MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 129

December 18, 2015

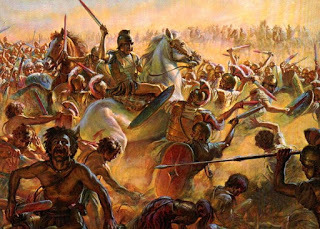

History Trivia - Battle of the Trebbia – Hannibal victorious

December 18

218 BC Second Punic War: Battle of the Trebbia – Hannibal's Carthaginian forces defeated those of the Roman Republic.

1118 Afonso the Battler, the Christian King of Aragon captured Saragossa, Spain, causing a major blow to Muslim Spain.

1352 Innocent VI became Pope. He introduced many needed reforms in the administration of church affairs and also sought to restore order in Rome, where, in 1355, Charles IV (1346–78) was crowned Holy Roman Emperor with his permission, after previously having made an oath that he would quit the city on the day of the ceremony.

218 BC Second Punic War: Battle of the Trebbia – Hannibal's Carthaginian forces defeated those of the Roman Republic.

1118 Afonso the Battler, the Christian King of Aragon captured Saragossa, Spain, causing a major blow to Muslim Spain.

1352 Innocent VI became Pope. He introduced many needed reforms in the administration of church affairs and also sought to restore order in Rome, where, in 1355, Charles IV (1346–78) was crowned Holy Roman Emperor with his permission, after previously having made an oath that he would quit the city on the day of the ceremony.

Published on December 18, 2015 01:30

December 17, 2015

Mr. Chuckles bumps into Toi Thomas while stirring the Wizard's Cauldron

The Wizard speaks:

The Wizard speaks:In the last Wizard's Cauldron interview of 2015, old friend of the site, Toi Thomas talks to me about a new direction she's taking. We've been talking for years on and off and I'm delighted to be given the opportunity to interview her once more.

Toi is better known as a popular fantasy author (the Eternal Curse Series), but this year, she has written her first chicklit novel under a pseudonym.

I caught up with Toi in the not-so snowy wastes of Williamsburg, Virginia (thanks to El Nino!) and asked her to tell us all about it: Here's what she had to say.

Read more here

Published on December 17, 2015 04:45

Lady Jane Grey: why do we want to believe the myth?

History Extra

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833) by French Romantic painter Paul Delaroche dominates its display room at the National Gallery in London. © National Gallery

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833) by French Romantic painter Paul Delaroche dominates its display room at the National Gallery in London. © National Gallery

The teenage queen, Lady Jane Grey, has been mythologised, even fetishised, as the innocent victim of adult ambition. The legend was encapsulated by the French Romantic artist Paul Delaroche in his 1833 historical portrait of Jane in white on the scaffold, an image with all the erotic overtones of a virgin sacrifice. But the legend also inspired a fraud, one that has fooled historians, art experts, and biographers, for over 100 years.

A 16th-century merchant gave us what was believed, until now, to be the only detailed, contemporary description of Jane’s appearance. In a letter, he wrote an eyewitness account of a smiling, red-haired girl, being processed to the Tower as queen, on 10 July 1553. He was close enough to see that she was so small she had to wear stacked shoes or ‘chopines’ to give her height. Jane was overthrown nine days later, and, eventually, executed in the Tower from where she had reigned. But while the tragedy of her brutal death, at only 16, is real, the letter is an invention that obscures the significance of her reign.

The faked letter first made its appearance in Richard Patrick Boyle Davey’s 1909 biography The Nine Days Queen, Lady Jane Grey & her Times. Davey’s subject was already a popular one. The Victorians had lapped up the poignant tale of a child-woman forced to be queen, and despite this, later executed as a usurper. The letter, ‘discovered’ by Davey in the archives of Genoa, seemingly brought this tragic heroine to life. But in retrospect that should have sent alarm bells ringing, for the Jane the Victorians knew was already heavily fictionalised.

The historical Jane was a great grandchild of Henry VII. Highly intelligent and given a top flight Protestant education, she might have made a queen consort to her fiercely Protestant cousin Edward VI, as her father hoped. But instead, on 6 July 1553, the dying Edward bequeathed her the throne, in place of his Catholic half sister, Mary Tudor. Mary overthrew Jane 13 days later, and she was duly tried for treason, found guilty and condemned.

Queen Mary I. © Bridgeman

Mary indicated she wished to pardon Jane. But Jane was executed, nevertheless, the following year. It was the aftermath to a rebellion in which she had played no part (although her father had). Why then did Mary sign Jane’s death warrant? The reason was indicated the day before Jane’s beheading. The bishop of Winchester, Stephen Gardiner, reminded Mary it was leading Protestants who had opposed her rule in July 1553, and in the recent rebellion. Jane, who had condemned Catholicism as queen, had continued to do so as a prisoner in the Tower. As such she posed a threat. It was for her religious stance that Jane would die, not solely for her father’s actions, or her reign as a usurper.

Aware that the Protestant cause would be damaged by its link to treason, Jane reminded people from the scaffold that while in law she was a traitor, she had merely accepted the throne she was offered, and was innocent of having sought it. From this kernel of truth the later image of Jane was spun. Protestant propagandists developed her claims to innocence, ascribing the events of 1553 to the personal ambitions of Jane’s father and father-in-law, rather than religion. Under Queen Elizabeth, treason was associated with Catholics, not Protestants, and the earlier history was forgotten.

The religious issue of 1553 concluded only in 1701, when it was made illegal for any Catholic to inherit the throne: a law that still stands. But Jane’s story continued to develop. Her ‘innocence’ was associated increasingly with the passivity deemed appropriate in a young girl. The sexual dimension to this is evident in Edward’s Young’s 1714 poem, The Force of Religion, which invited men to gaze as voyeurs on the pure Jane in her ‘private closet’. Jane’s mother, Frances, meanwhile, was reinvented as a wicked queen to Jane’s Snow White.

By the 19th century Jane’s fictionalised life was enormously popular. But there was something still missing from her story: a face. With no contemporary images or descriptions, the public had to be content with Jane as imagined by artists. The most striking work remains Paul Delaroche’s portrait, The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, bequeathed to the nation by Lord Cheylesmore in 1902 (and now part of a major exhibition at the National Gallery). Jane, blindfold, and feeling for the block, represents an apotheosis of female helplessness. Richard Davey seems to have spotted a need for an account of Jane’s appearance that matches its power. He claimed to have found it in a letter in Genoa, composed by the merchant, ‘Sir Baptist Spinola’.

Lady Jane Grey, seen here in a Victorian illustration, was a doomed teenage queen. © Bridgeman

The letter has been quoted in biographies ever since and used to argue the merits of ‘lost’ portraits of Jane. But I was concerned that Davey was the sole source for this letter. Researching my triple biography, The Sisters Who Would be Queen, I had discovered that Davey had invented evidence that Jane had a nanny and dresser with her in the Tower: characters inspired by earlier novels. I began a long search for the ‘Spinola’ letter, but never found it in Genoa or in any history predating 1909. And it became clear the letter is a fake that mixes details from contemporary sources with fiction.

There was a contemporary merchant called Benedict Spinola and a soldier called Baptista Spinola. The description of Jane has echoes of the red-lipped girl in the Delaroche portrait, but resembles also a contemporary description of Mary Tudor, who was “of low stature… very thin; and her hair reddish”. Jane’s mother carries her train in the letter, as was observed in 1553. The platform shoes or ‘chopines’ were taken from the Victorian historian Agnes Strickland, quoting Isaac D’Israeli. I can find no earlier source. But they are suggestive of Jane’s physical vulnerability: an element in the appeal of the abused child woman that remains so popular (we even find Jane raped in a recent novel).

The rest of Jane’s dress, described by Spinola as a gown of green velvet worn with a white headdress, was in colours traditionally worn by a monarch on the eve of their coronation. But they are also the colours of the illustration, Lady Jane Grey in Royal Robes, published in Ardern Holt’s 1882 Fancy Dresses Described. Significantly, in Davey’s The Tower of London, published in 1910, he describes Jane’s dress as edged in ermine, as it was in Holt’s illustration: a detail overlooked by ‘Sir Baptist Spinola’.

Davey’s lies and the repetition of old myths are damaging. Because Jane’s reign was treated for so long as the product of the ambitions of a few men, or of Edward VI’s naïve hopes, it is regarded as a brief hiatus, of no consequence. But it is key to understanding the development of our constitutional history. And we have overlooked something else. The Tudor unease with women who hold power has never really gone away. In legend Jane is the good girl: weak and feminine; Frances is a bad woman: powerful and mannish. This is the lesson of the myths – one that historians have too willingly accepted.

Leanda de Lisle is a bestselling author. Her book The Sisters Who Would be Queen is out now.

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833) by French Romantic painter Paul Delaroche dominates its display room at the National Gallery in London. © National Gallery

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833) by French Romantic painter Paul Delaroche dominates its display room at the National Gallery in London. © National Gallery The teenage queen, Lady Jane Grey, has been mythologised, even fetishised, as the innocent victim of adult ambition. The legend was encapsulated by the French Romantic artist Paul Delaroche in his 1833 historical portrait of Jane in white on the scaffold, an image with all the erotic overtones of a virgin sacrifice. But the legend also inspired a fraud, one that has fooled historians, art experts, and biographers, for over 100 years.

A 16th-century merchant gave us what was believed, until now, to be the only detailed, contemporary description of Jane’s appearance. In a letter, he wrote an eyewitness account of a smiling, red-haired girl, being processed to the Tower as queen, on 10 July 1553. He was close enough to see that she was so small she had to wear stacked shoes or ‘chopines’ to give her height. Jane was overthrown nine days later, and, eventually, executed in the Tower from where she had reigned. But while the tragedy of her brutal death, at only 16, is real, the letter is an invention that obscures the significance of her reign.

The faked letter first made its appearance in Richard Patrick Boyle Davey’s 1909 biography The Nine Days Queen, Lady Jane Grey & her Times. Davey’s subject was already a popular one. The Victorians had lapped up the poignant tale of a child-woman forced to be queen, and despite this, later executed as a usurper. The letter, ‘discovered’ by Davey in the archives of Genoa, seemingly brought this tragic heroine to life. But in retrospect that should have sent alarm bells ringing, for the Jane the Victorians knew was already heavily fictionalised.

The historical Jane was a great grandchild of Henry VII. Highly intelligent and given a top flight Protestant education, she might have made a queen consort to her fiercely Protestant cousin Edward VI, as her father hoped. But instead, on 6 July 1553, the dying Edward bequeathed her the throne, in place of his Catholic half sister, Mary Tudor. Mary overthrew Jane 13 days later, and she was duly tried for treason, found guilty and condemned.

Queen Mary I. © Bridgeman

Mary indicated she wished to pardon Jane. But Jane was executed, nevertheless, the following year. It was the aftermath to a rebellion in which she had played no part (although her father had). Why then did Mary sign Jane’s death warrant? The reason was indicated the day before Jane’s beheading. The bishop of Winchester, Stephen Gardiner, reminded Mary it was leading Protestants who had opposed her rule in July 1553, and in the recent rebellion. Jane, who had condemned Catholicism as queen, had continued to do so as a prisoner in the Tower. As such she posed a threat. It was for her religious stance that Jane would die, not solely for her father’s actions, or her reign as a usurper.

Aware that the Protestant cause would be damaged by its link to treason, Jane reminded people from the scaffold that while in law she was a traitor, she had merely accepted the throne she was offered, and was innocent of having sought it. From this kernel of truth the later image of Jane was spun. Protestant propagandists developed her claims to innocence, ascribing the events of 1553 to the personal ambitions of Jane’s father and father-in-law, rather than religion. Under Queen Elizabeth, treason was associated with Catholics, not Protestants, and the earlier history was forgotten.

The religious issue of 1553 concluded only in 1701, when it was made illegal for any Catholic to inherit the throne: a law that still stands. But Jane’s story continued to develop. Her ‘innocence’ was associated increasingly with the passivity deemed appropriate in a young girl. The sexual dimension to this is evident in Edward’s Young’s 1714 poem, The Force of Religion, which invited men to gaze as voyeurs on the pure Jane in her ‘private closet’. Jane’s mother, Frances, meanwhile, was reinvented as a wicked queen to Jane’s Snow White.

By the 19th century Jane’s fictionalised life was enormously popular. But there was something still missing from her story: a face. With no contemporary images or descriptions, the public had to be content with Jane as imagined by artists. The most striking work remains Paul Delaroche’s portrait, The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, bequeathed to the nation by Lord Cheylesmore in 1902 (and now part of a major exhibition at the National Gallery). Jane, blindfold, and feeling for the block, represents an apotheosis of female helplessness. Richard Davey seems to have spotted a need for an account of Jane’s appearance that matches its power. He claimed to have found it in a letter in Genoa, composed by the merchant, ‘Sir Baptist Spinola’.

Lady Jane Grey, seen here in a Victorian illustration, was a doomed teenage queen. © Bridgeman

The letter has been quoted in biographies ever since and used to argue the merits of ‘lost’ portraits of Jane. But I was concerned that Davey was the sole source for this letter. Researching my triple biography, The Sisters Who Would be Queen, I had discovered that Davey had invented evidence that Jane had a nanny and dresser with her in the Tower: characters inspired by earlier novels. I began a long search for the ‘Spinola’ letter, but never found it in Genoa or in any history predating 1909. And it became clear the letter is a fake that mixes details from contemporary sources with fiction.

There was a contemporary merchant called Benedict Spinola and a soldier called Baptista Spinola. The description of Jane has echoes of the red-lipped girl in the Delaroche portrait, but resembles also a contemporary description of Mary Tudor, who was “of low stature… very thin; and her hair reddish”. Jane’s mother carries her train in the letter, as was observed in 1553. The platform shoes or ‘chopines’ were taken from the Victorian historian Agnes Strickland, quoting Isaac D’Israeli. I can find no earlier source. But they are suggestive of Jane’s physical vulnerability: an element in the appeal of the abused child woman that remains so popular (we even find Jane raped in a recent novel).

The rest of Jane’s dress, described by Spinola as a gown of green velvet worn with a white headdress, was in colours traditionally worn by a monarch on the eve of their coronation. But they are also the colours of the illustration, Lady Jane Grey in Royal Robes, published in Ardern Holt’s 1882 Fancy Dresses Described. Significantly, in Davey’s The Tower of London, published in 1910, he describes Jane’s dress as edged in ermine, as it was in Holt’s illustration: a detail overlooked by ‘Sir Baptist Spinola’.

Davey’s lies and the repetition of old myths are damaging. Because Jane’s reign was treated for so long as the product of the ambitions of a few men, or of Edward VI’s naïve hopes, it is regarded as a brief hiatus, of no consequence. But it is key to understanding the development of our constitutional history. And we have overlooked something else. The Tudor unease with women who hold power has never really gone away. In legend Jane is the good girl: weak and feminine; Frances is a bad woman: powerful and mannish. This is the lesson of the myths – one that historians have too willingly accepted.

Leanda de Lisle is a bestselling author. Her book The Sisters Who Would be Queen is out now.

Published on December 17, 2015 03:00

History Trivia - Henry VIII of England excommunicated

December 17

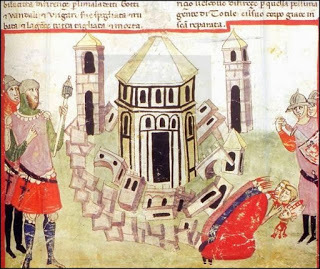

546 Gothic War: The Ostrogoths of King Totila conquered Rome by bribing the Byzantine garrison.

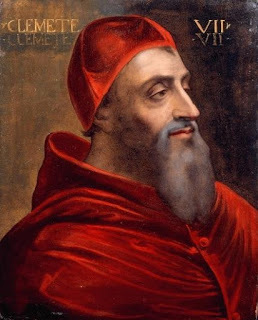

1531 Pope Clement VII established a parallel body to the Inquisition in Lisbon, Portugal.

1538 Pope Paul III excommunicated Henry VIII of England.

546 Gothic War: The Ostrogoths of King Totila conquered Rome by bribing the Byzantine garrison.

1531 Pope Clement VII established a parallel body to the Inquisition in Lisbon, Portugal.

1538 Pope Paul III excommunicated Henry VIII of England.

Published on December 17, 2015 02:30

December 16, 2015

Love, health and the weather: 9 things medieval Londoners worried about

History Extra

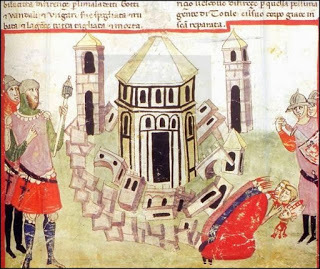

12th-century English illustration of men in prison and in stocks. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

12th-century English illustration of men in prison and in stocks. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

Here, Toni Mount, the author of Everyday Life in Medieval London: From the Anglo-Saxons to the Tudors reveals nine of the most pressing concerns of people living in the capital in the Middle Ages…

1) HealthPeople have always had concerns about health, be it their own or that of loved ones or neighbours – after all, in the medieval period a sickness might be contagious, and even a splinter could turn septic and prove deadly.

Living in the days before antibiotics, medieval folk had far more than us to worry about. Even a visit to the apothecary – the medieval pharmacist – brought concerns of its own: were the medicines for sale really as described?

The adulteration of medicines was a serious matter in the Middle Ages, and the Lord Mayor of London charged the Grocers’ Company with the task of making certain that no goods went on sale before they were ‘garbled’ (checked for purity and quality). During an inspection in 1475, the apothecary John Davy was pilloried, imprisoned and fined for selling ‘sanders’ (sandalwood), which was nothing more than his own “fabricated powder”.

Other strange and revolting imports included a cask containing ‘putrid wolves’, which William of Lothbury claimed could cure ‘the wolf’ disease. Physicians were asked to look into the matter, but since they could find no such disease in their medical books to require such a remedy, William was fined severely and the goods destroyed.

2) CrimeCrime was as much a worry for medieval Londoners as it is for us today, but whereas we have a police force to deal with such matters, back then there were only the beadles – one for each city ward and a couple of constables to assist him.

Here is an example of this trio in action: in 1474, the beadle of the ward of Farringdon suspected that Joan Salman and Walter Haydon – neither of them wedded – were alone together in a house near the Old Bailey. With two burly constables, the beadle approached the house. The door wasn’t locked, so the beadle and one constable went in, leaving the other at the door to prevent the couple making their escape.

They crept up the stairs to the bedchamber and caught Walter in bed with Joan – “a loose, immoral woman”. The pair were arrested and taken to the Counter (the sheriff’s prison).

In the event of a crime, whoever discovered it first was obliged to “raise the hue and cry” by shouting, banging on doors or clattering pots and pans; rousing the neighbours or anyone within earshot. The idea was that they should all give chase and apprehend the culprit. Only small children, the sick or the lame were excused from taking up the pursuit if they heard the cries of alarm. Otherwise, under a statute of 1275, they were considered to be aiding and abetting the criminal, and could find themselves under arrest. However, if someone raised the hue and cry unnecessarily, they would have to pay a fine.

After curfew, burglary was common in London, despite it being a capital crime. Shops and private houses could be robbed of jewellery, cloth, shoes and blades – anything that might turn a profit. In 1502, a man was arrested in Cornhill for being a “steler of pypes and gutters of lede by means of cutting of theym by nyghtes time”.

3) The weatherThe weather was always a hot topic of conversation in medieval London, and in 1089 there was a lot to talk about: in August, there was an earthquake “over all England”, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Then in November came a storm of hurricane force that ripped through London, demolishing 600 houses and damaging the Tower of London and several churches. Florence of Worcester described how the roof was lifted off the church of St Mary-le-Bow and six rafters were flung into the air before being driven into the ground by the force of the wind to “seven-eighths of their 27 feet lengths”, landing in the order in which they had been positioned in the roof.

Meanwhile, John of Brompton recorded that the storm swept away the timbers of London Bridge and the Thames overflowed its banks on both sides, the waters flooding the land to a considerable distance.

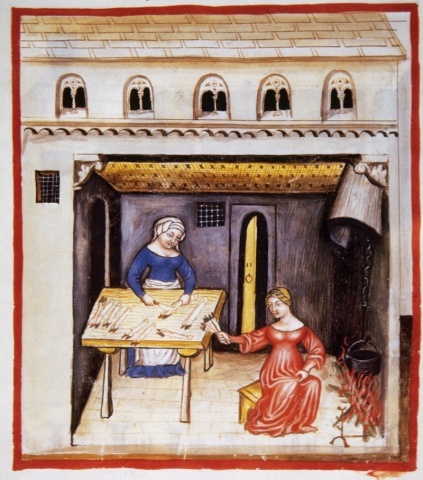

Tacuinum Sanitatis, a 14th-century handbook of health showing a couple in field during a day of north wind. (Photo by Prisma/UIG via Getty Images)

4) ChildrenYoungsters were another cause of concern, especially if they were mischievous and got into scrapes. The consequences could be tragic, as in the case of Richard le Mazon; an eight-year-old schoolboy who lived on London Bridge.

Richard and his friends often dared one other to dangle from a beam that stuck out from the bridge over the rushing river underneath. One day, on his way back to school after dinner in July 1301, Richard tried this feat, but had forgotten to take off his heavy satchel. He lost his grip on the beam and fell into the Thames. His satchel dragged him underwater and he drowned.

5) Money and statusConcern about their status in town could be another thing keeping medieval Londoners awake at night. From about 1330, with the patronage of Queen Philippa (wife of Edward III), England developed its own textile industry as the queen encouraged weavers from Flanders to come to London and set up shop. Good quality, home-produced cloth was now affordable, and even ordinary Londoners were buying and wearing fine clothes.

Citizens were often tempted to emulate courtiers, with their colourful satins, pearls and fine furs. The new clothes being worn by Londoners made it difficult to tell an ordinary citizen from a lord: if a knight passed by, he expected the ‘common folk’ to make way for him and men to doff their caps, but now he looked no grander or better dressed than any number of merchants; their relative positions in the social hierarchy were blurred. Clearly, this situation had to be put right.

In 1337 there came regulations that would later become known as Sumptuary Laws. Extended in 1363, the laws originally applied only in London, and regulated who could wear what kind of cloth, jewellery and particular styles of clothing, to prevent ordinary people dressing like lords and ladies. Those who owned land were always seen to be of a higher status than those with comparable wealth tied up in trade. Therefore a merchant who owned goods worth £500 was considered the social equal of an esquire or gentleman worth only £100. These persons and their families could wear cloth to the value of £3 per bolt or roll of fabric, but no jewels or precious stones, gold, silver, embroidery or silk, and no fur except lamb, rabbit, cat or fox.

Parliament thought these rules were such a great idea that they were re-issued to include means of travel – on foot, by donkey or on horseback and, if so, on what kind of horse – and how often you could eat meat during the week. The laws were continuously updated as fashions changed, on account of the “outrageous and excessive apparel of many people above their estate and degree”. In other words, the humble folk were getting above themselves.

6) RelationshipsIn medieval London there was the worry as to whether or not a couple was legally wed. In those times, a simple exchange of vows between a couple – made in the tavern, the street or even in bed – followed by ‘consummation’ was considered a valid marriage by the church. No witnesses were required, so it could be difficult for either party to prove or disprove afterward that they were married.

While still an apprentice, John Borell, a wax-chandler in London, had an affair with Maud Clerk, a maidservant in the household of a disreputable priest, Father Jeffrey. Once John qualified and set up his own shop, he wanted to marry a respectable young woman, Letitia. Everything was arranged for their wedding in St Paul’s Cathedral, but as the ceremony reached the part where it was asked if there was any impediment or objection to the marriage, Father Jeffrey stood up, claiming John was already married to his serving girl, Maud.

John denied it, but the priest and Maud demanded compensation. The dispute went to court and poor Letitia – the innocent bride – saw all her dowry wasted on lawyers and fines to be paid by her new husband. Their marriage was confirmed as valid, but the newly-weds were left almost penniless.

A couple being married by a clergyman. Central miniature, folio 102v, Book IV by Henricus von Assia (13th century). (Photo by: PHAS/UIG via Getty Images)

7) Punishment for breaking guild rulesThis played on the minds of its members, as anyone failing to keep up standards would suffer the consequences. In 1364, the London vintner, John Penrose, was found guilty of selling bad wine; the penalty being that John had to drink a large measure of his sub-standard wine before the rest was poured over his head.

Such humiliating treatment was a common punishment: bakers of underweight loaves were put in the public stocks, where passers-by could throw mouldy bread rolls at them, while sellers of rotten fruit and vegetables would be pelted with stinking cabbages and tainted apples – or worse! Guild members were expected to behave properly, too. The London goldsmiths fined one of their members severely – not for his own bad behaviour, but because his wife used foul language.

8) What to have for dinner?The age-old daily worry of every housewife: how to give the family a good meal on a tight budget. The most common dinner, for rich and poor alike, was pottage: a thick soup, much like today’s porridge (from which the word comes). Pottage was a popular starter for an elaborate meal or, for the poorer household, the main – and possibly only – course. Here is a recipe for a winter pottage:

Peel onions and boil them in slices, then fry them in a pot. Now halve your chicken and grill it over the fire, or if it be veal the same; and let the veal be put in in gobbets and the chicken in quarters and put them with the onions in the pot; then have white bread toasted on the grill and steeped in the sewe (juices) of the meat; and then bray (crush) ginger, cloves, grains of paradise and long pepper, moisten them with verjuice (crab-apple juice) and wine, but strain them not, and set them aside. Then bray the bread and run it through a strainer and put it in the pot and boil all together; then serve it forth.

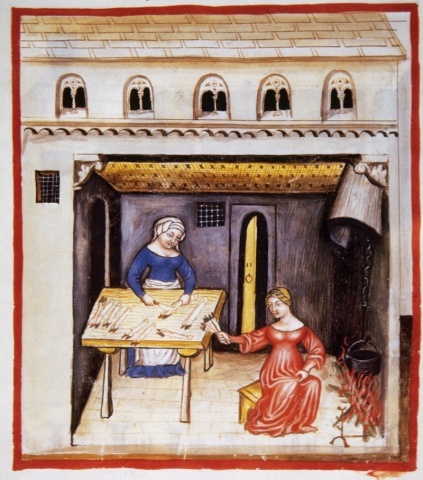

Tacuinum Sanitatis, a 14th-century handbook of health showing women cutting pig's trotters. (Photo by: Prisma/UIG via Getty Images)

9) Going to hellOf far greater consequence for the medieval Londoner was the horrible and, in their minds, very real, worry of going to hell if they died unexpectedly. Without a chance to confess their sins, receive absolution and the last rites, an eternity in hell would be the outcome for them on the Day of Judgement.

For this reason, St Christopher was of great importance as people went about their daily work, because he ensured a holy death by warding off a sudden, accidental fatality. Many churches placed wall paintings, images or statues of St Christopher – usually opposite the south door so he could be easily seen – in the belief that this was sufficient to keep the viewer safe for the rest of the day. St Christopher is usually depicted as a huge man – larger than life-size – with a child on his shoulder and a staff in one hand.

Even if they didn’t attend mass every day, a quick peek through the church door at the image of St Christopher was probably an early morning ritual for many Londoners to ensure they were safe from sudden death and hell – at least until tomorrow.

Toni Mount’s book Everyday Life in Medieval London: From the Anglo-Saxons to the Tudors is now available in paperback from Amberley Publishing. To find out more, click here.

12th-century English illustration of men in prison and in stocks. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

12th-century English illustration of men in prison and in stocks. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images) Here, Toni Mount, the author of Everyday Life in Medieval London: From the Anglo-Saxons to the Tudors reveals nine of the most pressing concerns of people living in the capital in the Middle Ages…

1) HealthPeople have always had concerns about health, be it their own or that of loved ones or neighbours – after all, in the medieval period a sickness might be contagious, and even a splinter could turn septic and prove deadly.

Living in the days before antibiotics, medieval folk had far more than us to worry about. Even a visit to the apothecary – the medieval pharmacist – brought concerns of its own: were the medicines for sale really as described?

The adulteration of medicines was a serious matter in the Middle Ages, and the Lord Mayor of London charged the Grocers’ Company with the task of making certain that no goods went on sale before they were ‘garbled’ (checked for purity and quality). During an inspection in 1475, the apothecary John Davy was pilloried, imprisoned and fined for selling ‘sanders’ (sandalwood), which was nothing more than his own “fabricated powder”.

Other strange and revolting imports included a cask containing ‘putrid wolves’, which William of Lothbury claimed could cure ‘the wolf’ disease. Physicians were asked to look into the matter, but since they could find no such disease in their medical books to require such a remedy, William was fined severely and the goods destroyed.

2) CrimeCrime was as much a worry for medieval Londoners as it is for us today, but whereas we have a police force to deal with such matters, back then there were only the beadles – one for each city ward and a couple of constables to assist him.

Here is an example of this trio in action: in 1474, the beadle of the ward of Farringdon suspected that Joan Salman and Walter Haydon – neither of them wedded – were alone together in a house near the Old Bailey. With two burly constables, the beadle approached the house. The door wasn’t locked, so the beadle and one constable went in, leaving the other at the door to prevent the couple making their escape.

They crept up the stairs to the bedchamber and caught Walter in bed with Joan – “a loose, immoral woman”. The pair were arrested and taken to the Counter (the sheriff’s prison).

In the event of a crime, whoever discovered it first was obliged to “raise the hue and cry” by shouting, banging on doors or clattering pots and pans; rousing the neighbours or anyone within earshot. The idea was that they should all give chase and apprehend the culprit. Only small children, the sick or the lame were excused from taking up the pursuit if they heard the cries of alarm. Otherwise, under a statute of 1275, they were considered to be aiding and abetting the criminal, and could find themselves under arrest. However, if someone raised the hue and cry unnecessarily, they would have to pay a fine.

After curfew, burglary was common in London, despite it being a capital crime. Shops and private houses could be robbed of jewellery, cloth, shoes and blades – anything that might turn a profit. In 1502, a man was arrested in Cornhill for being a “steler of pypes and gutters of lede by means of cutting of theym by nyghtes time”.

3) The weatherThe weather was always a hot topic of conversation in medieval London, and in 1089 there was a lot to talk about: in August, there was an earthquake “over all England”, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Then in November came a storm of hurricane force that ripped through London, demolishing 600 houses and damaging the Tower of London and several churches. Florence of Worcester described how the roof was lifted off the church of St Mary-le-Bow and six rafters were flung into the air before being driven into the ground by the force of the wind to “seven-eighths of their 27 feet lengths”, landing in the order in which they had been positioned in the roof.

Meanwhile, John of Brompton recorded that the storm swept away the timbers of London Bridge and the Thames overflowed its banks on both sides, the waters flooding the land to a considerable distance.

Tacuinum Sanitatis, a 14th-century handbook of health showing a couple in field during a day of north wind. (Photo by Prisma/UIG via Getty Images)

4) ChildrenYoungsters were another cause of concern, especially if they were mischievous and got into scrapes. The consequences could be tragic, as in the case of Richard le Mazon; an eight-year-old schoolboy who lived on London Bridge.

Richard and his friends often dared one other to dangle from a beam that stuck out from the bridge over the rushing river underneath. One day, on his way back to school after dinner in July 1301, Richard tried this feat, but had forgotten to take off his heavy satchel. He lost his grip on the beam and fell into the Thames. His satchel dragged him underwater and he drowned.

5) Money and statusConcern about their status in town could be another thing keeping medieval Londoners awake at night. From about 1330, with the patronage of Queen Philippa (wife of Edward III), England developed its own textile industry as the queen encouraged weavers from Flanders to come to London and set up shop. Good quality, home-produced cloth was now affordable, and even ordinary Londoners were buying and wearing fine clothes.

Citizens were often tempted to emulate courtiers, with their colourful satins, pearls and fine furs. The new clothes being worn by Londoners made it difficult to tell an ordinary citizen from a lord: if a knight passed by, he expected the ‘common folk’ to make way for him and men to doff their caps, but now he looked no grander or better dressed than any number of merchants; their relative positions in the social hierarchy were blurred. Clearly, this situation had to be put right.

In 1337 there came regulations that would later become known as Sumptuary Laws. Extended in 1363, the laws originally applied only in London, and regulated who could wear what kind of cloth, jewellery and particular styles of clothing, to prevent ordinary people dressing like lords and ladies. Those who owned land were always seen to be of a higher status than those with comparable wealth tied up in trade. Therefore a merchant who owned goods worth £500 was considered the social equal of an esquire or gentleman worth only £100. These persons and their families could wear cloth to the value of £3 per bolt or roll of fabric, but no jewels or precious stones, gold, silver, embroidery or silk, and no fur except lamb, rabbit, cat or fox.

Parliament thought these rules were such a great idea that they were re-issued to include means of travel – on foot, by donkey or on horseback and, if so, on what kind of horse – and how often you could eat meat during the week. The laws were continuously updated as fashions changed, on account of the “outrageous and excessive apparel of many people above their estate and degree”. In other words, the humble folk were getting above themselves.

6) RelationshipsIn medieval London there was the worry as to whether or not a couple was legally wed. In those times, a simple exchange of vows between a couple – made in the tavern, the street or even in bed – followed by ‘consummation’ was considered a valid marriage by the church. No witnesses were required, so it could be difficult for either party to prove or disprove afterward that they were married.

While still an apprentice, John Borell, a wax-chandler in London, had an affair with Maud Clerk, a maidservant in the household of a disreputable priest, Father Jeffrey. Once John qualified and set up his own shop, he wanted to marry a respectable young woman, Letitia. Everything was arranged for their wedding in St Paul’s Cathedral, but as the ceremony reached the part where it was asked if there was any impediment or objection to the marriage, Father Jeffrey stood up, claiming John was already married to his serving girl, Maud.

John denied it, but the priest and Maud demanded compensation. The dispute went to court and poor Letitia – the innocent bride – saw all her dowry wasted on lawyers and fines to be paid by her new husband. Their marriage was confirmed as valid, but the newly-weds were left almost penniless.

A couple being married by a clergyman. Central miniature, folio 102v, Book IV by Henricus von Assia (13th century). (Photo by: PHAS/UIG via Getty Images)

7) Punishment for breaking guild rulesThis played on the minds of its members, as anyone failing to keep up standards would suffer the consequences. In 1364, the London vintner, John Penrose, was found guilty of selling bad wine; the penalty being that John had to drink a large measure of his sub-standard wine before the rest was poured over his head.

Such humiliating treatment was a common punishment: bakers of underweight loaves were put in the public stocks, where passers-by could throw mouldy bread rolls at them, while sellers of rotten fruit and vegetables would be pelted with stinking cabbages and tainted apples – or worse! Guild members were expected to behave properly, too. The London goldsmiths fined one of their members severely – not for his own bad behaviour, but because his wife used foul language.

8) What to have for dinner?The age-old daily worry of every housewife: how to give the family a good meal on a tight budget. The most common dinner, for rich and poor alike, was pottage: a thick soup, much like today’s porridge (from which the word comes). Pottage was a popular starter for an elaborate meal or, for the poorer household, the main – and possibly only – course. Here is a recipe for a winter pottage:

Peel onions and boil them in slices, then fry them in a pot. Now halve your chicken and grill it over the fire, or if it be veal the same; and let the veal be put in in gobbets and the chicken in quarters and put them with the onions in the pot; then have white bread toasted on the grill and steeped in the sewe (juices) of the meat; and then bray (crush) ginger, cloves, grains of paradise and long pepper, moisten them with verjuice (crab-apple juice) and wine, but strain them not, and set them aside. Then bray the bread and run it through a strainer and put it in the pot and boil all together; then serve it forth.

Tacuinum Sanitatis, a 14th-century handbook of health showing women cutting pig's trotters. (Photo by: Prisma/UIG via Getty Images)

9) Going to hellOf far greater consequence for the medieval Londoner was the horrible and, in their minds, very real, worry of going to hell if they died unexpectedly. Without a chance to confess their sins, receive absolution and the last rites, an eternity in hell would be the outcome for them on the Day of Judgement.

For this reason, St Christopher was of great importance as people went about their daily work, because he ensured a holy death by warding off a sudden, accidental fatality. Many churches placed wall paintings, images or statues of St Christopher – usually opposite the south door so he could be easily seen – in the belief that this was sufficient to keep the viewer safe for the rest of the day. St Christopher is usually depicted as a huge man – larger than life-size – with a child on his shoulder and a staff in one hand.

Even if they didn’t attend mass every day, a quick peek through the church door at the image of St Christopher was probably an early morning ritual for many Londoners to ensure they were safe from sudden death and hell – at least until tomorrow.

Toni Mount’s book Everyday Life in Medieval London: From the Anglo-Saxons to the Tudors is now available in paperback from Amberley Publishing. To find out more, click here.

Published on December 16, 2015 03:00

History Trivia - Henry VI of England crowned King of France

December 16

1431 Henry VI of England was crowned King of France at Notre Dame in Paris. Though young Henry had been proclaimed king at age ten months, it was not until he was ten years old that he was officially crowned at Notre Dame Cathedral.

1485 Catherine of Aragon, Spanish princess and first wife of Henry VIII was born.

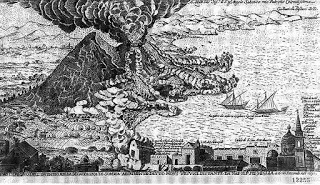

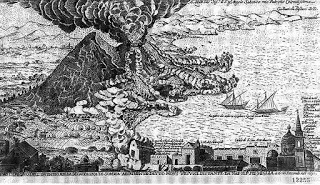

1631 Mount Vesuvius, Italy erupted, destroying 6 villages & killing 4,000.

1431 Henry VI of England was crowned King of France at Notre Dame in Paris. Though young Henry had been proclaimed king at age ten months, it was not until he was ten years old that he was officially crowned at Notre Dame Cathedral.

1485 Catherine of Aragon, Spanish princess and first wife of Henry VIII was born.

1631 Mount Vesuvius, Italy erupted, destroying 6 villages & killing 4,000.

Published on December 16, 2015 02:00

December 15, 2015

Lavish banquet hall where Henry VIII entertained visiting royalty is discovered beneath playground

Ancient Origins

Archaeologists are excavating the ruins of a 480-year-old luxuriously decorated banquet house of King Henry VIII of England that was built next to a jousting field. Workers discovered the site of the long-lost building by accident when they were laying cables for a children’s playground in Surrey.

Archaeologists are excavating the ruins of a 480-year-old luxuriously decorated banquet house of King Henry VIII of England that was built next to a jousting field. Workers discovered the site of the long-lost building by accident when they were laying cables for a children’s playground in Surrey.

Archaeologists are discovering that the building’s decorations were as opulent as the palace, says IBTimes in an article about the find. The décor included lead leaves gilded with gold and green-glazed floor tiles, the article says.

"This is prime real estate in terms of Henry VIII's Hampton Court," Dan Jackson, the palace's curator of historic buildings, said.

The banquet hall was near one of the five royal Tiltyard Towers around a 6-acre site where jousting and pageants were held. The towers were built at what IBTimes calls lavish expense as a venue to entertain visiting royals, nobility and ambassadors. The towers, which date to 1534 - 1536, were among the first to be constructed in England. The towers were two to three stories high. From them guests watched mock battle scenes and jousting.

One of the Tiltyard Towers still stands at Hampton Court Palace. It was used for various purposes over the years, including as a herbarium and a guest house. English archaeologists undertook an examination and conservation program of the tower in 2006.

The remaining Tiltyard Tower at Hampton Court Palace, sitting behind what is now a café (

public domain

)As time passed in days of yore, people stopped enjoying the pageants, mock battles and jousting, and gardens were built over the grounds and most of the towers. The exact location of the banquet house had been lost for 300 years.

The remaining Tiltyard Tower at Hampton Court Palace, sitting behind what is now a café (

public domain

)As time passed in days of yore, people stopped enjoying the pageants, mock battles and jousting, and gardens were built over the grounds and most of the towers. The exact location of the banquet house had been lost for 300 years.

Henry VIII himself took to his horse for jousting. He came close to death at a tournament at Greenwich Palace in January 1536 when he was thrown from his horse, which fell on him. Henry was wearing full armor and was out cold for two hours.

Field armor of Henry VIII of England, Italian, Milan or Brescia, about 1544 (Photo by Matthew G. Bisanz/

Wikimedia Commons

)He recovered, but his jousting days ended. He had serious leg injuries in the form of ulcerations that plagued him for life, and the accident may have caused a brain injury that changed his personality, says a documentary produced by the History Channel.

Field armor of Henry VIII of England, Italian, Milan or Brescia, about 1544 (Photo by Matthew G. Bisanz/

Wikimedia Commons

)He recovered, but his jousting days ended. He had serious leg injuries in the form of ulcerations that plagued him for life, and the accident may have caused a brain injury that changed his personality, says a documentary produced by the History Channel.

The documentary says Henry, born in 1491, had been handsome and charming as a young man but changed and died in 1547 a “paranoid, sickly recluse.” Before he died, his eyesight was fading, he was unable to walk and he weighed nearly 400 pounds. Henry and his later wives were unable to conceive. One of the scholars in the documentary speculates that Henry may have had syphilis.

“Another mystery was, what kick-started those chronic personality changes he suffered in his 40s? Was this down to some rare hormonal disorder? Or was it his jousting injuries which were the cause of all his medical problems?” asks a Henry VIII biographer, Robert Hutchinson, in the video.

Henry VIII did have daughters, and a son and heir, Edward, with Jane Seymour. She died as a result of complications from childbirth. But he wanted to secure the succession by having more children, so he remarried. He went on to behead two of his wives and divorced others. A rhyme serves to help people remember these poor women’s fates:

King Henry VIII,

to six wives he was wedded.

one died, one survived,

two divorced, two beheaded.

A portrait of Henry VIII before he became fat, sick, paranoid and melancholy; during this period he was married to Catherine of Aragon for 24 years. He later divorced her, and she died under guard. (

Wikimedia Commons

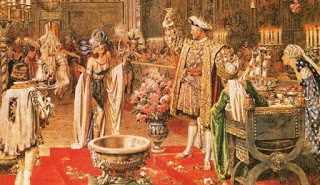

)Featured image: Toasting the revels: The court of Henry VIII, as depicted by the Italian artist Fortunino Matania. Credit: The Bridgeman Art Library.

A portrait of Henry VIII before he became fat, sick, paranoid and melancholy; during this period he was married to Catherine of Aragon for 24 years. He later divorced her, and she died under guard. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Featured image: Toasting the revels: The court of Henry VIII, as depicted by the Italian artist Fortunino Matania. Credit: The Bridgeman Art Library.

By: Mark Miller

Archaeologists are excavating the ruins of a 480-year-old luxuriously decorated banquet house of King Henry VIII of England that was built next to a jousting field. Workers discovered the site of the long-lost building by accident when they were laying cables for a children’s playground in Surrey.

Archaeologists are excavating the ruins of a 480-year-old luxuriously decorated banquet house of King Henry VIII of England that was built next to a jousting field. Workers discovered the site of the long-lost building by accident when they were laying cables for a children’s playground in Surrey.Archaeologists are discovering that the building’s decorations were as opulent as the palace, says IBTimes in an article about the find. The décor included lead leaves gilded with gold and green-glazed floor tiles, the article says.

"This is prime real estate in terms of Henry VIII's Hampton Court," Dan Jackson, the palace's curator of historic buildings, said.

The banquet hall was near one of the five royal Tiltyard Towers around a 6-acre site where jousting and pageants were held. The towers were built at what IBTimes calls lavish expense as a venue to entertain visiting royals, nobility and ambassadors. The towers, which date to 1534 - 1536, were among the first to be constructed in England. The towers were two to three stories high. From them guests watched mock battle scenes and jousting.

One of the Tiltyard Towers still stands at Hampton Court Palace. It was used for various purposes over the years, including as a herbarium and a guest house. English archaeologists undertook an examination and conservation program of the tower in 2006.

The remaining Tiltyard Tower at Hampton Court Palace, sitting behind what is now a café (

public domain

)As time passed in days of yore, people stopped enjoying the pageants, mock battles and jousting, and gardens were built over the grounds and most of the towers. The exact location of the banquet house had been lost for 300 years.

The remaining Tiltyard Tower at Hampton Court Palace, sitting behind what is now a café (

public domain

)As time passed in days of yore, people stopped enjoying the pageants, mock battles and jousting, and gardens were built over the grounds and most of the towers. The exact location of the banquet house had been lost for 300 years.Henry VIII himself took to his horse for jousting. He came close to death at a tournament at Greenwich Palace in January 1536 when he was thrown from his horse, which fell on him. Henry was wearing full armor and was out cold for two hours.

Field armor of Henry VIII of England, Italian, Milan or Brescia, about 1544 (Photo by Matthew G. Bisanz/

Wikimedia Commons

)He recovered, but his jousting days ended. He had serious leg injuries in the form of ulcerations that plagued him for life, and the accident may have caused a brain injury that changed his personality, says a documentary produced by the History Channel.

Field armor of Henry VIII of England, Italian, Milan or Brescia, about 1544 (Photo by Matthew G. Bisanz/

Wikimedia Commons

)He recovered, but his jousting days ended. He had serious leg injuries in the form of ulcerations that plagued him for life, and the accident may have caused a brain injury that changed his personality, says a documentary produced by the History Channel.The documentary says Henry, born in 1491, had been handsome and charming as a young man but changed and died in 1547 a “paranoid, sickly recluse.” Before he died, his eyesight was fading, he was unable to walk and he weighed nearly 400 pounds. Henry and his later wives were unable to conceive. One of the scholars in the documentary speculates that Henry may have had syphilis.

“Another mystery was, what kick-started those chronic personality changes he suffered in his 40s? Was this down to some rare hormonal disorder? Or was it his jousting injuries which were the cause of all his medical problems?” asks a Henry VIII biographer, Robert Hutchinson, in the video.

Henry VIII did have daughters, and a son and heir, Edward, with Jane Seymour. She died as a result of complications from childbirth. But he wanted to secure the succession by having more children, so he remarried. He went on to behead two of his wives and divorced others. A rhyme serves to help people remember these poor women’s fates:

King Henry VIII,

to six wives he was wedded.

one died, one survived,

two divorced, two beheaded.

A portrait of Henry VIII before he became fat, sick, paranoid and melancholy; during this period he was married to Catherine of Aragon for 24 years. He later divorced her, and she died under guard. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Featured image: Toasting the revels: The court of Henry VIII, as depicted by the Italian artist Fortunino Matania. Credit: The Bridgeman Art Library.

A portrait of Henry VIII before he became fat, sick, paranoid and melancholy; during this period he was married to Catherine of Aragon for 24 years. He later divorced her, and she died under guard. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Featured image: Toasting the revels: The court of Henry VIII, as depicted by the Italian artist Fortunino Matania. Credit: The Bridgeman Art Library. By: Mark Miller

Published on December 15, 2015 08:46

History Trivia - Belisarius defeats the Vandals

December 15

37 Nero was born. He was the Roman emperor who is alleged to have fiddled while Rome burned.

533 Byzantine general Belisarius defeated the Vandals, commanded by King Gelimer, at the Battle of Ticameron.

687 Sergius I (Saint Sergius) was elected Roman Catholic pope. He received Caedwalla, King of the West Saxons, and baptized him (689) but because the King died in Rome, he was buried in St. Peter's. Sergius also ordered St. Wilfrid to be restored to his see (Bishopric at York), greatly favored St. Aldhelm, Abbot of Malmesbury, and is credited with endeavoring to secure the Venerable Bede as his adviser. Finally he consecrated the Englishman St. Willibrord bishop, and sent him to preach Christianity to the Frisians.

37 Nero was born. He was the Roman emperor who is alleged to have fiddled while Rome burned.

533 Byzantine general Belisarius defeated the Vandals, commanded by King Gelimer, at the Battle of Ticameron.

687 Sergius I (Saint Sergius) was elected Roman Catholic pope. He received Caedwalla, King of the West Saxons, and baptized him (689) but because the King died in Rome, he was buried in St. Peter's. Sergius also ordered St. Wilfrid to be restored to his see (Bishopric at York), greatly favored St. Aldhelm, Abbot of Malmesbury, and is credited with endeavoring to secure the Venerable Bede as his adviser. Finally he consecrated the Englishman St. Willibrord bishop, and sent him to preach Christianity to the Frisians.

Published on December 15, 2015 02:00

December 14, 2015

History Trivia - Princess Mary Stuart becomes Queen Mary I of Scotland

December 14

867 Adrian II was elected Roman Catholic pope. Adrian had difficulties with international politics. The eighth ecumenical council and the fourth Council of Constantinople took place during his reign. He died on this date in 872.

1503 Nostradamus was born. Author of a collection of predictions in quatrains published in the book Centuries, Nostradamus gained fame in his lifetime when some of his prophecies appeared to come true.

1542 Princess Mary Stuart became Queen Mary I of Scotland.

867 Adrian II was elected Roman Catholic pope. Adrian had difficulties with international politics. The eighth ecumenical council and the fourth Council of Constantinople took place during his reign. He died on this date in 872.

1503 Nostradamus was born. Author of a collection of predictions in quatrains published in the book Centuries, Nostradamus gained fame in his lifetime when some of his prophecies appeared to come true.

1542 Princess Mary Stuart became Queen Mary I of Scotland.

Published on December 14, 2015 02:00

December 13, 2015

Massive Viking Hoard Unearthed by Treasure Hunter Publicly Revealed for First Time

Ancient Origins

An impressive Viking and Saxon hoard of silver and gold riches that was discovered by an amateur treasure hunter in October is being publicly revealed for the first time at the British Museum. The treasure trove is believed to have been buried during ninth-century AD war and upheaval in southern England.

An impressive Viking and Saxon hoard of silver and gold riches that was discovered by an amateur treasure hunter in October is being publicly revealed for the first time at the British Museum. The treasure trove is believed to have been buried during ninth-century AD war and upheaval in southern England.

The Watlington Hoard, as it is known, consists of more than 200 pieces including chopped up gold, silver arm rings, silver ingots and coins minted by King Alfred the Great of Wessex and King Ceolwulf II of Mercia. The coins alone, 180 of them, are worth up to £2,500 (US$$3,788) apiece, for an approximate total of £450,000 (US $947,000).

James Mather, a retired advertising manager, found the hoard while equipped with a metal detector on a farm near Watlington, and will get to share the value of it with the landowner.

Whoever the original owner of the hoard was, he probably buried it in the late 870s, when the Anglo-Saxons began to push the Vikings north of the Thames into East Anglia. Prior to 878, the Vikings had been increasing raids from Denmark. The Anglo Saxons began to re-establish their rule over southern England and won a decisive battle at Edington in 878. Experts have speculated that a Viking fleeing the Anglo Saxons after this battle buried it on his way north, on the ancient road from East Anglia to Wiltshire and Dorset.

A silver coin depicting Alfred the Great (

public domain

)On one side of the coins is shown an emperor’s head, and on the other are Kings Alfred and Ceowulf II seated side by side. They became allies to defeat the Vikings, though their realms had been traditional enemies.

A silver coin depicting Alfred the Great (

public domain

)On one side of the coins is shown an emperor’s head, and on the other are Kings Alfred and Ceowulf II seated side by side. They became allies to defeat the Vikings, though their realms had been traditional enemies.

Later, Alfred annexed Mercia and called Ceowulf a fool and a Viking puppet.

The BBC reports that the British Museum’s curator of early medieval coins, Gareth Williams, said: “This is not just another big shiny hoard. They give a more complex political picture of a period which has been deliberately misrepresented by the victor.”

This time in English history is poorly understood, he said, and the coins give insight into the coalition of Alfred’s West Saxons and Ceowulf’s East Anglians. The alliance broke up acrimoniously, and Ceowulf disappeared from history except in a list of kings that says he ruled for five years and a document recording Alfred’s insults.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

A statue of Alfred the Great at Winchester; he is considered one of the great English kings. (Photo by Odejea/ Wikimedia Commons )For more than 20 years, Mr. Mather’s hobby has been metal detecting. Last October he had spent a long day finding nothing important when he finally came across what he thought was a silver Viking ingot like one he had seen at the British Museum. He dug a hole and saw the big clump of coins. He filled in the hole and then called the local representative of the portable antiquities scheme to record the discovery. He told the BBC he went back to the field several times over the weekend to check on the find and make sure it was unmolested.

The next week David Williams, the finds official, excavated the earth and lifted a block of clay that held the hoard, placed it on an oven tray and took it to London in a suitcase.

A museum conservator, Pippa Pearce, said that some of the coins are so thin they can’t be handled by the edges.

The treasure has been reported, per British law. The British Museum and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford are in negotiations to purchase the hoard, and it is on display along with a 2010 find of more than 52,000 Roman coins found in jars at Frome, Somerset.

So far in 2015 113,784 portable antiquities have been reported, including 1,008 treasure discoveries.

Coins from the Frome hoard of more than 52,000 Roman coins are on display along with the Watlington hoard at the British Museum. (British Museum photo)Featured image: Credit: The British Museum

Coins from the Frome hoard of more than 52,000 Roman coins are on display along with the Watlington hoard at the British Museum. (British Museum photo)Featured image: Credit: The British Museum

By: Mark Miller

An impressive Viking and Saxon hoard of silver and gold riches that was discovered by an amateur treasure hunter in October is being publicly revealed for the first time at the British Museum. The treasure trove is believed to have been buried during ninth-century AD war and upheaval in southern England.

An impressive Viking and Saxon hoard of silver and gold riches that was discovered by an amateur treasure hunter in October is being publicly revealed for the first time at the British Museum. The treasure trove is believed to have been buried during ninth-century AD war and upheaval in southern England.The Watlington Hoard, as it is known, consists of more than 200 pieces including chopped up gold, silver arm rings, silver ingots and coins minted by King Alfred the Great of Wessex and King Ceolwulf II of Mercia. The coins alone, 180 of them, are worth up to £2,500 (US$$3,788) apiece, for an approximate total of £450,000 (US $947,000).

James Mather, a retired advertising manager, found the hoard while equipped with a metal detector on a farm near Watlington, and will get to share the value of it with the landowner.

Whoever the original owner of the hoard was, he probably buried it in the late 870s, when the Anglo-Saxons began to push the Vikings north of the Thames into East Anglia. Prior to 878, the Vikings had been increasing raids from Denmark. The Anglo Saxons began to re-establish their rule over southern England and won a decisive battle at Edington in 878. Experts have speculated that a Viking fleeing the Anglo Saxons after this battle buried it on his way north, on the ancient road from East Anglia to Wiltshire and Dorset.

A silver coin depicting Alfred the Great (

public domain

)On one side of the coins is shown an emperor’s head, and on the other are Kings Alfred and Ceowulf II seated side by side. They became allies to defeat the Vikings, though their realms had been traditional enemies.

A silver coin depicting Alfred the Great (

public domain

)On one side of the coins is shown an emperor’s head, and on the other are Kings Alfred and Ceowulf II seated side by side. They became allies to defeat the Vikings, though their realms had been traditional enemies.Later, Alfred annexed Mercia and called Ceowulf a fool and a Viking puppet.

The BBC reports that the British Museum’s curator of early medieval coins, Gareth Williams, said: “This is not just another big shiny hoard. They give a more complex political picture of a period which has been deliberately misrepresented by the victor.”

This time in English history is poorly understood, he said, and the coins give insight into the coalition of Alfred’s West Saxons and Ceowulf’s East Anglians. The alliance broke up acrimoniously, and Ceowulf disappeared from history except in a list of kings that says he ruled for five years and a document recording Alfred’s insults.

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

A statue of Alfred the Great at Winchester; he is considered one of the great English kings. (Photo by Odejea/ Wikimedia Commons )For more than 20 years, Mr. Mather’s hobby has been metal detecting. Last October he had spent a long day finding nothing important when he finally came across what he thought was a silver Viking ingot like one he had seen at the British Museum. He dug a hole and saw the big clump of coins. He filled in the hole and then called the local representative of the portable antiquities scheme to record the discovery. He told the BBC he went back to the field several times over the weekend to check on the find and make sure it was unmolested.

The next week David Williams, the finds official, excavated the earth and lifted a block of clay that held the hoard, placed it on an oven tray and took it to London in a suitcase.

A museum conservator, Pippa Pearce, said that some of the coins are so thin they can’t be handled by the edges.

The treasure has been reported, per British law. The British Museum and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford are in negotiations to purchase the hoard, and it is on display along with a 2010 find of more than 52,000 Roman coins found in jars at Frome, Somerset.

So far in 2015 113,784 portable antiquities have been reported, including 1,008 treasure discoveries.

Coins from the Frome hoard of more than 52,000 Roman coins are on display along with the Watlington hoard at the British Museum. (British Museum photo)Featured image: Credit: The British Museum

Coins from the Frome hoard of more than 52,000 Roman coins are on display along with the Watlington hoard at the British Museum. (British Museum photo)Featured image: Credit: The British Museum By: Mark Miller

Published on December 13, 2015 03:00