Foster Dickson's Blog, page 3

May 15, 2025

Southern Movie 77: “WUSA” (1970)

Paul Newman’s films in the 1960s and ’70s are some of the best among classic films: The Hustler, Sweet Bird of Youth, Hud, Cool Hand Luke, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Sometimes a Great Notion, The Sting. But, from the chronological middle of that list, 1970’s WUSA did not become a classic. In fact, it has become hard to find – some even call it “rare” – in the fifty-five years since its release. (Some argue that it is not a very good movie.) The film’s description reads, “A radio station in the Deep South becomes the focal point of a right-wing conspiracy,” and Newman plays Rheinhardt, a DJ at that station. Directed by Stuart Rosenberg, who also directed 1967’s Cool Hand Luke, and adapted by Robert Stone from his own 1967 novel Hall of Mirrors, WUSA consider some of America’s – and the South’s – darker social and political impulses.

WUSA opens with scenes of a New Orleans parade as the credits roll. We see the wild costumes, the cars, and the floats moving along, and when it is over, there is trash everywhere, beer cans and other refuse swept to the curbs. Soon, we meet our three main characters: a white guy in sunglasses walking down the street with his bags (Paul Newman), a white woman hanging around in a city park (Joanne Woodward), and a young white man taking pictures of little black children playing (Anthony Perkins). After ambling for a few blocks, the first man, whose name is Rheinhardt, walks into a shelter for men and sits down among a group of older guys who are listening to a preacher in a dingy room. They are all bedraggled-looking, and the preacher extols the virtues of the Good Book. Meanwhile, in other scenes, the young woman is moving from one restaurant to another bar, inquiring about a job.

When we settled back on Rheinhardt and that preacher, who sent the men to get some dinner, we find out that they have been partners in a scam. The preacher took off from New York City after conning some old ladies, and Reinhardt has come to collect $100 he is owed, because he is nearly broke. The preacher doesn’t have it, but gives him $30 and a tip about a local radio station that has latched onto the “new patriotism.” As Reinhardt is leaving, the swindler-preacher Farley offers to help him with his drinking problem, but Rheinhardt just laughs at him.

The third character Rainey is a nice-looking young man in a seersucker suit and white shoes. He goes into a hotel where he looks a little lost. He is soon greeted, albeit coldly, by a black man in a suit, and we find out that he has come to pick up some social science surveys for his field work. He tries to get in the black man’s good graces with friendliness and with mentioning his interest in the subjects of his work, but the man, whose name is Clotho, is unimpressed.

Later in a tavern, the woman Geraldine is shaking her rear end by the jukebox and attracts the attention of a sailor (Clifton James). It becomes apparent quickly that she is trying to get him to pick her up. But she is thwarted when a man comes in, whispers to the bartender, then leaves, which leads the bartender to tell Geraldine to go out and talk to him. He is the pimp on that block, which we discern from seeing several prostitutes hanging around, and he warns her that he doesn’t want an “independent” working the block. She has scar across one cheek, and he threatens to give her another scar with his brass knuckles. Rheinhardt is sitting in the tavern and sees all of this go down. He finishes his drink and walks outside where Geraldine is trying to figure out what to do. He talks to her, and they walk away together.

After Rheinhardt buys Geraldine a steak dinner, they wander the streets a bit and end up back at the boardinghouse where she has a room. She wonders coyly whether he expects to be invited in, and he smiles and nods that he does. They go up to her room, where they talk a bit, share a few facts about themselves, and we learn that Rheinhardt is a failed musician. Then whatever might have happened doesn’t, because Geraldine looks over and he is asleep laying across the bed, still fully dressed.

In the morning, Rheinhardt walks into the offices of WUSA, all cleaned up and wearing a double-breasted blazer. Talking to station manager, he shares that he can do most of the jobs in station, having worked in smaller stations where people had to do more than one job. The manager is less interested in that than in making it clear that his station has a “point of view.” Rheinhardt is aware, and so they agree to take some copy, do a recording, and see if he measures up.

Next we see Rheinhardt, he walks into the boardinghouse bedroom while Geraldine is talking to her new friend Philomene (Cloris Leachman). He begins spouting some random things about being a liberal, which make no sense to the two women, then he shares that he has a job. What follows is a brief heart-to-heart that begins when Rheinhardt asks, with his back to her, about her life as a prostitute. She tells him that she worked mainly in Texas and that the scar on her face came when she said something to a man that he didn’t like. He replied, “You can’t do that in Texas.” He also asks if she is married, and she tells him that she was, but he was shot to death in a fight that he started when he was drunk. She in turn asks if he is married, and though he nods yes, he says, “I got a place over in the French Quarter. I’m heading over there.” She wants to go with him, and he says OK.

After shopping on what appears to be Canal Street, the couple gets to a small place in the French Quarter and moves through the courtyard to the stairs. While they go up, they run into Rainey, who is awkward in getting past them. Another man also emerges from an adjacent apartment. He is bearded and scowling and wearing only a pair of red shorts and a blue bucket hat. Geraldine smiles at them both, appearing somewhat pleased by their oddness, but Rheinhardt is unamused. Inside the apartment, they have a few uncomfortable moments as they set their things down. It is clear that neither of them is sure about what they’re doing, moving in together, but soon a grimacing Rheinhardt kisses a hesitant Geraldine, and they end the scene in bed.

In the light of day, we first see Rainey taking some more pictures of the impoverished black community, which quickly segues to Rheinhardt in the radio booth. We get a small taste of the rhetoric that station offers. The conman-turned-DJ does his work well but adds a cynical edge when talking to his tech guy, then after he finishes he goes out to a company car with the station’s logo and slogan emblazoned on the side: “The Voice of the American’s America.” Meanwhile, Rainey is seen in the down-and-dirty back alley where he goes to visit two elderly black women in a very poor small room in the back of a house. One is in the bed and appears to be dying. She is fingering a rosary, as the other woman sits nearby in a chair. When Rainey tries to asks the dying woman some questions, the caretaker hisses at him that she doesn’t know what she’s saying. Rainey apologizes and leaves then goes into a nearby kitchen where three black men are gutting some chickens and fish. He is there to see Clotho, the man from the first meeting. Clotho is holding an infant and makes some strange remarks about raising the child himself, since his mother is not around. The kitchen workers laugh at his comments, though the uptight Rainey is confused by them. Rainey then asks Clotho if he knows that the woman out back is dying, and Clotho tells him that the “whole community is gratified by your concern.”

Back in the little French Quarter apartment, Rheinhardt and Geraldine are lying around and getting drunk. Geraldine confesses that sometimes she would like to just be consumed by water and drown, but Rheinhardt admonishes her not to give in to despair, to instead become a “master of disguise” like he has. Rheinhardt then pontificates for a moment about the unfairness of the world, and Geraldine assures him that she already knows about it. Just then, Rainey appears at their door, knocking lightly. He has brought some ice cream to share. Geraldine is kind and friendly, letting him in, but Rheinhardt is chilly. Rainey then reveals his reason for coming. He has heard Rheinhardt on the radio, reading an editorial that contained serious accusations against the welfare department, accusations that Rainey knows to be unfounded. He wants to know from Rheinhardt about the facts that underpin the assertions. Rheinhardt explains apathetically that he reads what he is given at 6:00 PM and at 9:00 PM. Rainey, though, is not satisfied with that and presses him about how he can spread ideas that he doesn’t believe. This leads Rheinhardt to pull up a chair and sit very close to Rainey as he listens. The elder man asks what he does with the welfare department, and we sense that he is also asking why. Rainey stammers for a bit about having been in Venezuela and now coming back to do an essentially worthless job with this survey. Unmoved, Rheinhardt refers to Rainey as being one of the “somehow-good” and remarks that Rainey is clearly not in it for the money. Rainey replies sheepishly that he is just trying to reconnect with people and to be human, then he moves to leave, sensing that the conversation won’t lead anywhere (and perhaps also sensing that he is outmatched). As he goes down the stairs, Rheinhardt goes to the screen door to give him one jab, saying that he hopes it goes well, and ends their conversation with an exaggerated wink.

But this is about to get more serious than Rheinhardt previously understood. It is no longer just another gig to make a few bucks. He is called into a large expensive office, where three men are waiting on him. They don’t ask him to sit, and soon the station’s owner Bingamon comes out from his small bar to speak with his rising star DJ. He tells Rheinhardt that his format has garnered a number of new listeners, and they want to exploit his appeal by having him do public events. Rheinhardt agrees but in his own wary way. Then Bingamon once again explain the station’s politics, his rationale, and the methods for the work they’re doing. He says that the old politics won’t work anymore and that people are hurting, they just don’t know why or what to do about it. They – he and his group – have a way to relieve that, by making people aware of the damage done by crime and welfare. We understand that he is decrying the post-Civil Rights realities in the South and, looking back at it from modern times, that he is employing a platform that served pro-business conservatives well in reshaping the political landscape of the South. Bingamon explains that they have political candidates poised to run for office, that ideas are fully formed, and now they have a media presence that people appear to embrace. While the other men in the office appear pleased by this scenario, Rheinhardt recognizes (unhappily) that he will be the face and voice of their plans.

But this is about to get more serious than Rheinhardt previously understood. It is no longer just another gig to make a few bucks. He is called into a large expensive office, where three men are waiting on him. They don’t ask him to sit, and soon the station’s owner Bingamon comes out from his small bar to speak with his rising star DJ. He tells Rheinhardt that his format has garnered a number of new listeners, and they want to exploit his appeal by having him do public events. Rheinhardt agrees but in his own wary way. Then Bingamon once again explain the station’s politics, his rationale, and the methods for the work they’re doing. He says that the old politics won’t work anymore and that people are hurting, they just don’t know why or what to do about it. They – he and his group – have a way to relieve that, by making people aware of the damage done by crime and welfare. We understand that he is decrying the post-Civil Rights realities in the South and, looking back at it from modern times, that he is employing a platform that served pro-business conservatives well in reshaping the political landscape of the South. Bingamon explains that they have political candidates poised to run for office, that ideas are fully formed, and now they have a media presence that people appear to embrace. While the other men in the office appear pleased by this scenario, Rheinhardt recognizes (unhappily) that he will be the face and voice of their plans.

Across town, Rainey is still visiting Clotho’s hotel where welfare recipients are housed. Clotho still deals with him sardonically and sarcastically, mocking the young man with almost everything he says and does. Undeterred, Rainey continues his work. Clotho takes him up to a small room where a black transvestite is getting dressed up, and he explains to Rainey that the young man cashes his own checks and his sister’s, too. We don’t know for sure whether the young man actually has a sister or if the cross-dressed persona is being used to get two checks, but Clotho tells the transvestite that he is going to need a lawyer when he gets caught. Their next visit is to a frazzled young woman whose baby has been taken from her because she tested positive for TB. She is insane with grief, breaking into a story about a white college girl who killed her baby and put it in a shoebox. Rainey is horrified while Clotho smirks. Downstairs, before Rainey leaves, the two men trade remarks about the nature of God, and we understand that these are directed at the obvious difficulty of the residents’ situations.

At this point, WUSA is about halfway through its story, reaching the one-hour mark in a nearly two-hour runtime. So far, we have yet to meet an admirable character, though Geraldine and Rainey have our sympathy in a way that Rheinhardt and Clotho do not. We are also intended to see, I think, that the conservative politics of the post-Civil Rights South is a grift on ordinary people – ordinary white people, that is – who are uncomfortable and even afraid in this new era. The men behind the curtains have their ideas of how to use power and influence to create a new environment that suits them, but they need people like Rheinhardt who have the charisma to spread the message. Meanwhile, Rheinhardt is just using the station to get over, and Clotho is managing the day-to-day realities of the (black) people who incite the (white) fear that WUSA is exploiting. These two men are hardened realists who have grown cynical but keep going because they have no other choice. Rainey is the vehicle through which we see the squalor and deprivation of the black community’s circumstances, while Geraldine is the only force trying to humanize Rheinhardt, which is something that he resists.

The film makes an obvious transition at this point. We see some scenes of the river and of the city, which then focus in on Rheinhardt and Geraldine among an integrated crowd at a dixieland jazz concert. Rheinhardt is drinking, as usual, from his thermos, and Geraldine tries to joke with him about it. Later, outside at a park, the two are talking seriously, and the subject of Rheinhardt’s wife comes up. Geraldine is trying subtly to learn more about him, though Rheinhardt retorts with smarts remarks and evasions. Then, when he threatens to jump in the lake and end himself, she one-ups him and jumps in first. They swim in Lake Pontchartrain until dawn.

When we return to Rainey, he is back in Clotho’s hotel, where a young black dude in hip clothes is sitting at the bar. Soon, Clotho appears on the railing telling the man, whose name is Roosevelt, that he doesn’t want him there. Roosevelt is a newspaper reporter and has a vague and smart-aleck way of responding to both men. After Clotho tosses Rainey’s envelope full of surveys over the rail, the young white social scientist tries to ask the savvy black reporter what is going on: who is Clotho, and what is he doing? At first, Roosevelt is harsh with him, telling him that he doesn’t deserve answers. Then Rainey’s entreaties lighten him up a bit, and he explains that there is no survey, that Rainey’s work is farce that covers up Clotho’s involvement with political forces downtown, and that powerful people are trying to knock as many people as they can off of welfare rolls. And where can he hear all about it? On WUSA, of course.

Switching to Bingamon’s offices, there is a social gathering going on, and Rheinhardt is there. We are seeing the end of it, and Bingamon tells everyone thank-you for coming, and most of them ease out. Rheinhardt is still there, though, gulping down a whiskey drink, and Bingamon comments on his drinking. With the station manager standing there, Bingamon alludes to a rally coming up, one they have organized, and he expects that there might be some trouble. We understand that he means trouble from the black community. The manager appears frightened by this possibility, and Bingamon begins to make ominous statements about what is coming next, how they have to be ready for it, and how it will overtake anyone who isn’t ready. Rheinhardt takes this sardonically, continuing with his drink, but the manager is frightened by the suggestions.

In the evening, Rainey comes into their little courtyard and ascends the steps to look for Rheinhardt. He finds him in the neighboring apartment of Bogdanovich, the shirtless hippie in the blue bucket hat. Rainey comes in to find Rheinhardt drunk. Bogandovich is in the bathtub while two of his hippie friends smoke weed on the couch. Rainey wants to know from Rheinhardt “what’s happening,” and that leads the ragtag crew to encircle Rainey with weird Bob Dylan-esque answers to the question. Nothin they say makes sense though it is all clearly critical and cynical. Soon, Bogdanovich emerges from the tub and he has long pants on, then he walks wet into this den, where they all mock Rainey. He stands there and takes it, until he finally walks off, but only after insisting to them that their nihilistic attitudes are wrong, that human life does have value. The only who one who is upset their cruel behavior is Geraldine, who leaves almost in tears. Rheinhardt follows her.

Down the way at their apartment, Geraldine asks Rheihardt why he is so mean, and he responds, “Self defense.” He then dresses her down in the cruelest way that he can. Rheinhardt reminds her that he can leave anytime he wants because he knows very well how to do it. He also rants about how he hates whiners and says that she probably goaded her husband into the fight that got him killed.

The next day, Rainey goes walking into the Playboy Club in the Quarter and talks his way into the private room to address Carl Minter, the man he has been told masterminded the scam that is his survey. We find out here that Rainey is a judge’s nephew, so he is from a prominent family. Once he locates Minter, who was one of the men in Bingamon’s office in that earlier meeting when Rheinhardt was informed his new and more public role, the man has no idea who Rainey is. With a characteristic lack of tact, Rainey addresses the conservative businessman – who, mind you, is eating lunch in the Playboy Club – and accuses him of, essentially, fraud. Minter is nice at first but loses his patience when the young liberal begins to be more aggressive and threatening. They trade remarks about fear, and Minter tells him that soon a lot of people like Rainey are going to be very afraid. The tense exchange, which draws the attention of the other guests, ends with each man making vague threats against the other. In the evening, then, Rainey is visited by two police officers who come to intimidate him.

As WUSA enters its final half-hour, the rally begins. There are cheering crowds in a large auditorium. Confederate flags are waving, a band is playing “Dixie,” and they even have balloons that say “WHITE POWER” on them. There are loads of square, middle-class white people all comfortable inside the arena, but there is an angry black mob getting riled up outside. The rally begins with a prayer from Rheinhardt’s conman-turned-preacher friend Farley, then Bogdanovich and his hippie friends are brought on to sing some gospel tunes. They get booed though, and it’s hard to tell whether they were added into the show to be the foil: the countercultural types that these attendees don’t like. While this is going on, we see Farley enter stealthily and begin sneaking around the venue. He makes his way up into the fly rails above the event and uses the opportunity of phony gunfire during a Wild West demonstration to begin shooting at the people on the stage. He aims for Bingamon and Minter but misses, killing the station manager who was so tentative in earlier scenes.

After that, the crowd goes crazy as people run for their lives. People are pushed over and knocked down, while Farley tries to get their attention. Then Farley pulls Rheinhardt to the podium, and despite the wild scene in front of him, he carries off a calm speech about this crowd’s version of American values. It is a strange juxtaposition, the measured way that he speaks and the unruly way that the crowd is behaving. While he speaks, Rainey tries to walk through the crowd brandishing a pistol in full view, and he is pulled to the ground, where a mob swarms him and beats him bloody. As this is happening, Rheinhardt is reaching the message of his speech: “We’re OK!” he keeps insisting, as we see Rainey’s bloody and terrified face. During this, we also cut to Geraldine is awestruck, flabbergasted, and dismayed by what she is seeing. Rheinhardt has lost all control, over the crowd and over his own sense of reality. Inside, people are fleeing, though outside, a full-on riot is happening.

WUSA ends on multiple notes of despair and hopelessness. Farley escapes, with Rheinhardt in the car, and tells his fellow conman that he’ll be on a plane out of town soon. He suggests that Rheinhardt do the same, but the DJ says no, that there’s someone he needs check on. We know that someone is Geraldine, but she has been arrested after going back into the dangerous crowd to find him. The hippies stuck their weed into her purse, in fear of being grabbed up by police themselves, and she has taken the fall for it. Two female officers tell her that she is facing fifteen years, if convicted. Last we see of her, she commits suicide in her jail by breaking her own neck with the chain that holds up a metal bunk. Rheinhardt is lying around in Bogdanovich’s apartment when he finds out. Her friend Philomene shows up to their courtyard to tell him. She says that he must have been some boyfriend, considering that Geraldine had given the cops her address instead of his. Philomene had to go down and identify the corpse. After a brief walk through the cemetery, Rheinhardt leaves the place in his double-breasted jacket with his suitcase all packed. He had gotten off scot-free, as has Farley, and the characters who have been destroyed were the only decent human beings in the story: Rainey and Geraldine.

As a document of the South, this film’s scenario should seems awfully familiar to both a student of Southern history and to a common-man viewer in the 2020s. The historical facts of the political transformation from the Democratic “Solid South” to a “ruby red” Republican stronghold are well-known to those interested in the particulars of our history. That trajectory from the demise of the segregationist Democratic Party to the suburban conservatism of the Republicans was led by figures like the ones who are pulling Rheinhardt’s marionette strings. For an ordinary person today, on the other hand, the paradigm in WUSA has been replicated on a larger scale by more modern programmers like Rush Limbaugh and Fox News. Early in the film, Rainey’s objections to the anti-welfare editorials smack of the media environment where “news” is a fast and loose concept and where “alternative facts” are viable if they support the rhetoric. I also can’t ignore the fact, given the political climate of 2025, that Minter’s scheme is an effort to weed out what the current administration has dubbed “waste, fraud, and abuse” in government programs. This story from 1970 is a cautionary tale, perhaps even a jeremiad, that could be seen as the flip side of the coin to Kevin Phillips’ work in the late 1960s and early ’70s. Phillips saw where it was going, and WUSA warned us not to go that way. But it appears that we did anyway.

Looking at locale, setting the story in New Orleans also offers some opportunities for the film. The Crescent City has a longstanding reputation as a wild place, so we are not surprised when something wild happens there. This is the city where Stanley Kowalski overtook Blanche DuBois in 1955’s A Streetcar Named Desire, where Dove sought Hallie in 1962’s Walk on the Wild Side, and where Wyatt and Billy came to enjoy Mardi Gras in 1970’s Easy Rider. It is also a city with a long history of racial tensions, from the Massacre of 1866 to young Ruby Bridges integrating the schools in 1960. And we see those divisions in this film, in the stark differences between places where white people are and the places where black people are. Perhaps most importantly for our characters, New Orleans is a place where people go to start over or to live an unconventional life. Rheinhardt has come there to hide from his past in New York City, Geraldine has come there to leave her life in Texas behind, and Rainey is there to shake off the “illness” that he mentions in his first conversation with his neighbors. All three are trying for a fresh start.

Though WUSA starts out almost as a Carson McCullers-style story of a couple of lost souls who happen upon each other, it is in the second hour, after Bingamon’s decision to make Rheinhardt into a more public figure, that the film becomes disturbing. In November 1970, The New York Times‘ Vincent Canby wrote the following in “‘WUSA’ Makes You Want to Talk Back to It”:

It is the work of liberals who—as I understand them—are concerned about the consequences of apathy, about the manipulation of political engagement, and about the silent conspiracy that must always exist between the exploiters and those who are exploited. Although these are not necessarily revolutionary concerns, they are valid ones. They are so valid, in fact, that only a work of such self‐conscious pretensions, such obvious reverse bias and such narrative incoherence could, if not discredit them, at least render them peculiarly irrelevant.

Personally, I disagree that the storytelling was incoherent, but Canby is right that this film is a pretty vicious portrayal of conservatives in the South. Here, they are sneaky and manipulative and without morals. In reality, the kinds of local Southern leaders who suffused their desire for safety and material prosperity with polite social mores, quiet racism, and a bourgeois version of Christianity were the ones using politics, media, and other tools to garner support for their vision from working- and lower class whites. But they had a goal: to emerge from the changes of the Civil Rights era with a culture that was acceptable to them. These guys in WUSA have no positive goals for their community. They only seem to want to create ire and strife for its own sake.

The year after the film’s release, scholar Joan Mellen remarked in a 1971 Film Studies Quarterly article on “Fascism in the Contemporary Film” that one problem with viewing Bingamon and his cronies as fascists is that they are not “shown to have any theory of government or coherent program of change.” I take her point, but in my understanding of them, Southern politicians who led reactionary populist movements were not really fascists anyway. They may have had narrow-minded ideas about norms and sought a selfish kind of power, but their efforts were not based in an intellectual tradition or engendered ideal. Southern demagogues and populists are rarely, if ever intellectuals. Usually, they’re the opposite, such as Huey Long or George Wallace. Certainly, the rally at the end of the movie has fascist qualities, and it does feature a crowd that has been whipped up into a frenzy, but the event looks more like mixture of a White Citizens Council meeting, a tent revival, and a pep rally during football season. The polemics are not the raison d’etre here— the carnival atmosphere is. Once the shooting starts, there isn’t a single person willing to stick around and die for the ideals that they were there to support. (I can tell you how many people would have attended if it was just a hyped-up philosophy lecture. None.)

And since I opened with it, I’ll close with it, too. This is not one of the Paul Newman’s better films. But not because it’s not a good film. It’s because we want to like Paul Newman, even when he plays a dour drunk, as he does in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, or a self-absorbed jerk, as he does in Hud. It’s like having Andy Griffith play the villain in Murder in Coweta County— Andy Griffith is not a villain! And Paul Newman is not a guy we dislike or pity. Because of who Rheinhardt is and what he does, we can’t pull for him . . . even though we want to pull for Paul Newman. It just doesn’t work that way.

May 6, 2025

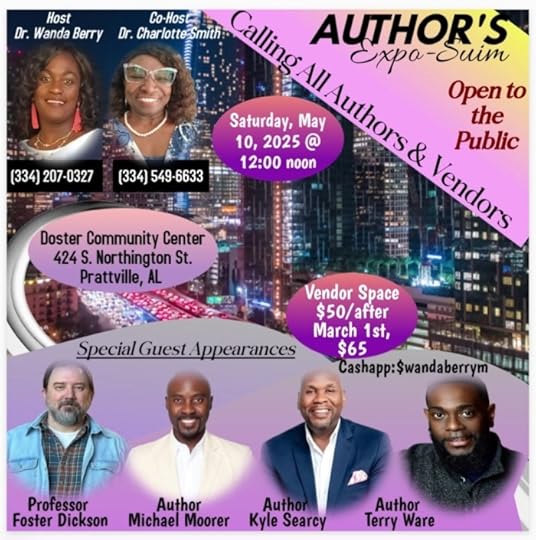

The Author’s Expo-sium, May 10

April 29, 2025

Fifteen Years of Unapologetically Eclectic Pack Mule-ing

Fifteen years ago today, I put up that first post. I had just finished a Surdna Foundation Arts Teacher Fellowship, which I used for the Patchwork project, and had been blogging that year about modern life in Alabama. So, with a phrase from a poem I wrote in 2002 – “pack mule for the new school” – I started my own author website and blog. At that time, in 2010, I considered myself something of a writer and social-justice educator, having taken part in a variety of committees and projects mostly devoted to reviving or sharing the history of the Civil Rights movement. Many of my student projects had also used experiential learning to reveal more about local culture and often-untold stories to a new generation. The idea of being one simple, humble worker in an ongoing movement was what led me to that title. I saw myself then – and still do today – as a relatively unimportant person doing groundwork to create community and achieve social justice. My specialty: helping to create a more vibrant and more public recognition of the South’s actual history and current reality.

During the 2010s, as this blog got going, the tenor of social-justice work was intensifying nationally but also becoming compartmentalized in my local community. In the 2000s, I had worked mostly among older people (Boomers), who were seeking to enshrine the Civil Rights-era history of the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. Yet, by the mid-2010s, the mantel had been taken up by groups and projects led mostly by younger people (Millennials), who were seeking to “reclaim the narratives.” Less interested in working with a diverse coalition of conscientious friends, these younger activists grounded their vision in identity politics to have female voices telling female stories, black voices telling black stories, LGBTQ voices telling LGBTQ stories, and so on. I had no problems with that approach – in fact, I understood and respected it – but it had real effects on my role in the kinds of social-justice work that I had been doing from my late 20s through my early 40s. The approach of the new generation meant that the attitude toward me as a participant in social-justice projects became: Thank you for what you’ve done up ’til now, middle-aged white guy, but we can do our thing without your involvement.

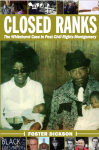

It took a while – perhaps too long – to recognize and accept that that phase of my career was coming to a close. The first sign was that the once-regular invitations to join committees and other planning efforts stopped coming. A second sign was the tightening of local school system policies for field trips. The procedures had become so stringent (out of fears about injuries and lawsuits) that I could no longer get my students out into the community during the school day. By the mid-2010s, those dual factors severely hampered the work that I had been doing in the 2000s and early 2010s. Then, I felt the impact of the new reality most sharply when, after the release of my book Closed Ranks in November 2018, local social-justice groups showed little to no interest in the story. The Whitehurst Case was a pivotal episode in Montgomery’s history, but the Whitehurst family and I struggled to get people to attend events or read the book. The last of my student projects, Sketches of Newtown, was undertaken just prior to and during the ultra-restrictive months of the COVID-19 quarantine, then it was published in 2021. During the research, writing, and compilation of the monograph, I could tell that, for me, it was the end of an era.

It took a while – perhaps too long – to recognize and accept that that phase of my career was coming to a close. The first sign was that the once-regular invitations to join committees and other planning efforts stopped coming. A second sign was the tightening of local school system policies for field trips. The procedures had become so stringent (out of fears about injuries and lawsuits) that I could no longer get my students out into the community during the school day. By the mid-2010s, those dual factors severely hampered the work that I had been doing in the 2000s and early 2010s. Then, I felt the impact of the new reality most sharply when, after the release of my book Closed Ranks in November 2018, local social-justice groups showed little to no interest in the story. The Whitehurst Case was a pivotal episode in Montgomery’s history, but the Whitehurst family and I struggled to get people to attend events or read the book. The last of my student projects, Sketches of Newtown, was undertaken just prior to and during the ultra-restrictive months of the COVID-19 quarantine, then it was published in 2021. During the research, writing, and compilation of the monograph, I could tell that, for me, it was the end of an era.

By the early 2020s, my work as a writer and teacher had taken on a markedly different shape. Picking up on the signals meant changing the name of the blog to “Welcome to Eclectic,” since that title better described my work at that point. My interest in the stories of Generation X grew as I moved away from movement-era subjects. The years 2020 and 2021 brought the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic. In May 2022, after two rough school years, I left my job as a high school teacher to accept a teaching job at a small college. My next book project, which was published in 2023, was not a social-justice story but a historical monograph for our local Catholic school’s sesquicentennial. I haven’t been involved in any organized social-justice projects in quite some time, and many among the elder generations I once worked with have now passed away.

Recent years have been spent re-imagining my work. During the pandemic years, I created Nobody’s Home and level:deepsouth, though the latter project was short-lived. Nobody’s Home is an online anthology that focuses on beliefs, myths, and narratives in the post-Civil Rights South (since 1970). What I have come to understand from reading critical theory and historical studies is that our actions are often based on what we believe, what truths we embrace in our own (sub)cultures, and what stories we tell ourselves and each other. Nobody’s Home, which proceeds from that understanding, is approaching its fifth anniversary and has more than fifty essays alongside lesson plans and other resources. Here, on the blog, I have been putting effort into the Dirty Boots column, long-form Welcome to Eclectic posts, and the Southern Movies series. Since the fall of 2022, my work as a teacher has shifted from a public (magnet) arts high school, where I taught creative writing and twelfth grade English, to a small liberal arts college, where I have provided writing assistance, led a peer mentoring program, and taught when needed. Through the peer mentoring program, I’ve also become an NASPA Certified Peer Educator trainer.

Recent years have been spent re-imagining my work. During the pandemic years, I created Nobody’s Home and level:deepsouth, though the latter project was short-lived. Nobody’s Home is an online anthology that focuses on beliefs, myths, and narratives in the post-Civil Rights South (since 1970). What I have come to understand from reading critical theory and historical studies is that our actions are often based on what we believe, what truths we embrace in our own (sub)cultures, and what stories we tell ourselves and each other. Nobody’s Home, which proceeds from that understanding, is approaching its fifth anniversary and has more than fifty essays alongside lesson plans and other resources. Here, on the blog, I have been putting effort into the Dirty Boots column, long-form Welcome to Eclectic posts, and the Southern Movies series. Since the fall of 2022, my work as a teacher has shifted from a public (magnet) arts high school, where I taught creative writing and twelfth grade English, to a small liberal arts college, where I have provided writing assistance, led a peer mentoring program, and taught when needed. Through the peer mentoring program, I’ve also become an NASPA Certified Peer Educator trainer.

With these fifteen years now in the past – a lot has changed between 2010 and 2025 – my beliefs about this state, its culture, the South, and the answers to the problems remain pretty solid. We need change. We need to base our decisions on facts, not myths. And we can only arrive at a better society if we embrace inclusivity and community, allowing contributions from all people of good will. The way I see it, all of us have to live together, so all of us should be involved in the giving, taking, talking, listening, cooperating, compromising, and creating. For now, I’m spending my energies in ways that I believe I can be useful, by serving students as a writer and educator, critiquing narratives in the modern South, and exploring the lives of Generation X in the modern South. As for another full-length book . . . who knows? Maybe.

If somebody were to ask me at this late date, why should I read your blog? The answer remains the same: For an independent perspective. I’m a liberally conservative moderate and a Southern Christian who isn’t Protestant. I am also among a minority of Southerners with a postgraduate level of education. You might also notice that there are no ads here, nor are there required subscriptions to read this blog. All in all, I’m likely to write things you won’t read everywhere else, and I don’t require anyone to pay or to join. That may not be the thing for folks who like single-issue politics with simplified platforms and agendas that rely on heuristics and stereotypes, but it’s the only way that works for me.

Read More: Books • Nonfiction • Poetry • Nobody’s Home

April 22, 2025

Dirty Boots: In Praise of Old Movies

It felt pretty good. A couple of weeks ago, my wife stopped me and said, “There’s this story I saw on CBS Sunday Morning, about movies, and you need to watch it.” It was Academy Awards weekend, and most of the news outlets were putting emphasis on the movies. What was the story about, I asked. “It was talking about how they just churn out movies now to sell tickets. It’s what you’ve been saying all along.” Exactly the kind of thing a husband likes to hear from his wife: It’s what you’ve been saying all along.

In that story, “How making, and watching, movies has changed,” we hear from industry folks about how the willingness to invest money in original, daring, or artistic projects has diminished and how that money is now more often spent on sure-thing projects involving known commodities, like franchises, series, and sequels. There is also an explanation of the enduring albeit scant presence of “indies,” films with smaller budgets whose stories deal with more complex and less flashy subjects. So we can’t say cynically, Nobody makes good movies anymore . . . Yes, they do. But that hard-to-find quality has morphed within the shift in viewing habits. Indies – which used to be made cheaply and independently – were once harder to find because theaters and video rental stores didn’t have the physical space for them; today, even more films are hard to find because the streaming services’ main pages don’t have digital space for them. The banner ads and sponsored listings are today being bought up the way that roadside billboards, prime time TV commercials, full-page ads in magazines, and end caps in stores once were.

In that story, “How making, and watching, movies has changed,” we hear from industry folks about how the willingness to invest money in original, daring, or artistic projects has diminished and how that money is now more often spent on sure-thing projects involving known commodities, like franchises, series, and sequels. There is also an explanation of the enduring albeit scant presence of “indies,” films with smaller budgets whose stories deal with more complex and less flashy subjects. So we can’t say cynically, Nobody makes good movies anymore . . . Yes, they do. But that hard-to-find quality has morphed within the shift in viewing habits. Indies – which used to be made cheaply and independently – were once harder to find because theaters and video rental stores didn’t have the physical space for them; today, even more films are hard to find because the streaming services’ main pages don’t have digital space for them. The banner ads and sponsored listings are today being bought up the way that roadside billboards, prime time TV commercials, full-page ads in magazines, and end caps in stores once were.

As an old movies guy, and as a Southern Movies guys in particular, I wonder who is going to make today’s best movies. What filmmaker is going to bring us the zeitgeist of the modern South, whether those portrayals are mythic like 1958’s Thunder Road or supernatural like 1971’s Brother John or harshly realistic like 1988’s Mississippi Burning? If most of the production money is going to another Batman, another Marvel or DC, another shoot-’em-up, another rom com, then most of the marketing money is also going to those films . . . And we end up with portrayals of Southern culture that are plastic and half-true. Some films try to branch out, but you end up with stuff like The Death of Dick Long about two rednecks who try to avoid taking responsibility for letting a horse fuck their (male) friend to death. (This one was written by the same guy who made Everything Everywhere All at Once, and I was sorely disappointed in it.) I will say, regarding relatively recent films, that I think James Franco did a good job on his As I Lay Dying, Child of God, and The Sound and the Fury in the 2010s. But those aren’t about the modern South, and I also don’t think those are great films, because all three adapt literary works that are stronger on the page than on the screen. Oprah Winfrey’s Beloved has the same issue.

In the annals of film, there have always been plenty of blockbusters, handful of instant classics, and certainly a number of clunkers – drive-in features, exploitation films, and weak sequels – but the weaker movies get overshadowed by great ones then forgotten. If people mistook a bad movie for being good, that misconception didn’t last long. Today, I hardly see films set in the South that I believe will stand the test of time. Some I’ve seen that could are The Yellow Handkerchief, set in Louisiana; Queen & Slim, which takes us to Florida, and Netflix’s historical dramas The Devil to Pay and Mudbound. The most celebrated recent film, The Green Book, swept the Oscars in 2019, but I don’t hear people talking about that movie today. 2020’s Where the Crawdads Sing faded quickly into being the genre film that it always was. The clunkers that I see these days, coming out at the rate of a couple a year, are heavily reliant on stereotypes: moralistic racial-justice dramas based on either-or paradigms, romantic comedies set in small towns where almost everyone is polite and attractive, backwoods white-trash stories that feature extreme violence, horror films carried by flabby versions of regional monsters and mythologies.

I’ve also considered the idea that this isn’t the film industry’s fault, that the culture of the South currently doesn’t offer material for a movie, much less a great one. The Depression-era South offers a creative mind many opportunities for Man vs Nature stories. The Civil Rights movement is chock-full of Man vs Society stories. The ’70s and ’80s were just plain weird and quirky. Even the ’90s had some changing-culture motifs. But today . . . what is there to make a feature film about? Many scholars declare that the South’s regional uniqueness and separateness have been either diminished or eliminated by assimilation into the larger national culture. Beyond that, ours is a backward-looking time and one heavy on individualistic tendencies. On one side, some people are immersed in having “conversations,” in re-evaluating the past, and in changing what we memorialize. (I’ve been part of this trend too, in my work.) On the other side, we have people who want to “return to traditional values” and undo the changes of the last seven decades. We are also a people, today, who willingly sacrifice community to pursue personal goals and agendas. That troubling feature of our culture manifests as “school choice,” church splits, book bans, divisive politics, and myriad reasons for petty lawsuits. That’s a problem for a creative thinker who is crafting a story for a mass audience.

What would a filmmaker find in the South of the 2020s: teenagers in hoodies who stare at their phones? Republicans in legislatures who defund Medicaid? A small town that gets a new Dollar General? Sports dads in subdivisions who politick over little-league rule changes? Exciting stuff. In the South of the past, large social and societal concerns were addressed and their conflicts played out on public stages: dire poverty, racial strife, religious hegemony. The outcomes affected millions of people, and in ways, they affected whole nation. Today, not so much. We’re down here bickering over minutiae and trying to make sure that poor people have as little as possible. Perhaps one exception, an issue that might fit the bill for a great movie, is the clash over abortion rights. These are stories of life and death. If a filmmaker handled that cultural struggle in a complex way like, say, the 1999 film Magnolia or like 2004’s Crash, he or she might have something. It’s a better idea than trying to make another high school sports movie, this time about a kid who just wants NIL money so he can buy a big truck, sneakers, and video games.

Meanwhile, I’ll keep my righteous butt down here in central Alabama, pleased by the knowledge that it’s what I’ve been saying all along. And equally pleased to be sitting around, watching old movies.

April 15, 2025

The 2025 Open Submissions Period for “Nobody’s Home”

Starting today and ending June 15, I will be reading and considering submissions of creative nonfiction to expand the Nobody’s Home anthology. All submitting writers should read the guidelines thoroughly, then send a query and wait for a response about whether to send the work. I am particularly interested in works about or set in the states of Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Texas, as they are currently underrepresented in the anthology. Works accepted during this time will be published in August 2025.

Starting today and ending June 15, I will be reading and considering submissions of creative nonfiction to expand the Nobody’s Home anthology. All submitting writers should read the guidelines thoroughly, then send a query and wait for a response about whether to send the work. I am particularly interested in works about or set in the states of Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Texas, as they are currently underrepresented in the anthology. Works accepted during this time will be published in August 2025.

This year’s Open Submissions Period is the sixth for Nobody’s Home. In the project’s inaugural year, the first three Open Submissions Periods were held in the latter half of 2020 and the first half of 2021. Subsequently, in 2022 and 2023, unsolicited submissions were read in the spring, with accepted works published each summer. Invitation-only submissions periods have been held in the fall of those two recent years.

Submissions of reviews and interviews will continue to be considered during this time. Again, anyone thinking about a submission should read the guidelines thoroughly before sending a query.

Nobody’s Home: Modern Southern Folklore is an online anthology of nonfiction works about beliefs, myths, and narratives in Southern culture over the last fifty years, in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The project, which was created in 2020, collects personal essays, memoirs, short articles, opinion pieces, and contemplative works about the ideas, experiences, and assumptions that have shaped life below the old Mason-Dixon Line since 1970. Today, Nobody’s Home features more than fifty essays and offers secondary-education lesson plans for English and Social Studies classrooms, suggestions for documentaries, and reviews of books, as well as Groundwork, my editor’s blog.

April 10, 2025

Sharing the Good Stuff: Barack Obama at Hamilton College

Barack Obama left the White House more than eight years ago, but he has remained an important presence in American life. Here, he shares his thoughts on our current situation, this democracy, and what ordinary citizens can do to make things better. Perhaps the most important thing that he asks is: can we defend free speech even when we hear things that we don’t like? These remarks made during an open forum at Hamilton College, a liberal arts institution in New York, were shared by PBS News Hour.

April 7, 2025

A Quick Tribute to “Big Bear” RG Armstrong

The name of actor Robert Golden “RG” Armstrong may not be as well known as some, but fans of Southern movies will know him as Big Bear, the hardened moonshiner in the 1973 classic White Lightning. Even in a field of great actors giving strong performances – Burt Reynolds at Gator McCluskey, Ned Beatty as Sheriff JC Connors – Big Bear is still one of the memorable characters in Southern movies. Gator is introduced to this greasy and gruff leader of backwoods moonshine production by his friend Rebel Roy, and within a short time, the elder man has a large hunting knife to the new arrival’s throat. Ultimately, Big Bear will be one of the men who capture Gator, who has been let out of prison to infiltrate the operation. They intend to kill him, of course, but Big Bear is injured in the drunken melee instead. The last we see of him, he is sitting in JC Conners’ car at Dude Watson’s funeral and suggests that they go fishing some time.

RG Armstrong was born on this day – April 7 – in 1917 in Birmingham, Alabama. He later attended the University of North Carolina and did theater there before moving into an acting career. He had roles in the Southern classics Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and The Miracle Worker on Broadway. From the mid-1950s through the late 1960s, his acting work had him both on TV and in movies, often in westerns, and by the 1970s, he was landing roles in a wide variety of projects, even blaxploitation films. He played the sheriff in 1961’s The Fugitive Kind, which was set in Mississippi. In the 1970s, Armstrong had parts in other lesser-known Southern movies: 1972’s The Legend of Hillbilly John, 1975’s Dixie Dynamite, and 1979’s Steel. Later, in the ’80s, he was the town doctor in 1982’s The Beast Within and the mountain family’s patriarch in 1989’s Trapper County War. On TV, his work included roles on The Andy Griffith Show in 1960s and on The Dukes of Hazzard in the ’80s.

RG Armstrong died in 2012 at age 95. His New York Times obituary called him “a rough-hewed character actor known for playing sheriffs, outlaws and other macho roles.” Turner Classic’s website describes him this way: “A flinty, often imposing presence in features and television for over half a century, character actor R.G. Armstrong played men whose mere presence elevated the tension.” Aside from his prominent film career, Playbill magazine remembered him as a “Tennessee Williams Actor,” and the fan wiki for The Andy Griffith Show recounts his Farmer Flint character.

April 1, 2025

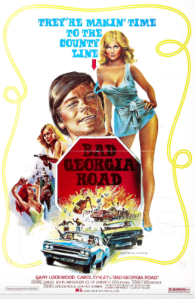

Southern Movie 76: “Bad Georgia Road” (1977)

The 1977 hicksploitation film Bad Georgia Road is one among a slew of these from the 1970s that feature stories involving fast cars and illegal liquor. If you haven’t heard of these films, it’s probably because the majority were eclipsed by the monolithic masterpiece in the genre: Smokey and the Bandit, also from 1977. Despite its name, Bad Georgia Road isn’t set in Georgia at all. The story puts us in Alabama, where young New York City fashionista Molly Golden has come south to claim land that she has inherited from an uncle she never knew. Expecting to find a classic antebellum estate, she instead arrives at a dilapidated homestead— which comes complete with a moonshine operation. That latter part is initially withheld from her, but its continued operation means that the wild and crazy good ol’ boy Leroy Hastings will be coming around in his fast car. Starring Carol Lynley and Gary Lockwood, Bad Georgia Road was directed by John Broderick, who had produced Six-Pack Annie a few years earlier.

The opening scenes of Bad Georgia Road show Leroy Hastings evading two men in a car, as he flies down the backroads in his 1970 Dodge Roadrunner. The pair, who are in plainclothes and not flashing blue lights, are trying to keep up with him. The driver is a buffoonish type in a Civil War infantry cap, while the passenger giving orders and criticizing his performance seems to be a higher-ranking guy. Quickly, Leroy outmaneuvers them by running up ahead, hiding around a curve, then pulling out in front of them. This causes the unsuspecting men to end up in a field as Leroy drives away. As we watch all this, a raucous country tune about moonshining plays.

Soon, we find out about Leroy’s destination. There is a funeral going on in a small graveyard, and a few scroungy-looking people are gathered to pay their respects. The small tombstone reads “Elton Payne, 1897 – 1973.” The hardscrabble bunch amble off after a few words have been said, then Leroy arrives – late – in a pinstriped sport coat with his dirty jeans and t-shirt. Leroy looks like a thirty-year-old former high school football player, stocky with a shaggy non-haircut and an unshaven face. Talking to the elderly man who led the service, Leroy finds out that Elton’s heir “Molly something” is being notified by the local lawyer that she has an inheritance.

Next, we meet Molly in a big city office, where she and a few other women bicker and make catty remarks. She accuses one of them being a closeted lesbian who wants to get in her pants. After a moment, one of the women goes into another room and returns with a set of red padded toy bats, which they will apparently use to beat out their aggression on each other. Before they begin, Molly gets word of a phone call and leaves before the swinging begins. On the other end of the line is a fat country lawyer, who explains briefly that she has been given $100,000 in a bank account and her Uncle Elton’s land in Alabama. She seems elated.

Soon, she and her gay best friend Darryl are riding the two-lane highway in a Mercedes convertible, while Darryl reads out loud from Streetcar Named Desire. They fantasize a bit about what a romantic thing Southern life will be. Then reality hits! Up a long dirt driveway, there it is: old barns, an old house, junk everywhere. As they get out of the car, Arthur Pennyrich – the old hillbilly who officiated the funeral – emerges from the trees and fires his gun at them. Not knowing who they are, he can’t be too careful. But Molly is undeterred. She takes charge of the situation, bossing Pennyrich about his behavior, and retorting that his assistance will not be necessary. Meanwhile, Leroy comes pulling up. His tires throw dirt everywhere, while Molly yells at Pennyrich to stop him. Soon, Leroy comes to halt and gets out of the car. He is guzzling moonshine from a mason jar and throwing his weight around, while a pretty blonde in the car begs to come on and leave.

The aspects of the film’s story are now in place. Bad Georgia Road is one part Thunder Road and one part Green Acres, with the set-up of a romantic comedy. Leroy is a fast-driving wild man, and Molly is a city girl who has come to the country. Our leading man and leading lady are wildly different people, and they dislike each other from the moment they lay eyes on each other.

Back at the house, the portly attorney Depue drives up in his Cadillac to deliver the papers she’ll need to sign. Everything is amicable until she asks when she’ll get the cash. There is no cash, he tells her. She has just signed the papers saying that Uncle Elton’s debts can be paid out of his estate, which means the money was gone before she even came to get it. Molly wants to sell the land then, and Depue informs her with a smug smile that no one in the area will be interested or able to buy it. Molly is stuck in Alabama with no money. She has quit her job, thinking she will have it made. Now, she’s a stranger in a strange land. That evening, she and her pal Darryl discuss the options for how to escape the predicament— sell it to Arthur Pennyrich.

In the light of day, we see Pennyrich in an old blue truck hauling some hay bales across a meadow. In the trees nearby sits the sheriff with his binoculars. He is surveilling the old bootlegger, who picks up on him by the glare on the lens. So Pennyrich pulls out his rifle and shoots the sheriff’s hat off his head, chuckling about he has thwarted the meddling dummy. In the barn, a few moments later, he is loading jugs of moonshine out of the hay bales and into Leroy’s car . . . when Molly walks in. She demands to know what is going, and the men begrudgingly reveal the truth. Molly objects, on the grounds of wanting to avoid prison, but Leroy overrules her by getting in the car to drive off.

He comes back shortly, when Molly is in the yard wearing a green bathing suit and doing something like yoga. He rolls in slowly and, when he gets close to her, tosses a brown paper bag over the roof. It lands beside her. It’s a big stack of cash. Just then, gay best friend comes out to urge her into the plan – they had decided to leave in the morning – but she smiles coyly and declares that she’s starting to like it there. He is dismayed, but can’t do much about it. After he goes back inside, Molly saunters over to the garage where Leroy is cooking eggs. He is dirty and has no pants on. As she tries to speak to him in a friendly manner, he just stares back and eats in a way that is almost animalistic. She is trying to get on his good side, but when he nods his head toward the bed, she takes that as her signal to either go all in or get out.

In the house, Molly does some figuring. Striding out, she beckons Leroy and Pennyrich into the barn, where she makes her offer. She asks how many runs they can make per week, and Pennyrich says five. Molly takes that bit of info and offers the two men 30% of the take, which would come to about $40,000 per year to split between them. She also asks to know the ingredients, which they reveal, and she tells them that buying all that will come out of their end, too. Leroy doesn’t think that’s fair, but Molly retorts, “Without me, you’ve got nothing.” With a sneer, he comes back, “No, without you, we’ve got everything.” However, Molly is undeterred and strides out the barn with confidence. She will get rich off of these two.

The next time Molly sees Leroy, he is pulling to the dirt driveway with a different woman in the car. He once again toss the paper bag over the car to her feet. She doesn’t look amused, and we can tell from her cold expression that she is falling for Leroy. Seeing him with another woman makes her jealous, but it gets much worse when he and this woman go into his little hovel and make a ton of noise. Molly tries to reciprocate, making a pass at Darryl who is still in bed, but not much comes of it.

Out in the yard later, Darryl is lounging on the swing while Molly has set up a place to sunbathe near Leroy’s car. He is tuning it up, and she has a mind to pester him. First, she asks him to adjust her umbrella then to put lotion on her back. She gives these orders with her back turned, so he uses the opportunity to put engine grease in her suntan lotion. Molly comments on the fact that he is always dirty, and he responds that what she really wants is not a man but trained monkey. She calls him a “sexual ghoul,” so Leroy says that, considering how she brought a “queer” down here with her, she must not even know what a man is. They have a quick back and forth about women’s rights and chauvinism, an argument that Leroy sees no point in. Soon, he goes back to his car as she rubs blackish lotion all over her face. Once Molly realizes what has happened, she storms inside silently. Darryl has been watching the whole time, and Leroy gives him a flirty wink to put an end the scene.

Bad Georgia Road is now at the halfway mark. There is nothing unpredictable. Both Leroy and Molly are “types”— he is the rural ruffian, only interested in speed, liquor, and sex, while she is a bossy, greedy feminist from the modern city. Neither one understands the other. Yet, here they are, put together unwittingly.

Bad Georgia Road is now at the halfway mark. There is nothing unpredictable. Both Leroy and Molly are “types”— he is the rural ruffian, only interested in speed, liquor, and sex, while she is a bossy, greedy feminist from the modern city. Neither one understands the other. Yet, here they are, put together unwittingly.

In the scene that follows, we find out about the two men in the opening scene, the ones who were chasing Leroy. The sharper one of the two comes walking through a parking garage and gets into a black limousine. He speaks to an older man, Mr. Larch, who is in the back seat with a pretty young woman. Larch is affable but tells the henchman that something must be done about Leroy Hastings. The young man has been too successful, and the members of their “cooperative” are considering leaving the fold. There are insinuations of organized crime here but nothing overt.

Back in the country, Leroy and Pennyrich are loading up again. Pennyrich tells Leroy to be careful, and knowing what we now know, the admonition is warranted. Leroy is cocksure and brushes off the warning. As he starts to drive away, Molly comes out on the porch to watch him longingly. But then she jumps in the car and demands to go with him. Out on the road, Leroy is flying down two-lane rural byways that are barely paved and not even striped. Molly asks where he is going, and he tells her they’re heading to Birmingham. She wants to know how long it will take, and his reply is to stop talking. Over the CB radio, Leroy talks in code to a man in an office, and that signal is picked up by the two guys from the beginning of the movie. Meanwhile, Molly is complaining about having to go pee, but they have bigger problems. Three carloads of goons are setting Leroy up for the takedown. Leroy evades them by driving through the brush and bushes, yet he creates another problem in his escape: Molly has peed herself.

That evening, they arrive at Simon’s Auto Shop. A grease monkey kid lets them in and banters a bit with Leroy, while Molly changes out of her wet clothes into some coveralls hanging nearby. Leroy tells her to wait around while the car is being worked on, but she disobeys and follows him to a nearby night club. Here, we get an overview of a redneck night out. A country band is playing, and people are dancing. Soon, Leroy calls for a redhead named Lu Anne, who has several men hanging around her. She is all made up and wearing a skimpy pants suit. She and Leroy begin to dance and kiss, until a man comes out of nowhere and snatches Leroy up. They begin to fight, and in doing so, the other man punches Molly in the face. This brings a third guy into the fight, and they all go at it. Until Leroy escapes to the parking lot, with Molly coming out right after him.

After this, it is time for our country boys to have a meeting of the minds. They have to figure out what to do about Larch and his “syndicate.” They have gotten more brazen with the attempt to kill Leroy, so something must be done. The five men who’ve gathered all agree that machine guns are the answer. One claims to have no money, but Leroy quickly corrects him by saying that he has thousands of dollars buried in tin cans all over the place. Pennyrich adds a Southern touch to the conversation but reminding them, “We place our faith in the Lord and our trust in them guns.” Soon, they scatter to set themselves up to go to war.

The next few scenes move quickly among the various aspects of the plot. Out on a dirt road, we see the sheriff with a man who must be his superior or boss. He is being told that they’ve received word about the possible use of machine guns, which means that the goofy little country sheriff will be off the case. He insists that he can handle it, however, by knowing Pennyrich better than anyone. In another area, Molly is skinny-dipping in a pond, and Leroy shows up to request that she rethink his percentage, considering his level of risk. After their conversation, he walks off with her clothes. Back at the house, the sheriff shows up in women’s clothes, claiming from a distance to be a traveling evangelist named Sister Bessie, but Pennyrich sees through the disguise and sets him up to be had. Unfortunately, Pennyrich’s plan to scare the sheriff goes too far, and his car goes off a hillside, crashing into the brush. Pennyrich is scared that he has killed him, but the sheriff secretly scurries into the woods and escapes before the car blows up.

Back at the house, everything is coming to a head. Leroy is drinking on an old seat outdoors when Molly finds him. She made it home from the pond and has put on her silk nightie. The two begin to fuss and fight, which takes them into the house, where Leroy forces himself on her. To her surprise, he stops short of assaulting her and leaves the house laughing. Molly grabs the shotgun and follows him to his little place in the garage, barging in the door to shoot him. Leroy tells her either to admit that she wants him, or to lie to herself and say she doesn’t then shoot him. She answers his dare by pulling the trigger, but he has already taken the shells out of the gun. Half-angry and half-lustful, she storms across the room and jumps on top of him. It is in this awkward way that the two finally get together.

Later, after they’re done, Pennyrich shows up drunk as a skunk. He is having remorses about killing the sheriff, which he didn’t really do, and will no longer be making moonshine. After he leaves the little shack, rambling like a mad man, Leroy tells Molly that they will have yet another new deal. With Arthur gone, she will have to start working at the still with him.

Out at the still, Molly is quickly tired of working. She tries to lay down, but Leroy drags her off the a stack of feed sacks by her feet. As they tussle, she attempts to hit him, and he warns her, “You’re about to eat your teeth.” It keeps on going, so he punches her in the face, knocking her to the ground, and then picks her back up and exerts his authority. From there, he is a tough boss, kicking Molly in the seat of the pants and yanking her by the arm.

The final scenes of Bad Georgia Road resolve the little bit of tension that remains in the story. After being forced by Leroy to drink some of the moonshine, Molly is falling down drunk. But they’ve got a run to make. She insists on going with him. Out on the road, we see one last attempt by the syndicate guys to trap Leroy. And once again he evades them, leaving them in a field just like he did at the beginning. Right before the credits roll, Leroy and Molly are still negotiating their percentages, arguing over how to split the money.

Watching movies like this one reveals why Smokey and the Bandit was more successful than most in this genre. Audiences in the 1970s – and audiences today – can enjoy an outlaw story, a tale about two good ol’ boys eluding the police, generally having a good time doing it, even a story that includes a little love component with a pretty woman added in . . . but audiences are not so fond of men who never bathe, who attempt rape, and who rely on domestic abuse to maintain control. Because of those harsher elements, it’s hard to say what we’re supposed to take away from this story. Molly arrived in Alabama as a citified young woman with a professional career and a gay best friend, then she ends by becoming the girlfriend of a greasy redneck moonshiner who recently punched her in the face. Are we supposed to understand that Leroy showed her the error of her ways or that she likes this new life better? Hopefully not. But there is no moral judgment here, definitely not against Leroy. As for other male characters, they get off scot-free, too. Darryl just abandons Molly without a word, even stealing her car, and the Southern lawyer DePue tricks an unsuspecting woman and cheats her out of her inheritance. But this seems to be where Molly wants to stay. What the hell . . . ?

As a document of the South, Bad Georgia Road combines several elements that are or have become well-known. One is the Simon Suggs figure, that character in the lore of the Old Southwest made famous by Johnson Jones Hooper. Simon Suggs was the early nineteenth century’s backwoods trickster who, in each tale, outsmarts educated and urbane people through a mixture of wily cunning and extreme naiveté. He is the embodiment of a kind of humorous wit that has pervaded Southern culture in works ranging from the novels of Mark Twain to the TV show The Dukes of Hazzard. It is easy to see features of Suggs in both Pennyrich and Leroy. Another element is a generalized Southern locale that gives few or no specifics. There are only a few references to the story being set in Alabama; one is Leroy’s statement that their destination is Birmingham, but when Molly asks how long the trip will take, he doesn’t answer. So how far from Birmingham were they? It’s important to point out here: this movie definitely wasn’t filmed in Alabama. The landscape is obviously California; when they arrive in “Birmingham,” there are palm trees. Just sayin’ . . . Moreover, there’s the title: Bad Georgia Road. There really is an Old Georgia Road in central Alabama, as well as an Atlanta Highway. But not once did anyone in the movie reference such a road that would lead to Georgia. I understand the temptation to put the story in “the South,” but a particular setting matters. South Georgia is not like north Alabama, which is not like the Mississippi Delta, which is not similar to coastal Carolina. I realize that exploitation films are not known for their accuracy, but many Americans do take their conceptions of what the South is from films.

As a last word, other components of this movie are also just plain odd. For example, not one black person appears in this film at all. I realize that it is a racist trope to throw in a token black character or two, usually in a minor role or as extras, but the absence of black characters is notable in a movie that is supposed to be Southern. Second, it was hard to tell whether it was hot where they were. There were scenes when Leroy was in a t-shirt while Pennyrich was in two shirts and an overcoat. And neither man was sweating or shivering. In Alabama, heat and humidity matter. Beyond that, in some parts but not all, the steering wheels of cars are on the right side like they are in Europe, and at about the fifty-minute mark, the sign for Simon’s Auto Shop is clearly backwards. For a movie that centers on cars and driving, it made me wonder what was going on with that. I’ll give them this: the film was a cheaply made drive-in feature, so it is what it is.

March 22, 2025

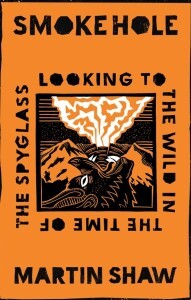

Reading: “Smokehole” by Martin Shaw

Smokehole

Looking to the Wild in the Time of the Spyglass

by Martin Shaw

My rating: 5 out of 5 stars

Somehow the necessary things aligned to land Martin Shaw’s Smokehole in my hands. This isn’t a book I would have normally chosen. But about a year ago, I watched a documentary Woodland Dark and Days Bewitched about folk-horror movies and was for a while ensconced in the subject of the folk. These films reminded me of studying archetypes in literature during my days as an English major, then as I dove in, they yielded a larger interest in the subjects of folktales and folklore (albeit in a half-baked/novice/hobbyist kind of way). It was subsequent searches for books on these subjects that led me to this one, which was published by Chelsea Green.

The main part of Smokehole, which is framed by an introduction and conclusion, is divided into three sections that each contain a folktale and a commentary on it. The first tale is about a girl whose hands are cut off after her father inadvertently promises her to a mysterious man he meets in the woods. The girl then goes on a journey that leads her into the woods, into womanhood, into a marriage, and into motherhood. Using the tale, Shaw teaches about the dangers of lies and greed, as well as the ways one can find support and recovery. In the story, the wilderness – in this case, the forest – is a multifaceted place whose remarkable characteristic is uncertainty. It is where the father meets the trickster with a half-obscured face, and after the trickster has altered their lives, it is where a distraught daughter goes alone to escape. Later, once the girl has grown into a woman and had a child, she must flee from danger by going back into the forest but, the second time, meets a group of older women who love and support her and her child. Shaw’s message centers on the idea that, throughout our lives, we may have to leave our comfortable lives and venture into uncertainty, where we will not always find the same things.

The second tale has elements of the parables of the prodigal son and of the good Samaritan in the Bible. Here, a young man takes his inheritance early and leaves home, but this time he loses everything not through self-indulgence but by helping someone. As a naive traveler, he finds a dead body on the road to town, hoists it onto his back, and tries to find the man’s family or friends so they can give him a funeral and burial. This story allows Shaw to comment on unexpected outcomes and burden sharing. We see a scenario similar to the one that Jesus used in his story about the Samaritan, who receives help from the person most wouldn’t expect to give it. A young man passing the dead body of an unknown person would have no reason to seek a decent burial for a stranger, much less be willing to pay for one, but in this tale he does. Once again, there are lessons about how life may not lead us where we think it will.

In the third tale, we meet a woodland hunter who lives with his mother. Normally, the hunter would use his skills to keep them fed, but one day he finds that he can’t. In his search for prey, though, he encounters four animals and accepts promises of future aid from them in exchange for mercy. Although he and his mother are starving, he looks to the possibilities in the future rather than the needs of the present— delayed gratification. Later, he uses their assistance when he is trying to win the hand of a princess by outdoing a riddle/challenge. In this last one, we encounter the spyglass, which the princess uses as an all-seeing eye, and Shaw likens this spyglass to the internet. Shaw uses the metaphor to share his thoughts on how we have let a powerful tool become a thing that we yield to, rather than a thing we control.

I’ve read Smokehole twice since getting a copy last summer. It’s not a long book at all, and its style is conversational, which makes for easy reading. Moreover, the author offers some valuable lessons here, perhaps chief among them that our lives may not turn out as we planned but may instead involve a journey with many twists and turns. In this reading, we don’t get an technical lesson in folktales as a genre, how they’re crafted, whether they’re from, etc. Instead we are given a practical lesson in their uses. We experience folktales in action, which illustrates that life in any age may involve lies, deceit, regret, pain, mistakes, misunderstandings, resolutions, support, compromise, and joy. Even in our age of constant surveillance and material convenience, Shaw reminds us, if we look to what has worked for human beings longer than recorded history has documented us, we can find more solace and comfort than if we place our faith in modern rhetoric and in technology. I couldn’t agree more. Smokehole reminds readers that, no matter how we try to tame life, it remains wild.

March 15, 2025

The Open Submissions Period for “Nobody’s Home” begins in a month!

Starting April 15 and ending June 15, I will be reading and considering submissions of creative nonfiction to expand the Nobody’s Home anthology. All submitting writers should read the guidelines thoroughly, then send a query and wait for a response about whether to send the work. I am particularly interested in works about or set in the states of Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Texas, as they are currently underrepresented in the anthology. Works accepted during this time will be published in August 2025.

Starting April 15 and ending June 15, I will be reading and considering submissions of creative nonfiction to expand the Nobody’s Home anthology. All submitting writers should read the guidelines thoroughly, then send a query and wait for a response about whether to send the work. I am particularly interested in works about or set in the states of Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Texas, as they are currently underrepresented in the anthology. Works accepted during this time will be published in August 2025.

This year’s Open Submissions Period is the sixth for Nobody’s Home. In the project’s inaugural year, the first three Open Submissions Periods were held in the latter half of 2020 and the first half of 2021. Subsequently, in 2022 and 2023, unsolicited submissions were read in the spring, with accepted works published each summer. Invitation-only submissions periods have been held in the fall of those two recent years.

Submissions of reviews and interviews will continue to be accepted during this time. Again, anyone considering a submission should read the guidelines thoroughly before sending a query.