MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 123

January 26, 2016

How did knights in armour go to the toilet?

History Extra

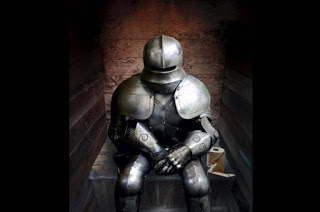

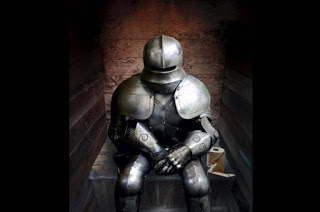

Suits of armour were vital for the battlefield but vexing in the latrine. (Photo by CrackerClips / iStockphoto)

When William the Conqueror invaded in 1066, he wore just a long mail shirt, so answering nature’s call was relatively simple.

It was a very different prospect, however, when Italian and German craftsmen developed full plate armour in the 1400s – which was vital for the battlefield but vexing for a knight in the latrine.

Suits of armour still didn’t have a metal plate covering the knight’s crotch or buttocks as this made riding a horse difficult, but those areas were protected by strong metal skirts flowing out around the front hips (faulds) and buttocks (culet).

Under this dangled a short chainmail shirt to prevent an enemy jabbing anything sharp upwards between the legs. And beneath that, a knight also wore quilted cotton leggings so his limbs wouldn’t chafe. But to stop the steel leg plates sliding down painfully onto the ankles, they had to be held up by a waist belt, or by being attached to the torso plate.

While wearing all that, a knight desperate for the toilet would have most likely needed the assistance of his squire to lift or remove the rear culet, so that he could squat down.

The fact, however, that the leg armour was often suspended tightly from the waist belt, worn over the leggings, might have required it to be detached first before a chivalric chap could comfortably drop his trousers.

This would have been a particular nuisance if the knight was suffering from dysentery, so it was likely that he may have simply chosen to soil himself.

Answered by one of our Q&A experts, Greg Jenner. For more fascinating questions by Greg, and the rest of our panel, pick up a copy of History Revealed! Available in print and for digital devices.

Suits of armour were vital for the battlefield but vexing in the latrine. (Photo by CrackerClips / iStockphoto)

When William the Conqueror invaded in 1066, he wore just a long mail shirt, so answering nature’s call was relatively simple.

It was a very different prospect, however, when Italian and German craftsmen developed full plate armour in the 1400s – which was vital for the battlefield but vexing for a knight in the latrine.

Suits of armour still didn’t have a metal plate covering the knight’s crotch or buttocks as this made riding a horse difficult, but those areas were protected by strong metal skirts flowing out around the front hips (faulds) and buttocks (culet).

Under this dangled a short chainmail shirt to prevent an enemy jabbing anything sharp upwards between the legs. And beneath that, a knight also wore quilted cotton leggings so his limbs wouldn’t chafe. But to stop the steel leg plates sliding down painfully onto the ankles, they had to be held up by a waist belt, or by being attached to the torso plate.

While wearing all that, a knight desperate for the toilet would have most likely needed the assistance of his squire to lift or remove the rear culet, so that he could squat down.

The fact, however, that the leg armour was often suspended tightly from the waist belt, worn over the leggings, might have required it to be detached first before a chivalric chap could comfortably drop his trousers.

This would have been a particular nuisance if the knight was suffering from dysentery, so it was likely that he may have simply chosen to soil himself.

Answered by one of our Q&A experts, Greg Jenner. For more fascinating questions by Greg, and the rest of our panel, pick up a copy of History Revealed! Available in print and for digital devices.

Published on January 26, 2016 03:30

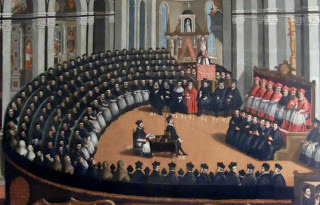

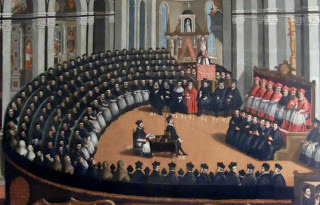

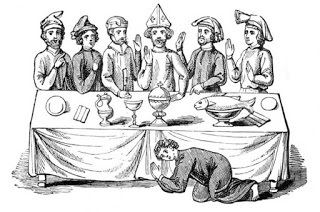

History Trivia - Council of Trent issues the Tridentinum

January 26

1564 The Council of Trent issued its conclusions in the Tridentinum, which established a distinction between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism.

1564 The Council of Trent issued its conclusions in the Tridentinum, which established a distinction between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism.

Published on January 26, 2016 02:00

January 25, 2016

10 things you (probably) didn’t know about the Anglo-Saxons

History Extra

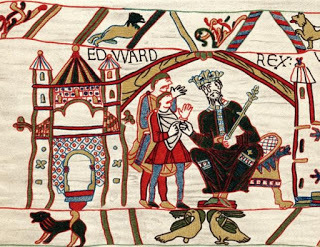

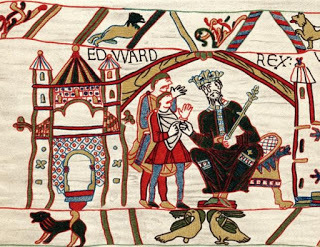

Edward The Confessor, Anglo-Saxon king of England. From the Bayeux Tapestry, which tells the story of the events leading to the 1066 battle of Hastings. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Edward The Confessor, Anglo-Saxon king of England. From the Bayeux Tapestry, which tells the story of the events leading to the 1066 battle of Hastings. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

1) The Anglo-Saxons were immigrantsThe people we call Anglo-Saxons were actually immigrants from northern Germany and southern Scandinavia. Bede, a monk from Northumbria writing some centuries later, says that they were from some of the most powerful and warlike tribes in Germany.

Bede names three of these tribes: the Angles, Saxons and Jutes. There were probably many other peoples who set out for Britain in the early fifth century, however. Batavians, Franks and Frisians are known to have made the sea crossing to the stricken province of ‘Britannia’.

The collapse of the Roman empire was one of the greatest catastrophes in history. Britain, or ‘Britannia’, had never been entirely subdued by the Romans. In the far north – what they called Caledonia (modern Scotland) – there were tribes who defied the Romans, especially the Picts. The Romans built a great barrier, Hadrian’s Wall, to keep them out of the civilised and prosperous part of Britain.

As soon as Roman power began to wane, these defences were degraded, and in AD 367 the Picts smashed through them. Gildas, a British historian, says that Saxon war-bands were hired to defend Britain when the Roman army had left. So the Anglo-Saxons were invited immigrants, according to this theory, a bit like the immigrants from the former colonies of the British empire in the period after 1945.

2) The Anglo-Saxons murdered their hosts at a conferenceBritain was under sustained attack from the Picts in the north and the Irish in the west. The British appointed a ‘head man’, Vortigern, whose name may actually be a title meaning just that – to act as a kind of national dictator.

It is possible that Vortigern was the son-in-law of Magnus Maximus, a usurper emperor who had operated from Britain before the Romans left. Vortigern’s recruitment of the Saxons ended in disaster for Britain. At a conference between the nobles of the Britons and Anglo-Saxons, [likely in AD 472, although some sources say AD 463] the latter suddenly produced concealed knives and stabbed their opposite numbers from Britain in the back.

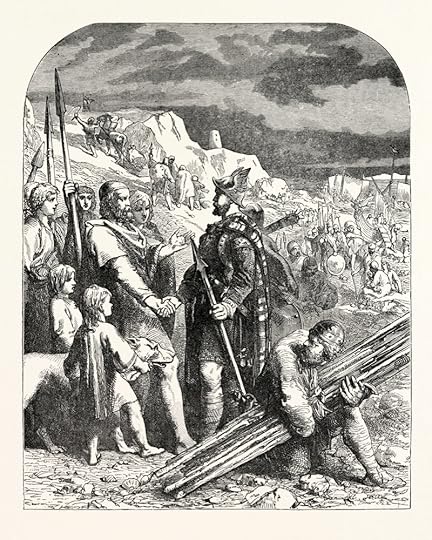

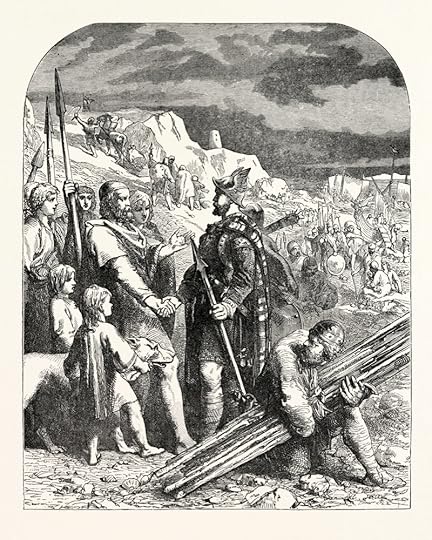

Treaty of Hengist and Horsa with Vortigern. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

Vortigern was deliberately spared in this ‘treachery of the long-knives’, but was forced to cede large parts of south-eastern Britain to them. Vortigern was now a powerless puppet of the Saxons.

3) The Britons rallied under a mysterious leaderThe Angles, Saxons, Jutes and other incomers burst out of their enclave in the south-east in the mid-fifth century and set all southern Britain ablaze. Gildas, our closest witness, says that in this emergency a new British leader emerged, called Ambrosius Aurelianus in the late 440s and early 450s.

It has been postulated that Ambrosius was from the rich villa economy around Gloucestershire, but we simply do not know for sure. Amesbury in Wiltshire is named after him and may have been his campaign headquarters.

A great battle took place, supposedly sometime around AD 500, at a place called Mons Badonicus or Mount Badon, probably somewhere in the south-west of modern England. The Saxons were resoundingly defeated by the Britons, but frustratingly we don’t know much more than that. A later Welsh source says that the victor was ‘Arthur’ but it was written down hundreds of years after the event, when it may have become contaminated by later folk-myths of such a person.

Gildas does not mention Arthur, and this seems strange, but there are many theories about this seeming anomaly. One is that Gildas did refer to him in a sort of acrostic code, which reveals him to be a chieftain from Gwent called Cuneglas. Gildas called Cuneglas ‘the bear’, and Arthur means ‘bear’. Nevertheless, for the time being the Anglo-Saxon advance had been checked by someone, possibly Arthur.

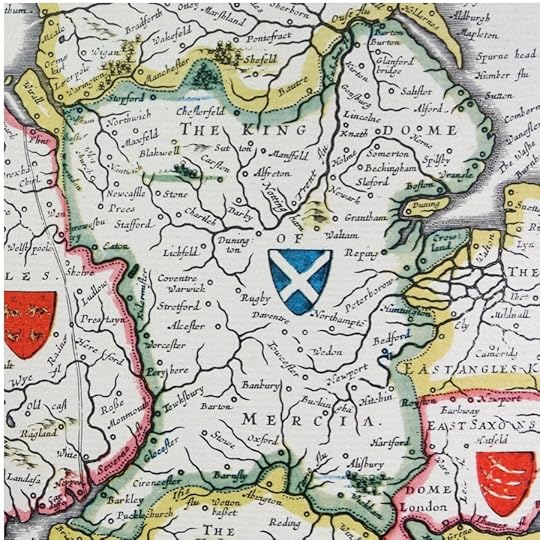

4) Seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms emerged‘England’ as a country did not come into existence for hundreds of years after the Anglo-Saxons arrived. Instead, seven major kingdoms were carved out of the conquered areas: Northumbria, East Anglia, Essex, Sussex, Kent, Wessex and Mercia. All these nations were fiercely independent, and although they shared similar languages, pagan religions, and socio-economic and cultural ties, they were absolutely loyal to their own kings and very competitive, especially in their favourite pastime – war.

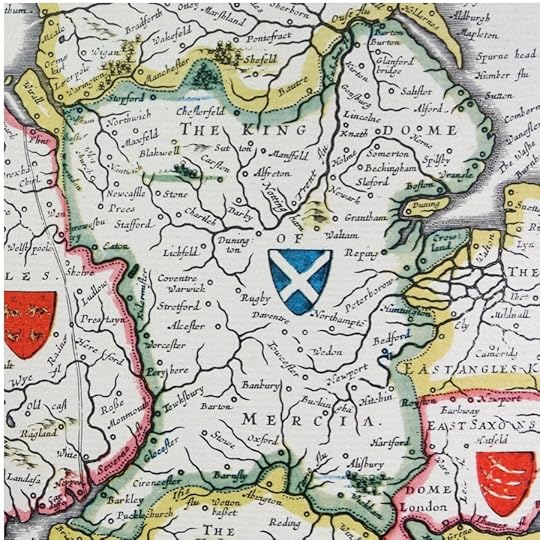

Shield of Mercia, from the Heptarchy; a collective name applied to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of south, east, and central England during late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. Detail from an antique map of Britain by the Dutch cartographer Willem Blaeu in Atlas Novus (Amsterdam, 1635). (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

At first they were pre-occupied fighting the Britons (or ‘Welsh’, as they called them), but as soon as they had consolidated their power-centres they immediately commenced armed conflict with each other.

Woden, one of their chief gods, was especially associated with war, and this military fanaticism was the chief diversion of the kings and nobles. Indeed, tales of the deeds of warriors, or their boasts of what heroics they would perform in battle, was the main form of entertainment, and obsessed the entire community – much like football today.

5) A fearsome warrior plundered his neighboursThe ‘heptarchy’, or seven kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons, all aspired to dominate the others. One reason for this was that the dominant king could exact tribute (a sort of tax, but paid in gold and silver bullion), gemstones, cattle, horses or elite weapons. A money economy did not yet exist.

Eventually a leader from Mercia in the English Midlands became the most feared of all these warrior-kings: Penda, who ruled from AD 626 until 655. He personally killed many of his rivals in battle, and as one of the last pagan Anglo-Saxon kings he offered up the body of one of them, King Oswald of Northumbria, to Woden. Penda ransacked many of the other Anglo-Saxon realms, amassing vast and exquisite treasures as tribute and the discarded war-gear of fallen warriors on the battlefields.

This is just the sort of elite military kit that comprises the Staffordshire Hoard, discovered in 2009. Although a definite connection is elusive, the hoard typifies the warlike atmosphere of the mid-seventh century, and the unique importance in Anglo-Saxon society of male warrior elites.

6) An African refugee helped reform the English churchThe Britons were Christians, but were now cut off from Rome, but the Anglo-Saxons remained pagan. In AD 597 St Augustine had been sent to Kent by Pope Gregory the Great to convert the Anglo-Saxons. It was a tall order for his tiny mission, but gradually the seven kingdoms did convert, and became exemplary Christians – so much so that they converted their old tribal homelands in Germany.

St Augustine of Canterbury, who was sent by Pope Gregory to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. St Augustine is seen here preaching before Ethelbert, Anglo-Saxon King of Kent. Augustine was the first Archbishop of Canterbury. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

One reason why they converted was because the church said that the Christian God would deliver them victory in battles. When this failed to materialise, some Anglo-Saxon kings became apostate, and a different approach was required. The man chosen for the task was an elderly Greek named Theodore of Tarsus, but he was not the pope’s first choice. Instead he had offered the job to a younger man, Hadrian ‘the African’, a Berber refugee from north Africa, but Hadrian objected that he was too young.

The truth was that people in the civilised south of Europe dreaded the idea of going to England, which was considered barbaric and had a terrible reputation. The pope decided to send both men, to keep each other company on the long journey. After more than a year (and many adventures) they arrived, and set to work to reform the English church.

Theodore lived to be 88, a grand old age for those days, and Hadrian, the young man who had fled from his home in north Africa, outlived him, and continued to devote himself to his task until his death in AD 710.

7) Alfred the Great had a crippling disability When we look up at the statue of King Alfred of Wessex in Winchester, we are confronted by an image of our national ‘superhero’: the valiant defender of a Christian realm against the heathen Viking marauders. There is no doubt that Alfred fully deserves this accolade as ‘England’s darling’, but there was another side to him that is less well known.

Alfred never expected to be king – he had three older brothers – but when he was four years old on a visit to Rome the pope seemed to have granted him special favour when his father presented him to the pontiff. As he grew up, Alfred was constantly troubled by illness, including irritating and painful piles – a real problem in an age where a prince was constantly in the saddle. Asser, the Welshman who became his biographer, relates that Alfred suffered from another painful, draining malady that is not specified. Some people believe it was Crohn’s Disease, others that it may have been a sexually transmitted disease, or even severe depression.

The truth is we don’t know exactly what Alfred’s mystery ailment was. Whatever it was, it is incredible to think that Alfred’s extraordinary achievements were accomplished in the face of a daily struggle with debilitating and chronic illness.

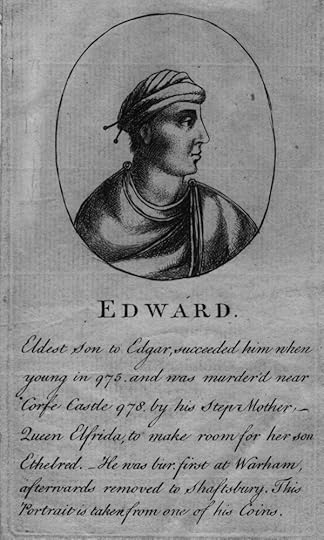

8) An Anglo-Saxon king was finally buried in 1984In July 975 the eldest son of King Edgar, Edward, was crowned king. Edgar had been England’s most powerful king yet (by now the country was unified), and had enjoyed a comparatively peaceful reign. Edward, however, was only 15 and was hot-tempered and ungovernable. He had powerful rivals, including his half-brother Aethelred’s mother, Elfrida (or ‘Aelfthryth’). She wanted her own son to be king – at any cost.

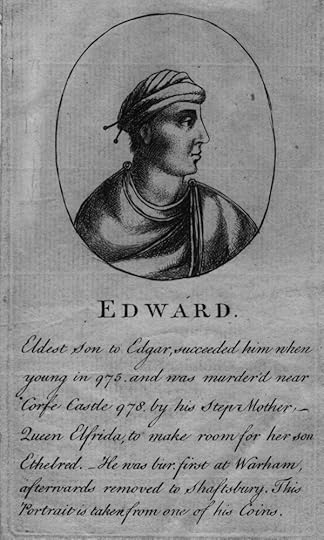

c975 AD, Edward the Martyr, Anglo-Saxon king of England and the elder son of King Edgar. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

One day in 978, Edward decided to pay Elfrida and Aethelred a visit in their residence at Corfe in Dorset. It was too good an opportunity to miss: Elfrida allegedly awaited him at the threshold to the hall with grooms to tend the horses, and proffered him a goblet of mulled wine (or ‘mead’), as was traditional. As Edward stooped to accept this, the grooms grabbed his bridle and stabbed him repeatedly in the stomach.

Edward managed to ride away but bled to death, and was hastily buried by the conspirators. It was foul regicide, the gravest of crimes, and Aethelred, even though he may not have been involved in the plot, was implicated in the minds of the common people, who attributed his subsequent disastrous reign to this, in their eyes, monstrous deed.

Edward’s body was exhumed and reburied at Shaftesbury Abbey in AD 979. During the dissolution of the monasteries the grave was lost, but in 1931 it was rediscovered. Edward’s bones were kept in a bank vault until 1984, when at last he was laid to rest.

9) England was ‘ethnically cleansed’One of the most notorious of Aethelred’s misdeeds was a shameful act of mass-murder. Aethelred is known as ‘the Unready’, but this is actually a pun on his forename. Aethelred means ‘noble counsel’, but people started to call him ‘unraed’ which means ‘no counsel’. He was constantly vacillating, frequently cowardly, and always seemed to pick the worst men possible to advise him.

One of these men, Eadric ‘Streona’ (‘the Aquisitor’), became a notorious English traitor who was to seal England’s downfall. It is a recurring theme in history that powerful men in trouble look for others to take the blame. Aethelred was convinced that the woes of the English kingdom were all the fault of the Danes, who had settled in the country for many generations and who were by now respectable Christian citizens.

On 13 November 1002, secret orders went out from the king to slaughter all Danes, and massacres occurred all over southern England. The north of England was so heavily settled by the Danes that it is probable that it escaped the brutal plot.

One of the Danes killed in this wicked pogrom was the sister of Sweyn Forkbeard, the mighty king of Denmark. From that time on the Danish armies were resolved to conquer England and eliminate Ethelred. Eadric Streona defected to the Danes and fought alongside them in the war of succession that followed Ethelred’s death. This was the beginning of the end for Anglo-Saxon England.

10) Neither William of Normandy or Harold Godwinson were rightful English kingsWe all know something about the 1066 battle of Hastings, but the man who probably should have been king is almost forgotten to history.

Edward ‘the Confessor’, the saintly English king, had died childless in 1066, leaving the English ruling council of leading nobles and spiritual leaders (the Witan) with a big problem. They knew that Edward’s cousin Duke William of Normandy had a powerful claim to the throne, which he would certainly back with armed force.

William was a ruthless and skilled soldier, but the young man who had the best claim to the English throne, Edgar the ‘Aetheling’ (meaning ‘of noble or royal’ status), was only 14 and had no experience of fighting or commanding an army. Edgar was the grandson of Edmund Ironside, a famous English hero, but this would not be enough in these dangerous times.

So Edgar was passed over, and Harold Godwinson, the most famous English soldier of the day, was chosen instead, even though he was not, strictly speaking, ‘royal’. He had gained essential military experience fighting in Wales, however. At first, it seemed as if the Witan had made a sound choice: Harold raised a powerful army and fleet and stood guard in the south all summer long, but then a new threat came in the north.

A huge Viking army landed and destroyed an English army outside York. Harold skilfully marched his army all the way from the south to Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire in a mere five days. He annihilated the Vikings, but a few days later William’s Normans landed in the south. Harold lost no time in marching his army all the way back to meet them in battle, at a ridge of high ground just outside… Hastings.

Martin Wall is the author of The Anglo-Saxon Age: The Birth of England (Amberley Publishing, 2015). In his new book, Martin challenges our notions of the Anglo-Saxon period as barbaric and backward, to reveal a civilisation he argues is as complex, sophisticated and diverse as our own. To find out more, click here.

Edward The Confessor, Anglo-Saxon king of England. From the Bayeux Tapestry, which tells the story of the events leading to the 1066 battle of Hastings. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Edward The Confessor, Anglo-Saxon king of England. From the Bayeux Tapestry, which tells the story of the events leading to the 1066 battle of Hastings. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images) 1) The Anglo-Saxons were immigrantsThe people we call Anglo-Saxons were actually immigrants from northern Germany and southern Scandinavia. Bede, a monk from Northumbria writing some centuries later, says that they were from some of the most powerful and warlike tribes in Germany.

Bede names three of these tribes: the Angles, Saxons and Jutes. There were probably many other peoples who set out for Britain in the early fifth century, however. Batavians, Franks and Frisians are known to have made the sea crossing to the stricken province of ‘Britannia’.

The collapse of the Roman empire was one of the greatest catastrophes in history. Britain, or ‘Britannia’, had never been entirely subdued by the Romans. In the far north – what they called Caledonia (modern Scotland) – there were tribes who defied the Romans, especially the Picts. The Romans built a great barrier, Hadrian’s Wall, to keep them out of the civilised and prosperous part of Britain.

As soon as Roman power began to wane, these defences were degraded, and in AD 367 the Picts smashed through them. Gildas, a British historian, says that Saxon war-bands were hired to defend Britain when the Roman army had left. So the Anglo-Saxons were invited immigrants, according to this theory, a bit like the immigrants from the former colonies of the British empire in the period after 1945.

2) The Anglo-Saxons murdered their hosts at a conferenceBritain was under sustained attack from the Picts in the north and the Irish in the west. The British appointed a ‘head man’, Vortigern, whose name may actually be a title meaning just that – to act as a kind of national dictator.

It is possible that Vortigern was the son-in-law of Magnus Maximus, a usurper emperor who had operated from Britain before the Romans left. Vortigern’s recruitment of the Saxons ended in disaster for Britain. At a conference between the nobles of the Britons and Anglo-Saxons, [likely in AD 472, although some sources say AD 463] the latter suddenly produced concealed knives and stabbed their opposite numbers from Britain in the back.

Treaty of Hengist and Horsa with Vortigern. (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

Vortigern was deliberately spared in this ‘treachery of the long-knives’, but was forced to cede large parts of south-eastern Britain to them. Vortigern was now a powerless puppet of the Saxons.

3) The Britons rallied under a mysterious leaderThe Angles, Saxons, Jutes and other incomers burst out of their enclave in the south-east in the mid-fifth century and set all southern Britain ablaze. Gildas, our closest witness, says that in this emergency a new British leader emerged, called Ambrosius Aurelianus in the late 440s and early 450s.

It has been postulated that Ambrosius was from the rich villa economy around Gloucestershire, but we simply do not know for sure. Amesbury in Wiltshire is named after him and may have been his campaign headquarters.

A great battle took place, supposedly sometime around AD 500, at a place called Mons Badonicus or Mount Badon, probably somewhere in the south-west of modern England. The Saxons were resoundingly defeated by the Britons, but frustratingly we don’t know much more than that. A later Welsh source says that the victor was ‘Arthur’ but it was written down hundreds of years after the event, when it may have become contaminated by later folk-myths of such a person.

Gildas does not mention Arthur, and this seems strange, but there are many theories about this seeming anomaly. One is that Gildas did refer to him in a sort of acrostic code, which reveals him to be a chieftain from Gwent called Cuneglas. Gildas called Cuneglas ‘the bear’, and Arthur means ‘bear’. Nevertheless, for the time being the Anglo-Saxon advance had been checked by someone, possibly Arthur.

4) Seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms emerged‘England’ as a country did not come into existence for hundreds of years after the Anglo-Saxons arrived. Instead, seven major kingdoms were carved out of the conquered areas: Northumbria, East Anglia, Essex, Sussex, Kent, Wessex and Mercia. All these nations were fiercely independent, and although they shared similar languages, pagan religions, and socio-economic and cultural ties, they were absolutely loyal to their own kings and very competitive, especially in their favourite pastime – war.

Shield of Mercia, from the Heptarchy; a collective name applied to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of south, east, and central England during late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. Detail from an antique map of Britain by the Dutch cartographer Willem Blaeu in Atlas Novus (Amsterdam, 1635). (Photo by Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images)

At first they were pre-occupied fighting the Britons (or ‘Welsh’, as they called them), but as soon as they had consolidated their power-centres they immediately commenced armed conflict with each other.

Woden, one of their chief gods, was especially associated with war, and this military fanaticism was the chief diversion of the kings and nobles. Indeed, tales of the deeds of warriors, or their boasts of what heroics they would perform in battle, was the main form of entertainment, and obsessed the entire community – much like football today.

5) A fearsome warrior plundered his neighboursThe ‘heptarchy’, or seven kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons, all aspired to dominate the others. One reason for this was that the dominant king could exact tribute (a sort of tax, but paid in gold and silver bullion), gemstones, cattle, horses or elite weapons. A money economy did not yet exist.

Eventually a leader from Mercia in the English Midlands became the most feared of all these warrior-kings: Penda, who ruled from AD 626 until 655. He personally killed many of his rivals in battle, and as one of the last pagan Anglo-Saxon kings he offered up the body of one of them, King Oswald of Northumbria, to Woden. Penda ransacked many of the other Anglo-Saxon realms, amassing vast and exquisite treasures as tribute and the discarded war-gear of fallen warriors on the battlefields.

This is just the sort of elite military kit that comprises the Staffordshire Hoard, discovered in 2009. Although a definite connection is elusive, the hoard typifies the warlike atmosphere of the mid-seventh century, and the unique importance in Anglo-Saxon society of male warrior elites.

6) An African refugee helped reform the English churchThe Britons were Christians, but were now cut off from Rome, but the Anglo-Saxons remained pagan. In AD 597 St Augustine had been sent to Kent by Pope Gregory the Great to convert the Anglo-Saxons. It was a tall order for his tiny mission, but gradually the seven kingdoms did convert, and became exemplary Christians – so much so that they converted their old tribal homelands in Germany.

St Augustine of Canterbury, who was sent by Pope Gregory to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. St Augustine is seen here preaching before Ethelbert, Anglo-Saxon King of Kent. Augustine was the first Archbishop of Canterbury. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

One reason why they converted was because the church said that the Christian God would deliver them victory in battles. When this failed to materialise, some Anglo-Saxon kings became apostate, and a different approach was required. The man chosen for the task was an elderly Greek named Theodore of Tarsus, but he was not the pope’s first choice. Instead he had offered the job to a younger man, Hadrian ‘the African’, a Berber refugee from north Africa, but Hadrian objected that he was too young.

The truth was that people in the civilised south of Europe dreaded the idea of going to England, which was considered barbaric and had a terrible reputation. The pope decided to send both men, to keep each other company on the long journey. After more than a year (and many adventures) they arrived, and set to work to reform the English church.

Theodore lived to be 88, a grand old age for those days, and Hadrian, the young man who had fled from his home in north Africa, outlived him, and continued to devote himself to his task until his death in AD 710.

7) Alfred the Great had a crippling disability When we look up at the statue of King Alfred of Wessex in Winchester, we are confronted by an image of our national ‘superhero’: the valiant defender of a Christian realm against the heathen Viking marauders. There is no doubt that Alfred fully deserves this accolade as ‘England’s darling’, but there was another side to him that is less well known.

Alfred never expected to be king – he had three older brothers – but when he was four years old on a visit to Rome the pope seemed to have granted him special favour when his father presented him to the pontiff. As he grew up, Alfred was constantly troubled by illness, including irritating and painful piles – a real problem in an age where a prince was constantly in the saddle. Asser, the Welshman who became his biographer, relates that Alfred suffered from another painful, draining malady that is not specified. Some people believe it was Crohn’s Disease, others that it may have been a sexually transmitted disease, or even severe depression.

The truth is we don’t know exactly what Alfred’s mystery ailment was. Whatever it was, it is incredible to think that Alfred’s extraordinary achievements were accomplished in the face of a daily struggle with debilitating and chronic illness.

8) An Anglo-Saxon king was finally buried in 1984In July 975 the eldest son of King Edgar, Edward, was crowned king. Edgar had been England’s most powerful king yet (by now the country was unified), and had enjoyed a comparatively peaceful reign. Edward, however, was only 15 and was hot-tempered and ungovernable. He had powerful rivals, including his half-brother Aethelred’s mother, Elfrida (or ‘Aelfthryth’). She wanted her own son to be king – at any cost.

c975 AD, Edward the Martyr, Anglo-Saxon king of England and the elder son of King Edgar. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

One day in 978, Edward decided to pay Elfrida and Aethelred a visit in their residence at Corfe in Dorset. It was too good an opportunity to miss: Elfrida allegedly awaited him at the threshold to the hall with grooms to tend the horses, and proffered him a goblet of mulled wine (or ‘mead’), as was traditional. As Edward stooped to accept this, the grooms grabbed his bridle and stabbed him repeatedly in the stomach.

Edward managed to ride away but bled to death, and was hastily buried by the conspirators. It was foul regicide, the gravest of crimes, and Aethelred, even though he may not have been involved in the plot, was implicated in the minds of the common people, who attributed his subsequent disastrous reign to this, in their eyes, monstrous deed.

Edward’s body was exhumed and reburied at Shaftesbury Abbey in AD 979. During the dissolution of the monasteries the grave was lost, but in 1931 it was rediscovered. Edward’s bones were kept in a bank vault until 1984, when at last he was laid to rest.

9) England was ‘ethnically cleansed’One of the most notorious of Aethelred’s misdeeds was a shameful act of mass-murder. Aethelred is known as ‘the Unready’, but this is actually a pun on his forename. Aethelred means ‘noble counsel’, but people started to call him ‘unraed’ which means ‘no counsel’. He was constantly vacillating, frequently cowardly, and always seemed to pick the worst men possible to advise him.

One of these men, Eadric ‘Streona’ (‘the Aquisitor’), became a notorious English traitor who was to seal England’s downfall. It is a recurring theme in history that powerful men in trouble look for others to take the blame. Aethelred was convinced that the woes of the English kingdom were all the fault of the Danes, who had settled in the country for many generations and who were by now respectable Christian citizens.

On 13 November 1002, secret orders went out from the king to slaughter all Danes, and massacres occurred all over southern England. The north of England was so heavily settled by the Danes that it is probable that it escaped the brutal plot.

One of the Danes killed in this wicked pogrom was the sister of Sweyn Forkbeard, the mighty king of Denmark. From that time on the Danish armies were resolved to conquer England and eliminate Ethelred. Eadric Streona defected to the Danes and fought alongside them in the war of succession that followed Ethelred’s death. This was the beginning of the end for Anglo-Saxon England.

10) Neither William of Normandy or Harold Godwinson were rightful English kingsWe all know something about the 1066 battle of Hastings, but the man who probably should have been king is almost forgotten to history.

Edward ‘the Confessor’, the saintly English king, had died childless in 1066, leaving the English ruling council of leading nobles and spiritual leaders (the Witan) with a big problem. They knew that Edward’s cousin Duke William of Normandy had a powerful claim to the throne, which he would certainly back with armed force.

William was a ruthless and skilled soldier, but the young man who had the best claim to the English throne, Edgar the ‘Aetheling’ (meaning ‘of noble or royal’ status), was only 14 and had no experience of fighting or commanding an army. Edgar was the grandson of Edmund Ironside, a famous English hero, but this would not be enough in these dangerous times.

So Edgar was passed over, and Harold Godwinson, the most famous English soldier of the day, was chosen instead, even though he was not, strictly speaking, ‘royal’. He had gained essential military experience fighting in Wales, however. At first, it seemed as if the Witan had made a sound choice: Harold raised a powerful army and fleet and stood guard in the south all summer long, but then a new threat came in the north.

A huge Viking army landed and destroyed an English army outside York. Harold skilfully marched his army all the way from the south to Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire in a mere five days. He annihilated the Vikings, but a few days later William’s Normans landed in the south. Harold lost no time in marching his army all the way back to meet them in battle, at a ridge of high ground just outside… Hastings.

Martin Wall is the author of The Anglo-Saxon Age: The Birth of England (Amberley Publishing, 2015). In his new book, Martin challenges our notions of the Anglo-Saxon period as barbaric and backward, to reveal a civilisation he argues is as complex, sophisticated and diverse as our own. To find out more, click here.

Published on January 25, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Henry VIII marries Anne Boleyn

Published on January 25, 2016 02:00

January 24, 2016

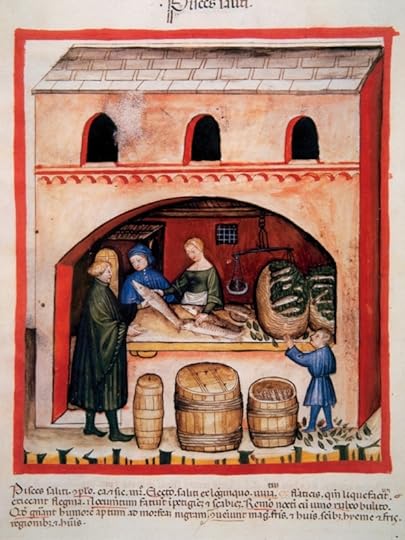

Medieval kebabs and pasties: 5 foods you (probably) didn’t know were being eaten in the Middle Ages

History Extra

Here, freelance writer George Dobbs reveals five examples of commonplace courtly dishes that wouldn't look too out of place on your dinner table today.

Here, freelance writer George Dobbs reveals five examples of commonplace courtly dishes that wouldn't look too out of place on your dinner table today.Sweet and sourSweet and sour rabbit is one of the more curious dishes included in Maggie Black's The Medieval Cookbook. Found in a collection of 14th-century manuscripts called the Curye on Inglish, it includes sugar, red wine vinegar, currants, onions, ginger and cinnamon (along with plenty of “powdour of peper”) to produce a sticky sauce with more than a hint of the modern Chinese takeaway.

The recipe probably dates as far back as the Norman Conquest, when the most surprising ingredient for Saxons would have been rabbit, only recently introduced to England from continental Europe.

PastaIn the same manuscript we find instructions for pasta production, with fine flour used to “make therof thynne foyles as paper with a roller, drye it hard and seeth it in broth”. This was known as 'losyns', and a typical dish involved layering the pasta with cheese sauce to make another English favourite: lasagne.

Sadly the lack of tomatoes meant there was no rich bolognese to go along with the béchamel, but it was still a much-loved dish, and was served at the end of meals to help soak up the large amount of alcohol you were expected to imbibe – much as an oily kebab might today.

In Thomas Austin's edition of Two Fifteenth Century Cookery Books, you can find several other pasta recipes, including ravioli and Lesenge Fries – a sugar and saffron doughnut, similar to the modern Italian feast day treats such as frappe or castagnole. The full edition, including hundreds of medieval recipes, can be found online through the University of Michigan database.

Rice dishesRice was grown in Europe as early as the 8th century by Spanish Moors. By the 15th century it was produced across Spain and Italy, and exported to all corners of Europe in vast quantities. The brilliant recipe resource www.medievalcookery.com shows the wide variety of ways in which rice was used, including three separate medieval references to a dish called blancmager.

Rather than the pudding you might expect, blancmager was actually a soft rice dish, combining chicken or fish with sugar and spices. Due to its bland nature, it was possibly served to invalids as a restorative.

There were also sweet rice dishes, including rice drinks and a dish called prymerose, which combined honey, almonds, primroses and rice flour to make a thick rice pudding.

PastiesWrapping food in pastry was commonplace in medieval times. It meant that meat could be baked in stone ovens without being burnt or tarnished by soot, while also forming a rich, thick gravy.

PastiesWrapping food in pastry was commonplace in medieval times. It meant that meat could be baked in stone ovens without being burnt or tarnished by soot, while also forming a rich, thick gravy.Pie crusts were elaborately decorated to show off the status of the host, and diners would often discard it to get to the filling. However, there were also pastry dishes intended to be eaten as a whole. In The Goodman of Paris, translated into English by Eileen Power, we find a recipe for cheese and mushroom pasties, and we're even given instruction on how to pick our ingredients, with “mushrooms of one night... small, red inside and closed at the top” being the most suitable.

CandySubtleties are a famous medieval culinary feature. The term actually encompasses the notion of entertainment with food as well as elaborate savoury dishes, but it's most often used to refer to lavish constructions of almond and sugar that were served at the end of the meal.

These weren't the only way to indulge a sweet tooth, however. Maggie Black describes a recipe in the Curye on Inglish that combines pine nuts with sugar, honey and breadcrumbs to give a chewy candy. And long before it was a health food, almond milk was a commonplace drink at medieval tables.

So what have we learned? From just a few examples it's easy to see that, despite technological restrictions, cookery of this period wasn't necessarily unskilled or unpalatable. It's true that a cursory glance over recipe collections reveals odd dishes such as gruel and compost, which look about as appetising as their names suggest. But for every grim oddity there were many more meals that still sound mouthwatering today. In fact, many of our modern favourites may have roots in medieval kitchens.

George Dobbs is a freelance writer who specialises in literature and history.

Published on January 24, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Caligula murdered

January 24

41 Caligula was murdered along with his wife and infant child by a Praetorian tribune while attending the Palatine games. Claudius succeeded his nephew.

41 Caligula was murdered along with his wife and infant child by a Praetorian tribune while attending the Palatine games. Claudius succeeded his nephew.

Published on January 24, 2016 01:30

January 23, 2016

11 things you (probably) didn’t know about Sherlock Holmes

History Extra

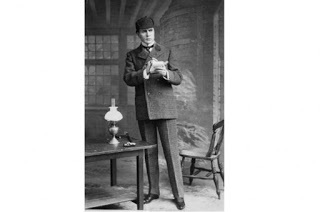

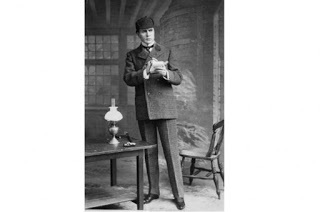

Actor William Gillette playing the detective Sherlock Holmes, 1899. (Photo by Gillette/London Stereoscopic Company/Getty Images)

Actor William Gillette playing the detective Sherlock Holmes, 1899. (Photo by Gillette/London Stereoscopic Company/Getty Images)

In A Holmes & Hudson Mystery: Mrs Hudson and the Spirits’ Curse, Martin Davies reimagines the activities of Baker Street’s best-known residents to bring a fresh twist to the classic Victorian mystery.

Here, writing for History Extra, Davies shares 11 things you (probably) didn’t know about Sherlock Holmes…

Since Sherlock Holmes’ creation, dozens of actors have attempted to portray the great detective – on stage, on radio, in films and on television. But their efforts to breathe new life into this enigmatic character might well have been greeted with bemusement by Holmes’ creator, who wrote in a letter in 1892: “Holmes is as inhuman as Babbage’s Calculating Machine.” Did you know…

1) The first actor to take on the role of Sherlock Holmes in any official capacity was the American William Gillette, whose 1899 stage play was adapted from a script by Conan Doyle himself. Opening six years after the author had attempted to kill off his creation at the Reichenbach Falls, the play was a huge success on both sides of the Atlantic: between 1899 and 1932, Gillette performed the role more than 1,000 times.

Gillette is also credited with introducing the curved briar pipe that was to become synonymous with the great detective – possibly because a straight pipe obscured the actor’s face when he delivered his lines. On first meeting Sherlock Holmes’ creator, Gillette is said to have appeared in character, complete with deerstalker, and after examining Conan Doyle most minutely, to have opined: “Unquestionably an author!”

2) Gillette was also one of the first to annoy the purists by introducing a love interest for Holmes. When he telegraphed Conan Doyle with the question “May I marry him?” the author is said to have replied: “You may marry him, or murder or do what you like with him!” It’s impossible to count the number of writers who, since then, have taken Doyle at his word.

3) Holmes, having survived the Reichenbach Falls, refused to die with his creator. By the time of Conan Doyle’s death [7 July 1930], Holmes was already a star of stage and screen. His film debut, Sherlock Holmes Baffled, came as early as 1900. Just a few seconds long, the film used stop-motion camerawork to show Holmes attempting to grapple with a burglar who repeatedly disappears, then reappears in a different part of the room.

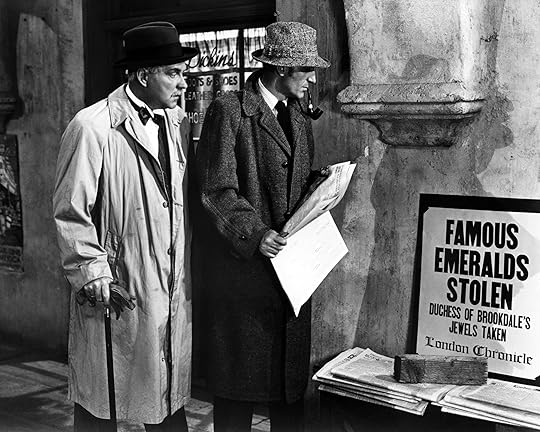

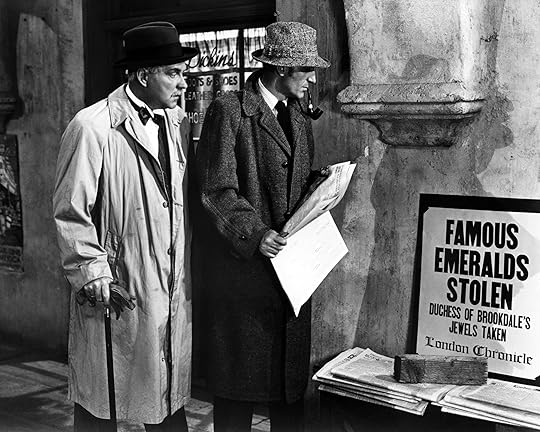

4) One of the oldest surviving film adaptations of Conan Doyle’s work dates to 1916 (William Gillette again), but it was the English duo of Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce in the 1940s who for many years became identified in the public imagination as the Holmes and Watson.

British actors Nigel Bruce (left) as Dr Watson and Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes in 'Pursuit to Algiers', 1945. (Photo by Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images)

Rathbone and Bruce made 14 Sherlock Holmes films between 1939 and 1946 (and starred in more than 200 dramatisations for American radio), yet only the first two films were set in the Victorian period. The others had a contemporary setting, allowing Sherlock Holmes to pursue Nazi spies and to urge the purchase of war bonds. Bruce’s dim, bumbling Watson tends to infuriate Holmes purists.

5) The Adventures of ChubbLock Homes, an early comic strip, appeared in Comic Cuts magazine as early as 1893, and the urge to parody the great detective has never gone away. In 1901, while William Gillette’s official Holmes play was running in London, audiences at Terry’s Theatre were enjoying performances of the rather more frivolous Sheerluck Jones. The comic strip Sherlocko & Watso was hugely popular in the USA in the early 20th century, and silent film parodies abounded. Later in the century, Peter Cook and John Cleese both played comedy Sherlocks on film (Cleese's character was Arthur Sherlock Holmes, Sherlock’s grandson).

Less well remembered, perhaps, is the 1976 TV film The Return of the World’s Greatest Detective, in which a youthful Larry Hagman (before his JR Ewing days) played a deluded motorcycle cop, Sherman Holmes.

6) Even in his early days, Sherlock Holmes was helping manufacturers to sell their products. In the 1890s, the makers of Beecham’s Pills ran advertisements suggesting that the great detective was a devoted user. And as a smoker, Holmes was popular with the tobacco companies. Early cigarette advertisements using Holmes’ image included brands such as Lambert and Butler’s ‘Varsity’ mixture, Chesterfield, Ogden’s, Gallaher’s and Players. Since then, products as diverse as furniture cream, mouthwash, breakfast cereal and photocopiers have all benefited from association with the great man.

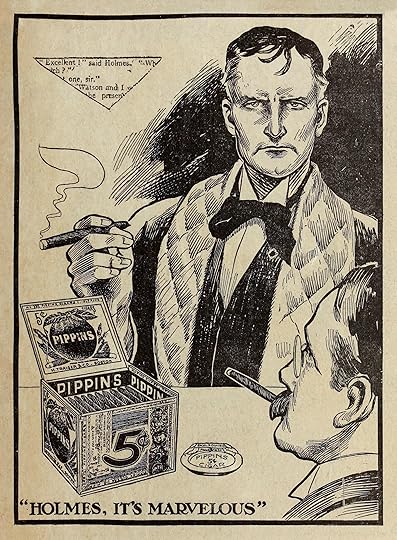

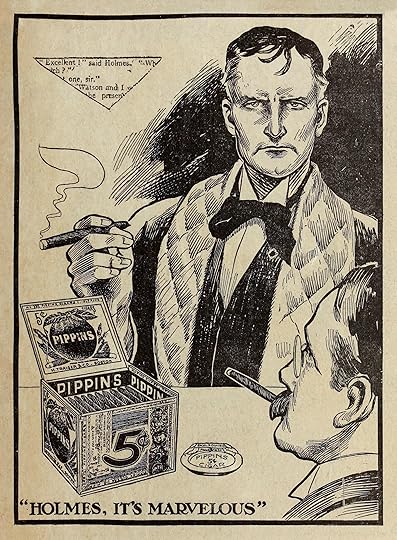

"Holmes, it's Marvelous" Pippins Cigar print advert featuring Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson. From a series of booklets distributed with The Boston Sunday Post in 1911. Sherlock is drawn to resemble actor William Gillette. (© Contraband Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

7) With the growth of television after the Second World War, the Baker Street detective was quick to adapt to the new medium. Alan Wheatley was the first actor to portray Holmes on British television – his 1951 series was broadcast live. But it seems Wheatley was not a fan of Holmes. When asked about Holmes’ character, he is said to have replied: “In my opinion he just seemed to be an insufferable prig”.

8) Peter Cushing appeared as Holmes on the BBC in the 1960s. He had already played the detective in the 1959 Hammer film The Hound of the Baskervilles, alongside Christopher Lee as Sir Henry Baskerville. Lee was to play Holmes himself in a 1962 film; then, nearly 30 years later, he took up the pipe again, playing an ageing Sherlock in two TV films known together as Sherlock Holmes the Golden Years. Throw in an appearance as Mycroft Holmes in Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, and Sir Christopher almost bagged the complete set. Alas, he never appeared on screen as Doctor Watson.

[image error]

English actor Peter Cushing as fictional detective Sherlock Holmes with Andre Morell as Dr Watson in a scene from 'The Hound of the Baskervilles', 1959. (Photo by Express Newspapers/Getty Images)

9) For many people, the definitive portrayal of Sherlock Holmes was by Jeremy Brett, for Granada Television, in the 1980s and 1990s. Brett appeared in 41 episodes, including five feature-length productions. However, even that impressive achievement doesn’t make Brett the most prolific Holmes. That title must go to the British actor Clive Merrison, who played the detective on BBC Radio between 1989 and 1998, and who completed the full canon – dramatisations of all 60 of Conan Doyle’s Holmes stories and novels.

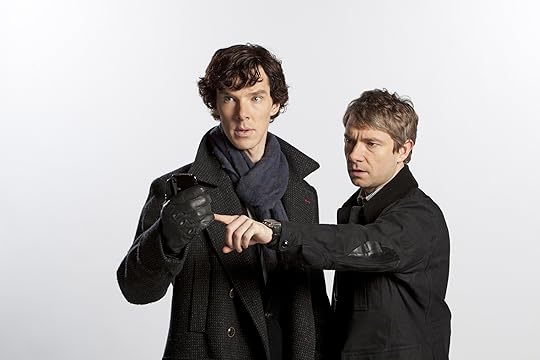

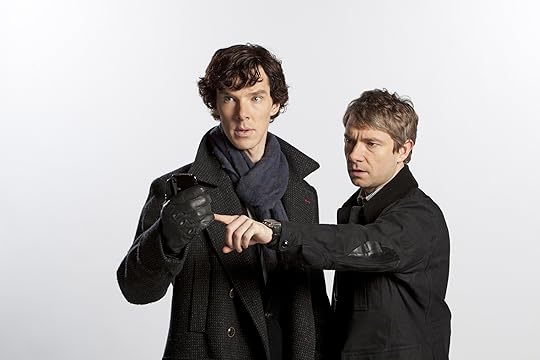

10) And so to Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock, in which Andrew Scott rose to prominence playing Moriarty. Scott has since appeared in the new James Bond film, Spectre, joining an illustrious club of actors who have performed alongside Britain’s most famous spy and Britain’s most famous detective.

But only Sir Roger Moore has played both leading roles on film. Sadly his one appearance as Holmes – in the 1976 TV-film Sherlock Holmes in New York – is not, perhaps, his most memorable work. Sean Connery never played Holmes, but he did play the ultra-astute friar William of Baskerville in The Name of the Rose, so you might say that he came close.

Benedict Cumberbatch as Sherlock (season 1). © Photos 12/Alamy Stock Photo

11) The actor playing Dr Watson to Roger Moore’s Holmes was Patrick Macnee, most famous as John Steed in The Avengers. Macnee played Watson again, 15 years later, alongside Christopher Lee’s Holmes. Then, in 1993, he donned the deerstalker himself in The Hound of London, thus becoming that very rare thing – an actor who has starred in films as both Holmes and Watson.

Martin Davies’ Mrs Hudson and the Spirits’ Curse is published by Canelo. To find out more, click here.

Actor William Gillette playing the detective Sherlock Holmes, 1899. (Photo by Gillette/London Stereoscopic Company/Getty Images)

Actor William Gillette playing the detective Sherlock Holmes, 1899. (Photo by Gillette/London Stereoscopic Company/Getty Images) In A Holmes & Hudson Mystery: Mrs Hudson and the Spirits’ Curse, Martin Davies reimagines the activities of Baker Street’s best-known residents to bring a fresh twist to the classic Victorian mystery.

Here, writing for History Extra, Davies shares 11 things you (probably) didn’t know about Sherlock Holmes…

Since Sherlock Holmes’ creation, dozens of actors have attempted to portray the great detective – on stage, on radio, in films and on television. But their efforts to breathe new life into this enigmatic character might well have been greeted with bemusement by Holmes’ creator, who wrote in a letter in 1892: “Holmes is as inhuman as Babbage’s Calculating Machine.” Did you know…

1) The first actor to take on the role of Sherlock Holmes in any official capacity was the American William Gillette, whose 1899 stage play was adapted from a script by Conan Doyle himself. Opening six years after the author had attempted to kill off his creation at the Reichenbach Falls, the play was a huge success on both sides of the Atlantic: between 1899 and 1932, Gillette performed the role more than 1,000 times.

Gillette is also credited with introducing the curved briar pipe that was to become synonymous with the great detective – possibly because a straight pipe obscured the actor’s face when he delivered his lines. On first meeting Sherlock Holmes’ creator, Gillette is said to have appeared in character, complete with deerstalker, and after examining Conan Doyle most minutely, to have opined: “Unquestionably an author!”

2) Gillette was also one of the first to annoy the purists by introducing a love interest for Holmes. When he telegraphed Conan Doyle with the question “May I marry him?” the author is said to have replied: “You may marry him, or murder or do what you like with him!” It’s impossible to count the number of writers who, since then, have taken Doyle at his word.

3) Holmes, having survived the Reichenbach Falls, refused to die with his creator. By the time of Conan Doyle’s death [7 July 1930], Holmes was already a star of stage and screen. His film debut, Sherlock Holmes Baffled, came as early as 1900. Just a few seconds long, the film used stop-motion camerawork to show Holmes attempting to grapple with a burglar who repeatedly disappears, then reappears in a different part of the room.

4) One of the oldest surviving film adaptations of Conan Doyle’s work dates to 1916 (William Gillette again), but it was the English duo of Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce in the 1940s who for many years became identified in the public imagination as the Holmes and Watson.

British actors Nigel Bruce (left) as Dr Watson and Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes in 'Pursuit to Algiers', 1945. (Photo by Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images)

Rathbone and Bruce made 14 Sherlock Holmes films between 1939 and 1946 (and starred in more than 200 dramatisations for American radio), yet only the first two films were set in the Victorian period. The others had a contemporary setting, allowing Sherlock Holmes to pursue Nazi spies and to urge the purchase of war bonds. Bruce’s dim, bumbling Watson tends to infuriate Holmes purists.

5) The Adventures of ChubbLock Homes, an early comic strip, appeared in Comic Cuts magazine as early as 1893, and the urge to parody the great detective has never gone away. In 1901, while William Gillette’s official Holmes play was running in London, audiences at Terry’s Theatre were enjoying performances of the rather more frivolous Sheerluck Jones. The comic strip Sherlocko & Watso was hugely popular in the USA in the early 20th century, and silent film parodies abounded. Later in the century, Peter Cook and John Cleese both played comedy Sherlocks on film (Cleese's character was Arthur Sherlock Holmes, Sherlock’s grandson).

Less well remembered, perhaps, is the 1976 TV film The Return of the World’s Greatest Detective, in which a youthful Larry Hagman (before his JR Ewing days) played a deluded motorcycle cop, Sherman Holmes.

6) Even in his early days, Sherlock Holmes was helping manufacturers to sell their products. In the 1890s, the makers of Beecham’s Pills ran advertisements suggesting that the great detective was a devoted user. And as a smoker, Holmes was popular with the tobacco companies. Early cigarette advertisements using Holmes’ image included brands such as Lambert and Butler’s ‘Varsity’ mixture, Chesterfield, Ogden’s, Gallaher’s and Players. Since then, products as diverse as furniture cream, mouthwash, breakfast cereal and photocopiers have all benefited from association with the great man.

"Holmes, it's Marvelous" Pippins Cigar print advert featuring Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson. From a series of booklets distributed with The Boston Sunday Post in 1911. Sherlock is drawn to resemble actor William Gillette. (© Contraband Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

7) With the growth of television after the Second World War, the Baker Street detective was quick to adapt to the new medium. Alan Wheatley was the first actor to portray Holmes on British television – his 1951 series was broadcast live. But it seems Wheatley was not a fan of Holmes. When asked about Holmes’ character, he is said to have replied: “In my opinion he just seemed to be an insufferable prig”.

8) Peter Cushing appeared as Holmes on the BBC in the 1960s. He had already played the detective in the 1959 Hammer film The Hound of the Baskervilles, alongside Christopher Lee as Sir Henry Baskerville. Lee was to play Holmes himself in a 1962 film; then, nearly 30 years later, he took up the pipe again, playing an ageing Sherlock in two TV films known together as Sherlock Holmes the Golden Years. Throw in an appearance as Mycroft Holmes in Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, and Sir Christopher almost bagged the complete set. Alas, he never appeared on screen as Doctor Watson.

[image error]

English actor Peter Cushing as fictional detective Sherlock Holmes with Andre Morell as Dr Watson in a scene from 'The Hound of the Baskervilles', 1959. (Photo by Express Newspapers/Getty Images)

9) For many people, the definitive portrayal of Sherlock Holmes was by Jeremy Brett, for Granada Television, in the 1980s and 1990s. Brett appeared in 41 episodes, including five feature-length productions. However, even that impressive achievement doesn’t make Brett the most prolific Holmes. That title must go to the British actor Clive Merrison, who played the detective on BBC Radio between 1989 and 1998, and who completed the full canon – dramatisations of all 60 of Conan Doyle’s Holmes stories and novels.

10) And so to Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock, in which Andrew Scott rose to prominence playing Moriarty. Scott has since appeared in the new James Bond film, Spectre, joining an illustrious club of actors who have performed alongside Britain’s most famous spy and Britain’s most famous detective.

But only Sir Roger Moore has played both leading roles on film. Sadly his one appearance as Holmes – in the 1976 TV-film Sherlock Holmes in New York – is not, perhaps, his most memorable work. Sean Connery never played Holmes, but he did play the ultra-astute friar William of Baskerville in The Name of the Rose, so you might say that he came close.

Benedict Cumberbatch as Sherlock (season 1). © Photos 12/Alamy Stock Photo

11) The actor playing Dr Watson to Roger Moore’s Holmes was Patrick Macnee, most famous as John Steed in The Avengers. Macnee played Watson again, 15 years later, alongside Christopher Lee’s Holmes. Then, in 1993, he donned the deerstalker himself in The Hound of London, thus becoming that very rare thing – an actor who has starred in films as both Holmes and Watson.

Martin Davies’ Mrs Hudson and the Spirits’ Curse is published by Canelo. To find out more, click here.

Published on January 23, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Octavian founds Roman Empire

January 23

7 BC, Augustus Caesar (Octavian) founded the Roman Empire that would last until A.D. 476. Octavian was granted the title 'Augustus', meaning lofty or serene, by the Roman senate.

7 BC, Augustus Caesar (Octavian) founded the Roman Empire that would last until A.D. 476. Octavian was granted the title 'Augustus', meaning lofty or serene, by the Roman senate.

Published on January 23, 2016 02:00

January 22, 2016

List of Medieval Killers found Inscribed on Cathedral Wall may help solve Murder Mystery

Ancient Origins

A group of restorers working inside the Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior in Pereslavl-Zalessky, Russia, have discovered an ancient inscription on one of the walls which details the names of twenty Medieval murderers and conspirators involved in the assassination of the Grand Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal in 1174 AD. The finding helps shed light on one of the great murder mysteries of 12 th century Russia.

A group of restorers working inside the Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior in Pereslavl-Zalessky, Russia, have discovered an ancient inscription on one of the walls which details the names of twenty Medieval murderers and conspirators involved in the assassination of the Grand Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal in 1174 AD. The finding helps shed light on one of the great murder mysteries of 12 th century Russia.

Discovery News reports that the inscription was found on the east wall of the cathedral during restoration work. The text refers to a well-known event in history in which Andrey Bogolyubsky, the Grand Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal and one of the most powerful princes of the time, was murdered.

The inscription is in two columns. The right column reads: “On the month of June 29 Prince Andrey had been killed by his servants. Memory eternal to him and eternal torture to them [lost text].” The left column contains a list of twenty individuals involved in Bogoyubsky’s murder. Three of the people listed are already known to have been involved from historical records. However, the other names were unknown, providing new information about this ancient murder mystery.

The inscription briefly describes the events leading to Bogoybusky’s murder and concludes: “These are murderers of Great Prince Andrey. Let them be cursed.”

Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior in Pereslavl-Zalessky, Russia, where the ancient inscription referring to a well-known murder were found (

public domain

).Andrey Bogolyubsky, Powerful Prince of Vladimir Andrey Bogolyubsky (“Andrew the God-Loving”) was Grand Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal, a major principality that succeeded Kieven Rus, from 1157 until his death in 1174. Bogolyubsky was largely responsible for the rise of Vladimir as the new capital city of Rus and the decline of Kiev’s rule over northeastern Russian lands.

Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior in Pereslavl-Zalessky, Russia, where the ancient inscription referring to a well-known murder were found (

public domain

).Andrey Bogolyubsky, Powerful Prince of Vladimir Andrey Bogolyubsky (“Andrew the God-Loving”) was Grand Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal, a major principality that succeeded Kieven Rus, from 1157 until his death in 1174. Bogolyubsky was largely responsible for the rise of Vladimir as the new capital city of Rus and the decline of Kiev’s rule over northeastern Russian lands.

“Seeing their power strongly reduced, the boyars, or upper nobility, plotted against the autocratic prince,” reports Discovery News.

Grand Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky, by Viktor Vasnetsov (

public domain

)The Murder of a Prince On the night of June 28, 1174, twenty of Bogolyubsky’s disgruntled retainers burst into his bedchamber and stabbed the prince to death.

Grand Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky, by Viktor Vasnetsov (

public domain

)The Murder of a Prince On the night of June 28, 1174, twenty of Bogolyubsky’s disgruntled retainers burst into his bedchamber and stabbed the prince to death.

According to Russiapedia, one of the killers was his wife’s brother, Yakim Kichka, who wanted revenge for the execution of his brother. Indeed, Yakim’s name is listed on the newly discovered inscription. The other two known murderers were Petr Fralovich and Ambal, also on the list, however, the other conspirators were never known until now.

Andrey Bogolyubsky (Murder) by Sergei Kirillov (

russiapedia.rt.com

)Inscription Sheds New Light on Murder “The murder of the prince is one of the most dramatic and mysterious events of the second half of the 12th century,” Nikolai Makarov, director of the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said in a statement [via Discovery News].

Andrey Bogolyubsky (Murder) by Sergei Kirillov (

russiapedia.rt.com

)Inscription Sheds New Light on Murder “The murder of the prince is one of the most dramatic and mysterious events of the second half of the 12th century,” Nikolai Makarov, director of the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said in a statement [via Discovery News].

Now some of this mystery has been resolved with the full list of killers, the number of which corresponds to historical records, now available.

Historians believe the inscription may have been a type of official announcement about the murder of Prince Andrey, possibly sent by the Vladimir authorities to the main cities of the northeastern Russian lands to be inscribed on the walls of churches. If this is the case, there may have been other inscriptions made on cathedral walls.

Featured image: Main: Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior in Pereslavl-Zalessky ( public domain ). Inset: Detail of the left column of an inscription found in a Russian cathedral that names men who murdered a prince. Credit: Discovery News .

By April Holloway

A group of restorers working inside the Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior in Pereslavl-Zalessky, Russia, have discovered an ancient inscription on one of the walls which details the names of twenty Medieval murderers and conspirators involved in the assassination of the Grand Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal in 1174 AD. The finding helps shed light on one of the great murder mysteries of 12 th century Russia.

A group of restorers working inside the Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior in Pereslavl-Zalessky, Russia, have discovered an ancient inscription on one of the walls which details the names of twenty Medieval murderers and conspirators involved in the assassination of the Grand Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal in 1174 AD. The finding helps shed light on one of the great murder mysteries of 12 th century Russia. Discovery News reports that the inscription was found on the east wall of the cathedral during restoration work. The text refers to a well-known event in history in which Andrey Bogolyubsky, the Grand Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal and one of the most powerful princes of the time, was murdered.

The inscription is in two columns. The right column reads: “On the month of June 29 Prince Andrey had been killed by his servants. Memory eternal to him and eternal torture to them [lost text].” The left column contains a list of twenty individuals involved in Bogoyubsky’s murder. Three of the people listed are already known to have been involved from historical records. However, the other names were unknown, providing new information about this ancient murder mystery.

The inscription briefly describes the events leading to Bogoybusky’s murder and concludes: “These are murderers of Great Prince Andrey. Let them be cursed.”

Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior in Pereslavl-Zalessky, Russia, where the ancient inscription referring to a well-known murder were found (

public domain

).Andrey Bogolyubsky, Powerful Prince of Vladimir Andrey Bogolyubsky (“Andrew the God-Loving”) was Grand Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal, a major principality that succeeded Kieven Rus, from 1157 until his death in 1174. Bogolyubsky was largely responsible for the rise of Vladimir as the new capital city of Rus and the decline of Kiev’s rule over northeastern Russian lands.

Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior in Pereslavl-Zalessky, Russia, where the ancient inscription referring to a well-known murder were found (

public domain

).Andrey Bogolyubsky, Powerful Prince of Vladimir Andrey Bogolyubsky (“Andrew the God-Loving”) was Grand Prince of Vladimir-Suzdal, a major principality that succeeded Kieven Rus, from 1157 until his death in 1174. Bogolyubsky was largely responsible for the rise of Vladimir as the new capital city of Rus and the decline of Kiev’s rule over northeastern Russian lands. “Seeing their power strongly reduced, the boyars, or upper nobility, plotted against the autocratic prince,” reports Discovery News.

Grand Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky, by Viktor Vasnetsov (

public domain

)The Murder of a Prince On the night of June 28, 1174, twenty of Bogolyubsky’s disgruntled retainers burst into his bedchamber and stabbed the prince to death.

Grand Prince Andrey Bogolyubsky, by Viktor Vasnetsov (

public domain

)The Murder of a Prince On the night of June 28, 1174, twenty of Bogolyubsky’s disgruntled retainers burst into his bedchamber and stabbed the prince to death. According to Russiapedia, one of the killers was his wife’s brother, Yakim Kichka, who wanted revenge for the execution of his brother. Indeed, Yakim’s name is listed on the newly discovered inscription. The other two known murderers were Petr Fralovich and Ambal, also on the list, however, the other conspirators were never known until now.

“The plotters robbed Andrey Bogolyubsky’s possessions, and Andrey’s body was brought to the church, but fearing the anger of the plotters, the clergy didn’t carry out a requiem mass for Andrey,” reports Russiapedia. “Only on the third day was his body put into a coffin. The city of Vladimir suffered from riots and priest Mikulitsa, who had helped Andrey move the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God to the city, walked around the city with the icon and a miracle happened – the riots stopped. Six days after Andrey’s death, his body and the body of his son Gleb, who was only twenty when he died, were moved to Vladimir from Bogolyubovo. People saw that the bodies of Andrey and his son remained incorruptible. After some time Andrey and his son were consecrated saints and their incorruptible relics are said to cure many people.”

Andrey Bogolyubsky (Murder) by Sergei Kirillov (

russiapedia.rt.com

)Inscription Sheds New Light on Murder “The murder of the prince is one of the most dramatic and mysterious events of the second half of the 12th century,” Nikolai Makarov, director of the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said in a statement [via Discovery News].

Andrey Bogolyubsky (Murder) by Sergei Kirillov (

russiapedia.rt.com

)Inscription Sheds New Light on Murder “The murder of the prince is one of the most dramatic and mysterious events of the second half of the 12th century,” Nikolai Makarov, director of the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, said in a statement [via Discovery News]. Now some of this mystery has been resolved with the full list of killers, the number of which corresponds to historical records, now available.

Historians believe the inscription may have been a type of official announcement about the murder of Prince Andrey, possibly sent by the Vladimir authorities to the main cities of the northeastern Russian lands to be inscribed on the walls of churches. If this is the case, there may have been other inscriptions made on cathedral walls.

Featured image: Main: Cathedral of the Transfiguration of the Savior in Pereslavl-Zalessky ( public domain ). Inset: Detail of the left column of an inscription found in a Russian cathedral that names men who murdered a prince. Credit: Discovery News .

By April Holloway

Published on January 22, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Battle at Basing - Danish Vikings victorious

Published on January 22, 2016 01:30