MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 121

February 4, 2016

Spectacular Statuettes of Apollo and Artemis Discovered in Rare State of Preservation in Crete

Ancient Origins

While the size of the find may be small, the quality is great. Archaeologists working in Aptera in Iraklio, Crete, have recently unearthed well-preserved statuettes of the mythical Greek goddess Artemis and her twin brother Apollo.

While the size of the find may be small, the quality is great. Archaeologists working in Aptera in Iraklio, Crete, have recently unearthed well-preserved statuettes of the mythical Greek goddess Artemis and her twin brother Apollo.

The Artemis sculpture is cast in bronze and depicts the goddess in the process of firing an arrow. The head of the excavation at the site in Aptera, Vanna Niniou-Kindeli, said that the goddess statuette was found in an excellent state or preservation, with all of her limbs intact.

Detail of the front of the Artemis bronze sculpture. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)The Artemis statuette is wearing a short chiton (tunic) and even the white material used for her eyes has been preserved. She was found with the bronze base that the sculpture would have stood upon. The Greek News Agent Ethnos reports that the statuette would have measured 54cm (21.3 inches) tall with the base and is 35cm (13.8 inches) tall without it.

Detail of the front of the Artemis bronze sculpture. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)The Artemis statuette is wearing a short chiton (tunic) and even the white material used for her eyes has been preserved. She was found with the bronze base that the sculpture would have stood upon. The Greek News Agent Ethnos reports that the statuette would have measured 54cm (21.3 inches) tall with the base and is 35cm (13.8 inches) tall without it.

Back view of the Artemis sculpture from Aptera, Crete. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)In Greek mythology, Artemis was the goddess of nature, chastity, virginity, the hunt, and the moon. According to legends, Artemis and Apollo were the children of Zeus and Leto, and soon after her birth, Artemis helped her mother to give birth to her twin brother. Afterwards, she asked her father to allow her to remain chaste for her life – which she chose to devote to hunting and protecting the natural environment.

Back view of the Artemis sculpture from Aptera, Crete. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)In Greek mythology, Artemis was the goddess of nature, chastity, virginity, the hunt, and the moon. According to legends, Artemis and Apollo were the children of Zeus and Leto, and soon after her birth, Artemis helped her mother to give birth to her twin brother. Afterwards, she asked her father to allow her to remain chaste for her life – which she chose to devote to hunting and protecting the natural environment.

Site in Athens revealed as an ancient temple of twin gods Apollo and Artemis The Grand and Sacred Temple of Artemis, A Wonder of the Ancient World Underwater settlement and ancient pottery workshop discovered near Delos, birthplace of Sun God Apollo The statuette of the Greek god Apollo is arguably less-impressive than that of his sister, but still shows artistic talent. The Apollo sculpture is carved out of marble and measures approximately 54cm (21.3 inches) with the base as well. The International Business Times reports that the Apollo statue has a “rare preservation” of red coloring in some of the creases of the base, suggesting it was painted.

The marble statue of Apollo. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)In contrast to his twin sister, Apollo was the Greek god of music, healing, light, and truth. Like his sister he was also an archer. Two important tasks given to Apollo were giving the science of medicine to man and moving the sun across the sky each day.

The marble statue of Apollo. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)In contrast to his twin sister, Apollo was the Greek god of music, healing, light, and truth. Like his sister he was also an archer. Two important tasks given to Apollo were giving the science of medicine to man and moving the sun across the sky each day.

First estimates suggest that the sculptures are from the late 1st – early 2nd century AD. The archaeologists believe that the two figures were probably imported to Crete and originally used to decorate the altar of a Roman luxury residence or were used for decorative purposes at the Roman-era Villa in which they were found.

The base the statues of Artemis and Apollo once stood upon. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)Vanna Niniou-Kindeli told Ethnos that the statues will be added to the collection of the Archaeological Museum of Chania on Crete. She also emphasized the support of the Region of Crete and the district commissioner Stavros Arnaoutakis in the excavations to the same source.

The base the statues of Artemis and Apollo once stood upon. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)Vanna Niniou-Kindeli told Ethnos that the statues will be added to the collection of the Archaeological Museum of Chania on Crete. She also emphasized the support of the Region of Crete and the district commissioner Stavros Arnaoutakis in the excavations to the same source.

Artemis was perhaps the more popular twin for devotion, however temples and sites that worshipped both she and her brother Apollo have been found. Last year, Ancient Origins reported that the twins were also discovered to have been worshipped together at a site for divination via hydromancy in Athens, Greece. The combined honoring of the siblings was described as:

By Alicia McDermott

While the size of the find may be small, the quality is great. Archaeologists working in Aptera in Iraklio, Crete, have recently unearthed well-preserved statuettes of the mythical Greek goddess Artemis and her twin brother Apollo.

While the size of the find may be small, the quality is great. Archaeologists working in Aptera in Iraklio, Crete, have recently unearthed well-preserved statuettes of the mythical Greek goddess Artemis and her twin brother Apollo. The Artemis sculpture is cast in bronze and depicts the goddess in the process of firing an arrow. The head of the excavation at the site in Aptera, Vanna Niniou-Kindeli, said that the goddess statuette was found in an excellent state or preservation, with all of her limbs intact.

Detail of the front of the Artemis bronze sculpture. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)The Artemis statuette is wearing a short chiton (tunic) and even the white material used for her eyes has been preserved. She was found with the bronze base that the sculpture would have stood upon. The Greek News Agent Ethnos reports that the statuette would have measured 54cm (21.3 inches) tall with the base and is 35cm (13.8 inches) tall without it.

Detail of the front of the Artemis bronze sculpture. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)The Artemis statuette is wearing a short chiton (tunic) and even the white material used for her eyes has been preserved. She was found with the bronze base that the sculpture would have stood upon. The Greek News Agent Ethnos reports that the statuette would have measured 54cm (21.3 inches) tall with the base and is 35cm (13.8 inches) tall without it.  Back view of the Artemis sculpture from Aptera, Crete. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)In Greek mythology, Artemis was the goddess of nature, chastity, virginity, the hunt, and the moon. According to legends, Artemis and Apollo were the children of Zeus and Leto, and soon after her birth, Artemis helped her mother to give birth to her twin brother. Afterwards, she asked her father to allow her to remain chaste for her life – which she chose to devote to hunting and protecting the natural environment.

Back view of the Artemis sculpture from Aptera, Crete. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)In Greek mythology, Artemis was the goddess of nature, chastity, virginity, the hunt, and the moon. According to legends, Artemis and Apollo were the children of Zeus and Leto, and soon after her birth, Artemis helped her mother to give birth to her twin brother. Afterwards, she asked her father to allow her to remain chaste for her life – which she chose to devote to hunting and protecting the natural environment. Site in Athens revealed as an ancient temple of twin gods Apollo and Artemis The Grand and Sacred Temple of Artemis, A Wonder of the Ancient World Underwater settlement and ancient pottery workshop discovered near Delos, birthplace of Sun God Apollo The statuette of the Greek god Apollo is arguably less-impressive than that of his sister, but still shows artistic talent. The Apollo sculpture is carved out of marble and measures approximately 54cm (21.3 inches) with the base as well. The International Business Times reports that the Apollo statue has a “rare preservation” of red coloring in some of the creases of the base, suggesting it was painted.

The marble statue of Apollo. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)In contrast to his twin sister, Apollo was the Greek god of music, healing, light, and truth. Like his sister he was also an archer. Two important tasks given to Apollo were giving the science of medicine to man and moving the sun across the sky each day.

The marble statue of Apollo. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)In contrast to his twin sister, Apollo was the Greek god of music, healing, light, and truth. Like his sister he was also an archer. Two important tasks given to Apollo were giving the science of medicine to man and moving the sun across the sky each day. First estimates suggest that the sculptures are from the late 1st – early 2nd century AD. The archaeologists believe that the two figures were probably imported to Crete and originally used to decorate the altar of a Roman luxury residence or were used for decorative purposes at the Roman-era Villa in which they were found.

The base the statues of Artemis and Apollo once stood upon. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)Vanna Niniou-Kindeli told Ethnos that the statues will be added to the collection of the Archaeological Museum of Chania on Crete. She also emphasized the support of the Region of Crete and the district commissioner Stavros Arnaoutakis in the excavations to the same source.

The base the statues of Artemis and Apollo once stood upon. (

Greek Ministry of Culture

)Vanna Niniou-Kindeli told Ethnos that the statues will be added to the collection of the Archaeological Museum of Chania on Crete. She also emphasized the support of the Region of Crete and the district commissioner Stavros Arnaoutakis in the excavations to the same source. Artemis was perhaps the more popular twin for devotion, however temples and sites that worshipped both she and her brother Apollo have been found. Last year, Ancient Origins reported that the twins were also discovered to have been worshipped together at a site for divination via hydromancy in Athens, Greece. The combined honoring of the siblings was described as:

“[…] a yin and yang type of dichotomy: Apollo, famous for his pursuit of nymphs, was worshiped as the protector of domestic flocks and herds and the patron of the founding of colonies and cities. While Artemis, who protected girls, seems to recall an earlier time as the goddess of hunting and nature.“Featured Image: The bronze statuette of Artemis and the marble one of Apollo. Source: Greek Ministry of Culture

By Alicia McDermott

Published on February 04, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Richard I of England ransomed

February 4

1194 King Richard I of England was freed by Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor, after being ransomed. Richard did return to England but soon set sail for France where he died five years later.

1194 King Richard I of England was freed by Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor, after being ransomed. Richard did return to England but soon set sail for France where he died five years later.

Published on February 04, 2016 02:00

February 3, 2016

Psychic Readings by Gladys Quintal

"Private Message Photo Readings" are $20 payable via PayPal (PayPal link). If you are interested in a reading, please sort out payment and then message me your photo.Facebook link- Reading photos- sensing spirits around you- medical intuitiveYou must be 18+ for a reading. I can only read photos of you or a loved one that has passed over. I cannot read people without their permission, so please don't ask me to read your spouse/boyfriend etc. Please allow up to 48 hrs for your reading, though I will endeavour to get it back to you ASAP.

Published on February 03, 2016 07:36

The face of Cleopatra: was she really so beautiful?

History Extra

The image of Cleopatra on the silver denarius dated to 32 BC being displayed at Newcastle University, 14 February 2007. (Scott Heppell/AP/Press Association Images)

Cleopatra is always newsworthy. So when in February 2007 a small coin in the collection of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle was said to have changed our understanding of her, it made headlines around the world.

Journalists reacted with shock. Cleopatra was no beauty queen, said the reports. The face on the coin was nothing like that of Elizabeth Taylor. Instead she looked “plain”, even “shrewish”, and had a “hook-like hooter”. This was announced as a revelation.

Yet for all the fanfare, there was nothing particularly unusual about the Newcastle coin. There are plenty of coins surviving with Cleopatra’s portrait on them, and they generally repeat the same features that seemed to astound reporters: a prominent nose, sloping forehead, sharply pointed chin and thin lips, and hollow-looking eye sockets.

These coin portraits, surprising though they may be to those who have grown up with a ‘Hollywood Cleopatra’, are the only certain images we have of her. That hasn’t stopped people from attempting to dismiss them as inaccurate and overly stylised – hoping against hope that there could have been another face of Cleopatra, a hidden one whose face would better match our expectations. Perhaps, they suggest, these unconvincing portraits were the work of unskilled artists.

There’s no reason to think these coin portraits are wrong, however. At the time, a warts-and-all approach to portraiture was in vogue in the Mediterranean world, and it seems that Cleopatra’s image was no exception to this trend. Features like large noses or determined chins may have been slightly exaggerated, but only because those features were the most recognisable attributes of the individual being portrayed. In this sense they were intended to be realistic.

Coin portraits of Cleopatra’s father, much rarer than those of Cleopatra herself, show him with a prominent nose and sloping forehead, so these physical characteristics may well have been family traits. Her lovers don’t match modern popular conceptions either: Caesar has a wrinkled, scrawny neck and hides his bald head with a crown, and Antony’s jutting chin and broken nose bear no resemblance to Richard Burton’s features.

Image of Antony, Cleopatra’s lover, on a 2,000-year-old silver coin. (Owen Humphreys/PA Wire)

The coins were minted in a variety of places in the eastern Mediterranean, from Alexandria in Egypt to the port of Patras in Greece. Mark Antony bestowed on Cleopatra a number of eastern cities and territories, and coins were issued in those places in the name of the new ruler. Though the portraits found on the coins vary in style from artist to artist, they are generally consistent in detail, which suggests that the artists were following guidelines when they engraved the dies to strike the coins. It’s likely that they were copying an official image that the queen herself had approved – nose and chin included.

The 7 best couples in history Despite her legendary fondness for dressing up, the portraits are rather modest. Cleopatra wears the cloth diadem of a Hellenistic ruler around her head. Her hair is drawn back in braids and coiled in a bun at the base of her skull. Over her shoulders she wears a mantle, covering her gown. A discreet earring hangs from her earlobe, and around her neck is a string of pearls – the only hint of the riches described by the Roman poet Lucan, who pictures a dissolute Cleopatra as decked out “on neck and hair with all the Red Sea spoils”. On some coins her mantle seems to be held in place by a clasp that includes more strings of pearls – a treasure that perhaps held great significance at the time (a gift from Caesar or Antony?).

Most of the coin portraits date to the mid to late 30s BC, when Cleopatra herself was in her mid to late thirties. Often she is associated with Mark Antony, whose portrait appears on the other side (and occasionally on the same side, next to hers), but she is always described as a queen in her own right, and not just Antony’s consort: “Queen Cleopatra, the New Goddess”; “For Cleopatra, Queen of Kings and of children who are kings”. On some coins depicting her by herself there is no name attached at all – those distinctive features told people who they were looking at.

A coin with the head of Cleopatra. (Photo by Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images)

The modern negative reaction to the face of Cleopatra tells us more about our love of stories than anything about this most famous of Egyptian queens, who ruled from 51 to 30 BC. For us, the reality of her coin portraits clashes with the much greater myth of Cleopatra, a myth so grand that it has practically consumed the person behind it.

Hollywood did not invent the tradition of the beautiful seductress; that we can believe so says much about its influence in our world. Instead it simply followed a longstanding convention. Hardly had Cleopatra died (allegedly from an asp bite) than the legends began to accrue. In 31 BC she and her lover, Mark Antony, had been defeated by their rival Octavian, and in the following year they committed suicide in Egypt. Octavian had triumphed, but he was the victor in a vicious civil war that had pitted Roman against Roman.

6 things you (probably) didn’t know about Cleopatra Cleopatra was a convenient scapegoat. Octavian claimed to have waged war against the foreign queen, not Antony. In this way Antony could be portrayed as a virtuous Roman who had betrayed his homeland through the machinations of an evil temptress. Cleopatra was cast as an irresistible and exotic femme fatale, and Roman writers picked up the theme. The poet Horace declared her a “deadly monster”, and Propertius, with even less delicacy, called the queen a “whore”. Yet she needed more exceptional qualities to have conquered both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony: according to the Roman historian Cassius Dio she was “a woman of surpassing beauty… with the power to subjugate everyone”.

But not all were taken in by this. The Greek biographer Plutarch, writing about a century after Cleopatra’s death, had his doubts about her unparalleled physical qualities. “Her beauty was in itself not altogether incomparable’”, he wrote, “nor such as to strike those who saw her”, but he nonetheless credits her with an “irresistible charm”. Intelligent and talented, Cleopatra had a gift for making people feel they were the focus of her attention – and that quality, rather than her looks, was her winning trait with Caesar and Antony. Even Cassius Dio conceded that Cleopatra “had a knowledge of how to make herself agreeable to everyone”. This is perhaps the closest we can get to the real Cleopatra and the character behind the face on the coins.

The beautiful and scheming seductress was a creation of Octavian’s propaganda, and unwittingly he created history’s greatest love story. But the coins present us with another kind of story – of two ambitious political figures weaving a future together: Antony the Roman triumvir and Cleopatra the queen of kings. Not as romantic, but possibly a face of Cleopatra that the queen herself would have recognised, and of which she would have approved.

Professor Kevin Butcher from the University of Warwick is the co-author of The Metallurgy of Roman Silver Coinage: From the Reform of Nero to the Reform of Trajan, (Cambridge University Press, 2014). Prof Butcher’s research interests include Greek and Roman coinage, particularly the civic and provincial coinages of the Roman empire, and the Hellenistic and Roman Near East, particularly coastal Syria and Lebanon.

The image of Cleopatra on the silver denarius dated to 32 BC being displayed at Newcastle University, 14 February 2007. (Scott Heppell/AP/Press Association Images)

Cleopatra is always newsworthy. So when in February 2007 a small coin in the collection of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle was said to have changed our understanding of her, it made headlines around the world.

Journalists reacted with shock. Cleopatra was no beauty queen, said the reports. The face on the coin was nothing like that of Elizabeth Taylor. Instead she looked “plain”, even “shrewish”, and had a “hook-like hooter”. This was announced as a revelation.

Yet for all the fanfare, there was nothing particularly unusual about the Newcastle coin. There are plenty of coins surviving with Cleopatra’s portrait on them, and they generally repeat the same features that seemed to astound reporters: a prominent nose, sloping forehead, sharply pointed chin and thin lips, and hollow-looking eye sockets.

These coin portraits, surprising though they may be to those who have grown up with a ‘Hollywood Cleopatra’, are the only certain images we have of her. That hasn’t stopped people from attempting to dismiss them as inaccurate and overly stylised – hoping against hope that there could have been another face of Cleopatra, a hidden one whose face would better match our expectations. Perhaps, they suggest, these unconvincing portraits were the work of unskilled artists.

There’s no reason to think these coin portraits are wrong, however. At the time, a warts-and-all approach to portraiture was in vogue in the Mediterranean world, and it seems that Cleopatra’s image was no exception to this trend. Features like large noses or determined chins may have been slightly exaggerated, but only because those features were the most recognisable attributes of the individual being portrayed. In this sense they were intended to be realistic.

Coin portraits of Cleopatra’s father, much rarer than those of Cleopatra herself, show him with a prominent nose and sloping forehead, so these physical characteristics may well have been family traits. Her lovers don’t match modern popular conceptions either: Caesar has a wrinkled, scrawny neck and hides his bald head with a crown, and Antony’s jutting chin and broken nose bear no resemblance to Richard Burton’s features.

Image of Antony, Cleopatra’s lover, on a 2,000-year-old silver coin. (Owen Humphreys/PA Wire)

The coins were minted in a variety of places in the eastern Mediterranean, from Alexandria in Egypt to the port of Patras in Greece. Mark Antony bestowed on Cleopatra a number of eastern cities and territories, and coins were issued in those places in the name of the new ruler. Though the portraits found on the coins vary in style from artist to artist, they are generally consistent in detail, which suggests that the artists were following guidelines when they engraved the dies to strike the coins. It’s likely that they were copying an official image that the queen herself had approved – nose and chin included.

The 7 best couples in history Despite her legendary fondness for dressing up, the portraits are rather modest. Cleopatra wears the cloth diadem of a Hellenistic ruler around her head. Her hair is drawn back in braids and coiled in a bun at the base of her skull. Over her shoulders she wears a mantle, covering her gown. A discreet earring hangs from her earlobe, and around her neck is a string of pearls – the only hint of the riches described by the Roman poet Lucan, who pictures a dissolute Cleopatra as decked out “on neck and hair with all the Red Sea spoils”. On some coins her mantle seems to be held in place by a clasp that includes more strings of pearls – a treasure that perhaps held great significance at the time (a gift from Caesar or Antony?).

Most of the coin portraits date to the mid to late 30s BC, when Cleopatra herself was in her mid to late thirties. Often she is associated with Mark Antony, whose portrait appears on the other side (and occasionally on the same side, next to hers), but she is always described as a queen in her own right, and not just Antony’s consort: “Queen Cleopatra, the New Goddess”; “For Cleopatra, Queen of Kings and of children who are kings”. On some coins depicting her by herself there is no name attached at all – those distinctive features told people who they were looking at.

A coin with the head of Cleopatra. (Photo by Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images)

The modern negative reaction to the face of Cleopatra tells us more about our love of stories than anything about this most famous of Egyptian queens, who ruled from 51 to 30 BC. For us, the reality of her coin portraits clashes with the much greater myth of Cleopatra, a myth so grand that it has practically consumed the person behind it.

Hollywood did not invent the tradition of the beautiful seductress; that we can believe so says much about its influence in our world. Instead it simply followed a longstanding convention. Hardly had Cleopatra died (allegedly from an asp bite) than the legends began to accrue. In 31 BC she and her lover, Mark Antony, had been defeated by their rival Octavian, and in the following year they committed suicide in Egypt. Octavian had triumphed, but he was the victor in a vicious civil war that had pitted Roman against Roman.

6 things you (probably) didn’t know about Cleopatra Cleopatra was a convenient scapegoat. Octavian claimed to have waged war against the foreign queen, not Antony. In this way Antony could be portrayed as a virtuous Roman who had betrayed his homeland through the machinations of an evil temptress. Cleopatra was cast as an irresistible and exotic femme fatale, and Roman writers picked up the theme. The poet Horace declared her a “deadly monster”, and Propertius, with even less delicacy, called the queen a “whore”. Yet she needed more exceptional qualities to have conquered both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony: according to the Roman historian Cassius Dio she was “a woman of surpassing beauty… with the power to subjugate everyone”.

But not all were taken in by this. The Greek biographer Plutarch, writing about a century after Cleopatra’s death, had his doubts about her unparalleled physical qualities. “Her beauty was in itself not altogether incomparable’”, he wrote, “nor such as to strike those who saw her”, but he nonetheless credits her with an “irresistible charm”. Intelligent and talented, Cleopatra had a gift for making people feel they were the focus of her attention – and that quality, rather than her looks, was her winning trait with Caesar and Antony. Even Cassius Dio conceded that Cleopatra “had a knowledge of how to make herself agreeable to everyone”. This is perhaps the closest we can get to the real Cleopatra and the character behind the face on the coins.

The beautiful and scheming seductress was a creation of Octavian’s propaganda, and unwittingly he created history’s greatest love story. But the coins present us with another kind of story – of two ambitious political figures weaving a future together: Antony the Roman triumvir and Cleopatra the queen of kings. Not as romantic, but possibly a face of Cleopatra that the queen herself would have recognised, and of which she would have approved.

Professor Kevin Butcher from the University of Warwick is the co-author of The Metallurgy of Roman Silver Coinage: From the Reform of Nero to the Reform of Trajan, (Cambridge University Press, 2014). Prof Butcher’s research interests include Greek and Roman coinage, particularly the civic and provincial coinages of the Roman empire, and the Hellenistic and Roman Near East, particularly coastal Syria and Lebanon.

Published on February 03, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - King Sweyn of Denmark dies

February 3

1014 King Sweyn I (Forkbeard) of Denmark died. The Viking leader established a Danish empire, gained control of Norway, and conquered England. His name appears as Swegen in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

1014 King Sweyn I (Forkbeard) of Denmark died. The Viking leader established a Danish empire, gained control of Norway, and conquered England. His name appears as Swegen in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Published on February 03, 2016 02:00

February 2, 2016

Post-Black Death: a ‘golden age’ for medieval women?

History Extra

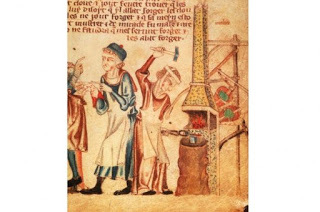

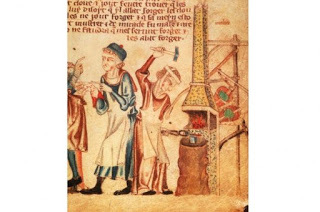

A French manuscript from c1327–35 depicts a woman forging nails. Though such opportunities did exist in London before the Black Death, they increased significantly afterwards. © AKG-Images

A French manuscript from c1327–35 depicts a woman forging nails. Though such opportunities did exist in London before the Black Death, they increased significantly afterwards. © AKG-Images

In April 1349, as the Black Death swept through London, Mathilda de Myms drew up her will. Her husband, John, had died the previous month, leaving his tenements to his wife and entrusting to her the guardianship of their daughter, Isabella. But the plague continued to ravage the capital, and Mathilda – wisely, as it transpired – decided to get her affairs in order. Shortly afterwards she was herself struck down.

John and Mathilda had run a business making religious images and paintings. Mathilda’s will arranged for her apprentice, William, to continue his training with a monk in Bermondsey Priory, and bequeathed to him the tools he needed, together with one of her best chests in which to keep them. A brewery owned by Mathilda was to be sold to pay for prayers for her and John.

That will underlines the devastating impact of the Black Death on thousands of families across the country; indeed, the disease subsequently took Isabella’s guardian. But the document also offers other insights – specifically, into opportunities that resulted from the soaring death toll.

In this instance, Mathilda clearly had wealth of her own, and the freedom to write such a will. She was briefly an early beneficiary of a period of relative economic power for women created by the sudden dearth of skilled and trained men – an era that has been dubbed a ‘golden age’.

Even before the plague afflicted London, the capital’s customary law offered women freedoms that they rarely enjoyed elsewhere in England, except perhaps in York. For example, a woman might enter into obligations on her own behalf, take on apprentices, run her own business, rent property, and sue (or be sued) for debt in the London courts. A woman – especially if she was a widow – could even write a will, as Mathilda de Myms did.

These four mortuary crosses were placed on the body of a plague victim in London c1348. It was in the capital that the Black Death had the greatest impact on women’s lives. © Wellcome Images

But after the plague struck, sending London’s population plummeting to 40,000 from a peak of 80,000 in 1300, these opportunities multiplied. In fact, the mayor and aldermen, alarmed by a chronic shortage of manpower, began actively to encourage women to exercise their new economic rights.

Eventually, the rights went further: from 1465, a widow of a citizen of London, who was living there with him at the time of his death, would be made ‘free of the city’ (a citizen) as long as she continued to live in London and did not remarry.

City authorities were especially anxious to encourage the widows of London merchants and craftsmen to continue to run their husbands’ workshops or trading enterprises, to ensure that these businesses continued to contribute to civic prosperity and taxation. Thus it became compulsory for widows to train their late husbands’ apprentices, or to make proper provision for them.

In the years following the Black Death, girl apprentices became prominent in surviving records. Though this wasn’t a new phenomenon – as early as 1276, Marion de Lymeseye was apprenticed to Roger Oriel, a paternosterer (maker of rosaries) – but in the half-century after the Black Death, from 1350 to 1400, numbers of female apprentices soared.

Fathers sometimes specified in their wills that their daughters should be apprenticed to learn a trade. Robert de Ramseye, a fishmonger who died in 1373, left 20 shillings to his daughter, Elizabeth – for her marriage, and for “putting her to a trade”.

Records are sparse – only 30 apprenticeship indentures from medieval London survive – but about a third of them relate to girls, many training in the craft of silkwork or embroidery. Their indentures, like those of boys, had to be recorded in the apprentice rolls kept at the Guildhall, and the terms of the indentures were the same, usually for seven years.

Why the rise in female apprentices at this time? For boys, a completed apprenticeship opened the way to the citizenship of London, with all its attendant political and economic advantages and responsibilities. For girls, though, this was not the case – citizenship did not follow an apprenticeship, and most went on to marry.

What was life like for a medieval housewife? A female apprentice lived in the household of her master or mistress (not always the case with servants), and was placed almost completely under their authority. The master or mistress had specific obligations to feed, clothe and nurture the apprentice and, above all, to train her in the secrets and skills of her craft. An apprenticeship provided girls with patrons and business contacts, and secured their status within the working community.

So parents from gentry families outside London knew that apprenticing daughters would provide them with the means to earn a living, and to run an independent household should that prove necessary. Unsurprisingly, then, most girls were bound by their father or brother, though one woman from Sussex bound herself as an apprentice to another woman in London.

Sole tradersMarried women in London could choose to trade separately from their husbands as femmes soles. At the time when her husband, Thomas, was serving as an alderman, around 1380, Maud Ireland traded as a femme sole silkwoman. “According to the usage of the city [she was] bound to answer her own contracts,” and she was sued for a debt owed for white silk bought from an Italian merchant.

Women were expected to make a public declaration of their sole status. In October 1457, Agnes Gower stated to the mayor and aldermen that she practised the art of a silkwoman and no other, and asked to be allowed to “merchandise” without her husband John, and to answer sole for her own contracts according to city custom. This was granted and recorded.

Some of these independent London women were doing business on a large scale. Agnes Ramsey, daughter of the noted architect and mason William Ramsey, ran her father’s business after his death in 1349. Mathilda Penne ran her husband’s business as a skinner for 12 years after his death; she trained her own apprentices and employed male servants and, possibly, a female scrivener to keep the accounts.

Twice during the 15th century, the substantial bell foundry outside Aldgate was run by widows. The household and workshop of the bell-founder Johanna Hill, who died in 1441, comprised four male apprentices, two female servants, 10 male servants, a specialised bell-maker, a clerk and the daughter of a fellow bell-founder.

Other widows continued to run the financial side of their husbands’ businesses, if not the trading or craft aspects; they pursued debtors, sorted out accounts and saw to the execution of their husbands’ wills. These women were active in maintaining their households, bolstering the welfare of their souls and managing the upbringing of their children, as well as other endeavours. Another Agnes, the widow of Stephen Forster (mayor of London 1454–55), saw to the rebuilding and reorganisation of the prison at Ludgate.

Crafty womenThese were remarkable women who made their mark in the commercial world of London and won respect within their social milieus. The records of the craft guilds and companies acknowledge the presence of women, but their role was not a formal one – rather, they shared in the religious, charitable and social aspects of company life.

Women are shown weaving in a late-medieval illustration. Women were involved in a wide range of crafts in London at this time. © Bridgeman Art Library

However, several crafts and trades recognised the contribution of women workers. In the early 15th century, for example, one-third of all brewers paying dues to the Brewers’ Company were women. Some of these were single, while others were widows or married women trading sole; one Agnes, whose husband Stephen was a draper, paid her dues independently throughout the 1420s.

Though women were seemingly marginalised within these organisations, limited to social and charitable roles, they were able to make contacts with other workers within their craft. They could also achieve recognition of their credit-worthiness and could share in, and contribute to, the material resources of their societies. To offset the imposed limitations of their role within guilds and companies, and to supplement the formal craft relationships, many created important informal networks of friends, servants, apprentices, dependants and patrons.

A female sculptor at work is illustrated in a late 15th-century painting. © BNF

However enmeshed women may have been in the social and economic networks of London life, their professional advancement was still constrained. For example, there is scant evidence of a woman holding any public office in which she might have been placed in authority over a man – such appointments would be vigorously resisted.

In 1422, the men of Queenhythe ward complained that John of Ely, the local measurer of oysters, had subcontracted his office to women “who know not how to do it; nor is it worship to this city that women should have such things in governance”. No doubt most Londoners shared the view of the men of Queenhythe; certainly, women never served as ward officers, common councilmen or, of course, aldermen. The delegation of authority to women was extremely rare, but it did happen: for more than 20 years following the death of her husband, Nicholas, in 1433, Alice Holford held the office of bailiff of London Bridge (see 'Golden girls', below).

Future gainsThe century and a half between 1350 and 1500 could reasonably be considered a ‘golden age’ for women in London – but it was short-lived. As the population swelled once more, an acute manpower shortage was replaced by a glut, and women were pushed out of the labour market. In 1570, the Drapers’ Company refused to allow a member to take on a girl apprentice “for that they had not seen the like before”.

Women continued to work after that period, of course, but in largely informal and dependent positions. London merchants were transforming themselves into country gentlemen, and it was no longer suitable for their wives to be seen trading sole. Moreover, Protestantism created a specific role for women – as godly domestic teachers within the household.

Throughout the 15th century, English society remained deeply patriarchal. The opportunities that had been available to women had been purely economic: women had no handles on power and no way of influencing political decisions. So the ‘golden age’ was golden only briefly, and was most apparent in the economic capital, London.

Nonetheless, when given the chance, these women demonstrated their ability to do men’s work. In doing so they set an important precedent, to be followed by women in the two world wars of the last century, which led directly to the greater economic and political emancipation of women today.

Golden girls

These four women exploited the opportunities presented when the plague struck

Agnes Ramsey: Mason

Agnes, who never used her husband’s name, was the daughter of the famous architect and mason William Ramsey, who was killed by the Black Death in 1349. Though married to another mason, Robert Hubard, Agnes continued to run her father’s business, entering into a contract with the dowager Queen Isabella, widow of Edward II, to build her fine tomb at the enormous cost of £100.

Alice Holford: Bailiff

Alice took over the post of bailiff of London Bridge on the death of her husband, Nicholas, in 1433, and continued in office for over 20 years. The bailiff collected the tolls due from boats passing through the bridge, and from carts that crossed it into London. The task was a complicated one – charges varied according to the goods and the person transporting them – and Alice must have had some literacy skills.

Johanna Hill: Bell-founder

On the death of her husband in 1440, Johanna took full charge of their bell-founding business till her own death in 1441. Seven of her bells still exist as far away as Ipswich, Sussex and Devon. Johanna continued to use her husband’s mark – a cross and circle within a shield – but surmounted with a lozenge to indicate that the workshop was now under her authority.

Ellen Langwith: Silkwoman

Ellen, who died in 1481, was a London silkwoman. When her first husband, cutler Philip Waltham, died she was left to train their three female apprentices. She later married a tailor, John Langwith, but continued with her own craft. She was recorded as buying gold thread and raw silk direct from Venetian merchants, and in 1465 supplied saddle decorations and silk banners for the coronation of Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Edward IV. She was courted by both the Cutlers’ and Taylors’ companies.

Caroline Barron is professor emerita at Royal Holloway, University of London, and a specialist in late medieval British history, particularly the history of women.

A French manuscript from c1327–35 depicts a woman forging nails. Though such opportunities did exist in London before the Black Death, they increased significantly afterwards. © AKG-Images

A French manuscript from c1327–35 depicts a woman forging nails. Though such opportunities did exist in London before the Black Death, they increased significantly afterwards. © AKG-Images In April 1349, as the Black Death swept through London, Mathilda de Myms drew up her will. Her husband, John, had died the previous month, leaving his tenements to his wife and entrusting to her the guardianship of their daughter, Isabella. But the plague continued to ravage the capital, and Mathilda – wisely, as it transpired – decided to get her affairs in order. Shortly afterwards she was herself struck down.

John and Mathilda had run a business making religious images and paintings. Mathilda’s will arranged for her apprentice, William, to continue his training with a monk in Bermondsey Priory, and bequeathed to him the tools he needed, together with one of her best chests in which to keep them. A brewery owned by Mathilda was to be sold to pay for prayers for her and John.

That will underlines the devastating impact of the Black Death on thousands of families across the country; indeed, the disease subsequently took Isabella’s guardian. But the document also offers other insights – specifically, into opportunities that resulted from the soaring death toll.

In this instance, Mathilda clearly had wealth of her own, and the freedom to write such a will. She was briefly an early beneficiary of a period of relative economic power for women created by the sudden dearth of skilled and trained men – an era that has been dubbed a ‘golden age’.

Even before the plague afflicted London, the capital’s customary law offered women freedoms that they rarely enjoyed elsewhere in England, except perhaps in York. For example, a woman might enter into obligations on her own behalf, take on apprentices, run her own business, rent property, and sue (or be sued) for debt in the London courts. A woman – especially if she was a widow – could even write a will, as Mathilda de Myms did.

These four mortuary crosses were placed on the body of a plague victim in London c1348. It was in the capital that the Black Death had the greatest impact on women’s lives. © Wellcome Images

But after the plague struck, sending London’s population plummeting to 40,000 from a peak of 80,000 in 1300, these opportunities multiplied. In fact, the mayor and aldermen, alarmed by a chronic shortage of manpower, began actively to encourage women to exercise their new economic rights.

Eventually, the rights went further: from 1465, a widow of a citizen of London, who was living there with him at the time of his death, would be made ‘free of the city’ (a citizen) as long as she continued to live in London and did not remarry.

City authorities were especially anxious to encourage the widows of London merchants and craftsmen to continue to run their husbands’ workshops or trading enterprises, to ensure that these businesses continued to contribute to civic prosperity and taxation. Thus it became compulsory for widows to train their late husbands’ apprentices, or to make proper provision for them.

In the years following the Black Death, girl apprentices became prominent in surviving records. Though this wasn’t a new phenomenon – as early as 1276, Marion de Lymeseye was apprenticed to Roger Oriel, a paternosterer (maker of rosaries) – but in the half-century after the Black Death, from 1350 to 1400, numbers of female apprentices soared.

Fathers sometimes specified in their wills that their daughters should be apprenticed to learn a trade. Robert de Ramseye, a fishmonger who died in 1373, left 20 shillings to his daughter, Elizabeth – for her marriage, and for “putting her to a trade”.

Records are sparse – only 30 apprenticeship indentures from medieval London survive – but about a third of them relate to girls, many training in the craft of silkwork or embroidery. Their indentures, like those of boys, had to be recorded in the apprentice rolls kept at the Guildhall, and the terms of the indentures were the same, usually for seven years.

Why the rise in female apprentices at this time? For boys, a completed apprenticeship opened the way to the citizenship of London, with all its attendant political and economic advantages and responsibilities. For girls, though, this was not the case – citizenship did not follow an apprenticeship, and most went on to marry.

What was life like for a medieval housewife? A female apprentice lived in the household of her master or mistress (not always the case with servants), and was placed almost completely under their authority. The master or mistress had specific obligations to feed, clothe and nurture the apprentice and, above all, to train her in the secrets and skills of her craft. An apprenticeship provided girls with patrons and business contacts, and secured their status within the working community.

So parents from gentry families outside London knew that apprenticing daughters would provide them with the means to earn a living, and to run an independent household should that prove necessary. Unsurprisingly, then, most girls were bound by their father or brother, though one woman from Sussex bound herself as an apprentice to another woman in London.

Sole tradersMarried women in London could choose to trade separately from their husbands as femmes soles. At the time when her husband, Thomas, was serving as an alderman, around 1380, Maud Ireland traded as a femme sole silkwoman. “According to the usage of the city [she was] bound to answer her own contracts,” and she was sued for a debt owed for white silk bought from an Italian merchant.

Women were expected to make a public declaration of their sole status. In October 1457, Agnes Gower stated to the mayor and aldermen that she practised the art of a silkwoman and no other, and asked to be allowed to “merchandise” without her husband John, and to answer sole for her own contracts according to city custom. This was granted and recorded.

Some of these independent London women were doing business on a large scale. Agnes Ramsey, daughter of the noted architect and mason William Ramsey, ran her father’s business after his death in 1349. Mathilda Penne ran her husband’s business as a skinner for 12 years after his death; she trained her own apprentices and employed male servants and, possibly, a female scrivener to keep the accounts.

Twice during the 15th century, the substantial bell foundry outside Aldgate was run by widows. The household and workshop of the bell-founder Johanna Hill, who died in 1441, comprised four male apprentices, two female servants, 10 male servants, a specialised bell-maker, a clerk and the daughter of a fellow bell-founder.

Other widows continued to run the financial side of their husbands’ businesses, if not the trading or craft aspects; they pursued debtors, sorted out accounts and saw to the execution of their husbands’ wills. These women were active in maintaining their households, bolstering the welfare of their souls and managing the upbringing of their children, as well as other endeavours. Another Agnes, the widow of Stephen Forster (mayor of London 1454–55), saw to the rebuilding and reorganisation of the prison at Ludgate.

Crafty womenThese were remarkable women who made their mark in the commercial world of London and won respect within their social milieus. The records of the craft guilds and companies acknowledge the presence of women, but their role was not a formal one – rather, they shared in the religious, charitable and social aspects of company life.

Women are shown weaving in a late-medieval illustration. Women were involved in a wide range of crafts in London at this time. © Bridgeman Art Library

However, several crafts and trades recognised the contribution of women workers. In the early 15th century, for example, one-third of all brewers paying dues to the Brewers’ Company were women. Some of these were single, while others were widows or married women trading sole; one Agnes, whose husband Stephen was a draper, paid her dues independently throughout the 1420s.

Though women were seemingly marginalised within these organisations, limited to social and charitable roles, they were able to make contacts with other workers within their craft. They could also achieve recognition of their credit-worthiness and could share in, and contribute to, the material resources of their societies. To offset the imposed limitations of their role within guilds and companies, and to supplement the formal craft relationships, many created important informal networks of friends, servants, apprentices, dependants and patrons.

A female sculptor at work is illustrated in a late 15th-century painting. © BNF

However enmeshed women may have been in the social and economic networks of London life, their professional advancement was still constrained. For example, there is scant evidence of a woman holding any public office in which she might have been placed in authority over a man – such appointments would be vigorously resisted.

In 1422, the men of Queenhythe ward complained that John of Ely, the local measurer of oysters, had subcontracted his office to women “who know not how to do it; nor is it worship to this city that women should have such things in governance”. No doubt most Londoners shared the view of the men of Queenhythe; certainly, women never served as ward officers, common councilmen or, of course, aldermen. The delegation of authority to women was extremely rare, but it did happen: for more than 20 years following the death of her husband, Nicholas, in 1433, Alice Holford held the office of bailiff of London Bridge (see 'Golden girls', below).

Future gainsThe century and a half between 1350 and 1500 could reasonably be considered a ‘golden age’ for women in London – but it was short-lived. As the population swelled once more, an acute manpower shortage was replaced by a glut, and women were pushed out of the labour market. In 1570, the Drapers’ Company refused to allow a member to take on a girl apprentice “for that they had not seen the like before”.

Women continued to work after that period, of course, but in largely informal and dependent positions. London merchants were transforming themselves into country gentlemen, and it was no longer suitable for their wives to be seen trading sole. Moreover, Protestantism created a specific role for women – as godly domestic teachers within the household.

Throughout the 15th century, English society remained deeply patriarchal. The opportunities that had been available to women had been purely economic: women had no handles on power and no way of influencing political decisions. So the ‘golden age’ was golden only briefly, and was most apparent in the economic capital, London.

Nonetheless, when given the chance, these women demonstrated their ability to do men’s work. In doing so they set an important precedent, to be followed by women in the two world wars of the last century, which led directly to the greater economic and political emancipation of women today.

Golden girls

These four women exploited the opportunities presented when the plague struck

Agnes Ramsey: Mason

Agnes, who never used her husband’s name, was the daughter of the famous architect and mason William Ramsey, who was killed by the Black Death in 1349. Though married to another mason, Robert Hubard, Agnes continued to run her father’s business, entering into a contract with the dowager Queen Isabella, widow of Edward II, to build her fine tomb at the enormous cost of £100.

Alice Holford: Bailiff

Alice took over the post of bailiff of London Bridge on the death of her husband, Nicholas, in 1433, and continued in office for over 20 years. The bailiff collected the tolls due from boats passing through the bridge, and from carts that crossed it into London. The task was a complicated one – charges varied according to the goods and the person transporting them – and Alice must have had some literacy skills.

Johanna Hill: Bell-founder

On the death of her husband in 1440, Johanna took full charge of their bell-founding business till her own death in 1441. Seven of her bells still exist as far away as Ipswich, Sussex and Devon. Johanna continued to use her husband’s mark – a cross and circle within a shield – but surmounted with a lozenge to indicate that the workshop was now under her authority.

Ellen Langwith: Silkwoman

Ellen, who died in 1481, was a London silkwoman. When her first husband, cutler Philip Waltham, died she was left to train their three female apprentices. She later married a tailor, John Langwith, but continued with her own craft. She was recorded as buying gold thread and raw silk direct from Venetian merchants, and in 1465 supplied saddle decorations and silk banners for the coronation of Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Edward IV. She was courted by both the Cutlers’ and Taylors’ companies.

Caroline Barron is professor emerita at Royal Holloway, University of London, and a specialist in late medieval British history, particularly the history of women.

Published on February 02, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - The Breviarium Alaricianum drafter

February 2

506, The Breviarium Alaricianum or Lex Romana Visigothorum, a collection of Roman law, was drafted at Toulouse under Alaric II, King of the Visigoths

506, The Breviarium Alaricianum or Lex Romana Visigothorum, a collection of Roman law, was drafted at Toulouse under Alaric II, King of the Visigoths

Published on February 02, 2016 02:00

February 1, 2016

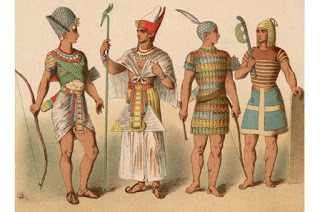

Who was in charge in Ancient Egypt?

History Extra

Who was in charge in Ancient Egypt?The Egyptian king, or pharaoh, was a unique individual. He was the one mortal able to communicate effectively with the gods who protected Egypt from chaos.

Who was in charge in Ancient Egypt?The Egyptian king, or pharaoh, was a unique individual. He was the one mortal able to communicate effectively with the gods who protected Egypt from chaos.

His most important duty was to ensure that Egypt functioned correctly, as this would make the gods content. The king was therefore technically the head of the army, the civil service and the priesthood. However, it would have been impossible for one man to perform all these duties alone. The king therefore appointed deputies – generals, bureaucrats and high priests – to work on his behalf.

These men were drawn from the educated elite, and were often members of the royal family. They, in turn, appointed educated men to work beneath them.

The king was, however, a remote god-like being. Most Egyptians were peasants living in small agricultural communities. The local governor or landowner would probably have been the most important and influential person in their lives.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Life Sciences at the University of Manchester, where she writes and teaches a number of Egyptology courses.

Who was in charge in Ancient Egypt?The Egyptian king, or pharaoh, was a unique individual. He was the one mortal able to communicate effectively with the gods who protected Egypt from chaos.

Who was in charge in Ancient Egypt?The Egyptian king, or pharaoh, was a unique individual. He was the one mortal able to communicate effectively with the gods who protected Egypt from chaos.His most important duty was to ensure that Egypt functioned correctly, as this would make the gods content. The king was therefore technically the head of the army, the civil service and the priesthood. However, it would have been impossible for one man to perform all these duties alone. The king therefore appointed deputies – generals, bureaucrats and high priests – to work on his behalf.

These men were drawn from the educated elite, and were often members of the royal family. They, in turn, appointed educated men to work beneath them.

The king was, however, a remote god-like being. Most Egyptians were peasants living in small agricultural communities. The local governor or landowner would probably have been the most important and influential person in their lives.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Life Sciences at the University of Manchester, where she writes and teaches a number of Egyptology courses.

Published on February 01, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Edward III crowned King of England

February 1

1327 Edward III was crowned King of England, but the country was ruled by his mother Queen Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer.

1327 Edward III was crowned King of England, but the country was ruled by his mother Queen Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer.

Published on February 01, 2016 02:00

January 31, 2016

Where, in Ancient Egypt, did people live?

History Extra

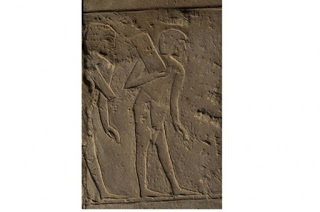

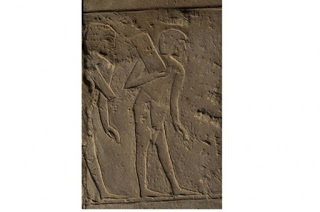

Detail of a relief depicting two male figures carrying bricks. (Photo by Prisma/UIG/Getty Images)

Detail of a relief depicting two male figures carrying bricks. (Photo by Prisma/UIG/Getty Images)

Where, in Ancient Egypt, did people live?The thick mud deposited by the River Nile made an excellent building material. Mud-brick buildings are well suited to hot, dry climates, being cool in summer and warm in winter, so it is not surprising that the Egyptians built their homes and palaces from mud. They saved stone for the temples and the tombs they built in the desert.

Mud bricks were cheap and easily available, so they allowed Egypt's architects to experiment with large-scale structures that could be raised with surprising speed. Several kings founded cities which grew from nothing to fully functional in just seven or eight years. These cities included spacious elite villas with gardens, and more humble terraced housing for workers.

Throughout the Dynastic age the population was concentrated in the area around Thebes (modern Luxor: southern Egypt) and in the area around Memphis (today just to the south of modern Cairo). Today the settlements have almost all vanished – either dissolved into mud or crumbled to dust.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Life Sciences at the University of Manchester, where she writes and teaches a number of Egyptology courses. You can follow her on Twitter @JoyceTyldesley.

Detail of a relief depicting two male figures carrying bricks. (Photo by Prisma/UIG/Getty Images)

Detail of a relief depicting two male figures carrying bricks. (Photo by Prisma/UIG/Getty Images) Where, in Ancient Egypt, did people live?The thick mud deposited by the River Nile made an excellent building material. Mud-brick buildings are well suited to hot, dry climates, being cool in summer and warm in winter, so it is not surprising that the Egyptians built their homes and palaces from mud. They saved stone for the temples and the tombs they built in the desert.

Mud bricks were cheap and easily available, so they allowed Egypt's architects to experiment with large-scale structures that could be raised with surprising speed. Several kings founded cities which grew from nothing to fully functional in just seven or eight years. These cities included spacious elite villas with gardens, and more humble terraced housing for workers.

Throughout the Dynastic age the population was concentrated in the area around Thebes (modern Luxor: southern Egypt) and in the area around Memphis (today just to the south of modern Cairo). Today the settlements have almost all vanished – either dissolved into mud or crumbled to dust.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Life Sciences at the University of Manchester, where she writes and teaches a number of Egyptology courses. You can follow her on Twitter @JoyceTyldesley.

Published on January 31, 2016 03:30