MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 122

January 31, 2016

History Trivia - Pope Silvester I succeeds Pope Miltiades

January 31

314 Silvester I began his reign as Pope of the Catholic Church, succeeding Pope Miltiades. During his pontificate, the Basilica of St. John Lateran, Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, St. Peter's Basilica, and several cemeterial churches over the graves of martyrs were founded.

314 Silvester I began his reign as Pope of the Catholic Church, succeeding Pope Miltiades. During his pontificate, the Basilica of St. John Lateran, Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, St. Peter's Basilica, and several cemeterial churches over the graves of martyrs were founded.

Published on January 31, 2016 01:00

January 30, 2016

Scribbler Tales Presents - cover reveal

Coming soon to all online retailers

Escape from Berlin

Mark Dresdner’s cover is blown, forcing him to flee East Germany, yet he refuses to leave the woman he loves. Finding the border crossing blocked, and the enemy closing in, will he evade capture or be forced to make the ultimate sacrifice?

Featuring

BetrayalAelia gives herself completely to the man she loves, revealing a life-threatening secret, trusting her husband unconditionally, but is he deserving of her trust?

Deadly SecretsLysandra seeks a new life in America, hoping to forget her past, but an accidental meeting with a man who knows her true identity endangers her happiness.

Murder in the FirstAs judge, jury, and executioner, Bethel decides the fate of the man responsible for her plight, but things go terribly wrong and the predator becomes the prey.

The RitualDevona’s initiation into a modern-day pagan sect on All Hallows’ Eve sends the terrified young woman fleeing for her life amidst a raging storm. Escaping the sacrificial altar, will she survive the tempest?

Exclusive Bonus MaterialExcerptsThe Briton and the DaneThe Briton and the Dane: BirthrightThe Briton and the Dane: LegacyThe Briton and the Dane: Concordia

The Briton and the Dane: Timeline

Visit Mary Ann Bernal

Visit Whispering Legends Press

Escape from Berlin

Mark Dresdner’s cover is blown, forcing him to flee East Germany, yet he refuses to leave the woman he loves. Finding the border crossing blocked, and the enemy closing in, will he evade capture or be forced to make the ultimate sacrifice?

Featuring

BetrayalAelia gives herself completely to the man she loves, revealing a life-threatening secret, trusting her husband unconditionally, but is he deserving of her trust?

Deadly SecretsLysandra seeks a new life in America, hoping to forget her past, but an accidental meeting with a man who knows her true identity endangers her happiness.

Murder in the FirstAs judge, jury, and executioner, Bethel decides the fate of the man responsible for her plight, but things go terribly wrong and the predator becomes the prey.

The RitualDevona’s initiation into a modern-day pagan sect on All Hallows’ Eve sends the terrified young woman fleeing for her life amidst a raging storm. Escaping the sacrificial altar, will she survive the tempest?

Exclusive Bonus MaterialExcerptsThe Briton and the DaneThe Briton and the Dane: BirthrightThe Briton and the Dane: LegacyThe Briton and the Dane: Concordia

The Briton and the Dane: Timeline

Visit Mary Ann Bernal

Visit Whispering Legends Press

Published on January 30, 2016 13:57

When did Ancient Egypt start and end?

History Extra

When did Ancient Egypt start and end? When we think about ‘ancient Egypt’ we are usually imaginging the dynastic period; the time when Egypt was a united land ruled by a king, or pharaoh. This was the age of the pyramids, mummification and hieroglyphic writing.

The dynastic period started with the reign of Egypt’s first king, Narmer, in approximately 3100 BCE, and ended with the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE. During this long period there were times of strong centalised rule, and periods of much weaker, divided rule, but basically Egypt remained one, independent land.

However, the dynastic period should be seen as part of a much longer, continuous history. Before Narmer united his kingdom, the land that was to become Egypt consisted of a series of sophisticated Neolithic city-states, supported by agricultural communities and linked together by trade. After Cleopatra’s death, Egypt was absorbed by Rome, but many of the old traditions continued.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Life Sciences at the University of Manchester, where she writes and teaches a number of Egyptology courses.

When did Ancient Egypt start and end? When we think about ‘ancient Egypt’ we are usually imaginging the dynastic period; the time when Egypt was a united land ruled by a king, or pharaoh. This was the age of the pyramids, mummification and hieroglyphic writing.

The dynastic period started with the reign of Egypt’s first king, Narmer, in approximately 3100 BCE, and ended with the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BCE. During this long period there were times of strong centalised rule, and periods of much weaker, divided rule, but basically Egypt remained one, independent land.

However, the dynastic period should be seen as part of a much longer, continuous history. Before Narmer united his kingdom, the land that was to become Egypt consisted of a series of sophisticated Neolithic city-states, supported by agricultural communities and linked together by trade. After Cleopatra’s death, Egypt was absorbed by Rome, but many of the old traditions continued.

Dr Joyce Tyldesley is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Life Sciences at the University of Manchester, where she writes and teaches a number of Egyptology courses.

Published on January 30, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, ritually executed

January 30

1661 Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England was ritually executed two years after his death, on the anniversary of the execution of the monarch he himself deposed.

1661 Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England was ritually executed two years after his death, on the anniversary of the execution of the monarch he himself deposed.

Published on January 30, 2016 01:00

January 29, 2016

More Evidence that Ancient Romans May Have Made It to Oak Island, Canada

Ancient Origins

What appears to be an ancient Roman sword has been found off the East Coast of Canada, but it is just one of several indications that Romans may have been there around the 2nd century or earlier. That’s at least 800 years before the Vikings landed, which is currently believed to be the first contact between the Old World and the New World.

What appears to be an ancient Roman sword has been found off the East Coast of Canada, but it is just one of several indications that Romans may have been there around the 2nd century or earlier. That’s at least 800 years before the Vikings landed, which is currently believed to be the first contact between the Old World and the New World.

The sword was discovered off the coast of Oak Island, Nova Scotia, during investigations into local lore of treasure buried on the island, conducted as part of the immensely popular History Channel show, “The Curse of Oak Island.”

A map showing Oak Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. (Norman Einstein/CC BY-SA) J. Hutton Pulitzer worked as a consultant on the show for two seasons and he appeared in the show’s second season. His team began investigations on the island eight years before the History Channel arrived in 2013.

A map showing Oak Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. (Norman Einstein/CC BY-SA) J. Hutton Pulitzer worked as a consultant on the show for two seasons and he appeared in the show’s second season. His team began investigations on the island eight years before the History Channel arrived in 2013.

Pulitzer has given Epoch Times exclusive information about new discoveries on the island that, along with the sword, support his theory of a Roman presence.

Pulitzer is a well-known entrepreneur and prolific inventor. Many remember him as the host of the “NetTalkLive” TV show, an early Internet IPO titan, and the inventor of the CueCat (an idea that attracted major investors; it involved a device people could use to scan codes, similar to today’s QR-codes). His company famously went down in flames during the dot-com bubble burst, but Pulitzer’s patents live on today in 11.9 billion mobile devices.

A little over a decade ago, he turned his sights to his passion for lost history and, as an independent researcher and author, he has been working with experts in many fields, to investigate the mysteries of Oak Island.

His theory about an ancient Roman presence on the island has already met with some resistance, as it defies the currently accepted theory that the Vikings were the first Old World explorers to make it to the New World. He asks, however, that historians and archaeologists approach the evidence objectively, without a preconceived idea that the Romans did not make it to the New World.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

J. Hutton Pulitzer. (Courtesy of J. Hutton Pulitzer/InvestigatingHistory.com) The Oak Island sword’s authenticity has been verified by the best available tests, according to Pulitzer (Epoch Times was given access to the testing data).

The sword alone isn’t evidence however that the Romans were on Oak Island themselves. It is possible that someone only a few hundred years ago was sailing near the island and had in his possession this Roman antique. It may have been later explorers who left it there, not the Romans.

But other artifacts also found on-site provide a context that is difficult to dismiss, Pulitzer said.

Other artifacts his team has studied include a stone with an ancient language connected to the Roman Empire, burial mounds in the ancient Roman style, crossbow bolts reportedly confirmed by U.S. government labs to have come from ancient Iberia (encompassed by the Roman Empire), coins connected to the Roman Empire, and more.

The Sword An X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer confirmed the metal composition of the sword matches that of Roman votive swords. XRF testing uses radiation to excite the atoms in the metal to see how the atoms vibrate. Researchers can thus detect which metals are present. Among the materials detected in the sword are zinc, copper, lead, tin, arsenic, gold, silver, and platinum.

These findings are consistent with ancient Roman metallurgy. Modern bronze uses silicon as the primary alloying element, but silicon is absent in the sword, Pulitzer said.

J. Hutton Pulitzer holding an XRF machine. (Courtesy of J. Hutton Pulitzer/InvestigatingHistory.org) A few similar swords have been found in Europe. This model of sword has a depiction of Hercules on the hilt and it is believed to be a ceremonial sword given by Emperor Commodus to outstanding gladiators and warriors. The Museum of Naples made replicas of one of these swords in its collection, leading some to wonder whether the Oak Island weapon is a replica.

J. Hutton Pulitzer holding an XRF machine. (Courtesy of J. Hutton Pulitzer/InvestigatingHistory.org) A few similar swords have been found in Europe. This model of sword has a depiction of Hercules on the hilt and it is believed to be a ceremonial sword given by Emperor Commodus to outstanding gladiators and warriors. The Museum of Naples made replicas of one of these swords in its collection, leading some to wonder whether the Oak Island weapon is a replica.

Though the replicas match the Oak Island sword in appearance, Pulitzer said the tests on its composition have 100 percent confirmed it is not a cast-iron replica. The sword also contains a lode stone that is oriented due north and could thus aid navigation, which is absent in the replicas.

History Channel producers obtained the sword from a local resident, which had been passed down in his family since the 1940s. It was originally found while illegally scalloping and it was pulled up in their rake. The family never told anybody about the discovery until the recent flurry of interest in Oak Island because, in addition to facing penalties for breaking the law, illegal scalloping is frowned upon and considered taboo in the small community.

By Tara MacIsaac , Epoch Times

What appears to be an ancient Roman sword has been found off the East Coast of Canada, but it is just one of several indications that Romans may have been there around the 2nd century or earlier. That’s at least 800 years before the Vikings landed, which is currently believed to be the first contact between the Old World and the New World.

What appears to be an ancient Roman sword has been found off the East Coast of Canada, but it is just one of several indications that Romans may have been there around the 2nd century or earlier. That’s at least 800 years before the Vikings landed, which is currently believed to be the first contact between the Old World and the New World. The sword was discovered off the coast of Oak Island, Nova Scotia, during investigations into local lore of treasure buried on the island, conducted as part of the immensely popular History Channel show, “The Curse of Oak Island.”

A map showing Oak Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. (Norman Einstein/CC BY-SA) J. Hutton Pulitzer worked as a consultant on the show for two seasons and he appeared in the show’s second season. His team began investigations on the island eight years before the History Channel arrived in 2013.

A map showing Oak Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. (Norman Einstein/CC BY-SA) J. Hutton Pulitzer worked as a consultant on the show for two seasons and he appeared in the show’s second season. His team began investigations on the island eight years before the History Channel arrived in 2013. Pulitzer has given Epoch Times exclusive information about new discoveries on the island that, along with the sword, support his theory of a Roman presence.

Pulitzer is a well-known entrepreneur and prolific inventor. Many remember him as the host of the “NetTalkLive” TV show, an early Internet IPO titan, and the inventor of the CueCat (an idea that attracted major investors; it involved a device people could use to scan codes, similar to today’s QR-codes). His company famously went down in flames during the dot-com bubble burst, but Pulitzer’s patents live on today in 11.9 billion mobile devices.

A little over a decade ago, he turned his sights to his passion for lost history and, as an independent researcher and author, he has been working with experts in many fields, to investigate the mysteries of Oak Island.

His theory about an ancient Roman presence on the island has already met with some resistance, as it defies the currently accepted theory that the Vikings were the first Old World explorers to make it to the New World. He asks, however, that historians and archaeologists approach the evidence objectively, without a preconceived idea that the Romans did not make it to the New World.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

J. Hutton Pulitzer. (Courtesy of J. Hutton Pulitzer/InvestigatingHistory.com) The Oak Island sword’s authenticity has been verified by the best available tests, according to Pulitzer (Epoch Times was given access to the testing data).

The sword alone isn’t evidence however that the Romans were on Oak Island themselves. It is possible that someone only a few hundred years ago was sailing near the island and had in his possession this Roman antique. It may have been later explorers who left it there, not the Romans.

But other artifacts also found on-site provide a context that is difficult to dismiss, Pulitzer said.

Other artifacts his team has studied include a stone with an ancient language connected to the Roman Empire, burial mounds in the ancient Roman style, crossbow bolts reportedly confirmed by U.S. government labs to have come from ancient Iberia (encompassed by the Roman Empire), coins connected to the Roman Empire, and more.

The Sword An X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer confirmed the metal composition of the sword matches that of Roman votive swords. XRF testing uses radiation to excite the atoms in the metal to see how the atoms vibrate. Researchers can thus detect which metals are present. Among the materials detected in the sword are zinc, copper, lead, tin, arsenic, gold, silver, and platinum.

These findings are consistent with ancient Roman metallurgy. Modern bronze uses silicon as the primary alloying element, but silicon is absent in the sword, Pulitzer said.

J. Hutton Pulitzer holding an XRF machine. (Courtesy of J. Hutton Pulitzer/InvestigatingHistory.org) A few similar swords have been found in Europe. This model of sword has a depiction of Hercules on the hilt and it is believed to be a ceremonial sword given by Emperor Commodus to outstanding gladiators and warriors. The Museum of Naples made replicas of one of these swords in its collection, leading some to wonder whether the Oak Island weapon is a replica.

J. Hutton Pulitzer holding an XRF machine. (Courtesy of J. Hutton Pulitzer/InvestigatingHistory.org) A few similar swords have been found in Europe. This model of sword has a depiction of Hercules on the hilt and it is believed to be a ceremonial sword given by Emperor Commodus to outstanding gladiators and warriors. The Museum of Naples made replicas of one of these swords in its collection, leading some to wonder whether the Oak Island weapon is a replica. Though the replicas match the Oak Island sword in appearance, Pulitzer said the tests on its composition have 100 percent confirmed it is not a cast-iron replica. The sword also contains a lode stone that is oriented due north and could thus aid navigation, which is absent in the replicas.

History Channel producers obtained the sword from a local resident, which had been passed down in his family since the 1940s. It was originally found while illegally scalloping and it was pulled up in their rake. The family never told anybody about the discovery until the recent flurry of interest in Oak Island because, in addition to facing penalties for breaking the law, illegal scalloping is frowned upon and considered taboo in the small community.

By Tara MacIsaac , Epoch Times

Published on January 29, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Edward III of England crowned

January 29

1327 Edward III was crowned By laying claim to the French throne, he started the Hundred Years' War. He also created Britain's highest knightly order, the Order of the Garter because of his fondness for chivalry.

1327 Edward III was crowned By laying claim to the French throne, he started the Hundred Years' War. He also created Britain's highest knightly order, the Order of the Garter because of his fondness for chivalry.

Published on January 29, 2016 02:00

January 28, 2016

Beer Before Wine: Research Shows that Spain was a Beer Country First

Ancient Origins

A Colorado State University professor says he wants to write a book on caelia—an ancient Spanish beer that was replaced by wine after the Roman Empire invaded Iberia. He also may collaborate with a brewery or the university’s prominent fermentation program to produce a batch of the old brew, which he calls “beer juice.”

A Colorado State University professor says he wants to write a book on caelia—an ancient Spanish beer that was replaced by wine after the Roman Empire invaded Iberia. He also may collaborate with a brewery or the university’s prominent fermentation program to produce a batch of the old brew, which he calls “beer juice.”

But if you’re curious and you’re visiting Spain, some Spanish breweries have already resurrected the beverage, the origins of which date back at least 5,000 years.

Jonathan Carlyon, professor of languages and culture, has been studying the prehistoric Spanish beverage. His specialty at the university is early Hispanic literary culture. He knows a lot about Spanish history and its people’s reliance on caelia and beer until the Romans began making incursions in Hispania beginning around 218 BC and introduced wine, says a press release from Colorado State.

Some Spanish brewers already make caelia, but Professor Carlyon is considering asking a Fort Smith, Colorado, brewery or the university’s fermentation program to brew up a batch too. Apart from writing a paper or a book about the beverage, he expressed his interest in perhaps providing a class on the drink for the university’s fermentation students.

Ancient Monastery Recreates Beer Based on Historic Recipe by British Soldiers Medieval Monks of Bicester Drank 10 Pints of Beer a Week Beer was more important than bread for our Stone Age ancestors “Now beer is worthy of serious academic scholarship,” he is quoted in the press release. “We’re always trying to recruit students to take our courses and get our minor. The Languages, Literatures and Cultures lens can be used in almost any field.”

Colorado State University Professor Jonathan Carlyon with a bottle of caelia from a Spanish microbrewery (CSU photo) “The name Caelia, derived from the Latin verb for heating, ‘calefacere,’ was inspired by the heat used in the brewing process,” the release stated. “Carlyon has tracked the consumption of Caelia back about 5,000 years, to a time in Spain when women brewed the lightly carbonated drink as part of their daily routine, using a fermentation process similar to the one they used to make bread. ‘It was like a beer juice, compared to the beer made today,’ he says.”

Colorado State University Professor Jonathan Carlyon with a bottle of caelia from a Spanish microbrewery (CSU photo) “The name Caelia, derived from the Latin verb for heating, ‘calefacere,’ was inspired by the heat used in the brewing process,” the release stated. “Carlyon has tracked the consumption of Caelia back about 5,000 years, to a time in Spain when women brewed the lightly carbonated drink as part of their daily routine, using a fermentation process similar to the one they used to make bread. ‘It was like a beer juice, compared to the beer made today,’ he says.”

The Roman Empire’s military was unable to conquer the ancient Spanish city of Numancia, between Madrid and Barcelona. Carlyon says before every battle the soldiers of Numancia got drunk on caelia

“contributing to the Romans’ view of them as fierce, wild fighters who successfully held off the invaders until the Romans wearied of the losses and reverted to building a wall around the fortified city in a siege. Finally, the Romans stopped fighting, closed them in and starved them, but it took two years.”

A pitcher from ancient Numancia. (

Ecelan/CC BY SA 4.0

)The Romans replaced the native beer culture with viniculture, but what goes around comes around. In 1550, when the Spanish began their incursions into the Americas they listed grapevines as a valuable commodity, not hops or barley, CSU says.

A pitcher from ancient Numancia. (

Ecelan/CC BY SA 4.0

)The Romans replaced the native beer culture with viniculture, but what goes around comes around. In 1550, when the Spanish began their incursions into the Americas they listed grapevines as a valuable commodity, not hops or barley, CSU says.

“The fact that they chose that reflected the culture of the time. In 1550, it had been more than 1,000 years since beer had been prevalent,” Carlyon said.

Archaeologist attempts to revive lost alcoholic beverages from ancient recipes and residues New Discovery Reveals Egyptians Brewed Beer 5,000 Years Ago in Israel The Modern Recreation of Ancient Sumerian Beer Proto-cuneiform recording the allocation of beer, probably from southern Iraq, Late Prehistoric period, about 3100-3000 BC (

Takomabibelot/ CC BY 2.0

)Other academics have been resurrecting ancient libations.

Proto-cuneiform recording the allocation of beer, probably from southern Iraq, Late Prehistoric period, about 3100-3000 BC (

Takomabibelot/ CC BY 2.0

)Other academics have been resurrecting ancient libations.

An archaeologist working with a brewery is recreating ancient beers from around the world, including Turkey, Egypt, Italy, Denmark, Honduras and China, Ancient Origins reported in 2015. Alcohol archaeologist Patrick McGovern thinks he may even be able to recreate a drink from Egypt that is 16,000 years old.

Professor McGovern, of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, has been working with Dogfish Head Brewery in Milton, Delaware. The professor is using modern technology to detect traces of ingredients. In addition, Dogfish Head Brewery has produced beer using African, South American, and Finnish recipes from centuries ago. For a list of the brews, see dogfish.com/ancientales.

It’s not just beer that archaeologists are trying to recreate. Ancient-Origins.net reported in 2013 that Italian archaeologists planted a vineyard near Catania in Sicily with the aim of making wine using techniques from classical Rome described in ancient texts. The team expected its first vintage within four years.

These attempts at drinking the spirits of ancestors go back quite a few years. There is a reference at thekeep.org about a 1996 attempt by Newcastle Breweries in Melbourne to brew an ancient Egyptian beer too.

The Herald-Sun reported that 'Tutankhamon Ale' will be based on sediment from jars found in a brewery housed in the Sun Temple of Nefertiti, and the team involved has gathered enough of the correct raw materials to produce just 1000 bottles of the ale,” Caroline Seawright wrote at thekeep.org. That beer was 5 to 6 percent alcohol and was sold at Harrods for £50 (about $100) a bottle. The profit was to go toward further research into Egyptian beer making.

Featured image: A glass of beer atop old barrels ( public domain ).

By Mark Miller

A Colorado State University professor says he wants to write a book on caelia—an ancient Spanish beer that was replaced by wine after the Roman Empire invaded Iberia. He also may collaborate with a brewery or the university’s prominent fermentation program to produce a batch of the old brew, which he calls “beer juice.”

A Colorado State University professor says he wants to write a book on caelia—an ancient Spanish beer that was replaced by wine after the Roman Empire invaded Iberia. He also may collaborate with a brewery or the university’s prominent fermentation program to produce a batch of the old brew, which he calls “beer juice.” But if you’re curious and you’re visiting Spain, some Spanish breweries have already resurrected the beverage, the origins of which date back at least 5,000 years.

Jonathan Carlyon, professor of languages and culture, has been studying the prehistoric Spanish beverage. His specialty at the university is early Hispanic literary culture. He knows a lot about Spanish history and its people’s reliance on caelia and beer until the Romans began making incursions in Hispania beginning around 218 BC and introduced wine, says a press release from Colorado State.

Some Spanish brewers already make caelia, but Professor Carlyon is considering asking a Fort Smith, Colorado, brewery or the university’s fermentation program to brew up a batch too. Apart from writing a paper or a book about the beverage, he expressed his interest in perhaps providing a class on the drink for the university’s fermentation students.

Ancient Monastery Recreates Beer Based on Historic Recipe by British Soldiers Medieval Monks of Bicester Drank 10 Pints of Beer a Week Beer was more important than bread for our Stone Age ancestors “Now beer is worthy of serious academic scholarship,” he is quoted in the press release. “We’re always trying to recruit students to take our courses and get our minor. The Languages, Literatures and Cultures lens can be used in almost any field.”

Colorado State University Professor Jonathan Carlyon with a bottle of caelia from a Spanish microbrewery (CSU photo) “The name Caelia, derived from the Latin verb for heating, ‘calefacere,’ was inspired by the heat used in the brewing process,” the release stated. “Carlyon has tracked the consumption of Caelia back about 5,000 years, to a time in Spain when women brewed the lightly carbonated drink as part of their daily routine, using a fermentation process similar to the one they used to make bread. ‘It was like a beer juice, compared to the beer made today,’ he says.”

Colorado State University Professor Jonathan Carlyon with a bottle of caelia from a Spanish microbrewery (CSU photo) “The name Caelia, derived from the Latin verb for heating, ‘calefacere,’ was inspired by the heat used in the brewing process,” the release stated. “Carlyon has tracked the consumption of Caelia back about 5,000 years, to a time in Spain when women brewed the lightly carbonated drink as part of their daily routine, using a fermentation process similar to the one they used to make bread. ‘It was like a beer juice, compared to the beer made today,’ he says.” The Roman Empire’s military was unable to conquer the ancient Spanish city of Numancia, between Madrid and Barcelona. Carlyon says before every battle the soldiers of Numancia got drunk on caelia

“contributing to the Romans’ view of them as fierce, wild fighters who successfully held off the invaders until the Romans wearied of the losses and reverted to building a wall around the fortified city in a siege. Finally, the Romans stopped fighting, closed them in and starved them, but it took two years.”

A pitcher from ancient Numancia. (

Ecelan/CC BY SA 4.0

)The Romans replaced the native beer culture with viniculture, but what goes around comes around. In 1550, when the Spanish began their incursions into the Americas they listed grapevines as a valuable commodity, not hops or barley, CSU says.

A pitcher from ancient Numancia. (

Ecelan/CC BY SA 4.0

)The Romans replaced the native beer culture with viniculture, but what goes around comes around. In 1550, when the Spanish began their incursions into the Americas they listed grapevines as a valuable commodity, not hops or barley, CSU says. “The fact that they chose that reflected the culture of the time. In 1550, it had been more than 1,000 years since beer had been prevalent,” Carlyon said.

Archaeologist attempts to revive lost alcoholic beverages from ancient recipes and residues New Discovery Reveals Egyptians Brewed Beer 5,000 Years Ago in Israel The Modern Recreation of Ancient Sumerian Beer

Proto-cuneiform recording the allocation of beer, probably from southern Iraq, Late Prehistoric period, about 3100-3000 BC (

Takomabibelot/ CC BY 2.0

)Other academics have been resurrecting ancient libations.

Proto-cuneiform recording the allocation of beer, probably from southern Iraq, Late Prehistoric period, about 3100-3000 BC (

Takomabibelot/ CC BY 2.0

)Other academics have been resurrecting ancient libations. An archaeologist working with a brewery is recreating ancient beers from around the world, including Turkey, Egypt, Italy, Denmark, Honduras and China, Ancient Origins reported in 2015. Alcohol archaeologist Patrick McGovern thinks he may even be able to recreate a drink from Egypt that is 16,000 years old.

Professor McGovern, of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, has been working with Dogfish Head Brewery in Milton, Delaware. The professor is using modern technology to detect traces of ingredients. In addition, Dogfish Head Brewery has produced beer using African, South American, and Finnish recipes from centuries ago. For a list of the brews, see dogfish.com/ancientales.

It’s not just beer that archaeologists are trying to recreate. Ancient-Origins.net reported in 2013 that Italian archaeologists planted a vineyard near Catania in Sicily with the aim of making wine using techniques from classical Rome described in ancient texts. The team expected its first vintage within four years.

These attempts at drinking the spirits of ancestors go back quite a few years. There is a reference at thekeep.org about a 1996 attempt by Newcastle Breweries in Melbourne to brew an ancient Egyptian beer too.

The Herald-Sun reported that 'Tutankhamon Ale' will be based on sediment from jars found in a brewery housed in the Sun Temple of Nefertiti, and the team involved has gathered enough of the correct raw materials to produce just 1000 bottles of the ale,” Caroline Seawright wrote at thekeep.org. That beer was 5 to 6 percent alcohol and was sold at Harrods for £50 (about $100) a bottle. The profit was to go toward further research into Egyptian beer making.

Featured image: A glass of beer atop old barrels ( public domain ).

By Mark Miller

Published on January 28, 2016 03:30

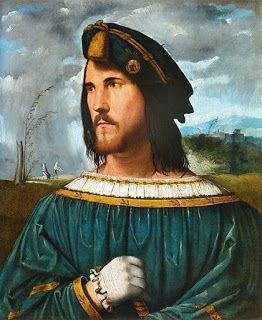

History Trivia - Cesare Borgia given as hostage to Charles VIII

January 28

1495 Pope Alexander VI gave his son Cesare Borgia as a hostage to Charles VIII of France to ensure the Pope's good behavior as Charles left Rome to conquer Naples. However, Cesare did escape and returned to Rome.

1495 Pope Alexander VI gave his son Cesare Borgia as a hostage to Charles VIII of France to ensure the Pope's good behavior as Charles left Rome to conquer Naples. However, Cesare did escape and returned to Rome.

Published on January 28, 2016 00:30

January 27, 2016

A brief history of camouflage

History Extra

Commandos take part in basic training exercises in an unspecified spot in England, 1940. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Commandos take part in basic training exercises in an unspecified spot in England, 1940. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Camouflage is a pattern of paradox. Camouflage’s history encompasses both hiding but also being seen: confusing the eye, subverting reality and signalling both individuality and group affinities…

1) Camouflage in nature Any history of camouflage must properly start with ‘mother nature’. From wood ants to pufferfish and octopi to birds, a wide array of animals conceal themselves – sometimes amazingly, like this camouflaged octopus – from predators with camouflage.

Two British zoologists and an American painter played key roles in translating camouflage in nature into techniques humans could put to military use. One of those zoologists, Sir Edward Poulton, wrote the first book on camouflage in 1890 (The Colours of Animals). An early adherent of Darwinism, Poulton believed that animal mimicry (imitation) for concealment was proof of natural selection.

The American painter Abbott Thayer popularised two particular concepts of camouflage: countershading explains the lighter underbellies common to many animals – this cancels out shadowing from the overhead sun, giving the animal a flat, two-dimensional appearance. Disruptive coloration, meanwhile, refers to ‘splotchiness’ in an animal’s colouring; this visual effect helps to obscure the contours of its body.

Thayer suffered from bipolar disorder and panic attacks – conditions not helped by public criticism of his controversial theories, which gained prominence in the lead-up to the First World War. Thayer defended those theories stoutly until his death in 1921.

In 1940, zoologist Hugh Cott built on Poulton’s more scientific concepts with ideas of his own, including contour obliteration – basically, making it difficult to perceive a continuous form by blurring its defining edges - and shadow elimination – as the name suggests, reducing the appearance of telltale shadows.

2) Military khakiPrior to the invention of the modern rifle in the mid-1800s (the earliest rifles were in use during the 15th century), militaries the world over clad their soldiers in bright shades of colour – consider, for example, British troops in their iconic madder red uniforms (red coats).

Soldiers of the 30th East Lancashire foot regiment in bright red jackets, c1850. Rischgitz Collection. (Photo by Rischgitz/Getty Images)

But marksmen began wearing more inconspicuous garb to conceal themselves while picking off targets. Austrian Jägers (meaning ‘hunters’) wore light grey, while the British 95th Rifle Regiment wore dun green.

Military khaki (the term derives from the Urdu and Persian words for ‘dust’) arose in the mid-19th century, as soldiers in the British Indian Army began dyeing their white uniforms with tea and curry. Not only did khaki end the hopeless struggle to keep one’s uniform spanking white, it also reduced soldiers’ visibility from a distance.

Despite this, brighter military garb tended to dominate until the early 20th century. Why were militaries so reluctant to adopt darker uniforms? The answer lay in the evolving nature of warfare: in addition to practical considerations like durability and visibility, uniforms performed a psychological function of making soldiers feel battle-ready. Orderly lines of brightly clad soldiers marching in formation – a key feature of musket-driven warfare – gave way to guerrilla warfare. To fight and win in this new era, stealth was a core advantage.

3) The First World WarA new threat darkened the horizon in the run-up to the First World War: enemy aerial reconnaissance. (Aerial attack became possible somewhat later.) As such, militaries first used camouflage patterning and tactics to hide, not people, but locations and equipment.

The French organised the first units of camoufleurs – specialists in camouflage – in around 1914. Initial tactics were confined to painting vehicles and weaponry in disruptive patterns to blend into the surrounding landscape. Camoufleurs were both practitioners and teachers of their peculiar art. They taught other military units how to disguise their equipment with paint, to toss netting interwoven with fake leaves over a shed stocked with materiél (military equipment) and to erase any telltale truck tracks and cannon blast marks.

French soldiers at a wooden building with military camouflage, Western Front, Soissons, Aisne, France, 1917. Colour photo (Autochrome Lumière) by Fernand Cuville (1887–1927). (Photo by Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images)

The term ‘camouflage’ itself dates to a practical joke from 16th-century France. The prankster would fashion a camouflet – a hollow paper cone, lit to smoulder at one end – and stick it under an unfortunate sleeper’s nose. The sleeper would jolt rudely awake at the first lungful of smoke.

Camouflet later referred to a lethal powder charge that could entrap a tunnelling enemy troop underground – a more deadly trick. To complete this layered etymology, the French verb camoufler means, appropriately, ‘to make oneself up for the stage’.

4) Camouflage goes BaroqueCamouflage techniques grew increasingly detailed as the First World War progressed, and fascination with camouflage – in popular as well as military circles – grew. Factories cranked out pâpier-maché heads by the thousands; mounted on sticks – soldiers might poke these decoys above the trench line, tempting the enemy out of his safe foxhole to fire. False trees were equally popular: regiments would sneak onto the battlefield unseen at night, fell an actual tree, then replace it with a hollowed-out replica with a soldier hidden inside.

Camouflage spread to the seas, too. In 1917, British lieutenant Norman Wilkinson introduced the concept of ‘dazzle’-painting warships to curb losses: mostly black-and-white-zigzagged ‘dazzle’ paint was supposed to throw off the enemy’s calculations of a ship’s size, speed and distance, making an accurate hit more difficult. German U-boats sank 23 British ships weekly that year, 55 in one week of April 1917 alone. ‘Dazzle-mania’ subsequently spread among Allied navies, although its actual effectiveness was never proven.

A Royal Navy cruiser painted in dazzle camouflage in the Dardanelles, 1915. Original publication: The Illustrated War News, 26 May 1915. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

5) The Second World WarAs mentioned above, evidence that camouflage actually worked was patchy. However, as the world marched towards the Second World War, the fresh threat of aerial attack prompted militaries on both sides to use camouflage more widely. With the exception of dazzle, all First World War-era camouflage tactics were revived and expanded. Military literature of the period is awash with camouflage training manuals aimed at every soldier, from callow privates to top brass.

Two Allied wins during the Second World War owed their success largely to camouflage: El Alamein in 1942, and D-Day in 1944. During the second battle of El Alamein, the Allies blocked the Germans from seizing the Suez Canal with a mind-bogglingly detailed camouflage-plan involving inflatable tanks, fake artillery blasts and – extraordinarily – hiding the entire Suez Canal from aerial view. This was the masterwork of British camoufleur and stage magician Jasper Maskelyne.

Home Guards smear on green paint and attach camouflage to each other during a camouflage training course at Fieldcraft School in South-Eastern Command, January 1942. (Photo by Harry Todd/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Prior to D-Day, the Allies staged a false build-up of troops in Scotland and Kent, while hiding their true efforts to amass troops to storm Normandy. The ruse continued once they landed in France with the ‘Ghost Army’ – a sham-army standing in for the actual US battalion rushing the Normandy beaches.

6) Post-Second World WarThe Second World War saw the rise of mechanical printed patterns onto fabric, bringing the distinctive variations of pattern into sharper focus. Each nation had not one, but several unique camouflage patterns, with different versions matched to the battle landscape (snow, desert, jungle, forest). Who wore which camouflage pattern revealed colonial relationships, shifting alliances and other practical considerations (like how disastrously similar your army’s camouflage was to your latest enemy’s).

Camouflage infiltrated popular culture during both world wars – from ladies’ ‘slimming’ dress wear to the clever war paint of makeup. Consider these lyrics from the 1917 song ‘Camouflage Nut Song No. 2’ by L Wolfe Gilbert and Anatol Friedland:

Camouflage, Camouflage, that's the latest dodge,

Camouflage, Camouflage, it's not a cheese or lodge,

You buy a Ford that's second-hand,

You paint it red, it looks so grand.

And near a "Stutz" you let it stand –

that's Camouflage.

7) Modern camouflageCamouflage today permeates civilian culture: it features in designs for women’s clothing from the likes of Jean Paul Gaultier, Prabal Gurung and Patrik Ervell (among many others), and musicians wearing camouflage can signal their commitment to some form of political activism – from black power (Public Enemy) to African rights (U2).

Visual artists have taken to camouflage with zeal, too. Andy Warhol’s Camouflage Self-Portrait (1986) hit the art scene at the height of the Cold War, a time of near-constant warfare that, confusingly, rarely officially declared itself as such.

A woman walks past the painting 'Camouflage Self-Portrait' by US artist Andy Warhol during a preview of Sotheby's autumn sales of contemporary art in New York, 2 November 2007. (Photo by Emmanuel Dunand/AFP/Getty Images)

Like all technology, camouflage evolves. High-tech camouflage can now conceal body heat from enemy sensors or harness fibre-optics to match a fabric dynamically to its surroundings. Technologists are progressing towards a camouflage that bends light waves to render objects – or even people – invisible, just like Harry Potter’s invisibility cloak.

Jude Stewart is the author of two books, Patternalia: An Unconventional History of Polka Dots, Stripes, Plaid, Camouflage, & Other Graphic Patterns (Bloomsbury USA, 2015) and ROY G. BIV: An Exceedingly Surprising Book About Color (Bloomsbury USA, 2013).

Jude writes about design and culture for Slate, Fast Company, and The Believer, among others, and blogs about design for Print. You can follow her on Twitter @joodstew.

Commandos take part in basic training exercises in an unspecified spot in England, 1940. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Commandos take part in basic training exercises in an unspecified spot in England, 1940. (Photo by Fox Photos/Getty Images) Camouflage is a pattern of paradox. Camouflage’s history encompasses both hiding but also being seen: confusing the eye, subverting reality and signalling both individuality and group affinities…

1) Camouflage in nature Any history of camouflage must properly start with ‘mother nature’. From wood ants to pufferfish and octopi to birds, a wide array of animals conceal themselves – sometimes amazingly, like this camouflaged octopus – from predators with camouflage.

Two British zoologists and an American painter played key roles in translating camouflage in nature into techniques humans could put to military use. One of those zoologists, Sir Edward Poulton, wrote the first book on camouflage in 1890 (The Colours of Animals). An early adherent of Darwinism, Poulton believed that animal mimicry (imitation) for concealment was proof of natural selection.

The American painter Abbott Thayer popularised two particular concepts of camouflage: countershading explains the lighter underbellies common to many animals – this cancels out shadowing from the overhead sun, giving the animal a flat, two-dimensional appearance. Disruptive coloration, meanwhile, refers to ‘splotchiness’ in an animal’s colouring; this visual effect helps to obscure the contours of its body.

Thayer suffered from bipolar disorder and panic attacks – conditions not helped by public criticism of his controversial theories, which gained prominence in the lead-up to the First World War. Thayer defended those theories stoutly until his death in 1921.

In 1940, zoologist Hugh Cott built on Poulton’s more scientific concepts with ideas of his own, including contour obliteration – basically, making it difficult to perceive a continuous form by blurring its defining edges - and shadow elimination – as the name suggests, reducing the appearance of telltale shadows.

2) Military khakiPrior to the invention of the modern rifle in the mid-1800s (the earliest rifles were in use during the 15th century), militaries the world over clad their soldiers in bright shades of colour – consider, for example, British troops in their iconic madder red uniforms (red coats).

Soldiers of the 30th East Lancashire foot regiment in bright red jackets, c1850. Rischgitz Collection. (Photo by Rischgitz/Getty Images)

But marksmen began wearing more inconspicuous garb to conceal themselves while picking off targets. Austrian Jägers (meaning ‘hunters’) wore light grey, while the British 95th Rifle Regiment wore dun green.

Military khaki (the term derives from the Urdu and Persian words for ‘dust’) arose in the mid-19th century, as soldiers in the British Indian Army began dyeing their white uniforms with tea and curry. Not only did khaki end the hopeless struggle to keep one’s uniform spanking white, it also reduced soldiers’ visibility from a distance.

Despite this, brighter military garb tended to dominate until the early 20th century. Why were militaries so reluctant to adopt darker uniforms? The answer lay in the evolving nature of warfare: in addition to practical considerations like durability and visibility, uniforms performed a psychological function of making soldiers feel battle-ready. Orderly lines of brightly clad soldiers marching in formation – a key feature of musket-driven warfare – gave way to guerrilla warfare. To fight and win in this new era, stealth was a core advantage.

3) The First World WarA new threat darkened the horizon in the run-up to the First World War: enemy aerial reconnaissance. (Aerial attack became possible somewhat later.) As such, militaries first used camouflage patterning and tactics to hide, not people, but locations and equipment.

The French organised the first units of camoufleurs – specialists in camouflage – in around 1914. Initial tactics were confined to painting vehicles and weaponry in disruptive patterns to blend into the surrounding landscape. Camoufleurs were both practitioners and teachers of their peculiar art. They taught other military units how to disguise their equipment with paint, to toss netting interwoven with fake leaves over a shed stocked with materiél (military equipment) and to erase any telltale truck tracks and cannon blast marks.

French soldiers at a wooden building with military camouflage, Western Front, Soissons, Aisne, France, 1917. Colour photo (Autochrome Lumière) by Fernand Cuville (1887–1927). (Photo by Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images)

The term ‘camouflage’ itself dates to a practical joke from 16th-century France. The prankster would fashion a camouflet – a hollow paper cone, lit to smoulder at one end – and stick it under an unfortunate sleeper’s nose. The sleeper would jolt rudely awake at the first lungful of smoke.

Camouflet later referred to a lethal powder charge that could entrap a tunnelling enemy troop underground – a more deadly trick. To complete this layered etymology, the French verb camoufler means, appropriately, ‘to make oneself up for the stage’.

4) Camouflage goes BaroqueCamouflage techniques grew increasingly detailed as the First World War progressed, and fascination with camouflage – in popular as well as military circles – grew. Factories cranked out pâpier-maché heads by the thousands; mounted on sticks – soldiers might poke these decoys above the trench line, tempting the enemy out of his safe foxhole to fire. False trees were equally popular: regiments would sneak onto the battlefield unseen at night, fell an actual tree, then replace it with a hollowed-out replica with a soldier hidden inside.

Camouflage spread to the seas, too. In 1917, British lieutenant Norman Wilkinson introduced the concept of ‘dazzle’-painting warships to curb losses: mostly black-and-white-zigzagged ‘dazzle’ paint was supposed to throw off the enemy’s calculations of a ship’s size, speed and distance, making an accurate hit more difficult. German U-boats sank 23 British ships weekly that year, 55 in one week of April 1917 alone. ‘Dazzle-mania’ subsequently spread among Allied navies, although its actual effectiveness was never proven.

A Royal Navy cruiser painted in dazzle camouflage in the Dardanelles, 1915. Original publication: The Illustrated War News, 26 May 1915. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

5) The Second World WarAs mentioned above, evidence that camouflage actually worked was patchy. However, as the world marched towards the Second World War, the fresh threat of aerial attack prompted militaries on both sides to use camouflage more widely. With the exception of dazzle, all First World War-era camouflage tactics were revived and expanded. Military literature of the period is awash with camouflage training manuals aimed at every soldier, from callow privates to top brass.

Two Allied wins during the Second World War owed their success largely to camouflage: El Alamein in 1942, and D-Day in 1944. During the second battle of El Alamein, the Allies blocked the Germans from seizing the Suez Canal with a mind-bogglingly detailed camouflage-plan involving inflatable tanks, fake artillery blasts and – extraordinarily – hiding the entire Suez Canal from aerial view. This was the masterwork of British camoufleur and stage magician Jasper Maskelyne.

Home Guards smear on green paint and attach camouflage to each other during a camouflage training course at Fieldcraft School in South-Eastern Command, January 1942. (Photo by Harry Todd/Fox Photos/Getty Images)

Prior to D-Day, the Allies staged a false build-up of troops in Scotland and Kent, while hiding their true efforts to amass troops to storm Normandy. The ruse continued once they landed in France with the ‘Ghost Army’ – a sham-army standing in for the actual US battalion rushing the Normandy beaches.

6) Post-Second World WarThe Second World War saw the rise of mechanical printed patterns onto fabric, bringing the distinctive variations of pattern into sharper focus. Each nation had not one, but several unique camouflage patterns, with different versions matched to the battle landscape (snow, desert, jungle, forest). Who wore which camouflage pattern revealed colonial relationships, shifting alliances and other practical considerations (like how disastrously similar your army’s camouflage was to your latest enemy’s).

Camouflage infiltrated popular culture during both world wars – from ladies’ ‘slimming’ dress wear to the clever war paint of makeup. Consider these lyrics from the 1917 song ‘Camouflage Nut Song No. 2’ by L Wolfe Gilbert and Anatol Friedland:

Camouflage, Camouflage, that's the latest dodge,

Camouflage, Camouflage, it's not a cheese or lodge,

You buy a Ford that's second-hand,

You paint it red, it looks so grand.

And near a "Stutz" you let it stand –

that's Camouflage.

7) Modern camouflageCamouflage today permeates civilian culture: it features in designs for women’s clothing from the likes of Jean Paul Gaultier, Prabal Gurung and Patrik Ervell (among many others), and musicians wearing camouflage can signal their commitment to some form of political activism – from black power (Public Enemy) to African rights (U2).

Visual artists have taken to camouflage with zeal, too. Andy Warhol’s Camouflage Self-Portrait (1986) hit the art scene at the height of the Cold War, a time of near-constant warfare that, confusingly, rarely officially declared itself as such.

A woman walks past the painting 'Camouflage Self-Portrait' by US artist Andy Warhol during a preview of Sotheby's autumn sales of contemporary art in New York, 2 November 2007. (Photo by Emmanuel Dunand/AFP/Getty Images)

Like all technology, camouflage evolves. High-tech camouflage can now conceal body heat from enemy sensors or harness fibre-optics to match a fabric dynamically to its surroundings. Technologists are progressing towards a camouflage that bends light waves to render objects – or even people – invisible, just like Harry Potter’s invisibility cloak.

Jude Stewart is the author of two books, Patternalia: An Unconventional History of Polka Dots, Stripes, Plaid, Camouflage, & Other Graphic Patterns (Bloomsbury USA, 2015) and ROY G. BIV: An Exceedingly Surprising Book About Color (Bloomsbury USA, 2013).

Jude writes about design and culture for Slate, Fast Company, and The Believer, among others, and blogs about design for Print. You can follow her on Twitter @joodstew.

Published on January 27, 2016 03:30

History Trivia - Guy Fawkes trial begins

January 27

1606 Gunpowder Plot: The trial of Guy Fawkes and other conspirators began, ending with their execution on January 31.

1606 Gunpowder Plot: The trial of Guy Fawkes and other conspirators began, ending with their execution on January 31.

Published on January 27, 2016 01:00