Foster Dickson's Blog, page 23

September 4, 2021

Southern Movies, since 2013

Over more than a century, mainstream movies have offered portrayals of the American South that range from the darkness of 1918’s Birth of a Nation to the fluffiness of 2002’s Sweet Home Alabama. Many Americans who have never visited the South (and know little to nothing about it) take their understanding of our complicated culture not from history books by Shelby Foote or C. Vann Woodward, but from the images, characters, and story lines in popular films, like Gone with the Wind, Forrest Gump, The Help, and Fried Green Tomatoes. (Personally, I don’t know anybody who ever pooped in a chocolate pie or barbecued an abusive husband.) Whether they are set in the South, feature Southern characters, or both, movies feed and fuel how Americans view and treat the South, and also perpetuate and protect misinterpretations. Below is a list of Southern Movie posts by decade. Just click on the red titles to read the posts:

Over more than a century, mainstream movies have offered portrayals of the American South that range from the darkness of 1918’s Birth of a Nation to the fluffiness of 2002’s Sweet Home Alabama. Many Americans who have never visited the South (and know little to nothing about it) take their understanding of our complicated culture not from history books by Shelby Foote or C. Vann Woodward, but from the images, characters, and story lines in popular films, like Gone with the Wind, Forrest Gump, The Help, and Fried Green Tomatoes. (Personally, I don’t know anybody who ever pooped in a chocolate pie or barbecued an abusive husband.) Whether they are set in the South, feature Southern characters, or both, movies feed and fuel how Americans view and treat the South, and also perpetuate and protect misinterpretations. Below is a list of Southern Movie posts by decade. Just click on the red titles to read the posts:

Introduction: Ten Films about the South, from March 2013

1930sThe Green Pastures (1936) • Way Down South (1939)

1940sThe Blood of Jesus (1941) • The Southerner (1945)

Go Down, Death! (1945) • Intruder in the Dust (1949)

1950sDrums in the Deep South (1951) • Member of the Wedding (1952)

The Phenix City Story (1955) • Baby Doll (1956)

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) • The Defiant Ones (1958)

Porgy and Bess (1959) • Suddenly, Last Summer (1959)

1960sThe Children’s Hour (1961) • Gone are the Days! (1963)

Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964) • Black Like Me (1964) •

Murder in Mississippi (1965) • The Black Klansman (1966)

Cool Hand Luke (1967) • In the Heat of the Night (1967)

Slaves (1969) • The Witchmaker (1969)

1970sThe Liberation of LB Jones (1970) • tick . . . tick . . . tick . . . (1970)

The Beguiled (1971) • Preacherman (1971)

Sounder (1972) • The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972)

Moon of the Wolf (1972) • Walking Tall (1973)

White Lightning (1973) • Lemora: A Child’s Tale of the Supernatural (1973)

The Klansman (1974) • Macon County Line (1974)

Hot Summer in Barefoot County (1974) • Ode to Billy Joe (1976)

The Town that Dreaded Sundown (1976) • Eaten Alive (1976)

Smokey and the Bandit (1977) • Moonshine County Express (1977)

Greased Lightning (1977) • French Quarter (1978)

Norma Rae (1979) • Wise Blood (1979)

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1979, TV)

1980s The Sky is Gray (1980) • Southern Comfort (1981)

The Sky is Gray (1980) • Southern Comfort (1981)

Dark Night of the Scarecrow (1981, TV)

Six Pack (1982) • The Beast Within (1982)

Cross Creek (1983) • Ellie (1984)

The Color Purple (1985) • Down by Law (1986)

Angel Heart (1987) • Shy People (1987)

Long Walk Home (1988) • Steel Magnolias (1989) • Trapper County War (1989)

1990sVoodoo Dawn (1991) • Fried Green Tomatoes (1991)

Paris Trout (1991) • The Rainmaker (1997)

Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997) • The Waterboy (1998)

2000sThe St. Francisville Experiment (2000) • Radio (2003)

2001 Maniacs (2005) • Skeleton Key (2005)

Black Snake Moan (2006) • Hatchet (2007)

2010s The School in the Woods (2010) • The Dynamiter (2011)

The School in the Woods (2010) • The Dynamiter (2011)

Straw Dogs (2013) • Free State of Jones (2016)

Mud Bound (2017) • Sophie and the Rising Sun (2017)

Just Mercy (2019)

Southern Movie Bonus posts:A Spooky, Scary Southern Sampler, from October 2019

A Women’s History Month Sampler, from March 2020

Another Spooky, Scary Southern Sampler, Old School Edition, from October 2020

Another Spooky, Scary Southern Sampler, 21st century Edition, from October 2020

A Black History Month Sampler, from February 2021

August 26, 2021

Year 19 in the Classroom

Some years, about the time we start school, I write a rumination about what’s on my mind as summer ends and classes return. In the past, I’ve been thinking about funding or politics. This year, it’s life itself— life and death. I enjoy teaching and I’m thankful for it. I’m also thankful that both I and my family are generally healthy. I got vaccinated last winter, so I’ve got that going for me, too. But watching the news and seeing the situation as it stands right now, I’m reminded that every teacher doesn’t have what I have. Neither does every student.

Last month, when COVID-19 began to surge again, a vocal minority of parents began publicly opposing public health measures like masks and virtual learning. While I agree with them completely that masks are uncomfortable and that in-person learning is better, their stance is causing some teachers, staff, and even students to make life-and-death decisions about whether to come to school this year. As resistant parents say, I’m not going to do this, or You can’t make my kid do that, teachers with autoimmune problems, diabetes, or cancer are having to say: It’s quit my job or possibly/probably die. Others who have elderly relatives living with them or children with health problems are having to do the same thing, knowing that catching the virus might mean bringing it home to infect somebody they love. (This is happening among custodians, secretaries, and lunchroom workers, too.) Then, when those teachers quit, somebody has to pick up the slack. Their classes can’t just sit there without a teacher, even when no qualified person applies. Class sizes can get larger, and social distancing can become impossible.

Last month, when COVID-19 began to surge again, a vocal minority of parents began publicly opposing public health measures like masks and virtual learning. While I agree with them completely that masks are uncomfortable and that in-person learning is better, their stance is causing some teachers, staff, and even students to make life-and-death decisions about whether to come to school this year. As resistant parents say, I’m not going to do this, or You can’t make my kid do that, teachers with autoimmune problems, diabetes, or cancer are having to say: It’s quit my job or possibly/probably die. Others who have elderly relatives living with them or children with health problems are having to do the same thing, knowing that catching the virus might mean bringing it home to infect somebody they love. (This is happening among custodians, secretaries, and lunchroom workers, too.) Then, when those teachers quit, somebody has to pick up the slack. Their classes can’t just sit there without a teacher, even when no qualified person applies. Class sizes can get larger, and social distancing can become impossible.

I write all that to write this: as I begin year nineteen in the classroom, I’ve seen some things and been through some things but nothing like this. At this point, I have taught through a major national reform, a global economic collapse, years of inadequate funding, two major state-level reforms, a state takeover, our school burning down, and a global pandemic, but I’ve never seen anything as absurd as what I’m seeing right now. As a teacher who has lived with fear and anxiety during the era of school shootings, I understand why the fear and anxiety over COVID-19 is leading some teachers to quit. In Alabama, where I teach, the 2016 Students First Act says that teachers must give thirty days notice and cannot quit their jobs within thirty days of the first day of school. I feel certain that this law was conjured up out of the realization that teachers were fed up and acting on that frustration. But the circumstances this year are more dire than normal frustration.

Given what I’ve experienced and learned while teaching, I can understand a lot of things. I understand why a bunch of veteran teachers retired when No Child Left Behind said, in 2003 – 2004, that they weren’t “highly qualified” and would have to go take college classes again. I understand how, five years later in 2008 – 2009, the Great Recession led to the massive funding cuts that eliminated thousands of teaching positions. After teaching through all that, I understand why Governor Robert Bentley said, in 2016, that our schools “suck” and why enrollment in teacher training programs (education majors) had fallen by 45%. I also understand why we’ve had a teacher shortage since the late 2010s: many laid-off teachers found new careers, and the colleges weren’t churning out enough newbies. But I don’t understand this situation now.

During my career, I’ve heard people ranging from know-it-all acquaintances to governors and legislators proclaim that the humanities are worthless and should be eliminated from public schools and colleges. Studying the humanities – literature, history, sociology, etc. – gives us opportunities to grow in empathy. If you ask me, we need the lessons of the humanities more than ever, as people begin to regard each other in transactional terms where disagreements become an affront to one’s values or a violation of one’s freedom. What happened to simply caring about each other?

I dislike inconvenience and discomfort as much as the next person, but I also realize that these facts of life appear daily, even constantly. I’m inconvenienced every time I stop at a traffic light, and I experience discomfort every time I am too busy to take a bathroom break. So, if the inconvenience and discomfort of a mask and social distancing are all it takes to help other people stay alive, then I’ll do it. If putting up with some inconvenience and discomfort will keep even one person from dying or keep a child from being orphaned or rescue someone from being isolated and lonely during virtual learning, then for goodness’s sake, let’s put on our masks, space ourselves, and get to the business of teaching and learning.

August 10, 2021

The Fitzgerald Museum’s Literary Contest and Zelda Award

The Fitzgerald Museum’s annual Literary Contest for high school and college students opens its submissions period on September 1, 2021. This year’s theme for the general contest, which accepts submissions from anywhere in the world, is “The Radiant Hour.” This theme celebrates the centennial of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1921 novel The Beautiful and the Damned. Also, this is the second year for the Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald Young Writers Award, which is open to Alabama high school students. Submissions for this award are not governed by a theme, but should be comprised of a portfolio of writings.

The Fitzgerald Museum’s annual Literary Contest for high school and college students opens its submissions period on September 1, 2021. This year’s theme for the general contest, which accepts submissions from anywhere in the world, is “The Radiant Hour.” This theme celebrates the centennial of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1921 novel The Beautiful and the Damned. Also, this is the second year for the Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald Young Writers Award, which is open to Alabama high school students. Submissions for this award are not governed by a theme, but should be comprised of a portfolio of writings.

The Fitzgerald Museum’s fourth annual Literary Contest

The Radiant Hour

F. Scott and Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald were daring and revolutionary in their lives and in their art and writing. More than one hundred years after they met in Montgomery, Alabama, the Fitzgeralds’ literary and artistic works from the 1920s and 1930s are still regarded as groundbreaking, and The Fitzgerald Museum is seeking to identify and honor the daring and revolutionary young writers and artists of this generation.

Categories: Grades 9–10, Grades 11–12, Undergraduate

General Guidelines for 2021 – 2022:

The Fitzgerald Museum’s fourth annual Literary Contest is accepting submissions of short fiction, poetry, ten-minute plays, film scripts, and multi-genre works that exhibit the theme “The Radiant Hour,” which is the title of the second section of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1921 novel The Beautiful and the Damned. This theme implies works about illumination, discovery, or moments of clarity. Works with traditional forms and styles will be accepted for judging, yet writers are encouraged to send works that utilize innovative forms and techniques. Literary works may include artwork, illustrations, font variations, and other graphic elements, with the caveat that these elements should enhance the work, not simply decorate the page.

The submissions period is open from September 1 until December 31, 2021. Works will be judged within three separate age categories, not by genre, so please be clear about the age category. Submissions should not exceed ten pages (with font sizes no smaller than 11 point). Each student may only enter once. Awards will be announced by March 15, 2022. Each age category will have a single winner and possibly an honorable mention.

Works should be submitted through the web form on the Fitzgerald Museum’s website. Due to issues of compatibility, works should be submitted as PDF to ensure that they appear as the author intends. Files should be named with the author’s first initial [dot] last name [underscore] title. For example, J.Smith_InnovativeStory.pdf. Questions about the contest or the entry process may be sent to contest coordinator Foster Dickson at fitzgeraldliterarycontest@gmail.com, with “Literary Contest Question” in the subject line.

This year’s judges are Lisa Reeves for the undergraduate category and Jason McCall for the high school categories. Reeves has taught literature and composition at the University of Georgia for over twenty years. She grew up in Muscle Shoals, and attended the University of North Alabama then Auburn University. Her father taught her to read at a young age and instilled in her a lifelong love of words. McCall is an award-winning writer and poet who is a native of Montgomery, Alabama. He holds an MFA from the University of Miami and teaches at the University of North Alabama. His most recent collections are A Man Ain’t Nothin’ and What Shot Did You Ever Take (co-authored with Brian Oliu).

The Literary Contest’s annual themes honor and reflect upon the Fitzgeralds’ literary legacy. The inaugural contest had as its theme “What’s Old is New,” which encouraged students to look to tradition for inspiration. For the second year, the theme “Love + Marriage” celebrated the centennial of the couple’s courtship and marriage. In year three, “The Education of a Personage” centered on themes of growth and maturing aligned with the centennial of Scott’s debut novel This Side of Paradise. The current theme, for year four, harkens back to 1921’s The Beautiful and the Damned with the theme “The Radiant Hour.” While these themes do parallel the Fitzgerald’s literary and personal history, they are intended to guide students to consider and examine the present and the future as Scott and Zelda did in their day.

The second annual Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald Young Writers Award

(for high school students in Alabama only)

Montgomery, Alabama native Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald was daring and revolutionary in her life, art, and writing, and The Fitzgerald Museum’s Young Writers Award that bears her name seeks to identify and honor Alabama’s high school students who share her talent and spirit. Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald was inducted into the Alabama Writer’s Hall of Fame in spring 2020. This award, which was first given the following year, celebrates her life and legacy by recognizing the talents and abilities of young Alabama writers.

General Guidelines:

The Fitzgerald Museum’s inaugural Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald Young Writers Award is accepting submissions of portfolios from young writers who are currently attending high school (grades 9 – 12) in Alabama. Portfolios should contain literary works (stories, poems, plays or film scripts, multi-genre works) totaling 5 to 15 pages with font sizes no smaller than 11 point. Writers are encouraged to include works that are innovative in style, content, form, and/or technique. Literary works may include artwork, illustrations, font variations, and other graphic elements, but these elements should enhance the work, not simply decorate the page.

The submissions period is open from September 1 until December 31, 2021. Each student may only enter once.

Portfolios will be judged holistically, and only one award will be given each year. The recipient will be announced by March 15, 2022.

Portfolios should be submitted through the web form on the Fitzgerald Museum’s website. Due to issues of compatibility, works should be collected into one PDF named with the author’s first initial [dot] last name [underscore] ZeldaPortfolio (for example, J.Smith_ZeldaPortfolio.pdf). Questions about the award or the entry process may be sent to contest coordinator Foster Dickson at fitzgeraldliterarycontest@gmail.com, with “Zelda Fitzgerald Award Question” in the subject line.

This year’s judge for the award is Kerry Madden-Lunsford. She is an associate professor of Creative Writing at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the author of eight published books for children and adults. Her newest is a picture book, Ernestine’s Milky Way, published by Random House Studios in 2019 and was selected as the State Book of Alabama at the National Book Festival in Washington DC. Her book, Up Close Harper Lee, made Booklist’s Ten Top Biographies of 2009 for Youth.

July 14, 2021

The Great Watchlist Purge of 2021: A Mid-Summer Progress Report

I’m at the six month mark in this year’s Great Watchlist Purge, my year-long effort to whittle down the self-imposed cinematic to-do list to something manageable. I started in mid-January with seventy-two films on the list. By mid-April, I had watched twenty-two of them and scrapped four, but had also added fifteen more . . . Heading into the second quarter, I was ahead on the scoreboard but my opponent (a catalogue of old and odd movies) was keeping pace with me.

As spring arrived, I had just over sixty movies in the watchlist and seemed to be running low on options for finding some of them. A good number were available to rent or buy as streaming titles on Prime, YouTube, or Apple TV, a handful were available on DVD from Netflix, but others were off the map, with only the trailer or a clip showing up in searches. At first, accessing something to watch was none too difficult— but it’s getting harder.

One problem I have is that I like indie films, quirky older movies, and cult classics. And by “indie,” I don’t mean corporate-sponsored films dressed up as independents, and by cult classics, I don’t mean The Breakfast Club or Mean Girls. I mean real independent films, really obscure films, the hidden gems . . . Some among those have been very hard to find, like the 1980s African-American dystopian film Born in Flames. Yet, I’ll be honest about one of the challenges in watching these kinds of films: some are either mediocre or just plain bad. The fact is that some films disappear into obscurity for a reason, and sitting through them is . . . well, not enjoyable. But I’m either watching them or scratching them.

As for decades, my list is very 1970s-heavy, so it has been hard to stray too far from the “Purple Decade.” During the first three months, eleven of the twenty-one films I watched were from the ’70s. In the remaining list, twenty-five of the sixty films – nearly half – were made during those years. (The next most prominent decade in this list is the ’80s with thirteen films.) This time, I have watched one from the 1960s, seven from the 1970s, four from the 1980s, two from the 1990s, two from the 2000s, and one from the 2010s.

Here are the seventeen that I’ve checked off the watchlist since mid-April:

Thomasine & Bushrod (1974)

Directed by Gordon Parks, Jr. and billed as a Bonnie & Clyde story, this film is different from most blaxploitation films, which are typically urban and set in the then-modern 1970s. This one is set in out West in the 1910s. Most of the usual blaxploitation scenario is there, though, including an obscenely cheesy love scene and the violent finale.

The Tenant (1976)

I went into this film with a slight prejudice against Roman Polanski, since his only other film that I had seen was The Fearless Vampire Killers, but I was going to give it a chance anyway. The Tenant is a thriller with a strong premise – a guy moves into an apartment that was recently vacated when a young woman committed suicide – though it was slow getting started. The first half-hour was kind of dull, then it begins to become clearer why those mundane facts mattered. The latter half of the film is tormented and bizarre. I had just gotten through watching Persona when I chose to watch this next, so it was odd to watch two identity-switching movies in a row.

Abby (1974)

This movie wasn’t bad at all. It contained many of the usual blaxploitation elements – afros, mustaches, sideburns, bell bottoms, gaudy wallpaper – but this one was a horror movie instead of a crime-based story. The exorcist was played by William Marshall, who was Blacula. The lead actress Carol Speed was in a bunch of blaxploitation films, like The Mack, Dynamite Brothers, and Disco Godfather. As a horror movie, Abby‘s demon possession wasn’t as scary as The Exorcist, which came out a few years earlier, but it still creeps me out when the demon voice replaces the person’s real voice.

The Magic Garden of Stanley Sweetheart (1970)

As a movie, it was a pretty typical ’60s zeitgeist thing— hippies and nudity and art and “let’s live free,” all that. That was probably pretty cool for the young folks when it was happening, but looking at as a middle-aged man in 2021, it was like, “Yeah, OK, I get it.” I added this to the list when I read that Joe Dallesandro was originally supposed to play Stanley, but he was replaced by a young Don Johnson. Dallesandro’s scowling seriousness would have made this a totally different film than it was with Johnson’s sweet, nice-boy demeanor.

It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books (1988)

Because it was Richard Linklater, I gave this movie more latitude than I would have otherwise. I’m a fan of Slacker, which came out two years after this one and which I saw in the ’90s as a teenage GenXer. I probably would have liked this film too, had I seen it when I was younger, given that it’s basically the semi-romantic wanderings of a lone young man.

Persona (1966)

The first few minutes of the film are odd and confusing, then the next half-hour is slow and dull, but about midway, the complexity started to show through. The second half is much more interesting than the first half, and the final half-hour is downright complex. I had read that Persona is one that compels multiple viewings, and I can see why. Long before David Lynch made Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive, Bergman was doing the identity-switch thing here.

The Black Cat (1989)

This Italian horror film from the late ’80s was terrible — I mean terrible — and I like bad horror movies. The premise is that two filmmakers write a script about a forgotten goddess who then terrorizes the actress who wants to play her in that film. I had to watch an overdubbed version, which didn’t help, but there wasn’t much that could’ve helped this film. It was pretty stupid.

The Borrower (1991)

The movie begins as an alien story, then it becomes an urban action/sci-fi/police drama that centers on a super-killer criminal alien who is exiled to Earth. I think they might have been trying to make something like Terminator. We’ve got early ’90s Rae Dawn Chong, who we don’t hear much about anymore, lots of synth-pop/rock music, and some cheesy special effects. It wasn’t a bad movie, for what it was, but it certainly wasn’t great.

Fantastic Planet (1973)

This one was odd for sure . . . Animated and only about seventy minutes long, the story was a mixture of an anti-colonialist allegory and Terminator, with the whole thing overlain by ’70s porn music. Oh, and it’s in French.

Under Milk Wood (1971)

This was an odd situation. The film that I have in the watchlist is a live-action production starring Richard Burton, Liz Taylor, and Peter O’Toole, but what I got from Netflix’s DVD folks was an animated version with a voiceover by Burton. The version I watched was just under an hour runtime and had interesting animation, but it wasn’t the film I wanted.

Meridian (1990)

This horror/thriller was harder to find, since it’s now listed under alternate title Kiss of the Beast. But when it showed up on Tubi, I got to rewatch it. I was a fan of Twin Peaks and Wild at Heart in the early ’90s, and both Sherilynn Fenn and Charlie Spalding were in this. Both actresses were as beautiful as I remembered, but the film was pretty weak. I remembered it being a decent monster movie, sort of a cross between Beauty and the Beast and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde with some Vampire Circus and a twin twist. But, seeing it again thirty years later, it just wasn’t that good. Either my memory failed me or my standards have gotten higher.

Tucker and Dale vs. Evil (2010)

The Evil Dead movies set the standard for gory comedies back in the ’80s. That was carried forward by Shaun of the Dead in the early 2000s. So, it was pretty easy to see this one coming. The movie was still pretty funny and might have been a cult classic, if it was a new concept. But it wasn’t.

Paris, Texas (1984)

This was a very, very good movie. Harry Dean Stanton is such a unique actor, and Wim Wenders makes great films. I love slow-spaced indies that allow the characters to be fleshed out and real, with all of the pauses and silences and mundane moments that come with real life. This movie also made me feel like David Lynch had watched it several times before making Wild at Heart. I’m just sorry that I waited so long to watch it.

Factotum (2005)

My image of Charles Bukowski in film will always be Mickey Rourke’s portrayal in Barfly. Here, almost two decades after that movie, Matt Dillon does a good job with Bukowski. He’s got his mannerisms, and the film captures that vignette quality that Bukowski’s books have— this was a good movie. I think the problem here is that the writer’s time has passed. Younger people don’t seem to care about underground counterculture and also get easily offended, both of which would turn someone off to Charles Bukowski.

The Unnamable (1988)

I remembered seeing this movie jacket in the video rental store when I was younger, but it was never interesting enough to rent. I watched it and had the feeling that I’d seen it before, but could be wrong. It’s a classically 1980s horror film: set on a college campus, good looking co-eds, and a gratuitous sex scene, with characters being picked off one-by-one and a final half-hour that is one long violent foray. Not terribly impressive but feathered hair and the often-repeated scenario brought back memories.

Wendy and Lucy (2008)

This movie is very stark. Unfortunately, when I watched it, I wasn’t in the mood for blunt realism, but that’s what I got. Wendy and Lucy is solid portrayal of what happens to people with little cash and few resources who are just trying to get by. The main character gets caught up in a string of unfortunate situations, and it’s hard to watch her struggle.

Hi, Mom! (1970)

Before I started watching Hi, Mom! I thought it looked like a hippie mess. I was right. Brian de Palma made some great movies later – Scarface, The Untouchables, and Carlito’s Way – as did Robert DeNiro of course, but the two young guys were still working out the kinks at this point. It was a lot of rambling dialogue and barely strung together plot.

Lilith’s Awakening (2016)

I added this movie to the list since I typically like these slow-paced films that are categorized as “arthouse/horror,” and I also have an affinity for black-and-white when it’s handle well, like in The Addiction. This one definitely met those expectations, but it also seemed kind of homemade, like it was a film school project. The names were based on Dracula – Harker, Helsing, Renfield – but I didn’t see where there was much connection, since this vampire wandered out of the woods with an acoustic guitar. It also included an identity-switching component, like two other films I watched recently: Persona and The Tenant.

And here are the nine movies that I’ve cut since April. Last time, it was early in the process, so I only cut four. This time, I got more liberal in admitting what I’m probably not going to find or not going to watch.

Greetings (1968)

After watching Hi, Mom! I decided to cut Greetings from the watchlist.

Mountain Cry (2015)

I searched for this movie but couldn’t find any way to watch it. It’s Chinese, and the reviews say that it’s beautifully filmed. Mountain Cry came up in a search of the term “haiku,” so I’m not going to spend any more time trying to find a movie that I don’t really know anything about.

The Vampires of Poverty (1978) and La mansion du Araucaima (1986)

I haven’t been able to find any way to watch these two by director Carlos Mayolo. Films out of Colombia in the late ’70s are a bit out of my wheelhouse anyway, but both look intriguing. Vampires of Poverty is fictional but made to look a documentary about the poor. The latter is about an actress who wanders off a film set and into a weird castle. In both cases, I would need both to find the movie and find ones with subtitles. Maybe one day I’ll run across them.

Mondo Candido (1975)

I read the novel Candide in graduate school and liked it, and I teach it sometimes in my twelfth grade English class. It’s a pretty wild story and could make a good movie. But this adaptation is Italian, and I’ll need subtitles.

Endless Poetry (2016)

Alejandro Jodorowsky is hit-or-miss for me. I liked The Holy Mountain and Santa Sangre but I didn’t finish El Topo. This movie about him is supposed to be done in his very strange style. I cut this one since I could tell that I wasn’t all that interested in watching more Jodorowsky.

Beginner’s Luck (2001) and Tykho Moon (1996)

I had to give up on these two movies, because I don’t believe I can find a way to watch either one. Amazon Prime says that Beginner’s Luck is available on Prime, but I get the message that it is “currently unavailable to watch in your location.” Tykho Moon is a European film based on a Japanese comic book, and I can’t seem to find even a foreign-language version to watch. I hadn’t really been interested in either film, but was mainly interested in Julia Delpy who I’ve liked since seeing Killing Zoe and Before Sunrise in the ’90s.

The Night They Robbed Big Bertha’s (1975)

I wasn’t able to find a way to watch this movie, but on YouTube, there were clips and also reviewers who shared a bit about it. After watching those, I decided that this movie looked so stupid that I was better off not wasting my time on it. My decision was aided by the fact that it has 2.5 stars (out of 10) on IMDb.

There are now twenty-seven films remaining from the original January list, which contained seventy-two. A handful of these are in my Netflix DVD cue, some are available to rent or buy on at least one streaming service, and a few seem pretty elusive.

Ravagers (1979)

Though I don’t know much about this movie, it sounds odd, but what caught my attention was that it was filmed in Alabama.

Francesco (2002)

This movie caught my attention, because I am interested in Saint Francis.

Don’t Look Now (1973)

This movie came up as a suggestion after I rated the movie Deep Red. I like suspenseful movies and I like ’70s movies and I like Donald Sutherland, so I put it in the list.

The Panic in Needle Park (1971) and Dusty and Sweets McGee (1971)

These are from the early ’70s and are about hardcore drug users. I’m not sure that I’ll ever watch either of them, but I have them in the list in case I decide to.

In Bruges (2008)

I found this Colin Farrell action story about a hitman, when I was reading something that said it was a great film, and then also came across Bruges Le-Morte in a search when I typed ‘Bruges’ in the search bar to find the first movie.

Haiku Tunnel (2001)

This movie (and Mountain Cry) came up when I searched the term ‘haiku.’ It is an early 2000s indie comedy about doing temp work in an office. I remember it being one of the last GenX zeitgeist films, but coming out a bit too late.

The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1929)

I had never heard of this animated movie before seeing a reference to it on Twitter from an account that was disputing Fantasia‘s designation as the first full-length animated feature film. The clip attached to the tweet was interesting, and I want to see the whole film.

The River Rat (1984)

I found this film when I was trying to figure out what Martha Plimpton had been in. I tend to think of Plimpton as the nerdy friend she played in Goonies, but this one, which is set in Louisiana and has Tommy Lee Jones playing her dad, puts her in a different role.

The Mephisto Waltz (1971)

I’ve read about this movie but never seen it. I must say, the title is great, and it doesn’t hurt that Jacqueline Bisset is beautiful.

Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971)

This horror film came up alongside Deep Red, which I watched not long ago, after I rated two recent horror films: the disturbing Hagazussa and the less-heavy but still creepy Make-Out with Violence. Deep Red was good, so I want to watch this one, too.

Born in Flames (1983)

This movie looks cool but obscure. It’s an early ’80s dystopian film about life after a massive revolution. But it is almost impossible to find, so I was surprised to see a story on NPR about it recently.

Personal Problems (1980)

This one is also pretty obscure – complicated African-American lives in the early ’80s – and came up as a suggestion since I liked Ganja and Hess. The description says “partly improvised,” which means that the characters probably ramble a bit.

My Beautiful Laundrette (1985)

A young Daniel Day Lewis as the boyfriend of a Pakistani guy in England who opens a laundromat. This sounds like one of those quirky ’80s gems that you had to stumble on to know about.

American Splendor (2003)

Paul Giamatti back when he was still an indie film guy, before Sideways. I never did take the time to watch this movie, but I want to.

What the Peeper Saw (1972)

This Italian suspense-horror film is one from the creepy child sub-genre, like The Bad Seed.

A Tree. A Rock. A Cloud (2017)

I love Carson McCullers. That is all.

Smokey and the Outlaw Women (1978)

Even though this movie looks stupid and low budget, it also looks like a great example of mid- to late 1970s Southern kitsch, that goofy comedy sub-genre that spawned Smokey and the Bandit and The Dukes of Hazzard. I had this in the original list with The Night They Robbed Big Bertha’s, which I cut because it looked irredeemably bad.

Pierrot le Fou (1965)

Jean-Luc Godard in the ’60s. I wanted to see this after watching Contempt, with Brigitte Bardot, which was a beautiful and heartbreaking movie. The title means Pierre (or Peter) the madman.

The Devil Rides Out (1968)

Though I like old horror movies, I’m normally not a Christopher Lee fan. This movie is supposed to be better than most of his churned-out vampire movies. We’ll see . . .

Little Fauss and Big Halsey (1970)

Paul Newman movies from the late ’60s and early ’70s are among my all-time favorites. This one came out about the same time as Sometimes A Great Notion. Despite having seen Cool Hand Luke, Hud, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and Long, Hot Summer numerous times each, I’d never heard of this movie until a few years ago.

Widespread Panic: Live from the Georgia Theatre (1991) and The Earth Will Swallow You (2002)

How has a guy who loves Widespread Panic never seen either of these early concert films? Ridiculous.

All the Right Noises (1970)

I found this story about a married theater manager who has an affair with a younger woman, when I looked up what movies Olivia Hussey had been in other than Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet. It looks a little like Fatal Attraction, like the relationships goes well until it doesn’t.

The Girl Behind the White Picket Fence (2013)

I found this movie in a search for Udo Kier, who I’ve liked since seeing Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein and Dracula when I was in high school. The cinematic style of this one looks pretty cool, as does the story.

House (1977)

I noticed this film since it’s classified as horror, but what interests me more is the visual style of it. I’ve gotten to see clips from House and want to see the whole thing.

All the Colors of the Dark (1972)

I saw this movie in the mid-1980s when the USA Network used to have a program called Saturday Nightmares, which featured an obscure horror movie followed by two half-hour shows like Ray Bradbury Theater or The Twilight Zone. That weird old program turned me on 1960s and ’70s European horror movies, like this is one, Vampire Circus, and The Devil’s Nightmare. I haven’t seen this movie in a long time, but it’s time to rewatch it.

That was the original January list. These the nine films were added between January and April and are still in the list.

Deadlock (1970)

This Western came up as a suggestion at the same time as Zachariah. It’s a German Western, so we’ll see . . .

The Blood of a Poet (1930)

Jean Cocteau’s bohemian classic. I remember reading about this film in books that discussed Paris in the early twentieth century, but I never made any effort to watch it. I’m not as interested in European bohemians as I once was, but if the film is good, it won’t matter.

Landscape in the Mist (1988)

This Greek film about two orphans won high praise. I haven’t tried to find a subtitled version yet, it may be out of reach.

Phantom of the Paradise(1974)

I can’t tell what to make of this movie: Phantom of the Opera but with rock n roll in the mid-’70s?

Alone in the Dark (1982)

A good ol’ 1980s horror movie about escapees from an insane asylum. It should be terrible! I can’t wait!

The Hunger (1983)

I’d seen this movie before but thought I’d watch it again— a vampire movie with David Bowie, Catherine Deneuve (from Belle Du Jour), and Susan Sarandon (from Rocky Horror Picture Show).

Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (1971)

As I’ve already shared, I just like ’70s horror movies. We’ll see if this one is any good.

White Star (1983)

This biopic has Dennis Hopper playing Westbrook. I couldn’t not add it to the list!

The Spider Labyrinth (1988)

One of the reviewers under mentioned this Italian horror/thriller in his review of another movie. He had high praise for it. Once again, we’ll see what happens.

And finally, here are the ones I’ve added since April. I did better this time! During the first three months of the year, I added fifteen movies to watchlist. This time, only six. I went ahead and watched three, which are listed above. Believe it or not, all but one of the additions come not from the 1970s— but from the twenty-first century!

The Strange Color of Your Body’s Tears (2013)

This French thriller, which came up as a suggestion from All the Colors of the Dark, caught my eye with its the wonderful artwork on it cover image. The title is also compelling, and those two factors led me see what it was. It didn’t hurt that the description contained the phrase “surreal kaleidoscope.”

Frances Ferguson (2019)

This dark comedy looks really funny. It’s about a young female teacher who has gotten in trouble for having sex with a student, so it’s probably something that I (a teacher) shouldn’t find funny. But it looks like a good movie, so . . . whatever.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014)

This film came to my attention on one of the movie-related accounts that I follow on Twitter. Once I looked on IMDb to see what it is, the first “You Might Also Like” was Let the Right One In, which is a beautifully made vampire movie. Like Lillith’s Awakening, this film is also in black-and-white.

July 6, 2021

‘tidbits, fragments, and ephemera’ from “level:deepsouth”

“tidbits, fragments, and ephemera” is a usually weekly but not always, sometimes substantial but not making any promises glimpse at some information and news related to Generation X in the Deep South. To read: visit the editor’s blog, or subscribe to level:deepsouth to receive new posts in your email.

“tidbits, fragments, and ephemera” is a usually weekly but not always, sometimes substantial but not making any promises glimpse at some information and news related to Generation X in the Deep South. To read: visit the editor’s blog, or subscribe to level:deepsouth to receive new posts in your email.

June 24, 2021

On Instagram: Life and Education

A while back, I started writing down some of the things that I’ve caught myself saying to students over the years. These brief, pithy ideas that pop into my head sometimes seem to become useful in a variety of situations. I collected that list on a webpage here, titled Life and Education, but have recently started posting them as graphics on Instagram, too. You can follow there, if you want to, and catch them as they come down the line.

June 15, 2021

The Third Batch of New Works on “Nobody’s Home”

Earlier today, I published the third batch of new works in Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore. This batch has twelve works that comes from all over the South and range in subject matter from disco to potato salad and from hoodoo to the prom. To browse (and hopefully read) these new works and the ones published earlier this year, visit the project’s Index page.

Created in 2020, Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore is an online anthology of creative nonfiction works about beliefs, myths, and narratives in Southern culture over the last fifty years, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The publication is collecting personal essays, memoirs, short articles, opinion pieces, and contemplative works about the ideas, experiences, and assumptions that have shaped life below the old Mason-Dixon Line since 1970. The project has had four reading periods for submissions during 2020 and 2021. The deadlines for the first three reading periods passed on December 15, February 15, and May 15, respectively. Accepted works were then published in January, March, and June. The current (fourth and final) reading period lasts from May 16 until August 15.

Created in 2020, Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore is an online anthology of creative nonfiction works about beliefs, myths, and narratives in Southern culture over the last fifty years, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The publication is collecting personal essays, memoirs, short articles, opinion pieces, and contemplative works about the ideas, experiences, and assumptions that have shaped life below the old Mason-Dixon Line since 1970. The project has had four reading periods for submissions during 2020 and 2021. The deadlines for the first three reading periods passed on December 15, February 15, and May 15, respectively. Accepted works were then published in January, March, and June. The current (fourth and final) reading period lasts from May 16 until August 15.

To learn more about the project, you can read my introduction, “Myths are the truths we live by.” Or you can take a look at the guidelines for submissions, read the works that have been published so far, read posts on the editor’s blog, like the project’s Facebook page, or follow on Twitter.

Access to Nobody’s Home is and will be free, and while the project is intended for a general readership, it will also have accompanying resources for teachers to use the works in their classrooms.

June 3, 2021

Watching: “Sustenance” (2020)

The Canadian documentary Sustenance, released in 2020, centers on a small group of friends who agree to have their eating habits examined to determine whether they’re making sustainable choices. In the beginning, we only meet three of those friends, among them the filmmaker Yasi Gerami, but three more appear later. By taking a look at their food choices for one meal, Gerami delves deeper into what it takes to bring those foods to their plates.

Ultimately, Sustenance presented some of what I expected, but also things that I didn’t. I was surprised to learn how vegans’ eating habits can be damaging and unhealthy. I had assumed that the highly disciplined herbivores were making the best choices. Yet, according to this film, we’re a meat-eating species, so we’ve got to figure that out.

Though I’m not a scientist, farmer, or nutritionist, I’ve been interested in these questions for some time now: How can ordinary people truly live, eat, work, etc. in sustainable ways? Those of us who are so inclined can go about doing what the people in the film do – buy organic, choose veggies, eat less meat – but this treatment shows that those barely inconvenient acts may not be enough. And in Sustenance, the focus is not on the evils of agri-business – though it is mentioned – but on how individuals and small farmers can do things differently, and on how some choices are beyond our control. People constantly have innumerable choices to make, and we have to rely on producers, marketers, and corporations to give us the information involved in making those choices. The problem is two-fold: locally grown food isn’t super-abundant, and the big-time producers focus on the information that helps them make money. So, most of us are stuck, and sustainable living, working, and eating become inordinately difficult.

The experience that drew my interest to these issues happened about ten years ago, when I learned that going all the way self-sufficient/sustainable isn’t really possible for the Average Joe. In 2010, I interviewed a couple who operate a CSA, and one of them told me emphatically that most people can’t raise and grow enough food to sustain their families. It takes land, time, energy, equipment, and knowledge that most people don’t have, and even if they did, they’d have to earn some cash for property taxes, fuel, and other needs. This couple had inherited the land, equipment, and knowledge and were sharing with others, since most people have to buy their food. In today’s economy, very few people can avoid the larger food distribution system.

I watch documentaries like Sustenance not because I believe that they’ll have all the answers, but because I know they contain some information that aligns with what I’d like to know: how to live sustainably. I have a grassroots mindset about most things, and I believe that sustainability will be achieved when ordinary people are on board, whether that’s done governmentally through mandates and public policy or naturally through everyday changes in habits that cause unhealthy foods to go unpurchased. If spending an hour or so on a documentary pushes me one step closer to something better, I’d say that’s an hour well-spent.

May 27, 2021

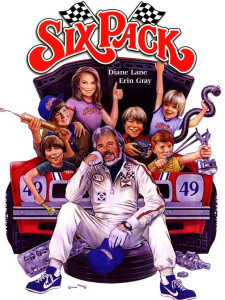

Southern Movie 55: “Six Pack” (1982)

I loved Kenny Rogers when I was a kid. He had the cool feathered hair and the swept-back beard. He was The Gambler. He sang in his signature style about things I was too young to understand. And in 1982, when I was eight, he was the dirt-track racer Brewster Baker in Six Pack. Directed by Daniel Petrie, who also directed 1974’s Buster & Billie, this film is a good-hearted tale about doing the right things the right way and taking care of the people who take care of you.

Six Pack opens with an aerial view on a rural two-lane road. Kenny’s hit “Love Will Turn You Around” plays, and at first, we’re not sure exactly what we’re looking for. Then the camera hones in on a small camper towing a trailer with a stock car and extra tires. We understand right away that this is a one-man racing operation, a guy doing his best with what he has. Soon, we begin to see a few houses and the camper van rolls into a small community where our main character will stop for gas. But before he does, we see a ratty blue delivery truck pull out from a side street and begin to follow him.

At the small gas station in Brassell, Texas, Brewster Baker gets out and stretches. He is gray-haired and bearded, dressed completely in denim, and has his shirt unbuttoned down his chest— a real ordinary guy, an ’80s Everyman. (We’ll see later that that’s only partially true.) He walks up to the station where the elderly attendant is sleeping soundly. Brewster wants to use “the john” and gets the key for himself to go around back.

As he does, that faded delivery truck pulls into the gas station too, lining itself up between the station and Brewster’s car, blocking the view. Meanwhile, Brewster has no idea that this is happening while he struggles first with the paper towel dispenser then with door knob. He is locked in . . . and has to go out the small window that ventilates the rough, added-on bathroom. Of course, he tries to hang on to the roofing but it breaks and he falls into a pile of old tires.

That’s when Brewster Baker discovers the hard truth: his car has been stripped. From the short distance away, he sees that the tires on the car and on the rack are gone, and when he jogs closer, he sees that what was under the hood is gone, too. The racer is unusually calm when he walks over to the sheriff’s office, which has a handwritten sign on the door that reads, “Out. Back in???”

All Brewster can do then is go across the street to the café and order a bowl of chili. A cutesy waitress with a radio for a belt buckle tries to flirt with him, but Brewster is too down in the dumps. Meanwhile, a young couple in a yellow Corvette pull up and come into the diner for a couple of burgers to go. The waitress makes a few sexual overtures, but he’s more interested in his car parts. Then, suddenly, she cuts him off with a terse, “I’ve got to get back to work,” and we see out the window that the blue delivery truck has done it again! The yellow Corvette, parked right by Brewster’s rig, has been stripped, too.

For the next few minutes, we watch a bluegrass-fueled rural car chase that starts on the two-lane and moves to the dirt roads. As the two large, bumbling vehicles make sharp turns and trade paint, there are some near crashes. Brewster loses his trailer on one sharp turn, and they make the requisite trip through a barnyard. That continues until the blue truck sails off of an abandoned bridge and into the river below.

Brewster arrives a moment later and sees a small crowd of children swimming away from the floating truck. “Those are kids,” he mutters to himself before he runs down the steep embankment to help them. However, one small child is left on top to the truck, scared and calling for help. The teenage girl among the kids (Diane Lane) shouts that Little Harry is still out there, and Brewster jumps in fully clothed to go after him. He puts the boy on his back and swims him to the shore.

On the river bank, the sopping wet band of juvenile delinquents helps Brewster and the little boy out of the water, and the child asks the exhausted Brewster if he’s going to die. Another boy with a surly expression then says, “Mister, you look like shee-yut,” but shakes his hand anyway for saving his brother. Then, Brewster realizes that the truck is sinking with his parts in it! But one of the boys tells him that his parts have already been delivered . . . Delivered to who? The kids aren’t saying anymore. So, Brewster gathers them up and proclaims that he’s taking them to their parents to get some answers. On their way up the hill, he also laments his broken trailer, but another boy stops him and snaps back, “If we can’t fix it, it ain’t broke, mister.”

Back up on the road, the half-dozen kids hammer the trailer’s connection back into shape and get Brewster hooked back up. The oldest of them is the teenager Heather/Breezy, and her five younger brothers are Doc the mechanic (Anthony Michael Hall, who’ll later star in Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club), Louis the big boy, Steven the squirrelly “accountant,” Little Harry, and Swifty with the foul mouth. The tone has gotten friendlier, but Brewster still isn’t happy about being robbed, so he loads the kids in the camper to take them home.

Back up on the road, the half-dozen kids hammer the trailer’s connection back into shape and get Brewster hooked back up. The oldest of them is the teenager Heather/Breezy, and her five younger brothers are Doc the mechanic (Anthony Michael Hall, who’ll later star in Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club), Louis the big boy, Steven the squirrelly “accountant,” Little Harry, and Swifty with the foul mouth. The tone has gotten friendlier, but Brewster still isn’t happy about being robbed, so he loads the kids in the camper to take them home.

What Brewster wants to find at their house isn’t exactly what he gets. At their dilapidated, tin-roof shack there are no parents, and he threatens to press charges for the theft and put them all in the reformatory. Little Harry pipes up, “I don’t want to go to the deform-a-story!” and flies into Breezy’s arms. Swifty and Louis echo the sentiment, but just then a car pulls up and they panic. It’s Big John. Breezy tells Brewster to stay put.

Outside in the yard, Big John the sheriff (Barry Corbin) immediately berates the kids for stealing a car, instead of just stripping it. He see Brewster’s rig outside, but doesn’t know Brewster is there and can hear him. Cautiously, though, he steps out of the house and confronts the grinning sheriff. The dummy deputy Otis then steps behind Brewster and says, “Let me waste him, Sheriff,” but is told to shut up. However, Brewster won’t get off so easy. He is cuffed and taken to jail for running out on his tab back at the café, but not before being knocked in the head with the gun butt for “resisting arrest.”

Brewster wakes up in the two-bit jail when the deputy Otis lets out a triumphant hoot during his game of solitaire. Soon, Swifty appears in the window and sneaks inside while Otis is preoccupied. He pulls Otis’s own gun on him and demands to have Brewster released. The spineless and not-too-bright Otis is hesitant but complies. Brewster punches him in the stomach before locking him in his own cell. But before they can get out of the building, Big John strolls up! They wait for him to pass by then sneak out, finding that Breezy is waiting in Brewster’s camper to aid in the escape. It appears for a moment that Big John and Otis might catch them, but in the brief chase that ensues, the lawman’s car comes to pieces. The pint-sized mechanics have rigged it to have the hood and other parts fly off.

In the light of day, the motley crew is making their way down a two-lane highway when Little Harry has to go to the bathroom. Brewster uses the opportunity to check his car, and one kid asks if he’s a racecar driver. “I used to be,” Brewster replies. The family then begins to speculate as to why he quit: a wreck, alcoholism, a woman . . . but Brewster doesn’t abide them. But he does ask how they became car thieves. Everyone gets quiet, but Breezy breaks the silence. Their parents were killed in a wreck, so they started stripping cars to support themselves. Big John caught them though, and he threatened to break up their family if they didn’t start working for him.

In the camper van again, Breezy asks where Brewster is going. Shreveport. Brewster wants to drop them off at the next town, but they plead to go on further with him. Those local lawmen will just call Big John. Alright, Brewster agrees, but Shreveport is it. Then they’ll go their separate ways.

In the motel parking lot in Shreveport, there are racecars all over the place. Brewster comes out of his camper dressed for the bar, and the six kids stare at him with sad expressions. He implores them to do what they agreed to in the car: spend the night in the motel, then take a bus for anywhere in the morning. He has been waiting two years to get back into racing, and he doesn’t need any distractions. As Brewster walks away, Little Harry asks, “What’re we gonna do now?” At this point, not quite a half-hour into the movie, we’re so disappointed in Brewster— how could he do this, just walk away?

Inside the honkytonk, Brewster enters to Merle Haggard’s “Rainbow Stew” and scans the room. He finds what he’s looking for pretty quickly: a slim brunette working at the bar. He makes several attempts to get noticed, which all fail, so finally, he walks over. Unfortunately, Brewster gets an elbow when he tries to kiss her neck from behind, then gives up on subtlety and lays one on her. This is Lilah (Erin Gray, who GenXers will recognize as the love interest Kate in the TV show Silver Spoons), who owns the place. They try to talk for a minute about how Brewster disappeared several years ago. However, Brewster is obviously well-known and well-liked. People keeping speaking to him and calling him over, so he’s not just an Everyman. With friendly resolve, he has to take Lilah in the corner, make out with her for a moment, and then go be with his pals.

Outside, the six miscreants are starting a dumpster fire to divert attention from the fact that they’re stripping cars. We’ll find out shortly that they’re doing it to give Brewster back the parts he lost, but Brewster doesn’t like it at all. First, it’s wrong to steal from the other drivers. Second, if they find out their stolen parts are on his car, he’ll be the one to suffer.

But before that, Brewster and Lilah excuse themselves from the barroom crowd to go back to her small apartment. There, Brewster excuses himself of responsibility for the kids, and Lilah tries to be a supportive woman. He says, “Do I look a father to you?” Lilah replies, “Yes, because you look like everything to me.” Sweet. And then they get lovey dovey.

In the morning, there is a knock at the door. Many of the drivers’ cars have been stripped, and Brewster knows – but doesn’t say – who did it. He goes back to his camper, where the six kids are waiting on him, to scold them for what they’ve done. They were just trying to pay him back for his missing parts, but Brewster isn’t hearing it. He orders the kids out of his camper, but Heather/Breezy asks him to them to the interstate at least.

On the road, they make a stop at a junkyard so Brewster can get some parts to replace what was stolen from his friends. He calls on the black junkman, who is obviously an old friend, and they have brief conversation about how long since they’re seen each other. The junkman alludes to a wreck, and now we know what happened to Brewster. But out by the roadside, the camper van is gone! Brewster has taken the ignition wire off, so they couldn’t drive away, but they managed to do it anyway. So, Brewster has to hitch rides to the track, including a semi-comical ride in the back of truck with an affectionate bloodhound.

When Brewster does arrive at the track, the Six Pack is waiting on him. A few drivers jeer at his pint-sized pit crew, but the car is ready to go. He’s mad but there’s no time to waste, since it’s his turn to qualify. And wouldn’t you know— he qualifies on the first try! The youngsters have done an excellent job getting the car ready to race.

After the race, Brewster is ready once again to ditch the half-dozen hangers-on. He gives them some money and tells them it would have been more if he hadn’t had to pay people back for the stolen parts. Lilah wanders up about that time, and Brewster introduces her to the crew. They all give him some crap about trying to ditch the kids, so he buys them some ice cream and says farewell. Swifty cusses him out as he loads up, then rips into a torrent of swears as Brewster drives off.

At the next dirt track, we meet our other villain Terk Logan, who pulls up in a shiny rig then gets out to sign autographs. He’s dressed in black, with a Richard Petty style cowboy hat. Meanwhile, Brewster is making is qualifying run, but the car doesn’t sound good. He rolls off the track and gets under the car himself. After another driver jibes him about his sputtering machine, Brewster is mumbling that he can’t fix it just as Doc dangles his stethoscope down onto Brewster’s face. The kids are back . . . Breezy tells him, with a knitted brow, “We got no choice but to stick with you ’til a better thing turns up.” Brewster agrees but reluctantly, saying this main condition is that they don’t mess any other drivers’ cars. They’ve got a deal.

About that time, Terk wanders up, chuckling and insinuating. It is clear that Brewster and Terk don’t like each other, and Terk remarks that Brewster was his “old boss.” He insults Brewster in a backhanded way a few times, and Swifty dog-cusses him while Brewster gives him the cool stare. Nothing will happen, though. Terk wanders off again, leaving behind one last threat to Brewster to watch his back, but Brewster tosses him a half-eaten apple and tells him, “Shove it.”

The kids want to know who that guy is, and Brewster tells the story. Terk was his mechanic but wanted to drive, so he sabotaged Brewster and talked smack about him to the sponsors. His monkeying around with the car caused Brewster to crash at Talladega and lose his sponsors— who picked up Terk right away. Brewster’s ultimatum is to stay away from Terk.

But Brewster has another problem, too: as he’s walking away after telling his story, Doc tells him that he has a cracked head. “That’s $2,000,” Brewster replies, saying they’ll have to make it through tomorrow’s race with what they’ve got.

So, now we’ve got a major automotive problem and two villains: Big John the sheriff and Terk the racecar driver. Brewster is a down-and-out, nearly broke, one-man show, but he’s got a good woman who believes in him and six little orphans who can fix his car up right. He’s the underdog of underdogs, and we love it!

In the motel that night, Brewster tells the kids a scary story then Breezy sends them off the bed. On the way out of his room, Breezy asks if he’s talked to Lilah lately. We get a little sense that this teenage girl is thinking of being romantic with this older man, but Brewster keeps his cool and she leaves. Brewster then heads out to the honkytonk where yet another waitress comes onto him. Once again, he’s the good guy and turns her down.

While he’s out and about, Breezy and the boys enact a plan to get new heads for Brewster’s car . . . by doing exactly what Brewster said not to. Terk is working late and all alone under his car when Breezy shows up in tight jeans and a tight red shirt. She lures him out from under the car, and he takes her back to his camper, which gives the boys time to get the parts they need for Brewster. We think for a moment that Breezy might have to get nasty with Terk, but she makes a break for it at the last second, leaving him grabbing at air and rolling around on the floor. Terk is a sleaze, so we don’t feel bad for him.

When the tired young’uns ambled back up the motel stairs, Brewster is waiting on them. They were supposed to be in bed. They try to lie about where they’ve been, and Brewster yells at Breezy, so she leaves, walking off into the night. Good guy that he is, Brewster spends the whole night riding the streets of Biloxi, Mississippi looking for her. He finds her at dawn. She refuses to go with him at first, but then breaks down and falls into his arms. In the van on the way back to the motel, she tearfully confides that she just wants to be normal. Breezy wishes she could go to high school and be cheerleader.

Out on the track, Brewster is running a good race and moves from a ninth-place start to challenge Terk for third. Near the end, they trade paint, then Terk’s car blows a head gasket. Over in the pit area, Terk knows what has happened, and when the race is over, he charges Brewster and starts a fight! The kids all jump in to help Brewster, but security breaks it up.

On the highway later, Brewster clarifies what was done. Breezy (aka Bobby Lee with the tight red shirt) seduced Terk while the boys switched his good heads for Brewster’s cracked ones. Brewster pulls the van over and tells them they can’t do that! The kids look baffled – we hate Terk, right? – but Brewster only wants to win fair and square. He also scolds Breezy for doing dangerous things, and he finally tells Swifty to watch his mouth. Brewster then decides on Nashville as their next destination, and the kids break into a stirring a capella version of “Rocky Top.”

After brief scene at a campground that has the kids looking at ads for houses for sale, the classic ’80s montage begins. The music plays as Brewster is winning races all over the South. In the background, we see a mysterious stranger who is watching all the while. Thing are looking up for our underdogs.

Or maybe not. As the last race in the montage ends with a Brewster Baker win, he gets out of the car to accept his trophy but the kids aren’t there. A man from the track tells him that a sheriff came and took them as runaways. Brewster is panicked, but as he is jogging toward his camper, he is stopped by the mysterious stranger. His name is Pinson, and he has a Ford car looking for a driver to race in the Grand National at Atlanta. This is Brewster’s big break, but he takes the man’s card and drives away. The kids come first.

In a comical interlude, Brewster goes into the Birmingham sheriff’s office and pretends to be Big John, wearing a modified Boy Scout uniform. But it works and he and the kids leave right as Big John arrives for his “chargees.” The driver and the Six Pack have a good laugh in the van, but they’re in even bigger trouble now. No matter, they’re heading for Atlanta.

At the speedway, Brewster is humbled and thankful for the new car, which has somehow been made ready almost immediately. With about twenty minutes left in the movie, it’s time for the big finish— but not without another montage! This time, Brewster is in a gray sweat suit, working out like he’s Rocky . . .well, not quite like Rocky, but he is doing sit-ups and jogging up the raceway’s stairs.

Once “training” is over, it’s time to race. Brewster qualifies to run seventh, but Terk is right behind him, starting eighth. The bad news is: the Six Pack can’t be in the pits. There’s an age limit, and they don’t make the cut. But they’ll still be able to take jobs to help out.

That evening, at the motel, the kids are counting their money to try to buy one of the houses they were looking at at the campground. They’ve got a $7,100, a lot for them but not much for house-buying, and besides, the person on the phone says they have to be adults to buy. Even worse, somebody already bought it!

Meanwhile, Brewster is at the honkytonk, where yet another waitress throws herself at him. But this time, Lilah walks in right as it’s happening. He’s busted but tries to explain, I was just trying to call you . . . She doesn’t buy it but does anyway, and they’re on good terms again.

In the morning after Brewster gets out of bed with Lilah, the real problems begin. Terk and his goons attack Brewster in a parking lot. He puts up a pretty good fight, but they get the best of him, knock him out, and dump him in the woods. At the racetrack, the crew and the sponsors are wondering whether Brewster got cold feet and ran off. But he’s not that kind of guy. Sore head and all, he hitches a ride with a couple of stoners in a convertible Volkswagen beetle. He doesn’t arrive ’til the very last minute and has to climb in the car where it has been lined up to get started.

Now, all of the conflicts come down on Brewster Baker at once. The big race, the Atlanta 500, is starting. Terk is in the race. And then, during the action, just as Brewster and Terk have moved into the first and second spots . . . Big John shows up to take the kids, personally. As Brewster comes into the pit and sees the kids’ faces in the back window of the sheriff’s car, Brewster has no choice but to go after Big John and get them. In a daft move, he runs Terk into the pit wall, ensuring that he can’t win the race, then leaves the pit and blocks Big John’s way out. In front of news cameras, Brewster exposes Big John’s corruption, leaving him no choice but to give the kids with Brewster.

Six Pack ends with Brewster and Lilah getting married, with the kids surrounding them. Then, we get to see what really happened with the house. Someone did buy it. It was Brewster! Now, they’re one, big happy family living in their dream home.

Six Pack is a feel-good movie, plain and simple. Rotten Tomatoes gives it a mediocre 71%, and Turner Classic Movies doesn’t give it any more than bare-bones, almost-empty webpage. Back in 1982, The New York Times called the film “good-natured but none-too-interesting” then added this cynical assessment: it’s “the kind of film in which orphans find a father, a lonely man finds a good woman, an unsuccessful racer makes good on the comeback trail, and everybody lives unreasonably happily ever after.” Yup, that describes it.

More recently, the website Saving Country Music had this to say about the movie in a March 2020 review:

You won’t find the 1982 film Six Pack archived in the Smithsonian or in the short list of Oscar-awarded efforts. But for thousands, maybe millions of Americans who grew up in the 80’s, Six Pack looms quite large in their little cultural ethos. [ . . . ] In many ways Six Pack was a kids movie, even though a lot of the themes and dialogue were definitely oriented towards adults. It was one of those “wink wink” movies before the PG-13 rating was implemented where producers purposely included pieces of forbidden fruit to make younger and older audiences interested at the same time.

I’d say that writer nailed it, too. My fondness for Six Pack doesn’t come from any notions of cinematic excellence. It comes from my recollections of growing up white and blue-collar in the Deep South in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. Movies like this and Smokey and the Bandit and the show Dukes of Hazzard gave my friends and I a sense that being a Southerner at that time was cool. Of course, we didn’t know anybody who actually raced or who actually ran from the cops, but our dads and uncles were the guys you see in the background, in the stands watching the race and in the bars drinking.

Watching the movie almost forty years later, though, one thing does bother me: there are almost no black people. Here, we’ve got this movie, set in the Deep South, where a guy starts in east Texas, then goes to Shreveport, Biloxi, Birmingham, Atlanta . . . and the only black people we see are the junkyard man near the beginning and one of the two stoners near the end. There were millions of African Americans living in those places at that time, but there aren’t even black people in the background, among the extras! That says something about the making of the movie . . . It would take work – real work – to ensure that only white people made it onto the screen. That’s not even getting to having the only black characters be a good-natured junk man and a stoned hippie.

May 16, 2021

Fourth (and Final) Reading Period for “Nobody’s Home”

Today begins the final reading period for Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore. This last one will end on August 15, with works accepted during that time being published in September 2021.

Today begins the final reading period for Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore. This last one will end on August 15, with works accepted during that time being published in September 2021.

The first three reading periods have passed, and this will be the last opportunity for writers to submit work for possible inclusion in the anthology. The first two batches of works in the anthology were published in January and March, and the accepted works from the third reading are coming in June. Right now, the accepted works from first two reading periods can be accessed on the project’s Index page. Works that are accepted from the third reading period will appear in that Index later.