Foster Dickson's Blog, page 25

February 9, 2021

Southern Movie Bonus: A Black History Month Sampler

In February, we take time to celebrate and recognize the contributions and achievements of African Americans. So, in honor of Black History Month, the Southern movies listed below are either about African Americans in the South or come from African-American culture in the South. From more recent years, moviegoers may be familiar with 2012’s The Help or 2013’s Selma, but here are six Southern movies that may be less familiar to modern audiences.

Green Pastures (1936)Made at the height of the Great Depression, this primitive film features African-American folk religion versions of well-known Biblical narratives. Based on a story that was first a novel then a play, the movie stars Rex Ingram. Reports say that Green Pastures was immensely popular in its day and that its sales were through-the-roof.

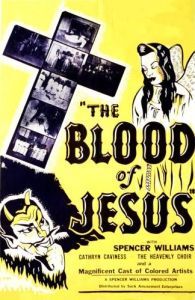

Go Down, Death! (1945)One of black director Spencer Williams’ “race films” from the 1940s, Go Down, Death! is another film with religious overtones, similar to his previous The Blood of Jesus from 1941. Both films were made in Texas, and illustrate the evils of the world and how the goodness of God stands in opposition to it. Though Williams doesn’t star in either film, he does act in both.

Porgy and Bess (1959)This legendary musical, made by Otto Preminger, features Dorothy Dandridge, Sidney Poitier, and Sammy Davis, Jr.. Set in Charleston, South Carolina in 1912, the story centers on woman named Bess whose relationship with Crown and with the drug dealer Sportin’ Life take a turn when Crown kills a man. She seeks refuge with the disabled Porgy— until Crown comes back.

Gone are the Days! (1963)This Civil Rights-era film, which stars Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, is based on the Broadway play Purlie Victorious. Set in Georgia, the story centers on a man who returns to the Georgia plantation where he was raised. However, he wants the plantation owner to think that his fiancee is really his cousin. The movie also stars Godfrey Cambridge, who was in both Purlie Victorious and Jean Genet’s The Blacks on Broadway.

text

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sing (1979)Based on Maya Angelou’s 1969 autobiography, this 1979 made-for-TV movie stars Diahann Caroll and Ruby Dee. Viewers familiar with Angelou’s book will know that she hails from Arkansas and that she was raped as a girl by her mother’s boyfriend. The young actress Constance Good plays Maya; other recognizable actors are Paul Benjamin and Ester Rolle. This screen adaptation is not well-known but is regarded by some as an underrated classic.

The Sky is Gray (1980)Based on an Ernest J. Gaines short story, this movie was also made for TV and is only forty-six minutes long. The story is set in early 1940s Louisiana and features a boy who has an unyielding toothache, which forces his mother to take him to town to the dentist. At their home on a farm, we see the extent of their poverty, made worse by the husband/father being drafted into the army. In town, we see the tense situation they have to navigate to ride the bus, see the dentist, use the bathroom, and eat lunch. Cleavon Little makes a brief appearance, but his character is not part of the main storyline.

February 2, 2021

Southern Movie 53: “The Blood of Jesus” (1941)

Low-budget and stark, 1941’s The Blood of Jesus was one of several “race” films from African-American filmmaker Spencer Williams. In the early 1940s, films by and about black people were sparse, and Williams was one of a few black directors making them. Set in the rural South, the story here centers on free will and redemption, as a woman’s near-death experience leads her to a choice between Heaven and Hell.

The Blood of Jesus, which is heavy on hymn-singing and other performances, starts on a baptism scene as the credits roll. We then see a rural dirt road, a country church, a man plowing with a mule, and two men singing under a tree as a voiceover narrates. Once the set up is done, the story kicks in as we watch a procession of a couple-dozen black people walking down a dirt road and singing hymns. Flanking the preacher are two large women in the front.

Soon, they arrive at a break in the grass and reeds, where they can get to the river, and we see our main character Martha get baptized. As she is getting dipped in the river by the preacher and his helper, the larger of those two large women Sister Ellerby remarks that she can’t believe that Razz Jackson has gone off hunting while his wife is getting baptized. “They’ve only been married three months,” she says. The other large woman Sister Jenkins agrees, but excuses herself to give the newly baptized Martha a robe to help her dry off. Once that serious part is done, we get a little comic relief when the next man to get baptized claims to see a snake in the river, giving him his reason to run away down the dirt road.

Then, we meet Razz Jackson, who is coming home with his rifle and a full croaker sack. He is a pudgy man, a little hard to take seriously, and he sits down on the porch after hanging his sack on a nail. As he collects himself on the porch, Sister Jenkins comes out of his house and begins a conversation about what might be in the sack. He tells her that he didn’t get much and not to mess with it. Razz is clearly concerned that Sister Jenkins will want one (or more) of the rabbits that he’s bagged and makes moves to keep her away from his take.

Meanwhile, his wife Martha is inside on the bed, resting as Sister Jenkins has suggested. We find out that the Jacksons are very poor and that the rabbits in the sack are all they have to eat. The scene moves away from Martha for a moment, as we listen again to the two Sisters gossip, but then we get back to the Jackson house quickly.

Martha calls out to the porch, “Razz, why don’t you pray and try to get religion?”

He replies, “Okay, honey, I’ll try,” in a lackluster manner.

Martha senses that he has no intention of trying. She then moves across the small bedroom and begins to ponder over a small portrait of Jesus. The image is stereotypically American: Jesus is white with light-colored hair, and he has a bright heart on his chest. Certainly, Martha cannot fathom what is about to happen.

Nearby, Razz is done with whatever it is that he’s doing, and he leans his guns against a chair. But it falls and goes off! The blast hits Martha, and she falls to the floor. Razz goes to her, finding that he has inadvertently shot his wife, though it is hard to tell whether his concern is for her or for himself.

Word must have traveled fast, and the main characters in the church crowd are in the Jackson house. Martha is lying in bed, probably dying, muttering some prayers to herself, and seeing visions of angels in Heaven. The church folks are singing around her. Razz hangs back with his face in his hand, maybe concerned, maybe just pouting.

Then Martha dies. Sister Jenkins leads a prayer for her soul and for Razz as well. At first, Razz looks annoyed, but as they sing “Old Time Religion,” he has a breakthrough. Razz looks up, puts his hands together, and begins to pray.

The movie is about one-third of the way through now – twenty minutes into the hour-long runtime – and Razz is left alone with his dead wife. He doesn’t know it, of course, but she is about to make her journey.

With the good people all gone, Razz is there praying, and an angel comes out of the wall to look after Martha. The angel is played by an attractive young black woman with long hair. She take Martha’s soul out of the house and to a nearby graveyard, where spirits in white robes wander around aimlessly. Martha wants to know who they are and what they’re doing. The angel tells her that they’re here caught between this world and the next.

With the good people all gone, Razz is there praying, and an angel comes out of the wall to look after Martha. The angel is played by an attractive young black woman with long hair. She take Martha’s soul out of the house and to a nearby graveyard, where spirits in white robes wander around aimlessly. Martha wants to know who they are and what they’re doing. The angel tells her that they’re here caught between this world and the next.

But that isn’t Martha’s fate. The angel takes her to a dirt road and explains that, by turning one way, she will encounter sin and Hell, which is the city, and the other way, she will find redemption and Heaven. Just then, the Devil comes out from behind and tree. He is wily and grinning, excited to lure this soul away from goodness. He brings out a young man in a fine suit and tells him, “Do your stuff,” then laughs loudly as he sets his plan in motion.

At this point, we understand the movie to be an allegory. Martha has entered a dream narrative, outside of her mundane experience. Martha is the Everyman character, and this well-dressed young man is the embodiment of temptation. As she ponders her course, the man appears out of nowhere with a nice new dress and new shoes to match. He tells her she doesn’t have to pay for them, they’re free. For a woman who has been married to a ne’er-do-well, living on the brink of starvation, this must seem pretty good.

And she falls for it. She puts on the dress and shoes and goes with him to the 400 Club. They sit at a table in the crowded club where people are drinking and listening to jazz. Martha is loving it. After a moment, though, the suave young conman goes over to a friend of his, says some things we don’t hear, then brings his friend over to meet Martha. We will find out in a moment that the friend is a pimp who runs a dance hall. Simpleton that she is, Martha is lured by the fun and the promises of making plenty of money with very little work.

Next we see Martha, after the performance-heavy club scene followed by a few minutes of watching people in the dance hall, she is in an upstairs room by herself, clearly upset over the decisions she has made. The pimp comes in to tell her to get to work, but she wants out. He says no and demands again that she work off the money and nice things he has given her. Instead, Martha goes out the back way and runs.

But it won’t be that easy. As she leaves, men from the club – we recognize them as the fast-and-easy crowd – chase her. Somehow, Martha outruns them across fields and down dirt roads, even though she’s in an ankle length dress and high heels.

Eventually, the chase brings her to crossroads, where the Devil himself has a flatbed truck with a band playing. Around the truck and the band are people drinking and having a good time. Nearby is a large signpost that directs travelers one of two ways: left to Hell and right to Zion. Martha goes to the signpost and makes the choice to go right, but the Devil is there to stop her. He throws Martha on the ground and laughs maniacally. She is terrified. But then the saving grace of God comes to her rescue, as the signpost become the cross of Christ and a booming voice admonishes the Devil to leave Martha alone. He does, jumping in the flatbed truck, driving off with the band, and leaving the sinners without their pleasures. After the Devil is gone, the men who were chasing Martha arrive, and when one of them raises a stone to hit her with, the booming voice admonishes them, “Let him without sin cast the first stone.” Knowing they’re outmatched, they run away. The scene culminates in Martha being saved, as she lays at the foot of the cross and blood of Jesus drips onto her face.

Coming out of the dream narrative, Martha wakes up in her bed and has overcome the threat of death. Razz is thrilled that she is alive, and out of nowhere, the church folks reappear and begin to sing the praises. As the film ends, Martha and Razz stare lovingly at each other as the angel hovers over them.

The Blood of Jesus would probably be disappointing to twenty-first century moviegoers who are accustomed to polished productions. The acting is bad, the costumes and sets are cheap, and the website Rotten Tomatoes only gives the film 1.5 stars out of 5. But viewing it in terms of longstanding models of storytelling, it works. The Blood of Jesus was called a “masterpiece of folk cinema” by The Village Voice, and Time magazine put on its Top 25 Important Movies on Race.

A film like this one, which was thought to be lost at one point, has to be looked at in context. At a time when pre-Civil Rights African-Americans had almost no rights, almost no opportunities, and almost no wealth, Spencer Williams was making films for them that featured and celebrated their own culture, their own songs, and their own religion. At this point, it seems less appropriate to evaluate the production quality and more important to give credit to Williams, his cast, and crew for accomplishing a lot with a little.

As a document of and about the South, The Blood of Jesus presents what was not presented in mainstream films made by white directors. Spencer Williams was a veteran of Amos N Andy, and must have known and understood the stereotypes. Taking the reins himself, he had greater (though certainly not total) freedom to portray African-American life in his own way. That’s what makes films like The Blood of Jesus valuable.

January 28, 2021

Reading: “Still Life with Oysters and Lemon”

Still Life with Oysters and Lemon by Mark Doty

My rating: 5 out of 5 stars

This is where being open to suggestions works out well. It was 2008, and I was told by my friend Nancy Grisham Anderson that Mark Doty had been offered the Weil Fellowship at Auburn University at Montgomery, my alma mater. I was familiar with Doty as an extraordinary poet from his inclusion in anthologies and other projects, and was excited that he was coming to give a public lecture in Montgomery. Nancy told me that he would be talking about his book Still Life with Oysters and Lemon. Though it had been published in 2002, I’d never heard of it.

Though I had to fly through Still Life with Oysters and Lemon right before Doty was coming to speak, I’ve read and re-read it multiple times in the twelve years since. At less than 80 pages, it doesn’t take long, though I don’t want to be misunderstood to mean that the book is easy or simple. It is short. It’s also complex, packed with meaning, and really beautiful. The book functions like a long essay that weaves among subjects, prime among them still life painting.

More so, Still Life with Oysters and Lemon is about intimacy, an idea that Doty comes back to several times. Using the idea that a still life captures a moment through temporal objects, he carries the reader through a somewhat stream-of-consciousness narrative that includes his grandmother’s peppermints, his deceased partner Wally, his purchase of fixer-upper home with a new lover, his birthday, and of course, his ideas on poetry. What I like about Still Life with Oysters and Lemon is that it seems like Mark Doty is just talking to me about what’s on his mind.

This time, I was re-reading it because I’ve decided to teach it in the spring. In this time of virtual learning, which is off the beaten path, I’ve been looking for works that are off the beaten path and that emphasize out common humanity. I had considered this one and Annie Dillard’s For the Time Being, but opted for this book since it’s shorter and I want the students to (actually) read it. For my part, there are only a few works that I have read over and over because they’re keenly and adeptly insightful, distinct in their awareness of our predicament, our nuances, our trifles, our struggles, and because they speak to me. Still Life with Oysters and Lemon is one of those books. I hope that that is recommendation enough. The only other things I can say: I’m glad that Mark Doty wrote it and equally glad that Nancy turned me on to it.

January 14, 2021

The Great Watchlist Purge of 2021

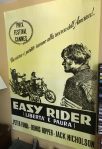

Watching movies, particularly independent films and old classics, is one of my longtime hobbies. Among my favorites have been 1982’s Beastmaster and 1970’s Rio Lobo when I was kid, then 1986’s At Close Range and 1983’s Suburbia when I was a teenager. I’ve always had eclectic taste. Easy Rider is my all-time favorite movie, but I also can’t deny that I like more traditional films. Christmas can’t go by without It’s a Wonderful Life, and my heart breaks every time I see Joe Bradley walk away at the end of Roman Holiday. My favorite Charlie Brown special is Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown (and Don’t Come Back!). I first started watching blaxploitation films in the late 1980s when a buddy got a hold of VHS tapes of Dolemite and The Human Tornado. I like weird and trips stuff like Peter Greenaway’s The Pillow Book and Prospero’s Books, and I like stark realism like Twelve Angry Men, and I like quirky comedies like One Crazy Summer and Better Off Dead. I. Just. Love. Movies.

Watching movies, particularly independent films and old classics, is one of my longtime hobbies. Among my favorites have been 1982’s Beastmaster and 1970’s Rio Lobo when I was kid, then 1986’s At Close Range and 1983’s Suburbia when I was a teenager. I’ve always had eclectic taste. Easy Rider is my all-time favorite movie, but I also can’t deny that I like more traditional films. Christmas can’t go by without It’s a Wonderful Life, and my heart breaks every time I see Joe Bradley walk away at the end of Roman Holiday. My favorite Charlie Brown special is Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown (and Don’t Come Back!). I first started watching blaxploitation films in the late 1980s when a buddy got a hold of VHS tapes of Dolemite and The Human Tornado. I like weird and trips stuff like Peter Greenaway’s The Pillow Book and Prospero’s Books, and I like stark realism like Twelve Angry Men, and I like quirky comedies like One Crazy Summer and Better Off Dead. I. Just. Love. Movies.

In that spirit, I used some of my abundant free time during the COVID-19 quarantine to make an attempt at watching more movies in my IMDb Watchlist— the Great Watchlist Purge of 2020, I called it. I began in March with 67 films in the list, I watched all of the movies I could find, searching Prime and Netflix and YouTube and other video sites on the web . . . and then I ended the year with 74 films in the list! I would watch a movie, go and rate it, and voila!— if you liked that, here are some other movies you might like. It’s neverending!

Below is the current watchlist, in no particular order. I’m going to try again in 2021 to whittle this self-imposed cinematic to-do list down to something manageable, posting my progress on Twitter with the hashtag #GreatWatchlistPurge.

Persona (1966)

Ingmar Bergman in the mid-’60s. I’ve read that this film is very complex and has to be watched multiple times to understand it. Sounds like my kind of movie.

Ravagers (1979)

Though I don’t know much about this movie, it sounds odd, but what caught my attention was that it was filmed in Alabama.

Francesco (2002) and Francesco (1989)

The newer of these two movies caught my attention, because I am interested in Saint Francis. The older one came in the suggestions list and stars Mickey Rourke right after he starred in 9 1/2 Weeks and Angel Heart. I am having trouble imagining how some casting agent saw Rourke in those two films and thought, “That’s our saint . . .”

Don’t Look Now (1973)

This movie came up as a suggestion after I rated the movie Deep Red. I like suspenseful movies and I like ’70s movies and I like Donald Sutherland, so I put it in the list.

Born to Win (1971), The Panic in Needle Park (1971), and Dusty and Sweets McGee (1971)

These three are all from the early ’70s and are all about hardcore drug users. I’m not sure that I’ll ever watch any of them, but I have them in the list in case I decide to.

In Bruges (2008) and Bruges-Le-Morte (1978)

In Bruges (2008) and Bruges-Le-Morte (1978)

These two films have nothing to do with each other, except that they both have the Belgian city Bruges in the title. I found the former, a Colin Farrell action story about a hitman, when I was reading something that said it was a great film, and the latter came up in a search when I typed ‘Bruges’ in the search bar to find the first movie. The second one is older and is about a guy who becomes obsessed with a woman who looks like his dead wife.

The Blonde and the Black Pussycat (1969)

I came across this movie when searching for the actress Edwige Fenech, who starred in All the Colors of the Dark, which is down this list a ways. It’s about two aristocrats who inherit the same castle and fight over it. I’m not sure how Fenech fits in, but we’ll see.

Haiku Tunnel (2001) and Mountain Cry (2015)

These movies have no relation to each other either, except that they both came up when I searched the term ‘haiku.’ The first movie is an early 2000s indie comedy about doing temp work in an office, and the second one is a beautifully filmed Chinese drama about a family in a small village.

The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1929)

I had never heard of this animated movie before seeing a reference to it on Twitter from an account that was disputing Fantasia‘s designation as the first full-length animated feature film. The clip attached to the tweet was beautiful, and I want to see the whole film.

The Black Cat (1989)

An Italian horror film from the late ’80s . . . eh, why not?

The River Rat (1984)

I found this film when I was trying to figure out what Martha Plimpton had been in. I tend to think of Plimpton as the nerdy friend she played in Goonies, but this one, which is set in Louisiana and has Tommy Lee Jones playing her dad, puts her in a different role.

So, Is the Man Who is Tall Happy? (2013)

I’d just like to see this documentary on Noam Chomsky because he always has interesting ideas, even if I don’t agree with them.

The Mephisto Waltz (1971)

I’ve read about this movie but never seen it. I must say, the title is great.

Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971)

This horror film came up alongside Deep Red, which I watched not long ago, after I rated two recent horror films: the disturbing Hagazussa and the less-heavy but still creepy Make-Out with Violence. Deep Red was good, so I want to watch this one, too.

Born in Flames (1983)

This movie looks cool but obscure. It’s an early ’80s dystopian film about life after a massive revolution.

Personal Problems (1980)

This one is also pretty obscure – complicated African-American lives in the early ’80s – and came up as a suggestion since I liked Ganja and Hess. The description says “partly improvised,” which means that the characters probably ramble a good bit.

The Vampires of Poverty (1978) and La mansion du Araucaima (1986)

Two by director Carlos Mayolo. Films out of Colombia in the late ’70s are a bit out of my wheelhouse, but both look intriguing. Vampires of Poverty is fictional but made to look a documentary about the poor. The latter is about an actress who wanders off a film set and into a weird castle. In both cases, I’ll need subtitles.

My Beautiful Laundrette (1985)

A young Daniel Day Lewis as the boyfriend of a Pakistani guy in England who opens a laundromat. This sounds like one of those quirky ’80s gems that you had to stumble on to know about.

Greetings (1968) and Hi, Mom! (1970)

These two Brian de Palma movies both star a young Robert DeNiro and look like a hippie mess. But I’d like to see them.

The Borrower (1991)

Early ’90s sci-fi/horror, starring Rae Dawn Chong, who you don’t hear much about anymore. She was everywhere for a while then kind of disappeared. The plot description sounds like a body snatchers kind of thing.

Quiet Days in Clichy (1970)

Quiet Days in Clichy (1970)

Having been a big Henry Miller fan in college, I had already seen Henry & June and the adaptation of Tropic of Cancer that stars Rip Torn. The book Quiet Days in Clichy is about Miller’s (supposed) wild adventures with his friends, so I’ll be curious to see what the filmmaker did with that.

American Splendor (2003)

Paul Giamatti back when he was still an indie film guy, before Sideways. I never did take the time to watch this movie, but I want to.

What the Peeper Saw (1972)

This Italian suspense-horror film is one from the creepy child sub-genre, like The Bad Seed.

Alabama (1985)

The title of this one lured me in. But it’s not about Alabama, the state where I live. The film is Polish and has no description on IMDb. One of the posters says “love story” on it, so I’m guessing that it’s a love story. I’m mainly curious why it’s titled Alabama.

A Tree. A Rock. A Cloud (2017)

I love Carson McCullers. That is all.

The Night They Robbed Big Bertha’s (1975) and Smokey and the Outlaw Women (1978)

Both of these movies look awful, but they also look like great examples of that mid- to late 1970s Southern kitsch, that goofy comedy sub-genre that spawned Smokey and the Bandit and The Dukes of Hazzard.

Mondo Candido (1975)

I read the novel Candide in graduate school and liked it, and I teach it every once in a while in my twelfth grade English class. It’s a pretty wild story, and this adaptation is Italian. However, it’s hard to find and I’ll need subtitles.

Fantastic Planet (1973)

An animated sci-fi film, which isn’t really my thing, but the stills on IMDb make it look like something to see.

Pierrot le Fou (1965)

Jean-Luc Godard in the ’60s. I wanted to see this after watching Contempt, with Brigitte Bardot, which was a beautiful and heartbreaking movie.The titled means Pierre (or Peter) the madman.

The Devil Rides Out (1968)

Though I like old horror movies, I’m normally not a Christopher Lee fan. This movie is supposed to be better than most of his churned-out vampire movies. We’ll see . . .

The Wicker Man (1973)

I’ve read that this is one of the best horror films ever made.

Little Fauss and Big Halsey (1970)

Paul Newman movies from the late ’60s and early ’70s are among my all-time favorites. This one came out about the same time as Sometimes A Great Notion. Despite having seen Cool Hand Luke, Hud, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and Long, Hot Summer numerous times each, I’d never heard of this movie until a few years ago.

The Baby (1973)

I noticed this horror movie several years ago after watching an older black-and-white movie called Spider Baby, which was really bizarre. This one is about a man-sized “baby” and looks equally weird.

Under Milkwood (1971)

Richard Burton and Liz Taylor after Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which I loved, and a story written by the poet Dylan Thomas.

Heavy Traffic (1973)

Again, I’m not really a cartoon guy, but this is Ralph Bakshi, who did Heavy Metal in the early ’80s. When we were growing up Heavy Metal was a major no-no, and we never could understand why— we’re kids and it’s a cartoon, what’s the problem? I watch it as an adult and saw why kids shouldn’t watch it. This is another one of his, but hard to find.

Six Pack (1982)

This was one of my favorites as a kid. Kenny Rogers, in his heyday, played a struggling race car driver, then he was helped by a pit crew of orphans who he finds when they try to rob him. It also has Diane Lane around the time she was in The Outsiders. But this movie is difficult to find these days.

The Sky is Gray (1980)

This movie is an adaptation of an Ernest Gaines short story. I haven’t been in a big hurry to watch it though, since the 1983 adaption of A Gathering of Old Men was poorly done, even though it had a good cast.

Widespread Panic: Live from the Georgia Theatre (1991) and The Earth Will Swallow You (2002)

How has a guy who loves Widespread Panic never seen either of these early concert films? Ridiculous.

Mondo Cane (1962)

I started this documentary once, left off, and never went back to it. The general thing is that it shows strange and sometimes violent rituals, traditions, and practices around the world. There’s a distinctly colonialist feel to it, like saying “Look what savages these people are,” but it also has the same feel as the Faces of Death series that were available when I was young. I don’t know that I’ll ever go back to watching this, but I leave it in the list.

All the Right Noises (1970)

A story about a married theater manager who has an affair with a younger woman, and it looks a little like Fatal Attraction, like the relationships goes well until it doesn’t. I keep some movies in the watchlist because they look weird or unique. This one might actually be good.

The Effects of Gamma Rays on Man in the Moon Marigolds (1970)

I like this play a lot and teach it in my Creative Writing classes. Beyond that, Paul Newman, one of my favorite actors, produced this adaptation. I’m curious to see what a filmmaker would do with this very emotional story.

Boxcar Bertha (1972)

Boxcar Bertha looks a bit like Bonnie and Clyde. An early ’70s crime movie set during the Depression, it was directed by Martin Scorsese. It should be good.

The Sex Life of Belgians (1994) and Camping Cosmos (1996)

The Sex Life of Belgians was heavily advertised in the mid-’90s when I subscribed to the Village Voice. But living in Alabama in a time before streaming services, I had no access to the film. This is a director I know nothing about. The second film is the sequel.

Meridian (1990)

This horror/thriller was not a great movie, but it has Sherilynn Fenn in it, and she was another one of my 1990s celebrity crushes from being in Wild at Heart and Twin Peaks. For some reason, this movie has become hard to find.

Tucker and Dale vs. Evil (2010)

I can’t remember who told me I ought to watch this, but somebody I know did. The genre is listed as comedy/horror and you never can tell with movies like that. The title inclines me to think it could be like the Evil Dead movies

The Girl Behind the White Picket Fence (2013)

I found this movie in a search for Udo Kier, who I’ve liked since seeing Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein and Dracula when I was in high school. The cinematic style of this one looks pretty cool, as does the story.

Endless Poetry (2016)

Alejandro Jodorowsky is hit-or-miss for me. I liked The Holy Mountain and Santa Sangre but I didn’t finish El Topo. This movie about him is supposed to be done in his very strange style.

Pink Motel (1982)

By all accounts, reviews, etc. this movie is terrible. But it has a few things going for it: it was made in the early ’80s, and it stars Phyllis Diller and Slim Pickens.

Macunaima (1969)

I started watching this once, and it was really freakin’ weird. It’s surreal, Brazilian, and anti-colonialist, and I may give it another try.

The Rebel Rousers (1970), Ride in the Whirlwind (1968), and Psych Out (1968)

In the late ’60s, Jack Nicholson was prolific, though not all the films were great ones. Since Easy Rider is my favorite movie of all-time ever, I’ve got a special place in my heart for Nicholson and for hippie biker films, even bad ones.

Mood Indigo (2013)

This just looked like a good movie. And I’ve like Audrey Tautou ever since I saw Amelie.

Paris, Texas (1984) and Lucky (2017)

Part of me is embarrassed, as a movie buff, that I’ve never seen Paris, Texas, but another part of me says, “Hey, I was ten when it came out.” I like Harry Dean Stanton. He was the dad in Pretty in Pink, he was in David Lynch’s Wild At Heart, and he was hilarious in Two-Lane Blacktop as a hitchhiker who tries to pay Warren Oates for the ride with a blowjob. Both of these films star Stanton. The former is said to be one of the best films ever made.

Big Sur (2013)

Jack Kerouac was the writer who made me want to be a writer. This film is an adaptation of his book, but I’ve put off watching it for the same reason that I won’t watch Francis Ford Coppola’s adaptation of On the Road— I want my experience with the book to be the interpretation/imagining of it that stays in my head. I may not ever watch this movie.

Factotum (2005)

In addition to liking Henry Miller in college, I also like Charles Bukowski. I’ve seen Barfly many times but have never seen this bio-pic that has Matt Dillon as Bukowski.

House (1977)

I noticed this film since it’s classified as horror, but what interests me more is the visual style of it. I’ve gotten to see clips from House and want to see the whole thing.

The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1971)

Another Edwige Fenech movie that looks similar to All the Colors of the Dark below.

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Minnesota (2017)

I missed this movie in the theaters. I want to see it.

Beginner’s Luck (2001) and Tykho Moon (1996)

Both of these movies star Julia Delpy, who was another 1990s celebrity crush after I saw Killing Zoe and Before Sunrise.

All the Colors of the Dark (1972)

I saw this movie in the mid-1980s when the USA Network used to have a program called Saturday Nightmares, which featured an obscure horror movie followed by two half-hour shows like Ray Bradbury Theater or The Twilight Zone. That weird old program turned me on 1960s and ’70s European horror movies, like this is one, Vampire Circus, and The Devil’s Nightmare. I haven’t seen this movie in a long time, but it’s time to rewatch it.

Belladonna of Sadness (1973)

Like House above, this Japanese film is visually really interesting. I’ve read that it was the progenitor for the anime genre. I don’t care about anime personally, but I’ve seen parts of this film and what I’ve seen is pretty trippy.

How Tasty Was my Little Frenchman (1971)

Like Macunaima, I also started watching this Brazilian anti-colonialist film once and never went back to it. Maybe this year, I’ll finish it. Then again, maybe I’ll just accept that I don’t like surreal, Brazilian, anti-colonialist films.

January 7, 2021

What’s in Store for 2021?

Sketches of Newtown will go to press in mid-January. This 92-page monograph comes from an Alabama Bicentennial Commission-funded student project. The book contains ten short student-written, student-edited sketches (essays) about aspects of Newtown and its history, a selected bibliography, a color photo insert, and summaries of the oral histories collected in February 2019. A delivery date in mid- to late February is expected. Copies will be given away at no charge; however, requests will be limited to one book per person.

Also in January, the first works will be published in the new online anthology Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore. The first reading period for submissions lasted from October 1 through December 15. Submitting writers received their responses during the last week of December.

Also in January, the first works will be published in the new online anthology Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore. The first reading period for submissions lasted from October 1 through December 15. Submitting writers received their responses during the last week of December.

level:deepsouth will continue to accept submissions about growing up Generation X in the Deep South in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s.

Right before the spring equinox, on March 15, the winners of the Fitzgerald Museum’s third annual Literary Contest will be announced. This year’s theme has been “The Education of a Personage,” which comes from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1921 debut novel This Side of Paradise. This year’s judges are Ashley M. Jones and Alina Stefanescu.

Then, in Spring

In March, the second batch of works will be published in Nobody’s Home, and the third reading period will begin. May 15 will mark the end of that third reading period.

March will also mark the one-year anniversary for level:deepsouth, which will continue to accept submissions about growing up Generation X in the Deep South in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s.

Later, in Summer

In June, the third batch of works will be published in Nobody’s Home. At that point, the final reading period will have begun, and it will last until August 15.

In July, Foster will deliver the first draft of his book-length manuscript about Montgomery Catholic Preparatory School, formerly St. Mary’s of Loretto School. The project, which got underway in 2019, will commemorate the school’s 150th anniversary in 2023 with a summative account of its history. No release date has been set, as that anniversary is still two years away.

In August, the theme for the Fitzgerald Museum’s fourth annual Literary Contest will be announced. This student contest accepts submission from September 1 until December 31 each year.

Finally, in early August, Foster will begin his 19th year in the classroom when the 2021 – 2022 school year opens— hopefully in-person!

Finally, in Fall

In September, the fourth and final batch of works will be published in the Nobody’s Home. At that point, the Literary Arts Fellowship will end, as the next round of fellows begin their projects in October. Once the anthology is complete, the project will enter a new phase that will consist of sharing and promoting the works.

January 5, 2021

A Deep Southern, Diversified & Re-Imagined Recap of 2020

I had big plans for 2020. Plans for my school garden, plans for my students, plans for new projects of my own. But COVID-19 had other plans. After going to the Camp McDowell Farm School last November then the Alabama Sustainable Agriculture Network’s Food & Farm Forum last December, I was ready to use that new knowledge to improve the school garden. After receiving another education grant from the Alabama Bicentennial Commission, I was ready to continue with my students in Newtown. After deciding to get off my keister and finally develop the Southern Generation-X project I had thought about for a long time, I was ready to get started. Then a couple-zillion microbes came along and changed everything. But COVID didn’t stop the work entirely – except in the school garden, which did have to stop – though the ideas had to undergo some amendments. Below is a selection of posts from the blog that tell a reasonably solid version of this year’s story. Click on any of the red links to read further.

Posts

Recycling, Money, Sustainability, and Me (February)

A new project . . . level:deepsouth— for Generation X (March)

Congratulations to the Winners of “Love + Marriage” (March)

A Look Back at “Patchwork: A Chronicle of Alabama in the New South” (April)

Literary Arts Fellowship from the Alabama State Council on the Arts! (June)

Biographical Sketches of Women Suffragists (June)

Alabamiana: Revisiting Mr. Rice (July)

The Education of a Personage: The Fitzgerald Museum Literary Contest (August)

Call for Submissions for Nobody’s Home (October)

Sketches of Newtown (December)

16,425 Days: The Whitehurst Case (December)

Let’s learn the lesson and move on. (December)

Reading

A Letter Concerning Toleration by John Locke (January)

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (January)

The Seven Storey Mountain by Thomas Merton (February)

Let the Dead Bury their Dead by Randall Kenan (April)

How to Write a Sentence by Stanley Fish (April)

Whose Votes Count? by Abigail Thernstrom (May)

The Death of Innocents by Sister Helen Prejean (May)

A Love Letter to the Earth by Thich Nhat Hanh (May)

Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson (August)

St. Mark’s is Dead by Ada Calhoun (September)

Black Elks Speaks as told to Jim Neihardt (September)

Woodrow’s Trumpet by Tim McLaurin (September)

and published in “Groundwork,” the editor’s blog for Nobody’s Home :

Judgment & Grace in Dixie by Charles Reagan Wilson

The Countercultural South by Jack Temple Kirby

Southern Movies

Macon County Line (1974)

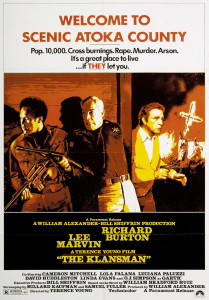

The Klansman (1974)

The Beguiled (1971)

Good Intentions (2010)

The Rainmaker (1997)

The Liberation of LB Jones (1970)

Murder in Mississippi (1965)

Suddenly, Last Summer (1959)

Bonus: A Women’s History Month Sampler

Bonus: A “Welcome to Eclectic” Southern Documentary Sampler

Bonus: Another Spooky, Scary Sampler, Old School Edition

Bonus: Yet Another Spooky, Scary Sampler, 21st Century Edition

December 29, 2020

Let’s learn the lesson and move on.

Everything won’t be magically better on Friday, but I think that we all agree that 2020 has been a whopper. Some of it we knew was coming, like Donald Trump’s antics when he lost the election, and some of it was less certain, like the enormity of the pandemic. Many people won’t be sad to see 2020 in the rearview mirror – except for maybe online retailers and billionaires – but among the wreckage, this teacher sees one lesson that we can learn.

For me, the bad part started when students were sent home last March. COVID-19 came to the US, and schoolhouses were closed soon after the first cases were acknowledged. What we call “school” went virtual. But schools weren’t prepared for that, and teachers weren’t trained for it. I was luckier than most in that I had taught online courses before, but the experience didn’t make me want to do it again. What we’ve experienced in 2020 with the lack of student engagement and the psychological distance between the teacher and students— I felt that when I taught online creative writing courses in 2007 and 2008. I knew about the problems that were coming.

In my main teaching gig, I can truly say that I like the energy in an American high school. I’ve taught mostly twelfth graders for the last decade, and I especially enjoy their energy in the spring as graduation approaches. Last spring, though, prom was cancelled, and commencement was postponed then downsized. That hurt. For my Creative Writing students, our annual Sketch Show couldn’t happen, our literary magazines went unsold, and the Alabama Book Festival and the Flimp Festival were cancelled. That hurt, too. From home, I tried to teach online while also navigating my own children through it at the same time. It didn’t go well. I know these circumstances don’t compare to losing a loved one to COVID, being laid off, or having a business close down, but they do matter. (In my opinion, one of the worst things we can do with suffering is make it comparative.)

In my main teaching gig, I can truly say that I like the energy in an American high school. I’ve taught mostly twelfth graders for the last decade, and I especially enjoy their energy in the spring as graduation approaches. Last spring, though, prom was cancelled, and commencement was postponed then downsized. That hurt. For my Creative Writing students, our annual Sketch Show couldn’t happen, our literary magazines went unsold, and the Alabama Book Festival and the Flimp Festival were cancelled. That hurt, too. From home, I tried to teach online while also navigating my own children through it at the same time. It didn’t go well. I know these circumstances don’t compare to losing a loved one to COVID, being laid off, or having a business close down, but they do matter. (In my opinion, one of the worst things we can do with suffering is make it comparative.)

But it’s like I tell my students: a failure is only a failure if you don’t learn something from it. If we’re willing to learn from this year’s failures, we’ll see that 2020 has provided a powerful lesson for the education community. In recent years, corporate interests, reformers, and anti-union types had been pushing online education as the wave of the future. This concept touted efficiency and “choice” with a “course in a can” and software that grades assignments instantly, while the teacher would become a “content delivery specialist.” However, teachers and our unions have known that these reforms would cut teacher jobs, leave remaining teachers with huge “classes,” and ultimately, be unsatisfactory to students and their families. 2020 has shown the nation what teachers knew all along: online learning is not suited to large-scale, mainstream schooling. The flaws have been glaring and obvious. The elimination of social interaction, the problem of childcare, the presence of technology glitches, and the need for on-site assistance have led to frustration, loneliness, depression, and fatigue. Student engagement has plummeted, and course failures have skyrocketed. Online learning should be a component of education in the future, but it can’t replace being in-person on a school campus. And I’ve noticed, during the last nine months, that those previously vocal education reformers haven’t been on the TV news saying, “See, look how well it’s working! We told you it would!” Nope, they’ve been mighty quiet.

When the pandemic is behind us and schools are fully operational again, there will be people who’ll pop up and declare that what we should learn other lessons instead. One alternative lesson will be that the failures of virtual learning were caused by a lack of training for teachers— and those folks will have training products to sell. Another will be that the failures were caused by inadequate technology— and those folks will have technology products to sell. Yet another will proclaim that we’ve worked out the kinks now, so it’s time to invest in streamlining the system we’ve run roughshod over unexpected terrain— and those folks will also have products to sell. The people who’ve invested money and time in promoting and selling online education aren’t going to recognize defeat, pack up, and go home. They’re businesspeople, entrepreneurs, and venture capitalists – not educators – and they’ll see opportunity in our post-pandemic disarray.

Unlike those businesspeople, I am a teacher (and a parent), who has seen the ground-level realities firsthand. The truths I’m sharing are simple, and I don’t have anything to sell. First, in-person learning is superior to online learning for the vast majority of children. Second, having children on-site at a school is better for most families. Third, children learn more than just their courses’ subject matter at school. Since March, teachers’ work has been less about teaching and more about content delivery. Our ability to enforce guidelines and policies has been severely hampered. Our choices for connecting with and motivating students are severely limited. Put bluntly, teachers do a better job in-person with students in our classrooms. And that can happen again when we’ve got this terrible disease under control.

Unlike those businesspeople, I am a teacher (and a parent), who has seen the ground-level realities firsthand. The truths I’m sharing are simple, and I don’t have anything to sell. First, in-person learning is superior to online learning for the vast majority of children. Second, having children on-site at a school is better for most families. Third, children learn more than just their courses’ subject matter at school. Since March, teachers’ work has been less about teaching and more about content delivery. Our ability to enforce guidelines and policies has been severely hampered. Our choices for connecting with and motivating students are severely limited. Put bluntly, teachers do a better job in-person with students in our classrooms. And that can happen again when we’ve got this terrible disease under control.

In the meantime, I hope that we’ll move into 2021 wiser from this experience. There will be voices in our nation and in our communities that urge us to believe the rhetoric that says: so much has gone online, so education should, too. Now, however, we’ve seen it for ourselves, and we know about the flaws and drawbacks, especially for students who lack broadband access, a home computer, or parental support. And most especially for students who need social services and special education services. We’ll have more virtual schooling to do in the first half of 2021, but I hope that administrators nationwide are considering what will happen afterward. More than anything, I hope they don’t forget what they’ve witnessed as their anxious deliberations about how to get us back on track in 2021 get underway.

December 22, 2020

Watching: “Out of Print” (2013)

I’m a little late to the game on this documentary, which came out in 2013, but I’m glad that I didn’t miss it entirely. Out of Print focuses on the future of knowledge and ideas, mainly with respect to books and the internet as methods for transferring and preserving those things.

I have a two-fold interest in these subjects. First, as a writer, I want a better understanding of how my work will be shared and, hopefully, purchased. I started in book publishing twenty years ago, when e-books were new and Amazon only sold books, and I’ve seen tremendous changes in this business. Second, as a teacher, it was compelling to watch the snippets with teenagers, who were explaining how they go straight to the internet for anything. The question we all ask is: how do we reach this generation, which expects reading be a quickie thing and which prefers instant results to searching?

This documentary address both, albeit in fifty-five minutes all total, so it’s more of an overview than a deep dive. However, I immediately considered showing it in my Creative Writing classes, because of that.

December 16, 2020

Second Reading Period for “Nobody’s Home” Begins Today

Today begins the second reading period for my new project Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore. This reading period will end on February 15, with works accepted during that time being published in spring 2021. Hopefully, you’ll see the project’s ads on New Pages and Facebook.

Today begins the second reading period for my new project Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore. This reading period will end on February 15, with works accepted during that time being published in spring 2021. Hopefully, you’ll see the project’s ads on New Pages and Facebook.

The first reading period went from October 1 until December 15. I’ll be reading those submissions between now and New Year’s. The first batch of works in the anthology will be published in January.

Things are moving right along with the project. I’ve been posting on my editor’s blog, which is called Groundwork, and posting on social media while submissions have been coming in. The original plan had involved some travel to talk with people around the South, but COVID has put a damper on those notions for now.

December 2, 2020

16,425 days: The Whitehurst Case

[image error]It has been 16,425 days since December 2, 1975, the day that a 33-year-old black man named Bernard Whitehurst, Jr. was shot and killed by a white Montgomery, Alabama police officer. Whitehurst was married, had four children under age 5, and worked as a janitor at a McDonald’s. At the time he was killed, police were chasing him as an armed robbery suspect, but he was the wrong man. Whitehurst was only walking the area, and his clothing did not fit the description of the robber. Yet, the officer who shot him claimed that Whitehurst had fired first. That account was backed up by a pistol laying in the grass nearby.

After Whitehurst was killed, police did not notify his family. Instead, his body was taken to a funeral home and embalmed, and the Whitehursts found out about his death when his mother read it on the front page of the Montgomery Advertiser the next morning.

Soon, what became known as the Whitehurst Case was sparked by an allegation that the pistol was placed beside Whitehurst’s hand after he was dead. Internal police investigations began in early 1976, and the family filed a wrongful death lawsuit in April. However, as the year wore on, no officers faced criminal charges in the death of Bernard Whitehurst, Jr., and the family’s lawsuit was defeated in federal court. Though the internal strife within the Montgomery Police Department did lead to resignations and firings, the Whitehurst family did not reach any resolution that they regard as justice.

Today is the 45th anniversary of Bernard Whitehurst, Jr.’s death. The family has now been waiting 16,425 days for justice. His widow has been living with this tragedy for two-thirds of her life, and his children have lived nearly their entire lives without him. As many in our nation make calls for justice for recent victims of police shootings, those calls shouldn’t neglect or exclude victims from further back in the past.

[image error]While the intensity of the Whitehurst Case had died down by 1977, its effects have lingered. The family has continued to live in Montgomery, and new calls for justice have been made by his now-grown children. Recently, a mural in downtown Montgomery that included Bernard Whitehurst, Jr. was dedicated to victims of police violence. To learn more about the Whitehurst Case, then and now, Closed Ranks offers a more detailed account of the story, including what has happened in the years since.