Foster Dickson's Blog, page 5

January 4, 2025

Sharing the Good Stuff: “Seeking Common Ground,” on NPR

NPR’s new series “Seeking Common Ground: Conversations Across the Divide” began in November 2024, and its segments now cover subjects ranging from talking to family members with differing views to singing in a choir with diverse individuals. The segments are fairly brief, running from about 4-1/2 to 8 minutes, which means that they offer food for thought more than answers. (If you like answers, try their Life Kit instead.)

Being a Southerner who was raised Baptist, I was particularly interested in “Gospel-focused racial reconciliation in the Deep South.” The story discusses people coming together in Mobile, Alabama to deal with its history.

https://www.npr.org/player/embed/g-s1-35535/nx-s1-5255851-1

January 2, 2025

Dirty Boots: The Grandma in the Louisiana KFC

When I was child in the early 1980s, my family drove across the country to see my uncle in Phoenix, Arizona. We left Alabama one summer morning, and our first stop was for lunch at a Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant in Louisiana. Behind us in line was a grandmother with probably half-dozen children around my age. After we ordered and sat down to wait, the old lady began calling the children up one-by-one to order. And one-by-one they came, then came back after hearing what another kid was getting, and then did it again, and again. My family got our food, ate, and were leaving, and that poor woman – I can still picture her – was leaning on the counter, face in her hands, with those kids hollering at her about being hungry.

What I saw that day more than forty years ago is a good metaphor for what I see today among our country’s center-left and progressive-left. In terms of elections, Americans mainly have two choices on most ballots, even though we’re a people of broad and diverse interests and beliefs. For right-wingers and conservatives, the choice is clear, if not always desirable. Over the last thirty years – since Newt Gingrich in the mid-’90s then Dubya in the 2000s – the Republicans have coalesced their “base” by solidly organizing about one-third of American voters around a group of ideas that connect faith, family, guns, law and order, and the economy to form a definitive concept of national identity. (Millions of those voters live in the South.) For those of us whose concerns include workers’ rights, public education, healthcare, voting rights, racial justice, income inequality, gender equity, LGBTQ rights, prison reform, the arts, and/or the environment, we must find a political home within the battle royal of competing interests that is today’s Democratic Party.

What I saw that day more than forty years ago is a good metaphor for what I see today among our country’s center-left and progressive-left. In terms of elections, Americans mainly have two choices on most ballots, even though we’re a people of broad and diverse interests and beliefs. For right-wingers and conservatives, the choice is clear, if not always desirable. Over the last thirty years – since Newt Gingrich in the mid-’90s then Dubya in the 2000s – the Republicans have coalesced their “base” by solidly organizing about one-third of American voters around a group of ideas that connect faith, family, guns, law and order, and the economy to form a definitive concept of national identity. (Millions of those voters live in the South.) For those of us whose concerns include workers’ rights, public education, healthcare, voting rights, racial justice, income inequality, gender equity, LGBTQ rights, prison reform, the arts, and/or the environment, we must find a political home within the battle royal of competing interests that is today’s Democratic Party.

While my beliefs haven’t changed and what I stand for hasn’t wavered, it is my humble opinion that today’s Democratic Party is struggling for the same reason that grandma in the KFC did. As a GenXer who grew up working-class in the South, I learned a valuable lesson from our family dinners, including the one in that KFC, and it applies to the current political dilemma. Back then, a meal was put on the table, and I could eat what was there with my family, or not eat at all. In 2024, the national Republicans did with Donald Trump what my folks did with meals. And it worked in our election system. Republicans in Alabama have done this for years, and they’ve held every statewide office and a supermajority in the legislature since 2010. For a political party to have earned that level of support for that long, you’d think they were doing some A++ public administration. They’re not. Republicans are winning elections by putting up recognizable candidates with a cohesive message against a cacophony of unrelated, competing, individual interests represented by a party that squabbles internally and often doesn’t field candidates in state and local races.

I was already feeling this when, in mid-November, I read an essay in The New York Times that asked, “When Will Democrats Learn to Say No?” In it was this:

Democrats cannot do this [win elections] as long as they remain crippled by a fetish for putting coalition management over a real desire for power. [ . . . ] Achieving a supermajority means declaring independence from liberal and progressive interest groups that prevent Democrats from thinking clearly about how to win. Collectively, these groups impose the rigid mores and vocabulary of college-educated elites, placing a hard ceiling on Democrats’ appeal and fatally wounding them in the places they need to win not just to take back the White House, but to have a prayer in the Senate.

What he’s saying is: it’s time to stop worrying about pleasing every single person. It might be time to acknowledge that a majority could vote for a candidate even when many have to hold their noses and pick their lesser of two evils. Getting candidates into elected offices to enact policy seems to be the goal of the whole thing. I don’t have the insider’s view to know who or what might coalesce a center-left and progressive-left “base,” but I do know this: It’s time to start thinking about winning.

December 30, 2024

A Deep Southern, Diversified & Re-Imagined Recap of 2024

2024 was a very different year for this middle-aged writer, editor, and teacher. After the release of Faith. Virtue. Wisdom. in October 2023, I had no full-length project that I was working on— for the first time in twenty years. But I restarted the Dirty Boots column, wrote several long-form posts for Welcome to Eclectic, and Nobody’s Home has been moving steadily along. My job at the college as the Academic Writing Advisor has also settled in, and I taught some 200-level lit survey classes in the fall. After we announced the winners of the Fitzgerald Museum’s sixth annual Literary Contest in March, I turned the contest back over the museum director. It has been the quietest year for my writing in a long time. Now, as 2024 comes to a close, here is a recap of what has been published on the blog (and a few things on Nobody’s Home) this year:

Posts

Sharing the Good Stuff: Bipartisanship and Problem-Solving, on Meet the Press (December)

Dirty Boots: Drivin’ N Cryin’ @ Saturn Birmingham (December)

Dirty Boots: 1994 (November)

The First One in a Long Time: A Poem in Boudin (November)

The Work, As 2024 Winds Down (October)

Dirty Boots: Confederates in the Attic, Re-Visited (October)

A Deep Southern Throwback Thursday: The WAPX Shootout, 1974 (October)

Sharing the Good Stuff: A Hopeful Take on Climate Action, from PBS News Hour (September)

Dirty Boots: Backstories (August)

A Legitimate Educational Interest (August)

Another Batch of New Works in Nobody’s Home (August)

Dirty Boots: “Democracy in America” (July)

The Open Submissions Period for Nobody’s Home ends today. (June)

Conrack, 50 Years Later (June)

Dirty Boots: Just Like Jim Stark’s Blues (June)

Dirty Boots: Disturbing the Peace (May)

Throwback Thursday: The Community Legacy Project, 2015 (May)

Dirty Boots: A Joyous and Inexplicably Necessary Thing (May)

The 2024 Open Submissions Period for Nobody’s Home (April)

Tuskegee, Before and After (April)

Throwback Thursday: The Haiku Year, 2004 (April)

Dirty Boots: Who Knows . . . (March)

Dirty Boots: Shorty Price (February)

Dirty Boots: The Third Third (January)

50 GenX Movies You’ve Probably Forgotten or Never Seen (January)

Eerily Prescient but Also Mistaken (January)

and published in “Groundwork,” the editor’s blog for Nobody’s Home:

Stone, A Rock, and Free Posters: A Rumination on Religion and Politics (December)

Hold Steady and Stick Together: A Rumination on School-Choice Vouchers (January)

Reading

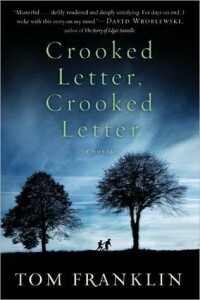

Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter by Tom Franklin

The Shadow of a Great Rock by Harold Bloom

Loving Our Enemies by Jim Forest

The Gospel of Life by Pope John Paul II

My review of From Every Stormy Wind that Blows by S. Jonathon Bass (July)

My review of Glass Cabin by Tina Mozelle Braziel and James Braziel (July)

and published in “Groundwork,” the editor’s blog for Nobody’s Home:

Getting Right with God by Mark Newman (2001)

Red State, Blue State, Rich State, Poor State by Andrew Gelman, et. al. (2008)

Southern Politics in the 1990s by Alexander P. Lamis (1999)

Watching

The Watchlist Lives! (The Great Watchlist Purges, Part . . . whatever) (July)

and published in “Groundwork,” the editor’s blog for Nobody’s Home:

Review: Lost Child (2017) (October)

Watching How the Monuments Came Down on PBS (June)

Review: My Cousin Vinny (1992) (May)

Watching The Harvest from American Experience on PBS (March)

Southern Movies

Stroker Ace (1983)

The Legend of Billie Jean (1985)

Incoming Freshman (1979)

The Beast Within (1982)

A Love Song for Bobby Long (2004)

Shanty Tramp (1967)

Murder in Coweta County (1983)

Beasts of the Southern Wild (2011)

Read more from past years:

A Deep Southern, Diversified & Re-Imagined Recap of 2023

or A Deep Southern, Diversified & Re-Imagined Recap of 2022

or A Deep Southern, Diversified & Re-Imagined Recap of 2021

or A Deep Southern, Diversified & Re-Imagined Recap of 2020

December 23, 2024

Sharing the Good Stuff: Bipartisanship and Problem-Solving, on Meet the Press

This Meet the Press segment from last Sunday has two US senators – one from Georgia, the other from Oklahoma – discussing the work of Congress, and how it should work. It’s not necessary to agree with everything they say here, and even they point that out. But there was something good and hopeful about this conversation.

December 18, 2024

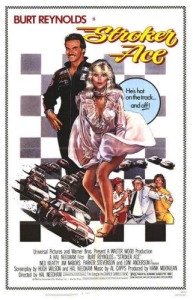

Southern Movie 74: “Stroker Ace” (1983)

The 1983 racing-themed comedy Stroker Ace tells the story of a driver who has allowed himself to be roped into a sponsorship contract that he desperately wants out of. The main character is a fun-loving womanizer who can’t seem to act right, so he keeps losing his sponsors. Unfortunately for him, there is a regional fried chicken chain whose extremely annoying owner wants badly to have a race car with his business’s name on it. Directed by Hal Needham and starring Burt Reynolds in the title role – this was the same winning combo in Smokey and the Bandit – the film also features one of Reynolds’ regular co-stars Ned Beatty (Deliverance, White Lightning) as well as singer-actor Jim Nabors, football great Bubba Smith, and doe-eyed beauty Loni Anderson.

Stroker Ace opens in black-and-white, and we see Stroker and his friend Doc as boys in the rural South. The bicycle they have is messed up because Stroker tried some act of daring on it, and they are stranded by the roadside. Soon, Doc’s dad shows up in a pickup and gives them a ride. But he’s on a moonshine run, and the revenuers spot him! They take off then and speed along a two-lane blacktop before veering onto dirt roads. Stroker keeps taking the rearview mirror fix his hair, but Doc’s dad needs it to keep an eye on the cops behind him. The whole scene is playful, and the action is augmented by the movie’s theme song by Southern rock great Charlie Daniels.

As that scene fades out, a modern one fades in, and we see an adult Stroker Ace fixing his hair in the rearview mirror that same way. He is driving in suburban traffic this time, and soon we see that his mechanic Lugs Harvey (Jim Nabors) is hanging out of the passenger door to counterbalance the weight of the car, which has a front wheel missing. Not to be deterred, he orders Lugs to lean out further so he can make a turn. Meanwhile, the announcer is introducing the drivers who are about to start racing in the Daytona 500. These scene alternates between the raised stage where drivers wave at the gathered crowd and Stroker flying through the parking areas and knocking over pylons. He eventually lands in a spot and jumps out just in time to be introduced. Hamming it up, he smiles for the cameras, ignores the complaint of his angry sponsor, then has the entire stands for no reason before leaving the mic to speak to the good-looking women there. Two of them rebuff his advances because he walked out on them on previous occasions, but the third seems to be a newcomer. We get the feeling that this guy is a mess.

Next, we meet the other characters one by one. Aubrey James is the brash young driver who hates Stroker Ace. James wants to dethrone the great one, the guy who wins most of the time. Mr. Catty is Stroker’s current sponsor – Zenon Oil – and he is aggravated with his driver from the first moment we see him. Next, Clyde Torkle (Ned Beatty) comes bumbling through, smiling and shaking hands with whoever doesn’t escape. Clyde owns a chain of friend chicken restaurants, The Chicken Pit, and he wants a car in the races desperately. Finally, we get a glimpse of a pretty blonde (Loni Anderson), who is standing in the pit looking around when some guys with an air compressor blow her dress up around her neck. She catches Stroker’s eye just before that, but here comes Clyde Torkle to interrupt. With his very large chauffer Arnold (Bubba Smith) in tow, the pudgy little loudmouth accosts Stroker as he tries to go catch up with the blonde mystery woman as she runs off. The chicken man has heard that Stroker is having trouble with his sponsor and wants to step right into that role. Stroker is less than enthused about the idea, but Clyde reminds him that he only ever does one of two things: crash or win.

The race begins, and we see Clyde and Arnold in the press box. Clyde remarks on the 120,000 “fried chicken junkies and God knows who many more watching on the TV,” but Arnold is ignoring him. He then moves across the room and speaks to that blonde woman we saw earlier in the pit. She is his new employee, and he’s ready to leave with her. She doesn’t want to go though, and when he suggests dinner and champagne, she reminds him that she doesn’t drink and that she’s a Sunday school teacher in her spare time. Clyde is thwarted once again. Out on the track, Stroker is thwarted too, by Aubrey James who causes a crash that puts him out of the race.

On the highway afterward, Stroker is driving Lugs and Mr. Catty to the hotel, while the cigar-chomping sponsor fusses and complains. Stroker has wrecked his race car, wrecked his rental car, wrecked his hotel room . . . the sponsor is sick of it. So Stroker plays nice and offers to go in, get their keys, and drive the irate man around to his room. It looks for a moment like Stroker will behave, but instead he arranges for a nearby cement truck to douse the grouchy old man with gray slush while a crowd of bystanders laugh and mock him.

Now, Stroker has no sponsor. But he hasn’t changed a bit. Sitting in the bars with Lugs, he sees that a woman he was with in a previous year, and she is now hanging on Aubrey James, who won the race earlier. When he can’t coax her away with flirty gestures, he feigns an injury by bumping into chair then limping out of the room. She then runs after him sympathetically while Lugs rolls his eyes.

Back in the pit, now at the Atlanta 500, Clyde Torkle has a car already waiting and a thick contract printed out. Lugs really doesn’t like what he sees happening, but happy-go-lucky Stroker signs the hefty contract . . . without reading it. And that will be the conflict moving forward, which begins right away. When Stroker climbs onto the stage to be introduced, he finds that he is now being referred to as “the fastest chicken in the South.” Chagrined and baffled, he asks why and is told that it’s written on his car! The other drivers and mechanics begin to cluck at him and laugh. Stroker doesn’t like it, but it’s in his contract. Clyde is all smiles now that he has gotten what he wanted. And even better, Stroker wins the race!

Back in the pit, now at the Atlanta 500, Clyde Torkle has a car already waiting and a thick contract printed out. Lugs really doesn’t like what he sees happening, but happy-go-lucky Stroker signs the hefty contract . . . without reading it. And that will be the conflict moving forward, which begins right away. When Stroker climbs onto the stage to be introduced, he finds that he is now being referred to as “the fastest chicken in the South.” Chagrined and baffled, he asks why and is told that it’s written on his car! The other drivers and mechanics begin to cluck at him and laugh. Stroker doesn’t like it, but it’s in his contract. Clyde is all smiles now that he has gotten what he wanted. And even better, Stroker wins the race!

Later in the hotel lobby, one of the women that Stroker snubbed in Daytona is looking for his hotel room in Atlanta. Lugs gives her the info and is soon approached by Elvira, Mistress of the Dark, in a cameo. Up in Stroker’s room, that mystery blonde – her name is Pembrook Feeney – is coming there, too. But not for the things that groupies want. She has a marketing plan to discuss with Stroker and finds that he has been occupied. The other woman is leaving, and Stroker was trying to get in the shower. Against her better judgment, Pembrook comes in and gives Stroker a quick overview of the marketing plan that’s he’s a big part of. He isn’t enthusiastic about this, until he finds out that she will be traveling with him.

Their first stop is at a small town store’s opening. Stroker is stretched out the back seat of a convertible while Pembrook drives and Lugs sings in the front seat. They banter a bit, Striker jibing Lugs about his odd style of singing, and the soon the trio arrives. Stroker is expecting to see a huge crowd but only a few people are gathered there. And none seem interested in him. Disgruntled, he gets out and cuts the ribbon while Clyde beams a big smile nearby.

What follows is montage of these kind of appearances: TV, radio, and on-site. The frustration is evident on Stroker’s face, while Lugs and Pembrook put on happy faces. The final insults are a TV commercial that has Stroker in a chicken suit. This is followed by a realization: Stroker can’t get out of the contract, but he can be fired. So in a pre-race gag meant to incite a firing, Pembrook drives him into the race in Talladega on a tractor, sitting a big egg nested in the trailer behind it. Fans boo, and even Clyde knows this one was a bad idea. He looks to be a man who has turned in a hero into a joke. But it doesn’t work. Clyde thanks him instead, leaving Stroker and his friends to try something else. So he is left to drive in a car that he has repainted to look like a plucked chicken. This time, he doesn’t win. The engine blows out mid-race.

Meanwhile, the plot thickens with Pembrook, as Stroker does is best to woo her into submission. He invites her to his hotel room and has champagne, even though she has told him that she doesn’t drink. (He lies to her and says that it is nonalcoholic, ordered special.) However, his plan is thwarted by the arrival of Lugs, who just thought he’d stop by. Sensing that he won’t be getting where he wants to be, Stroker goes out in the hallway to find Aubrey and some other racers playing on rolling carts. Stroker then sneaks up behind Aubrey, gets him moving before he knows who is pushing, then send him through a glass wall into the swimming pool.

The movie now at its halfway mark, about 45 minutes into the 95 minutes total. We move from the rolling cart prank to the hotel bar, where Stroker has a small group of men come to his table to laugh at his chicken-themed racing operation. He takes it pretty well, but soon starts a massive free-for-all brawl by punching a few of the guys. Though Stroker does get knocked around a bit, Lugs has his back, and he even gets to sucker punch Aubrey James.

After that barroom situation, Pembrook goes to see Clyde in his hotel room, to see if he will let Stroker out of his contract. Of course, he says no, then begins to get the picture that Stroker and Pembrook are involved. Not one to read the social cues, Clyde decides that Pembrook must not be as virginal as she claimed, and so in his boxers and stained tank top, he proceeds to see if he can get a little bit of action. Sadly for Clyde, it doesn’t work that way, and he gets kicked in the balls. Pembrook resigns as she stomps, and he replies, Good!

The next morning in the pit, Clyde storms onto the scene with some choice words to say to Stroker. However, he is stopped cold by the sight of Pembrook’s legs sticking out from under the car. He explains vaguely to Stroker that he had to fire her last night, a statement she objects to. Frustrated, the chicken man leaves just as he arrived, reminding Stroker that he may have fired Pembrook but he will never fire him. That evening, the men are going to the opening of a Chicken Pit in separate cars, and Stroker uses some fancy driving to lose them. Arnold ends up putting Clyde’s red Cadillac in the lake right in front of a law enforcement officers’ picnic.

At the event, Stroker is in a little toy car where people can turn him upside by hitting a target with a baseball, like a dunking booth would. Among the people in the small crowd are his old friend Doc and Doc’s father. Once Stroker is done with his obligations, the group sits down to a picnic where they can talk. Doc is now an actor taking on small roles and his father had taken to making jewelry . . . out of pigeon droppings. The scene fades out with Doc singing an old Nat King Cole song . . .

. . . and that’s where we pick up, later that evening, as Stroker and Pembrook are slow-dancing to the real tune. And in that romantic place and time, Pembrook says that she wants to go to bed with Stroker. This is what Stroker has been wanting the whole time! But when he gets to the bedroom where she is, she has passed out. Over the next few minutes we watch as the race car driver hovers over his half-undressed would-be lover, talking to himself in a mental battle over whether he should move forward with it anyway. Ultimately, the good voice wins out, and he leaves her be. The next morning at breakfast, they have a brief talk about it, and Stroker tells her that nothing happened. She is pleased to point of tears, which is how Lugs finds her. He misunderstands the situation then and goes to find Stroker, who stepped away to make a phone call. While he talking to Doc about a plan to get out of his contract, Lugs punches him in the face for the perceived misbehavior.

Next we see, Doc is sitting Clyde Torkle’s office, pretending to be a representative of Miller Brewing. They want to buy The Chicken Pit, Doc claims. Clyde is thrilled but also not sure whether he wants to sell out. Doc shows him a dollar amount and lays out a few stipulations, one of them being that he’ll fire Stroker Ace because of his “questionable reputation.” Clyde, in his awkward way, tries to figure out what to do, and they agree on Sunday for an answer.

As we come to the last race of the season, in Charlotte, all of the conflicts come together. Clyde must decide whether to fire Stroker, and Stroker must beat Aubrey James to shut him up. After a few minutes of scenes from the race site, Clyde appears in the pit to lay out Stroker’s dilemma. If Stroker wins the race, he’ll be too valuable to fire, and they’ll spend two more years together . . . but if he loses, Clyde will sell out and fire his driver. And Clyde even ups the ante by remarking, “What about it, hot shoe? Ever throw a race before?” Even Arnold the chauffeur is offended. Now, Stroker appears to be in a situation where he can either beat Clyde or Aubrey. He has to figure out how to beat them both.

The final twenty minutes of the movie bounce back forth among the varied aspects of the story. Stroker is out on the raceway, and Clyde is up in his press box. Doc has sent his father to pretend to be the messenger who will take his decision back to Miller Brewing. At first, it looks like Stroker will throw the race, and Clyde is left to sit in his box and ponder over whether to give up on his driver and sell. Lugs is disappointed in his old friend, and Pembrook is, too. Yet, the brash young Aubrey changes Stroker’s mind when he pulls up beside and taunts him, claiming to be number one. Stroker then takes off! He will stay in the chicken business. But Aubrey won’t go down so easy. He tries the same trick we saw earlier in the movie, pushing Stroker into the wall to crash. But this time, it fails, and all he succeeds in doing is causing a huge pile-up. Using the clean-up as a way to take a pit stop, Stroker pulls in, but the jack is broken. They can’t change his tires. However, Arnold is nearby, and in one of the movie’s triumphant scenes, the big man lifts the car so they can get their work done.

Finally, 4:00 arrives, and Clyde sees that Stroker is running in sixth place. He takes off his Chicken Pit jacket and hat, then goes over to Doc’s father and says to tell Miller that he will sell to them. Of course, he knows nothing of what’s happening in the pit. Doc’s dad gets the word to Lugs, who tells Stroker to go ahead and win. As that is happening, Clyde goes to the press and tells them that he is firing Stroker. One reporter asks why he would do such a thing when Stroker is gaining on the leader. A confused Clyde has no idea what is happening. Stroker goes ahead and wins the race, scraping his car over the finish line upside down after Aubrey tries his in-the-wall trick one last time. Over in the winner’s circle, Clyde finds out how he has been tricked when Doc and his dad show up. Even Aubrey mouths to Stroker, “You’re number one.” Everything goes right in the end: Clyde gets duped, Stroker wins the race and gets the girl.

If you’ve read this far, consider showing some love.Stroker Ace is, for the most part, a good-natured comedy for the dudes. Most of the jokes are either guys giving each other a hard time or guys making veiled sexual overtures toward women. Of course, there are fast cars, too. Whether it’s accurate or not, the movie is a madcap look at the NASCAR scene. Several real drivers, like Harry Gant and the late Dale Earnhardt, appear in scenes. To a working-class, white, male Southern viewer in the 1980s, all of this would have been recognizable, lighthearted, and fun. The story is based on the book Stand on It, about – you guessed it – a race car driver with wild tendencies.

It’s worth noting as well that this movie was one in a string of Southern-centric hits for Burt Reynolds in the 1970s and early ’80s. The list starts with Deliverance in 1972, followed by White Lightning in 1973. Then came WW and the Dixie Dance Kings in 1975 and Gator, which was a sequel to White Lightning, in 1976. Of course, Smokey and the Bandit in 1977. The football movie Semi-Tough, which was filmed in Texas, was also in 1977, and Smokey and the Bandit II came out in 1980. Before this movie, Best Little Whorehouse in Texas was released in 1982. Stroker Ace capped off the stretch.

Yet, not everyone was a fan. The late Roger Ebert opened his 1983 review of the movie with this:

Burt Reynolds used to make movies about people’s lifestyles. Now he seems more interested in making movies that fit in with his own lifestyle. “Stroker Ace” is another in a series of essentially identical movies he has made with director Hal Needham, and although it’s allegedly based on a novel, it’s really based on their previous box-office hits like “Smokey and the Bandit” and “The Cannonball Run.”

To call the movie a lightweight, bubble-headed summer entertainment is not criticism but simply description. This movie is so determined to be inconsequential that it’s actually capable of showing horrible, fiery racing crashes and then implying that nobody got hurt. The plot involves a feud between two NASCAR drivers (played by Reynolds and Parker Stevenson) who specialize in sideswiping each other at 140 m.p.h. in the middle of a race. I don’t think that’s a very slick idea.

His criticisms are fair, but I doubt if Needham and Reynolds were trying to make high art. They were making a movie for the kind of people who liked their movies— big deal! But Ebert’s opinion must have resided among the majority of movie industry folks. Looking at the Film Affinity website, they share four excerpt-blurbs from TV Guide, The Miami Herald, The Washington Post, and The New York Times that all pan the movie and the performances. Once again, I doubt if the film was made for the critics at those publications. Realistically, most of the reviews call Stroker Ace a “good ol’ boy,” which is basically what the character is, and it’s also why a whole bunch of real-life good ol’ boys liked this movie.

December 3, 2024

Dirty Boots: Drivin’ N Cryin’ @ Saturn Birmingham

Drivin’ N Cryin’ was a staple of our high school and college experience in the 1980s and ’90s. Based in Atlanta, Georgia, the band had formed in the mid-1980s around singer-songwriter Kevin Kinney. The almost-punk song “Scarred but Smarter” became their first hit: “I said nobody said it would be fair / They warned you before you went out there / There’s always a chance to get restarted / to a new world, new life— scarred but smarter.” We could relate. Later in the ’80s, Mystery Road gave our generation the anthems “Honeysuckle Blue” and “Straight to Hell.” Going to see them live – in adjacent Alabama, there were ample opportunities – offered a mix of hard-hitting rock and singalong favorites.

The show I remember best was in 1991, when they played on a double bill with ’80s new-wavers The Fix and a short-lived hair metal band called King of the Hill opening. It was at an outdoor venue called Sandy Creek, which was really just a big open field with a covered stage and a power supply. Going out there for any show was a borderline-dangerous experience, since there was only a one-lane dirt road leading in and out, any security was there to protect the bands, and people brought their own coolers pretty freely. One reason that I remember that ’91 show was because I got hassled and threatened by a group of three or four drunk meatheads whose matching haircuts told me they were on a weekend pass from the military. They appeared out of the crowd, suddenly and for no apparent reason, and declaring that they wanted to kick my ass— mine, in particular. Knowing I was outnumbered and outmatched, and seeing that my friends were pretending not to know me at that moment, I resorted to some quick-thinking and just wanted to know why, specifically, they had a problem with me, out of all the people there . . . Drunk enough to be befuddled by my questions, which they couldn’t answer, they wandered away and didn’t come back. I had saved my own ass, those guys would have stomped me.

The show I remember best was in 1991, when they played on a double bill with ’80s new-wavers The Fix and a short-lived hair metal band called King of the Hill opening. It was at an outdoor venue called Sandy Creek, which was really just a big open field with a covered stage and a power supply. Going out there for any show was a borderline-dangerous experience, since there was only a one-lane dirt road leading in and out, any security was there to protect the bands, and people brought their own coolers pretty freely. One reason that I remember that ’91 show was because I got hassled and threatened by a group of three or four drunk meatheads whose matching haircuts told me they were on a weekend pass from the military. They appeared out of the crowd, suddenly and for no apparent reason, and declaring that they wanted to kick my ass— mine, in particular. Knowing I was outnumbered and outmatched, and seeing that my friends were pretending not to know me at that moment, I resorted to some quick-thinking and just wanted to know why, specifically, they had a problem with me, out of all the people there . . . Drunk enough to be befuddled by my questions, which they couldn’t answer, they wandered away and didn’t come back. I had saved my own ass, those guys would have stomped me.

This time, thirty-three years later, seeing Drivin’ N Cryin’ wasn’t like that at all. I had been browsing Instagram on my phone one night about a month ago and saw a post that the band was playing two nights at Saturn Birmingham. When I told my wife, she said, Buy four tickets! We’d get some friends to go with us. Back in the day, a handful of us would have piled in a car, given five bucks each to some scummy ticket dude, and ended up at a rented hall or in a big field. This time, another couple came up from Pensacola to join us, and we were off to the Avenues North section of Birmingham, stopping first at Avondale Brewing for beers then at Black Market Bar & Grill for dinner. And this time, we were the old folks at the rock show. Thankfully, the old folks in this crowd were not the minority.

Despite our ages, being what they are, the band put on a good show. The opening act played from 8:00 until nearly 9:00, then Drivin’ N Cryin’ came out pretty quickly. (Another major difference between now and then— back in the day, we never knew what time a band would actually play.) In his latter years, Kevin Kinney has foregone the oversized button-downs of the 1990s for a baseball cap and what looked like a track suit. He was also more jovial than I remembered him from the GenX days. Throughout the show, he joked with the audience and took requests, all with a smile. The early numbers they played were mostly ones I didn’t recognize, until “Scarred but Smarter” came about midway through. Kinney joked that he’d play our favorites later, he was playing his favorites first. Of course, by the end there was a barrage that included “To Build a Fire,” “Fly Me Courageous,” and “Straight to Hell.” The crowd had been pretty tame through most of the two-hour set, then perked up near the end and came to something-like-life when Kinney hit the opening licks of “Honeysuckle Blue.” We were as riled up as a bunch of fifty-somethings could get, though a sprinkling of younger folks did a little jumping around among us. (One misguided pair of twenty-somethings started slow-dancing to “Straight to Hell,” and I knew that the lyrics had escaped them. Not exactly a song to dance with your girl to.)

Leaving just after the encore and a kind word of farewell, we skipped the merch table and headed for the car. No squabbles with drunk meatheads this time. The block was pretty quiet by then, which disappointed me since a place like that would have kept us going well into the small hours back in the ’90s. A brewery, some bars, a pizza place, a music venue— almost all dimming the lights and cleaning up before the stroke of midnight on a Saturday? I guess the young people had to call it a night so they didn’t miss out on any threads and reels and shit. Out in the street, I popped open a couple of Good People OktoberFests that I’d packed in my cooler for the ride home. As we rolled through the quiet night toward the interstate, our friend in the back seat played Randy Newman’s “Birmingham,” an appropriate end to a right nice evening.

Some people these days seem miffed by my negative attitude about current music. Sure, there are some good artists now, and there were certainly plenty of bad ones in my day. But I grew up ignoring the bad ones and listening to bands like Drivin’ N Cryin’, alongside classic rock, etc. We were spoiled by the quality of it, and it’s that sensibility that leads me – and plenty of other GenXers – to call bad music what it is. I once heard an interview with Louis Armstrong where he said, in response to a question about genre, that there are only two kinds of songs: good ones and bad ones. Let just end this by saying that Drivin’ N Cryin’ has produced quite a few of the good ones.

November 26, 2024

Reading: “Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter” by Tom Franklin

Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter

Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter

fiction by Tom Franklin

My rating: 5 out of 5 stars

I don’t read much fiction but, every once in a while, a good novel is exactly what I want. I can usually tell that it’s time by the frustration of not being able to settle on a book. It often has something to do with being tired of grading student essays, which I was by early November. When this happens, I find myself bouncing around among the books in my office, various subjects, then picking up a poetry or story collection, thumbing through, nothing looks good . . . it can go on for days. Then I realize it. No more critical reading, no more grading, no more facts and information. It’s time for a story.

It was that inclination that led me into the stacks of the college library where I work. I had stumbled upon John Irving’s The World According to Garp that way last summer and was hoping to stumble on another equally solid find. As my index finger traced the upright spines in the 813s, Tom Franklin’s name appeared. I had met Franklin and his wife Beth Ann Fennelly in the early 2000s, when they came to the NewSouth Bookstore supporting Poachers (his) and A Different Kind of Hunger (hers). So I chose one of his novels from several on the shelf, at random, knowing nothing about it: Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter. The mystery of its contents was heightened by the fact that, being a library edition, the dust jacket had been removed— thus, no sales pitch, no tantalizing summary.

Published in 2010, Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter is set alternately in the late 1970s and early 1980s and in the 2000s. The story, which occurs in rural southeastern Mississippi, follows two characters whose lives intersect and intertwine through a series of events and circumstances that are beyond their control, and even beyond their knowledge. The first of the two, Larry, is white. His father Carl owns the local auto shop, where he is well-known as a man’s man and a great storyteller, though Larry is quiet and squirrelly, and somewhat creepy as a fan of horror novels. When school integration occurs, Larry ends up zoned for the local black elementary and meets Silas, the other main character, when his father picks up the boy and his mother Alice on the roadside one morning. The black mother and son are standing in the cold, and Larry seems confused about why his father gives them a ride. Ultimately, that confusion becomes tension when Larry tells his mother about their regular passengers, who Carl soon picks up daily, and she puts a stop to it. However, the boys continue to play together in the woods around their houses, until daddy Carl discovers their secret friendship and that Larry has given their .22 rifle to Silas. After their friendship is over, Larry and Silas as they are in each other’s vicinity throughout school. Silas becomes a star baseball player, and Larry becomes “Scary Larry,” the weird one that other teenagers avoid. Their lives eventually converge again when an overly flirtatious white girl named Cindy, who lives near Larry, has a fondness for Silas.

The narrative in Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter is told in a nonlinear fashion, so we get these aspects of the overall story as they relate to what is happening to the two as grown men in their early 40s. Larry has remained in their small town of Chabot, taking over his father’s garage, which now has no customers, and living with his mother until she is moved to a nursing home with Alzheimer’s. Despite living his whole life in his hometown, Larry is ostracized over events that involved Cindy when they were in high school. Silas’s path, however, took him away from the town but brought him back to it. Alice had moved them away after the situation with Cindy, then Silas served in the military before returning to Chabot to become the constable, a job that entailed mostly directing traffic and giving speeding tickets. What restores the connection between Silas and Larry is the disappearance of another local girl, which reignites suspicion about “Scary Larry,” whose name was never cleared.

Tom Franklin does an excellent job in the novel of building a tense narrative within the framework of the small-town South in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The portions of the story that deal with their boyhood are prime examples of Generation X’s experiences with integration, at school and in the community. The more modern portions address the current quandaries facing small-town Southerners, like diminishing small towns, inadequate municipal budgets, and the struggles of local businesses. We also have the Faulkner-esque quandary a la Quentin Compson: the past is not dead, it’s not even past. (I won’t go into why I say that, because if I do, I’ll ruin the story for someone who hasn’t read it.)

Last but not least, one thing that I particularly liked was Franklin’s use of kudzu imagery, which I took to be an extended metaphor. Maybe I’m being too much of a literary critic, instead of an ordinary reader, but knowing what I do about kudzu, it’s an excellent metaphor for modern life in the small-town South. Kudzu has no agricultural value but it takes over everything, slowly. It never stops moving and expanding, and it winds itself around anything until what is underneath its tangled vines becomes virtually invisible. This stuff is all over the rural South and can’t be ignored. Throughout the novel, characters were looking out a car window or out across the land at kudzu. It happened too many times to be coincidental. If Franklin did this on purpose, creating visual symbolism, bravo. If he didn’t . . . well, bravo anyway.

November 21, 2024

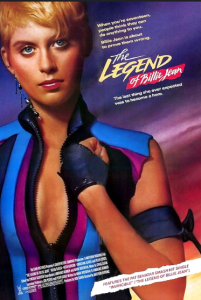

Southern Movie 73: “The Legend of Billie Jean” (1985)

Set on the Gulf Coast of Texas in Corpus Christi, 1985’s The Legend of Billie Jean was optimal Generation X and very Southern. The story centers on a small group of teenagers who go on the run from the police after one among them shoots a local store owner with his own gun. Billie Jean Davy, for whom the film is titled, and her younger brother Binx have been struggling against the bully Hubie Pyatt, who has damaged Binx’s scooter as well as his face. But when Billie Jean goes to Hubie’s father to get money for scooter repairs, the man has an arrangement in mind that would have her giving him sexual favors in return for small, incremental payments. When Binx walks in on the elder Pyatt trying to force her into compliance, he has the gun that he found in one of Pyatt’s drawers. Directed by Matthew Robbins and starring Helen Slater and Christian Slater, The Legend of Billie Jean offers story that is one part crime drama and one part generational struggle, playing out on Southern beaches during a summer in the mid-1980s.

The Legend of Billie Jean opens with a small scooter in a garage, and we see a young teenage boy rolling it out. He’s wearing shorts and a denim vest. A radio DJ’s show is playing over the scene as the boy goes into the yard of the South Texas trailer park to pick up a young woman who is getting dressed in the yard. She pulls off her shirt behind a wooden fence and puts on a floral print dress. We understand that they are a younger brother Binx (Christian Slater) and older sister Billie Jean (Helen Slater) as they hit the two-lane highway on the scooter. Soon, though, they pass a gas station and catch the attention of a carload full of young men in a convertible muscle car. They jump in and begin to chase the scooter, catching up easily. On the highway, where the waterway runs alongside, the teenage boys taunt the pair. Arriving at a roadside drive-in, they get out of the car, and their ringleader Hubie makes sexual overtures at Billie Jean. Yet, Binx halts the advances by pouring a milkshake on his head and pulling away.

The riders soon come to a swampy little swimming hole, where they strip down to their bathing suits and take a dip. Billie Jean is in a bikini bottom and cutoff tank top (which is now an iconic image from the film.) The little brother Binx warns his sister to check the water for alligators before diving, and she laughs him off. Then the water swirls and thrashes before going quiet, and Binx jumps in to save his sister . . . who comes up laughing at him. After their laugh, Binx and Billie Jean lie on floating platform in the sun, and Binx asks to hear about Vermont, again. They wonder at a life without severe heat. As they’re luxuriating, the real threat arrives. The carload of boys has found them. Hubie gets out and begins to manhandle the scooter. The brother and sister swim across the lake to stop him, but Hubie easily throws Binx on the ground and drives away on the scooter, covering Binx with dirt. Billie Jean tells him not worry about it, that they will get the scooter back.

That evening, in the trailer, their mother is half-scolding them for the bad situation while she gets ready for a date. In typical GenX fashion, she blames her son for the conflict and seems unwilling to intervene. She soon leaves for her date, and after being prompted with false hope by the horn of a passing golf cart, Binx runs off down the road to retrieve his scooter. This leads Billie Jean to have two friends, Ophelia and Putter, to drive her to the police station, where she wants to file a report. She explains that Binx bought it with insurance money that their dead father left them. Once again she is dismissed, as the detective she speaks to (Peter Coyote) says that Hubie is probably just trying to get her attention. Yet, when they arrive home, there is the scooter – all smashed and ripped up – and Binx is inside in the dark. Hubie has beaten him up badly.

In the light of day, Billie Jean and Binx have Ophelia to take them in the trailer park’s station wagon to the Pyatt’s seaside gift shop. Ophelia drives like a fool, and they’ve left the immature Putter at home. Binx is ordered to stay in the back seat, while Billie Jean goes inside. She finds Hubie working among the shelves and hands him a bill for $608 to fix the scooter. He scoffs at the bill, so she feigns a flirt with him and knees him in the balls. As Hubie is lying on the floor, Mr. Pyatt strolls in, calling for his son, then joins the dispute when Hubie shouts that Billie Jean is lying. She lives in the trailer park, Hubie remarks. What difference does that make, Billie Jean retorts. Mr. Pyatt appears to be more tactful than his son, but is also shadier. The elder man saunters around in bootcut jeans and untucked shirt with a bolo tie. He mumbles to Hubie to go outside, he’ll handle this himself. At first he appears to side with the pretty teenage girl, then says that he doesn’t keep large amounts of money in the register. She must come upstairs to the office to get it. A suggestion she at first resists, but he says, “You want the money, dontcha?”

Upstairs, Mr. Pyatt changes his mind about being so generous. He goes to a cash box and gets a tall stack of bills, but then refers first to her mother being pretty, then to the daughter being even prettier. His low voice and his insinuations tell us where the scene will go. He lays out five $10 bills and informs Billie Jean that she’ll get that much today and a little more every time she comes back, as he caresses her wrist then grips. She fights back, but the older larger man subdues her and utters the movie’s now famous lines: “You pay as you go, and earn as you learn.” As she is struggling against him, though, Binx and Ophelia come into the store. Binx doesn’t see his sister anywhere, so he goes to the cash register and pounds on the keys. The drawer opens, and there isn’t much money . . . but there is a .38 snub nose revolver. (Binx is so naive that he is looking at the gun and pointing the barrel right at his own face.) Meanwhile, Billie Jean knocks Mr. Pyatt off of her and descends the small spiral case to re-enter the store, where Binx has the gun. The boy thinks he’ll take control of the situation and points it at Pyatt, who tries to talk his way clear. Then Hubie returns, completely unaware of what he is walking into. The father tells his son to call the police, that Billie Jean has “suckered” him upstairs so Binx and Ophelia could rob the store. Binx tries to maintain control, refusing to let Hubie near the phone. As a last ditch effort, Pyatt throws Billie Jean aside and moves toward Binx, telling him the gun isn’t loaded. The boy is so inexperienced with a gun that he doesn’t even think to look in the chambers. Yet, as he examines the pistol, he pulls the trigger and shoots Mr. Pyatt in the chest. Ophelia screams, everybody runs, and Hubie grabs the telephone.

The next few minutes show scenes of panicked teenagers grabbing their things from the trailer to run away. Ophelia sits in the Breeze Haven Trailer Park station wagon alone while Billie Jean and Binx grab clothes and a little money. Putter, who is grounded from the night before, asks Billie Jean if she can some with them, gets told no, then lies to Ophelia saying she was told yes. Under cover of dark, their place of refuge is an abandoned mini-golf park. They try to get Putter to go back home with Ophelia but she’ll have none of it.

Back at the Pyatts’ store, the detective from the night before, Ringwald (Peter Coyote), arrives. He is shown school yearbook pictures of Binx and Billie Jeans, then mutters that he blew it. Seeing Hubie nearby, the detective goes over and makes nice before mentioning scooters to the usually feisty boy. We know that the Pyatts’ narrative is not going to hold up.

Over the next few scenes, we see the four teenagers driving around Corpus Christi and understanding what their predicament is. In a gas station, Billie Jean gets recognized by two teenagers, and they buy a newspaper, which tells them that Mr. Pyatt is not dead. Good news for them. But callers to the local radio station are against them, making Texas-style comments that justice must be done. Billie Jean calls home, where the police are waiting in anticipation of a call, and she speaks with Ringwald. They will turn themselves in, she says, but they want the $608 from Pyatt. He has to hand it to them, in person, in public. They will meet Pyatt and the cops at Ocean Park Mall near the fountain.

Across town, the Pyatts’ store is surrounded by curious onlookers, some of whom want to buy the homemade Wanted poster they have made with a picture of Billie Jean barely dressed and emerging from the swampy pond. Ringwald is there questioning Pyatt about whether he’ll accept the arrangement. He says hell no and also stands defiant when Ringwald comments on his willingness to sell Billie Jean’s image on a poster. (For a guy who got shot the day before and who proclaimed out loud that he lost two pints of blood, he looks pretty good, walking around with his arm in a sling but otherwise looking like nothing happened.)

At the mall, Billie Jean and her friends have a plan that is so GenX. After stealing their equipment – walkie talkies and such – from a mall toy store, Billie Jean gets ready to meet Mr. Pyatt while the other three wait in the parking deck. While Ringwald and Pyatt wait for Billie Jean, the two men converse and we find out that obstinate Pyatt is letting Ringwald put up his own money for the scooter repair. Then Billie Jean appears, looking very GenX in her baggy coveralls and man’s fedora, coming down the escalator. Ringwald caps off his conversation with an insinuation that he knows what Pyatt was doing with a pretty young girl up in his office. The unflappable Pyatt admits nothing and waits on his prey. Commenting to Billie Jean that she made a mistake, he drops the envelope of cash – that isn’t even his – and calls Hubie out of the potted plants. The incompetent boy chases Billie Jean but once again gets kneed in the crotch. His buddies emerge to help too, but they are equally incapable. Because these guys have messed everything up, the cops can’t catch her either. She runs through the mall with an overdub of Billie Idol’s “Rebel Yell.” The getaway car is all lined up, and Billie Jean escapes when Binx pushes a dumpster in front of the door she comes from. But the crafty Ringwald took another route and comes out a different door. Binx, who has clearly learned nothing, pulls a toy pistol and holds off the detective. To Binx, it’s all game. The battered old station wagon goes blasting through the barrier at the parking deck entrance, and they’re on the run again!

After seeing themselves on the news and having only seventy-eight cents for dinner, the foursome are realizing their predicament. They’re just kids. They don’t want to be committing crimes or running from the law. But they can’t go home. So they decide to find a big, fancy house to break into. After finding one that they believe is empty, they raid the kitchen and set up a smorgasbord in the dark dining room. Billie Jean goes to walk around the house and finds one of its occupants: a strange young guy who is wearing a halloween mask. His upstairs bedroom is something like a creepy media studio, but he isn’t threatening. When the others come upstairs and find him too, Binx wants to pull the outlaw act but the guy – Lloyd – just turns on the TV so they can see themselves on the news. There is Pyatt, excusing his behavior at the mall, while denigrating the younger generation, then the camera switches to a truck stop clerk who claims that the gang robbed him at gunpoint while doped up on drugs and alcohol. Disconsolate, they flip the channel from the absurdity and lies then land on the old black-and-white film that had Jean Seberg playing Joan of Arc. None of the trailer park kids know her story, so Lloyd gives them a quick lesson before jumping out his window into the swimming pool below. They all follow— except Billie Jean, who stays and finishes the movie.

After their swim, Billie comes running outside with an idea. Can Lloyd make video tapes? Sure. And copies? Sure. Billie Jean is going to send a taped message in response to all of the people being interviewed on the news. And there’s one more surprise. When she emerges from the bathroom, she has cut off all of her hair, like Joan of Arc. After they make the video tape and are about to leave, Lloyd offers himself as a “hostage” . . . willingly. They take him up on his offer, not knowing exactly what they’re saying yes to.

After their swim, Billie comes running outside with an idea. Can Lloyd make video tapes? Sure. And copies? Sure. Billie Jean is going to send a taped message in response to all of the people being interviewed on the news. And there’s one more surprise. When she emerges from the bathroom, she has cut off all of her hair, like Joan of Arc. After they make the video tape and are about to leave, Lloyd offers himself as a “hostage” . . . willingly. They take him up on his offer, not knowing exactly what they’re saying yes to.

Once the tape is broadcast, we see its contents. Billie Jean sends a message to the public that they aren’t liars or thieves, and that Mr. Pyatt must pay. “Fair is fair,” she declares. Back at the police station, where Ringwald and the others are watching, more info comes in: they have a hostage. Lloyd is the district attorney’s son. (We know that at this point, but Billie Jean and the others don’t.) As the DA and Ringwald talk at the DA’s house, they start to figure out that this is one part manhunt and one part search for a group of kids on a joyride.

Returning to the Pyatts’ store, they’re wrapped up with merchandising their newfound fame. They have t-shirts, posters, all the things. Even a large effigy of Billie Jean. Ringwald and the DA arrive to talk to Pyatt who is his same asshole self. Ringwald doesn’t think it’s a kidnapping, but the DA assumes that it could be. Pyatt just wants the “filth” cleaned up and shows the two law men letters of support that he has received from all over the country. It still looks like Mr. Pyatt is winning.

Across town, a few little kids identify the station wagon and approach, asking if she’s Billie Jean. The loudmouthed Putter confirms, and they say, “You gotta help Kenny, he’s in trouble.” Next we see, Ophelia, Binx, and Lloyd leave a clothing store – where they’re buying disguises – while Billie Jean is striding through a neighborhood with a small army of children. The first couple of kids have taken her to a house where a drunk and abusive dad has his son in a corner, frightened and alone. Billie Jean enters the house and tries to bring the boy out, but his father confronts her at first. Then he looks at the window, seeing all of the young people, and changes his tone. She walks the boy out and announces that he’ll be spending some time with his grandma, which raises cheers among the crowd. They stop then to sign autographs and have pictures taken. Billie Jean is clearly uneasy, though the others enjoy the attention. Binx tells a few lies when asked about incidents they’ve been accused of, and Billie Jean corrects him. Then, as a truck passes by, a woman recognizes them, and her redneck boyfriend decides to shoot at the car. He wants the reward money, but they speed away and escape again, but with a flat tire.

We’re at the one-hour point, in a ninety-minute movie. Our anti-heroes are exhausted and are running out of places to go. They’ve been on the news and are easily recognizable. Now we know about the fervent law-and-order sentiment against them. Earlier in the film, we heard people on the radio saying they had to be stopped, Mr. Pyatt has ratcheted up his rhetoric, and now a good ol’ boy in a monster truck is shooting at them in traffic in broad daylight. We’ve got a generational struggle going on: the young people love her, and while the adults want her stopped at all costs.

The gang of four stops by the waterside for a rest after their hair-raising experience with the rifle-toting good ol’ boy. They have to change the tire, and while they do, Billie Jean gives Putter an outdoor bath, since the young girl had her first period during the ordeal. As they hang around and figure out what to do, Lloyd and Billie Jean chat, and their romantic connection becomes clear. But Billie Jean is all business. She wants to get Ophelia and Putter out of the situation and plans to sneak away and alert the cops to where the car is.

Soon the cops, including Ringwald, arrive to find Ophelia and Putter asleep in the station wagon. Ringwald gives them the tough-cop treatment and tells them that Billie Jean has ratted them out. He wants to know where she is. Ophelia responds, Everywhere!

Debating on how to flee and where, Binx, Billie Jean, and Lloyd can’t agree on what to do or how. Lloyd offers to foot the bill for them to go to Vermont, but Billie Jean retorts that he’s just running away from home and is not in the predicament as her and her brother. While they fuss, Binx tries to steal a convertible Cadillac but nearly gets caught, which splits the three up. We follow Billie Jean for a while as a network of teenagers – many of them girls who have taken on her look – pass her from car to car, keeping her moving and undetectable. Cops search the streets as they do this, and we find out how popular the unwitting anti-hero has gotten.

After the montage, Billie Jean finds Binx and Lloyd at the abandoned mini-golf place. Billie Jean leaves Binx behind pretty quickly and snuggles up with Lloyd in one of the little shelters among the course. They have some quiet words under their sleeping bags and smooch a little bit. We are supposed to understand that they spend the night together, but we’re spared the visuals.

In the morning, Ringwald and the other cops are going through the station wagon andfind the colored golf balls from the mini-golf place where they’re hiding. He goes out there alone and talks into the empty space, believing them to be listening. He tells them that a scooter has been donated and that they can get what they want, if they’ll end this situation. They are, in fact, hearing what he says, and Billie Jean calls the police station later from a pay phone to dictate her terms.

This arrangement creates the final scenes in the movie, which occur on the beach. Loads of people are there, most of them young, and the police try to hold them back. The authority figures – Ringwald and the DA – half-bicker over how the thing should be handled. Ringwald has compassion for the kids, but the DA has to assume that his son is in danger. Soon, a team of snipers arrive, and Ringwald raises hell about that. But he doesn’t have time to get into it. Billie Jean and Lloyd come over the hill, with Lloyd’s hands on his head and his captor holding a pistol. Only it’s not really Billie Jean— it’s Binx in a dress. When we see the real Billie Jean, she’s in the crowd and is disguised in a wig, allowing her to uncover the scooter for Binx to see. Then that damn Hubie Pyatt, always the antagonist, bursts through the police line and runs out screaming, It’s not Billie Jean, it’s her brother! Frustrated by this unforeseen problem, Binx points the toy pistol at Hubie, and a sniper shoots him in the shoulder. Everyone goes nuts! Binx is taken away in an ambulance, which Billie Jean chases but doesn’t catch. Yet, it’s not over . . .

Now, she comes across Mr. Pyatt and his outdoor t-shirt stand full of posters that includes full-color images of her in a bikini and pictures of her face in a target. The final confrontation goes down, and she reveals his antics in the upstairs office to the watching crowd, which soon includes Ringwald, the DA, and Lloyd. Everyone stands stone-faced while she elaborates on the not-so-secrets they share, while Pyatt denies everything. Even Hubie is disgusted and sneaks away. Ultimately, Mr. Pyatt tries to give her a big ol’ wad of cash and says, “For your trouble.” But Billie Jean just gets more indignant, throws the money at the man, and knees him in the balls, too. He falls down in the process and knocks over one of his little torches on the scene. Soon, the whole place goes up, and the effigy of Billie Jean falls while she watches. We know as the flames destroy his merchandise that Mr. Pyatt will always be a lying, greedy asshole. Turning to run away, she runs into Ringwald, who just smirks and lets her go. The movie ends with the brother and sister in the cold snows of Vermont, where Binx is eyeing a snowmobile . . .

If you’ve read this far, consider showing some love.The Legend of Billie Jean wouldn’t be the same movie if it were set in another part of the country. We’ve got guns, we’ve got social class issues, and we’ve got law and order. The general plot and several of its main events involve guns, their use, and their misuse. If Binx had never grabbed the gun out of the cash register, the whole thing would not have happened. Several of the mishaps occur because Binx is a boy who knows nothing about guns but tries to play games like he does. Later, to emphasize the point, there’s the redneck in the monster truck who believes that he can pull out a deer rifle in broad daylight and shoot into a moving car full of teenagers. Why does he believe that’s OK? Because that’s what justice looks like to a lot of Southerners. It’s what justice looked to like to Binx in the Pyatts’ store, and it’s what it looked like to the monster truck dude.

The film also deals in a very Southern way with issues of social class, of who can be believed and who can’t. The Pyatts are business owners in the community, while Binx and Billie Jean are trailer-park kids living with a single mother. The only way that Binx got a scooter was through the death of his father, while Hubie and his friends are riding around in a convertible muscle car. In the store, when confronted about his own criminal behavior, including destruction of property and assault, his defense is to claim that the trailer-park girl is lying. We then see where Hubie gets it. His father takes the trailer-park girl upstairs with the intention of something between coerced prostitution and sexual assault. He assumes that she will concede to giving sex for money because of who she is and where she lives. After he refuses to pay for the scooter that his son damaged, his assumption throughout the film is that he will be believed while Billie Jean will not be.

Furthermore, understanding it in context of the zeitgeist in the 1980s, its story shows the younger generation railing against the older generation’s “law and order” mentality. This pervading idea in post-Civil Rights Southern culture said that the social-equality movements of the 1960s and ’70s had resulted in a chaotic, “all hell broke loose” environment where people of color were out of control, women were out of control, children were out of control . . . and white men had to get them back under control, in the name of “law and order.” The Legend of Billie Jean deals with the latter two of those three groups I just listed. We’ve got a single mom who can’t control her children, and a single father who can’t control his son— results of the breakdown of the traditional family, i.e. James Dobson. We’ve got a pretty girl who defies an older man’s advances – women are supposed to yield to men, in this way of thinking – and she goes on the run, cuts off all of her hair to look like a boy, and ultimately burns down his business. During this whole thing, Mr. Pyatt is saying to anyone who’ll listen that no concessions should be made, the kids need to be subdued, and his word should be believed over theirs. The truth is that he is an abuser, a liar, and a profiteer who has no shame, but that has no bearing in his sense of who should be regarded more highly. (Thankfully, the police – all men – see through him, even though they still have to do their jobs.)

While the movie is politically progressive in terms of gender and age, it is virtually mute, even sanitized, in its handling of race. Almost everyone we see in the film is white, even though Corpus Christi has a significant Hispanic/Latino population. We do see a few black people, here and there, but they are extras in crowd scenes. This is a very white movie, even though its locale is less so. Certainly, the story and the medium wouldn’t lend itself to taking on racial issues as well, but it can’t be ignored that this one is whitewashed. The closest we get to a racial aspect in the film is Mr. Pyatt’s sense of white male privilege, which is seen but never discussed.

One other “character error” in the movie, pointed out in IMDb’s “Goofs” section, reads, “The majority of characters are depicted to have heavy southern accents. However, in the South Texas region where Corpus Christi is located, not many residents have an accent.” The blog Film School Rejects also comments on the perhaps-too-heavy Southern accents, as does the website Vanity Fear. That seems generally agreed-upon. My assumption would be that the heavy Southern accent added to Billie Jean’s lower-classness.

Although it is a little cheesy in hindsight, The Legend of Billie Jean is a classic for the sentiments it conveys. The title song “Invincible” by Pat Benatar centers on the sentiment that young people are in a perpetually bad position with adversity on all sides, and thus fighting back is the only answer. Hopefully, viewers get the idea that this is supposed to be a modern Joan of Arc story, though Billie Jean Davy fares better than the woman whose haircut she adopts. The similarities, beyond that haircut, are only vaguely present. Joan of Arc heard the voice of God and led an army into battle before suffering betrayal and death; Billie Jean Davy refused to be sexually assaulted, protected her brother from criminal charges, and unwittingly led a populist youth revolt. Not exactly the same thing.

November 14, 2024

Dirty Boots: 1994

I’ve been thinking lately about how 1994 was thirty years ago. It doesn’t really matter that it was thirty years ago – as opposed to, say, seventeen or forty-three – but it’s the fact of saying “thirty years ago” that makes it troubling, I think. 1994 constituted the latter half of my sophomore year of college and the first half of my junior year. I turned 20 that summer, had a job at veterinary clinic, and still lived at home with my divorced mom. The internet wasn’t a thing yet. Beepers were common, but cell phones were not. We still had malls with food courts and record stores, as well as a handful of independent bookstores around town. My social life consisted of playing acoustic guitars with a few friends in the outdoor amphitheater of the local museum, eating a lot of cheap food at Waffle House, and sometimes playing pool at the bowling alley. There aren’t many pictures of us from back then, because film cost money.

I’ve been thinking lately about how 1994 was thirty years ago. It doesn’t really matter that it was thirty years ago – as opposed to, say, seventeen or forty-three – but it’s the fact of saying “thirty years ago” that makes it troubling, I think. 1994 constituted the latter half of my sophomore year of college and the first half of my junior year. I turned 20 that summer, had a job at veterinary clinic, and still lived at home with my divorced mom. The internet wasn’t a thing yet. Beepers were common, but cell phones were not. We still had malls with food courts and record stores, as well as a handful of independent bookstores around town. My social life consisted of playing acoustic guitars with a few friends in the outdoor amphitheater of the local museum, eating a lot of cheap food at Waffle House, and sometimes playing pool at the bowling alley. There aren’t many pictures of us from back then, because film cost money.

Being in college at the time, I can say that 1994 was a good year for the wildly varied non-genre of “college rock,” and the music coming out of the South contributed to that variety. That summer, Hootie & the Blowfish from South Carolina released their instant-classic Cracked Rearview, and a couple of similarly styled albums followed on its heels: Sister Hazel’s self-titled debut and Edwin McCain’s Honor Among Thieves. Indigo Girls were a known commodity by then, and their Swamp Ophelia came out that year. After a few years of dissonant angst from the grunge bands, having some singalong tunes was a nice change of pace. Yet, the alternative scene was going strong in North Carolina: The Connells and Superchunk put out New Boy and Foolish, respectively. On the rockier side, there were Amorica by The Black Crowes and Hints, Allegations, and Things Left Unsaid by Collective Soul. Both of those bands were from the Atlanta area. And jam band folks got one of the all-time greats, Widespread Panic‘s Ain’t Life Grand.

Thirty years ago this month, Florida native Tom Petty’s Wildflowers album was also released, as was the film adaptation of Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire, which was set in New Orleans. Wildflowers was one of Petty’s best albums and marked a departure from his ’80s sound in songs like “You Got Lucky.” As for the film, a lot of people I knew had been reading the Lestat books and were excited about the film. Living only a few hours away, most of us had been to New Orleans at least once by then and had a feel for the city and its creepy vibes.

1994 was also the year of a racial controversy in Wedowee, in eastern Alabama, that made national news. The 1980s and ’90s were an awkward time for racial issues in Southern schools, since many of the required integration plans had had real effects by then. We were truly all in it together at that point. I can remember our local public junior high and high schools having separate homecoming and prom courts, white and black, because whichever group constituted a school’s numerical minority didn’t stand a chance of placing one of their own in the court. Though it probably seems like another form of segregation today, it was seen back then as a progressive move toward achieving equality. Up in Wedowee in 1994, the high school’s leader declared that there should be no interracial couples attending the dance, which received a “What about me?” from one biracial student. His response was to say that he was trying to prevent a “mistake” like her from happening. The situation was picked up by national media, and for a while, those involved became household names.

Despite that ugly situation, I think back fondly on the mid-1990s. Not just because those were my college years, but because I remember it as a time of hope, generally, since some factors pointed to a good future. Thinking about the Wedowee situation, it sucked that that was happening, but our generation recognized that it was shameful and wrong. Further out, we liked the guys in the White House: Bill Clinton, a Southerner, and Al Gore, another Southerner. New inventions, like mobile phones and computers, were making life easier but hadn’t taken over our lives. People weren’t drowning in social media and walking into phone poles yet. Culturally, the Old South was almost gone, the Sunbelt South had peaked, and the South of the twenty-first century hadn’t emerged. In Alabama, a period of bipartisan government, party switching, and economic development had marked the 1970s, ’80s, and 90s, then we elected our last Democratic governor in 1999. The controversial Bush-Gore election was still a ways off, the hyper-partisan 2000s weren’t on our radar, and the Red Wave of 2010 was unimaginable. For a moment, in the mid-1990s, it seemed to a bunch of GenXers just entering our 20s that the old problems might get resolved and that they wouldn’t be replaced by new (sometimes worse) ones . . . Boy, were we mistaken.

November 7, 2024

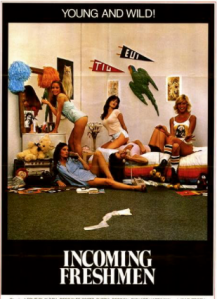

Southern Movie 72: “Incoming Freshmen” (1979)

The Southern goofball sex comedy Incoming Freshmen from 1979 indulges in the wild college campus motif. Its tagline reads, “An innocent girl from a small town arrives at a modern institution of education to complete her studies. Once there she starts various relationships with different boys.” The story lies somewhere among 1978’s Animal House, 1981’s Porky’s, and 1983’s Meatballs, but this one is of much lower quality. Written and directed by Eric Lewald, who hailed from Georgia and Tennessee, Incoming Freshmen is a lighthearted spoof of the college experience in the South in the late 1970s.

Incoming Freshmen opens with scenes of move-in day and registration at a college. All of the students and employees are white. While our main character signs in and looks for her room, we see a couple making out and slowly undressing. Eventually the young woman, who has been our focus for most of the time the credits are rolling, walks in on the half naked couple. She looks shocked and runs away. Her roommate jumps up and calls after her, but the interloper is long gone. While she gets dressed, the young man there basically ignores her while she explains the tribulations of living with a prude. Out on the sidewalk, the sexy co-ed assures her fleeing roommate that everything is OK, and the two return to their room arm in arm.

The next scene brings us to a classroom for a freshman orientation lecture. Students, male and female, pile in. A stern looking woman in a military or police uniform enters first, and she is followed by a very fat male professor. For some reason, a bell rings to start class, as though it’s high school. While the rotund professor says a word of welcome, he undresses one student with his eyes, then yields the floor to the uniformed woman, who is from the ROTC. As she speaks, he imagines her undressed as well. Once the ROTC talk is done, he invites the female students to leave, then admonishes the male students to stop the tradition of hanging a condom on his office door. For an old perv, he certainly is prudish, too.

Moving on from his antics, we meet a small group of young men – most white, one black – and they’re talking about meeting girls. Meanwhile, back in the dorm room, the free-spirited roommate Viv is explaining to the prudish roommate Jane about swimming in the “veritable ocean of masculinity” on campus. Viv says that a girl has to just keep trying them out until she finds the one that’s right for her. Wouldn’t that mean that everyone was dating everyone else, the prude asks. Well, yes. And we have our film’s premise. While one roommate explains that college is for trying new things, the other says that she wants mostly female friends, possibly a few boys too but only as friends. She has a boyfriend back in Sweetbriar – presumably the small town she’s from – so there won’t be much dating. Just then two other girls pop in, chattering and smiling. They are wearing sweatshirts for their sorority, Delta Pi, and certainly we get the sexual innuendo of the name. The main benefit of their sorority getting lots of dates.

Across campus, the dean runs into Dr Bilpo, the portly professor from the orientation lecture. After the two men ogle a co-ed who passes by, the dean asks Bilpo to check out a situation that has come up. Apparently, some male students have managed to make a peep hole to see into the girls’ locker room. “I’ll look into it,” says Bilpo. He knocks on the door and calls inside, but no one answers. Of course, he goes in, and while he’s there, a black janitor arrives to clean up. The janitor is muttering to himself about he hates his work. Bilpo tries to hide in the showers to avoid being found, but the janitor turns on the waters and drenches the big man. He comes out fussing, and the janitor responds with equal venom. But the stage is set for the salacious academic to go back later for another look.