MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 115

March 4, 2016

In a nutshell: the Holy Roman Empire

History Extra

Stained-glass window depicting Charlemagne, who was made Roman Emperor

Stained-glass window depicting Charlemagne, who was made Roman Emperor

What was it?The Holy Roman Empire was a notional realm in central Europe, which lasted for around 1,000 years, until 1806. Its name, however is rather misleading: the French philosopher Voltaire once decried the realm as “neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire”.

So why did it have that name?It was not until 1254 that the title of Holy Roman Empire was applied, but the origins of the name date back to AD 800, more than 300 years after the western half of the Roman Empire had collapsed. The Pope at that time, Leo III, was forced to flee Rome and, in desperation, he turned for help to Charlemagne, the powerful King of the Franks, who then ruled what is now roughly France and Germany. Charlemagne came to Leo’s aid. In AD 800, the grateful Pope crowned him as Roman Emperor as a gift.

How did the Empire develop after that?After Charlemagne’s death in AD 814, his squabbling heirs broke up the Empire and the title of Roman Emperor became fairly meaningless for over a century. It was revived by Otto I, King of the Eastern Franks (who ruled an area approximately equating to modern-day Germany), who had himself been crowned by Pope John XII in AD 962.

As with Charlemagne, Otto was crowned as a reward for having helped Pope John deal with his enemies in Italy. From that point, the Empire was chiefly centred on Germany, though it retained lands in Italy and elsewhere in central Europe.

This octagonal crown of the Holy Roman Empire was possibly made during Otto’s reignWhat relationship did these latter Roman Emperors have with the Popes?The Empire, having been created and reinforced by the papacy at times of trouble, enjoyed a complex and frequently difficult relationship with the bishops of Rome. The years after Otto’s reign were a high point for the Empire – at that time the most powerful in Europe – and a low one for the papacy.

This octagonal crown of the Holy Roman Empire was possibly made during Otto’s reignWhat relationship did these latter Roman Emperors have with the Popes?The Empire, having been created and reinforced by the papacy at times of trouble, enjoyed a complex and frequently difficult relationship with the bishops of Rome. The years after Otto’s reign were a high point for the Empire – at that time the most powerful in Europe – and a low one for the papacy.

A series of Roman Emperors took their title seriously and sought to dominate the Popes, even deposing those they didn’t approve of. By the mid 11-th century, however, the papacy was recovering and gaining power. In 1075, a lengthy battle for dominance between the Popes and Emperors, known as the Investiture Conflict, began.

The death in 1250 of Emperor Frederick II, following a failed campaign in Italy, marked the final defeat of the Empire in this clash. From then on, the link between the Popes and Emperors was largely broken. Though the Empire kept its title, it was greatly weakened, particularly as it took 23 years to settle the decision of who should succeed Frederick – the most extraordinary, intelligent and ambitious of the Emperors.

No longer seeking European domination, the Empire settled into a loose confederation of mainly German states, with the Emperor often marginalised.

How did the Empire come to an end?It was the French ruler Napoleon Bonaparte who oversaw the events that brought about the end of the Holy Roman Empire. Having declared himself heir to Charlemagne, Bonaparte aimed to add German lands to his growing empire. Seeing the writing on the wall, the last Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II, disbanded his realm in 1806.

The states of the Holy Roman Empire on a woodcut, c1510How was the Empire able to survive for so long?This may perhaps be because it didn’t have much power as a single, authoritative domain. It eventually came to comprise hundreds of territories, each of which enjoyed plenty of autonomy. For the rulers of many of these lands, the Empire offered a welcome alternative to a dominant or even tyrannical central power.

The states of the Holy Roman Empire on a woodcut, c1510How was the Empire able to survive for so long?This may perhaps be because it didn’t have much power as a single, authoritative domain. It eventually came to comprise hundreds of territories, each of which enjoyed plenty of autonomy. For the rulers of many of these lands, the Empire offered a welcome alternative to a dominant or even tyrannical central power.

Moreover, until the 19th century, concepts of nationalism were far less prevalent that they would go on to become, so there was little drive to unify the various German territories into one nation state.

What was the legacy of the Holy Roman Empire?When the German territories were unified as one country in 1871, it became known as the Reich (‘empire’ or ‘realm’). From 1933 to 1945, the Nazis sought to continue the Empire’s legacy by presiding over the Third Reich, which Hitler claimed would last 1,000 years. More recently, the idea of the later Holy Roman Empire has been reflected in the European union where, once again, a group of disparate countries has been brought together under a loose umbrella.

Submitted by: Jonny Wilkes

Stained-glass window depicting Charlemagne, who was made Roman Emperor

Stained-glass window depicting Charlemagne, who was made Roman Emperor What was it?The Holy Roman Empire was a notional realm in central Europe, which lasted for around 1,000 years, until 1806. Its name, however is rather misleading: the French philosopher Voltaire once decried the realm as “neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire”.

So why did it have that name?It was not until 1254 that the title of Holy Roman Empire was applied, but the origins of the name date back to AD 800, more than 300 years after the western half of the Roman Empire had collapsed. The Pope at that time, Leo III, was forced to flee Rome and, in desperation, he turned for help to Charlemagne, the powerful King of the Franks, who then ruled what is now roughly France and Germany. Charlemagne came to Leo’s aid. In AD 800, the grateful Pope crowned him as Roman Emperor as a gift.

How did the Empire develop after that?After Charlemagne’s death in AD 814, his squabbling heirs broke up the Empire and the title of Roman Emperor became fairly meaningless for over a century. It was revived by Otto I, King of the Eastern Franks (who ruled an area approximately equating to modern-day Germany), who had himself been crowned by Pope John XII in AD 962.

As with Charlemagne, Otto was crowned as a reward for having helped Pope John deal with his enemies in Italy. From that point, the Empire was chiefly centred on Germany, though it retained lands in Italy and elsewhere in central Europe.

This octagonal crown of the Holy Roman Empire was possibly made during Otto’s reignWhat relationship did these latter Roman Emperors have with the Popes?The Empire, having been created and reinforced by the papacy at times of trouble, enjoyed a complex and frequently difficult relationship with the bishops of Rome. The years after Otto’s reign were a high point for the Empire – at that time the most powerful in Europe – and a low one for the papacy.

This octagonal crown of the Holy Roman Empire was possibly made during Otto’s reignWhat relationship did these latter Roman Emperors have with the Popes?The Empire, having been created and reinforced by the papacy at times of trouble, enjoyed a complex and frequently difficult relationship with the bishops of Rome. The years after Otto’s reign were a high point for the Empire – at that time the most powerful in Europe – and a low one for the papacy.A series of Roman Emperors took their title seriously and sought to dominate the Popes, even deposing those they didn’t approve of. By the mid 11-th century, however, the papacy was recovering and gaining power. In 1075, a lengthy battle for dominance between the Popes and Emperors, known as the Investiture Conflict, began.

The death in 1250 of Emperor Frederick II, following a failed campaign in Italy, marked the final defeat of the Empire in this clash. From then on, the link between the Popes and Emperors was largely broken. Though the Empire kept its title, it was greatly weakened, particularly as it took 23 years to settle the decision of who should succeed Frederick – the most extraordinary, intelligent and ambitious of the Emperors.

No longer seeking European domination, the Empire settled into a loose confederation of mainly German states, with the Emperor often marginalised.

How did the Empire come to an end?It was the French ruler Napoleon Bonaparte who oversaw the events that brought about the end of the Holy Roman Empire. Having declared himself heir to Charlemagne, Bonaparte aimed to add German lands to his growing empire. Seeing the writing on the wall, the last Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II, disbanded his realm in 1806.

The states of the Holy Roman Empire on a woodcut, c1510How was the Empire able to survive for so long?This may perhaps be because it didn’t have much power as a single, authoritative domain. It eventually came to comprise hundreds of territories, each of which enjoyed plenty of autonomy. For the rulers of many of these lands, the Empire offered a welcome alternative to a dominant or even tyrannical central power.

The states of the Holy Roman Empire on a woodcut, c1510How was the Empire able to survive for so long?This may perhaps be because it didn’t have much power as a single, authoritative domain. It eventually came to comprise hundreds of territories, each of which enjoyed plenty of autonomy. For the rulers of many of these lands, the Empire offered a welcome alternative to a dominant or even tyrannical central power.Moreover, until the 19th century, concepts of nationalism were far less prevalent that they would go on to become, so there was little drive to unify the various German territories into one nation state.

What was the legacy of the Holy Roman Empire?When the German territories were unified as one country in 1871, it became known as the Reich (‘empire’ or ‘realm’). From 1933 to 1945, the Nazis sought to continue the Empire’s legacy by presiding over the Third Reich, which Hitler claimed would last 1,000 years. More recently, the idea of the later Holy Roman Empire has been reflected in the European union where, once again, a group of disparate countries has been brought together under a loose umbrella.

Submitted by: Jonny Wilkes

Published on March 04, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Battle at Towton: Yorkist victory

March 4

1461 Battle at Towton: Yorkists defeated the Lancstrians and Edward IV was recognized as king of England.

1461 Battle at Towton: Yorkists defeated the Lancstrians and Edward IV was recognized as king of England.

1461 Battle at Towton: Yorkists defeated the Lancstrians and Edward IV was recognized as king of England.

1461 Battle at Towton: Yorkists defeated the Lancstrians and Edward IV was recognized as king of England.

Published on March 04, 2016 02:30

March 3, 2016

How to build a medieval castle

History Extra

Built in the 1380s, the moated exterior of Bodiam Castle in East Sussex answers the popular ideal of a medieval castle. The building is brilliantly contrived to give the illusion of scale and rugged strength. © Alamy

Built in the 1380s, the moated exterior of Bodiam Castle in East Sussex answers the popular ideal of a medieval castle. The building is brilliantly contrived to give the illusion of scale and rugged strength. © Alamy

1) Choose your site carefullyIt is crucial that you build your castle at a prominent site in a position of strategic importance

Castles were commonly erected on naturally prominent sites, usually commanding a landscape or a communication link, such as a ford, bridge or pass.

It is rare to have a medieval account of the circumstances behind the choice of a castle site but they do exist. On 30 September 1223, the 15-year-old king Henry III arrived in Montgomery with an army. The king, having campaigned successfully against the Welsh prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, was intent on creating a new castle in the area to secure the border of his realm. Carpenters in England had been charged with preparing timber for the new fortifications a month previously, but the king’s advisers determined where the castle should be sited.

When it was started in 1223, Montgomery Castle in central Wales was sited on high ground – on a promontory above the valley of the river Severn. © Alamy

After surveying the area carefully they chose a spot on the very edge of a promontory above the valley of the river Severn. It was, in the words of the chronicler Roger of Wendover, a position “that seemed untakeable to everyone”. He also observed that the castle was “for the security of the region on account of the frequent attacks of the Welsh”.

Top tip: Identify the places where the topography dominates transport routes: these are natural sites for castles. Bear in mind that the castle’s design will be shaped by the building’s position. A castle on a high outcrop will, for example, have dry moats.

2) Agree on a workable design A master mason who can draw plans is a must – while an engineer who knows all about weapons is useful too

Experienced soldiers may have had ideas of their own about the design of their castle, in terms of the form of the buildings and their arrangement. But it’s unlikely they would have had any specialist knowledge in design or building.

What was needed to realise a vision was a master mason – an experienced builder whose distinguishing skill was the ability to draw. With an understanding of practical geometry he used the simple tools of a measuring rod, set-square and compass to create architectural designs. Master masons would present a drawn proposal for the castle for approval and when building commenced would oversee its construction.

When Edward II had a tower built at Knaresborough, he approved the plans himself and later demanded progress reports. © Alamy

When Edward II began building a great residential tower at Knaresborough Castle in Yorkshire for his favourite, Piers Gaveston, in 1307, he not only approved the design, created by the London master mason Hugh of Titchmarsh – presumably expressed as a drawing – but also demanded from him regular reports on the progress of the work. From the mid-16th century, a new group of professionals, termed engineers, increasingly came to dominate the design and construction of fortifications. They had a technical understanding of the use and power of cannon, both in protecting and reducing castle defences.

Top tip: Plan arrow slits carefully for a wide field of fire. Shape according to the weapons you use: longbow men need large splays (the oblique angles in the side of an opening in a wall); crossbow men less so.

3) Source a large, and skilled, workforce You’ll need thousands of men – not necessarily all there by choice

The labour required to build a great castle was vast. We have no documentary evidence for the numbers involved in the first great round of castle-building in England, after 1066, but the scale of many castles of this period makes it clear why some chronicles speak of the English population as being oppressed by the castle construction of their Norman conquerors.In the later Middle Ages, however, surviving building accounts offer detailed information.

During his first invasion of Wales, in 1277, Edward I began building a castle at Flint, north-east Wales. This was erected at speed, using the massive resources of the crown. Within a month of starting work, in August that year, 2,300 men were employed on site, including 1,270 diggers, 320 woodmen, 330 carpenters, 200 masons, 12 smiths and 10 charcoal burners. All these men were pressed into service from across the realm and accompanied into Wales with guards to prevent desertion.

Edward I employed 200 masons, like those shown above, on his castle at Flint in Wales. © AKG Images

In every period, foreign specialists were employed where necessary, often in senior roles. The millions of bricks needed to remodel Tattershall Castle, Lincolnshire during the 1440s, for example, were supplied by a certain Baldwin the ‘Docheman’ or Dutchman, evidently an immigrant.

Top tip: Depending on the size of your workforce and the distance it has travelled, it may be necessary to provide accommodation on site.

4) Secure the building site A work-in-progress in hostile territory is extremely vulnerable to attack from the enemy before it is ready

In order to build a castle in hostile territory it was essential to protect the site from attack. One way of doing this was to enclose the construction area within a timber fortification or low stone wall. Such medieval defences have sometimes been preserved in the completed building as an outer apron wall, as can be seen at Beaumaris, Anglesey, begun in 1295.

No less important was the need to secure communications with the outside world for the delivery of building materials and supplies. In 1277, for example, Edward I canalised the river Clwyd at vast expense from the sea to his new castle at Rhuddlan. Here, the apron wall built to protect the building site extended down to the quay on the banks of the river.

The building site of Rhuddlan Castle was protected by an outer wall. This formed a large enclosure that extended to the canalised river Clwyd. © Alamy

There might also have been concerns for security during major alterations to an existing castle. When Henry II remodelled Dover Castle, Kent in the 1180s, his building operation appears to have been carefully staggered so that the fortifications were continuously defensible throughout the construction process.

According to surviving royal accounts, work to the inner bailey wall was only begun when the great tower or keep was sufficiently complete to be garrisoned.

Top tip: Castle-building materials are big and bulky. If at all possible, try and move them by water, even if you have to build a dock or canal to do so.

5) Landscape the area Building a castle might involve moving a massive amount of earth, at great cost

It is often forgotten that castle fortifications were as much works of landscaping as of architecture. The resources involved in moving earth without pieces of machinery was necessarily enormous. Even after long neglect, the scale of Norman earthworks in particular can be extraordinary. It has been estimated, for example, that the vast artificial mound, termed a motte, erected in around 1100 at Pleshey Castle, Essex, required 24,000 days of labour to raise.

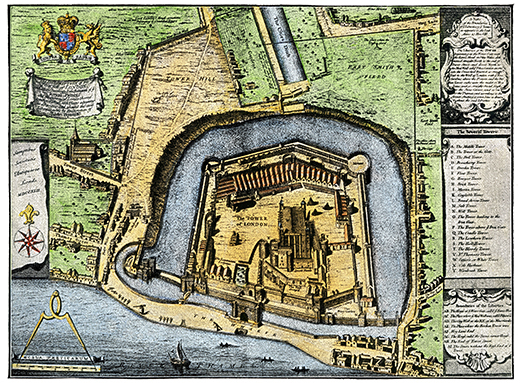

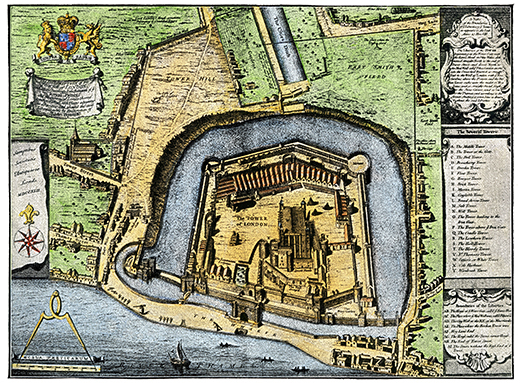

Some aspects of landscaping were also highly skilled, notably the creation of moats filled with water. When Edward I remodelled the Tower of London in the 1270s, he employed a foreign specialist, Walter of Flanders, to create a huge new tidal moat around the site. The ditching work that Walter supervised cost more than £4,000 to complete, an enormous sum that was nearly a quarter of the cost of the entire project.

This 18th-century engraving of a 1597 plan of the Tower of London shows how huge volumes of earth had to be shifted to build moats or ramparts. © AKG Images

As the use of cannon improved in siege warfare, earth became yet more important as a means of absorbing the impact of cannonballs. Curiously, the ability to move vast quantities of earth allowed some fortification engineers to find work creating gardens.

Top tip: Save on labour, expense and time by digging the masonry of your castle walls from the ditches around the castle site.

6) Lay the foundations Transfer the mason’s plan carefully to the ground

Using measured lengths of rope and pegs, it was possible to set out the foundations of a building in full scale on the ground. This was done by walking out the actions of a master mason’s drawing tools, his compass and set-square, to realise the plan. With foundation trenches dug, work began on the masonry structure. To save money, responsibility for construction was often deputed to a senior, rather than master, mason. The measurement of masonry usually used in the Middle Ages was the rod (16ft 6in, or 5m). At Warkworth, Northumberland, for example, the complex great tower is laid out on a grid of rods, probably for purposes of costing.

The great tower of Warkworth Castle, shown here, was laid out on a grid of rods. © Alamy

Medieval building processes are often well documented. In 1441–42, a tower at Tutbury Castle, Staffordshire was demolished and the plan for its successor laid out with ropes and pegs. The overseer, the Earl of Stafford, was for some reason dissatisfied. The king’s master mason, Robert of Westerley, was sent to Tutbury where he consulted with two senior masons to design a new tower on a different site. Westerley then left and over the next eight years a small group of workmen including four junior masons realised their new tower.

Senior masons could also be brought in to attest to the quality of work, as occurred at Cooling Castle, Kent, when the royal mason Henry Yevele surveyed work undertaken from 1381–84. He criticised departures from the original design and rounded down the bill.

Top tip: Don’t be cheated by your master mason. Make him design his building in such a way that it can be accurately costed.

7) Fortify your castle Finish with sophisticated defences and high-spec carpentry

Until the 12th century, the fortifications of most castles were comprised of earth and timber. While stone buildings predominated thereafter, wood remained a very important material in medieval warfare and fortification.

Stone castles were commonly prepared for hostilities by the addition of fighting galleries along walls (termed ‘brattices’ or ‘alures’) as well as shutters that could be hung between battlements to afford the defenders protection. All these fittings were made of wood. So too were the heavy weapons that were used to defend castles, including catapults and heavy crossbows termed ‘springalds’. This artillery was generally designed by a highly paid professional carpenter, sometimes termed an engineer or ‘ingeniator’.

A castle is stormed in this 15th-century illumination. To repel attacks, castles were often furnished with heavy weaponry. © Topfoto

Such expertise didn’t come cheap, but it could be worth its weight in gold. This was certainly the case in 1266, when Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire resisted Henry III for nearly six months, its catapults and water defences frustrating every attack.

There is even the occasional record of campaign castles being made entirely from wood, which could be transported and re-erected where needed. One such was built to cover a French invasion of England in 1386 but was captured on a ship by the Calais garrison. The castle was described as comprising a dense wall of timber 20ft high and 3,000 paces long. At every interval of 12 paces there rose up a 30ft tower capable of holding 10 soldiers, and there was some form of unspecified protection for gunners.

Top tip: Oak timber hardens with age after felling and is most easily worked when it is green. Pollarded trees (those with the upper branches removed) supply long clean limbs that can be easily transported and worked into shape with least labour.

8) Deal with water and sewage Don’t forget the mod cons. You’ll appreciate them if the castle is ever besieged

It was essential that castles were provided with an effective water supply. This could take the form of one or more wells dug to serve particular buildings such as the kitchen or stable. It can be hard to appreciate the sheer scale of medieval well shafts without descending them. That at Beeston Castle, Cheshire has a shaft 100m deep, which is lined in cut stone for the first 60m.

There is also occasional evidence for the sophisticated use of water in domestic apartments. The great tower at Dover Castle possesses a system of lead pipes delivering water throughout the interior. It was fed from a well using a winch system and possibly from rainwater too.

The effective disposal of human waste was another problem confronting castle designers. Latrines were grouped together within buildings so that the shafts descending from them could empty out of a common outlet. They were also set down short corridors to contain smells and were often furnished with fixed wooden seats and detachable lids.

The place to go: a gong, gang, privy or jake at Chipchase Castle. © Bridgeman

Castle latrines are often today popularly termed ‘garderobes’. In fact, the vocabulary for describing latrines in the Middle Ages was both colourful and broad. It included the words gong or gang (from the Anglo-Saxon meaning ‘the place to go’), privy and jake (a French form of ‘john’ or ‘johnny’).

Top tip: Ask your master mason to plan comfortable and private en-suite facilities off the principal bed chamber, following the example of Henry II at Dover Castle.

9) Decorate as required A castle doesn’t just have to be well defended – its high-status residents demand a certain swankiness too

Castles needed to be defensible in times of war but they also served as luxurious homes: the medieval nobility expected their accommodation to be both comfortable and well appointed. Throughout the Middle Ages these individuals travelled continuously with their attendant households, taking possessions and furniture with them from residence to residence. Important domestic interiors, however, commonly possessed permanent decorative fixtures such as stained-glass.

The decorative tastes of Henry III are recorded in particular and beguiling detail. In 1235–36, for example, he directed that his hall in Winchester Castle, Hampshire be painted with a map of the world and a ‘wheel of fortune’. This decoration has since been lost but the majestic interior does preserve the reputed round table of King Arthur – probably created between 1250 and 1280.

Castles were luxurious homes as well as strongholds. This is the 13th-century great hall at Winchester hung with the reputed round table of King Arthur. © Alamy

The wider setting of castles was also important for grand living. Parks were laid out for the jealously guarded aristocratic privilege of hunting, and there was a demand for gardens, too. The surviving building accounts for Kirby Muxloe Castle, Leicestershire reveal that its patron, Lord Hastings, began laying out the gardens at the very start of the building operations in 1480.

In the Middle Ages there was also a taste for rooms with fine views. One 13th-century group of rooms in castles that include Leeds in Kent, Corfe in Dorset and Chepstow, Monmouthshire, were named ‘gloriette’ after their splendour.

Top tip: Make sure the castle interior is splendid enough to attract visitors and friends. Entertainment can win battles without the danger of fighting.

John Goodall is an award-winning author, and architectural editor of the weekly magazine Country Life.

Built in the 1380s, the moated exterior of Bodiam Castle in East Sussex answers the popular ideal of a medieval castle. The building is brilliantly contrived to give the illusion of scale and rugged strength. © Alamy

Built in the 1380s, the moated exterior of Bodiam Castle in East Sussex answers the popular ideal of a medieval castle. The building is brilliantly contrived to give the illusion of scale and rugged strength. © Alamy 1) Choose your site carefullyIt is crucial that you build your castle at a prominent site in a position of strategic importance

Castles were commonly erected on naturally prominent sites, usually commanding a landscape or a communication link, such as a ford, bridge or pass.

It is rare to have a medieval account of the circumstances behind the choice of a castle site but they do exist. On 30 September 1223, the 15-year-old king Henry III arrived in Montgomery with an army. The king, having campaigned successfully against the Welsh prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, was intent on creating a new castle in the area to secure the border of his realm. Carpenters in England had been charged with preparing timber for the new fortifications a month previously, but the king’s advisers determined where the castle should be sited.

When it was started in 1223, Montgomery Castle in central Wales was sited on high ground – on a promontory above the valley of the river Severn. © Alamy

After surveying the area carefully they chose a spot on the very edge of a promontory above the valley of the river Severn. It was, in the words of the chronicler Roger of Wendover, a position “that seemed untakeable to everyone”. He also observed that the castle was “for the security of the region on account of the frequent attacks of the Welsh”.

Top tip: Identify the places where the topography dominates transport routes: these are natural sites for castles. Bear in mind that the castle’s design will be shaped by the building’s position. A castle on a high outcrop will, for example, have dry moats.

2) Agree on a workable design A master mason who can draw plans is a must – while an engineer who knows all about weapons is useful too

Experienced soldiers may have had ideas of their own about the design of their castle, in terms of the form of the buildings and their arrangement. But it’s unlikely they would have had any specialist knowledge in design or building.

What was needed to realise a vision was a master mason – an experienced builder whose distinguishing skill was the ability to draw. With an understanding of practical geometry he used the simple tools of a measuring rod, set-square and compass to create architectural designs. Master masons would present a drawn proposal for the castle for approval and when building commenced would oversee its construction.

When Edward II had a tower built at Knaresborough, he approved the plans himself and later demanded progress reports. © Alamy

When Edward II began building a great residential tower at Knaresborough Castle in Yorkshire for his favourite, Piers Gaveston, in 1307, he not only approved the design, created by the London master mason Hugh of Titchmarsh – presumably expressed as a drawing – but also demanded from him regular reports on the progress of the work. From the mid-16th century, a new group of professionals, termed engineers, increasingly came to dominate the design and construction of fortifications. They had a technical understanding of the use and power of cannon, both in protecting and reducing castle defences.

Top tip: Plan arrow slits carefully for a wide field of fire. Shape according to the weapons you use: longbow men need large splays (the oblique angles in the side of an opening in a wall); crossbow men less so.

3) Source a large, and skilled, workforce You’ll need thousands of men – not necessarily all there by choice

The labour required to build a great castle was vast. We have no documentary evidence for the numbers involved in the first great round of castle-building in England, after 1066, but the scale of many castles of this period makes it clear why some chronicles speak of the English population as being oppressed by the castle construction of their Norman conquerors.In the later Middle Ages, however, surviving building accounts offer detailed information.

During his first invasion of Wales, in 1277, Edward I began building a castle at Flint, north-east Wales. This was erected at speed, using the massive resources of the crown. Within a month of starting work, in August that year, 2,300 men were employed on site, including 1,270 diggers, 320 woodmen, 330 carpenters, 200 masons, 12 smiths and 10 charcoal burners. All these men were pressed into service from across the realm and accompanied into Wales with guards to prevent desertion.

Edward I employed 200 masons, like those shown above, on his castle at Flint in Wales. © AKG Images

In every period, foreign specialists were employed where necessary, often in senior roles. The millions of bricks needed to remodel Tattershall Castle, Lincolnshire during the 1440s, for example, were supplied by a certain Baldwin the ‘Docheman’ or Dutchman, evidently an immigrant.

Top tip: Depending on the size of your workforce and the distance it has travelled, it may be necessary to provide accommodation on site.

4) Secure the building site A work-in-progress in hostile territory is extremely vulnerable to attack from the enemy before it is ready

In order to build a castle in hostile territory it was essential to protect the site from attack. One way of doing this was to enclose the construction area within a timber fortification or low stone wall. Such medieval defences have sometimes been preserved in the completed building as an outer apron wall, as can be seen at Beaumaris, Anglesey, begun in 1295.

No less important was the need to secure communications with the outside world for the delivery of building materials and supplies. In 1277, for example, Edward I canalised the river Clwyd at vast expense from the sea to his new castle at Rhuddlan. Here, the apron wall built to protect the building site extended down to the quay on the banks of the river.

The building site of Rhuddlan Castle was protected by an outer wall. This formed a large enclosure that extended to the canalised river Clwyd. © Alamy

There might also have been concerns for security during major alterations to an existing castle. When Henry II remodelled Dover Castle, Kent in the 1180s, his building operation appears to have been carefully staggered so that the fortifications were continuously defensible throughout the construction process.

According to surviving royal accounts, work to the inner bailey wall was only begun when the great tower or keep was sufficiently complete to be garrisoned.

Top tip: Castle-building materials are big and bulky. If at all possible, try and move them by water, even if you have to build a dock or canal to do so.

5) Landscape the area Building a castle might involve moving a massive amount of earth, at great cost

It is often forgotten that castle fortifications were as much works of landscaping as of architecture. The resources involved in moving earth without pieces of machinery was necessarily enormous. Even after long neglect, the scale of Norman earthworks in particular can be extraordinary. It has been estimated, for example, that the vast artificial mound, termed a motte, erected in around 1100 at Pleshey Castle, Essex, required 24,000 days of labour to raise.

Some aspects of landscaping were also highly skilled, notably the creation of moats filled with water. When Edward I remodelled the Tower of London in the 1270s, he employed a foreign specialist, Walter of Flanders, to create a huge new tidal moat around the site. The ditching work that Walter supervised cost more than £4,000 to complete, an enormous sum that was nearly a quarter of the cost of the entire project.

This 18th-century engraving of a 1597 plan of the Tower of London shows how huge volumes of earth had to be shifted to build moats or ramparts. © AKG Images

As the use of cannon improved in siege warfare, earth became yet more important as a means of absorbing the impact of cannonballs. Curiously, the ability to move vast quantities of earth allowed some fortification engineers to find work creating gardens.

Top tip: Save on labour, expense and time by digging the masonry of your castle walls from the ditches around the castle site.

6) Lay the foundations Transfer the mason’s plan carefully to the ground

Using measured lengths of rope and pegs, it was possible to set out the foundations of a building in full scale on the ground. This was done by walking out the actions of a master mason’s drawing tools, his compass and set-square, to realise the plan. With foundation trenches dug, work began on the masonry structure. To save money, responsibility for construction was often deputed to a senior, rather than master, mason. The measurement of masonry usually used in the Middle Ages was the rod (16ft 6in, or 5m). At Warkworth, Northumberland, for example, the complex great tower is laid out on a grid of rods, probably for purposes of costing.

The great tower of Warkworth Castle, shown here, was laid out on a grid of rods. © Alamy

Medieval building processes are often well documented. In 1441–42, a tower at Tutbury Castle, Staffordshire was demolished and the plan for its successor laid out with ropes and pegs. The overseer, the Earl of Stafford, was for some reason dissatisfied. The king’s master mason, Robert of Westerley, was sent to Tutbury where he consulted with two senior masons to design a new tower on a different site. Westerley then left and over the next eight years a small group of workmen including four junior masons realised their new tower.

Senior masons could also be brought in to attest to the quality of work, as occurred at Cooling Castle, Kent, when the royal mason Henry Yevele surveyed work undertaken from 1381–84. He criticised departures from the original design and rounded down the bill.

Top tip: Don’t be cheated by your master mason. Make him design his building in such a way that it can be accurately costed.

7) Fortify your castle Finish with sophisticated defences and high-spec carpentry

Until the 12th century, the fortifications of most castles were comprised of earth and timber. While stone buildings predominated thereafter, wood remained a very important material in medieval warfare and fortification.

Stone castles were commonly prepared for hostilities by the addition of fighting galleries along walls (termed ‘brattices’ or ‘alures’) as well as shutters that could be hung between battlements to afford the defenders protection. All these fittings were made of wood. So too were the heavy weapons that were used to defend castles, including catapults and heavy crossbows termed ‘springalds’. This artillery was generally designed by a highly paid professional carpenter, sometimes termed an engineer or ‘ingeniator’.

A castle is stormed in this 15th-century illumination. To repel attacks, castles were often furnished with heavy weaponry. © Topfoto

Such expertise didn’t come cheap, but it could be worth its weight in gold. This was certainly the case in 1266, when Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire resisted Henry III for nearly six months, its catapults and water defences frustrating every attack.

There is even the occasional record of campaign castles being made entirely from wood, which could be transported and re-erected where needed. One such was built to cover a French invasion of England in 1386 but was captured on a ship by the Calais garrison. The castle was described as comprising a dense wall of timber 20ft high and 3,000 paces long. At every interval of 12 paces there rose up a 30ft tower capable of holding 10 soldiers, and there was some form of unspecified protection for gunners.

Top tip: Oak timber hardens with age after felling and is most easily worked when it is green. Pollarded trees (those with the upper branches removed) supply long clean limbs that can be easily transported and worked into shape with least labour.

8) Deal with water and sewage Don’t forget the mod cons. You’ll appreciate them if the castle is ever besieged

It was essential that castles were provided with an effective water supply. This could take the form of one or more wells dug to serve particular buildings such as the kitchen or stable. It can be hard to appreciate the sheer scale of medieval well shafts without descending them. That at Beeston Castle, Cheshire has a shaft 100m deep, which is lined in cut stone for the first 60m.

There is also occasional evidence for the sophisticated use of water in domestic apartments. The great tower at Dover Castle possesses a system of lead pipes delivering water throughout the interior. It was fed from a well using a winch system and possibly from rainwater too.

The effective disposal of human waste was another problem confronting castle designers. Latrines were grouped together within buildings so that the shafts descending from them could empty out of a common outlet. They were also set down short corridors to contain smells and were often furnished with fixed wooden seats and detachable lids.

The place to go: a gong, gang, privy or jake at Chipchase Castle. © Bridgeman

Castle latrines are often today popularly termed ‘garderobes’. In fact, the vocabulary for describing latrines in the Middle Ages was both colourful and broad. It included the words gong or gang (from the Anglo-Saxon meaning ‘the place to go’), privy and jake (a French form of ‘john’ or ‘johnny’).

Top tip: Ask your master mason to plan comfortable and private en-suite facilities off the principal bed chamber, following the example of Henry II at Dover Castle.

9) Decorate as required A castle doesn’t just have to be well defended – its high-status residents demand a certain swankiness too

Castles needed to be defensible in times of war but they also served as luxurious homes: the medieval nobility expected their accommodation to be both comfortable and well appointed. Throughout the Middle Ages these individuals travelled continuously with their attendant households, taking possessions and furniture with them from residence to residence. Important domestic interiors, however, commonly possessed permanent decorative fixtures such as stained-glass.

The decorative tastes of Henry III are recorded in particular and beguiling detail. In 1235–36, for example, he directed that his hall in Winchester Castle, Hampshire be painted with a map of the world and a ‘wheel of fortune’. This decoration has since been lost but the majestic interior does preserve the reputed round table of King Arthur – probably created between 1250 and 1280.

Castles were luxurious homes as well as strongholds. This is the 13th-century great hall at Winchester hung with the reputed round table of King Arthur. © Alamy

The wider setting of castles was also important for grand living. Parks were laid out for the jealously guarded aristocratic privilege of hunting, and there was a demand for gardens, too. The surviving building accounts for Kirby Muxloe Castle, Leicestershire reveal that its patron, Lord Hastings, began laying out the gardens at the very start of the building operations in 1480.

In the Middle Ages there was also a taste for rooms with fine views. One 13th-century group of rooms in castles that include Leeds in Kent, Corfe in Dorset and Chepstow, Monmouthshire, were named ‘gloriette’ after their splendour.

Top tip: Make sure the castle interior is splendid enough to attract visitors and friends. Entertainment can win battles without the danger of fighting.

John Goodall is an award-winning author, and architectural editor of the weekly magazine Country Life.

Published on March 03, 2016 03:30

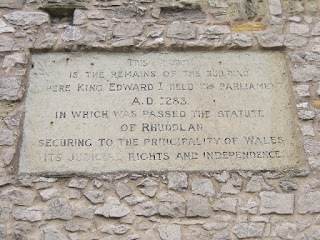

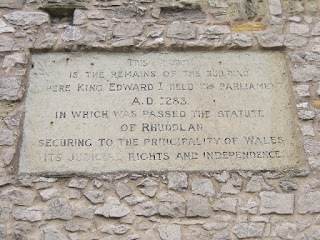

History Trivia - Statute of Rhuddlan incorporated

March 3

1284 The Statute of Rhuddlan (Statute of Wales) incorporated the Principality of Wales into England and provided the constitutional basis for the government of the Principality of North Wales from 1284 until 1536.

1284 The Statute of Rhuddlan (Statute of Wales) incorporated the Principality of Wales into England and provided the constitutional basis for the government of the Principality of North Wales from 1284 until 1536.

1284 The Statute of Rhuddlan (Statute of Wales) incorporated the Principality of Wales into England and provided the constitutional basis for the government of the Principality of North Wales from 1284 until 1536.

1284 The Statute of Rhuddlan (Statute of Wales) incorporated the Principality of Wales into England and provided the constitutional basis for the government of the Principality of North Wales from 1284 until 1536.

Published on March 03, 2016 02:30

March 2, 2016

Enigmatic Engraved Pendant from Stone Age Site is the Oldest in Britain

Ancient Origins

The oldest known engraved pendant in Britain, a small piece of shale dating back about 11,000 years, has been discovered at a Stone Age site in Yorkshire, England.

Archaeologists found the pendant at the Mesolithic site of Star Carr in 2015. The team of researchers wrote in an article in Internet Archaeology:

“Engraved motifs on Mesolithic pendants are extremely rare, with the exception of amber pendants from southern Scandinavia. The artwork on the pendant is the earliest known Mesolithic art in Britain; the 'barbed line' motif is comparable to styles on the Continent, particularly in Denmark. When it was first uncovered the lines were barely visible but using a range of digital imaging techniques it has been possible to examine them in detail and determine the style of engraving as well as the order in which the lines might have been made.”The team, led by archaeologist Nicky Milner of the University of York, wrote that they used microwear and residue analysis to determine whether the pendant was strung and worn. They also wanted to know if the lines had been made easier to see by painting it, as was the case for some amber pendants found in Denmark.

The paper says the combination of scientific and analytical techniques had not been used before and may be a model for analyzing artifacts in the future. In addition to three archaeologists, the team had a physicist and an anatomist.

A composite image of the phasing of the engravings. (

Milner et al./ Internet Archaeology

)The researchers said that despite the sophistication of their analysis, they can only speculate about what the engravings meant to the people who made them.

A composite image of the phasing of the engravings. (

Milner et al./ Internet Archaeology

)The researchers said that despite the sophistication of their analysis, they can only speculate about what the engravings meant to the people who made them.Ancient Last Supper charm is earliest known use of magic in Christianity12,300-Year-Old Bone Pendants May be Oldest Artwork Ever Discovered in AlaskaDiscovery of Hammer of Thor artifact solved mystery of Viking amuletsPreviously at the site of Star Carr, researchers found a piece of perforated amber, shale beads, bird bones, and two perforated animal teeth. But this is the first piece found there with an engraved design. And though there have been finds of other engraved pendants in bone, antler, and wood from the Mesolithic in Europe, none found so far have been made of shale.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]Shale beads from Star Carr with the ‘celtiform bead’ at the top. ( Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge )An engraved pendant from this era had never before been found in Britain, the paper says:

“The area where the pendant was discovered is where [archaeologist Grahame] Clark found a large quantity of bone, antler and wood, including rare artefacts such as 21 headdresses made from red deer skulls and 191 antler barbed points; the pendant appears to be from the same detrital muds and is therefore broadly associated with these other finds.”The pendant was found in the mud of a lake that dried out thousands of years ago. The sediments in which it was found have a high content of organic material and formed about 9,000 BC, scientific dating shows.

The pendant was lost or placed in shallow water, about a half-meter (1.6 feet) deep, about 10 meters (33 feet) from the shore of the lake. Analysis showed that reeds, sedges, and aquatic plants were growing where the pendant was deposited.

Location map of Star Carr. (

Milner et al./ Internet Archaeology

)The website Current Archaeology, in an article about Star Carr, asks what one could learn from the site, first excavated by Grahame Clark in from 1949 to 1951, and responds: “The answer is a new understanding that overturns much of what we have been taught about the lives of early settlers in northern Europe.” Chris Catling writes:

Location map of Star Carr. (

Milner et al./ Internet Archaeology

)The website Current Archaeology, in an article about Star Carr, asks what one could learn from the site, first excavated by Grahame Clark in from 1949 to 1951, and responds: “The answer is a new understanding that overturns much of what we have been taught about the lives of early settlers in northern Europe.” Chris Catling writes:“But everyone knows that Mesolithic people were highly mobile, moving about the landscape in small bands of two or three families. Talk of houses, settlements and putting down roots is anachronistic: that did not happen for another 5,000 years or so, when people began to farm the landscape rather than hunt and forage for wild food.”5,500-Year-Old Neolithic Cranial Amulets Shed Light on Ancient Belief SystemNew Study Analyzes a Mesolithic Cemetery Full of Children and an Odd Standing BurialArchaeologists find evidence of devastating ancient earthquake in mountaintop city of HipposThe members of the Vale of Pickering Research Trust, including Dr. Milner, returned to Star Carr and theorized a different story. They found evidence of a site 80 times larger than other sites of the period. “They also found the earliest known house in Britain with signs of long-lasting or repeated occupation, along with a series of timber platforms spreading along the lake edge,” writes Current Archaeology. “Not all Mesolithic people were wanderers, always moving on to a new source of food; some pioneer groups invested significant amounts of time and labour in building long-lasting structures in favoured landscape settings, like Star Carr.”

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]Excavations at the Star Carr site. ( Star Carr Archaeology Project )As for the pendant, they determined it had not been painted and may have been worn very little, on a special occasion, because use-wear analysis was unable to determine whether it had ever been strung. They wrote:

“On contextualising the art on the Star Carr pendant within the broader evidence for art in Mesolithic Britain and Denmark, the latter producing the largest collection of Mesolithic art in Europe, we discovered that both the engraving—in particular the distinctive barbed lines of Clark's type C—and the choice of pendant form are closely aligned with what is known from southern Scandinavia. However, it is important to acknowledge that despite the broad spectrum of scientific analyses applied to this object, revealing new and unprecedented insights into its making, some artefacts will remain enigmatic; we can only speculate as to what the art represents, and what the production and possibly wearing and display of this object meant to the people living along this lake edge during the ninth millennium BC.”

An image of the pendant using specular enhancement. (

Milner et al./ Internet Archaeology

)Featured Image: An artist’s reconstruction of life at Star Carr, where recent excavations have uncovered evidence of a thriving Mesolithic settlement. (

Current Archaeology

) Insert: Photo showing details such as small incisions and wear marks on the pendant. (

Milner et al./ Internet Archaeology

)

An image of the pendant using specular enhancement. (

Milner et al./ Internet Archaeology

)Featured Image: An artist’s reconstruction of life at Star Carr, where recent excavations have uncovered evidence of a thriving Mesolithic settlement. (

Current Archaeology

) Insert: Photo showing details such as small incisions and wear marks on the pendant. (

Milner et al./ Internet Archaeology

)By Mark Miller

Published on March 02, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Battle at Marton - Danish vikings defeated

Published on March 02, 2016 02:30

March 1, 2016

Excavations Reveal that the Oldest Roman Tavern Nourished and Served Ancient Life

Ancient Origins

A recent archaeological find in Lattes, France may provide insight into how the Romans dined 2,100 years ago. Archaeologists have discovered a structure that they believe to be a tavern, in an area that had been conquered by the Romans during that time. Lattes lies on the southern-border of France, on the Mediterranean Sea. The discovery of the tavern is an interesting one, in that this is the earliest Roman restaurant discovered to date.

A recent archaeological find in Lattes, France may provide insight into how the Romans dined 2,100 years ago. Archaeologists have discovered a structure that they believe to be a tavern, in an area that had been conquered by the Romans during that time. Lattes lies on the southern-border of France, on the Mediterranean Sea. The discovery of the tavern is an interesting one, in that this is the earliest Roman restaurant discovered to date.

Initially believed to be a bakery, USA Today reports that archaeologists now think that what they have uncovered is an ancient tavern. The archaeological findings include three indoor gristmills, and three ovens, which would have been used to bake flatbread. These findings go beyond what an individual home would require, and suggest that the site once hosted a tavern where the Romans could dine out.

The kitchen of what looks like an ancient tavern, with three reddish circles where the three ovens -- for baking flatbread and other dishes -- once stood. (

Lattes Excavations

)Benches and a charcoal-burning hearth, as well as pieces of large bowls and platters, indicate that this was no takeout counter. This was an establishment where the locals could sit and share a meal. The findings also provide some insight into the foods that would have been featured on the menu, as bones from fish, sheep, and cattle were discovered.

The kitchen of what looks like an ancient tavern, with three reddish circles where the three ovens -- for baking flatbread and other dishes -- once stood. (

Lattes Excavations

)Benches and a charcoal-burning hearth, as well as pieces of large bowls and platters, indicate that this was no takeout counter. This was an establishment where the locals could sit and share a meal. The findings also provide some insight into the foods that would have been featured on the menu, as bones from fish, sheep, and cattle were discovered.

According to archaeologist Benjamin Luley of Gettysburg College, the most common ceramic object found at the site was cups for drinking. The archaeologists have not uncovered any coins, which leads some to believe that the tavern may have served as a private dining room. However, Luley argued that during that time people tended not to lose coins, so the absence of coins doesn’t necessarily mean that the diners were not paying for their meals.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

The dining room of the ancient tavern, showing banks of pebbles where built-in benches once stood against the walls. ( Lattes excavations )This discovery casts light on the historic background of restaurants. Restaurants are something we take for granted today, and most of us know that whenever we are in the mood for a certain type of food, we can find a restaurant that will prepare and serve that meal, and where we can dine among family, friends, and others. During ancient times, it seems as though eating and drinking would have occurred primarily in the home.

Revolving dining room in Emperor Nero’s luxurious palace really existedGiraffe and Sea Urchin on the Menu for People of PompeiiAccording to foodtimeline.org, the first cafes, selling drinks and snacks, were established in 1550 AD in Constantinople. These weren’t the equivalent to today’s drive-through restaurants, where you can grab a quick cup of coffee or a snack, or even a sit-down restaurant where you eat a quick and casual dinner with friends and family. Rather, these were places for the well-educated members of society to share ideas and discoveries.

As far as full-fledged restaurants go, foodtimeline.org provides three theories as to who started the first restaurant – Boulanger (1765), Mathurin Roze de Chantoiseau in Paris (1766), and Beauvilliers (1782). It is not surprising to hear that France was the “birthplace of what we now call a restaurant.”

A Pompeiian taberna for eating and drinking. The faded painting over the counter pictured eggs, olives, fruit and radishes. (

Mac9/ CC BY 2.0

)Luley and Gaël Piquès of Montpellier University co-authored the study on the Lattes site, highlighting the importance of this find. “Not only is the tavern the earliest of its kind in the region, it also serves as an invaluable indicator of the changing social and economic infrastructure of the settlement and its inhabitants following the Roman conquest of Mediterranean Gaul in the late second century B.C.”

A Pompeiian taberna for eating and drinking. The faded painting over the counter pictured eggs, olives, fruit and radishes. (

Mac9/ CC BY 2.0

)Luley and Gaël Piquès of Montpellier University co-authored the study on the Lattes site, highlighting the importance of this find. “Not only is the tavern the earliest of its kind in the region, it also serves as an invaluable indicator of the changing social and economic infrastructure of the settlement and its inhabitants following the Roman conquest of Mediterranean Gaul in the late second century B.C.”

In speaking with USA Today, Luley opined as to the reason the tavern was built. Prior to the Romans’ arrival, the ancient town, called Lattara, was made up of farmers. The arrival of the Romans created a more diverse economy, and the need for places to eat outside the home.

Marcus Gavius Apicius: Top Gourmand of the Roman WorldThe Dark Underworld of the Paris Catacombs“If you’re not growing your own food, where are you going to eat? The Romans, in a very practical Roman way, had a very practical solution … a tavern.” Luley told USA Today. It has even been suggested that the tavern may have functioned more like a modern-day bar, with drinking vessels for serving wine.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

A Gallo-Roman relief depicting a river boat transporting wine barrels, an invention of the Gauls that came into widespread use during the 2nd century. Above, wine is stored in the traditional amphorae, some covered in wicker. ( JPS68/ CC BY SA 3.0 )This finding creates a commonality between two completely different time periods – ancient Roman times, and today. While the tavern discovered at Lattes was likely very different from modern restaurants, it was likely very similar as well, in that it was a place for people to meet while eating and drinking. Today’s social gatherings almost always include some form of food or drink, and the discovery of this tavern unearths the possibility that even in ancient times, people came together over food.

Featured Image: Site of the 2,100-year old Roman tavern, featuring the pits of taboon ovens for bread, a huge dining section to the right, a drainage system and millstones. Source: Lattes Excavation

By MRReese

A recent archaeological find in Lattes, France may provide insight into how the Romans dined 2,100 years ago. Archaeologists have discovered a structure that they believe to be a tavern, in an area that had been conquered by the Romans during that time. Lattes lies on the southern-border of France, on the Mediterranean Sea. The discovery of the tavern is an interesting one, in that this is the earliest Roman restaurant discovered to date.

A recent archaeological find in Lattes, France may provide insight into how the Romans dined 2,100 years ago. Archaeologists have discovered a structure that they believe to be a tavern, in an area that had been conquered by the Romans during that time. Lattes lies on the southern-border of France, on the Mediterranean Sea. The discovery of the tavern is an interesting one, in that this is the earliest Roman restaurant discovered to date.Initially believed to be a bakery, USA Today reports that archaeologists now think that what they have uncovered is an ancient tavern. The archaeological findings include three indoor gristmills, and three ovens, which would have been used to bake flatbread. These findings go beyond what an individual home would require, and suggest that the site once hosted a tavern where the Romans could dine out.

The kitchen of what looks like an ancient tavern, with three reddish circles where the three ovens -- for baking flatbread and other dishes -- once stood. (

Lattes Excavations

)Benches and a charcoal-burning hearth, as well as pieces of large bowls and platters, indicate that this was no takeout counter. This was an establishment where the locals could sit and share a meal. The findings also provide some insight into the foods that would have been featured on the menu, as bones from fish, sheep, and cattle were discovered.

The kitchen of what looks like an ancient tavern, with three reddish circles where the three ovens -- for baking flatbread and other dishes -- once stood. (

Lattes Excavations

)Benches and a charcoal-burning hearth, as well as pieces of large bowls and platters, indicate that this was no takeout counter. This was an establishment where the locals could sit and share a meal. The findings also provide some insight into the foods that would have been featured on the menu, as bones from fish, sheep, and cattle were discovered.According to archaeologist Benjamin Luley of Gettysburg College, the most common ceramic object found at the site was cups for drinking. The archaeologists have not uncovered any coins, which leads some to believe that the tavern may have served as a private dining room. However, Luley argued that during that time people tended not to lose coins, so the absence of coins doesn’t necessarily mean that the diners were not paying for their meals.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]The dining room of the ancient tavern, showing banks of pebbles where built-in benches once stood against the walls. ( Lattes excavations )This discovery casts light on the historic background of restaurants. Restaurants are something we take for granted today, and most of us know that whenever we are in the mood for a certain type of food, we can find a restaurant that will prepare and serve that meal, and where we can dine among family, friends, and others. During ancient times, it seems as though eating and drinking would have occurred primarily in the home.

Revolving dining room in Emperor Nero’s luxurious palace really existedGiraffe and Sea Urchin on the Menu for People of PompeiiAccording to foodtimeline.org, the first cafes, selling drinks and snacks, were established in 1550 AD in Constantinople. These weren’t the equivalent to today’s drive-through restaurants, where you can grab a quick cup of coffee or a snack, or even a sit-down restaurant where you eat a quick and casual dinner with friends and family. Rather, these were places for the well-educated members of society to share ideas and discoveries.

As far as full-fledged restaurants go, foodtimeline.org provides three theories as to who started the first restaurant – Boulanger (1765), Mathurin Roze de Chantoiseau in Paris (1766), and Beauvilliers (1782). It is not surprising to hear that France was the “birthplace of what we now call a restaurant.”

A Pompeiian taberna for eating and drinking. The faded painting over the counter pictured eggs, olives, fruit and radishes. (

Mac9/ CC BY 2.0

)Luley and Gaël Piquès of Montpellier University co-authored the study on the Lattes site, highlighting the importance of this find. “Not only is the tavern the earliest of its kind in the region, it also serves as an invaluable indicator of the changing social and economic infrastructure of the settlement and its inhabitants following the Roman conquest of Mediterranean Gaul in the late second century B.C.”

A Pompeiian taberna for eating and drinking. The faded painting over the counter pictured eggs, olives, fruit and radishes. (

Mac9/ CC BY 2.0

)Luley and Gaël Piquès of Montpellier University co-authored the study on the Lattes site, highlighting the importance of this find. “Not only is the tavern the earliest of its kind in the region, it also serves as an invaluable indicator of the changing social and economic infrastructure of the settlement and its inhabitants following the Roman conquest of Mediterranean Gaul in the late second century B.C.” In speaking with USA Today, Luley opined as to the reason the tavern was built. Prior to the Romans’ arrival, the ancient town, called Lattara, was made up of farmers. The arrival of the Romans created a more diverse economy, and the need for places to eat outside the home.

Marcus Gavius Apicius: Top Gourmand of the Roman WorldThe Dark Underworld of the Paris Catacombs“If you’re not growing your own food, where are you going to eat? The Romans, in a very practical Roman way, had a very practical solution … a tavern.” Luley told USA Today. It has even been suggested that the tavern may have functioned more like a modern-day bar, with drinking vessels for serving wine.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]A Gallo-Roman relief depicting a river boat transporting wine barrels, an invention of the Gauls that came into widespread use during the 2nd century. Above, wine is stored in the traditional amphorae, some covered in wicker. ( JPS68/ CC BY SA 3.0 )This finding creates a commonality between two completely different time periods – ancient Roman times, and today. While the tavern discovered at Lattes was likely very different from modern restaurants, it was likely very similar as well, in that it was a place for people to meet while eating and drinking. Today’s social gatherings almost always include some form of food or drink, and the discovery of this tavern unearths the possibility that even in ancient times, people came together over food.

Featured Image: Site of the 2,100-year old Roman tavern, featuring the pits of taboon ovens for bread, a huge dining section to the right, a drainage system and millstones. Source: Lattes Excavation

By MRReese

Published on March 01, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Romulus defeats Caeninenses

March 1

752 BC Romulus, first king of Rome, celebrated the first Roman triumph after his victory over the Caeninenses, following the Rape of the Sabine Women.

752 BC Romulus, first king of Rome, celebrated the first Roman triumph after his victory over the Caeninenses, following the Rape of the Sabine Women.

Published on March 01, 2016 02:30

February 29, 2016

New Investigations Begin on the Pyramid of the Mysterious Queen Khennuwa

Ancient Origins

After almost a century, archaeologists are re-entering the burial chambers of the mysterious Queen Khennuwa, who remains a mysterious personality of the Kingdom of Meroe.

After almost a century, archaeologists are re-entering the burial chambers of the mysterious Queen Khennuwa, who remains a mysterious personality of the Kingdom of Meroe.The archaeologists re-opened the tomb to increase documentation and research on the queen and site. According to Heritage Daily, the burial chambers were completely decorated with executed paintings and hieroglyphic texts, many of which are still in a good state of preservation. It was identified as the tomb of Queen Khennuwa due to the inscriptions in hieroglyphic texts.

The pyramid of Queen Khennuwa was excavated in 1922 during the excavations in ancient Nubia by George A. Reisner of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. However, the documentation created by his team wasn't complete, it contained only a few photographs and a few hand copies of inscriptions. This lack of information about the burial led archaeologists from the Qatari Mission for the Pyramids of Sudan (QMPS) to ask for permission to re-open the tomb.

The Southern Cemetery of Meroe, where Queen Khennuwa’s tomb is located. (

TrackHD

/CC BY 3.0

)The work in the pyramid was initiated by QMPS with the support of the Sudanese National Cooperation of Antiquities and Museums and the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin. The work consists of conservation and security measures at the site. These acts are planned to enable the burial of Queen Khennuwa to be open for tourists. Additionally, the team of researchers will analyze the paintings, the general condition of the tomb, and investigate the history of the tomb with the use of the newest technologies.

The Southern Cemetery of Meroe, where Queen Khennuwa’s tomb is located. (

TrackHD

/CC BY 3.0

)The work in the pyramid was initiated by QMPS with the support of the Sudanese National Cooperation of Antiquities and Museums and the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin. The work consists of conservation and security measures at the site. These acts are planned to enable the burial of Queen Khennuwa to be open for tourists. Additionally, the team of researchers will analyze the paintings, the general condition of the tomb, and investigate the history of the tomb with the use of the newest technologies.Pyramids of Meroë stand as Last Remnants of a Powerful CivilizationThe Mystery of the Miniature Pyramids of SudanDating the TombThe re-opening of the tomb was possible as a part of the research and the conservation program of the Qatari Mission for the Pyramids of Sudan. The program was created to restore and preserve the 53 Nubian pyramids at the al Begrawiya area, Nahar al Nil State, north of the National Capital Khartoum. The current investigation covers more than 100 pyramids in the royal cemeteries at Meroe. The international team of experts are working to preserve the heritage of the Egyptian “Black Pharaohs” of the 25th Dynasty (7th century BC), and their ancestors who ruled the Kingdom of Kush (currently located in Sudan) for four centuries.

The tomb of Queen Khennuwa is located 6 meters (19.7 feet) below the pyramid, which is typical for pyramids belonging to the Kingdom of Kush (Meroe). The pyramid has been dated to the early 4th century BC. However, according to research on the life of Queen Khennuwa, she lived in the 3rd century BC, suggesting that the chamber could have been previously prepared for someone else. According to Dows Dunham, her reign can be dated in the middle of the 3d century BC and her consort was perhaps Amanislo, a king of Kush.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]Subterranean burial chambers of Queen Khennuwa at Meroe. ( P. Wolf/DAI )The style of decoration in the tomb is very similar to the one used during the reign of the Egyptian 25th dynasty. Kings and queens of the Kingdom of Kush often used similar decorations to their great ancestors. The inscriptions discovered in the burial chambers also contain very similar texts to the funerary texts of the 25th Dynasty, further proving the strong influence of earlier Nubian traditions.

The Forgotten Queen and King of KushQueen Khennuwa is known only by her pyramid. In the decorated burial chamber, Queen Khennuwa is titled as the Royal Wife. There is also very little information about Amanislo. He was buried in another pyramid known as Beg. S5. He was most probably the successor of King Arakamani and predecessor of Amantekha.

Nubia and the Powerful Kingdom of KushArchaeologists Find Hieroglyphics That Shed New Light on the Golden Age of the Meroitic CivilizationAccording to the Historical Dictionary of Ancient Medieval Nubia, Amanislo is believed to be responsible for removing a pair of red granite couchant lion statues from Sulb to Napata. They were installed in Sulb by Amenhotep III (18th dynasty, Egypt), and perhaps reused by Tutankhamun. When they were transported to Napata, Amanislo decided to inscribe them with his name. Currently the lions are part of the collection of the British Museum in London.

The Great Pyramids of MeroeThe kingdom of Amanislo and Khennuwa was located about 200 km (124.3 miles) north of present-day Khartoum, Sudan. The pyramids at Meroe are not as tall as the pyramids in Giza, Egypt. They were discovered in the 1880s by the Italian explorer Giussepe Ferlini. Unfortunately, he destroyed the tops of many of the structures, looking for treasures within.

Aerial view of pyramids at Meroe in 2001. (

B N Chagny/CC BY SA 1.0

)Different than the ones found in Egypt, the pyramids of Meroe were built close to each other, so there are many pyramids in a one small section. The royal pyramid necropolis site of Meroe is officially a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Aerial view of pyramids at Meroe in 2001. (

B N Chagny/CC BY SA 1.0

)Different than the ones found in Egypt, the pyramids of Meroe were built close to each other, so there are many pyramids in a one small section. The royal pyramid necropolis site of Meroe is officially a UNESCO World Heritage site.Featured Image: Pyramid of Queen Khennuwa at the royal necropolis at Meroe. Source: P. Wolf/DAI

By Natalia Klimczak

Published on February 29, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Leap Day 2016

February 29

A Leap Day, February 29, is added to the calendar in Leap Years. This extra (intercalary) day makes the year 366 days long – and not 365 days, like a common (normal) year. Leap Years occur nearly every 4 years in our modern Gregorian Calendar.

Leap Day as a concept has existed for more than 2000 years, and is still associated with age-old traditions, folklore and superstition. One of the most popular traditions is that women propose to their boyfriends.

Read more

A Leap Day, February 29, is added to the calendar in Leap Years. This extra (intercalary) day makes the year 366 days long – and not 365 days, like a common (normal) year. Leap Years occur nearly every 4 years in our modern Gregorian Calendar.

Leap Day as a concept has existed for more than 2000 years, and is still associated with age-old traditions, folklore and superstition. One of the most popular traditions is that women propose to their boyfriends.

Read more

Published on February 29, 2016 01:30