MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 131

December 8, 2015

Fit for a queen: 3 medieval recipes enjoyed at English and Scottish royal courts

History Extra

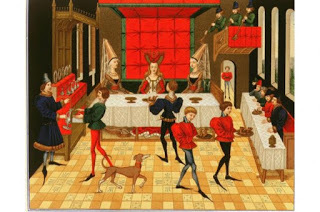

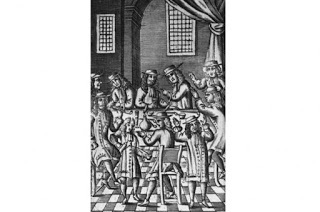

15th-century banquet. © The Art Archive / Alamy

15th-century banquet. © The Art Archive / Alamy

Exploring the significance of food in the royal court of Mary of Guise – mother of Mary, Queen of Scots – The Queen’s Feast will see dishes such as game pie and a sweet rice pudding known as Rys Lumbard served to visitors on Saturday 23 and Sunday 24 May.

Prepared and inspired from real recipes of the time, the dishes offer an insight into medieval court life.

Here, Historic Scotland shares three of the popular recipes…

Rys Lumbard StondynePeriod: England, 14th century

Description: Sweet Rice and Egg Pudding

Original recipe

And for to make rys lumbard stondyne, take raw yolkes of

eyren, and bete hom, and put hom to the rys beforesaid, and

qwen hit is sothen take hit off the fyre, and make thenne a

dragée of the yolkes of harde eyren broken, and sugre and

gynger mynced, and clowes, and maces; and qwen hit is put

in dyshes, strawe the dragée theron, and serve hit forth.

Modern recipe

• 1 cup rice

• 2 cups beef, chicken,

or other broth

• 4 raw egg yolks

• 2 tsp sugar, or to taste

• 1/8 tsp saffron

• Salt to taste

Dragées

• 2 hard-boiled egg yolks

• 1 tsp sugar, or to taste

• 1 tsp grated fresh ginger

• 1/8 tsp each cloves and mace

1) In a heavy saucepan or pot combine rice, broth and salt. Over medium heat, bring to a boil, reduce heat and simmer, covered, for about 15 minutes, or until all liquid has been absorbed.

2) When rice is done, stir in raw egg yolks, sugar and saffron, and cook over medium heat, stirring constantly, until the mixture gets very thick. Dish into a lightly oiled mould or bowl, cool, and turn out for serving.

3) To make the dragées, in a bowl combine hard-boiled egg yolks, grated fresh ginger, sugar and spices, and blend into a paste. Roll this paste into little balls about half an inch across, and decorate the moulded Rys Lumbard with them.

Great PieIngredients

• 1 kg mixed game (venison, pheasant, rabbit and boar)

• 2 large onions, peeled and diced

• 1 garlic clove

• 120 grams of brown mushrooms, sliced

• 120 grams smoked back bacon, diced

• 25 grams plain flour

• Juice and zest of 1 orange

• 300 ml chicken stock

• 70 ml of Merlot wine

• Salt and pepper

Modern recipe (serves eight to 12)

1) Preheat oven to 180°C.

2) In a frying pan, brown the game.

3) Soften the onions and then add the garlic, mushrooms and bacon and fry for a few minutes. Add the stock and orange juice and zest. Raise it to a boil then simmer for an hour until the meat is tender.

4) Let the mixture cool and add it to your short crust pastry case. Add a pastry lid and press it onto the lip of the base then trim it. Cut a steam hole or two and brush with a beaten egg all over.

5) Put the pie in the oven and bake for one hour. Cool before serving.

An early 14th-century royal meal; illustration from Dresses and Decorations of the Middle Ages from the Seventh to the Seventeenth Centuries by Henry Shaw, (London, 1843). (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Malaches of PorkPeriod: England, 14th century

Description: Pork Quiche

Original recipe

Hewe pork al to pecys and medle it with ayren & chese

igrated. Do therto powdour fort, safroun & pynes with salt.

Make a crust in a trap; bake it wel therinne, and serue it forth.

Modern recipe (Serves eight to 12)

• Pastry dough for 1 nine-inch pie crust

• 1 pound lean pork, cubed

• 4 eggs

• 1 cup grated, hard cheese

• 1/4 cup pine nuts

• 1/4 tsp salt

• Pinch of each, cloves, mace, black pepper

1) Preheat oven to 230°C.

2) Line a nine-inch pie pan with the pastry dough, and bake it for five to 10 minutes to harden it. Remove it, and reduce oven temperature to 175°C.

3) In a frying pan, over medium heat, brown the cubed pork until it is tender.

4) In a bowl, beat the eggs and spices together.

5) Line the bottom of the pie crust with the browned pork, grated cheese, and pine nuts. Pour the egg and spice mixture over them.

6) Put the pie in the oven and bake for 45 minutes, or until a toothpick draws out clean. Cool before serving.

15th-century banquet. © The Art Archive / Alamy

15th-century banquet. © The Art Archive / Alamy Exploring the significance of food in the royal court of Mary of Guise – mother of Mary, Queen of Scots – The Queen’s Feast will see dishes such as game pie and a sweet rice pudding known as Rys Lumbard served to visitors on Saturday 23 and Sunday 24 May.

Prepared and inspired from real recipes of the time, the dishes offer an insight into medieval court life.

Here, Historic Scotland shares three of the popular recipes…

Rys Lumbard StondynePeriod: England, 14th century

Description: Sweet Rice and Egg Pudding

Original recipe

And for to make rys lumbard stondyne, take raw yolkes of

eyren, and bete hom, and put hom to the rys beforesaid, and

qwen hit is sothen take hit off the fyre, and make thenne a

dragée of the yolkes of harde eyren broken, and sugre and

gynger mynced, and clowes, and maces; and qwen hit is put

in dyshes, strawe the dragée theron, and serve hit forth.

Modern recipe

• 1 cup rice

• 2 cups beef, chicken,

or other broth

• 4 raw egg yolks

• 2 tsp sugar, or to taste

• 1/8 tsp saffron

• Salt to taste

Dragées

• 2 hard-boiled egg yolks

• 1 tsp sugar, or to taste

• 1 tsp grated fresh ginger

• 1/8 tsp each cloves and mace

1) In a heavy saucepan or pot combine rice, broth and salt. Over medium heat, bring to a boil, reduce heat and simmer, covered, for about 15 minutes, or until all liquid has been absorbed.

2) When rice is done, stir in raw egg yolks, sugar and saffron, and cook over medium heat, stirring constantly, until the mixture gets very thick. Dish into a lightly oiled mould or bowl, cool, and turn out for serving.

3) To make the dragées, in a bowl combine hard-boiled egg yolks, grated fresh ginger, sugar and spices, and blend into a paste. Roll this paste into little balls about half an inch across, and decorate the moulded Rys Lumbard with them.

Great PieIngredients

• 1 kg mixed game (venison, pheasant, rabbit and boar)

• 2 large onions, peeled and diced

• 1 garlic clove

• 120 grams of brown mushrooms, sliced

• 120 grams smoked back bacon, diced

• 25 grams plain flour

• Juice and zest of 1 orange

• 300 ml chicken stock

• 70 ml of Merlot wine

• Salt and pepper

Modern recipe (serves eight to 12)

1) Preheat oven to 180°C.

2) In a frying pan, brown the game.

3) Soften the onions and then add the garlic, mushrooms and bacon and fry for a few minutes. Add the stock and orange juice and zest. Raise it to a boil then simmer for an hour until the meat is tender.

4) Let the mixture cool and add it to your short crust pastry case. Add a pastry lid and press it onto the lip of the base then trim it. Cut a steam hole or two and brush with a beaten egg all over.

5) Put the pie in the oven and bake for one hour. Cool before serving.

An early 14th-century royal meal; illustration from Dresses and Decorations of the Middle Ages from the Seventh to the Seventeenth Centuries by Henry Shaw, (London, 1843). (Photo by The Print Collector/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Malaches of PorkPeriod: England, 14th century

Description: Pork Quiche

Original recipe

Hewe pork al to pecys and medle it with ayren & chese

igrated. Do therto powdour fort, safroun & pynes with salt.

Make a crust in a trap; bake it wel therinne, and serue it forth.

Modern recipe (Serves eight to 12)

• Pastry dough for 1 nine-inch pie crust

• 1 pound lean pork, cubed

• 4 eggs

• 1 cup grated, hard cheese

• 1/4 cup pine nuts

• 1/4 tsp salt

• Pinch of each, cloves, mace, black pepper

1) Preheat oven to 230°C.

2) Line a nine-inch pie pan with the pastry dough, and bake it for five to 10 minutes to harden it. Remove it, and reduce oven temperature to 175°C.

3) In a frying pan, over medium heat, brown the cubed pork until it is tender.

4) In a bowl, beat the eggs and spices together.

5) Line the bottom of the pie crust with the browned pork, grated cheese, and pine nuts. Pour the egg and spice mixture over them.

6) Put the pie in the oven and bake for 45 minutes, or until a toothpick draws out clean. Cool before serving.

Published on December 08, 2015 03:00

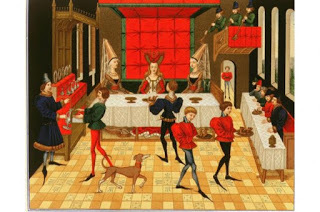

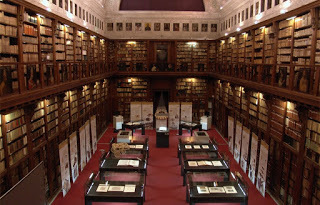

History Trivia - Biblioteca Ambrosiana (Milan Italy) opens reading room

December 8

1542 Mary, Queen of Scots was born.

1609 Biblioteca Ambrosiana (Milan Italy) opened its reading room, the second public library of Europe.

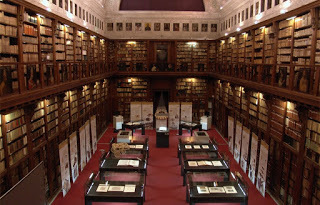

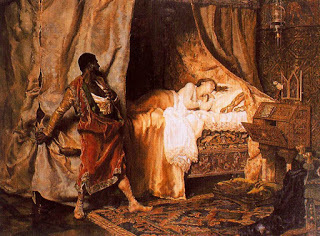

1660 The first Shakespearean actress to appear on an English stage (believed to be a Ms. Norris) made her debut as Desdemona in Shakespeare's Othello.

1542 Mary, Queen of Scots was born.

1609 Biblioteca Ambrosiana (Milan Italy) opened its reading room, the second public library of Europe.

1660 The first Shakespearean actress to appear on an English stage (believed to be a Ms. Norris) made her debut as Desdemona in Shakespeare's Othello.

Published on December 08, 2015 02:00

December 7, 2015

New Release - Reflections by K. Meador

Reflections is a sixteen-story devotional designed to draw yourself closer to God. Experience Him through each unique story, which will let you know He is alive and involved in your life. Reflections will help you cut through life’s distractions and rely on the one thing that is truly important – a relationship with God.

Reflections serves as a refreshing reminder of God’s love and grace during difficult times. The world wants you to place your trust in your circumstances, success, talents and opinions of others, but God has called you to rise above and put your full trust in Him – to believe and apply what He’s promised in His Word more than anything else.

Experience the life-changing power of God’s words as you journey through life assured that God is concerned about you.

Amazon reviews:

Using only the tool of well-crafted words, K. Meador has a gift for bringing her readers and listeners into real relationships with her characters and their life challenges. I liked how she shares, and even teaches, spiritual truths without a trace of a religious spirit. You can tell she's "been there" by the details she includes in her simple and clearly written depictions. K-Trina doesn't sugar-coat the grit and internal drama her characters face. You get the sense that the guidance and encouragement she is offering through some real-life struggles that have devastated many, can actually be realized in every life that will be as honest with themselves as this writer is with her pen. From the depth of character I sensed in her writing, I wanted to see if this was maintained through her other works. I was amazed to find such diversified genres to which she has contributed, and was hooked as I read the Amazon preview of her vivid and redeeming stories of powerful love and hope, set against a Civil War era backdrop. Yet her children's stories are so delightfully innocent and full of fantasy! I am impressed with this author and highly recommend any of her works.

K. Meador's Reflections: For the Heart and Soul was a excellent read.

The way the author used specific situations and stories to correspond to biblical studies made the scriptures come to life.

After each example you found yourself reflecting on your personal walk with God and how your actions are influenced by inner thoughts.

It's a beautiful, well written, and personal read.

Amazon Link

Published on December 07, 2015 11:10

Pearl Harbor Day - December 7

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941. The attack led to the United States' entry into World War II.

Published on December 07, 2015 03:30

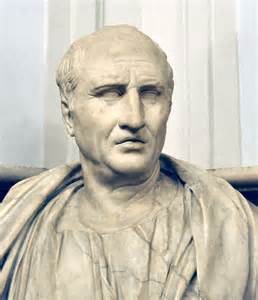

History Trivia - Cicero executed

December 7

43 BC Roman orator and advocate Cicero was executed on the orders of Mark Antony.

983 German King Otto III took the throne after his father's death in Italy. He was the fourth ruler of the Saxon (Ottonian) dynasty of the Holy Roman Empire, being crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 997.

1254 Pope Innocent IV died. The pontificate of Innocent was marked by a long struggle with Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, characteristic of the conflict between empire and papacy.

43 BC Roman orator and advocate Cicero was executed on the orders of Mark Antony.

983 German King Otto III took the throne after his father's death in Italy. He was the fourth ruler of the Saxon (Ottonian) dynasty of the Holy Roman Empire, being crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 997.

1254 Pope Innocent IV died. The pontificate of Innocent was marked by a long struggle with Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, characteristic of the conflict between empire and papacy.

Published on December 07, 2015 02:30

December 6, 2015

The quest for the Holy Grail

History Extra

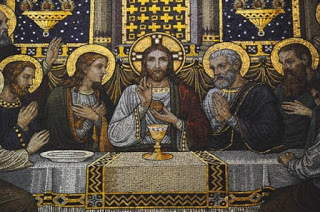

The Last Supper and first Eucharist, during which Jesus serves wine in the Holy Chalice. © Corbis

The Last Supper and first Eucharist, during which Jesus serves wine in the Holy Chalice. © Corbis

In the most popular version of the story, the Holy Grail is a chalice used by Jesus during the Last Supper, which was later employed as a vial for his blood. It was seemingly smuggled across the Holy Land and Europe to Britain. Despite a series of mysterious Grail guardians, including the Fisher King and the Knights Templar, at some point the chalice disappeared.

The sacred silverware became spliced with other legends, invested with mythical powers, and hijacked by conspiracy theorists and demagogues. Pat Kinsella separates the few facts from the profuse fictions that continue to evolve around this elusive relic…

Birth of a legend: Where did the Holy Grail come from? And what might it be?Holy relics purporting to originate from the earthly life of Jesus are common currency across the Catholic world – with various churches claiming to hold everything from the Holy Prepuce (Jesus’s foreskin) through to nails used during his crucifixion. The most iconic and sought-after souvenir of all, however, is the ever-elusive Holy Grail.

The enduring obsession with the Holy Grail is fuelled by the fact that its form, location and very existence remain a complete enigma. It’s popularly believed to be a goblet used during the Last Supper and then employed by Joseph of Arimathea to catch Christ’s blood when his side was pierced with a spear during his crucifixion. However, some depictions have it as a bowl or a serving plate, or even as the womb of Mary Magdalene – in a scenario where she bears Jesus’s offspring.

The Holy Chalice from the Last Supper is referenced in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke (which historians believe were written c80-100 AD), but it was 1,000 years later that the tale of the Grail became popular, when the medieval romantics began to pen poems about it, entwining the yarn with Arthurian sagas.

The first-known reference to the Grail was made by French poet Chrétien de Troyes in Perceval, le Conte du Graal (which translates as ‘Percival, the Story of the Grail’), an unfinished poem written sometime between 1181 and 1190. Chrétien credits a source book, but the original work remains a mystery.

His fantastical yarn sees Percival – one of King Arthur’s knights – visit the realm of the Fisher King (the last in a line of men entrusted with the keeping of the Grail). There, he beholds several revered items, including a graal (‘grail’) – an elaborate bowl from which the King eats a communion wafer. Although the Grail is more prop than main player in this poem, it inspired other writers to develop the concept.

In Joseph d’Arimathie, written between 1191 and 1202, fellow Frenchman Robert de Boron fused the Holy Chalice used at the Last Supper, and the Holy Grail, a vessel containing Jesus’s blood. Joseph of Arimathea is cast as the protector of the Grail, the first of a long line of guardians that will include Percival.

In the early 13th century, German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach developed the story in Parzival, (‘Percival’), an epic poem in which the hero embarks on a quest to recover the Grail. The Welsh romance Peredur continued the theme, but the story really took form in the Vulgate Cycle, a series of Arthurian legends written anonymously in the 13th century.

Two centuries later, Sir Thomas Malory translated these legends into English in Le Morte D’Arthur and the sagas – especially the quest for the Grail – have enjoyed waves of popularity ever since, being retold by a colourful collection of raconteurs from Wagner and Tennyson through to Monty Python, Spielberg and Dan Brown. But is there any fact amongst all the fantasy?

The Grail trail: For centuries, explorers have chased the Grail’s shadow all over the planetAlthough most popular versions of the story ultimately point towards the chalice being transported to England, committed Grail hunters have chased the holy relic all over the world. Every perceived clue from ancient texts has been painstakingly pursued, while long-shot leads and far-fetched theories have led their followers to some fairly unlikely corners.

Over 200 churches and locations around the globe have laid claim to having current or historic possession of either or both the Holy Chalice and the Holy Grail – with some stretching the realm of credibility much further than others. Having a semi-plausible relic or a good miracle story can generate a boom in tourism for otherwise out-of-the-way destinations. As the public’s obsession with the Grail tale shows little sign of abating, it’s become big business, right around the world…

Basilica of San Isidoro in León, Spain

Home to the Chalice of Doña Urraca, a jewel-encrusted onyx goblet identified as the Holy Grail by author-researchers Margarita Torres and José Ortega del Rio in their 2014 book, The Kings of the Grail. The chalice has been in the Basilica since the 11th century, after apparently being transported to Cairo by Muslim travellers. It was later given to an emir on the Spanish coast who’d helped famine victims in Egypt, and passed to King Ferdinand I of Leon as a peace offering by an Andalusian ruler. Carbon dating suggests the chalice was made between 200 BC and AD 100.

Cattedrale di San Lorenzo, Italy

House of the Genoa Chalice, once thought to be made from pure emerald and a hot contender for the Holy Grail, until it was transported to Paris after Napoleon conquered Italy and came back broken – revealing the ‘emerald’ was, in fact, green glass. This news would have come as a disappointment to the Genoese soldiers, who named it as their chief target when they defeated the Moors and sacked Almería in a ferocious conflict in 1147.

The Cathedral of Genoa, where a glassy Grail contender resides. © Alamy

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, US

Current home of the Antioch Chalice, a silver-and-gold double-cup design ornament, touted as the Holy Chalice when it was recovered in Antioch, Turkey, just before World War I. The museum has always described this claim as ‘ambitious’ and the relic was recently outed as a standing lamp, not a chalice, believed to have been made in the sixth century AD.

Catedrale de Valencia, Spain

The Valencia Chalice is housed in its very own consecrated chapel. The agate cup was reportedly taken by Saint Peter to Rome in the first century AD, and then to Huesca in Spain by Saint Lawrence in the third century. Some Spanish archaeologists say the cup was produced in a Palestinian or Egyptian workshop between the fourth century BC and the first century AD.

The Jerusalem Chalice, Israel

In the seventh century AD, a Gaulish monk named Arculf recorded seeing a vessel he believed to be the Holy Chalice contained within a reliquary in a chapel near Jerusalem, between the basilica of Golgotha and the Martyrium. This is the earliest known first-hand report of the Grail after the crucifixion, and the only known mention of the Grail being seen in the Holy Land. The fate of the chalice he described is unknown. It has also been claimed that the Grail is hidden with other holy relics in the vast underground sewer complex of Jerusalem, beneath the legendary Solomon’s Temple.

Beneath Temple Mount in Jerusalem some believe there could be a whole host of holy relics. © iStock

Over to Albion: The Grail myths are as much entwined with British folklore as international history…After the crucifixion of Jesus, for reasons that remain unclear (and which may well owe more to poetic license and political and economic expediency than historical fact), the story of the Holy Grail is quickly transplanted from the Holy Land to the green and pleasant land of England.

According to legends that have been doing the rounds for at least the last 800 years, the keeper of the Grail, Joseph of Arimathea, arrived in England in the first century AD. He crossed the Somerset Levels (then flooded) by boat to arrive at the foot of Glastonbury Tor on an island known in Arthurian mythology as Avalon.

At the foot of Wearyall Hill, just beneath the Tor, the tired missionary thrust his staff into the ground, and rested. In the morning, so the story goes, his staff had taken root and grown into an oriental thorn bush now known as the Glastonbury Thorn.

Joseph then went on to found Glastonbury Abbey, and set about converting the locals to Christianity – with a staggering success rate. By 600 AD, England had a Christian king: Ethelbert. Meanwhile the Grail – which, according to some stories, was buried at the entrance to the underworld in Glastonbury – became firmly interwoven into myths about King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table.

Contemporary records mention none of this, though, and the story only became popular after the publication of Robert de Boron’s fanciful poem Joseph d’Arimathie at the end of the 12th century. The area may have been a significant site for pre-Christian communities, but Glastonbury Abbey was almost certainly established by Britons in the early seventh century.

However, stories connecting the dots between the site, Arthurian legend, the presence of the Holy Grail and miracles performed by ‘blood relatives’ of Jesus were all excellent marketing for the pilgrimage trade at Glastonbury. The local monks wholeheartedly endorsed the fables, right up until the Abbey was dissolved in 1539, during the English Reformation.

An early example of this can be seen when, in 1184, a fire destroyed most of the monastic buildings at Glastonbury. A few years later, around the time Joseph d’Arimathie was published, King Arthur and Queen Guinevere’s tomb was miraculously discovered in the cemetery. There was a spike in pilgrimage traffic and the funds needed to rebuild the Abbey.

According to myth, King Arthur’s wizard Merlin still roams Glastonbury Tor. © Alamy

A good story: From medieval poems to modern action movies, the Grail has provided centuries of entertainmentFor two millennia, the legend of the Holy Grail has been reported and contorted by imaginative poets, painters, writers, comedians and filmmakers – to such an extent that the small number of known facts have become increasingly hard to sift from an overwhelming mountain of speculative or purely artistic ideas.

Amateur historians and professional authors have gone off on wild tangents, generating countless pseudo-historical books masquerading as seriously researched non-fiction. Indeed, a vast amount of flimsy and fantastical evidence has been reported as fact to support questionable theories. As a result, the Grail story has assumed a life of its own – one that constantly plays out on the pages of books and websites, and on TV and cinema screens – and each generation consumes a new version of it.

Back in the limelight: Victorian revivalism

During the deeply religious fervour of the Victorian era, medievalism was the all the rage and yarns from the Middle Ages, such as Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur, were constantly being reprinted and consumed by a public hungry for tales of chivalry and salvation.

The quest for the Holy Grail was a recurring theme across the arts throughout the age, but everything was based on the medieval myth, rather than known facts and historical events.

Painters began to depict scenes from Arthurian legends, especially members of the ever-earnest Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. When commissioned to decorate Oxford University’s new union building, founder of the Brotherhood Dante Gabriel Rossetti used the Holy Grail as his central theme – thus seeding an awareness and interest in the subject in the fertile minds of future generations of scholars. It was a theme that Rossetti would return to numerous times in his watercolour paintings.

Over several decades, the pre-eminent poet of the era, Alfred Lord Tennyson (Poet Laureate for 40 years during Victoria’s reign), published the epic Idylls of the King, a cycle of twelve narrative poems that retell the legend of King Arthur and his knights – including, of course, the quest for the Grail. These immensely popular poems were dedicated to the late Prince Albert.

William Morris, one of the most significant cultural figures of the era whose talents spanned everything from poetry to interior design, was also acutely interested in the sagas. He wrote verses about the Holy Chalice, and collaborated with Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones to produce vast tapestries depicting the quest for the Grail, which were hung on the walls of the wealthiest businessmen of the industrial age.

This vast Victorian tapestry, named ‘The Achievement of the Grail’ measures 2.4 metres high by nearly 7 metres long. It is currently on display in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. © BAL

20th-century style: The quest on screen

The Grail has been quested after on big and little screens since technology made it possible, but most people will recall the story from at least one of three successful cinematic renditions…

Excalibur (1981), was directed by John Boorman and starred Nigel Terry, Helen Mirren, Patrick Stewart and Liam Neeson, among many others. An action-packed adventure fantasy, it follows the story of King Arthur, from the moment he pulls the sword from the stone, to the quest for the Grail (via Guinevere and Lancelot’s affair). The film, in contrast to most of the medieval literature, has Percival retrieve the Grail for an ailing Arthur, who sips from it and is restored to health.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), was the Python posse’s first foray into full-length feature films and it is a gloriously ridiculous romp through the Arthurian sagas, with Graham Chapman in the lead role. As the hapless knights search for the Holy Grail they face various challenges and dangers, not least a killer rabbit.

A shot from Monty Python and the Holy Grail. © Kobal

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), the third of Steven Spielberg’s successful series of movies starring Harrison Ford as a swashbuckling archaeologist, sees Indy in action trying to rescue his father (Sean Connery). He then needs to find the Holy Grail before the Nazis get hold of it and use it to achieve world domination. Sound stupid? You might be surprised how close some of the plot elements are to the truth...

The Last Supper and first Eucharist, during which Jesus serves wine in the Holy Chalice. © Corbis

The Last Supper and first Eucharist, during which Jesus serves wine in the Holy Chalice. © Corbis In the most popular version of the story, the Holy Grail is a chalice used by Jesus during the Last Supper, which was later employed as a vial for his blood. It was seemingly smuggled across the Holy Land and Europe to Britain. Despite a series of mysterious Grail guardians, including the Fisher King and the Knights Templar, at some point the chalice disappeared.

The sacred silverware became spliced with other legends, invested with mythical powers, and hijacked by conspiracy theorists and demagogues. Pat Kinsella separates the few facts from the profuse fictions that continue to evolve around this elusive relic…

Birth of a legend: Where did the Holy Grail come from? And what might it be?Holy relics purporting to originate from the earthly life of Jesus are common currency across the Catholic world – with various churches claiming to hold everything from the Holy Prepuce (Jesus’s foreskin) through to nails used during his crucifixion. The most iconic and sought-after souvenir of all, however, is the ever-elusive Holy Grail.

The enduring obsession with the Holy Grail is fuelled by the fact that its form, location and very existence remain a complete enigma. It’s popularly believed to be a goblet used during the Last Supper and then employed by Joseph of Arimathea to catch Christ’s blood when his side was pierced with a spear during his crucifixion. However, some depictions have it as a bowl or a serving plate, or even as the womb of Mary Magdalene – in a scenario where she bears Jesus’s offspring.

The Holy Chalice from the Last Supper is referenced in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke (which historians believe were written c80-100 AD), but it was 1,000 years later that the tale of the Grail became popular, when the medieval romantics began to pen poems about it, entwining the yarn with Arthurian sagas.

The first-known reference to the Grail was made by French poet Chrétien de Troyes in Perceval, le Conte du Graal (which translates as ‘Percival, the Story of the Grail’), an unfinished poem written sometime between 1181 and 1190. Chrétien credits a source book, but the original work remains a mystery.

His fantastical yarn sees Percival – one of King Arthur’s knights – visit the realm of the Fisher King (the last in a line of men entrusted with the keeping of the Grail). There, he beholds several revered items, including a graal (‘grail’) – an elaborate bowl from which the King eats a communion wafer. Although the Grail is more prop than main player in this poem, it inspired other writers to develop the concept.

In Joseph d’Arimathie, written between 1191 and 1202, fellow Frenchman Robert de Boron fused the Holy Chalice used at the Last Supper, and the Holy Grail, a vessel containing Jesus’s blood. Joseph of Arimathea is cast as the protector of the Grail, the first of a long line of guardians that will include Percival.

In the early 13th century, German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach developed the story in Parzival, (‘Percival’), an epic poem in which the hero embarks on a quest to recover the Grail. The Welsh romance Peredur continued the theme, but the story really took form in the Vulgate Cycle, a series of Arthurian legends written anonymously in the 13th century.

Two centuries later, Sir Thomas Malory translated these legends into English in Le Morte D’Arthur and the sagas – especially the quest for the Grail – have enjoyed waves of popularity ever since, being retold by a colourful collection of raconteurs from Wagner and Tennyson through to Monty Python, Spielberg and Dan Brown. But is there any fact amongst all the fantasy?

The Grail trail: For centuries, explorers have chased the Grail’s shadow all over the planetAlthough most popular versions of the story ultimately point towards the chalice being transported to England, committed Grail hunters have chased the holy relic all over the world. Every perceived clue from ancient texts has been painstakingly pursued, while long-shot leads and far-fetched theories have led their followers to some fairly unlikely corners.

Over 200 churches and locations around the globe have laid claim to having current or historic possession of either or both the Holy Chalice and the Holy Grail – with some stretching the realm of credibility much further than others. Having a semi-plausible relic or a good miracle story can generate a boom in tourism for otherwise out-of-the-way destinations. As the public’s obsession with the Grail tale shows little sign of abating, it’s become big business, right around the world…

Basilica of San Isidoro in León, Spain

Home to the Chalice of Doña Urraca, a jewel-encrusted onyx goblet identified as the Holy Grail by author-researchers Margarita Torres and José Ortega del Rio in their 2014 book, The Kings of the Grail. The chalice has been in the Basilica since the 11th century, after apparently being transported to Cairo by Muslim travellers. It was later given to an emir on the Spanish coast who’d helped famine victims in Egypt, and passed to King Ferdinand I of Leon as a peace offering by an Andalusian ruler. Carbon dating suggests the chalice was made between 200 BC and AD 100.

Cattedrale di San Lorenzo, Italy

House of the Genoa Chalice, once thought to be made from pure emerald and a hot contender for the Holy Grail, until it was transported to Paris after Napoleon conquered Italy and came back broken – revealing the ‘emerald’ was, in fact, green glass. This news would have come as a disappointment to the Genoese soldiers, who named it as their chief target when they defeated the Moors and sacked Almería in a ferocious conflict in 1147.

The Cathedral of Genoa, where a glassy Grail contender resides. © Alamy

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, US

Current home of the Antioch Chalice, a silver-and-gold double-cup design ornament, touted as the Holy Chalice when it was recovered in Antioch, Turkey, just before World War I. The museum has always described this claim as ‘ambitious’ and the relic was recently outed as a standing lamp, not a chalice, believed to have been made in the sixth century AD.

Catedrale de Valencia, Spain

The Valencia Chalice is housed in its very own consecrated chapel. The agate cup was reportedly taken by Saint Peter to Rome in the first century AD, and then to Huesca in Spain by Saint Lawrence in the third century. Some Spanish archaeologists say the cup was produced in a Palestinian or Egyptian workshop between the fourth century BC and the first century AD.

The Jerusalem Chalice, Israel

In the seventh century AD, a Gaulish monk named Arculf recorded seeing a vessel he believed to be the Holy Chalice contained within a reliquary in a chapel near Jerusalem, between the basilica of Golgotha and the Martyrium. This is the earliest known first-hand report of the Grail after the crucifixion, and the only known mention of the Grail being seen in the Holy Land. The fate of the chalice he described is unknown. It has also been claimed that the Grail is hidden with other holy relics in the vast underground sewer complex of Jerusalem, beneath the legendary Solomon’s Temple.

Beneath Temple Mount in Jerusalem some believe there could be a whole host of holy relics. © iStock

Over to Albion: The Grail myths are as much entwined with British folklore as international history…After the crucifixion of Jesus, for reasons that remain unclear (and which may well owe more to poetic license and political and economic expediency than historical fact), the story of the Holy Grail is quickly transplanted from the Holy Land to the green and pleasant land of England.

According to legends that have been doing the rounds for at least the last 800 years, the keeper of the Grail, Joseph of Arimathea, arrived in England in the first century AD. He crossed the Somerset Levels (then flooded) by boat to arrive at the foot of Glastonbury Tor on an island known in Arthurian mythology as Avalon.

At the foot of Wearyall Hill, just beneath the Tor, the tired missionary thrust his staff into the ground, and rested. In the morning, so the story goes, his staff had taken root and grown into an oriental thorn bush now known as the Glastonbury Thorn.

Joseph then went on to found Glastonbury Abbey, and set about converting the locals to Christianity – with a staggering success rate. By 600 AD, England had a Christian king: Ethelbert. Meanwhile the Grail – which, according to some stories, was buried at the entrance to the underworld in Glastonbury – became firmly interwoven into myths about King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table.

Contemporary records mention none of this, though, and the story only became popular after the publication of Robert de Boron’s fanciful poem Joseph d’Arimathie at the end of the 12th century. The area may have been a significant site for pre-Christian communities, but Glastonbury Abbey was almost certainly established by Britons in the early seventh century.

However, stories connecting the dots between the site, Arthurian legend, the presence of the Holy Grail and miracles performed by ‘blood relatives’ of Jesus were all excellent marketing for the pilgrimage trade at Glastonbury. The local monks wholeheartedly endorsed the fables, right up until the Abbey was dissolved in 1539, during the English Reformation.

An early example of this can be seen when, in 1184, a fire destroyed most of the monastic buildings at Glastonbury. A few years later, around the time Joseph d’Arimathie was published, King Arthur and Queen Guinevere’s tomb was miraculously discovered in the cemetery. There was a spike in pilgrimage traffic and the funds needed to rebuild the Abbey.

According to myth, King Arthur’s wizard Merlin still roams Glastonbury Tor. © Alamy

A good story: From medieval poems to modern action movies, the Grail has provided centuries of entertainmentFor two millennia, the legend of the Holy Grail has been reported and contorted by imaginative poets, painters, writers, comedians and filmmakers – to such an extent that the small number of known facts have become increasingly hard to sift from an overwhelming mountain of speculative or purely artistic ideas.

Amateur historians and professional authors have gone off on wild tangents, generating countless pseudo-historical books masquerading as seriously researched non-fiction. Indeed, a vast amount of flimsy and fantastical evidence has been reported as fact to support questionable theories. As a result, the Grail story has assumed a life of its own – one that constantly plays out on the pages of books and websites, and on TV and cinema screens – and each generation consumes a new version of it.

Back in the limelight: Victorian revivalism

During the deeply religious fervour of the Victorian era, medievalism was the all the rage and yarns from the Middle Ages, such as Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur, were constantly being reprinted and consumed by a public hungry for tales of chivalry and salvation.

The quest for the Holy Grail was a recurring theme across the arts throughout the age, but everything was based on the medieval myth, rather than known facts and historical events.

Painters began to depict scenes from Arthurian legends, especially members of the ever-earnest Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. When commissioned to decorate Oxford University’s new union building, founder of the Brotherhood Dante Gabriel Rossetti used the Holy Grail as his central theme – thus seeding an awareness and interest in the subject in the fertile minds of future generations of scholars. It was a theme that Rossetti would return to numerous times in his watercolour paintings.

Over several decades, the pre-eminent poet of the era, Alfred Lord Tennyson (Poet Laureate for 40 years during Victoria’s reign), published the epic Idylls of the King, a cycle of twelve narrative poems that retell the legend of King Arthur and his knights – including, of course, the quest for the Grail. These immensely popular poems were dedicated to the late Prince Albert.

William Morris, one of the most significant cultural figures of the era whose talents spanned everything from poetry to interior design, was also acutely interested in the sagas. He wrote verses about the Holy Chalice, and collaborated with Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones to produce vast tapestries depicting the quest for the Grail, which were hung on the walls of the wealthiest businessmen of the industrial age.

This vast Victorian tapestry, named ‘The Achievement of the Grail’ measures 2.4 metres high by nearly 7 metres long. It is currently on display in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. © BAL

20th-century style: The quest on screen

The Grail has been quested after on big and little screens since technology made it possible, but most people will recall the story from at least one of three successful cinematic renditions…

Excalibur (1981), was directed by John Boorman and starred Nigel Terry, Helen Mirren, Patrick Stewart and Liam Neeson, among many others. An action-packed adventure fantasy, it follows the story of King Arthur, from the moment he pulls the sword from the stone, to the quest for the Grail (via Guinevere and Lancelot’s affair). The film, in contrast to most of the medieval literature, has Percival retrieve the Grail for an ailing Arthur, who sips from it and is restored to health.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975), was the Python posse’s first foray into full-length feature films and it is a gloriously ridiculous romp through the Arthurian sagas, with Graham Chapman in the lead role. As the hapless knights search for the Holy Grail they face various challenges and dangers, not least a killer rabbit.

A shot from Monty Python and the Holy Grail. © Kobal

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), the third of Steven Spielberg’s successful series of movies starring Harrison Ford as a swashbuckling archaeologist, sees Indy in action trying to rescue his father (Sean Connery). He then needs to find the Holy Grail before the Nazis get hold of it and use it to achieve world domination. Sound stupid? You might be surprised how close some of the plot elements are to the truth...

Published on December 06, 2015 03:00

History Trivia - Saint-Nicolas Flood wreaks havoc on Northern Dutch coast

December 6

1196 the Northern Dutch coast was flooded; known as the Saint-Nicolas Flood, resulted in widespread damage and death.

1421 Henry VI was born. Henry VI was a child when he came to the throne on the death of his father Henry V. His weakness as a ruler and his occasional displays of mental instability exacerbated the Wars of the Roses (dynastic civil wars for the throne of England fought between supporters of two rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet: the houses of Lancaster and York).

1196 the Northern Dutch coast was flooded; known as the Saint-Nicolas Flood, resulted in widespread damage and death.

1421 Henry VI was born. Henry VI was a child when he came to the throne on the death of his father Henry V. His weakness as a ruler and his occasional displays of mental instability exacerbated the Wars of the Roses (dynastic civil wars for the throne of England fought between supporters of two rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet: the houses of Lancaster and York).

Published on December 06, 2015 02:00

December 5, 2015

7 myths about Robin Hood

Robin Hood, an archetypal figure in English folklore. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

Robin Hood, an archetypal figure in English folklore. (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images) History Extra Myth 1) Robin Hood was a real personRobin Hood is an invented, archetypical hero, whose career encapsulates many of the popular frustrations and ambitions of his era. Robin (or Robert) Hood (aka Hod or Hude) was a nickname given to petty criminals from at least the middle of the 13th century – it may be no coincidence that Robin sounds like ‘robbing’ - but no contemporary writer refers to Robin Hood the famous outlaw we recognise today.

There were men like Robin Hood, however, such as fugitives who flouted the harsh forest laws [unpopular laws that retained vast areas of semi-wild landscape over which the king and his court could hunt], and these fugitives were largely admired by the oppressed peasantry. But the individual(s) whose deeds inspired the legend of Robin Hood may not have been called Robin Hood from birth, or indeed even during in his own lifetime.

Myth 2) Robin lived during the reign of Richard the LionheartRobin Hood is often portrayed as the enemy of the ambitious Prince John and the ally of his brother, the imprisoned Richard I (1189–99), but it was Tudor writers of the 16th century who first brought the three men together in this context.

Alternatively, Robin Hood has been identified (not very convincingly) with one of a number of Robin Hoods mentioned in the Wakefield Court Rolls during the reign of Edward II (1307–27), and, more probably, as a disinherited supporter of Simon de Montfort, who was slain at Evesham in 1265.

All we can say with certainty is that Robin the Outlaw had entered popular mythology by the time William Langland wrote The Vision of Piers Plowman in 1377. In it, Sloth the chaplain says: “I kan nought parfitly my Paternoster as the preest it syngeth, But I kan rymes of Robyn Hood and Randolf, Erl of Chestre.”

Unfortunately, it is not clear if Robin was associated with Ranulf ‘de Blundeville’, earl of Chester (d1232) in some way, or if the ‘rymes’ about them sprang from entirely separate traditions.

Myth 3) Robin Hood was a philanthropist who robbed the rich to give to the poorIt was the Scottish historian John Major who in 1521 wrote that “[Robin] permitted no harm to women, nor seized the goods of the poor, but helped them generously with what he took from abbots”.

But earlier ballads are more reticent: the longest, and possibly also the oldest, rhyme or ballad about Robin Hood is The Lyttle Geste of Robyn Hode, believed to have been written down c1492–1510 but probably composed c1400. It concludes with the comment that Robin “did poor men much good”.

Robin Hood, printed by Wynkyn de Worde. Caption reads: "A lytell geste of Robin Hode". (Photo by Culture Club/Getty Images)

But while Robin is willing to lend to a knight who finds himself in financial difficulties, in The Lyttle Geste and in other early ballads there is no mention of money being distributed among the peasants or of society being reordered to their advantage. On the contrary, stories that have the outlaws mutilating a vanquished enemy and even killing a child on one occasion show them in a quite different light.

Myth 4) Robin was a dispossessed nobleman, the Earl of HuntingtonAgain, there is no real basis for this theory – the Robin of the early ballads is always a yeoman, and his attitudes are those of his class.

So from where did the idea originate? John Leland, writing in the 1530s, refers to Robin as a nobilis exlex – a noble outlaw, meaning, in all probability, that he was high-minded. And in 1569 historian Richard Grafton claimed to have found evidence in an “old and ancient pamphlet” that Robin had been “advanced to the dignity of an earl” on account of his “manhood and chivalry”; an idea subsequently popularised by Anthony Munday in his plays The Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntington, and The Death of Robert, Earl of Huntington, both written in 1598.

Furthermore, Martin Parker’s A True Tale of Robin Hood, published in 1632, stated unequivocally that the “renowned outlaw, Robert Earl of Huntington, vulgarly called Robin Hood, lived and died in AD 1198”, but the real Earl of Huntingdon (the only possible interpretation of ‘Huntington’) at this date was David of Scotland, who died in 1219. Following the death of David’s son, John, in 1237, there were no more earls of Huntingdon until the title was granted to William de Clinton a century later.

Myth 5) Robin married Maid Marian at St Mary’s Church in EdwinstoweMaid Marian is now as much a part of the Robin Hood story as Robin himself, yet she was originally the subject of a separate series of ballads. Curiously, the Robin and the outlaws of the earliest stories do not appear to have had wives or families – the only slight feminine interest was Robin’s devotion to the Virgin Mary.

The storytellers may have thought this devotion inappropriate in the years after the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, and Marian may have been incorporated into the tales at this time to provide an alternative female focus. The ‘marriage’ of Robin and Marian inevitably followed.

c1880: Robin Hood and Maid Marian. (Photo by Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

Myth 6) Robin was buried at Kirklees Priory in Yorkshire and his grave can today be seen thereAccording to legend, Robin went to Kirklees Priory for medical treatment (date unknown), was deliberately over-bled by the prioress, and with his last ounce of strength shot an arrow indicating where he wanted to be buried.

However, the Tudor writer Richard Grafton thought that the prioress had interred Robin by the side of the road: “Where he had used to rob and spoyle those that passed that way. And upon his grave the sayde prioresse did lay a very fayre stone, wherein the names of Robert Hood, William of Goldesborough, and others were graven. And the cause why she buryed him there was, for that the common strangers and travailers, knowyng and seeyng him there buryed, might more safely and without feare take their jorneys that way, which they durst not do in the life of the sayd outlawes. And at either end of the sayde tombe was erected a crosse of stone, which is to be seen there at this present”.

A drawing made by the Pontefract antiquarian Nathaniel Johnston in 1665 shows a slab decorated with a cross ‘fleuree’ (the standing crosses had presumably disappeared by his day), and the inscription “Here lie Roberd Hude, Willm Goldburgh, Thoms…” carved round the edge. Nothing is known of William of Goldesborough or Thomas, and the inscription was said to be “scarce legible” some years before Johnston drew it. Robin Hood could have been buried in a grave that already contained other bodies, but if the monument was erected shortly after his death (whenever that was), it is curious that there is no mention of it before about 1540.

Kirklees Priory came into the possession of the Armitage family following the Dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century, and in the 18th century Sir Samuel Armitage had the ground beneath the stone excavated to a depth of three feet. His main fear was that grave robbers had been there before him, but in fact the real problem was the lack of a grave to rob. The site did not appear to have been dug previously, and Armitage concluded that the memorial had been “brought from some other place, and by vulgar tradition ascribed to Robin Hood”.

The stone was regularly attacked by souvenir hunters and by others who believed that pieces of it could cure toothache. The Armitages subsequently enclosed the site within a low brick wall topped by iron railings, the remains of which are still visible today.

Myth 7) Some of Robin’s friends, and equally some of his protagonists, can be identified with persons known to historyLittle John, Will Scarlett and Much the Miller’s son are associated with Robin in the earliest ballads, but other members of his band – Friar Tuck, Alan a Dale, etc – were added later. Of these, Little John is undoubtedly the most prominent, but there are almost as many references to Little Johns – or John Littles – in contemporary documents as there are to Robin Hoods. The historical John is as elusive as his master, but what is alleged to be his grave in Hathersage churchyard in Derbyshire is not without interest. The stones and railings are modern, but part of an earlier memorial, bearing the weathered initials ‘L’ and ‘I’ (which looks like a ‘J’) can still be seen in the church porch.

c1600: the legendary hero and outlaw of medieval England Robin Hood with one of his Merrie Men, Little John. Original publication from the Roxburghe Ballads. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images).

James Shuttleworth, who owned the manor, excavated the site in 1784, and found a particularly large femur 28½ inches long – a bone that is said to have been responsible for much ill luck until it was finally reburied. Two cottages, one in Little Haggas Croft at Loxley (Yorkshire) and the other in Hathersage (a village in the Peak District in Derbyshire), were said to be the houses in which Robin was born and in which Little John spent his final years respectively; but Robin’s was ruinous by 1637, and John’s was demolished in what was described as “recent times”.

An alternative approach has been to try to place Robin in a particular historical context by identifying some of his opponents, but the ballads refer merely to the Sheriff of Nottingham; the Abbot of St Mary’s, York; and others only by these titles – never to named individuals who held the offices between known dates. The lack of precise information is frustrating, but we should always remember that we are here dealing with popular literature, not with documents intended to record facts.

David Baldwin is the author of Robin Hood: The English Outlaw Unmasked (Amberley Publishing, 2010; reprinted in 2011).

Published on December 05, 2015 03:00

History Trivia - French Franc created

December 5

63 BC Marcus Tullius Cicero, the consul of Rome, read the last of his Catiline Orations, exposing to the Roman Senate the plot of Lucius Sergius Catilina and his allies to overthrow the Roman government.

1360 The French Franc was created.

1456 Earthquake struck Naples and about 35,000 died.

63 BC Marcus Tullius Cicero, the consul of Rome, read the last of his Catiline Orations, exposing to the Roman Senate the plot of Lucius Sergius Catilina and his allies to overthrow the Roman government.

1360 The French Franc was created.

1456 Earthquake struck Naples and about 35,000 died.

Published on December 05, 2015 02:30

December 4, 2015

A brief history of how we fell in love with caffeine and chocolate

History Extra

A heated debate in a coffee house on Bride Lane, Fleet Street in London, c1688. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images) These everyday beverages, so integral to British life, all originally came from far-flung regions: coffee from the Arabian peninsula, tea from China, and chocolate from Mesoamerica. By a strange coincidence, all arrived on our shores almost simultaneously during the middle of the 17th century, causing much debate about their benefits (or otherwise) to the health of the nation.

A heated debate in a coffee house on Bride Lane, Fleet Street in London, c1688. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images) These everyday beverages, so integral to British life, all originally came from far-flung regions: coffee from the Arabian peninsula, tea from China, and chocolate from Mesoamerica. By a strange coincidence, all arrived on our shores almost simultaneously during the middle of the 17th century, causing much debate about their benefits (or otherwise) to the health of the nation. Here, Melanie King, the author of Tea, Coffee & Chocolate: How We Fell in Love with Caffeine, explores the origins of our obsession with caffeine and chocolate…

We may think of the 1650s as a time of puritanical austerity, with the banning of holly wreaths and the closing of theatres. But it was during these years of austerity that tea, coffee, and chocolate first went on sale in Britain. The first cup of coffee appears to have been served in 1650, in the Angel Inn in Oxford, where an enterprising Jewish merchant began the long tradition of seeing students through their exams.

The first cup of hot chocolate came seven years later, when in 1657 an advertisement informed the public that they could enjoy “an excellent West Indian drink called chocolate” at a house in Queen’s Head Alley, Bishopsgate. One year later, a “China drink, called by the Chineans Tcha,” was advertised as being sold at the Sultaness Head Coffee-House by the Royal Exchange. Tea was still an exotic novelty three years later, when Samuel Pepys reported in his diary that he had a cup of tea, “of which I had never drank before”.

The sudden arrival of these three new beverages, all from distant foreign parts, immediately became the source of much curiosity, anxiety, and debate. Entrepreneurs extolled their health benefits, while sceptics made equally dubious announcements about their supposed harmful effects. For example, a 1664 treatise by a tea merchant, entitled An Exact Description of the Growth, Quality and Vertues of the Leaf Tea, confidently claimed that tea “vanquisheth heavie Dreams, easeth the Brain, strengthneth the Memory”, while making the body “active and lusty”. As Pepys discovered, apothecaries recommended cups of tea as a decongestant.

Coffee was also widely promoted as a ‘cure-all’. A 1660 advertisement by James Gough, who sold coffee in Oxford, stated that coffee had so many advantages that “it would be too tedious to nominate everything it is good for”. He nevertheless proceeded to give potential customers a long list that included consumption, gout, spleen, dropsy, rheumatism, headaches, and digestion. It was also effective, he pointedly noted, in banishing drowsiness in “students or others who are to sit up late, or all night”. One of the grandest claims for coffee, made in 1721, was that it stopped the spread of the bubonic plague.

Chocolate, meanwhile, was promoted by various treatises, advertisements, and poems, such as In Praise of Chocolate by James Wadsworth (who wrote under the compelling pseudonym Don Diego de Vadesforte). A “lick of chocolate”, Wadsworth claimed, not only helped women to get pregnant but, nine months later, eased the pains and length of childbirth! The cosmetic effects were equally irresistible: “Twill make Old women Young and Fresh.” Little wonder that fashionable women were soon sipping chocolate in bed, assisted by a special vessel, the mancerina, that prevented them from spilling the liquid onto their sheets.

Such bold claims about these new drinks did not go unchallenged. Equally vocal bands of detractors blamed the beverages for undermining the health, morale, and industry of the nation. The fact that they were to be drunk hot became a source of concern, since hot liquids were believed to boil the blood and therefore upset the balance of the four humours [the ancient Greek theory that the health of the body was controlled by four bodily fluids – blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm]. The perils of drinking hot liquids were graphically illustrated by a Fellow of the Royal Society, Dr Stephen Hales, who studied the effects of dipping a suckling pig’s tail in a cup of tea.

Smart gentlemen drinking, smoking and chatting in a coffee house, c1668. (Photo by Rischgitz/Getty Images)

Other alarming claims were made about tea drinking: it supposedly enfeebled the spirits, dried the brain, caused people to commit suicide, and led to a drop in productivity among workers, since even the lowliest labourers, as one opponent furiously noted, downed tools to enjoy a cup of tea. Coffee fared little better – it was denounced in a poem as a “decoction of the devils”, while a 1661 broadsheet claimed that it made men effeminate. In 1674, another broadsheet elaborated the effects of coffee on masculine performance, deploring this ‘heathenish liquor’ for making men unable to discharge their conjugal duties. The women of Britain were, as a result of their men sipping coffee, “languishing in an extremity of want”.

If coffee was suspect because it came from ‘heathen’ lands – the Middle East – chocolate raised suspicions because it was associated with Catholics: the Spanish monks and conquistadors who had been the first Europeans to sample and export it. Its use in Aztec rituals (it sometimes served as a substitute for blood) was also a cause for suspicion. A physician and naturalist named Martin Lister noted that chocolate may have been a suitable drink for “wild Indians” but was hardly one for the “pampered” British.

In the 1660s, chocolate even played a part in a high society sex scandal, when one of the mistresses of the Duke of York (the future James VII and II), Lady Denham, fell ill and died. The poet Andrew Marvell reported that the venom had apparently been administered in a cup of “mortal Chocolate”. An autopsy ruled out any toxin, though it also claimed (as the sceptical Samuel Pepys noted) that she had died a virgin.

Despite their many opponents, all three beverages – tea, coffee, and hot chocolate – became an established part of the British diet, and advice was quickly produced on how best to prepare and enjoy them. The philosopher and courtier Sir Kenelm Digby suggested that tea should be steeped for no longer than it took to recite Psalm 51 (about three minutes).

Pasqua Rosee, an Armenian immigrant who ran London’s first coffee shop, offered advice on how to make and drink a cup of coffee: the grounds should, he said, be boiled with spring water, the liquid then drunk on an empty stomach with no food taken for an hour afterwards. A recipe from 1667 recommended mixing coffee powder with equal quantities of butter and salad oil, proving that today’s trends such as bulletproof coffee – a mixture of coffee and butter – are nothing new. Meanwhile a doctor named Benjamin Moseley suggested that those suffering from flatulence or scurvy might wish to add mustard to their coffee.

Coffee was often consumed in coffee houses, which in London became venues for gossip, political debate and, in the eyes of the authorities, sedition. A publication entitled Rules and Orders of the Coffee House pointed out that, in these establishments, “people of all qualities and conditions” gathered, with no consideration for ranks or titles. Charles II grew so worried about the subversive political effects of coffee houses that in 1675 he ordered their closure. Such was the public indignation that within days he was forced to rescind his proclamation. Within a few decades, by the early 18th century, there were around 3,000 coffee houses in England.

Chocolate, too, was drunk in special establishments. Unlike coffee, it was not a democratic drink that catered to all ranks of society. More expensive than both tea and coffee, chocolate became the drink of the affluent. Consequently, chocolate houses – White’s, Ozinda’s, and the Cocoa Tree – were found in the aristocratic area around Pall Mall in London. Chocolate was often spiced up with exotic ingredients. It was used for dipping wigg bread (a bread spiced with cloves, nutmeg and caraway seeds), and it might be stirred into wine, brandy, port, or sherry. Pepys’s first encounter with chocolate was in a tavern where, as a hangover cure, it was mixed with his morning draft of wine.

Odd as some of these complaints and prescriptions might seem to us today, the health benefits of coffee, tea, and chocolate are still today the subject of much debate and scientific study. We may not have broadsheets anymore, but the internet is full of testimony about the pros and cons of drinking coffee; the fat-burning and cancer-fighting properties of green tea; and the cholesterol-lowering and memory-boosting powers of chocolate. These three drinks have as strong a hold on us as ever.

Melanie King is a freelance writer of historical non-fiction. Her book Tea, Coffee & Chocolate: How We Fell in Love with Caffeine (Bodleian Publishing) is out now. To find out more, click here.

Published on December 04, 2015 03:00