MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 126

January 7, 2016

History Trivia - University of Glasgow founded

January 7

1451 the University of Glasgow founded at the request of King James II of Scotland. Pope Nicholas V issued a bull of foundation for a studium generale. At first underfunded and lacking a place to hold lectures, the University nonetheless grew into a distinguished center of learning, its progress only briefly interrupted by the troubles of the Reformation.

1451 the University of Glasgow founded at the request of King James II of Scotland. Pope Nicholas V issued a bull of foundation for a studium generale. At first underfunded and lacking a place to hold lectures, the University nonetheless grew into a distinguished center of learning, its progress only briefly interrupted by the troubles of the Reformation.

Published on January 07, 2016 03:00

January 6, 2016

History Trivia - Canute I crowned King of England

January 6

1017 Canute I crowned King of England. He was also King Canute II of Denmark and King Canute of Norway, and because of the empire he built in Britain and Scandinavia, he is sometimes known as Canute the Great.

1017 Canute I crowned King of England. He was also King Canute II of Denmark and King Canute of Norway, and because of the empire he built in Britain and Scandinavia, he is sometimes known as Canute the Great.

Published on January 06, 2016 03:00

January 5, 2016

History Trivia - Edward the Confessor dies

January 5

1066, Edward the Confessor, King of England, died. Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy, was one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England and is usually regarded as the last king of the House of Wessex, and ruled from 1042 to 1066.

1066, Edward the Confessor, King of England, died. Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy, was one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England and is usually regarded as the last king of the House of Wessex, and ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Published on January 05, 2016 03:00

January 4, 2016

History explorer: Wars of the Roses

History Extra

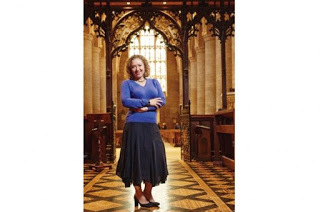

Sarah Gristwood visits Tewkesbury Abbey, where defeated Lancastrian soldiers sought shelter after the battle of Tewkesbury in 1471. Photography by Oliver Edwards.

Sarah Gristwood visits Tewkesbury Abbey, where defeated Lancastrian soldiers sought shelter after the battle of Tewkesbury in 1471. Photography by Oliver Edwards.

Historians can’t agree on when – and where – the Wars of the Roses ended. A few would declare it to have been as late as the battle of Stoke Field in 1487, when Henry VII saw off the last Yorkist army to oppose him. The popular vote goes to the battle of Bosworth in 1485, when Henry Tudor defeated Richard III – but by then the nature of this great familial squabble had already changed.

It was perhaps the battle of Tewkesbury – which took place 14 years earlier, in 1471 – that saw the conclusion of the conflict that truly pitted York against Lancaster. Certainly, that clash brought to an end the so-called Lancastrian ‘Readeption’ that aimed to restore Henry VI to the throne of England.

After the Yorkists seized power in 1461, Edward IV reigned successfully for a decade until, in the autumn of 1470, he was abruptly toppled from his throne. Warwick ‘the Kingmaker’, the powerful Yorkist magnate, had suddenly changed sides and struck an unlikely deal with the exiled Margaret of Anjou, queen to the Lancastrian Henry VI, whom Edward had deposed.

In 1470, as Warwick’s armies seized control of England, it was Edward who was force to flee into exile. The feeble Henry VI was nominally returned to his throne, and for six months Warwick controlled the country while Margaret (with her son – another Edward, the Lancastrian Prince of Wales) bided their time across the Channel.

They may have waited too long. In the spring of 1471, everything changed again. That March, Edward IV was back, and with a fresh army. On Easter Sunday, 14 April, he met Warwick’s forces at Barnet, in an encounter in which Warwick was slain. This was the news that greeted Margaret after she landed at Weymouth, causing her to fall to the ground, the chronicles report, “like a woman all dismayed with fear”.

But all was not yet lost. While Margaret gathered more troops, her ally Jasper Tudor raised another army in Wales. However, she was separated from him by the river Severn. The crossing at Gloucester was blocked by the Yorkists, so she turned towards Tewkesbury.

The race to the river was on. The weather was unseasonably hot for early May, and men and horses became frantic for lack of food and water. When they reached the town of Tewkesbury late in the afternoon of 3 May, Margaret’s exhausted men could go no further. Battle was joined the next morning, in terrain one chronicle describes as a morass of “evil lanes and deep dykes, so many hedges, trees and bushes, that it was hard... to come to hand”.

Margaret herself took refuge in the abbey. Legend tells that she mounted the 200 steps of its tower – still accessible today by prior arrangement – from where she could view the fighting all too clearly. What she saw, to her horror, was an overwhelming Yorkist victory, thanks in part to Edward’s clever deployment of his forces but also to the failure to advance of one veteran Lancastrian commander. A nearby field is still dubbed Bloody Meadow in memory of the slaughter of hapless Lancastrians that took place there. Among the dead was Margaret’s son, probably killed as he fled the battle scene.

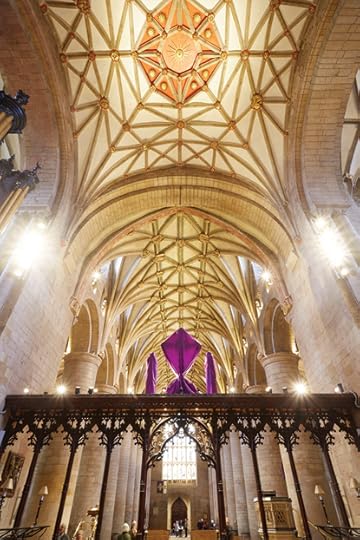

Tewkesbury Abbey. © Oliver Edwards

Many of the defeated Lancastrians fled into the abbey, claiming sanctuary. The different chronicles vary sharply in their versions of what happened there – and the propaganda war of this era, in which the different sides told two quite different stories, is a saga that can be traced through the stones of Tewkesbury Abbey.

Edward and his two brothers – George, Duke of Clarence, and Richard of Gloucester – pursued the fugitives onto consecrated ground, demanding that the abbot hand them over. One tale tells of Edward bursting into the church itself, sword in hand, at the very moment Mass was being celebrated, only to be confronted by the abbot wielding the Host. The story describes a bloodletting so great – perhaps even under the very pillars of the nave that still stand today – that the church had to be reconsecrated.

What is certain is that the Lancastrian leaders were handed over, tried, and summarily executed in Tewkesbury’s marketplace the next day. They are buried under what now serves as the abbey shop.

Margaret herself had fled farther afield. She was captured three days later in a “poor religious house” near Malvern, and displayed in Edward IV’s train as he re-entered London in triumph. That night, Henry VI died – “of pure displeasure and melancholy”, said the Yorkists, though the Lancastrians all-too credibly told a different story.

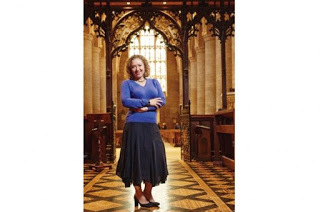

Sarah Gristwood looks out from the tower where Margaret of Anjou is said to have watched events unfold, over the fields where, in 1471, the battle of Tewkesbury was fought. © Oliver Edwards

Margaret was kept in custody until she was eventually ransomed back to her native France, where she died in poverty. After Tewkesbury she had become irrelevant. She had been a formidable fighter – a “tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide,” as Shakespeare would describe her. But now she had no Lancastrian claimant for whom to fight. Her son was buried in Tewkesbury Abbey, where he is commemorated by a plaque – ironically placed right under the ‘Sun in Splendour’ emblem, representing the victorious York brothers, on the ceiling.

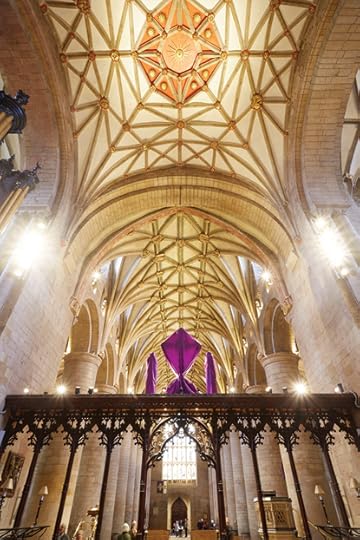

The red ‘Sun in Splendour’ emblem commemorates the Yorkist victory. © Oliver Edwards

Edward’s plaque was laid during Sir Gilbert Scott’s Victorian restoration of Tewkesbury. The church (purchased by the townspeople when the rest of the abbey disappeared in the Dissolution of the Monasteries) retains genuine medieval remains aplenty: the famous bosses in the nave, the exquisite stonework of the chantries, the glass of the quire clerestory – and the mortal remains of one of the wars’ most debatable personalities.

Edward IV’s brother George, Duke of Clarence, had originally joined Warwick’s coup but, in the weeks before Tewkesbury, had come back over to his brother’s side. Six years later, however, the fickle Clarence rebelled again. Reputedly executed by being drowned in a butt of malmsey wine, in 1478, he was buried beside his wife, Isabel, Warwick’s daughter, in Tewkesbury Abbey.

A grating on the floor behind the altar hides the cramped vault where the bones of George and Isabel lie jumbled. Indeed, Tewkesbury keeps some of its extraordinary history hidden from the casual eye. For example, horse armour taken from the battlefield by monks strengthens the reverse side of the closed door to the sacristy. And the town itself is riddled with myriad alleys to be discovered as you explore the countless agreeably junky antique shops and delightfully eccentric tea rooms.

But on the other side of the abbey from the town’s timber-framed houses, the lush, green ground where the armies struggled in 1471 still looks much the same. Get a Battle Trail plan from the town’s visitor centre, or see the display in the museum, and the Wars of the Roses are laid out before you – the whole messy human story.

Five more places to explore1) Cambridge

visitcambridge.org

No battles were fought here, but the city is still one of the best places to get a feel for the late 15th century. Margaret of Anjou, Elizabeth Woodville and Anne Neville were all patrons of Queens’ College, while King’s College was founded by Henry VI, and construction of its famous chapel continued under Henry VII and his son – an example in stone and glass of the progress of a vital half-century.

King’s College Cambridge was founded by Lancastrian king Henry VI. © Alamy

Margaret Beaufort, Henry VII’s mother, founded both St John’s and Christ’s colleges; she kept her own set of rooms in the latter, and visited regularly.

2) Leicester

leicester.gov.uk/museums

An exhibition about the king is housed in an extraordinary series of medieval buildings that have stood since the 14th century. The Guildhall complex comprises elements ranging from cells to a wonderfully preserved great hall – a little-known treasure, and an obvious contender for a combined excursion with Bosworth (see no 5), only 11 miles away.

3) Tower of London

hrp.org.uk/TowerOfLondon

The Tower is associated above all with the mysterious fate of Richard III’s nephews, the unfortunate princes. But it’s also where Elizabeth Woodville first took refuge in 1470, where Elizabeth of York retreated during the rebellion of 1497, and where Henry VI died in mysterious circumstances. Its strategic and symbolic importance in the medieval era is still evident today.

4) Middleham Castle, North Yorkshire

english-heritage.org.uk

The north of England provided Richard III with the power base he needed to seize the English throne, and Middleham Castle in the Yorkshire Dales was his favourite residence.

Middleham Castle in Yorkshire was Richard III’s favourite residence. © Alamy

His short-lived son was Edward ‘of Middleham’, who died there in childhood. Largely ruined, and now in the care of English Heritage, the castle nonetheless retains evocative reminders of Richard’s day.

5) Bosworth battlefield, Leicestershire

bosworthbattlefield.com

The precise conduct of the battle in which Richard III was killed seems always to be in dispute – but there’s no questioning the interest created by the new heritage centre: family-friendly, it’s informative for adults, too.

Visitors to Bosworth battlefield can experience the weight of medieval armour. © Anne Boleyn Files

Ever wondered why the battle was fought at Bosworth? Because the site is crossed by Roman roads – themselves tributes to even earlier English history – and battles were fought in places to which troops could travel quickly.

Sarah Gristwood is an author and historian. Her books include Blood Sisters: The Women Behind the Wars of the Roses (HarperPress, 2013).

Sarah Gristwood visits Tewkesbury Abbey, where defeated Lancastrian soldiers sought shelter after the battle of Tewkesbury in 1471. Photography by Oliver Edwards.

Sarah Gristwood visits Tewkesbury Abbey, where defeated Lancastrian soldiers sought shelter after the battle of Tewkesbury in 1471. Photography by Oliver Edwards. Historians can’t agree on when – and where – the Wars of the Roses ended. A few would declare it to have been as late as the battle of Stoke Field in 1487, when Henry VII saw off the last Yorkist army to oppose him. The popular vote goes to the battle of Bosworth in 1485, when Henry Tudor defeated Richard III – but by then the nature of this great familial squabble had already changed.

It was perhaps the battle of Tewkesbury – which took place 14 years earlier, in 1471 – that saw the conclusion of the conflict that truly pitted York against Lancaster. Certainly, that clash brought to an end the so-called Lancastrian ‘Readeption’ that aimed to restore Henry VI to the throne of England.

After the Yorkists seized power in 1461, Edward IV reigned successfully for a decade until, in the autumn of 1470, he was abruptly toppled from his throne. Warwick ‘the Kingmaker’, the powerful Yorkist magnate, had suddenly changed sides and struck an unlikely deal with the exiled Margaret of Anjou, queen to the Lancastrian Henry VI, whom Edward had deposed.

In 1470, as Warwick’s armies seized control of England, it was Edward who was force to flee into exile. The feeble Henry VI was nominally returned to his throne, and for six months Warwick controlled the country while Margaret (with her son – another Edward, the Lancastrian Prince of Wales) bided their time across the Channel.

They may have waited too long. In the spring of 1471, everything changed again. That March, Edward IV was back, and with a fresh army. On Easter Sunday, 14 April, he met Warwick’s forces at Barnet, in an encounter in which Warwick was slain. This was the news that greeted Margaret after she landed at Weymouth, causing her to fall to the ground, the chronicles report, “like a woman all dismayed with fear”.

But all was not yet lost. While Margaret gathered more troops, her ally Jasper Tudor raised another army in Wales. However, she was separated from him by the river Severn. The crossing at Gloucester was blocked by the Yorkists, so she turned towards Tewkesbury.

The race to the river was on. The weather was unseasonably hot for early May, and men and horses became frantic for lack of food and water. When they reached the town of Tewkesbury late in the afternoon of 3 May, Margaret’s exhausted men could go no further. Battle was joined the next morning, in terrain one chronicle describes as a morass of “evil lanes and deep dykes, so many hedges, trees and bushes, that it was hard... to come to hand”.

Margaret herself took refuge in the abbey. Legend tells that she mounted the 200 steps of its tower – still accessible today by prior arrangement – from where she could view the fighting all too clearly. What she saw, to her horror, was an overwhelming Yorkist victory, thanks in part to Edward’s clever deployment of his forces but also to the failure to advance of one veteran Lancastrian commander. A nearby field is still dubbed Bloody Meadow in memory of the slaughter of hapless Lancastrians that took place there. Among the dead was Margaret’s son, probably killed as he fled the battle scene.

Tewkesbury Abbey. © Oliver Edwards

Many of the defeated Lancastrians fled into the abbey, claiming sanctuary. The different chronicles vary sharply in their versions of what happened there – and the propaganda war of this era, in which the different sides told two quite different stories, is a saga that can be traced through the stones of Tewkesbury Abbey.

Edward and his two brothers – George, Duke of Clarence, and Richard of Gloucester – pursued the fugitives onto consecrated ground, demanding that the abbot hand them over. One tale tells of Edward bursting into the church itself, sword in hand, at the very moment Mass was being celebrated, only to be confronted by the abbot wielding the Host. The story describes a bloodletting so great – perhaps even under the very pillars of the nave that still stand today – that the church had to be reconsecrated.

What is certain is that the Lancastrian leaders were handed over, tried, and summarily executed in Tewkesbury’s marketplace the next day. They are buried under what now serves as the abbey shop.

Margaret herself had fled farther afield. She was captured three days later in a “poor religious house” near Malvern, and displayed in Edward IV’s train as he re-entered London in triumph. That night, Henry VI died – “of pure displeasure and melancholy”, said the Yorkists, though the Lancastrians all-too credibly told a different story.

Sarah Gristwood looks out from the tower where Margaret of Anjou is said to have watched events unfold, over the fields where, in 1471, the battle of Tewkesbury was fought. © Oliver Edwards

Margaret was kept in custody until she was eventually ransomed back to her native France, where she died in poverty. After Tewkesbury she had become irrelevant. She had been a formidable fighter – a “tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide,” as Shakespeare would describe her. But now she had no Lancastrian claimant for whom to fight. Her son was buried in Tewkesbury Abbey, where he is commemorated by a plaque – ironically placed right under the ‘Sun in Splendour’ emblem, representing the victorious York brothers, on the ceiling.

The red ‘Sun in Splendour’ emblem commemorates the Yorkist victory. © Oliver Edwards

Edward’s plaque was laid during Sir Gilbert Scott’s Victorian restoration of Tewkesbury. The church (purchased by the townspeople when the rest of the abbey disappeared in the Dissolution of the Monasteries) retains genuine medieval remains aplenty: the famous bosses in the nave, the exquisite stonework of the chantries, the glass of the quire clerestory – and the mortal remains of one of the wars’ most debatable personalities.

Edward IV’s brother George, Duke of Clarence, had originally joined Warwick’s coup but, in the weeks before Tewkesbury, had come back over to his brother’s side. Six years later, however, the fickle Clarence rebelled again. Reputedly executed by being drowned in a butt of malmsey wine, in 1478, he was buried beside his wife, Isabel, Warwick’s daughter, in Tewkesbury Abbey.

A grating on the floor behind the altar hides the cramped vault where the bones of George and Isabel lie jumbled. Indeed, Tewkesbury keeps some of its extraordinary history hidden from the casual eye. For example, horse armour taken from the battlefield by monks strengthens the reverse side of the closed door to the sacristy. And the town itself is riddled with myriad alleys to be discovered as you explore the countless agreeably junky antique shops and delightfully eccentric tea rooms.

But on the other side of the abbey from the town’s timber-framed houses, the lush, green ground where the armies struggled in 1471 still looks much the same. Get a Battle Trail plan from the town’s visitor centre, or see the display in the museum, and the Wars of the Roses are laid out before you – the whole messy human story.

Five more places to explore1) Cambridge

visitcambridge.org

No battles were fought here, but the city is still one of the best places to get a feel for the late 15th century. Margaret of Anjou, Elizabeth Woodville and Anne Neville were all patrons of Queens’ College, while King’s College was founded by Henry VI, and construction of its famous chapel continued under Henry VII and his son – an example in stone and glass of the progress of a vital half-century.

King’s College Cambridge was founded by Lancastrian king Henry VI. © Alamy

Margaret Beaufort, Henry VII’s mother, founded both St John’s and Christ’s colleges; she kept her own set of rooms in the latter, and visited regularly.

2) Leicester

leicester.gov.uk/museums

An exhibition about the king is housed in an extraordinary series of medieval buildings that have stood since the 14th century. The Guildhall complex comprises elements ranging from cells to a wonderfully preserved great hall – a little-known treasure, and an obvious contender for a combined excursion with Bosworth (see no 5), only 11 miles away.

3) Tower of London

hrp.org.uk/TowerOfLondon

The Tower is associated above all with the mysterious fate of Richard III’s nephews, the unfortunate princes. But it’s also where Elizabeth Woodville first took refuge in 1470, where Elizabeth of York retreated during the rebellion of 1497, and where Henry VI died in mysterious circumstances. Its strategic and symbolic importance in the medieval era is still evident today.

4) Middleham Castle, North Yorkshire

english-heritage.org.uk

The north of England provided Richard III with the power base he needed to seize the English throne, and Middleham Castle in the Yorkshire Dales was his favourite residence.

Middleham Castle in Yorkshire was Richard III’s favourite residence. © Alamy

His short-lived son was Edward ‘of Middleham’, who died there in childhood. Largely ruined, and now in the care of English Heritage, the castle nonetheless retains evocative reminders of Richard’s day.

5) Bosworth battlefield, Leicestershire

bosworthbattlefield.com

The precise conduct of the battle in which Richard III was killed seems always to be in dispute – but there’s no questioning the interest created by the new heritage centre: family-friendly, it’s informative for adults, too.

Visitors to Bosworth battlefield can experience the weight of medieval armour. © Anne Boleyn Files

Ever wondered why the battle was fought at Bosworth? Because the site is crossed by Roman roads – themselves tributes to even earlier English history – and battles were fought in places to which troops could travel quickly.

Sarah Gristwood is an author and historian. Her books include Blood Sisters: The Women Behind the Wars of the Roses (HarperPress, 2013).

Published on January 04, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Battle of Reading, Danish Vikings victorious

January 4

871 at the Battle of Reading Ethelred of Wessex fought and was badly defeated by a Danish invasion army.

871 at the Battle of Reading Ethelred of Wessex fought and was badly defeated by a Danish invasion army.

Published on January 04, 2016 02:00

January 3, 2016

Ruthless Perception of Vikings Returns as Evidence of the Use of Slaves During the Viking Age Comes into Focus Yet Again

Ancient Origins

Over the last few years the perception of Vikings has been ever sliding on the scale from less to more brutish. Things are getting closer to the “ruthless” end of the scale yet again, as researchers are once more examining evidence that slavery was an essential element to life during the Viking age.

Over the last few years the perception of Vikings has been ever sliding on the scale from less to more brutish. Things are getting closer to the “ruthless” end of the scale yet again, as researchers are once more examining evidence that slavery was an essential element to life during the Viking age.

“This was a slave economy. [Viking Age] slavery has received hardly any attention in the past 30 years, but now we have opportunities using archaeological tools to change this.” Neil Price, an archaeologist at Sweden’s Uppsala University, told National Geographic.

Price has a research interest in slavery in the Viking Age economy, and recently discussed the topic at a meeting of archaeologists who share his interest in slavery and colonization. Another researcher who has taken an interest in this theme is David Wyatt.

Wyatt, of Cardiff University, spoke of the Viking use of slaves in a lecture during a series of seminars entitled The Dark Ages’ Dirty Secret? Medieval slavery from the British Isles to the Eurasian steppes and the Mediterranean world. These seminars were held in Oxford from April-June this year. Wyatt’s seminar provided a great deal of evidence of the Vikings use of slavery from historical sources, such as Sagas.

However, the idea of thralls (the word for slave in Old Norse) being a part of the Viking lifestyle is not completely new information to archaeologists. As Ancient Origins reported in 2013: “a number of Viking graves have included the remains of slaves as “grave goods.””

The 2013 burial discovered in Flakstad, Norway, contained several bodies of decapitated thralls buried with their masters. The identity of the decapitated individuals as slaves was made by an analysis of the diets of the dead. The individuals without their heads had simpler diets of seafood, and were named as the thralls of those who were buried with their heads intact and diets that contained milk and beef.

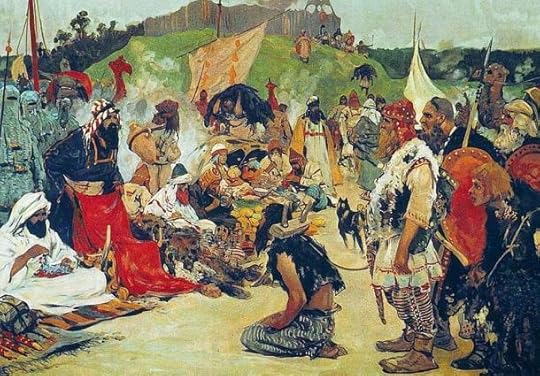

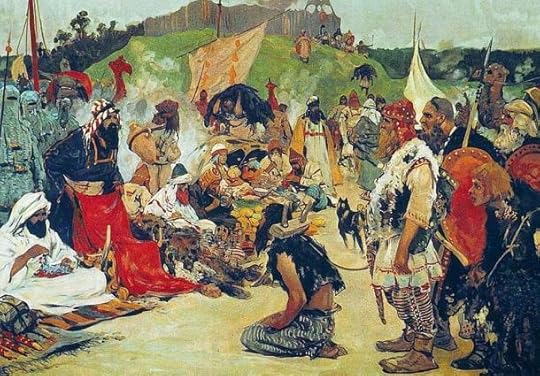

‘Slaves and thralls in the Viking Age.’ (

National Museum of Denmark

)Although the topic remains controversial, in 2013, Elise Naumann, an archaeologist at the University of Oslo in Norway, explained that the thralls could have been sacrificed to be placed in the graves of their masters: "We propose that the people buried in double and triple burials might have come from very different strata of society, and that slaves could have been offered as grave gifts in these burials." The sacrifice of thralls as “grave goods” would further demonstrate their importance to the lives and afterlives of Norsemen.

‘Slaves and thralls in the Viking Age.’ (

National Museum of Denmark

)Although the topic remains controversial, in 2013, Elise Naumann, an archaeologist at the University of Oslo in Norway, explained that the thralls could have been sacrificed to be placed in the graves of their masters: "We propose that the people buried in double and triple burials might have come from very different strata of society, and that slaves could have been offered as grave gifts in these burials." The sacrifice of thralls as “grave goods” would further demonstrate their importance to the lives and afterlives of Norsemen.

New study shows Viking women accompanied men on voyages to colonize far-flung landsNorsemen transformed international culture, manufacturing, tech and trade during Viking EraThe 10th century chronicle of the violent, orgiastic funeral of a Viking chieftainDiscovery of Reindeer Antlers in Denmark may Rewrite Start of Viking AgeResearchers have not only shown interest in the role of thralls as sacrificial victims, but also the way that they were obtained by the Vikings. Price says that a desire to increase the number of thralls “was a very significant motivator in raiding.”

As the National Museum of Denmark notes: slaves were primarily acquired on Viking expeditions to Eastern Europe and the British Isles. However, this was not the only source for thralls, as “they could also obtain Viking slaves at home, as crimes like murder and thievery were punished with slavery.”

One of the main reasons suggested for the use of thralls by the Vikings was the need for a larger workforce The principal product could have been textile work (especially wool for ship sails). Nevertheless, slave trading was also an important aspect to the Viking economy, and it has been argued that the term slave arose from the heavy targeting of Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe by the Vikings (and other European slave traders.) Major slave trading centers for the Vikings have been identified at Hedeby and Bolghar on the Volga.

[image error]

[image error]<a href="http://us-ads.openx.net/w/1.0/rc?cs=1..." ><img src="http://us-ads.openx.net/w/1.0/ai?auid..." border="0" alt=""></a>

[image error]

[image error]<a href="http://us-ads.openx.net/w/1.0/rc?cs=1..." ><img src="http://us-ads.openx.net/w/1.0/ai?auid..." border="0" alt=""></a>

‘Trade negotiations in the country of Eastern Slavs.’ (1909) By Sergei Vasilyevich Ivanov. ( Public Domain )Researchers have also suggested that the women abducted during Viking raids were taken as concubines, domestic workers, cooks, and perhaps even as brides. This last proposition arises from a belief that Vikings were a polygamous society – which would have made it more difficult for non-elite men to acquire a bride.

The Annals of Ulster , with entries spanning 431- 1540, provides textual evidence of “a great number of women” being taken captive by “the heathens” (which some scholars suggest refers to Vikings) in Étar (near Dublin, Ireland) in 821 AD. These annals of Medieval Ireland also provide several other examples of the Viking “heathens” attacking, plundering, and abducting people from the area.

‘Les pirates normands au IXe siècle’ (Norman pirates in the 9th century) by Évariste-Vital Luminais (1894). (

Public Domain

)The renewed interest in literary and other material evidence of the Viking use of slaves over in recent years suggests that the perception of Vikings may be changing more heavily towards the ruthless perspective yet again…however, for some scholars it is probable that the view of a gentle Viking never existed, and for others it will not change.

‘Les pirates normands au IXe siècle’ (Norman pirates in the 9th century) by Évariste-Vital Luminais (1894). (

Public Domain

)The renewed interest in literary and other material evidence of the Viking use of slaves over in recent years suggests that the perception of Vikings may be changing more heavily towards the ruthless perspective yet again…however, for some scholars it is probable that the view of a gentle Viking never existed, and for others it will not change.

Featured Image: A Viking offers a slave girl to a Persian merchant. Source: Tom Lovell/National Geographic

By: Alicia McDermott

Over the last few years the perception of Vikings has been ever sliding on the scale from less to more brutish. Things are getting closer to the “ruthless” end of the scale yet again, as researchers are once more examining evidence that slavery was an essential element to life during the Viking age.

Over the last few years the perception of Vikings has been ever sliding on the scale from less to more brutish. Things are getting closer to the “ruthless” end of the scale yet again, as researchers are once more examining evidence that slavery was an essential element to life during the Viking age.“This was a slave economy. [Viking Age] slavery has received hardly any attention in the past 30 years, but now we have opportunities using archaeological tools to change this.” Neil Price, an archaeologist at Sweden’s Uppsala University, told National Geographic.

Price has a research interest in slavery in the Viking Age economy, and recently discussed the topic at a meeting of archaeologists who share his interest in slavery and colonization. Another researcher who has taken an interest in this theme is David Wyatt.

Wyatt, of Cardiff University, spoke of the Viking use of slaves in a lecture during a series of seminars entitled The Dark Ages’ Dirty Secret? Medieval slavery from the British Isles to the Eurasian steppes and the Mediterranean world. These seminars were held in Oxford from April-June this year. Wyatt’s seminar provided a great deal of evidence of the Vikings use of slavery from historical sources, such as Sagas.

However, the idea of thralls (the word for slave in Old Norse) being a part of the Viking lifestyle is not completely new information to archaeologists. As Ancient Origins reported in 2013: “a number of Viking graves have included the remains of slaves as “grave goods.””

The 2013 burial discovered in Flakstad, Norway, contained several bodies of decapitated thralls buried with their masters. The identity of the decapitated individuals as slaves was made by an analysis of the diets of the dead. The individuals without their heads had simpler diets of seafood, and were named as the thralls of those who were buried with their heads intact and diets that contained milk and beef.

‘Slaves and thralls in the Viking Age.’ (

National Museum of Denmark

)Although the topic remains controversial, in 2013, Elise Naumann, an archaeologist at the University of Oslo in Norway, explained that the thralls could have been sacrificed to be placed in the graves of their masters: "We propose that the people buried in double and triple burials might have come from very different strata of society, and that slaves could have been offered as grave gifts in these burials." The sacrifice of thralls as “grave goods” would further demonstrate their importance to the lives and afterlives of Norsemen.

‘Slaves and thralls in the Viking Age.’ (

National Museum of Denmark

)Although the topic remains controversial, in 2013, Elise Naumann, an archaeologist at the University of Oslo in Norway, explained that the thralls could have been sacrificed to be placed in the graves of their masters: "We propose that the people buried in double and triple burials might have come from very different strata of society, and that slaves could have been offered as grave gifts in these burials." The sacrifice of thralls as “grave goods” would further demonstrate their importance to the lives and afterlives of Norsemen.New study shows Viking women accompanied men on voyages to colonize far-flung landsNorsemen transformed international culture, manufacturing, tech and trade during Viking EraThe 10th century chronicle of the violent, orgiastic funeral of a Viking chieftainDiscovery of Reindeer Antlers in Denmark may Rewrite Start of Viking AgeResearchers have not only shown interest in the role of thralls as sacrificial victims, but also the way that they were obtained by the Vikings. Price says that a desire to increase the number of thralls “was a very significant motivator in raiding.”

As the National Museum of Denmark notes: slaves were primarily acquired on Viking expeditions to Eastern Europe and the British Isles. However, this was not the only source for thralls, as “they could also obtain Viking slaves at home, as crimes like murder and thievery were punished with slavery.”

One of the main reasons suggested for the use of thralls by the Vikings was the need for a larger workforce The principal product could have been textile work (especially wool for ship sails). Nevertheless, slave trading was also an important aspect to the Viking economy, and it has been argued that the term slave arose from the heavy targeting of Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe by the Vikings (and other European slave traders.) Major slave trading centers for the Vikings have been identified at Hedeby and Bolghar on the Volga.

[image error]

[image error]<a href="http://us-ads.openx.net/w/1.0/rc?cs=1..." ><img src="http://us-ads.openx.net/w/1.0/ai?auid..." border="0" alt=""></a>

[image error]

[image error]<a href="http://us-ads.openx.net/w/1.0/rc?cs=1..." ><img src="http://us-ads.openx.net/w/1.0/ai?auid..." border="0" alt=""></a>‘Trade negotiations in the country of Eastern Slavs.’ (1909) By Sergei Vasilyevich Ivanov. ( Public Domain )Researchers have also suggested that the women abducted during Viking raids were taken as concubines, domestic workers, cooks, and perhaps even as brides. This last proposition arises from a belief that Vikings were a polygamous society – which would have made it more difficult for non-elite men to acquire a bride.

The Annals of Ulster , with entries spanning 431- 1540, provides textual evidence of “a great number of women” being taken captive by “the heathens” (which some scholars suggest refers to Vikings) in Étar (near Dublin, Ireland) in 821 AD. These annals of Medieval Ireland also provide several other examples of the Viking “heathens” attacking, plundering, and abducting people from the area.

‘Les pirates normands au IXe siècle’ (Norman pirates in the 9th century) by Évariste-Vital Luminais (1894). (

Public Domain

)The renewed interest in literary and other material evidence of the Viking use of slaves over in recent years suggests that the perception of Vikings may be changing more heavily towards the ruthless perspective yet again…however, for some scholars it is probable that the view of a gentle Viking never existed, and for others it will not change.

‘Les pirates normands au IXe siècle’ (Norman pirates in the 9th century) by Évariste-Vital Luminais (1894). (

Public Domain

)The renewed interest in literary and other material evidence of the Viking use of slaves over in recent years suggests that the perception of Vikings may be changing more heavily towards the ruthless perspective yet again…however, for some scholars it is probable that the view of a gentle Viking never existed, and for others it will not change.Featured Image: A Viking offers a slave girl to a Persian merchant. Source: Tom Lovell/National Geographic

By: Alicia McDermott

Published on January 03, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Joan of Arc handed over to the British

January 3

1431 Joan of Arc was handed over to Bishop Pierre Cauchon. Legal proceedings began on 9 January 1431 at Rouen, the seat of the English occupation government where Joan was found guilty of heresy, and was burned at the stake on May 30.

1431 Joan of Arc was handed over to Bishop Pierre Cauchon. Legal proceedings began on 9 January 1431 at Rouen, the seat of the English occupation government where Joan was found guilty of heresy, and was burned at the stake on May 30.

Published on January 03, 2016 02:30

January 2, 2016

Gold pieces retrieved from Thames River most likely part of elaborate Tudor era hat

Ancient Origins

Beautifully fashioned little gold fasteners that probably adorned a hat or clothing in the 16th century have been turned up by eight people with metal detectors scanning the mud along the Thames River in London over several years. An archaeologist speculates the 12 pieces found over the years, all in the same place, belonged to a single piece of headgear that was blown into the river by a gust of wind. They think the person wearing the hat may have been on a ferry in the Thames.

The media are calling it a treasure hoard of Tudor gold, dating to 1500 to 1550, when the main way to get across the river was by ferry.

“Such metal objects, including aglets – metal tips for laces – beads and studs, originally had a practical purpose as garment fasteners but by the early 16th century were being worn in gold as high-status ornaments, making costly fabrics such as velvet and furs even more ostentatious. Contemporary portraits, including one in the National Portrait Gallery of the Dacres, Mary Neville and Gregory Fiennes, show their sleeves festooned with pairs of such ornaments,” says The Guardian in an article about the finds.

The fabric has long since worn away to nothing. Some of the pieces are inlaid with little bits of colored glass or enamel. In total they comprise a very small amount of gold but are legally treasure that must be reported to a British government finds officer, in this case Kate Sumnall of the London Museum. The museum hopes to acquire the pieces and put them on display after a valuation and inquest.

Jane Seymour painting by Hans Holbein, 1537; note the gold worked into the fabric along the collar and the gold and jewels and pearls on the hat. Jane Seymour was briefly queen of England as Henry VIII’s wife. (Photo by UVM.edu)It is Sumnall’s theory that wind blew a fantastic, gold-adorned hat off someone’s head into the river. She said the pieces are of very fine quality workmanship.

Jane Seymour painting by Hans Holbein, 1537; note the gold worked into the fabric along the collar and the gold and jewels and pearls on the hat. Jane Seymour was briefly queen of England as Henry VIII’s wife. (Photo by UVM.edu)It is Sumnall’s theory that wind blew a fantastic, gold-adorned hat off someone’s head into the river. She said the pieces are of very fine quality workmanship.

“These artefacts have been reported to me one at a time over the last couple of years,” she told the Guardian. “Individually they are all wonderful finds but as a group they are even more important. To find them from just one area suggests a lost ornate hat or other item of clothing. The fabric has not survived and all that remains are these gold decorative elements that hint at the fashion of the time.”

The website A History of Tudor Clothes, written by Tim Lambert, says all people of the era in England wore wool, poor people coarse wool and the rich fine wool. Fashion was important to the rich, the article says.

Rich men wore trousers that were called breeches, tight jackets called doublets and a jerkin over that. They also wore a gown over the jerkin or later a cape or cloak.

Women wore a shift or chemise of wool or linen under their dresses, which were also of wool or linen. The dress was in two parts—a skirt and a bodice. Sleeves were detachable and were held on with laces. Over all this, working women wore linen aprons. The clothing was woven with silk or even gold or silver thread.

Lambert writes that all Tudors wore hats, in fact by law after 1572 all men except nobles were required to wear a woolen cap on Sundays.

In the 16th century, buttons were decorative because most clothing was held together by pins or laces. Furs used in clothing included cat, beaver, rabbit, bear, polecat and badger. Dyes were vegetable-based and fixed with chemicals called mordants. Bright red, purple and indigo were the most expensive, so the poor wore brown, yellow or blue.

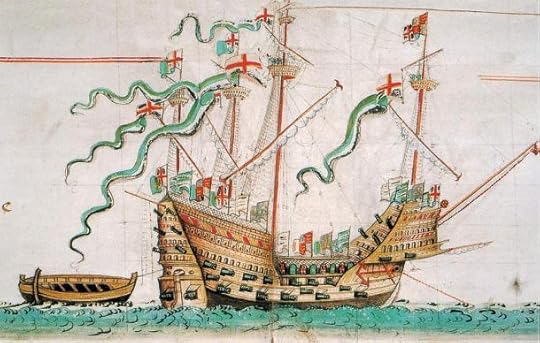

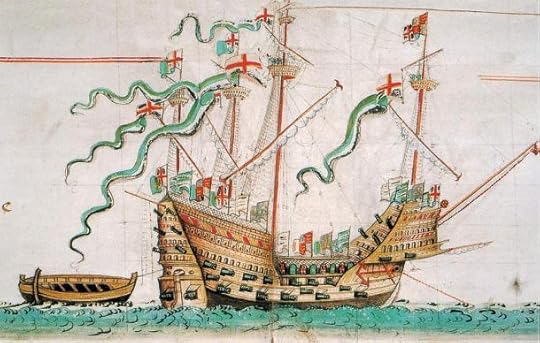

It’s rather unsavory to consider, but people who could afford it wore a container of sweet spices on their belts to cover up the smells in the streets. Lambert says, however, that it’s a myth that people of Tudor times were dirty and stunk. They tried to keep clean, he writes, but many people did have lice. Many lice combs were found on the wreck of the Mary Rose, he writes.

A 1547 illustration of the carrack Tudor ship Mary Rose, upon which were found many lice combs. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Featured image: Twelve gold pieces of very fine workmanship have been discovered in the mud of the River Thames over the years by people with metal detectors. (PA photo)

A 1547 illustration of the carrack Tudor ship Mary Rose, upon which were found many lice combs. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Featured image: Twelve gold pieces of very fine workmanship have been discovered in the mud of the River Thames over the years by people with metal detectors. (PA photo)

By Mark Miller

Beautifully fashioned little gold fasteners that probably adorned a hat or clothing in the 16th century have been turned up by eight people with metal detectors scanning the mud along the Thames River in London over several years. An archaeologist speculates the 12 pieces found over the years, all in the same place, belonged to a single piece of headgear that was blown into the river by a gust of wind. They think the person wearing the hat may have been on a ferry in the Thames.

The media are calling it a treasure hoard of Tudor gold, dating to 1500 to 1550, when the main way to get across the river was by ferry.

“Such metal objects, including aglets – metal tips for laces – beads and studs, originally had a practical purpose as garment fasteners but by the early 16th century were being worn in gold as high-status ornaments, making costly fabrics such as velvet and furs even more ostentatious. Contemporary portraits, including one in the National Portrait Gallery of the Dacres, Mary Neville and Gregory Fiennes, show their sleeves festooned with pairs of such ornaments,” says The Guardian in an article about the finds.

The fabric has long since worn away to nothing. Some of the pieces are inlaid with little bits of colored glass or enamel. In total they comprise a very small amount of gold but are legally treasure that must be reported to a British government finds officer, in this case Kate Sumnall of the London Museum. The museum hopes to acquire the pieces and put them on display after a valuation and inquest.

Jane Seymour painting by Hans Holbein, 1537; note the gold worked into the fabric along the collar and the gold and jewels and pearls on the hat. Jane Seymour was briefly queen of England as Henry VIII’s wife. (Photo by UVM.edu)It is Sumnall’s theory that wind blew a fantastic, gold-adorned hat off someone’s head into the river. She said the pieces are of very fine quality workmanship.

Jane Seymour painting by Hans Holbein, 1537; note the gold worked into the fabric along the collar and the gold and jewels and pearls on the hat. Jane Seymour was briefly queen of England as Henry VIII’s wife. (Photo by UVM.edu)It is Sumnall’s theory that wind blew a fantastic, gold-adorned hat off someone’s head into the river. She said the pieces are of very fine quality workmanship.“These artefacts have been reported to me one at a time over the last couple of years,” she told the Guardian. “Individually they are all wonderful finds but as a group they are even more important. To find them from just one area suggests a lost ornate hat or other item of clothing. The fabric has not survived and all that remains are these gold decorative elements that hint at the fashion of the time.”

The website A History of Tudor Clothes, written by Tim Lambert, says all people of the era in England wore wool, poor people coarse wool and the rich fine wool. Fashion was important to the rich, the article says.

Rich men wore trousers that were called breeches, tight jackets called doublets and a jerkin over that. They also wore a gown over the jerkin or later a cape or cloak.

Women wore a shift or chemise of wool or linen under their dresses, which were also of wool or linen. The dress was in two parts—a skirt and a bodice. Sleeves were detachable and were held on with laces. Over all this, working women wore linen aprons. The clothing was woven with silk or even gold or silver thread.

Lambert writes that all Tudors wore hats, in fact by law after 1572 all men except nobles were required to wear a woolen cap on Sundays.

In the 16th century, buttons were decorative because most clothing was held together by pins or laces. Furs used in clothing included cat, beaver, rabbit, bear, polecat and badger. Dyes were vegetable-based and fixed with chemicals called mordants. Bright red, purple and indigo were the most expensive, so the poor wore brown, yellow or blue.

It’s rather unsavory to consider, but people who could afford it wore a container of sweet spices on their belts to cover up the smells in the streets. Lambert says, however, that it’s a myth that people of Tudor times were dirty and stunk. They tried to keep clean, he writes, but many people did have lice. Many lice combs were found on the wreck of the Mary Rose, he writes.

A 1547 illustration of the carrack Tudor ship Mary Rose, upon which were found many lice combs. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Featured image: Twelve gold pieces of very fine workmanship have been discovered in the mud of the River Thames over the years by people with metal detectors. (PA photo)

A 1547 illustration of the carrack Tudor ship Mary Rose, upon which were found many lice combs. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Featured image: Twelve gold pieces of very fine workmanship have been discovered in the mud of the River Thames over the years by people with metal detectors. (PA photo)By Mark Miller

Published on January 02, 2016 03:00

History Trivia - Alemanni cross the frozen Rhine River

January 2

366 The Alemanni crossed the frozen Rhine River in large numbers and invaded the Roman Empire.

366 The Alemanni crossed the frozen Rhine River in large numbers and invaded the Roman Empire.

Published on January 02, 2016 02:00

January 1, 2016

Happy New Year 2016

Wishing everyone a very Happy New Year.

I am grateful for your support and interest in my work.

God bless.

Mary Ann Bernal

Published on January 01, 2016 02:00