes, an Englishman who found Virgil’s bones in the 1190s with a book of magic, and the city gate where Virgil bestowed good fortune on those passing through the correct side.

Dante and Virgil, the Dragon and the Sea Monster, from The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri. (Credit: Bridgeman Art Library)

In c1170 a Spanish Jewish traveller, Benjamin of Tudela, passed Pozzuoli near Naples and marvelled at the sight of an ancient city submerged just off the coast where “one can still see the markets and towers which stood in the midst of the city”. Benjamin also noted Pozzuoli’s famous hot spring baths which “all the afflicted of Lombardy visit [...] in the summertime” to benefit from the restorative properties of its waters. Indeed, many travellers also came to the region to access and benefit from cutting-edge medical knowledge, the fusion of Arabic and ancient Greek learning, available at the great medical school of Salerno.

Another 12th-century English author, Roger of Howden, also included within one of his chronicles a literary tourist guide highlighting sites in southern Italy associated with Pontius Pilate and Virgil. The great 13th-century preacher Jacques de Vitry railed against people travelling to witness the bizarre, and it is clear that many of the accounts we have mentioned were tailored for an inquisitive audience, a segment of which were more than likely to visit southern Italy.

It would seem therefore that medieval travellers displayed traits which reflect aspects of our modern understanding of tourist travel, and particularly the trend for travel which produced transformative and morally meaningful experiences. Of course, to avoid obvious anachronism, the parallels between medieval and modern must remain loose, and account for the multiple differences that developed in the intervening centuries.

Nevertheless, medieval people travelled regularly, and sometimes long distances, encountering lands that were unfamiliar and challenging. But these challenges and new experiences were actually often sought as ends in themselves. Southern Italy encapsulated these trends – and offered an experience for travellers in all their guises. It had developed travel and service infrastructures, it catered for those seeking spiritual detox, for those who were interested in the distant past and in intellectual nourishment, and for those who sought physical and psychological tests – its volcanoes, earthquakes, volatile seas, and entrances to the Underworld made the region akin to a modern-day theme park.

For the medieval traveller, salvation, life enrichment and damnation all sat together in southern Italy – helping to create an alluring travel hotspot.Dr Paul Oldfield is a senior lecturer in medieval history at the University of Manchester.

Jacob’s Journey, manuscript illumination, c1411. Hospitals and monastic houses would spring up alongside popular travel routes. (Credit: AKG Images)

One enduring perception of medieval Europe is of a static, confined world in which most people rarely travelled beyond their immediate locality, and when they did, movement was undertaken primarily for pragmatic reasons. Research in recent decades has significantly revised this picture – high numbers of people regularly travelled both short and long distances, and, more interestingly, some of this movement was driven by motivations which we might today associate with the modern-day tourist. If we readjust our modern understanding of tourism, and place it into a medieval context, we can soon see that many medieval people travelled for renewal, for leisure, and for thrill-seeking, and that an abundance of medieval ‘tourist’ services catered for these activities.

Southern Italy and Sicily, in the 11th and 12th centuries, offers a particularly vivid illustration of this phenomenon. Due to its position in the central Mediterranean, the region has always been pivotal to wider currents of movement and travel. And from the later 11th century it began to attract even more European visitors for three main reasons. Firstly, southern Italy and Sicily was conquered by bands of Normans who unified a region which had previously been politically fragmented and host to a patchwork of Greek Christians, Latin Christians, Jews and Muslims. Indeed, by 1130 the Normans had created a powerful new monarchy in the middle of the Mediterranean which had for centuries been dominated by Muslim sea-power. The Normans, therefore, enabled Christian shipping and travellers to move more securely and freely.

Secondly, various factors converged to boost the popularity of international pilgrimage, and after the beginning of the crusading movement in 1095 Europe experienced its golden era of devotional travel, much of which moved through southern Italy and Sicily en-route to Jerusalem.

Thirdly, in the 12th century, Europe underwent a cultural renaissance; learned individuals travelled further afield to seek knowledge, to uncover classical traditions, and to encounter alternative experiences. Southern Italy and Sicily, steeped in classical history and with a Greek and Islamic past,attracted visitors avid to imbibe both ancient and eastern learning. The result of these three combined strands saw an influx of visitors to the region, who were not migrants, conquerors, or traders, but travellers in their own right, what we might identify as tourists.

Scenes from the Life of Saint Stephen: Pilgrims at the Saint’s Tomb by Bernardo Daddi (c1290–1350). (Credit: Scala)

Pilgrimage offers perhaps the most apparent medieval equivalent of the tourist trade. Some pilgrims travelled not solely for pious motivations – a pilgrimage might cloak political and economic agendas, or be imposed as a judicial punishment. But whatever the incentive, adopting the pilgrim’s staff conferred a theoretical and universal status in which the individual acquired a new identity forged in the act of the journey to a particular shrine.

Between the pilgrimage’s start and end points, while the pilgrim was traversing alien territories, he was encouraged to imitate Christ, to experience challenge and hardship and to consider his own salvation. Indeed, at many shrines along their way, pilgrims practised an act known as incubation, in which they stayed and slept near the holy tomb, sometimes for days, in order to receive cures or divine revelations. In this sense, the pilgrim in his fundamentals was comparable to many modern-day travellers: an experiential traveller, absorbed in the act of journeying, partaking in a detox – not merely of the body as at a luxury spa, but also of the soul – like a modern meditative retreat achieved while on the move.

As international pilgrimage expanded dramatically in the central Middle Ages, southern Italy took on a key role in the pilgrim’s journey; it acted as a bridge to salvation by connecting two of the greatest shrine centres of the Christian world: Rome and Jerusalem.

This ‘bridge’ was a geographic reality. Southern Italy possessed one of medieval Europe’s more sophisticated travel infrastructures. Being so close to the heart of the former Roman empire, it still boasted several functioning Roman roads – the motorways of the Middle Ages – which linked into the Via Francigena, the main route that brought travellers from western Europe across the Alps to Rome. Roads such as the Via Appia and Via Traiana enabled travellers to move across the south Italian Apennines to the coastal ports of Apulia, while the Via Popillia wound through Calabria and directed visitors to the bustling Sicilian port of Messina. Thanks also to the Norman conquest, the region equally offered relatively safe maritime travel.

South Italian ports hosted fleets of well-informed local ships as well as those of the emergent commercial powers of Genoa, Pisa and Venice that traded in them.

Strong foundationsThe pilgrim could therefore rely on secure, efficient and direct travel connections. At the same time new hospitals, inns, bridges and monastic houses emerged along southern Italy’s main pilgrim routes, or near shrines which foreign visitors would attend.

The junctions at Capua, and Benevento, and the major Apulian and Sicilian ports (which often hosted pilgrim hospitals belonging to Holy Land military monastic orders – the Templars and Hospitallers), were full of such buildings offering shelter and sustenance to the traveller.

Unfortunately, as no reliable statistical data exists on how many travellers, pilgrims and crusaders (the three often indistinguishable) traversed these roads, and sailed to the Holy Land from these south Italian ports, we must rely on indirect evidence that suggests the region was one of the most frequented in the medieval world. This evidence can be found in the creation of all that travel infrastructure, and in contemporary accounts of the region’s ports teeming with travellers.

One commentator of the First Crusade noted that “many went to Brindisi, Otranto received others, while the waters of Bari welcomed more”. The Spanish Muslim traveller Ibn Jubayr, passing through Messina in 1184, described it as a frenetic port adapted to foreign travel; it was a “market of the merchant infidels [ie Christians], the focus of ships from the world over, and thronging always with companies of travellers by reason of the lowness of prices… Its markets are teeming, and it has ample commodities to ensure a luxurious life. Your days and nights in this town you will pass in full security.”

A 14th-century tin alloy pilgrim’s badge depicting the Madonna with child. (Credit: AKG Images)

Later, in the mid-13th century, the English chronicler Matthew Paris produced a superb illustrated strip-map showing a travel itinerary from London to the Holy Land in which he pinpointed Apulia and the port of Otranto as the best route, orientating the reader to Otranto pictorially through a series of symbols and the image of a boat.

The foreign visitors to the region were of diverse social status. Most of the surviving evidence focuses on elite travellers – kings, counts, bishops – primarily because their status and wealth drew comment. But travel, and pilgrimage in particular, was also undertaken by the very poorest. Monastic rules outlined their monks’ duty to offer free hospitality to travellers, and we have many instances of poor pilgrims visiting Christendom’s most far-flung shrines. One poverty-stricken man, for example, from southern Italy had been able to visit the Holy Sepulchre and the shrine of St Cataldus at Taranto primarily through the proceeds of begging. It was also good advertising for shrine centres to be seen to cater for all backgrounds. Indeed, attracting foreign visitors was, as it is today, desirable and lucrative – they spent money on local services and profitable tolls. Like today’s travel agents, the guardians of many of southern Italy’s shrine centres targeted, and competed for, travellers.

The iconography within some shrine complexes catered for the pilgrim’s transcendental mindset with images echoing the theme of salvation and depicting Christ as a pilgrim. Texts were also produced to show, for example at the shrine of St Nicholas the Pilgrim at Trani, that the saint entombed within had a particular penchant for saving pilgrims. The city of Benevento produced a treatise in c1100 which attempted to divert pilgrims to its own shrines and away from the popular one of St Nicholas’ at Bari by slandering the latter city’s hospitality towards foreign visitors; it claimed Bari was a “merciless land, without water, wine and bread”.

But many south Italian shrines did not need to produce such ‘travel brochures’, as they were already renowned across Europe. The likes of St Nicholas’ at Bari, St Matthew’s at Salerno, St Benedict’s at Montecassino and St Michael’s at Monte Gargano, received a vast influx of visitors, and provided vital spiritual release points as the pilgrim travelled to wherever his final destination may be.

Unsurprisingly, the Norman rulers of southern Italy were eager to portray themselves as protectors of pilgrims, and issued legislation to back this up. However, the need for protection also revealed the dangers of travel. The threat of robbery, shipwreck and disease was omnipresent. In the 1120s, the north Italian St William of Montevergine aborted his pilgrimage to Jerusalem after he had been mugged in Apulia; no wonder pilgrims often travelled in groups.

Many pilgrims suffered from debilitating conditions, and struggled to cope with the demands of medieval travel. Many died passing through southern Italy. One chronicler of the First Crusade saw the drowning of 400 pilgrims in Brindisi harbour. At least dying as a pilgrim brought the hope of salvation – the medieval equivalent of travel insurance.

Southern Italy also served not merely as a logistical bridge to salvation, but as a metaphorical one too. These potentially fatal outcomes were indeed part of the experience and attraction of travel that many pilgrims embraced. Redemption required suffering and this could certainly be found in the demanding setting of southern Italy and Sicily. In modern terms the region provided a superb outdoor adventure experience for the thrill seeker, a sinister landscape steeped in supernatural, classical and folkloric traditions which were channelled back to western Europe as travel increased in the central Middle Ages.

Fearsome tidesSouthern Italy’s landscape was characterised by features that elicited wonder and fear. Its surrounding seas could be treacherous, especially the busy Straits of Messina, full of whirlpools and tidal rips. The Muslim traveller Ibn Jubayr described the waters as boiling like a cauldron, and suffered a near-fatal shipwreck in the Straits in the 1180s.

Unsurprisingly, it was here that classical legend located the two sea monsters named Charybdis and Scylla, a vortex and a giant multi-headed sea-dog respectively. Commentators like the Englishman Gervase of Tilbury attempted to de-bunk these legends in the 12th century (he believed the whirlpools were created by the release of winds trapped below the seabed) but in doing so showed that many believed them to be real and/or were avidly interested in such tales. Indeed, the famous Hereford Mappa Mundi, dating to the late 13th century, offers a particularly vivid portrayal of the two sea monsters lurking in Sicilian waters.

Boats on the Sea, 14th century. The treacherous waters around southern Italy gave rise to many myths and legends. (Credit: Bridgeman Art Library)

Southern Italy, as today, was also a hotspot for seismic activity. Several eruptions were attested in the Middle Ages at Vesuvius and Etna, while earthquakes were a regular feature: one which struck Sicily in 1169 was said to have killed 15,000 people at Catania. While some medieval commentators tried to analyse these events in a natural, scientific framework, many still viewed them as portentous signs, often indicating God’s disapproval.

The region’s volcanoes were endowed with even greater potency through a set of myths connecting them to the entrance to hell. Increased medieval interest in Virgil, the ancient poet and author of the Aeneid, led to renewed Vesuvius and the gateway to the Underworld; for it was there that Virgil’s hero Aeneas appears to have located it. Gervase of Tilbury noted the “spine-chilling cries of lamenting souls” heard in the vicinity of Vesuvius and who were apparently being purged in the Underworld.

Medieval commentators also spoke metaphorically of the “infernal torments” and “cauldrons” of Sicily. In the 12th century the diplomat Peter of Blois said that the island’s mountains “are the gates of death and hell, where men are swallowed by the earth and the living sink into hell”.

Land of legendsA strange and beguiling world materialised in 12th-century southern Italy, one that seemed to exist halfway between heaven and hell, and must have challenged the medieval visitor’s psychological landscape to its very core.

The reviving 12th-century interest in the classical past also contributed to the aura of curiosity, danger and attraction which southern Italy exerted on visitors. Alongside those ongoing tales of Scylla and Charybdis, we find the revival of legends on Virgil and his supernatural protection of Naples (where he was allegedly buried).

Gervase of Tilbury recorded some of these in detail: Virgil’s protection of the city from snakes, an Englishman who found Virgil’s bones in the 1190s with a book of magic, and the city gate where Virgil bestowed good fortune on those passing through the correct side.

Dante and Virgil, the Dragon and the Sea Monster, from The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri. (Credit: Bridgeman Art Library)

In c1170 a Spanish Jewish traveller, Benjamin of Tudela, passed Pozzuoli near Naples and marvelled at the sight of an ancient city submerged just off the coast where “one can still see the markets and towers which stood in the midst of the city”. Benjamin also noted Pozzuoli’s famous hot spring baths which “all the afflicted of Lombardy visit [...] in the summertime” to benefit from the restorative properties of its waters. Indeed, many travellers also came to the region to access and benefit from cutting-edge medical knowledge, the fusion of Arabic and ancient Greek learning, available at the great medical school of Salerno.

Another 12th-century English author, Roger of Howden, also included within one of his chronicles a literary tourist guide highlighting sites in southern Italy associated with Pontius Pilate and Virgil. The great 13th-century preacher Jacques de Vitry railed against people travelling to witness the bizarre, and it is clear that many of the accounts we have mentioned were tailored for an inquisitive audience, a segment of which were more than likely to visit southern Italy.

It would seem therefore that medieval travellers displayed traits which reflect aspects of our modern understanding of tourist travel, and particularly the trend for travel which produced transformative and morally meaningful experiences. Of course, to avoid obvious anachronism, the parallels between medieval and modern must remain loose, and account for the multiple differences that developed in the intervening centuries.

Nevertheless, medieval people travelled regularly, and sometimes long distances, encountering lands that were unfamiliar and challenging. But these challenges and new experiences were actually often sought as ends in themselves. Southern Italy encapsulated these trends – and offered an experience for travellers in all their guises. It had developed travel and service infrastructures, it catered for those seeking spiritual detox, for those who were interested in the distant past and in intellectual nourishment, and for those who sought physical and psychological tests – its volcanoes, earthquakes, volatile seas, and entrances to the Underworld made the region akin to a modern-day theme park.

For the medieval traveller, salvation, life enrichment and damnation all sat together in southern Italy – helping to create an alluring travel hotspot.Dr Paul Oldfield is a senior lecturer in medieval history at the University of Manchester.

Published on February 21, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Thomas Becket canonized

February 21

1173 Thomas Becket was canonized. The Archbishop of Canterbury, one-time friend and opponent to King Henry II of England, had been murdered less than three years earlier, and the swift canonization by Pope Alexander III was a clear message of rebuke to the king.

1173 Thomas Becket was canonized. The Archbishop of Canterbury, one-time friend and opponent to King Henry II of England, had been murdered less than three years earlier, and the swift canonization by Pope Alexander III was a clear message of rebuke to the king.

Published on February 21, 2016 01:00

February 20, 2016

Fights, Drunks, Baths, and Excuses: Clues to Daily Life in the Roman Empire Via Latin Textbooks

Ancient Origins

A researcher translating Latin textbooks from the 2nd and 6th centuries has joined language learners of the past in discovering how to best deal with a variety of aspects of life in the Roman Empire. While many of the tasks described appear rather mundane, and include pointers on shopping, bathing, and dining, there are also some less apparent tips provided, such as how to deal with drunk relatives, handle being scolded, and picking fights. The texts are proving invaluable, as they offer hints on the social norms of the time for “ordinary Romans.”

Classics Professor Eleanor Dickey, of the University of Reading, has travelled around Europe and picked apart the details of ancient Latin school textbooks, or colloquia, which would have been used by young Greek speakers in the Roman empire learning Latin. Dickey has analyzed combined the manuscripts she recovered to create a book entitled Learning Latin the Ancient Way: Latin Textbooks in the Ancient World .

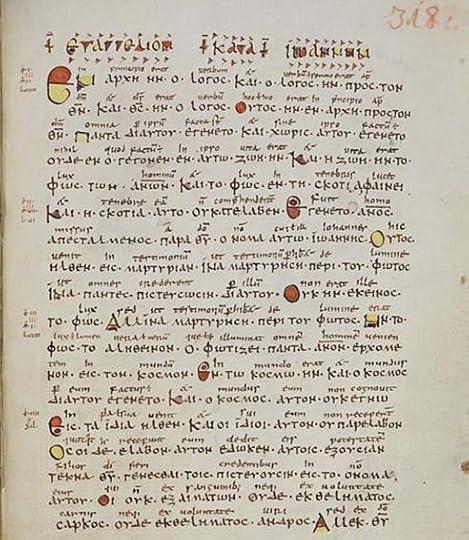

The beginning of the Gospel of John, in the Codex Sangallensis from the 9th century AD. (

Public Domain

) Latin text is written above the Greek.A blog by the University of Reading describes some of the “typical” situations that Greek students learning Latin could expect to experience while living in Roman society, and the importance of these texts for modern researchers:

The beginning of the Gospel of John, in the Codex Sangallensis from the 9th century AD. (

Public Domain

) Latin text is written above the Greek.A blog by the University of Reading describes some of the “typical” situations that Greek students learning Latin could expect to experience while living in Roman society, and the importance of these texts for modern researchers:“Ancient students studied short dialogues and narratives about daily life: buying clothes, buying food, having lunch, borrowing money, and visiting sick friends. Of course, ancient daily life was not quite like modern daily life, so the dialogues also cover going to the public baths, winning court cases, making excuses, getting into fights, taking oaths in temples, and coming home drunk after a Roman orgy. Just like their modern counterparts, these dialogues were written to teach students about culture as well as language; therefore they offer us priceless insight into life in the Roman empire as Romans saw it.”Swans Fat, Crocodile Dung, and Ashes of Snails: Achieving Beauty in Ancient RomeCould ancient textbooks be the source of the next medical breakthrough?Why the Romans were not quite as clean as you might have thought“When we think of the Romans, it’s mainly of the rich and famous generals, emperors and statesmen,” Dickey told the Guardian. She went on to say:

“But those people are clearly atypical: they’re famous precisely because they were remarkable. Historians try to correct this bias by telling us about the masses of ordinary Romans, but rarely do we have works written by or about these people. These colloquia give us real, contemporary stories about their lives and I hope my work gives a fairer and truer vision of ancient society.”One example comes in the form of a classic dialogue at the Roman baths. It follows the characters as they wrestle, are anointed with oil, enter the steam room and then proceed to a hot pool. This is followed by a shower and scraping off dirt with a metal instrument called a strigil. A section of the dialogue says:

“Let’s use the dry heat room and go down that way to the hot pool,” says one character. “Go down, pour hot water over me. Now get out. Throw yourself into the pool in the open air. Swim!” “I have swum.”

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]‘Ancient Ruins Used as Public Baths’ (1798) by Hubert Robert. ( Public Domain )“We learn all kinds of things we didn’t know here. When they come from the baths, they take a shower and scrape themselves off with a ‘strigil’,” Dickey explains. The need to use the strigil after being in the bath, suggests to Dickey that the bath may have made the characters even dirtier than they were after they wrestled. “We knew the baths were dirty, but not that they were this dirty,” Dickey said.

Exotic Goods and Foreign Luxuries: The Ancient Roman MarketplaceRats, Exploding Toilet Seats and Demons of the Deep: The Hazards of Roman SewersArbatel: The Magic of the Ancients – An Occult Grimoire with a Positive MessageNevertheless, Dickey’s book is not meant only as a window into life in the Roman Empire, but she also suggests its use for modern Latin students and teachers. She explains that many of the texts mirror modern language-learning books in providing authentic, real-life (at the time), and interesting dialogues. Much like today’s language learners, Greek students of the past “also used special beginners' versions of great Latin authors including Virgil and Cicero, and dictionaries, grammars, texts in Greek transliteration, etc.”

A 5th-century papyrus showing a parallel Latin-Greek text of a speech by Cicero. (

Public Domain

)Dickey told the Guardian that the texts were very commonly used. “We know this because they survive in lots of different medieval manuscript versions. At least six different versions were floating around Europe by 600 AD,” she said. “This is actually more common than many better-known ancient texts: there was only one copy of Catullus, and fewer than six of Caesar. Also, we have several papyrus fragments – since only a tiny fraction survive, when you have more than one papyrus fragment, for sure a text was popular in antiquity.”

A 5th-century papyrus showing a parallel Latin-Greek text of a speech by Cicero. (

Public Domain

)Dickey told the Guardian that the texts were very commonly used. “We know this because they survive in lots of different medieval manuscript versions. At least six different versions were floating around Europe by 600 AD,” she said. “This is actually more common than many better-known ancient texts: there was only one copy of Catullus, and fewer than six of Caesar. Also, we have several papyrus fragments – since only a tiny fraction survive, when you have more than one papyrus fragment, for sure a text was popular in antiquity.”Featured Image: A 12th-century manuscript with material copied from the earlier texts – an important source for Professor Dickey in her research. Source: Zisterzienserstift Zwettl

By Alicia McDermott

Published on February 20, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Orkney and Shetland islands given to Scotland

February 20

1472 Norway gave Orkney and Shetland islands to Scotland in lieu of a dowry for Margaret of Denmark.

1472 Norway gave Orkney and Shetland islands to Scotland in lieu of a dowry for Margaret of Denmark.

Published on February 20, 2016 02:00

February 19, 2016

Nameless Immigrants and Slaves in Rome, Who Were They? Where Did They Come from?

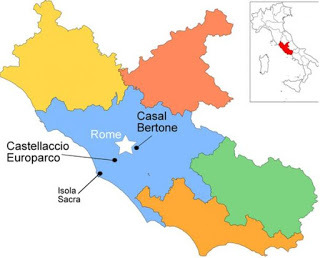

Map showing the location of the archaeological sites studied by Killgrove and Mongomery. ( Kristina Killgrove, Janet Montgomery )

Slaves and other lower-class residents made up a big part of the population of the city of Rome around the 1st century AD. But who were these people? Where were they from? What were their lives like?

Slaves and other lower-class residents made up a big part of the population of the city of Rome around the 1st century AD. But who were these people? Where were they from? What were their lives like? Two researchers are trying answer these questions by doing chemical analysis of teeth of lower-status residents of Rome, including children, women, slaves, and free immigrants.

The skeletal remains of thousands of ancient Romans survive, but it wasn’t until this new study by Kristina Killgrove and Janet Montgomery that archaeologists began to analyze chemical content of molars to answer some questions about migrations of some of Rome’s lower-profile inhabitants.

Dr. Killgrove, an anthropologist at the University of West Florida, and Dr. Montgomery, an archaeologist with Durham University in England, analyzed the strontium content of 105 molars of skeletons from two cemeteries in Rome and the carbon and oxygen of a subset of 55.

Their intent was to shed light on the lives of Romans who were not high-profile citizens, nobility or royalty. They looked at isotopes in the teeth of remains of people in two cemeteries in the city, Casal Bertone and Castellaccio Europarco.

It is well known that many people moved to Rome, but who these lower-status people were and what their lives were like are largely lost to history.

As stated in their article in the journal PLOS One , Killgrove and Montgomery wanted answer three main questions:

“Namely, this study begins to answer the questions: (a) Who migrated to Rome? (b) From where? and (c) What was their experience at their destination? When Rome as the center of an empire is approached anthropologically using all available data sources, migrants become actors and slaves become diasporic individuals, and the effects of population interaction on both locals and foreigners can be questioned in a novel way. … Modeling migration to Imperial Rome is necessary for a deeper understanding of demographics, family structure, and gender roles, and is particularly relevant for the vast majority of the Roman population that was left out of historical records.”Voluntary immigrants likely comprised about 5 percent of the Empire’s population in the 1st century AD, but slaves made up about 40 percent, they wrote. They continued on to write that many of the slaves were born locally, children of slave mothers, but some of them came from other areas of Italy or farther afield in the Empire.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]Painting of a Roman slave market, by Jean-Leon Gerome, circa 1884. ( Public Domain )Much is known about Roman citizens from historical documents, grave goods, architecture and other archaeological clues. But little is known about Roman slaves and other lower-class people. They wrote:

“The historical record is notoriously biased towards elite men with money, power, and literacy and may not represent accurately the lives of the average voluntary immigrant or slave. At Rome, slaves tended to be integrated into the household, so we cannot expect to find clear archaeological evidence of slavery in the same way as, for example, in the Southern U.S., with separate quarters or special pottery assemblages. The epigraphic [ancient writings] record is perhaps the most useful at identifying individual migrants, but only when a person is specifically commemorated as a foreigner.”By examining the isotopes, they were able tell in a general way where the person’s homeland was. Chemical content of food and water vary by geology, and the amounts of the isotopes in bones gives a general indication of where individuals lived and what they ate. The isotopes can also show what diseases they had.

The Mighty Wall of Hadrian, Emperor of Rome The legendary Spartacus: Gladiator and leader of slaves against the Romans – Part 1 Animal-bitten, Wounded, and Decapitated—Who were these Roman-era Men Buried near York? Why the Romans were not quite as clean as you might have thought “Both the strontium and the oxygen isotope ratios from Rome are diverse, and it is not unreasonable to assume that these may reflect the diversity of the population as well,” the authors wrote in their article for PLOS ONE. They also said that more studies of isotopes and DNA are necessary to understand the origins and homelands of the people buried at Roman cemeteries.

One of the conclusions they drew was that the people’s diets changed between the time they were children and when they died. Non-locals’ diets changed more dramatically, probably because the foods available to them in Rome differed compared to the foods of their homelands. “Whether this change was voluntary (to fit in with Roman foodways) or involuntary (because of food availability) is not clear,” they wrote.

.

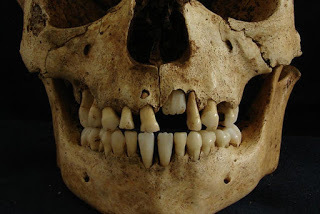

The skulls of two male immigrants found in Rome. (

Kristina Killgrove

)Among the 105 skeletons, they found just four who they could say were most likely not local—one from Africa and the others from the Alps and Apennines. They concluded that four others were likely not from Rome, though they were not certain on their origins.

The skulls of two male immigrants found in Rome. (

Kristina Killgrove

)Among the 105 skeletons, they found just four who they could say were most likely not local—one from Africa and the others from the Alps and Apennines. They concluded that four others were likely not from Rome, though they were not certain on their origins.“Given what we know from history, it is not surprising to find migrants among these skeletons, but it is a little surprising that we found so few,” Dr. Killgrove wrote in an article for Mental Floss. “The scale of slavery and migration to Rome during the Empire means we should expect more people to be migrants. However, isotope analysis cannot distinguish among people who were born in Rome and people who were born in another, isotopically similar location. We may be missing some migrants who are hidden within the data.”Some people moved to Rome to find work, education or a better life, she wrote, but many were forced to come and work as slaves. “We know from historical records that the scale of slavery in the Roman Empire dwarfed the amount of voluntary migration. Still, slavery in ancient Rome was often a temporary legal status, and manumission of slaves was common”

Live Science reports that Killgrove believes that having a better understanding of migration will deepen the knowledge on ancient Rome’s culture, Imperial Roman slavery, and even disease transmission. For these reasons she is continuing her work in another cemetery near Rome.

Featured image: Skull of a child around the age of seven from a Roman cemetery studied by Killgrove and Montgomery. Source: Kristina Killgrove

By Mark Miller

Published on February 19, 2016 03:00