Foster Dickson's Blog, page 2

August 5, 2025

A Quick Tribute to “Junkyard Sal” June Mack

She played a prominent role in one of the classic exploitation films of the 1970s. Then she basically disappeared from the movie business . . .

played Junkyard Sal in Russ Meyer’s Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens. Meyer was known for campy exploitation films in the 1960s and ’70s, like Up! and Supervixens, which featured lots of big-breasted women. Most are rated X and are considered to be adult films. 1979’s Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens features a young man named Lamar Shedd, who is desirable to the ladies but there’s a problem: he only really wants anal sex. June Mack’s character is the proprietor of the junkyard where Lamar works. Full-figured and half-dressed, her dark skin contrasts sharply with her striped overalls or her pink nightie. The assertive Junkyard Sal is more interested in having Lamar in her little shack of an office than she is in having him work among the scrap metal. The scene in which she gets Lamar into her bed is a mix of silly overacting and soft-core porn, with Sal manhandling Lamar as he tries to survive the experience.

June Mack led a short, unconventional life. She was born in 1955 in Louisiana and was murdered in Los Angeles in 1984. She would have been in her mid-20s when Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens was released and just shy of age 30 when she was killed. One internet source provides a lengthy accounting of the incident when she was shot to death, with facts about her life sprinkled in. It explains that she primarily made her living as a prostitute or madam and from phone sex, though she had appeared in some pornographic movies.

June Mack led a short, unconventional life. She was born in 1955 in Louisiana and was murdered in Los Angeles in 1984. She would have been in her mid-20s when Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens was released and just shy of age 30 when she was killed. One internet source provides a lengthy accounting of the incident when she was shot to death, with facts about her life sprinkled in. It explains that she primarily made her living as a prostitute or madam and from phone sex, though she had appeared in some pornographic movies.

Other posthumous sources, two episodes of The Rialto Report podcast from December 2021 and January 2022, also give insight into her life and her death. The podcast is devoted to stories from the film industry, so that is the main focus. After some noir-ish introductory material in one of the two episodes, we get this:

June Mack was June Cassandra Mincher. Born in Louisiana in January 1955. Eighth child in a family of dirt-poor, hardscrabble, ex-sharecroppers. Food was always in short supply. Love and affection were non-existent. June grew up ignored and forgotten. She retreated to a fantasy world. Took refuge in TV re-runs of old movies. Harlow. Lombard. Monroe. Vampy, trampy blondes. Women with smooth skin and pointed noses. A southern black girl didn’t have the luxury of idols that looked like her.

Then June hit puberty. She got curves, got noticed, and got options. Suddenly life happened. No more hopping tables at the local Hi-D-Ho. She got attention and exploited it. She parlayed it into cash the most old-fashioned way. She took control on the vinyl tuck and roll, pleasing the light-skinned boys she barely even knowed. Her new found power bought a one-way greyhound ticket out of the south.

However, it wasn’t as simple as her being just a Southern girl come to the big city. In a 1980 article in Film Comment magazine about working with Russ Meyer, film critic Roger Ebert – who actually wrote Beneath the Valley of the Ultra-Vixens – had this to say: “The black girl we used, June Mack, spoke without any trace of an accent, so we hired a girl who had formerly come from Mississippi to dub her voice.” She had left everything, even her accent, behind. In LA, June Mincher became June Mack, a sex worker who drove a lavender-colored Rolls Royce and carried around thousands of dollars hidden in her wig.

The narrator of The Rialto Report calls June Mack a “footnote,” which is probably a fair assessment of her place in film history. But her story is a complicated one: born in the Deep South the same year as Emmett Till’s murder and Rosa Parks’s arrest, grew up poor in a big family, used the little that she had to her advantage, left the post-Civil Rights South for the West Coast, and played one memorable character in one cult-classic film. Then she was killed, possibly by a bullet that was meant for someone else, in a situation that is still not clear to this day.

June Mack would have turned 70 earlier this year.

July 29, 2025

My review of “The Year in Review 2024” by Out Loud Huntsville

I was proud to review the annual poetry anthology by Out Loud Huntsville, titled The Year in Review 2024, for the Alabama Writers Forum and just got word that the review is posted. The book was self-published by the group. Their website explains: “Out Loud HSV is a spoken word community in Huntsville, Alabama hosting regular events, open mics, and poetry slams in an effort to grow the literary arts and creative writing in our area. We hope to accomplish this by providing a platform for people to interact with other writers and readers, and grow their own skills.” This is their ninth anthology.

I was proud to review the annual poetry anthology by Out Loud Huntsville, titled The Year in Review 2024, for the Alabama Writers Forum and just got word that the review is posted. The book was self-published by the group. Their website explains: “Out Loud HSV is a spoken word community in Huntsville, Alabama hosting regular events, open mics, and poetry slams in an effort to grow the literary arts and creative writing in our area. We hope to accomplish this by providing a platform for people to interact with other writers and readers, and grow their own skills.” This is their ninth anthology.

July 26, 2025

Forthcoming in “Nobody’s Home”— Two New Works!

For Immediate Release

July 26, 2025

Nobody’s Home will publish two new works!

On August 9, 2025, the online anthology Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore is adding two new works of creative nonfiction by writers in the South. With a focus on the beliefs, myths, and narratives in Southern culture during the five-plus decades since 1970, these new works constitute the anthology’s sixth expansion.

The two contributors are Terry Barr and Dr. Janet Lynne Douglass, both of whom have contributed essays previously. Set in Alabama and South Carolina, Barr’s essay discusses the tenuous place that Halloween holds in a culture with diverse interpretations of the Christian faith. Douglass’s essay is set in the 2000s and looks back at her experiences operating a rural healthcare facility in South Carolina.

Editor Foster Dickson is proud to offer these additional essays that center on beliefs, myths, and narratives in the modern South. To learn more about the project, its focus, and its goals, you can read Foster’s introduction to the project “Myths are the truths we live by,” or other posts in his editor’s blog Groundwork. Writers who are still interested in adding their own voices to the anthology should read the submission guidelines to find out how to submit. The next Open Submissions Period for creative nonfiction will begin in April 2026, though reviews and interviews will be considered year-round.

The newly published works will be rolled out on Facebook on Saturday, August 9, and can also be accessed on the Index page later that day.

July 13, 2025

Reflecting on the Village Writing Project’s Summer Institute

The National Writing Project (NWP) and its site-based summer institutes for teachers were brought to my attention about twenty years ago by a fellow writer and teacher named Susan Shehane. Susan was a wonderful and kind person, who taught high school English in Wetumpka. She and I got to know each other because of her long essay “Alabama Listening in the Cold War Era,” which contained an array of loosely connected stories of growing up in the years after World War II. The essay version had won the Alabama School of Fine Arts’ creative nonfiction contest for teachers – when that was still going on – and in seeking a publisher for it, Susan had encountered one editor after another who wanted to change it fundamentally into something else. Frustrated by this, she asked me to help her self-publish it. It was during our work together that she encouraged me to attend the summer institute at Auburn’s then-Sun Belt Writing Project, an iteration (prior to the current Village Writing Project) that was founded in 1981. As a fellow English teacher, Susan believed I would get a lot out of it . . . but, on my end, there was always a reason to put it off: the need for childcare, work on other projects, conflicts with the dates of the institute. Those practical concerns ate up about fifteen years, then COVID hit in 2020, then I left my job as a public school teacher in 2022. By then, the Sun Belt Writing Project had gone defunct. (No source I’ve seen gives certain year that it ended.)

After a short few years without a site at Auburn, the Village Writing Project became the university’s current NWP affiliate. My revived interest in the institute came about through my role as our college’s writing assistance guy. Because what I do is like a writing center, I had met a few folks at Auburn University’s Miller Writing Center and, through them, became aware of the Village Writing Project. Their first summer institute had been held in 2024, and I jumped on board for their second one this summer.

The NWP’s summer institute is a “professional development experience focused on providing K-12 teachers, administrators, and others with opportunities to collaborate, reflect, write, and grow together [and] a space to learn from and with other educators and to develop the knowledge, the network, and the agency to teach beyond the standards, to engage and explore writing as individuals, and to gain insight into issues of social justice and equity that face our classrooms and communities today.” I doubt if being a teacher of writing has ever been easy . . . for anybody who has ever tried. The challenges are numerous: there are myriad ways to teach this skill, students often want to stick to previous teachers’ methods, there are just as many ways to do it right as to do it wrong, each genre has its own modes and manners . . . These variables often lead to resistance among students (and parents, too). So, in our profession, we are always looking for new ways to impart our lessons.

In that spirit, the focus of the Village Writing Project’s summer institute, led by Auburn professors Mike Cook and Charlie Lesh, was something called multimodal writing. This relatively new idea says that everything we read and many things we write or compose in modern culture consist of multiple modes of communication: not only words as a block of text, but also font choices, colors, imagery, layout grids, movement, sounds, video, voiceovers. So, because that is true, we should consider and include these aspects as we teach writing to our students. I’ll admit that I was at first resistant to this idea, since those elements seem to me more like graphic design than writing per se. But I kept an open mind, read what we were given, listened to what was said, and considered these ideas. Within a day or two at the institute, I began understand the point that was being made. Almost every bit of “writing” that we consume in modern culture comes to us in some form that is more dynamic than black text on white paper. We all look at websites, read magazines, see billboards, view commercials, watch TV and movies, scroll social media posts, look at fliers, regard signage, almost all of it utilizing some form of design or presentation that is not simply black serif text on a white background. Then, at school, writing teachers mostly want students to produce black serif text on a white page— just words, no fancy fonts, no color bars, no pull quotes, no movement, no graphics, no pictures . . . just black serif text on a white page. The proponents of multimodal writing raise the question of why we aren’t teaching writing in a way that corresponds with real-world consumption habits.

The main portion of the two-week summer institute ended a month ago (today), and we will reconvene briefly this fall for our follow-up. The experience has broadened my mind about what it means to “write” and to teaching writing in the 21st century. What resulted from the experience, for me, were a new set of branded graphics related to my own writing work and a multimodal writing assignment for the Literature and Music survey course that I’m teaching this fall. The branded graphics were something that I had wanted to achieve for sometime, a way to tie together the promotion of disparate aspects of my work – blog, column, books, poetry, quotes – within one consistent set of recognizable imagery. What that meant was taking the colors on the website, expanding the color pallet, using a consistent set of fonts, standardizing the imagery, and tailoring each graphic to its use. The writing assignment for the literature survey class was more cut-and-dried, though its formation was aided by the ideas in the institute: how do people process and understand sound, imagery, and writing when they appear together?

The main portion of the two-week summer institute ended a month ago (today), and we will reconvene briefly this fall for our follow-up. The experience has broadened my mind about what it means to “write” and to teaching writing in the 21st century. What resulted from the experience, for me, were a new set of branded graphics related to my own writing work and a multimodal writing assignment for the Literature and Music survey course that I’m teaching this fall. The branded graphics were something that I had wanted to achieve for sometime, a way to tie together the promotion of disparate aspects of my work – blog, column, books, poetry, quotes – within one consistent set of recognizable imagery. What that meant was taking the colors on the website, expanding the color pallet, using a consistent set of fonts, standardizing the imagery, and tailoring each graphic to its use. The writing assignment for the literature survey class was more cut-and-dried, though its formation was aided by the ideas in the institute: how do people process and understand sound, imagery, and writing when they appear together?

Having let the lessons of the institute settle in, I would recommend to any writing teacher to participate in one of these NWP offerings. (And don’t wait as long as I did!) Most of my teaching career has been spent on the high school level, but my work today has me with college undergraduates. The lessons are just as valuable where I am now. Beyond that, the group of middle and high school teachers I was with augmented the learning offered by the institute’s leaders, who are university professors, by adding their own insights on teaching both English language arts and social studies. I got to think about what I was producing, of course, but I also learned from the other teachers as I saw how they interpreted these ideas and created their own methods for writing and teaching. And even beyond the learning and the camaraderie, there is the practical benefit of earning those CEUs for the ol’ teaching certificate renewal!

June 30, 2025

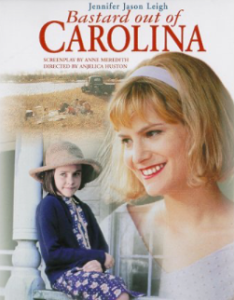

Southern Movie 78: “Bastard Out of Carolina” (1996)

The 1996 made-for-TV adaptation Bastard out of Carolina brings us the story of a girl named Bone, born Ruth Ann Boatwright to a single mother in a rural community and an absent father whose name is never spoken. The film is based on Dorothy Allison’s 1992 novel of the same name, which was a Finalist for the National Book Award. (The story is based heavily on her own life.) The movie, made for the cable channel Showtime, was controversial at the time of its release for its brutally realistic handling of a sexual assault against a child, though it won director Anjelica Huston an Emmy. Jennifer Jason Leigh stars as Bone’s mother Anney, and first Dermot Mulroney then Ron Eldard as her two stepfathers. Playing Bone was actress Jen Malone’s first major role. Bastard out of Carolina offers a harsh look at life in the backwoods regions of the Carolinas in the years after World War II.

The opening scenes of Bastard out of Carolina have us watching four people riding in a black sedan down a rural two-lane road. Three adults are in the front: a man driving, a man in the passenger seat, and a woman in the center. They are drinking and allude to getting to an airport. Soon, they make reference to a fourth passenger, a woman sleeping in the backseat. She is the sister of Earle, the man in the passenger seat. However, momentarily, the driver stops paying attention to the road as he looks through the glove compartment for cigarettes and rear-ends a truck, which throws the sleeping woman in the backseat of the windshield. She is pregnant and hurt badly. At the hospital, the expectant mother Anney (Jennifer Jason Leigh) survives, and Bone is born.

There is a jovial scene at the hospital as Anney recovers, yet the celebratory tone changes when Anney’s sister Ruth (Glenne Headley) and their mother Granny (Grace Zabriskie) go to get Bone’s birth certificate. The man at the desk is unwilling to hear their workarounds for stating Bone’s father’s name, and he stamps the paperwork with “Illegitimate.” Next, we see their aging home with its gray-wood siding, rusted metal roof, and yard strewn with firewood. Ruth and Granny are sitting on the porch, and Anney comes out to say a few angry words, being livid at the designation put on her child. The matriarch’s ideas about are: who cares what other people think?

In an attempt to alter the situation, Anney attempts to go to the courthouse one day, after she gets off from her job as a waitress, to “explain” the story to the clerk. It wasn’t that there is no father, her sister Ruth explains, but in the wild atmosphere that combined a car wreck and child’s birth, she had just gotten confused. The clerk is unamused and unconvinced, refusing to certify the birth certificate.

Soon after this, Anney is being courted by Lyle Parsons (Dermot Mulroney). He is a good and kind man who enjoys Anney and is a good stepfather to the young Bone. The couple quickly get married, and a child is on the way. But Lyle is killed in a car wreck. Anney is without a man again, this time with two children in tow.

Not yet twenty minutes into the movie, we see that Anney is plagued by two major problems: poverty and bad luck. Yet, her life is about to change. We believe things could be looking up. One evening, Earle brings his co-worker Glenn Waddell (Ron Eldard) into the cafe where Anney works, to introduce them. Then after Anney and Glenn have started dating, the courthouse – which holds Bone’s birth certificate – burns. It really looks for a moment like Anney, Bone, and her younger daughter Reese may be getting the breaks that they need. After all, Glenn is a Waddell, one of the well-to-do families in the area.

At first, it seems like Glenn will be a stand-up guy. He really likes Anney and spends time courting her in a nice way. But there are signs that he might have problems. We see him get into a fight with another man at the sawmill where they work, and the two beat each other bloody. Glenn also has trouble keeping a job. Perhaps more importantly to the story, we also sense that Bone has a bad feeling about him. Yet, by the half-hour mark, Anney is leaving her girls with Granny and the aunts to go marry Glenn. Granny has some choice words about the man, saying that the Waddells are stuck up, but Anney insists that Glenn loves her. What is perhaps most pertinent is: Anney is pregnant, again.

After the marriage, Glenn continues to seem like a good catch for Anney. They have moved into a nicer house, and we see him putting together a rocking horse for the new baby, which he hopes is a boy. The girls Bone and Reese play nearby on the porch. But things change very much on the night that Anney goes to the small hospital to have the baby. Glenn waits in the car outside, while the girls sleep in the back seat. Anney is having trouble giving birth, so it’s taking a while. While they wait, Glenn tells Bone to come up to the front seat, where he tells her that he loves her— but his tone is not what we would expect. His heavy breathing and strong embraces of the little girl in the dark show us our worst fears. Glenn molests his stepdaughter in the car, then shoves her aside and tells her to go to sleep. The tension of the scene is elevated when Glenn comes outside to the car in the morning, and he is distressed, revealing that their baby boy has died and that Anney can have no more children. Bone and Reese are left to cope with this on their own.

What follows is a series of moves for the family. An overdubbed narration from Bone explains that they moved constantly, because Glenn couldn’t keep a job. During these scenes, we see Glenn talking to his own father, a man in a suit standing outside a white-columned building. The elder Waddell says that, of his three sons, one is a successful lawyer, one is a successful dentist, and the last is Glenn. When will Glenn ever do something to make his father proud, the elder man wants to know. Then he answer his own question, Never.

As Bastard out of Carolina nears the one-hour mark, Anney has grown tired to Glenn’s inability to provide for their family coupled with his pride about taking help from their relatives. The girls are seen walking the railroad tracks, picking up bottles to get the deposit money to buy cans of pork and beans. During this scene, Reese asks Bone why Glenn doesn’t like her. At the house, Anney spreads ketchup on saltines for their dinner. When the evening comes, Anney takes her daughters to her sister’s house, while she goes out, and Glenn sits in the dark, since their electricity has been cut off.

By this time, Glenn has cracked. At his parent’s house for a child’s birthday party, his wife and stepdaughters are obviously unwelcome, and his father won’t pay attention to his news about a good job. The tension culminates in a physical altercation between the father and son when Bone drops a crystal pitcher of tea and shatters it. Back home, Glenn is working on the car when Bone and Reese run by, knocking over his thermos. He jumps up and scolds Bone, who mocks him to Reese as they run on. Glenn loses it and takes her upstairs where he beats her with a belt, while Anney pounds on the locked door, trying to intervene. Glenn is making so little money that Anney goes back to waitressing, which leaves Glenn home with the girls in the evening. This is when the beatings and the assaults begin for Bone with regularity. They are so severe that she steps gingerly, almost limping, while trying to hide her injuries from her mother. They can be denied no more when she is taken to the hospital and has a broken tailbone.

By this time, Glenn has cracked. At his parent’s house for a child’s birthday party, his wife and stepdaughters are obviously unwelcome, and his father won’t pay attention to his news about a good job. The tension culminates in a physical altercation between the father and son when Bone drops a crystal pitcher of tea and shatters it. Back home, Glenn is working on the car when Bone and Reese run by, knocking over his thermos. He jumps up and scolds Bone, who mocks him to Reese as they run on. Glenn loses it and takes her upstairs where he beats her with a belt, while Anney pounds on the locked door, trying to intervene. Glenn is making so little money that Anney goes back to waitressing, which leaves Glenn home with the girls in the evening. This is when the beatings and the assaults begin for Bone with regularity. They are so severe that she steps gingerly, almost limping, while trying to hide her injuries from her mother. They can be denied no more when she is taken to the hospital and has a broken tailbone.

After Bone has healed at her aunt Alma’s, she is taken to live with her aunt Ruth, who is sick. This relieves the tension with Glenn, and he passes out of our view of a bit. While she is living with her aunt, Bone is asked whether Glenn has ever touched her “down there,” and though she hesitates, she says no.

Then her aunt Dee Dee (Christina Ricci) shows up. Dee Dee is made up and wearing fine clothes in a way that none of the other women do. Dee Dee has come home because she is out of money, but she makes it clear that she never intends to come home again.

Soon, Bone is back home, and the same things start up again. Ruth has died, and when they are getting ready for the funeral, Bone back-talks Glenn, which leads to a severe beating. Anney lies on the floor helpless outside. Later, after the funeral when the family has gathered, Raylene discovers Bone’s wounds when she is helping the girl in the bathroom. She reveals the wounds to Earle and the other men, who take Glenn outside and beat him to a pulp. As the beating goes on, Anney protests, and Bone says her tearful apologies, believing that she has caused the situation.

With only about fifteen minutes left in the film, we know that the breaking point has been reached. Next we see Bone, she is living with Raylene, her independent-minded aunt who has remained unmarried. As she and Raylene talk, The Waddells ride by in their fancy boat and glare. Bone says that she hates them, but Raylene admonishes her not to build a life on hate.

As this is being said, Earle pulls up in his truck to take them to Alma’s house. Her husband has gotten antagonistic and violent, and she needs support now. While they’re there, Anney offers Bone the chance to come home, but Bone says no, she’s rather stay at Raylene’s. Anney knows that she has failed her daughter. During these scenes, we believe that the worst of it is over, but the worst is yet to come. When Bone is alone at Raylene’s, Glenn shows up. He is nice at first, asking for a glass of tea, but he soon reveals his reason for coming. Anney has agreed to come back to him but only if Bone agrees, too. We know that Anney knows about the beatings but not the molestation. What follows, after Bone says that she refuses to come back to live with him as though they’re a family, is a brutal attack and rape. Glenn loses it and attacks the girl with all of his might, eventually throwing her on the floor and assaulting her terribly. While this is occurring, Anney shows up and walks in on her estranged husband raping her child. Anney busts a milk bottle over his head and takes Bone to the car, as Glenn attempts to excuse his behavior and make it the way he wants it to be. For a moment, Anney shows that she does not know who to choose: Glenn, a violent rapist who does not provide for them, or Bone, the helpless victim of a grown man’s brutal assaults. At the hospital, a policeman tries to get Bone to tell him who did this to her, and we learn that her mother is not there at the hospital with her. Raylene takes her home.

In the end, Bone must come to terms with what her mother has allowed or enabled. Her aunt Raylene tries to explain that people seem to do terrible things to each other, even to the ones they claim to love. In the movie’s final scenes, Anney shows up to talk Bone, who by this point is stronger than her mother. They talk over a campfire at Raylene’s, a mother who has made awful mistakes and a child who has suffered for those mistakes.

Dorothy Allison’s 2024 New York Times obituary shares that her 1992 novel was published “to almost unanimous acclaim. Here was a novel that did not romanticize the noble poor, as Ms. Allison might say, or make cartoon characters of an eccentric Southern family, or lard its hardscrabble tale with ideology.” Continuing, we read, “Ms. Allison was lauded — along with other contemporary Southern writers, including Harry Crews and Bobbie Ann Mason — as pioneering a new genre, often called Grit Lit or Rough South.” Another of her novels, 1998’s Cavedweller, was also made into a movie in 2004.

As a document of the South, Bastard out of Carolina deals with some brutal realities. The kinds of laws that declared Bone to be “illegitimate” and the kind of behavior exhibited by Glenn are not particular to the South, of course. But the practical realities that led to situations like these were common in the South: patriarchy, white supremacy, and poverty. Looking at Bone’s case, a child without a father could not be considered “legitimate.” (Every child has a mother, indisputably, but the mother didn’t conceive a child without a partner, which makes these laws and norms quizzical at best. The mother and the child live with the consequences of the father’s absence.) In the movie, this is also a world of white people, even though South Carolina has long had a significant black population. The only African Americans that we see are a small group gathered by a fence during one of the scenes when the family is moving into another house. This detail tells anyone who understands Southern culture that Glenn, Anney and the girls have been “reduced” (socially) to moving into a black neighborhood. So it has be clear right away that the story we’re watching is not so much a story of the South as it is a story of the poor, white, patriarchal South. Anney’s problems and subsequently Bone’s problems arise from those realities.

Considering this further, we also have to add ignorance and classism to this mixture. Almost all of the characters who we meet in Bastard out of Carolina are either rough, rural people who eek out a living from meager resources or members of a disposable Southern working class. Glenn comes from the upper echelons of this local society, but his first flaw – but by far not his worst flaw – seems to be an inability (or an unwillingness) to capitalize on the advantages of his birth. His father remarks that both of his brothers carried their privilege forward, but Glenn is a disappointment because he has not. Further, Glenn cannot hold a job or maintain a home despite pleading with Anney to marry him and trust in him as a breadwinner and head of household. This film may be the story of Bone, or potentially of Anney, but its antagonist Glenn plays the pivotal role in what occurs. The lives of these women and girls would be hard without Glenn . . . but their lives are absolutely terrible with him. Neither Anney nor Bone did anything to bring these events about; it is Glenn’s decisions that affect things the most, and the worst. Glenn’s awful crimes emanate from his character flaws and from his low/fallen status in a class-based culture. In this society, Glenn has no power, so he finds his power in physically and sexually abusing Bone, a helpless young girl whose mother has a desperate need for a husband. He is an ignorant, unskilled outcast, whose well-to-do upbringing has not prepared him for the realities of a working-class life. And he fails to be Man in every way. (Though he may not be a stellar example, Earle is the best example of manhood in the story, since Glenn’s father is a loveless and only concerned about jobs and status.) Sadly, by the end of the film, we’re not looking for the female characters to triumph so much as survive. Of all of them, Raylene seems to fare the best. Why? Perhaps because she remains unmarried, lives humbly and simply, and relies only on herself.

June 20, 2025

Apologies for all the emails . . .

It's a subscribers only post. Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

SubscribeJune 15, 2025

The Open Submissions Period for “Nobody’s Home” ends today.

This year’s Open Submissions Period for Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore closes today. All submissions made between April 15 and June 15, 2025 will receive a response in July. Accepted submissions will be published in August 2025.

This year’s Open Submissions Period for Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore closes today. All submissions made between April 15 and June 15, 2025 will receive a response in July. Accepted submissions will be published in August 2025.

This was the fourth Open Submissions Period for Nobody’s Home. The project was founded in 2020, and four reading periods were held within a year’s time, from the latter half of 2020 through the first half of 2021. Subsequently, unsolicited submissions have been read during an Open Submissions Period in the spring, with accepted works published each summer.

Today, Nobody’s Home features more than fifty essays that discuss a variety of beliefs, myths, and narratives that have affected or have arisen from Southern culture since 1970. In addition, the project offers secondary-education lesson plans for English and Social Studies classrooms, suggestions for documentaries about Southern culture, and Groundwork, the editor’s blog.

June 5, 2025

A Deep Southern Throwback Thursday: “Alabama Forum,” 1981 – 2002

When someone mentions the state of Alabama in the 1980s and ’90s, thoughts might turn to George Wallace’s last term as governor, the retirement and death of Bear Bryant, Bo Jackson or Charles Barkley playing at Auburn, or maybe Gov. Guy Hunt’s ethic conviction. Something the average person would probably not conjure images of: an LGBTQ newspaper. But that’s exactly what the Alabama Forum was. Published from 1981 until 2002, its archives now are held at The University of Alabama, where 245 monthly issues have been digitized.

The first issue, dated January 1981, is a cheaply put-together typescript edition, but the newspaper quickly adopted a more professional-looking, two-color format. (By the mid-1990s, there were issues that offered full-color layouts.) What is notable from the beginning is its fairly sophisticated perspective on social life and politics. Even in that initial homemade-looking issue, the content opens with a poem by “Bubba,” then has information on a lawsuit in Oklahoma, moves to an editorial about then-President Ronald Reagan, offers a listing of bars and events in the state, and remarks on an Alabama congressman’s appointment to a committee by Strom Thurmond. Browsing issues throughout UA’s archives, we see that this was not a half-baked publication full of empty rhetoric and unfounded accusations. Though no names are included in the early mastheads, we also see that it was published originally by the advocacy group Lambda, Inc., in Birmingham.

By the 1980s, activism within and from the LGBTQ community had become more visible. After the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion, the 1970s were a time of growing awareness of LGBTQ issues, and though the South’s most visible changes that decade came in the areas of race relations and gender roles, an growing awareness of what was then called “gay rights” extended to our region as well. As an example, in Birmingham, Lambda was founded in 1977. By the time the modern “culture wars” erupted, The Alabama Forum offered a perspective that was uncommon during the last decades of the twentieth century.

Further reading:

“In Montgomery, Alabama, a ‘Stonewall’ Rebellion that Didn’t Make LGBT Headlines,” from The Daily Beast

This news article tells the lesser-known story of a police raid on a club called Hojon’s in the early 1980s.

May 27, 2025

A Quick Tribute to Severn Darden, Character Actor

To those of us in Generation X, character actor Severn Darden is probably most recognizable in minor roles as college professors in two 1980s campus comedies: Real Genius and Back to School. But if not those, then possibly from seeing him either in the original Planet of the Apes movies or in the silly 1981 horror movie spoof Saturday the 14th. However, Darden had a longer and more impressive career than those roles would imply.

Severn Darden was born in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1929, the son of an attorney. He later attended the University of Chicago then was a founding member of the now-famous Second City improv group that has produced many Saturday Night Live! stars. A September 1961 New York Times review of one Second City show called Darden “an especially gifted and versatile comedian.” Less than a year later, in May 1962, the Times was calling attention to “Fresh Faces On and Off Broadway” and listed him among Cicely Tyson, Peter Fonda, and James Earl Jones as ones to watch. Though it was a lesser-known film, I think of Darden as the wily villain in the 1971 western Hired Hand, the one who gets shot in the feet and legs by Peter Fonda’s and Warren Oates’s characters as he lays in bed.

In the realm of Southern movies, Darden was in 1972’s The Legend of Hillbilly John, 1976’s Jackson County Jail, and 1981’s Soggy Bottom USA. In Hillbilly John, he played Dr. Marduke, a mystical figure who seems to appear whenever he is needed. At the end of the film, John’s love interest Lily asks if he is the Marduk from the Bible, and he replies no, that it was all a bunch of confusion, he had left Babylon long before any of that stuff happened. Jackson County Jail brought him a completely different role, cast as the small-town sheriff in a story where a woman driving across the country is arrested and sexually assaulted in her jail cell. The last of the three, Soggy Bottom USA, was an offbeat comedy that had him in the role of Horace Mouthamush, playing alongside Southern-movie mainstays Dub Taylor and Anthony James. (James was the late-night cafe guy who ended up being the secret culprit in In the Heat of the Night.)

In the realm of Southern movies, Darden was in 1972’s The Legend of Hillbilly John, 1976’s Jackson County Jail, and 1981’s Soggy Bottom USA. In Hillbilly John, he played Dr. Marduke, a mystical figure who seems to appear whenever he is needed. At the end of the film, John’s love interest Lily asks if he is the Marduk from the Bible, and he replies no, that it was all a bunch of confusion, he had left Babylon long before any of that stuff happened. Jackson County Jail brought him a completely different role, cast as the small-town sheriff in a story where a woman driving across the country is arrested and sexually assaulted in her jail cell. The last of the three, Soggy Bottom USA, was an offbeat comedy that had him in the role of Horace Mouthamush, playing alongside Southern-movie mainstays Dub Taylor and Anthony James. (James was the late-night cafe guy who ended up being the secret culprit in In the Heat of the Night.)

Severn Darden died thirty years ago today, on May 27, 1995. His New York Times obituary remarked, “Mr. Darden was widely recognized in the world of improvisational theater as a comic genius whose wacky portrayals of a German know-it-all professor and a nitpicking expert on everything under the sun influenced two generations of comic performers.”

May 20, 2025

Sharing the Good Stuff: “Where Politics is Still Possible” in Commonweal

In the article “Where Politics is Still Possible” in the April 2025 issue of Commonweal, we read about a required civics class at a small college in Oklahoma, which the writer offers as a counterbalance to the portrayals of college students that we see on the news. Writer Jonathon Malesic shares his perspective that the kinds of students who are protesting and setting up encampments at Columbia and Harvard are not indicative of the average American college student, many of whom are working-class or low-income and attend smaller colleges and universities within seventeen miles of their where they grew up. He uses Rose State College in Oklahoma and its required American Federal Government class as examples of how students can be (and are) educated to live with and work with politics in a pluralistic and diverse nation, which stands in opposition to images of students at elite universities obstructing daily operations over global political issues. Ultimately, he proposes that steady and focused grassroots efforts, rather than high-profile movements, will probably be the most successful in making America a better place to live.

As a writing teacher, I was also particularly pleased to read this from a Rice University student who is acts as editor for the institution’s public policy journal:

“I think writing forces students to think more abut their beliefs,” he said. “And because having to defend an argument is much different than simply believing it, I think students come to realize a lot more of the counterarguments and issues with their own beliefs.”

I have long taught from the NCTE’s Beliefs on the Teaching of Writing that “writing is a tool for thinking.” It’s good to see an affirmation that others understand that, too.