MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 114

March 10, 2016

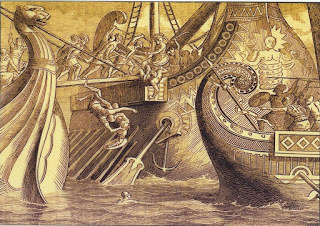

History Trivia - Battle of Aegus - Roman victory

March 10

241 BC A crushing Roman naval victory over the Carthaginians in the Battle of Aegus ended the First Punic War.

241 BC A crushing Roman naval victory over the Carthaginians in the Battle of Aegus ended the First Punic War.

Published on March 10, 2016 02:00

March 9, 2016

7 memorable moments in the history of Buckingham Palace

History Extra

Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh wave from the famous balcony at Buckingham Palace after the Queen's coronation on 2 June 1953. (Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh wave from the famous balcony at Buckingham Palace after the Queen's coronation on 2 June 1953. (Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

1703: Building begins at Buckingham Palace

The palace was originally built in 1703 as Buckingham House, a London home for the 3rd Earl of Mulgrave, John Sheffield. It became a royal residence when King George III purchased it in 1761 as a comfortable family home for his wife, Queen Charlotte. Fourteen of George and Charlotte’s 15 children were born there.

Buckingham House underwent a palatial transformation in the 1820s, when King George IV employed architect John Nash to give it a royal renovation. Queen Victoria was the first monarch to adopt Buckingham Palace as her official residence, moving there in 1837, within a year of becoming queen. She oversaw the last major construction work at the palace, adding the front wing in the 1840s to give her large family extra space. In 1883 electricity was installed in the ballroom, the largest room in the palace. Over the following four years electricity was installed throughout the palace, which now uses more than 40,000 lightbulbs.

Buckingham House, 1746. Built in 1703, the house forms the architectural core of the present-day Buckingham Palace. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) 1851: Queen Victoria makes the first public appearance on the balconyThe Buckingham Palace balcony is now iconic, having hosted several notable royal appearances over the years. Queen Victoria made the first recorded royal appearance on the balcony in 1851, when she greeted the public during celebrations for the opening of the Great Exhibition, a groundbreaking showcase of international manufacturing, masterminded by Prince Albert. Appearances on the balcony are now a popular part of royal events. In 2002 Queen Elizabeth waved to crowds from the balcony as more than a million people flocked to Buckingham Palace to celebrate her Golden Jubilee. More than 200 million viewers around the world watched the evening’s ‘Party at the Palace’ concert on television. At their wedding in 2011, Prince William and Kate Middleton also appeared on the famous balcony. The newlyweds shared a kiss, much to the delight of the crowds.

Catherine Middleton and Prince William kiss on the balcony at Buckingham Palace following their wedding at Westminster Abbey on 29 April 2011. (Mark Cuthbert/UK Press via Getty Images) 1841 and 1910: Edward VII is born and dies at Buckingham PalaceEdward VII is the only monarch to have been born and died at Buckingham Palace. Following the wedding of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert on 10 February 1840, their second child [and eldest son], Edward was born at the palace on 9 November 1841. Known to his family as ‘Bertie’, Edward spent much of his childhood at the palace with his eight siblings. In 1902 Edward underwent major surgery at Buckingham Palace. Close to death from appendicitis, he was successfully operated on in a room overlooking the garden. Later that year [following his recovery] he was crowned at Westminster Abbey after nearly 60 years as heir to the throne. After years of excessive cigar and cigarette consumption, in 1910 Edward contracted a severe case of bronchitis. He died at Buckingham Palace on 6 May 1910 following a series of heart attacks, and was succeeded by his son George V. Following a royal birth or death, a notice was attached to the railings of Buckingham Palace to alert members of the public. Even today, this traditional custom is upheld.

King Edward VII, who was born and died at Buckingham Palace. (Ernest H. Mills/Getty Images) 1914: Suffragettes march on the palaceOn 22 May 1914, Buckingham Palace found itself in the middle of the fight for women’s voting rights, as 20,000 suffragettes marched on the palace. Led by Emmeline Pankhurst, the women began processing towards the palace from Grosvenor Gardens, declaring their intention to deliver a petition to the king. The protest attracted sensationalist and unsympathetic press coverage. The Daily Mirror carried the headline “Mrs Pankhurst arrested at the gates of Buckingham Palace in trying to present a petition to the King”, surrounded by photographs of clashes between the protestors and police. It described “distressing scenes” in which a “body of militant suffragettes” led by Pankhurst “endeavoured to carry out their impossible scheme”, evading police and making it to the gates of the palace. The Telegraph, meanwhile, described a “serious fracas between the wild women and the police, in which the militants delivered a brief but furious attack on the constables”. When she reached the palace gates, Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested. The Telegraph suggested she “was able to offer little or no resistance, but shouting out that she had got to the palace gates, she was carried bodily by a chief inspector to a private motor which the police had in waiting”. Following her arrest, Pankhurst was taken to Holloway Prison.

Suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst is arrested outside Buckingham Palace in May 1914. (Jimmy Sime/Getty Images) 1937: The Buckingham Palace Guide Company is formedIn 1937, the 11-year-old Princess Elizabeth [now Queen Elizabeth II] enrolled to be a Girl Guide. Her younger sister Princess Margaret, who was seven years old, also signed up as a Brownie. The Girl Guide Association had been formed in 1910 by Agnes Baden Powell, as an alternative girl’s organisation to scouting. As it was believed that the princesses should live as normal lives as possible, they were enrolled to join the popular organisation by their aunt, Princess Mary. The 1st Buckingham Palace Company was then formed, which included some 20 Guides and 14 Brownies, made up of children of royal household members and Buckingham Palace employees. A summerhouse in the palace garden became the Guides’ headquarters, with the princesses reportedly cooking on campfires, pitching tents and earning badges like any other Guides. Following the outbreak of the Second World War the summerhouse headquarters was closed down due to the bomb threat and moved to the more rural setting of Windsor Castle. In 1952 Queen Elizabeth and her mother became joint patrons of the Girl Guides.

Princess Elizabeth (now Queen Elizabeth II, right) and her younger sister Princess Margaret dressed as guides in 1943. They are watching the flight of a carrier pigeon they have just released, carrying a message to Chief Guide Lady Olave Baden-Powell. (Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) 1940s: The palace is bombed The royal family remained at Buckingham Palace throughout the Second World War, despite Foreign Office advice to leave Britain. Queen Elizabeth [later the Queen Mother] declared: “The children will not leave unless I do. I shall not leave unless their father does, and the king will not leave the country in any circumstances, whatever”. However, the decision to remain in Britain placed the royal family in significant danger – the palace received nine direct bomb hits during the course of the war and on 8 March 1941 PC Steve Robertson, a policeman on duty at the Palace, was killed by flying debris when a bomb hit. In a letter to her mother-in-law, Queen Mary, the queen recalled one particularly difficult night of bombing at the palace in 1940, when the palace chapel was destroyed. In it she recounts how she was “battling” to remove an eyelash from the king's eye when they heard the “unmistakable whirr-whirr of a German plane” and then the “scream of a bomb”. She recalled how “it all happened so quickly that we had only time to look foolishly at each other when the scream hurtled past us and exploded with a tremendous crash in the quadrangle”. Despite the palace bombings, the royal family remained defiant. “I am glad we have been bombed”, Queen Elizabeth declared in September 1940, “Now we can look the East End in the eye”. King George VI and Queen Elizabeth survey the damage after the bombing of Buckingham Palace during the Second World War. (Fox Photos/Getty Images) 1945: VE day celebrationsWhen peace was finally declared in Europe on 8 May 1945, Buckingham Palace became a focal point for VE Day celebrations. Winston Churchill appeared with the king, queen and the two royal princesses on the palace’s balcony before huge crowds. Throughout the course of the day the royal family made a total of eight appearances on the balcony to wave to those celebrating below. During their father’s final balcony appearance of the day the princesses Margaret and Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth II) secretly joined the cheering crowd below. Elizabeth later recalled: “We stood outside and shouted, ‘We want the king’… I think it was one of the most memorable nights of my life”. King George VI also delivered a radio address to his nation, played on loud speakers in Trafalgar Square. He praised Britons’ resilience and honoured those who had lost their lives. “Let us remember those who will not come back” he declared, “let us remember the men in all the services, and the women in all the services, who have laid down their lives. We have come to the end of our tribulation and they are not with us at the moment of our rejoicing”.

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth survey the damage after the bombing of Buckingham Palace during the Second World War. (Fox Photos/Getty Images) 1945: VE day celebrationsWhen peace was finally declared in Europe on 8 May 1945, Buckingham Palace became a focal point for VE Day celebrations. Winston Churchill appeared with the king, queen and the two royal princesses on the palace’s balcony before huge crowds. Throughout the course of the day the royal family made a total of eight appearances on the balcony to wave to those celebrating below. During their father’s final balcony appearance of the day the princesses Margaret and Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth II) secretly joined the cheering crowd below. Elizabeth later recalled: “We stood outside and shouted, ‘We want the king’… I think it was one of the most memorable nights of my life”. King George VI also delivered a radio address to his nation, played on loud speakers in Trafalgar Square. He praised Britons’ resilience and honoured those who had lost their lives. “Let us remember those who will not come back” he declared, “let us remember the men in all the services, and the women in all the services, who have laid down their lives. We have come to the end of our tribulation and they are not with us at the moment of our rejoicing”.

British prime minister Winston Churchill with the royal family, waving from the balcony of Buckingham Palace during VE Day celebrations. (Reg Speller/Getty Images)

Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh wave from the famous balcony at Buckingham Palace after the Queen's coronation on 2 June 1953. (Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh wave from the famous balcony at Buckingham Palace after the Queen's coronation on 2 June 1953. (Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)1703: Building begins at Buckingham Palace

The palace was originally built in 1703 as Buckingham House, a London home for the 3rd Earl of Mulgrave, John Sheffield. It became a royal residence when King George III purchased it in 1761 as a comfortable family home for his wife, Queen Charlotte. Fourteen of George and Charlotte’s 15 children were born there.

Buckingham House underwent a palatial transformation in the 1820s, when King George IV employed architect John Nash to give it a royal renovation. Queen Victoria was the first monarch to adopt Buckingham Palace as her official residence, moving there in 1837, within a year of becoming queen. She oversaw the last major construction work at the palace, adding the front wing in the 1840s to give her large family extra space. In 1883 electricity was installed in the ballroom, the largest room in the palace. Over the following four years electricity was installed throughout the palace, which now uses more than 40,000 lightbulbs.

Buckingham House, 1746. Built in 1703, the house forms the architectural core of the present-day Buckingham Palace. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images) 1851: Queen Victoria makes the first public appearance on the balconyThe Buckingham Palace balcony is now iconic, having hosted several notable royal appearances over the years. Queen Victoria made the first recorded royal appearance on the balcony in 1851, when she greeted the public during celebrations for the opening of the Great Exhibition, a groundbreaking showcase of international manufacturing, masterminded by Prince Albert. Appearances on the balcony are now a popular part of royal events. In 2002 Queen Elizabeth waved to crowds from the balcony as more than a million people flocked to Buckingham Palace to celebrate her Golden Jubilee. More than 200 million viewers around the world watched the evening’s ‘Party at the Palace’ concert on television. At their wedding in 2011, Prince William and Kate Middleton also appeared on the famous balcony. The newlyweds shared a kiss, much to the delight of the crowds.

Catherine Middleton and Prince William kiss on the balcony at Buckingham Palace following their wedding at Westminster Abbey on 29 April 2011. (Mark Cuthbert/UK Press via Getty Images) 1841 and 1910: Edward VII is born and dies at Buckingham PalaceEdward VII is the only monarch to have been born and died at Buckingham Palace. Following the wedding of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert on 10 February 1840, their second child [and eldest son], Edward was born at the palace on 9 November 1841. Known to his family as ‘Bertie’, Edward spent much of his childhood at the palace with his eight siblings. In 1902 Edward underwent major surgery at Buckingham Palace. Close to death from appendicitis, he was successfully operated on in a room overlooking the garden. Later that year [following his recovery] he was crowned at Westminster Abbey after nearly 60 years as heir to the throne. After years of excessive cigar and cigarette consumption, in 1910 Edward contracted a severe case of bronchitis. He died at Buckingham Palace on 6 May 1910 following a series of heart attacks, and was succeeded by his son George V. Following a royal birth or death, a notice was attached to the railings of Buckingham Palace to alert members of the public. Even today, this traditional custom is upheld.

King Edward VII, who was born and died at Buckingham Palace. (Ernest H. Mills/Getty Images) 1914: Suffragettes march on the palaceOn 22 May 1914, Buckingham Palace found itself in the middle of the fight for women’s voting rights, as 20,000 suffragettes marched on the palace. Led by Emmeline Pankhurst, the women began processing towards the palace from Grosvenor Gardens, declaring their intention to deliver a petition to the king. The protest attracted sensationalist and unsympathetic press coverage. The Daily Mirror carried the headline “Mrs Pankhurst arrested at the gates of Buckingham Palace in trying to present a petition to the King”, surrounded by photographs of clashes between the protestors and police. It described “distressing scenes” in which a “body of militant suffragettes” led by Pankhurst “endeavoured to carry out their impossible scheme”, evading police and making it to the gates of the palace. The Telegraph, meanwhile, described a “serious fracas between the wild women and the police, in which the militants delivered a brief but furious attack on the constables”. When she reached the palace gates, Emmeline Pankhurst was arrested. The Telegraph suggested she “was able to offer little or no resistance, but shouting out that she had got to the palace gates, she was carried bodily by a chief inspector to a private motor which the police had in waiting”. Following her arrest, Pankhurst was taken to Holloway Prison.

Suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst is arrested outside Buckingham Palace in May 1914. (Jimmy Sime/Getty Images) 1937: The Buckingham Palace Guide Company is formedIn 1937, the 11-year-old Princess Elizabeth [now Queen Elizabeth II] enrolled to be a Girl Guide. Her younger sister Princess Margaret, who was seven years old, also signed up as a Brownie. The Girl Guide Association had been formed in 1910 by Agnes Baden Powell, as an alternative girl’s organisation to scouting. As it was believed that the princesses should live as normal lives as possible, they were enrolled to join the popular organisation by their aunt, Princess Mary. The 1st Buckingham Palace Company was then formed, which included some 20 Guides and 14 Brownies, made up of children of royal household members and Buckingham Palace employees. A summerhouse in the palace garden became the Guides’ headquarters, with the princesses reportedly cooking on campfires, pitching tents and earning badges like any other Guides. Following the outbreak of the Second World War the summerhouse headquarters was closed down due to the bomb threat and moved to the more rural setting of Windsor Castle. In 1952 Queen Elizabeth and her mother became joint patrons of the Girl Guides.

Princess Elizabeth (now Queen Elizabeth II, right) and her younger sister Princess Margaret dressed as guides in 1943. They are watching the flight of a carrier pigeon they have just released, carrying a message to Chief Guide Lady Olave Baden-Powell. (Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) 1940s: The palace is bombed The royal family remained at Buckingham Palace throughout the Second World War, despite Foreign Office advice to leave Britain. Queen Elizabeth [later the Queen Mother] declared: “The children will not leave unless I do. I shall not leave unless their father does, and the king will not leave the country in any circumstances, whatever”. However, the decision to remain in Britain placed the royal family in significant danger – the palace received nine direct bomb hits during the course of the war and on 8 March 1941 PC Steve Robertson, a policeman on duty at the Palace, was killed by flying debris when a bomb hit. In a letter to her mother-in-law, Queen Mary, the queen recalled one particularly difficult night of bombing at the palace in 1940, when the palace chapel was destroyed. In it she recounts how she was “battling” to remove an eyelash from the king's eye when they heard the “unmistakable whirr-whirr of a German plane” and then the “scream of a bomb”. She recalled how “it all happened so quickly that we had only time to look foolishly at each other when the scream hurtled past us and exploded with a tremendous crash in the quadrangle”. Despite the palace bombings, the royal family remained defiant. “I am glad we have been bombed”, Queen Elizabeth declared in September 1940, “Now we can look the East End in the eye”.

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth survey the damage after the bombing of Buckingham Palace during the Second World War. (Fox Photos/Getty Images) 1945: VE day celebrationsWhen peace was finally declared in Europe on 8 May 1945, Buckingham Palace became a focal point for VE Day celebrations. Winston Churchill appeared with the king, queen and the two royal princesses on the palace’s balcony before huge crowds. Throughout the course of the day the royal family made a total of eight appearances on the balcony to wave to those celebrating below. During their father’s final balcony appearance of the day the princesses Margaret and Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth II) secretly joined the cheering crowd below. Elizabeth later recalled: “We stood outside and shouted, ‘We want the king’… I think it was one of the most memorable nights of my life”. King George VI also delivered a radio address to his nation, played on loud speakers in Trafalgar Square. He praised Britons’ resilience and honoured those who had lost their lives. “Let us remember those who will not come back” he declared, “let us remember the men in all the services, and the women in all the services, who have laid down their lives. We have come to the end of our tribulation and they are not with us at the moment of our rejoicing”.

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth survey the damage after the bombing of Buckingham Palace during the Second World War. (Fox Photos/Getty Images) 1945: VE day celebrationsWhen peace was finally declared in Europe on 8 May 1945, Buckingham Palace became a focal point for VE Day celebrations. Winston Churchill appeared with the king, queen and the two royal princesses on the palace’s balcony before huge crowds. Throughout the course of the day the royal family made a total of eight appearances on the balcony to wave to those celebrating below. During their father’s final balcony appearance of the day the princesses Margaret and Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth II) secretly joined the cheering crowd below. Elizabeth later recalled: “We stood outside and shouted, ‘We want the king’… I think it was one of the most memorable nights of my life”. King George VI also delivered a radio address to his nation, played on loud speakers in Trafalgar Square. He praised Britons’ resilience and honoured those who had lost their lives. “Let us remember those who will not come back” he declared, “let us remember the men in all the services, and the women in all the services, who have laid down their lives. We have come to the end of our tribulation and they are not with us at the moment of our rejoicing”.

British prime minister Winston Churchill with the royal family, waving from the balcony of Buckingham Palace during VE Day celebrations. (Reg Speller/Getty Images)

Published on March 09, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - David Riccio murdered

March 9

1566 David Riccio, secretary and advisor to Mary, Queen of Scots, was murdered in the Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, Scotland.

1566 David Riccio, secretary and advisor to Mary, Queen of Scots, was murdered in the Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Published on March 09, 2016 02:00

March 8, 2016

New Piece of a 2,200-Year-Old Roman Puzzle Emerges, Bringing Together Ancient Map of Rome

Ancient Origins

Maps are a useful modern tool, telling us how to get places, showing us where borders lie, and illustrating the distance between two places. While modern technology has made the creation of and access to maps something we don’t think twice about, the creation of maps during ancient times was far more complicated. Without the availability of GPS, air travel, and computers, ancient civilizations had to rely on other means for the difficult task of creating maps. One ancient map – the Forma Urbis Romae – has been a mystery for years, serving as a complex jigsaw as researchers continue to uncover various pieces of the puzzle, including a recently discovered fragment that has just been reunited with the other existing pieces.

Maps are a useful modern tool, telling us how to get places, showing us where borders lie, and illustrating the distance between two places. While modern technology has made the creation of and access to maps something we don’t think twice about, the creation of maps during ancient times was far more complicated. Without the availability of GPS, air travel, and computers, ancient civilizations had to rely on other means for the difficult task of creating maps. One ancient map – the Forma Urbis Romae – has been a mystery for years, serving as a complex jigsaw as researchers continue to uncover various pieces of the puzzle, including a recently discovered fragment that has just been reunited with the other existing pieces.

Pieces of the Forma Urbis Romae map. Researchers have spent years piecing together over a thousand fragments (Sebastia Gibralt / Flickr)Sometime between 203 and 211 AD a marble map of Rome was created. According to History of Information, the map was originally composed of 150 marble slabs, and it was 18.10 meters (60ft) high by 13 meters (43ft) wide. “Created at a scale of approximately 1 to 240, the map was detailed enough to show the floor plans of nearly every temple, bath, and insula in the central Roman city. The boundaries of the plan were decided based on the available space on the marble, instead of by geographical or political borders as modern maps usually are.”

Pieces of the Forma Urbis Romae map. Researchers have spent years piecing together over a thousand fragments (Sebastia Gibralt / Flickr)Sometime between 203 and 211 AD a marble map of Rome was created. According to History of Information, the map was originally composed of 150 marble slabs, and it was 18.10 meters (60ft) high by 13 meters (43ft) wide. “Created at a scale of approximately 1 to 240, the map was detailed enough to show the floor plans of nearly every temple, bath, and insula in the central Roman city. The boundaries of the plan were decided based on the available space on the marble, instead of by geographical or political borders as modern maps usually are.”

The map shows the topography of Rome as it existed at the time, including structures such as temples, houses, shops, warehouses, and apartment buildings. According to Discovery News, the map was created under the rule of Emperor Septimius Severus. Severus served as emperor from 193 to 211 and was a strong leader, known for converting the Roman government into a military monarchy.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

The Imperial Forum: the Forma Urbis Romae was detailed enough to show the floor plans of nearly every temple, bath, and insula in the central Roman city ( public domain )The Forma Urbis Romae map has only been recovered in relatively small pieces. The fragments that have been found are currently held at the Capitoline museum in Italy. Researchers have recovered only approximately ten percent of the map, in 1200 pieces. They have been attempting to piece it together for hundreds of years, since the first pieces were found in 1562. According to History of Information, a team of researchers from Stanford University, led by Marc Levoy, began using digital technology in an effort to solve the puzzle. Of the 1200 pieces collected, only about 200 have been identified. The map was originally constructed on a wall within the Templum Pacis (Temple of Peace). The wall still remains, but the map was partially torn down hundreds of years ago, with the remaining pieces eventually fell, shattering into hundreds of pieces.

Some fragments of the Forma Urbis Romae in an engraving by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1756 (

public domain

)In 2014, a new piece of the map was discovered while workers were working at a Vatican-owned building called Palazzo Maffei Marescotti. It is believed that the pieces ended up in that location during construction of a 16th century palace, as building materials were being recycled. According to museum officials, “[t]he fragment relates to plate 31 of the map, which is the present-day area of the Ghetto, one of the monumental areas of the ancient city, dominated by the Circus Flaminius, built in 220 BC to host the Plebeian games, and where a number of important public monuments stood.” The new piece not only brought forth new information, but after recently being reunited with the rest of the pieces, it also allowed researchers to identify where three other existing pieces to the map belong. This affords researchers a new outlook on the map as a whole.

Some fragments of the Forma Urbis Romae in an engraving by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1756 (

public domain

)In 2014, a new piece of the map was discovered while workers were working at a Vatican-owned building called Palazzo Maffei Marescotti. It is believed that the pieces ended up in that location during construction of a 16th century palace, as building materials were being recycled. According to museum officials, “[t]he fragment relates to plate 31 of the map, which is the present-day area of the Ghetto, one of the monumental areas of the ancient city, dominated by the Circus Flaminius, built in 220 BC to host the Plebeian games, and where a number of important public monuments stood.” The new piece not only brought forth new information, but after recently being reunited with the rest of the pieces, it also allowed researchers to identify where three other existing pieces to the map belong. This affords researchers a new outlook on the map as a whole.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

The new piece of the Forma Urbis Romae puzzle. Credit: Sovrintendenza Capitolina Al Beni Culturali.The Forma Urbis Romae has been called a giant jigsaw puzzle. Unlike other puzzles, it did not come with a box showing the final product, or uniform pieces. In fact, it did not even come with all of the pieces, and researchers may never know where the remaining pieces are located. The discovery of the new piece allowed for more than just the placement of a single piece, but for a more holistic view of the map as a whole. As researchers continue to find pieces of the map they will better be able to piece together another impossible jigsaw puzzle – Roman history as a whole.

Featured image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis Romae map ( Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project ).

By M R Reese

Maps are a useful modern tool, telling us how to get places, showing us where borders lie, and illustrating the distance between two places. While modern technology has made the creation of and access to maps something we don’t think twice about, the creation of maps during ancient times was far more complicated. Without the availability of GPS, air travel, and computers, ancient civilizations had to rely on other means for the difficult task of creating maps. One ancient map – the Forma Urbis Romae – has been a mystery for years, serving as a complex jigsaw as researchers continue to uncover various pieces of the puzzle, including a recently discovered fragment that has just been reunited with the other existing pieces.

Maps are a useful modern tool, telling us how to get places, showing us where borders lie, and illustrating the distance between two places. While modern technology has made the creation of and access to maps something we don’t think twice about, the creation of maps during ancient times was far more complicated. Without the availability of GPS, air travel, and computers, ancient civilizations had to rely on other means for the difficult task of creating maps. One ancient map – the Forma Urbis Romae – has been a mystery for years, serving as a complex jigsaw as researchers continue to uncover various pieces of the puzzle, including a recently discovered fragment that has just been reunited with the other existing pieces. Pieces of the Forma Urbis Romae map. Researchers have spent years piecing together over a thousand fragments (Sebastia Gibralt / Flickr)Sometime between 203 and 211 AD a marble map of Rome was created. According to History of Information, the map was originally composed of 150 marble slabs, and it was 18.10 meters (60ft) high by 13 meters (43ft) wide. “Created at a scale of approximately 1 to 240, the map was detailed enough to show the floor plans of nearly every temple, bath, and insula in the central Roman city. The boundaries of the plan were decided based on the available space on the marble, instead of by geographical or political borders as modern maps usually are.”

Pieces of the Forma Urbis Romae map. Researchers have spent years piecing together over a thousand fragments (Sebastia Gibralt / Flickr)Sometime between 203 and 211 AD a marble map of Rome was created. According to History of Information, the map was originally composed of 150 marble slabs, and it was 18.10 meters (60ft) high by 13 meters (43ft) wide. “Created at a scale of approximately 1 to 240, the map was detailed enough to show the floor plans of nearly every temple, bath, and insula in the central Roman city. The boundaries of the plan were decided based on the available space on the marble, instead of by geographical or political borders as modern maps usually are.”The map shows the topography of Rome as it existed at the time, including structures such as temples, houses, shops, warehouses, and apartment buildings. According to Discovery News, the map was created under the rule of Emperor Septimius Severus. Severus served as emperor from 193 to 211 and was a strong leader, known for converting the Roman government into a military monarchy.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]The Imperial Forum: the Forma Urbis Romae was detailed enough to show the floor plans of nearly every temple, bath, and insula in the central Roman city ( public domain )The Forma Urbis Romae map has only been recovered in relatively small pieces. The fragments that have been found are currently held at the Capitoline museum in Italy. Researchers have recovered only approximately ten percent of the map, in 1200 pieces. They have been attempting to piece it together for hundreds of years, since the first pieces were found in 1562. According to History of Information, a team of researchers from Stanford University, led by Marc Levoy, began using digital technology in an effort to solve the puzzle. Of the 1200 pieces collected, only about 200 have been identified. The map was originally constructed on a wall within the Templum Pacis (Temple of Peace). The wall still remains, but the map was partially torn down hundreds of years ago, with the remaining pieces eventually fell, shattering into hundreds of pieces.

Some fragments of the Forma Urbis Romae in an engraving by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1756 (

public domain

)In 2014, a new piece of the map was discovered while workers were working at a Vatican-owned building called Palazzo Maffei Marescotti. It is believed that the pieces ended up in that location during construction of a 16th century palace, as building materials were being recycled. According to museum officials, “[t]he fragment relates to plate 31 of the map, which is the present-day area of the Ghetto, one of the monumental areas of the ancient city, dominated by the Circus Flaminius, built in 220 BC to host the Plebeian games, and where a number of important public monuments stood.” The new piece not only brought forth new information, but after recently being reunited with the rest of the pieces, it also allowed researchers to identify where three other existing pieces to the map belong. This affords researchers a new outlook on the map as a whole.

Some fragments of the Forma Urbis Romae in an engraving by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1756 (

public domain

)In 2014, a new piece of the map was discovered while workers were working at a Vatican-owned building called Palazzo Maffei Marescotti. It is believed that the pieces ended up in that location during construction of a 16th century palace, as building materials were being recycled. According to museum officials, “[t]he fragment relates to plate 31 of the map, which is the present-day area of the Ghetto, one of the monumental areas of the ancient city, dominated by the Circus Flaminius, built in 220 BC to host the Plebeian games, and where a number of important public monuments stood.” The new piece not only brought forth new information, but after recently being reunited with the rest of the pieces, it also allowed researchers to identify where three other existing pieces to the map belong. This affords researchers a new outlook on the map as a whole. [image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]The new piece of the Forma Urbis Romae puzzle. Credit: Sovrintendenza Capitolina Al Beni Culturali.The Forma Urbis Romae has been called a giant jigsaw puzzle. Unlike other puzzles, it did not come with a box showing the final product, or uniform pieces. In fact, it did not even come with all of the pieces, and researchers may never know where the remaining pieces are located. The discovery of the new piece allowed for more than just the placement of a single piece, but for a more holistic view of the map as a whole. As researchers continue to find pieces of the map they will better be able to piece together another impossible jigsaw puzzle – Roman history as a whole.

Featured image: A fragment of the Forma Urbis Romae map ( Stanford Digital Forma Urbis Romae Project ).

By M R Reese

Published on March 08, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Anne Stuart becomes Queen regnant of England, Scotland and Ireland

March 8

1702 Anne Stuart, sister of Mary II, became Queen regnant of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

1702 Anne Stuart, sister of Mary II, became Queen regnant of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Published on March 08, 2016 02:00

March 7, 2016

History Trivia - Henry VIII divorce is denied

March 7

1530 King Henry VIII's divorce request was denied by the Pope, which prompted Henry to declare himself as supreme head of England's church.

1530 King Henry VIII's divorce request was denied by the Pope, which prompted Henry to declare himself as supreme head of England's church.

Published on March 07, 2016 02:30

March 6, 2016

Anglo-Saxon Island Discovered in English Village

Discovery News

This glass counter decorated with twisted colorful strands was discovered at the site.

This glass counter decorated with twisted colorful strands was discovered at the site.

University of Sheffield

by Rossella Lorenzi

British archaeologists have unearthed the remains of a previously unknown Anglo-Saxon island, the University of Sheffield announced.

Hailed as one of the most important archaeological finds in the UK in decades, the island was located in the village of Little Carlton, near Louth, Lincolnshire.

Once home to a Middle Saxon settlement, the site was first discovered by Graham Vickers, a local metal detector hobbyist. While searching a plowed field, Vickers found a silver stylus, which is an ornate writing tool dating from the eighth century.

That was just the first of many intriguing items that were to emerge from the field.

‘Britain’s Pompeii’ Found at Bronze Age Settlement

After alerting England’s Portable Antiquities Scheme, Vickers returned to the site and unearthed hundreds of other artifacts, recording their location with a GPS system.

The items include another 20 styli, about 300 dress pins, a huge number of “sceattas” – coins from the 7th-8th centuries – and a small lead tablet bearing the female Anglo-Saxon name, Cudberg.

Later, a team from the University of Sheffield found bones of a butchered animal and Saxon pottery.

“This is a site of international importance,” Hugh Willmott, from the university’s department of archaeology, said in a statement.

Coolest Archaeological Discoveries of 2015

It is thought the settlement might have been an island monastery or a trading center, but archaeologists have just begun investigating it.

Using geophysical and magnetometry surveys along with 3D modelling, the researchers digitally restored the water level of the island to its higher medieval state.

“It is enclosed between a basin and a ditch,” Willmott told The Guardian.

Man With Metal Detector Finds Roman-Era Grave

“It was a focal point in the Lincolnshire area, connected to the outside world through water courses,” he added.

Students from the University have subsequently opened nine evaluation trenches at the site, exposing an area which seems to have been used for industrial working.

“It’s clearly a very high-status Saxon site … it’s clearly not your everyday find,” Willmott said.

This glass counter decorated with twisted colorful strands was discovered at the site.

This glass counter decorated with twisted colorful strands was discovered at the site.University of Sheffield

by Rossella Lorenzi

British archaeologists have unearthed the remains of a previously unknown Anglo-Saxon island, the University of Sheffield announced.

Hailed as one of the most important archaeological finds in the UK in decades, the island was located in the village of Little Carlton, near Louth, Lincolnshire.

Once home to a Middle Saxon settlement, the site was first discovered by Graham Vickers, a local metal detector hobbyist. While searching a plowed field, Vickers found a silver stylus, which is an ornate writing tool dating from the eighth century.

That was just the first of many intriguing items that were to emerge from the field.

‘Britain’s Pompeii’ Found at Bronze Age Settlement

After alerting England’s Portable Antiquities Scheme, Vickers returned to the site and unearthed hundreds of other artifacts, recording their location with a GPS system.

The items include another 20 styli, about 300 dress pins, a huge number of “sceattas” – coins from the 7th-8th centuries – and a small lead tablet bearing the female Anglo-Saxon name, Cudberg.

Later, a team from the University of Sheffield found bones of a butchered animal and Saxon pottery.

“This is a site of international importance,” Hugh Willmott, from the university’s department of archaeology, said in a statement.

Coolest Archaeological Discoveries of 2015

It is thought the settlement might have been an island monastery or a trading center, but archaeologists have just begun investigating it.

Using geophysical and magnetometry surveys along with 3D modelling, the researchers digitally restored the water level of the island to its higher medieval state.

“It is enclosed between a basin and a ditch,” Willmott told The Guardian.

Man With Metal Detector Finds Roman-Era Grave

“It was a focal point in the Lincolnshire area, connected to the outside world through water courses,” he added.

Students from the University have subsequently opened nine evaluation trenches at the site, exposing an area which seems to have been used for industrial working.

“It’s clearly a very high-status Saxon site … it’s clearly not your everyday find,” Willmott said.

Published on March 06, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - birth of Cyrano de Bergerac

March 6

1619 Cyrano de Bergerac was born. The real Cyrano was a soldier, duelist, dramatist and satirist, and inspired several romantic legends, the most famous of them Edmund Rostand's play.

1619 Cyrano de Bergerac was born. The real Cyrano was a soldier, duelist, dramatist and satirist, and inspired several romantic legends, the most famous of them Edmund Rostand's play.

Published on March 06, 2016 02:00

March 5, 2016

7 things that happened in March through history

History Extra

Submitted by: Dominic Sandbrook

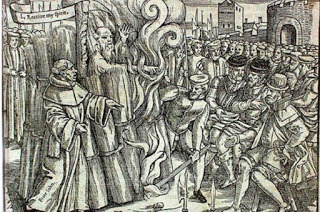

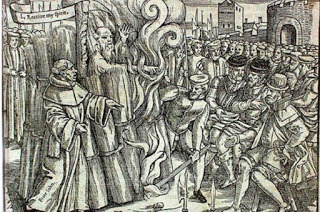

Thomas Cranmer thrusts his hand into the flames that would soon burn him alive in this woodcut from John Foxe’s 1563 Book of Martyrs. © Bridgeman

Thomas Cranmer thrusts his hand into the flames that would soon burn him alive in this woodcut from John Foxe’s 1563 Book of Martyrs. © Bridgeman

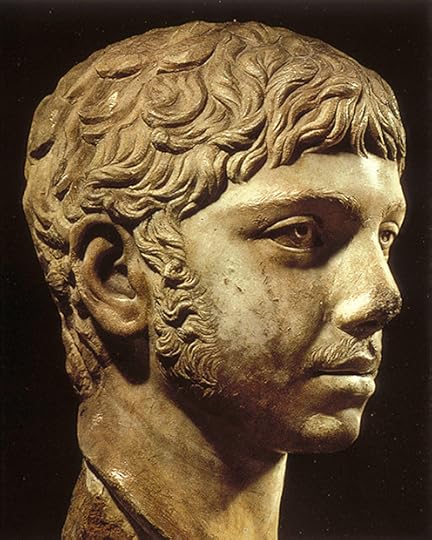

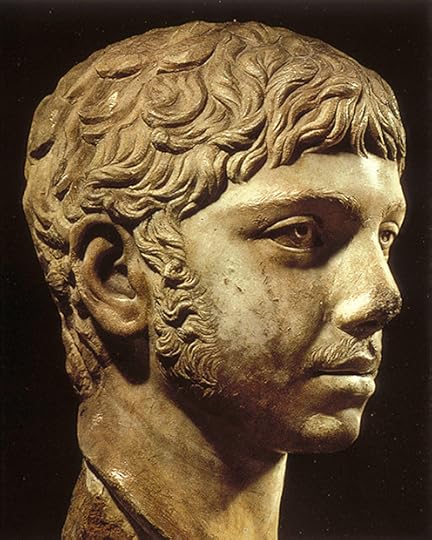

11 March AD 222: Rome’s emperor of excess meets a bloody endEven in the lurid parade of Roman emperors, Elagabalus stands out. Born into the imperial Severan dynasty in c203 AD, he found himself catapulted to supreme power in his early teens and soon began to court controversy.

To the horror of the Roman elite, their teenage emperor – whose real name was Marcus Aurelius Antoninus – had signed up to the cult of the Syrian sun god Elagabalus, after whom he now named himself. Once emperor, he renamed his god Deus Sol Invictus – God the Undefeated Sun – and installed him at the head of the Roman pantheon. Then he declared himself high priest, had himself publicly circumcised and made the city’s bigwigs watch while he danced around the Sun’s new altar.

A contemporary sculpture of Elagabalus, an emperor known for his excesses. © AKG

In the meantime, Elagabalus’s sexual conduct was raising eyebrows across the city. In total he married and divorced five women, but his chief relationships seem to have been with his chariot-driver, a male slave called Hierocles, and an athlete from Asia Minor called Zoticus. According to gossip, the emperor “set aside a room in the palace and there committed his indecencies, always standing nude at the door of the room, as the harlots do… while in a soft and melting voice he solicited the passers-by”. If any doctor could give him female genitalia, he said, he would give him a fortune.

Eventually, the Praetorian Guard, sick of their emperor’s excesses, switched their allegiance to his cousin Severus Alexander and turned on Elagabalus.

As the historian Cassius Dio recorded, there was no mercy for either Elagabalus or his mother: “Their heads were cut off and their bodies, after being stripped naked, were first dragged all over the city, and then the mother’s body was cast aside somewhere or other while his was thrown into the river.”

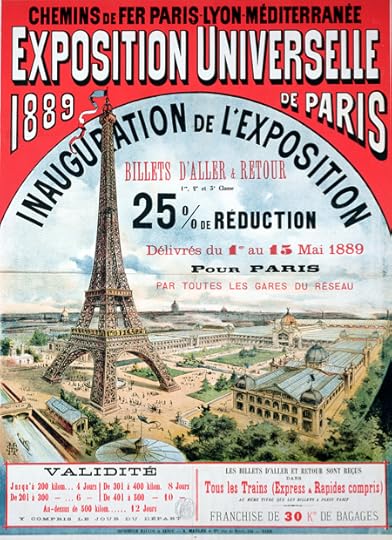

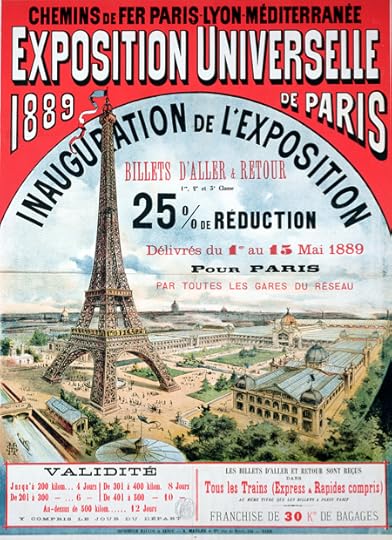

31 March 1889: France’s iconic tower opensThe Eiffel Tower had a troubled birth. Conceived by engineers Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier as the centrepiece of the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition, it was built by the celebrated bridge-maker Gustave Eiffel, who claimed it would celebrate “not only the art of the modern engineer, but also the century of Industry and Science in which we are living, and for which the way was prepared by the great scientific movement of the 18th century and by the Revolution of 1789”.

Most of the French intellectual establishment hated the idea. It would be “useless and monstrous”, a “hateful column of bolted sheet metal”, claimed a petition signed by some 300 writers and artists. But Eiffel was having none of it, even comparing his new structure to the pyramids of Egypt. “My tower will be the tallest edifice ever erected by man,” he wrote. “Will it not also be grandiose in its way? And why would something admirable in Egypt become hideous and ridiculous in Paris?”

A poster advertising reduced train tickets to the Exposition Universelle of 1889. The Eiffel Tower was the crowning glory of the exhibition, but the first visitors needed to be fit: on its opening, none of the lifts were working. © Bridgeman

In fact, when the tower was finally opened to the government and press on 31 March 1889, it was not quite finished. Crucially, the lifts were not yet working, so the visiting party had to trudge up the stairs on foot. Most gave up and remained on the lower levels; only a handful made it to the top, where Eiffel hoisted a gigantic French flag, greeted by fireworks and a 21-gun salute.

The tower was an instant hit: illuminated every night by gas lamps, it dominated not just the Exposition, but Paris itself. When the public were finally allowed in, the lifts were still not working. Yet in the first week alone, almost 30,000 people climbed to the top – a sign of how completely it had caught the world’s imagination.

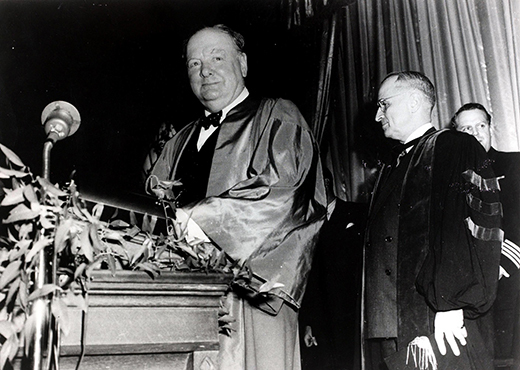

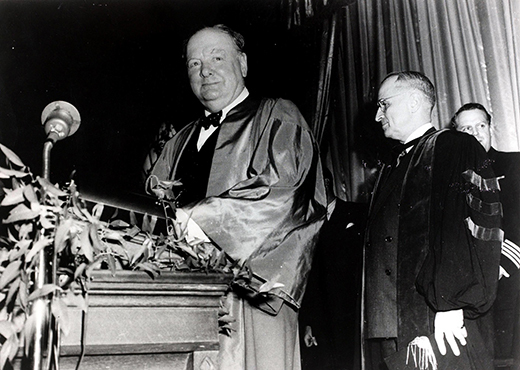

5 March 1946: Churchill warns of an ‘iron curtain’ falling across EuropeIn the spring of 1946, Winston Churchill arrived in Fulton, Missouri. The little Midwestern town seemed an unlikely destination for the man who, until the previous summer, had been leading the world’s largest empire. But Churchill, rejected by the British electorate, was in the doldrums. When President Harry Truman invited him to give a lecture at a little college in his home state, Churchill saw it as a chance to revive his American reputation.

Churchill and Truman travelled to Fulton by train and on the way the president read a draft of the former prime minister’s talk. It was, he declared, excellent. But when Churchill stood up on 5 March, in the packed gymnasium at Westminster College, few could have expected that his words would resound in history.

Winston Churchill delivers his speech alongside President Harry Truman in Fulton, Missouri. His words herald a new era of Cold War across Europe and an end to good relations with the Soviet Union. © Getty

A shadow, he explained, had fallen “upon the scenes so lately lighted by the Allied victory” – thanks entirely to Stalin’s Soviet Union. “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic,” he declared, “an iron curtain has descended across the continent.” That made Anglo-American co-operation all the more important. Theirs, Churchill added, was a “special relationship”.

Churchill was not the first man to use the words ‘iron curtain’, but he was unquestionably the most famous. After that day in Fulton, there was no doubt that the alliance between Stalin’s Soviet Union and the two great western powers was over – and that the Cold War had begun.

21 March 1556: Thomas Cranmer burns at the stakeBy the early 1550s, Thomas Cranmer had a good claim to be one of the most influential men in English history.

As archbishop of Canterbury, he had laid the foundations for the new Church of England, attacking monasticism and the doctrine of the Mass, compiling the Book of Common Prayer and establishing the king, not the pope, as head of the church. But when the Catholic Mary succeeded her brother, young Edward VI in 1553, Cranmer was in trouble. Arrested that autumn, he publicly recanted in an attempt to save his skin. But it was no good. Even though he had abjured all his Protestant views, Mary wanted him to burn.

On 21 March 1556, the day scheduled for his execution, Cranmer was ordered to make a final recantation at the University Church in Oxford. He wrote out his text and submitted it to the authorities. But then, once in the pulpit, he did something quite extraordinary. Unexpectedly abandoning his text, Cranmer withdrew all that he had “written for fear of death, and to save my life”.

“And forasmuch as my hand offended in writing contrary to my heart,” he added, “therefore my hand shall first be punished: for if I may come to the fire, it shall be first burned. And as for the pope, I refuse him, as Christ’s enemy and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine.”

By now the place was in uproar. Guards dragged Cranmer from the pulpit to the spot at St Giles where other martyrs had been burned. And there, “apparently insensible of pain”, this exceptionally courageous man met his end, plunging his right hand into the flames first, as he had promised. His last words were a cry almost of exaltation: “I see the heavens open, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God.”

Expert comment - Dr Linda Porter:

For the beleaguered Protestants of Mary I’s England, the burning at the stake of Thomas Cranmer must have seemed a moment of both despair and triumph. They had lost their spiritual leader and yet the drama surrounding his death denied Catholicism a victory.

Uncertainty, even ambiguity, had long been present in Cranmer’s own life. He pronounced the end of Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon, yet could not save Anne Boleyn. He was present at the king’s deathbed, exhorting him to put his trust in Christ, although Henry had continued to hear Mass throughout his reign.

As mentor to both Katherine Parr and Edward VI, Cranmer encouraged religious reform, but was willing to deny it all rather than be burned alive. His sisters, one Catholic, the other Protestant, fought for his soul in 1556. It was then that he discovered that the agonies of indecision, of abjuring the work of a lifetime, were worse than the ordeal in the flames. Cranmer chose to follow his beliefs in the most dramatic way, by unexpectedly upholding them with superb timing and oratory on the day of his death.

Thomas Cromwell may be the Tudor man of the moment, but it is to Cranmer that we owe the liturgy of the Church of England. His 1552 prayer book remains one of the glories of the English language. In its beauty, we can still know this complex and deeply learned man.

Dr Linda Porter is the author of three books on the Tudor period. She is currently writing a book about the children of Charles I and the Civil War.

Three other notable March anniversaries19 March 1649

Having executed Charles I, the House of Commons passes an act abolishing the House of Lords, which it calls “useless and dangerous to the people of England”.

23 March 1801

In St Petersburg, Tsar Paul I is attacked by disgruntled Russian officers, who strike him down with a sword before strangling and stamping him to death.

29 March 1461

At Towton in Yorkshire, Edward IV leads the Yorkists to victory over the Lancastrian army – led by the Duke of Somerset – in the bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil.

Dominic Sandbrook recently presented Tomorrow’s Worlds: The Unearthly History of Science Fiction on BBC Two.

Submitted by: Dominic Sandbrook

Thomas Cranmer thrusts his hand into the flames that would soon burn him alive in this woodcut from John Foxe’s 1563 Book of Martyrs. © Bridgeman

Thomas Cranmer thrusts his hand into the flames that would soon burn him alive in this woodcut from John Foxe’s 1563 Book of Martyrs. © Bridgeman 11 March AD 222: Rome’s emperor of excess meets a bloody endEven in the lurid parade of Roman emperors, Elagabalus stands out. Born into the imperial Severan dynasty in c203 AD, he found himself catapulted to supreme power in his early teens and soon began to court controversy.

To the horror of the Roman elite, their teenage emperor – whose real name was Marcus Aurelius Antoninus – had signed up to the cult of the Syrian sun god Elagabalus, after whom he now named himself. Once emperor, he renamed his god Deus Sol Invictus – God the Undefeated Sun – and installed him at the head of the Roman pantheon. Then he declared himself high priest, had himself publicly circumcised and made the city’s bigwigs watch while he danced around the Sun’s new altar.

A contemporary sculpture of Elagabalus, an emperor known for his excesses. © AKG

In the meantime, Elagabalus’s sexual conduct was raising eyebrows across the city. In total he married and divorced five women, but his chief relationships seem to have been with his chariot-driver, a male slave called Hierocles, and an athlete from Asia Minor called Zoticus. According to gossip, the emperor “set aside a room in the palace and there committed his indecencies, always standing nude at the door of the room, as the harlots do… while in a soft and melting voice he solicited the passers-by”. If any doctor could give him female genitalia, he said, he would give him a fortune.

Eventually, the Praetorian Guard, sick of their emperor’s excesses, switched their allegiance to his cousin Severus Alexander and turned on Elagabalus.

As the historian Cassius Dio recorded, there was no mercy for either Elagabalus or his mother: “Their heads were cut off and their bodies, after being stripped naked, were first dragged all over the city, and then the mother’s body was cast aside somewhere or other while his was thrown into the river.”

31 March 1889: France’s iconic tower opensThe Eiffel Tower had a troubled birth. Conceived by engineers Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier as the centrepiece of the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition, it was built by the celebrated bridge-maker Gustave Eiffel, who claimed it would celebrate “not only the art of the modern engineer, but also the century of Industry and Science in which we are living, and for which the way was prepared by the great scientific movement of the 18th century and by the Revolution of 1789”.

Most of the French intellectual establishment hated the idea. It would be “useless and monstrous”, a “hateful column of bolted sheet metal”, claimed a petition signed by some 300 writers and artists. But Eiffel was having none of it, even comparing his new structure to the pyramids of Egypt. “My tower will be the tallest edifice ever erected by man,” he wrote. “Will it not also be grandiose in its way? And why would something admirable in Egypt become hideous and ridiculous in Paris?”

A poster advertising reduced train tickets to the Exposition Universelle of 1889. The Eiffel Tower was the crowning glory of the exhibition, but the first visitors needed to be fit: on its opening, none of the lifts were working. © Bridgeman

In fact, when the tower was finally opened to the government and press on 31 March 1889, it was not quite finished. Crucially, the lifts were not yet working, so the visiting party had to trudge up the stairs on foot. Most gave up and remained on the lower levels; only a handful made it to the top, where Eiffel hoisted a gigantic French flag, greeted by fireworks and a 21-gun salute.

The tower was an instant hit: illuminated every night by gas lamps, it dominated not just the Exposition, but Paris itself. When the public were finally allowed in, the lifts were still not working. Yet in the first week alone, almost 30,000 people climbed to the top – a sign of how completely it had caught the world’s imagination.

5 March 1946: Churchill warns of an ‘iron curtain’ falling across EuropeIn the spring of 1946, Winston Churchill arrived in Fulton, Missouri. The little Midwestern town seemed an unlikely destination for the man who, until the previous summer, had been leading the world’s largest empire. But Churchill, rejected by the British electorate, was in the doldrums. When President Harry Truman invited him to give a lecture at a little college in his home state, Churchill saw it as a chance to revive his American reputation.

Churchill and Truman travelled to Fulton by train and on the way the president read a draft of the former prime minister’s talk. It was, he declared, excellent. But when Churchill stood up on 5 March, in the packed gymnasium at Westminster College, few could have expected that his words would resound in history.

Winston Churchill delivers his speech alongside President Harry Truman in Fulton, Missouri. His words herald a new era of Cold War across Europe and an end to good relations with the Soviet Union. © Getty

A shadow, he explained, had fallen “upon the scenes so lately lighted by the Allied victory” – thanks entirely to Stalin’s Soviet Union. “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic,” he declared, “an iron curtain has descended across the continent.” That made Anglo-American co-operation all the more important. Theirs, Churchill added, was a “special relationship”.

Churchill was not the first man to use the words ‘iron curtain’, but he was unquestionably the most famous. After that day in Fulton, there was no doubt that the alliance between Stalin’s Soviet Union and the two great western powers was over – and that the Cold War had begun.

21 March 1556: Thomas Cranmer burns at the stakeBy the early 1550s, Thomas Cranmer had a good claim to be one of the most influential men in English history.

As archbishop of Canterbury, he had laid the foundations for the new Church of England, attacking monasticism and the doctrine of the Mass, compiling the Book of Common Prayer and establishing the king, not the pope, as head of the church. But when the Catholic Mary succeeded her brother, young Edward VI in 1553, Cranmer was in trouble. Arrested that autumn, he publicly recanted in an attempt to save his skin. But it was no good. Even though he had abjured all his Protestant views, Mary wanted him to burn.

On 21 March 1556, the day scheduled for his execution, Cranmer was ordered to make a final recantation at the University Church in Oxford. He wrote out his text and submitted it to the authorities. But then, once in the pulpit, he did something quite extraordinary. Unexpectedly abandoning his text, Cranmer withdrew all that he had “written for fear of death, and to save my life”.

“And forasmuch as my hand offended in writing contrary to my heart,” he added, “therefore my hand shall first be punished: for if I may come to the fire, it shall be first burned. And as for the pope, I refuse him, as Christ’s enemy and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine.”

By now the place was in uproar. Guards dragged Cranmer from the pulpit to the spot at St Giles where other martyrs had been burned. And there, “apparently insensible of pain”, this exceptionally courageous man met his end, plunging his right hand into the flames first, as he had promised. His last words were a cry almost of exaltation: “I see the heavens open, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God.”

Expert comment - Dr Linda Porter:

For the beleaguered Protestants of Mary I’s England, the burning at the stake of Thomas Cranmer must have seemed a moment of both despair and triumph. They had lost their spiritual leader and yet the drama surrounding his death denied Catholicism a victory.

Uncertainty, even ambiguity, had long been present in Cranmer’s own life. He pronounced the end of Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon, yet could not save Anne Boleyn. He was present at the king’s deathbed, exhorting him to put his trust in Christ, although Henry had continued to hear Mass throughout his reign.

As mentor to both Katherine Parr and Edward VI, Cranmer encouraged religious reform, but was willing to deny it all rather than be burned alive. His sisters, one Catholic, the other Protestant, fought for his soul in 1556. It was then that he discovered that the agonies of indecision, of abjuring the work of a lifetime, were worse than the ordeal in the flames. Cranmer chose to follow his beliefs in the most dramatic way, by unexpectedly upholding them with superb timing and oratory on the day of his death.

Thomas Cromwell may be the Tudor man of the moment, but it is to Cranmer that we owe the liturgy of the Church of England. His 1552 prayer book remains one of the glories of the English language. In its beauty, we can still know this complex and deeply learned man.

Dr Linda Porter is the author of three books on the Tudor period. She is currently writing a book about the children of Charles I and the Civil War.

Three other notable March anniversaries19 March 1649

Having executed Charles I, the House of Commons passes an act abolishing the House of Lords, which it calls “useless and dangerous to the people of England”.

23 March 1801

In St Petersburg, Tsar Paul I is attacked by disgruntled Russian officers, who strike him down with a sword before strangling and stamping him to death.

29 March 1461

At Towton in Yorkshire, Edward IV leads the Yorkists to victory over the Lancastrian army – led by the Duke of Somerset – in the bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil.

Dominic Sandbrook recently presented Tomorrow’s Worlds: The Unearthly History of Science Fiction on BBC Two.

Published on March 05, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Odocacer executed

March 5

493 the German barbarian leader Odovacar (Odocacer), who had ended the Western Roman Empire in 476, was executed at age 59 by the Ostrogoths.

493 the German barbarian leader Odovacar (Odocacer), who had ended the Western Roman Empire in 476, was executed at age 59 by the Ostrogoths.

Published on March 05, 2016 02:30