MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 135

November 20, 2015

History Trivia - Barons swear fealty to Edward I of England

November 20

869 Edmund the Martyr died. Saint Edmund was king of East Anglia. His gruesome death at the hands of the Danes led to legends and a shrine at what is now Bury St. Edmund's, West Suffolk.

1272 Barons swore fealty to Edward I. Upon the death of his father, King Henry III, Edward received the fealty of the English barons and succeeded to the throne.

1407 a truce between John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy and Louis of Valois, Duke of Orleans was agreed under the auspices of John, Duke of Berry. Orleans was assassinated three days later by Burgundy.

869 Edmund the Martyr died. Saint Edmund was king of East Anglia. His gruesome death at the hands of the Danes led to legends and a shrine at what is now Bury St. Edmund's, West Suffolk.

1272 Barons swore fealty to Edward I. Upon the death of his father, King Henry III, Edward received the fealty of the English barons and succeeded to the throne.

1407 a truce between John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy and Louis of Valois, Duke of Orleans was agreed under the auspices of John, Duke of Berry. Orleans was assassinated three days later by Burgundy.

Published on November 20, 2015 01:30

November 19, 2015

History Trivia - The Council of Clermont called

November 19

1095 The Council of Clermont, called by Pope Urban II to discuss sending the First Crusade to the Holy Land, began.

1367 League of Cologne (medieval military alliance against Denmark signed by cities of the Hanseatic League on their meeting called Hansetag in Cologne) approved war against Denmark and Norway.

1095 The Council of Clermont, called by Pope Urban II to discuss sending the First Crusade to the Holy Land, began.

1367 League of Cologne (medieval military alliance against Denmark signed by cities of the Hanseatic League on their meeting called Hansetag in Cologne) approved war against Denmark and Norway.

Published on November 19, 2015 00:30

November 18, 2015

Researchers locate Submerged Lost Ancient City where Athens and Sparta Fought a Battle

Ancient Origins

Researchers have found the location of the lost island city of Kane, known since ancient times as the site of a naval battle between Athens and Sparta in which the Athenians were victorious but later executed six out of eight of their own commanders for failing to aid the wounded and bury the dead.

Researchers have found the location of the lost island city of Kane, known since ancient times as the site of a naval battle between Athens and Sparta in which the Athenians were victorious but later executed six out of eight of their own commanders for failing to aid the wounded and bury the dead.

Some historians say the loss of leadership may have contributed to Athens’ loss of the Peloponnesian War. But a scholar who wrote a book on the battle says the Spartans would have won whether or not Athens executed the generals.

The ancient city of Kane was on one of three Arginus Islands in the Aegean Sea off the west coast of Turkey. The exact location of the city was lost in antiquity because earth and silt displaced the water and connected the island to the mainland.

Geo-archaeologists working with other experts from Turkish and German institutions discovered Kane, where the Athens and Sparta did battle in 406 BC. Athens won the Battle of Arginusae, but its citizens tried and executed six of eight of the city-state’s victorious commanders.

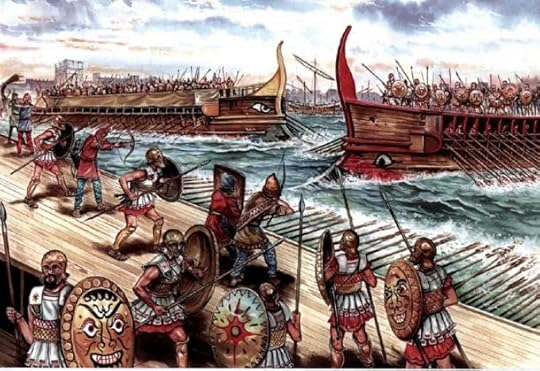

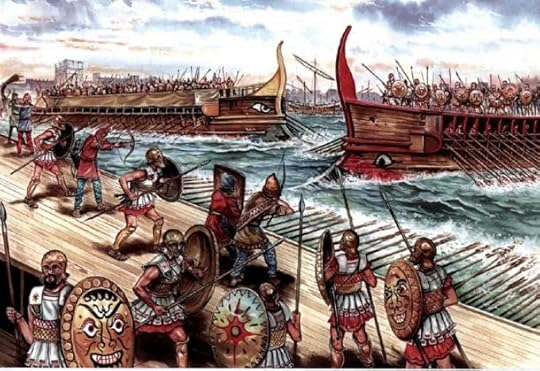

Depiction of a battle between Athens and Sparta in the Great Peloponnese War, 413 BC. (

Image source

) “The Athenian people soon regretted their decision, but it was too late,” writes J. Rickard at History of War. “The execution of six victorious generals had a double effective—it removed most of the most able and experienced commanders, and it discouraged the survivors from taking command in the following year. This lack of experience may have played a part in the crushing Athenian defeat at Aegospotami that effectively ended the war.”

Depiction of a battle between Athens and Sparta in the Great Peloponnese War, 413 BC. (

Image source

) “The Athenian people soon regretted their decision, but it was too late,” writes J. Rickard at History of War. “The execution of six victorious generals had a double effective—it removed most of the most able and experienced commanders, and it discouraged the survivors from taking command in the following year. This lack of experience may have played a part in the crushing Athenian defeat at Aegospotami that effectively ended the war.”

Debra Hamel, a classicist and historian who wrote the book The Battle of Arginusae, however, says she thinks Athens would have lost anyway.

“Sparta at that point was being funded by Persia, so they could replace ships and hire rowers indefinitely,” Dr. Hamel wrote to Ancient Origins in electronic messages. “Athens did not have those resources. Allies had revolted. They weren’t taking in the money they had in earlier days.”

Google Earth image shows the general vicinity of the islands, near Bademli Village in Turkey on the Aegean Sea.Dr. Hamel, via e-mail, describes how the Battle of Arginusae was likely fought:

Google Earth image shows the general vicinity of the islands, near Bademli Village in Turkey on the Aegean Sea.Dr. Hamel, via e-mail, describes how the Battle of Arginusae was likely fought:

Greek trireme, drawing by F. Mitchell; note the battering ram on the prow to the right at the waterline. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Dr. Hamel’s book on the battle explores not just the battle but its aftermath too. Winning the battle “was a great triumph, saving Athens—at least temporarily—from almost certain defeat in the war,” she wrote in e-mail. “The victory was cause for celebration, but paradoxically, because of what happened afterwards, it was also one of the worst disasters to befall Athens in the war: A series of legal proceedings led ultimately to the Athenians' execution of (most of) their victorious generals. This was the stuff of tragedy.

Greek trireme, drawing by F. Mitchell; note the battering ram on the prow to the right at the waterline. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Dr. Hamel’s book on the battle explores not just the battle but its aftermath too. Winning the battle “was a great triumph, saving Athens—at least temporarily—from almost certain defeat in the war,” she wrote in e-mail. “The victory was cause for celebration, but paradoxically, because of what happened afterwards, it was also one of the worst disasters to befall Athens in the war: A series of legal proceedings led ultimately to the Athenians' execution of (most of) their victorious generals. This was the stuff of tragedy.

The island on which Kane was situated, which is known from ancient historians’ texts, is in the sea off İzmir Province’s Dikili district Researchers, led by the German Archaeology Institute, included those from the cities of İzmir, Munich, Kiel, Cologne, Karlsruhe, Southampton and Rostock. Prehistorians, geographers, geophysics experts and topographers all worked on the project.

“During surface surveys carried out near Dikili’s Bademli village, geo-archaeologists examined samples from the underground layers and learned one of the peninsulas there was in fact an island in the ancient era, and its distance from the mainland was filled with alluviums over time,” reports Hurriyet Daily News. “Following the works, the quality of the harbors in the ancient city of Kane was revealed. Also, the location of the third island, which was lost, has been identified.”

Featured image: Main: Google Earth image shows the general vicinity of the islands, near Bademli Village in Turkey on the Aegean Sea. Inset: A representation of an ancient Greek ship on pottery (Photo by Poecus/ Wikimedia Commons )

By Mark Miller

Researchers have found the location of the lost island city of Kane, known since ancient times as the site of a naval battle between Athens and Sparta in which the Athenians were victorious but later executed six out of eight of their own commanders for failing to aid the wounded and bury the dead.

Researchers have found the location of the lost island city of Kane, known since ancient times as the site of a naval battle between Athens and Sparta in which the Athenians were victorious but later executed six out of eight of their own commanders for failing to aid the wounded and bury the dead.Some historians say the loss of leadership may have contributed to Athens’ loss of the Peloponnesian War. But a scholar who wrote a book on the battle says the Spartans would have won whether or not Athens executed the generals.

The ancient city of Kane was on one of three Arginus Islands in the Aegean Sea off the west coast of Turkey. The exact location of the city was lost in antiquity because earth and silt displaced the water and connected the island to the mainland.

Geo-archaeologists working with other experts from Turkish and German institutions discovered Kane, where the Athens and Sparta did battle in 406 BC. Athens won the Battle of Arginusae, but its citizens tried and executed six of eight of the city-state’s victorious commanders.

Depiction of a battle between Athens and Sparta in the Great Peloponnese War, 413 BC. (

Image source

) “The Athenian people soon regretted their decision, but it was too late,” writes J. Rickard at History of War. “The execution of six victorious generals had a double effective—it removed most of the most able and experienced commanders, and it discouraged the survivors from taking command in the following year. This lack of experience may have played a part in the crushing Athenian defeat at Aegospotami that effectively ended the war.”

Depiction of a battle between Athens and Sparta in the Great Peloponnese War, 413 BC. (

Image source

) “The Athenian people soon regretted their decision, but it was too late,” writes J. Rickard at History of War. “The execution of six victorious generals had a double effective—it removed most of the most able and experienced commanders, and it discouraged the survivors from taking command in the following year. This lack of experience may have played a part in the crushing Athenian defeat at Aegospotami that effectively ended the war.”Debra Hamel, a classicist and historian who wrote the book The Battle of Arginusae, however, says she thinks Athens would have lost anyway.

“Sparta at that point was being funded by Persia, so they could replace ships and hire rowers indefinitely,” Dr. Hamel wrote to Ancient Origins in electronic messages. “Athens did not have those resources. Allies had revolted. They weren’t taking in the money they had in earlier days.”

Google Earth image shows the general vicinity of the islands, near Bademli Village in Turkey on the Aegean Sea.Dr. Hamel, via e-mail, describes how the Battle of Arginusae was likely fought:

Google Earth image shows the general vicinity of the islands, near Bademli Village in Turkey on the Aegean Sea.Dr. Hamel, via e-mail, describes how the Battle of Arginusae was likely fought:The Battle of Arginusae was only fought at sea. … The state-of-the-art vessel of the period was the trireme, a narrow ship about 120 feet [36.6 meters] long that was powered by 170 oarsmen, who sat in three rows on either side of the ship. There was a bronze-clad ram that extended about six and a half feet [2 meters] at waterline from the prow of the vessel. The purpose of the ram was to sink enemy ships. The goal of a ship's crew—the 170 oarsmen and various officers onboard—was to maneuver a trireme so that it was in position to punch a hole in the side of an enemy ship while avoiding getting rammed oneself. In order to do this you needed to have a fast ship--one that wasn't waterlogged or weighed down by marine growths--and you needed a well-trained crew.Athens sent 150 ships, the Spartans 120. The Athenian line was about 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) long or longer because it was interrupted by one of the Arginusae islands. The Spartan line was a bit less than 1.5 miles [2.4 km] long, Dr. Hamel estimates.

Greek trireme, drawing by F. Mitchell; note the battering ram on the prow to the right at the waterline. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Dr. Hamel’s book on the battle explores not just the battle but its aftermath too. Winning the battle “was a great triumph, saving Athens—at least temporarily—from almost certain defeat in the war,” she wrote in e-mail. “The victory was cause for celebration, but paradoxically, because of what happened afterwards, it was also one of the worst disasters to befall Athens in the war: A series of legal proceedings led ultimately to the Athenians' execution of (most of) their victorious generals. This was the stuff of tragedy.

Greek trireme, drawing by F. Mitchell; note the battering ram on the prow to the right at the waterline. (

Wikimedia Commons

)Dr. Hamel’s book on the battle explores not just the battle but its aftermath too. Winning the battle “was a great triumph, saving Athens—at least temporarily—from almost certain defeat in the war,” she wrote in e-mail. “The victory was cause for celebration, but paradoxically, because of what happened afterwards, it was also one of the worst disasters to befall Athens in the war: A series of legal proceedings led ultimately to the Athenians' execution of (most of) their victorious generals. This was the stuff of tragedy.Because the Battle of Arginusae is tied intimately with the legal proceedings that it led to, I was able to discuss in my book not only the battle itself and the intricacies of naval warfare (which are really very interesting), but also the proceedings back in Athens and Athens' democracy and democratic institutions. All of this was necessary to round out the story for readers who are approaching the book without any prior knowledge of the period.Later, from 191 to 190 BC, Roman forces used the city of Kane’s harbor in the war against Antiochas III’s Seleucid Empire. That war lasted from 192 to 188 BC and ended when Antiochus capitulated to Rome’s condition that he evacuate Asia Minor. Most of Antiochus’ cities in Asia Minor had been conquered by the Romans anyway. He also agreed to pay 15,000 Euboeic talents. The Romans did not leave a garrison in Asia Minor but wanted a buffer zone on their eastern frontier.

The island on which Kane was situated, which is known from ancient historians’ texts, is in the sea off İzmir Province’s Dikili district Researchers, led by the German Archaeology Institute, included those from the cities of İzmir, Munich, Kiel, Cologne, Karlsruhe, Southampton and Rostock. Prehistorians, geographers, geophysics experts and topographers all worked on the project.

“During surface surveys carried out near Dikili’s Bademli village, geo-archaeologists examined samples from the underground layers and learned one of the peninsulas there was in fact an island in the ancient era, and its distance from the mainland was filled with alluviums over time,” reports Hurriyet Daily News. “Following the works, the quality of the harbors in the ancient city of Kane was revealed. Also, the location of the third island, which was lost, has been identified.”

Featured image: Main: Google Earth image shows the general vicinity of the islands, near Bademli Village in Turkey on the Aegean Sea. Inset: A representation of an ancient Greek ship on pottery (Photo by Poecus/ Wikimedia Commons )

By Mark Miller

Published on November 18, 2015 03:30

History Trivia - William Tell shoots an apple of his son's head

November 18

1307 William Tell shot an apple off of his son's head. The historical existence of Tell is disputed. According to popular legend, he was a peasant from Bürglen in the canton of Uri in the 13th and early 14th centuries who defied Austrian authority, was forced to shoot an apple from his son’s head, was arrested for threatening the governor’s life, saved the same governor’s life en route to prison, escaped, and ultimately killed the governor in an ambush. These events supposedly helped spur the people to rise up against Austrian rule.

1421 A seawall at the Zuiderzee dike in the Netherlands broke, flooding 72 villages and killing about 10,000 people.

1477 William Caxton produced Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres, the first book printed on a printing press in England.

1307 William Tell shot an apple off of his son's head. The historical existence of Tell is disputed. According to popular legend, he was a peasant from Bürglen in the canton of Uri in the 13th and early 14th centuries who defied Austrian authority, was forced to shoot an apple from his son’s head, was arrested for threatening the governor’s life, saved the same governor’s life en route to prison, escaped, and ultimately killed the governor in an ambush. These events supposedly helped spur the people to rise up against Austrian rule.

1421 A seawall at the Zuiderzee dike in the Netherlands broke, flooding 72 villages and killing about 10,000 people.

1477 William Caxton produced Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres, the first book printed on a printing press in England.

Published on November 18, 2015 02:00

November 17, 2015

Gladiator Colosseum Found in Tuscany

Discovery News

Italian archaeologists have unearthed remains of an oval structure that might represent the most important Roman amphitheater finding over the last century.

Italian archaeologists have unearthed remains of an oval structure that might represent the most important Roman amphitheater finding over the last century.The foundations of the colosseum, which is oval-shaped like the much larger arena in the heart of Rome, were found in the town of Volterra and might date back to the 1st century A.D. Amphitheaters like these were used during Roman times to feature events including gladiator combats and wild animal fights.

The archaeologists estimate this structure measured some 262 by 196 feet, although only a small part of it has been unearthed.

“This amphitheater was quite large. Our survey dig revealed three orders of seats that could accommodate about 10,000 people. They were entertained by gladiators fights and wild beast baiting,” Elena Sorge, the archaeologist of the Tuscan Superintendency in charge of the excavation, told Discovery News.

By comparison, the Colosseum in Rome could seat more than 50,000 spectators during public games.

“The finding sheds a new light on the history of Volterra, which is most famous for its Etruscan legacy. It shows that during the emperor Augustus’s rule, it was an important Roman center,” she added.

Photos: Bronze-Age Battle Frozen in Time

One of the most powerful Etruscan cities, Volterra fell under Roman rule in the 1st century B.C.

The most striking monument dating to the Roman period is a theater built in the Augustan age, which is one of the finest and best preserved Roman theaters in Italy. It stands about a mile from the newly discovered arena.

With the help of ground penetrating radar and a digital survey by Carlo Battini, of the University of Genoa, Dicca Department, the archaeologists were able to estimate that much of the amphitheater lies at a depth of 20 to 32 feet. So far the survey dig has been funded by the Cassa di Risparmio bank of Volterra.

“We are hoping to find more sponsors and funding to excavate this wonder. We believe that within three years it could be fully brought to light,” Sorge said.

Roman Gladiators Drank Ash Energy Drink

The amphiteater was made from stone and decorated in “panchino,” a typical Volterra stone used since Etruscan time to build the town’s walls. It features the same construction technique used to raise the nearby theater.

The archaeologists have so far brought to light a large sculpted stone and the vaulted entrance to a cryptoporticus, or covered passageway. Such corridor would have possibly housed the gladiators just before they entered the arena

“It’s puzzling that no historical account records the existence of such an imposing amphitheater. Possibly, it was abandoned at a certain time and gradually covered by vegetation,” Sorge said.

by Rossella Lorenzi

Published on November 17, 2015 03:00

History Trivia - Elizabethan era begins

November 17

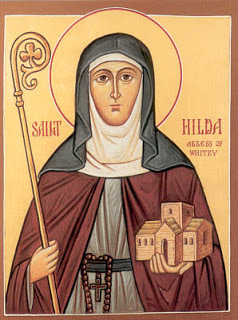

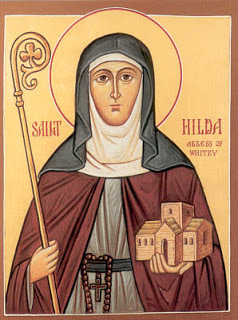

680 Saint Hild of Whitby died. Hild or Hilda founded Streaneshalch Abbey (now Whitby) and was one of the most renowned abbesses of Anglo-Saxon England.

1558 Elizabethan era began. Queen Mary I of England died and was succeeded by her half-sister Elizabeth I of England who was not officially crowned until January.

680 Saint Hild of Whitby died. Hild or Hilda founded Streaneshalch Abbey (now Whitby) and was one of the most renowned abbesses of Anglo-Saxon England.

1558 Elizabethan era began. Queen Mary I of England died and was succeeded by her half-sister Elizabeth I of England who was not officially crowned until January.

Published on November 17, 2015 01:30

November 16, 2015

A brief history of medieval magic

History Extra

Want to get rid of an unwanted husband? Coat yourself in honey, roll naked in grain and cook him up some deadly bread with flour milled from this mixture. Want to increase the amount of supplies in your barn? Leave out child-sized shoes and bows-and-arrows for the satyrs and goblins to play with. If you’re lucky, they might steal some of your neighbour’s goods for you in return. These unusual charms and medical tips, which featured in medieval books, sound suspiciously like magic.

Want to get rid of an unwanted husband? Coat yourself in honey, roll naked in grain and cook him up some deadly bread with flour milled from this mixture. Want to increase the amount of supplies in your barn? Leave out child-sized shoes and bows-and-arrows for the satyrs and goblins to play with. If you’re lucky, they might steal some of your neighbour’s goods for you in return. These unusual charms and medical tips, which featured in medieval books, sound suspiciously like magic.

But alongside these weird and wonderful spells and superstitions, medieval history paints a picture of a people actually more enlightened than their Renaissance successors. So what was medieval magic really like?

Season of the witchThe now all-too-familiar figure of the ‘witch’ – that frightening old hag with warts on her nose and curses at her fingertips – didn’t appear until the 15th century. Despite being dubbed ‘The Renaissance’ and ‘The Age of Discovery’, the centuries that followed [the Renaissance lasted from the 14th to the 17th century] were witness not only to ruthless witch-hunts, but also to a new belief in the reality of magic.

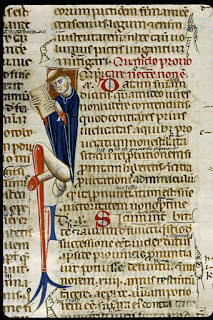

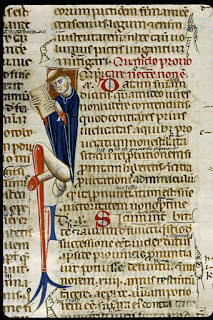

In the Middle Ages, the practice of magic was not yet imagined to be essentially ‘female’. In fact, according to court records from the first half of the 14th century, the majority of those tried for maleficium (meaning sorcery, or dark magic) were men. That was because the most troubling form of magic – necromancy – required not only skill, learning and preparation, but above all education, which was less readily available to women. Necromancy involved conjuring the dead and making them perform feats of transportation or illusion, or asking them to reveal the secrets of the universe. Because many books describing necromancy were Latin translations, anyone wanting to practise the craft would need a good working knowledge of Latin.

It wasn’t until the publication of Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum (or, Hammer of Witches) in 1487 that the specific connection between women and satanic magic became widespread. Kramer warned that “women’s spiritual weakness” and “natural proclivity for evil” made them particularly susceptible to the temptations of the devil. He believed that “all witchcraft comes from carnal lust”, and that women’s “uncontrolled” sexuality made them the likely culprits of any sinister occurrence.

Black sabbathHand-in-hand with this increased emphasis on women came a shift in the perception of magic. Evidence suggests that medieval church authorities (whose successors would later spearhead the witch-hunts) didn’t really believe magic was real – although they still condemned anyone who claimed to practise it.

The 10th-century canon, Episcopi, describes women who, seduced by illusions from the devil, believed they could fly on the backs of “certain beasts” in the middle of the night alongside the goddess Diana. The canon dismissed these women as “stupid” and “foolish” for actually believing that they could accomplish such things. They were criticised in the text for being tricked rather than for practising any real, magical mischief.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, however, inquisitors seemed to believe that women really could make magic happen by entering into pacts with the devil. It was thought that at sabbaths – nocturnal meetings with other witches – women renounced their Christian faith, devoured babies, participated in orgies and committed other carnal and unspeakable acts.

Afterwards, the devils worshipped would watch their women for signs, and then do their bidding. For example, if a witch put her broomstick in water and spoke certain words, a devil might cause a storm or flood. Magic of this kind wasn’t always harmful, however. Witches might be able to heal as a result of a pact, or perform other kinds of positive magic. But, because of their fundamental belief that all magic was carried out by demons and devils, inquisitors condemned it just the same.

Magic or medicine?Certain practices – which sound to us very much like magic – would have been classed as science or medicine in the Middle Ages. William of Auvergne, a 13th-century French priest and bishop, certainly condemned most magic as superstition. However, he admitted that some works of “natural magic” should be viewed as a branch of science: as long as practitioners didn’t use this “natural magic” for evil, they weren’t doing anything criminal. Sealskin could quite happily be used as a charm to repel lightning; vulture body parts could be used as a protective amulet; and gardeners could get virgins to plant their olive trees without any anxiety – this was, after all, a scientific way of promoting their growth.

A number of healing practices from the Middle Ages also sound very much like magic to a modern reader: one doctor instructed physicians to place the herb vervain in their patient’s hand. The presence of the herb would, it was thought, cause the patient to speak his or her fate truthfully, offering the physician an accurate prognosis.

Sympathetic magic was another well-known technique – it used imitation to produce effective results. For example, liver of vulture might be prescribed as medicine for a patient suffering from liver complaints. Meanwhile narrative charms – a complex version of sympathetic magic, hinged on the belief that telling a particular story could help channel healing power to the patient – were usually accompanied by a more ‘medical’ application, like a poultice. According to one medical treatise, wool soaked in olive oil from the Mount of Olives could staunch blood when coupled with a spoken story about Longinus, a man who was famously healed of his blindness by the blood of Christ. Religious elements were blended with the magical.

Although some of these methods were considered superstition by the Christian church in the Middle Ages, they were never associated with demonic magic until the dawning of the witch hunts. Even though women tried for witchcraft were accused of much more diabolical doings than using charms or stories to heal, many women became afraid of carrying out such practices, for fear of attracting suspicion of darker deeds.

Medieval history offers us a magical potion of stories and practices infused with charms, herbs and superstition. While some of the examples might seem curious to us, they are evidence of a people trying to make sense of and control their surroundings – just as we do today.

Hetta Howes is writing a PhD at Queen Mary, University of London on the subject of water and religious imagery in medieval devotional texts by and for women. To find out more, click here.

Would you have been accused of witchcraft in the medieval period? Take our quiz to find out!

Want to get rid of an unwanted husband? Coat yourself in honey, roll naked in grain and cook him up some deadly bread with flour milled from this mixture. Want to increase the amount of supplies in your barn? Leave out child-sized shoes and bows-and-arrows for the satyrs and goblins to play with. If you’re lucky, they might steal some of your neighbour’s goods for you in return. These unusual charms and medical tips, which featured in medieval books, sound suspiciously like magic.

Want to get rid of an unwanted husband? Coat yourself in honey, roll naked in grain and cook him up some deadly bread with flour milled from this mixture. Want to increase the amount of supplies in your barn? Leave out child-sized shoes and bows-and-arrows for the satyrs and goblins to play with. If you’re lucky, they might steal some of your neighbour’s goods for you in return. These unusual charms and medical tips, which featured in medieval books, sound suspiciously like magic.But alongside these weird and wonderful spells and superstitions, medieval history paints a picture of a people actually more enlightened than their Renaissance successors. So what was medieval magic really like?

Season of the witchThe now all-too-familiar figure of the ‘witch’ – that frightening old hag with warts on her nose and curses at her fingertips – didn’t appear until the 15th century. Despite being dubbed ‘The Renaissance’ and ‘The Age of Discovery’, the centuries that followed [the Renaissance lasted from the 14th to the 17th century] were witness not only to ruthless witch-hunts, but also to a new belief in the reality of magic.

In the Middle Ages, the practice of magic was not yet imagined to be essentially ‘female’. In fact, according to court records from the first half of the 14th century, the majority of those tried for maleficium (meaning sorcery, or dark magic) were men. That was because the most troubling form of magic – necromancy – required not only skill, learning and preparation, but above all education, which was less readily available to women. Necromancy involved conjuring the dead and making them perform feats of transportation or illusion, or asking them to reveal the secrets of the universe. Because many books describing necromancy were Latin translations, anyone wanting to practise the craft would need a good working knowledge of Latin.

It wasn’t until the publication of Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum (or, Hammer of Witches) in 1487 that the specific connection between women and satanic magic became widespread. Kramer warned that “women’s spiritual weakness” and “natural proclivity for evil” made them particularly susceptible to the temptations of the devil. He believed that “all witchcraft comes from carnal lust”, and that women’s “uncontrolled” sexuality made them the likely culprits of any sinister occurrence.

Black sabbathHand-in-hand with this increased emphasis on women came a shift in the perception of magic. Evidence suggests that medieval church authorities (whose successors would later spearhead the witch-hunts) didn’t really believe magic was real – although they still condemned anyone who claimed to practise it.

The 10th-century canon, Episcopi, describes women who, seduced by illusions from the devil, believed they could fly on the backs of “certain beasts” in the middle of the night alongside the goddess Diana. The canon dismissed these women as “stupid” and “foolish” for actually believing that they could accomplish such things. They were criticised in the text for being tricked rather than for practising any real, magical mischief.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, however, inquisitors seemed to believe that women really could make magic happen by entering into pacts with the devil. It was thought that at sabbaths – nocturnal meetings with other witches – women renounced their Christian faith, devoured babies, participated in orgies and committed other carnal and unspeakable acts.

Afterwards, the devils worshipped would watch their women for signs, and then do their bidding. For example, if a witch put her broomstick in water and spoke certain words, a devil might cause a storm or flood. Magic of this kind wasn’t always harmful, however. Witches might be able to heal as a result of a pact, or perform other kinds of positive magic. But, because of their fundamental belief that all magic was carried out by demons and devils, inquisitors condemned it just the same.

Magic or medicine?Certain practices – which sound to us very much like magic – would have been classed as science or medicine in the Middle Ages. William of Auvergne, a 13th-century French priest and bishop, certainly condemned most magic as superstition. However, he admitted that some works of “natural magic” should be viewed as a branch of science: as long as practitioners didn’t use this “natural magic” for evil, they weren’t doing anything criminal. Sealskin could quite happily be used as a charm to repel lightning; vulture body parts could be used as a protective amulet; and gardeners could get virgins to plant their olive trees without any anxiety – this was, after all, a scientific way of promoting their growth.

A number of healing practices from the Middle Ages also sound very much like magic to a modern reader: one doctor instructed physicians to place the herb vervain in their patient’s hand. The presence of the herb would, it was thought, cause the patient to speak his or her fate truthfully, offering the physician an accurate prognosis.

Sympathetic magic was another well-known technique – it used imitation to produce effective results. For example, liver of vulture might be prescribed as medicine for a patient suffering from liver complaints. Meanwhile narrative charms – a complex version of sympathetic magic, hinged on the belief that telling a particular story could help channel healing power to the patient – were usually accompanied by a more ‘medical’ application, like a poultice. According to one medical treatise, wool soaked in olive oil from the Mount of Olives could staunch blood when coupled with a spoken story about Longinus, a man who was famously healed of his blindness by the blood of Christ. Religious elements were blended with the magical.

Although some of these methods were considered superstition by the Christian church in the Middle Ages, they were never associated with demonic magic until the dawning of the witch hunts. Even though women tried for witchcraft were accused of much more diabolical doings than using charms or stories to heal, many women became afraid of carrying out such practices, for fear of attracting suspicion of darker deeds.

Medieval history offers us a magical potion of stories and practices infused with charms, herbs and superstition. While some of the examples might seem curious to us, they are evidence of a people trying to make sense of and control their surroundings – just as we do today.

Hetta Howes is writing a PhD at Queen Mary, University of London on the subject of water and religious imagery in medieval devotional texts by and for women. To find out more, click here.

Would you have been accused of witchcraft in the medieval period? Take our quiz to find out!

Published on November 16, 2015 03:00

History Trivia - Codex Justinianus published

November 16

42 BC Tiberius was born. He was Roman Emperor from 14-37 AD, during the adult life of Christ.

534 A second and final revision of the Codex Justinianus (collection of the Roman imperial constitutions mainly referring to those of the age of Hadrian) was published.

1272 King Henry III of England died. Only nine years old when his father, King John, died, Henry was the first English monarch to be crowned while still a child. Upon reaching adulthood, his indifference to tradition and lack of effective ruling ability resulted in the barons forcing him to agree to a series of reforms known as the Provisions of Oxford.

42 BC Tiberius was born. He was Roman Emperor from 14-37 AD, during the adult life of Christ.

534 A second and final revision of the Codex Justinianus (collection of the Roman imperial constitutions mainly referring to those of the age of Hadrian) was published.

1272 King Henry III of England died. Only nine years old when his father, King John, died, Henry was the first English monarch to be crowned while still a child. Upon reaching adulthood, his indifference to tradition and lack of effective ruling ability resulted in the barons forcing him to agree to a series of reforms known as the Provisions of Oxford.

Published on November 16, 2015 02:00

November 15, 2015

Builders under Pharaoh Akhenaten worked so hard they broke their backs

Ancient Origins

When ancient Eygptian pharaoh Akhenaten ordered the construction of the new city of Amarna dedicated to the sun god Aten, more than 20,000 people moved there to do the back-breaking work. The work was so strenuous that it resulted in numerous broken bones, including many fractured spinal bones, says a new study by archaeologists who examined skeletal remains from a commoners’ cemetery at Amarna.

When ancient Eygptian pharaoh Akhenaten ordered the construction of the new city of Amarna dedicated to the sun god Aten, more than 20,000 people moved there to do the back-breaking work. The work was so strenuous that it resulted in numerous broken bones, including many fractured spinal bones, says a new study by archaeologists who examined skeletal remains from a commoners’ cemetery at Amarna.

The same team announced earlier this fall that five men with wounds to their shoulder blades, exhumed from the same cemetery, may have been punished by being stabbed there for unknown crimes. A wall carving from ancient Egypt spells out the stabbing punishment for stealing animal hides. What these men did wrong or who they were is unknown.

Amarna was built around 1330 BC as a place where Aten alone could be worshiped. Other gods were worshiped in other cities, but no other god ever had been or was meant to be worshiped at Amarna, 350 kilometers (217 miles) south of Cairo, the paper says. The authors of the paper have been analyzing and researching the South Tombs Cemetery in Amarna since 2005.

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their children bask in the rays of the sun, Aten, a god that Akhenaten raised above all others. (Photo by Andreas Praefcke/

Wikimedia Commons

)The authors say the city of Amarna was built quickly, in part because of introduction of a standardized limestone building block measure 52.5 by 25 centimeters (20.7 by 9.85 inches). The weight of this block was about 70 kilograms or 154 pounds. The workers carried the blocks production-line style, handing stones down the line to the next person in line. The authors speculate that these heavy blocks caused many of the bad injuries, including degenerative joint disease and fractures, in the Amarna workers.

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their children bask in the rays of the sun, Aten, a god that Akhenaten raised above all others. (Photo by Andreas Praefcke/

Wikimedia Commons

)The authors say the city of Amarna was built quickly, in part because of introduction of a standardized limestone building block measure 52.5 by 25 centimeters (20.7 by 9.85 inches). The weight of this block was about 70 kilograms or 154 pounds. The workers carried the blocks production-line style, handing stones down the line to the next person in line. The authors speculate that these heavy blocks caused many of the bad injuries, including degenerative joint disease and fractures, in the Amarna workers.

The burials in the South Tombs Cemetery were simple, unlike the elaborate tombs of the rich of ancient Egypt. People wrapped their dead in shrouds of linen. Burial containers were rigid mats made of plant material that sometimes had ropes attached for easier carrying from the city to the densely packed cemetery.

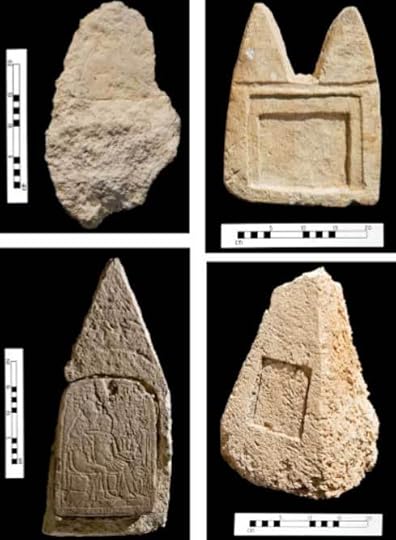

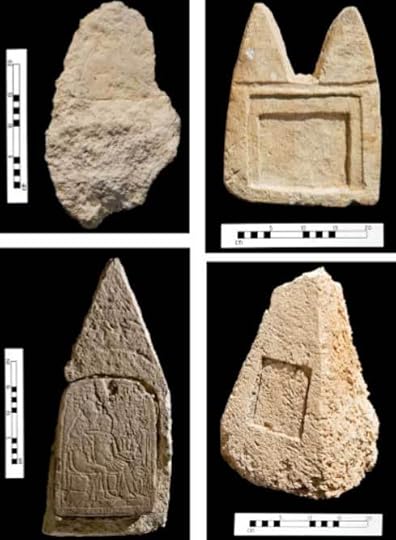

Most of the graves were marked with low cairns of limestone builders, some with memorial steles or gravestones. A few of the graves had small limestone pyramids. Because of erosion and looting very little remains of these surface grave markers, the paper says.

Most of the interments excavated thus far have been disturbed by grave robbers, who tended to rummage through the upper part of the body, probably looking for jewelry, but left much of the bone within the grave. It is usually still possible, nonetheless, to gain a good overall understanding of the nature of each burial, and to reconstruct the skeletons to a substantial degree.

“Grave goods, or items that might have been left beside the grave as offerings during or after burial, are rare.” The team found pottery vessels, most of them fragmentary, which they assumed were used to contain food and beverage; amulets and jewelry among the wrappings or on the body; and cosmetic items, including mirrors, kohl tubes and travertine vessels.

Some of the simple grave markers and steles at Amarna commoners’ cemetery; note the pyramidal shape of the bottom two. (Antiquity photos)Analysis of the skeletons tells a sad tale of the life of the people there. Some of the skeletons showed signs of early childhood hunger, anemia and scurvy. As far as workload injuries, the team found severe degenerative joint disease in at least one limb in nearly 60 percent of the skeletons.

Some of the simple grave markers and steles at Amarna commoners’ cemetery; note the pyramidal shape of the bottom two. (Antiquity photos)Analysis of the skeletons tells a sad tale of the life of the people there. Some of the skeletons showed signs of early childhood hunger, anemia and scurvy. As far as workload injuries, the team found severe degenerative joint disease in at least one limb in nearly 60 percent of the skeletons.

“The spine also exhibited high frequencies of DJD development (56.7 per cent presence; 35.6 percent severe), with the most common severe manifestation being observed in the lumbar region,” the authors wrote. In other words, the lower back was hurt bad from the labor.

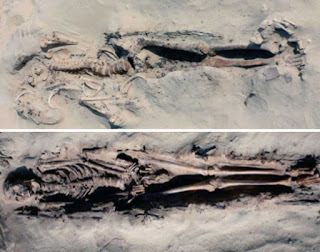

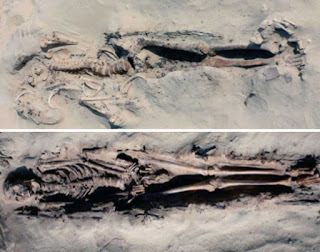

Featured image: An undisturbed skeleton of a man in the extended, supine posture typical at the cemetery; and the burial of a man with a common pattern of disturbance in which the upper torso has been jumbled by robbers and the skull removed. (Antiquity photo)

By: Mark Miller

When ancient Eygptian pharaoh Akhenaten ordered the construction of the new city of Amarna dedicated to the sun god Aten, more than 20,000 people moved there to do the back-breaking work. The work was so strenuous that it resulted in numerous broken bones, including many fractured spinal bones, says a new study by archaeologists who examined skeletal remains from a commoners’ cemetery at Amarna.

When ancient Eygptian pharaoh Akhenaten ordered the construction of the new city of Amarna dedicated to the sun god Aten, more than 20,000 people moved there to do the back-breaking work. The work was so strenuous that it resulted in numerous broken bones, including many fractured spinal bones, says a new study by archaeologists who examined skeletal remains from a commoners’ cemetery at Amarna.“Adult trauma levels at Amarna were also extremely high, with 67.4 per cent (64/95) of adults exhibiting at least one healed, or healing, fracture. This is again consistent with a population working at hard and somewhat dangerous jobs,” says a paper in the journal Antiquity by Barry Kemp, Anna Stevens, Gretchen R. Dabbs, Melissa Zabecki and Jerome C. Rose.The team only examined skeletons with more than 50 percent of the bones remaining and found that in addition to probably work-related fractures and degenerative joint disease, they also had smaller-than-average stature suggesting lifelong malnutrition and other hardships.

The same team announced earlier this fall that five men with wounds to their shoulder blades, exhumed from the same cemetery, may have been punished by being stabbed there for unknown crimes. A wall carving from ancient Egypt spells out the stabbing punishment for stealing animal hides. What these men did wrong or who they were is unknown.

Amarna was built around 1330 BC as a place where Aten alone could be worshiped. Other gods were worshiped in other cities, but no other god ever had been or was meant to be worshiped at Amarna, 350 kilometers (217 miles) south of Cairo, the paper says. The authors of the paper have been analyzing and researching the South Tombs Cemetery in Amarna since 2005.

“The site [of Amarna] reveals something of Akhenaten’s intentions, for it was his wish to purify the cult of the sun (the Aten) by creating a place for worship that was uncontaminated by previous associations, human or divine,” the paper states. “Amarna also became home, almost incidentally, to a population of perhaps 20–30000 people—officials, soldiers, people involved in manufacture and even more whose place in life was to serve others—who followed the royal court to this new city and set about re-establishing their lives and livelihoods.”

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their children bask in the rays of the sun, Aten, a god that Akhenaten raised above all others. (Photo by Andreas Praefcke/

Wikimedia Commons

)The authors say the city of Amarna was built quickly, in part because of introduction of a standardized limestone building block measure 52.5 by 25 centimeters (20.7 by 9.85 inches). The weight of this block was about 70 kilograms or 154 pounds. The workers carried the blocks production-line style, handing stones down the line to the next person in line. The authors speculate that these heavy blocks caused many of the bad injuries, including degenerative joint disease and fractures, in the Amarna workers.

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their children bask in the rays of the sun, Aten, a god that Akhenaten raised above all others. (Photo by Andreas Praefcke/

Wikimedia Commons

)The authors say the city of Amarna was built quickly, in part because of introduction of a standardized limestone building block measure 52.5 by 25 centimeters (20.7 by 9.85 inches). The weight of this block was about 70 kilograms or 154 pounds. The workers carried the blocks production-line style, handing stones down the line to the next person in line. The authors speculate that these heavy blocks caused many of the bad injuries, including degenerative joint disease and fractures, in the Amarna workers.The burials in the South Tombs Cemetery were simple, unlike the elaborate tombs of the rich of ancient Egypt. People wrapped their dead in shrouds of linen. Burial containers were rigid mats made of plant material that sometimes had ropes attached for easier carrying from the city to the densely packed cemetery.

Most of the graves were marked with low cairns of limestone builders, some with memorial steles or gravestones. A few of the graves had small limestone pyramids. Because of erosion and looting very little remains of these surface grave markers, the paper says.

Most of the interments excavated thus far have been disturbed by grave robbers, who tended to rummage through the upper part of the body, probably looking for jewelry, but left much of the bone within the grave. It is usually still possible, nonetheless, to gain a good overall understanding of the nature of each burial, and to reconstruct the skeletons to a substantial degree.

“Grave goods, or items that might have been left beside the grave as offerings during or after burial, are rare.” The team found pottery vessels, most of them fragmentary, which they assumed were used to contain food and beverage; amulets and jewelry among the wrappings or on the body; and cosmetic items, including mirrors, kohl tubes and travertine vessels.

Some of the simple grave markers and steles at Amarna commoners’ cemetery; note the pyramidal shape of the bottom two. (Antiquity photos)Analysis of the skeletons tells a sad tale of the life of the people there. Some of the skeletons showed signs of early childhood hunger, anemia and scurvy. As far as workload injuries, the team found severe degenerative joint disease in at least one limb in nearly 60 percent of the skeletons.

Some of the simple grave markers and steles at Amarna commoners’ cemetery; note the pyramidal shape of the bottom two. (Antiquity photos)Analysis of the skeletons tells a sad tale of the life of the people there. Some of the skeletons showed signs of early childhood hunger, anemia and scurvy. As far as workload injuries, the team found severe degenerative joint disease in at least one limb in nearly 60 percent of the skeletons.“The spine also exhibited high frequencies of DJD development (56.7 per cent presence; 35.6 percent severe), with the most common severe manifestation being observed in the lumbar region,” the authors wrote. In other words, the lower back was hurt bad from the labor.

Featured image: An undisturbed skeleton of a man in the extended, supine posture typical at the cemetery; and the burial of a man with a common pattern of disturbance in which the upper torso has been jumbled by robbers and the skull removed. (Antiquity photo)

By: Mark Miller

Published on November 15, 2015 03:00

History Trivia - Battle of Winwaed - Penda of Mercia defeated

November 15, 655 - Battle of Winwaed: Penda of Mercia was defeated by Oswiu of Northumbria. Although the battle was said to be the most important between the early northern and southern divisions of the Anglo-Saxons in Britain, few details are available. Significantly, the battle marked the effective demise of Anglo-Saxon paganism.

November 15, 655 - Battle of Winwaed: Penda of Mercia was defeated by Oswiu of Northumbria. Although the battle was said to be the most important between the early northern and southern divisions of the Anglo-Saxons in Britain, few details are available. Significantly, the battle marked the effective demise of Anglo-Saxon paganism.

1515 - England's Thomas Wolsey was invested as a Cardinal.

1515 - England's Thomas Wolsey was invested as a Cardinal.

Published on November 15, 2015 01:00