Foster Dickson's Blog, page 6

November 1, 2024

The First One in a Long Time: A Poem in “Boudin”

Foster’s poem “They Come, Growling” was published yesterday in the October 2024 issue of Boudin, a literary magazine housed at McNeese State University in Louisiana. The issue is a “Creature Feature” whose theme is monsters and related subjects.

This is Foster’s first poem to be published in eleven years. The last one appeared in the Birmingham, Alabama-based Steel Toe Review in 2013. This poem centers on Foster’s experiences being a teacher during the era of school shootings, with a complex set of factors affecting our ability to understand what is happening: legal and privacy concerns when dealing with minors, public safety concerns from students and parents, law enforcement’s need to withhold information while they investigate, and the news media that creates narratives by sharing limited information. Not only are these situations frightening for those involved directly, but also for anyone who learns that another school shooting has occurred. As a cultural phenomenon, the “school shooter” has become a modern monster in the same way that creatures like vampires and the wendigo appeared in the past as vague but dangerous threats lying in wait for unsuspecting victims.

October 24, 2024

The Work (as 2024 winds down)

Being a writer isn’t just a job. It’s more accurate to call it a vocation, since a writer never really turns it off. So it has been an unusual twelve months, not having a book project to work on. Definitely unusual. Faith. Virtue. Wisdom. was released in October 2023 . . . and no new projects have emerged. I wrote about this in a Dirty Boots column in June, but I’ll share it again here: recent months have been a time of contemplation, of stepping back from what I’ve been doing for the last twenty-plus years. Perhaps the catalyst was the pandemic, perhaps it is the fact of turning fifty, but it has been a time to ask, Should I keep doing things in this way? About some aspects of my life, I’ve decided, No, things are going to change.

What this past year has really been is a year of reading. For so long, I had trouble finding the time and mental energy to read for pleasure. Thankfully, that has changed. Some of it is related to “work,” if we want to call it that. In addition to reading two books to review for the Writers Forum last spring and summer – From Every Stormy Wind that Blows and Glass Cabin – I also read Zachary J. Lechner’s South of the Mind, Alexander P. Lamis’s Southern Politics in the 1990s, and Andrew Gelman’s Red State, Blue State. Rich State, Poor State from the Editor’s Reading List on Nobody’s Home. Just for kicks, I’ve gone through a couple more as well: Belonging by bell hooks, Life is a Miracle by Wendell Berry, The Spirit of Catholicism by Karl Adam, portions of Papermaking by Joseph Heller, a collection of writings by and about the Japanese poet Ryōkan called The Great Fool, the first two sections of A Theory of Moral Sentiments by Adam Smith, the collection We Are the Ones We Have Been Waiting For by Alice Walker, The World According to Garp by John Irving, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander by Thomas Merton, Loving Our Enemies by Jim Forest, Road to Heaven by Bill Porter/Red Pine, most of the stories in Barry Hannah’s 1978 collection Airships, Harold Bloom’s The Shadow of a Great Rock, and The Places that Scare You by Pema Chödrön. One benefit of having my office in the college’s library is that I pass the magazine shelf daily and have taken to reading Commonweal, The Christian Century, The American Scholar, and The Atlantic with regularity. These days, I just finished reading Martin Shaw’s Smokehole and am picking through John Dear‘s new commentary The Gospel of Peace. Books in the pipeline, which I already have copies of, include Chris Smaje’s A Small Farm Future, Ada Limon’s new edited collection You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World, Yushi Nomura’s translation Desert Wisdom: Sayings from the Desert Fathers, and Richard Hague’s memoir Earnest Occupations: Teaching, Writing, Gardening, and Other Local Work.

What this past year has really been is a year of reading. For so long, I had trouble finding the time and mental energy to read for pleasure. Thankfully, that has changed. Some of it is related to “work,” if we want to call it that. In addition to reading two books to review for the Writers Forum last spring and summer – From Every Stormy Wind that Blows and Glass Cabin – I also read Zachary J. Lechner’s South of the Mind, Alexander P. Lamis’s Southern Politics in the 1990s, and Andrew Gelman’s Red State, Blue State. Rich State, Poor State from the Editor’s Reading List on Nobody’s Home. Just for kicks, I’ve gone through a couple more as well: Belonging by bell hooks, Life is a Miracle by Wendell Berry, The Spirit of Catholicism by Karl Adam, portions of Papermaking by Joseph Heller, a collection of writings by and about the Japanese poet Ryōkan called The Great Fool, the first two sections of A Theory of Moral Sentiments by Adam Smith, the collection We Are the Ones We Have Been Waiting For by Alice Walker, The World According to Garp by John Irving, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander by Thomas Merton, Loving Our Enemies by Jim Forest, Road to Heaven by Bill Porter/Red Pine, most of the stories in Barry Hannah’s 1978 collection Airships, Harold Bloom’s The Shadow of a Great Rock, and The Places that Scare You by Pema Chödrön. One benefit of having my office in the college’s library is that I pass the magazine shelf daily and have taken to reading Commonweal, The Christian Century, The American Scholar, and The Atlantic with regularity. These days, I just finished reading Martin Shaw’s Smokehole and am picking through John Dear‘s new commentary The Gospel of Peace. Books in the pipeline, which I already have copies of, include Chris Smaje’s A Small Farm Future, Ada Limon’s new edited collection You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World, Yushi Nomura’s translation Desert Wisdom: Sayings from the Desert Fathers, and Richard Hague’s memoir Earnest Occupations: Teaching, Writing, Gardening, and Other Local Work.

Even with all that reading, I’ve still managed to do some writing on shorter pieces. I mentioned those two reviews for the Alabama Writers Forum in 2024; I also wrote three for them in 2023. After a year-long hiatus, my Dirty Boots column in November 2023 restarted with a revised subtitle: Irregular Attempts at Critical Thinking and Border Crossing. For the blog here, I’ve written fourteen of those and five more Southern Movies posts, then there have been those three new posts from the Editor’s Reading List on Nobody’s Home and one of my ruminations for the editor’s blog Groundwork. Those, the 50 GenX movies, and two Throwbacks about the twentieth anniversary of The Haiku Year and the fiftieth anniversary of the WAPX shootout add up to a little over 50,000 words over the past year. Of course, I’m also often jotting a haiku or other kind of poem about something or other.

Among the changes this year, I ended my roughly decade-long moratorium on submitting poems to journals and also dipped my toe back into the world of theater after a thirty-year absence. In the summer, I sent a handful of haiku to a genre-specific journal. Unfortunately, those came back with rejections in a few weeks. Bundles of poems also went out to two other literary journals, and one batch yielded an acceptance! —while the response to the other still up in the air. That forthcoming poetry publication will be my first in eleven years. About the theater stuff, I got the opportunity in February to take a role in an informal reading of a play for Nora’s Salon South. I must not have done too badly in the first one, since they asked me to read a role in another play in May. I enjoyed doing those, since I never had to set aside the script. I’m terrible at memorizing things!

Among the changes this year, I ended my roughly decade-long moratorium on submitting poems to journals and also dipped my toe back into the world of theater after a thirty-year absence. In the summer, I sent a handful of haiku to a genre-specific journal. Unfortunately, those came back with rejections in a few weeks. Bundles of poems also went out to two other literary journals, and one batch yielded an acceptance! —while the response to the other still up in the air. That forthcoming poetry publication will be my first in eleven years. About the theater stuff, I got the opportunity in February to take a role in an informal reading of a play for Nora’s Salon South. I must not have done too badly in the first one, since they asked me to read a role in another play in May. I enjoyed doing those, since I never had to set aside the script. I’m terrible at memorizing things!

One last change: I left the board of the Fitzgerald Museum and stepped away from coordinating the Literary Contest that I created in 2018. I joined the board under a previous museum director, who asked me to revamp what had been a contest with general guidelines. Since it was the centennial of Scott and Zelda meeting in Montgomery, the contest was built around the couple’s life events and publications. After six years, there is a strong foundation to build upon, so I handed over the reins to the current museum director.

Yet, not everything is changing. Nobody’s Home keeps rocking along on its regular path. I published one new essay in November 2023 for the invitation-only reading period, and three more from the Open Submissions Period in August 2024. Founded in 2020, the anthology now has almost sixty essays after four years of steady publication. I already discussed my Groundwork blog, and there are five books remaining in the Editor’s Reading List. Mark Newman’s Getting Right with God, about desegregation and the Southern Baptists, will be next; I’m reading it now. I foresee finishing the last ones . . . probably by the end of 2025.

And my work at the college has entered its third school year. I’m continuing as the advisor for The Prelude and as the academic writing help guy, while teaching three sections of our first-year experience course and two English courses: a general literature survey and African-American literature. The course load this fall has kept me very busy with prepping, teaching, and grading. Aside from classes, I am particularly proud to be a part of the long tradition with the literary magazine. The Prelude was founded in the fall of 1928 when Huntingdon College offered its first creative writing course, which was taught by Margaret Gillis Figh, co-author of 13 Alabama Ghosts. The magazine’s notable contributors and editors have included novelist Nell Harper Lee, storyteller Kathryn Tucker Windham, poet Andrew Hudgins, and poet Jacqueline Allen Trimble. The Spring 2024 issue – my fourth as the advisor – was available by the time everyone arrived this fall, and we’re taking submissions for the Fall 2024 issue. I also became an NASPA Certified Peer Educator trainer earlier this year. The NASPA training is part of my work with the college’s peer mentoring program and student success efforts.

And my work at the college has entered its third school year. I’m continuing as the advisor for The Prelude and as the academic writing help guy, while teaching three sections of our first-year experience course and two English courses: a general literature survey and African-American literature. The course load this fall has kept me very busy with prepping, teaching, and grading. Aside from classes, I am particularly proud to be a part of the long tradition with the literary magazine. The Prelude was founded in the fall of 1928 when Huntingdon College offered its first creative writing course, which was taught by Margaret Gillis Figh, co-author of 13 Alabama Ghosts. The magazine’s notable contributors and editors have included novelist Nell Harper Lee, storyteller Kathryn Tucker Windham, poet Andrew Hudgins, and poet Jacqueline Allen Trimble. The Spring 2024 issue – my fourth as the advisor – was available by the time everyone arrived this fall, and we’re taking submissions for the Fall 2024 issue. I also became an NASPA Certified Peer Educator trainer earlier this year. The NASPA training is part of my work with the college’s peer mentoring program and student success efforts.

After writing a similar post a year ago, it seemed like time to look around once again and make an assessment. It has felt this year like I had been slacking, but maybe not. Considering that, in the last twelve months, I am still vigorously writing, teaching, publishing, and reading . . . I guess what I’m doing is maintaining. And that’s OK right now. This period of contemplation is coming to an end, it seems, and a path forward is emerging.

October 17, 2024

Dirty Boots: “Confederates in the Attic,” Re-Visited

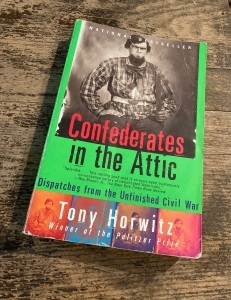

Though there is no timely anniversary to link this to, Tony Horwitz’s Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War is a book begging for a mention right now. Published in 1998, it has become a classic of Southern studies. Roy Blount’s review in The New York Times called it the “freshest book about divisiveness in America that I have read in some time.” A little more than twenty-five years later, the cultural crosscurrents that the author explored at the end of the twentieth century have come all the way to fruition today.

Most summaries say that the book is about Civil War re-enactors, but it’s certainly more than that. Horwitz started there but traveled all over the South, to cities and the countryside, to observe and talk with a variety of people. Unlike VS Naipaul’s approach for his 1988 exploration A Turn in the South, the writer didn’t stick to safe and tested sources of information that were set up for him in advance. In a town called Guthrie on the Kentucky-Tennessee line, Horwitz stopped at a local dive bar where one patron asked suspiciously whether he was with the FBI. He remarks on Vicksburg’s local museum being “the most eccentric” and “politically incorrect” site he had visited up to that point. The book’s final chapter opens with Alabama’s then-reinstated chain gangs on the highway, which the author saw as he drove into Montgomery. This sight incurred a few remarks on my hometown’s practice of billing itself, with no sense of irony, as both a Civil War and a Civil Rights history destination. Forget about the author’s conversation with a latter-day secessionist who lived in a black neighborhood in Charleston or that chapters are titled “The Civil Wargasm” and “Gone with the Window,” where else would you read that Shelby Foote would have preferred to just be a novelist?

Most summaries say that the book is about Civil War re-enactors, but it’s certainly more than that. Horwitz started there but traveled all over the South, to cities and the countryside, to observe and talk with a variety of people. Unlike VS Naipaul’s approach for his 1988 exploration A Turn in the South, the writer didn’t stick to safe and tested sources of information that were set up for him in advance. In a town called Guthrie on the Kentucky-Tennessee line, Horwitz stopped at a local dive bar where one patron asked suspiciously whether he was with the FBI. He remarks on Vicksburg’s local museum being “the most eccentric” and “politically incorrect” site he had visited up to that point. The book’s final chapter opens with Alabama’s then-reinstated chain gangs on the highway, which the author saw as he drove into Montgomery. This sight incurred a few remarks on my hometown’s practice of billing itself, with no sense of irony, as both a Civil War and a Civil Rights history destination. Forget about the author’s conversation with a latter-day secessionist who lived in a black neighborhood in Charleston or that chapters are titled “The Civil Wargasm” and “Gone with the Window,” where else would you read that Shelby Foote would have preferred to just be a novelist?

This book was one among several that set a high bar for examining the modern South as a harmlessly quirky but sometimes dangerous place with diverse local scenarios. Moving past white-authored Civil Rights memoirs, like Curtis Wilkie’s Dixie, which was published around the same time, Confederates in the Attic asked important questions in the 1990s: what came after the movement, and what’s going on down there now? The Civil Rights movement had changed everything. But it ended – according to historians – in the late 1960s, and harping on that bygone era wasn’t going to yield the kinds of new insights that the South needed in the late 1990s, and still needs now. The 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s were a period of change, of reconstruction, of evolution— but into what? Roy Blount also wrote in his review, “Most of the folks Horwitz meets are mellow, but in some cases geniality goes hand in hand with right-wing nuttiness.” (The Harvard professor who reviewed it for The Journal of Southern History also praised its off-the-beaten-path approach and commended Horwitz for his work, but used some of the word count to complain that there was no bibliography.) Put simply, Horwitz took a deep dive to find some answers firsthand. Yet, please don’t assume from my description that the answers are just sitting in this one book, waiting to be discovered. Works like this one are myth-busters that provide more questions than answers in the twenty-first century. Especially for the people who claim today that nothing has changed in the South.

I know that I’m often wasting my time when I encourage people to read, or to learn about history, or to know facts. But this crazy South we live in sure does beg us to understand ourselves in ways that could lead us out of the craziness, not further into it. One of those lessons is that Southerners didn’t magically become who we are today (like, the day after Barack Obama was elected in 2008). We’d been working on our current incarnation for some time, and it’s a doozy! Politically, we’ve thrown our weight behind an orange-tinted real estate developer from New York City, a couple of culture-war governors, and their trickle-down henchmen in state legislatures. In some ways, I guess it’s no stranger than switching die-hard party affiliation that had lasted for more than a century to embrace an Orange County ex-movie star with a boy-next-door smile. In other ways, I would hope that we’d be slamming on the collective brakes and gasping, Wait—what have we done? I’m straying off my main message, but I am actually trying to make a point: if Southerners understood our own past better, we might not make so many bad choices in the present.

I know that I’m often wasting my time when I encourage people to read, or to learn about history, or to know facts. But this crazy South we live in sure does beg us to understand ourselves in ways that could lead us out of the craziness, not further into it. One of those lessons is that Southerners didn’t magically become who we are today (like, the day after Barack Obama was elected in 2008). We’d been working on our current incarnation for some time, and it’s a doozy! Politically, we’ve thrown our weight behind an orange-tinted real estate developer from New York City, a couple of culture-war governors, and their trickle-down henchmen in state legislatures. In some ways, I guess it’s no stranger than switching die-hard party affiliation that had lasted for more than a century to embrace an Orange County ex-movie star with a boy-next-door smile. In other ways, I would hope that we’d be slamming on the collective brakes and gasping, Wait—what have we done? I’m straying off my main message, but I am actually trying to make a point: if Southerners understood our own past better, we might not make so many bad choices in the present.

Sadly, Tony Horwitz left us in May 2019, at the age of 60, but before he died, he contributed one more book on our region: Spying on the South. In that one, he followed the path that Frederick Law Olmsted once wandered. If I manage to convince a few folks to read one book, I may as well throw down the gauntlet and suggest reading two. But if even one is too much to ask . . . I’ll say this: the next time you feel like, Things sure are crazy these days, just remember that they have been for quite some time.

October 12, 2024

A Deep Southern Throwback Thursday: The WAPX Shootout, 1974

It was fifty years ago today, on October 12, 1974, that a small group of black militants barricaded themselves in the downtown office of a Montgomery, Alabama radio station and had a shootout with police, who had surrounded the business. The event became known as the WAPX Shootout.

The situation on that Saturday morning began on the Wednesday prior. Three “self-declared revolutionary young black men” were wanted in connection with the robbery of a Delchamp’s grocery store on Court Street. A 24-year-old assistant manager was killed by a group of men wearing ski masks. Local news reported that he was “shot in the face with a shotgun for no apparent reason.” The robbers got about $200 from the store.

Accounts from eyewitnesses who were downtown on that Saturday morning begin with a bullet-riddled car that was being chased by police. The car, a white Chevy with Autauga County plates, crashed near the intersection of Dexter and Lawrence, and the men in it fled on foot. Their heads were shaved, and they were wearing what was described as “Muslim-type robes.” Reports from later in the day said the group that they belonged to was called the Black Dragon of Kung Fu. In their car were found “black supremist literature” and raffle tickets for a fundraiser.

The violence continued as the men ran from police. Forcing their way into the radio station, they shot and killed an elderly retired policeman, slashed another man across the face with machete, and shot a young woman. The station owner’s teenage son was taken hostage briefly.

As it escalated, the scene was chaotic. An estimated two hundred law enforcement officers, from every branch and office imaginable, showed up and surrounded the area. Inside the station, the militants began broadcasting messages to the black community in Montgomery, urging them to rise up en masse. According to the Alabama Journal, what was said was this: “So come and get one. [ . . . ] I’m going to get mine. There’s a Negro revolution and a black revolution. I’m in the black revolution. We want all you n****rs to come down. We want 5,000 down here in a few minutes. [ . . . ] Y’all ain’t never seen anything like this in Montgomery, have you? This is real, baby, right here in the state capital [sic]. We will revolt or die doing this for blacks.” Soon after these broadcasts, the electricity to the business was turned off.

Within about an hour’s time, the robbers-turned-instigators found themselves trapped. Their calls for action went unheeded, and there was no way to continue to reach out. In addition to the bullets and shotgun blasts, the police fired tear gas into the radio station and also into the Ideal Cafe next door. After a standoff that lasted about two hours, three men surrendered and were taken into custody. Two others surrendered in the days that followed.

In the days following the shootout, stories about the events abounded. The early coverage said that the cause or reason for the violent spree was unknown. Among the anecdotes, there seemed to be some confusion about how many men were involved; it was initially believed that as many as six had fled the car crash. Three had gone into WAPX, while others had sought different routes to get away. News coverage described the men as a “splinter group of the Muslim organization recognized in Montgomery.” Police Chief Ed Wright, who had taken some shotgun pellets in the hand during the shootout, met with the leader of the group the young men had belonged to. Though he did not tell the press what transpired, he did say that the meeting was productive. Ultimately, there were indictments in November, and convictions followed.

Writing in 2023, Alabama State University historian Howard Robinson summarized the outcome: “The WAPX shootout capped a three-day crime spree and led to life sentences for Arthur Willie Lewis, Julius Davis and Reginald Robinson. The episode also prompted the development of a SWAT unit in Montgomery, hastened the decline of Montgomery’s downtown shopping district, and fed into the rising call for law and order.”

Reminiscent of the scenarios portrayed in the blaxploitation films of the 1970s, the WAPX shootout is an unusual episode in city and state history. Where the Montgomery Improvement Association had been organized and nonviolent for the 1955 bus boycott, the Black Dragons of Kung Fu were clearly neither. Likewise, where the marchers from Selma to Montgomery garnered first sympathy then protection, these revolutionaries found themselves in the opposite situation. In the post-Civil Rights South, times were changing, and the 1970s were a more violent time.

Read More: A 2018 post on the WAPX shootout, from the Times Gone By page on Facebook

October 1, 2024

Southern Movie 71: “The Beast Within” (1982)

Although the classic horror film The Beast Within is best known for the ghastly (and hokey) transformation scene near the end, its setting in rural Mississippi is an integral part of its story. Though the small town of Nioba is fictional, it represents the American idea of a Southern small town, considering that the film’s director was born in Paris and raised in Australia and that its writer was from Poughkeepsie, New York. It is possible that the town’s name is a twist on Neshoba County, which was where Civil Rights workers Goodman, Cheney, and Schwerner were killed in 1964, the year of the film’s opening scenes. (That year also saw the release of Two Thousand Maniacs! and Black Like Me, both films about the vicious behavior of Southerners.) The movie combines sexual intrigue and the small-town South with a heavy dose of twisted weirdness and the classic question about GenXers: what in the hell is wrong with my child?

The Beast Within opens at night, and we see a nice-looking blonde woman in a 1960s-style pink suit come out of a shady-looking gas station. She is prim and proper, stepping lightly and wearing white gloves. This couple and the gas station attendant are the only ones around, and the attendant doesn’t look particularly nice or helpful. She goes to the car, where a man is kicking the tires, and she tells him, map in hand, that their destination is not much farther. JUST MARRIED is scrawled in white shoe polish across their back window, so we understand that they’re newlyweds on their honeymoon. As they drive away, the words NIOBA, MISSISSIPPI, 1964 come across the screen.

The next scene is pretty vague, but we’re meant to understand that something ominous is happening. First, there is an old rundown house in the dark, then we see a chain being tugged, which is accompanied by animalistic grunting sounds. The camera pans around a dilapidated place, maybe a basement, since the floor is dirt. Then we’re outside, in the woods in the winter. The camera moves slowly among the bare trees. We are supposed to understand that whoever or whatever was in the house, tugging on the chain, has gotten out.

Then we move back to our newlyweds. They’re going down a lonely road, smiling and kissing, but then they pass the sign for their destination. The gas station man told them to turn before the sign, so the husband (Ronny Cox) tries to make a U-turn. That hub cap he was kicking comes flying off, and since this is only a two-lane, the car goes off the road and gets stuck in the mud. With no one and no place in sight, he tells his pretty young wife to stay put, and he will walk back to the station to get help. It’s the 1960s, so she does what her husband tells her to do. Sort of. He also tells her to lock the car doors and stay inside, but she doesn’t.

Meanwhile, we’ve seen that thing creeping through the woods toward the headlights. We see only legs, which are human-like, and covered in leaves or something. The dog in the car starts barking, and the lady lets it out to go look, then she herself gets out. A short walk into the woods, she finds that the dog has been killed, then she screams as she meets this creature. We don’t actually see it, but she does. The young bride runs through the woods but knocks herself out on a tree branch. The creature then uses the opportunity to take off her clothes and rape her. All we see of him is a hand, ripping her shirt open, that appears to be kind of hairy but possibly scaly. It leaves when the tow truck arrives. After a brief search, her husband finds her, scoops her up, and takes her away in the tow truck.

Ten minutes into the movie, the backstory is done, and the main story moves forward in the then-present day: 1981. The words JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI 17 YEARS LATER appear onscreen. The husband Eli MacCleary and his wife Caroline MacCleary are sitting in a doctor’s office, talking about their son Michael. The doctor is explaining that Michael has an “occult malignancy” that is causing strange things to happen in his body, and he suspects that the pituitary gland is involved. They’ve tested both parents for genetic abnormalities, but they’ve found none. At this point, Eli begins to shake his head, then he storms out of the office. Caroline follows him into the hall and urges him to accept it: she was attacked seventeen years ago and denying it now won’t help. Eli insists though, No, he’s my son! Mine! Though Caroline agrees, she reminds him that Michael is dying and something must be done.

Next, we meet Michael. He is being rolled into a hospital room and appears to be asleep. He is sweating, and soon we see that he is dreaming. In that dream, he sees a floor hatch in an old house that is being pushed open from underneath; he walks to it and opens it, then whatever is down there makes him scream and fall. Michael then wakes up, and his mother is there. He tells her that he is scared, that he is dying, and she soothes him.

In the light of day, Eli and Caroline are in their station wagon, which is rolling slowly into Nioba. The small town is foggy and gray in the middle of winter. A few people are here and there, but the town square, complete with white-columned courthouse, is mostly empty. They park the car and split up. Eli heads to the courthouse, while Caroline goes to the local newspaper office. In the courthouse, Eli finds the local judge (who wears a really bad wig) to be faux-friendly; he claims to know nothing about any assaults seventeen years ago. Caroline finds a particularly unfriendly newspaper editor, who lets her sift through the archives despite giving her a short time frame to do so. It is lunchtime, he tells her. Among the boxes of old issues, she finds a headline about the murder of a man named Lionel Curwin. She tears off the front page, folds it, and puts it in to her pocket.

Out in the town square, she shows Eli the headline, but they don’t know they’re being watched by the judge. The grouchy editor finds what she has done and hurries over to the judge’s office. They watch the couple walk across the square, and the two locals conspire to ensure that no one talks to them.

The MacCleary’s walk over to the sheriff’s office, but they find that the man who was sheriff in 1964 has retired in 1965 and died in 1969. The new sheriff named Pool was his deputy back then and agrees to answer their questions. Caroline lies to the sheriff like she did to the newspaper editor, claiming once again to be working on a book about crime in small-town America. He tells them that Lionel Curwin was a “real son of a bitch.” People were glad he was dead, but they did not wish for what happened him. Curwin was killed and ripped to pieces, then his house was burned down. The latter fact was how they knew that it wasn’t done by an animal. He also tells them that no similar crimes occurred since and that the town has been quiet. The couples leaves, mildly satisfied.

Back in town, the doctor at the hospital realizes that Michael is gone, missing! He is driving a car – presumably stolen – through the night, and across the screen the words THE FIRST NIGHT mark our place in the story. He runs off the road for no seeming reason, then walks up to the old house that we saw in the beginning of the movie. Inside the doorway, Michael goes to the floor hatch from his dream and asks someone down there if they are asleep. A vague, deep voice answers but we cannot understand it. Michael is going to open the door, but he insists, You have to promise me. We don’t know, promise what? But the vague voice responds, I promise. He then opens the latch and descends into the basement with a match to light his way. He hears the same growling/snoring sounds and says into the dark, “I know who you are.”

We don’t see what Michael finds, but the scene cuts to him walking up to a different house, this one with lights on inside. He goes to the door, and it is the home of the newspaper editor. The older man is in his kitchen, wearing a tank top undershirt with nasty stains on it. He is talking on the phone and, for some reason, puts out his cigarette in his glass of whiskey. Michael is then mistaken for the grocery boy, who has apparently dropped the box and the bill and left. He comes into the kitchen, and stands stoically while the old editor plays with a package of ground beef joyfully but also flirtatiously in a homoerotic kind of way. (This scene is very— no, extremely uncomfortable to watch.) When Michael finally flips out, he throws the editor on the floor and chews his neck open while that cherished ground beef squishes between the victim’s toes. Michael finishes with blood dripping from his mouth.

Nearby at another house, a pretty young woman is cutting up leftovers for her dog’s dinner, while the dog has Michael pinned up against the outside of the house. When she walks outside and finds Michael, he passes out on the ground. Next we see him, Sheriff Pool, Eli and Caroline, and the town doctor named Schoonmaker have him lying in a simple bed. Caroline comments that he looks better than he has recently, and Schoonmaker says that he mainly needs sleep.

Outside in the daylight, the judge – whose name is Curwin, like Lionel Curwin – goes over to talk to Dexter, the town’s mortician. He is looking across the street at the newspaper office and comments to the judge that the office isn’t open. It’s after 10:00 AM. “That hasn’t happened since the night Lionel’s house was torched,” Dexter says. In a moment, we see the Judge Curwin entering the editor’s home and finding him bloody on the floor.

When Michael wakes up, he is smiling and amiable. He wants to go thank the young woman from the night before, Amanda Platt. He goes to her house, and they go walk in the woods. He tries like a teenage boy would to seduce her, then asks whether her father is Horce Platt, Lionel Curwin’s cousin. The girl is perplexed at the strange question, yet Michael collapses into a some kind of episode before the conversation can continue. He has some sort of flashback to that floor hatch, then he uses his position on the ground to start making out with Amanda. But . . . the romance is over when her dog runs up with a decomposing human hand that he has found.

Law enforcement has arrived, and everyone is standing around when Horace Platt pulls up in a yellow power company truck. He grabs Amanda harshly and tells Michael to stay away from her. Eli asks if Horace is always so brusque, and Sheriff Pool shares that he killed his wife and the man she was cheating with. Eli inquires why he wasn’t put in prison for the murders. Sheriff Pool responds with a smirk that he’s the judge’s cousin. Michael knows that Horace will hurt is daughter, but his parents assure him that he probably won’t. Eli then stays behind to look around at the law enforcement work. Mother and son leave.

On THE SECOND NIGHT, the good guys discover that there are a whole bunch of corpses! They get more man power, and the skeletons are laid out on the ground, under sheets. The doc is called out to look at the remains, and he recognizes one leg bone with a stainless steel knee replacement that he did. This revelation leads them to question Dexter down at the morgue. As Eli, the sheriff, and the doc walk in, the doc remembers that Dexter wasn’t the coroner back in day— Lionel Curwin was. Dexter is inside, creepy as he can be, getting the dead editor ready for his funeral. He doesn’t like Eli’s presence and won’t answer questions.

Across town, Michael is lying in bed, writhing and shaking. At this, the halfway point, The Beast Within begins to get stranger. There’s a drunk sitting by an abandoned building, pulling from a whiskey bottle, and talking to himself. Michael arrives in the dark and begins speaking to him, calling him by name. The drunkard, Tom, tries to ignore him, but as Michael continues to talk, Tom realizes that his body is possessed by Billy Collins. We don’t yet know who that is, but Tom intimates through his drunken rambling that they were friends. But what is important is a little clue that Tom gives: a vague allusion to locusts and cicadas that go away for a long time then come back to life.

Then, over in the morgue, Dexter is on the phone telling the judge that he has stayed quiet for seventeen years, that he wants money, and that he’s out. But he won’t get that far. He hears a knocks in the dark, then returns to his work. Michael/Billy rises up from one of the steel tables and stabs Dexter to death with one of his tools. The good guys are in graveyard, digging up a grave to see what is in the casket, when this happens. After discovering a casket full of rocks, they return to find Dexter dead.

As they’re leaving the morgue, Caroline arrives frantic. Michael is missing again. Maybe he’s at Amanda’s.

Yep, that’s where he is. First, he is creeping outside, watching through her window as she sleeps. Then he goes all the way inside, into her room. He picks up a heavy glass paperweight and is lifting it over his head to smash her with it, when Eli and the others come banging on the door. At first, a shirtless Horace tells them to go away, but when Amanda screams, they run into her room. A tussle ensues, and Michael claims that he is there to protect the girl from the murderer. No one believes him. After the crowd leaves, Horace slaps his daughter then gives her a big nasty hug, pressing her face into his hairy chest. Outside, Caroline wants to know what he was really doing in there, but he just looks drowsy and doesn’t answer.

Back at the hospital, Doctor Schoonmaker, who is now wearing a Colonel Sanders-style string tie, looks at some chest X-rays of Michael. Under the skin, there is a an appendage or something that runs the full length of his torso. He doesn’t know what it could be. In the room, Eli tells Michael that they can leave, but Michael resists. He defies his father and remarks that Eli isn’t even his father, that Billy Connors is his father. His parents are shocked and distraught. They know the facts, of course, but Michael shouldn’t, and they sure didn’t know the rapist’s name! Caroline tries to console Eli in the hall.

Over in the jail, the judge wants to know where Dexter is – certainly it’s about that phone call the night before – and Sheriff Pool tells him that Dexter is dead. They don’t know who killed him, though. After the judge leaves, Tom, who was in the drunk tank eavesdropping, comes out to tell the sheriff that the killer was Billy Connors but in the body of Michael MacCleary. Sheriff Pool gives him a dollar and tells him to go get some breakfast.

Michael’s transformation into Billy has begun. He has a large wound on his back between his shoulders and, in the bathroom, he declares to no one, You promised! Soon, the doctor comes in, sees the bandage that Michael has put on his own wound, and wants to see. Michael attacks him, throwing him against the wall. Outside, Eli and Caroline are confronted by Tom, who wants them to believe that Michael is now Billy. Eli throws him against the car and tells him to stay away from them. So Tom runs through the swamp and to the local power plant, where he and Billy used to hang out as young dudes. And there’s Michael/Billy. Tom tries to escape but a now-nasty-looking Michael throws into the electrical works, frying him in a shower of sparks.

While the local lawmen try to figure out why the power went out, Eli and Caroline ask the doctor about Billy Collins. The doctor says he was strange but handsome and graceful. People said that he could talk to animals, which explains Tom’s drunken statement about Billy and the cicadas. But before long, the sheriff arrives to tell them that Tom is dead. He wants to talk to Michael. And . . .

Now, we’re on THE THIRD NIGHT. Michael has gone to Amanda’s house to warn her to leave. She’s a Curwin and will be among those the killer will target. He can’t explain how he knows that but assures her that she does. Because she is hesitant to go, Michael gets forceful and causes Amanda cut her finger with a kitchen knife. But against Michael’s wishes, the drips of blood that she leaves behind excite the Billy in him, and he goes upstairs to attack her. The scuffle ends in Michael throwing himself off the second floor landing to keep himself from harming the girl he likes.

Now, The Beast Within is coming to a close. Michael tries to explain to them about Billy inhabiting his body, but their answer is to strap him down. At this point, every character is up in arms. Horace wants blood since Michael won’t stay away from his daughter, and the judge is supportive of his cousin’s violent tendencies. They arrive to kill Michael while he is in that gory transformation, but the shotgun blasts don’t kill the creature. Michael is no longer, and the thing he is becoming is on its way. After a few violent incidents, the mayor – now bald, without the wig – arrives at the sheriff’s office, seeking protection from the creature. Eli knows that he knows what is happening and demands answers.

The mayor explains that his brother Lionel Curwin found Billy Connors in bed with his wife. Instead of killing Billy, Lionel locked Billy in the cellar and nearly starved him to death, before deciding to feed him meat from human corpses. Lionel was the town’s undertaker so he could get away with it. The ordeal turned Billy into the monster that attacked Caroline. Knowing how it must look that he has protected his brother’s grotesque secret, the mayor tries to deny culpability, but Michael/Billy the locust creature arrives anyway. They are all afraid, and the mayor is locked in a jail cell for protection. Ultimately, the creature gets away from them as they stalk it outside the jail. Unfortunately for her, it leaves the jail area and finds Amanda, who is stranded by the roadside. He rapes her in the woods, just as Billy did Caroline . . . and the cycle will start all over again.

If you’re still reading, consider showing some love!Since it is set partially in Jackson, Mississippi, it seems appropriate to look first at the Clarion-Ledger‘s review of the film back in ’82. Unfortunately, Southern Style writer Bill Nichols had very little good to say about The Beast Within. Lumping it in with other bad horror movies that rely not on the classic “danse macabre” but on baser human instincts, Nichols wrote, on February 12, 1982: “It is the power and grand tradition of horror fiction and film that makes a movie like The Beast Within particularly sad. [ . . . ] It’s truly a monstrous film, sadly representative of exploitative horror movies producers like to pander on a movie public they believe too insensitive to want anything more.” He also quips sardonically that “Caroline is raped by something that looks like a cross between the creature from the black logoon [sic] and Charley the Tuna.” However, he does note the film’s “lone point of interest” as its “striking photography of the Mississippi countryside.” In a review that ran a week later in the Biloxi Sun, their critic’s assessment was not much better: “Along with being disgusting, the film is poorly acted and directed,” wrote critic Paul Drummond. At the end of that review, he noted that, aside from seeing some locals in the film, “being filmed in Mississippi doesn’t help The Beast Within, though.”

I take the reviewers’ points. But bad horror movies are worth watching because they traffic in easily recognizable “types,” which makes us ask ourselves why we recognize and believe in these “types.” Horror films that explore deep human mysteries in nuanced ways require our thought and attention, and are valuable art for those reasons. Cheap, bad horror movies have to reel us in quickly with unexamined cultural beliefs that are already ingrained. This is easily done when Southern culture is involved. For example, everyone agrees that hitchhikers and car trouble on an isolated country road are both scary, which makes Texas Chainsaw Massacre frightening. Or that Louisiana’s swamps are scary, which underpins Hatchet. For The Beast Within, we agree that rural Mississippi is scary— so scary that . . . what if your dad’s car broke down and he left your mom with the car and went to get help, and then a creature came out of the woods and raped your mom, then it disappeared into the woods, and later when you turn 17, your true nature as a monster comes out of you? This film’s premise is absurd, so to participate in its story, a viewer would have to agree that this occurrence is actually possible in a place as strange as rural Mississippi.

As a document of the South, The Beast Within works with those “types” in a small Southern town. Anyone who has any power in this small town – the judge, the newspaper editor, the mortician – is a twisted person and is in cahoots to cover up a stain from the town’s past. Two outsiders arrive to cause problems – to uncover the truth – which threatens the façade of a peaceful town that is not actually peaceful. This scenario should seem reminiscent of Civil Rights violence, where the crimes of the locals are swept under the rug, only to be revealed by outsiders who come meddling in local affairs. Here, we have a different situation but still in that familiar framework. The South’s secrets are hidden in the woods or in structures that burned: murders, lynchings, torture, sexual crimes . . . All things that are better left well enough alone. Seemingly normal townspeople turn out not to be what they seemed. What we learn from stories like this one is that small-town Southerners are sick, twisted people whose sense of justice is warped, often by beliefs about family and by xenophobia. We are left ask ourselves: is the “beast within” the thing that came out of Michael, or is the “beast within” the secret that was held inside of the townspeople?

(Though it is not related to the Southern-ness of the film, one of the bizarre aspects of this movie is how male-centered it is. Other than some extras in the background and a brief appearance from one court clerk, there are only two female characters. Both end up being rape victims and surrogate mothers for a humanoid creature. The judge has no wife, neither does the newspaper editor, nor does Dexter the undertaker. We also hear that two different men murdered their cheating wives yet were not charged with any crimes. Certainly, these two male cuckold-murderers were related to the judge, but didn’t their wives have families who demanded justice? Likewise, after Caroline’s rape, the film shows no concern for her ordeal; what we do see are Eli’s emotional struggles over Michael not being his son. Caroline, the rape victim who carried the resulting child then raised him, is left to soothe her husband through his denial. In the end, there is equally little concern for Amanda as a rape victim. They’re just glad the monster is dead, so they’re “safe.”)

September 25, 2024

Sharing the Good Stuff: A Hopeful Take on Climate Action, on PBS News Hour

This author, who was raised in south Florida, gave a nice talk tonight not only about her book, but about two important notions: one, that we already have knowledge and methods to combat climate change, and two, that we all play a role in our way.

Read more: Shut Up, Doomsayers! • Passive Activist 8: Compost

September 19, 2024

Reading: “The Shadow of a Great Rock” by Harold Bloom

The Shadow of a Great Rock:

A Literary Appreciation of the King James Bible

by Harold Bloom

My rating: 5 out of 5 stars

Back when I was an English major in the 1990s, Harold Bloom was the guy. His Bloom’s Literature criticism collections were the go-to reference books, alongside the CLC and TCLC volumes, and though we knew little about the man himself, we relied heavily upon him. His name hovered in the air of our department in the same way that those of his forerunners FR Leavis and Northrop Frye did. I didn’t read Bloom’s 1994 book The Western Canon until after college, then I skipped 2001’s How to Read and Why and went straight to The Daemon Knows when it came out in 2015. I used to use his “Introduction” to The Western Canon in my twelfth-grade English classes to help students understand why some literature is “great.” Let’s just say I’m a fan.

So reading The Shadow of a Great Rock was a pleasure, since Bloom is one of my favorite critics and since the King James Bible is the translation I prefer. (I am Catholic, but the Church’s New American translation can be a little . . . starchy.) I got my best introduction to reading the Bible in Dr. Frank Buckner’s freshman religion classes at the Methodist-affiliated Huntingdon College, and my first Biblical love was the KJV’s Ecclesiastes, whose imagery and poetry are vivid and beautiful. To read Bloom discussing the King James Bible is a double bonus.

For a Christian whose familiarity with the Bible is better than average, Bloom’s “Literary Appreciation” is enlightening, though sometimes uncomfortable to read. Examining the figures not by their connections or roles to sacred tradition but by their characteristics and actions, we get a different view of these ancient men and women. And the critic spares no expense. The targets for his criticisms include Yahweh Himself, Isaiah, and Paul. He points out the strange and inconsistent behavior in the Old Testament and the baffling admonitions in the New. We see how Yahweh, in the early days, placed himself among His people, sometimes in the form of natural phenomena and sometimes even walking among them. Bloom gives a brief but wonderful commentary on the verses in Exodus 24, in which God was sitting with Moses, Aaron, and others while they ate on Mount Sinai. In Bloom’s analysis, we also see Jacob limping around and Esther facilitating revenge. We find thoughtful remarks on the differences between Isaiah, Ezekiel, and Jeremiah. And, in the midst of it all, he finds room for his characteristically wry sense of humor: writing about Psalm 126, which “I take particular delight in,” he tell us, “If you are sleepless, then Yahweh does not love you.”

Acknowledging quite often throughout the book that regarding these figures and these stories as sacred makes it hard to view them as people or as characters, Bloom also shows us where he believes our English-language translators were off-base. It can be a little tedious to read the same passages more than once, which one has to do in this book, but here we find the KJV’s text alongside the earlier translations by Wycliffe and Tyndall. There are also piecemeal notes about the meanings of words in the original Tanakh, where Bloom walks us briefly through nuances in verbiage that he sees as missed opportunities. He doesn’t like the translators’ misrepresentation of Joseph’s “coat of many colors,” which he tell us was actually a specific type of royal garment. In Job, he laments that the “ha-satan” has been equated to Lucifer/Satan but would have instead been either a “blocking agent” or some kind of prosecutor for God.

Harold Bloom’s knowledge and intelligence are notable to me as a life-long reader and long-time writer. The man was extremely insistent on examining and assessing texts with unrelenting levels of scrutiny. Yet, by the 1990s, as multiculturalist and critical theories were challenging established notions, Bloom’s hard-line attitudes made him an easy target. (Mainly since he stood in the wide open and criticized his detractors smugly in return.) It would be wrongheaded to consider the old critic as a relic of now-dead past, because his main point in battling back against critical theories was that, for literature to be called great, it has to be great. Responding to calls for wider inclusion, he responded, Only if they’re as good as the writers you’ll be placing them next to. In that, I agree entirely, while counting myself among the literary practitioner-thinkers who want greater diversity in our American canon. And it’s in that spirit that I read The Shadow of a Great Rock. We should want to embrace the greatness of our Bible, our religion, and our tradition, and we should want to understand that greatness for what it is and what it includes. Bloom’s book is one (among many) that can remind us about the original texts and the cultures that produced them. In our everyday concerns over “faith and works,” what shouldn’t be neglected is intellectual work— the inconvenient and often arduous tasks of reading and studying with an open mind, done not with an intention to tear down the religion by exposing flaws and misconceptions, but to get closer to it by understanding what has changed over thousands of years and multiple translations.

Note: In the book, Bloom uses the abbreviation KJB for King James Bible. Here, I use the abbreviation that is more familiar to me: KJV for King James Version.

August 29, 2024

Dirty Boots: Backstories

Generation-Xers in the South were born into a society that was in flux, but the fact of this and the reasons for it were rarely revealed to us at the time. The oldest among us were born in 1965, the year of the Selma-to-Montgomery March, and that group of children started school in 1970 or 1971, at the time of the Swann ruling. In the 1970s and ’80s, we grew up during a period of cultural and political change among older generations who knew the context and who had lived then-recent history. Whether we were too young to know or kept in the dark on purpose, the end result was the same: a lack of awareness, a lack of context, a lack of comprehension. Continuing to live in Alabama as an adult, I have learned that the generations who raised us were reticent and unsure, sometimes bitter, usually skeptical, but often hopeful about a new way of living as they tried to grasp it themselves. It makes a man my age interested to know more about that old world, the one that was dying out as I came into being.

Generation-Xers in the South were born into a society that was in flux, but the fact of this and the reasons for it were rarely revealed to us at the time. The oldest among us were born in 1965, the year of the Selma-to-Montgomery March, and that group of children started school in 1970 or 1971, at the time of the Swann ruling. In the 1970s and ’80s, we grew up during a period of cultural and political change among older generations who knew the context and who had lived then-recent history. Whether we were too young to know or kept in the dark on purpose, the end result was the same: a lack of awareness, a lack of context, a lack of comprehension. Continuing to live in Alabama as an adult, I have learned that the generations who raised us were reticent and unsure, sometimes bitter, usually skeptical, but often hopeful about a new way of living as they tried to grasp it themselves. It makes a man my age interested to know more about that old world, the one that was dying out as I came into being.

One interesting set of facts about modern Alabama’s backstory comes from William Havard’s 1972 collection The Changing Politics of the South. In the chapter “Alabama: Transition and Alienation,” historian Donald S. Strong wrote, “It is doubtful that Alabama can fairly be called an agricultural state, since only 5.8 percent of the income of its people came from agriculture.” In that passage, Strong was writing about the 1950s and alluded to the trend of urbanization that reduced the state’s rural population by 14.3% in that decade alone. The national average for that trend at that time was a 0.8% reduction, but Alabamians were moving into cities at a rate almost eighteen times higher. Strong was elucidating a significant shift in our culture, which occurred right before GenX came along.

I have heard for my entire life in Alabama that agriculture is and has always been paramount (the elevated status of college football notwithstanding, of course). Many generations of my family have lived and worked on farms in Alabama, from the first arrivals in the 1850s until my maternal grandparents moved to Montgomery permanently in the 1950s. My grandparents were among the people Strong was describing, those who formed the exodus that Jack Temple Kirby discussed in Rural Worlds Lost. By the time I was born, in the mid-1970s, the primacy of farming was no longer a fact of life here. It seems that I and other kids were receiving a myth about a bygone time, one newly handed down across generations.

Why does that matter to me, growing up then and living here today? Because the Democrats of the early to mid-twentieth century were not just the party of segregation; they were also the party of rural people and values, of small towns and farmers. Their “base” was in the countryside, so they governed with a conservative outlook that focused on slowly improving quality of life and public services. That approach served poor white voters in outlying areas well; the ugly side was that those improvements rarely came to black communities. Urbanization then opened the doors for the modern Republican Party in the South. Strong wrote that, even though the Republicans did have some party infrastructure in Alabama, “it was only in 1963 that a permanent professional staff was established in the state headquarters and a serious effort made to develop an active committee in every county.” By contrast to their Democratic counterparts, Republicans in the South in the 1970s and ’80s offered a new brand of conservatism that appealed to people whose quality of life was noticeably better. By emphasizing low rates of taxation, traditional values, and policies that allowed privatization when public services and accommodations became undesirable, the GOP’s vision and platform was viable among people who had moved into cities and suburbs. The mass shift in population laid the groundwork for the suburban politics of a post-Civil Rights South at the end of the twentieth century.

(This explanation doesn’t extend into the twenty-first century. First, there has since been another flip-flop whereby Democrats have become the party of the cities and Republicans the party of rural people. That’s a-whole-nother story. Second, with respect to farming, the Alabama Farmers Federation reported in February 2024 that there are 62,777 farmers in Alabama, a state with five million people. Of course, that figure doesn’t include the people who work in the agriculture industry: feed stores, processing plants, trucking, brokers, etc. Yet, it’s fair to say that there are still millions of Alabamians living in rural areas, but very few of them are actual farmers.)

Looking even further back, another interesting aspect of that backstory to consider about Generation X’s upbringing – this also from Strong’s chapter – is that Alabama’s population was 47.5% black in 1870 but that had dropped to 32% by 1950. By the 2020s, the proportion has become 25–26%. Much focus today is put on the racism involved in slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow, but the practical reality of outmigration has played a role, too. This long-term trend/movement reduced Alabama’s black population from one-half to one-third between 1870 and 1950, which affected the economy, the society, and the politics. Granted, some of this net loss in population could be attributed mechanization, which meant fewer farming jobs for black and white laborers, leading many families to move in search of work. Some of those folks went into Southern town and cities – see above – and some left the region for the North or the West. But one has to know, mechanization or not, that a whole bunch of black Alabamians looked around between 1870 and 1950, and left.

Why does that matter to me, a middle-aged GenXer? Because Alabama would be a different place if the statewide black-white racial balance had remained almost fifty-fifty throughout the twentieth century. I can’t even imagine how the politics of that would have played out over fifteen decades . . .

I don’t think about these things like a history buff, but as a person who wonders about life as we’re living it now. Knowing about history is one thing, considering how it has affected us personally is another. As an example of the past affecting the present and future, in the 1990s, Alabama’s congressional map was redrawn to create one black-majority district, District 7. The Democratic Party of the 1970s and ’80s had not created enough viable political opportunities for black candidates, instead sprinkling black voters into multiple districts to bolster the vote totals of their moderate white candidates. So support was garnered, and a black majority district was created. Today, District 7 has Alabama’s only black House member and its only House Democrat. About thirty years after that, a 2023 Supreme Court ruling led to the creation of a second district with a near-majority of black voters. Next year, there could be a second black Democrat, in the newly aligned District 2. This development could alter the racial proportions in our House delegation to be more representative of our population: 28% of our delegation will be or could be black, which nearly parallels a 26% black population in the state.

Why have those moves been necessary? The lack of a two-party system with biracial politics that listens to all voices. Even though we had a period of greater balance in the late twentieth century, it dissolved rather than becoming entrenched. Today, in Alabama’s State House, the Republicans have supermajorities with virtually the same ratio in both bodies. In the 105-seat House, all of the leadership positions are held by white Republicans, with seventy-six Republican members, all white, and twenty-eight Democrats, twenty-five black and three white. (There is one vacant seat right now.) In the Senate’s thirty-five seats, we have twenty-seven white Republicans, and eight Democrats, seven of whom are black and one white. Alabama’s population is 74% white, its state-level House is 76% white, its state-level Senate is 80% white, its US House representatives are right now 86% white . . . and of Alabama’s statewide offices – governor, lieutenant governor, supreme court, US Senate – 100% are white and 0% are Democratic. That scenario is neither two-party nor biracial. Once again, I wonder what those numbers would be, if Alabama had remained 47.5% black from the end of the Civil War until today.

People often wonder about Alabama’s current politics, how did we get here? If more of our forebears had talked to us, if we were taught our own history in school, more people might know the answers. Some of the answers that we are seeking lie in backstories, such as the ones that Donald S. Strong was telling to an audience of academic historians in 1972. Between the end of slavery and the end of World War II, many black people left Alabama. When the population changed, the workforce changed, and the electorate changed. By the end of World War II, mechanization had permanently altered the nature of small-scale farming, and many black and white people looked for work elsewhere. The politics of rural people became less relevant, when the population shifted. The Republican Party became established with infrastructure and a relevant platform, and post-Civil Rights Democrats tried to counter with a platform that ended up being unpalatable to the white majority and unacceptable to the black minority. Those socio-cultural changes created the situation that we have today. We might actually have a two-party system that values biracial cooperation and the good of all.

August 17, 2024

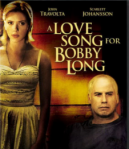

Southern Movie 70: “A Love Song for Bobby Long” (2004)

Based on the novel Off Magazine Street by Ronald Everett Capps, A Love Song for Bobby Long tells the story of a young woman who comes to New Orleans to garner whatever inheritance that her estranged mother may have left her. But what she finds are two degenerate alcoholics who still live in her late mother’s house. Rather than leave the dingy home, the two interlopers use their knowledge of the literary to add flourish and legitimacy to their bad behavior, so this young woman must navigate their strange world in an effort to resolve her mother’s affairs. Through this ordeal, she finds out a little more about humanity and the ways that people cope with their suffering. Directed by Shainee Gabel and starring John Travolta and Scarlet Johansson, the film takes us through a handful of often-sad lives in the seedier parts of New Orleans, and though it does stray from the novel by eliminating some of the more disturbing elements, the humanity in this story still shines through.

A Love Song for Bobby Long opens in a dark barroom where we see man in profile. This is Bobby Long. He is smoking and soon leaves with a bottle in a paper sack. Dressed in a linen suit and a straw hat, and wearing one dress shoe and one flip-flop to accommodate his black big toe, the man limps to the barroom door and opens it to reveal bright sunshine. As a bluesy tune plays, we see him walk through many parts of New Orleans, eventually finishing the bottle and setting it down. Eventually, he arrives at a funeral, sparsely attended, where a voiceover tells us that someone named Lorraine is dead. After the funeral, he is in a raggedy old car with a young man, and they pull up to The Rock Bottom Lounge, where an even more disheveled Bobby struggles to get out of the car. The younger man, who was driving, moves quickly and goes in ahead of him.

Next, our focus shifts to Panama City, Florida, where Lorraine’s daughter Pursy is sitting on the couch in a trailer amid trash, clothes, and a dirt bike. Her scruffy redneck boyfriend Lee comes in, and she asks him whether he has found a job yet. During this conversation, he remarks that that guy Bobby called again. He hadn’t told her that Bobby called the first time— to say that her mother died. Pursy is furious, but Lee wants to ignore Lorraine’s death and go on with life as usual. Pursy storms out with a bag of clothes, ostensibly heading to find out what is going on.

Amid this scene, we break to Bobby and his young counterpart Lawson, who are doing shots in that dark bar. The pretty bartender, who is Lawson’s girlfriend, asks if they’ve finally been kicked out of Lorraine’s house, but the two don’t see it that way at all. Bobby declares that the house is “ours.” Outside the bar, Bobby tries to call Pursy again to say that she missed the funeral, but he gets no answer. The two men and a third friend Junior agree to meet later, and after a short walk, they arrive at small encampment with a trailer, where their friends have gathered. Their friend Cecil is eat a po boy and crying, while they wonder out loud how long Lorraine was sick. It had been six years, and Cecil coldly reminds Bobby how long it had been since he’d visited her. We learn now that Bobby and Lawson have been squatting in the home of a sick woman, and they never took the time to visit.

Soon, Pursy arrives in a cab, and we see her trying to find the house. The small house has a wraparound front porch and is badly in need of paint and repairs. It is an eyesore at the end of the street, with weedy lots beyond it. She bangs on the door, Lawson answers, but at first he doesn’t give her a straight answer about who he is. She comes inside anyway, and the place is sparsely furnished, dirty, and dark. Lawson tells her his name and remarks how Pursy looks like her mother. Then he goes to wake Bobby, who is still in bed, by pouring him a screwdriver. Bobby gulps down the drink and mumbles a few things to Pursy about missing the funeral and “the deal with the house.” According to Bobby, Lorraine left it to all three of them, with one-third ownership each. He has no proof of this, of course, and his face and Lawson’s say that he is lying. The conversation is a tense one, but Bobby informs her that, if she stays, they’ll be roommates. He soon gets out of bed, wearing an Auburn t-shirt, which will become relevant later, and moves past Pursy to go out and buy more cigarettes. After he is gone, Lawson tries to give Pursy a suitcase full of old paperbacks, which he explains were important to her mother, but the young woman doesn’t care. Soon, she walks off down the street, carrying all of her bags.

Later, Bobby and Lawson get drunk in the dark and muse about Lorraine, while Pursy sits in a Greyhound bus station reading The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. She finished the tattered paperback in one sitting, looks at the inscription to Lorraine from Bobby, and returns to the old house. When she arrives, Bobby and Lawson are in a diner eating breakfast, and they return to find Pursy is asleep in a lawn chair in the main room. Bobby pulls up a chair and lays down beside her. When she wakes up, there he is, and he banters at her in a way that mixes intimidation with a cheap come-on. Pursy informs them that she’s staying, and Lawson says that he will clear out of Lorraine’s old room for her. Bobby is miffed at the turn of events, and Lawson reminds him that Pursy will probably leave before she “finds out the truth.”

In Lorraine’s old room, Pursy questions the nature of Lawson’s relationship with her and makes some vague comments about her lifestyle. Lawson is speechless, but he tells her that a stack of boxes in the corner were her mom’s, so . . . they’re hers now. He also replies, to her remark about the books all around, that Bobby was an English professor and that he himself is something of a writer. Pursy is surprised. In a moment, wanting for any food in the house occupied by two alcoholics, Pursy then wanders out of the house and encounters Cecil, who knows her from her childhood. He helped to name her, he explains, after a golden-colored rose. Pursy replies that purselina is actually a weed, not a flower, but Cecil grins and doesn’t accept the slight. Down the street, at the Rock Bottom Lounge, Pursy goes in and asks for some red beans and rice and a beer, and the bartender Georgianna becomes one more person who has something to say to Pursy about her late mother.

When Pursy walks home after an unsuccessful job hunt, she sees the fellas all gathered in the little encampment down the hill. Bobby has an acoustic guitar and is singing a song. She comes down the hill, and Lawson introduces her to everyone. There is one woman there, an older black woman who speaks kindly and introduces herself. Other than her, there are eight or ten men, black and white, drinking beers and cutting up. Bobby wants to make Pursy uncomfortable, so he begins to tell a vulgar story about being a boy and wanting to know what pussy is. His tactic works, and Pursy storms away, leaving the others to grin at Bobby’s antics.

Later, Lawson and Bobby talk in the dark, and Lawson tells Bobby that he doesn’t like lying to Pursy. Bobby replies that the house is a “shithole” that she shouldn’t want. Besides, when Lawson sells the book he is supposedly writing, they will move to Paris and lead grand lives. All the while, Bobby is looking at some photos of a woman and three kids. We don’t yet know who they are.

In the scenes that follow, we see these three lives changing. Cecil takes Pursy to the graveyard to see her mother’s grave, and they talk a little about who she was. Pursy is bitter about being abandoned, and the grandmother who raised her in Lorraine’s absence has died. Back at the house, Pursy begins painting and cleaning up. Across the street in the garden-encampment, Bobby grouches around while Pursy settles into the group dynamic. During these conversations, we learn that Pursy dropped out high school after ninth grade, though we don’t know how old she is. This culminates in a somewhat violent argument between Bobby and Pursy, when the young woman harries the old drunk by refuting his ill-tempered condescension then insulting the mother who did not take care of her. Bobby responds to what he perceives as disrespect by making a lurid suggestion that, because she is not so innocent herself, she might consider paying for her cigarettes by taking on two men at once. Pursy then carries her ire toward him all the way, throwing his drink his face, stomping in his bad toe, and alluding to the wife who threw him out and the kids he doesn’t see. Though we still don’t know his whole story yet, Bobby’s response is to get in the old car and drive to Auburn, Alabama to the campus, where he grimaces silently in the car and rubs his brow in frustration.

The scenes that follow are kind of a hodge-podge. After Bobby is gone, Pursy and Lawson sit on the porch and have a heart-to-heart. She tells him that she might like to become an X-ray technician eventually, but we know that a ninth-grade dropout would have a long way to go to that goal. Next, we see Bobby make a call from a pay phone to a home in the middle of the night. A woman’s voice answers but we do not see him speak before it cuts away. Presumably this is his estranged wife. Back in New Orleans, Lawson is reading a letter from a lawyer, which would indicate that legal proceedings to give the house to Pursy are moving along, and when he storms into the house and enters the bathroom without knocking, we get our gratuitous shot of Pursy’s body as she is getting out of the shower. In the kitchen a moment later, Lawson takes to drinking gin with pickle juice, since they’re out of OJ, then he takes Pursy to the Quarter to hunt for a job. This group of scenes closes out with the two of them talking candidly by the riverside, and we sense the romantic tension between them is growing. That tension increases when later at the bar, Georgianna and Lawson are being cozy, which clearly makes both Lawson and Pursy uncomfortable.

Then Bobby comes home. Lawson and Pursy are on the porch painting the exterior of the house like a couple of newlyweds. Bobby is all smiles, but has the bad news that he sold Lawson’s car because he needed money. Lawson is pissed, but Bobby has news to share. They go inside, and he proudly shows them a doctored transcript that would put Pursy in the twelfth grade. She rails against the idea of going back to school, but the older men believe that she should. Later at the bar, they sweet talk her into accepting their proposal. The next morning, they’re on a street car heading for the private school that Bobby has gotten her into. After a kind of strange scene, in which Bobby talks to a young couple then wants to know whether they’re having sex, they exit the street car hastily and Pursy sees her school. It is a long way from the world she lives in.

Then Bobby comes home. Lawson and Pursy are on the porch painting the exterior of the house like a couple of newlyweds. Bobby is all smiles, but has the bad news that he sold Lawson’s car because he needed money. Lawson is pissed, but Bobby has news to share. They go inside, and he proudly shows them a doctored transcript that would put Pursy in the twelfth grade. She rails against the idea of going back to school, but the older men believe that she should. Later at the bar, they sweet talk her into accepting their proposal. The next morning, they’re on a street car heading for the private school that Bobby has gotten her into. After a kind of strange scene, in which Bobby talks to a young couple then wants to know whether they’re having sex, they exit the street car hastily and Pursy sees her school. It is a long way from the world she lives in.

Next we see them, the trio is at home. Bobby is trying to tutor Pursy like an old timey schoolteacher, and she resists like a modern teenager, whining and complaining. He is an unorthodox teacher, and we see a little of what he might have been like. Once this scene is over, Lawson and Bobby are in the kitchen. Lawson is sweating and dour-looking. He is trying to quit drinking, a promise he made Pursy: she said she would try school if he would cut back. Bobby is no help, though, and he encourages Lawson to pour some vodka in his OJ to get over the hump.

The movie is halfway through now, and the story’s conflicts are in place. Pursy has disrupted the two alcoholics’ routine, but she has ingratiated herself too. Pursy is searching for the truth of her mother, and she and Lawson seemed poised for an unlikely love affair. Bobby and Lawson have half-embraced the teenager girl who wandered into her life, and while Lawson seems poised to help her, Bobby’s behavior mixes efforts to better her and to run her off at the same time. We see change happening in front of us, but we aren’t sure how this will end up.

Of course, Pursy tries to quit school, but the offer of a job at the Rock Bottom Lounge on weekends comes contingent with her being in school. A brief voiceover from Lawson tells us that summer turns into fall, and the whole crew seems happy together in their little community. Winter comes though, and times are hard. They have no heat, and Pursy is trying to help them quit drinking so much. Lawson takes the laundry to wash it, then comes back with a Christmas tree that he stole off the top of a Volvo. While he is gone though, Bobby and Pursy have a heart-to-heart about children and their parents. She stabs at him about the fact that he doesn’t see his kids, why she doesn’t know yet and neither do we. He in return wants to know whether she remembers her mother. She doesn’t, she tells him, so she used to make up fake memories to console herself, but in time, let those go. She doesn’t actually know at this point what she remembers because truth and fabrication have blended in her mind.